#to represent the Fred MacMurray character

Text

also if i put an annoying version of a song in my playlists, it's there for a reason

#this is about#mel torme's#secret agent man#painting austin powers as out of touch#and seth macfarlane#'reprising'#“You Couldn't Be Cuter”#on my#the philadelphia story#playlist#acting as a suitably square stand-in for george#also#vic damone 'reprising'#“the things we did last summer”#in my playlist for#the apartment 1960#to represent the Fred MacMurray character

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Joke's On Him

The New York of “Eyes Wide Shut” is a dream of New York—a sex dream about an emotionally and carnally wound-up young man who denies his animal essence, his wife’s, and almost everyone’s. It’s a comedy. Stanley Kubrick’s movies are comedies more often than not—coal-black; a tad goofy even when bloody and cruel; the kind where you aren’t sure if it’s appropriate to laugh, because the situations depicted are horrible and sad, the characters deluded.

To make a film like this work, you need one of two types of lead actors: the kind that is plausible as a brilliant and insightful person who trips on his own arrogance (like Malcolm McDowell’s Alex in “A Clockwork Orange,” Matthew Modine’s Pvt. Joker in “Full Metal Jacket,” and Humbert Humbert in “Lolita”); or the kind that reads as a bit of a dope to start with, and never stops being one. The latter category encompasses most of the human characters in “2001: A Space Odyssey”—first cavemen, then cavemen in spaceships, that legendary bone-to-orbit cut preparing us for the end sequence in which astronaut Dave Bowman evolves while gazing up in awe at the re-appeared monolith—and Ryan O’Neal as the title character of “Barry Lyndon,” a tragedy about a ridiculous and limited man who bleeds and suffers just like everyone, and is moving despite it all.

Tom Cruise’s Dr. Bill Harford in “Eyes Wide Shut” is the second kind of Kubrick hero. He’s is a bit of a dope but takes himself absolutely seriously, never looking inward, at least not as deeply as he should. An undercurrent of film noir runs through most if not all of Kubrick’s films. His first two features, the war fable “Fear and Desire” and the boxing potboiler “Killer’s Kiss,” were stylistically rooted in noir—“Fear and Desire,” like “Paths of Glory” and “Full Metal Jacket,” has terse, hardboiled narration, linking it to the most overtly noir-ish Kubrick film, his breakthrough “The Killing.” The film noir hero tends to be a smart, ambitious, horny guy who lets his horniness overwhelm his judgement. Dr. Bill is a cuckolded film noir patsy turned film noir hero, cheated upon not in fact, but in his own imagination. And, in noir hero fashion, he gets drawn into a sexual/criminal conspiracy, this one involving the procurement of young women for anonymous orgies with rich older men. He’s always one step behind the architects of the plan, whatever it is, and he's never quite smart enough or observant enough to prove he saw what he saw.

That’s Bill, a cinematic cousin of somebody like Fred MacMurray in “Double Indemnity” or William Hurt in “Body Heat,” but diminished and driving himself mad, a eunuch with blueballs, prowling city streets on on the knife-edge of Christmas, constantly taunted and humiliated, his heterosexuality and masculinity, indeed his essential carnality, questioned at every turn.

The doctor’s nighttime odyssey (like “2001,” this film is indebted to Homer) kicks off after he smokes pot with his gorgeous young wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) and she confesses a momentary craving for a sailor so powerful that she briefly considered throwing away her stable life just to have him. The revelation of the intensity of his wife’s sexual craving for someone other than him (fear and desire indeed) unmoors him from his comfortable existence and sends him careening around the city, where he encounters women who all seem to represent aspects of his wife, or his reductive view of her. They even have similar hair color. And if there are men in their lives—like Sidney Pollack’s Victor Ziegler, who calls Bill to deal with a young woman who overdosed on a speedball while in his company; or Rade Serbedjia’s Millich, the pathologically controlling and jealous costume shop proprietor who accuses Bill of wanting to have sex with his teenage daughter (Leelee Sobieski)— They mirror aspects of Bill. It’s surely no coincidence that the masks worn by the orgy participants are distinguished by their prominent (erect) Bills. Bill never actually strays, though. He keeps blundering into situations where sex seems imminent, and yet he couldn’t cheat on Alice even if he wanted to. He’s too bad to be good and too good to be bad.

It still seems amazing that Cruise, among the most controlling of modern stars, gave himself to Kubrick so completely, letting himself be cast in such a sexually fumbling, baseline-schmucky part, the sort Matthew Broderick might've played for more obvious laughs (Kubrick originally wanted Steve Martin as Bill). Cruise built his star image playing handsome, fearless, cocky, ultra-heterosexual young men who mastered whatever skill or job they'd decided to practice, be it piloting fighter jets, driving race cars, playing pool, bartending, practicing law, representing pro athletes, or being a secret agent. Offscreen, the actor was long suspected of being closeted—a rumor amplified by his hyper-controlling relationships with a succession of public-facing spouses who read, from afar, less as wives than wife-symbols—and he sued media outlets that implied he was anything other than a 100% USDA-inspected slab of lady-loving, corn-fed American beefcake (thus the infamous 2006 “South Park” “Tom won’t come out of the closet” scene).

So it was doubly startling for 1999 audiences to watch Cruise being swatted across the screen from one cringe-inducing psychosexual horror setpiece to the next, each enjoying its own version of a hearty pirate’s laugh at the idea of Cruise playing a butch straight man who dominates every room he’s in; and to witness his onscreen humiliation by homophobic frat boys. That same year, Cruise got an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actor in “Magnolia,” playing a motivational speaker who admonishes his audience of baying young men to “respect the cock, tame the cunt.”

Cruise is a smart actor with often-excellent taste in material and collaborators; it’s inconcievable that he and his then-wife Kidman would submit themselves to over a year’s worth of grueling, repetitive shoots on Kubrick’s meticulously recreated New York sets in London without understanding what they were in for, at least partially. But what’s really important, from the standpoint of Cruise’s performance, is that he never seems as if he knows that the joke is on Bill. This doesn’t seem like the performance of an actor who has decided not to play his character as self-aware (like, say, Daniel Day-Lewis in “The Last of the Mohicans,” playing a character that Entertainment Weekly’s Owen Gleiberman described as seeming completely free of 20th century neuroses) but rather a not-too-self-aware actor throwing himself into every scene as if bound and determined to somehow “win” them. This is surely a vestigial leftover of the way Cruise acts in most Tom Cruise films, strutting and bobbing through scenes, getting into trouble, then smiling or talking or flying or running or acrobatting his way out. It’s a mode he can’t entirely turn off, but can only tamp down or allow to be subverted (which is what I think is happening in this movie, and in a few other against-the-grain Cruise performances). It’s as if Cruise travels the full narrative length of Kubrick’s dream trail encrusted by scholarly and journalistic and critical footnotes that have accumulated on his filmography since "Risky Business." He’s the leading man as Christmas tree, festooned with lights and baubles.

What perfect casting/what a great performance/what’s the difference? Is there any? Maybe not. Sometimes great casting is what allows for a great performance. John Frankenheimer cast Laurence Harvey, a handsome hunk of wood, as the brainwashed assassin in the 1962 version of “The Manchurian Candidate,” and his inability to tune into his costars’ emotional wavelength works for the part; it translates as “repressed, tortured, closed off individual,” the type of guy who would be gobsmacked by an ordinary summer romance, to the point where it would constitute the core of a tragic backstory. Harvey’s inexpressiveness becomes a source of mirth when he’s put in the same frame with actors like Frank Sinatra, Angela Lansbury, or Akim Tamiroff, who get a predatory glint in their eye when they sense the possibility of stealing a scene. They know how to mess with people and have fun doing it, and poor, friendless Harvey is an irresistible target. and when Raymond expresses delight that he was, however momentarily, “lovable,“ you can practically see the quote marks around the word, and it’s as sad as it is hilarious.

Oliver Stone pulled off something similar when he cast Cruise as Ron Kovic in “Born on the Fourth of July,” a choice that Stone later said might’ve hurt the film at the American box office because nobody wanted to see the smirking flyboy from “Top Gun” castrated by a bullet, wheeling around with a catheter in his hand, cursing his mom and Richard Nixon. The star seeming not-entirely-in on—not the “joke,” exactly, but the vision of the movie—made Kovic’s dawning self-awareness of his participation in macho right-wing propaganda all the more effective. Kovic wanted to be like the guys on the recruiting poster, and now he couldn’t stand up and salute the lies anymore, and a lot of his friends were dead, along with untold numbers of Vietnamese. Al Pacino, who was cast in an aborted version “Born” a decade earlier, might not have been as effective as Cruise overall, because while Pacino is an altogether deeper actor, he’s so closely associated with men who have no illusions about how brutal and soul-draining American life and institutions can be. (Marvelous as his performance in “Serpico” is, it doesn’t start to take off until he’s in undercover cop mode, with that beard and long hair and beatnik/hippie energy. In the early scenes where he’s clean-shaven and idealistic, you just have to take Serpico's innocence on faith, because Al Pacino would never be that naive.)

Kubrick, no slouch at casting for affect, was especially good at filling lead male roles with actors who seemed to grasp the general outline of what the director was up to without radiating profound appreciation of the philosophical and cultural nuances. Ryan O’Neal in “Barry Lyndon” somehow works despite, or because of, seeming a bit stiff and anachronistic—out of his element in a lot of ways. His anxiety-verging-on-panic at not knowing whether he’s doing a good enough job for Kubrick fits perfectly with the character’s persistent insecurity and imposter syndrome. So does the shoddy Irish accent.

Decades later, Ben Affleck in “Gone Girl” pulled an “Eyes Wide Shut”—or maybe it’s more accurate to say that director David Fincher pulled it by casting him. “The baggage he comes with is most useful to this movie,” Fincher told Film Comment. “I was interested in him primarily because I needed someone who understood the stakes of the kind of public scrutiny that Nick is subjected to and the absurdity of trying to resist public opinion. Ben knows that, not conceptually, but by experience. When I first met with him, I said this is about a guy who gets his nuts in a vise in reel one and then the movie continues to tighten that vise for the next eight reels. And he was ready to play. It’s an easy thing for someone to say, 'Yeah, yeah, I’d love to be a part of that,' and then, on a daily basis, to ask: 'Really? Do I have to be that foolish? Do I have to step in it up to my knees?' Actors don’t like to be made the brunt of the joke. They go into acting to avoid that. Unlike comics, who are used to going face first into the ground.”

Fincher subsequently poked fun at Affleck, in DVD narration and interview comments delivered in such a deadpan-vicious way that you couldn't tell if Fincher was venting in the guise of a put-on or doing an elaborate comedic bit. Either way, the gist was that Affleck was convincing as an untrustworthy person because he was himself untrustworthy. "He has to do these things in the foreground where he takes out his phone and looks at it and he puts it away so his sister doesn’t see it," Fincher said. "There are people who do that and it’s too pointed. But Ben is very very subtle, and there’s a kind of indirectness to the way he can do those things. Probably because he’s so duplicitous." Thus does the inherent untrustworthiness of Ben Affleck as both actor and person (according to Fincher, whether he's kidding or serious) become the framework for the entire performance's believability. This is a guy whose performance as an innocent man is judged by the media and public and immediately found lacking, and the character proves to be so much dumber than his conniving, vengeful wife that when the final scene arrives, we laugh at how inevitable it was. A more subtle, likable, deep leading man might've have ruined everything. Fincher needed a meathead who was funny and had read a few books, and who seemed to have a sixth sense for how to hide a cell phone from his sister.

This is similar to the idea of Kubrick cuckolding Cruise with an anecdote and sending him all over New York in search of satisfaction and insight that never quite, er, comes (although there’s a hint of hope in that final scene). On top of that, Affleck is an actor who is effective within a narrow range but will never be thought of as a chameleonic or particularly delicate performer—somebody who can play the subtext without overwhelming the text, or who can seamlessly integrate the two so that you can’t tell where one ends and the other begins.

That might be why Affleck disliked working with Terrence Malick, a highly improvisational filmmaker who deals in archetypes and symbols, and expects actors to devise a character while he’s devising the film that they’re in. Ryan Gosling and Brad Pitt can do that; Affleck really can’t. The difference between Affleck and somebody like Pitt (or DiCaprio) is the difference between an old-fashioned square-jawed leading man-type, like Rock Hudson or Gary Cooper or Alan Ladd, who tried to stick to the words and hit the marks and color within the lines, and somebody like James Dean or Marlon Brando or Dennis Hopper, who treated every page as potential raw material for a collage they hadn’t thought up yet. That’s why Dean and Hudson played off each other so beautifully in “Giant”—Dean with his tormented Method affectations and odd expressions and voices, and Hudson playing the guy he’d been told to play, while often seeming puzzled or horrified by whatever Dean was doing opposite him, as if he’d been placed in the same room with a badger or wild boar and told “Now the two of you sit down and have a nice lunch while we film it.”

I like to think of Cruise in “Eyes Wide Shut” as Rock Hudson turned loose in a Stanley Kubrick neo-noir dream, and not just for the obvious reasons. He’s in there angrily and desperately trying to win something that cannot be won, explain things that can’t be explained, and regain dignity that was lost a long time ago and will never come back. He keeps flashing his doctor’s ID as if he’s a detective (another film noir staple) working a case, and people indulge him not because they truly regard the ID as authority but because Bill’s intensity is just so damned odd that they aren’t sure how else to react. It’s hilarious because Bill doesn’t know how ridiculous it all is, and how ridiculous he is. He’s a movie star who lacks the movie star’s prerogative. Only by surrendering to the flow and accepting defeat can he survive. Only his wife, an awesome force unlocked in one moment, can save him.

-Matt Zoller Seitz

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

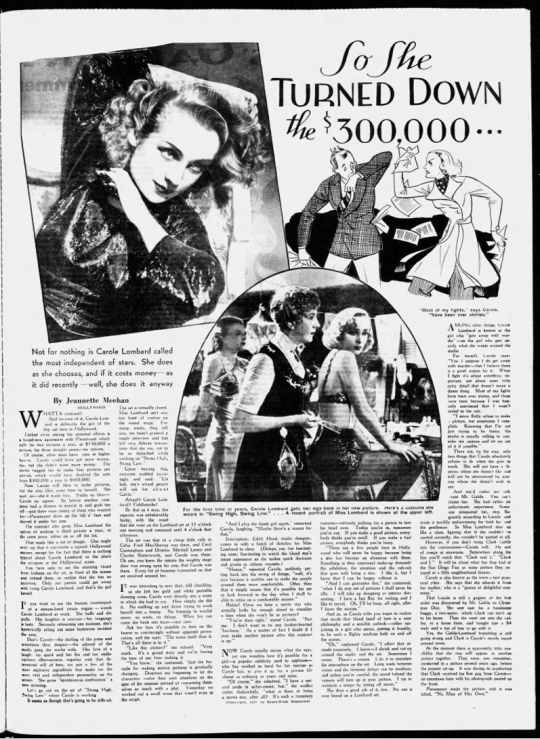

Feb. 7, 1937: The Girl of the Day

Whatta contract!

And because of it, Carole Lombard is definitely the girl of the day out here in Hollywood.

Tucked away among her personal effects is a brand-new agreement with Paramount which calls for two pictures a year, at $150,000 a picture, for three straight years – no options. Of course, other stars have come at higher figures. Carole could have got more money, too, but she didn’t want more money.

The studio begged her to make four pictures per annum, which would have doubled the ante from $300,000 a year to $600,000.Now Carole still likes to make pictures, but she also likes some time to herself. She said no – she’d make two. Studio no likee – Carole no signee.

So before another company had a chance to muscle in and grab her off – and there were plenty of them who wanted her – Paramount drew up the bill o’fare and shoved it under a pen.

The contract also gives Miss Lombard the option of making a third picture a year, at the same price, either on or off the lot.

That reads like a lot of dough. One might even say that it represents a typical Hollywood success, except for the fact that there is nothing typical about Carole Lombard or the place she occupies in the Hollywood scene. You have only to see the stunning blond from Indiana on the set, in front of the scenes and behind them, to realize that she has no imitators. Only one person could get away with being Carole Lombard, and that’s the girl herself.

If you want to see the human counterpart of a streamline steam engine – watch Carole Lombard at work. Her laughter is raucous- her language is lusty. Seriously rehearsing one moment, she’s hysterically acting out some humorous incident the next.

That’s Carole – the darling of the press and sometimes their despair – the adored of the studio gang she works with. Her love of a laugh, her spark and her fire and her undisciplined effervescence, together with that determined will of hers, are just a few of the more explosive ingredients that make her the most vital and independent personality on the screen. She gives “spontaneous combustion” new meaning.

Let’s go out on the set of “Swing High, Swing Low” where Carole is working. It seems as though that’s going to be difficult. The set is virtually closed. Miss Lombard isn’t any too fond of visitors on the sound stage.

For many weeks, they tell you, she hasn’t granted a single interview and has left very definite instructions that she was not to be disturbed while working on “Swing High, Swing Low.” Upon hearing this, everyone nodded knowingly and said: “Uh huh, she’s afraid people will ask about Gable.”

Afraid? Carole Lombard? Fiddlesticks!

Be that as it may, this reporter was unbelievably lucky, with the result that she went on the Lombard set at 11 o’clock one morning and remained until 4 o’clock that afternoon.

The set was that of a cheap little cafe in Cuba. Fred MacMurray was there, and Cecil Cunningham and Director Mitchell Leisen and Charles Butterworth, and Carole was there. Oh yes, you knew the minute the weighty stage door was swung upon for you, that Carole was there. Every bit of business transacted on that set revolved around her.

It was interesting to note that, still chuckling as she left her gold and white portable dressing room, Carole went directly into a scene in which she had to cry. How simply she did it. No walking up and down trying to work herself into a frenzy. No listening to woeful music, no waits, no delays. When her cue came she burst into tears – real ones.

Ask her how it’s possible to turn on the faucet so convincingly without apparent provocation and she says: “The scene itself does it. That’s all there is to it.”

“Like this picture?” she echoed. “Very much. It’s a grand story and we’re having the time of our lives making it.”

“You know,” she continued, “that the formula for making motion pictures is gradually changing. Directors are beginning to let the characters evolve their own situations on the spur of the moment instead of concerning themselves so much with a plot. Yesterday we worked out a swell scene that wasn’t even in the script. “And I play the dumb girl again,” remarked Carole, laughing. “Maybe there’s a reason for that.”

Interruption: Edith Head, studio designer, comes in with a batch of sketches for Miss Lombard to okay. (Delays, yes, but fascinating ones; fascinating to watch the blond star’s intent expression as she makes quick decisions and grants or refuses requests.)

“Money,” repeats Carole, suddenly getting back into the swing of things, “Well, it’s nice because it enables one to make the people around them more comfortable. Other than that it simply means that it’s possible for me to look forward to the day when I shall be able to retire on a comfortable income.”

Retire! Have we here a movie star who actually looks far ahead to visualize a time when she won’t be in pictures?

“You’re darn right,” stated Carole. “Not me. I don’t want to be any broken-hearted ‘has-been.’ As a matter of fact I doubt if I ever make another picture after this contract is up.”

Now Carole casually means what she says, yet one wonders how it’s possible for a girl – a popular celebrity used to applause – who has worked as hard for her success as Carole has, to give it up for a private life almost as ordinary as yours and mine.

“Of course,” she admitted, “I have a natural pride in achievement but,” she scoffed rather disdainfully, “what is there in being a movie star after all? It’s such a transitory business – certainly nothing for a person to lose his head over. Today you’re in, tomorrow you’re out. If you make a good picture, everybody thinks you’re swell. If you make a bad picture, everybody thinks you’re lousy.

“There are a few people here in Hollywood who will never be happy because being a star has become an obsession with them. Something in their emotional makeup demands the adulation, the attention and the rah-rah that goes along with being a star. I like it, but I know that I can be happy without it.

“And I can guarantee this,” she continued, “when I do step out of pictures I shall never be idle. I will take up designing or interior decorating. I have a fair flair for writing and I like to travel. Oh, I’ll be busy, all right, after I leave the movies.”

And so, as Carole talks you begin to realize that inside that blond head of hers is a sane philosophy and a sensible outlook – rather surprising in a girl who seems, putting it frankly, to be such a flighty madcap both on and off the screen.

“Oh,” explained Carole, “I affect that attitude purposely. I know – I shriek and cut up around the studio and the set. Sometimes I swear. There’s a reason. I do it to stimulate the atmosphere on the set. Long waits between scenes and the tiresome delays can be insidious, and unless you’re careful the mood behind the camera will turn up in your picture. I try to maintain a tempo by letting off steam.”

She does a good job of it, too. No one is ever bored on a Lombard set.

Among other things, Carole Lombard is known as the girl who “gets away with murder” – as the girl who gets exactly what she wants around the studio.

For herself, Carole says: “Yes, I suppose I do get away with murder – but I believe there is a good reason for it. When I fight it’s about something important, not about some little petty detail that doesn’t mean a damn thing. Most of my fights have been over stories, and those have been because I was honestly convinced that I wasn’t suited to the role.

“I never flatly refuse to make a picture. Knowing that I’m not just trying to be funny, the studio is usually willing to consider my opinion and let me out of it if possible.”

There are, by the way, only two things that Carole absolutely refuses to do when she goes to work. She will not have a director whom she doesn’t like and will not be interviewed by anyone whom she doesn’t wish to see.

And she’d rather not talk about Mr. Gable. You can’t blame her. She had rather an unfortunate experience. Someone misquoted her, very flagrantly according to Carole, and made it terribly embarrassing for both her and the gentleman. So Miss Lombard shut up like a clam, figuring that if she couldn’t be quoted correctly, she wouldn’t be quoted at all.

However, if you don’t bring Clark Gable into the conversation – Carole will. He sort of creeps in unawares. Somewhere along the line you’ll catch that “Clark and I,” “Clark and I.” It will be about what fun they had at the San Diego Fair or some picture they enjoyed at a little neighborhood theater.

Carole is also known as the town’s best practical joker. She says that she inherits it from her mother, who is a “genius at delightful nonsense.”

That Carole is still a gagster of the first order was discovered by Mr. Gable on Christmas Day. She sent east for a handsome buggy, a two-seater, which Clark can hitch up to his horse. Then she went out into the valley, to a horse farm, and bought him a $4 mule and a ton of hay to go with it.

Yes, the Gable-Lombard friendship is still going strong and Clark is Carole’s steady escort around town. At the moment there is apparently little possibility that the two will appear in another picture together.

They were, you remember, co-starred in a picture several years ago, before the present set-up. It was during its production that Clark received his first gag from Carole – an enormous ham with his photograph pasted on the front. Paramount made the picture, and it was titled, “No Man of Her Own.”

Feb. 7, 1937 – Arizona Republic

0 notes

Text

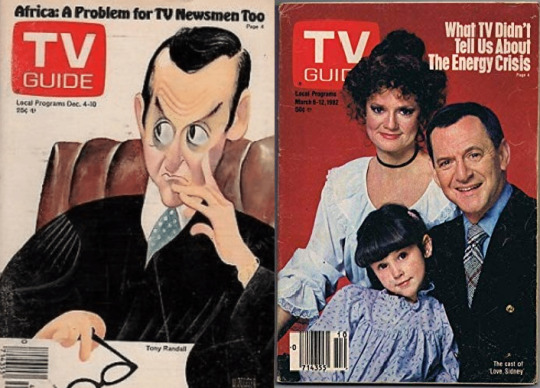

TONY RANDALL

February 26, 1920

Anthony "Tony” Randall was born Aryeh Leonard Rosenberg to a Jewish family in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He is best known for his role as Felix Unger in a television adaptation of the 1965 play The Odd Couple by Neil Simon. In a career spanning about six decades, Randall received six Golden Globe Award nominations and six Primetime Emmy Award nominations, winning one.

Randall attended Northwestern University before going to New York City to study acting. Randall worked as a radio announcer and served four years with the US Army during World War II.

Randall appeared on Broadway in Katharine Cornell's production of Antony and Cleopatra (1947–48) alongside Cornell and Charlton Heston and Maureen Stapleton.

This began a love of theatre that spanned more than fifty years and won him a 1958 Tony nomination for Oh Captain!

Randall's first major role in a Broadway hit was in Inherit the Wind (1955–57) portraying Newspaperman E. K. Hornbeck (based on real-life cynic H. L. Mencken), alongside Ed Begley and Paul Muni. In the 1960 film his role was played by Gene Kelly.

His first screen appearance was a brief appearance (uncredited) as a camera man in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942).

Busy with theatre, his next screen appearance was also his television debut: a recurring character on “One Man’s Family” (1950-51) with Eva Marie Saint (above).

He played the title role in a February 1959 episode of “The Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse” titled “Martin’s Folly”. The episode also featured now-iconic television performers Jay North, Bart Braverman, Frank Cady, George O’Hanlon, Phil Ober, and Carl Reiner. The show was hosted by Desi Arnaz.

In September 1970 he began playing the role that would make him a household name, Felix in “The Odd Couple” appearing in all 114 episodes of the series alongside the other half of the ‘couple’, Jack Klugman as Oscar Madison.

During his second year of “The Odd Couple” he took time to appear on “Here’s Lucy” in “Lucy and the Mountain Climber” (HL S4;E2) on September 20, 1971.

From 1978 to 1981 he had his own show, “The Tony Randall Show” playing a Judge for 2 seasons on CBS. From 1981 to 1983 he had another show titled “Love, Sidney” playing a middle-aged gay artist sharing his New York apartment with a single mother and her little girl.

Randall appeared on several awards shows and specials that also featured Lucille Ball:

“CBS On The Air” (1978) ~ Randall represented Saturday nights on the five-night celebration, a night also led by Carol Burnett, Audrey Meadows, Betty White, Fred MacMurray, and Mike Connors.

“Dean Martin Celebrity Roast for Jimmy Stewart” (1978) ~ Randall and Ball are both on the dais.

“Night of 100 Stars II” (1985) ~ held at Radio City Music Hall.

“Happy Birthday, Bob: 50 Stars Salute Your 50 Years with NBC” (1988)

Randall shares a birthdate with other “Lucy” guest stars Jackie Gleason and Robert Alda. When “Goodbye, Mrs. Hips” (HL S5;E23) first aired on their birthdays in 1973, Randall turned 53, Gleason was 57, and Alda was 59.

In “Lucy’s Replacement” (HL S4;E19) in January 1972, Kim calls Harry and EXMO (computer) “the odd couple”. While it might be taken as a general reference (and Randall’s name or character is not mentioned), the sitcom was proving immensely popular with viewers at the time of filming.

Randall was married to his high school sweetheart Florence Gibbs from 1938 until her death in 1992. He remarried in 1995 to Heather Harlan, 50 years his junior. The couple had two children and remained married until his death in May 17, 2004 of pneumonia contracted following coronary bypass surgery.

Randall was an advocate for the arts founding the short-lived National Actors Theatre. He was also an anti-smoking advocate and did charity work to fight AIDS.

"The public knows only one thing about me: I don't smoke." ~ Tony Randall

#Jack Klugman#Lucille Ball#Here's Lucy#Gale Gordon#Desilu#TV#The Odd Couple#Broadway#Oh Captain!#Inherit the Wind#Love Sidney#The Tony Randall Show#TV Guide

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tribute to Eleanor Parker by Roger Fristoe

When I was a youngster watching the 1952 film ABOVE AND BEYOND, I knew nothing about the movie’s leading lady, Eleanor Parker. But something about her instantly captivated me. It was partly that elegant face with the classic profile, the sweep of her brow and a framing wave of blonde hair. Her low-pitched, resonant voice also carried a charge.

Above all, I loved Parker’s acting. Although too young at the time to understand the fine points of her performance in ABOVE AND BEYOND, I realized at some level that it was both completely natural yet somehow heightened. She found variety and passion in what might have been a one-note character, the loyal wife of a pilot facing the most formidable mission in Air Force history – dropping the A-bomb on Hiroshima.

The next Parker movie I saw was another 1952 release, SCARAMOUCHE. Her theatricality was given free rein in this one, and her sparkling performance was so opposite the one in ABOVE AND BEYOND that I could have sworn I was watching a different actress. Now a ravishing redhead in lavish costumes and elaborate stage makeup, she is the commedia dell'arte spitfire who spars with the title character played by Stewart Granger.

I was hooked. As I followed Parker’s film career over the years, catching each new movie in the theaters and reviewing her earlier work on television, I continued to be astounded by her versatility and somewhat puzzled that she wasn't an even bigger star.

She had it all – beauty, glamour, talent and an intense drive to break new ground as an actress. She attracted many of the movies' most prominent leading men, including: Errol Flynn (twice), John Garfield, Ronald Reagan, Humphrey Bogart, Fred MacMurray, Kirk Douglas, Stewart Granger, Robert Taylor (three times), William Holden, Glenn Ford, Frank Sinatra (twice), Robert Mitchum and Clark Gable. She was even billed above Charlton Heston on his home turf at Paramount Pictures during his heyday in the mid-1950s.

Parker refused to be typecast and project the same image in film after film. Also, she was reluctant to promote herself in the manner of most Hollywood stars. She disdained interviews and other publicity and was so shy of attention that she hated the idea of winning awards because she'd have to make an acceptance speech.

So this was an actress who never quite had the audience recognition bestowed upon such contemporaries as Susan Hayward and Lana Turner. I remember once remarking on what a favorite of mine Eleanor Parker was, only to be met with the response, "Oh, yeah, isn't she that tap dancer who was married to Glenn Ford?"

TCM's 2019 birthday tribute to Parker (who would have been 97 on June 26), doesn't cover her three Oscar-nominated performances: as the innocent-turned-hardened-convict in CAGED (1950); the tormented wife in DETECTIVE STORY (1951); and Marjorie Lawrence, the opera singer felled by polio, in INTERRUPTED MELODY (1955). Also missing are some of her most entertaining adventure/romances; in addition to SCARAMOUCHE there are ESCAPE FROM FORT BRAVO (1953), THE NAKED JUNGLE (1954) and MANY RIVERS TO CROSS (1955).

However, the tribute does cover the arc of Parker's career from contract player at Warner Bros. through her years as an independent actress and a star at glamorous MGM. THE LAST RIDE (1944) was the final in a series of B films she made for Warner Bros. In NEVER SAY GOODBYE (1946), her first movie with Errol Flynn, she looks gorgeous and shows a knack for comedy that would blossom in later films.

Also in 1946, Parker and Warner Bros. took a chance with her appearance in a remake of W. Somerset Maugham's OF HUMAN BONDAGE, playing the role in which Bette Davis had created a sensation 12 years earlier. Deemed lacking at the time of the remake's release, Parker's performance has since grown in stature. Despite problems in the film itself, I consider Parker's portrayal as good as Davis's and in some ways superior. (Parker's Cockney accent was so convincing that some English cast members thought it was for real.)

THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM (1955), directed by Otto Preminger and released through United Artists, has Frank Sinatra as a jazz drummer hooked on heroin, with Parker coming on strong as his possessive/obsessive wife.

Parker's MGM period is represented in the tribute by three films. In LIZZIE (1957), she delivers a performance as a woman suffering from a multiple-personality disorder that is every bit as expressive as Joanne Woodward's Oscar-winning turn the same year in THE THREE FACES OF EVE.

THE SEVENTH SIN (1957) is another Somerset Maugham story and another redo of a formidable performance from 1934 (Garbo's in THE PAINTED VEIL, the original title). It gives Parker a nice dramatic workout and proves that, like Garbo's, her face was a cameraman's dream.

In HOME FROM THE HILL (1960), a family melodrama set in Texas and directed with enjoyable flamboyance by Vincente Minnelli, Parker holds her own with Robert Mitchum as his embittered wife.

By the mid-1960s Parker was working mostly in television, where she found a wide range of parts, with an occasional featured role in films. She had her final role in 1991 and died on December 9, 2013.

Ironically, the best-remembered role of Parker's career is probably THE SOUND OF MUSIC (1965), in which she has a supporting role as the lovely, cool, chic, witty and lightly sardonic Baroness who loses Christopher Plummer to wholesome, perky Julie Andrews. (It was a decision on his part that I could never quite understand.)

I shared Plummer's real-life feelings about Parker when, on the occasion of her death, he offered this lovely quote: "I was sure she was enchanted and would live forever."

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Great Loss

You all probably know the old joke according to which there are three stages of life: youth, middle age, and “you look fabulous.” Hardy-har-har! But now it turns out there’s a fourth stage, the one characterized (at least retroactively) by the response “he/she was still alive?” For many of us, the death at age 96 last week of Doris Day was in that last category: I think I thought she had died years ago. But now I have a new candidate for that fourth stage: Herman Wouk, who died last Friday at age 103. This is more than slightly embarrassing to me however, because it turns out Wouk’s last book, published just three years ago, was entitled, Sailor and Fiddler: Reflections of a 100-Year-Old Author. How can I have missed that? I was and am a great fan, and to this day I consider Wouk to be one of our least appreciated American authors, a true giant who apparently ran afoul of the literary establishment by publishing book after book that resonated deeply with the reading public and brought him the commercial success that those people find impossible to square with true literary talent. I couldn’t disagree more. Mind you, those people didn’t (and don’t) think much of John Steinbeck or James Michener either.

Far more accurate in my mind were those who, at a gathering held at the Library of Congress in Washington in 1995 to celebrate Wouk’s eightieth birthday, acclaimed Wouk as an American Tolstoy. And, indeed, Wouk—in this just like Tolstoy—filtered what he saw of the world through his own religious consciousness to produce pageant-like novels filled (like life itself) with countless characters, some centerstage and others present only briefly for a moment before disappearing into the wings, some crucial to the development of the plot and others depicted as merely standing next to more pivotal personalities. And the intrigues and adventures of those personalities—varying from profound to trivial and from inspiring to shameful (and yet somehow never crossing the line to tawdry, let alone to truly vulgar)—those stories became, for both Wouk and Tolstoy, the canvas on which to paint a picture of the world not merely as they saw it but, far more profoundly, as their insight allowed them to understand it. That, after all, is the novelist’s true calling: not merely to tell make-believe stories about make-believe people but to use the narrative medium to say something insightful and moving about the real-life world in which the author and his or her readers actually live.

Like most of my readers, I suppose, my first Wouk novel was The Caine Mutiny, for which the author won the Pulitzer Prize in 1951 and which was made into an Oscar-nominated film in 1954 starring Humphrey Bogart, Jose Ferrer, Van Johnson, and Fred MacMurray. I loved the book, found it far more engaging than the movie, and resolved to read more, which I did: I believe that I read every single one of Wouk’s novels in the course of my lifetime as a devoted fan of his writing. I’ll read Sailor and Fiddler this summer.

Marjorie Morningstar was the first of Wouk’s novels to be published during my lifetime. (I had to wait a bit to get to it, though, since I was only two years old when it came out.) I had to read it surreptitiously, though—according to the idiotic rules that pertained during my teenage years, Marjorie Morningstar was a “girls’ book,” so not one any boy would be caught dead reading…at least not in public—and I also saw the 1958 movie starring Natalie Wood. (Other books boys didn’t read included Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and, of course, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. Enough time having passed, I now feel able to admit to having read both. Don’t tell the guys!) It too affected me deeply, but more because of its Jewish content than its plot…and also because of the fact Herman Wouk was born in the year of my mother’s birth and Marjorie Morningstar, née Morgenstern, in the year of my father’s. Because of that, I think, the whole book felt like a kind of a window into my parents’ world, and particularly into the strange ambivalence they brought to their Jewishness that Wouk captured perfectly in the opening chapters of the book. In the end, Marjorie sees the error of her ways—although she is given a strong push in that direction by her own failure to succeed as a Broadway actress—and ends up abandoning her decision to abandon her Jewishness, marrying a nice Jewish fellow named Milton Schwartz, and settling into suburban Jewish life. The Jewish ending had no precise parallel in my parents’ lives (other than them getting married and living happily ever after), but the effect the book had on me was profound…and eventually I lived out its dénouement personally by adopting an observant lifestyle and embracing a version of Judaism my parents felt more than able to live without.

And then there were The Winds of War and its sequel, War and Remembrance, published in 1971 and 1978 respectively. I read both with the greatest enthusiasm, identifying particularly strongly with one specific character, Berel Jastrow, who is depicted as being in 1941 roughly the age I was when I was reading the book and who functions as the Jewish heart and soul of the story line in the second book. What was remarkable about the books, I thought then (and still do), is how Wouk depicts the Hitler’s war against the Jews as one of two simultaneous wars of aggression being waged by the Nazis: one against any nation deemed to be standing in the way of Germany’s expansionist goals and the other against the Jewish people. Both wars are depicted in detail in both books and, indeed, the story revolves around two families, the Henrys and the Jastrows, who respectively represent these two wars in Wouk’s narrative. I found Wouk’s ultimate point—that neither war is fully comprehensible without a clear understanding of the other—both validating and motivating. Decades later, when I read Ken Follett’s Winter of the World (the second book in his “Century” trilogy), a book recounting the intertwined stories of five families during the years of the Second World War but in which the Shoah is almost never mentioned and is otherwise wholly absent from the narrative, I was struck by the degree to which Wouk’s worldview had become my own.

I think my favorite Wouk book is Inside, Outside, one of his least well-known works. Published in 1985, it tells the story of four generations of the same Jewish family from the vantage point of one Israel David Goodkind, who belongs to the third generation of the four. It’s an interesting book in a lot of different ways—filled with historical personalities like Richard Nixon (delicately left unnamed in the book but unmistakable), Golda Meir, Ira and George Gershwin, Marlene Dietrich, Bert Lahr, Ernest Hemingway, and others, what the book felt to me like it was really about was how a man who made every conceivable sacrifice to thrive in the highest echelons of American society, how even such a man in the end felt drawn back to his roots and ended up embracing a version of Judaism he had earlier on mostly rejected. That image of the Jewish individual sacrificing everything to succeed in the secular world and then returning, one way or the other, to his or her roots keeps coming back again and again in Wouk’s books. That isn’t my personal story, but it is the story of so many people I’ve known over the years that it is nonetheless very resonant with me. I suppose I should mention that I read Inside, Outside in our apartment on the Heinrichfuchsstrasse in Rohrbach, the little town outside Heidelberg that Joan and I lived in during the years I taught in Germany. So I read this book about American Jewry when I myself was both inside and outside—the ideal setting! I wonder if I’d find it as compelling today. I suppose could find out easily enough.

There’s a lot more to write about. I read Wouk’s “Israeli” novels, The Hope and The Glory when they came out in 1993 and 1994. They’re expansive, big books, the first covering the years from 1948 to 1967 and the second moving forward through the Yom Kippur War, Entebbe, and, finally, Anwar Sadat’s visit to Israel in 1977. Like The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, Wouk tells his story by intertwining the stories of fictional characters and historical personalities, and he does yeoman’s work in both volumes: even today if someone asks me what to read to “get” the whole Israeli story, I send them to those two books.

There are lots more books I could write about. I read Youngblood Hawke, Wouk’s fictional biography of a young American author not unlike Thomas Wolfe. I read Don’t Stop the Carnival, about a Jewish New Yorker who attempts to escape his own middle-age crisis by moving to a Caribbean island. And, of course, I read Wouk’s book about Judaism itself, This Is My God, in which the author talks about his own trajectory as a Jewish American but leaves for readers to see just how many pieces of how many of his novels were rooted in his own understanding of the nature of Jewishness and the ultimate meaning of Judaism.

There have been many great American Jewish authors, but few, if any, wrote about the Jewish part of their Jewish characters with more insight, with more sympathy for the spiritual dilemmas they encounter engaging with the secular world, and with more overt affection than Herman Wouk. Yehi zikhro varukh. May his memory a blessing for his readers and for us all.

0 notes