#to be specific the last residential school closed in 1996

Text

Teshuvah on the National Level

As anyone who has ever attended a Rosh Hashanah service at Shelter Rock (or anywhere at all) knows, the core principle of the High Holiday season is the notion that, although done deeds cannot be undone (which would be something akin to unringing a bell or unsinging a song), they can be addressed purposefully and meaningfully through the process called t’shuvah in Hebrew and, slightly misleadingly, “repentance” in English. The Hebrew word derives from the verb meaning “to turn” and implies that one not only regrets a past act, but that one has specifically turned away from it and resolved, even should the opportunity present itself to repeat the deed, not to do that specific thing again. So that sounds simple enough, but the laws that govern the process are, to say the least, challenging. If you have wronged another, you have to ask that individual for forgiveness. But even if there is no specific other person from whom to ask forgiveness, you still have to exert yourself to right the wrong for which you are responsible nonetheless, thus addressing your own wrongdoing not merely internally or emotionally but practically and meaningfully. There can’t be too many of us who have actually read all 700+ pages of the Book of Repentance of Rabbi Menachem ben Shlomo Meiri of Perpignan, my favorite thirteenth-century Provençal scholar. But even without having the time or energy to undertake a reading project like that, the underlying principles that govern the process of seeking and attaining t’shuvah are available for all to contemplate in dozens of shorter works, including English-language ones like Louis E. Newman’s excellent 2011 book, Repentance: The Meaning and Practice of Teshuvah. (I read the Meiri’s book as my Elul reading project over the course of four years starting in 2013. Newman’s book will take considerably less time to get through.) But neither author asks the question that I’d like to write about today: can nations do t’shuvah or solely individuals?

I was surprised, but also moved, by the news that the German government has finally agreed to acknowledge that the slaughter of tens of thousands of innocents, including children, undertaken by its armed forces in the country in southwestern Africa now known as Namibia was not just an overblown and unnecessarily harsh military action, but an actual act of genocide. But, just as the Meiri (and countless others) have noted with respect to individuals, the acknowledgement of wrongdoing is nowhere near enough and has to be followed by concrete action. Can an offer of something like $1.3 billion to the victims’ descendants count? I think probably so.

The backstory matters. The big colonial powers in occupied Africa were France, Britain, and Belgium. But the Germans were there as well and, starting in 1884, claimed as German territory four colonies: German East Africa (comprising today’s Burundi, Rwanda, and part of Tanzania), German Cameroon (comprising today’s Cameroon and parts of Nigeria, Chad, Gabon, Congo, and the Central African Republic), Togoland (comprising today’s Togo and part of Ghana), and German South-West Africa (today’s Namibia). All became League of Nations mandates following Germany’s defeat in World War I. But by then the newly-acknowledged genocide was more than a decade in the past.

The basic principle was that Germany itself was overcrowded and in need for room to expand—and how more simply to expand then by seizing other peoples’ countries and unilaterally declaring them part of a new German empire? Of course, the Germans were not alone in this approach to the non-white world. But the problem in German South-West Africa was that the natives were not willing to go along with having their land seized and their native culture obliterated and, as a result, two specific tribes, the Herero and the Nama, rose up in rebellion against their despised foreign overlords. It didn’t end well. Armed German soldiers killed tens of thousands, then pushed survivors into concentration camps where most died of starvation or sickness and in which at least some were subjected to ghoulish medical experiments. (Is this starting to sound at all familiar?) Hundreds of human skulls were shipped back to Germany for further experimentation. Some have been returned. The rest somehow disappeared, but the chances that they were respectfully buried appear to be zero.

No Jewish people can consider this without reference to the Shoah, of course. There are plenty of differences, also of course, between the plight of the Jews of Nazi Europe and the fate of the Herero and Nama in German South-West Africa. But the notion of a nation unleashing its army against civilians with the specific purpose of killing as many as possible is one detail they both have in common. (And, yes, there actually is a verified command by Lothar von Trotha, the German military commander in today’s Namibia, unambiguously instructing his men to kill every Herero tribesperson regardless of whether that individual is armed or constitutes some sort of threat.)

The dead, of course, stay in their graves; nothing can bring them back to life. But the willingness of a nation to confront its past is stirring to me—and I can assure my readers that I am more than aware of the irony in me saying that about Germany, the perpetrator nation per excellence. Our tradition teaches that the gates of t’shuvah are always open. It’s heartening to see a nation take a first step through those gates and begin the process of reconciliation and healing that can surely follow. And what’s happened between Germany and Namibia has echoes in other news I read about this last week too.

Just last week, for example, French president Emmanuel Macron publicly acknowledged his nation’s role in the horrific events in Rwanda in 1994 in the course of which more than 800,000 innocents, mostly belonging to the Tutsi tribe, were slaughtered mercilessly by their fellow countrymen who belonged to the other large tribal group in the country, the Hutu. No one accuses the French of themselves having killed those poor people. Nor was Rwanda part of the French colonial empire in the nineteenth century. (See above; it was part of German East Africa.) But the French cultivated a strong, friendly relationship with the Hutu-led government and failed to step in vigorously in a way that they surely could have averted the slaughter. They were therefore bystanders rather than actual perpetrators—but they were bystanders who could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives had they not chosen to do and say nothing while the killing went on. And it was that specific silence that President Macron was addressing in his remarks last week.

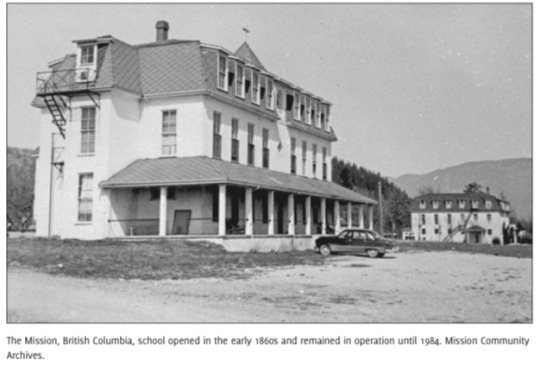

Also last week came the shocking revelation that a mass grave of hundreds of children had been found—not in formerly-Nazi-occupied Europe or in formerly German Africa, but in Canada…and not that far from where Joan and I lived in British Columbia. The remains of 215 children were found on the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, where they had all died of some lethal combination of neglect, disease, and mistreatment. The Kamloops School, just about 200 miles northeast of Vancouver, was part of a large network of schools, mostly operated by various churches including the Roman Catholic Church, that indigenous children were forced to attend by their white overlords. These schools were apparently mini-gulags in all of which some combination of physical violence and brainwashing was brought to bear to make the pupils into “regular” Canadians, which is to say, citizens with no knowledge of or affinity for their own native culture. Nor is this an ancient story for Canadians—the last such school only closed in 1996. Shocked by its own history, the government set up a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission, one based on the similar commission set up in South Africa after the end of apartheid. And the Commission determined that at least 4,100 children died in these schools, almost all of them avoidable deaths, and that the children’s parents were never told anything close to the truth about what had happened to their own sons and daughters. As a father and grandfather, the suffering of those poor people feels incalculable to me. In 2018, Pope Francis declined to issue an apology for the Church’s role in this nightmarish story. But two different Prime Ministers of Canada, Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau, have formally begun the process of national t’shuvah by formally acknowledging their nation’s responsibility in failing to act swiftly and decisively once it was known what these schools were really like. One quote by P.M. Trudeau struck me especially: “For far too many students,” he said, “profound cultural loss led to poverty, family violence, substance abuse and community breakdown. It led to mental and physical health issues that have impeded their happiness and that of their family. Far too many continue to face adversity today as a result of time spent in residential schools, and for that we are sorry.”

Such simple words: “we are sorry.” Yes, easy to wave away as too little, too late. But something, a beginning, a start. When I hear my own countrymen debating the specific ways our nation could or should begin to confront the legacy of slavery in these United States, I find myself looking to the leaders of Germany, France, and Canada, as I wonder what shape that kind of honest engagement with the past could take. And last week I also read with great interest the story about the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria beginning to make after-the-fact payments to the descendants of men and women forced to work there either for no wages at all (i.e., as slaves before the Civil War) or for minimal wages far below what they deserved to earn in the years that followed. Also easy to wave away as a mere gesture. But, it strikes me that we Americans could just as reasonably consider the school’s gesture a beginning, a start, a step forward towards both truth and reconciliation.

#Teshuvah#Meiri#Namibia#Rwanda#Indian Residential Schools#Kamloops#Stephen Harper#Justin Trudeau#Emmanuel Macron

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trigger Warnings: Residential Schools, death, indigenous violence

Recently 215 bodies of indigenous children were found in a mass grave at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. In case you were not aware Residential Schools were a system of schools used to commit cultural and racial genocide against indigenous peoples of Canada. These schools inflicted trauma and death on students. Many never returned from these schools. The 215 children found were undocumented deaths. This means that the families of these 215 children were never able to know what happened to their children as well as to gain closure.

While the Kamloops Indian Residential School, closed in 1969, the last residential school in Canada did not close until 1996. Survivors still struggle with the trauma today. This is not something that can just be labeled as a dark period of Canadian history. Instead it is an ongoing aspect of intolerance and injustice committed in Canada against our indigenous peoples.

Many still continue to suffer from these injustices as well as the trauma from this latest discovery. As I am not a member of the indigenous community I urge others to listen to their voices and concerns. This is something in Canada as the majority, we can no longer push aside and ignore.

National Indian Residential School Crisis Line - 1-866 925-4419

And for those in B.C., KUU-US Crisis Line Society provides a First Nations and Indigenous-specific crisis line available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It's toll-free and can be reached at 1-800-588-8717 or online at kuu-uscrisisline.com.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#4: Residential Schools and Indigenous Homelessness

It is important to discuss the specific trauma that the indigenous in Canada have faced at the hands of their own racist government, “Residential schooling quickly became a central element in the federal government’s Aboriginal policy” (Truth and Reconciliation Canada, 2015, p. 3). Canada wanted the younger generation of the indigenous population to assimilate into the western, Catholic Caucasian way of living. The child welfare system of Canada took indigenous children from their homes and placed them into non-indigenous homes or residential schools. This separation from family and one’s own culture was extremely detrimental to these indigenous children and caused severe long-term psychological issues that left them feeling disconnected and confused about who they were (Menzies, 2009. Canada established residential schools for children as they wanted to change the younger generation so that they would grow up to not be “savages” like their parents and ancestors. The Europeans living in Canada who had control over the indigenous believed that “European civilization and Christian religions were superior to Aboriginal culture” (Truth and Reconciliation Canada, 2015, p. 4). They wanted the indigenous children to adopt their beliefs and culture stripping them of their unique and personal lifestyle.

The treatment that the indigenous children faced in these schools was very abusive as they were manipulated and taken advantage of. In terms of diet and food, the children were, “always hungry; meals were dull, monotonous, and lacking nutrition” (Rose, 2018, p. 350). As children, a nutritious diet is needed to help with positive growth and development so this was a major issue that affected the overall well-being and health of the children. The abuse that these young innocent children faced in these residential schools were very cruel. The most common forms of abuse were physical abuse as they were hit and beaten and sexual abuse (Rose, 2018, p. 350). The residential school staff was able to overpower the children and tended to use these forms of abuse to scare them or teach them a lesson. Sadly, many indigenous children have died at the hands of the Canadian government and residential schools as Zalcman (2016) has identified that “An estimated 6,000 children died while in attendance—sometimes from starvation, physical abuse, or disease, or amid failed attempts to escape” (p.81). So many young lives taken all because their culture was not deemed acceptable. The first residential school opened in 1884 and twenty-two years ago, in 1996 was when the last residential school in Canada closed down (Rose, 2018, p. 350). For over 100 years in Canada, residential schools were running under the authority of the government who wished to abolish a culture. These young indigenous children essentially were without a home as the residential schools were not a safe place to call home. A home was with their family and friends in their indigenous communities not at an institution which suppressed their culture.

Image by (http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Exec_Summary_2015_05_31_web_o.pdf)

0 notes

Text

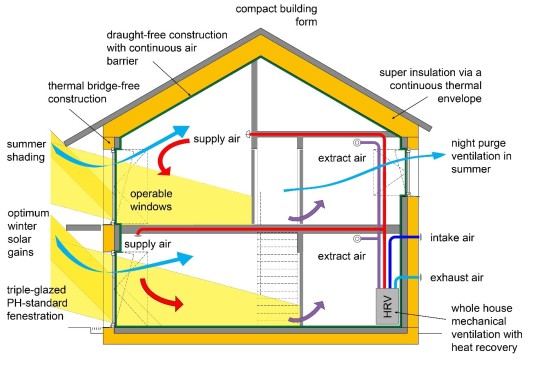

Futurehome – Passivhaus explained

Futurehome is the next step in a journey of innovation and new industry standards as we deliver our exemplar sustainable urban regeneration project, building 3,000 new homes in the heart of zone 1 by 2025. Futurehome is a collection of 15 three and four-bed townhouses, all designed to ‘Passivhaus’ standards - the world's leading ‘fabric first’ approach to low energy buildings. Situated at Elephant Park’s South Gardens, Futurehome offers the ultimate in contemporary sustainable living.

We interviewed Passivhaus expert Mike Roe from WARM Consultants who has been working for Lendlease during the construction of Futurehome and Yogini Patel, Design and Research Associate from The Passivhaus Trust to find out more about the innovative technology which sits behind the design of these homes and the lifestyle and sustainability benefits it will bring to residents.

(Yogini Patel, Design and Research Associate, The Passivhaus Trust)

(Mike Roe, Passivhaus Expert, WARM Consultants)

Where and how did Passivhaus originate?

Mike Roe: “The concept originated in Germany just over 25 years ago by Professors Bo Adamson and Wolfgang Feist. Feist was researching low energy buildings and couldn’t understand why they weren’t performing as well as predicted. Being a physicist, he wanted to get to the bottom of this so he eventually built the first ‘Passivhaus��� home in Darmstadt, Germany and he still lives in it to this very day.”

Yogini Patel: “The Passivhaus Institute was founded in 1996 The first UK Passivhaus, Y Foel Passivhaus, was certified in August 2009 in Powys, Wales. The Passivhaus Trust formed in 2010, and is the UK affiliate of the Passivhaus Institute.”

What is the aim of a Passivhaus home and what makes the concept unique?

Mike Roe: “The aim of a Passivhaus home is to provide low energy housing by focusing on the building fabric. The houses are focused around the actual building form and fabric as opposed to ‘sticking things on’ like renewables such as solar panels. Having a really good foundation and building fabric means that the amount of replacements and ‘quick-fixes’ to things such as solar panels and window panes will be drastically minimised than is the case with other ‘sustainable homes’. What makes them unique is that their predicted energy use is extremely close to the actual outputs so they are proven to work in practise, which is brilliant.”

Yogini Patel: “Passivhaus buildings provide a high level of occupant comfort while using very little energy for heating and cooling. Heat losses are reduced so much (by up to 90%) that you hardly need any heating at all. They are built with meticulous attention-to-detail and undergo a rigorous certification process which guarantees building performance that goes well beyond the requirements of current building regulations.”

(Image courtesy of PassivHaus)

Tell us about a bit more about the specific technological features of the Passivhaus?

Mike Roe: “One main feature of the Passivhaus is the heat recovery ventilation, which Yogini refers to above. This extracts air from the building and supplies fresh air into bedrooms and living rooms. The building is several times more airtight than a traditional building, which means that most of the air that’s coming in and going through the ventilation system is kept in. The recovery of up to 90% of the air that’s been extracted means that the homes are virtually free from pollutants and allergens.

“The other main feature of the Passivhaus is the triple glazed windows and doors. Thermal comfort is a very important issue within Passivhaus and the triple glazing means that the windows and doors are super-efficient in ensuring that the houses lose as little heat as possible and they also have the added benefit of keeping the surface temperatures high so in winter it won’t be cold. The excellent thermal performance and low air infiltration rates of a Passivhaus means that the temperature shouldn’t fall below 16°C, even without heating during the coldest winter months.”

Futurehome at Elephant Park delivers the first Passivhaus new build homes in London’s Zone One

What do these features do for the homeowner?

Mike Roe: “The high-quality filters in ventilation units filter out pollutants and pollen making sure there is fresh air continually circulated throughout the building. The features also prevent overheating which means that they are very efficient in reducing energy bills and carbon footprints. We would expect to heat an entire typical Passivhaus with 1KW of heat – to put that into context, this is approximately the equivalent of using a small hairdryer to heat your entire home.”

Yogini Patel: “Passivhaus homes provide homeowners with comfortable temperatures all year round regardless of the weather. The thick insulation also means you can make as much noise as you like without disturbing the neighbours! Homeowners can also feel reassured in the independent testing that guarantees quality assurance on how your building will perform. If it does not meet the criteria stated above, it is simply not a Passivhaus”

How important do you think a concept like Passivhaus is in the context of sustainable residential development in major cities like London?

Mike Roe: “Passivhaus answers a real need for low energy sustainable housing in the heart of the city and it does so in a sensible way by concentrating on the one thing that lasts the longest – the actual building construction itself. The Passivhaus focuses on the form of the building that’s going to last and won’t have to be replaced – it’s making something very efficient and that will have a legacy. It’s something that people are starting to adopt globally and it’s gaining more support and momentum all the time.”

Yogini Patel: “The political targets for residential development in many major cities such as London are heading towards zero carbon and Passivhaus is a tried and tested solution in helping to achieve these targets. It is proven to work worldwide, in several climates and the amount of energy used is so minimal that the building is shielded from ever increasing fuel bills, which in turn, can provide a solution to combating fuel poverty.”

“Finally, Passivhaus is also beneficial in terms of health and well-being, especially in urban environments. The high quality indoor environment (no draughts, no mould!) is good for occupant health, and the ventilation system removes many pollutants as it filters the air coming in from outside. Passivhaus can therefore help with healthy residential development in London.

“It is important to remember that Passivhaus is not solely for residential schemes. There are several non-domestic schemes at various scales that have been successfully delivered in the UK such as schools and offices, which can provide comfort and energy savings across all sectors.”

Passivhaus homes like Futurhome will provide “comfortable temperatures all year round regardless of the weather”

What do you think is next for sustainable homes?

Mike Roe: “We think that Passivhaus is eventually going to be rolled out on a much larger scale and that in time designing to this standard, will be a mainstream feature of new-build developments that will be made part of building regulations. Passivhaus homes, in comparison to existing buildings, have a reduced heat loss of almost ten-fold. We believe that going forward current buildings are going to be adapted to find ways to retrofit to the same standard. It will be a huge challenge but it’s something that can certainly be done in the future!”

Yogini Patel: “Drastically reducing the energy use in buildings is an effective way of improving our ecological footprint, but it is just the first step. Passivhaus takes us onto the next step of focussing on occupant comfort and health. Coupling Passivhaus with low embodied energy building materials and renewable energy will result in truly net zero energy buildings that are healthy, comfortable and have minimum impact on the planet. If we can build these in healthy communities and neighbourhoods, then we can be heading towards a truly sustainable future for the UK.”

To find out about Futurehome please visit our website

Watch this 3-minute to see all the benefits of designing to Passivhaus standards: https://youtu.be/hsDVIt7T7nU

Find out more about the benefits of building to the Standard in the Passivhaus goes Personal campaign aimed at self-builders.

0 notes

Note

An argument I hate- my ancestors did that, not me.

There’s three major reasons that “argument” doesn’t work. (please note when I use ‘you’ I’m not referring to you specifically anon, but white people who say this kind of thing)

1) “Ancestors” implies it’s only old history and not in fact things that were less than a century ago

Unless you’re under the age of 21, Canada’s federally run Residential School System has been active within your lifetime.The last (federally controlled) school closed in 1996, in Saskatchewan, after 150 years. While you or your parents were probably having a grand old time playing cowboys and indians in the backyard, real native kids were being tortured. And when I say tortured I mean in every meaning of the word. Physically, emotionally, mentally, spiritually, sexually… they even conducted medical experimentation on them. And if your never learned this in school, you should read about it yourself. Does it make you uncomfortable? Good. That means you have more of a conscience than the people who actually did these things. (Which doesn’t take much.)

Here’s some other examples of Indigenous persecution in the 20th century.

It’s the kind of trauma that affects entire communities in a profound way. It’s the kind of trauma that is intergenerational.

2) Everything that happened then still happens today

White people are still killing native people without legal repressions. In fact instead they are rewarded for it.

Native communities asking for medicine are instead sent body bags and hand sanitizer. Native communities are still denied food, water, safe housing, and other basic requirements of living.

Native people are still hit with barriers to employment that white people don’t even know about. And working is basically a guarantee to subjecting yourself to racial discrimination. (Frankly the stats stated in this article are even lower than I believe to really be true, because it’s common to not speak up about these things to avoid punishment.)

Children are still being taken from their families, abusing the foster care system. Indigenous people are sterilized without consent.

Despite making up 5% of Canada’s population, native men make 28% and women make 43% of incarceration rates; being Indigenous is enough in itself to warrant more jail time for the exact same crimes as nonnative people.

Sacred Land is still being stolen and sold and desecrated without permission. (Too many examples to even link.)

And we really, really could go on, but you get the picture. Which leads to the final and most important point…

3) Ya still actively benefit from the things your ancestors did

Fun fact: The Iroquois and Wabanaki Confederacies did not always get along before European settlers came here. Sometimes disputes were settled with a healthy game of lacrosse, and sometimes we fought, and we killed each other. Today we’re chill, of course, and neither of us benefit in any way from the things our ancestors did. The same cannot be said for white people who’s family wealth comes from scalp bounties. Who get the job only because the other applicant was Indigenous. Who don’t have to be afraid of the police or the legal system your ancestors built, but instead can count on them to help you. And even little things that add up that you may not even realize is a privilege, like always seeing yourself in media as heroes.

Anyway, all the above is just about Canada and Indigenous peoples, but make no mistake, it exists on a global level.

EDIT: Yes this is okay to reblog

27 notes

·

View notes