#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜망할음악нотыnoten

Text

The Blue Side of Jazz - Joe Pass (2006)

Joe Pass - The Blue Side of Jazz (2006 documentary)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5wOdikpRu8

Jazz sheet music download.

00:00 blues 01:18 "hello fellow guitarists" 03:12 ending a tune 05:38 12 bar blues 06:18 V ↔ I 06:53 half step above I (♯I ~ V) 07:58 half step above IV (♯IV ~ I) 08:42 half step below I (bI7 → I) more specifically (bI13b9 → I) 10:00 “On the guitar, a lot of playing is with forms and continuity” 10:37 half step above IV (♯IV → IV), here using ♯IV13 11:19 half step above IV (♯IV → IV), but changing the root to the b5 (which is the I) 11:56 IV → IV♯dim (IV♯dim ~ (bI13b9)

13:22 turnaround: C9 B7 E7 Am11 D7 G7 (keeping a common tone—the note D) 14:28 12 bar blues (basic) 15:02 12 bar blues (with more subs) 15:58 12 bar blues (with other voicings) — many good voicings 17:32 turnaround 18:06 the importance of continuity in chordal improvisation 21:20 12 bar blues (with voice leading and pedal tones) 22:52 “I'm using a lot of the same grips, they're bar forms. They're chords that all guitar players learn and know” 23:53 12 bar blues

24:20 dom7 ↔ m7 25:10 +examples 25:33 the importance of common tones (in changes) 26:47 “Always count 1, 2, 3, 4. I don't know why” 😂 26:53 12 bar blues 27:07 moving chords down chromatically (C13 B13 Bb13/E A13) 27:46 “you can always move chords either chromatically or through a cycle” 28:35 variation (moving down chromatically) 29:30 12 bar blues (with many 251s), 50s/60s style 30:27 same above

30:57 blues 50s style 31:55 alternative version 33:14 again 33:52 pinky chordal movement (I IV V anchored in I) 34:12 don't do things that break the flow of music 34:47 most guitar greats use mainly simple barred forms 36:09 lines that come from simple forms 37:06 “don't play any chords with four fingers that you can play with two or one” 41:52 another blues variation 42:27 using diminished chords as dom7 chords 43:01 another blues 45:50 Joe checking why his lick wasn't working 49:59 another blues

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Oscar Peterson LIVE In '63, '64, '65 (Jazz Icons)

Oscar Peterson LIVE In '63, '64, '65 (Jazz Icons)

Personnel:

Tracklisting: Sweden (1963)

Denmark (1964)

Finland (1965)

Jazz sheet music download.

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

Oscar Peterson LIVE In '63, '64, '65 (Jazz Icons)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_JrIcoFcnjE

Personnel:

Oscar Peterson: piano Ray Brown: bass Ed Thigpen: drums Roy Eldridge: trumpet (Sweden) Clark Terry: trumpet, flugelhorn, vocals (Finland).

Tracklisting:

(please, note some small parts have been deleted to avoid copyright issues with YouTube)

Sweden (1963)

01. Reunion Blues 02. Satin Doll (partially deleted) 03. But Not For Me 04. It Ain't Necessarily So 05. Chicago (That Toddling Town)

Denmark (1964)

06. Soon 07. On Green Dolphin Street (partially deleted) 08. Bags' Groove 09. Tonight 10. C-Jam Blues 11. Hymn To Freedom (partially deleted)

Finland (1965)

12. Yours Is My Heart Alone 13. Mack The Knife 14. Blues For Smedley 15. Misty 16. Mumbles

Jazz sheet music download.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

"Desafinado" by Antonio Carlos Jobim, Newton Mendonça and Jon Hendricks

Desafinado - Antonio Carlos Jobim & Joe Henderson (HQ)

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.Form and Melody

Text Setting

Harmony

Conclusions

Source

Jobim's Sheet Music download.

Desafinado - Antonio Carlos Jobim & Joe Henderson (HQ)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMLo05EGuBw

There has been a healthy dose of Latin songs that have made their way into the Great American Songbook—after all—Central America and South America are every bit as "American" as the United States. Among the composers of Latin jazz standards, the inimitable guitarist/composer, Antonio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994), stands tall. Jobim composed a great many enduring songs that jazz musicians have latched onto as essential Great American Songbook gems.

Newton Mendonça wrote the original Portuguese lyrics, after which the vocalese master, Jon Hendricks (b. 1921), created an English version. The resulting work is an interesting study in both lyrics and music. The Portuguese word "desafinado" essentially means "out of tune," which justifies Jobim's pointed use of dissonant intervals and non-diatonic melody notes. The pathway followed by the song explores various tonal centers in search of consonance, and the lyricists beautifully captured this essence.

Form and Melody

The form of this song departs from the common AABA and ABAB, thirty-two bar forms. The eight-bar A theme (measures 1-8) is comprised of two four-bar phrases, each mostly stepwise (walking up a perfect fourth) and shaped like a double arc, ending on the flat 5 of the V/V chord in m. 3 and on the flat 5 of the iii7(b5) chord in m. 7).

A is followed by an eight-bar B theme (mm. 9-16). B can also be divided into two phrases, and begins with a quick interval of an ascending seventh starting on an offbeat, which leads directly into a descending line, first stepwise, then involving leaps that highlight dissonances.

The A theme reappears in the next eight bars (mm. 17-24) before a C theme (reminiscent of B for only the first bar) serves as a transition into a new key a major third higher than tonic (mm. 25-32). A new section begins (D at mm. 33-40) and is melodically characterized by a major second stepping back and forth between scale degrees 5 and 6 in the new key, after which a transposition of the new melody motif (the E theme, up a minor third from the D theme) carries the song to the original dominant (V) to bring the listener back to the A theme in the tonic key.

This A statement ends a bit differently, creating an arc of energy at the apex of the second phrase, so it is called A' (A-prime).

This modification of A is often a very useful songwriting strategy, as it creates interest and variation, bringing the song around to a fresh ending having a touch of new material. This new material begins with a four-bar phrase of descending stepwise melodic sequences ("We're bound to get in tune again before too long,") which connect to another eight-bar melodic group characterized by tonal repetition of the tonic pitch.

Jobim utilized a type of cadential extension here, creating a twelve-bar final theme instead of the expected eight. This final twelve bar segment resembles a coda or "tail" built right into the piece (F theme). When one steps back, one can see that Jobim utilized a loose sonata form here—ABAC represents the Exposition, D and E are the Development (a transitional section), A' clearly represents the Recapitulation (return of A) and the F theme functions as an obvious coda.

Jobim's use of motives plays a strong role in this melody's originality, as does his playing with dissonant tones outside the diatonic scale. Predominant motives include the opening four steps up the diatonic major scale in the very first bar. This melodic and rhythmic motive appears in both forward and retrograde varieties (retrograde in m. 9, with variation at m. 13, then retrograde in sequence with a downward step progression at mm. 57-58). A second motive Jobim employs is the rocking whole step, first cleverly introduced at m. 29 ("like the bossa nova, love should swing.").

He features this motive in the last four bars of the first major section of the piece, anticipating and announcing the next large section's primary motive. At mm. 33-48 (the D theme), Jobim combines both motives in an alternating, smoothly flowing pattern, showing his mastery of creating motivic and melodic unity. Hendricks mirrors the more consonant music in this section by using text reminiscent of bygone happy times ("We used to harmonize two souls in perfect time...").

The motive in the final twelve bars, a repeated tonic pitch, successfully makes the composer's point of finally attaining concordance (there is nothing more concordant than a unison pitch) following a melody peppered with dissonant leaps and unexpected tonal shifts. Hendricks' response here reinforces the music with an idealized text depicting two hearts and souls at last abiding in perfect harmony.

Text Setting

As acknowledged above, the lyrics for "Desafinado" were originally in Portuguese, and these are still performed today. Whenever a writer is faced with the challenge of re-setting a text from another language to existing music, there are several important considerations.

First, one must comprehend the difference between a translation and a transliteration. A translation represents the precise meaning of a text in another language. A transliteration merely fits the music into a new language's pattern of declamation—it may have little or nothing to do with the original text's meaning.

A competent lyricist will have a full understanding of the original text's translation before attempting a new transliteration into another language. Some transliterations respect the original text as well as convey the general meaning and theme of the composer's and lyricist's intent. Other transliterations seem to start with a clean slate and find alternate ways to convey a composer's intent (that seems to be the case here with Hendricks' lyrics).

Either way, tastefully setting the text in a manner that suits the singer and preserves the integrity of both music and lyrics becomes the goal. When studying a word-by-word translation of this original text, one quickly discovers that the Portuguese song's theme is about a singer feeling hurt by her lover's disapproval of her out-of-tune singing. She chastises him for not remembering that even those who sing out of tune have fragile hearts.

By contrast, Hendricks' lyric approach changes the focus of the song to describe two people whose dissonant hearts must be made consonant for love to thrive. Regardless of the version preferred, a comparison of these two very different perspectives lends itself to a deeper understanding of the music and how it can be interpreted. Two lyricists may set the same piece of music using completely different paradigms. In this case, Mendonça spoke from a literal point of view regarding the dissonance expressed in the song title, while Hendricks spoke from a figurative, metaphorical standpoint.

Harmony

Jobim's initial harmonic move (between the first and second chords of the piece) immediately sets the tone for a theme of dissonance throughout the song. He moves from a casual I chord to a V7(b5)/V—in no way providing smooth harmony or easy voice leading. He then mollifies the harshness by turning that chord into a minor chord over the same root and moves through a ii7-V7 progression which leads to a surprising vi7(b5), reflecting the previous b5 chord. The melody notes here are those dissonant b5s and b9s.

His B theme starts with ii7 and proceeds through a circle of dominant chords, but does not find its way back to the V of tonic before he interjects a dissonant major 7th built on the b9 immediately preceding a turnback progression (V7-I) to return to A. Jobim's unexpected harmonic shifts effectively create the dissonant tension illuminated in the text. The C theme combines the two motives previously described and shifts the harmony from I to III. Not coincidentally, Hendricks' lyrics beautifully reflect the harmony at this juncture: "Seems to me you've changed the tune we used to sing..."

At the D theme, Jobim utilizes a chromatically ascending bass from I-dim7/ii-ii-V7 followed by a typical I-vi-ii-V7 before modulating up a third and repeating the chromatic ascent (in the new key). He then transforms the V7 chord of that new key into a minor ii of the original tonic, moves to a non-diatonic, flat vii chord (Hendricks again catches this, and writes "slightly out of tune" in the measure containing this "wrong" chord) before landing on a V7/V-V7-I progression that returns to the A theme. Harmonically the song assumes a ii-V7-iii(b5)-VI7-ii shape at the point where A digresses to become A' (m. 55, "sing a song of loving").

In the four-bar transition (mm. 57-60) that opens the F theme, the harmony passes through an unusual juxtaposition of ii-iv6-I ("we're bound to get in tune again before too long...") before extending a cadence via a roundabout V7/V-bVII7-V7/V which finally makes its way to ii-V7-I in the tonic key.

Conclusions

"Desafinado" takes the idea of wordpainting (reflecting textual meanings in music) to a new level in so many ways, and yet, one could argue the reverse if the music were composed first (that the lyricists served as obsequious handmaidens of the music). Either way, both Jobim and Hendricks showed their cleverness by creating a piece of music in which the wedding of music and text are readily apparent in the way the text parallels non-diatonic, melodic pitch choices, dissonant harmonic tension, and the third-related, leaping tonics that wander throughout the A-B-A-C-D-E-A'-F (sonata) form this unusual piece exhibits.

The enduring renown of this piece is remarkable, given its fascinating complexity, and yet, Jobim was careful to balance complexity whenever it occurred with something relatively simple, thereby maintaining the song's accessibility and relevance for generations of listeners. For example, when the melody was challenging and non-diatonic, he tended toward complementing it with more traditional, gentle-on-the-ear harmonies, never seeking to completely confound those performing or listening to the song.

Similarly, when the harmony explored new territory, the melody tended to be motivic and, therefore, familiar. Such exquisite balance between complexity and simplicity, light and dark, dynamic and static, and dissonance and consonance, appears to be ever present in so many wonderful works that make up the Great American Songbook.

Source

Jobim's Sheet Music download.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Mozart Grieg: Piano Sonata no 16, K. 545 arr. for 2 pianos (sheet music, Noten)

Mozart Grieg Piano Sonata no 16, K. 545 arrangement for two pianos with sheet music, Noten

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7IfHeQ66GkE

On 27 May 1877 Edvard Grieg wrote to his publisher: "During the winter I have been engaged on a task that I found particularly interesting - adding a free, second piano to several of Mozart's sonatas.

The work was intended in the first instance for teaching purposes, but by chance found its way into the concert hall, where the whole thing sounded surprisingly good." Grieg himself went some way towards preempting potential protests by insisting that his arrangements were intended for teaching.

Such a line of argument obliges to examine the customs of the time - an age in which the gramophone was barely a glint in its investor's eye and there was no opportunity to hear and follow interpretations at second hand.

As a result, it was common practice around 1880 for piano teachers to accompany their pupils on a second piano, either to ensure the correct tempo or, perhaps, to make the soloist's solitary existence somewhat less intolerable...

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Oblivion, by Astor Piazzolla for Cello and piano arr. (partitura, sheet music)

Oblivion (Astor Piazzolla) for Cello and piano arr. (partitura, sheet music)

https://vimeo.com/504110828

Sheet Music download here.

sheet music score download partitura partition spartiti 楽譜 망할 음악 ноты

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

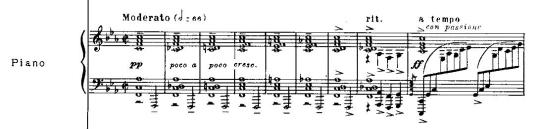

Rachmaninow D minor Sonata Op 28 II Lento Zoltán Kocsis (Noten)

Rachmaninow D minor Sonata Op 28 II Lento Zoltán Kocsis, Noten, with sheet music

Bester Notendownload aus unserer Bibliothek.

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!Background

Composition

Reception

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.

Rachmaninow D minor Sonata Op 28 II Lento Zoltán Kocsis, Noten, with sheet music

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4YtSGrxwrM

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28, is a piano sonata by Sergei Rachmaninow, completed in 1908. It is the first of three "Dresden pieces", along with Symphony No. 2 and part of an opera, which were composed in the quiet city of Dresden, Germany.

It was originally inspired by Goethe's tragic play Faust; although Rachmaninow abandoned the idea soon after beginning composition, traces of this influence can still be found. After numerous revisions and substantial cuts made at the advice of his colleagues, he completed it on April 11, 1908. Konstantin Igumnov gave the premiere in Moscow on October 17, 1908. It received a lukewarm response there, and remains one of the least performed of Rachmaninow's works.

It has three movements, and takes about 35 minutes to perform. The sonata is structured like a typical Classical sonata, with fast movements surrounding a slower, more tender second movement. The movements feature sprawling themes and ambitious climaxes within their own structure, all the while building towards a prodigious culmination. Although this first sonata is a substantial and comprehensive work, its successor, Piano Sonata No. 2 (Op. 36), written five years later, became the better regarded of the two. Nonetheless, it, too, was given serious cuts and opinions are mixed about those.

Background

In November 1906, Rachmaninow, with his wife and daughter, moved to Dresden primarily to compose a second symphony to diffuse the critical failure of his first symphony, but also to escape the distractions of Moscow. There they lived a quiet life, as he wrote in a letter, "We live here like hermits: we see nobody, we know nobody, and we go nowhere. I work a great deal," but even without distraction he had considerable difficulty in composing his first piano sonata, especially concerning its form.

The original idea for it was to be a program sonata based on the main characters of the tragic play Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles, and indeed it nearly parallels Franz Liszt's own Faust Symphony which is made of three movements which reflect those characters. However, the idea was abandoned shortly after composition began, although the theme is still clear in the final version.

Rachmaninow enlisted the help of Nikita Morozov, one of his classmates from Anton Arensky's class back in the Moscow Conservatory, to discuss how the sonata rondo form applied to his sprawling work. At this time he was invited, along with Alexander Glazunov, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Scriabin, and Feodor Chaliapin, to a concert in Paris the following spring held by Sergei Diaghilev to soothe France–Russia relations, although Diaghilev hated his music. Begrudgingly, Rachmaninow decided to attend only for the money, since he would have preferred to spend time on this and his Symphony No. 2 (his opera project, Monna Vanna, had been dropped). Writing to Morozov before he left in May 1907, he expressed his doubt in the musicality of the sonata and deprecated its length, even though at this time he had completed only the second movement.

On returning to his Ivanovka estate from the Paris concert, he stopped in Moscow to perform an early version of the sonata to contemporaries Nikolai Medtner, Georgy Catoire, Konstantin Igumnov, and Lev Conus. With their input, he shortened the original 45-minute-long piece to around 35 minutes. He completed the work on April 11, 1908. Igumnov gave the premiere of the sonata on October 17, 1908, in Moscow, and he gave the first performance of the work in Berlin and Leipzig as well, although Rachmaninow missed all three of these performances.

Composition

Movement 1.

The piece is structured as a typical sonata in the Classical period: the first movement is a long Allegro moderato (moderately quick), the second a Lento (very slow), and the third an Allegro molto (very fast).

- Allegro moderato (in D minor, ends in D major) The substantial first movement Allegro moderato presents most of the thematic material and motifs revisited in the later movements. Juxtaposed in the intro is a motif revisited throughout the movement: a quiet, questioning fifth answered by a defiant authentic cadence, followed by a solemn chord progression. This densely thematic expression is taken to represent the turmoil of Faust's mind. The movement closes quietly in D major.

- Lento (in F major) In key, the movement pretends to start in D major before settling in the home key of F major. Although the shortest in length and performance time, the second movement Lento provides technical difficulty in following long melodic lines, navigating multiple overlapping voices, and coherently performing the detailed climax, which includes a small cadenza.

- Allegro molto (in D minor) Ending the sonata is the furious third movement Allegro molto. Lacking significant thematic content, the movement serves rather to exploit the piano's character, not without expense of sonority. The very first measures of the first movement are revisited, and then dissolves into the enormous climax, a tour de force replete with full-bodied chords typical of Rachmaninow, which decisively ends the piece in D minor.

Reception

Rachmaninow played early versions of the piece to Oskar von Riesemann (who later became his biographer), who did not like it. Konstantin Igumnov expressed interest upon first hearing it in Moscow, and following his suggestion Rachmaninow cut about 110 bars.

The sonata had a mediocre evaluation after Igumnov's premiere in Moscow. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov had died several months previously, and the burden of heading Russian classical music had fallen on this all-Rachmaninow programme of October 17, 1908. Although the concert, which also included Rachmaninow's Variations on a Theme of Chopin (Op. 22, 1903), was "filled to overflowing", one critic called the sonata dry and repetitive, however redeeming the interesting details and innovative structures were.

Lee-Ann Nelson, via her 2006 dissertation, noted that Rachmaninow's revisions are always cuts, with the material simply excised and discarded. The hypothesis is that the frequency of negative responses to many of his pieces, not just the response to the first symphony, led to a deep insecurity, particularly with regard to length. The musicologists Efstratiou and Martyn argued against, for instance, the cuts made to the second sonata on a formal basis. Unlike other pieces, such as the second piano sonata and the fourth piano concerto, no uncut version of this piece is currently known to be extant.

Today, the sonata remains less well-known than Rachmaninow's second sonata, and is not as frequently performed or recorded. Champions of the work tend to be pianists renowned for their large repertoire. It has been recorded by Eteri Andjaparidze, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Boris Berezovsky, Idil Biret, Sergio Fiorentino, Leslie Howard, Ruth Laredo, Valentina Lisitsa, Nikolai Lugansky, Olli Mustonen, John Ogdon, Michael Ponti, Santiago Rodriguez, Alexander Romanovsky, Howard Shelley, Daniil Trifonov, Xiayin Wang, and Alexis Weissenberg. Lugansky performs the piece regularly.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Relax and Reflect - A Fading Summer's Eve - FINAL FANTASY XV (sheet music, 楽譜)

Relax and Reflect - A Fading Summer's Eve - FINAL FANTASY XV with sheet music, 楽譜

https://vimeo.com/491973640

Final Fantasy XV music

Final Fantasy XV: Original Soundtrack is mainly composed by Yoko Shimomura, who is known for her involvement with the Kingdom Hearts series. Shimomura was responsible for at least 80% of the soundtrack; the rest of the pieces are variations of her compositions that were handled by other people.

Yoshitaka Suzuki worked as composer/arranger, and Shota Nakama worked as composer/arranger/orchestrator. Shota runs a group called Video Game Orchestra (VGO) that does rock symphonic concerts and operates in the recording industry. VGO was contracted to work for Final Fantasy XV, and Shota conducted all recording sessions and contracted the orchestras and the choirs.

Every line ensemble was through VGO, and Shota's team mixed it as well. This is the first time a Final Fantasy game uses a North American orchestra. Suzuki worked on the game for one year, on and off, and did have a crunch time. In total, he did around twenty-five pieces. At the same time, he was also composing for the movie, Kingsglaive: Final Fantasy XV. Nakama started working on the game in 2014, and worked on the trailers.

Some themes featured on Final Fantasy XV: Original Soundtrack aim to encompass "friendship" and "filial bonds." Shimomura tried many different methods, discussed with directors to share the world view, looked at images for inspiration, and read and took in the story to be inspired.

The way Suzuki composed for the game was to get many gameplay videos. He imported them to his software, and then composed to the video as if he was in the game as a player. The sadness for the compositions thus came intuitively. Visually, he realized what was happening in the game, seeing it from two different points of view—composer and player—and tried to incorporate whatever emotion he was experiencing into it.

Suzuki has cited his experience with composing for the Metal Gear series as an advantage when he composed music for the base infiltration scenes in Final Fantasy XV. Final Fantasy has such a long legacy, and the composers valued its spirit, and thus would throw in the "Prelude" (such as in "Hellfire"), and put in little fragments of the previous melodies and motifs.

Yoko Shimomura was working on Final Fantasy XV: Original Soundtrack even when Final Fantasy XV was still known as Final Fantasy Versus XIII. Since the game was not originally part of the main Final Fantasy series, Shimomura felt she did not need to worry about following in other Final Fantasy composers' footsteps. By the time Final Fantasy XV was announced, Shimomura had already developed a clear concept of how she could continue on her initial path. The rebranding of Final Fantasy Versus XIII necessitated new music.

Sho Iwamoto, audio programmer at Square Enix, talked at Game Developers' Conference 2017 how music is incorporated into Final Fantasy XV. He designed and implemented an interactive music system, as there was a worry making the music interactive would distort the music or not make it memorable. According to Iwamoto, Final Fantasy music is known for being epic, memorable, to have a strong melody line, and to be one of the selling points of the series. The aim was to have seamless transitions while not losing "epicness". The goal was not to avoid repeating the same music, but to enhance the player's emotional experience by playing applicable music that would suit the situation.

For example, when riding a chocobo, the music picks up pace when the bird trots. The music also changes when the chance to summon appears and when the player summons, and during set piece boss battles, to reflect what is happening, such as the music fading into a dramatic finish just as the boss dies. In outposts like Hammerhead and at Galdin Quay, the background music seamlessly changes when the player steps into the restaurant. The transition time for the chocobo music is set longer so that the music would not change every time the player must slow down to avoid a tree or to turn.

Release

The album was released on December 21, 2016. The basic soundtrack was released on 4 standard CDs and on Blu-ray, which includes the music, movie data, and active internet support.

A limited edition version was also released. It contained the Blu-ray soundtrack with two bonus videos, a CD with select song arrangements, and a "Special Music Collection" Blu-ray with select tracks from all numbered Final Fantasy titles, Dissidia and Dissidia 012, Type-0, Justice Monsters Five, and Kingsglaive.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Galuppi Baldassare Piano Sonata Nr 5, C Major with sheet music

Galuppi Baldassare Sonata Nr. 5, C Major with sheet music

https://vimeo.com/478236673

Galuppi Baldassare biography

Baldassare Galuppi, a key figure in the history of Italian comic opera, was for some time known only through his mention in Robert Browning's poem "A Toccata of Galuppi's." Galuppi's father was a barber and violinist who gave his son elementary music lessons. By the age of 16 he had composed an opera, La fede nell'incostanza ossia Gli amici rivali. It was a spectacular failure; the curtain had to be brought down before the audience rioted.

The puzzled young man went to the composer Benedetto Marcello to try to find out why. The mentor took him to task for daring to write an opera before he was ready, and made him promise not to compose anything for three years, but to undertake study with Antonio Lotti, who called Galuppi his best pupil.

Galuppi went to Florence to work as a harpsichord player in the orchestra of Teatro della Pergola in 1726. He returned to Venice and formed a partnership with a writer friend of his from school, G.B. Peschetti. His second attempt at opera, Dorinda (1729), was a major success. For the rest of his life he averaged about two operas per year, and they were played of Italy's major theaters.

In 1740, the Ospedale dei Mendicanti (which included a conservatory) hired him as music director; he established a superb orchestra and church music for the institution. Meanwhile, Galuppi accepted an offer in 1741 from the Earl of Middlesex to write opera seria for his theater in the Haymarket, London. His first effort was moderately well received, and each successive opera was more popular than the last.

On returning to Italy in 1743 he took note of the cutting-edge Neapolitan innovation, opera buffa, and tried his hand at it. After some initial failures these comic operas, too, started to catch on. In 1748 he was appointed maestro of the cappella ducale at St. Mark's cathedral (and in 1762 was promoted to the head position, maestro di cappella, considered the top musical job in Venice).

In 1751 the pressure of these positions led him to give up the position at the Mendicanti. His first comic success was L'Arcadia in Brenta, to a libretto by Carlo Goldoni, with whom Galuppi forged a partnership. Galuppi's best operas were played widely in Europe, and he was hired to go to Russia as music director of Catherine the Great's chapel.

There he inaugurated an Italian dominance of Russian operatic life that lasted until Glinka's time; in addition, he introduced Western counterpoint into the music of the Russian Orthodox Church. Galuppi returned to Venice in 1768, resumed his duties at St. Mark's, and became chorus master at the Ospedale degli Incurabili. He phased out theatrical work, writing more keyboard music, sacred works, and oratorios.

Small in stature, he was described by the touring musical scholar Burney as an "agile little cricket" of a man. Burney also considered Galuppi one of the best operatic composers of the age, and the twentieth century's revival of interest in that era tended to confirm that opinion. His comic operas in particular are built of short, varied vocal phrases, with a strong melodic line and lively rhythms. He was adept at musical characterization and situational thinking.

His orchestration was notable; winds mark important moments, and in finales he allowed the flow of string writing to carry the main melodic material while the voices exchange dialogue realistically. Galuppi's keyboard music, including over 130 sonatas, shows a bright, idiomatic, and lively style of writing, and establishes him as a major Italian composer for harpsichord and piano after Domenico Scarlatti.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Bill Evans plays jazz Standards: Emily (sheet music transcription)

Bill Evans plays jazz Standards: Emily (sheet music transcription)

https://vimeo.com/527724824

EMILY - The Jazz Standard

"Emily" is a popular song composed by Johnny Mandel, with lyrics by Johnny Mercer. It was the title song to the 1964 film The Americanization of Emily. (The song wasn't sung in the movie, which is the reason that it couldn't be nominated for an Academy Award.)

It has since been recorded by numerous artists, notably Bill Evans, Tony Bennett, and Barbra Streisand.

Frank Sinatra recorded it twice, for his 1964 album Softly, as I Leave You and again in the 1970s for an unreleased album. His second recording was released on The Complete Reprise Studio Recordings.

Andy Williams released a version in 1964 as the B-side to his hit "Dear Heart" and it was also included in his album Andy Williams' Dear Heart (1965).

Jack Jones for his album Dear Heart and Other Great Songs of Love (1965).

Paul Desmond recorded the piece on his album Summertime.

Tony Bennett - The Movie Song Album (1966)

"Emily" became particularly associated with Bill Evans, who recorded it for the first time for his 1967 album Further Conversations with Myself. Evans also performed it live with saxophonist Stan Getz; it appeared on the album But Beautiful.

Barbra Streisand included the song on her album The Movie Album (2003).

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Time Remembered: INTERVALLANALYSE - Bill Evans

Time Remembered (Bill Evans): INTERVALLANALYSE

Es gibt vier Möglichkeiten, Jazz-Themen zu analysieren:

- INTERVALLISCH – indem wir das Thema Note für Note messen und den Abstand in der Tonhöhe benennen, gelangen wir zu jedem Intervall, das sich bei der Entfaltung des thematischen Materials bildet. Auf diese Weise hofft man, ein zugrunde liegendes Muster oder bestimmte Intervalle zu finden, die dem Thema seine Ausdruckskraft und Einzigartigkeit verleihen; Wir suchen dann nach den Richtungstönen (dem Hoch- und Tiefpunkt jeder Phrase). Diese offenbaren weitere Muster und Merkmale, die die „Form“ des Themas ausmachen.

- MODAL – durch Neugruppierung der Töne jeder Phrase bilden wir eine oder mehrere Tonleitern (Modi).

- O. HARMONISCH – indem wir die Töne mit der Harmonie in Beziehung setzen, suchen wir wiederum nach signifikanten melodischen Mustern und Farben.

- MOTIVISCH – indem die Phrasen in kleinere Einheiten namens Motive (melodische Zellen) und dann die Motive in kleinere Einheiten namens Figuren (Moleküle) zerlegt werden.

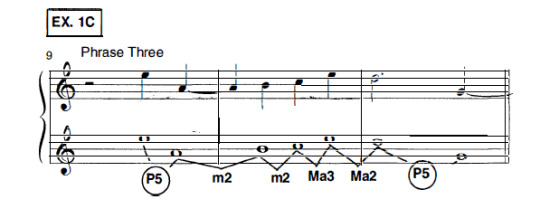

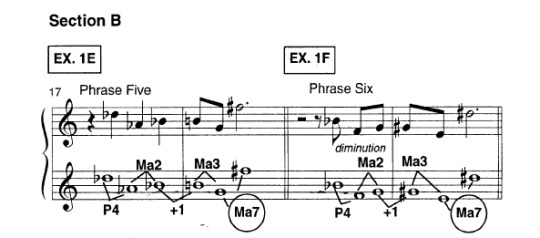

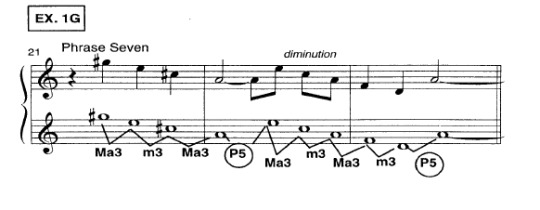

Da dieser Artikel Intervallbeziehungen behandelt, siehe EX. lA bis lH unten für die intervallische Aufgliederung des Themas (26 Takte, 8 Phrasen mit Unterteilungen).

Beachten Sie, dass das Thema in Phrase eins aus Intervallen von Moll- und Dur-Sekten besteht, die die Phrase durch eine perfekte Quinte in zwei Hälften teilen. Hier entsteht ein einzigartiges Muster; Die ersten drei Noten – „f#“, „g“ und „e“ – und die fünfte, sechste und siebte Note – „d“, „c#“ und „a“ – bestehen aus ähnlichen Intervallen, Sekunden und Terzen , wobei die Tonhöhe „b“ sie trennt und die Phrase beendet (siehe Klammern und Kästchen). Eine weitere Beobachtung ist, dass die Phrase mit einem Intervall einer kleinen Sekunde beginnt, aber mit einer großen Sekunde endet, ein sehr subtiler dramatischer Effekt.

Hier beginnt Bill mit einer perfekten Quinte und e_[lds mit einer perfekten Quinte, wodurch ein Gefühl der Ruhe entsteht; mehr Sekunden, Terzen und, beim ersten Mal, eine perfekte Quarte, die die Phrase in zwei Hälften teilt.

Jetzt haben wir zum ersten Mal eine Phrase mit drei Takten (eine andere Phrase mit vier Takten wäre hier eintönig). Perfekte Quinten beginnen und beenden die Phrase, mit nur Sekunden und Terzen dazwischen. Ein aufmerksamer Beobachter würde vermuten, dass dieser Ausdruck in 3er (1 + 1 + 1) unterteilt ist; Takt 9 beginnt mit einer absteigenden reinen Quinte („e“ zu „a“) und Takt 11 endet mit einer weiteren absteigenden reinen Quinte, aber dieses Mal von „d“ zu „g“!! Takt 10 ist die Überraschung: „b“ zu „c“ zu „e“, die genaue Umkehrung unseres 3-Noten-Musters in der ersten Phrase („d“ zu „c#“ zu „a“).

In der vierten Phrase erreicht Abschnitt A eine halbe Kadenz auf der Tonhöhe „c#“, der None des h-Moll-Akkords, dem gleichen Akkord, mit dem das Stück begann. Wir stoßen auf eine fünftaktige Phrase, eine subtile Erweiterung der viertaktigen Phrasen eins und zwei. Bill erreicht dies, indem er das „c#“ für einen ganzen Takt überbindet. Das war ein Geniestreich, denn ein geringeres Talent hätte das „cis“ bei Takt 16 nicht übersprungen und niemand hätte den Unterschied bemerkt. Wenn Sie mir nicht glauben, versuchen Sie, das Thema von Takt 1 bis 15 zu spielen, überspringen Sie Takt 16 und fahren Sie mit Takt 17 bis 26 fort.

Spielen Sie es nun noch einmal und fügen Sie Takt 16 hinzu. Was fühlen Sie? Rechts! Der Bedarf an SP ACE; eine Chance zu ATMEN, und Maß 16 ist der perfekte Ort. Außerdem treffen wir zum ersten Mal in Takt 15 auf ein Intervall einer großen Septime, ein sehr leidenschaftliches Intervall voller Energie und Spannung; Daher besteht die Notwendigkeit, innezuhalten, innezuhalten und zu atmen. Wie? Binden Sie das „c#“ für einen vollen Takt zusammen.

Zu Beginn von Abschnitt B komponiert Bill hintereinander zwei zweitaktige Phrasen, die beide die gleiche Intervallgliederung enthalten und die Spannung der vierten Phrase fortsetzen, indem sie auf einer Ma7 enden. Hier verkürzt Bill die Phrasenlänge, indem er Themenmuster verkürzt und das Thema auflöst, und das zu Recht. Dies ist die zweite Hälfte des Themas (oder Abschnitt B). Beachten Sie auch, dass das Intervallmuster in Takt 17 in Takt 19 rhythmisch schneller wird (VERMINDERUNG).

In dieser dreitaktigen Phrase kommt es erneut zu einer Diminution. Takt 21 beschleunigt sich rhythmisch in Takt 22, letzte Hälfte. Bei Takt 23 wird es sehr ruhig mit einer kleinen Terz („f“ bis „d“) und einer reinen Quinte („d“ bis „a“). Takt 23 buchstabiert auch den d-Moll-Dreiklang; Tatsächlich würde ein aufmerksamer Beobachter zwei weitere Moll-Dreiklänge in dieser Phrase bemerken: Takt 21, cis-Moll-Dreiklang und Takt 22, a-Moll-Dreiklang.

Satz acht ist voller Leckerbissen. Wir haben ein weiteres Beispiel für EXTENSION, aber dieses Mal gibt uns Bill Platz in der Mitte, indem er in Takt 25 auf der ganzen Note „a“ sitzt. Wiederholen Sie das Experiment, das wir am Ende von Abschnitt A durchgeführt haben, und Sie werden sehen (hören). ), dass wir Takt 25 nicht wirklich verpassen. Bei Takt 24 haben wir die intervallische Umkehrung von Takt 17.

Und zum ersten Mal haben wir in Takt 26 ein Beispiel für die retrograde Umkehrung von Takt 23! Phrase acht verflüssigt das Thema weiter, wobei die letzte Note sowohl als Leitton des h-Moll-Modus (hier enharmonischer Verbündeter geschrieben; die Originalpartitur hat ein B) als auch als perfekter „Umkehr“-Effekt für Takt 1 dient das 'f#' oder zu einer Improvisation.

Jazz sheet music download.

Time Remembered: Bill Evans Quintet

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-jMymWD8bcE

Personnel: Zoot Sims (tenor sax), Bill Evans (piano), Jim Hall (guitar), Ron Carter (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Bach, Prélude I en ut mineur, BWV 999 du Clavier bien Tempéré (Livre 1) partition, sheet music

Bach, Prelude I in C minor, BWV 999 du Clavier bien Tempéré avec partition, sheet music

https://vimeo.com/685836254

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Rachmaninow Klavier Concerto No 2 Op. 18 (komplett) Piano Solo arr. mit Noten

Rachmaninow Klavier Concerto No 2 Op. 18 (komplett) Piano Solo arr. mit Noten

1st Mov.

https://dai.ly/k59drP240HKuPWxHG5c

2nd Mov.

https://dai.ly/k51efuZGHG7TiyxHG4l

3rd Mov.

https://dai.ly/k3vRHDSIiCPrarxHFVU

Best sheet music download here.

Eine ausführliche Erklärung, warum Rachmaninows Klavierkonzert Nr. 2 ein unangreifbares, episches Geniewerk ist

Sie kennen sicher den zweiten Satz. Aber dieses ganze Konzert ist eines der größten Werke im Klavierrepertoire. Selbst in zurückhaltenderen Momenten werden Sie Ihren Kopf in Ihren Händen wiegen und um Gnade betteln.

Lassen Sie uns zunächst den Zustand von Sergei Rachmaninow im Jahr 1900 betrachten, als er mit der Komposition dieses gewaltigen Klavier-Meisterwerks begann. Er war vor ein paar Jahren in der Presse für seine Symphonie Nr. 1 regelrecht an den Pranger gestellt worden, und, um es milde auszudrücken, er war darüber ein bisschen verärgert.

Rachmaninow wäre nicht in der Lage gewesen, irgendetwas zu komponieren, wenn er nicht von einem Mann namens Nikolai Dahl, dem das Konzert gewidmet war, eine Derren-Brown-ähnliche Therapie erhalten hätte. Dank seiner Hypnotherapie war Rachmaninow wieder einmal in der Lage, großartige Melodien und knusprige Klavierparts herauszuhauen. Das zweite Klavierkonzert war Rachmaninows Comeback und, wie damals, als Take That als Männerband mit schlappen Frisuren zurückkam, war es ein riesiger kommerzieller Knaller. Genau das, was er brauchte.

Es beginnt mit nichts als Klavier

Mutiger Zug, Kap. Mutiger Schritt.

Dann wird der erste Satz zu einem Sturm verschiedener Themen, die das Klavier und den Rest des Orchesters in einem Strudel der Verbundenheit herumreichen, bis zum überragenden Ende, einem richtigen alten Geklapper in c-Moll.

Das Bit, das jeder kennt

Ach ja, der zweite Satz. Eine Epoche der Sentimentalität, der Höhepunkt der Emotion.

So sieht das geschäftliche Ende des kraftraubenden zweiten Satzes aus:

Es hat auch eine teuflische Kadenz wie diese:

Es geht jedoch nicht nur um den zweiten Satz

Das Finale ist ein Biest. Es gibt viel Fleisch, aber es lohnt sich, nur ganz am Ende einen kleinen Blick darauf zu werfen, wo die Geschwindigkeit plötzlich außer Kontrolle gerät und auf einen wirklich dröhnenden Höhepunkt zurast. Wie Sie sehen können, sieht es wie ein absoluter Albtraum aus:

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Oscar Peterson LIVE: Sehen Sie sich 10 Videos seiner besten Auftritte an

OSCAR PETERSON: Sehen Sie sich 10 Videos seiner besten Auftritte an

Table of Contents

Oscar Peterson Boogie Blues Etude LIVE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdd5pn1xs7M

Oscar Peterson LIVE In '63, '64, '65 (Jazz Icons)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_JrIcoFcnjE

Oscar Peterson C Jam Blues LIVE (1964)

https://vimeo.com/592413120

Oscar Peterson, Count Basie and Joe Pass LIVE at the BBC (1980)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HAZP7nWo6A

Oscar Peterson LIVE - The Berlin Concert

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8m41gQShXT0

Oscar Peterson Trio - LIVE at the INTERNATIONALES JAZZ FESTIVAL BERN (1986) Switzerland

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fFNOl5XVkE

Oscar Peterson meets Joe Pass LIVE concert.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uoqk6PHo9TM

Oscar Peterson - Boogie Blues Étude (LIVE)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdd5pn1xs7M

Oscar Peterson & Joe Pass - Just Friends by John Klenner (LIVE 1980)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yEu0ULY21UI

Oscar Peterson Trio LIVE - Wave (Vou te Contar) by Tom Jobim

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vUuB4UYe8nM

Jazz transcriptions and sheet music download here.

Oscar Peterson

Ein felsenfester Sinn für Swing, der auf Count Basie basiert, ausgeglichen durch einen zarten Ton und eine flinke Berührung, Oscar Peterson Peterson, Oscar Emmanuel Komponist, Leader, Pianist Born; Montreal, Quebec, Kanada, 15.8.1925 Gestorben; 23.12.2007

Oscar Peterson wurde von Duke Ellington einst als „Maharajah der Tastatur“ bezeichnet. Peterson war einer der produktivsten großen Stars in der Jazzgeschichte, seine Aufnahmekarriere erstreckte sich über fast 60 Jahre.

Unerklärlich und unentschuldbar ist die Tatsache, dass Oscar Peterson manchmal von überzeugten und spießigen Jazzkritikern herabgesehen wurde, weil er keinen eigenen Stil hatte. Während Mr. Peterson vor allem in seiner frühen Karriere von Nat King Cole, Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, James P. Johnson, Errol Garner und Art Tatum beeinflusst wurde, war es genau diese vielfältige Liste von Einflüssen, die seine einzigartige Art der Verschmelzung hervorbrachte Elemente aus Swing, Bop und Blues zusammen.

Oscar Peterson verfügte über unvergleichliche technische Fähigkeiten und seine leicht verständlichen und fließenden Darbietungen ließen seine Popularität als Pianist in gewisser Weise die seiner Vorgänger in den Schatten stellen.

Er war ein Mann, der innerhalb weniger Zeilen ein Klavier wie einen Löwen brüllen, wie ein Kätzchen schnurren, wie einen Bären stampfen und wie einen Schmetterling flattern lassen konnte und dabei nie ein Jota seines hervorragenden Swinggefühls verlor. Dan Morgenstern, Direktor des Institute of Jazz Studies an der Rutgers University, sagte: „Jeder Pianist, der nach Oscar Peterson kam, hätte zu ihm als Vorbild für vielseitige Musikalität aufschauen müssen.“

Oscar Peterson, ein in Kanada geborenes musikalisches Wunderkind, nahm mehr als 200 Alben auf und gewann acht Grammy Awards, darunter einen für sein Lebenswerk im Jahr 1997. 1950 gewann er zum ersten Mal die Leserumfrage des Magazins Down Beat; Er gewann ihn noch 13 Mal, das letzte Mal 1972. Von den 1950er Jahren bis zu seinem Tod veröffentlichte er manchmal vier oder fünf Alben pro Jahr, tourte häufig durch Europa und Japan und wurde zu einem großen Anziehungspunkt bei Jazzfestivals.

Norman Granz, sein einflussreicher Manager und Produzent, verhalf Mr. Peterson zu diesem Erfolg, indem er eine Flut von Platten auf seinen eigenen Labels Verve und Pablo aufstellte und ihn in den 1940er und 1940er Jahren als Favorit bei den Tourneekonzerten „Jazz at the Philharmonic“ etablierte 50er.

Oscar Peterson wurde schließlich zu einer Hauptstütze der Reihe „Jazz at the Philharmonic“, die Norman Granz in den 1940er Jahren ins Leben rief. 1949 wurde ihm keine Rechnung gestellt, als er mit der Wanderjazzshow sein Debüt in der Carnegie Hall gab. Granz holte ihn einfach heraus und sagte: ‚Spiel, was du willst, so lange du willst.' In dieser Nacht wurde Peterson zu einer Sensation, die seinen Ruf in den Vereinigten Staaten und bald auf der ganzen Welt zementierte.

Petersons Beherrschung des Klaviers an diesem Abend erstaunte die Anwesenden, darunter Charlie „Yardbird“ Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, Saxophonist Coleman Hawkins und Trompeter Roy Eldridge. Ein Down Beat-Kritiker schwärmte in der folgenden Ausgabe des Jazzmagazins von seinem Auftritt, und Peterson schloss sich der Konzertreihe bald auf einer Tournee durch Asien sowie 41 nordamerikanische Städte an.

1942 war Oscar Peterson in Kanada als „Brown Bomber of Boogie-Woogie“ bekannt, eine Anspielung auf den Spitznamen des Boxers Joe Louis und auch auf Mr. Petersons körperliche Statur – 6 Fuß 3 und 250 Pfund. Mr. Peterson wurde das einzige schwarze Mitglied des Johnny Holmes Orchestra, das sowohl durch Kanada als auch durch die Vereinigten Staaten tourte. In Teilen der Vereinigten Staaten stellte er fest, dass er, wie andere Schwarze, nicht in denselben Hotels und Restaurants bedient wurde wie die weißen Musiker. Oft brachten sie ihm Essen, während er im Bus der Band saß, erinnerte er sich.

Eine Zeit lang war Oscar Peterson so sehr mit Boogie-Woogie, einer populären Tanzmusik, verbunden, dass ihm eine breitere Anerkennung als ernsthafter Jazzmusiker verweigert wurde. Aber wie die Geschichte erzählt, war der Jazz-Impresario Norman Granz 1947 mit einem Taxi auf dem Weg zum Flughafen von Montreal, als er eine Live-Übertragung von Peterson hörte, der in einer Lounge in Montreal spielte. Er befahl dem Fahrer, das Taxi umzudrehen und ihn in die Lounge zu bringen. Dort überredete er Mr. Peterson, sich vom Boogie-Woogie abzuwenden.

Während seiner gesamten Karriere gedieh Peterson im Trio-Format. Seine vielleicht am längsten andauernde musikalische Beziehung hatte er mit dem Bassisten Ray Brown. Die beiden traten von 1950 bis 1965 normalerweise 15 Jahre lang in Trioform und gelegentlich im Laufe der Jahrzehnte sogar bis Mitte der 1990er Jahre zusammen auf.

Als Solopianist wurde Oscar Peterson manchmal dafür kritisiert, zu eng in der Tradition des 1956 verstorbenen Art Tatum zu stehen. Weitaus subtiler zeigte er sich jedoch als Begleiter von Sängern wie Ella Fitzgerald und Billie Holiday sowie Hornisten wie Louis Armstrong und Dizzy Gillespie. Mr. Peterson ist auch als Begleitung auf Alben von Roy Eldridge, Lionel Hampton, Stan Getz, Benny Carter, Lester Young, Harry Edison, Stuff Smith, Ben Webster, Sonny Stitt, Coleman Hawkins und Milt Jackson zu hören, um nur einige zu nennen.

Oscar Emmanuel Peterson wurde am 15. August 1925 in Montreal als Sohn von Eltern aus Westindien geboren. Sein Vater, ein Eisenbahnträger und Amateurorganist, drängte seine fünf Kinder zum Musizieren, schlug sie, wenn sie nicht gut spielten, und kritisierte sie gnadenlos, selbst wenn sie es taten.

Peterson erinnerte sich, dass sein Vater, nachdem er begonnen hatte, sich zu etablieren, einmal eine Tatum-Aufnahme mit nach Hause brachte und sagte: „Du denkst, du bist so großartig. Warum ziehst du es nicht an?' »Das habe ich«, sagte Peterson. „Und natürlich war ich fast am Boden zerstört. . . . Ich schwöre, ich habe danach zwei Monate lang kein Klavier gespielt, ich war so eingeschüchtert.'

Oscar Peterson begann seine musikalische Ausbildung auf der Trompete, wechselte aber mit 5 zum Klavier, nachdem er an Tuberkulose erkrankt war. Ein älterer Bruder, Fred, hatte Klavier gespielt und seine Liebe zum Jazz weitergegeben, bevor er an Tuberkulose starb.

Peterson sagte, er sei anfangs ungeduldig mit dem klassischen Repertoire, das von Pianisten in Ausbildung verlangt werde. Er sagte, er sei zugänglicher geworden, als ein privater Musiklehrer sein Interesse am Jazz begrüßte, das durch populäre Aufnahmen und Sendungen von Pianisten wie Tatum, Errol Garner und Teddy Wilson gewachsen war.

In seiner Schule spielte er in einer Band mit dem Trompeter Maynard Ferguson und sagte, er spiele gerne in der Mittagspause auf dem Stutzflügel, weil es „der beste Weg sei, ein paar Mädchen zum Runterkommen zu bringen. Ich wurde der Kerl.'

Mit 14 gewann Peterson einen Talentwettbewerb im Radionetzwerk der Canadian Broadcasting Corp., was zu einem regelmäßigen Engagement bei einem Radiosender in Montreal für eine Sendung mit dem Titel „Fifteen Minutes of Piano Rambling“ führte. Dies wiederum führte zu seiner bereits erwähnten fünfjährigen Tätigkeit in Johnny Holmes' beliebter Bigband.

1944 gab er sein Plattendebüt mit Boogie-Woogie-Versionen von „I Got Rhythm“ und „The Sheik of Araby“, und bald begann er, Stellenangebote von US-Big-Band-Führern wie Count Basie und Jimmie Lunceford zu sammeln.

Mitte der 1960er Jahre löste sich das Trio Peterson-Brown-Thigpen auf. Peterson blieb die Hauptattraktion in späteren Trio-Inkarnationen, darunter eine aus den 1970er Jahren mit dem Gitarristen Joe Pass und dem Bassisten Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen. 1974 gewann er seinen ersten Grammy für eine Aufnahme mit Pass und Pederson namens „The Trio“. Zwei Alben in den frühen 1990er Jahren, die Peterson mit Ellis und Brown wiedervereinten, gewannen ebenfalls Grammys.

Peterson gründete Anfang der 1980er Jahre ein Klavierduett mit Herbie Hancock, reduzierte sich aber später auf eine Soloshow, als er der Washington Post einmal sagte, er fühle sich harmonisch weniger eingeschränkt, wenn er alleine spiele. „Der Bassist würde sich immer fragen, wohin wir gehen“, sagte er.

Über das Klavier hinaus verzweigte sich Peterson als Sänger auf einem Tribute-Album von 1965 an Nat 'King' Cole, und Rezensenten stellten fest, dass er einen Gesangsstil hatte, der dem von Cole auffallend ähnlich war. Er schrieb auch mehrere ambitionierte Musikstücke, darunter „Canadiana Suite“ (1964) und „Africa Suite“ (1983). Er komponierte für Filme und moderierte mehrere Fernsehsendungen über Jazz, darunter 1974 eine für die British Broadcasting Corp. mit dem Titel „Oscar Peterson's Piano Party“.

Oscar Peterson spielte im Blue Note Club in New York, als er 1993 einen Schlaganfall erlitt. Er unterzog sich ein Jahr lang einer Physiotherapie, bevor er seine Karriere im Aufnahme- und Konzertzirkus erneut startete.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Miles Davis - 100 Masterpieces

Miles Davis - 100 Masterpieces

https://www.youtube.com/embed?listType=playlist&list=PLccpwGk_xup8EbuaOc_hm0Uc6bOKbO8By&layout=gallery

Read the full article

#sheetmusicdownload#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartitinoten楽譜망할음악ноты#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜망할음악ноты#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜망할음악нотыnoten#spartiti

0 notes

Text

Khachaturian Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia (piano arr.) Cyprien Katsaris, with sheet music

Khachaturian Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia (piano arr.) Cyprien Katsaris, piano with sheet music

https://vimeo.com/495039965

Sheet Music download here.

Spartacus ballet by Khachaturian

Spartacus, ballet in three acts by Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian, known for its lively rhythms and strong energy. Spartacus was premiered by the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in 1956, and its revised form was debuted in 1968 by the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow.

Khachaturian later adapted what would become his most famous ballet as a group of suites for orchestra, and, although the ballet remained a part of the Bolshoi’s repertoire, the suites provide the more familiar version.

The program of Khachaturian’s ballet (libretto by Yuri Grigorovich) was derived from a book by Raffaello Giovagnolli that details events in a 1st-century-bce Roman slave revolt; its leader, Spartacus, was a Thracian warrior captured in battle. The rebellion’s high point—literally and figuratively—was its seizure of Mount Vesuvius as a stronghold.

After two years of unrest, the rebellion was finally put down by Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Spartacus fell in battle. The surviving rebels, numbering some 6,000, were crucified along the Appian Way.

Khachaturian’s original composition was based on a narrative sketch that had been prepared earlier for the Bolshoi. It was not a great success, perhaps as much because of the choreography and the story as the music.

The 1968 version, with its contrasting moods of vibrant energy and gentle lyricism, was such a hit in Moscow that the Bolshoi took it on the road to Covent Garden the following year. By that time, the composer had already arranged orchestral suites from the ballet music so that Spartacus could reach the broadest possible audience.

Although Soviet authorities approved of the ballet, apparently seeing it as an allegory of the Russian people throwing off their tsarist oppressors, it seems quite possible to interpret its message as referring to Russians under communism rebelling against their own oppressive Soviet leaders.

Khachaturian, after all, had spent much of his life under the watchful eye of Joseph Stalin, and he had seen friends and colleagues disappear into the night.

SPARTACUS

SYNOPSIS

Spartacus is the dramatic story of the leader of a band of slaves uprising against cruel Roman rule.

ACT I

The military machine of imperial Rome, led by the Roman consul, Crassus, wages a cruel campaign of conquest, destroying everything in its path. Among the chained prisoners doomed to slavery are Thracian king, Spartacus and his wife, Phrygia. Spartacus is in despair. Born a free man, he is now a slave in chains.

At the slave market, the men and women prisoners are separated for sale to rich Romans and Spartacus is parted from a grief-stricken Phrygia, who is destined to join Crassus’ harem.

At Crassus’ palace, mimes and courtesans entertain the guests, making fun of new slave, Phrygia. Drunk with wine and passion, Crassus demands a spectacle. Two gladiators are forced to fight to the death in helmets with closed visors. When the victor’s helmet is removed, it is Spartacus, and he has killed his friend, Hermes.

In despair, Spartacus decides he will no longer tolerate captivity and incites the gladiators to revolt.

ACT II

Having broken out of their captivity, Spartacus’ followers call the local shepherds to join the uprising. Spartacus is proclaimed their leader, however he is haunted by the thought of Phrygia’s fate as a slave and he is drawn back to Crassus’ villa to find her.

Crassus is at his villa, celebrating his victories, however the festivities are cut short when Spartacus and his men break into the villa. Spartacus engages Crassus in combat and is at the point of killing him when, with a gesture of contempt, Spartacus lets Crassus go.

ACT III

Crassus is tormented by his disgrace. Fanning his hurt pride, his concubine, Aegina calls on him to take revenge.

Spartacus and Phrygia are happy to be together. But suddenly his military commanders bring the news that Crassus is on the move with a large army. Spartacus decides to go into battle but, overcome by cowardice, some of his warriors desert their leader. Spartacus’ forces are surrounded by the Roman legions. Spartacus’s devoted friends perish in unequal combat. Spartacus fights on fearlessly but, closing in on the wounded hero, the Roman soldiers crucify him on their spears. Phrygia retrieves Spartacus’ body from the battle field. She mourns her beloved and appeals to the heavens that the memory of Spartacus lives forever.

Read the full article

#noten#sheetmusicdownload#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜망할음악нотыnoten

0 notes

Text

Bach, Präludium I in c-Moll, BWV 999 aus dem Wohltemperierten Klavier (Buch 1) mit Noten

Bach, J.S. - Präludium I in c-Moll, BWV 999 aus dem Wohltemperierten Klavier (Buch 1) mit Noten

https://vimeo.com/685836254

Read the full article

0 notes