#today we have largely divorced the aesthetic from the political and we look at the last century and don’t fully understand it

Text

Over Casca’s naked body

Part one: A long premise

We can’t escape from our geopolitical context even when we are reading manga. We have internalized a good amount of beliefs, values, practices, even regulations from our lived experiences and various simulacra we have been exposed to, especially those in an audiovisual form.

If you grew up in the US, you know that freedom of speech is a core value there. But, while you can say mostly whatever you want within your own country, the US constitution has given the government the right to regulate what comes in from abroad. [1]

And that power has been used. Idealistically, greater access to common technologies even before the internet should have seen a redistribution of the media-creating capacity to many foreign countries outside of the US, so that people could tell their stories. But that hasn’t always been the case, with some exceptions, especially if we consider the biggest narratives that reached global popularity.

During the Cold War, anything that might be considered “communist propaganda” could be seized by the Post Office and never delivered. Books or even souvenirs from communist countries, for instance. Pamphlets criticizing US foreign policy. (…) Obviously it wasn’t totally like North Korea, plenty of foreign movies and music were allowed into the US. But the media that caught on was either already Americanized, or so plastically exotic that it doesn’t really say anything about the culture where it is from. The Beatles were British, but they got their start covering American rock and roll musicians. When John Lennon stepped out of the line, the American government made sure that he knew it. Movies imported from Japan were mostly samurai flicks, with very few movies set in the modern day. The film Ikiru is widely considered the best Japanese film ever made (…) but this existential drama about a depressed lonely man was only given a limited release in California, and the poster was edited to feature a stripper who is only in the movie for one minute. The narrow stream of European movies that made into the USA came in the form of the French New Wave cinema, movies that were stylistically inspired by American films, but also so stuffy that few audiences would ever want to watch them anyway. This was further stifled by the Hays Code, a set of extremely strict regulations that were in place from 1934 to 1968. (…) Some things that were completely banned from ever being shown in any film included: bad guys winning. All movies must end with the police outwitting the evil criminals, or the criminals causing their own demise. Any nudity. (…) Blood or dead bodies. (…) Interracial couples. White people as slaves. Criticism of religion, or of any other country. Naturally this prevented the more artistically liberal European films from being shown in American cinemas and when they did get a release, they were usually edited (…). At least until the rules were abolished in 1968 and replaced by the age rating system we have today. [1]

Even after several decades of access to the internet and foreign cultures, some attitudes have been internalized and carried on. For example, I had direct experience of the ways my own culture has been perceived and stereotyped or interpreted in terms not dissimilar from the exotic. And the same happens to me probably if I don’t keep in check my own personal beliefs about cultures that have been presented to me in similar ways. And I was surprised to see by how deeply rooted and spread are certain attitudes towards punishment or violent retribution viewed as necessary, the policing and self policing, and the expression of judgments or condemnation, and all this can complicate the understanding of different forms of narratives and the acceptance of different cultural attitudes and norms, without the expression of any opinion about morality or legitimacy.

I am reminding you that this is a long premise because I evidently don’t have the gift of brevity but this article is about Berserk and Casca.

In 1956 Anna Magnani won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her first English-speaking role in the American movie The Rose Tattoo. In 1958 Miyoshi Umeki was the first Asian born actress to win an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in Sayonara, a movie that despite its title was an American drama starring Marlon Brando. It isn’t hard to see in these decisions from the Academy, or the ones that followed in other categories, the willingness to build relationships between the US and specific foreign countries where the American army had a massive presence and that after WWII were ideal places for American investors, considering significant rebuilding necessary after the loss in the war. The movie industry and everything around it had instrumental roles. When it comes to the Academy Award, it is very interesting to notice that the women were the first ones to be nominated, becoming ambassadors and facilitators of the reshaping of the images of Italy and Japan from enemies to new essential strategic allies in the Cold War. And here comes the problem of the exotic, because after several decades I still see similarities in the American perception of those foreign cultures, Italian and Japanese, to those easy and friendly and intentionally constructed imaginaries of that time. Take the press around Anna Magnani or Miyoshi Umeki for example. Terms are so widely used and repeated that they are still in their Wikipedia pages in English today. For what interests me here, I am going to quote or summarize parts of the video essay listed below as [2] but I really recommend watching it entirely. It really helped me understand some of the issues I am talking about here, but it is much more than just this. And there is footage worth the time.

[I know that many people here on tumblr really dislike YouTube videos. I understand why, when it comes to manga and anime, written articles have still better quality and content, in my opinion, but there are also many video essayists doing their due diligence on several other topics. And when I am busy cooking I put them on].

In the 1950s one of the problem with the new alliance with Japan was the widespread hate and racism towards Japanese people.

The government stepped in, producing educational films meant to endear Japanese culture to Americans (…) They showed off Japanese industry, introduced Americans to sushi and sumo wrestling, explained the country’s new democratic system et cetera. (…) A lot of [musical] acts that were popular with American soldiers, specifically exoticized Asian girls bands, like the Kim sisters and the Tokyo Happycoats, come over to the US and appear on television as both entertainment and a sort of cultural ambassadors, not only demonstrating America’s cultural power and dominance by performing recognizable American tunes, but also signaling to white Americans that those cultures didn’t pose a threat. (…)

It’s worth looking at this film [Sayonara] as part of a larger theme in a very specific post war moment. Gina Marchetti points out in her book Romance and the yellow peril: «Between June 22, 1947, and December 31, 1952, 10517 American citizens, principally Armed Services Personnel, married Japanese women. Over 75% of the total Americans are Caucasian». Meaning, Japanese war brides and the concept of interracial marriages was very much a conversation. (…) Sayonara must be seen as one of many films which called for a new evaluation of Japan as an enemy nation. (…) Much of the way [Miyoshi Umeki] was discussed is probably exactly how you might expect. The language journalists used to describe her was unambiguously racialized and often condescending. In the aftermath of her Oscar win, for example, Louella Parsons called her «a lovely little bit of Japanese porcelain», adding: «What a cute little thing she was in her native costume». Still, her Japanese identity also seemed to serve as a symbol, an embodiment of the new friendly Japan. In Miyoshi, Americans would find an idealized portrait of reconciliation, a woman who bore no resentment over the war, a woman who brought homesick American troops to tears by singing White Christmas, who adored American pizza, who learned English by listening to American records. She was accepted because she actively appreciated and participated in American culture. [2]

The roles offered to Miyoshi Umeki are significant in many ways. After Sayonara, she was cast to play other Asian characters besides Japanese ones. One recurring theme in those movies in particular is the contrast between modernity and tradition.

William G. Hyland writes, Flower Drum Song is a «clash between the Americanized lifestyle of the young Chinese and the traditions of their parents». (…) Miyoshi Umeki plays Mei Lee, a Chinese stowaway who arrives in the US for an arranged marriage. The more Americanized she becomes the more independent, the more willing she is to strike out on her own. [Chang-Hee] Kim writes: «[Flower Drum Song] flamboyantly shows that Asians in America were ready and willing to cast off their heritage and become real Americans in repudiation of the pre-war racial consideration of Asians as permanent aliens». I mention this not only because it’s one of Miyoshi’s major roles, but also because this theme, a supposed enlightenment via westernization, occurs again and again in her filmography, particularly in her work on television. Han [?] writes «Umeki’s representation on television is in constant oscillation between her status as a subservient Asian woman and her transformation into an assertive, modern female professional who has achieved independence through American cultural influence». [2]

Bear with me for a little longer if you can, because we are at the point where, watching the video, I experienced that sensation better translated visually in a lightbulb being turned on. I am skipping here the presentation of the story and footage from Miyoshi’s first appearance on television in The Donna Reed Show, but I once again invite readers to watch the video, which features high quality original footage. I was really struck by the “sensitive way” the American woman - Donna Reed I presumed - approaches the character played by Miyoshi, as the writers back then were well aware of the sensitive racial implications, and nevertheless a certain mentality pushes thought. Watching still, it is easier to avoid the presumption that in the 1960s “they didn’t know better” or that contemporary attitudes have improved greatly, just because we are more careful about the language we use.

The thesis statement of this episode is not subtle. The rejection of traditional Japanese customs allows her to live more fully in a democracy. Of course it isn’t really much of a choice, is it. Maintaining the customs of your culture or risking alienating your entire community. She changes her clothes, puts on a hat and goes shopping because she is an American now. Obviously these stories are told from the white American perspective, where this rejection of tradition and culture is portrayed as unambiguously positive and relatively tension free. This was not the case in Japan where the relationship between modernity and tradition were richly explored in cinema, particularly in women’s films. [2]

I would like to add that the independence that Donna’s character shows is only possible because of a series of factors, including the fact that her husband secures her a higher level of comforts, in comparison with lower classes or non-white Americans, and that domestic work is presumably done by home electrical appliances or other women, especially when you add child care and looking after the elderly to the equation. The unwillingness to consider those types of labor, traditionally carried on by women, as of equal importance to any other jobs is rarely discussed when it comes to the issue of women’s emancipation. Not to mention how, alongside this idyllic world shown on television, in the same country large numbers of women have to deal with continuous push backs in the name of different traditional values that all the same prevent many of them from achieving true equality. Those types of conversation and conflicts between traditional and modern happens at the same time in many countries and in most cases translates to continuous negotiations and compromises carried by men and women in real contexts and real situations, without necessarily white American women being aware of it or of all the necessary nuances.

Let me add this last element of conclusion about Miyoshi Umeki’s story.

In 2018 her son told Entertainment Weekly that in the 1970s she etched out her name on her Oscar and then threw the trophy away. Although he isn’t sure exactly why she did it he said: «She told me, I know who I am and I know what I did. It was a point of hers to teach me a lesson that the material things are not who she was». What Miyoshi Umeki achieved is pretty remarkable but one can’t help but feel that she could probably have done a lot more if she’d been allowed to move beyond her identity. [2]

Part two: Are we reading the same manga?

After considering all this, and more that I can possibly include in here to avoid this being even lengthier, I can’t help but wonder about the generalizations I have seen repeated vastly about portrayals of women in Japanese media, as well as misunderstanding of cultural attitudes towards nudity or the treatment of sensitive topics like sexuality and rape. There is a diffuse certain sense of entitlement, sometimes you can hear a condescending tone even, and this isn’t limited to the US. But why approach a foreign culture with a patronizing attitude instead of trying to understand the context more deeply? So many manga readers are willing to ask for clarification on translations, but not many ask about the context or the visual aspects involved in manga writing. I like to read analysis about different topics, so I look for them in English too because they are very numerous and easily accessible, but when it comes to the critique about the portrayal of women in too many cases I have to click away because of too many bias or that subtle sense of superiority of judgment. Berserk has become easily accessible and more and more popular but it is so greatly misunderstood at various degrees by a lot of its western readers - me included - and I really wanted to understand what is preventing, in most cases, a textual and contextual analysis.

The Hays Code hasn’t been around since 1968 but the sentiment that the only proper conclusion for every story is the triumph of the good guys and the punishment for the wicked is very much alive and well. There is this conviction that the only clever readers are those able to separate the heroes from the villains, or the good deeds from evil, and root for the right side to achieve retribution and satisfaction. The Hays Code hasn’t been enforced officially but it’s there in essence and every counter narrative has been rendered almost ineffective or judged poorly. As for the treatment of women, I don’t feel like we can honestly and surely compare or scrutinize Japanese media under special lenses. Nudity in comic books seems to me to be very common outside of Japan too, depending on censorship rules. I certainly notice how frequently Casca is shown naked or has been threatened with sexual violence, but I also notice that she isn’t the only one. The exaggeration of Guts’ muscles and the mutilation of his body are largely put on display. Griffith is intentionally shown fully naked, or completely covered by an elaborate armor, and he is subjected to many threats of physical and sexual violence as well. Charlotte is shown naked, but always in her bedroom, in a private environment or with a transparent cloth or a sheet of some kind to make her nudity different from the occasions when Casca’s body is publicly displayed. I am careful with my own thoughts when I read Berserk, I take the time to analyze my reactions and what I am feeling in these situations. I think that this is the reason that certain books or media are intentionally aimed to adults. I don’t feel a necessity to call to censorship or to give guidance of a moral kind but rather to make the necessary reflections. And I can’t imagine how someone can understand the story without taking their time with it.

Part three: Casca’s rape

In 1973 the animation studio Mushi Production released a film called Belladonna of Sadness. I haven’t seen it yet but I know a little about it and I am planning to watch it when I feel like I can do it without being affected in a bad way. It is well known that Miura remembered this film when he designed the Eclipse. In 1975 Pier Paolo Pasolini directed the film Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom, which I strongly don’t recommend to the casual viewer or anyone who felt even slightly offended by Berserk. Suffice to say that in a particular political climate and in the context of the sexual revolution of the late 1960s, in the 1970s nudity and sexuality were at the forefront of the debate and human bodies were exhibited in a symbolic way that can be misunderstood today without knowledge of the context. Gender expression was questioned and men grew their hair or refused to wear suits or to follow rigid dress codes regardless of their sexual orientation. Sexual acts were considered political acts in ways that aren’t comparable with today for many reasons. The languages, the words and the visuals we use are ever changing and actual for a moment and gone the next one or misunderstood. Many words used by queer people in the 1970s wouldn’t be received well today, because the context has been transformed. For what I understand, in films like Belladonna of Sadness and Salò rape and cruelty are preeminently used as symbols because rape and cruelty presented in a direct visual form effect greatly any type of audience and can’t go unnoticed. The sociopolitical climate in the 1970s, in the middle of the Cold War, was particularly violent, both in Italy and Japan, and the art of the time can be remarkably bleak. [Go Nagai’s Devilman was published between 1972 and 1973, Osamu Tezuka’s MW was published between 1976 and 1978, Takemiya Keiko’s Kaze to Ki no Uta was also published between 1976 and 1984].

Kentarō Miura was born in 1966, he breathed the air and grew up in that same climate and was influenced and informed by it, especially later, when he finds himself as a young man in the renewed bleakness of the 1990s. It is likely that he saw Belladonna of Sadness when he was old enough, when he started to develop the story of Berserk, and after being greatly influenced by Nagai’s Devilman. The number of sources of inspirations that Miura used for Berserk is vast, varied and multidimensional and includes books and novels and films of various genres (historical, fantasy, horror, sci-fi in particular) manga, foreign comics books, and traditional art. It is often pointed out among fans that he was also a big fan of Star Wars. Pop Culture Detective released a very interesting video essay called Predatory Romance in Harrison Ford Movies [3] that brought to my attention many things that I didn’t notice or thought about when I was seeing those films myself as a young girl [I am more or less a decade younger than Miura fyi]. Analyzing Star Wars, Indiana Jones or Blade Runner with particular attention to the relationship between the male lead, Ford, and women is an interesting exercise and helps to re-contextualize our judgment about the treatment of women across different media with arguably less reach than Star Wars. I am not inviting anyone to make comparisons and ranking which is better, or absolve Miura because he was influenced by the context around him as everyone else, but I am asking to let go of the presumption that Japanese media in particular presents problematic attitudes towards women by default. The problems are much more generalized than we’d probably like. Better analysis or methodologies are needed to make a proper assessment, and we really shouldn’t assume by default that manga (for boys and men) equals bad treatment of women.

I hope that someone is still reading after such a long time. I didn’t know how to make my point on Casca without at least presenting some of these considerations. I must say I have understood myself better, having questioned why I was feeling uncomfortable when reading Casca but not offended. I understood that Miura wanted me to feel that way, uncomfortable, horrified, and I can appreciate Berserk better [in particular as a person that wasn’t permitted to live in a female body without a certain type of violence].

As stated previously, I noticed that Casca is more exposed and shown in all her vulnerability in much extreme situations: to multiple men in very public displays, like on the battlefield or at the center of the circle of Apostles in the Eclipse. She is also shown naked and vulnerable in other moments, especially alone with Guts. Those intimate moments with Guts, during the Golden Age, are instrumental for the readers to see her in all her humanity, without the armor, or the female dress, in order to build an emotional connection with her. In the cave, Casca makes herself emotionally vulnerable in front of Guts for the first time and tells him her story, exposing her past, her goals and her true self. She tells him things about Grittith too, things that are meant to show Guts/the readers Griffith as much naked, vulnerable and human as she is. Let’s pay attention and try to recollect Guts’ reactions to her story: he is listening to her, but he is embarrassed, distracted and attracted by her nudity and he fails to see Griffith as a human being, potentially fallible and not much different from Casca or himself. Guts also fails to take away from the story the original message, something more than Casca’s infatuation with Griffith as part of her being a woman. Comparing Guts’ reactions to Casca’s nakedness, his recollections or focus on the conversation, what he takes from it and what he doesn’t: a big part of the male readership of Berserk is probably in his same situation. It isn’t till later by the waterfall, that we see Casca alone with Guts again in an intimate way. This time he is naked and vulnerable and completely exposed too. This time through the physical connection between the two, within the sexual act, Guts can’t hide himself anymore, can’t deflect from his past and his fears. I assume that that is an important moment for the male readership to start to feel emotionally invested in the connection between Guts and Casca. That emotional connection and the investment in the relationship helps them to see Casca as a human being through the Eclipse and if that didn’t work then they still can see and feel the horror of the rape of Casca through Guts. Because Miura didn’t want anyone to enjoy that scene or to be sexually aroused without at least the horror and the moral objection to it.

Casca is a woman of color, born in a disadvantaged family and community, that ended up in a mercenary group without achieving the things she wanted, never fully belonging and constantly threatened by groups of men on the enemy side with forms of violence specifically targeted and unnecessary cruel. And everything she goes through culminates or goes back to the Eclipse - before and after - and that should be taken as completely symbolic. Like the multiple instances of rape in Pasolini’s Salò, the innocent, poor and exploitable youth is violated by those in power or those who are in charge. Gambino decides that Guts is expendable or due a lesson in humility, he takes the money and coldly facilitates Guts’ rape. Gennon is rich and powerful and pretends to recreate his fantasy, a sick version of Greek ped*philia. And all he does is using money and power to horrifically exploit the youth and Griffith offers himself up and loses a fundamental part of himself in the process. But the most cruel thing in Berserk is Griffith surrendering to the call of power and doing the same thing to Casca, in the absence of lust or desire: the corruption that has been in him - and has reached Guts as well - has spread. Griffith’s surrender to the call of power, and his intolerance for more of his own pain, silences all empathy in him.

In conclusion, nudity has various narrative functions, beside the suggestion of the erotic: through each character’s naked body, male or female, we see their vulnerability and their fundamental humanity [and if I remember correctly in contrast the rapists are always dressed or covered]. And rape has a symbolic meaning, beside the literal one and the psychological exploration of trauma. Violence but in particular sexual violence is one of the most estreme and powerful tools that can be used in stories [especially in visual media], but unfortunately the overuse of it in an edulcorate format, or as a tease, or devoid of any meaning, has ceased to call for disgust and challenge us to think, has perhaps lessen the impact and the gravity around it. In the 1970s Pasolini saw the dark side of the sexual revolution and how the rich and powerful were willing to build economic empires just to have access to the youth and to the most beautiful women. But he wasn’t the only one. We should reconsider Belladonna of Sadness and the original meaning of those themes in films or later in manga like Berserk and think about it deeply and seriously and not approach every piece of art as entertainment.

Videography:

How America got so Stupid [1]

Miyoshi Umeki: The First East Asian Woman to Win an Acting Oscar [2]

Predatory Romance in Harrison Ford Movies [3]

#berserk meta#casca berserk#manga analysis#this is so long is embarrassing#today we have largely divorced the aesthetic from the political and we look at the last century and don’t fully understand it#editing when I catch a mistake or a misspelled word#eri reads berserk

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

White Shirt Shoot 1

In todays lecture we were given a task in order to kickstart us to produce content for our magazines. The task was to style a white shirt in a way that communicates our narrative taking the form of an informal photoshoot. The only rule was a white shirt had to be included; aside from that we could use any props, backgrounds and make up we wanted.

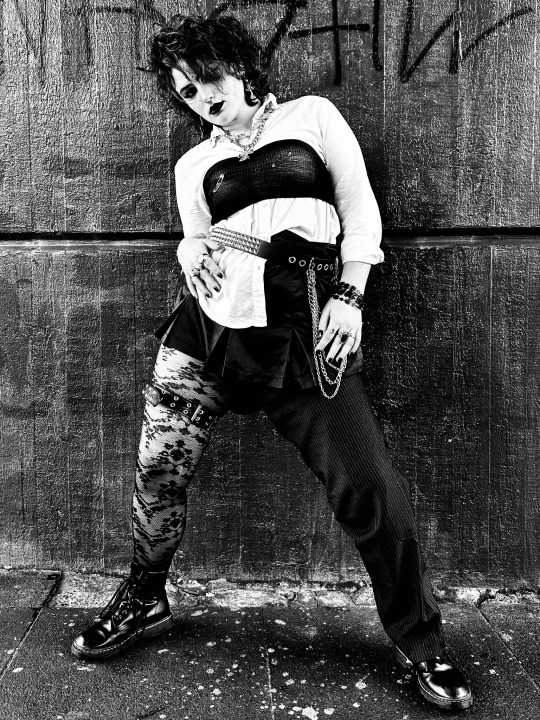

Before I begin to discuss each images qualities and disadvantages I am going to explain the stylistic choices I made regarding my models appearances. On my first model chloe, I styled the white shirt underneath a translucent boob tube with it half tucked into a leather mini skirt, underneath the skirt on one leg she wore a pair of pinstripe trousers, with floral pattered tights covering the other leg. I accessorised with a grommet belt around her right leg and a studded one around her waist, and two silver necklaces around her neck. Starting with the clothing, I went for the overlaying of the skirt on the trousers to mimic the DIY aesthetic that goth inherited from punk, as well the unique gender expression engrained in goth culture that I attempted to communicate by combining the skirt with the trousers; merging typical femininity and masculinity and dipping into their inherent gender blurring. The boob tube also stemmed from the DIY element, with the safety pins around the nipple acting as an expression of an average goths outward openness regarding sexuality, which is similar to why I incorporated the extra chains; I think they have loose kink connotations. Not only is the cross necklace made using a bike chain which perfectly demonstrates DIY, it indicates the respectfulness goths exhibit towards other cultures, religions and beliefs; which I first stumbled across in my research around the Visigoth’s sack of Rome; and their “politeness” towards Christian’s at that time. Aswell as this I also felt as though the cross’ unusually large size compared to typical religious crosses contributed to the extravagant, over the top style goth fashion possesses. I opted for the floral tights as one of my predictions based on my research thus far is that goth will take a much more feminine turn for all people that identity with the goth subculture; in short because of the increased awareness of the LGBTQ+ community and the development of pop culture influences such as Wednesday Addams. As for her hair and makeup, I attempted to emulate a trad goth look with heavy eyeliner, black lips and a pale complexion aswell as the exaggerated hair that I achieved through the use of back combing and hair spray. When exploring gothic rock I learnt the significance of Siouxsie Sioux and her band, so for the hair and makeup I took inspiration from her iconic look.

I think although this wasn’t my initial intention, my second model Sadie’s look is much more muted. I styled the white shirt underneath a band tee, paired with flared leather trousers, Jadon dr martens and accessories such as the grommet belt strung like a bag across her shoulder. Although the look has unusual elements such as the fingerless glove on one hand, in general it appears more put together and more resemblant of the modern goth; which I think is quite apparent when the two are stood together. I included the band t shirt to emphasis the importance of music in the development of goth, with the band “Divorce” actually being an indie / rock band from the early 2000s. I went with the dr martens because I feel as though they are a timeless staple within the goth wardrobe as well as that of many other subcultures. I feel as though the leather trousers contribute to the cleaner aesthetic this look has, and may be a material I consider to be involved in the future of goth.

Moving onto locations, I used various spots around and under the subway near my flat. Although I would’ve preferred to go further and take some photos in the oasis market to encorporate a musical background or around pigeon park to include its gothic style cathedral; the shoot was last minute and it was raining, so going to those locations would’ve comprised the hair and makeup etc. I think the most effective backgrounds are probably the overly textured walls with the graffiti on them, as the images they’re in exude almost a rebellious attitude; perfect for reflecting the anti establishment stance of goths dating back to the defeat of the Roman Empire.

0 notes

Text

Mad Men (☆☆☆☆)

Year: 2007 - 2014

Creator: Matthew Weiner

Spanning the sumptuous glamour of 1960′s New York, ‘Mad Men’ impresses as an intense character study of Don Draper, the enigmatic creative director of an ad agency, as we follow his spiral into depravity, alienation and, ultimately, redemption. The series also has a multitude of colourful characters, on their own difficult moral paths, to enjoy on the way down. To the phantom reader who wishes to watch this series but doesn’t want spoilers, I’m sorry to say, but everything will be revealed from here onwards...!

There are 90+ episodes of Mad Men so there’s a lot of plot to discuss. It’s also been a long time since I’ve watched the earlier episodes so I’ll be discussing in terms of the overriding thematic elements, rather than particular plot lines, to give an essence of what the show is really about.

The show’s central tenet is identity, and coming to terms with your identity. It exposes this theme quite literally, in the fact that Don Draper is not who he says he is; he is Dick Whitman, and after a turn of events in the Korean War, he assumes the identity of a fallen comrade, Don Draper – the real Don Draper. This matter is a source of drama in the early seasons, but this idea of identity continues to be pervasive throughout the whole series, and not just for Don Draper; it overshadows every character in whichever ‘role’ they play.

Consider Bert, the sage individual who sits as a founding partner in Sterling Cooper – as well as Sterling Cooper’s many other guises throughout the programme – and his response to this revelation: "The Japanese have a saying: a man is whatever room he is in, and right now Donald Draper is in this room". This is characteristically Bert, who provides a voice of calm and reason throughout the show. It lets Don off the hook, but it exposes the great idealogical battle in this programme: do our past actions define us, or don’t they? Don leads a double life literally, but many of the other characters have double lives in one way or another. The older characters are of the age to have fought in World War II, and the joys and comradeship, as well as fear and prejudice, continue to bubble under the surface of their characters and guide their action.

No character exudes this more than Roger Sterling, the great wit and charmer of the series, brilliantly played by John Slattery. Sterling is a philanderer as well; a drinker, twice divorced, wealthy, insecure – not unusual traits to find in the men which inhabit the world of Mad Men. His memories of the War are fond; and despite his inexorable charm towards clients, he stands firm on rejecting the business of Honda, a Japanese company, on the basis of his fallen allies. He cannot forget who he was then, and who he still is today. The partnership status, the reputation, the money and ‘the room’ have a limited effect on who Roger Sterling is at his core. So while Bert’s words of wisdom provide a soothing balm to the viewer and to Donald Draper, we know it can only be temporary, and whatever Don has left in his past will have to be confronted for true catharsis. “for the past is never dead. It’s not even past” (I will never pass up an opportunity to use this quote).

For men of Roger’s generation this era sits in stark contrast to the horrors of war, and this provides a nice interplay between the two periods. But the beauty of the 1960′s setting – apart from the sublime aesthetics, which I will deal with later – is that each societal role was in a state of flux. It was an era of great cultural, social and political change in America. As such, the evolution in the identities of blacks, gays, hippies and women – and all other outliers in mid-century America – is traced with sensitivity throughout the programme; and even if the evolution traced is more a regression, the show has the ability to make you empathise fully with these outliers, and reveal the prejudice as both horribly old-fashioned and deeply offensive. One character who struggles against the misogyny of this era is Joan Harris, whose femininity is frequently alluded to by the men in the office, or in one important moment, used by the office to court commercial favour. She is a sad character. For all her business savvy, she will never be taken seriously. This sad realisation is captured towards the end of the series, after another callous sexual advance by a superior, and we the audience are just as exasperated as her. The 1960′s was, of course, the defining era for free-love and liberal progress, but at the same time it was still a world ultimately ran by Roger Sterling’s and Don Draper’s. The clash between these two worlds fuels a lot of the drama in this programme, and exposes many of the attitudes of the time as flawed.

Towards the end of the series one could feel jaded with the choices of Don Draper. He consistently cheats on whomever he’s with at the time; he drinks himself into a stupor regularly, and even brings down other characters with him (on this point there are too many to name, but two that stick with me are Ted Shaw and Lane Price); and finally, his credentials as an ad man are tested when his creativity seems to be dwindling. He starts out as an enigmatic, charming character, and at the end he is pitiful. As difficult as it was to watch, this was necessary. You need to feel contempt for these characters, and unfortunately this requires repetition and a certain affection for the other people he harms. Only then do you feel the weight of his personality disorders, of which there are many, and the frustration. He gives his car to a young boy whom he sees himself in in the final episodes: “Don’t waste this”. The mask is slipping, as the mistakes of Don Draper at last take their toll. This life of excess can satisfy no longer, and he goes to California, where his life as Don Draper began, for closure.

The final scene is deeply satisfying; Don is sitting down on the grass, with a number of other lost souls, at a retreat in California. It is a moment of peace after a traumatic day of owning up to his actions to the important women of his life (on the phone with Peggy and Betty). His job is as good as gone, and his life in New York a distant memory. In this moment of calm there is a slight smile, and the screen cuts to a coke advert – apparently one of the most successful ads of all time – as a bunch of hippy types, of all races, sing with a bottle of Coke. It’s Don’s ad. In this moment of tranquility and genuine bliss, his thought is how to commodify it for Coke. At his core he’s an ad man, and it’s this which can give his life a purpose. All the excess and debauchery was, hopefully, just a poor coping strategy for a traumatic childhood.

I think that is basically the sum of the programme. There are endless character arcs to choose but ultimately the people in this show are looking for meaning and purpose and demand the right to find this meaning on their own terms, and down whichever avenue they choose. No one gets killed, there is little melodrama outside the necessary amount for a TV show which needs people to tune in every week. It’s simply a series which confronts and displays the true drama of our personal and working lives. For this alone, it is worth watching.

N.B. From grand themes such as identity and meaning, it feels almost shallow to discuss the design of Mad Men, but this is an important part of its appeal. The sets are large and ooze that 1960′s cool. The apartments; the furniture, the cars, the suits, the restaurants; there is meticulous attention to detail ensuring the illusion of 1960′s New York is not broken. More than that, the design and textures of the interiors tell you a lot about each character. Roger Sterling has a monochrome office in later seasons which notably more thought out than others in the office. It suggests more of an interest in the luxury of the business than the business itself. Similarly, when the team leaves for McCann at the end the corridors are dark, tight and suffocating; the direct opposite of the light and airy space of Sterling Cooper, and a subliminal reminder of the enormity of McCann and the oppression of the new takeover. Overall, it’s a charming and beautiful world to spend 50 minutes in.

8/09/19

1 note

·

View note

Link

Hi, folks, Rose here. ^_^ I’ve got two previews for you from the Storytelling chapter of Changeling: The Lost! Plus, come see us at Gen Con!

Changeling and Gen Con

Onyx Path will be at Gen Con in booth #145. If you stop by, I’d be happy to talk Changeling, as well as show you the pre-layout manuscript for the book.

We’ll also be running a “What’s Up With White Wolf RPGs?” panel at 11 AM Friday in Pennsylvania Station C, at the Crowne Plaza hotel. We’ll be talking about Changeling there, as well as Changeling-related projects like Dark Eras and a certain crossover book.

(Note: Due to the con, I’ll likely be less available on forums and our social media. Questions about today’s preview may need to wait for next week.)

Storytelling

Changeling‘s Storytelling chapter focuses on the chronicle as a collaboration between the Storyteller and all of the players. Today, I’d like to present two sections from that chapter, written by Jacqueline Bryk.

The first section is on chronicle building, featuring a system for tying together the human and supernatural elements of your game, and a series of questions to help you build an engaging group of characters.

The second is something we haven’t done much of in previous Chronicles of Darkness books: safety techniques. I don’t think it’ll surprise anybody when I say Changeling can get pretty dark. It’s a horror game that can evoke abuse and trauma, which are very real for all too many of us.

Some groups may want to avoid those elements, and some groups may want to dive as deep into them as possible. In my experience, most groups are somewhere in between: they want to explore the dark parts of the game, but don’t want to hurt the players behind the characters.

To that end, we present some discussion of the issues involved in running a Changeling game, as well as an overview of safety techniques that you can use at your table to make play an involving, but not harmful, experience.

In addition to these previews, the Storytelling chapter also covers how to build kiths, courts, Contracts, and Mantles.

Enjoy!

Building Your Chronicle

A chronicle is the tale told by the Storyteller and the players, spun out in threads of gossamer and tears. It’s the story of the player characters, their triumphs and failures, their escape from the Fae and their attempts to start a new life in a world that no longer recognizes them. While the Storyteller controls the world around the characters, it is their story. Players need to have input into designing the plots and problems their characters face throughout the chronicle. If the players all built social butterflies and the Storyteller’s chronicle is a combat-heavy slugfest, no one is going to have fun.

To build a chronicle, you first need to consider your props and themes. Once you’re finished with this part, you can move onto the Hedge Paths.

Themes

Themes are the human dramas that make your chronicle compelling. The overarching themes of Changeling: The Lost are beauty/agony, clarity/madness, and lost/found. In the tension between the opposites, one finds the game. Naturally, these aren’t going to be the only things you’ll explore — the Lost have to deal with very mundane issues in addition to being in the liminal space between humanity and Fae. Themes like “lost love,” “poverty,” and “hunger” could all work in a Changeling chronicle. Each might mean a very different thing to each character. “Loyalty,” for example, could mean protecting one’s freehold, sheltering one’s family even when they no longer claim them as kin, or hiding one’s undying fealty to one’s undying master in Arcadia.

Props

Props are the more fae parts of your chronicle, the magical weirdness that surrounds and permeates the lives of the Lost. Set pieces, scenes, and objects all fall under the heading of props. Anything from the Goblin <arkets to a specific token to a blue rose that only grows in the wall of a specific frozen Arcadian garden can be a prop.

Props can also be more mundane objects that show up throughout the chronicle. A player might choose to have her Bright One character associated with torches, for example, so any scene that revolves around her includes candles or flashlights or other small sources of bright light. Grand Princess Caesura, a lady of the Gentry who appears as a feminine form made of the absence of matter, is associated with open doors and missing keys.

Props don’t just have to be objects, either. Anything that will strongly influence the story can be a prop. A family curse, a bargain ill-made, a portal torn open, or a monarch corrupted by their own power can all be used as props. Really let your imagination run wild here — that’s what Changeling is all about, after all.

Using Props and Themes

When brainstorming your props and themes, note each one on a sticky note or a notecard. By the time you’re finished, you should have roughly one theme and one prop per player character. If there are more, that’s fine, those can be set aside as part of the secondary themes and props for the chronicle.

Lay the themes in a row on a table, then lay the props in a column perpendicular to the themes. For the intersection of each theme and prop, the players should choose a character. Ideally, this is a player character — an Ogre Gristlegrinder bouncer at the intersection of “hunger” and “the goblin market,” for example, or the Bright One above at the intersection of “torches” and “descent.” As a storyteller, this lets you know what sort of character-specific experience your players are looking for.

Free spaces are reserved for Storyteller characters. The intersection of “hunger” and “torches” might be a Huntsman coming after the player characters. Players and the Storyteller should work together to create compelling Storyteller characters that can come into the characters’ lives with some degree of commonality already established so that they better suit the overall aesthetic and feel of the chronicle.

Hedge Paths

A changeling doesn’t come into being in a vacuum. She has family, friends, a life she was pulled from, and a life she’s building. It’s important that both the Storyteller and the players know what’s going on with the troupe’s characters before the chronicle begins — otherwise they’re as lost as an escapee in the Hedge. Following the stages below will help you build well-rounded characters and connect them to the game.

The Life Before

All changelings were human before they were taken by their Keepers. Fae politics pale in comparison to the networks of family, friends, acquaintances, coworkers, petty rivalries, romances, and other connections mortal humans have on Earth. Rare is the Lost who was taken without any sort of link to other people — otherwise, why would the Fae need to make fetches?

Decide who the changeling was before they were spirited away by UFOs or invisible horses. Ideally, this should include their occupation, their home life, and any important people they may be in a relationship of any kind with. It can also include the age they were taken, any identifying marks (tattoos, moles, scars, etc.) and anything else especially relevant to their mortal life.

Example: Ben decides that his changeling character was an ESL teacher in her mortal life. He names her Jocelyn and gives her a husband but no children, a house that they rent together, a book club that meets on Sundays, and a best friend who recently moved two cities away. She has just graduated with her Master’s degree and she is a friendly, if private, person. Ben decides to put Jocelyn’s husband, David, at the intersection of a prop and a theme, “ancient books” and “unconditional love.”

Sarah decides that her character was a college student by the name of Nate. He grew up in a loving, middle-class nuclear family that hunted and cooked together and encouraged his dreams pretty regularly. Nate does not have a significant other and does not particularly want one right now. He lives in the university dorms, has a close group of friends, and enjoys target shooting and knitting equally. Sarah writes down “favorite rifle” as a prop and “growing up too fast” as a theme. She places his soon-to-be court monarch, Mens Machinae, at the intersection of these elements.

Meg decides that her character, Holly Blue, was raised in a hippie commune out in the Pacific Northwest. Her upbringing very much followed the old adage “it takes a village to raise a child” and she remembers her childhood as a time of love and warmth. Holly Blue was homeschooled until she went to college. She took a year off after her junior year to try and find out what she really wanted out of life, and went on a road trip across the U.S. with some friends. Meg writes a prop, “the old car that should have stopped working” and decides to place Holly Blue’s best friend, Nevaeh, at the intersection of that prop and the theme “unconditional love.”

Emily’s character is named Hel, and is the youngest member of a large family. She lived with her divorced mother and only really saw her father on holidays. Emotional honesty was not really prized in her household, so her upbringing was comfortable, if a bit chilly. Hel got her Master’s in Computer Science and worked as a programmer at NASA. She had several partners, but was going through a divorce of her own due to finding the same coldness in her husband as she did in her mother.

Questions to Ask: What is your name? How old are you?

Did you grow up in a nuclear family? Are your parents still together? Divorced? Never married? Single-parent household?

Were you wealthy? Middle class? Poor?

What’s your gender? Does it match your presentation? Are you okay with that? What’s your sexual orientation? Who knows? Did you have a partner — or several?

Did you graduate university? Do you have more than one degree?

What was your occupation? Where were you living? Were you owning, renting, couch surfing, or squatting? Did you have a pet? More than one?

Did you have any identifying marks, like tattoos or scarification? What were your hobbies and pastimes? Who would notice if you were gone or acting strangely?

Promises: What was the biggest promise you made before you were taken?

Sidebar: A Note on Backstory

It is expected that the Storyteller will use her players’ backstories to enrich the play experience. While they should feel free to do so, players should also communicate with the Storyteller on things they would like left untouched — and, by the same token, things they would like messed with. Storyteller torture of characters via backstory should always be consensual. This is a game, after all.

The Capture

Something had to get that changeling into the Hedge into the first place. Something had to take her to Arcadia. Something had to lock her into shackles of bronze and roses, forcing her to do its bidding. Use this section to figure out how the changeling was stolen or seduced away. You may also use it to get a preliminary outline of her Keeper.

Example: Jocelyn is levelheaded and skeptical of offers that seem too good to be true (she might not have gotten through her Master’s program otherwise), so Ben decides she didn’t make a Faustian bargain. It’s unlikely that she was seduced, so he decides that she was kidnapped and dragged through a mirror while in the bathroom at a Halloween party. He places her Keeper at the intersection of a prop and a theme, “unexpected portals” and “not who they seem.”

Sarah decides that Nate was on a hunt with his family when he got separated in pursuit of a buck. At least, he thought it was a buck. He saw a flawless rack of horns flash through the dusk in the trees and followed it. The woods got thicker and gloomier, but that’s ok, he’s used to having to wait in thickets to get at his game. Nate lost sight of the buck and turned around to go home — only to find the buck and the buck’s master waiting for him. Sarah decides to place the buck that lured him in at the intersection of the prop “the hunters hunted” and “not who they seem”.

Meg likes the idea of Holly Blue being abducted on her road trip. As she and Nevaeh drive along I-80, they see an old woman at her fruit and honey store — really, little more than a shack. They decide to stop to purchase some food. Holly Blue strikes up a conversation with the proprietor, who offers to show her some of her fresher offerings. Holly Blue follows her around the back, only to find herself in the thorns. The woman is a privateer, and she’s taking her newest acquisition to Grandmother, Grandmother (see p. XX) to adopt.

Emily comes into the chronicle a bit later than everyone else, and so her character’s abduction has to be a little different than everyone else’s. She decides that, befitting a programmer at NASA, Hel is abducted by the Three Androgynes (see pg. XX). It’s somewhat unceremonious — one moment she’s walking home from work, and the next, she’s suspended in midair in a sterile room, her limbs and mouth bound by thorns.

Questions to Ask: Were you physically dragged off? Were you deceived?

Did you offend a True Fae somehow?

Did you misstep into the Hedge?

Where were you when you were taken? What do you remember of the journey?

Promises: What promise was made to you while you were en route?

In Durance Vile

The durance is the period of a changeling’s life that shapes their biggest challenges. In a twist of cruel irony, some changelings barely remember it except in nightmares, while others are always on the verge of a flashback or panic attack, seeing their Keeper and her knives around every corner. Most are somewhere in between. Trauma is a funny thing, and for many Lost, it remains safely locked in the back of their minds, slipping out at moments of tension or vulnerability. The durance determines the kith and seeming of the changeling, and may affect what court they choose to join later.

Don’t hold back in this section (at least within limits set by the group, see “Safe Hearth, Safe Table” on p. XX). True Fae are not known for mercy or obeying the laws of physics. How might a True Fae have caused you to turn into a Mirrorskin or a Helldiver? What fell pacts were made with the realm you were imprisoned in that you could survive it? Were you the only one in your motley there?

Storytellers should feel free to do some light narration of this section before game, if their players are so inclined. See the sidebar “Narrating a Durance” for some guidelines on how to do so effectively.

Example: Jocelyn is taken to a realm of mind-numbing bureaucracy and byzantine laws. She is held in a small cell, a room that looks like an unfurnished apartment with the drywall torn out and the wires exposed, until her Keeper sends someone for her. She is taken before the True Fae, a being made entirely of paperwork and red tape. Its face is a white porcelain mask made to look like a baby’s head. Ben has already decided that Jocelyn will be a Fairest Notary, so he states that after being forced to swear fealty (in triplicate!), she is taken downstairs and has the pledge tattooed on her back by another changeling. Her Keeper, the Munificent Bureaucrat, and another True Fae watch. She is leashed and kept at her Keeper’s side to reference at will.

Sarah decides that her Ogre Artist character, Nate, was the one to tattoo Jocelyn’s back at their Keeper’s behest. Nate was taken a year before Jocelyn, and has been forced into his role as artisan of all trades. Not an artist before his durance, Nate was quick to pick up skills in order to avoid harsh punishments with chisels and pigment. He has been forced to reshape other changelings into different forms and configurations, and already he’s growing slowly deaf to their cries, for his own sanity.

Holly Blue, meanwhile, is chosen as Grandmother, Grandmother’s hardworking middle child who doesn’t get enough attention. This is not her normal state of being. She is used to love and affection from all of those around her, and is now constantly ignored and occasionally violently punished for the mischief of other changelings. She finds herself occasionally changing her voice or facial expression and sometimes outright lying to avoid Grandmother, Grandmother’s teeth and claws. Soon, she’s doing it all the time. She uses the voice and face that will keep her most safe, and in this way, Holly Blue becomes a Fairest Mirrorskin.

Hel doesn’t get much of a choice in her durance. She is kept in a zoo of changelings, occasionally taken out and vivisected and put back together again. Sometimes, she’s shown off, paraded in front of the Three Androgynes’ guests like a prized pet. She is not, however, petted and coddled like some of the others, and is subjected to an increasing parade of indignities. Her cell is immersed in the light of strange stars, and in her anger and humiliation, she begins to absorb the light as a source of comfort, becoming an Elemental Bright One.

Questions to Ask: Who is your Keeper? What is their title, or titles? How did they treat you?

What was the lightest part of your durance? The worst? The very worst? Were other members of your motley there, or was it just you?

What was the environment like? Were you mostly inside or outside? Was it hot, cold, or temperate?

What was the last straw?

Promises: What did you have to promise your Keeper to avoid punishment?

Sidebar: Narrating a Durance

If the players choose to play out their durance instead of merely having it as part of their backstory, the Storyteller should carefully consider how to carry it out. The durance is characterized by loss of autonomy, both bodily and spiritual. While the character loses their autonomy, the player should never lose hers. A durance is not an excuse for a Storyteller to torture her players outside of the boundaries of the game in the name of story. The player must always have a say in what happens in her durance. If possible, durances should be narrated in private (this can be done in text form, if that’s easier). Nothing makes a player feel more vulnerable and disrespected than playing out an intense scene, only for another player to interrupt with a joke or an off-color comment about what’s going on.

Decide between the Storyteller and the player what the character’s durance should focus on. A Bright One’s durance is probably not going to involve toiling in the mines, but she might light the way for Helldivers and Gristlegrinders instead. An Ogre is less likely than a Fairest or Darkling to be the lover of the Princess of the Red Crowns, but he might hold her lovers still while she whispers to them and lines up the hats to nail onto their heads.

The Storyteller should take careful note of what the player wants. The durance can be extremely disturbing and upsetting, and it’s important that the player is only disturbed or upset in the ways she wants to be. At any point, the Storyteller or player should be allowed to tap out or fade to black if the scene become too much for them. There’s no rush to tell the story of the durance. Suffering has no deadline.

The Escape

Some part of the enslaved changeling felt the call back to Earth. Perhaps it was the memory of their spouse’s laughter or the warmth in their chest when they held their child for the first time. It might even be a petty vendetta against a coworker left unsettled. Not all human memories are noble or loving, and that’s not the point. Memories of the mortal world are the changeling’s key out of Faerie, so if they have no memories of the world as it is now, they may not be able to make it back.

What was strong enough to bring the character back? This is the paramount question for this section. Even if none of the other questions are answered, the player should know the answer to this one. It’s a good indication of the changeling’s priorities later in the chronicle.

Example: Jocelyn’s memories of her husband and her studies see her through her durance. While reading some of the Munificent Bureaucrat’s paperwork, she finds a loophole inside of a subclause that would allow her to escape. Armed with this knowledge, she unlocks the collar around her neck and sets herself free.

Meanwhile, Nate the Artist is drawn back by thoughts of his friends and his hunts with his family. He creates a perfect likeness of himself, a statue that smiles, and flees. Nate and Jocelyn meet up in the massive air ducts of the domain, quite by accident, and agree to leave together. They both tear through the thorns of the Hedge, seeking a door to lead them home.

Holly Blue has been forced to sacrifice her emotional honesty and her happiness to survive. She is whatever Grandmother, Grandmother wants her to be, and she has not been cut in months. However, she has not forgotten Nevaeh, her best friend and latent crush. When her Keeper leaves to seal a pledge with another Kindly One, she flees through the forest she was told never to enter. The thorns open for her, and she finds herself back in the Hedge, seeking a way back to the fruit stand where she lost herself.

Finally, Hel has been subjected to one indignity too many. As the Three Androgynes bring her back to the operating theater for another procedure, she breaks free, blinding all three of them with the light of her rage. She flees down the infinite halls of their ship, and finds an escape shuttle docked in one of the many cargo bays. Her programming skills are barely a match for the byzantine controls of the shuttle, but she manages to hotwire it and flies out of the Androgynes’ massive ship. Just as she begins to despair of finding her way back to Earth, she crash-lands in the thorns, the nose of the shuttle poking out into the Air and Space Museum in D.C.

Questions to Ask: What was strong enough to bring you back?

Did you sneak out? Fight your way out? Make a bet with your Keeper? Did you not want to leave? Were you thrown out instead?

Did anyone else come with you? Did you have to leave anyone else behind?

What do you remember of your journey back? What were you searching for on your way through the thorns?

Promises: Who knew you got out? Who came with you, and who stayed behind and promised to cover your escape?

Home, But Briefly

The great tragedy of a changeling’s life is that she is forever displaced from what it used to be. Fetches take their place and families move on. Any encounter with former friends and loved ones will result in confusion — and that’s just the best-case scenario. Lost may show up thousands of miles away from their home, drawn by a memory of a favorite vacation or a proposal on a beach, or they may emerge gasping from the thorns 20 years after they were abducted — though only an hour passed in Faerie. For a newly freed slave of the Fae, this is a punch in the gut. Where will they belong? Will they ever belong?

Example: Jocelyn and Nate arrive on Earth, pulled by their shared memories of the university they attended. Jocelyn has been in Faerie for what seems like a decade — but only a week has passed on Earth. Nate has been in the clutches of the Munificent Bureaucrat for much longer, and doesn’t recognize the new buildings on campus.

They go to find Jocelyn’s husband, only to find out that he has never missed her — she’s taking a shower right now. Jocelyn desperately tries to appeal to her husband, who threatens to call the police. Nate’s family found him dead, accidentally shot by another hunter’s bullet. They’ve already mourned and buried him, and when he shows up, they accuse him of being an imposter and making fun of them. Neither family will take them in. Defeated, Jocelyn and Nate retreat to a nearby diner to grieve and figure out what’s next.

Holly Blue arrives on Earth, only to find that her friend left the stall and its nighttime in the dead of winter. Using the skills she’s learned in Faerie, she steals the visage of the privateer who stole her away, and with it, her car and wallet. Meg decides to put the privateer under “the old car that should have stopped working” and “this is mine now.” Holly Blue decides to drive out east, in the direction her friend went, hoping to discover a police report about her disappearance. However, she soon discovers that Nevaeh is not only back home, she is dating a creature with Holly Blue’s face, who had the courage to say to Nevaeh what Holly Blue herself did not. They’re getting handfasted this spring. Holly Blue finds herself alone in a university town out east, sobbing alone at a computer in a public library, unsure of what to do next.

Hel attempts to get back into the NASA headquarters at Two Independence Square, but she’s already working there. Or at least, someone wearing her face has just been fired from her job there. Hel’s clearance is deactivated and she finds herself stranded. Her partners all believe she’s gotten back with her husband and refuse to accept this new impostor, doing everything from slamming the door in her face to threatening restraining orders. She buys the ticket for the first bus she sees, determined not to panic.

Questions to Ask: Who do you seek first?

Are they still alive? Do they remember you?

Do you have a fetch? Where are they? How have they replaced you, or changed your life in a way you didn’t want?

How has your fetch lived your life in your absence? Do they know you’re there?

Promises: What promise did your fetch break to someone you love?

Freeholds and Courts

Unless the game starts with the capture and durance of the player characters, much of any given Changeling: The Lost chronicle will take place in and around the local freehold or freeholds. If any of the props and themes from earlier have gone unused, use them here. The courts of the local freehold are a key part of the story, and need to be fleshed out. The easiest way to do this is to set up the four Seasonal Courts, but see later in this chapter for guidance on building your own.

Unless a player character is beginning the game at the head of a court, creating the four seasonal kings, queens, or monarchs is a good first step. It’s easy enough to put an Ogre Bright One in charge of Summer, and definitely a good choice. However, what would it mean for a small, vulpine Darkling Hunterheart or a Wizened Artist to hold the same position? The monarchs say a lot about the local courts — and, by extension, the tone and symbolism of the chronicle itself. A Spring Court led by a Fairest Playmate is going to have a very different outlook and aesthetic than another freehold with an Elemental Snowskin Spring King.

Once the Monarchs are decided, the players can pick which courts they might have reasonably been convinced to join.

Example: Ben and Sarah decide to divide the courts between them. Ben takes Winter and Summer, and Sarah takes Autumn and Spring.

Ben decides that the Monarch of Winter is a gender-neutral Darkling Artist who goes by Mens Machinae and makes robots and animatronics — and clever constructs to fool the Fae. The Queen of Summer is a Wizened Chatelaine named Small Queen Jane. He decides that she got her position for her ability to command groups and plan tactical engagements, and not necessarily for her own personal puissance.

Sarah, meanwhile, decides that the head of Spring is an Ogre Helldiver who goes by ghost (the G is never capitalized). ghost prefers no titles or accolades; they merely serve and stay silent until needed. The King of Autumn is a jovial Elemental Hunterheart who has an extremely even temper until his people are threatened — and then he turns into a terrifying force of nature, using illusions and threats and dreams to keep the freehold safe.

After looking at their monarchs, Ben decides that Jocelyn became a member of the Winter Court. Sarah instead decides that Nate is courtless, but sympathizes with Autumn.

Meg joined the chronicle a little later, so she doesn’t assist in creating the courts. However, she decides that Holly Blue has joined the Spring Court, in search of a balm for her broken heart. She was personally recruited by a ghost after they found her sleeping in a tent at a local cemetery. That’s where she meets Jocelyn and Nate.

Emily also joined the chronicle late, so she has no hand in creating the courts. Hel decides to join the Summer Court after they put her in protective custody for blinding a local bartender after he hit on her. The Season of Wrath best suits her slow-burning anger after being constantly disregarded, humiliated, and torn apart at other’s whims.

Questions to Ask: Who is the head of your Spring/Summer/Autumn/Winter Court? Why do they have that position?

Are there any other prominent figures in that court?

Why did you choose to join that court?

Where is the freehold located? What is it called?

Promises: What oath of fealty did you swear to your court, and how is it similar to the one you were forced to swear to your Keeper?

A Motley Crew

The motley is the core unit of changeling society, a chosen family that reaches beyond boundaries of seeming, kith, and court. Player characters are usually in a motley together and their connection should be one of the major focuses of the chronicle. Ideally, members of a motley are willing to face death for each other — but it could just as easily be a group of drinking buddies who fear being alone.

Example: Jocelyn and Nate have been through a lot together. From killing Jocelyn’s fetch with a car to showcasing Nate’s latest project at a meeting of two freeholds, they’ve supported each other through thick and thin. After they picked up Holly Blue and Hel, who are more recent escapees from the same realm, they form a motley of four. The freehold calls on them when they need delicate legal matters handled, or an important guest impressed. Unsaid, but also just as true: They are the first line of defense when they True Fae come a-knocking.

Questions to Ask: What drew you to each other?

Who is the leader, if anyone? Are any of you likely to betray the others?

Does your motley have a name? What is your common goal?

How do others in the freehold view your group? How do you view your group?

Promises: What pledge did you all make each other? How was it different from the one you were forced to swear to your Keeper? What was the pledge sworn on?

Sample Chronicle: The Blue Hen Motley

Jocelyn, Nate, Holly Blue, and Hel are all from very different backgrounds, but they all wound up in the same place. They decide to retrace Holly Blue’s road trip back to the Pacific Northwest in order to stop her fetch’s wedding to her unrequited love, Nevaeh. Along the way, they decide to stop to take out Hel’s fetch — except Hel decides to make a pledge with her fetch to not interfere in each other’s lives. Jocelyn oversees the pledge. This frees up Hel to continue on the journey. Nate and Jocelyn take out the privateer on I-80 while Holly Blue watches and smiles her inscrutable smile. Hel’s pledge gives the motley enough points of Glamour to speed up the trip, but their Keepers are all looking for their escaped slaves. The Blue Hen Motley now has to deal with Huntsmen while trying to make it in time for Holly Blue to confess her love…

Other Bonds

Many promises and connections could fit into any of the stages listed above, but aren’t tied to a specific one. Since they’re useful for fleshing out a player character, some examples of other, more general ties are listed below.

What is your single biggest regret?

When did you find true love and why was the form it took unexpected?

Who did you leave behind?

Who do you hate even more than your Keeper?

Why does one person in particular fascinate you?

Who do you dream about, then wake up shaking and sweating?

Safe Hearth, Safe Table

While it’s fun to play make believe with friends, Changeling: The Lost is, at its heart, a horror game. True, it is also funny and beautiful and wondrous — but that typically comes after being held against your will in a world of dreams and nightmares for months, years, or decades. Changelings may have their bodies altered and their minds played with. Personal autonomy is repeatedly violated by godlike entities to whom one cannot simply say “no.” The only way to make it stop is to escape and even then, that’s not a guarantee. The Gentry might find you eventually, or they might send someone to do it for them.

This can be extremely unsettling for players. While consensual fear is part of the game, the goal is not to traumatize the players outside of the play space. Rather, everyone should strive for a game that provides an engaging, terrifying, and beautiful story that gives everyone involved the sort of pleasant chills a really good horror movie leaves the audience with after the credits roll. Even if a character feels trapped and hopeless, the player should never feel the same way at the table. This is a game, after all.

What follows are some safety techniques to help both Storytellers and players maximize enjoyment without taking away any of the horror at the heart of Changeling: The Lost. Feel free to use none, some, or all of them.

Emotional Bleed

Many of the safety techniques talk about something being too uncomfortable or too intense “in a bad way.” This is for clarity of communication. Some players like being made uncomfortable or put into extremely emotionally intense situations. Such players may play horror games to cry or feel trapped as a sort of catharsis, a way to experience traumatic emotions in a low-consequence environment.

This is called emotional bleed, or just bleed for short. When a character experiences emotions the player is experiencing, that’s called bleed-in. Contrastingly, when a player experiences the emotions her character is feeling, that’s called bleed-out. Bleed itself is not bad, but it can sometimes be unpleasant for a player who wasn’t expecting it or didn’t want it. If a player is getting unreasonably frustrated or upset at a challenging circumstance, this could be a sign of bleed. Stop play and give everyone a breather before continuing if bleed begins to cause problems at your table. Bleed can absolutely enhance the play experience and add another dimension of emotional resonance, but only if everyone is on board. Check ins, occasional snack breaks, and use of the safety techniques in this chapter are extremely helpful if the table is experiencing high amounts of bleed.

Lines and Veils

A classic safety technique originally described by Ron Edwards, Lines and Veils allows players to pick and choose what they want to address in the chronicle. Before game, the Storyteller should prepare two sheets of paper. Label one “Lines” and the other “Veils.” Lines are things that will absolutely not be touched on in the chronicle, not even mentioned in passing. Veils are things that can happen, but will not be played out, and instead addressed with a “fade to black.” The Storyteller asks players what they’d like added to the lists, and notes that the lists can be edited at any time. Veils can be moved to Lines, Lines can be moved to Veils, new Veils or Lines can be added, or Veils or Lines can be taken away (with the consensus of the other players). Veils and Lines cannot be used to cut out antagonists (i.e. “I don’t want the True Fae to be a part of this chronicle at all, not even mentioned in passing”) but can be used to restrict antagonists’ actions that might be uncomfortable for some players (i.e. “I do not want the True Fae in this chronicle to use sexual violence”).

Common Lines: Sexual violence, explicit depiction of torture, force feeding, starvation, mutilation, racial slurs, gender-specific slurs, spiders, trypophobia-inducing imagery, needles, bestiality, explicit depiction of bodily functions

Common Veils: Explicit depiction of consensual sexual activity, torture, emotional abuse, physical abuse, body horror, human experimentation, dream or nightmare sequences, childhood memories, prophetic visions

Fade to Black

In a movie, when the hero is just about to get into bed with her love interest or be “forcibly interrogated,” sometimes the camera cuts away right before the action — occasionally with a moan or a scream included as appropriate. This technique is called “fade to black,” and can be used in your chronicle as appropriate. If you don’t want to narrate every caress of a love scene or the weirdness of a changeling’s personal nightmare or the agony of Faerie torments, simply fade to black and focus on another scene. A player can also request a fade to black if they are uncomfortable with what is happening at the table.

The Stoplight System

This is a relatively recent technique and was pioneered by the group Games to Gather. The Storyteller lays out three different colored circles on the table: red, yellow, and green. Each color indicates a response to different levels of intensity. Green means “yes, I am okay with and encourage the scene getting more intense.” Yellow means “the scene is fine at the intensity level it is now, and I would like it to stay here if possible.” Red means “the scene is too intense for me in a bad way and I need it to decrease or I need to tap out.” Players can tap the colored circles as appropriate to indicate to the Storyteller what they want or need at that moment.

The Storyteller can also use the stoplight system to ask the players if they’d like intensity increased or decreased as necessary without breaking the narrative flow. To do so, the Storyteller can repeatedly tap a color — green for “more intense,” yellow for “keep it here,” and red for “do you need me to stop?” The players can then touch a color in response. Players can also respond by saying the color in question out loud.

The X Card

An up-and-coming technique, especially in storytelling-game circles, the X card was designed by John Stavropolous. The X card is fairly self-explanatory. A card or sheet of paper with an “X” drawn on it is placed in the middle of the table. At any point, a player or the Storyteller may touch the X card to call a halt to any action currently making them uncomfortable in a bad way. If they would like to explain themselves, they may, but it is absolutely not necessary and the Storyteller should continue play once everyone is settled back in.

The Door Is Always Open

This is another technique that needs very little explanation. If a player needs to stop play for any reason, they are free to do so after giving the Storyteller a heads up. The chapter (game session) is then on pause until that player either returns or leaves the premises. Storytellers should use this technique either in conjunction with other techniques, or during sessions where players may have to leave abruptly for personal reasons.

Debriefing

Debriefing is a post-game safety technique, and can be used along with any and all of the suggestions above. After the chapter is finished, the Storyteller asks the players to put away their character sheets and take some deep breaths. Soft music or snacks can also be used to assist in debriefing. Slipping into character is easy — slipping out can be a little less so. Debriefing is all about bringing the players back to the real world, back through the thorny maze of the chronicle they created with the Storyteller.