#sogant raha

Note

Sogant Raha is gorgeous. Do you have any recommended resources for worldbuilders who might want to do something similar?

no, because i did sogant raha all wrong.

it started as a Generic (albeit extremely low-magic) Fantasyland setting for a conlang when I was a teenager, which gradually accreted details at the edges until it was a whole world. but i didn't know what i was doing when it came to conlanging or worldbuilding, and as i got older and read more about historical linguistics, and history in general, i became dissatisfied with it and rebuilt it from the ground up a few times.

sometimes when you build a setting from the bottom up like that you miss the consequences of major decisions. when i started trying to map the whole planet for the first time, years ago, i realized i had put the Lende Empire on the wrong coast--for it to have a big forest to the east rather than be a massive desert, it needed to be upwind of the mountains, i.e., on their eastern side. so i had to either flip all the maps, on paper and in my head, or make the rotation of the planet retrograde. i opted for the second one, because reorienting my mental map of the Lende Empire would have been terribly confusing.

another example: i didn't realize how dramatic the consequences for the climate for having a low axial tilt would be until roughly, uh, yesterday. i just wanted to rough out some climate details and maybe calculate day lengths at different latitudes and seasons, and it wasn't until i started googling around to find formulas for average daily and annual insolation at different points on Earth that i realized low axial tilt produces a markedly different polar environment than what we're used to. the result is certainly more interesting, but it means there's some notes i have that are now just, well, wrong.

if you are starting a project like this as a big worldbuilding project, and you know a little bit about climate and astronomy and stuff, i think working top-down can save you from a lot of errors like this. damon wayans' worlds on Planetocopia are like this: but then, he seems to typically start with one High-Concept Worldbuilding Idea, and then see what the results are. i just had stories i wanted to write, that turned out to be connected, and gradually built the world up from them.

in some respects, this means as a world, Sogant Raha is not particularly exotic. the stories i wanted to tell are stories about humans, in societies not too dissimilar from ours, so the world is not too dissimilar. if i had known at 15 or w/e everything i know now (and had access to similar resources), i might have intentionally complicated certain parameters more, so that i could play with the results. but the stories are what has kept me coming back to this world year after year--and while an ice planet of methane breathers would be more interesting from a high-level view, i don't know what being a methane-breathing being on an ice plant is like, and i don't think it would have had the same perennial narrative appeal that has kept me interested all these years.

i guess my actual advice would be some or all of the following: be omnivorous in your interests. the fun thing about conworlding is that literally every domain of human knowledge is relevant to it. be willing to make weird choices, and equally willing to force yourself to justify them. sometimes you make an artistic choice, and you come back to it a little while later and go "what the fuck was i thinking?" you're tempted to erase it. but figuring out how to make that choice work often produces a much more interesting result. pay attention to what projection you're drawing your map in. try not to think in standard fantasy archetypes. no matter how original your spin on the ISO Standard Fantasy Races, they're still ISO Standard Fantasy Races. full blown conlangs are optional, but constructing even simple naming languages can make worlds feel much richer. don't use apostrophes in the names of things unless that apostrophe actually has a phonetic effect on the pronunciation. read a lot of history. real-world history is bigger and weirder and more interesting than you can possibly imagine. it's good fodder for worldbuilding.

#still thinking about slapping a big fat landmass in the ehyran ocean at some point#all that space is just going to waste!#sogant raha#worldbuilding#conworlding

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

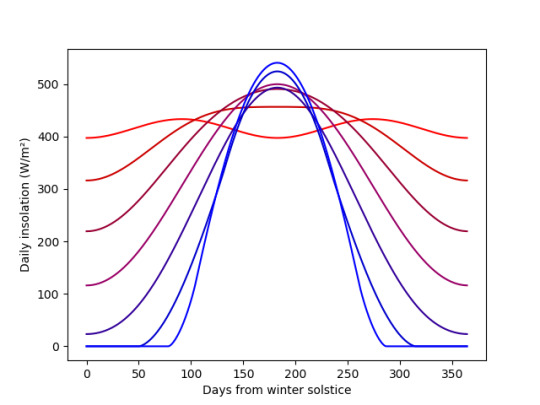

Sogant Raha world map

Below: the world of Sogant Raha with major landmasses labeled in bold and important subregions in italics.

And unlabeled:

Adwera and northern Rezana; to the west of Adwera is the Taicun Sea.

Démora and Tlucosse (to the east)

Altuum

Vinsamaren; the large central mountain range is the Arduinn Mountains, which meet the Kelrus Plateau in the north. The northeastern quadrant of the continent is a massive rain shadow desert.

#sogant raha#conworlding#tanadrin's fiction#note the planet's rotation is retrograde#and the axial tilt is fairly low#the two parallels just north and south of the equator mark the tropics

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are the (in-universe) politics of climate change in the world of Sogant Raha?

Climate change as such isn’t a major political issue in any era of Sogant Raha’s history, because industrial civilization with a population in the billions isn’t really a thing in any era of its history. The politics of environment and ecology, however, have been very important.

The first human civilization on the planet was technologically advanced but small; in the wake of the destruction of the Ammas Echor, they had to rebuild an industrial base on the planet, which took centuries and was never sophisticated as the one the ship had provided. Sogant Raha did not have as extensive and as accessible coal and oil deposits either, and certainly not in the regions of major human habitation during this early phase of settlement.

The major conflict when humanity arrived at Sogant Raha was, loosely, between those who wanted to approach the project of colonizing an alien world in an extremely conservative fashion, shaping human civilization to suit the environment as it existed, and those who believed that changing the environment was inevitable, and that it was both possible and desirable to seek a new equilibrium between humanity and the planet. Both factions were by our standards very environmentalist! With their religious background it could hardly be otherwise. But they disagrees (nearly to the point of civil war) on the actual program of settlement, and to what extent Terran species in the Great Record should be brought back.

That conflict was mediated by the Archive, in the form of Praxis, but this compromise lasted only as long as there was a unified political structure on the planet. That structure was based on the Ammas Echor and collapsed when the ship was destroyed. In the aftermath, colonization was unregulated and chaotic, a situation neither faction would have been happy with. Inevitably, humans profoundly altered their environment (and had to adapt themselves in turn). During the difficult centuries that followed, ecological concerns were only one of many different competing concerns for the fragmented polities of human civilization.

By the time of the Fifth Thalassocracy, a major industrial base had been rebuilt—think early 20th century, with zeppelins and steamships and railroads, though a much smaller global population, heavily concentrated in one hemisphere. But centuries of human population growth were provoking strange reactions in the native biota. New epidemic diseases were sweeping through the population; there were repeated attacks on the frontier by wild animals that nobody had ever seen before, some of which seemed like strange versions of Terran organisms; and the general feeling, especially at the margins of civilization, was that humanity was under siege by the alien ecology beyond its borders.

This period coincided with the second Continent-Archipelago War, which on its own would have been devastating; the use of new superweapons made it even worse. The war culminated in the unauthorized use of an experimental weapon that harnessed the latent energy within the Nexus strain of native microorganisms, and provoked a chain reaction in which the metabolism of native life went haywire. The disaster that followed, called the Burning Spring, was essentially a mass extinction. More than 90% of all land life died over the course of a couple thousand years. This death triggered atmospheric changes—carbon levels spiked for instance—but terrestrial life exploded to fill the vacated space left behind. But the rapid environmental change (and the devastation of war) also caused human civilization to collapse again, to a thoroughly preindustrial state.

The societies that eventually arose millennia later largely did not remember the history of what had gone before. They did not remember this was not the planet they were native to, and it would have been hard to notice. The actual native biota were confined mostly to slowly-shrinking refugia in the continental interiors, which were dangerous to approach—in the borderlands of those refugia, strange monsters roamed, virulent pathogens that caused hemorrhagic fevers and fulminant cancers were common, and almost everything that lived there was incredibly toxic to humans.

Ecology went from a matter of specific political concern to the background rhythm of thousands of different cultures. Each had their own way of thinking about the environment they lived in. Some saw themselves as stewards; others, as pragmatic exploiters. New urban civilizations with sophisticated modes of production would and did develop. Some even rediscovered some of their ancestors’ advanced technologies. But they were on a smaller scale, and while they might be intensely concerned with their local environment, global matters were not something they were in a position to understand or significantly affect.

(The Lende Empire, for example, was in its last centuries just starting to industrialize. But it wasn’t connected to a truly global system of trade, and while it had religiously-motivated environmental concerns, these were of a much smaller order than global carbon emissions. And they were expressed differently than how we would express our environmentalism: less ‘preserve natural ecology’ and more ‘don’t desecrate this sacred mountain range.’)

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

What type of genetic engineering have the humans of the Sogant Raha universe done to themselves for the long ship journeys? For example, I could imagine tweaks like can "produce vitamin C" (and maybe other vitamins) or "increased production of essential amino acids" would help with a lot of dietary problems (which would also be supplemented by engineered food sources). Anything else (visual spectral acuity, mutation resistance)?

A big class of genetic alterations necessary to survive particularly in the interstellar phase of civilizations involves low-gravity adaptation and a slower metabolism. The human body being able to develop properly in microgravity and not suffer precipitous loss of bone density means you don't have to have large rotating sections on your spaceship, which makes building interstellar craft much easier from an engineering standpoint. And it makes them much lighter, which is important when trying to cover massive distances using rockets! Other important genetic alterations are going to include resistance to non-infectious diseases (infectious diseases are pretty easy to control when your environment is entirely artificial), like cancer and degenerative diseases of the brain and nervous system.

Depending on the branch of humanity we're talking about, and how far into the exile, some of the alterations were more dramatic--radiation resistance, adaptation to low-pressure environments, major morphological adaptations (say, toward something more resembling our arboreal cousins, handy in low-gravity environments), and optional or even obligate parthenogenetic reproduction. Some, but by no means all of these genetic alterations would be reversed or the underlying genes silenced during the planetary phase of civilization. By the late exile, genetic engineering is skillful enough in some branches that you might have human populations for whom extended periods in microgravity automatically triggers a reactivation of spacefaring adaptations.

When it comes to the people of Ammas Echor specifically, a couple of generations after the ship had been launched from Rauk, almost all of its inhabitants were adapted genetically and physically to spacefaring life. This was mostly down to records of genetic engineering technology preserved aboard its predecessor Gyandamantu, which meant that the Ammas Echor's passengers didn't have to rediscover all of that themselves, but it was also down to a heavy utilization of cybernetic augmentation in addition to genetic alteration--these augmentations improved strength, helped regulate the metabolism, allowed for long-term hibernation to conserve resources, and helped to both avoid and heal major injuries, such that most of the ship's crew enjoyed a healthy lifespan centuries long, and many longer.

But few of these changes made it into the planetary population of Sogant Raha, since they represented overspecialization toward life in space--during the last century or so of final approach, the Archive considered reverting toward the more baseline form that had been common at Rauk. Attention also had to be paid to areas which had been long neglected by the genetic science of the Exile, like the immune system. Ultimately, the last couple of generations raised as they approached Kdjemmu were in some ways significant throwbacks--they possibly erred in reverting too far toward the baseline, but they were understandably worried about having children that would be totally unsuited to life in a complete, naturally-evolved biosphere.

The spacefaring type didn't go extinct overnight, though. Besides being long-lived, the Archive needed members to remain aboard the ship while it was in orbit and keep things running even as colonization began, and it was projected that the Ammas Echor would be the center of Sogantine civilization for a few centuries at least. Those Archivists who did venture to the surface had to do so in heavy environmental support suits. And when the ship was lost, the handful that remained would have lost the ability to maintain those suits if they broke down, much less create new ones.

Once the final Archivists of the spacefaring type died out, the Sogantine population would have been pretty close to present-day humans for the most part, with some key differences. Visually, they did not resemble any particular phenotype familiar to us. They lacked a propensity to most common genetic diseases familiar to us (though some of these, or new ones, might show up again in subsequent centuries). They were better adapted to childbirth--this is something Exile geneticists had worked hard at fixing, and weren't about to inflict on their children again--meaning much lower baseline maternal mortality rates. And the frequency of really negative recessive traits was reduced, meaning that despite being pretty genetically homogeneous during the Settlement period, the small population size was not as deleterious to long-term health as might otherwise be expected.

Sixty thousand years is a long time--long enough for plenty of new phenotypes to arise and for a moderate degree of divergence between widely-separated populations--but even quite late in the timeline, Sogant Raha mostly has less genetic diversity than Earth does today. Not that there aren't exceptions--the Dappese are outliers, far enough removed from other populations that pairings with them produce markedly lower fertility rates, and I haven't even begun to touch on the Cloud-Faced People.

#sogant raha#tanadrin's fiction#conworlding#worldbuilding#tumblr's spellchecker doesn't recognize either 'spacefaring' or 'phenotypes'#which is silly

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

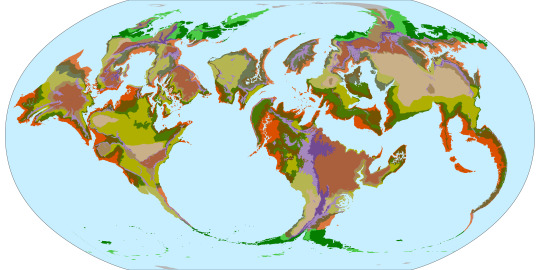

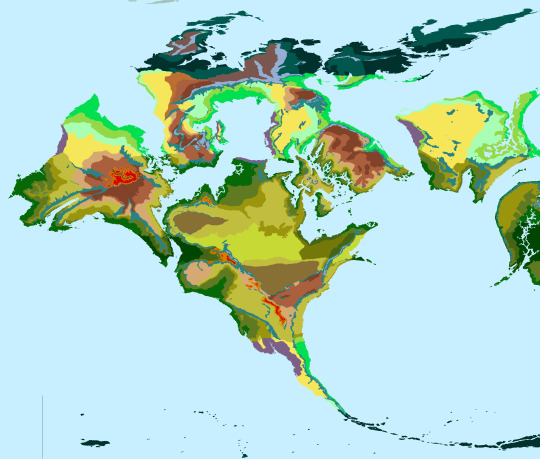

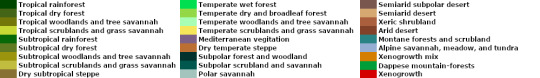

Bonus map: the biomes of Sogant Raha on the eve of the arrival of the Ammas Echor.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

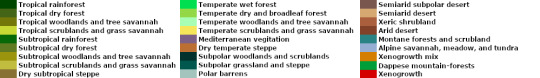

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Central Vinsamaren

Vinsamaren's climate and vegitation are strongly defined by the Arduinn Mountains, a vast range of uplifted sedimentary and metamorphic rock driven up by the collision of the West Vinsamaren Plate and the East Vinsamaren Plate. Among both the youngest and the highest mountains on Sogant Raha, the Arduinn Mountains bisect the continent from just north of the equator down past 60° S, well into the polar regions, with profound effects on both patterns of prevailing winds and rainfall on either side.

To the east, in the subtropical zone, the Arduinn rain shadow has contributed to the formation of the massive East Vinsamaren deserts, which are further anchored by the high pressure ridge at 30° S, the result of cool, dry air of both the Hadley and Ferrell cells sinking down from higher altitudes. South of the divergence zone, another rain shadow effect produces a large grassland region on the opposite side of the mountains, in further Tarun; this area is not quite as dry as the Great Deserts, thanks to the mountains to the north deflecting some moisture-bearing air to the southeast.

Northwestern Vinsamaren is dominated by tropical and subtropical forests; the windward southeast enjoys a more moderate, temperate climate.

The dense jungles of the northeast, plus the high Sayyedhar Mountains, and the extensive xenogrowth refugium on the northern margin of the Kelrus Plateau, effectively cut the northwestern coast of Vinsamaren off from the rest of the continent. Thus, culturally and politically, Vinsamaren has historically been divided into approximately five major geographical subdivisions: Sayyedhar (the northwestern coast); Velannu and the north desert margin; the south desert margin, the Gelar Sea, and the southeast; the southwestern grasslands; and Lende and the northwestern jungles.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

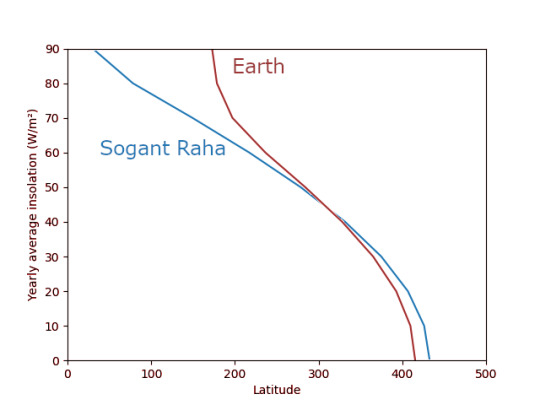

Climate of Sogant Raha: Insolation and Axial Tilt

Sogant Raha orbits a K-class star (Kdjemmu, or Col) with an absolute magnitude of around 5.8, and an intrinsic luminosity around 0.42 times that of Earth's Sun. Sogant Raha averages a distance of around 0.61 AU from its primary, and an orbital period of 0.546 Earth years. Its orbit has a low eccentricity, such that the time of year does not have a noticeable effect on the amount of sunlight reaching the planet.

The combination of these factors means that Kdjemmu is about as bright from Sogant Raha as our Sun is from Earth, and so--at least at the equator--receives about the same annual insolation. But the biggest astronomical difference between Sogant Raha and Earth is the degree of each planet's axial tilt: Earth's axis tilts at about 23.5 degrees, while Sogant Raha has an axial tilt of only about 4 degrees. This difference has substantial climactic effects.

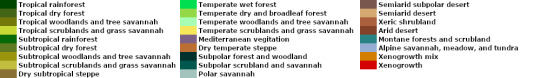

The most immediate difference is on the length of days at different latitudes. The length of days on Earth changes quickly and appreciably with latitude, depending on the time of year, as shown in the graph below.

[Length of days on Earth at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 85 degrees latitude. Actual length varies based on local topography, atmospheric conditions, and the definition of "day;" this chart is a mathematical approximation.]

On Sogant Raha, the length of days changes much less by time of year and only becomes very great close to the poles:

[Length of days at the same latitudes on Sogant Raha. Note that the rotational period of Sogant Raha is ~27.2 hours. A year is ~176 local days.]

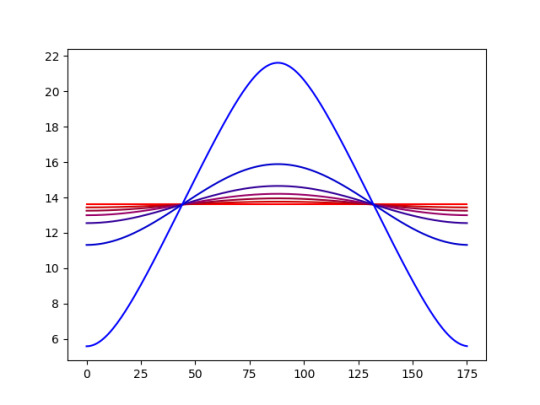

Earth's axial tilt and day length lead to significant variation in the average insolation received each day at different latitudes, which in turn drives significant seasonal variation in weather:

[Average daily insolation on Earth at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 degrees latitude.]

One important consequence of Earth's high axial tilt is that the poles receive substantial amounts of insolation during the height of summer; this insolation doesn't translate entirely to heat at ground level, because the high albedo of polar regions (due to clouds and ice) returns much of this energy to space, but the effect is notable. In contrast, with its low axial tilt, the picture on Sogant Raha is very different:

[Average daily insolation on Sogant Raha, at the same latitudes.]

Low axial tilt means much less seasonal variation; but it also means much less insolation overall near the poles, since, although Kdjemmu remains visible through the whole year, it is visible only very low on the horizon; topography can strongly enhance this effect.

These differences in average daily insolation have profound consequences for average annual insolation and thus for Sogant Raha's climate at high latitudes.

[Average annual insolation by latitude on Sogant Raha, compared to Earth. Note that Earth's poles still receive around 40% the sunlight than Earth's equator does.]

Above around 60 degrees latitude, the amount of annual insolation the surface of Sogant Raha receives is much lower than comparable latitudes on Earth. Near the poles, annual average insolation is around 10% the annual average insolation at the equator.

This difference in insolation is not the only factor determining local climate. Heat energy is dispersed throughout the atmosphere by convection currents in the atmosphere and by ocean surface currents--ocean currents from the mid-latitudes have a particularly significant effect on the polar climate, since neither of Sogant Raha's poles are dominated by large landmasses. Lack of ice cover further reduces the albedo of the polar regions, increasing their surface temperature.

Nevertheless, as a result of differences in insolation and temperature, Sogant Raha's temperate regions see frequent stormy weather; at high latitudes, life must adapt to much less available sunlight, and to cold year-round temperatures. Above 75 degrees or so, plant life is small and stunted; near the poles, the ground is almost totally barren. Even the xenoflora, which have had much longer to adapt to these conditions than the endoflora, can do little in an environment in which energy is so scarce; xenogrowth in these regions is limited to small patches of slow-growing mosslike organisms, or funguslike chemotrophs.

Humans have also adapted to the polar climate, as they have spread across the surface of Sogant Raha. Although the circumpolar barrens have no permanent human population, the larger subpolar regions are home to scattered groups, which migrate between the isles and subsist primarily on fishing, with fish oils being a crucial source of vitamin D in the low-light environment.

#sogant raha#tanadrin's fiction#worldbuilding#conworlding#i am not sure the daily average insolation chart for sogant raha accounts accurately for the longer days#but since the difference isn't very large#i think it doesn't have a huge effect on the result

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Map: the colonial empires of the seven major states of the Issaran Heptarchy. These states were Ferrense (yellow), Eytal (red), Obreya (blue), Kimar (teal), Asshar (orange), Nelente (green), and Segel (violet).]

The Issaran Heptarchy is the conventional name for a group of states in Issara, in southwest Rezana, that achieved prominence during the Andemoro Period, about six hundred Sogantine years after the collapse of the Lende Empire. Issara had been experiencing several centuries of political consolidation at this point, and also was connected to extensive maritime trade routes, many of which had been created by the Lende Empire and persisted after its fall. Of the nine or so major regional powers, seven were well-positioned to take advantage of those routes; though the principle concerns of Asshar and Nelenta always remained their overland empires.

Fierce competition between the Issaran states, which coincided with the introduction of ever-deadlier weapons, the first stirrings of local industrialization, and coalitional politics that prevented any single state from gaining a preeminent position, led the Issaran rulers to seek opportunities for territory and wealth outside their core territories. The first to do so was Nelente, which preyed on weaker states along the northwest coast, and Ferrense, which used its powerful navy to raid overseas, establishing what was basically a pirate empire in the ocean between the Gelar Sea and the Windlands. Issaran traders soon established themselves in Démora, western Vinsamaren, the more populous parts of Karei, and even Nebressa and Sayyedhu, though the highly organized states of the latter two regions prevented the kind of explicit empire-building that was possible in other regions. But by far the most profitable conquests were in Adwera, which became the focus of Issaran politics.

Issara had long had trade connections with Adwera to the north, mostly through intermediaries along the eastern coast of Rezana; when Kimaran traders sought to eliminate those intermediaries and acquire valuable Adweran goods directly, it sparked a particularly fierce four-way competition between Kimar, Obreya, Eytal, and Segel for dominance in the region. The outcome of this struggle was eventually total Issaran domination of the subcontinent. Only peripheral regions like the deep deserts of Shushtat and the Mosheri coast remained independent. The Adwerans, who were politically and culturally disunited to begin with, eventually banded together to drive out the Issaran invaders, a process that took around a hundred and fifty years of bitter warfare. The costs of this war, renewed fighting in Issara itself, and the expense of colonial projects that turned out to be boondoggles more often than not, eventually led to the decline of Issaran imperialism.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

how many protolangs did you design for sogant raha? are they the languages of the colonists from 60k(?) years ago, or did you start somewhere more recent? if you did start more recently, what is the justification? not in an 'i think you did this wrong' way, just that those languages are all descended from whatever ship's language eventually so there would be a gap in the history where language doesn't exist

so sogant raha didn't start as a grand design from first principles. it just sort of... accreted, starting with a nucleus of some worldbuilding ideas and early attempts at conlanging when i was a teenager.

as a consequence, some regions/periods are covered in much greater detail than others. the oldest and probably most in-depth portion of the project is the Lende Empire, which is actually located near-ish the end of the world's overall timeline (a few thousand terrestrial years before the "present"), while a lot of the stuff nearer the beginning (the varonar period, the continent/archipelago conflict, the Burning Spring) is of comparatively recent vintage.

all of which is to say, there isn't even a schematic diagram of the full history of languages for sogant raha, to say nothing of a protolanguage or set of protolanguages i derive all later languages from. i could do that, i suppose, but it would be wildly unnecessary: the comparative method can't reconstruct relationships at the range of 60,000 years, and the very often really struggles to reconstruct relationships more than a few thousand years old. (and from an artistic point of view, well, sometimes it serves creativity better to start with a phonaesthetic idea or just a bunch of random disconnected names and then only later try to work them into a coherent whole.)

i can say for sure that the languages of sogant raha don't have a monogenetic origin: the people of the Ammas Echor didn't have a single language, and the Sanda, who didn't arrive until after the Burning Spring, come from a completely different branch of the Exile.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Western Hemisphere

What we might call for lack of a better term "the western hemisphere" of Sogant Raha is composed of three smaller continents arranged around the Taicun Sea. They are Sarial, in the north (whose large southeastern subcontinent is Adwera); Rezana, in the south; and Karei, in the west.

Sarial is crossed by two major orogenic belts, one in the north and west, and one which descends the west coast of Adwera, cuts across the subcontinent in the region of Thana, and then follows the east coast south. Both lie principally within the temperate zone, creating large rain shadows to their west. Sarial is characterized therefore by relatively narrow, wet coastal strips, and a dry interior,

Rezana lies directly on the equator, and so by rights should be a continent of sprawling, humid jungles. And some tropical rainforests are found on the continent, especially in the far west--but the interior of the continent, although not quite as dry as Sarial, is still dominated by large grassland and steppe regions. Mountains (again, not as high as Sarial's), and large upwind continental landmass, limit the amount of moisture Rezana's interior receives. Still, prevailing winds do periodically carry rainstorms down from the Taicun Sea, and keep the heart of the continent from becoming a single large desert. If the Taicun sea were to dwindle in a future geological era, central Rezana would quickly become a vast, Sahara-like wasteland.

Karei has a very rugged topography, which combined with its higher latitude makes its interior the very dry desert that Rezana is not. Its coasts, however, are covered in lush forests; human settlement is particular dense in the east, where the population is part of the greater Taicun Sea cultural sphere, and in the south, where the people have a strong connection to the peoples of southwestern Rezana.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

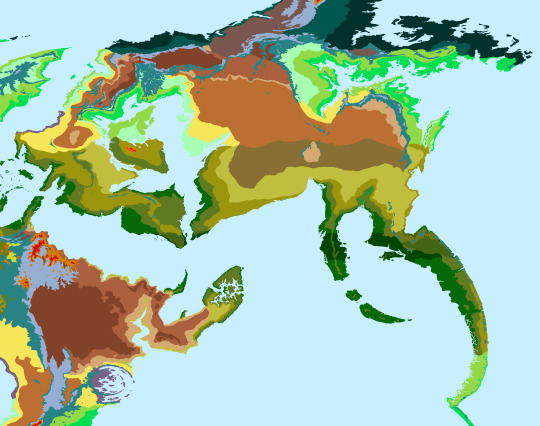

Biomes of Sogant Raha: Altuum

[Top: biomes of Altuum. Bottom: Major geographic subregions of Altuum labeled for reference.]

Altuum is by far the largest continent on Sogant Raha, containing both some of the planet's most densely populated regions and its most inhospitable environments.

Beginning in the southwest, Awlei and Nebressa are verdant subtropical regions that represent some of the oldest areas of human settlement on the planet. Prevailing winds off the Nebretzi Sea create thick forests on their western coasts, while the eastern half of these regions, sheltered by low mountains, are a little drier. The great inland sea keeps inner Altuum far more moderate in climate than it would otherwise be, and gives the large island of Iranda a fairly hospitable environment.

The northwestern and northern portion of the continent are dominated by a large cordillera that stretches almost to the north pole; these mountains create a large rain shadow in the inner regions of the continent. The Kurskanda Desert is particularly harsh, cut off from both the north and south coasts by high mountains, and is one of the driest regions on the planet. On the far side of these mountains lies the peninsula of Jenosha, which is by contrast wet and heavily forested.

The Conn Plain and East Altuum not only lie under the dry, high-pressure zones of the descending convection currents from the upper atmosphere, but are sheltered from rain-bearing prevailing winds by smaller mountain ranges. These factors together contribute to the formation of a large steppe region, which is historically a major barrier to the movements of peoples between western Altuum and the inland sea on the one hand, and the eastern coast of the continent on the other.

Most exchange of people and goods is, instead, by sea; prevailing winds in the tropics carry ships from Nebressa and eastern Vinsamaren east, while further south winds in the opposite direction carry ships west, particularly to the cities of southeast Vinsamaren and the Gelar Sea. The whole oceanic region enclosed by the bulk of Altuum to the north, the Windlands to the east, and Vinsamaren to the West thus forms a major network of cultural and commercial exchange, almost entirely irrespective of the era of Sogantine history in question.

The Windlands themselves have a subtropical climate not too dissimilar from the western coast of Nebressa; ports on the leeward coast connect to trade routes that span the whole eastern coast of Altuum, and which connect to western Karei, and ultimately to southwestern Rezana, on the far side of the Ehyran Ocean.

Note that East Altuum is home to a unique biome without parallel elsewhere on Sogant Raha, or on Earth: the mountain-forests of the Dappese.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Map: The Lende Empire at its maximum extent and the surrounding regions. Borders of neighboring non-ally states are not shown, though in this period almost the whole area covered by this map (save the very furthest eastern parts) was occupied by various statelike polities.]

The Lende Empire was a complex composite state throughout its existence, but by the Late Lende period its provinces, territories, possessions, and associated states could be grouped into several general categories.

Provinces were territories directly administered by the Empire's bureaucracy; these were divided into "sovereign provinces," which had their origin in the demesne territory of the Eju, and had special privileges, and "subject provinces," which were governed by the General Courts. By the Late Lende period, the sovereign provinces also selected their own senior officials, which were chosen by the General Courts in other provinces. The General Courts were divided in two: the Courts of Gaaizetsol administered the Eastern and Central provinces (red and teal in the map above), while the Courts of Unluis administered the Western Provinces and the seaborn republics.

Order possessions were the last remaining feudal territories, private possessions of the mystical schools or orders that had furnished warriors for the empire during its early years. Because their martial history was generally behind them by the time the western conquests began, almost all significant order possessions are found east of the Ejutaane.

Council provinces were subject republics granted a large degree of internal administration. Only the five largest are shown on this map. Lagara, Nejvir, and Gaurela were granted special charters when they were frontier fortress-cities; Iscelar was a state conquered by the Empire that was granted special status as part of the peace treaty; and Irdalais was incorporated by the request of its burghers, in return for exemptions modeled on Iscelar's.

Seaborn republics were mercantile enclaves founded by Lende merchants and sailors during the Late Lende period which had ambiguous status somewhere between overseas possessions and subject states. Escana and Caduis originated as filibuster expeditions by wealthy scions of the Orders with more money than sense; the others originated as trading outposts.

Domestic realms were conquered states or vassals that preserved a degree of autonomous self-government (usually run by local elites) upon incorporation into the Empire. Some domestic realms did eventually suffer being reduced to or annexed by provinces, usually as a result of local unrest; others were dissolved on their leaders' own initiative, since the rules of citizenship in the Empire were different for the people of domestic realms, and disfavored citizens who lived and worked outside their "home" territory. These rules were eventually relaxed, but only after considerable protest.

Protected realms or protected states were formally subject states that were not considered part of the Empire proper, but to which Lende had obligations (especially defense, hence the name), and whose citizens were granted special status within the Empire. The people of protected realms had most favored nation status when it came to trade, and were immune from alien taxes.

Frontier commanderies were essentially permanent military occupations, in regions that were persistent security problems (e.g., they produced numerous border raids or were strategically sensitive regions bordering hostile states). These regions were self-governing and the Empire made little effort to extract taxes, but were patrolled and garrisoned to prevent attacks on the Empire proper.

Tributary states were states that had obligations to the Empire, but to which the Empire had few or no obligations of its own. Relations with the tributary states were managed through a separate body of diplomats.

Permanent allies were states that had permanent general treaties of alliance with the Empire. By the Late Lende period, these were few, since Lende was the undisputed hegemon of western Vinsamaren. Utunnar was an ally ever since the Lende warrior Tavar of Narsaane had deposed its ruler and made himself prince of that city; it was dynastically closely connected with several powerful Orders, including Narsaane, and helped to defend Lende interests in northern Tarun. The Haq states in the north originated as client states set up in the wake of the destruction of the Haxar realm. And Aurila was the largest and most powerful of the Eilascer states, courted specifically to safeguard Lende interests in the north, and to ensure no united front emerged in Eilascer that would be detrimental to Lende power.

The vast size of the Empire ultimately limited the effectiveness of its administration, and projecting power into neighboring regions was expensive--during the later part of the Late Lende period, the Empire would slowly contract, reducing its presence in Kesh, Eilascer, and beyond the Umain Hills; its rulers would also, over the objections of numerous powerful factions, attempt to streamline and rationalize the administration, replacing domestic realms with "autonomous provinces," and fully abolishing the privileges of the Orders.

This process strained state capacity mightily, and unfortunately it did so as states on both the north and south frontier banded together to try to oppose Lende hegemony; major wars ensued. In the final few centuries of the Empire, although its external borders were not much smaller than shown in the map above, it was internally very fragile. Eventually, it fell to a cataclysmic civil war that resulted in the effective destruction of the state, at least as it had existed for the previous two thousand Sogantine years. Several successors sprang up in its place, but none with anything like the old empire's wealth and power. In the post-Imperial period, thousands fled--those that went east over the mountains became the Kuthra, a reclusive people who did their best to maintain their ancient traditions while making a living in the wastelands.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

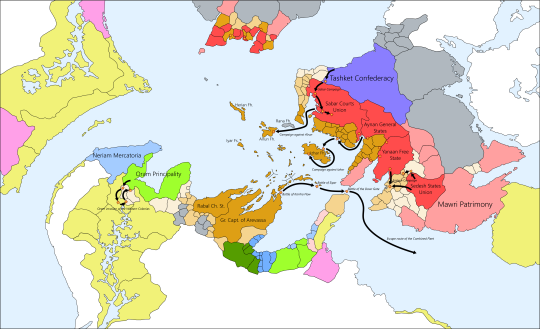

[Map: the belligerent parties of the Saihan War, in the primary theater of the conflict surrounding the Saihan Sea--known to later geographers as the Nebretzi Sea or Sea of Nebressa. Dark brown indicates the member states of the Fourth Thalassocracy, and lighter shades states that aligned with them as the war expanded. Red indicates states of the Continental Alliance, with lighter shades indicating states that aligned with them as the war expanded. Yellow indicates dependencies of Thalassocracy states, and purple dependencies of Continental states. Green and blue indicate factions of the parallel Kotrian War, which later became part of the Saihan War. States that maintained neutrality are marked in gray. The Tashket Confederacy switched sides no less than three times, and so is given its own color.]

The Saihan War (also known as the War of the Fourth Thalassocracy, or the Archipelago-Continent War) was one of the last great wars of the Varonar Period, the final phase of unified global civilization on Sogant Raha before the Burning Spring.

In the centuries since human settlement on Sogant Raha, complex and densely settled states had developed in the oldest inhabited regions of western Altuum, the so-called "ancient cities." Since the end of the last attempt to bring political unity to human civilization (the Great League of Harraska, also called the "Third Thalassocracy"), the larger states had fragmented under centrifugal political pressures and struggles to maintain central administration in the face of long-term economic decline. The economic and cultural center of gravity had shifted further westward, and now lay firmly in the isles; Izhar was now the largest city on the planet, while the Arevassan Grand Captaincy had trade networks that spanned nearly the entire globe.

Human civilization had continued to expand. This process of colonization, though it took place primarily by sea, did not much resemble colonialism as we think of it now; the colonies that states like Arevassa founded were not intended specifically either to create new markets, or to furnish goods for the industries of their metropole; nor, of course, were there large overseas kingdoms to be conquered. Rather, they were small settlements founded generally by associations of private individuals who hoped to acquire new land, or to establish new communities for specific political purposes, and which retained only loose ties to their founding states or cities. Nonetheless, the connections they had to their metropoles facilitated long-range trade networks once these colonies became self-sufficient, and there was a common cultural inheritance that generally facilitated durable political ties. Colonies made often-expansive claims of land which could rarely be enforced against competing colonists, but which were still often used for the purposes of negotiation. By this time, humans occupied every continent on Sogant Raha, though mostly only in scattered coastal enclaves.

Land-based expansion, as pursued by the larger states which had emerged at the frontiers of the original region of colonial settlement, was slower and more expensive. In part this was simply because it was expensive to move settlers and goods by land, unless there were navigable rivers available. But it was also because the regions of organized states were surrounded by diffuse populations living in stateless societies that resented the expansion of their ambitious neighbors, and had no desire to be integrated into their political or economic systems. A few, like the Tashket Confederacy, ultimately responded by organizing themselves to oppose outside encroachment, and eventually evolved into something like fairly decentralized states anyway; most resisted in a more unorganized fashion, or fled.

It was apparent to the rulers of most Saihan states by now that war was a far better bet when it came to enriching the state than trying to invest in local infrastructure; it was harder and harder to maintain the sophisticated infrastructure needed for the advanced manufacturing methods the original colonists had brought with them, and most industry had already shifted to cruder but more reliable technologies. But even then, there was a looming energy and materials crisis that would soon make even many of those technologies impossible to maintain; states like Rabal and Arevassa hoped through exploration to find the necessary resources to maintain these systems. States like Sabar, Aynan, and Yanaan (along with Sedesh, the core states of the "Continent" bloc) hoped to maintain their prosperity through other means--in the two centuries prior to the war, each passed laws binding certain classes of laborer to their place of residence and work, in effect creating new classes of serf, and Aynan in particular began to conquer independent peoples along the frontier and to use the captives thus acquired for public labor--essentially creating the first slaves on Sogant Raha.

Naturally, this horrified many of their neighbors; new treaties of mutual defense were hammered out, modeled on both the Harraskan League and the principles of the Second Thalassocracy. It was felt that the prevailing international norms that had effectively discouraged large-scale war for so long were no longer effective in the face of the ambition of these new expansionist states. This assessment was largely correct: although the legitimating principles of state power for the Continent continued to be, as for most large states, the upholding of the ideals and legacy of the founding colonists and the (nebulously applied) dream of working together for the prosperity of Paradise, the Continent states were facing a particular problem beyond merely the economic. They claimed to be particular inheritors of the legacy of the original colonists, but in fact their territory mostly lay outside the Ancient Cities. The Cities were now divided among dozens of small states which were wealthy and would in theory be tempting targets for conquest, except they had banded together and were under the protection of the new alliance, which self-consciously styled itself the Fourth Thalassocracy, and which considered the Continent mostly upstarts and ruffians. If the elites of the Continent states wanted to maintain their authority, and remain competitive against the likes of the Izharans and Arevassans, they had to demonstrate that they were the dominant force on the ancient mainland.

For about a century and a half in local years, this conflict was a simmering cold war, mostly carried out through diplomatic strong-arming, threats and bribes, and the odd act of assassination or sabotage; but both sides expected war and prepared for it well in advance. The Continent hoped it could force a quick surrender through a quick strike to seize a few cities like Izhar, demoralizing their enemies, and isolating those like Arevassa that were too far away to invade directly. The Thalassocracy prepared for just such an eventuality, terrified they might succeed. When the hammer fell, it was quite a blow--a combined force attempting simultaneous naval invasions of Alrun and Izhar, followed by a land invasion of the Thalassocracy members along the coast. Disunited as they were, the nominal advantage in manpower and production that the Thalassocracy states had seemed to matter little at first--they barely endured the first assault, and initially lacked the ability to counterattack, turning the war into a conflict of slow attrition.

Eventually, the Arevassan fleet won a decisive victory at sea, enabling the reinforcement of armies in western Altuum; the Continent roped in new allies like the Mawri Patrimony with promises of land at the expense of Thalassocracy colonies and allied states, and from there the war spiraled outward. Taking advantage of Rabali and Arevassan distraction, the Kotrian states attempted a land grab in their backyard; this side conflict eventually drew in the Oram Principality and the Neriam Mercatoria, bitter rivals that had been convinced to keep the peace only due to Arevassan and Rabali threats.

The war ground on for almost twenty years in the end; but finally, it was a total victory for the Thalassocracy. With the help of the Tashket Confederacy (whose loyalties had gone back and forth, but which eventually sided firmly against the Continent when Sabari plans for partition were made public) Sabar, Aynan, and Yanaan were fully occupied; Sedesh collapsed into civil war. The three northern Continent states were partitioned and integrated into an expanded treaty system; their co-belligerents were either disarmed, or (in the case of the Kotrian states) made into dependencies. The new political order was one, it was hoped, that could remain stable for generations. One troublesome detail stood out: after the victory, the combined Sabar-Aynan fleet had been interned at Karrha Flow, a naval base in Arevassa, awaiting a decision on its fate. Skeleton crews of Sabari and Aynan sailors manned the ships, and were loathe to contemplate the great battleships of their nations being divvied up among their enemies. The admiral of the fleet, a hardheaded and deeply patriotic Sabari sailor, ultimately led a rebellion that resulted in capturing the ammunition stored on shore, the fleet managing to shoot its way to freedom, and eventually, in one of the most daring acts of Sogantine naval history, to fight its way out of the Saihan Sea entirely into the Eastern Ocean, roaming the world as a pirate fleet, planning one day for their eventual return.

The view of the Thalassocracy was that the peace was harsh but necessary to prevent future warmongering. Unfortunately, it misread the facts on the ground: the occupation and peacekeeping forces necessary to safeguard the Fifth Thalassocracy (as the expanded treaty system was known) were expensive and required a great deal of manpower; the populations of the victorious powers did not have much enthusiasm for maintaining large militaries now that the conflict was over; the rulers of the new states were drawn from the old elites of the conquered states, in a move that it was hoped would pacify them but in reality left them plotting how they might regain their former power. And even after the occupation armies were eventually withdrawn (more than twenty years after the war's conclusion), a new narrative began to spread in mainland Altuum that depicted the Thalassocracy as oppressors and not defenders of peace, one that also found purchase in some of the cities that had in fact been fighting against the Continent when the war broke out.

Thus, the Saihan War was unfortunately not the last war of the Varonar Period. In its ultimate consequences, it was not even the most destructive. For although the Saihan War involved many more states and mobilized far more soldiers than the Orcalan War which followed, the latter would ultimately lead directly to the Burning Spring--leading ultimately to the complete collapse of human civilization on Sogant Raha, and a dark age which would last for thousands of years.

#tanadrin's fiction#originally this war (or one rather like it) was slated to take place on a completely different part of the planet#but i think this is the only one that has really the right geography#sogant raha

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

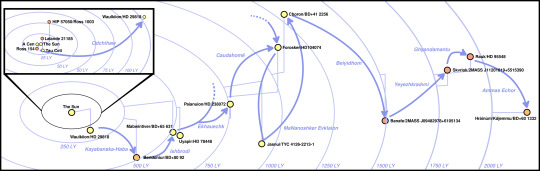

Of the Great Record

The exiles of Earth departed in numerous directions, some apparently random; and only later, around the stars nearest to the Sun, did the first common history of the Exile began to be written. One of the groups that the first humans to arrive on Sogant Raha trace their most distant direct ancestry back to those gathered at Lalande 21185, an M-type star about eight light years from the Sun. The genetic library of this exile was assembled from multiple smaller libraries on the dark side of Lalande 21185 b, and copies were made for all exile-ships which departed that star subsequently. The fate of these copies is unknown. Probably a large part were corrupted beyond usability, or were never brought to worlds where an Earthlike biosphere might be recreated. Undoubtedly the greater part served as a long-term store of useful genetic information, from which plants and animals useful to the Exiles could be resurrected after considerable genetic engineering. But intact libraries were not preserved in most instances, though in at least one case (the Yunamo exiles who came to Parsenor) the knowledge of the library’s existence was remembered.

In the earliest phase of the exile, it is probable that encounters among different branches of the exile were far more common. More ships (not many, but many compared to later epochs) could make the journey between inhabited stars, and smaller probes could be sent. From Lalande 21185 b and Alpha Centauri, two different expeditions were sent, at different times, to HIP 57050, hoping to find habitable worlds among the moons of that system’s two gas giants. These hopes failed; and though no descendants of these two peoples ever came back to Alpha Centauri, some did return to Lalande 21185, who were alerted to the existence of a successful colonization effort around Alpha Centauri A. They sent a small expedition there, with a copy of their genetic library, which the hastily-built Longshot (the vessel which had traveled from Earth, and had begun the settlement of that system) had been ill-equipped to carry.

Alpha Centauri A had three inhabited worlds; according to tradition, each built a ship when the time came to depart. Two were named (in a tongue remotely descended from modern English) Héu Frîa, “Hope of Spring” and Ijrtâ Lô Hlía, “Long Years of Dreaming.” Ijrtâ Lô Hlía traveled to Ross 154, where the ship was abandoned when the inner planets were settled. After about three thousand years of marginal existence, a great war drove a defeated people to reclaim Ijrtâ, which they refurbished, and hastily arranged to depart. They rechristened the ship, in their own tongue, Odchihaw, or “Time Awaited.” (< *Odotjiðawd < *Taaidh Udujttid, from the German) Ijrtâ/Odchihaw traveled to a star they called Waulkiion, and was driven aground on a moon of a large super-Earth with a dense atmosphere in that star’s habitable zone. This moon was eventually abandoned for the planet’s upper atmosphere, which was breathable. Uniquely among the planets the exiles had encountered at that time, the planet hosted an alien biosphere; but it was very inhospitable to humans, with crushing surface pressures and dark, devouring beasts. Eventually, a small community returned to the moon, and built Kayabanska-Haba, “Running Star” (< *Gaaivanzk-ava < Heyfãskur Avoni, from a language genetically descended from Spanish, but with less than 25% of the 21st-century vocabulary intact).

Kayabanska-Haba came to Beridoniur, at Áue-Saubhredi, and only five hundred years later--an exceptionally short sojourn in the history of the Exile--they built the Ishbrodi, “Flight Beyond.” Ishbrodi originally set out for a star called Uyapir, but during its flight doubt about the planet they sought caused dissension among the people of Ishbrodi. A rift developed between those who wished to continue to Uyapir, and those who wished to change course--an apparently suicidal thing to do--for the more distant star Mabwintiver. Violence broke out and the usurpers were successful; however, the ship was nearly destroyed in the journey, and by the time it reached Mabwintiver, most of the inhabitants were dead. During the sojourn around Mabwintiver, in the aftermath of the violent conflict that had troubled their ancestors, a strict religious-philosophical school was developed, which was influential on all branches of the exile that descended from that people.

The people of Ishbrodi built a two ships and left a part of their descendants at Mabwintiver; then Ishbrodi departed again. During Ishbrodi’s second voyage, it build a new ship, Ekhauëchk, “Forethought” (< Kawchak < *Hawthiak < *Awthiak, ultimately from the English, by about sixteen intermediate languages; even then, the language was impossibly ancient to the people of Ishbrodi, and preserved only in a few fragments of poetry). This was a very great deed: the building of a ship in flight was unknown in the history of the exiles, and has never been heard of since, because of the very great cost of resources required. What strife, fervor, or cataclysm incited the building of Ekhauëchk is not recorded. During its construction, the genetic library of Lalande 21185 was carefully inscribed onto every available surface of the ship. This may have been originally a ritual practice; but it had the distinct advantage of preserving that library in a far more durable (albeit less convenient) form. Ekhauëchk parted from Ishbrodi, and diverted to a star called Paianuion.

A very long sojourn then occurred, of more than seven thousand years. Nine ships were built in this time; the last and greatest, the pinnacle of the craft of Paianuion , was Caudahomë, which incorporated into its innermost sections an extremely elaborate form of the inscriptions which had decorated Ekhauëchk. Caudahomë journeyed to Forosker, which was already inhabited; thus two lineages were united that had been sundered for countless ages, which was a much-praised wonder. But strife arose among the people of Forosker after that, and there was also great sorrow. After two thousand years, descendants of the people of Caudahomë, with a small part of the descendants of the other peoples of Forosker, together built a ship called maNanoshker Evklaion, “Arrow of Time.” It took Caudahomë’s copy of the genetic library with it. From the other peoples of Forosker, the people of Caudahomë also rediscovered the technology of the so-called “universal cell,” programmable artificial tissue which could be used to grow living structures, which had long been forgotten among them.

MaNanoshker Evklaion then undertook a very long journey; though it had been well-prepared, it nonetheless nearly foundered between the stars, though at last it came to the binary system Jasnsui. But they found at Jasnsui no planet they could inhabit even for a little while; and this would have been their end, like so many exiles before, but they used the technology of the people of Forosker to preserve a large number of their people and radically alter the rest; and they succeeded in crossing from Jasnsui to Choron. MaNanoshker Evklaion was greatly expanded and rebuilt at Choron, and named Beiyidhom, which traveled to Banafe; at Banafe, Beiyidhom was taken in a new direction, while the old heart of maNanoshker Evklaion was incorporated into a new ship, Yeyezhkradvni, which journeyed to Skvriok. At Skvriok, a new ship was built, and the genetic library inscribed on its bones. This was Ghyandamantu, which traveled to Rauk. At Rauk, Ghyandamantu was abandoned for a while; and it was rediscovered amid a great war, and driven aground on the world of Usukûl, where its body was broken. From the ruin of Ghyandamantu, the Janese and Vergese peoples built Ammas Echor, whose name was from the line of the Buruyun prayer-book: “We wept and sang, and then at last, God heard our prayer.” It was Ammas Echor that came at last, after three hundred thousand years of exile, to Sogant Raha, which is Paradise.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I've wanted to do for a while is expand the graphical map of the Adwera EU4 mod. Originally it was just a 512x512 map, but that led to graphical weirdness when you zoomed out too much--EU4's map rendering functions weren't designed to handle the map tiling multiple times in the in-game view. I had an idea originally that I was going to render Adwera and northeast Rezana in detail, and give the rest of the world a sort of parchmenty map texture, but I couldn't get that to look decent. So in the end I decided to just render the whole world--or at least the middle latitudes--which also gives me the option to fairly easily alter or extend the playable area in the future beyond the current scope.

But it took a while. Even if you're filling most of the map with wasteland provinces, you need a heightmap, normal map, terrain file, colormaps, and trees file. Those last three also required having some general idea of the climactic dynamics (which are still on shaky ground, but I'm pronouncing them Good Enough for EU4 mod purposes). So this particular part of the project stalled out until recently.

If I were being really completionist, I would also do rivers for all the wasteland areas. But drawing rivers in EU4 is actually incredibly annoying (they have to be continuous lines in like a taxicab geometry sense, and tributaries have to be marked separately).

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, while you're answering SR asks---one thing that I wasn't clear on after reading through the tag. SR has a really _deep_ history of human civilization, tens of thousands of years or more, right? and it's definitely explicit that a lot of cultures have lost technology over time, or explicitly stopped "progressing" technologically (that one plateau culture), which is why it's bounced around basically the same tech level that whole time (with anachrotech pockets). But I'm not clear on _why_ that is.

Is it 1. that you're implying that this is actually likely to happen to any civilization on long timescales, and modern Earth monotonic progress is temporary, 2. that it's caused somehow by the semisymbiotic native SR life (some of the stories seem to imply periodic catastrophes driven by its influence? are those frequent & big enough to hold tech progress back overall?) 3. SR society Just Does That because of some combination of resource factors and social structures 4. something else?

Your intuitions are correct--there is indeed a reason for it! It's mostly the second thing.

But there have actually been two great technological stagnations in the history of humanity, and the longer and bigger one was before they arrived on Sogant Raha.

In order for the setting to work (mostly-terraformed alien planet), humans had to have some means of resurrecting species from genetic samples or records, but my intention was always that the beginning of the Exile is very much a near-future, or possibly alternate-present event: humans were forced to spread out among the stars by a catastrophe that made Earth at least temporarily uninhabitable, and they did so, at least initially, with crude Project Orion-type spacecraft, because that's all they had available. This universe doesn't have FTL travel, and Earthlike worlds are comparatively rare, so even when they settled in other solar systems, they did so in pressure domes and grew their food hydroponically.

This created a situation not incomparable to the Paleolithic phase of human history on Earth: extremely slow population growth, very little spare productive capacity, little room for experimentation or innovation. For the exiles who eventually arrived at Sogant Raha aboard the Ammas Echor, this era lasted about four hundred thousand years. The people of the Ammas Echor would have been more technologically advanced than the first exiles who left Earth, but not fantastically so. They simply did not have the resource budget for it. Nowadays, we can afford to invest in experimentation and in r&d that may not pan out; in an environment when even a small hit to your energy budget means people are going to die, you stick with the techniques you know for a fact work, and if you innovate, you do so slowly.

Once the Ammas Echor reached Sogant Raha, simply the fact they could walk around in an oxygen-rich atmosphere that was a comfortable temperature and grow food in any patch of open ground that got good sunlight would have been a phenomenal luxury. They certainly had the technology to grow quickly, and to rapidly innovate again. And they did aim to do that, at first (despite, y'know, centuries of hidebound traditionalism that come from hidebound traditionalism being the difference between survival and extinction of your whole lineage). But catastrophe soon struck in the form of a virulent disease that seemed to be caused by native alien microorganisms.

There were other catastrophes after, and some were human-caused (devastating wars, or environmental collapses like the Burning Spring). But many were not; many can indeed be traced back to the tahar, the genus of acytic symbiont that makes its home in the tissues and cells of endobiota and xenobiota alike. These have probably been equal to, or significantly worse than, many of the purely "human-caused" disasters. But the dividing line isn't always so clear; if an apparently random mutation in the tahar's signalling mechanism is, as a side effect, causing heightened aggression across a whole continent for a hundred years, then the wars that result might well be a human disaster, but in a purely causal sense they're not solely humanity's fault.

I think left to their own devices--if they had found a world without the tahar--the people of the Ammas Echor would have rapidly built up an industrial base and flourished. Indeed, they had a rather fantastical idea at one point to try to build a beacon to signal to other exiles that Paradise had been found. Alas, the planet had other plans.

#the technology in use in any given civilization#is probably kind of schizophrenic#what technologies and techniques survive a collapse#will depend heavily on what materials can be locally sourced#and what manufacturing methods are still possible#and scientific knowledge might actually be much greater#than the capacity to utilize that knowledge#sogant raha#tanadrin's fiction#worldbuilding#conworlding

13 notes

·

View notes