#the transliteration of the word 古典

Video

chinese gudian dance / classical dance by 嘎嘎灵

#china#video#dance#I prefer to call it gudian dance#the transliteration of the word 古典#because it's kind of different from classical#chinese gudian dance is a very generalized concept#with costumes referencing the hanfu style and some referencing the feitian style#often incorporating many movements from martial arts acrobatics and chinese opera#some of the basic movements of large performances are influenced by ballet#I personally prefer choreographies that are not influenced by elements such as ballet but inspired by ancient chinese culture#like 玉人舞 yu-ren-wu and 丽人行 li-ren-xing#this girl's dance is more like the one I'm talking about#very pretty

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (4): the Display of the Mitsu-gusoku [三具足] on the Oshi-ita [押板].

4) With respect to the mitsu-gusoku [三具足]¹ on the oshi-ita [押板], the orthodox way of displaying these things² encompasses multiple layers of ku-den [口傳]³.

_________________________

¹Mitsu-gusoku [三具足].

The set of three, usually bronze, implements that are traditionally arranged before the Buddha image(s) on a family altar*.

As shown above, these consist of a flower vase (left), a censer† (middle), and a candlestick (right). This particular set was made in the 20th century.

___________

*In a temple setting, the number is usually increased to five -- and so referred to as go-gusoku [五具足] -- by adding one more flower-vase and one more candlestick.

†The shape of the censer is determined by the type of incense that will be burned. In modern times, stick incense (which are said to have first appeared during the Ming dynasty) is commonly used, so the censer has a wide mouth (in order to catch the ash as it falls from the burning stick: such censers generally lack a lid); an example of this type of incense burner is shown on the left, below.

Burning incense by placing a piece of fragrant wood on top of a charcoal tadon [炭團] requires a more cup-like shape (middle), and which is only covered when not in use (to keep the ash clean and dry). Crushed incense (which resembles sawdust made from incense wood), which is formed into a cone by pressing a large pinch of incense against the bottom of the vessel, is burned in more constricted censers, usually provided with a slotted lid (the control of the atmosphere within the censer causes the incense to smolder away more slowly), and an example of this kind of censer is shown on the right..

²Hon-shiki no kazari [本式のかざり].

Hon-shiki [本式] means orthodox, formal, proper. The traditional way that these things have been arranged since ancient times.

³Jūjū ku-den ōshi [重〻口傳多し].

Jūjū [重々] means repeatedly, manifoldly, again and again -- in other words “the entire body” of associated ku-den, layer upon layer.

Ku-den [口傳] means orally transmitted [teachings]. These things were never supposed to be written down, but imparted directly by the teacher to his disciple (hence the name).

In this case, however, we must remember that Book Four of the Nampō Roku is essentially a collection of notes that Jōō wrote down while listening to discussions about these things during the Shino family’s kō-kai. The word ku-den, then, was probably interpolated by Jōō (or, possibly by his interlocutors -- it being unclear how deeply apprised these people may have been regarding the innermost teachings) -- because of a lack of a complete understanding of these matters on his part (these notes seem to have been made rather early in Jōō's career, probably many years before he came to be recognized as a meijin [名人]). Information not revealed (for whatever reason) was deemed “secret” -- and the usual way to describe secret information is to call it a ku-den.

The actual, historical, reference seems to be to the relevant body of teachings (such as they are) that were included in Sōami's O-kazari Ki -- which I will attempt to translate (in full) below (along with the brief comments from Shibayama Fugen’s and Tanaka Senshō’s commentaries).

Ōshi [多し] means many; a large number -- though this may have been an exaggeration introduced into the narrative purely for Jōō’s benefit (for whatever reason, the people of the orthodox lineage seem to have been extremely careful to avoid revealing their secrets to this man).

==============================================

◎ The following are the references, which may be associated with the mitsu-gusoku, that are found in the O-kazari Ki. The entry numbers are according to the Gunsho Ruijū [群書類従] version of the O-kazari Ki (which agrees with the text of the manuscript copy that was preserved by the Imai family, from which the several illustrations are taken), as published in the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集]. (The Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu also includes a second version of this document, which corresponds to the early Edo period block-printed edition that was mentioned previously, at the bottom of the post entitled An Introduction to Book 4 of the Nampō Roku: Shoin [書院], Part 2 -- Sōami’s O-kazari Ki [御飾記], and the O-kazari Sho [御飾書]: https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/189154183823/an-introduction-to-book-4-of-the-namp%C5%8D-roku.)

The examples, by the way, provide a fairly representative view of the kind of information that the O-kazari Ki contains. I have quoted the original Japanese text first, and then translated it, while keeping my own comments (which are contained in the footnotes) to a minimum.

43) Mitsu-gusoku no kōgō ni ha, kō wo go-kire bakari iru-beshi. Kaki-kōro* no kō-bako† ni ha mei-kō wo tsutsumi nagara iru-beshi, shiki sadamarazu [三具足之香合には、香を五きれはかり入へし、かき香爐の香はこには名香を包なから可入、敷さたまらす].

The kōgō [placed] with the mitsu-gosoku should contain [only] five pieces‡ of incense; in the kōgō [arranged] with the kiki-kōro**, the mei-kō should be enclosed in a wrapper††, though whether [a piece of paper should also be placed] underneath [the wrapper] has not been fixed‡‡.

__________

*Kaki-kōro [かき香爐]. According to the other versions of the O-kazari Ki and O-kazari Sho, this word should be kiki-kōro [聞き香爐], a censer that is held in the hand while appreciating very special incense wood.

Perhaps this was a miscopying for kika-koro [きか香爐 = 聞 か香爐] -- though it appears consistently throughout this version of the O-kazari Ki, with the apparent meaning of “a hand-held censer used for appreciating incense.”

†Kō-bako [香はこ]. The kōgō [香合]. The kanji for kōgō was pronounced kō-bako during this period -- though I have generally used “kōgō” in the transliterations whenever the pronunciation was not spelled out (as here), to help modern readers avoid confusion.

‡Go-kire [五切れ] means five “slices” -- the original piece of incense wood was sliced into thin, roughly square, pieces, using a special chisel. The result was similar to the way byakudan [白檀] and jin-kō [沈香] are sold nowadays.

**Kiki-kōro [聞香爐], a small, ceramic censer intended to be held in the hands while sniffing the incense being burned in it.

††Mei-kō wo tsutsumi nagara iru-beshi [名香を包なから可入]. Mei-kō [名香] refers to high-quality incense wood (usually kyara [伽羅], which is jin-kō with an extremely high resin content). A kō-zutsumi [香包] is a sort of envelope, traditionally made either of heavy paper, or of paper coated with gold foil on one side and a piece of donsu cloth on the other. As with the chaire, the gold-foil prevented the loss of aromatics while also protected the incense from external smells. Generally two pieces of kyara were placed in each kō-zutsumi, as insurance against the accidental dropping of one of them. (Enclosing more than two pieces was discouraged, so as to prevent the guests from asking for them.)

‡‡The piece of paper was placed between the kō-tsutsumi and the bottom of the kōgō, to prevent the transfer of any aromatics that had infiltrated into the lacquer to the incense. If the mei-kō was in a kō-zutsumi made of gilded paper, then the danger of infiltration was low; however, if it were simply in an envelope made of heavy paper, prudence might dictate that this be, in turn, placed on top of a piece of paper, as added protection.

46) Mitsu-gusoku ni ha, ko-dō ni te, kō-saji no dai bakari chawan-no-mono ni te mo kurushikarazu [三具足は胡銅にて香匙之臺ばかり茶碗の物にてもくるしからず].

When the mitsu-gusoku are made of ko-dō [胡銅]*, only the stand for the kō-saji [and kyōji] should be [placed out together with them]†; however, there is no problem if a chawan [is also included in the arrangement]‡.

__________

*Ko-dō [胡銅] is a variety of bronze that has turned a deep black with age. This type of bronze was produced in both China and in Korea. The kanji ko [胡] means “barbarian,” and so may have referred to an early type of bronze: possibly the earliest varieties of the metal (dating from the bronze age) were imported from the regions to the west of China.

†Kō-saji no dai [香匙之臺] refers to a small, vase-like container, resembling a miniature shaku-tate, in which the kō-saji (a spoon used to handle the incense) and kyōji (a pair of ebony or ivory chopsticks that were also used to handle the incense) were stood. In the present day, a bundle of stick incense is often stood upright in the same sort of vessel, to keep the incense ready for when it is needed (though this practice appears to be a corruption, resulting from ignorance) -- thus the kō-saji no dai is often still present along with the mitsu-gusoku, even though its original purpose has been forgotten.

According to modern usage, the kō-saji was used to transfer the pieces of incense from the jin-bako [沈箱] (a compartmented vessel in which the pieces of incense were collected from the chopping block) into the kōgō, while the kyōji were used to place one piece of incense in the kōro. (The ash was sometimes shaped with a different utensil -- one which resembles a folded fan, and is termed a hai-oshi [灰押]: the hai-oshi should never be identified with the kō-saji, though people connected only with chanoyu are apparently inclined to do so on account of its similarity to the hai-saji [灰匙].)

‡Chawan-no-mono [茶碗の物] is used in the O-kazari Ki to refer to a kenzan-temmoku [建盞天目] resting on a temmoku-dai. This was the chawan used to serve tea to the most exalted guest.

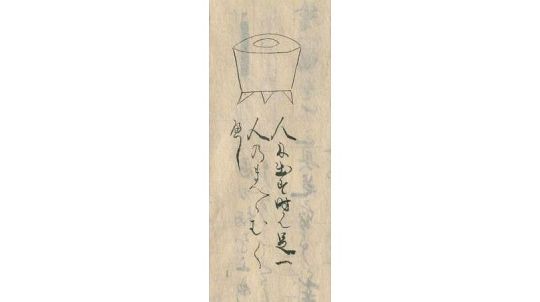

51) Hito no mae [h]e dasu toki, hana-no-moto wo mukawasu-beshi [人之前へ出す時、花の本をむかはすへし].

When placing something* out in front of people, the root of the flower† should be toward them‡.

__________

*In the other versions of the O-kazari Ki and O-kazari Sho, this entry refers explicitly to the kōgō.

†Hana-no-moto [花の本] means “the root (end)” of the flower. In other words, when an object features a picture of a flower and its leaves, the piece should be oriented so that the leaves (and butt-end of the stem) are in the front, with the flowers slightly toward the rear.

‡The two sketches of kōgō show the way the pictures of plants should be oriented.

54) Hito ni dasu-toki ha, ashi hitotsu hito mae [h]e muku-beshi [人に出す時は、足一人のまへゝむくへし].

When [a kōro*] is brought out for people [to inspect on the oshi-ita, or on the chigai-dana], one foot should face toward the front of the person.

__________

*In the other versions, this entry actually begins with the word kōro [香爐]. Even though it has not been included here, the sketch eliminates any ambiguity caused by its absence (since it shows a picture of a kōro).

57) E ippuku kakete, san-gusoku oki koto kurushikarazu-sōrō, san-puku ittsui kakete, mitsu-gusoku nashi ha ryaku-gi nari [繪一幅懸て、三具足置事不苦候、三幅一對かけて、三具足無は略儀なり].

While there is no problem* with placing the mitsu-gusoku [in front of] a single scroll, in the case where three scrolls are displayed at the same time, the absence of the mitsu-gusoku is an informality†.

__________

*Kurushikarazu [不苦 = 苦しからず] means there is nothing wrong with doing something, literally "it is not a hardship to do (such and such)."

In other words, the host could place the mitsu-gusoku in front of a single scroll if he wants to do so. But there is certainly no rule stating that he must do this -- unlike in the case of a triptych (where the mitsu-gusoku should be arranged in front).

†Ryaku-gi nari [何も 略儀 也]. Ryaku-gi [略儀] means informality -- in the sense of taking a liberty, doing something irregular, or contrary to strict propriety. In other words, the mitsu-gusoku should be displayed in front of a triptych. Doing anything else, while not exactly wrong, deviates from the correct form.

62) Mitsu-gusoku ha tada mitsu-gusoku to iu, betsu ni mei nashi [三具足はたゝ三具足と云、別に名なし].

The mitsu-gusoku are simply called “mitsu-gusoku.” There is no other name.

71) Chū-ō-joku ha, mitsu-gusoku no mae ni oku nari [中央卓は、三具足のまへにをく也].

The chū-ō-joku is placed in front of the mitsu-gusoku.

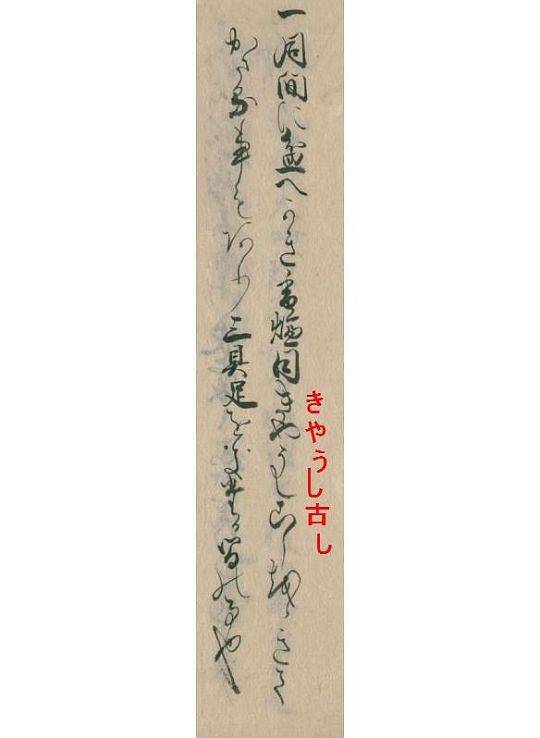

81) Onaji ma ni bon [h]e kaki-kōro, onaji kōji koji wo okite kazaru-koto mo ari, mitsu-gusoku oki-taru aida no koto nari [同間に盆へ聞き香炉、同きやうしこしをゝきてかさる事もあり、三具足をきたる間の事也].

In the same room*, a tray, on which are a kaki-kōro, [a pair of] kyōji† and [a pair of] koji‡, is displayed. This is similar to the placement of the mitsu-gusoku [on the oshi-ita].

__________

*This follows on from entry 80, which describes a (wooden) pillow being arranged in a toko in a bed-chamber (the toko is used as a bed), “according to the (size of the) body (of the person who will sleep there);” or else something like a kara-bako [唐箱] (a “Chinese-box,” perhaps for night-clothes or bedding) could be placed there.

†Kyōji [きやうし = 香筋] are chopsticks made of ebony or ivory, used to handle the pieces of incense wood.

‡Koji [こし = 火筋] are chopsticks made of metal (silver and bronze were the most common), that are used to lift the tadon [炭團] (a small, cylindrical, briquette formed from crushed, high-quality charcoal, that is used to heat the kōro) into the kōro. Sometimes it is also used to shape the ash into a cone around the burning tadon.

While the original text (shown above) clearly has kiyaushi koshi [きやうし古し -- ko 古 is a hentai-gana for the sound ko こ], which would be read kyōji koji, these names seem somewhat out of place in this treatise, since I have not seen them used elsewhere in Sōami's writings (when he writes about the implements used to prepare the censer and transfer the incense, he usually speaks of the kō-saji no dai [香匙の臺], while the sketches include representations of both a kō-saji, and a pair of kyōji, ebony chopsticks used to pick up the pieces of incense wood, standing in the kō-saji no dai)*. The use of these words seems to be closer to the terminology employed by the specialist practitioners of kōdō [香道].

Changes such as this may be the result of editorial interpolations made when Sōami’s text (which has not survived) was hand-copied during the mid-sixteenth century†.

___________

*The editor of the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu edition of the O-kazari Ki / O-kazari Sho attempts to rectify things by seemingly changing the pronunciation of kō-saji [香匙] to kō-bashi [かうばし = こうばし], meaning “incense chopsticks.” But this solution does not really satisfy, since it then appears to ignore the “incense spoon” that kō-saji actually means, and which is clearly represented in the sketches.

Furthermore, “kō-bashi” [香箸] (as a name for what practitioners of kōdō refer to as the kyōji [香筋, or 香箸]) is actually the pronunciation preferred by practitioners of chanoyu (rather than incense) -- the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu’s intended audience -- leading to further doubts about the authenticity of this interpretation.

†The surviving period copies -- such as the one that was preserved in the Imai family -- were made for personal reference (and it is likely that they were all based on a single hand-made copy, rather than the original, since they all seem to agree in these kinds of anachronisms), rather than for the purpose of accurately preserving the original, historical text written by Sōami.

This differs from copies made of Rikyū’s densho, for example, where the intention was clearly to make a facsimile of the original (even insofar as imitating Rikyū’s handwriting).

○ In addition to the above entries, one is supposed to understand the correct arrangement of the mitsu-gusoku (if not the yin-yang reasoning behind the placement of the flower-vase and candlestick) from the following sketch*:

The sketch that is found later in Book Four of the Nampō Roku is similarly informative:

[The writing reads (from right to left): oshi-ita (押板); tori hidari migi ari (鳥左右アリ)†; mitsu-gusoku ・ ku-den ōshi (三具足・口傳多)‡.]

While some of the above entries are, indeed, the kinds of things typically transmitted as “ku-den,” their actual number is not especially large. So, unless large portions of the O-kazari Ki have been lost (which seems unlikely), it is possible that Jōō’s interlocutors exaggerated the number of ku-den in the hopes of mystifying and frustrating their auditor**.

___________

*I have digitally altered this sketch, to remove the scrolls that were hanging in the background, as well as the two stands with large flower-vases that were placed on the left and right sides of the oshi-ita -- since none of these things have any relevance to the way that the objects on the oshi-ita are arranged.

†Tori hidari migi ari [鳥左右アリ]. These candlesticks were originally made in pairs, with one facing right, and the other facing left. In this instance, the one that faces toward the left is the one that should be used.

In the original examples of this type of candlestick, the bird is not straight upright, but inclines in the direction toward which it faces, as can be seen more clearly in the sketch from Book Four of the Nampō Roku. The purpose of this was to throw the candle’s light in that direction, while minimizing any impact from the shadow.

‡Mitsu-gusoku ・ ku-den ōshi [三具足・口傳多]. As in the statement that forms the text of this entry, ku-den ō-shi [口傳多] means “there are many ku-den.”

**What little we know of Jōō‘s interactions with Kitamuki Dōchin (and these are found only in memoranda left by tea people, who would be inclined to represent Jōō’s interactions in the most favorable light) -- that he was always asking questions of Dōchin when the two were discussing chanoyu -- suggests that Jōō was inclined to pester the cognoscenti with questions about the secret details of gokushin-no-chanoyu, perhaps because such men were not inclined to be especially forthcoming (since they would have regarded Jōō as a potential competitor, rather than a disciple, if he were casually initiated into the deeper secrets). It is thus at least possible that some of these people were inclined to frustrate his accumulation of the facts through dissimulation and obfuscation.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

In addition to the things mentioned above (none of which is found in any of the commentaries on the Nampō Roku), the scholarly commentators have limited their own input to a surprising degree:

◎ Shibayama Fugen says only that the table on which the mitsu-gusoku will be displayed should be covered with a piece of kinran or donsu*; though, again, this is really not the kind of thing that was generally reserved for oral transmission from teacher to student -- and is also clear from the sketch that is included in the Nampō Roku, in which an elaborate uchi-shiki is depicted draping the oshi-ita†.

◎ Tanaka Senshō, rather curiously‡, uses most of his commentary to discuss the language of this final statement (jūjū ku-den ōshi [重〻口傳多し]) -- specifically noting that jūjū [重〻] is equivalent to the modern-day expression iro-iro [色々], meaning “various (things).”

And while he muses that there must be many relevant teachings that would qualify as ku-den (he mentions the material quoted by Shibayama Fugen, albeit at greater length than is strictly necessary, since anyone can gather as much during a brief visit to a shop specializing in family altars), he declines to introduce any of them in his commentary.

___________

*The way a Buddhist altar is draped with an uchi-shiki [打敷], altar-cloth. Shibayama bases his comments on one of the secret books that accompany the Nampō Roku (though this material -- contained in two volumes -- was not compiled until the decades that followed Tachibana Jitsuzan’s presentation of the Nampō Roku to the Enkaku-ji).

†Curiously, though, one is not seen in the corresponding sketch that was included in the O-kazari Ki) -- not even in the later version of this work, entitled the Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho, which is roughly contemporaneous with the Enkaku-ji version of the Nampō Roku.

‡The impression one gets it that, since the statement he is discussing indicates that there are a large number of ku-den associated with the display of the mitsu-gusoku on the oshi-ita, he does not want to leave his commentary page blank. Yet, in fact, aside from repeating the same point as Shibayama Fugen, regarding the spreading of an uchi-shiki on the oshi-ita under the mitsu-gusoku, Tanaka really says nothing at all about any secret teachings connected with the display of the mitsu-gusoku -- or anything else, for that matter.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Tempera paintings

下面为大家整理一篇优秀的essay代写范文- The Tempera paintings,供大家参考学习,这篇论文讨论了坦培拉绘画。在西方,真正意义上的现代油画技法产生自文艺复兴时期,在16世纪以后逐步发展成熟,至今不过五百年的历史。而在此之前,经过漫长的历史发展,湿壁画、干壁画、坦培拉绘画以及坦培拉与油画混合技法,都占据了很长阶段的历史舞台。坦培拉,作为一种古典油画技法,其英文名为“Tempera”,源于古意大利语,意为“调和”、“搅拌”。后来泛指一切由水溶性、胶性颜料及结合剂组成的绘画。在如今,现代画家并非只使用传统的鸡蛋乳液,亦可加入酪素乳液、甲基纤维素乳液做为媒介。

In the west, modern oil painting techniques in the true sense came into being during the Renaissance and gradually matured after the 16th century, with a history of only 500 years. Before that, after a long history of development, fresco, dry fresco, tempera painting and tempera and oil painting mixed techniques, have occupied a long stage of the historical stage. Tempera, a classical oil painting technique, is known in English as the Tempera, an ancient Italian word meaning to "blend" or "stir." Later, it refers to all paintings composed of water-soluble, gelatinous pigments and binders. In China, it is often translated as dampera, eggpera and tempera. Nowadays, modern painters do not only use traditional egg emulsion, but also can add casein emulsion and methyl cellulose emulsion as the media, so I think transliteration is more appropriate.

Of traditional opera painting techniques originally from one thousand years ago in ancient Greece, in around the 13th century in Italy, and in the 14 and 15 centuries developed a technique combined with oil mixed, and the hybrid techniques than water temple opera in the painting on the procedures and methods more flexible, can draw on the traditional wood, also can create cloth opera, because of the media agent containing oil and resin composition, enhances the object space form of realism, this technique commonly known as classical multilayer transparent painting. In the 17th century, artist Rubens will titian painted directly with 15 th-century jan van eck hybrid techniques combined strengths, and developed the high liquidity and shape of resin oil paint, gradually replaced the past of oil, water paint, he was in to Spain to own villas, Flemish techniques to the painter, also affects the contemporaneous Rembrandt and 18th and 19th centuries Jacques Louis, Angle, famous master, dost thou since then, oily vera's gradually evolved into pure oil painting, also is our today's direct representations. Thus it can be seen that although the methods of traditional tempera and modern oil painting are different, they are in the same line, and we can add development and innovation.

Classical tempera method, according to a certain proportion of chalk powder, rabbit glue, to make the bottom of the tempera coating, in the smooth and delicate board layer by layer coating brush, and then polished, make the tempera drawing board smooth, can absorb. The papers are a bit similar to the traditional Chinese claborate-style painting method, in order to avoid the dirty vera's sketchpad, realize transparent painting, generally do not take direct paint: the author on the paper first, draw a relatively complete sketch line art depicting characters in this step, the line of things should be accurate in place, as a complete line of draft, avoid further transfer to modify, again will complete by the handmade rubbing to vera's sketchpad above, can use Chinese ink, Ye Jin pen draws the outline of contour line, then draw the gray shades as monochromatic sketches, the structure of the manuscript, projection is accurate, formal coloring for the next step.

Before for classical translucent color, brush with wool to tan vera's sketchpad to uniform besmear again water, thin and uniform, then according to depict objects with egg liquid, toner modulation type, dip in with thin cancel the pen color, still modeled on monochrome sketch method of line, color shape, step by step to make the color relations, complete the translucent painting, this is the traditional opera painting method.

In the middle ages, tempera painting technique was the main way of depicting holy portraits and frescoes, but it gradually declined after the Renaissance. In the continuous development, tempera paintings can be mixed with water or oil, which can be divided into two categories: water-based materials and oil-based materials. The painter can freely distribute the proportion. If there is much water, the strokes will be smooth and the color is transparent, which is convenient for painting details. If oil is more than color saturation, and suitable for long-term preservation, easy to depict large ICONS, murals. The materials and methods used are different from other paintings, so the preservation time is much longer than other painting materials, the unique emulsion film will not change with time yellow, dark, the overall color saturation and moist, can not be aging for thousands of years.

Due to the ancient western tempera paintings mostly serve for religion, creating a large number of images of the virgin, often using gold and silver foil in the painting process, such a single and rigid theme, high cost, gradually covered by modern techniques. Only constant development have a new progress, recently, the temple to pella this ancient painting and painters, klimt Austrian artists in the 19th century to the traditional temple pella painting techniques to innovation, add gold foil in modern painting subjects, create a colorful and have strong artistic adornment effect, make you occupy a unique position in the history of art.

Compared with other painting forms, tempera painting has the characteristics of rapid drying and conjunctiva, and the paint is usually dried out at the very moment of painting, which greatly saves the painter's creation time, improves the convenience, and can be repeatedly painted in a short time, and the picture effect is bright and transparent. This characteristic is well suited to precision painting, where the most original and fascinating lines are kept in the frame without having to wait too long or worry about getting dirty, and modern paintings that require a lot of repetition are also dependent on tempera's technique.

At the same time, because tempera USES emulsion and pigment toner to harmonize, its colors map to each other, the luster is soft, make the picture does not have a strong impact, give the viewer a kind of cordial, natural feeling, in line with the visual aesthetic interest. Some of the transparent luster of tamperat also makes it unique in oil painting and watercolor pigments. The painter does not need to worry about the repeated strokes to make the color become turdiness and precipitation, and the picture becomes dark. On the contrary, the more transparent painting layers, the softer and more accessible the work. Like painting the save the life of around five hundred, if techniques, pigment is not suitable but also can shorten life span, can only stay in two hundred and thirty, even change color, fall off in a few years, beautiful works can't keep it is a shame, but Tanzania vera's work can be painted hundreds of years, is advantageous to the long-term preservation of collectors, and this is vera's painting unique charm.

Andrew wise, one of the great American painters of the 20th century, was a keen user of the tempera technique. His realism in painting style, the pursuit of modernism, works were used in the egg color, watercolor medium for artistic creation, such as all kinds of materials use vera's techniques for large size drawing, with egg white, powder mixed with glue, the method of using jotham pella painting layer mask to dye, tend to be painted in a month, Andrew wyeth's depiction of the characters and scenery, from his home state of Pennsylvania Richards's town, and Cushing, Maine town, such as Andrew said: "I like to slowly draw in the studio, I think the more so the more close to the essence of painting... If a tempera succeeds, it produces a sense of strength and firmness that nothing else can match, and a quality I like that belongs only to tempera's metaphor. Through this ancient traditional techniques and materials, combined with modern painting species and material techniques, wise created realistic artistic works, reflecting the pursuit of modernist emotion.

Nowadays, many modern painters are still attached to the creation charm of tamperat. In such an era of industrial information, the pursuit of speed makes artists no longer blindly choose traditional methods. The addition of modern painting language helps tempera's artistic expression techniques develop into diversification. Artists in the process of painting can be more increase the use of flat pen, YuanTouBi, don't blindly following classical opera painting method row line slowly, but according to depict objects texture, the be fond of painting is to use flexibly, it enriches the temple pella painting materials and techniques, expand the performance of traditional painting space, on the basis of inheriting the traditional painting, make the work of the new era have contemporary feeling.

In China, some painters try to combine tempera and oil painting techniques between material language, modeling language and color language to form innovative "modern tempera painting". Perhaps at present, tempera art is not suitable for short-term sketching, but is very suitable for the expression of subjective will. Professor cao jigang of the central academy of fine arts, who has deep research on this aspect, chose tempera as the material of classical oil painting to reflect his feelings on Oriental connotation. He blurred the landscape in his eyes with ink painting on the cloth surface, which looked and felt like an ink painting. The transparent traces on the drawing board were like the traces left by ink infiltration and halo. A large number of ink traces flowed down, leaving only a kind of residual image, but it could reflect the magnificent momentum of Chinese landscape painting. Cao jigang not only retained tempera's quiet, introversion and delicate shape, but also kept the visual and tactile effect from floating on the surface. He let the fresh immersion of the pigment into the picture, expressing the quality of his aesthetic spirit of ancient China. No matter what kind of painting a painter chooses, he or she should attach his or her own creative intention to the materials under his or her hands, so that viewers can appreciate the artist's spiritual outlook and aesthetic interest. Painter of the new era, the mood for classical has had the very big change, like the past of that kind of harmonious relationship between human and nature was gone, but the artistic creation continues, in vera's study should be followed in the traditional technique, from compliance to development, from development to the innovation, new classical language structure, in the modern reflect her complete artistic feelings, in the world of today's industrialization, materialized to generate new relationships.

想要了解更多英国留学资讯或者需要英国代写,请关注51Due英国论文代写平台,51Due是一家专业的论文代写机构,专业辅导海外留学生的英文论文写作,主要业务有essay代写、paper代写、assignment代写。在这里,51Due致力于为留学生朋友提供高效优质的留学教育辅导服务,为广大留学生提升写作水平,帮助他��达成学业目标。���果您有essay代写需求,可以咨询我们的客服QQ:800020041。

51Due网站原创范文除特殊说明外一切图文著作权归51Due所有;未经51Due官方授权谢绝任何用途转载或刊发于媒体。如发生侵犯著作权现象,51Due保留一切法律追诉权。

0 notes