#whencyclopedia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

📌 WE'RE holding a historical fiction contest!

To enter, write a historical or mythological short story under 2,000 words. Submissions are open on 4 September. You have the chance to win some great prizes from World History Encyclopedia and Oxford University Press! Free to enter. See the prizes 👉🏽 https://fictionprize.worldhistory.org/

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

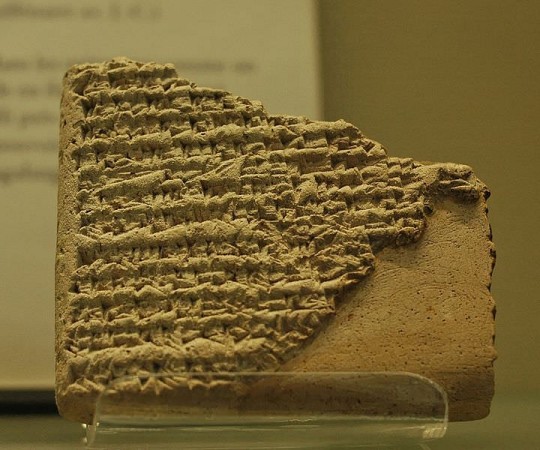

The Marduk Prophecy: A Historical Document of Mesopotamia

The Marduk Prophecy is an Assyrian document from between 713-612 BCE, found in the House of the Exorcist in Ashur. It narrates the travels of Marduk's statue from Babylon to lands like Hittite, Assyrian, and Elamite territories, prophesying its return by a strong Babylonian king. This prophecy was likely written during Nebuchadnezzar I's reign (1125-1104 BCE), celebrating his victory over the Elamites, who had captured the statue, and his subsequent return of it to Babylon.

Historical Context and Significance

Nebuchadnezzar I's Victory: The document was crafted to emphasize Nebuchadnezzar I's role in restoring Marduk to Babylon, highlighting the importance of a king's duty to his deity.

Political Themes: The prophecy leverages historical events to illustrate political themes, such as the alliance with Hatti and Assyria versus the rivalry with Elam.

Mesopotamian Naru Literature: It follows a common narrative technique where historical events are retold with poetic license to make a political or religious point.

Marduk in Mesopotamian Mythology

Marduk, son of Enki, became the king of the gods after leading them to victory over the forces of chaos, led by Tiamat. He established order and created humans as co-workers with the gods. Marduk was extremely important to Babylon, especially during the reign of Hammurabi and up until the Persian rule.

The Statue's Travels

The statue's journey included being taken by the Hittites, Assyrians, and Elamites at different times. It was returned to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar I and later by Esarhaddon. The statue remained a central figure in Babylonian festivals until its destruction by Xerxes I in 485 BCE.

The Significance of Marduk to Babylon

Marduk was not a distant deity; his presence was deeply felt in Babylon, and his statue was a symbol of his residence among the people. The absence of the statue during times of conquest led to significant cultural and religious disruption.

The Final Fate of the Statue

The final destruction of the statue is attributed to Xerxes I during his conquest of Babylon, a claim supported by Greek writers like Herodotus, despite their accounts being criticized for inaccuracies. The lack of further mention of the statue in historical records supports this narrative.

Learn More

The above summary was generated by AI using Perplexity Sonar. To read the orginial human-authored article, please visit The Marduk Prophecy.

220 notes

·

View notes

Photo

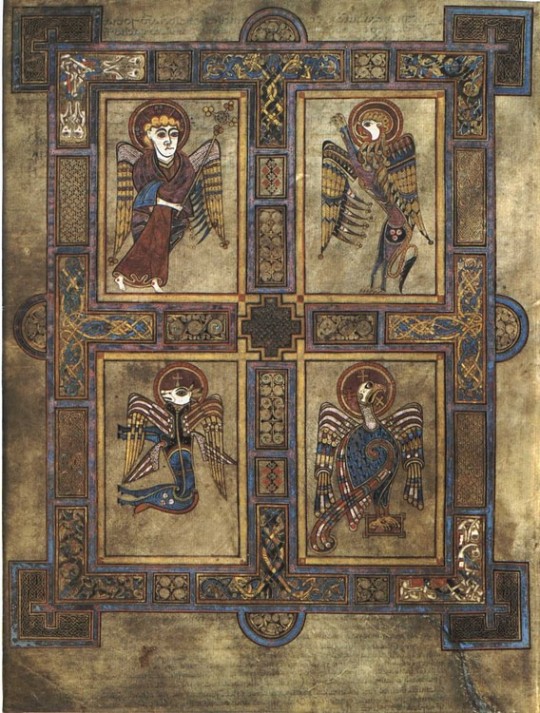

Book of Kells

The Book of Kells (c. 800) is an illuminated manuscript of the four gospels of the Christian New Testament, currently housed at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. The work is the most famous of the medieval illuminated manuscripts for the intricacy, detail, and majesty of the illustrations. It is thought the book was created as a showpiece for the altar, not for daily use, because more attention was obviously given to the artwork than the text.

The beauty of the lettering, portraits of the evangelists, and other images, often framed by intricate Celtic knotwork motifs, has been praised by writers through the centuries. Scholar Thomas Cahill notes that, “as late as the twelfth century, Geraldus Cambrensis was forced to conclude that the Book of Kells was “the work of an angel, not of a man” owing to its majestic illustrations and that, in the present day, the letters illustrating the Chi-Rho (the monogram of Christ) are regarded as “more presences than letters” on the page for their beauty (165). Unlike other illuminated manuscripts, where text was written and illustration and illumination added afterwards, the creators of the Book of Kells focused on the impression the work would have visually and so the artwork was the focus of the piece.

Origin & Purpose

The Book of Kells was produced by monks of St. Columba's order of Iona, Scotland, but exactly where it was made is disputed. Theories regarding composition range from its creation on the island of Iona to Kells, Ireland, to Lindisfarne, Britain. It was most likely created, at least in part, at Iona and then brought to Kells to keep it safe from Viking raiders who first struck Iona in 795, shortly after their raid on Lindisfarne Priory in Britain.

A Viking raid in 806 killed 68 monks at Iona and led to the survivors abandoning the abbey in favor of another or their order at Kells. It is likely that the Book of Kells traveled with them at this time and may have been completed in Ireland. The oft-repeated claim that it was made or first owned by St. Columba (521-597) is untenable as the book was created no earlier than c. 800, but there is no doubt it was produced by later members of his order.

The work is commonly regarded as the greatest illuminated manuscript of any era owing to the beauty of the artwork and this, no doubt, had to do with the purpose it was made for. Scholars have concluded that the book was created for use during the celebration of the mass but most likely was not read from so much as shown to the congregation.

This theory is supported by the fact that the text is often carelessly written, contains a number of errors, and at points certainly seems an afterthought to the illustrations on the page. The priests who would have used the book most likely already had the biblical passages memorized and so would recite them while holding the book, having no need to read from the text.

Scholar Christopher de Hamel notes how, in the present day, “books are very visible in churches” but that in the Middle Ages this would not have been the case (186). De Hamel describes the rough outline of a medieval church service:

There were no pews (people usually stood or sat on the floor), and there would probably have been no books on view. The priest read the Mass in Latin from a manuscript placed on the altar and the choir chanted their part of the daily office from a volume visible only to them. Members of the congregation were not expected to join in the singing; some might have brought their Books of Hours to help ease themselves into a suitable frame of mind, but the services were conducted by the priests. (186)

The Book of Kells is thought to have been the manuscript on the altar which may have been first used in services on Iona and then certainly was at the abbey of Kells. The brightly-colored illustrations and illumination would have made it an exceptionally impressive piece to a congregation, adding a visual emphasis to the words the priest recited while being shown to the people; much in the way one today would read a picture book to a small child.

Continue reading...

480 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ancient Celtic Sculpture

The sculpture of the ancient Celts between 700 BCE and 400 CE is nothing if not varied as artists across Europe developed their own ideas and borrowed what interested them from neighbouring cultures. Early Celtic stone and wood sculptures focus on the human form, especially heads. Such works usually represent gods and heroic warrior figures but are often abstract with typical facial features being lentoid eyes, a bulbous nose, and swept-back hair. Animals, both real and imagined, were another favourite subject, especially in miniature form in metal to adorn all manner of objects such as cauldrons, chariots, helmet crests, and jugs. Vegetal designs and swirling complex lines added extra decoration to objects and became a feature that stayed with Celtic art as it developed through the medieval period. Celtic art, in general, has enjoyed a tremendous revival from the 19th century CE up to the present day and many of the motifs which are so quintessentially 'Celtic' have their origins in the artworks produced 2,000 years ago.

Themes

The ancient peoples who spoke the Celtic language occupied territories from Iberia to Bohemia through the 1st millennium BCE and several centuries into the 1st millennium CE. The Celts in any particular area of western and central Europe had no concept they were part of a wider culture with similar approaches to religion and culture. Then, like many other long-lasting cultures, the sculpture of the Celts evolved over time, receiving influences from the cultures in the Near East and the Greeks, Etruscans, Scythians, Thracians and Romans, and, of course, from other Celts. Any treatment of ancient Celtic art is obliged, therefore, to be a general one. A further difficulty is that the Celts left very few written records and so we have no commentaries from the creators themselves on what inspired their art, what their art was intended to represent, or how it was to be used. We must judge Celtic art largely by examining only the art objects themselves and the contexts in which they have been rediscovered.

Despite these problems of definition and study, there are certainly some common themes which are expressed in Celtic sculpture wherever pieces have been found. Further, Celtic art is not restricted to prestige items but is found everywhere from large figure sculptures in stone to the humblest of clothing pins; even such highly functional items as wine flagons and fire-dogs (used to roast meat on) were embellished with ornate heads of animals.

Three subjects stand out as being of particular interest to ancient Celtic sculptors: Gods, warriors, and animals. Sculptures are rarely life-size, but this may be because examples have simply not survived. In addition, it is the head which seems to have captured the Celtic imagination most of all. Heads were considered the containers of the soul and so were especially important in Celtic religion and warfare (where they were collected as trophies). It is not surprising, then, to see the head dominate Celtic sculpture. Human heads, and many of the animals in Celtic art, are typically stylized, they often have swept-back hair, a bulbous nose, and lentoid eyes. Over time, the Celtic love of heads in sculpture seems to have diminished and been replaced by other forms but they are, nevertheless, still seen in engraved areas of other objects where they are surrounded by a camouflage of foliage and linear motifs, often, too, rendered in a highly abstract manner but visible to the trained eye.

Continue reading...

241 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Neat!

This map illustrates the vibrant trade networks of the eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age (circa 1500–1200 BCE), highlighting an era of growing interconnectivity among major powers. Goods, ideas, and diplomatic contacts flowed across land and sea, linking Egypt, the Hittite Empire, Mesopotamia, the Levant, and the Mycenaean world. These exchanges fostered a complex web of economic…

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Europe Transformed

In the span of just 35 years, from 1914 to 1949, Europe underwent a profound transformation. The era was marked by World War I, the collapse of empires, and the rise of powerful ideologies like fascism and communism. This period, which culminated in World War II and the subsequent rebuilding of Europe, reshaped the continent's borders and political structures, laying the groundwork for the modern Europe we know today. One surprising aspect is how these events, driven by both war and ideological shifts, created the foundation for contemporary Europe's political landscape.

Key Facts

First World War (1914-1918): Led to the collapse of empires such as the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires.

Between the Wars: Saw the rise of fascist Italy under Mussolini and Nazi Germany under Hitler.

Second World War (1939-1945): Involved a global conflict with far-reaching consequences, including the formation of the United Nations.

Post-War Era (1945-1949): Began with the division of Europe into Eastern and Western blocs during the Cold War.

Historical Context

The period between 1914 and 1949 was pivotal for Europe as it transitioned from a continent dominated by traditional empires to one where new ideologies held sway. The aftermath of World War I created a power vacuum that allowed fascist and communist regimes to flourish.

Historical Significance

The events of this era set the stage for modern Europe by establishing the political and geographical structures that still influence the continent today. The formation of the European Union, for instance, was partly a response to the devastating effects of conflict in this period, as nations sought to promote peace through cooperation.

Learn More: Europe 1914–1949: History Maps of the World Wars

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ur

Ur was a city in the region of Sumer, southern Mesopotamia, and its ruins lie in what is modern-day Tell el-Muqayyar, Iraq. According to biblical tradition, the city is named after the man who founded the first settlement there, Ur, though this has been challenged. The city is famous for its biblical associations and as an ancient trade center.

The city's other biblical link is to the patriarch Abraham who left Ur to settle in the land of Canaan. This claim has also been contested by scholars who believe that Abraham's home was further north in Mesopotamia in a place called Ura, near the city of Harran, and that the writers of the biblical narrative in the Book of Genesis confused the two.

Whatever its biblical connections may have been, Ur was a significant port city on the Persian Gulf which began, most likely, as a small village in the Ubaid Period of Mesopotamian history (5000-4100 BCE) and was an established city by 3800 BCE continually inhabited until 450 BCE. Ur's biblical associations have made it famous in the modern-day but it was a significant urban center long before the biblical narratives were written and highly respected in its time.

The Early Period & Excavation

The site became famous in 1922 when Sir Leonard Wooley excavated the ruins and discovered what he called The Great Death Pit (an elaborate grave complex), the Royal Tombs, and, more significantly to him, claimed to have found evidence of the Great Flood described in the Book of Genesis (this claim was later discredited but continues to find supporters). In its time, Ur was a city of enormous size, scope, and opulence which drew its vast wealth from its position on the Persian Gulf and the trade this allowed with countries as far away as India. The present site of the ruins of Ur are much further inland than they were at the time when the city flourished owing to silting of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

From the beginning, Ur was an important trade center owing to its location at a pivotal point where the Tigris and Euphrates run into the Persian Gulf. Archaeological excavations have substantiated that, early on, Ur possessed great wealth and the citizens enjoyed a level of comfort unknown in other Mesopotamian cities.

As with other great urban complexes in the region, the city began as a small village which was most likely led by a priest or priest-king. The king of the First Dynasty, Mesannepadda, is only known through the Sumerian King List and from inscriptions on artifacts found in the graves of Ur.

The Second Dynasty is known to have had four kings but about them, their accomplishments, or the history during this time, nothing is known. The early Mesopotamian writers did not consider it worthwhile to record the deeds of mortals and preferred to link human achievements to the work and will of the gods. Ancient hero-kings such as Gilgamesh of Uruk or those who performed amazing feats such as Etana were worthy of record but mortal kings were not afforded that same level of concern regarding the details of their reigns.

Continue reading...

157 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Assyrian Empire

Imagine an empire that once stretched across what is now Iraq, Turkey, and even into Egypt. This was the Neo-Assyrian Empire, a powerful and sophisticated state in the ancient Near East. Assyria's beginnings trace back to the city of Ashur in Mesopotamia, a hub for wealthy merchants. The region was named after the god Ashur, reflecting the deep connection between the city's name and its divine patronage.

Key Facts

Location: The empire encompassed Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), Asia Minor (modern Turkey), and parts of Egypt.

Language: Initially spoke Akkadian, later adopting Aramaic for its simplicity.

Periods: The empire is divided into three main periods: Old Kingdom, Middle Empire, and the Late Empire (Neo-Assyrian Empire).

Legacy: Still has descendants living in Iran and northern Iraq today.

Historical Context

The Assyrian Empire is significant within the ancient Mesopotamian world. It started modestly at Ashur but grew into one of history's greatest empires, known for its extensive military and bureaucratic achievements.

Historical Significance

The Neo-Assyrian Empire's military strategies and administrative systems allowed it to dominate a vast territory for centuries. Its legacy continues with modern-day Assyrians still living in regions that were once part of the empire, reflecting the enduring impact of this ancient civilization.

Learn More: Assyria

#HistoryFacts#History#TiglathPileserIII#TiglathPileserI#Syria#SargonII#Neo-AssyrianEmpire#Assyria#Ashurbanipal#Ashur#WHE

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Will have to investigate...

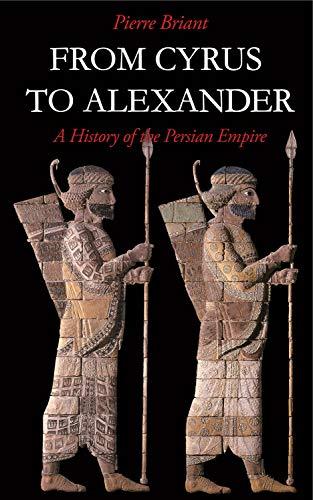

From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire

“From Cyrus to Alexander” by Pierre Briant offers a detailed history of the Persian Empire, focusing on its administration, culture, and military. Briant highlights Persia’s innovations in governance and its tolerant, multicultural approach. The book challenges traditional Greek-centric views, presenting Persia as a complex and influential empire with a lasting historical legacy.

Pierre Briant’s From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire is widely considered the definitive modern history of the Persian Empire. The book covers its origins under Cyrus the Great through its conquest by Alexander the Great. Originally published in French as Histoire de l’Empire Perse in 1996, the English translation made this monumental work accessible to a wider audience, expanding its influence in Near Eastern studies, ancient history, and comparative empires.

Briant’s book stands out for its focus on presenting the Persian Empire as an autonomous civilization rather than through the perspective of its Greek rivals. Historically, much of what Western scholars knew about the Persian Empire came from Greek sources like Herodotus, who often cast Persia as a monolithic enemy. By situating Persia at the center of its own narrative and making extensive use of archaeological findings, inscriptions, and administrative records, Briant counters this Eurocentric bias and offers a view of Persia as a sophisticated, multiethnic empire that left a significant legacy of governance, culture, and trade.

Briant structures the book in a way that mirrors the breadth of the Persian Empire, dedicating each section to a different aspect of the empire’s history, politics, economy, society, and culture. The organisation of the book reflects his emphasis on a systemic, comprehensive examination of the empire.

The early chapters detail Cyrus the Great’s conquests and policies of tolerance, which established a stable, expansive empire. Briant also examines governance, highlighting the balance between central control and local autonomy, the role of satraps, and the unifying use of Aramaic as an administrative lingua franca. Moreover, he analyses the Persian military apparatus, from its elite units like the Immortals to the logistical organisation enabling vast mobilizations by the Persians. He contextualises major conflicts, including the Persian Wars as part of a strategy to stabilize borders and secure valuable territories, rather than dominate all of Greece.

The book also dedicates significant attention to the Persian economy, exploring the empire’s agrarian base, trade networks, and taxation system. He shows how Persia’s economic policies were designed to support both the imperial treasury and local economies, creating a sustainable model that contributed to the empire’s longevity. The culture and religion section highlights Persia’s promotion of cultural integration and religious diversity. Briant shows how Persian art blended regional styles to symbolize royal authority and examines how Zoroastrian traditions coexisted with support for local religions, fostering loyalty among subjects.

One of Briant’s central arguments is that the Persian Empire’s strength lay in its policy of tolerance and inclusion. By allowing conquered peoples to retain their religious practices, local laws, and leaders, the Persians created a sense of allegiance that went beyond military domination. He also highlights the Persian administrative system as a model for later empires, like the Roman and Islamic. Innovations such as standardized taxation, the Royal Road, and an organised postal system enabled centralised yet flexible governance. His analysis of satrapies shows how Persia balanced regional autonomy with loyalty to central authority.

The book repositions the Persian Empire within a global context, highlighting its role in economic and cultural exchange across Asia and the Mediterranean. Through trade and diplomacy with regions like Egypt and Greece, Persia facilitated the flow of ideas and technologies, serving as a prototype for managing diverse populations and complex trade networks.

From Cyrus to Alexander is widely praised for its depth but critiqued for its daunting length and scholarly density. While excelling in its analysis of Persian administration and politics, it offers limited insight into the daily lives of ordinary Persians, focusing more on imperial strategies than social and cultural history.

This monumental work offers a detailed and balanced account of the Persian Empire, redefining its role in world history. Briant’s focus on understanding Persia on its own terms provides valuable insights into its governance, economy, and cultural integration, making it an essential resource for ancient Near Eastern studies.

Continue reading…

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Legend of Sargon of Akkad

The Legend of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE) is an Akkadian work from Mesopotamia understood as the autobiography of Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE), founder of the Akkadian Empire. The earliest copy is dated to the 7th century BCE and was found in the ruins of the Library of Ashurbanipal in the 19th century.

The text, most likely composed c. 2300 BCE, and also known as The Birth Legend of Sargon, describes the king's humble origins and rise to power with the help of the goddess Ishtar and concludes with a challenge to future kings to go where he has gone and do as he has done. Sargon was the founder of the first multinational empire in the world whose reign became legendary, inspiring many tales about him, but very little is known of his life apart from works such as The Legend of Sargon of Akkad and the literary piece Sargon and Ur-Zababa.

Both pieces today are sometimes classified as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature – the world's first historical fiction – in which a famous figure, usually a king, is featured as the main character in a fictional work. This genre appeared around the 2nd millennium BCE and was quite popular, as evidenced by the number of copies found of naru works.

The purpose of naru literature was not to deceive an audience but to impress upon them some important religious or cultural value. In the case of The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, however, the naru genre seems to have been used to establish Sargon as a 'man of the people' who, beginning life as an orphan with nothing, forged his own destiny and established an empire.

The Legend & Naru Literature

Sargon of Akkad was keenly aware of his times and the people he would rule over. He seems to have understood, early on, that the common people resented the nobility and, while he was clearly a brilliant military leader, it was the story he told of his youth and rise to power that exerted a powerful influence over the Sumerians he sought to conquer.

Instead of representing himself as a man chosen by the gods to rule, he presented a more modest image of himself as an orphan set adrift in life who was taken in by a kind gardener and granted the love of the goddess Inanna/Ishtar. According to The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, he was born the illegitimate son of a "changeling", which could refer to a temple priestess of Ishtar (whose clergy were androgynous) and never knew his father.

His mother could not reveal her pregnancy or keep the child, and so she placed him in a basket which she then set adrift on the Euphrates River. She had sealed the basket with tar, and the water carried him safely to where he was later found by a man named Akki, a gardener for Ur-Zababa, the king of the Sumerian city of Kish. In creating this legend, Sargon carefully distanced himself from the kings of the past (who claimed divine right) and aligned himself with the common people of the region rather than the ruling elite.

The Legend, as noted, is considered by some scholars today as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature, but it is unknown whether it would have been understood that way in its time. Scholar O. R. Gurney defines the genre and its origin:

A naru was an engraved stele, on which a king would record the events of his reign; the characteristic features of such an inscription are a formal self-introduction of the writer by his name and titles, a narrative in the first person, and an epilogue usually consisting of curses upon any person who might in the future deface the monument and blessings upon those who should honour it. The so-called "naru literature" consists of a small group of apocryphal naru-inscriptions, composed probably in the early second millennium B.C., but in the name of famous kings of a bygone age. A well-known example is the Legend of Sargon of Akkad. In these works, the form of the naru is retained, but the matter is legendary or even fictitious. (93)

The extant copy, made long after Sargon's death, conveys the story Sargon would have presented regarding his birth, upbringing, and reign. Naru pieces such as The Legend of Cutha or The Curse of Agade use a well-known historical figure (in both these cases Naram-Sin, Sargon's grandson) to make a point concerning the proper relationship between a human being (especially a king) and the gods. Other naru literature, such as The Great Revolt and The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, tell a tale of a great king's military victory or origin. In Sargon's case, it would have been to his benefit, as an aspiring conqueror and empire builder, to claim for himself a humble birth and modest upbringing.

Continue reading...

151 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eyewitness Accounts of the Holocaust

The Holocaust was the murder of 6 million Jewish people by the SS, Gestapo, and other organisations of Nazi Germany and its allies in the years prior to and through the Second World War (1939-45). Innocent men, women, and children were shot in mass executions, or, if not too young or too old, they were sent to labour camps where they worked until they could do so no longer. The ultimate fate of millions was to die in the gas chambers of extermination camps like Auschwitz in occupied Poland.

In this article, accounts are presented by those who witnessed the Holocaust genocide firsthand, both its victims and those involved in its execution who were obliged to give evidence in, for example, the post-war Nuremberg trials of 1945-6.

Unburied Corpses, Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp

Wislon-Oakes - Imperial War Museums (CC BY-NC-SA)

The Nazis & the Jews

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) established himself as the dictator of Nazi Germany in 1933, and he identified Jewish people as the main enemy of the state. Based on dubious and inconsistent racial theory as propounded by such Nazi figures as Alfred Rosenberg (1893-1946), Hitler and the Nazi Party began a propaganda campaign against German Jews, which presented them as an inferior race who were holding Germany back from achieving its full economic potential.

Hitler wanted to remove all Jews from German territory, but the first step was to identify who exactly was a Jew. The 1935 Nuremberg Laws loosely identified Jews since even having a single Jewish grandparent placed an individual in that category. A series of 'solutions' to what Hitler called the "Jewish problem" were rolled out, such as encouraging emigration and persecuting Jewish business owners. Jews were then attacked in such pogroms as the Kristallnacht of November 1938. Next, Jews were rounded up and obliged to live in segregated areas such as ghettos in cities or in concentration camps. Jews were deprived of citizenship and other basic rights.

From 1942, the Nazis began what was secretly described as the 'Final Solution', that is the plan to murder all European Jews. Jews were transported to labour camps where they worked on state projects until they died from disease, extreme malnutrition, or physical exhaustion. Other Jews, and those who could no longer work or were too young or too old to work, were transported directly to death camps like the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex in occupied Poland where they were killed in gas chambers and their remains were communally cremated. Jews were not the only victims since the Nazis also targeted Romani people, Communists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Freemasons, homosexuals, political rivals, prisoners of war, and those with physical or mental disabilities, amongst others. In addition, hundreds of thousands more victims were murdered in mass executions in occupied territories during the Second World War by mobile killing squads known as Einsatzgruppen. The Jews made up by far the majority of those killed, and it is estimated that 6 million died in what is today called the Holocaust. The sheer scale of the Nazis' programme means that determining the precise number of victims is not possible.

Arrested Jews, Baden-Baden

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-86686-0008 (CC BY-SA)

Hugh Greene, a British newspaper journalist, recalls what he saw of the Kristallnacht in 1938:

I was in Berlin at that time and saw some pretty revolting sights – the destruction of Jewish shops, Jews being arrested and led away, the police standing by while the gangs destroyed the shops and even groups of well-dressed women cheering.

(Holmes, 42)

Avraham Aviel, a Polish Jew and survivor of a mass execution, gives the following account of his experience in May 1942:

We were all brought close to the cemetery at a distance of eighty to a hundred metres from a long, deep pit. Once again everybody was made to kneel. There was no possibility of lifting one's head. I sat more or less in the centre of the town people. I looked in front of me and saw the long pit then maybe groups of twenty, thirty people led to the edge of the pit, undressed probably so that they should not take their valuables with them. They were brought to the edge of the pit where they were shot and fell into the pit, one on top of another.

(Holmes, 319)

An anonymous survivor from a ghetto massacre in Lviv, Ukraine, in August 1942 gives the following description of its aftermath:

I went with my mother to the office of the Jewish community regarding an apartment and there in the light breeze, dangled the corpses of the hanged, their faces blue, their heads tilted backward, their tongues blackened and stretched out. Luxury cars raced in from the center of the city, German civilians with their wives and children came to see the sensational spectacle, and, as was their custom, the visitors enthusiastically photographed the scene. Afterwards the Ukrainians and Poles arrived by with greater modesty.

(Fiedländer, 436)

Nazi Classification of Jewish People

VolksVeritas (CC BY-SA)

Rivka Yoselevska, a Polish Jew, describes her experience and that of her family in the Hansovic ghetto massacre in August 1943:

Some of the younger ones I got out naked covered with blood…I was still alive. Where should I go? What should I do?

(Holmes, 320-1)

The SS lieutenant-colonel Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962), in charge of the Final Solution's transportation requirements, here lies to Jews to make sure they do not create trouble as they are transported by train from a ghetto to the concentration camps:

Jews: You have nothing to worry about. We want only the best for you. You'll leave here shortly and be sent to very fine places indeed. You will work there, your wives will stay at home, and your children will go to school. You will have wonderful lives.

(Bascomb, 6)

The death camps were deliberately located in remote Poland to provide the Final Solution project more secrecy. Rudolf Höss (1901-1947), a camp commandant at Auschwitz, stated:

We were required to carry out these exterminations in secrecy, but of course the foul and nauseating stench from the continuous burning of bodies permeated the entire area and all of the people living in the surrounding communities knew that exterminations were going on at Auschwitz.

(Neville, 49)

New Arrivals at Auschwitz

Bernard Walter (Public Domain)

The typical conditions of the train journeys to the camps are described here by Avraham Kochav, an Auschwitz survivor:

There were twenty to twenty-five cars in every train…I heard terrible cries. I saw how people attack other people so as to have a place to stand, how people push each other so that they could stand somewhere or so that they could have air for breathing. It was terribly, terribly stifling. The first to faint were the children, women, old men, they all fell down like flies.

(Holmes, 332)

Zygmunt Klukowski, a Polish hospital director, describes the train journeys for Jewish people sent to the Belzec extermination camp in occupied Poland:

On the way to Belzec the Jews experience many terrible things. They are aware of what will happen to them. Some try to fight back. At the railroad station in Szczebrzeszyn a young woman gave away a gold ring in exchange for a glass of water for her dying child. In Lublin people witnessed small children being thrown through windows of speeding trains. Many people are shot before reaching Belzec.

(Friedländer, 358)

Yaacov Silberstein, a Jewish teenager, describes his arrival at Auschwitz in October 1942:

When we arrived we saw how the Jews were running to the electrified fence. There they stuck. They were tired of life; they could not continue in this fashion.

(Holmes, 330)

Dr Lucie Adelsberger, a prisoner of Auschwitz, describes the processing of new arrivals destined for the labour camps:

We undressed, had our hair cut – no actually our heads were shaved to stubble; then came the showers and finally the tattoos. This was where they confiscated the very last vestiges of our belongings; nothing remained…no written document that could have identified us, no picture, no written message from a loved one. Our past was cut off, erased…

(Cesarini, 656)

Aerial View of Auschwitz

South African Air Force (Public Domain)

Bernd Naumann, a survivor from the Birkenau camp, describes the prevalence of rats in the camp:

They gnawed not only at corpses but also at the seriously sick. I have pictures showing women near death being bitten by rats.

(Neville, 50)

Seweryna Smaglewska, a prisoner in the Birkenau women's camp, describes the living conditions there:

There were no roads, no paths between the blocks. In the depths of these dark dens, in bunks like multi-storied cages, the feeble light of a candle burning here or there flickered over naked, emaciated figures curled up, blue from the cold, bent over a pile of filthy rags, holding their shaved heads in their hands, picking out an insect with their scraggly fingers and smashing it on the edge of the bunk – that is what the barracks looked like in 1942.

(Cesarini, 528)

The SS, which managed the camps, made sure there was a hierarchy amongst the prisoners such as trustees who survived a little longer than the rest by being 'favoured' with certain duties such as burning the bodies in the crematoriums or beating other prisoners. SS Lance Corporal Richard Bock, a guard at Auschwitz-Birkenau, recalls:

A block chief would call out the kapo very fiercely, 'Kapo, come here.' The kapo came over and – boom – he hit the kapo in the face so hard that he fell over…And then he said, 'Kapo, can't you beat them any better than that?' And the kapo ran off and grabbed a club to beat up the prisoner squad quite indiscriminately. 'Kapo, come over here,' he shouted again. The kapo came and he said, 'Finish them off,' and then he went off again and he finished the prisoners off, he beat them to death…a kapo had to beat and club to save his own life.

(Holmes, 325)

Luggage of Auschwitz Victims

Jorge Láscar (CC BY)

Those meant for the gas chambers were often unaware of their fate. Bock describes the procedure that he witnessed with a colleague called Holbinger who was responsible for the Zyklon B tins that would produce the lethal gas:

…the new arrivals had to get undressed, and then the order came, 'Prepare for disinfection'. There were enormous piles of clothing…Lots of them hid their children under the clothes and covered them up and then they shouted, 'Get ready' and they all went out, they had to run naked approximately twenty yards from the hall across to Bunker One. There were two doors standing open and they went in there and when a certain number had gone inside they shut the doors. That happened about three times, and every time Holbinger had to go out to his ambulance and they took out a sort of tin – he and one of his block chiefs – and then he climbed up the ladder and at the top there was a round hole and he opened the little round door and held the tin there and shook it and then he shut the little door again. Then a fearful screaming started up and approximately after about ten minutes it slowly went quiet…They opened the door…then a blue haze came out. I looked in and I saw a pyramid. They had all climbed up on top of each other…They were all tangled, they had to tug and pull very hard to disentangle all these people.

(Holmes, 334-5)

Dov Paisikowic, a Russian-Jewish survivor of Auschwitz, was part of the team responsible for taking bodies out of the chambers, removing valuables such as rings and gold teeth, and then taking the corpses to the crematoria. He recalls:

…the doors were suddenly opened to the gas chambers. People, naked people, started falling out. We were all frightened, no one dared ask what it all was. We were immediately taken to the other side of this house and there we saw hell on this earth – large piles of dead people, and people dragging these dead to a long pit, about thirty metres in length and ten metres in width. There was a huge fire there, with tree trunks. On the other side fat was being taken out of this pit with a bucket.

(Holmes, 335)

Thousands of detainees in the camps were subjected to unnecessary and often horrific medical operations and experiments. One of the most infamous SS doctors was Josef Mengele (1911-1979), who performed all kinds of macabre operations at Auschwitz. Mengele was, though, only one part of a large SS medical team, which operated in many different camps. Dr Franz Blaha, a Czech detainee at the Dachau concentration camp, was obliged to work in this area of Nazi terror, specifically performing autopsies. Blaha reported:

From the middle of 1941 to the end of 1942 some 500 operations on healthy prisoners were performed. These were for the instructions of the SS medical students and doctors and included operations on the stomach, gall bladder and throat. These were performed by students and doctors of only two years' training, although they were very dangerous and difficult….Many prisoners died on the operating table and many others from later complications…These persons were never volunteers but were forced to submit to such acts.

(MacDonald, 59)

Auschwitz Bunks

Bookofblue (CC BY-SA)

Hertha Beese, a Berlin housewife and underground resistance worker, recalls that, unlike the general public, the resistance network was more informed about the camps. She states:

We knew that the concentration camps existed. We also knew where they existed, for example Oranienburg just outside Berlin. We sometimes knew which of our friends were there and we also knew of the cruelties in them right from the beginning.

(Holmes, 315)

Anthony Eden (1897-1977), British Foreign Secretary during WWII, notes:

…as the war progressed some horrifying reports began to come out. At first it was very difficult to assess their accuracy and they were so horrible it was hard to believe they could be true.

(Holmes, 314)

Wynford Vaughn-Thomas, a British journalist, recalls the conditions of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany when it was liberated in 1945:

In the huts typhoid, everything, had broken out and you couldn't hear yourself speak for the death rattle. There were people lying on top of each other, sick, vomiting, withered bodies crawling on their hands and knees…It was sealed off in this dark north German plain and you felt you'd reached the cesspit of the human mind.

(Holmes, 337)

Mass Grave, Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp

H. Oakes-Imperial War Museums (Public Domain)

The British Lieutenant Colonel J. A. D. Johnson described what he saw when he arrived at Bergen-Belsen:

The prisoners were a dense mass of emaciated apathetic scarecrows huddled together in wooden huts, and in many cases without beds or blankets, and in some cases without any clothing whatsoever…There were thousands of emaciated corpses in various stages of decomposition lying unburied. Sanitation was to all intents and purposes nonexistent.

(Cesarini, 759)

Hans Stark, Gestapo staff member at Auschwitz, stated, like so many others, that he had merely been following orders:

I took part in the murder of many people…I believed in the Führer, I wanted to serve my people. Today I know that this idea was false. I regret the mistakes of my past, but I cannot undo them.

(Neville, 57)

Rabbi Frankforter, who died in the Holocaust, which Jewish people often call the Shoah or Ha-Shoah in Hebrew, gave this last wish to survivor Yaacov Silberstein:

You are still young and you will remain alive. I have only one request for you that you should never let people forget. Tell everyone what they did to us at this small camp, in Buchenwald. Wherever you go tell this, also to your children so that they should pass it on. To remember and not to forget.

(Holmes, 339)

Continue reading...

182 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jezebel

Jezebel (d. c. 842 BCE) was the Phoenician Princess of Sidon who married Ahab, King of Israel (r. c. 871 - c. 852 BCE) according to the biblical books of I and II Kings, where she is portrayed unfavorably as a conniving harlot who corrupts Israel and flaunts the commandments of God.

Her story is only known through the Bible (though recent archaeological evidence has confirmed her historicity) where she is depicted as the evil antagonist of Elijah, the prophet of the god Yahweh. The contests between Jezebel and Elijah are related as a battle for the religious future of the people of Israel as Jezebel encourages the native Canaanite polytheism and Elijah fights for the monotheistic vision of a single, all-powerful male god.

In the end, Elijah wins this battle as Jezebel is assassinated by her own guards, thrown from a palace window to the street below where she is eaten by dogs. Her death, the biblical authors note, was prophesied earlier by Elijah and is shown to have come to pass precisely according to his words and, so, in accord with the will of Elijah's god.

Her name has become synonymous with the concept of the evil seductress owing to the interpretation of some of her actions (such as putting on make-up in order to, allegedly, seduce her adversary Jehu, who is anointed by Elijah's successor, Elisha, to destroy her) and calling a woman a “jezebel” is to label her as sexually promiscuous and lacking in morals.

Recent scholarship, however, has tried to reverse this association and Jezebel is increasingly recognized as a strong woman who refused to abide by what she saw as the oppressive nature of her husband's religious culture and tried to change it.

Jezebel's Changing Reputation

The story as given in I and II Kings presents Jezebel as an evil influence from the moment of her arrival in Israel who corrupts her husband, the court, and the people by trying to impose her “godless” beliefs on the Chosen People of the one true god. I Kings 16: 30-33 presents King Ahab as a wicked king seduced by the corrupting influence of his new wife and is an audience's introduction to the story:

Ahab, son of Omri, did more evil in the eyes of the Lord than any of those before him. He not only , but he also married Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal, king of the Sidonians, and began to serve Baal and worship him. He set up an altar for Baal in the temple of Baal that he built in Samaria. Ahab also made an Asherah pole and did more to arouse the anger of the Lord, the God of Israel, than did all the kings of Israel before him.

Traditionally, the story of Jezebel is one of a corrupting influence on a king who had already shown himself a poor representative of his kingdom's religious culture. The biblical account assumes a reader's knowledge that Jezebel, coming from Sidon, would have worshipped the god Baal and his consort Astarte along with many other deities and also assumes one would know that the polytheism of the Sidonians was comparable to that of the Canaanites prior to the rise of Israel and monotheism in their land. Since monotheism and the kingdom of Israel are presented in a positive light, Jezebel, Sidon, and Ahab are cast negatively.

It could be that the biblical narrative depicts events, more or less, accurately but this view is challenged by modern-day scholarship which increasingly leans toward a new interpretation of the clash between Jezebel and Elijah as demonstrating the conflict between polytheism and monotheism in the region during the 9th century BCE. In this interpretation, Jezebel is understood as a princess, the daughter of a king and priest, trying to maintain her cultural heritage in a foreign land against a religion she could not accept. The historian and biblical scholar Janet Howe Gaines comments:

For more than two thousand years, Jezebel has been saddled with a reputation as the bad girl of the Bible, the wickedest of women. This ancient queen has been denounced as a murderer, prostitute and enemy of God, and her name has been adopted for lingerie lines and World War II missiles alike. But just how depraved was Jezebel? In recent years, scholars have tried to reclaim the shadowy female figures whose tales are often only partially told in the Bible. (1)

Although she has been associated with seduction, depravity, and harlotry for centuries, a more accurate understanding of Jezebel emerges as one considers the possibility she was simply a woman who refused to submit to the religious beliefs and practices of her husband and his culture. The recent scholarship, which has led to a better understanding of the civilization of Phoenicia, the role of women, and the struggle of the adherents of the Hebrew god Yahweh for dominance over the older faith of the Canaanites, suggests a different, and more favorable, picture of Jezebel than the traditional understanding of her. The scholarly trend now is to consider the likely possibility she was a woman ahead of her time married into a culture whose religious class saw her as a formidable threat.

Continue reading...

152 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was surprised a few months ago to learn that the Silk Roads are actually a lot younger than I expected. I thought they were prehistorical like the Spice Roads. But reading Peter Frankopan's The Silk Roads, a while back, I learned that they didn't come to be until after Alexander the Great's conquests of the Persian Empire and some of the kingdoms to the east of it. The Han Dynasty which was in charge at the time soon discovered that there was a huge market for silks to the west, and started sending their silk merchants in that direction.

This map illustrates the Silk Road in the late 8th century, a vital network of trade and cultural exchange across Eurasia. In the east, the Tang Dynasty controlled much of the Silk Road, linking China to the trade networks of Central and South Asia. In the west, the Abbasid Caliphate, with Baghdad at its center, integrated Silk Road commerce into the broader Islamic economy, extending connections…

144 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Electrical Telegraph

The Electrical Telegraph was invented in 1837 by William Fothergill Cook (1806-1879) and Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875) in England with parallel innovations being made by Samuel Morse (1791-1872) in the United States. The telegraph, once wires and undersea cables had connected countries and continents, transformed communications so that messages could be sent and received anywhere in just minutes.

Telegraph Pioneers

The idea of sending signals from one distant place to another has been in use since antiquity, notably with towers using fire beacons. Ships have long used a system of flags (semaphore) to communicate beyond shouting distance. These methods, though, were limited to only very important communications, for more mundane messages people had to use horse-riding messengers that could take several days or even weeks to reach their intended recipient.

The Italian Alexander Volta (1745-1827) invented the electric battery in 1800, necessary for a telegraph machine to be operated anywhere. Then the Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851) created the first electromagnet in 1825. Ørsted's discovery that an electrical current flowing in a conductor can create a magnetic field – which he noted when observing the effect on a magnetic compass on his desk – was crucial to the telegraph machine since this was the answer to the problem of how to make electrical impulses visible in the form of a moving needle. The French physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) worked to create a theory that explained the relationship between an electrical current and magnetism. The first electric motor was developed by the Englishman Michael Faraday (1791-1867) in 1821. With all of these scientific discoveries put together, inventors now had the theoretical means to send electrical impulses through a wire and then see the effect at the other end. The trick was just how to create a working machine capable of sending and receiving these impulses over long distances and a code by which such impulses could be transformed into words.

Continue reading...

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

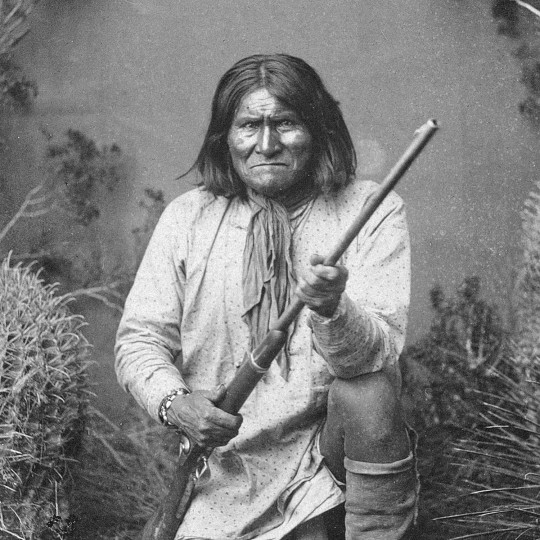

Geronimo

Geronimo (Goyahkla, l. c. 1829-1909) was a medicine man and war chief of the Bedonkohe tribe of the Chiricahua Apache nation, best known for his resistance against the encroachment of Mexican and Euro-American settlers and armed forces into Apache territory and as one of the last Native American leaders to surrender to the United States government.

During the Apache Wars (1849-1886), he allied with other leaders such as Cochise (l. c. 1805-1874) and Victorio (l. c. 1825-1880) in attacks on US forces after Apache lands became part of US territories following the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Between c. 1850 and 1886, Geronimo led raids against villages, outposts, and cattle trains in northern Mexico and southwest US territories, often striking with relatively small bands of warriors against superior numbers and slipping away into the mountains and then back to his homelands in the region of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

He surrendered to US authorities three times, but when the terms of his surrender were not honored, he escaped the reservation and returned to launching raids on settlements. He was finally talked into surrendering for good by First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood (l. 1853-1896), under the command of General Nelson A. Miles (l. 1839-1925), in 1886. None of the terms stipulated by Miles were honored, but by that time, Geronimo felt he was too old and too tired to continue running. Geronimo's surrender to Gatewood is told accurately, though with some poetic license, in the Hollywood movie Geronimo: An American Legend (1993).

Geronimo was imprisoned at Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida, before being moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Toward the end of his life, he became a sensation at the St. Louis World's Fair (1904) and President Theodore Roosevelt's Inaugural Parade (1905) as well as other events. Although one of the stipulations of his surrender was his return to his homelands in Arizona, he was held as a prisoner elsewhere for 23 years before dying in 1909 of pneumonia at Fort Sill.

Name & Youth

His Apache name was Goyahkla ("One Who Yawns"), and, according to some scholars, he acquired the name Geronimo during his campaigns against Mexican troops, who would appeal to Saint Jerome (San Jeronimo in Spanish) for assistance. This was possibly Saint Jerome Emiliani (l. 1486-1537), patron of orphans and abandoned children, not the better-known Saint Jerome of Stridon (l. c. 342-420), translator of the Bible into the Vulgate and patron of translators, scholars, and librarians.

Geronimo was born near Turkey Creek near the Gila River in the region now known as Arizona and New Mexico c. 1825. He was the fourth of eight children and had three brothers and four sisters. In his autobiography, Geronimo: The True Story of America's Most Ferocious Warrior (1906), dictated to S. M. Barrett, Geronimo described his youth:

When a child, my mother taught me the legends of our people; taught me of the sun and sky, the moon and stars, the clouds, and storms. She also taught me to kneel and pray to Usen for strength, health, wisdom, and protection. We never prayed against any person, but if we had aught against any individual, we ourselves took vengeance. We were taught that Usen does not care for the petty quarrels of men. My father had often told me of the brave deeds of our warriors, of the pleasures of the chase, and the glories of the warpath. With my brothers and sisters, I played about my father's home. Sometimes we played at hide-and-seek among the rocks and pines; sometimes we loitered in the shade of the cottonwood trees…When we were old enough to be of real service, we went to the field with our parents; not to play, but to toil.

(12)

After his father died of illness, his mother did not remarry, and Geronimo took her under his care. In 1846, when he was around 17 years old, he was admitted to the Council of Warriors, which meant he could now join in war parties and also marry. He married Alope of the Nedni-Chiricahua tribe, and they would later have three children. Geronimo set up a home for his family near his mother's teepee, and as he says, "we followed the traditions of our fathers and were happy. Three children came to us – children that played, loitered, and worked as I had done" (Barrett, 25). This happy time in Geronimo's life would not last long, however.

Continue reading...

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Meroë

Meroe was a wealthy metropolis of the ancient kingdom of Kush in what is today the Republic of Sudan. It was the later capital of the Kingdom of Kush (c. 1069 BCE to c. 350 CE) after the earlier capital of Napata was sacked c. 590 BCE. Prior to that date, Meroe had been an important administrative centre.

The city was located at the crossroads of major trade routes and flourished from c. 750 BCE to 350 CE. Meroe is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. As no one yet has been able to decipher the Meroitic script, very little can be said for certain on how Meroe grew to become the wondrous city written about by Herodotus circa 430 BCE, but it is known that the city was so famous for its wealth in ancient times that Cambyses II of the Persian Achaemenid Empire mounted an expedition to capture it. The expedition faltered long before reaching the city owing to the difficult and inhospitable terrain of the desert (and, according to some claims, may never have been mounted at all). Still, the persistence of the story of Cambyses' expedition suggests the great fame of Meroe as a wealthy metropolis.

The city was also known as the Island of Meroe as the waters flowing around it made it appear so. It is referenced in the biblical Book of Genesis (10:6) as Aethiopia, a name applied to the region south of Egypt in antiquity meaning "place of the burnt-faces". Although there is evidence of overgrazing and overuse of the land, which caused considerable problems, Meroe thrived until it was sacked by an Aksumite king c. 330 CE and declined steadily afterwards.

Egyptian Influence & King Ergamenes

While there was a settlement at Meroe as early as 890 BCE (the oldest tomb discovered there, that of 'Lord A', dates from that year), the city flourished at its height between c. 750 BCE and 350 CE. The Kingdom of Kush, founded with its capital at Napata, was ruled by Kushites (called "Nubians" by the Egyptians) who, early on, continued Egyptian practices and customs and, though they were depicted in art as distinctly Kushite, called themselves by Egyptian titles. The historian Marc Van De Mieroop writes:

Meroitic culture shows much Egyptian influence, always mixed with local ideas. Many temples housed cults to Egyptian gods like Amun (called Amani) and Isis, but indigenous deities received royal patronage as well. A very prominent Nubian god was the lion-deity Apedemak, a god of war whose popularity increased substantially in this period. Local gods were often associated with Egyptian ones: in Lower Nubia, Mandulis, for example, was considered to be Horus's son. Hybridity is also visible in the arts and in royal ideology. For example, kings of Meroe were represented in monumental images on temples in Egyptian fashion but with local elements, such as garments, crowns, and weapons. (338).

In time, however, these practices gave way to indigenous customs and the Egyptian hieroglyphs were replaced by a new system of writing known as Meroitic. The break from Egyptian culture is explained by the ancient historian Diodorus Siculus who writes that in the time before the reign of King Ergamenes (295-275 BCE), it had been the custom for the high priests of the Egyptian god Amun at Napata to decide who became king and to set the duration of the king's reign.

As the health of the king was tied to the fertility of the land, the priests had the power to determine if the sitting king was no longer fit to rule. If they deemed him unfit, they would send a message to the king, understood to be from the god Amun himself, advising him that the time of his rule on earth was completed and that he must die. The kings had always obeyed the divine orders and had taken their own lives for the supposed good of the people. However, Diodorus continues:

who had received instruction in Greek philosophy, was the first to disdain this command. With the determination worthy of a king he came with an armed force to the forbidden place where the golden temple of the Aithiopians was situated and slaughtered all the priests, abolished this tradition, and instituted practices at his own discretion.

The archaeologist George A. Reisner, who excavated the cities of Meroe and Napata, has famously questioned Diodorus' account calling it "very dubious" and claiming that the Ergamenes story was a national myth which Diodorus accepted as historical truth. Since there is no ancient evidence contradicting Diodorus, however, and since there was clearly a significant cultural break between Meroe and Egypt with Ergamenes' reign, most scholars today accept the account of Diodorus as either certain or something close to actual events.

Continue reading...

173 notes

·

View notes