#which reminded me i never talked about how the royal families work in evermore

Text

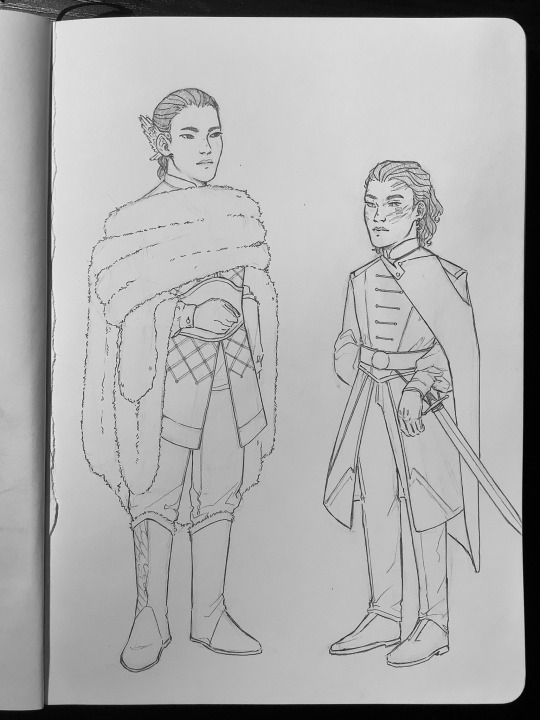

A first rough try at common upper class clothing for royal au Evermore and Palmetto kingdoms respectively! Featuring second King Ichirou and Lord Abram Minyard, naturally

#one day of chats about ichirou/evermore in the au and im BUZZING#theres a lot going on#which reminded me i never talked about how the royal families work in evermore#so expect that soon i hope??#fan art#my art#aftg#all for the game#neil josten#ichirou moriyama#royal au#outfit design#mmmmm ive been worldbuilding. enjoying myself immensely

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lighter Next To Your Coffee Mug IX

The door fell shut and Andrew didn't move for a long moment. This was getting out of hand. Not the part where he had hit Neil. Andrew was no stranger to violence by any means. He knew both sides of it intimately. He had a strangely detached relationship to violence in general. It didn't faze him like it should –except when it did just now. Feeling guilty was something Andrew despised. How many times had he attacked some of the closest people in his life –his family, Kevin, his other teammates –intentionally or by accident without regret? And now, even after spelling it out for the guy, even after telling him ‘I might hurt you’ like some kind of insurance, he felt guilty for nearly breaking his nose. That idiot hadn't even touched him. He had tried to, true, but he hadn’t. He could have stopped. He could have realized at the last second. Could have, would have… didn't matter. He hadn't given him the chance this time, hadn't waited.

‘Do I really have to tell you that I’ve had worse?’ –No, but thanks for the reminder that you compare me to whoever left those scars on your skin. That had hit home. Nice. Look at you, getting in touch with those feelings. Maybe he had been a little shaky after thinking of Drake. Maybe he still was. Andrew took a deep breath and exhaled through his nose. Still there. Fuck him. Getting haunted by the memory of a dead guy.

Drake, his foster brother, who had raped him as a child and once more when Andrew had been twenty, had been killed during his last deployment as a marine. Andrew would have liked to congratulate the man who had finally offed the bastard on a job well done.

Andrew tried to force those memories down once again, but they had already festered in his brain, corrupting his thoughts. He had two options for nights like this. Andrew chose the more unlikely one, because he felt like being unpredictable for a change. He took his phone and called Kevin. The striker picked up on the second ring.

“Andrew?” Noise in the background, somewhere public.

“Where are you?”

“I’m meeting Thea for dinner. Why?” Too bad.

“Nevermind.” He was sure Kevin could hear nothing in his voice. Andrew, on the other hand, could hear in the way Kevin hesitated that his teammate had seen through him though.

“…Should I come home?” It was their unspoken agreement. It had started when they came here to join the US Court. Suddenly, everything had changed; their teammates, the city they lived in, the university dorms they had traded for apartments… everything except themselves. They had dragged their demons along and moved in with them. After sharing a room for so long, it had been strange. Kevin had turned back to alcohol for a while and Andrew had started to self-medicate. One night, they had met at a bar. Kevin had already been drunk and Andrew had dragged him outside and into his car. It had been Kevin who had asked him to stay that night because he couldn't stand the empty apartment.

Andrew had stayed. He had done so three more times during the next two months, and Kevin stopped drinking again. He stayed over twice more since then, but it hadn't solved his drug problem. It just took the edge off sometimes; knowing that he could make the ten-minute drive and have his old roommate under the same roof again. Not tonight though.

“Don’t be an idiot.”

“You sure?” Kevin was many things –arrogant, single-minded, obsessed with the game they played, a sadist on the court –but Kevin wasn’t cruel. Not intentionally, at least. It had been beaten out of him at Castle Evermore. He was loyal, if not always reliable. He would send Thea home tonight if Andrew asked him to, if he so much as hinted at it.

“I’m sure.” Andrew hung up. Option two then. If anyone asked him, Andrew would not admit to having a drug problem. The thought would amuse him though, after years of supervised medication. ‘Chemically imbalanced brain,’ someone had once said to him. Too bad no one knew what a chemically balanced brain in his case looked like. So they had meddled.

It was an open secret that a large percentage of the nation was overmedicated. Popping pills had become the answer to almost every problem. The list of long-term side effects of psychiatric drugs was endless, but while some people were busy adding their findings to the bottom of that list, others were just as busy erasing them at the top. Either way, the damage was done, and Andrew didn't much care about the consequences.

The wooden box standing on the sideboard under his big flatscreen was never empty. Neither was the medicine cabinet in his bathroom. He kept both well stocked. The box didn't look like much. It had once been a gift, part of some kind of advertisement deal, containing a bottle of overpriced scotch. The bottle was long gone but he had kept the box. Grabbing his cigarettes first, Andrew opened the window and leaned against the wall next to it. He gave Drake time to fuck off, until he’d throw the cigarette butt out the window. After that, he’d make him.

Neil lowered his head and sniffed. The bleeding had stopped. He angrily hurried on his way home. People kept looking at him. Well, of course they did. There was blood on his shirt and on his face, and he wore the fitting, dark expression that told of a fight.

He’d just left the station closest to his apartment when his phone buzzed. He pulled it out immediately, looking for the name on the screen that wouldn't leave his thoughts. Andrew, Andrew… The text wasn't from Andrew.

‘Sehen wir uns morgen Abend?’*

The German. He was back already? Neil didn't want to reply but he had to.

‘Ich kann morgen nicht. Sorry.’ He didn't feel sorry at all; not for declining, not for lying about it. He just couldn't face the man right now.

He jogged the last two minutes to his apartment, and fumbled with the keys at the door. He shrugged his jacket off and pulled the dirty shirt over his head as soon as the door closed behind him. The blood on it was already almost dry. Neil went into the bathroom and inspected the damage on his face. His nose looked fine but there was a bruise beneath his left eye. Shit. He washed the blood off his face, left the shirt in the sink to soak in cold water for a while, and stepped into the shower.

His mind returned to the scene at Andrew’s apartment. He had royally fucked that one up. He should have left after the blowjob like Andrew had wanted him to. He should have given the man the satisfaction of getting one step closer to his goal –whatever that might be –and leave everything else for another time. The sound Andrew had made when he had been on top of him… he could still hear it, that half-sob. He could still remember him shuddering. It made something in his gut clench in sympathy.

After cooling his head on his way home, Neil didn't mind the hit he had taken. The fact that Andrew had minded was enough for him to let it go. What remained was the question: would Andrew want to see him again. ‘This whole thing is disgusting.’ He had meant it. The revulsion at that moment had been palpable. Neil closed his eyes and let the water hit his face. Disgusting. Really? All of it? Part of it? Which part? The part where Andrew was paying for a prostitute? The fact that he had issues he couldn't talk about? ‘This whole thing…’ Liar. Liar, liar, liar… Takes one to know one, and Neil was the king among liars. –Or was he?

He had offered Andrew more of the truth than he had given to anyone in years. He kept his lies with the man to a bare minimum. Normally, he would have constructed a fake persona for the goalkeeper after their first meeting, would have given him a false name, a bunch of lies that made up enough of a background story to keep Andrew at a distance and Neil at ease. It was his safety net. The clients didn't find out about him and he kept himself removed. It worked both ways. But he had given Andrew Neil. While Neil was only part of Nathaniel Wesninski, it was the part Neil had chosen to keep. He had tried to outrun the rest of him. What had he been thinking to give Andrew that name?

Because Andrew Minyard was special to him. His Andrew Minyard was special, he reminded himself. The goalkeeper of the US Court, the face showing up in magazines, the prodigy standing in the goal, the man who had been at Kevin Day’s side since the day those two met in Palmetto. The man he envied, the guy who had everything.

This Andrew Minyard was nothing like him. Then why did he get attached to this version of him too? It should have been the opposite. It should have shattered his dreams. Expectations were a silly thing. All they ever did was disappoint.

Maybe it was all over now. If Andrew didn't contact him again, this would be the end of it. The thought alone woke something in him that had the familiar taste of panic to it. Actual fucking fear, dreadful and promising emotional pain. Why? Because he had gone too far and now he was trapped.

Neil shut the water off and stepped out of the shower. He left the shirt where it was; he would wash it later. He grabbed a towel and dried himself off half-heartedly, then flung the towel onto the bed. He got dressed in sweatpants and a hoody and went over to his fridge to make himself something to eat. The sandwich was gone before he even realized it. He couldn't appreciate his food tonight. His thoughts where a mile away. He felt restless and tired at the same time. Eyeing his racquet over his shoulder, he gave in to the familiar pull of his obsession. Better than drugs, better than sex, Exy would always be his way out of his own head. The day his body wouldn’t let him play anymore would be the day he wanted to die. Neil turned around, grabbed his keys, tied his shoes, and took a ball and his racquet with him on his way out, letting the door fall shut behind him.

Two hours and what felt like a never-ending repetition of drills later, he opened the same door again. He closed it none too gently and kicked off his shoes. He left the ball there but couldn't let go of his racquet. He was still thinking of him. He had gone through every drill he knew, had run suicide sprints and had taken shots at an empty goal until his arms screamed in protest at him. What made things worse was that he now was actually worrying about Andrew. How fucking stupid. He had thought about the phone he had left at his apartment, wondering if he would miss a text from the goalkeeper, while all his thoughts should have been on his practice. Of course there was nothing. Why would there be? Because he wanted it to be there.

He twirled the racquet in his right hand, made it spin, and grabbed it again. Go to bed, he told himself. Sleep it off. He took another quick shower to get rid of the sweat he had worked up. The moment his head touched his pillow he already knew that sleep wouldn't come easily tonight. By the time he gave up, it was almost midnight.

Very well aware of the fact that he might be about to make the biggest mistake in his life, Neil got up and dressed again and left his apartment.

Forty five minutes later he was standing across the street from Andrews place. He made sure he was standing on the illuminated sidewalk visible from Andrew’s living room when he texted the man.

‘Can I come up?’ He waited. Andrew was home and still awake. He could see the lights burning in those windows and it didn’t even take a minute for Andrew to show up behind one of them. Neil had one hand in his pocket, a plastic bag dangling from his wrist. He cocked his head and looked up at the goalkeeper.

Andrew kept watching him but didn’t write back. Neil shrugged exaggeratedly at him. It was Andrew’s call. He saw the goalkeeper nodding at his door over his shoulder before he turned around and vanished from Neil’s sight. Hurrying inside, Neil took the waiting elevator up and found Andrew leaning against his half open door, waiting. He still wore the same clothes, had the same messy hair, and Neil was sure he hadn’t left this place since they had seen each other earlier.

“Hey,” he offered in way of greeting and studied the man in front of him. You are a mess, aren’t you? Even in the dark hallway, Andrew’s pinpoint pupils spoke volumes. Those hazel eyes just stared at him in their unnerving way. Neil smiled a little and lifted the bag he was carrying. “I brought bribes.” Sadly they didn’t have Andrew’s favorite flavor, but cookie dough caramel ice cream still sounded a lot like a child’s sugar overload dream to him. Andrew didn’t move and remained silent. Neil sighed a little.

“Look, I came to apologize. What happened tonight has been my fault. I shouldn’t have pushed you like that. I was out of line. I’m sorry.” He hated the thought that Andrew was alone at night getting high because of something he had done. “Just…” He shrugged helplessly. “I don’t know. That’s it I guess. I thought you might not call again, so I came here to tell you. I’m sorry, Andrew.” That was all he had to offer and maybe it was not enough. I wish I could read your mind right now. He lowered his head a little and put his hands back into his pockets, as he took a step back. At the same time, Andrew backed off too and opened the door wider. Neil hesitated, waited for either an invitation or a dismissal, but Andrew simply turned around and went back inside, leaving the door open. Neil followed him, saw the whiskey glass in the goalkeeper’s hand that had be hidden behind the door. Andrew emptied it and left it on the breakfast bar.

Neil took a look around, found the open wooden box on the coffee table, and saw the little plastic bags and pill bottles inside. Andrew saw him looking and smirked. He reached out a hand and Neil handed the bag over. Inspecting its contents, Andrew went into the kitchen and grabbed two spoons. He came back and climbed onto the sofa, grabbing one of the two pints and opened it. Neil watched him eat the ice cream, looked again at the bottle of painkillers next to the half empty bottle of scotch on the coffee table. Geez, Andrew… His dismay must have been visible on his face because the goalkeeper tapped the spoon against his lips while he studied Neil. He extended one of his legs and closed the wooden chest with his bare foot. The sound of it snapping shut was unpleasantly loud in the too quiet apartment. Neil slowly made his way over to the sofa.

“Tongue-tied?” he asked, because Andrew always kept too much to himself and that was fine when they were doing business, because that was Andrew’s choice after all. But this was a social call and so Neil could be a little selfish.

“Black-eyed?” Andrew answered and Neil touched the bruise over his left cheekbone.

“It’s fine,” he replied. Well, maybe it wasn’t fine. Bruises on his face couldn't be hidden. People noticed, meaning people paid him more attention. But it would fade. He shrugged, ran his fingers through his hair, and thought carefully about his next words. He sat down at the other end of the sofa, watching out for pieces of broken glass but they were gone.

“I won’t do anything with you tonight, even if you wanted to,” he said slowly. Andrew had returned his gaze back to his ice cream as soon as fine had come from Neil’s lips. “But I’m going to tell you something, because I think you might actually need to hear this.” He waited and said nothing, until Andrew finally looked at him again and he had his undivided attention.

“There is nothing you need to hide from me. You can tell me about anything you want to do or have done to you. It doesn't matter what anyone else thinks about it. It doesn't matter if it will turn out the way you thought it would. If I agree to do something with you and I do it wrong, that’s on me. You can tell me and I’ll try to make it right. But you never have to justify anything you think you did wrong in front of me. As long as we both respect our limits, I’ll never judge you.”

And when Andrew started to say something, he didn't let him. “Andrew. Just listen, okay? You pay me for this. I’m not a thing but you can use me to do anything we agree on. And if that means making mistakes, then that’s okay too. Because this,” he motioned between the two of them, “is just between us. It’s our business and I’m the last person you need to feel ashamed in front of.” He could already see that Andrew didn't want to hear any of this. But maybe he needed to, and Neil would give it time to let it actually sink in. Andrew could glare at him all he wanted. He just couldn't stand the man looking like this. Even hate was better than this.

“You say you hate me. Admit it, that’s what you are thinking right now.”

“There is nothing to admit. I do hate you.” Neil smiled at him and it made Andrew even angrier.

“That’s fine. Hate me all you want. I’ll still do this with you. Just tell me to back off or take a break, tell me to go and sit in the corner or wait in the next room or whatever. Tell me to wait outside for all I care. Just don’t feel like you need to run from me. Okay?”

“Are you done now?” He really didn't want to hear this right now. But Neil knew he would think about it.

“Yes, I’m done. You can throw me out now.”

“And if I don’t?” he asked after a moment.

“I guess, then we’ll have to find out if that thing works and if you are any good at it,” Neil said and nodded at Andrew’s gaming console below the flatscreen. Andrew followed his gaze and took another spoonful of ice cream. He sucked on it before he answered.

“Go ahead. I’ll pass. My reflexes are a little …inhibited at the moment.” Neil glared at the box. He usually didn't care what people did to themselves, but Andrew was an athlete he admired and it pissed him off to see him like this.

“You should be careful with those. The long term–“

“Geez, thanks Kevin. The last thing I ever wanted were two of you,” Andrew sighed and rubbed his eyes. “Shut up, I think I know enough about side effects.” Neil glared at him. “Go ahead,” Andrew said again and made a gesture at the general direction of the console.

“We can do something else, if you like. We don’t have to play,” Neil offered. It had just been a suggestion to lighten the mood. Andrew leaned back and put both feet on the table, pressing back against the cushions until he found a comfortable position.

“I thought you came here on your own time.”

“I did.” Neil watched him.

“Then, for god’s sake, just do whatever you want,” Andrew sighed. “Don’t look at me for directions.” Neil hummed in response and started the console to have a look at Andrew’s game collection. He had played before but never bought anything himself. After he found something he liked, Neil leaned back and watched the opening video before he let the intro teach him a few skills. Andrew seemed content with just watching for now. It came rather unexpected, when he broke the silence between them suddenly.

“Do you really get off on pain?” Neil blinked but didn’t face him. He kept playing, asking himself what had brought this on.

“Why do you ask?”

“You don’t seem to have any problem when you are doing it with me.” Andrew licked on his spoon again. Neil raised his eyebrows and smirked a little.

“Yeah, well, that’s because it’s you, Minyard.” Andrew glared at him.

“Gross. So what? You want me in my gear to fulfill your obsessive fantasies?”

“Damn, that would be so hot,” Neil joked. Andrew looked unimpressed. “I’m kidding,” the dark haired man chuckled. “Can I see your racquet though? The US court gets theirs custom made, right? That must be awesome!”

“Is that all?” Andrew asked in a bored tone.

They fell silent again, as Neil got swamped with zombies during a boss fight. His character nearly died.

“Zombie guard to your right,” Andrew told him.

“Got him,” Neil whooped. “Is what all,” he asked then.

“Is that all it takes to make you happy?” Neil thought about it.

“Isn’t that enough?”

“How would I know?” Andrew finished his ice cream.

Neil’s voice was lower when he asked, “Is it true? They say your apathy is part of a mental disorder.”

“They say,” Andrew repeated. He eyed Neil’s untouched pint on the table. “Are you going to eat that? It’s melting.” Neil shook his head.

“Go ahead,” he offered. “–You never smile, you never laugh…” Neil felt a little uneasy talking about this. Of course he wanted to know but it seemed awfully private and was probably nothing Andrew wanted to share.

“Maybe you are not funny.”

“Maybe,” Neil agreed. He watched Andrew from the corners of his eyes as he opened the second pint of ice cream, and wondered how someone could eat so much sugar at once. “You…” He fended off another wave of zombies, distracted for a second. “…were different when you played for the Foxes. Because of your meds?”

“Different,” Andrew echoed again and a shadow crossed his face.

“Like… ‘fake’. –Sorry, that was… uhm. No, sorry, that was out of line,” Neil winced, his thumb rapidly hitting the buttons.

“That’s something coming from a liar,” Andrew said unfazed.

“–I guess,” Neil admitted. He finished the level and turned the game off. Turning sideways on the sofa, he faced Andrew and watched him eat. “Hey. About tonight? It wasn’t all bad, was it?” ‘This whole thing is disgusting…’ Andrew didn’t say anything, didn’t look at him. “That couldn’t have been your first blowjob. You’re too good at it,” he pressed on, trying to remind Andrew of the good parts.

“Never said it was,” Andrew answered emotionlessly. His mind clearly was on what had followed afterwards. Neil sighed. He still felt like he would lose Andrew here.

“Geez, Andrew. Do you think I never have trouble getting it up? And it’s my job.”

Andrew looked pained when he turned to Neil and asked, “Did you just compare doing this with me to getting beaten up? I feel so much better now.” Neil blinked.

“No,” he replied horrified. “That’s not what I meant. - Jesus, Andrew, and seriously, would you just stop thinking that all my clients beat me? In fact, none of them do. You miss the point in all of this.”

“And that is?”

“It’s about control. Some people like the feeling of being in control of the situation; others want to be rid of it. Some say it’s about trust, but you can’t force that. If you could, I wouldn't be there, willing to take the risk. It’s my job to pretend to trust them in that situation. –Truth be told, I don’t. I trust none of them. We hide behind rules and agreements and the risk is still there and they pay me for it. The fact that you think that I get paid to get beaten is seriously insulting.”

“You are still saying I’m one of them.”

“Aren’t you?”

“Because I hit you–“

“No! Because you pay me Andrew,” Neil said and waited for Andrew to look at him. The goalkeeper was stubbornly eating his ice cream. Because touching Andrew was not an option right now, Neil reached over and took his spoon away. The Exy player shot him an annoyed look.

“It was my fault, okay?”

“I told you, it was not,” Andrew growled.

“Yes, it was. I could repeat it right now and it would still be my fault. I triggered you–“

“Don’t call it that,” Andrew interjected, disgusted. “We are not playing your games here. This is not a scene, we don’t have safe words,” he hissed.

“Yes, we do. ‘No’, ‘Stop’, ‘Don’t’ –all of these are your safe words. You don’t have to spell it out for me. You told me in the beginning that I would need your consent every single step of the way.”

“This,” Andrew pointed between the two of them, “is just plain sex, understand? You are my hooker and I pay you for this. You said I shouldn't twist this, but it’s you who turns it into something else,” Andrew accused him angrily. Neil looked at him and said nothing. He couldn’t say anything because he had come here tonight as something Andrew didn't want him to be. It was a dead end. It felt like a slap in the face, because he had made the mistake of trying to turn this into something else tonight, something more. He had been wrong and he should have – had – known better.

He lowered his gaze and handed the spoon back to Andrew. “Sorry.” He felt ashamed all of the sudden. He knew it would turn into anger soon enough. Neil got up. “You are right. I made a mistake.” Andrew just looked at him.

This had taken a wrong turn somewhere. Andrew looked up at the man in front of him, who had suddenly lost all of his confidence. His drugged brain told him that Neil was ashamed and he couldn't figure out why in time. Damn, he was out of it. There was a reason he only did this when he was alone. One thing was certain though; Neil was going to run. Fight was no longer an option, and everything about the guy screamed flight right now. Why? He blinked.

“Sorry,” Neil said once more, then turned and left. Andrew stared after him, trying to figure it out. The spoon lay forgotten in his hand. He was still angry, but that couldn't have been it. Neil was pretty used to his moods by now. It was quite impressive actually. The guy just didn't get intimidated. Then what? His usually perfect memory wouldn't let him replay the scene in detail like he wanted. The drugs made everything foggy.

Andrew felt something snap in him and flung the spoon across the room. It clattered against the wall next to the door and then fell to the floor.

“Fuck,” he said. Andrew stood up and went to the window. He looked down, and as usual, the height as he looked straight down at the street below gave him that stomach-twisting feeling. He ignored it and kept looking. A moment later, Neil crossed the street, head lowered, hands in his pockets, feet speeding up to a jog –running away. From him, Andrew realized.

translation notes:

*’See you tomorrow night?’

‘Can’t make it tomorrow. Sorry.’ thanks for reading!

<<Chapter 8 Chapter 10>>

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hundreds of People

The quiet lodgings of Doctor Manette were in a quiet street-corner not far from Soho-square. On the afternoon of a certain fine Sunday when the waves of four months had roiled over the trial for treason, and carried it, as to the public interest and memory, far out to sea, Mr. Jarvis Lorry walked along the sunny streets from Clerkenwell where he lived, on his way to dine with the Doctor. After several relapses into business-absorption, Mr. Lorry had become the Doctor's friend, and the quiet street-corner was the sunny part of his life.

On this certain fine Sunday, Mr. Lorry walked towards Soho, early in the afternoon, for three reasons of habit. Firstly, because, on fine Sundays, he often walked out, before dinner, with the Doctor and Lucie; secondly, because, on unfavourable Sundays, he was accustomed to be with them as the family friend, talking, reading, looking out of window, and generally getting through the day; thirdly, because he happened to have his own little shrewd doubts to solve, and knew how the ways of the Doctor's household pointed to that time as a likely time for solving them.

A quainter corner than the corner where the Doctor lived, was not to be found in London. There was no way through it, and the front windows of the Doctor's lodgings commanded a pleasant little vista of street that had a congenial air of retirement on it. There were few buildings then, north of the Oxford-road, and forest-trees flourished, and wild flowers grew, and the hawthorn blossomed, in the now vanished fields. As a consequence, country airs circulated in Soho with vigorous freedom, instead of languishing into the parish like stray paupers without a settlement; and there was many a good south wall, not far off, on which the peaches ripened in their season.

The summer light struck into the corner brilliantly in the earlier part of the day; but, when the streets grew hot, the corner was in shadow, though not in shadow so remote but that you could see beyond it into a glare of brightness. It was a cool spot, staid but cheerful, a wonderful place for echoes, and a very harbour from the raging streets.

There ought to have been a tranquil bark in such an anchorage, and there was. The Doctor occupied two floors of a large stiff house, where several callings purported to be pursued by day, but whereof little was audible any day, and which was shunned by all of them at night. In a building at the back, attainable by a courtyard where a plane-tree rustled its green leaves, church-organs claimed to be made, and silver to be chased, and likewise gold to be beaten by some mysterious giant who had a golden arm starting out of the wall of the front hall - as if he had beaten himself precious, and menaced a similar conversion of all visitors. Very little of these trades, or of a lonely lodger rumoured to live up-stairs, or of a dim coach-trimming maker asserted to have a counting-house below, was ever heard or seen. Occasionally, a stray workman putting his coat on, traversed the hall, or a stranger peered about there, or a distant clink was heard across the courtyard, or a thump from the golden giant. These, however, were only the exceptions required to prove the rule that the sparrows in the plane-tree behind the house, and the echoes in the corner before it, had their own way from Sunday morning unto Saturday night.

Doctor Manette received such patients here as his old reputation, and its revival in the floating whispers of his story, brought him. His scientific knowledge, and his vigilance and skill in conducting ingenious experiments, brought him otherwise into moderate request, and he earned as much as he wanted.

These things were within Mr. Jarvis Lorry's knowledge, thoughts, and notice, when he rang the door-bell of the tranquil house in the corner, on the fine Sunday afternoon.

"Doctor Manette at home?"

Expected home.

"Miss Lucie at home?"

Expected home.

"Miss Pross at home?"

Possibly at home, but of a certainty impossible for handmaid to anticipate intentions of Miss Pross, as to admission or denial of the fact.

"As I am at home myself," said Mr. Lorry, "I'll go upstairs."

Although the Doctor's daughter had known nothing of the country of her birth, she appeared to have innately derived from it that ability to make much of little means, which is one of its most useful and most agreeable characteristics. Simple as the furniture was, it was set off by so many little adornments, of no value but for their taste and fancy, that its effect was delightful. The disposition of everything in the rooms, from the largest object to the least; the arrangement of colours, the elegant variety and contrast obtained by thrift in trifles, by delicate hands, clear eyes, and good sense; were at once so pleasant in themselves, and so expressive of their originator, that, as Mr. Lorry stood looking about him, the very chairs and tables seemed to ask him, with something of that peculiar expression which he knew so well by this time, whether he approved?

There were three rooms on a floor, and, the doors by which they communicated being put open that the air might pass freely through them all, Mr. Lorry, smilingly observant of that fanciful resemblance which he detected all around him, walked from one to another. The first was the best room, and in it were Lucie's birds, and flowers, and books, and desk, and work-table, and box of water-colours; the second was the Doctor's consulting-room, used also as the dining-room; the third, changingly speckled by the rustle of the plane-tree in the yard, was the Doctor's bedroom, and there, in a corner, stood the disused shoemaker's bench and tray of tools, much as it had stood on the fifth floor of the dismal house by the wine-shop, in the suburb of Saint Antoine in Paris.

"I wonder," said Mr. Lorry, pausing in his looking about, "that he keeps that reminder of his sufferings about him!"

"And why wonder at that?" was the abrupt inquiry that made him start.

It proceeded from Miss Pross, the wild red woman, strong of hand, whose acquaintance he had first made at the Royal George Hotel at Dover, and had since improved.

"I should have thought - " Mr. Lorry began.

"Pooh! You'd have thought!" said Miss Pross; and Mr. Lorry left off.

"How do you do?" inquired that lady then - sharply, and yet as if to express that she bore him no malice.

"I am pretty well, I thank you," answered Mr. Lorry, with meekness; "how are you?"

"Nothing to boast of," said Miss Pross.

"Indeed?"

"Ah! indeed!" said Miss Pross. "I am very much put out about my Ladybird."

"Indeed?"

"For gracious sake say something else besides `indeed,' or you'll fidget me to death," said Miss Pross: whose character (dissociated from stature) was shortness.

"Really, then?" said Mr. Lorry, as an amendment.

"Really, is bad enough," returned Miss Pross, "but better. Yes, I am very much put out."

"May I ask the cause?"

"I don't want dozens of people who are not at all worthy of Ladybird, to come here looking after her," said Miss Pross.

"DO dozens come for that purpose?"

"Hundreds," said Miss Pross.

It was characteristic of this lady (as of some other people before her time and since) that whenever her original proposition was questioned, she exaggerated it.

"Dear me!" said Mr. Lorry, as the safest remark he could think of.

"I have lived with the darling - or the darling has lived with me, and paid me for it; which she certainly should never have done, you may take your affidavit, if I could have afforded to keep either myself or her for nothing - since she was ten years old. And it's really very hard," said Miss Pross.

Not seeing with precision what was very hard, Mr. Lorry shook his head; using that important part of himself as a sort of fairy cloak that would fit anything.

"All sorts of people who are not in the least degree worthy of the pet, are always turning up," said Miss Pross. "When you began it - "

"_I_ began it, Miss Pross?"

"Didn't you? Who brought her father to life?"

"Oh! If THAT was beginning it - " said Mr. Lorry.

"It wasn't ending it, I suppose? I say, when you began it, it was hard enough; not that I have any fault to find with Doctor Manette, except that he is not worthy of such a daughter, which is no imputation on him, for it was not to be expected that anybody should be, under any circumstances. But it ready is doubly and trebly hard to have crowds and multitudes of people turning up after him (I could have forgiven him), to take Ladybird's affections away from me."

Mr. Lorry knew Miss Pross to be very jealous, but he also knew her by this time to be, beneath the service of her eccentricity, one of those unselfish creatures - found only among women - who will, for pure love and admiration, bind themselves willing slaves, to youth when they have lost it, to beauty that they never had, to accomplishments that they were never fortunate enough to gain, to bright hopes that never shone upon their own sombre lives. He knew enough of the world to know that there is nothing in it better than the faithful service of the heart; so rendered and so free from any mercenary taint, he had such an exalted respect for it, that in the retributive arrangements made by his own mind - we all make such arrangements, more or less-he stationed Miss Pross much nearer to the lower Angels than many ladies immeasurably better got up both by Nature and Art, who had balances at Tellson's.

"There never was, nor will be, but one man worthy of Ladybird," said Miss Pross; "and that was my brother Solomon, if he hadn't made a mistake in life."

Here again: Mr. Lorry's inquiries into Miss Pross's personal history had established the fact that her brother Solomon was a heartless scoundrel who had stripped her of everything she possessed, as a stake to speculate with, and had abandoned her in her poverty for evermore, with no touch of compunction. Miss Pross's fidelity of belief in Solomon (deducting a mere trifle for this slight mistake) was quite a serious matter with Mr. Lorry, and had its weight in his good opinion of her.

"As we happen to be alone for the moment, and are both people of business," he said, when they had got back to the drawing-room and had sat down there in friendly relations, "let me ask you - does the Doctor, in talking with Lucie, never refer to the shoemaking time, yet?"

"Never."

"And yet keeps that bench and those tools beside him?"

"Ah!" returned Miss Pross, shaking her head. "But I don't say he don't refer to it within himself."

"Do you believe that he thinks of it much?"

"I do," said Miss Pross.

"Do you imagine - " Mr. Lorry had begun, when Miss Pross took him up short with:

"Never imagine anything. Have no imagination at all."

"I stand corrected; do you suppose - you go so far as to suppose, sometimes?"

"Now and then," said Miss Pross.

"Do you suppose," Mr. Lorry went on, with a laughing twinkle in his bright eye, as it looked kindly at her, "that Doctor Manette has any theory of his own, preserved through all those years, relative to the cause of his being so oppressed; perhaps, even to the name of his oppressor?"

"I don't suppose anything about it but what Ladybird tells me."

"And that is - ?"

"That she thinks he has."

"Now don't be angry at my asking all these questions; because I am a mere dull man of business, and you are a woman of business."

"Dull?" Miss Pross inquired, with placidity.

Rather wishing his modest adjective away, Mr. Lorry replied, "No, no, no. Surely not. To return to business: - Is it not remarkable that Doctor Manette, unquestionably innocent of any crane as we are all well assured he is, should never touch upon that question? I will not say with me, though he had business relations with me many years ago, and we are now intimate; I will say with the fair daughter to whom he is so devotedly attached, and who is so devotedly attached to him? Believe me, Miss Pross, I don't approach the topic with you, out of curiosity, but out of zealous interest."

"Well! To the best of my understanding, and bad's the best, you'll tell me," said Miss Pross, softened by the tone of the apology, "he is afraid of the whole subject."

"Afraid?"

"It's plain enough, I should think, why he may be. It's a dreadful remembrance. Besides that, his loss of himself grew out of it. Not knowing how he lost himself, or how he recovered himself, he may never feel certain of not losing himself again. That alone wouldn't make the subject pleasant, I should think."

It was a profounder remark than Mr. Lorry had looked for. "True," said he, "and fearful to reflect upon. Yet, a doubt lurks in my mind, Miss Pross, whether it is good for Doctor Manette to have that suppression always shut up within him. Indeed, it is this doubt and the uneasiness it sometimes causes me that has led me to our present confidence."

"Can't be helped," said Miss Pross, shaking her head. "Touch that string, and he instantly changes for the worse. Better leave it alone. In short, must leave it alone, like or no like. Sometimes, he gets up in the dead of the night, and will be heard, by us overhead there, walking up and down, walking up and down, in his room. Ladybird has learnt to know then that his mind is walking up and down, walking up and down, in his old prison. She hurries to him, and they go on together, walking up and down, walking up and down, until he is composed. But he never says a word of the true reason of his restlessness, to her, and she finds it best not to hint at it to him. In silence they go walking up and down together, walking up and down together, till her love and company have brought him to himself."

Notwithstanding Miss Pross's denial of her own imagination, there was a perception of the pain of being monotonously haunted by one sad idea, in her repetition of the phrase, walking up and down, which testified to her possessing such a thing.

The corner has been mentioned as a wonderful corner for echoes; it had begun to echo so resoundingly to the tread of coming feet, that it seemed as though the very mention of that weary pacing to and fro had set it going.

"Here they are!" said Miss Pross, rising to break up the conference; "and now we shall have hundreds of people pretty soon!"

It was such a curious corner in its acoustical properties, such a peculiar Ear of a place, that as Mr. Lorry stood at the open window, looking for the father and daughter whose steps he heard, he fancied they would never approach. Not only would the echoes die away, as though the steps had gone; but, echoes of other steps that never came would be heard in their stead, and would die away for good when they seemed close at hand. However, father and daughter did at last appear, and Miss Pross was ready at the street door to receive them.

Miss Pross was a pleasant sight, albeit wild, and red, and grim, taking off her darling's bonnet when she came up-stairs, and touching it up with the ends of her handkerchief, and blowing the dust off it, and folding her mantle ready for laying by, and smoothing her rich hair with as much pride as she could possibly have taken in her own hair if she had been the vainest and handsomest of women. Her darling was a pleasant sight too, embracing her and thanking her, and protesting against her taking so much trouble for her - which last she only dared to do playfully, or Miss Pross, sorely hurt, would have retired to her own chamber and cried. The Doctor was a pleasant sight too, looking on at them, and telling Miss Pross how she spoilt Lucie, in accents and with eyes that had as much spoiling in them as Miss Pross had, and would have had more if it were possible. Mr. Lorry was a pleasant sight too, beaming at all this in his little wig, and thanking his bachelor stars for having lighted him in his declining years to a Home. But, no Hundreds of people came to see the sights, and Mr. Lorry looked in vain for the fulfilment of Miss Pross's prediction.

Dinner-time, and still no Hundreds of people. In the arrangements of the little household, Miss Pross took charge of the lower regions, and always acquitted herself marvellously. Her dinners, of a very modest quality, were so well cooked and so well served, and so neat in their contrivances, half English and half French, that nothing could be better. Miss Pross's friendship being of the thoroughly practical kind, she had ravaged Soho and the adjacent provinces, in search of impoverished French, who, tempted by shillings and halfcrowns, would impart culinary mysteries to her. From these decayed sons and daughters of Gaul, she had acquired such wonderful arts, that the woman and girl who formed the staff of domestics regarded her as quite a Sorceress, or Cinderella's Godmother: who would send out for a fowl, a rabbit, a vegetable or two from the garden, and change them into anything she pleased.

On Sundays, Miss Pross dined at the Doctor's table, but on other days persisted in taking her meals at unknown periods, either in the lower regions, or in her own room on the second floor - a blue chamber, to which no one but her Ladybird ever gained admittance. On this occasion, Miss Pross, responding to Ladybird's pleasant face and pleasant efforts to please her, unbent exceedingly; so the dinner was very pleasant, too.

It was an oppressive day, and, after dinner, Lucie proposed that the wine should be carried out under the plane-tree, and they should sit there in the air. As everything turned upon her, and revolved about her, they went out under the plane-tree, and she carried the wine down for the special benefit of Mr. Lorry. She had installed herself, some time before, as Mr. Lorry's cup-bearer; and while they sat under the plane-tree, talking, she kept his glass replenished. Mysterious backs and ends of houses peeped at them as they talked, and the plane-tree whispered to them in its own way above their heads.

Still, the Hundreds of people did not present themselves. Mr. Darnay presented himself while they were sitting under the plane-tree, but he was only One.

Doctor Manette received him kindly, and so did Lucie. But, Miss Pross suddenly became afflicted with a twitching in the head and body, and retired into the house. She was not unfrequently the victim of this disorder, and she called it, in familiar conversation, "a fit of the jerks."

The Doctor was in his best condition, and looked specially young. The resemblance between him and Lucie was very strong at such times, and as they sat side by side, she leaning on his shoulder, and he resting his arm on the back of her chair, it was very agreeable to trace the likeness.

He had been talking all day, on many subjects, and with unusual vivacity. "Pray, Doctor Manette," said Mr. Darnay, as they sat under the plane-tree - and he said it in the natural pursuit of the topic in hand, which happened to be the old buildings of London - "have you seen much of the Tower?"

"Lucie and I have been there; but only casually. We have seen enough of it, to know that it teems with interest; little more."

"_I_ have been there, as you remember," said Darnay, with a smile, though reddening a little angrily, "in another character, and not in a character that gives facilities for seeing much of it. They told me a curious thing when I was there."

"What was that?" Lucie asked.

"In making some alterations, the workmen came upon an old dungeon, which had been, for many years, built up and forgotten. Every stone of its inner wall was covered by inscriptions which had been carved by prisoners - dates, names, complaints, and prayers. Upon a corner stone in an angle of the wall, one prisoner, who seemed to have gone to execution, had cut as his last work, three letters. They were done with some very poor instrument, and hurriedly, with an unsteady hand. At first, they were read as D. I. C.; but, on being more carefully examined, the last letter was found to be G. There was no record or legend of any prisoner with those initials, and many fruitless guesses were made what the name could have been. At length, it was suggested that the letters were not initials, but the complete word, DiG. The floor was examined very carefully under the inscription, and, in the earth beneath a stone, or tile, or some fragment of paving, were found the ashes of a paper, mingled with the ashes of a small leathern case or bag. What the unknown prisoner had written will never be read, but he had written something, and hidden it away to keep it from the gaoler."

"My father," exclaimed Lucie, "you are ill!"

He had suddenly started up, with his hand to his head. His manner and his look quite terrified them all.

"No, my dear, not ill. There are large drops of rain falling, and they made me start. We had better go in."

He recovered himself almost instantly. Rain was really falling in large drops, and he showed the back of his hand with rain-drops on it. But, he said not a single word in reference to the discovery that had been told of, and, as they went into the house, the business eye of Mr. Lorry either detected, or fancied it detected, on his face, as it turned towards Charles Darnay, the same singular look that had been upon it when it turned towards him in the passages of the Court House.

He recovered himself so quickly, however, that Mr. Lorry had doubts of his business eye. The arm of the golden giant in the hall was not more steady than he was, when he stopped under it to remark to them that he was not yet proof against slight surprises (if he ever would be), and that the rain had startled him.

Tea-time, and Miss Pross making tea, with another fit of the jerks upon her, and yet no Hundreds of people. Mr. Carton had lounged in, but he made only Two.

The night was so very sultry, that although they sat with doors and windows open, they were overpowered by heat. When the tea-table was done with, they all moved to one of the windows, and looked out into the heavy twilight. Lucie sat by her father; Darnay sat beside her; Carton leaned against a window. The curtains were long and white, and some of the thunder-gusts that whirled into the corner, caught them up to the ceiling, and waved them like spectral wings.

"The rain-drops are still falling, large, heavy, and few," said Doctor Manette. "It comes slowly."

"It comes surely," said Carton.

They spoke low, as people watching and waiting mostly do; as people in a dark room, watching and waiting for Lightning, always do.

There was a great hurry in the streets of people speeding away to get shelter before the storm broke; the wonderful corner for echoes resounded with the echoes of footsteps coming and going, yet not a footstep was there.

"A multitude of people, and yet a solitude!" said Darnay, when they had listened for a while.

"Is it not impressive, Mr. Darnay?" asked Lucie. "Sometimes, I have sat here of an evening, until I have fancied - but even the shade of a foolish fancy makes me shudder to-night, when all is so black and solemn - "

"Let us shudder too. We may know what it is."

"It will seem nothing to you. Such whims are only impressive as we originate them, I think; they are not to be communicated. I have sometimes sat alone here of an evening, listening, until I have made the echoes out to be the echoes of all the footsteps that are coming by-and-bye into our lives."

"There is a great crowd coming one day into our lives, if that be so," Sydney Carton struck in, in his moody way.

The footsteps were incessant, and the hurry of them became more and more rapid. The corner echoed and re-echoed with the tread of feet; some, as it seemed, under the windows; some, as it seemed, in the room; some coming, some going, some breaking off, some stopping altogether; all in the distant streets, and not one within sight.

"Are all these footsteps destined to come to all of us, Miss Manette, or are we to divide them among us?"

"I don't know, Mr. Darnay; I told you it was a foolish fancy, but you asked for it. When I have yielded myself to it, I have been alone, and then I have imagined them the footsteps of the people who are to come into my life, and my father's."

"I take them into mine!" said Carton. "_I_ ask no questions and make no stipulations. There is a great crowd bearing down upon us, Miss Manette, and I see them - by the Lightning." He added the last words, after there had been a vivid flash which had shown him lounging in the window.

"And I hear them!" he added again, after a peal of thunder. "Here they come, fast, fierce, and furious!"

It was the rush and roar of rain that he typified, and it stopped him, for no voice could be heard in it. A memorable storm of thunder and lightning broke with that sweep of water, and there was not a moment's interval in crash, and fire, and rain, until after the moon rose at midnight.

The great bell of Saint Paul's was striking one in the cleared air, when Mr. Lorry, escorted by Jerry, high-booted and bearing a lantern, set forth on his return-passage to Clerkenwell. There were solitary patches of road on the way between Soho and Clerkenwell, and Mr. Lorry, mindful of foot-pads, always retained Jerry for this service: though it was usually performed a good two hours earlier.

"What a night it has been! Almost a night, Jerry," said Mr. Lorry, "to bring the dead out of their graves."

"I never see the night myself, master - nor yet I don't expect to-what would do that," answered Jerry.

"Good night, Mr. Carton," said the man of business. "Good night, Mr. Darnay. Shall we ever see such a night again, together!"

Perhaps. Perhaps, see the great crowd of people with its rush and roar, bearing down upon them, too.

0 notes