#then my grandmother said 'let's use the leftovers to put in the toilet because it's waterproof and the floor gets cold'

Text

I mean to be fair I’m aware of how much of a nightmare carpet in a bathroom would be. like carpet with a waterproof layer does exist (and after fifty years it degrades horribly and oh my god don’t inhale that stuff) but the carpet itself would be nasty. which adds to the allure I guess! but dear god I’m not as much of an idiot to put carpet around the toilet

#so the reason I know kitchen/bathroom carpet lining degrades horribly is because the old hallway carpet was. that#and when we took it up it left horrid green stuff. and we ended up inhaling it and it made us sick#it was. nasty#anyway we figured out that was the waterproof lining.#then my grandmother said 'let's use the leftovers to put in the toilet because it's waterproof and the floor gets cold'#not only is that fucking disgusting because there is more often than not a bit of piss residue on the floor.#but the waterproof layer wasn't even there anymore! it was the nastiest grit at that point! not to mention the carpet was basically shot#to shit because it was installed no later than 1973

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grow Up Fast-Fred Weasley x Reader (Part 2)

(GIF credit to @everygif)

Part 1

Masterlist

Prompt List

‘OMG! I loved Grow Up Fast-Fred Weasley x Reader! I’ll love to see a part two where they go get the baby back! Hopefully if you have time, it was so cute‘

‘Grow Up Fast was so cute and amazing!! Part 2???‘

‘loved you’re recent Fred piece on the baby! just wondering if you could do another one along those lines but the reader is pregnant with twins and the whole family is finding it special obviously because Fred’s a twin, just something along those lines 💖‘

Characters: Fred Weasley x Reader, George Weasley x Reader (brother-in-law), Weasley family x Reader (in-laws)

Meanings: (Y/N)=Your name

Warnings: Adoption, pregnancy symptoms/pregnancy talk (throwing up/check ups/scans/trimesters), lots and lots and lots of fluff

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*

“Are we really doing this?” I excitedly breathed out, squeezing Fred’s hand.

He slightly nodded, looking apprehensive himself.“We really are.”

We were stood inside the orphanage, and this wasn’t our first time here. Ever since the baby had left our short care, something had felt off in our lives. In the beginning, we blamed it on the shock of it all; it’s not everyday that you find an abandoned baby behind your shop. Even George pointed this out, saying that our minds seemed to be elsewhere. So here we stood, waiting for the care worker to come back down the hall, but this time she wouldn’t be by herself.

I held back an excited giggle when she turned around the corner with the baby in a carrier. He was awake, kicking his legs about under his blanket, gurgling away as if he knew he was going to his forever home. I tried not to start crying, even though my emotions were all over the place, but it seemed that Fred was happy to let the tears fall. Smiling up at him, I quickly made him face me, giggling as I wiped away his tears. We didn’t exchange any words, but he nodded his at me as if I had asked if he was alright.

“Here he is, little Tommy.” the woman beamed, handing him over to us.

Fred held the carrier in both arms, and we cooed at Tommy. We had helped pick out a name for him when they couldn’t find any recent hospital records, they had no idea where he came from or who his mother was. And just like that, we were taking him home with us.

Once home, we found ourselves lying on the bed, with Tommy in the middle (just like we had the first time we brought him home), and just staring. We had fed him before, meaning he was now sleepy, slowly dozing off.

“What do we do know?” Fred whispered.

“I don’t know.” I honestly answered.“It feels so strange to have him home again, even after seeing him in the care home for so many months.”

“I wish we were there to see him properly grow, he’s so much bigger now.”

“Well he’s here now. And it’s almost his first birthday, we should start planning.”

Fred chuckled, eyes widening when Tommy stirred. Tommy opened his eyes, face scrunching up to cry when I pulled him closer, holding onto him. He calmed down, a few whimpers escaping him before he nodded off again. I glanced at Fred, who was already looking at me, sharing a smile. This was our life now.

A few more months passed, filled with getting used to being parents; the late nights, early mornings, dealing with the ear piercing cries and smelly nappies, but also the bursts of giggles, funny noises and cuddles. So many of our friends and family had come forward to help, giving advice and wanting to get to know the new member of the family. Molly had been extremely enthusiastic after finding out we planned to adopt Tommy. She had worried that there had been problems with us, that we weren’t able to have babies of our own, though even after reassurance, she was still excited. And she offered to babysit way too much (though sometimes that was used to our advantage).

Now it was the day of Tommy’s first birthday. Since there were no hospital records to show his birth date, they had to give it their best guess. Nevertheless, Tommy was going to have a proper birthday. We had decorated the home, our presents were stacked next to the fireplace, the cake was displayed alongside the rest of the food, and I had picked out his outfit for the day, now all that was left to do was wait for the guests.

“Wow, look at my handsome boys!” I exclaimed when I entered the living room, seeing Fred holding up Tommy to look at himself in the mirror.

Fred gasped, turning around so that they were looking at me.“Tommy, look at mummy! Good thing she put in an effort too.”

I scoffed a laugh.“Is everything ready?”

“Yep. Guests should be arriving any minute.”

“Today is all about you Tommy.” I tickled his stomach, laughing with him as he squealed.

The party went amazingly. My family and Fred’s turned up at the same time, all loudly entering our home, gifts in hands, talking over one another. It was hard to take it all in, trying to answer all their questions as they passed me their coats and took off their shoes. Although all their excitement got the best of them, instantly going to greet Tommy and Fred, I didn’t mind, relishing the sight of our entire family together; it was the simple things in life that you could miss, and this was one of them. The day was filled with laughs, too much food and bad singing. There were also nudges towards Ron and Hermione, as well as Harry and Ginny about children, and poor George was being told to keep his search going for the right girl. Both grandmother’s wanted time with Tommy, but I knew he was going to become annoyed being passed around too much. Everyone was content watching him sit up by himself, cushions surrounding him in case he fell, playing with his toys.

Sitting back with Hermione, I found it hard to concentrate on her words. I suddenly felt tired, and also didn’t want to even think about the lunch I had served up. Trying to keep up with the conversation, I sipped at my water, feeling ill. Perhaps I was over tired from the late nights with Harry, we hadn’t had a gathering like this in a while, it was a lot to keep up with, especially when you were one of the hosts. I excused myself, quickly walking to the bathroom. Just as I was about to splash some water on my face, a horrible feeling rose in my throat, and I found myself bent over the toilet being sick. No, surely not, I couldn’t be could I?

Luckily I wasn’t throwing up for long, taking a moment to catch my breath, causing me to cough. Slowly standing, not feeling dizzy now, and quickly brushing my teeth as I flushed the toilet. Checking my reflection, I sighed when I saw how pale I had become. People would definitely notice, if not, then Fred certainly would. I had to act normal, be as bright and bubbly as I was ten minutes ago.

Upon my return, there was music playing, Ginny and Hermione swaying with Tommy on the floor whilst our parents conversed, and the lads talked about something unrelated to babies, families or weddings. Passing by them, I smiled, needing a glass of water. I realised Fred had followed me into the kitchen, sighing as I realised I would have to tell him.

“(Y/N), you don’t look well, are you OK?” Fred asked closely, his hands rubbing my arms up and down as he stood behind me.

I nodded after taking a sip of water.“Yeah. I’m fine now.”

“What does that mean?”

I turned around to face him, leaning back against the counter.“I um...I was just sick in the toilet.”

“Should we take you to a doctor? Do you need healing? What are your symptoms?” he rushed.

“No, I’m fine really. Perhaps I ate something bad....or....”

“Or what?”

“Fred, your mum babysat for us a couple of weeks ago.”

“What does that have to do with any of this?”

“We were alone, all day and all night...can you connect the dots?”

It took him a few more seconds before it clicked, and as his eyes widened, I had to clamp a hand over his mouth to stop him from yelling.

“Yes, Fred, I might be pregnant.” I whispered.

“Uh, am I interrupting something here?” Ron said from the doorway, confused when he saw the position we were in.

“Uh, y-yes! Fred was about to yell about the cake, but...but we didn’t want Harry to hear and get too excited.”

Ron furrowed his eyebrows at us as he slowly stepped back.“OK. I mean, he’s only one, I’m sure he wouldn’t have realised.”

Removing my hand from Fred’s mouth, I let out a sigh of relief.“Look, we don’t know if that’s true yet, so for now, don’t even think about it.”

“But, if you are...” Fred trailed off, smiling to himself.

“Would...would you be alright with that?”

“Would you?”

We hadn’t come back to that conversation, instead trying to focus on the rest of the party. Because Tommy was easily tired out, they didn’t stay for much longer. At any other time, I would insist they stay, even after putting Tommy to bed. However, I wasn’t being a good host as I let them put on their shoes and coats, each waving goodbye to little Tommy. With the door closed, and just the three of us leftover, Fred and I flopped onto the sofa, letting Tommy roam and tire himself out.

“I’ll book an appointment for this week.” I mumbled, trying to not let my eyes droop.

“Do you want me to come with you?” Fred said.

“I...I don’t know. It would be nice but George might get suspicious.”

“Would it be so bad if he found out? You know he would keep it a secret.”

“That’s true. Alright, come with me. Let’s find out together.”

And that’s what happened. Unfortunately it was almost another two weeks before I was able to be checked over; there had been a strange atmosphere as we waited, that’s all we were concentrating on. Tommy still received as much love as he usually did, but there were times where I would stress about the future. Tommy was just one, and if I was pregnant, there wasn’t going to be a big age gap between the children. That would be hard. They would be toddlers together, there would be screaming, crying, toilet training, the money for nappies, clothes, toys....but every time I found myself down that hole, Fred was there to pull me out, consoling me, assuring me we would be alright with one more child.

I had been bouncing Tommy on my lap as we waited for the doctor to see us. Fred had to take him away from me, worried that I would cause him to be sick, but it was a nervous tick. I was extremely grateful to have Fred with me, concentrating on his thumb running over the back of my hand, and the gentle kisses he would place on my forehead. But the appointment went by in a flash, and as we walked outside, I couldn’t help but squeal in excitement and shock, exclaiming loudly to everyone around me;

“WE’RE PREGNANT!”

George obviously had to know first, seeing as we took the day off work. But he was sworn to secrecy. We wanted to keep it under wraps for a while, waiting to see what my first trimester was like. The excitement was almost too much for me, I couldn’t stop picturing what it was going to be like for Tommy to have a sibling. Another person to add to our family, someone else to give our love to. Things were going well, of course there were the horrible symptoms, though I said to myself over and over again that this would be worth. The weeks whizzed by, and soon, I was starting to show, meaning Fred and I couldn’t stop rubbing the tiny bump. I had bawled when Tommy rested his head on it one night, as if he understood his brother or sister was in there.

We knew it would be impossible to keep it hidden anymore, and I seemed very healthy so far. We were also bursting to tell our friends and family, trying to think of ways to announce it. Fred suggested huge fireworks that wrote it out, but I knew that would be too much. Instead, he settled for a cake where the icing would start writing out the message ‘We’re Pregnant!’ when the candles were lit. Once again, the family found themselves squashed together, this time meeting at the Burrow. Tommy stood on Harry’s lap, clumsily using his face to balance himself as Fred and I caught everyone’s attention.

“We thought we would bring you all something special, a thank you for supporting us through the entire adoption process and for helping us get used to being parents.” I explained, pushing the cake into the centre of the table.

The candles had just been lit, and as everyone licked their lips at the sight of it, they realised what was happening. Screams, hollers and cheers erupted throughout the small room, causing me to burst into tears at the happiness. This was good, this was going to be an amazing chapter of my life.

My mother and molly would send me pregnancy books, recipes for meals that were good for the baby, or just natter on and on about advice, side effects, and what childbirth actually entailed. Sometimes it was a bit too much, I would wish they held some details back. The checkups were going well, Tommy’s behaviour was getting better as he grew, also Fred’s enthusiasm seemed to never die down. However, it had come to that certain appointment, the one some couples longed for. It was time to find out the gender of our child. The results we were given weren’t what we were expecting.

Stepping into the shop, I relaxed when I saw it wasn’t too busy. Fred was desperate to tell his brother the news. As he went to get him, I laughed at Tommy’s wide eyes, taking in all the colours and noises. Fred gestured for me to follow him into the stock room, getting their workers to take over the floor. As I stepped in, flashbacks to Tommy as a newborn came to me. How strange, it was almost like a full circle.

“So, what’s it gonna be then?” George grinned.

I giggled at Fred who was almost jumping up and down in excitement.“Go on then, I said you could tell him.”

“Well, Georgie, it’s a boy-”

He threw his arms up in the air.“Yes! I knew it!”

“And a girl.”

“Wait, what?” his arms slowly sank down.

“We’re having twins! There’s going to be another set of Weasley twins!”

George responded with a loud cheer, throwing himself onto his brother in an engulfing hug. They were patting each other on the back, at first jumping about before they calmed down, swaying side to side.

“Freddie, that’s amazing! (Y/N), you’re going to be massive!”

I scoffed a laugh, knowing he meant no harm.“Thank you very much George. You’ve already earned yourself a whole weekend of babysitting.”

“Have you told mum yet?”

“No,” Fred said,“you’re the first.”

“She’s going to go crazy.”

“So is mine.” I stated.

“Who would have thought, eh? Another set of twins?”

“I’m going to finally know what it was like to raise you two. Perhaps I should have a masterclass from your mum.”

“She’ll give you lots of tips, and stories about how much of a terror we were.”

“Great, looking forward to that.”

Leaving the shop, Fred took over carrying Tommy in one arm, his other hand holding mine. We dawdled on our way home, seeming to be in no rush as we took in what news we were given today.

I smiled as I placed a hand on my bump.“Fred?”

“Hm?” Tommy was already falling asleep on his shoulder.

“Are we really doing this?”

He smiled back.“We really are.”

#fred weasley#fred weasley imagine#fred weasley imagines#fred weasley one shot#fred weasley x reader#harry potter#harry potter imagine#harry potter imagines#harry potter one shot#harry potter x reader

273 notes

·

View notes

Photo

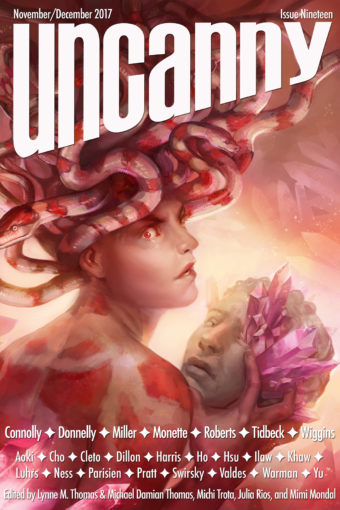

The First Witch of Damansara

BY

ZEN CHO

Vivian’s late grandmother was a witch—which is just a way of saying she was a woman of unusual insight. Vivian, in contrast, had a mind like a hi-tech blender. She was sharp and purposeful, but she did not understand magic.

This used to be a problem. Magic ran in the family. Even her mother’s second cousin, who was adopted, did small spells on the side. She sold these from a stall in Kota Bharu. Her main wares were various types of fruit fried in batter, but if you bought five pisang or cempedak goreng, she threw in a jampi for free.

These embarrassing relatives became less of a problem after Vivian left Malaysia. In the modern Western country where she lived, the public toilets were clean, the newspapers were allowed to be as rude to the government as they liked, and nobody believed in magic except people in whom nobody believed. Even with a cooking appliance mind, Vivian understood that magic requires belief to thrive.

She called home rarely, and visited even less often. She was twenty-eight, engaged to a rational man, and employed as an accountant.

Vivian’s Nai Nai would have said that she was attempting to deploy enchantments of her own—the fiancé, the ordinary hobbies, and the sensible office job were so many sigils to ward off chaos. It was not an ineffective magic. It worked—for a while.

There was just one moment, after she heard the news, when Vivian experienced a surge of unfilial exasperation.

“They could have call me on Skype,” she said. “Call my handphone some more! What a waste of money.”

“What’s wrong?” said the fiancé. He plays the prince in this story: beautiful, supportive, and cast in an appropriately self-effacing role—just off-screen, on a white horse.

“My grandmother’s passed away,” said Vivian. “I’m supposed to go back.”

Vivian was not a woman to hold a grudge. When she turned up at KLIA in harem trousers and a tank top it was not through malice aforethought, but because she had simply forgotten.

Her parents embraced her with sportsmanlike enthusiasm, but when this was done her mother pulled back and plucked at her tank top.

“Girl, what’s this? You know Nai Nai won’t like it.”

Nai Nai had lived by a code of rigorous propriety. She had disapproved of wearing black or navy blue at Chinese New Year, of white at weddings, and of spaghetti straps at all times. When they went out for dinner, even at the local restaurant where they sat outdoors and were accosted by stray cats requesting snacks, her grandchildren were required to change out of their ratty pasar malam T-shirts and faded shorts. She drew a delicate but significant distinction between flip-flops and sandals, singlets and strapless tops, soft cotton shorts and denim.

“Can see your bra,” whispered Ma. “It’s not so nice.”

“That kind of pants,” her dad said dubiously. “Don’t know what Nai Nai will think of it.”

“Nai Nai won’t see them what,” said Vivian, but this offended her parents. They sat in mutinous silence throughout the drive home.

Their terrace house was swarming with pregnant cats and black dogs.

“Only six dogs,” said Vivian’s mother when Vivian pointed this out. “Because got five cats. Your sister thought it’s a good idea to have more dogs than cats.”

“But why do we have so many cats?” said Vivian. “I thought you don’t like to have animals in the house.”

“Nai Nai collected the cats,” said Vivian’s sister. “She started before she passed away. Pregnant cats only.”

“Wei Yi,” said Vivian. “How are you?”

“I’m OK. Vivian,” said Wei Yi. Her eyes glittered.

She’d stopped calling Vivian jie jie some time after Vivian left home. Vivian minded this less than the way she said “Vivian” as though it were a bad word.

But after all, Vivian reminded herself, Wei Yi was seventeen. She was practically legally required to be an arsehole.

“Why did Nai Nai want the pregnant cats?” Vivian tried to make her voice pleasant.

“Hai, don’t need to talk so much,” said their mother hastily. “Lin—Vivian so tired. Vivian, you go and change first, then we go for dinner. Papa will start complaining soon if not.”

It was during an outing to a prayer goods store, while Vivian’s mother was busy buying joss sticks, that her mother’s friend turned to Vivian and said, “So a lot of things to do in your house now ah?”

Vivian was shy to say she knew nothing about what preparations were afoot. As her mother’s eldest it would only have been right for her to have been her mother’s first support in sorting out the funeral arrangements.

“No, we are having a very simple funeral,” said Vivian. “Nai Nai didn’t believe in religion so much.”

This was not a lie. The brutal fact was that Nai Nai had been an atheist with animist leanings, in common with most witches. Vivian’s parents preferred not to let this be known, less out of a concern that Nai Nai would be outed as a witch, than because of the stale leftover fear that she would be considered a Communist.

“But what about the dog cat all that?” said Auntie Wendy. “Did it work? Did your sister manage to keep her in the coffin?”

Vivian’s mind whirred to a stop. Then it started up again, buzzing louder than ever.

Ma was righteously indignant when Vivian reproached her.

“You live so long overseas, why you need to know?” said Ma. “Don’t worry. Yi Yi is handling it. Probably Nai Nai was not serious anyway.”

“Not serious about what?”

“Hai, these old people have their ideas,” said Ma. “Nai Nai live in KL so long, she still want to go home. Not that I don’t want to please her. If it was anything else… but even if she doesn’t have pride for herself, I have pride for her!”

“Nai Nai wanted to be buried in China?” said Vivian, puzzled.

“China what China! Your Nai Nai is from Penang lah,” said Ma. “Your Yeh Yeh is also buried in Bukit Tambun there. But the way he treat Mother, I don’t think they should be buried together.”

Vivian began to understand. “But Ma, if she said she wanted to be with him—”

“It’s not what she wants! It’s just her idea of propriety,” said Ma. “She thinks woman must always stay by the husband no matter what. I don’t believe that! Nai Nai will be buried here and when her children and grandchildren pass on we will be buried with her. It’s more comfortable for her, right? To have her loved ones around her?”

“But if Nai Nai didn’t think so?”

Ma’s painted eyebrows drew together.

“Nai Nai is a very stubborn woman,” she said.

Wei Yi was being especially teenaged that week. She went around with lightning frizzing her hair and stormclouds rumbling about her ears. Her clothes stood away from her body, stiff with electricity. The cats hissed and the dogs whined when she passed.

When she saw the paper offerings their mother had bought for Nai Nai, she threw a massive tantrum.

“What’s this?” she said, picking up a paper polo shirt. “Where got Nai Nai wear this kind of thing?”

Ma looked embarrassed.

“The shop only had that,” she said. “Don’t be angry, girl. I bought some bag and shoe also. But you know Nai Nai was never the dressy kind.”

“That’s because she like to keep all her nice clothes,” said Wei Yi. She cast a look of burning contempt at the paper handbag, printed in heedless disregard of intellectual property rights with the Gucci logo. “Looks like the pasar malam bag. And this slippers is like old man slippers. Nai Nai could put two of her feet in one slipper!”

“Like that she’s less likely to hop away,” Ma said thoughtlessly.

“Is that what you call respecting your mother-in-law?” shouted Wei Yi. “Hah, you wait until it’s your turn! I’ll know how to treat you then.”

“Wei Yi, how can you talk to Ma like that?” said Vivian.

“You shut up your face!” Wei Yi snapped. She flounced out of the room.

“She never even see the house yet,” sighed Ma. She had bought an elaborate palace fashioned out of gilt-edged pink paper, with embellished roofs and shuttered windows, and two dolls dressed in Tang dynasty attire prancing on a balcony. “Got two servants some more.”

“She shouldn’t talk to you like that,” said Vivian.

She hadn’t noticed any change in Ma’s appearance before, but now the soft wrinkly skin under her chin and the pale brown spots on her arms reminded Vivian that she was getting old. Old people should be cared for.

She touched her mother on the arm. “I’ll go scold her. Never mind, Ma. Girls this age are always one kind.”

Ma smiled at Vivian.

“You were OK,” she said. She tucked a lock of Vivian’s hair behind her ear.

Old people should be grateful for affection. The sudden disturbing thought occurred to Vivian that no one had liked Nai Nai very much because she’d never submitted to being looked after.

Wei Yi was trying to free the dogs. She stood by the gate, holding it open and gesturing with one hand at the great outdoors.

“Go! Blackie, Guinness, Ah Hei, Si Hitam, Jackie, Bobby! Go, go!”

The dogs didn’t seem that interested in the great outdoors. Ah Hei took a couple of tentative steps towards the gate, looked back at Wei Yi, changed her mind and sat down again.

“Jackie and Bobby?” said Vivian.

Wei Yi shot her a glare. “I ran out of ideas.” The so what? was unspoken, but it didn’t need to be said.

“Why these stupid dogs don’t want to go,” Wei Yi muttered. “When you open the gate to drive in or out, they go running everywhere. When you want them to chau, they don’t want.”

“They can tell you won’t let them back in again,” said Vivian.

She remembered when Wei Yi had been cute—as a little girl, with those pure single-lidded eyes and the doll-like lacquered bowl of hair. When had she turned into this creature? Hair at sevens and eights, the uneven fringe falling into malevolent eyes. Inappropriately tight Bermuda shorts worn below an unflatteringly loose plaid shirt.

At seven Wei Yi had been a being perfect in herself. At seventeen there was nothing that wasn’t wrong about the way she moved in the world.

Vivian had been planning to tell her sister off, but the memory of that lovely child softened her voice. “Why you don’t want the dogs anymore?”

“I want Nai Nai to win.” Wei Yi slammed the gate shut.

“What, by having nice clothes when she’s passed away?” said Vivian. “Winning or losing, doesn’t matter for Nai Nai anymore. What does it matter if she wears a polo shirt in the afterlife?”

Wei Yi’s face crumpled. She clutched her fists in agony. The words broke from her in a roar.

“You’re so stupid! You don’t know anything!” She kicked the gate to relieve her feelings. “Nai Nai’s brain works more than yours and she’s dead! Do you even belong to this family?”

This was why Vivian had left. Magic lent itself to temperament.

“Maybe not,” said Vivian.

When Vivian was angry she did it with the same single-minded energy she did everything else. This was why she decided to go wedding dress shopping in the week of her grandmother’s funeral.

There were numerous practical justifications, actually. She went through them in her head as she drove past bridal studios where faceless mannequins struck poses in clouds of tulle.

“Cheaper to get it here than overseas. Not like I’m helping much at home what. Not like I was so close to Nai Nai.”

She ended up staring mournfully at herself in the mirror, weighted down by satin and rhinestones. Did she want a veil? Did she like lace? Ball gown or mermaid shape?

She’d imagined her wedding dress as being white and long. She hadn’t expected there to be so many permutations on a theme. She felt pinned in place by the choices available to her.

The shop assistant could tell her heart wasn’t in it.

“Some ladies like other color better,” said the shop assistant. “You want to try? We have blue, pink, peach, yellow—very nice color, very feminine.”

“I thought usually white?”

“Some ladies don’t like white because—you know—” the shop assistant lowered her voice, but she was too superstitious to say it outright. “It’s related to a not so nice subject.”

The words clanged in Vivian’s ears. Briefly light-headed, she clutched at the back of a chair for balance. Her hands were freezing. In the mirror the white dress looked like a shroud. Her face hovering above it was the face of a mourner, or a ghost.

“Now that I’ve tried it, I’m not sure I like Western gown so much,” said Vivian, speaking with difficulty.

“We have cheongsam or qun kua,” said the shop assistant. “Very nice, very traditional. Miss is so slim, will suit the cheongsam.”

The jolt of red brocade was a relief. Vivian took a dress with gold trimmings, the highest of high collars and an even higher slit along the sides. It was as red as a blare of trumpets, as red as the pop of fireworks.

This fresh chili red had never suited her. In it she looked paler than ever, washed out by the vibrant shade. But the color was a protective charm. It laid monsters to rest. It shut out hungry ghosts. It frightened shadows back into the corners where they belonged.

Vivian crept home with her spoils. That night she slept and did not dream of anything.

The next morning she regretted the purchase. Her fiancé would think it was ridiculous. She couldn’t wear a cheongsam down the aisle of an Anglican church. She would take it back to the boutique and return it. After all the white satin mermaid dress had suited her. The sweetheart neckline was so much more flattering than a mandarin collar.

She shoved the cheongsam in a bag and tried to sneak out, but Wei Yi was sitting on the floor of the laundry room, in the way of her exit. She was surrounded by webs of filigreed red paper.

“What’s this?” said Vivian.

“It’s called paper cutting,” said Wei Yi, not looking up. “You never see before meh?”

On the floor the paper cuttings unfurled. Some were disasters: a mutilated fish floated past like tumbleweed; a pair of flirtatious girls had been torn apart by an overly enthusiastic slash. But some of the pieces were astounding.

“Kwan Yin,” said Vivian.

The folds in the goddess’s robes had been rendered with extraordinary delicacy. Her eyes were gentle, her face double-chinned. Her halo was a red moon circled by ornate clouds.

“It’s for Nai Nai,” said Wei Yi. “Maybe Kwan Yin will have mercy on her even though she’s so blasphemous.”

“Shouldn’t talk like that about the dead,” said Vivian.

Wei Yi rolled her eyes, but the effort of her craft seemed to be absorbing all her evil energies. Her response was mild: “It’s not disrespectful if it’s true.”

Her devotion touched Vivian. Surely not many seventeen-year-olds would spend so much time on so laborious a task. The sleet of impermanent art piled around her must have taken hours to produce.

“Did Nai Nai teach you how to do that?” Vivian said, trying to get back on friendlier ground.

Wei Yi’s face spasmed.

“Nai Nai was a rubber tapper with seven children,” she said. “She can’t even read! You think what, she was so free she can do all these hobbies, is it? I learnt it from YouTube lah!”

She crumpled the paper she was working on and flung it down on the floor to join the flickering red mass.

“Oh, whatever!” said Vivian in the fullness of her heart.

She bought the whitest, fluffiest, sheeniest, most beaded dress she could find in the boutique. It was strapless and low-backed to boot. Nai Nai would have hated it.

That night Vivian dreamt of her grandmother.

Nai Nai had climbed out of her coffin where she had been lying in the living room. She was wearing a kebaya, with a white baju and a batik sarong wrapped around her hips. No modern creation this—the blouse was fastened not with buttons but with kerongsang, ornate gold brooches studded with pearls and rhinestones.

Nai Nai was struggling with the kerongsang. In her dream Vivian reached out to help her.

“I can do!” said Nai Nai crossly. “Don’t so sibuk.” She batted at the kerongsang with the slim brown hands that had been so deft in life.

“What’s the matter? You want to take it off for what?” said Vivian in Hokkien.

“It’s too nice to wear outside,” Nai Nai complained. “When I was alive I used safety pins and it was enough. All this hassle just because I am like this. I didn’t save Yeh Yeh’s pension so you can spend on a carcass!”

“Why do you want to go outside?” Vivian took the bony arm. “Nai Nai, come, let’s go back to sleep. It’s so late already. Everybody is sleeping.”

Nai Nai was a tiny old lady with a dandelion fluff of white hair standing out from her head. She looked nothing like the spotty, tubby, furiously awkward Wei Yi, but her expression suddenly showed Vivian what her sister would look like when she was old. The contemptuous exasperation was exactly the same.

“If it’s not late, how can I go outside?” she said. “I have a long way to go. Hai!” She flung up her hands. “After they bury me, ask the priest to give you back the kerongsang.”

She started hopping towards the door, her arms held rod-straight out in front of her. The sight was comic and horrible.

This was the secret the family had been hiding from Vivian. Nai Nai had become a kuang shi.

“Nai Nai,” choked Vivian. “Please rest. You’re so old already, shouldn’t run around so much.”

“Don’t answer back!” shouted Nai Nai from the foyer. “Come and open the door for Nai Nai! Yeh Yeh will be angry. He cannot stand when people are late.”

Vivian envisioned Nai Nai hopping out of the house—past the neighborhood park with its rustling bushes and creaking swings, past the neighbors’ Myvis and Peroduas, through the toll while the attendant slumbered. She saw Nai Nai hopping along the curves of the Titiwangsa mountains, her halo of hair white against the bleeding red of the hills where the forests had peeled away to show the limestone. She saw Nai Nai passing oil palm plantations, their leaves dark glossy green under the brassy glare of sunshine—sleepy water buffalo flicking their tails in wide hot fields—empty new terrace houses standing in white rows on bare hillsides. Up the long North-South Expressway, to her final home.

“Nai Nai,” said Vivian. Don’t leave us, she wanted to say.

“Complain, complain!” Nai Nai was slapping at the doorknob with her useless stiff hands.

“You can’t go all that way,” said Vivian. She had an inspiration. “Your sarong will come undone.”

Whoever had laid Nai Nai out had dressed her like a true nyonya. The sarong was wound around her hips and tucked in at the waist, with no fastenings to hold it up.

“At my age, who cares,” said Nai Nai, but this had clearly given her pause.

“Come back to sleep,” coaxed Vivian. “I’ll tell Mummy. Bukit Tambun, right? I’ll sort it out for you.”

Nai Nai gave her a sharp look. “Can talk so sweetly but what does she do? Grandmother is being buried and she goes to buy a wedding dress!”

Vivian winced.

“The dress is not nice also,” said Nai Nai. “What happened to the first dress? That was nice. Red is a happy color.”

“I know Nai Nai feels it’s pantang, but—”

“Pantang what pantang,” snapped Nai Nai. Like all witches, she hated to be accused of superstition. “White is a boring color! Ah, when I got married everybody wanted to celebrate. We had two hundred guests and they all had chicken to eat. I looked so beautiful in my photo. And Yeh Yeh…”

Nai Nai sank into reminiscence.

“What about Yeh Yeh?” prompted Vivian.

“Yeh Yeh looked the same as always. Like a useless playboy,” said Nai Nai. “He could only look nice and court girls.”

“Then you want to be buried with him for what?”

“That’s different,” said Nai Nai. “Whether I’m a good wife doesn’t have anything to do with what he was like.”

As if galvanized by Vivian’s resistance, she turned and made to hit the door again.

“If you listen to me, I’ll take the dress back to the shop,” said Vivian, driven by desperation.

Nai Nai paused. “You’ll buy the pretty cheongsam?”

“If you want also I’ll wear the kua,” said Vivian recklessly.

She tried not to imagine what her fiancé would say when he saw the loose red jacket and long skirt, embroidered in gold and silver with bug-eyed dragons and insectoid phoenixes. And the three-quarter bell sleeves, all the better to show the wealth of the family in the gold bracelets stacked on the bride’s wrists! How that would impress her future in-laws.

To her relief, Nai Nai said, “No lah! So old-fashioned. Cheongsam is nicer.”

She started hopping back towards the living room.

Vivian trailed behind, feeling somehow as if she had been outmaneuvered.

“Nai Nai, do you really want to be buried in Penang?”

Nai Nai peered up with suspicion in her reddened eyes as Vivian helped her back into the coffin.

“You want to change your mind, is it?”

“No, no, I’ll get the cheongsam. It’ll be in my room by tomorrow, I promise.”

Nai Nai smiled.

“You know why I wanted you all to call me Nai Nai?” she said before Vivian closed the coffin. “Even though Hokkien people call their grandmother Ah Ma?”

Vivian paused with her hand on the lid.

“In the movies, Nai Nai is always bad!”

Vivian woke up with her grandmother’s growly cackle in her ears.

Wei Yi was in the middle of a meltdown when Vivian came downstairs for breakfast. Ma bristled with relief:

“Ah, your sister is here. She’ll talk to you.”

Wei Yi was sitting enthroned in incandescence, clutching a bread knife. A charred hunk of what used to be kaya toast sat on her plate. The Star newspaper next to it was crisping at the edges.

Vivian began to sweat. She thought about turning on the ceiling fan, but that might stoke the flames.

She pulled out a chair and picked up the jar of kaya as if nothing was happening. “What’s up?”

Wei Yi turned hot coal eyes on Vivian.

“She doesn’t want to kill the dogs wor,” said Ma. “Angry already.”

“So? Who ask you to kill the dogs in the first place?” said Vivian.

“Stupid,” said Wei Yi. Her face was very pale, but her lips had the dull orange glow of heated metal. Fire breathed in her hair. A layer of ash lay on the crown of her head.

“Because of Nai Nai,” Ma explained. “Wei Yi heard the blood of a black dog is good for Nai Nai’s… condition.”

“It’s not right,” said Wei Yi. “It’s better for Nai Nai if—but you won’t understand one.”

Vivian spread a layer of kaya on her piece of bread before she answered. Her hands were shaking, but her voice was steady when she spoke.

“I think Ma is right. There’s no need to kill any dogs. Nai Nai is not serious about being a kuang shi. She’s just using it as an emotional blackmail.” She paused for reflection. “And I think she’s enjoying it also lah. You know Nai Nai was always very active. She likes to be up and about.”

Wei Yi dropped her butter knife.

“Eh, how you know?” said Ma.

“She talked to me in my dream last night because she didn’t like the wedding dress I bought,” said Vivian.

Ma’s eyes widened. “You went to buy your wedding dress when Nai Nai just pass away?”

“You saw Nai Nai?” cried Wei Yi. “What did she say?”

“She likes cheongsam better, and she wants to be buried in Penang,” said Vivian. “So I’m going to buy cheongsam. Ma, should think about sending her back to Penang. When she got nothing to complain about she will settle down.”

“Why she didn’t talk to me?” said Wei Yi. Beads of molten metal ran down her face, leaving silver trails. “I do so many jampi and she never talk to me! It’s not fair!”

Ma was torn between an urge to scold Vivian and the necessity of comforting Wei Yi. “Girl, don’t cry—Vivian, so disrespectful, I’m surprise Nai Nai never scold you—”

“Yi Yi,” said Vivian. “She didn’t talk to you because in Nai Nai’s eyes you are perfect already.” As she said this, she realized it was true.

Wei Yi—awkward, furious, and objectionable in every way—was Nai Nai’s ideal grandchild. There was no need to monitor or reprimand such a perfect heir. The surprise was that Nai Nai even thought it necessary to rise from the grave to order Vivian around, rather than just leaving the job to the next witch.

Of course, Nai Nai probably hadn’t had the chance to train Wei Yi in the standards expected of a wedding in Nai Nai’s family. The finer points of bridal fashion would certainly escape Wei Yi.

“Nai Nai only came back to scold people,” said Vivian. “She doesn’t need to scold you for anything.”

The unnatural metallic sheen of Wei Yi’s face went away. Her hair and eyes dimmed. Her mouth trembled.

Vivian expected a roar. Instead Wei Yi shoved her kaya toast away and laid her head on the table.

“I miss Nai Nai,” she sobbed.

Ma got up and touched Vivian on the shoulder.

“I have to go buy thing,” she whispered. “You cheer up your sister.”

Wei Yi’s skin was still hot when Vivian put her arm around her, but as Vivian held her Wei Yi’s temperature declined, until she felt merely feverish. Her tears went from scalding to lukewarm.

“Nai Nai, Nai Nai,” she wailed in that screechy show-off way Vivian had always hated. When they were growing up Vivian had not believed in Wei Yi’s tears—they seemed no more than a show, put on to impress the grown-ups.

Vivian now realized that the grief was as real as the volume deliberate. Wei Yi did not cry like that simply because she was sad, but because she wanted someone to listen to her.

In the old days it had been a parent or a teacher’s attention that she had sought. These howls were aimed directly at the all-too-responsive ears of their late grandmother.

“Wei Yi,” said Vivian. “I’ve thought of what you can do for Nai Nai.”

For once Wei Yi did not put Vivian’s ideas to scorn. She seemed to have gone up in her sister’s estimation for having seen Nai Nai’s importunate spectre.

Vivian had a feeling Nai Nai’s witchery had gone into Wei Yi’s paper cutting skills. YouTube couldn’t explain the unreal speed with which she did it.

Vivian tried picking up Wei Yi’s scissors and dropped them, yelping.

“What the—!” It had felt like an electric shock.

Wei Yi grabbed the scissors. “These are no good. I give you other ones to use.”

Vivian got the task of cutting out the sarong—a large rectangular piece of paper to which Wei Yi would add the batik motifs later. When she was done Wei Yi took a look and pursed her lips. The last time Vivian had felt this small was when she failed her first driving test two minutes after getting into the car.

“OK ah?”

“Not bad,” said Wei Yi unconvincingly. “Eh, you go help Ma do her whatever thing lah. I’ll work on this first.”

A couple of hours later she barged into Vivian’s room. “Why you’re here? Why you take so long? Come and see!”

Vivian got up sheepishly. “I thought you need some time to finish mah.”

“Nonsense. Nai Nai going to be buried tomorrow, where got time to dilly-dally?” Wei Yi grasped her hand.

The paper dress was laid in crisp folds on the dining table. Wei Yi’s scissors had rendered the delicate lace of the kebaya blouse with marvelous skill. Peacocks with uplifted wings and princely crowns draped their tails along the hems, strutted up the lapels, and curled coyly around the ends of the sleeves. The paper was chiffon-thin. A breath set it fluttering.

The skirt was made from a thicker, heavier cream paper. Wei Yi had cut blowsy peonies into the front and a contrasting grid pattern on the reverse. Vivian touched it in wonder, feeling the nubby texture of the paper under her fingertips.

“Do you think Nai Nai will like it?” said Wei Yi.

Vivian had to be honest. “The top is a bit see-through, no?”

“She’ll have a singlet to wear underneath,” said Wei Yi. “I left that for you to do. Very simple one. Just cut along the line only.”

This was kindness, Wei Yi style.

“It’s beautiful, Yi Yi,” said Vivian. She felt awkward—they were not a family given to compliments—but once she’d started it was easy to go on. “It’s so nice. Nai Nai will love it.”

“Ah, don’t need to say so much lah,” Wei Yi scoffed. “‘OK’ enough already. I still haven’t done shoe yet.”

They burnt the beautiful cream kebaya as an offering to Nai Nai. It didn’t go alone—Wei Yi had created four other outfits, working through the night. Samfu for everyday wear; an old-fashioned loose, long-sleeved cheongsam (“Nicer for older lady. Nai Nai is not a Shanghai cabaret singer”); a sarong for sleeping in; and a Punjabi suit of all things.

“Nai Nai used to like wearing it,” said Wei Yi when Vivian expressed surprise. “Comfortable mah. Nai Nai likes this simple kind of thing to wear for every day.”

“Four is not a good number,” said Vivian. “Maybe should make extra sarong?”

“You forgot the kebaya. That’s five,” Wei Yi retorted. “Anyway she die already. What is there to be pantang about?”

They threw in the more usual hell gold and paper mansion into the bonfire as well. The doll servants didn’t burn well, but melted dramatically and stuck afterwards.

Since they were doing the bonfire outside the house, on the public road, this concerned Vivian. She chipped doubtfully away at the mess of plastic.

“Don’t worry,” said Ma. “The servants have gone to Nai Nai already.”

“I’m not worried about that,” said Vivian. “I’m worried about MPPJ.” She couldn’t imagine the local authorities would be particularly pleased about the extra work they’d made for them.

“They’re used to it lah,” said Ma, dismissing the civil service with a wave of the hand.

They even burnt the fake Gucci bag and the polo shirt in the end.

“Nai Nai will find some use for it,” said Wei Yi. “Maybe turn out she like that kind of style also.”

She could afford to be magnanimous. Making the kebaya had relieved something in Wei Yi’s heart. As she’d stood watch over the flames to make sure the demons didn’t get their offerings to Nai Nai, there had been a serenity in her face.

As they moved back to the house, Vivian put her arm around her sister, wincing at the snap and hiss when her skin touched Wei Yi’s. It felt like a static shock, only intensified by several orders of magnitude.

“OK?”

Wei Yi was fizzing with magic, but her eyes were calm and dark and altogether human.

“OK,” replied the Witch of Damansara.

In Vivian’s dream a moth came fluttering into the room. It alighted at the end of her bed and turned into Nai Nai.

Nai Nai was wearing a green-and-white striped cotton sarong, tucked and knotted under her arms as if she were going to bed soon. Her hair smelled of Johnson & Johnson baby shampoo. Her face was white with bedak sejuk.

“Tell your mother the house is very beautiful,” said Nai Nai. “The servants have already run away and got married, but it’s not so bad. In hell it’s not so dusty. Nothing to clean also.”

“Nai Nai—”

“Ah Yi is very clever now, har?” said Nai Nai. “The demons looked at my nice things but when they saw her they immediately run away.”

Vivian experienced a pang. She didn’t say anything, but perhaps the dead understood these things. Or perhaps it was just that Nai Nai, with sixty-five years of mothering behind her, did not need to be told. She reached out and patted Vivian’s hand.

“You are always so guai,” said Nai Nai. “I’m not so worried about you.”

This was a new idea to Vivian. She was unused to thinking of herself—magicless, intransigent—as the good kid in the family.

“But I went overseas,” she said stupidly.

“You’re always so clever to work hard. You don’t make your mother and father worried,” said Nai Nai. “Ah Yi ah…” Nai Nai shook her head. “So stubborn! So naughty! If I don’t take care sekali she burn down the house. That girl doesn’t use her head. But she become a bit guai already. When she’s older she won’t be so free, won’t have time to cause so much problems.”

Vivian did not point out that age did not seem to have stopped Nai Nai. This would have been disrespectful. Instead she said,

“Nai Nai, were you really a vampire? Or were you just pretending to turn into a kuang shi?”

“Hai, you think so fun to pretend to be a kuang shi?” said Nai Nai indignantly. “When you are old, you will find out how suffering it is. You think I have time to watch all the Hong Kong movies and learn how to be a vampire?”

So that was how she did it. The pale vampirish skin had probably been bedak sejuk as well. How Nai Nai had obtained bedak sejuk in the afterlife was a question better left unasked. Vivian had questions of more immediate interest anyway.

“If you stayed because you’re worried about Wei Yi, can I return the cheongsam to the shop?”

Nai Nai bridled. “Oh, like that ah? Not proud of your culture, is it? If you want to wear the white dress, like a ghost, so ugly—”

“Ma wore a white dress on her wedding day. Everyone does it.”

“Nai Nai give you my bedak sejuk and red lipstick lah. Then you can pretend to be kuang shi also!”

“I’ll get another cheongsam,” said Vivian. “Not that I don’t want to wear cheongsam. I just don’t like this one so much. It’s too expensive.”

“How much?”

Vivian told her.

“Wah, so much ah,” said Nai Nai. “Like that you should just get it tailored. Don’t need to buy from shop. Tailored is cheaper and nicer some more. The seamstress’s phone number is in Nai Nai’s old phonebook. Madam Teoh.”

“I’ll look,” Vivian promised.

Nai Nai got up, stretching. “Must go now. Scared the demons will don’t know do what if I leave the house so long. You must look after your sister, OK?”

Vivian, doubtful about how any attempt to look after Wei Yi was likely to be received, said, “Ah.”

“Nai Nai already gave Ah Yi her legacy, but I’ll give you yours now,” said Nai Nai. “You’re a good girl, Ah Lin. Nai Nai didn’t have chance to talk to you so much when you were small. But I’m proud of you. Make sure the seamstress doesn’t overcharge. If you tell Madam Teoh you’re my granddaughter she’ll give you discount.”

“Thank you, Nai Nai,” said Vivian, but she spoke to an empty room. The curtains flapped in Nai Nai’s wake.

On the floor lay a pile of clothes. Moonlight-sheer chiffon, brown batik, maroon silk and floral print cotton, and on top of this, glowing turquoise even in the pale light of the moon, the most gilded, spangled, intricately embroidered Punjabi suit Vivian had ever seen.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kill Hollows: Chapter 1

CHAPTER ONE:

BHA-AAB

Robert Warrington’s Journal

Token-Oak, Winter of 1991

10,562 days before the Syndemic

________________________________________

When I say my grandma knew the apocalypse was coming, I don’t mean it in a general sense. She didn’t just foreshadow dark times on the horizon. I believe she saw what was happening: the burning cities, the collapse of agriculture, and corpses along the interstate piled like trash at a landfill. She felt it, too: The intense pressure of knowing ate at her heart and eventually killed her. The incredible weight of this bleak future smothered her before she could adequately warn anyone but me.

She died on a Tuesday right after the wheat harvest. Even in death, the family would say, she accommodated my grandfather's schedule. Grandma planned her own passing—thou the doctors said the aneurysm was a fluke—right down to what she wore to the hospital. One day, Gramps came home from the farm and found her on the sunflower linoleum in the kitchen convulsing. Yet she packed a bag, stashed a week’s worth of leftovers in the fridge, and paid the bills a month in advance. Grandma was spooky like that. She had the foresight of a Cajun mystic.

Grandma had these great big eyes, but she rarely opened them more than a squint. She hid them behind reading frames she bought in the plastic turnstile at the local IGA Supermarket. With her head tilted and her reading glasses perched on the tip of her nose, she dug into people with those eyes. She had this way of looking into a person, right inside their thoughts, like she was vetting them for trustworthiness suitable enough to be her confidant. Few met her standards.

Grandma was a collector, like many women from small towns, she had a “power animal.” She bought cookie jars, bric-a-brac, and mawkish paintings of her “power animal” that personified her best. For my grandma, it was owls: spooky ass, head-turning-180-degree-Exorcist-style, big-eyed, predatory, nocturnal, clawed, and sharp-beaked owls. The damned things filled her home, lurking in every nook, following you with their eyes. I saw my grandma in all those owls.

Grandma loved to scare little kids. Scare them in a way that was simultaneously welcoming and bone-chilling. Over a plate of fresh-baked cookies—chocolate chip that were puffy, crunchy on the outside, yet doughy in the middle—she'd offer you her “insights” of the world. The cookies lowered your guard and the way she spoke really sucked you in, always in a gentle coo. “You know, Bob, those black spots on BBQ chips? Those are boogers from people that work at the factory.” Or, ever so subtly, “I once filled a glass dish with Coke and submerged a metal spoon in it and left it overnight. In the morning, the spoon was gone … completely dissolved. Now, Bob, imagine what that stuff does to your stomach overnight? Have you been checking your poop for blood?” And, let's not forget her stories about chocolate, “that stuff is made from the coco plant, you know, that’s where the 'cho' comes from. Well, the plant is used to manufacture illegal narcotics. A little white powder called CHOcaine. There is something in the plant that pulls people in. Changes their brain. Every bit of ‘Cho’ you ingest is a step closer to being a drug addict when you’re older. A step closer to sleeping in gutters, having no teeth, and never wiping your ass with toilet paper. So, enjoy that Butterfinger, Bob, enjoy it real… slow.”

Yeah, I loved my grandma. Even though she was mean and wrong about a lot of things. I remember her stories because she conveyed them with a quiet passion. She was the only woman I ever met that could scare me to death and make me feel loved unconditionally at the same time.

Grandma grew up in the town of Token-Oak and stayed there her whole life. A town named for the prevalence of thousand-year-old oaks. In its heyday, Token-Oak was a Midwestern postcard town, picturesque in a Norman Rockwell kind of way. In the fall, the foliage from the deep-rooted oaks provided a pallet of Autumn colors so brilliant and varied that people would pull over on the interstate to take family photos with the hills in the background. In recent years, however, the oaks suffered a debilitating disease causing their leaves to fall. These hulking relics stand all over the town leafless and dying, their twisting fingers reaching out into space.

Before things went to hell, townsfolk talked about Token-Oak like a distant relative that once had a multimillion-dollar empire. They never mentioned that the relative spent the fortune on whores and coke only to wind up penniless and using the daily paper as a blanket. Token-Oakeans bragged on the oil booms and the new interstate and the influx of traffic as “progress.” They never mentioned the meth labs, violence, and the strange detachment that permeated the town. No one ever discussed the dark underbelly of Token-Oak, no one except my grandma.

Grandma and this will sound crazy, could predict future events. Perhaps not the exact time or outcome, but she could see the future. Frankly, all grandmothers possess this gift in varying degrees of intensity. Most grandmothers can look at a young man and tell you with surprising accuracy if a kid will be a success in life. In a moderately advanced form, some grandmothers can predict the downfall of a kid, but the advanced ones, women like my grandmother, could predict success, downfall, and the immediate steps necessary to correct the downward spiral. Grandma had the trifecta, the holy trinity, of grandmotherly prognostication.

Grandma knew where I was headed a long time before I got there. She warned me, and my life happened precisely like she said it would. You see, I was what many considered a smart kid, but one that was intensely troubled by emotions. Back in the Eighties, parents didn't throw around psychobabble. Today, I probably would have landed somewhere on the spectrum. In 1986, I was just a fucked-up little kid struggling through life.

Life was one hell of a struggle.

My dad overdosed when I was six. My mom, my brother—his name was Jacob—and I walked into our trailer on a Friday night after going to the County Fair. Dad was laying on the dirty carpet next to the couch. He had this white froth around his mouth, and one of his eyes was rolled back in his head. In his left hand, he held a hypodermic needle. Mom dropped me in the doorway and released a milk-curdling scream. Jacob and I just stood there, in the living room, looking at Dad.

The whole trailer park was around our house for hours. The cops took Dad away in a black sack and combed through the house looking for more drugs. They took buckets and bottles and dirty tubing out of our back room. Pretty much anything that could be used to make meth.

There was one thing that the cops missed. A few days later, I found a spoon under the couch. The backside was burnt black. The neck of the spoon was wrapped with electrical tape. The bowl of the spoon had a white film, and a piece of cotton singed to it, but it still shined. I’d lay on my twin mattress at the far end of the trailer and look at my upside-down reflection in the concave of that spoon for hours.

My mom caught me with it weeks later. “Where did you get this?” she said in a voice that was somehow a desperate plea and a rage-filled question. I told her that I found it under the couch, “underneath my dad.” And Mom cried so long I thought she might have died. But she left me with that dirty spoon.

The next day, Mom went to buy milk at the gas station. A semi-truck hit her car over the bridge by the tire plant. The driver that hit her was so high on meth that he never let off the gas. The roaring engine of the Freightliner slammed her Datsun hatchback over the guardrail and into the icy water of the Smoky River fifty feet below.

In a three-week span, I lost both my parents to drugs. That period changed my life, as you might imagine. Jacob and I went to live with our grandparents. It only took the better part of a week to figure out it was an arrangement that was doomed to fail. Grandma was always watching me, always warning that I couldn’t let my past ruin my life. “You drew a rough hand,” she’d say, “but you have to persevere. Use this pain, don’t let it use you.” She was always telling me to “put my suffering to work,” like it was a fucking mule that could till a field. She watched me with those huge eyes, like a predatory bird.

I still remember every detail of the afternoon Grandma warned me about the future. And that was decades ago. I was at her house on a chilly October afternoon around my birthday. I was shooting hoops with Jacob just before dinner. We had just finished watching the movie Hoosiers. Oh man, we loved to watch movies back then. The final scene was so inspiring to Jacob and me that we ran outside to impersonate the movie protagonist, Jimmy Chitwood. Hoosiers meant a lot to Caucasian farm kids in the Midwest. A good jump shot combined with “fundamentals and defense”—and a shitload of freckles—was all it took for your name to be whispered among the wheat stubble for all-time. It was all polished wood and step back jumpers against rowdy-ass opponents. They balled hard in Hoosiers, like the NBA in the early ‘90s, it was football in shorts.

I was ten years old back then. Jacob was twelve.

Jacob and I were adopted by our grandparents late in life. Both were well into their fifties, long past the age when they had the energy to deal with his shit. Jacob’s life was a cycle in three repeating patterns: (1) he received little attention, so he did something vicious; (2) he received a beating for his actions that made him worse, and the grandparents felt guilty; and (3) then they showered him with toys and freedom. Jacob was raised by television, and he returned to this well of knowledge again and again. He saw the world through a prism of movie montages and climactic scenes. In this cycle, Jacob developed an innate fixation for creating fear and causing pain. Even at twelve, he was growing into a “special” kid.

We were playing a game of one-on-one on Grandma's driveway. The rotted plywood hoop was just above the garage door. I was smoking Jacob pretty good. He was older, taller, and had the lanky frame of a b-baller but lacked athletic ability. I stole the ball from him regularly, and that really pissed him off.

“Bha-aaaaaaaab,” Jacob would say in this voice that drew out the vowels like a bone saw. It was a portmanteau word of my nickname and the sound that Jacob said I made when he hit me. There was something about that way Jacob said it, in this sotto voce hiss that was so full of sarcasm and hate: “Bha-aaaaaaab, don’t be a bitch.” Every time I showed weakness: “Bha-aaab.” If I displayed any awkwardness in a social setting: “Bha-aaab.” If I was too affectionate with my family pet: “Bha-aaaab.” If I flinched when he was about to hit me: “Bha-aaab.” That name, said in that voice, came to epitomize everything I hated about myself. It was as if all my adolescent self-reproach came to life when Jacob hissed that name.

Jacob had this weird thing about movies. He’d see it, and he’d do it. Sometimes, when a pivotal scene came on, I’d look over at him, and his face alone was worth the price of admission. His eyes wide, one eyebrow raised in curiosity, and mouth agape in utter fascination. He studied movie characters: their mannerisms, vocabulary, intonation, and style of dress. He lost himself inside that tubed box like no one I’d ever seen before or since. Then he’d head out into the world and imitate. Art became life. Fantasy became a reality. For Jacob, there was never a wall separating make-believe. It was like he existed in this alternate universe that mixed make-believe and real life like fuel and air into a jet engine. He soared into the deep recesses of the back of his mind.

The game, just like in the movie, degenerated into jail ball. It was all hip checks, and awkward curse words dropped by kids who didn't fully understand their meaning. "Nice shot, you damn gigolo" and "you play like you got a tampon in your ass."

Grandma was doing dishes in the kitchen and watching us through translucent curtains. The kitchen window was just up the stairs and overlooked the driveway basketball court. She often sat up there like a silent observer in a booth. I saw her silhouette every time I looked up. One time, I took the ball along the edge of the driveway towards the hoop and Jacob body-checked me into the garage door. The collision made a tremendous noise. Springs, plywood, and metal wheels erupted like a raucous crowd. I hit the pavement cursing up a storm. "What the balls was that, you fucking boot-licking gypsy?!"

I heard Grandma's swollen knuckles and skinny fingers wrapping on the window pane. Thomp, Thomp, THOMP! The curtains flew open, and we both saw her scowling down. She had wild eyes that trembled, though the rest of her stood motionless. I could see the air molecules around her head vibrating with energy. Her lips were pursed so tight they could cut through the metal of a spoon. It was a look developed through decades of parenting rowdy kids. It was her own version of the machine kill switch. Flip it, and everything comes to a complete stop.

At least for a while. The thin curtains slowly closed, and Jacob and I started playing again. A shot here. A few dribbles there. I grabbed the ball from Jacob and held it behind me while leaning forward. Both of Jacob’s palms faced toward me, his eyes on fire with rage. He looked like a mime performing the trapped-in-a-box routine.

Then we heard some sounds from the end of the driveway. It was the unmistakable clanging of empty gas bottles and the rattle of wrenches against the bed of Grandpa’s pickup truck. There was a nasal whine, a seething breath. Whatever it was, it sounded rushed.

I sat the ball down on the pavement and Jacob, and I tiptoed towards the truck.

A man was standing at the tailgate. His head down and his arms furiously rifled through the truck bed. He wore a beanie pulled down to the tips of his eyes. Open scabs dripped blood from his unshaven neck. The skin on his face sagged in loose pouches. His mouth was open, and his lips curled back on his teeth. His black, infected gums puffed outward. There was a filth to him, a layer of grime that indicated he hadn’t washed in a long while, maybe months. He wore the clothes of a younger person, but he looked like a haggard old man.

The man grabbed a canister of gas, removed the lid, and dumped out the contents. Gasoline vapors filled the air. Gramps had a 100-gallon tank bolted to the bed of his truck that he filled with anhydrous ammonia, a fertilizer that he used during the growing season. The man grabbed the spigot of anhydrous and twisted it open. The repugnant stench of anhydrous overpowered the gasoline. Jacob and I were fifteen feet away, but even from that distance, the fumes burned my eyes and ignited a burn in my throat. The man coughed and growled through the caustic stench as saliva drizzled from his black gums.

The man wore fingerless gloves. He spilled some of the anhydrous on his skin and yanked a hand away, shaking. The caustic liquid ate away at his exposed flesh, but he did not let go of the hose and stood there until the gas-can was full of anhydrous. His eyes squinted hard as he held the can under the spigot. I could smell his flesh burning.

Whenever Grandpa handled the anhydrous, he wore thick rubber gloves and a respirator. Jacob and I must have had eyes as wide as saucers.

When he was finished with the can, he looked up and saw Jacob and me. A loud inhale turned into an animalistic hiss. He was clenching his teeth so hard that his jaw shook. There was a twitch inside him that crawled up from his waist and snarled up his back. His arms and head bobbed and contorted in inexplicable patterns. His eyes swam in their sockets as he tried to focus on us. He had the body of a man, but there was something very inhuman about him. He took heavy and irregular breaths, punctuated by desperate gasps of air. It was like he was fighting inside himself just to live.

He turned away from us as if he heard a sound in the distance. He broke into a run. His limbs stammering and shaking in a disjointed, yet frantic, gallop. He hit the end of the street—two hundred feet—in less than five seconds. The canister of ammonia sloshed caustic liquid in his wake. As he turned into the alley at the end of the street, another figure met him and then a third. They grouped together and disappeared over a dog-eared fence. We watched them run across the railroad tracks and sprint into the grass field by McClintock’s Tree Farm.

“What was he doing?” I said, looking up at Jacob. And Jacob had the TV face. His mouth was open, and his head was tilted to one side. His unblinking eyes watched the men disappear over the fence. “Jacob,” I said as I reached out to touch him.

Jacob’s trance disappeared, and he blinked slow. He turned his head and looked down at me. “He needed that stuff to take back to the Hollows… the anhydrous,” Jacob said.

“What was wrong with him?”

Jacob shrugged and looked back at the fence where the man disappeared. “I don’t know. Did you hear that fucker breathe? Sounded like a dying cow,” Jacob said. And he swiped the ball from me and turned towards the basket.

When we turned, Grandma was standing there holding a double-barreled Winchester. The gun was cracked open, and two fresh shells were resting inside the break action. The brass circles of the shells sparkled in the October sunshine. She stood for a long while intensely watching the men disappear into the tall-grass field.

She grabbed me by the neck and pulled me toward the driveway. I fell, and she kept pulling.

Once we were near the basketball hoop at the far end of the driveway, she let go: “If you were standing at the end of that tailgate, he would have killed you both. If you ever—ever! —see a person like that, you run. You get inside the house and lock the doors. There are things in this town, bad things. And don’t you think for a minute that just because you’re a kid, that thing wouldn’t open you up from belly button to Adam’s apple.”

Grandma took a long breath. She brought her hand to cover her eyes and let out a wobbly exhale. Grandma took me up and hugged me so hard I thought she broke my ribs.

“Why was he breathing like that?” Jacob asked.

Grandma looked back down the drive for a long while. She covered the sun from her eyes as she scanned the fences in the neighborhood. Then she looked at Jacob and I and shook her head. “He breathes like that because he’s dying. Been slowly dying for a long time. And one of these days, this whole damn town will be full of people like that.”

Grandma pulled the shells from the Winchester and snapped it shut. She slipped the shells in her coat pocket. She looked around and disappeared inside.

Grandma was a woman of idiosyncrasies. She had rules—live or die rules—that she never broke. She wouldn’t leave the house at night for any reason. She loved her two Alaskan Huskies, and listened to them like they were people. Responding to each one of their barks while in the house by looking out the shutters to inspect the neighborhood. There was a suspicious side to her, especially people in authority or control. I once saw her bolt from the Token-Oak hospital when a doctor tried to take her blood pressure. “I don’t trust him, and neither should you,” was all she ever said. It was like she expected the worst in people and searched for it everywhere. For a gregarious kid like me, that coldness was often grating. I could tell that beneath all Grandma’s issues, she loved us furiously.

Grandma and I butted heads like two rams on a mountain. She tried to keep me contained, and I was always busting out. She would correct me, and I’d fly off course. It was the ebb and flow of our dynamic.

After Grandma was inside, Jacob looked over at me. “Did you hear that shit? She is losing it,” Jacob said in a wobbly, effeminate voice, “the town will be full of people like that,” as he imitated Grandma standing with the Winchester. “She needs to be in a place for crazy people.”

After a while, Jacob and I were back to jail ball. Within minutes, I caught an elbow to the face and hit the pavement. I sprung up spraying profanities like a yard spreader. The curtains flew open, Grandma was standing in a dark kitchen. A vision of utter rage, she glared down upon us like the demon in Fantasia’s Night on Bald Mountain.

I was scared, but my anger outweighed my fear. What Jacob did was wrong, he was always wrong. I knew that she saw him, and yet she just stared. Grandma always cut him slack.

I waited until the curtain closed. Then it happened, the middle finger on my right hand extended and my arm shot up until my elbow straightened. Boom. There it was. I flipped my grandma off for only a split second. Turns out, that split second was enough.

Even Jacob, the twelve-year-old sadist, knew I’d made a tremendous mistake.

"You’re a dumbass,” Jacob said, “she saw that.”

“Whatever,” I said, holding the ball with both hands while leaning over.

I dismissed the thought and continued the game. Jacob began a new tactic, utterly uncharacteristic. He played softly, no longer pushing me around. It was like he wanted the game to end, just to see what would happen next. After five minutes of disinterested ball, we were done.

Jacob and I kicked our shoes off at the back door of Grandma’s house and stomped up the kitchen stairs. Grandma was standing at the sink and washing a set of dishes. Her back was facing me, and she did not offer her usual greeting.

I palmed the handle on the fridge door, yanking it open. A half-full container of cherry Kool-Aid was sitting on the top shelf whispering my name. I stood in the middle of the kitchen pouring the chilled, cherry goodness into a jelly jar. Grandma's back was toward me, her hunched shoulders wiggling as she scrubbed a pot in the sink. Jacob stood at the stove in between us. He had a subtle smile as he watched me.

As I took a drink of the cherry liquid, Jacob was the first to speak.

Jacob said, “Bob bent the garage door.”

This was such typical Jacob. His goal in life was to get people to lose it. He was gifted at this skill, like an aikido master throwing an attacking opponent off balance, Jacob knew just where, and how, to press. He kept memories of unhinged emotional responses in his mind like a running back keeps the game ball from a three-hundred-yard game.

"That's bullsh . . ." I said reflexively, only to be interrupted mid-profanity by Grandma's hand. She wheeled from the sink, flattened her palm, and threw a cat-quick right cross. It left the side of my face smashing my cheeks into my molars. All of this occurred in three-tenths of a second. Sometimes, life happens in a flash, but you remember it in excruciatingly slow detail. The way her fingers smashed the fatness of my cheek. How my lips curled as she followed through. The spinning jelly jar full of cherry Kool-Aid. Most of all, though, I remember the crime scene afterward.

Red Kool-Aid splattered all around the kitchen, in patterns so intricate that Jackson Pollock would've been jealous. The sunflower linoleum floor, the finger paintings hanging by magnets on the fridge, even the bubble screen on Grandma’s 9" kitchen TV were covered in the pitter-patter Kool-Aid splatter. The red stuff was everywhere, a fine mist of blood like someone’s head had exploded. I laid on the linoleum floor looking up at Grandma.

“It was Jacob… he did it,” I whimpered from the floor as I pointed at Jacob.

She towered over me with her right hand still cocked. Bending down, she calmed herself, and said the unforgettable words, “You can’t control yourself. It’s always someone else’s fault. And by the time you figure it out, I'll be dead."

Then Grandma leaned down and grabbed me by the collar of my T-shirt, pulled me closer, and said in a hissing whisper, “there is going to come a time, after I am dead when you’ll need Jacob. And he’ll be there. Family runs deep, and those bonds are forever. All this you’re going through is just training for what’s coming. And when it gets here, you’ll be thankful.”

Grandma wiped her hands off on a towel and walked out of the kitchen.

Jacob stood by the stove with an orgiastic smile. He had this look, an I’m-in-control-of-a-delicious-situation visage. His smile was so crooked and fulfilled, half his face looked like the Joker from Batman. It was a look that said, "told you so" and "eat shit" with seamless ferocity. The way his upper row of teeth glowed under his upper lip, the evil twinkle in his eye, even the way he held his head slightly upturned and to the side. For a twelve-year-old kid, he could play the douchebag card with uncanny skill.

“Fuck you, Jacob,” I said, sulking out of the kitchen.

I heard him laughing hysterically as I descended the basement stairs. He yelled after me, “Ahhh, Ba-aaaab, you going to need me someday. You’re welcome.”

The basement was the furthest spot in the house away from my grandmother, and she needed time to calm. The basement was quiet, had shag carpet, and puffy furniture. The house was not air-conditioned, but the basement was naturally cool. It was a place of respite from family dysfunction and summer heat.

At the base of the stairs, just to the left, there was my grandfather's office. A room unlike any other. Grandpa’s U-shaped desk had a glass top. He slid decades of old pictures and newspaper clippings under the glass. It was a tableau of his life and our family history. I sat in Grandpa’s office chair with my elbows on the desk, cradling my head in my hands.

Grandpa was a high school history teacher, county politician, and farmer. An avid democrat—the “party of the little people,” he always said—he believed in the common man and would rail against the machine any chance that he got. He supported inmates and single moms and small businesses. Most of all, he loved a good underdog story. After all, who is a bigger underdog than farming teacher with four kids and a penchant for taking on societal problems? He even ran for state senate a few times and lost. Badly. Through all his endeavors, he became part of the political machine. He wrote scathing letters to the editor in the local newspaper whenever he saw a person slighted by “big business, big government, or big bullshit.” People hated him or loved him. In his office, he kept mementos that he treasured dearly.

The history in that room was personal and honest. On the doorframe, all Grandpa’s children had penciled their height from toddler age to present day. Under the glass on the desk, there were hundreds of pieces of paper. One was an article about my great-grandpa who died when his arm was ripped off in a threshing machine. He bled to death in the wheat stubble of our home place field. His last note, scratched with a pocket knife onto a painted piece of John Deere green metal, read: “I love you all. I did my best.” There was a photo of my grandfather and Bill Clinton, where Clinton wrote so charmingly, “If I had supporters like you in every state, I’d be king.” There were the election results for state senate, where Gramps only brought in 27 percent of the vote, glued to the top of his campaign slogan that read simply: “I teach.” Grandpa was so proud of that slogan.