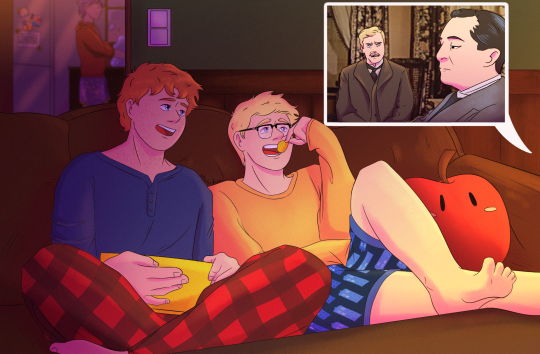

#we stan harvey in this household

Text

Having a good ol' Granda Holmes marathon in the enby household

Quill, in the background (@jellyaris )

Reed, left side of the couch (@shoddy0-0 )

Jay, right side of the couch (me)

#my art#stardew valley#farmer oc#farmer jay#farmer quill#farmer reed#enby household#what is gender#fuck the binary#we stan harvey in this household#granda holmes#i love reed and quill so much you don't understand#aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaqaaaaaa

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isn't it Obvious [Jay/Harvey]

Greetings. I wrote a gift fic for my friend @doctoraceus (hi friend)

Never written for anyone's farmer's other than mine so this was a really fun challenge. (Comic and Lore by @doctoraceus as well)

Summary: based on a comic from This Post

Warnings: None (lmk)

Word Count: 1.2k

--------------------------------------------------

It was a late summer night, many years ago, when everything changed for Harvey Sheffield. He and his best friend Jay were watching their favorite show like they always did on Saturday nights. Jay had a habit of reciting the actors' lines out loud, extremely exaggerated, with silly voices and over the top hand gestures. It never failed to make them both crack up laughing, but something about that night felt different.

It was at the age of 15 that Harvey knew he was in love with Jay Basham. Perhaps it had been even longer than that. Whenever he thought back to that night, he wondered if he had simply been too blind to realize it sooner.

Ever since Jay took down a bully for Harvey on the schoolyard when they were 10, they had been inseparable. Jay became his protector, no one dared to mess with him ever again. Nothing could keep the dynamic duo apart, not even when Jay got adopted and moved all the way out to Pelican Town to live on Sour Cherry Farm. It was clear that no amount of distance could keep them apart. Even when Harvey got accepted into medical school and followed his dream of becoming a doctor, they always kept in touch.

...

Dating was never something that ever worked out for Harvey. He tried it in university and medical school, but he just couldn't seem to find that connection that he was looking for. Perhaps, somewhere at the back of his mind, he secretly hoped that things would eventually work out with Jay in the end. He loved their late-night video chats and hour-long phone calls while he studied for his exams, but it was a poor substitute to having them by his side. He knew he would see them again someday, that was always the plan. So, when he found out that the local doctor was retiring in a little place called Pelican Town, he jumped at the chance and applied for the job.

...

On the day that Harvey moved into the small apartment above the clinic and finally got the chance to reunite with Jay, he was crushed to find that they were already in a relationship with Shane, the local ranch-hand. Harvey tried his best to convince himself that he was happy for them, but it was no use. When Jay seemed perfectly happy to pick up right where they left off, it only confirmed Harvey's suspicions. Jay only saw him as a friend, nothing more.

Despite his feelings, he was happy to have his best friend back after all those years apart. As busy as both their schedules were, Jay working on the farm full time and Harvey running the clinic with only one other employee, Jay still managed to stop by at least twice a week to chat over coffee or have lunch together at the saloon. Everything was back to normal.

...

Harvey never figured out why Jay's relationship with Shane ended. He tried to get them to talk about it, to offer comfort and support, but they refused to tell him what happened. All he knew was that it was Shane who ended things, and Jay did not want to talk about the reason why.

As the days went by and the seasons changed, Harvey and Jay grew even closer than they were before. Unfortunately for Harvey, it only made him fall deeper in love with them. With Harvey's somewhat limited experience with romantic relationships, he wasn't exactly sure what the etiquette was for something like this. What exactly is the appropriate amount of time that should pass before confessing your love for your childhood best friend who just got out of a long-term relationship? He thought it would be best to be subtle in his approach, as not to seem too eager. Showing up at the farm unannounced, under the guise that he was 'concerned they were overworking themselves'. It was true, he was concerned. Jay spent a lot of time tending the fields, going on fishing trips, and even fighting monsters down in the Pelican Town mines. But Harvey also wanted an excuse to see them more often. Instead of having coffee down in the clinic, Harvey often invited Jay up to his apartment so they could spend some more time together, but Jay always took it as more of a friendly gesture as opposed to an opportunity to get closer.

After all of his... well, ‘advances’ was probably the wrong word, nothing seemed to be getting through to Jay. Harvey knew he wasn't the best at flirting, but he was never one for bold gestures. Jay was always better at that. They were always the one to speak their mind whenever they got the chance. Harvey wished he could be that brave.

…

One sunny morning, Harvey was preparing his usual cup of coffee before getting ready to head to the library, when he noticed something strange about one of the mugs in his kitchen cupboard. It had a piece of paper taped to the side of it with what looked like a phone number on it. He immediately recognized the mug as one of the ones Jay brought over to have coffee with him. Harvey felt his heart rate speed up a little as the realization hit him.

Returning the mug was a perfect reason to show up at the farm for no reason. Maybe on the way there he could talk himself into finally confessing his feelings for Jay.

During the trip down the long dirt road to Sour Cherry Farm, he spotted a flash of orange down the path. They had blue denim overalls, short light blonde hair, and a pickaxe slung over their shoulder as they strutted along the path toward him.

"Jay!" He waved. "There you are, I was just on my way to see you."

"Hi Harvey!" Jay waved back, jogging toward him. The bright smile on their face nearly made him blush.

"Where are you off to this morning?" He asked.

"I was just about to go out to the mines." Jay replied, shifting the pickaxe to keep it from falling off their shoulder. "What can I do for you?"

"The mines? Oh. Well, please be careful. I wouldn't want to see you end up in the clinic. N-not that I don't want to see you, it's just- I mean of course I want to see you, but not in the clinic. I mean, um. Please take care of yourself." He managed to spit out.

Lately, Harvey often found himself getting nervous around Jay. He always felt safe around them, but hiding his feelings for so long made him a bit awkward whenever he tried to talk to them.

"I just wanted to return this." He added. "You forgot one of your coffee mugs at the clinic." Harvey suddenly remembered the note and quickly reached into his pocket. "Oh, and also apparently your phone number."

As he tried to hand both the mug and the slip of paper back to Jay, their cheeks turned an adorable shade of pink.

Harvey stared at the phone number in his hand and felt his own face beginning to heat up as it suddenly clicked.

“Oh-”

Yet again, he had been too blind to realize what was right in front of him the whole time.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. Flood Strategy Shifts to ‘Unavoidable’ Relocation of Entire Neighborhoods

Policymakers have long stuck to the belief that relocating entire communities away from vulnerable areas was simply too extreme to consider — an attack on Americans’ love of home and private property as well as a costly use of taxpayer dollars. Now, however, that is rapidly changing amid acceptance that rebuilding over and over after successive floods makes little sense. Should U.S. tax dollars be used to move whole communities out of flood zones: (1) Yes, (2) No? Why? What are the ethics underlying your decision?

This week’s one-two punch of Hurricane Laura and Tropical Storm Marco may be extraordinary, but the storms are just two of nine to strike Texas and Louisiana since 2017 alone, helping to drive a major federal change in how the nation handles floods.

For years, even as seas rose and flooding worsened nationwide, policymakers stuck to the belief that relocating entire communities away from vulnerable areas was simply too extreme to consider — an attack on Americans’ love of home and private property as well as a costly use of taxpayer dollars. Now, however, that is rapidly changing amid acceptance that rebuilding over and over after successive floods makes little sense.

The shift threatens to uproot people not only on the coasts but in flood-prone areas nationwide, while making the consequences of climate change even more painful for cities and towns already squeezed financially.

This month, the Federal Emergency Management Agency detailed a new program, worth an initial $500 million, with billions more to come, designed to pay for large-scale relocation nationwide. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has started a similar $16 billion program. That followed a decision by the Army Corps of Engineers to start telling local officials that they must agree to force people out of their homes or forfeit federal money for flood-protection projects.

Individual states are acting, too. New Jersey has bought and torn down some 700 flood-prone homes around the state and made offers on hundreds more. On the other side of the country, California has told local governments to begin planning for relocation of homes away from the coast.

“Individuals are motivated. They’re sick of getting their homes flooded,” said Daniel Kaniewski, who until January was FEMA’s deputy administrator for resilience. “It’s not easy to walk away from your neighborhood. But it’s also not easy to face flooding on a regular basis.”

Laura, a Category 4 Hurricane with winds as strong as 140 miles per hour, is expected to make landfall near the Texas-Louisiana border overnight, causing what the National Hurricane Center called an “unsurvivable storm surge” of 15 to 20 feet along parts of the coast and reaching as much as 30 miles inland. City and county officials in Texas and Louisiana have issued evacuation orders affecting about 500,000 residents.

The federal government has long paid to buy and demolish individual flood-damaged homes. What’s different is the move toward buyouts on a much larger scale — relocating greater numbers of people, and even whole neighborhoods, and ideally doing it even before a storm or flood strikes.

Officials’ increasing acceptance of relocation, which is sometimes called managed retreat, represents a broad political and psychological shift for the United States.

Even the word “retreat,” with its connotations of defeat, sits uncomfortably with American ideals of self-reliance and expansion. “‘Managed retreat’ is giving up. That’s un-American,” said Karen O’Neill, an associate professor of sociology at Rutgers University, in explaining why the concept seemed unthinkable until recently.

But that view has been blunted by years of brutal hurricanes, floods and other disasters, as well as the scientific reality that rising waters ultimately will claim waterfront land. In the latest National Climate Assessment, issued in 2018, 13 federal science agencies called the need to retreat from parts of the coast “unavoidable” in “all but the very lowest sea level rise projections.”

All of that, coupled with the growing cost of recovery (federal spending on disaster recovery has totaled almost half a trillion dollars since 2005) has led to the realization that some places can’t be protected, according to government officials and scientists. The shift is all the more remarkable for occurring during the presidency of Donald Trump, who has called climate change a hoax and rolled back programs to fight global warming.

The Obama administration began experimenting with relocation after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, paying for programs in Staten Island and New Jersey designed to buy and demolish large numbers of flooded homes to create open space as a buffer during storms. In 2016, it gave Louisiana $48 million to relocate the residents of Isle de Jean Charles, a village that had lost most of its land to rising seas and erosion.

Yet the administration never managed to apply that approach nationally.

The March Toward ‘Managed Retreat’

In December 2016, just weeks before President Obama left office, the White House created without public notice a working group on managed retreat, made up of senior officials from 11 agencies, to figure out how to move communities threated by climate change. Once President Trump took office, that effort was abandoned.

But that was before Hurricane Harvey devastated Texas in 2017, the first in a series of disasters that much of the country is still trying to recover from. Since then, despite President Trump’s dismissiveness of climate change, the agencies under his control have accelerated their push toward relocation amid demand from households eager to leave vulnerable homes, as well as officials looking for alternatives to endlessly rebuilding in place.

Last summer, HUD detailed a disaster-mitigation program that offers $16 billion for “large-scale migration or relocation” and other steps. North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas have since said they want to use that money to fund buyouts, the purchasing and demolishing of homes exposed to storms, among other things.

For places that can’t affordably be protected, “we’ve got to look at how we prospectively relocate people,” said Stan Gimont, who helped create the program as deputy assistant secretary for grant programs until he left the department last summer.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which also funds buyouts, has begun pursuing them more aggressively. Those buyouts used to be voluntary: Residents who didn’t want to sell their houses could stay, even if the Corps’ analysis said moving made more sense.

But the Corps has recently changed its position, insisting that cities and counties agree, up front, to use eminent domain to force people from their homes to qualify for Corps-funded buyouts.

Joe Redican, deputy chief of the planning and policy division for the Corps, said his agency had found that, in some areas, keeping people safe over the long run was more affordable by purchasing homes than by building new infrastructure to protect them.

The latest evidence of the shift toward relocation came this month, when FEMA made public the details of its new grant program. As with the new HUD program, one way cities and states can use the money is for “larger-scale migration or relocation.” Rather than just buying and demolishing a handful of individual homes, the agency told state and local officials to consider how they would protect whole communities from future harm.

The program, which also pays for building codes, new infrastructure and other projects, “is a transformational opportunity to change the way the nation invests in resilience,” said David Maurstad, FEMA’s deputy associate administrator for insurance and mitigation. “FEMA can now support communities with investing in much larger-scale mitigation efforts.”

In Louisiana, officials describe a new willingness to plan for pulling back from the coast.

“That’s not a conversation that we were comfortable having, as a state or as a series of vulnerable communities, say, five years ago,” said Mathew Sanders, the resilience policy and program administrator at Louisiana’s Office of Community Development. “It’s now a conversation that we can have.”

The project to relocate people from Isle de Jean Charles, which his office manages, offers a blueprint for retreat. After years of sometimes contentious public consultations, construction started this May on what’s being called The New Isle, some 30 miles to the north. All but a handful of households have said they will leave Isle de Jean Charles.

Joann Bourg recently moved off the island into a temporary apartment nearby, paid for by the state, while she waits for The New Isle to be finished. She recalled always needing to keep a backpack ready, for whenever the next storm or flood forced her from her home. “I don’t have to do that no more,” Ms. Bourg said.

“That’s family land,” she said of the property she will be leaving behind. “But I don’t miss all the water. I don’t miss having to evacuate.”

Most residents of Isle de Jean Charles are American Indians. Chris Brunet, a member of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe who still lives on the island, said he initially worried that moving would mean surrendering that identity, which is tied to the land his ancestors lived on. “I wanted to make sure that I could bring that with me,” Mr. Brunet said.

He eventually decided he could maintain that identity in the new community — something he described as a long process of coming to terms with leaving.

On Sunday, Mr. Brunet left his home ahead of this week’s storms. He said most of the other remaining residents had evacuated the island as well.

Isle de Jean Charles is unlikely to be an isolated case. Last year, Louisiana issued a sweeping strategy for its most vulnerable coastal parishes, laying out in great detail which parts would likely be surrendered to the rising seas, and also how inland towns should start preparing for an influx of new residents.

“We don’t have ready-made solutions,” Mr. Sanders said. But talking openly about retreat, he added, can produce “better outcomes than if we do nothing.”

Christopher Flavelle focuses on how people, governments and industries try to cope with the effects of global warming. He received a 2018 National Press Foundation award for coverage of the federal government's struggles to deal with flooding. @cflav

A version of this article appears in print on Aug. 27, 2020, Section A, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Flood-Prone Communities Retreat to Drier Land.

0 notes