#ApacheWars

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

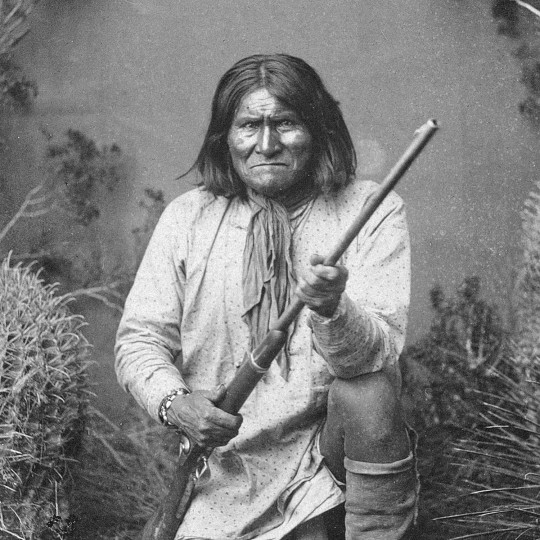

Geronimo

Geronimo (Goyahkla, l. c. 1829-1909) was a medicine man and war chief of the Bedonkohe tribe of the Chiricahua Apache nation, best known for his resistance against the encroachment of Mexican and Euro-American settlers and armed forces into Apache territory and as one of the last Native American leaders to surrender to the United States government.

During the Apache Wars (1849-1886), he allied with other leaders such as Cochise (l. c. 1805-1874) and Victorio (l. c. 1825-1880) in attacks on US forces after Apache lands became part of US territories following the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Between c. 1850 and 1886, Geronimo led raids against villages, outposts, and cattle trains in northern Mexico and southwest US territories, often striking with relatively small bands of warriors against superior numbers and slipping away into the mountains and then back to his homelands in the region of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

He surrendered to US authorities three times, but when the terms of his surrender were not honored, he escaped the reservation and returned to launching raids on settlements. He was finally talked into surrendering for good by First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood (l. 1853-1896), under the command of General Nelson A. Miles (l. 1839-1925), in 1886. None of the terms stipulated by Miles were honored, but by that time, Geronimo felt he was too old and too tired to continue running. Geronimo's surrender to Gatewood is told accurately, though with some poetic license, in the Hollywood movie Geronimo: An American Legend (1993).

Geronimo was imprisoned at Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida, before being moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Toward the end of his life, he became a sensation at the St. Louis World's Fair (1904) and President Theodore Roosevelt's Inaugural Parade (1905) as well as other events. Although one of the stipulations of his surrender was his return to his homelands in Arizona, he was held as a prisoner elsewhere for 23 years before dying in 1909 of pneumonia at Fort Sill.

Name & Youth

His Apache name was Goyahkla ("One Who Yawns"), and, according to some scholars, he acquired the name Geronimo during his campaigns against Mexican troops, who would appeal to Saint Jerome (San Jeronimo in Spanish) for assistance. This was possibly Saint Jerome Emiliani (l. 1486-1537), patron of orphans and abandoned children, not the better-known Saint Jerome of Stridon (l. c. 342-420), translator of the Bible into the Vulgate and patron of translators, scholars, and librarians.

Geronimo was born near Turkey Creek near the Gila River in the region now known as Arizona and New Mexico c. 1825. He was the fourth of eight children and had three brothers and four sisters. In his autobiography, Geronimo: The True Story of America's Most Ferocious Warrior (1906), dictated to S. M. Barrett, Geronimo described his youth:

When a child, my mother taught me the legends of our people; taught me of the sun and sky, the moon and stars, the clouds, and storms. She also taught me to kneel and pray to Usen for strength, health, wisdom, and protection. We never prayed against any person, but if we had aught against any individual, we ourselves took vengeance. We were taught that Usen does not care for the petty quarrels of men. My father had often told me of the brave deeds of our warriors, of the pleasures of the chase, and the glories of the warpath. With my brothers and sisters, I played about my father's home. Sometimes we played at hide-and-seek among the rocks and pines; sometimes we loitered in the shade of the cottonwood trees…When we were old enough to be of real service, we went to the field with our parents; not to play, but to toil.

(12)

After his father died of illness, his mother did not remarry, and Geronimo took her under his care. In 1846, when he was around 17 years old, he was admitted to the Council of Warriors, which meant he could now join in war parties and also marry. He married Alope of the Nedni-Chiricahua tribe, and they would later have three children. Geronimo set up a home for his family near his mother's teepee, and as he says, "we followed the traditions of our fathers and were happy. Three children came to us – children that played, loitered, and worked as I had done" (Barrett, 25). This happy time in Geronimo's life would not last long, however.

Continue reading...

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

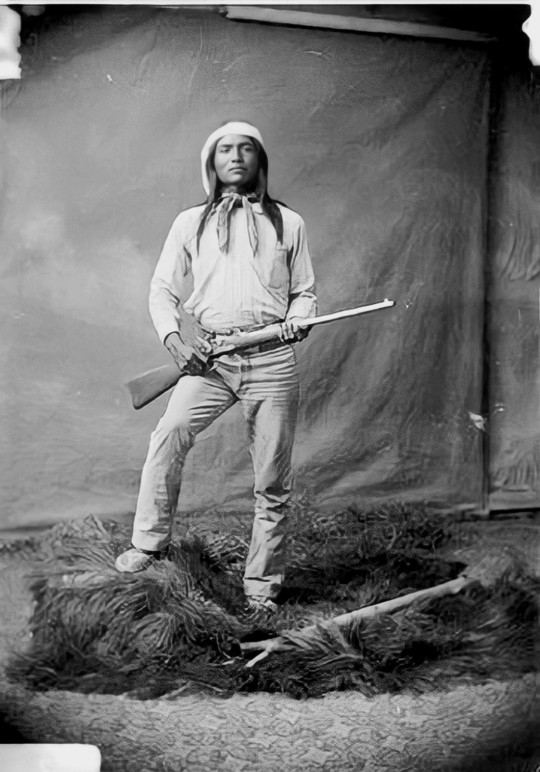

Chief Augustin Vigil of the Jicarilla Apache

~

Circa 1880

#augustinvigil#jicarillaapche#warmspringsapache#1880s#battleofapachepass#apachewars#arizona#newmexico#mexico

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Apache Wars: A Fierce Struggle for Land and Freedom

Image generated by the author

What does it mean to be tied to a piece of land, to feel its pulse beneath your feet, and to carry its stories in your heart? For the Apache people, this connection transcended mere ownership; it was an intrinsic part of their identity. In the late 19th century, as the United States expanded westward, this bond was put to the ultimate test. The Apache Wars were not just a series of military confrontations; they were a profound struggle for land, freedom, and cultural survival against the relentless tide of encroachment.

Native Uprisings: A Land Under Siege

Imagine a sun-soaked desert, the air shimmering with heat, and the rugged mountains rising like ancient guardians over a landscape rich with history. This was the homeland of the Apache, a land they revered as sacred. Yet, as settlers pushed further into these territories, the Apache found themselves facing an existential threat. Their response was not one of submission but of fierce resistance, led by legendary warriors and leaders who refused to allow their way of life to be extinguished.

The Apache's connection to their land was rooted in a profound philosophy: "land is life, and life is land." This belief echoed through the generations, instilling a sense of purpose and resilience in Apache culture. The land was not merely a resource; it represented their identity, their history, and their future. As settlers encroached upon this ancestral territory, the Apache's fight became emblematic of the broader struggle against cultural erasure, a battle for their very essence.

Cultural Significance: The Heartbeat of Apache Identity

At the core of the Apache Wars was a cultural significance that went beyond military tactics. Leaders like Cochise and Geronimo emerged not just as war chiefs but as symbols of resistance, embodying the indomitable spirit of their people. Cochise, with his piercing gaze and commanding presence, rallied his people to protect their lands with a fierce tenacity that resonated through the canyons and valleys of the Southwest. Geronimo, a name that would echo in history, became synonymous with the relentless pursuit of freedom, representing the aspirations and struggles of countless Apache families.

The Apache people had a deep-seated belief that their existence was intertwined with the land. Their ceremonies, stories, and traditions were all steeped in this connection. The sentiment that "the land is our mother; we cannot abandon her" resonated deeply within Apache hearts. It was this unwavering bond that fueled their resistance and inspired them to adapt their strategies against modern military forces.

Historical Context: The Apache Wars Unfold

The Apache Wars spanned several decades, primarily occurring in the late 19th century as various Apache tribes, including the Chihuahua, Western, and Eastern Apache, faced the relentless advance of European settlers and U.S. forces. The westward expansion was driven by a voracious appetite for land and resources, resulting in treaties that were often broken, leading to a cycle of violence and retribution.

Strikingly, the Apache's guerrilla warfare tactics demonstrated their mastery of the rugged terrain. They utilized their intimate knowledge of the land to launch surprise attacks, outmaneuvering forces that were equipped with advanced weaponry. This adaptability showcased their enduring spirit and their determination to assert their rights and preserve their culture.

One significant event during this tumultuous time was the Camp Grant Massacre of 1871, where a group of Apache seeking refuge from the violence was brutally attacked. The massacre underscored the violent tensions between settlers and the Apache, revealing the tragic consequences of broken promises and hostility.

Resistance and Resilience: The Apache Spirit

The Apache Wars were emblematic of a broader fight for identity, land, and freedom. The values of community, resilience, and connection to the earth were deeply ingrained in Apache culture. Leaders like Cochise and Geronimo not only fought against external forces but also instilled in their people the importance of unity and strategic thinking.

In the face of adversity, the Apache spirit remained unbroken. Their storytelling traditions, steeped in lessons from the past, served as a guiding light for modern Apache communities. The narratives of their ancestors, passed down through generations, were not merely tales; they were living reminders of their heritage, instilling a sense of pride and purpose.

One poignant example is the story of a contemporary Apache woman named Kyle, a skilled healer who draws upon the wisdom of her ancestors. In a sacred ritual, she seeks guidance from the spirits of those who came before her, emphasizing unity and strength. This moment encapsulates the essence of the Apache spirit—a spirit that remains unyielding despite historical challenges.

Lessons from the Apache Wars: Resilience and Advocacy

The legacy of the Apache Wars extends beyond historical accounts; it offers critical lessons in resilience and advocacy that resonate in today’s world. Understanding these historical conflicts enhances modern society's appreciation for land and freedom.

Apache wisdom teaches the importance of community and connection. In an era where division often prevails, the Apache example serves as a reminder of the power of unity. By amplifying collective voices and fostering empathy through storytelling, communities can draw upon the strength of their shared experiences.

Moreover, the Apache approach to resilience emphasizes adaptability. Just as they navigated the changing circumstances of their time, modern activists can learn to pivot strategies in pursuit of justice and recognition. The Apache belief in respecting the land aligns seamlessly with contemporary environmental advocacy, emphasizing the interconnectedness of humanity and nature.

Modern Relevance: Ongoing Struggles for Justice

The teachings of the Apache people continue to resonate today, shedding light on enduring struggles for land and freedom. Their philosophies about the bond between people and the earth have become increasingly relevant in contemporary movements focused on environmental sustainability and social justice.

Modern activists, inspired by the spirit of resistance demonstrated during the Apache Wars, are advocating for indigenous rights and cultural preservation. Just as the Apache warriors fought valiantly for their home, today's activists strive to protect their communities and heritage.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars symbolize more than a fight for land; they encapsulate the struggle for identity, heritage, and freedom. The bravery and ingenuity of Apache warriors serve as a reminder of the lengths individuals will go to defend their homes and way of life.

As we reflect on this tumultuous chapter in American history, the Apache spirit shines brightly—a beacon of hope urging us to protect what we cherish and strive for justice. In a world still grappling with issues of land rights and cultural identity, the lessons from the Apache Wars remain pertinent.

In the words of the Apache, "We are not just fighting for ourselves; we are fighting for the future." And as we honor their legacy, it calls upon each of us to continue the fight for justice, equity, and the sacred connection we all share with the land.

AI Disclosure: AI was used for content ideation, spelling and grammar checks, and some modification of this article.

About Black Hawk Visions: We preserve and share timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Historic Events That Happened on Sept 4th #shorts #ytshorts

#youtube#HistoricalEvents WorldHistory thisdayinhistory september4 geronimo apachewars westernromanempire treatyoftordesillas emperortaizong josemig

0 notes

Text

Geronimo and his two nieces standing next to him

~

Chiricahua Apache, circa early 1900s.

#battleofapachepass#apachewars#mexico#newmexico#arizona#nativeamericans#trueamerican#20thcentury#19thcentury#warmspringsapache#chiricahuaapache#Bedonkohe#geronimo#mangascoloradas#baishan#cochise#taza#naiche#nana#perico#juh#victorio#lozen#apachekid#dutchy#alchesay#chato#bonito#sanjuan#chiefchihuahua

1 note

·

View note

Text

Buffalo Calf

~

Jicarilla Apache nation, circa 1880

0 notes

Text

No-talq, circa 1883

~

Chiricahua Apache

#notalq#No-Talq#arizona#newmexico#apache#chiricahua#warmspringsapache#1883#1880s#19thcentury#apachewars#battleofapachepass#nativeamericans#trueamerican#firstamericans

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yanozha; Chiricahua Apache

~

Taken in Florida, circa 1885

#trueamericans

#Yanozha#florida#chiricahua#apache#warmspringsapache#battleofapachepass#apachewars#1885#1880s#mescalero#tontoapache#jicarilla#plainsapache#mangascoloradas#cochise#taza#naiche#victorio#lozen#nana#loco#chato#geronimo#juh#dutchy#apachekid#bonito#baishan#sanjuan#nativeamericans

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl

Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl, more commonly known as Apache Kid, was a White Mountain Apache who was captured by the Yuma people as a child, who was later freed by the U.S. Army where he became a street orphan within the Army camps. In the mid-1870s when he was a teenager, Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl met Al Sieber and was essentially adopted by him, the Chief of the Army Scouts. A few years later, in 1881, Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl enlisted with the U.S. Cavalry as an Indian scout, in a program designed by General George Crook to help quell raids by hostile bands of Apache. By July 1882, owing to his remarkable abilities in the job, he was promoted to sergeant. Shortly thereafter he accompanied Crook on an expedition into the Sierra Madre Occidental. He worked on assignment both in Arizona and northern Mexico over the next couple of years, but in 1885 he was involved in a riot while intoxicated, and to prevent him being hanged by Mexican authorities, Sieber sent him back north.

#theapachekid#Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl#chiricahua#apache#apachescout#apachewars#battleofapachepass#nativeamericans#trueamerican#19thcentury#warmspringsapache#jicarillaapache#victorio#lozen#geronimo#dutchy#juh#bonito#blackknife#ponce#sanjuan#mangascoloradas#nana#cochise#naiche#chato#chiefchihuahua#chiefjamesgarfield

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

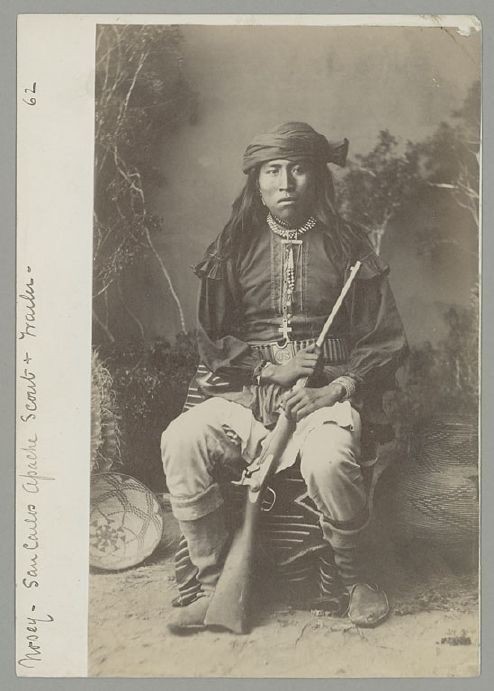

Nosey; San Carlos Apache scout

#nosey#sancarlosapache#apachescout#battleofapachepass#apachewars#arizona#newmexico#mexico#loco#baishan#mangascoloradas#cochise#taza#naiche#nana#victorio#lozen#perico#chato#alchesay#chiefchihuahua#apachekid#dutchy#sanjuan#juh#geronimo#chiefjamesgarfield#nativeamericans#trueamerican#19thcentury

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A young Mescalero Apache boy holding a mirror in his left hand

~

Circa 1888

#mescaleroapache#1888#1880s#battleofapachepass#apachewars#baishan#mangascoloradas#cochise#taza#naiche#victorio#lozen#nana#geronimo#perico#fun#alchesay#dutchy#apachekid#bonito#sanjuan#juh#chato#chiefchihuahua#chiefjamesgarfield

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Domingo; Mescalero Apache

~

Circa 1885

#domingo#mescalero#warmspringsapache#sancarlosapache#tontoapache#jicarilla#chiricahua#battleofapachepass#apachewars#sanjuan#bonito#juh#loco#dutchy#baishan#mangascoloradas#cochise#taza#naiche#nana#victorio#lozen#geronimo#apachekid#chiefchihuahua#alchesay#perico#nativeamericans#trueamerican#19thcentury

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chiricahua Apache boy

~

Circa 1888

#chiricahua#apache#warmspringsapache#arizona#newmexico#1880s#battleofapachepass#apachewars#geronimo#baishan#mangascoloradas#cochise#taza#naiche#victorio#lozen#nana#loco#alchesay#perico#chato#chiefchihuahua#sanjuan#juh#apachekid#dutchy#bonito#nativeamericans#trueamerican#19thcentury

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notchi more known as George Noche, Chiricahua Apache

~

Circa 1886

#noche#notchi#warmspringsapache#chiricahua#apache#apachewars#battleofapachepass#mangascoloradas#geronimo#victorio#lozen

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

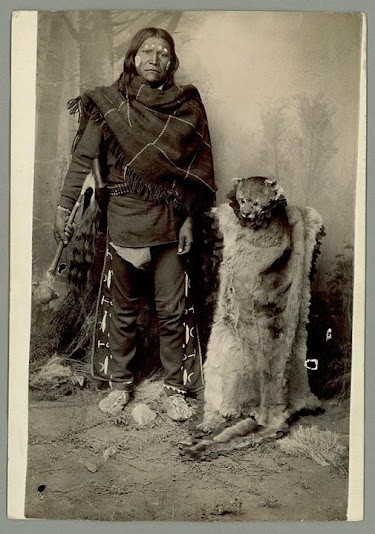

Chato, Subchief of the Chiricahua Apache

~

Circa 1903

#chato#chiricahuaapache#nativeamericans#trueamericans#19thcentury#apachewars#mexico#battleofapachepass#geronimo#loco#victorio#lozen#blackknife#chiefchihuahua#nana#cochise#naiche#mangascoloradas#ponce#theapachekid#dutchy#warmspringsapache

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chasi, a Chiricahua Apache musician playing the fiddle

~

Circa 1886

#chasi#chiricahua#apache#warmspringsapache#arizona#newmexico#1886#1880s#battleofapachepass#apachewars#apachekid#dutchy#bonito#juh#sanjuan#chiefchihuahua#loco#perico#alchesay#chato#geronimo#baishan#cochise#taza#naiche#victorio#lozen#nana#chiefjamesgarfield#nativeamericans

2 notes

·

View notes