#vestibule

Text

View of a Gothic vestibule, in the foreground a nobleman with his dog

by Eduard Gerhardt

#eduard gerhardt#art#gothic#vestibule#entrance#architecture#medieval#europe#european#middle ages#nobleman#noble#dog#building#sculptures#history

610 notes

·

View notes

Photo

These Renovators Use This Wood Stripping Technique on Nearly Every Project

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The vestibule in Syon House, London, United Kingdom,

designed by Robert Adam.

Photo: DeAgostini / Getty Images

#art#design#interiors#interiordesign#vestibule#syon house#london#united kingdom#luxuryhouses#luxuryhomes#luxurylifestyle#robert adam#DeAgostini#style#history

671 notes

·

View notes

Text

yucatán, mexico

#patio ideas#patio furniture#vestibule#indoor fountain#water fixture#seating ideas#raw wood#concrete wall#concrete patio#mexican interiors#mexican design#interior design#interior decor

169 notes

·

View notes

Photo

背中で語る要求 A demand that speaks from the back #猫 #ネコ #ねこ #neko #cat #玄関 #vestibule #door #ドア #nikon #coolpix #S10 (Tokyo Japan) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cnyg1VGJeiA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

'The world inside', Mar. ’16, ph Erik Gigengack

Prints available at Catawiki, see page here.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

My boss pronounces "vestibule" like it's spelled "vestible" and it has completely ruined the word for me, now I call entryways "vegetables"

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nadine and the Housebroken Spider

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

IG simplysmashingdesign

#entry hall#vestibule#staircase#interior design#architecture#transome windows#leaded glass#vintage#black & white

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dante’s Hell: The best... well “least worst” part of Hell

In this series of posts I will focus exclusively on Hell itself, as described and depicted by Dante in his poem. There is a story beyond just having a guided tour of Hell, and the story begins before the protagonists even enter Hell – but for the sake of simplicity I’ll just focus on Hell. The only thing you need to know is that Dante was chosen to have a private, guided tour of Hell to see and learn everything about it, and report it all to the living world (or rather a fictional, unnamed version of Dante) – and his guide to Hell is the famous poet Virgil, one of the greatest poets of Ancient Rome, resurrected as a “shade”. That’s the basic.

I) The Gate of Hell

Let’s begin with the beginning… The Gate of Hell. Located somewhere at the end of a “deep and rugged road” in a “dark forest” that might be entirely metaphorical to begin with. The door to Hell isn’t described itself, but Dante reveals to us that an entire poem is written in dark letters right above it, a warning to all about to cross the gates. One line of this poem became particularly famous and stuck in popular culture, the famous: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here”. However it is but one fragment of the full poem:

“Through me you pass into the city of woe, through me you pass into eternal pain, through me among the people lost for aye.

Justice the founder of my fabric moved ; to rear me was the task of Power Divine, Supremest Wisdom, and primeval Love.

Before me things create were none, save things eternal, and eternal I endure. All hope abandon, ye who enter here.”

[Note: this isn’t the most recent, translation, as you can note it is quite old in orthograph, and not everybody agrees with this translation, but it is the most widespread one on the Internet, so that’s the one I’ll use. My books have other translations, but I’m not going to make a full comparison here.]

So, what does this poem tells us? Very important things. The first part of the poem is a warning people about where the door leads: Hell, realm of eternal pain and woe, where all the souls are “lost”, aka damned. The second part of the poem however clearly points out that the Gate of Hell was created by God himself, out of an action of supreme “wisdom and love”. The poem goes on to say the Gate of Hell was created before any living being ever existed, and that it is eternal (and by extension Hell too). Finally, the last lines point out that entering Hell means losing all hope – because when you are sent to Hell, there is no hope. You have no way to get out of there. You’re stuck forever. In Dante’s world, there is hope if you go to Purgatory, which is a “temporary Hell” from where you’ll reach Heaven. But here? Hell is for those beyond salvation. For eternal damnation, without any possibility of being saved.

Which is a very interesting concept, because here you already have a hot Christian topic brought up… I will digress a bit here, but you know how all those “fire and brimstone” preachers and fanatic Christians like to shout about “eternal damnation” and “endless torments”? Well… they’re not exactly right. It is true that Christianity did create an “eternal punishment” in the form of Hell to scare people out of sin – but Christian authorities also very clearly understood the big problem of imposing endless torments, in a religion where the god is all-loving and all-forgiving and only wishing the best for everyone. So, what Christianity did was reconcile the two concepts by saying “Well… Hell is eternal for a time”. You know about the whole “Judgement Day” thing? If you are American, it probably means “apocalyptic end of times” and “the Rapture where all the good living people go to Heaven” or something like that. That’s some weird American beliefs I got a hard time understanding when I first discovered them, because I was raised on the “good ol’ Catholic faith”, and so I was with the “original” sense of the Judgement Day. Judgement Day is also called the “great resurrection”, because it is said that on this Judgement Day, last day of the world as we know it, all the dead will return to the world of the living, gain back a new body, and be judged again in front of God. Originally this “final judgement” was used in early Christianity because there was not any clear concept of Hell yet – Christians believed people would just wait in some sort of eternal darkness after their death, and then be judged for their good or bad behavior at the end of the world. The addition of Hell and Heaven as places of “immediate” judgement seems to be quite redundant with this “big final trial”… BUT Christianity reused the Judgement Day belief to get out of the whole “hell dilemma”, by claiming that Hell is “eternal”, because Hell will only end with the world and time itself. So… it is eternal, because it will last to the end of time. But at the same time, God is kind and merciful enough to not let the damned souls in Hell forever, and so at the end of all things, all the damned souls we get a new judgement and get access to the great big, new paradise-world prepared for them, with all evil wiped out of creation and Hell not existing anymore.

That’s a lot of theological mumbo jumbo, but this is the kind of shit you need to get used to when entering the actually very complicated beliefs of Christianity (especially Catholic Christianity). Anyway, if I recall well Dante himself will actually ask Virgil somewhere during the poem about Judgement Day, and Virgil will deliver Dante’s (the author, not the character) own take on this concept.

II) The Vestibule of Hell

It might surprise you to learn that the Gate of Hell… doesn’t actually lead to Hell directly. No, it rather leads to a place commonly referred to as the “Vestibule of Hell”, or “Ante-Hell”. What immediately strikes Dante upon entering this place is the noise. LOT of noises: sihs and cries and shrieks and lamentations and shrill outcries, and cadences of anger, and raucous groans, all forming a sonic “whirling storm” throughout the “starless air of Hell”. This comes back several times throughout the poem – Hell is actually a very noisy place (at least in the upper levels).

Virgil presents to Dante the souls trapped in the Vestibule of Hell, who are actually the “sad souls who lived a life, but lived it with no blame and no praise”. Basically they are the neutral souls, all those people that lived without doing anything bad, but without doing anything good either, out of cowardice, or laziness, or opportunism, or whatever. Due to their absolute neutrality, Heaven cannot accept them in their ranks, so they send them to Hell, but since they are not sinners per se, Hell relegates them to its very doorstep, outside of its actual circles for “real” sinners. Here, the souls, nameless and shapeless, constantly follow a banner that keep whirling and moving in the wind without any clear direction or goal – it just wanders aimlessly, and the souls have to follow it forever, the same way they “went with the tide” or “went with the flow” in their life. And, since these people made themselves “hateful” as much to God as to His enemies (Satan and his demons), they also get punished – here by hornets and wasps constantly attacking and stinging them as they run behind the banner (we even have a lovely description of their blood, tears and pus flowing onto the ground, where maggots feed of it).

[A quick note here about the “body” of those damned souls – the “shades” of the sinner. Here, Dante uses a logic used by most Christian artists. When it comes to traditional depictions of Hell, you see the sinners with bodies, right? But the thing is that Christian recognized that after death, you just became spirits and souls, since there is nothing material beyond our world – and this is the whole point of the “resurrection at the end of times”, when the bodies of the dead will be given back to them. It is also why Christians refused incineration for a very long time, believing the body needed to be buried to be able to be “recreated” at the end of days. Well what Dante used – which is an explanation similar to the one used by Christians – is the “pagan” logic of the “shades”. In Hell and Purgatory, the souls are given back a humanoid-shaped body, but a “shadow” of a body, that looks human, can perform basic human tasks, and can act and react like a human body – it can bleed, be cut, etc etc… And yet is not made of flesh, bones or organs, but rather of some sort of air, aether, shadow or whatever material spirits and souls are made of. A sort of mock-body only designed to receive punishments but unable to maintain actual life in a physical or material world.]

What is even more interesting here is that there isn’t only human souls in the Vestibule of Hell… But also angels. More specifically this group of angels that, during Lucifer’s rebellion against God, stayed neutral. They did not help Lucifer and his armies and did not turn into demons, but they also did not protect or defend God and thus were cast away with the other rebellious angels. These fallen spirits were the first residents of the Vestibule of Hell, punished for standing out for themselves instead of staying “faithful or unfaithful to their God”, and now mingling with the nameless, faceless masses of the neutral humans.

This is a bit of lore that is NOT part of Christian canon, even though it is present in many folktales and folkbeliefs, and Dante’s choice of this legend is tied to the whole context of the “Divine Comedy”. I said it before, Dante likes to put his enemies in Hell – he uses his “Inferno” poem as a way to criticize everything wrong with the Italy of his time, and as a way to publicly denounce or insult famous people of the time or people he had a more personal quarrel with. And one of Dante’s BIG topic in Inferno is a big civil war that happened in Florence and in which he was involved – a civil war that led him to lose a lot of things and left him with a lot of grudges. It was the conflict of the Guelphs and Ghibellines – and due to living through this conflict, Dante has a big, BIG obsession with punishing in Hell those that cause strife, divide communities and cause civil wars. On the flipside, this also shows why he hates neutral people so much he basically throws them in a cheap, knock-off version of Hell – having been himself a partisan in this long political conflict, Dante view very badly those that tried to stay neutral in the conflict as the rivalries, oppositions and persecutions basically tore his home-city (Florence) apart.

III) Acheron

Beyond the souls of the neutral, Dante spots a crowd of souls by the shores of a wide river, “waiting eagerly in a dim light”: it is the souls of all the recently arrived damned of Hell, waiting on the “sorrowful shore” of this “livid” marsh of dark waters called Acheron. They wait for a boat, driven by an ancient, white-haired old man, a demon with eyes like burning fire or glowing ambers – Charon. Yep, we are here talking about the river Acheron and the ferryman Charon from Greek mythology! The first of many Greco-Roman elements Dante uses in his Hell.

Upon arriving, Charon promptly tells the “perverted souls” that they better forget all hopes of seeing Heaven, because he is here to lead them into “eternal darkness, ice and fire” – and upon hearing this, suddenly all the souls start shivering with fear, and cursing everything in their life, and they weep. Some even try to not enter Charon’s boat – at which points he has to beat them in with his paddle. Virgil explains to Dante this strange behavior by a specific phenomenon – if all the souls amassed eagerly on the shores before, it was because of the “Divine Justice”, whose immense power turned the souls’ fear of Hell into a “desire” and attracted them like magnets to the river… only for Charon’s arrival to break the spell and make them realize exactly where they are, and where they are going.

And Acheron forms the real true “barrier” that separates the “fake” Hell that is the Vestibule, from the “real” Hell awaiting further…

Oh yes, and all the souls of Hell are naked. It is confirmed at this point of the poem.

IV) First Circle: Limbo

Now, a brief theological explanation for what “Limbo” is. Because Limbo isn’t Dante’s invention: at one point in the Christian history, people started to wonder “Hey… You only can get into Heaven if you are Christian right? But… there were plenty of good people before Christ was born. Heck, half of our Bible is about good servants of God that existed before Christ was here! So what happened to them? Are they sent to Hell just for being born in the wrong century? That’s unfair!”. To resolve this problem, Christianity completely invented a new afterlife: the Limbo of the Patriachs. A place that is not Hell, but not Heaven, and where all the good and decent people that had no way to become Christian would go (because again, in a Christian logic only a Christian can possibly reach the true, Christian Heaven). The Limbo of the Patriarchs basically hosted all the good people who lived and died before Christ, and all of the good people that lived in countries where Christianity never arrived – people who didn’t deserve Hell, but could not live according to Christian teachings and so are not considered “true good” people either. There was another Limbo, the Limbo of Infants, with a similar purpose but a very different “clientele” – it was the Limbo hosting the souls of children, infants and babies that died before they could have a chance to be baptized (Christians had an obsession with baptizing their children as soon as they were born, because due to high infant mortality, there was strong chances the child would die before he could become a good Christian). This concept of Limbo stuck for a while during the Middle-Ages and then was quietly… gotten rid of, as times passed and the Church realized how problematic this all was. Nowadays the Church has more of a silent position on this subject – they don’t teach the existence of Limbo anymore or approve of this belief, and claim all infants who died before baptized go to Heaven, but they also do not strictly say “Limbo doesn’t exist and we were wrong for centuries”. It is quite of a “We don’t talk about it and do as if no one knew about it”.

Anyway – all of this being sorted out, Dante does use the concept of “Limbo” but he makes it, interestingly, a part of Hell rather than a separate realm. Mind you, it is quite a pleasant part of Hell – as I said in my intro, the “higher” the circle of Hell, the closer it is to the living world and the further it is from the devil, and the lesser the sin and punishment is. In fact, Dante is quite struck by the fact that all the screams, wailings and screeching of the Vestibule are now gone, with the First Circle being merely filled with… sighs. Sad sighs everywhere, but no true sound of pain or torment. As Virgil explains, in this version of Hell, this Limbo takes in people that were not sinners, but simply were never baptized and never knew the “true religion” of Christianity, which does ban them from Heaven. Virgil himself was actually a denizen of the First Circle being before “hired” to guide Dante throughout Hell – in his own word, these are not damned souls of sinners, but souls lost “by default” and that feel no guilt (unlike the other residents of Hell). And the only “punishment” these souls have is to know that they are “alone”, cut off from the hope of ever reaching Heaven, denied the “true God” and its love/wisdom/truth. So the souls of these men, women and children just… wait around. Dante even calls them a “forest” at some point, because they are numerous (Limbo is the biggest of all circles) and the souls are “as thick as trees”.

In Limbo, there is a special place different from the darkness of sighs forming the rest of the circle: a great and beautiful castle of light. The souls in it have a different fate from the others – they get to live in this beautiful palace of shining light, surrounded by seven walls and doors, and with inside a fresh meadow full of calm and quietness. As Virgil reveals, these souls actually gained the favors of Heaven and thus have a much more pleasant stay in Limbo than the others. And how did they gain these favors of Heaven? By becoming famous in a good way, by shaping the history and culture of the world (in a good way), and by leaving behind good and helpful heritages that made them worth of a little piece of fake-Heaven in Hell. Dante first, of course, as the poet he is, places the famous pagan poets: Homer, Horace, Ovid, Lucan… He then goes on by citing famous pagan rulers, warriors and heroes, some historical some mythology (Electra, Hector, Aeneas, Caesar, Penthesilea, Lavinia, Orpheus…), followed by the great philosophers (Socrates, Plato, Diogenes, Empedocles…) and various great and famous scientists (Euclid, Ptolemy, Hippocrates…). As you can see there is a HUGE focus on Roman history (again, the whole Divine Comedy is Italian-centric), and a big focus on Greco-Roman Antiquity (we are here in the beginning of the Renaissance, an era which idolized the Greco-Roman Antiquity as the “golden age” of humanity). But Dante still includes other “noble and virtuous pagans” among the residents of the shining castle – for example Saladin. [Fun fact: the fact that the castle has seven walls and seven doors has been interpreted in various ways by people, from them representing the seven arts, to them being the seven virtues].

Dante also has a brief theological talk with Virgil about another specific topic of the Christian religion: the Harrowing of Hell. You see, in Christian doctrine and belief, when Jesus Christ died at the Crucifixion, he went into Hell and stayed there for three days. Then, he resurrected by getting out of Hell – and in the process, he got back all the souls from there, cleaning them of their sins and evil, and getting them into Heaven. Basically this belief and legend claims that the Christ completely reformed the Heaven/Hell system, and said “Okay, now Hell’s criteria are obsolete because I redeemed the sins of humanity and opened a new way to Heaven. So I’ll take all the souls you had until now, bring them with me up there, and you start all over again, okay?”. Dante, upon seeing so many souls in Limbo, is a bit confused and asks Virgil if the Harrowing of Hell truly happened as the Church teaches it – and Virgil confirms that it did happen, oh yes, the Christ did save the people of Hell… or to be precise he took with them only a part of the residents of Limbo – and those were all Biblical characters who treated with the Hebrew God/proto-Christian God. Noah, Abraham, Moses, Abel, David, Israel, Rachel – those are the ones he took with him, leaving the others in Limbo. Remember the story of the Harrowing of Hell, it will become important latter.

V) Minos

Now, Dante and Virgil leave the First Circle and start their descent into the Second one… But oh wait! There is something blocking the way at the edge of the Second Circle. Or rather… someone.

King Minos. In Greek mythology, Minos was one of the three “Judges of the Hades”, human kings renowned for their wisdom and justice who were hired by the gods to become the judges of the dead in the afterlife. But here, Dante reinvents the figure of Minos. He is still a judge of the dead, but a “grotesque and snarling” figure, with a long snake-like tail. All the damned souls, after crossing the Acheron and the First Circle, must go in front of Minos and there they are compelled to confess all of their sins. Minos listen and judges them, by deciding on which of the Nine (well, rather Eight) Circles of Hell they will go. He renders his judgement by having his tail wrapping around his body – the number of coils he forms indicates the Circle the damned will have to be “hurled into”. Because one of the things that are recurring in this poem is that Dante can never see the next Circle – or barely see it. Whenever he looks above the edge of each Circle, all he sees is a deep, dark, bottomless abyss of shadows and cries, so each new level is a true surprise.

Minos briefly tries to distract and frighten Dante (previously Charon tried to refuse Dante access to his boat on account of him being alive, and tried to tell him to take “other boats at other ports”, only to get shushed by Virgil – something very similar happens here) – Minos explains to Dante that he should not trust or be fooled by those he will find in Hell, and warns him that excited Hell will be much harder than getting out… But Virgil tells him to basically shut up, and not block their “fated journey” ordered by the higher powers themselves. So Minos lets them pass… into the Second Circle.

#dante#inferno#hell#limbo#circles of hell#first circle#vestibule#acheron#charon#dante alighieri#the divine comedy#minos#gate of hell

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

These four Louis XVI style rooms were removed from the Hôtel de Breteuil before it was demolished in 1923 and were reassembled at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. The mansion was built in the late 18th century by a master carpenter named Jacques Millet. It later became the home of Viscount Claude-Stanislas Le Tonnelier de Breteuil who gave it his name. The furniture displayed in the rooms is from the same period.

Photos by Charles Reeza

#French decorative arts#domestic architecture#antique furniture#woodwork#molding#cornice#harp#clock#chess table#budoir#salon#vestibule

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vestibule - Mudroom

Mid-sized transitional entryway design with a purple front door and walls and a beige floor as an example.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of Union’s best bits has largely been hidden from public view for a generation. It is again part of the station itself with the reopening of the eastern wing off of the Great Hall. Just use the easternmost doors on Front St W. and enjoy! • • • #igerstoronto #toronto #ontario #canada #torontophotography #urban_toronto #unionstation #metrolinx #ttc #gotransit #viarail #upexpress #vestibule (at Union Station) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ch3A-uFpxKt/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#igerstoronto#toronto#ontario#canada#torontophotography#urban_toronto#unionstation#metrolinx#ttc#gotransit#viarail#upexpress#vestibule

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

奥にもいるよ There's another cat in the back #猫 #ねこ #ネコ #cat #neko #玄関 #vestibule #庇 #eaves #黒白猫 #black_and_white_cat #キジ白猫 #yellow_tabby_cat #panasonic #DMC-LZ2 https://www.instagram.com/p/Cn57ratBlOJ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

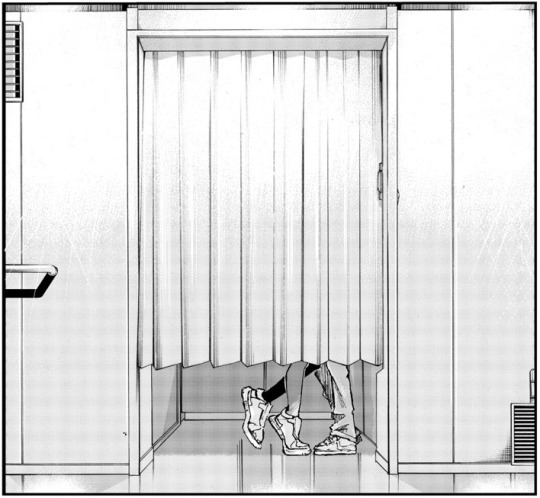

Vestibule by Suzanne Moxhay.

This is a very disorganized blog, lol.

4 notes

·

View notes