#that shaped who they became (still sort of want to play into my ''marx is a mirror of kirby'' hc from when i was little)

Text

i love kirby super star fanfic or comic adaptations where marx and kirby are actually best friends during the course of the entire game and marx blindsides kirby, to the point where i want to do something soooort of similar with my kirbyverse, but i also just kinda love how in canon marx was just like “im gonna very specifically ruin this guys week”

#i think marx is less outright evil and murdery and more ''i just want to fuck around with no one to stop me''#saw itsquakey say that marx seemed to be an antagonist more out of petty antagonism where he just wanted to play tricks with no backlash#and i gotta replay milky way wishes again to verify that bc ill admit i never paid that much attention to his dialogue but thats interesting#or at least it differentiates him from magolor a bit more#who more or less just outright wants to rule the universe#im torn on whether or not i want him and kirby to be besties tho#for one im like. so unsure if i want him to be the same age as kirby#bc ngl ive always seen marx as rather young so i saw him and kirby as being the same age at one point#and magolor was also the same as them. but now i firmly see magolor as like in his early 20s or so mentally#mayyybe a late teen at best? and i feel like if he and marx are gonna be a duo itd be cool to keep em the same age?#but then i want marx and kirby to be like. direct parallels in some way like idk. theyre the same age yet had totally different circumstance#that shaped who they became (still sort of want to play into my ''marx is a mirror of kirby'' hc from when i was little)#ig i could just also age up kirby but like youll have to pry child kirby from my dead hands#none of this matters ik its not like i ship marxolor or marxby or anything (anymore) but like idk#maybe im overthinking it LOL#idk tho basically idea is that marx and kirby are actually childhood best friends who've known each other since they were newborns#but like. besides that i have no ideas sdklfjsdlkfjsdlkfsd i used to have an edgy ass backstory for marx where his parents were murdered#and thats valid if you have something like that for his backstory but idk if i want to go that route anymore#bc marx is less villainous here and more ''i have no real moral compass and i want to fuck with people''#idk im throwing spaghetti at the wall btw nothing here is verified at all#echoed voice

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

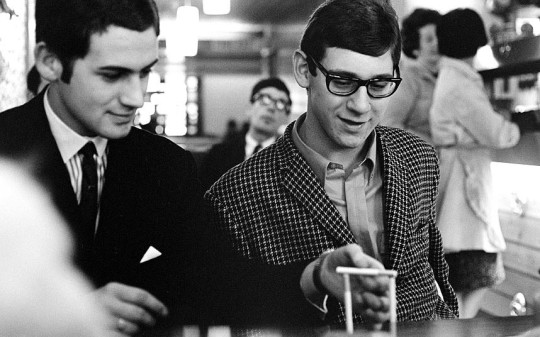

Talking to Jason Jules about John Simons, Patron Saint of English Ivy

In an age where everyone buys almost everything off the internet, sometimes from far-flung warehouses located in other countries, it’s easy to forget the important role certain brick-and-mortars played in shaping regional taste. These retailers, who were often small and independent haberdasheries, were the original tastemakers. Fred Seagal, for example, was once thought of as the gateway into the Los Angeles fashion market; Louis Boston introduced many to the comfort of Italian tailoring. In fact, Luciano Barbera got his start in marketing tailored clothing because of a suggestion from Murray Pearlstein, Louis Boston’s late proprietor. The two worked together to develop a line of ready-to-wear Italian suits and sport coats, which was initially aimed at the New England market.

John Simons is considered by some to be the patron saint of English Ivy for the same reasons. For the last sixty years, he’s been a steadfast evangelist for the same kind of clothes -- J. Keydge natural-shouldered jackets, Florsheim Imperial brogues, Bass penny loafers, button-down shirts, and other things Ivy. He introduced the look to English shores in the 1950s and has stuck with it ever since, proving there’s such a thing as classic style.

More importantly, he’s played an important role in shaping British taste. For almost three generations, mods, suedeheads, and skinheads (a term for a section of working class youths before the name became associated with racists) have gone to John Simons to look street-smart and well-heeled. John Simons was also the one who gave Harrington jackets their name. Originally referred to as golf jackets, Simons remembers the time when he climbed into his shop window to write on the buff-colored card attached to a store display jacket: "The Rodney Harrington Style.” It was reference to how Rodney Harrington in Peyton Place wore the same model. Now the name is everywhere.

This Monday, Mono Media is releasing a film about John Simons by Jason Jules. Some readers may recognize Jason as the face of Drake’s, but he’s also a vet in the London arts scene, having worked as a club promoter, PR rep, and fashion industry consultant. His film, titled A Modernist, is about a shop he loves, the clothing inside, and the store’s connection to culture. We sat down with Jason to talk about his film, Ivy Style, and other topics.

How did this project start?

I’ve known John’s shop since I was a kid. When it comes to Ivy Style, jazz, and modernism, John was Wikipedia before Wikipedia. Discovering his shop was a real eye opener for me. I was already into beat poetry and jazz at the time, but his shop pulled everything together. It has authenticity; it’s a place I can trust. I know if I go there with my eyes closed, pick up something from a rail in my size, it’ll always be the right thing. There’s not a single questionable item in the store.

Later, when I started making short films, it occurred to me that I should do something on John Simons. I put it off for a while, and then I heard a rumor John passed away. Thankfully, that turned out to be untrue, but the rumor kicked me into gear. What was originally supposed to be a five-minute nod to important influences in my life eventually grew into this hour-long feature on the shop and its clothes, as well the cultural attendants that came with them.

You mentioned trust. When I was a kid, I remember certain stores having an incredible amount of influence. If something was carried there, it was considered good. Do you think that’s still possible with the internet? Stores are so untethered by geography nowadays, people are constantly comparison shopping online. Loyalty seems like it’s at an all-time low.

I do, partly because I think certain stores offer a curational experience. I can walk past an art gallery, for example, and look at the work through the window. But that’s not the same as going inside and walking through the gallery, talking with the curator, and learning more about the pieces. Stores that give you a similar experience are the ones that will flourish. Think of shops such as Supreme or John Simons. Even if you go in there and get nothing but a conversation, you’ll walk out with something. You’re being exposed to a set of inherent values and taste markers that are almost too nuanced to grasp if you purely shop online.

John Simons has also historically sat in the middle of some important cultural movements -- his influence on mods, skinheads, suedeheads, etc.

John has a deep understanding of clothing, and he loves sharing it with people, regardless of their background. That’s one reason why there was, and still is, such diversity among his customers. He sold to kids who were into reggae and ska, just as he sold to advertising executives. He treated everyone equally.

That wasn’t always true elsewhere. There were some stores in Mayfair or tailors on Savile Row where, if you didn’t fit a certain archetype, you may have been met with a level of resistance or snobbery. John never did that; he welcomed everyone. He was never a mod or skinhead himself, but his clothes appealed to all those people. And he had a knack for putting his store in forward facing areas. At one point, he had a shop in the Soho area of London, just as the place was becoming an advertising hub. There were film companies and advertising agencies up one way, then music venues down the other. Right in the middle was John Simons’ Squire shop, so you got business people and music fans coming into the same store, buying the same clothes.

What do you think drew mods and skinheads to these clothes?

I think the clothes meant different things to different people. I imagine skinheads and suedeheads were reacting against the hippie movement at the time. There was a sort of neatness about the look that appealed to their working class roots, but the clothes also embodied a certain aspirational element. It was looking a bit more accomplished than what your wage packet might suggest. The early mods, on the other hand, often had good jobs and they liked dressing a certain way. But the appeal was still essentially aspirational – looking a bit outward at the time, as opposed to the more insular mindset of the previous generation of kids just coming out of the war.

That kind of sounds like the story of the ‘Lo Heads.

There are some parallels. I think the thing that makes it different is that John’s shop somewhat tempered what people wore. For example, as a kid, if I went into Ralph Lauren or Harrod’s, I knew I would be followed. It was a given, regardless of what I wore. Whereas if I went to John’s shop, I knew I would be welcomed. So for me, and I’m sure a lot of people, going to alternative sources to buy something wasn’t an attractive option. John shop was always the primary source in that way. That meant you interacted with the shop as more than just a retail outlet.

I remember in the ‘80s, I went into John’s shop to buy two Baracuta jackets. I wanted them a size too big, because that was my “look” then, and John told me the fit wasn’t right. I didn’t listen to him at the time because I was young and still finding my way with clothes, but his advice still stuck with me. The service made for a different kind of experience.

Many luxury companies back then worried about working-class people -- often ethnic minorities – wearing their clothes because they feared the association devalued their name. What made John different?

It was just the kind of people who worked in the shop. It was always about the clothes and culture. If someone showed an interest in the clothes and culture, they were eager to share their knowledge. And in many ways, they were also “outsiders.” John is a working class Jewish kid from East London. He has an outsider perspective. Some brands are protectionist, but John is an ambassador. Burberry used to vilify people who wore their check head-to-toe, but now they style their clothes the same way on the runway.

Or look at what’s happened with Dapper Dan!

Dapper Dan was public enemy number one for Gucci at one point, and now he’s hailed as the patron saint. There’s a new generation of marketing people, creative directors, and designers inside brands such as Ralph Lauren, Burberry, and Gucci that recognize the value of those outsider perspectives. John, on the other hand, has always been aware of this, so his door was always open to everyone.

In his book Ametora, David Marx wrote about how Ivy Style became its own thing in Japan. People wore things because their cultural heroes in Japan were wearing them, not because they were trying to imitate students at Harvard or Yale. Do you feel that happened with Ivy Style in the UK?

I think that a lot of people were into it in a purely contextual and insular way. After the first wave of modernists, the style was increasingly adopted by kids who wanted to emulate a mod look, and not because they were trying to be Italians. They wore those clothes because their mates were doing it. It becomes very peer-centric, very self-referencing in that way.

For example, I was asked a few years ago how long I’ve been into Ivy. I hadn’t even realized I was into Ivy! I was into button-down shirts and loafers and flat-front trousers. I was into patch pockets and cord jackets. I was into The Graduate and Steve McQueen. I was into Blue Note Records and modern jazz. I liked a certain look that could be defined as Ivy, but for me, it had a different meaning as a kid growing up in London.

Is there still that connection between clothing and culture? The Guardian had an article about how, fifty years ago, you could tell if someone was a mod, punk, hippie, goth, or soulboy from the way they dressed, but that’s harder now since so many people follow the same trends. Are there still youth subcultures that can be identified by the way they dress?

I think there are, but things move so quickly now, it’s hard to recognize something as peripheral. Like, Palace Skateboards used to be super niche five or six years ago. It was just a group of kids making t-shirts and crazy skateboard videos. Now they’re all over the place, and it’s easy to forget they came out of an incredibly small subculture.

Or look at Tyler the Creator and his line, Golf Wang. That originally came out of a subculture and the mainstream didn’t mess with it because they considered the line too obscure, too wild, too odd. Now they’re embraced like latter-day rockstars. It’s just that this transition happens so quickly now, it feels like things can become mainstream almost overnight. But the people behind these things were part of a subculture at one point.

Another brand like this is Trapstar. They started as kids who liked A Bathing Ape, but wanted something more local. They were West London kids who threw parties in other people’s shops and made incredibly high-spec’d t-shirts. They’re very authentic to London streetwear culture, but now their product is being sold internationally and sported by mainstream stars such as Rihanna.

Do you think the internet has homogenized or diversified culture?

I think it’s done both. It’s allowed people to find their own voice and realize there’s a community somewhere that will respond to them without any filter. But there’s also a lot of people who want to be part of a homogenous, mainstream culture. The internet allows for both of those things. I also think we all have both these elements in us. I like pop music, but also weird jazz. I watch Netflix, but also obscure films. The internet allows us to explore both these sides of ourselves, so they can happily co-exist.

Heritage clothing was really big five or six years ago, and now it feels like things have moved on. Is it harder to market this type of film now?

There was a point in the heritage movement where people thought there was a genuine shift in consciousness, that people would always buy less, buy better. Heritage turned out to be a trend, but it was an important trend. I’m not sure what happened, but like you say there was a palpable move away from what was essentially a style of clothing built around nostalgia. What remains of the trend, however, is a heightened appreciation of quality and craft, as well as a new kind of language, which we can apply to everything.

If you look at people who are into sportswear right now, they still talk about how things are made – the weight of the fabric on a t-shirt, how the print is applied. It’s no longer weird to talk about how denim was woven. Even sales assistants in high-street stores want to tell you how a pair of jeans was made.

So, in some ways, it’s become easier to talk about a clothing style that’s been around for more than fifty years. Mainstream journalists don’t look at you funny anymore if you describe your clothes as “Ivy.” At the same time, the social network for this stuff is a little more diffuse, but the people who really appreciate classic clothing will always appreciate it.

Do you think Ivy is ever going to come back in the way it did ten years ago?

I don’t know, but it’s like when the heritage thing was in full swing. Someone asked if I was pissed because all these people were dressing like me. “You’re looking like a trendy!,” they said. I said it’s fine because their interest in Ivy and Americana is a passing thing, for the majority of them, while I’m stuck in this. There will always be enough of us to have a community. This film isn’t for everyone, just as John’s shop isn’t. They’re for people who get it. For me, Ivy never went.

When I look at John Simons’ shop, it strikes me how the same clothes can look different in the UK than they do in the US. You mentioned the diversity among John’s customers, his acceptance and even embracement of others. At the same time, here in the US, Ivy style has lost some of its charm.

Part of that is because some members of the alt-right have picked up Ivy. The other part is how it’s become harder to ignore the uglier associations with the style. My co-writer Pete put it well a few years ago when he said “prep implies privilege and inherited money; some of prep’s charm comes from the unquestioning self confidence bestowed only by independent wealth.” The 1950s boarding schools and universities that originally made Ivy appealing are also the same places that discriminated against minorities around the same period.

Yet, in the UK, these clothes don’t feel like they have that baggage -- at least in the way they’re presented at John Simons. They have a different feel, much more modern and even democratic.

I know what you mean. For me, wearing these clothes, I always felt like I was in the process of subverting something. Even if it was just what it means to be a black kid growing up in London, being the only kid in the classroom wearing a button-down shirt. It was about subverting something that’s not supposed to be for you. But in some places, the look has been recast as the uniform of a social and economic elite. It’s harder to ignore how some people are not just taking advantage of their privilege, but even flaunting it.

Sometimes I think the heritage movement is partly connected to where we are now. I remember looking at a really important blog during that period, and they had a list of American-made products, authentic American brands. There were fifty to a hundred brands on that list, everyone from Pendleton to Woolrich, but none of them were Native American. I remember thinking it was so strange. We’re buying into something inclusive and liberating, but there’s also something nebulous around the edges. When Trump won, my girlfriend said, “you know Jason, part of what you’re into is responsible for this.”

[Laughing] A reader once emailed me saying that! He said my writing on clothing was partly responsible for the rise of the alt-right.

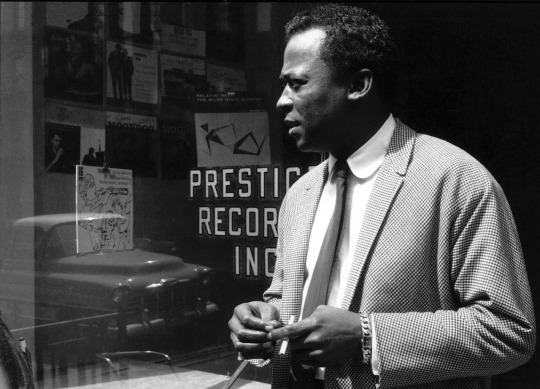

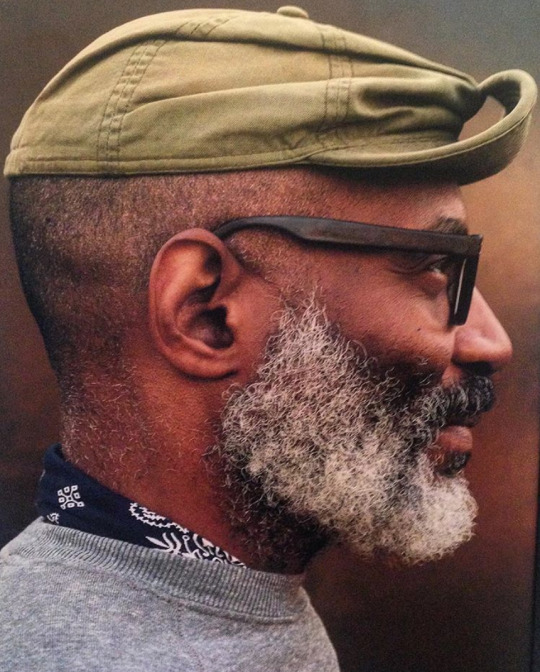

I think in recent years, I’ve become more aware of how my interest in Ivy differs from others. I’m purely into a look, whereas some people are into what a look symbolizes -- a sort of sanitized version of 1950s America. When I connect the clothes to culture, I connect them to personal heroes, who were often jazz musicians. Or things happening today, so it’s very contemporary for me. I don’t use these clothes to be wistful about the past.

One of the things that appealed to me is how people such as Muhammad Ali, Sidney Poitier, and Miles Davis wore the style. They looked great in Ivy. Fundamentally the style has always had a racial and socio-economic element, but today -- just as how Ali, Poitier, and Davis wore it -- what’s most important is how you interpret the clothes and how you wear them.

Thanks for your time, Jason!

Readers can purchase DVD copies of A Modernist through Mono Media (the film’s official release is Monday, April 23rd, but pre-orders are available now). Jason is also working on a new book about sneakers, which is slated for release sometime next year. He tells us it’s about where sneaker culture is going, as well as how it impacts the rest of culture -- social media, identity, luxury, consumerism, etc. You can keep up with John Simons and Jason Jules through Instagram.

youtube

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cerebus In Hell? #1

Cerebus is the only one surprised that he wound up in hell.

See? Like this!

Thinking back to Dave Sim's rants about feminism and men in monogamous relationships with women, it strikes me that Dave Sim was sort of a precursor to Gamergate and the rise of the Men's Rights Activists. But funnier!

The comic is set up like a weekly comic strip. Each page is a four panel joke with Cerebus interacting with a famous painting. At least I'm assuming they're famous since I know nothing about paintings!

This one made me laugh out loud.

Dave Sim always had a great ear for comedic dialogue. His Groucho Marx (as Jaka's Uncle Julius) was as funny and absurd as the real thing. His Cockroach parodies of superheroes were sharp and shaped with an obvious young love of the comics he was satirizing. And I will forever be disappointed with just how little Elrod of Melvinbone there actually is in the six thousand pages of Cerebus.

There's really not much more to say about this. If you like Cerebus before he became a boring religious-minded fuck, you'll probably get a kick out of this. If you're not whimsical enough and you know you'll whinge on about the entire thing being recycled artwork with speech bubbles stuck on, you should pass on this. Also, if you wrote Dave Sim off long ago because he was a total nutter and almost certainly a misogynist, you probably didn't even find the panel funny where the guy under the rocks is still using his watch.

1 note

·

View note

Link

A review of Stolen: How to Save the World from Financialisation by Grace Blakeley, Repeater Books (September 2019) 300 pages.

It is tempting for Jeremy Corbyn’s critics to write off his electoral promises as bribes—a last-ditch attempt from the most unpopular major party leader in memory to buy his way to victory. There’s some truth to this when it comes to pledged levels of public spending. But Corbynism is not an opportunistic ideology. He and the people around him have a set of beliefs about the economy that they take very seriously, and it’s worth trying to understand them.

Stolen: How To Save The World From Financialisation, by New Statesman columnist and socialist campaigner Grace Blakeley, is one of the more serious attempts to set out a version of Corbynism (compared to, say, Aaron Bastani’s buffoonish Fully Automated Luxury Communism). Blakeley, who recently tweeted that reading the Labour manifesto had moved her to tears, has tried to put modern leftism in a post-financial crisis context. Her book hopes to explain why she believes the crisis was the inevitable consequence of Thatcherite neoliberalism, and why now, more than ever, the time is right for socialism.

Blakeley focuses on what she calls “financialisation,” a term that means different things to different people but which she takes to mean the use of private financial markets as the dominant mechanism for allocating money for lending and investment, instead of, say, government agencies. She blames the rise of finance for two related evils: one, diverting investment away from industrial production towards speculation on things like housing and company shares, and two, bond markets forcing governments to adopt free market economic policies, or face higher borrowing costs.

Her story begins at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, at which delegates from the Allied nations, including a British delegation led by John Maynard Keynes, designed the system of global currency that would last for thirty years. What they came up with was a loose peg to gold intended to prevent sudden large fluctuations in exchange rates but allow more flexibility than a true gold standard. This, according to Blakeley, kept financial markets in line by preventing large capital outflows and by restricting the supply of credit. This allowed the “Keynesian consensus” to emerge—a sort of moderate, worker-friendly capitalism characterised by generous government spending, an economy based on manufacturing output, and strong unions that could maintain some balance between the interests of workers and capital-owners. Not a Marxist’s paradise, but hardly the stuff of nightmares.

That didn’t last long. In the early 1970s, the oil crisis hit, Bretton Woods was abandoned, and true capital mobility arrived—what Blakeley calls “vulture capitalism.” The Keynesian settlement became a victim of its own success, with unions capturing so much of the product of industry that capital-owners “revolted” and pulled their money out of places like the UK, leading to industrial strife that eventually brought Thatcher’s radical free marketeers to power. Blakeley only spends a few pages on the 1970s, even though this was precisely the point where everything, from her point of view, started to go wrong. The 1970s, she argues, highlight the “contradictions of social democracy,” because as unions grew in power, capital-owners still had the freedom to move their money elsewhere. (Readers with a deeper knowledge of the strikes and shortages that led voters to gamble on Thatcher may find Blakeley’s version of events to be less than the whole story.)

Under Thatcher, Blakeley’s thesis takes shape. By encouraging mortgage-funded home ownership and bringing in the “Big Bang” deregulations that led to the growth of the City of London as one of the centres of global finance, Thatcher’s government began the financialisation that Stolen purports to be about. Blakeley believes that Thatcher’s crushing of the unions was what made this possible: “Without resistance from the country’s workers, she could go about entrenching neoliberalism and empowering the financial elites that had brought her to power.” Debt rose, asset prices grew, and the financial sector became responsible for allocating more and more resources across the economy. Without state support, and with capital now being allocated according to profit-obsessed financial markets, industry across much of the UK collapsed. As more and more voters became property-owners, their interests shifted from being aligned with workers to being aligned with capital.

We then skip ahead to 2008. After twenty years of growth, which Blakeley describes as largely “illusory,” the bubble bursts. House prices, which had risen and risen thanks to easy borrowing, fell sharply in much of the developed world. This caused banks that had lent money for mortgages, and others that had repackaged those mortgages into tradable financial instruments, to collapse. The bubble burst, the system (almost) collapsed, and the inherent contradictions in debt-financed capitalism were exposed for all to see. It was these developments that precipitated the landslide election of lifelong socialist backbencher Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the British Labour Party in 2015.

If that story sounds new to you, Stolen may be a useful book. It offers a fairly readable account of this account of postwar economic history, and it does so at a brisk pace. If, on the other hand, you have some cursory knowledge of the events of 2008 and the years that followed, much of it will feel reheated and oversimplified. Blakeley repeatedly digresses into discussions about some aspect of Karl Marx’s thought, and why the events she has just described demonstrate that Marx was right about something or other after all. In the first chapter’s explanation of Marx’s theory of history, she describes a debate within Marxist circles about whether “Marx prioritised economic structures in his analysis of historical development, [or whether] he prioritised agency.” It turns out he believed in both: “the nature of technology and the economy provides the overarching context in which human action takes place … But they do not determine human action.”

This is a surprisingly anodyne version of Marxist history. Does anyone disagree that “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please,” as Blakeley summarises her mode of analysis? It soon becomes apparent that she is less interested in “financialisation” as a phenomenon in itself than she is in using a relatively recent feature of capitalism to demonstrate an old Marxist claim: that capitalism sows the seeds of its own destruction. Readers hoping to understand how finance affects the “real” economy will be disappointed. Here, finance merely plays the role that “capital” did in the nineteenth century: as the rapacious, faceless force that proves capitalism can never really be sustainable.

Blakeley’s analysis is often misleading. What she calls a housing “bubble,” in Britain and the US at least, does not seem like one with the benefit of another ten years of evidence. House prices in both the UK and US are higher now than they were in the years leading up to the crisis—when “bubbles” burst, they do not tend to return to their old values within a few years. (A house in central London is now much more expensive than it was even before its “bubble” burst. A share in Pets.com is not.) Blakeley suggests that this is just a sign of another bubble, a claim which (for now) it is impossible to make with any certainty. It seems a lot more likely that climbing house prices are driven by planning restrictions that limit the supply of housing in large cities, combined with economic prosperity that attracts new workers and higher wages with which to bid up the price of the existing stock of homes.

If this were not the case, and mortgage borrowing were the main culprit, we would expect to see house prices inflated by roughly the same amount across the country, not largely confined to places where people most want to live and where supply is most inelastic. In Tokyo and Houston, for example, which have relatively permissive laws about the construction of new housing, economic growth and historically low interest rates have still not led to significantly rising house prices.

Blakeley has been criticised for misusing terms like “bank capital,” which have a precise meaning that her text seems to misunderstand (she appears to be mixing bank capital requirements up with liquid assets and reserve requirements, for example). But, while these may reveal some fundamental misunderstanding of the things she is writing about, it may also be the result of hasty editing or an attempt to translate technical terms for laypeople. Much more troubling than some garbled definitions is the frequency with which Blakeley makes claims that have no basis in evidence, and for which she provides no citations.

Blakeley claims that productivity and worker compensation have decoupled, disproving a core tenet of mainstream economics—that workers will tend to be paid according to their marginal product, so strong unions are not necessary to ensure they capture a share of economic growth. But the data show no such decoupling. There is evidence that workers are being “paid” increasingly in forms of compensation other than wages, like pension contributions and, in America, health insurance contributions. But these simply change the mix of how workers are paid, and are mostly driven by changes in regulation. I may prefer to be given £1,000 in cash to an equivalent contribution to my pension, but it is hard to argue that the latter is not really payment to me.

Similarly, she claims that “people are having to work ever harder to maintain a lower standard of living.” Despite the fall in living standards after 2008, this is simply not true. GDP per hour worked may have grown anaemically since the crisis in Britain, but it is still higher than it has been at any point in history (and inequality has not risen in this period). It is just wrong to suggest that living standards are falling—but it is the sort of claim that Blakeley has to make in support of her insistence that “we inhabit a revolutionary moment.” If living standards are historically high and growing, just not growing as quickly as we’d like, the case for revolutionary upheaval is weak.

She also repeatedly makes claims about “illusory” debt-fuelled growth, including the extraordinary assertion that “during the pre-crash period, unprecedented levels of lending were the only thing keeping the US economy going.” This declaration is unsupported by a citation and has no basis in fact. The most charitable reading is that it is Blakeley’s opinion and she simply doesn’t think that certain forms of economic growth really count. But it is also circular—we know the crash was inevitable because the growth was illusory, and we know the growth was illusory because of the crash.

Stolen promises a guide for “saving the world” from this financialisation, but Blakeley’s policy recommendations do not inspire confidence. Borrowing from the recent People’s Republic of Walmart, she points out that businesses are themselves centrally planned, and so it should not be counterintuitive to run a country along the same lines. This completely misunderstands how businesses and markets work. Businesses exist within a system that is generally designed for the ones with bad internal planning to collapse as swiftly as possible. Effectively, we get to choose between the most well-planned companies and, unless we have lent to, invested in, or work for a company that goes broke, we are largely insulated from the ones that fail. (This is one reason why we provide unemployment insurance to people who do have the misfortune of working for a company that fails, and why bailing out large banks sets such a bad precedent.)

For such a system to work for entire states it would need to be just as easy for families to migrate between countries as it is for workers to migrate between employers and for consumers to choose between different businesses. In practice, of course, the unfortunate citizens of centrally planned economies have often tried to migrate away, and had to be fenced in with barbed wire, or worse. Blakeley does not discuss the real world experiences of the sort of system she proposes, but she does recognise that investor flight is as much a challenge for centrally planned economies that get it wrong as it is for businesses.

To solve this, she recommends measures that will not sound alien to anyone familiar with the bolder elements of Corbynism: capital controls on taking money out of countries, measures to regulate banks and establish a nationalised retail bank, a “Green New Deal,” a sovereign wealth fund, and part-nationalisation of industry along “democratic socialist” lines, where businesses are controlled by unions of their workers rather than capitalists. This last idea has made its way into the Labour Party manifesto, although Labour says it only wants to nationalise ten percent of each business affected, for now.

Stolen is a wasted opportunity. Blakeley’s determination to vindicate Karl Marx means that much of the book feels like it has been generated simply to add new meat to some very old bones. This is a pity: there is plenty of merit to the materialistic Marxist analysis of history, and such an approach may have added something new to our understanding of the post-Thatcher era. But there is nothing like that here. There’s very little attempt to persuade the reader of the value of Marx’s thought, either. Blakeley’s assumption seems to be that you are either already a Marxist, and therefore predisposed to regard any invocation of Marx as authoritative, or that you are totally unfamiliar with Marxism, and any other theory of history, and so a simple explanation of what Marx thought is sufficient to persuade you of his prescience.

Blakeley writes engagingly, although she leans too heavily on clichés (the “yawning” trade deficit is driven from the City’s “gleaming towers”; the “moment of crisis” she describes could also be “a moment of opportunity”). It is footnoted thoroughly, and contains an impressive understanding of mainstream analysis of the crisis—indeed, this is the book’s most informative and coherent chapter. But this also makes the rest of the book feel shallow by comparison.

Had Stolen been less slavishly devoted to Marx, and taken a narrower focus, Blakeley might have better explained her own views and their relevance to contemporary readers. But more time is spent discussing coal mining than, say, the internet and what her thesis tells us about tech giants like Amazon and Apple. In many ways, it is a book that feels badly out of date, and it is unlikely to be of interest to many people beyond those who already agree. Worse, it is riddled with exaggerations, unevidenced opinions, and dubious claims presented as indisputable facts. Halfway through, Blakeley tells us that “There is, of course, no such thing as neutral economic analysis.” Stolen is certainly evidence of that.

RayAndrews

“Despite the fall in living standards after 2008, this is simply not true.”

It sure seems true. If you live among working people they will all assure you that it is true. Debt rises, jobs with pensions are almost a thing of the past, zero-hours contracts are the new normal, home ownership is a distant dream, young couples can’t begin to think about having a family. What’s that statistic? Half of American families could not meet a $400 emergency? No one I know below the age of 50 has savings. Then of course there’s the national debt on top of private debt. But the plutocrats say everything is rosy and I suppose it is rosy for them.

TidyPrepster

Home ownership is indeed an issues for younger people, in places like Canada this is mainly due to economic sabotage by places like China, coupled with the insane effects of higher domestic taxation and regulatory burdens on industry. That reality is hardly a recommendation of more socialism, however. Living standards are indeed higher, in comparative terms, due to technological/scientific advancements, but one has to take a broader look at the lives of a workers today and in 1950 in order to see it.

As for the other ills you mention, poor economic choices made by people, even when made en mass, do not evidence the fundamental failure of capitalism. There are many people in my orbit (all under 50) who work for a living and are doing just fine vis-a-vis home ownership, money in the bank, and provisions for retirement. There’s nothing special about them, and they didn’t rob anyone. They’ve just made better choices.

Edit: I often hear the complaints about zero-hour contracts, low savings and absence of “jobs with pensions.” And it strikes me as gripes of the entitled. No one, now or in the past, has ever owed anyone a job with a pension. At one point in time, through a confluence of some factors, those jobs made some economic sense. They don’t any more. (in many cases, we have socialist policies to thank for that, to boot) Complaining that reality is not to your liking does nothing to mitigate the effects of that reality on your life. People who make “better choices” realize the facts on the ground and position themselves the best they can in the economy as it exists, not as they would like to pretend it is.

For a concrete example of this take work-place advancement. Getting in on the ground level and working your way to the top in a single institution hasn’t been the main mode of economic advancement for the majority of workers for the past 25 years at least. Yet I continually encounter younger workers who are shocked by this, for some reason. The key to success in this economy is adaptability and a breadth of experience, no amount of whining will alter the underlying economic conditions that make this so. Adapting to reality is a better strategy for success than adapting (more often pretending to adapt) to a fantasy.

PeterfromOZ

Tables like that are living proof of Dr Johnson’s point that ‘‘comparisons are odious.’’

You make the typical categorical error that lefties make. COmparing the share of income between various groups is utterly and absolutely useless. In fact it is worse than useless, because it says nothong as to whether either group is doing well in absolute terms. Relative comparisons like this are just stupid lefty rubbish, designed to stoke up the biggest problem we have in the world : envy.

This whole argument is beneath you, Ray and you should be ashamed to have even brought it up.

Farris

“Half of American families could not meet a $400 emergency?”

Anyone who has ever worked with the poor knows this is a bogus statistic. Whenever I would meet with some poor individual going through a rough patch causing a financial difficulty he could not afford, I would notice the pack of cigarettes in his pocket, his cell phone on the table while he jingled the car keys and mentioned his cable tv bill. What most of these people mean when they say they cannot afford something is that they cannot afford it without altering their current lifestyle.

You really don’t know anyone under 50 with a pension, IRA, 401K, CD or home equity?

PeterfromOZ

Great to see you put a spear through the heart of the zero sum fallacy that Ray was touting. It seems that even very sensible people can fall prey to the idea that income and wealth are fixed. The point is that the miilionaires created the millions. If the millionaires weren’t there, then the income of the bottom 50% would not increase, but would instead fall, as the top percentile are the ones who create the largest value and money.

CuriousMayhem

It’s hard to know where to start with such nonsense, especially an attempt to revive something so dead, so discredited as central planning. We live in an era of strange, self-referential cults that make me think of a collective social personality as a schizophrenic living in his own mental universe, talking bizarre but unshakable nonsense to himself. The paradigm of this today is the anti-vaccine movement, which seems impermeable to reason.

When the book’s author writes about “financialization,” she (along with everyone else of her ilk) runs together a sloppy and confusing mishmash of developments with historically illiterate name-calling. The confusion of Thatcherism with “neoliberalism” (I think “monetarism” is meant) is obvious. Thatcher wasn’t put in power by financial elites – those elites barely existed at the time and had far less prominence than finance has today. Thatcher was put in power by three landslide elections. When she first won in 1979, Britain was in desperate shape, so bad people alive then (like me) don’t want to think about it.

The proper meaning of financialization is the coming-to-dominance of the financial sector of the economy, which is best served by a financial sector that is subordinate and ancillary: it pools savings, forms capital, then allocates it. It does so in a market system based on private property and price signals. It should serve the so-called real economy.

But in an era of financialization, backed by the overweening power and influence of central banks, doped up on theories and political mandates to engineer prosperity (which they cannot do), finance becomes the thing-in-itself, rather than real economic activity (production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services). People start to think that wealth is money, instead of the power of production to which money simply points. The central bankers become central social planners in all but name, with the goal of inflating asset prices and making it easier and easier for more and more actors to get themselves deeper and deeper into debt.

The best indicator of financialization is the magazine cover. In eras of an advancing real economy, business and economics magazines have “titans of industry” and “geniuses of technology” and “merchants of mass production” on their covers, not bankers or hedge fund managers.

Whence this development? We never hear of the real and informed critiques of neoliberalism and monetarism, which come from the hard-money, free-market right, people like James Grant and David Stockman. A free economy requires sound money and reality-based interest rates and credit standards. The fundamental turning point was the abandonment of the gold standard by the US in 1971. The immediate purpose was to enable much higher levels of money printing to finance America’s growing federal and current account deficits. It lead to the developed world’s highest level of peacetime inflation and the eventual discrediting of Keynesianism, rightly so. Monetarism was supposed to provide the theoretical and policy framework for returning the growth of money and credit in line with the growth of the economy. It did that very well, for a while, as well as provide a decisive refutation of the fallacies of Keynesianism. High interest rates for most of the 1980s kept financialization in check.

The 1990s saw the dawn of a new era, however, one of ever more radical central bank easing, ultralow interest rates, and the collapse of credit standards, embodied in lightly-regulated, poorly understood non-bank lending. It is this era that has given rise to “mass financialization,” with ever larger debt taken on by governments, households, and corporations. The financial system itself, while promising breathtaking rewards for those involved, at the same time becomes more and more interconnected, risk-laden, and unstable. Ultra-easy monetary policy diverts capital away from productive use and encourages malinvestment in speculative manias. The slowing of productive capital growth means slowing productivity and wage growth, stagnant living standards, and everyone – households, governments, and companies – taking on more and more debt to make themselves feel more wealthy than they really are. It only looks like “asset growth” to the financial side; elsewhere in the economy, those assets are canceled by the growth of liabilities. It’s not a “real” productive asset, like a farm, a laboratory, a factory, or a good education.

The solution – and there’s only one path that can successfully get us out of this – is a period of austerity and much higher interest rates, leading to a rebalanced economy with higher savings rates and a better ability to finance its own debt; followed by more productive deployment of capital in higher return ventures, something that will happen naturally with higher interest rates and better credit standards. Higher productivity will lead to higher wages and living standards. Policy today, and since the mid-1990s, has been built around encouraging everyone to squander capital, because it feels good, for a while. It’s no more complicated than that.

Back to retro-Labour: All of this on top of other, extremely ugly aspects of Corbyn and Corbyism: his anti-semitism, his praise for sick, pathological dictators like Maduro and Mugabe, and apparent belief that the wrecks such people have made of their societies make them real utopians. The reality is stark: no decent, rational person would vote for such a man or his party. If he and his party win the next election in Britain, decent and rational Britons need to start making plans to leave. Businesses and international partners will certainly being doing just that, as well as marking the end of Britain’s membership in the EU, far more decisively than Brexit.

ClosedRange

When I read the labour manifesto I felt physically sick in the stomach. It looked like they picked all the most extreme and hateful aspects of their ideology and put them centre stage.

As for the articles claim that we should understand Corbyn’s economics because “He and the people around him have a set of beliefs about the economy that they take very seriously” I say this is a bad reason. Flat earthers take their ideas seriously, and we pay them no attention. Instead, the only reason to understand Corbyn’s economics is to know and understand how much harm it would cause.

Let’s recap who Corbyn is

a communist, despite the fact this ideology likely killed more people last century than any other

a terrorist sympathiser, from the IRA to Hamas to ISIS. Laying wreaths on the graves of the terrorists who attacked the Munich olympics is ok for this guy. Claiming that its wrong that the US should have gone after Abu Bakr Al Bagdadi - despite the man having been at the center of the worst Islamist movement to have happened since Al Shabab.

an anti-Semite through and through, who has overseen the purge of Jews from the Labour party through a campaign of abuse and bullying by his lackeys, who he provides cover for.

Labour is a corrupt, racist and extremist party now. We need only consider their ideas in order to refute them.

ClosedRange Geary_Johansen2020:

The Culture War could best be described as a battle between the Anywheres and Somewheres, with the No Man’s land between the warring factions, the inherent differences of those who were born as Have’s and Have Not’s. Both sides cheat. The Liberal side resort to bribery, and the deliberate co-option of naturally conservative communities. They also promise things they can never deliver, and ignore the hard truths of the real world.

Good comment as always @Geary_Johansen2020 , but I always felt that the anywhere/somewhere explanation for the divide over Brexit was like viewing the light of truth through a prism and seeing only one of the colours. As a person who has lived in 3 countries and who regularly travels abroad for work, I would count myself as an anywhere in all practical ways. Yet many of the reasons for people’s views on the EU are less to do with their own feelings of who they are, and more about the actual workings of the particular EU institutions, it’s future direction, and it’s track record: ongoing eurozone crisis, continuous cash, job and brain drain out of southern europe to the north, inability and unwillingness to enforce its own rules on immigration, U-turns on policy such as the European army. Use of monetary policy as a bullying and coercion tactic against weaker member states. Repeated ignoring of referendums on key treaties. Increasingly hostile outlook towards our major allies in the US. Selective application of the law and biased approach to regulating major international businesses (especially fining Google 5bn for linking the Google store to its search engine, but somehow only fining Volkswagen 1bn for emissions defeat devices fitted to hundreds of thousands of cars…). Then there is the selective application of “harmonisation” rules, which allow Ireland and Luxembourg to be tax havens, yet it’s a big no-no if taxes would be substantially lowered in the UK. The list goes on and I don’t want to just sound like I’m having a rant. My point is that people’s views on these issues are less about how they view themselves, and more about their moral views on how a governmental organisation should behave, and what the actions of the EU tells us about it’s true nature.

Another set of reasons that cut across “cultural” divides will just be that some sectors of the economy benefitted more than others from the EU, and some were downright losers. Fishing is a good case in point, but the EU’s agricultural policy generally is a heavily systemically unfair one. There is a common confusion in Britain right now that most services will lose out from Brexit, but EU common market rules never covered services. Some areas developed their own internationalisation, like intellectual property law, but this is independent. It’s the role of nation states to balance out the benefits of one sector against the losses of another, but I do agree that this has been too one sided for some time now.

The truth is that even for a true anywhere person like me, at some point all these other aspects of the behaviour of the EU become too much. So I think the idea that there’s two cultures is maybe a small part of the explanation of why things went the way they did, but there’s also a point where the actual events, actions, and decisions of the EU are likely more important than any cultural differences among different parts of the British population.

What I have found in my experience of the last few years is that the people who have taken the time to read books (not just the news) that give factual accounts of the last decade do show a bit of Euroscepticism - not always enough to have gone as far as voting for Brexit but generally aware of many of the darker sides of the EU. In my experience, the people who are most absolutist in their pro-EU views are rather uninterested in politics and current affairs, haven’t lived abroad, and tend to know Europe only through short holiday breaks (and consequently imagine it to be all happy clappy). Maybe they read “A year in Provence” once and took it for gospel. For these people, who I would call fake anywheres, I have noticed they tend to define the debate in terms of how they view themselves (“I’m pro EU because I feel European because I like going to Nice and Amsterdam and having Champagne, and I think this makes me a better person”). They find people like me a complete enigma, as they tend to imagine that I ought to be even more pro EU than they are just for having travelled more. They get quite upset when I say I’m not and that having lived in France for a long time is part of the reason. I’m not implying these people are the majority of people who voted remain, but I do think they tend to be the most extreme.

ClosedRange

One thing I want to mention relative to the map you posted is that it gives the impression that the top x% have lives several hundreds of times better than the rest.

More generally, the most common mistake of left wing critiques of wealth distribution is they tend to make the category error of thinking that wealth in a modern industrial capitalist society is the same as wealth in an agricultural society. In an agricultural society, like pre-revolutionary Russia, it is true that the guy in the village with twice as much grain as the rest will survive the winter whilst his neighbours will watch their children starve. In fact, it isn’t just a coincidence that communism has so far only truly taken over in societies that at the time were primarily agricultural (Russia, Vietnam, China, North Korea) or otherwise sustained by a few commodities like oil (eg Venezuela).

By contrast, wealth distribution statistics in a modern capitalist society are hugely disproportionate to real differences in people’s lives. Bill Gates is maybe about several 10000s of times richer than me, but I would estimate that maybe his life is only about 5-10% more fun, enjoyable and so on. Any food he can eat I can eat too, any music he can listen to I can listen to as well. He might get the best healthcare in the world, but he is only likely to get a few more months on average than the rest of us.

The problem is that money is on a heavy slope of diminishing returns. The truth is that once your basic needs are covered (including houses, healthcare and so on), money very quickly has a diminishing impact on quality of life. Some easy examples are that a 10 dollar Casio watch is actually arguably a better watch than a 100,000 dollar Patek Philipe. A Toyota Yaris is arguably a better car for most people than a Lamborghini. Much easier to park and better fuel economy. A 0.50 cent bic pen is just as good as a Mont Blanc fountain pen, and way easier to carry around without scratching it.

Another example is that my house is worth X, but two streets away, my neighbours houses are worth 2 times X. But from all practical points of view my house is arguably nicer, it’s just theirs are 5 mins closer to the train station. I think I’m the winner in this situation, but wealth statistics would have me at a disadvantage.

Another example of how wealth statistics can become practically meaningless: the great recession wiped out about 30% of all asset values, yet the people who lost the most money didn’t experience much change in their day to day life. Most of that “wealth” was just a theoretical estimate on how much cash they could get if they sold all their possessions. Since nobody ever does that except when they die with no heirs, it shows that measuring people’s wealth to produce wealth inequality statistics is not actually representative of reality.

Once we realise wealth statistics are somewhat vacuous, we can try to better understand the big difference between a capitalist society and an agricultural one, and thus understand why the left has misunderstood the situation. In an agricultural society, people make and produce food, and have only limited capacities for bartering. If a guy amasses lots of grain, so much more than all his neighbours, he can’t invest it - there’s not enough worthwhile things to buy with it, so he keeps the grain in his house, and it sits there until he eats it himself. Nobody else gets a share of it.

In a capitalist society, people have nominal wealth attached to their names but in reality that money is elsewhere working for somebody else. In fact, this is the lion’s share of money in the modern world. Indeed,

after buying your house, your food, and paying for your entertainment, healthcare and the rest of your daily needs, all you have left is to save money and invest it - which entails giving it to someone else in the promise of future repayment. This is one of the most important aspects of capitalism, which is in fact a form of mutually beneficial wealth redistribution - I invest in my fellow people’s future because I don’t have a need to convert all of money now into goods or services. I think this mechanism is probably the most misunderstood by the left, that think investors are somewhat parasitic. The most basic example of how this form of capitalism works in a healthy and socially productive way is through the building societies that originated in 18th and 19th century England and Scotland, which were the first mortgage lenders to ordinary folk on modest incomes.

I think I’ve made my point now that money and wealth is actually a poor measure of the differences in the lives of rich and poor. As an alternative, I think people need to look more at real data that captures true differences in peoples lives. I think it is far more relevant to look at discrepancies in peoples experiences, such as how big variance is there between rich and poor. Some examples could include life expectancy, exposure to criminality, violence, divorce, drugs, addictions, and so on. We do know poor people suffer more from these things, but my guess is that the gap between rich and poor in western societies has never been smaller than now. I think these are far more relevant indicators of equal or unequal societies than just theoretical wealth statistics.

0 notes

Text

Shut Up and Make Some Art

By Don Hall

I'm surrounded by artists. I've been in the company of fellow artists of nearly every stripe since I was prepubescent, and the refrain, "I should be paid for this work!" is as common as half-baked songs and poems about romance gone wrong. Combined with the rhetoric of the 99% and the botched lack of oversight of corporations plus the demise of the American union, this demand to be paid a living wage to be an artist sounds silly.

Lose the entitled attitude and become amazing.

Before the days of radio and recorded music and movies, family members were required to learn to play instruments and recite poetry and create art. Both for self-edification as well as entertainment for the family (picture the Norman Rockwell-esque vision of a home piano recital and family sing-a-long). The amateur creation of art and the learning of an artistic skill used to hold a great deal of importance in the average American household. Art was less a commodity to be bought and sold and more a way of life.

Eventually came the idea of the specialist.

Like the difference between the old family doctor and the plastic surgeon, there was more money in specialization. Why be an MD when you could make a lot more money being an eye doctor or dermatologist? Old school (meaning pre-film days) performers could do it all—Charlie Chaplin could sing, play several instruments, dance, act scripts, write scripts, direct and perform sleight of hand as well as show proficiency at acrobatics and sword swallowing. Most vaudevillians could perform on the stage, in the orchestra or backstage—whatever was necessary. That show must go on.

Like with politics a bit later (which wasn't heavily affected by film and television until the 1940s) the movies changed the craft of acting. Early films captured the skills of these renaissance performing Jacks of All Trades—the work of the Marx Brothers, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and, of course, Chaplin were often simply screen versions of the schtick they had performed on stages for years. With later film, however, it became apparent that skill was overshadowed by looks and the vaudevillians of old became cameos in the films of the very good-looking movie stars.

Even then, actors like Cary Grant, Errol Flynn, Fred Astaire, Judy Garland and Fanny Brice could hold their own in nearly any performing medium. There was a well-rounded quality to their skills and, when attached to natural camera friendly charisma, stars were born. But they were born after years of practice on stages.

Jump Cut to today and we have movie stars that can only look pretty on film and go to learn skills and craft on Broadway as gimmicks. The idea of winning that lottery and becoming a star has overtaken all aspects of the industry, and students spend thousands of dollars learning how to speak lines of dialogue from commercials selling bullshit for their On Camera classes, and get meaningless degrees in specializations that are far too common.

Instead of getting your voice attuned, learn to sing brilliantly. Did Leonard Cohen have a conventionally beautiful voice? Not on your life. His voice, however, was amazing, and the fact that you just wrote a song out in the Uber ride home is contrasted by Cohen taking NINE YEARS to write Hallelujah. Be better. Be worthy of money rather than entitled to it.

Imagine how much money a brain surgeon would make if every other medical student became a brain surgeon.

As the open source technology begins to unfold, industries like the publishing giants and the film production houses are fighting desperately against the tide of participatory art. With Kindle and digital books, anyone who can type can publish their work for immediate distribution; with iMovie, any idiot with a digital camera can make a movie and post it on YouTube. The writer doesn't need the publisher anymore; the filmmaker doesn't need the studio any longer. Sure, if you want to make JK Rowling or James Cameron dough you need the publicity and distribution of a major publisher or studio, but if all you're looking to do is get enough notice to fuel the next one, now is the Golden Age.

This isn't new for the actor or musician or poet or storyteller. Artists get paid so little on the middle to the bottom of the pile because any asshole can say he's an artist. A degree means dick unless you're going to go into Arts Administration and, even then, grad school isn't about what you learn but who you impress and befriend. If everyone who felt a need to help his fellow man could simply declare that he was a doctor could be, in fact, a doctor, then being a doctor would have very little employable value.

Why do technicians get paid when actors and playwrights and even directors do not? Because they have a necessary and demonstrable skill that has immediate pragmatic value. Working with technology gives it a whiff of legitimacy and something concrete to produce. Why does a group of actors feel the need to become an NFP corporation? Because it makes the theatre company they started smack of some sort of grownup legitimacy. The degree and NFP 501(c)(3) make the work seem suddenly more adult and business-like. Like charity for themselves. Having a Board of Directors comprised of people with real jobs makes us feel that we are somehow not just defrauding the public by putting on our shows.

The attitude that in order to be a successful artist one must be a savvy businessman is like telling a poet he isn't a real poet until he can sell 50 books of his poetry. The sale doesn't change the work; it just makes the poet spend time selling it rather than making it. And face it, most poets we still read are amateurs that became famous because someone else sold it. Most died broke.

Now, here is where it gets sticky—the NFP institutions are built for distribution. Like publishing houses and film studios, they make their dime on providing a building to do shows in and a place for artists to gather. The artists almost always rotate in and out—the revolving door of the journey. Even an ensemble theater like Steppenwolf rarely has the same actors floating around from show to show. Similar to the publishing house, a good 85 percent of the dough per book sold goes to overhead. In the publishing institution, that means paying publicists and accountants and sales reps and the administrative costs. The guys who print the actual books? Probably not getting a big cut of that $24.95 ($25.95 in Canada). The authors? Not unless they're Dan Brown.

Institutions operate exactly the same way.

You don't need a degree to be an artist.

You don't need an institution with a Board of Directors to make art.

All you need is the desire to be a craftsperson. Learn how sing, dance, orate, write, do magic, direct, hang lights, design and build a set, record some cool SFX, paint. Make it your business to be good at everything. Make art. Make your art. Make it anywhere, any time. Don't listen to those screaming in your face, "Be a professional specialist! Grow up! Be a better corporation! And buy my book that tells you how!"

Here's a reprint of something a very smart fucker once wrote to me. I posted it originally on my old blog in 2005.

Patrick Jacobi was in Postmortem and is one of the smartest people I've known. Moved to Vermont decades ago to study law. He then emailed me. Here's a piece of his correspondence:

"SHUT UP AND WORK. Law school has made me realize what a lazy person I was when I worked a 9–5. If you haven't exhausted yourself by the time you go to bed, you have wasted your day. You want to be an artist and get paid—PROVE THAT YOU CAN GENERATE REVENUE SUFFICIENT TO BENEFIT SOMEONE WHO HAS THE MEANS TO PAY YOU or perish. If I had it to do again, I would have stayed up until 3 or 4 every night writing scripts, getting in shape, sending out headshots, etc. If you are sleeping comfortably when you are trying to make art that someone will pay you to make, you are going about it the wrong way. If law school requires that I work this hard just to become a lame-ass lawyer, then that means becoming an artist requires 10 times as much work.

I have alienated a few with this rant, but I know you well enough that you will heed it or ignore it to your heart's delight. But feel free to pass it on to others: YOU ARE ENTITLED TO NOTHING. WORK UNTIL YOU DROP AND THEN GET UP AND WORK SOME MORE AND THEN MAYBE THE WORLD WILL GIVE YOU A PENNY. When you can truly say that you are blind with the fatigue of trying to make art, then I will feel for the PERSON WHO CHOSE TO BE AN ARTIST, when so many other easier roads were available. IT IS THE HARDEST of roads, so SHUT UP AND MAKE SOME ART!"

There you go.

0 notes