#these messages brought to you by my breakfast. scrambled eggs and sausage with cheese and peppers

Text

when you have a food that you think is going to be a textural nightmare but somehow isn't, the clock has now begun. you have approximately five minutes before it is entirely inedible.

#these messages brought to you by my breakfast. scrambled eggs and sausage with cheese and peppers#it looked horrific and i was sure i wouldn't be able to actually eat it. to my delight i was and its actually delicious.#however.#made the mistake of trying to get my computer set up and the next bite i took was Not Great Texturally#so breakfast is now over

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

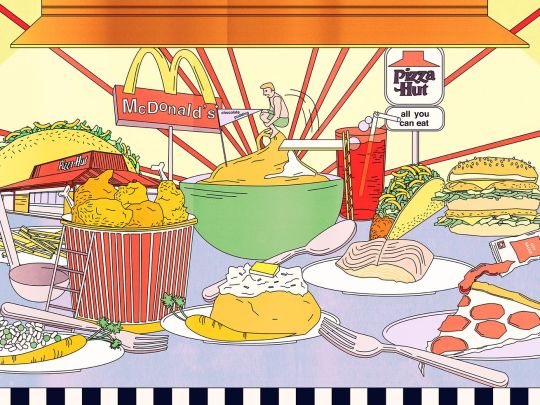

Fast-Food Buffets Are a Thing of the Past. Some Doubt They Ever Even Existed.

A McDonald’s breakfast buffet. An all-you-can-eat Taco Bell. This isn’t the stuff dreams are made of, but a real yet short-lived phenomenon.

When we think of buffets, we tend to think of their 1980s and early ’90s heyday, when commercial jingles for Sizzler might have been confused with our national anthem. We think of Homer Simpson getting dragged out of the Frying Dutchman, “a beast more stomach than man.” I think of my parents going on buffet benders resembling something out of Hunter S. Thompson’s life, determined to get their money’s worth with two picky kids.

What we don’t typically think about, however, is the fast-food buffet, a blip so small on America’s food radar that it’s hard to prove it even existed. But it did. People swear that all-you-can-eat buffets could be found at Taco Bell, KFC, and even under the golden arches of McDonald’s.

That it could have existed isn’t surprising. The fast-food buffet was inevitable, the culmination of an arms race in maximizing caloric intake. It was the physical manifestation of the American id: endless biscuits, popcorn chicken, vats of nacho cheese and sketchy pudding — so much sketchy pudding. Why, then, have so many of us failed to remember it? How did it become a footnote, relegated to the backwoods of myths and legends? There are whispers of McDonald’s locations that have breakfast buffets. Was there, in fact, a Taco Bell buffet, or is it a figment of our collective imaginations? Yes, someone tells me — an all-you-can-eat Taco Bell existed in her dorm cafeteria. Another person suggests maybe we were just remembering the nachos section of the Wendy’s Superbar.

The fast-food buffet was inevitable, the culmination of an arms race in maximizing caloric intake.

The fast-food buffet lives in a strange sort of ether. You can’t get to it through the traditional path of remembering. Was there actually a Pizza Hut buffet in your hometown? Search your subconscious, sifting past the red cups that make the soda taste better, past the spiffy new CD jukebox, which has Garth Brooks’s Ropin’ the Wind and Paul McCartney’s All the Best under the neon lamps. Search deeper, and you might find your father going up for a third plate and something remaining of the “dessert pizzas” lodged in your subconscious. This is where the fast-food buffet exists.

The history of the buffet in America is a story of ingenuity and evolution. Sure, it originated in Europe, where it was a classy affair with artfully arranged salted fish, eggs, breads, and butter. The Swedish dazzled us with their smorgasbords at the 1939 World Fair. We can then trace the evolution of the buffet through Las Vegas, where the one-dollar Buckaroo Buffet kept gamblers in the casino. In the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese immigrant families found loopholes in racist immigration laws by establishing restaurants. They brought Chinese cooking catered to American tastes in endless plates of beef chow fun and egg rolls. By the 1980s, buffets ruled the landscape like family dynasties, with sister chains the Ponderosa and the Bonanza spreading the gospel of sneeze guards and steaks, sundae stations and salad bars along the interstates. From Shoney’s to Sizzler, from sea to shining sea, the buffet was a feast fit for kings, or a family of four.

And of course, fast-food restaurants wanted in on the action. As fast-food historian and author of Drive-Thru Dreams Adam Chandler put it, “every fast food place flirted with buffets at some point or another. McDonald’s absolutely did, as did most of the pizza chains with dine-in service. KFC still has a few stray buffets, as well as an illicit one called Claudia Sanders Dinner House, which was opened by Colonel Sanders’ wife after he was forbidden from opening a competing fried chicken business after selling the company. Wendy’s Super Bar was short-lived, but the salad bar lived on for decades.”

How something can be both gross and glorious is a particular duality of fast food, like the duality of man or something, only with nacho cheese and pasta sauce.

In a 1988 commercial for the Superbar, Dave Thomas says, “I’m an old-fashioned guy. I like it when families eat together.” A Wendy’s executive described the new business model as “taking us out of the fast-food business.” Everyone agrees the Wendy’s Supernar was glorious. And gross, everyone also agrees. How something can be both gross and glorious is a particular duality of fast food, like the duality of man or something, only with nacho cheese and pasta sauce.

“I kind of want to live in a ’90s Wendy’s,” Amy Barnes, a Tennessee-based writer, tells me in between preparing for virtual learning with her teenagers. The Superbar sat in the lobby, with stations lined up like train carts. First, there was the Garden Spot, which “no one cared about,” a traditional salad bar with a tub of chocolate pudding at its helm, “which always had streams of salad dressing and shredded cheese floating on top.” Next up was the Pasta Pasta section, with “noodles, alfredo and tomato sauce…[as well as] garlic bread made from the repurposed hamburger buns with butter and garlic smeared on them.” Obviously, the crown jewel of the Superbar was the Mexican Fiesta, with its “vats of ground beef, nacho cheese, sour cream.” The Fiesta shared custody of additional toppings with the salad bar. It was $2.99 for the dining experience.

Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny. The McDonald’s Breakfast Buffet.

The marriage of Wendy’s and the Superbar lasted about a decade before it was phased out in all locations by 1998. Like a jilted ex-lover, the official Wendy’s Story on the website makes zero mention of Superbar, despite the countless blogs, YouTube videos, and podcasts devoted to remembering it. At least they kept the salad bar together until the mid-2000s for the sake of the children.

Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny. The McDonald’s Breakfast Buffet. Googling the existence of such a thing only returns results of people questioning the existence of this McMuffin Mecca on subforums and Reddit. Somebody knows somebody who passed one once on the highway. A stray Yelp review of the Kiss My Grits food truck in Seattle offers a lead: “I have to say, I recall the first time I ever saw grits, they were at a McDonald’s breakfast buffet in Alexandria, Virginia, and they looked as unappetizing as could be.” However, the lead is dead on arrival. Further googling of the McDonald’s buffet with terrible grits in Alexandria turns up nothing.

I ask friends on Facebook. I ask Twitter. I get a lone response. Eden Robins messages me “It was in Decatur, IL,” as though she’s describing the site where aliens abducted her. “I’m a little relieved that I didn’t imagine the breakfast buffet since no one ever knows what the fuck I’m talking about when I bring it up.”

“We had traveled down there for a high school drama competition,” she goes on to say. “And one morning before the competition, we ate at a McDonald’s breakfast buffet. I had never seen anything like it before or since.”

I ask what was in the buffet, although I know the details alone will not sustain me. I want video to pore over so I can pause at specific frames, like a fast-food version of the Patterson–Gimlin Bigfoot footage. Robins says they served “scrambled eggs and pancakes and those hash brown tiles. I was a vegetarian at the time so no sausage or bacon, but those were there, too.”

McDonald’s isn’t the only chain with a buffet whose existence is hazy. Yum Brands, the overlord of fast-food holy trinity Taco Bell, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Pizza Hut, is said to have had buffets at all three restaurants. I confirm nothing, however, when I reach out to the corporate authorities. On the KFC side, a spokesperson offers to look into “some historical information,” but doesn’t get back to me. My contact at Taco Bell tells me, “I’ll look into it. Certainly, nothing in existence today. I’ve never heard of it. Looks like there are a couple threads on Reddit.”

Reddit, of course, speculates a possible Mandela Effect — the phenomenon of a group of unrelated people remembering a different event than what actually occurred — in the existence of Taco Bell buffets. But I have a firmer lead in Payel Patel, a doctor who studied at Johns Hopkins, who tells me there was a Taco Bell Express in her dorm that was included in an all-you-can-eat meal plan option, though it only lasted one fleeting year. “You could order anything, like 15 nachos and 11 bean burritos,” she says, “and they would make it and give it to you, and you walked off without paying a cent.” A Johns Hopkins student newsletter published in 2001 corroborates the existence of the utopian all-you-can-eat Taco Bell, saying, “you can also gorge yourself on some good old Taco Bell tacos and burritos. Don’t forget, it’s all-you-can-eat. Just don’t eat too much; you don’t want to overload the John.”

There are some concrete examples of fast-food buffets that still exist today. When a Krystal Buffet opened in Alabama in 2019, it was met with “excitement and disbelief,” according to the press release. Former New Orleans resident Wilson Koewing told me of a Popeye’s buffet that locals “speak of as if it is a myth.” When I dig deeper, I come across a local paper, NOLA Weekend, which covers “New Orleans Food, things to do, culture, and lifestyle.” It touts the Popeye’s buffet like a carnival barker, as though it is simply too incredible to believe: “The Only Popeye’s Buffet in the World! It’s right next door in Lafayette! Yes, that’s right: a Popeyes buffet. HERE.”

Somehow, the KFC buffet is the most enduring of the fast-food buffets still in existence. And yet everyone I speak with feels compelled to walk me through the paths and roads leading to such an oasis, as if, again, it were the stuff of legends. There are landmarks and there are mirages, and the mirages need maps most of all.

To get to the KFC buffet in Key Largo, Tiffany Aleman must first take us through “a small island town with one traffic light and one major highway that runs through it. There are the seafood buffets and bait shops, which give way to newfangled Starbucks.”

The buffet adds the feel of a hospital cafeteria, the people dining look close to death or knowingly waiting to die.

New Jerseyan D.F. Jester leads us past the local seafood place “that looks like the midnight buffet on a cruise ship has been transported 50 miles inland and plunked inside the dining area of a 1980s Ramada outside of Newark.”

Descriptions of the food are about what I would expect of a KFC buffet. Laura Camerer remembers the food in her college town in Morehead, Kentucky, as “all fried solid as rocks sitting under heat lamps, kind of gray and gristly.” Jester adds, “for all intents and purposes, this is a KFC. It looks like one, but sadder, more clinical. The buffet adds the feel of a hospital cafeteria, the people dining look close to death or knowingly waiting to die.”

Then Jessie Lovett Allen messages me. “There is [a] KFC in my hometown, and it is magical without a hint of sketch.” I must know more. First, she takes me down the winding path: “the closest larger city is Kearney, which is 100 miles away and only has 35K people, and Kearney is where you’ll find the closest Target, Panera, or Taco Bell. But to the North, South, or West, you have to drive hundreds of miles before you find a larger city. I tell you all of this because the extreme isolation is what gives our restaurants, even fast-food ones, an outsized psychological importance to daily life.”

The KFC Jessie mentions is in North Platte, Nebraska, and has nearly five stars on Yelp, an accomplishment worthy of a monument for any fast-food restaurant. On the non-corporate Facebook page for KFC North Platte, one of the hundreds of followers of the page comments, “BEST KFC IN THE COUNTRY.”

Allen describes the place as though she is recounting a corner of heaven. “They have fried apple pies that seem to come through a wormhole from a 1987 McDonalds. Pudding: Hot. Good. Layered cold pudding desserts. This one rotates. It might be chocolate, banana, cookies and cream. It has a graham cracker base, pudding, and whipped topping. Standard Cold Salad bar: Lettuce, salad veggies, macaroni salads, JELL-O salads. Other meats: chicken fried steak patties. Fried chicken gizzards. White Gravy, Chicken Noodle Casserole, Green Bean Casserole, Cornbread, Corn on the Cob, Chicken Pot Pie Casserole. AND most all the standard stuff on the normal KFC menu, which is nice because you can pick out a variety of chicken types or just have a few tablespoons of a side dish.”

In the end, the all-you-can-eat dream didn’t last, if it ever even existed.

Then she adds that the buffet “is also available TO GO, but there are rules. You get a large Styrofoam clamshell, a small Styrofoam clamshell, and a cup. You have to be able to close the Styrofoam. You are instructed that only beverages can go in cups, and when I asked about this, an employee tells me that customers have tried to shove chicken into the drink cups in the past.”

In the end, the all-you-can-eat dream didn’t last, if it ever even existed. The chains folded. The senior citizens keeping Ponderosa in business have died. My own parents reversed course after their buffet bender, trading in sundae stations for cans of SlimFast. Fast-food buffets retreated into an ethereal space. McDonald’s grew up with adult sandwiches like the Arch Deluxe. Wendy’s went on a wild rebound with the Baconator. Pizza Hut ripped out its jukeboxes, changed its logo, went off to the fast-food wars, and ain’t been the same since. Taco Bell is undergoing some kind of midlife crisis, hemorrhaging its entire menu of potatoes, among other beloved items. At least the KFC in North Platte has done good, though the novel coronavirus could change things.

In the age of COVID-19, the fast-food buffet feels like more of a dream than ever. How positively whimsical it would be to stand shoulder to shoulder, hovering over sneeze guards, sharing soup ladles to scoop an odd assortment of pudding, three grapes, a heap of rotini pasta, and a drumstick onto a plate. Maybe we can reach this place again. But to find it, we must follow the landmarks, searching our memory as the map.

MM Carrigan is a Baltimore-area writer and weirdo who enjoys staring directly into the sun. Their work has appeared in Lit Hub, The Rumpus, and PopMatters. They are the editor of Taco Bell Quarterly. Tweets @thesurfingpizza.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/33e4Z8k

https://ift.tt/30jEUmf

A McDonald’s breakfast buffet. An all-you-can-eat Taco Bell. This isn’t the stuff dreams are made of, but a real yet short-lived phenomenon.

When we think of buffets, we tend to think of their 1980s and early ’90s heyday, when commercial jingles for Sizzler might have been confused with our national anthem. We think of Homer Simpson getting dragged out of the Frying Dutchman, “a beast more stomach than man.” I think of my parents going on buffet benders resembling something out of Hunter S. Thompson’s life, determined to get their money’s worth with two picky kids.

What we don’t typically think about, however, is the fast-food buffet, a blip so small on America’s food radar that it’s hard to prove it even existed. But it did. People swear that all-you-can-eat buffets could be found at Taco Bell, KFC, and even under the golden arches of McDonald’s.

That it could have existed isn’t surprising. The fast-food buffet was inevitable, the culmination of an arms race in maximizing caloric intake. It was the physical manifestation of the American id: endless biscuits, popcorn chicken, vats of nacho cheese and sketchy pudding — so much sketchy pudding. Why, then, have so many of us failed to remember it? How did it become a footnote, relegated to the backwoods of myths and legends? There are whispers of McDonald’s locations that have breakfast buffets. Was there, in fact, a Taco Bell buffet, or is it a figment of our collective imaginations? Yes, someone tells me — an all-you-can-eat Taco Bell existed in her dorm cafeteria. Another person suggests maybe we were just remembering the nachos section of the Wendy’s Superbar.

The fast-food buffet was inevitable, the culmination of an arms race in maximizing caloric intake.

The fast-food buffet lives in a strange sort of ether. You can’t get to it through the traditional path of remembering. Was there actually a Pizza Hut buffet in your hometown? Search your subconscious, sifting past the red cups that make the soda taste better, past the spiffy new CD jukebox, which has Garth Brooks’s Ropin’ the Wind and Paul McCartney’s All the Best under the neon lamps. Search deeper, and you might find your father going up for a third plate and something remaining of the “dessert pizzas” lodged in your subconscious. This is where the fast-food buffet exists.

The history of the buffet in America is a story of ingenuity and evolution. Sure, it originated in Europe, where it was a classy affair with artfully arranged salted fish, eggs, breads, and butter. The Swedish dazzled us with their smorgasbords at the 1939 World Fair. We can then trace the evolution of the buffet through Las Vegas, where the one-dollar Buckaroo Buffet kept gamblers in the casino. In the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese immigrant families found loopholes in racist immigration laws by establishing restaurants. They brought Chinese cooking catered to American tastes in endless plates of beef chow fun and egg rolls. By the 1980s, buffets ruled the landscape like family dynasties, with sister chains the Ponderosa and the Bonanza spreading the gospel of sneeze guards and steaks, sundae stations and salad bars along the interstates. From Shoney’s to Sizzler, from sea to shining sea, the buffet was a feast fit for kings, or a family of four.

And of course, fast-food restaurants wanted in on the action. As fast-food historian and author of Drive-Thru Dreams Adam Chandler put it, “every fast food place flirted with buffets at some point or another. McDonald’s absolutely did, as did most of the pizza chains with dine-in service. KFC still has a few stray buffets, as well as an illicit one called Claudia Sanders Dinner House, which was opened by Colonel Sanders’ wife after he was forbidden from opening a competing fried chicken business after selling the company. Wendy’s Super Bar was short-lived, but the salad bar lived on for decades.”

How something can be both gross and glorious is a particular duality of fast food, like the duality of man or something, only with nacho cheese and pasta sauce.

In a 1988 commercial for the Superbar, Dave Thomas says, “I’m an old-fashioned guy. I like it when families eat together.” A Wendy’s executive described the new business model as “taking us out of the fast-food business.” Everyone agrees the Wendy’s Supernar was glorious. And gross, everyone also agrees. How something can be both gross and glorious is a particular duality of fast food, like the duality of man or something, only with nacho cheese and pasta sauce.

“I kind of want to live in a ’90s Wendy’s,” Amy Barnes, a Tennessee-based writer, tells me in between preparing for virtual learning with her teenagers. The Superbar sat in the lobby, with stations lined up like train carts. First, there was the Garden Spot, which “no one cared about,” a traditional salad bar with a tub of chocolate pudding at its helm, “which always had streams of salad dressing and shredded cheese floating on top.” Next up was the Pasta Pasta section, with “noodles, alfredo and tomato sauce…[as well as] garlic bread made from the repurposed hamburger buns with butter and garlic smeared on them.” Obviously, the crown jewel of the Superbar was the Mexican Fiesta, with its “vats of ground beef, nacho cheese, sour cream.” The Fiesta shared custody of additional toppings with the salad bar. It was $2.99 for the dining experience.

Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny. The McDonald’s Breakfast Buffet.

The marriage of Wendy’s and the Superbar lasted about a decade before it was phased out in all locations by 1998. Like a jilted ex-lover, the official Wendy’s Story on the website makes zero mention of Superbar, despite the countless blogs, YouTube videos, and podcasts devoted to remembering it. At least they kept the salad bar together until the mid-2000s for the sake of the children.

Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny. The McDonald’s Breakfast Buffet. Googling the existence of such a thing only returns results of people questioning the existence of this McMuffin Mecca on subforums and Reddit. Somebody knows somebody who passed one once on the highway. A stray Yelp review of the Kiss My Grits food truck in Seattle offers a lead: “I have to say, I recall the first time I ever saw grits, they were at a McDonald’s breakfast buffet in Alexandria, Virginia, and they looked as unappetizing as could be.” However, the lead is dead on arrival. Further googling of the McDonald’s buffet with terrible grits in Alexandria turns up nothing.

I ask friends on Facebook. I ask Twitter. I get a lone response. Eden Robins messages me “It was in Decatur, IL,” as though she’s describing the site where aliens abducted her. “I’m a little relieved that I didn’t imagine the breakfast buffet since no one ever knows what the fuck I’m talking about when I bring it up.”

“We had traveled down there for a high school drama competition,” she goes on to say. “And one morning before the competition, we ate at a McDonald’s breakfast buffet. I had never seen anything like it before or since.”

I ask what was in the buffet, although I know the details alone will not sustain me. I want video to pore over so I can pause at specific frames, like a fast-food version of the Patterson–Gimlin Bigfoot footage. Robins says they served “scrambled eggs and pancakes and those hash brown tiles. I was a vegetarian at the time so no sausage or bacon, but those were there, too.”

McDonald’s isn’t the only chain with a buffet whose existence is hazy. Yum Brands, the overlord of fast-food holy trinity Taco Bell, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Pizza Hut, is said to have had buffets at all three restaurants. I confirm nothing, however, when I reach out to the corporate authorities. On the KFC side, a spokesperson offers to look into “some historical information,” but doesn’t get back to me. My contact at Taco Bell tells me, “I’ll look into it. Certainly, nothing in existence today. I’ve never heard of it. Looks like there are a couple threads on Reddit.”

Reddit, of course, speculates a possible Mandela Effect — the phenomenon of a group of unrelated people remembering a different event than what actually occurred — in the existence of Taco Bell buffets. But I have a firmer lead in Payel Patel, a doctor who studied at Johns Hopkins, who tells me there was a Taco Bell Express in her dorm that was included in an all-you-can-eat meal plan option, though it only lasted one fleeting year. “You could order anything, like 15 nachos and 11 bean burritos,” she says, “and they would make it and give it to you, and you walked off without paying a cent.” A Johns Hopkins student newsletter published in 2001 corroborates the existence of the utopian all-you-can-eat Taco Bell, saying, “you can also gorge yourself on some good old Taco Bell tacos and burritos. Don’t forget, it’s all-you-can-eat. Just don’t eat too much; you don’t want to overload the John.”

There are some concrete examples of fast-food buffets that still exist today. When a Krystal Buffet opened in Alabama in 2019, it was met with “excitement and disbelief,” according to the press release. Former New Orleans resident Wilson Koewing told me of a Popeye’s buffet that locals “speak of as if it is a myth.” When I dig deeper, I come across a local paper, NOLA Weekend, which covers “New Orleans Food, things to do, culture, and lifestyle.” It touts the Popeye’s buffet like a carnival barker, as though it is simply too incredible to believe: “The Only Popeye’s Buffet in the World! It’s right next door in Lafayette! Yes, that’s right: a Popeyes buffet. HERE.”

Somehow, the KFC buffet is the most enduring of the fast-food buffets still in existence. And yet everyone I speak with feels compelled to walk me through the paths and roads leading to such an oasis, as if, again, it were the stuff of legends. There are landmarks and there are mirages, and the mirages need maps most of all.

To get to the KFC buffet in Key Largo, Tiffany Aleman must first take us through “a small island town with one traffic light and one major highway that runs through it. There are the seafood buffets and bait shops, which give way to newfangled Starbucks.”

The buffet adds the feel of a hospital cafeteria, the people dining look close to death or knowingly waiting to die.

New Jerseyan D.F. Jester leads us past the local seafood place “that looks like the midnight buffet on a cruise ship has been transported 50 miles inland and plunked inside the dining area of a 1980s Ramada outside of Newark.”

Descriptions of the food are about what I would expect of a KFC buffet. Laura Camerer remembers the food in her college town in Morehead, Kentucky, as “all fried solid as rocks sitting under heat lamps, kind of gray and gristly.” Jester adds, “for all intents and purposes, this is a KFC. It looks like one, but sadder, more clinical. The buffet adds the feel of a hospital cafeteria, the people dining look close to death or knowingly waiting to die.”

Then Jessie Lovett Allen messages me. “There is [a] KFC in my hometown, and it is magical without a hint of sketch.” I must know more. First, she takes me down the winding path: “the closest larger city is Kearney, which is 100 miles away and only has 35K people, and Kearney is where you’ll find the closest Target, Panera, or Taco Bell. But to the North, South, or West, you have to drive hundreds of miles before you find a larger city. I tell you all of this because the extreme isolation is what gives our restaurants, even fast-food ones, an outsized psychological importance to daily life.”

The KFC Jessie mentions is in North Platte, Nebraska, and has nearly five stars on Yelp, an accomplishment worthy of a monument for any fast-food restaurant. On the non-corporate Facebook page for KFC North Platte, one of the hundreds of followers of the page comments, “BEST KFC IN THE COUNTRY.”

Allen describes the place as though she is recounting a corner of heaven. “They have fried apple pies that seem to come through a wormhole from a 1987 McDonalds. Pudding: Hot. Good. Layered cold pudding desserts. This one rotates. It might be chocolate, banana, cookies and cream. It has a graham cracker base, pudding, and whipped topping. Standard Cold Salad bar: Lettuce, salad veggies, macaroni salads, JELL-O salads. Other meats: chicken fried steak patties. Fried chicken gizzards. White Gravy, Chicken Noodle Casserole, Green Bean Casserole, Cornbread, Corn on the Cob, Chicken Pot Pie Casserole. AND most all the standard stuff on the normal KFC menu, which is nice because you can pick out a variety of chicken types or just have a few tablespoons of a side dish.”

In the end, the all-you-can-eat dream didn’t last, if it ever even existed.

Then she adds that the buffet “is also available TO GO, but there are rules. You get a large Styrofoam clamshell, a small Styrofoam clamshell, and a cup. You have to be able to close the Styrofoam. You are instructed that only beverages can go in cups, and when I asked about this, an employee tells me that customers have tried to shove chicken into the drink cups in the past.”

In the end, the all-you-can-eat dream didn’t last, if it ever even existed. The chains folded. The senior citizens keeping Ponderosa in business have died. My own parents reversed course after their buffet bender, trading in sundae stations for cans of SlimFast. Fast-food buffets retreated into an ethereal space. McDonald’s grew up with adult sandwiches like the Arch Deluxe. Wendy’s went on a wild rebound with the Baconator. Pizza Hut ripped out its jukeboxes, changed its logo, went off to the fast-food wars, and ain’t been the same since. Taco Bell is undergoing some kind of midlife crisis, hemorrhaging its entire menu of potatoes, among other beloved items. At least the KFC in North Platte has done good, though the novel coronavirus could change things.

In the age of COVID-19, the fast-food buffet feels like more of a dream than ever. How positively whimsical it would be to stand shoulder to shoulder, hovering over sneeze guards, sharing soup ladles to scoop an odd assortment of pudding, three grapes, a heap of rotini pasta, and a drumstick onto a plate. Maybe we can reach this place again. But to find it, we must follow the landmarks, searching our memory as the map.

MM Carrigan is a Baltimore-area writer and weirdo who enjoys staring directly into the sun. Their work has appeared in Lit Hub, The Rumpus, and PopMatters. They are the editor of Taco Bell Quarterly. Tweets @thesurfingpizza.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/33e4Z8k

via Blogger https://ift.tt/36lO2KT

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

Woke kids up and got them ready to school

Drove Abe to school

Called the Alderman

Called the bank

Called Six Flags five times to inquire about Miles’s phone

Drove to Six Flags to get his phone

Drove to Evanston to pick up my old saxophone

Started this blog

Picked up Abe from school

Today I woke Miles up at 6.10 am for his first day of school, went back to sleep, woke back up, helped him get ready, including putting together his school supplies (e.g., slicing open the packages of college-ruled looseleaf paper and 5-tab divider sets and doling them out equally between four binders) that he hadn’t done yet despite their being in his room for the last two weeks and despite him not having done that last night when I reminded him and he said I’ll do it in the morning, even though there was getting dressed, tooth brushing, contact lens insertion, hair styling, breakfast eating and lunch making all scheduled for the morning.

I did not participate in his breakfast or lunch, but did retrieve his backpack from the basement, where it was in the dryer because Laura washed it out last night after I’d forgotten (and forgotten earlier that I’d put it in the basement sink last week because for some reason Miles had peppers in his bag that rotted and oozed all over the fabric, which also said in those European laundry symbols that are not immediately apparent do not wash, dry or iron) to do that myself even though I promised to when Laura was up half the night finishing her work for today and I was cleaning up the kitchen and putting the kids to bed (and Miles doing his homework, and obsessing about his phone and then arguing about putting together his school supplies), and then I just was deleting email on my computer (or maybe reading the New York Times) until I was over-exhausted and got into bed, where Laura woke me later to ask something about this morning which I don’t remember now. (I also woke up at 2.47 am because I heard the bathroom door creak so maybe some kid got up to go to the bathroom).

Miles and Laura left at 8 am (five minutes late because I was running around getting Miles a ruler, and graph paper, and post-it notes and highlighters to add to the binders I had already made) and I went upstairs to where Abraham’s radio alarm was blasting at maximum volume. He wanted to stay in bed and have a kiss and hug from me, but I asked him to get up. He came into my office in his underwear and pretended to fall down limp as I hugged him. “I’m so tired,” he said.

“Why don’t you go get dressed and brush your teeth and then let’s go downstairs to make breakfast and your lunch. We have to leave in 45 minutes.”

“Ok, dad.” First day excitement, not to be repeated.

He said since it’s the first day of school, can I have Dutch baby? But instead I made him bacon and scrambled eggs (I burned the bacon! Who does that?) and he made himself a ham (complained that Grandpa didn’t buy summer sausage because he apparently thought ham and turkey were fine), cheddar cheese and lettuce sandwich on a pretzel bun (no mayo because of the cheese), grapes, pretzels (complained that Grandpa didn’t buy pretzels because he apparently thought corn chips were a good substitute), two granola bars (best ever because they’re covered in caramel), watermelon, and a pack of seaweed snacks.

When we were ready to go, I opened the cabinet to get my keys and remembered that I didn’t have a car key because over the weekend, my inlaws Bill and Suzan had borrowed our car while they were taking care of the children because we were at Lara and Bobby’s wedding in Becket, Massachusetts, and they had lost (misplaced) the key. So I had to call Laura who had already been at work for 45 minutes because it was also HER first day of school and ask her to drive home to give me the key.

Abraham and I waited outside for Laura to arrive, chatted with Robert across the street and said hi to Leo and Jean. Laura dropped off the key and noted that we were going to be late. We got in the car and I plugged in Waze to see how long it would take-- it said we would arrive 3 minutes after the latest time we could arrive, at which point parents and kids are asked to wait outside for 15 minutes until Morning Meeting is over. Luckily, they were flexible on the first day and even though Morning Meeting was going as we arrived and Abe changed into his school shoes from his street shoes, we were allowed in.

On the way home, I called the Alderman to tell him about our lease and ask him to be on alert, ready to help and also ask about contacting planning and development. Then I called the bank but had to leave a message. When I got home, I had received an email from Six Flags saying they found Miles’s phone which he lost on his very first ride on Sunday when my inlaws took him and Abe to Great America. But Miles proved to be a sleuthing and persistent follow uper and managed to connect with Deborah at Lost and Found, and they found his phone. But I called and called and nobody answered and I didn’t want to drive an hour out to Six Flags if I couldn’t get the phone (I knew from the website that the park was closed today). I finally got hold of someone at about 11 and they said that I couldn’t come until September 16, but I asked if I could talk to someone else and then she said one of her co-workers was saying something to her, and she patched me into Security, who said they had the phone and I could come and get it.

I packed chips and mozarella cheese and grapes for the two hour ride and drove to Gurnee, Illinois, right under the wooden Goliath coaster in the employee parking lot and rolled up to the Security booth, where Keith was working and I said I was picking up a phone my son had lost, and he said is his name Miles? and he had his iPhone right there in the booth, making me realize that Miles getting his phone back was kind of a big deal because Deborah had told me last night that there were ten bags of stuff turned in, and yet this was just sitting waiting for me in the Security booth as if there were not a lot of people driving out today.

Then I drove back and went to Evanston where almost two years ago (for real), I had dropped off my Bundy alto saxophone (which had been a rental in 4th grade from Alto Music in Suffern and which at some point my parents had paid for, and I still have it) which I had brought in to get new pads and a tune up of sorts. They charged me $600, which was more than the sax is worth and more than they had quoted me, which was between $400 and $500. The guy behind the counter, Eli, who also had cool tattoos and gave me the name of his tattoo artist, called the repair person who said that $600 was too high and to do it for $500. Eli threw in a strap and a box of reeds, which was probably worth about $50. So.

Then I went home and started this blog. (What do you think? Isn’t it pretty? I just wanted a place to post about daily life so I picked their standard). Went to pick up Abraham. Waited outside with Doug and Andrea and we talked about my mom’s death, death with dignity in general, and carpools. Got Abe, negotiated ice cream as first day of school treat, drove home. Waited for Miles, worked on this post.

Then we went out to George’s for ice cream, missed the afterschool back to school special, spent $9 and won four games of Connect Four in a row against the kids, went to Blaze for dinner, and now Abe’s in the shower. I’m missing band tonight because Laura has to work and it didn’t feel right to leave the kids alone.

That’s a day.

0 notes

Quote

A McDonald’s breakfast buffet. An all-you-can-eat Taco Bell. This isn’t the stuff dreams are made of, but a real yet short-lived phenomenon.

When we think of buffets, we tend to think of their 1980s and early ’90s heyday, when commercial jingles for Sizzler might have been confused with our national anthem. We think of Homer Simpson getting dragged out of the Frying Dutchman, “a beast more stomach than man.” I think of my parents going on buffet benders resembling something out of Hunter S. Thompson’s life, determined to get their money’s worth with two picky kids.

What we don’t typically think about, however, is the fast-food buffet, a blip so small on America’s food radar that it’s hard to prove it even existed. But it did. People swear that all-you-can-eat buffets could be found at Taco Bell, KFC, and even under the golden arches of McDonald’s.

That it could have existed isn’t surprising. The fast-food buffet was inevitable, the culmination of an arms race in maximizing caloric intake. It was the physical manifestation of the American id: endless biscuits, popcorn chicken, vats of nacho cheese and sketchy pudding — so much sketchy pudding. Why, then, have so many of us failed to remember it? How did it become a footnote, relegated to the backwoods of myths and legends? There are whispers of McDonald’s locations that have breakfast buffets. Was there, in fact, a Taco Bell buffet, or is it a figment of our collective imaginations? Yes, someone tells me — an all-you-can-eat Taco Bell existed in her dorm cafeteria. Another person suggests maybe we were just remembering the nachos section of the Wendy’s Superbar.

The fast-food buffet was inevitable, the culmination of an arms race in maximizing caloric intake.

The fast-food buffet lives in a strange sort of ether. You can’t get to it through the traditional path of remembering. Was there actually a Pizza Hut buffet in your hometown? Search your subconscious, sifting past the red cups that make the soda taste better, past the spiffy new CD jukebox, which has Garth Brooks’s Ropin’ the Wind and Paul McCartney’s All the Best under the neon lamps. Search deeper, and you might find your father going up for a third plate and something remaining of the “dessert pizzas” lodged in your subconscious. This is where the fast-food buffet exists.

The history of the buffet in America is a story of ingenuity and evolution. Sure, it originated in Europe, where it was a classy affair with artfully arranged salted fish, eggs, breads, and butter. The Swedish dazzled us with their smorgasbords at the 1939 World Fair. We can then trace the evolution of the buffet through Las Vegas, where the one-dollar Buckaroo Buffet kept gamblers in the casino. In the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese immigrant families found loopholes in racist immigration laws by establishing restaurants. They brought Chinese cooking catered to American tastes in endless plates of beef chow fun and egg rolls. By the 1980s, buffets ruled the landscape like family dynasties, with sister chains the Ponderosa and the Bonanza spreading the gospel of sneeze guards and steaks, sundae stations and salad bars along the interstates. From Shoney’s to Sizzler, from sea to shining sea, the buffet was a feast fit for kings, or a family of four.

And of course, fast-food restaurants wanted in on the action. As fast-food historian and author of Drive-Thru Dreams Adam Chandler put it, “every fast food place flirted with buffets at some point or another. McDonald’s absolutely did, as did most of the pizza chains with dine-in service. KFC still has a few stray buffets, as well as an illicit one called Claudia Sanders Dinner House, which was opened by Colonel Sanders’ wife after he was forbidden from opening a competing fried chicken business after selling the company. Wendy’s Super Bar was short-lived, but the salad bar lived on for decades.”

How something can be both gross and glorious is a particular duality of fast food, like the duality of man or something, only with nacho cheese and pasta sauce.

In a 1988 commercial for the Superbar, Dave Thomas says, “I’m an old-fashioned guy. I like it when families eat together.” A Wendy’s executive described the new business model as “taking us out of the fast-food business.” Everyone agrees the Wendy’s Supernar was glorious. And gross, everyone also agrees. How something can be both gross and glorious is a particular duality of fast food, like the duality of man or something, only with nacho cheese and pasta sauce.

“I kind of want to live in a ’90s Wendy’s,” Amy Barnes, a Tennessee-based writer, tells me in between preparing for virtual learning with her teenagers. The Superbar sat in the lobby, with stations lined up like train carts. First, there was the Garden Spot, which “no one cared about,” a traditional salad bar with a tub of chocolate pudding at its helm, “which always had streams of salad dressing and shredded cheese floating on top.” Next up was the Pasta Pasta section, with “noodles, alfredo and tomato sauce…[as well as] garlic bread made from the repurposed hamburger buns with butter and garlic smeared on them.” Obviously, the crown jewel of the Superbar was the Mexican Fiesta, with its “vats of ground beef, nacho cheese, sour cream.” The Fiesta shared custody of additional toppings with the salad bar. It was $2.99 for the dining experience.

Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny. The McDonald’s Breakfast Buffet.

The marriage of Wendy’s and the Superbar lasted about a decade before it was phased out in all locations by 1998. Like a jilted ex-lover, the official Wendy’s Story on the website makes zero mention of Superbar, despite the countless blogs, YouTube videos, and podcasts devoted to remembering it. At least they kept the salad bar together until the mid-2000s for the sake of the children.

Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny. The McDonald’s Breakfast Buffet. Googling the existence of such a thing only returns results of people questioning the existence of this McMuffin Mecca on subforums and Reddit. Somebody knows somebody who passed one once on the highway. A stray Yelp review of the Kiss My Grits food truck in Seattle offers a lead: “I have to say, I recall the first time I ever saw grits, they were at a McDonald’s breakfast buffet in Alexandria, Virginia, and they looked as unappetizing as could be.” However, the lead is dead on arrival. Further googling of the McDonald’s buffet with terrible grits in Alexandria turns up nothing.

I ask friends on Facebook. I ask Twitter. I get a lone response. Eden Robins messages me “It was in Decatur, IL,” as though she’s describing the site where aliens abducted her. “I’m a little relieved that I didn’t imagine the breakfast buffet since no one ever knows what the fuck I’m talking about when I bring it up.”

“We had traveled down there for a high school drama competition,” she goes on to say. “And one morning before the competition, we ate at a McDonald’s breakfast buffet. I had never seen anything like it before or since.”

I ask what was in the buffet, although I know the details alone will not sustain me. I want video to pore over so I can pause at specific frames, like a fast-food version of the Patterson–Gimlin Bigfoot footage. Robins says they served “scrambled eggs and pancakes and those hash brown tiles. I was a vegetarian at the time so no sausage or bacon, but those were there, too.”

McDonald’s isn’t the only chain with a buffet whose existence is hazy. Yum Brands, the overlord of fast-food holy trinity Taco Bell, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Pizza Hut, is said to have had buffets at all three restaurants. I confirm nothing, however, when I reach out to the corporate authorities. On the KFC side, a spokesperson offers to look into “some historical information,” but doesn’t get back to me. My contact at Taco Bell tells me, “I’ll look into it. Certainly, nothing in existence today. I’ve never heard of it. Looks like there are a couple threads on Reddit.”

Reddit, of course, speculates a possible Mandela Effect — the phenomenon of a group of unrelated people remembering a different event than what actually occurred — in the existence of Taco Bell buffets. But I have a firmer lead in Payel Patel, a doctor who studied at Johns Hopkins, who tells me there was a Taco Bell Express in her dorm that was included in an all-you-can-eat meal plan option, though it only lasted one fleeting year. “You could order anything, like 15 nachos and 11 bean burritos,” she says, “and they would make it and give it to you, and you walked off without paying a cent.” A Johns Hopkins student newsletter published in 2001 corroborates the existence of the utopian all-you-can-eat Taco Bell, saying, “you can also gorge yourself on some good old Taco Bell tacos and burritos. Don’t forget, it’s all-you-can-eat. Just don’t eat too much; you don’t want to overload the John.”

There are some concrete examples of fast-food buffets that still exist today. When a Krystal Buffet opened in Alabama in 2019, it was met with “excitement and disbelief,” according to the press release. Former New Orleans resident Wilson Koewing told me of a Popeye’s buffet that locals “speak of as if it is a myth.” When I dig deeper, I come across a local paper, NOLA Weekend, which covers “New Orleans Food, things to do, culture, and lifestyle.” It touts the Popeye’s buffet like a carnival barker, as though it is simply too incredible to believe: “The Only Popeye’s Buffet in the World! It’s right next door in Lafayette! Yes, that’s right: a Popeyes buffet. HERE.”

Somehow, the KFC buffet is the most enduring of the fast-food buffets still in existence. And yet everyone I speak with feels compelled to walk me through the paths and roads leading to such an oasis, as if, again, it were the stuff of legends. There are landmarks and there are mirages, and the mirages need maps most of all.

To get to the KFC buffet in Key Largo, Tiffany Aleman must first take us through “a small island town with one traffic light and one major highway that runs through it. There are the seafood buffets and bait shops, which give way to newfangled Starbucks.”

The buffet adds the feel of a hospital cafeteria, the people dining look close to death or knowingly waiting to die.

New Jerseyan D.F. Jester leads us past the local seafood place “that looks like the midnight buffet on a cruise ship has been transported 50 miles inland and plunked inside the dining area of a 1980s Ramada outside of Newark.”

Descriptions of the food are about what I would expect of a KFC buffet. Laura Camerer remembers the food in her college town in Morehead, Kentucky, as “all fried solid as rocks sitting under heat lamps, kind of gray and gristly.” Jester adds, “for all intents and purposes, this is a KFC. It looks like one, but sadder, more clinical. The buffet adds the feel of a hospital cafeteria, the people dining look close to death or knowingly waiting to die.”

Then Jessie Lovett Allen messages me. “There is [a] KFC in my hometown, and it is magical without a hint of sketch.” I must know more. First, she takes me down the winding path: “the closest larger city is Kearney, which is 100 miles away and only has 35K people, and Kearney is where you’ll find the closest Target, Panera, or Taco Bell. But to the North, South, or West, you have to drive hundreds of miles before you find a larger city. I tell you all of this because the extreme isolation is what gives our restaurants, even fast-food ones, an outsized psychological importance to daily life.”

The KFC Jessie mentions is in North Platte, Nebraska, and has nearly five stars on Yelp, an accomplishment worthy of a monument for any fast-food restaurant. On the non-corporate Facebook page for KFC North Platte, one of the hundreds of followers of the page comments, “BEST KFC IN THE COUNTRY.”

Allen describes the place as though she is recounting a corner of heaven. “They have fried apple pies that seem to come through a wormhole from a 1987 McDonalds. Pudding: Hot. Good. Layered cold pudding desserts. This one rotates. It might be chocolate, banana, cookies and cream. It has a graham cracker base, pudding, and whipped topping. Standard Cold Salad bar: Lettuce, salad veggies, macaroni salads, JELL-O salads. Other meats: chicken fried steak patties. Fried chicken gizzards. White Gravy, Chicken Noodle Casserole, Green Bean Casserole, Cornbread, Corn on the Cob, Chicken Pot Pie Casserole. AND most all the standard stuff on the normal KFC menu, which is nice because you can pick out a variety of chicken types or just have a few tablespoons of a side dish.”

In the end, the all-you-can-eat dream didn’t last, if it ever even existed.

Then she adds that the buffet “is also available TO GO, but there are rules. You get a large Styrofoam clamshell, a small Styrofoam clamshell, and a cup. You have to be able to close the Styrofoam. You are instructed that only beverages can go in cups, and when I asked about this, an employee tells me that customers have tried to shove chicken into the drink cups in the past.”

In the end, the all-you-can-eat dream didn’t last, if it ever even existed. The chains folded. The senior citizens keeping Ponderosa in business have died. My own parents reversed course after their buffet bender, trading in sundae stations for cans of SlimFast. Fast-food buffets retreated into an ethereal space. McDonald’s grew up with adult sandwiches like the Arch Deluxe. Wendy’s went on a wild rebound with the Baconator. Pizza Hut ripped out its jukeboxes, changed its logo, went off to the fast-food wars, and ain’t been the same since. Taco Bell is undergoing some kind of midlife crisis, hemorrhaging its entire menu of potatoes, among other beloved items. At least the KFC in North Platte has done good, though the novel coronavirus could change things.

In the age of COVID-19, the fast-food buffet feels like more of a dream than ever. How positively whimsical it would be to stand shoulder to shoulder, hovering over sneeze guards, sharing soup ladles to scoop an odd assortment of pudding, three grapes, a heap of rotini pasta, and a drumstick onto a plate. Maybe we can reach this place again. But to find it, we must follow the landmarks, searching our memory as the map.

MM Carrigan is a Baltimore-area writer and weirdo who enjoys staring directly into the sun. Their work has appeared in Lit Hub, The Rumpus, and PopMatters. They are the editor of Taco Bell Quarterly. Tweets @thesurfingpizza.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/33e4Z8k

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/09/fast-food-buffets-are-thing-of-past.html

0 notes