#u don’t like. put a moon in orbit and it not effect the oceans

Text

what gets me sometimes w the idea of the calamity is that there are probably places in the deserts of thanalan where the fire of bahamut turned the sand to glass and it’s just. a few handfuls of sand there are layers of glass

#like eyrie hears about prospector types in southern thanalan#and might have gone on a few ventures to keep them safe in the desert#and hearing about and seeing these layers of glass in the sand#like that sort of stuff is what messes with their head the most after the calamity#these bits and pieces of the mundane of life that have been so utterly changed#coerthas and its people are the starkest of the bunch but in the city states it’s these small things#the parts of the shroud that are so twisted and gnarled as the elementals cannot heal some of these hurts#how the wind and the water and the creatures of the area are. wrong and off#eyrie has been to western shroud only a few times and they have regretted it each time#gnarled ugly things live in that dirt#the debris in the oceans around La noscea#how it changed the landscape of the oceans. the tides and patterns changing now that a moon is gone#u don’t like. put a moon in orbit and it not effect the oceans#how many dead fish and other sea life washed ashore. the heaps of death#tainted and unable to be consumed. fires for burning these dead fish#pyres for the dead sahagin that washed ashore#idk I think about the damage to the people of Eorzea—the emotional and mental#but the ecological damage#like. if eyrie had the gumption to write a thesis for the studium#which would be a very rare chance since they would much rather write a book for the masses to have access to#but it would be a compiling of their offhanded ecological and human responses to the calamity#that push and pull between them#as someone with a vague familial connection to what thrived in the earth of their home ie. akin to elementals#it’s puzzling to them

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday’s Super Blood Wolf Moon Eclipse Explained, and Venus Kisses Jupiter in the Morning!

(Above: Michael Watson of Toronto is an avid moon and eclipse imager. He captured the April 15, 2014 total lunar eclipse and assembled this beautiful composite that clearly shows Earth’s circular shadow.)

Hello, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 20th, 2019 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeoguy.tumblr.com/ where all the old editions are archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. Please click this MailChimp link to subscribe to these emails. If you are a teacher or group leader interested joining me on a guided field trip to York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory or the David Dunlap Observatory, visit www.astrogeo.ca.

I can bring my Digital Starlab inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, visit DiscoveryPlanitarium.com and request me. We’ll tour the Universe together!

My latest column for Space.com talks about using astronomy apps to enjoy Sunday night’s total lunar eclipse. You can find it here.

(Above: Once the moon wanes and rises later towards the end of this week, enjoy the sights of the Winter Milky Way, which rises through Canis Major, Monoceros, Orion, Gemini, and Auriga.)

Public Astro-Events

If skies are clear on Sunday night, January 20, starting at 10 pm, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory will host a free public viewing session for the total lunar eclipse on top of the Arboretum Parking Garage. Parking charges will apply. Details are here.

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party - broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes. If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Details are here.

On Friday, January 25 from 6 to 7 pm, the Royal Ontario Museum and the Canadian space Agency will hold a free session entitled Getting to Know Bennu: Updates on the OSIRIS-REx Asteroid Sample-Return Mission. It will be held in the ROM in the Signy and Cléophée Eaton Theatre, Level 1B. Details and registration is here.

On Saturday, January 26, starting at 7 pm, U of T’s AstroTour will present their free planetarium show entitled Grand Tour of the Cosmos. Details are here.

The Super Blood Wolf Moon (Total Lunar Eclipse)

Last week, I wrote about tonight’s (Sunday) total lunar eclipse and posted it with diagrams here. Read on for an update on that information.

You’ve probably seen references to Sunday’s lunar eclipse as a Super Blood Wolf Moon, or a permutation of those words. These dramatic terms might elicit chuckles and/or eye rolls from astronomers, but they serve a purpose – to capture the imagination of the public and get them to head outside and look up! There are valid reasons for using each part of that label. Let’s break that down.

Blood Moon - The Earth is a solid sphere. The sunlight shining on Earth casts a circular shadow into space opposite from the sun. When an object, such as the International Space Station or the moon, passes through that shadow, no direct sunlight can reach it, so the object darkens. Some of the sunlight streaming closely past Earth passes through our atmosphere. The air refracts (or bends) the rays of sunlight because it slows the light down a little, and that refraction allows a small percentage of the sunlight, bent around the Earth’s perimeter, to reach the moon and slightly illuminate it. If Earth had no atmosphere, the moon would turn completely dark during a lunar eclipse!

During totality, only red light reaches the moon because our atmosphere scatters some wavelengths of light more than others. White sunlight is composed of a rainbow of component colours. The sky is blue in daytime because the molecules in the air scatter shorter wavelength blue light and lets longer wavelength red light pass straight through. Try this experiment. Shine a flashlight through a glass of water placed near the wall in a darkened room. You’ll see a distorted beam of white light on the wall. Now put a few drops of milk in the glass and the entire liquid will glow with a bluish light! If you didn’t add too much milk, you might also see that light on the wall is a now a warmer colour because the cool, blue wavelengths have been scattered throughout the liquid rather than passing through. The same effect causes sunsets to turn red, and only that reddened light can reach the moon during totality – colouring the moon a rusty red, or blood, colour.

Wolf Moon – The moon has always shone down upon humans on Earth. Eventually, people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and to celebrate life events. The twelve (sometimes thirteen) full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. Full moonlight allowed people to be out at night; hunting, or working the fields for extra hours to get the harvest in.

Each society around the world has its own set of stories for the moon and every month’s full moon has one or more nick-names. The Wolf Moon term is likely derived from North American First Nations traditions, although some think it has an Anglo-Saxon origin. In either case, it’s likely that hungry wolves were calling to one another in the dead of winter, and left an impression on people before our modern era. The January full moon, eclipsed or not, is known as the Wolf Moon, Old Moon, or Moon after Yule. It always shines in or near the stars of Gemini (the Twins) or Cancer (the Crab).

Super Moon – The moon orbits Earth every 27.3 days. The shape of the orbit is an ellipse that brings the moon alternatively closer and farther from the Earth. The difference in distance between perigee, the point in the moon’s orbit when it is closest to Earth, and apogee, when the moon is farthest away, is about 50,000 km. That causes a perigee moon to appear about 14% larger than an apogee moon – about the difference between a Canadian $1 and $2 coin when held at arm’s length. It’s not that much – visually. The closer moon will also be slightly brighter.

The term supermoon was coined to describe a full moon that happens while the moon is at or near perigee. January’s eclipsed full moon will occur fifteen hours before perigee, making it appear about 7% larger than average and generating high tides globally.

The supermoon aspect of this eclipse actually works against us. When the moon is near perigee, it is moving faster in its orbit, so it will cross the Earth’s shadow in a shorter time. The closer moon is also larger, so it remains fully eclipsed for a shorter time.

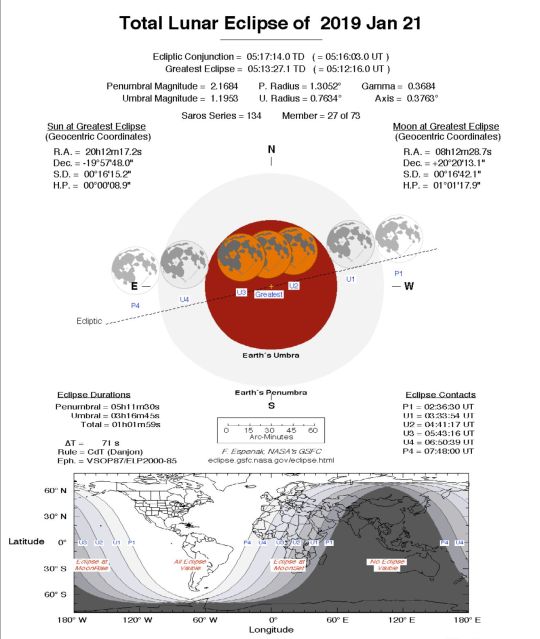

(Above: NASA’s Lunar Eclipse Page lists past and future eclipses. Each event has a web page with diagrams showing the path of the moon through the Earth’s shadow, where on Earth the eclipse will be visible (white areas), and the times for each stage of the eclipse in UT (equivalent to GMT). The partial eclipse stage will begin when the moon reaches position U1, and the moon will be fully eclipsed from U2 to U3 (about one hour). The second partial eclipse stage will end when the moon reaches U4 - 3 hours and 16 minutes after it began.)

Total Lunar Eclipse Visibility and Timings - This lunar eclipse will be visible start to finish in North and South America, the eastern Pacific Ocean, and westernmost Europe. Much of the eclipse will be seen in central and eastern Europe, but observers there will miss the later stages of the eclipse because they occur after moonset. For the western Pacific region, the moon will rise after the eclipse begins.

The partial phase, when the edge of the moon begins to darken, will begin when the moon contacts the Earth’s umbra at 10:34 pm EST on Sunday evening in North America (or 7:34 pm Pacific time and 03:34 UT). Starting at that time, look for the darkness to creep over the moon, growing from along its lower left edge.

At 11:41 pm Eastern time (8:41 pm PST), the last strip of brightly lit moon will vanish as the moon finally entirely enters the Earth’s umbra. The darkened and a coppery red appearance won’t be obvious visually or in photos until the moon is well into the shadow. The moon will stay fully within the shadow (referred to as totality) for 62 minutes. It will pass deeply through the shadow, and the moon’s southern half will appear darker than its northern half.

Greatest, deepest eclipse will occur at 12:13 am EST. After this, most people will head to bed because the second half of the eclipse mirrors the first half. The total eclipse phase will end when the moon begins to leave the umbra at 12:43 am Eastern Time on Sunday. At that time, look for a growing strip of illuminated moon to appear along the moon’s lower left edge. The partial phase of the eclipse will end at 1:51 am Eastern Time.

Now you know what to look for, and when to look. If you have a telescope, of any size, hold your phone’s camera over the eyepiece and take some photographs, or prop up your tablet or phone somewhere and take a time lapse movie of the eclipse. Hopefully the skies will be clear wherever you are! Don’t let cold weather keep you indoors for this one. The next total lunar eclipse won’t occur for the GTA until May, 2022.

The Moon and Planets

After Sunday night’s total lunar eclipse, the moon will spend the week waning and rising later. On Tuesday night, the moon will pass only two finger widths to the left of the bright, white star Regulus in Leo (the Lion). After mid-week, you can look for the moon in the western morning sky on your way to school or work.

Next Sunday afternoon, the moon will reach its Last Quarter phase, when it will rise at midnight and appear half-illuminated – on its western side. (Directions on the moon are opposite to sky directions.)

This week, Mars will shine as a medium-bright, reddish pinpoint of light in the southwestern sky. It will set at about 11:30 pm local time. Mars is slowly shrinking in size and brightness as we increase our distance from it.

(Above: Mars is the only bright planet in the evening sky nowadays, sitting above Neptune and below Uranus, as shown here at 8 pm local time.)

Blue-green Uranus is about 1.5 finger widths above, and slightly to the left of the modestly bright star Torcular (or Omega Piscium). This week, Uranus will be at its highest point, over the southern horizon, at about 6:30 pm local time – the best position for seeing it clearly. Dim, blue Neptune will set shortly after 9 pm local time, so look at it before 8 pm, while it’s higher. Neptune is sitting about two finger widths to the upper left of the modestly bright star Hydor (Lambda Aquarii). Hydor, and a pair of stars to its east (upper left), form a sideways narrow triangle with Neptune inside of it.

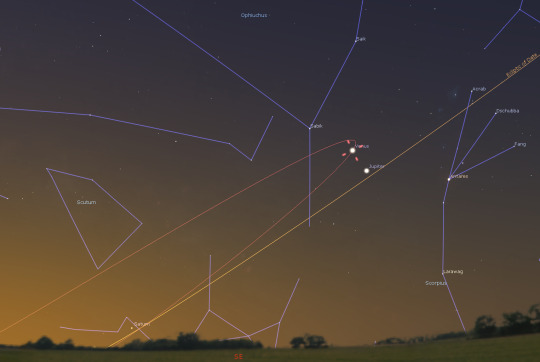

(Above: On Tuesday morning, descending Venus will pass very close to Jupiter in the southeastern pre-dawn sky, as shown here at 7 am local time. Saturn will be climbing higher every morning.)

Both Saturn and Mercury are too close to the sun to be seen this week, but next week Saturn will join the other two bright morning planets, Jupiter and Venus. Spectacularly bright Venus is now swinging back towards the sun, while not-as-bright Jupiter is being carried the other direction – west and higher. The two planets “kiss” this week. On Tuesday morning, Jupiter will be positioned only 2.5 finger widths south (to the lower right) of Venus. They will both fit within the field of view of binoculars. Look for the bright, reddish star Antares, the “rival of Mars” sitting a palm’s width to the right of Jupiter.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests - so, send me some!

1 note

·

View note