#with some guitars that whole section would sound like your more standard sonic music

Text

Sonic Frontiers

Kronos Island: 6th Mvt.

#sonic the hedgehog#sonic music#sonic the hedgehog music#sonic frontiers#music of the day#ohh now we're serious#you can only barely recognize the older melody#the buildup until 2 minutes is long but worth it for those violins#with some guitars that whole section would sound like your more standard sonic music

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

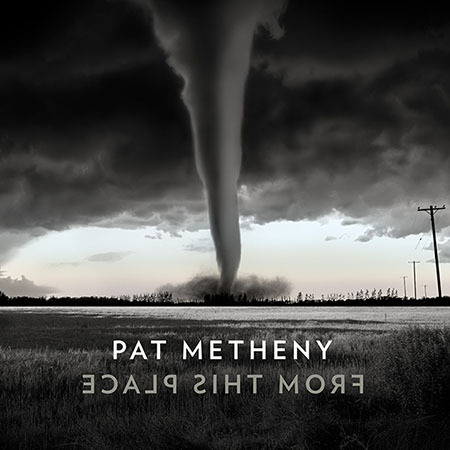

A deeper look at: Pat Metheny: From This Place (Nonesuch/Metheny Group Productions, 2020)

Pat Metheny: guitars, keyboards; Gwilym Simcock: piano; Linda May Han Oh: bass; voice, Antonio Sanchez: drums with the Hollywood Studio Symphony conducted by Joel McNeely. Special guests: Luis Conte: percussion; Gregoire Maret: harmonica; Meshell Ndegeocello: vocals.

This review is dedicated to the memory Lyle Mays (1953-2020). Your brilliance, and contribution to Metheny’s music, and the world of music as a whole will never be forgotten.

Pat Metheny enters a new phase of his career and era with From This Place. The guitarist has been regularly performing for the past several years be it with the stellar quartet that graces this release, Welsh pianist Gwilym Simcock, Malaysian-Australian bassist Linda May Han Oh and drummer of choice, Antonio Sanchez, in addition to duos with bass legend Ron Carter, and the experimental Side Eye project prominently featuring acclaimed up and coming young musicians. However, From This Place is the guitarist's first recording in six years since Kin (↔) with the Pat Metheny Unity Group. To round out the core group, Metheny enlisted Metheny Group alumni Luis Conte on percussion, in addition to harmonica ace Gregoire Maret who played on and toured behind The Way Up. The guitarist also welcomes back arranger Gil Goldstein to the fold who appeared on Secret Story as well as the tour that followed, and the legendary Alan Broadbent. Meshell Ndegeocello sings on the title track with lyrics written by her partner Alison Riley.

Metheny has been no stranger to touring and constant playing, although the 66 year old has scaled back his once massive nearly year round touring schedule to about 150-200 dates around the world to accommodate family life, the fact that From This Place is the first album in six years is a bit of anomaly in his release history. The music industry has rapidly changed in recent years: the rise of streaming sites like Spotify, Amazon HD Music, and Qobuz in addition to Youtube has changed the way the public consumes music. CD sales have rapidly declined, although they still outsell vinyl, which is continuing it’s resurgence. Metheny has been an example of an artist where physical releases are truly special, almost an event. Going back to his days on ECM, he has always benefited from striking cover art, often being involved directly in the process itself, something rare nowadays. He has adopted not only streaming, but usage of Bandcamp and offers up audiophile high resolution mastering of the new recording on platforms like HD Tracks and Pro Studio Masters, though the advent of Youtube almost a decade ago and frequent camera phone videos (as well as bootlegs in general) have been an impediment to the guitarist and thus resulted in the controlled studio environments that spawned The Orchestrion Project and Unity Sessions video and album releases reflective of how he approached the music live on tour.

The guitarist has also in the past decade drastically changed his approach to music. While his recordings with the Pat Metheny Group featuring co founder, keyboardist and writing partner, the late Lyle Mays were and continue to be his most popular works balancing complex forms with memorable melodies. Since the PMG's final recording The Way Up in 2005, the guitarist has focused on increasingly complex, harmonically dense music that has entered new arenas. This music, featured on albums like Orchestrion, Tap (where he played the music of John Zorn) and Kin(<->) while bearing his inimitable melodic stamp, if one were to peruse various internet discussions, some fans felt that these albums had a higher barrier of entry and wished for more melodic material-- while all these albums, plus Unity Band featured exemplary writing, occasionally the melodies took their time to unfold. While many of these melodies contained Metheny’s unmistakable essence, From This Place for the most part, goes back to where his melodies are instantly memorable and singable. Because the album features backing from the Hollywood studio symphony, in addition to the core quartet, some listeners may automatically assume it is a direct sequel to Secret Story, the album is anything but. Though it at times conjures moods of the earlier album, the similarities end beyond surface comparisons. The fact is Metheny has moved far beyond that period in his writing, and improvisational abilities, and his writing is the best it's ever been. The album is somewhat of a career summation, but like many others in his discography like Speaking Of Now, or Imaginary Day, the contents also show a new path forward. This album is firmly rooted in the interplay and solos of a quartet, as Unity Band was, though the the backing of the orchestra, with arrangements centered on what the quartet played, change the complexion considerably. It is also the first time the guitarist has had a pianist for a foil in his own bands since Lyle Mays.

The genesis for how this music came to be is fascinating. Around December of 2017, Metheny went into the studio with Simcock, May Han Oh and Sanchez, and laid down sixteen new compositions, of which ten are on this release. As the music began to be played, he began to hear things inside of it that had yet to be manifested. The guitarist had logged considerable road time with bassist Ron Carter, whom he played several duo gigs. During the travel time, Metheny asked Mr. Carter, a lifelong hero of his about the process of playing in the Miles Davis Quintet from 1963-1968-- more specifically, why did they stick to Davis' standard book in concert? The bassist has frequently described the nightly experiences of playing with Davis as being a laboratory, and they developed a certain code on the bandstand, where through playing standards, they were able to use said code in the creation of new music in the studio.

From that inspiration, Metheny toured the quartet on the road playing selections from his vast songbook. They too, would use their own code, something not entirely unfamiliar. After all, the first recording that Antonio Sanchez participated in was Speaking of Now (2002) with the Pat Metheny Group, and that album, like From This Place was an evolutionary album, which set the stage for the larger territory tackled in The Way Up. The seeds sown in the compositional processes found there would be in Orchestrion and Kin (↔). The present quartet has really inspired him, and arguably is closest in conception and flavor to the original PMG in terms of broad stylistic conception. Longtime Metheny fans who have been at shows in that period, or in collector's circles are quite familiar that the early PMG experimented with new tunes before recording, including standards into the set list as well as playing fan favorite tracks. Something quite similar to the current quartet. As Metheny explained vis a vis the approach to add orchestration to flesh out the playing of the quartet he notes:

As much as folks might describe the sonic language of the avant-garde movement of the sixties as falling into an identifiable generic sound, I have always regarded the general expansion of creativity of that era in a more ecumenical way.

The stylistic changes that occurred then in our community included not only the obvious examples of individual players utilizing extended techniques on their instruments in new ways, or new types of ensembles, but also the wildly new approaches that technology, particular recording technology, offered.

Multi-track recording allowed for entirely new kinds of music to be made.

It is unlikely that the recordings of the CTI label of that time would likely never be thought of as “avant-garde” by garden variety jazz critics of that (or probably any other) era. But from my seat as a young fan, the idea of an excellent and experienced arranger like Don Sebesky taking the improvised material of great musicians like Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter and weaving their lines and voicings into subsequent orchestration was not only a new kind of arranging; it resulted in a different kind of sound and music.

It was a way of presenting music that represented the impulses of the players and the improvisers at hand through orchestration in an entirely new way. I loved those records.

This will not be the first recording of mine where that equation—record first, orchestrate later—has come up. But it is by far the most extensive one, and I would offer the most organic. From the first notes we recorded, this was the destination I had in mind.

Don Sebesky's arranging skills, found on recordings such as First Light (1971) by Freddie Hubbard, Sunflower (1972) by Milt Jackson and his own Giant Box (1974) illustrate the approach Metheny had in mind. The track “Wide and Far” is not the first Metheny track to feature an overt homage to the CTI sound. “So May It Secretly Begin” from the classic (Still Life) Talking (1987) was also an Sebesky homage, particularly in the rich Synclavier string arrangement, but “Wide and Far” positioned as the second cut on From This Place takes that arranging influence to a far deeper level. The melody is simply prime Metheny, with string, reed and brass sections that in some ways are reminiscent of Freddie Hubbard's Sky Dive (1972) album. The guitarist, spurred by Sanchez's liquid ride and May Han Oh's of the earth bass takes an inspired solo, amidst soaring orchestral harmonies. There is a deep in the cut funkiness aspect of Metheny's playing here that not only exhibits the sheer joy of playing with this special class of musicians, but his nods to George Benson here appear more overt than they did on “Here To Stay” from the Metheny Group's We Live Here (1995). It is a beautiful homage, and the handoff to Gwilym Simcock on the bridge section is seamless, where the pianist weaves, fresh lines in his very individual voice. The Welsh pianist was a late bloomer to the jazz world, as he began playing the music in his twenties. Over the course of two decades with associations such as former reedist with Chick Corea's Origin, Tim Garland and the Steve Rodby produced Impossible Gentlemen, Simcock has been one of the most in demand pianists. During the quartet's 2017 performance at the Beacon Theater it was amply evident how much the guitarist enjoyed having a pianist against as co conspirator and solo voice. The quality is evident in spades on From This Place and one wonders the possibilities were Metheny and Simcock to become co writers. Also in the Davis Quintet mold, Metheny had each member have input on the material and three of the four members arrange pieces, save Sanchez who acts as an arranger in real time crafting colors and textures based on what the music calls for. While the recording has several trademark cinematic numbers, perhaps none so than “America Undefined” a defiant statement against the election of Donald Trump as U.S. President. The piece draws on the more complex material found on Orchestrion and Kin (↔). Linda May Han Oh, a wonderful leader and composer in her own right, most recently used strings in provocative ways on her latest work Aventurine, and brings that deep orchestral awareness and attention to shading found in her own work to From This Place.

A Sanchez cymbal roll leads into May Han Oh's ascending arco bass melody, which bears some similarity and extends on a bit, the post solo interlude section of the Kin (↔) title track featuring Giulio Carmassi's ascending vocals in tandem with guitar in piano. May Han Oh's arco melody sets a prominent melodic thread through the piece, and Metheny adds signature hollow body guitar over a rubato foundation that gives way to him once again stating the melody with orchestra behind him in a 5/8 time signature. During the melodic statement, Simcock and May Han Oh play a stunning unison counterpoint line, reminiscent of Bach. Simcock's piano solo begins with the rubato foundation, Sanchez adding provocative rim clicks and fascinating comping underneath. From there, Simcock is vaulted into a burning 4/4 swing and samba section sans bass drum accents, the orchestra reminding listeners of the melodic cel behind them. Simcock's solo is filled with vigorous single note ideas, he is a devotee of Metheny's entire catalog, also bearing out why he is an evolution in Metheny's concept of a pianistic foil—something the guitarist clearly relishes. Metheny follows with a soaring, inspired hollow body solo, the orchestra's harmonies providing a huge lift.

May Han Oh returns with the initial melodic figure at the top, and then around 8 minutes into the piece, what sounds like Orchestrion vibes introduce a much darker, brooding mode. Shades of the sound effect and musique concrete driven sections of “As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls” are here, with some of the strangeness of the soundscape section of “Are We There Yet?” from Letter From Home in terms of eerie sounds wafting in and out of the mix. The sounds of clunking, and railroad tracks dominate as the strings remind of the melody once again, May Han Oh's thunking pedal point from earlier in the composition is yet another thematic thread. Metheny uses slide and ebow guitar as a constant distant drone, and provides disembodied strands of further distanced electric guitar in the sound stage bouncing between speakers (or headphones). At first listen it seems to be a call back to “Cathedral in a Suitcase” from Secret Story (1992), but upon further listens is more reminiscent of the distorted guitar deeply embedded into the mix at the start of “Psalm 121” on the soundtrack of The Falcon And The Snowman (1985). The bluesiness of these disembodied lines somehow evokes uncertainty, and the loud bells of a railroad sign, as the orchestra spins variations on the main theme, let you know something is coming. Suddenly, Sanchez' slightly gated drums, a not so subtle Phil Collins and 80's production reference, and reminder of Steve Ferrone's toms on “Cathedral in a Suitcase” thunder in, to the sound of a loud train whistle, panning through the speakers. Sanchez's driving, John Bonham inspired rock beat along with the symphonies' restatement of a portion of the melody makes things truly epic. The five minutes of orchestral investigation is truly thrilling and shows how deep of a writer Metheny has become. Indian flavored strings play portamento glissando with microtonal elements, like those used on “Within You, Without You” from The Beatles are an unexpected but pleasant element in a breathtaking finale. The piece dies down with the fluttering of castanets, like birds flying away in a flock, eerie sampled vocal sounds in the left channel, fluttering and processed abrupt flutes and strings. It's an unexpected end to a piece using some variant of a sonata form but never resolves itself completely. Make no mistake about it, the piece is foreboding and dark, tapping into a new area of Metheny's writing, but strangely, there is also a trace of hope.

“You Are” is one of the most striking offerings on the recording. Since Bright Size Life (ECM, 1975) on every album, the guitarist has had a melodic idea that his pushes to the breaking point through motivic development. Simcock's piano quietly begins the track doubled by chiming orchestra bells, a tip toeing two note figure is stated in unison, with sparse brushed cymbal work from Sanchez. Metheny's dark hollow body tone announces the melody, as the two note figure is enhanced by a wall of synthesizers, and strings. May Han Oh's soprano voice is added to the density as she and Metheny state an arresting three note idea that builds and builds to a dramatic climax, before gentle strings sing in hushed tones as the original two note motif returns to close the piece.

Flutes double May Han Oh's resonate bass for the gentle melancholic theme of “Same River”. The acoustic sitar guitar makes it's first appearance since “Wherever You Go” from Speaking of Now, and Metheny's double tracked guitar and sitar make use of one of his favorite devices, the glissando. Simcock plays a tasteful brief piano solo before the guitarist takes a trademark flight on Roland GR300 guitar synth, gorgeous ascending french horn and string harmonies-- the CTI reference is indeed very clear in this track with strong doses that will recall listeners of the PMG at their peak and some flavors of Secret Story (1992).

“Pathmaker” represents some of Metheny's most adventurous writing on record. The track, along with “Everything Explained” bear a strong Chick Corea influence. Metheny is positively lyrical on his first solo, then Simcock is at once melodic and knotty. One of the most exquisite aspects of the track is the unison line between Metheny and Simcock following the second guitar solo as Sanchez frames a volcanic dialogue around their line. The provocative dreamy coda, sounding something out of a French film score, utilizes choice coloration from bass clarinet amidst butterfly esque clarinet string trills and some electronics popping in and out. Atop all that, Metheny's heavily reverbed slide guitar offers a longing melodic aside as the composition finishes. PMG alum and frequent Phil Collins percussionist Luis Conte's omnipresent colorations are a tremendous asset to the track.

If anything will make listeners make direct comparisons to Secret Story it will be the track “The Past In Us”. PMG alumni Gregoire Maret's reflective harmonica solo may remind some of the late Toots Thielemans' unforgettable eight bar contribution to “Always and Forever”, with the swelling strings behind him. Metheny graces the track with an absolutely gorgeous nylon string guitar solo. The final tracks are also perfectly programmed. The title track stands as one of the guitarist's prettiest ballads, gorgeous strands of Bach inspired baroque strings frame a long intro, from which hymn like harmonies emerge. Ndegeocello's rich voice in alto and soprano ranges paints a picture of despair and hopelessness with tender lyrics related to the current cultural climate-- yet like much of Metheny's music over the years stands a bright ray of hope. He takes an exquisite nylon string solo here as well.

“Sixty-Six” is a beautiful reminder of the midwestern tinges returning to the fore in Metheny's music. The train motif is once again stated, with Sanchez' brushes on snare, and the guitarist spins a wonderful, singable melody over the top, and mixes the lyrical with the more harmonically rich approach to improvisation that has marked his work over the past decade. Linda Oh's initial solo is full of ripe ideas, and her double tracked bass interlude following the guitarist's solo is an affectionate wink to Eberhard Weber. To close the album, the Sebesky arranged CTI vibe returns on “Love May Take A While”, a wonderful ballad that if one closes their eyes, one can almost imagine Metheny's nuanced hollow body solo to be a horn, in his assurance of ideas.

Sound

From This Place was principally recorded and mixed by Pete Karam at Avatar Studios (now Power Station, Berklee) with the orchestral parts recorded by Rich Breen in Los Angeles. Karam has inherited the very rich sonic world found on Metheny recordings that was originally created and perfected from the Geffen era on by Rob Eaton. Metheny's guitars take front and center in the sound stage with the delay from his multiple amp set up panning between the left and right speakers-- the effect is not as pronounced as say Travels, Question and Answer or Letter From Home, but is still there and has evolved as Metheny's tone has changed through the first two decades of the 21st century. Linda May Han Oh's basslines appropriately showcase the deep woodiness of an acoustic bass sound and is quite accurate to the real thing. Antonio Sanchez' drums are very present and forward in the mix with the main ride cymbal in the left channel, and his multiple snare drums being placed across the sound stage.

Luis Conte's percussion is also quite forward in the mix, and Simcock's piano is rich. Orchestra placement is subtle to the rear of the soundstage. What is apparent though is unlike earlier Metheny albums, the mix, like Kin (↔) the previous studio album is heavier on the mids, with not as much treble sparkle up top though this may be clearly system dependent. Also interesting, while the album will be released in high res, the promo copies that were distributed by Nonesuch are 16 bit WAV files with a 48 KhZ sample rate equivalent to DVD quality, so while not hi res, the quality is a step from CD quality. Thankfully Ted Jensen's mastering maintains a strong sense of dynamics which is imperative for music of this scope.

Final thoughts:

In what has been a career spanning nearly a half century, and filled with gems and milestones from both solo work and the Pat Metheny Group combined, From This Place may very well be one of the best albums of Metheny's career, if not the best. His writing is clearly on another level, and as great as recordings with orchestra accompaniment have been like The Falcon and The Snowman, Secret Story and A Map of The World have been, the combination of one of his best ensembles in years, the inspired memorable tunes, great solos and the high level of arranging prowess, represent the guitarist at his best. The music is as much a summary of what has been to this point as it is pointing some new directions into the future. Those who take the time to listen, understand the music for what it is, rather than what it should be, or is not, will be greatly rewarded.

Music: 10/10

Sound: 9/10

Edit: I made an addendum to the date of the recording which I previously stated as December 2016. After the NYC Beacon Theater show in June 2017, Antonio Sanchez told me they were going into the studio to record, that December.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom Ending Explained

https://ift.tt/3pc88gJ

This Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom analysis contains spoilers. You can find our spoiler-free review here.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom tells the story of a group of 1920s musicians, composites of session players at the time, waiting for “the Mother of the Blues” to bring her big voice to the big room at Hot Rhythm Recordings. “Ma” Rainey, positively channeled by Viola Davis in the film, owned the copyrights of her songs, some of which became blues standards. Her trumpet player, Levee, masterfully captured by Chadwick Boseman in his cinematic swan song, doesn’t catch that break. The young horn player spends a lot of his time finishing a song for the session producer Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne). He’s promised a recording using his arrangement.

The delivery of that promise first comes as a devaluation. The producer pounces on Levee when he’s down. He’d just been fired by the First Lady of Blues herself, and Sturdyvant tells him the song’s not what he’s looking for, but he can give him five bucks for his troubles. As a matter of fact, he can dump all his troubles, and songs, on the table at Hot Rhythm Recordings for five dollars a pop.

That’s low, but Sturdyvant sinks deeper into the bait and switch. Not only does he offer Levee a pittance for brilliance, but he commits the ultimate musical sin: He sucks the soul out of it, just as plainly as the man at the Crossroads got Eliza Cotter’s soul in a story we heard in the practice room. Hot Rhythm Recordings whitewashed that song, turning it into a standard for white musicians to play. That’s worse than stepping on a man’s shoes, and people get knifed for that.

Did it happen? Yes, and probably with the same exact words used on the fictional Levee. It happened all the time, and worse. Cultural appropriation didn’t start with Iggy Azalea; it predates Led Zeppelin stealing Willie Dixon’s “You Need Love” for “Whole Lotta Love;” it was there before The Beatles apparently nicked the guitar lick from “Watch Your Step” by Bobby Parker for the riff on “I Feel Fine;” Chuck Berry had to sue to get credit for the Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ USA,” an almost note-for-note copy of “Sweet Little Sixteen.” His name is on the song now. He might even have bought a swimming pool with the royalties.

Many of the songs of the Carter Family, country music pioneers during the 1930s, were written or collected by A.P. Carter’s side man, Black guitarist Lesley Riddle, who may have been paid, but didn’t get any copyrights.

One of the most known cases of devaluing the artist happened during the recording of the song “Hound Dog.” “Big Mama” Thornton only made $500 for recording the session, even though songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller penned it for her voice, and even though she originated the yells and screams which punctuated and expanded on the original tune’s structure. After the song went on to be a landmark of rock music, particularly due to Elvis Presley’s cover, $500 doesn’t seem like much.

“Hound Dog” is as influential and recognizable as Ma Rainey’s “See See Rider,” recorded at the dawn of the blues. The practice is still happening today. Strictly speaking, this article is cultural appropriation. It’s been rampant since the first kidnapped Africans arrived in chains on these shores.

The theft of Black intellectual property permeates the entire history of American culture. In the performing arts, the most flagrant example is often overlooked because it happened to coincide with the creation of blackface. But Thomas Dartmouth Rice didn’t just burn cork to darken his face when he became a minstrel singer and invented “Jim Crow” in 1832; he also never credited the older Black man he heard singing and claimed to steal the rhythm and tenor of. Frederick Douglass called blackface minstrels “the filthy scum of white society.”

White European music was all linear until the influence of African sonics. African American artists infused classical orchestral instruments with gospel harmonies, added hand claps to the rhythm sections, and the noise of natural life. Black music was syncopated, filled with call and response, and unafraid to include the distortion of performance to play a part in musical composition. Improvisation isn’t limited to notes which can be transcribed on a page; it is the squawk of a clarinet or saxophone, a growl in a voice, or the flutter of lips on a trumpet.

At the turn of the 20th century, “race” music was underground, and seen as sleazy and somehow sinful. But as Black slang, music, and dances became popular among rebellious young whites in the 1920s, the institutions followed. Between the 1920s and ‘40s, blues, jazz, and gospel recordings by Black artists got very little airplay on large radio stations. During the Depression, radio stations hired white artists to cover black songs on air. Black musicians were routinely underpaid by record companies for songs given to white musicians.

“America is caught up in this conversation about the past,” Ma Raney director George C. Wolfe tells Den of Geek. “How much are we going to own up to the past and how much has that past informing the present? … And so Levee is, more than any other character in the film, emblematic of the future. He is America; he is this talent, this promise of what could be, but he is haunted and damaged by the scars of the past.”

Ma Rainey was signed to Paramount Records, which the film depicts as Hot Rhythm Recordings, by Mayo “Ink” Williams. He earned his nickname because he was very good at getting African American musicians to sign recording contracts.

Williams was the first Black producer at a major record label. He was also one of the first African Americans to play pro football, and is the only person to be inducted into both the Blues Hall of Fame Blues and the National Football Hall of Fame. But even Williams was guilty of shortchanging artists. He used some of the same excuses as the producer in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom too. He’d tried running his own independent label, and supplemented his own salary at Paramount by padding his take when negotiating writing credits.

Read more

Culture

Ma Rainey’s Life and Reign as the Mother of the Blues

By Tony Sokol

Movies

The Journey Of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom From Stage To Screen

By Don Kaye

Williams probably saw this as how it fit into the overall score of things. He would go on to write or produce songs which ushered in rock and roll. He went to work for Decca Records in 1934 and worked with artists like Mahalia Jackson, Sleepy John Estes, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and Louis Jordan. When Williams left Decca in 1946, he founded the Chicago, Southern, and Ebony record labels, and worked with artists like Muddy Waters.

The very first Black-owned and operated record company was Broome Special Phonograph Records, founded by George W. Broome in 1919. The label only put out 12 sides, and didn’t last very long. The Pace Phonograph Company was founded in December 1920 by Harry Herbert Pace, who collaborated on songs with W.C. Handy, and formed the Pace & Handy Music Company with him in Memphis in 1912. Handy’s 1914 song, “St. Louis Blues,” was the label’s first hit.

The company moved to New York and changed their name to Black Swan records. When the label did well, their publicity department was sure to let everyone know “every time you buy a Black Swan record, you buy the only record made by colored people.”

The record company was bought out in January 1924, by M.A. Supper, putting the race-record business in the hands of white-owned record companies. Supper changed the label’s name to Paramount Records.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom ends with a cheerful version of “Baby, Let Me Have It All,” sung by Clint Johnson. It is an adequate rendition, middle of the road, and perfectly suited for the mainstream audience of the time. We are left wondering how magnificent it could have sounded with Levee’s arrangement.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is on Netflix now.

*Additional reporting by Don Kaye.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom Ending Explained appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/34zbS44

0 notes

Text

10 Beatles Songs That Could Pass For Indie Rock

There are various kinds of sounds that we associate with Sixties music, whether it’s the tinny simplicity of early Sixties Rock & Roll or the keyboardy lugubriousness of late Sixties psychedelia, and the Beatles catalogue is laden with a lot of these sounds. They have a lot of material, as great as it is, that definitely sounds like it belongs to a particular time in history.

Of course there are plenty of Beatles songs that have no such sonic timestamp, songs that sound like they could have been produced this morning, especially given a contemporary music scene that is rife with sonic exploration and adventurousness. Here are some of the tracks that could even fall under the category we know today as Indie Rock. They are all brilliant songs, of course, so when I say they could pass for Indie Rock I mean they could pass for brilliant Indie Rock of the highest order.

10. I’m Only Sleeping

youtube

Not only does it sound a lot like Indie Rock, the subject and theme is also pretty standard Indie fare. I’ve always imagined Alex Turner and Arctic Monkeys swaggering through this one.

9. Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me and My Monkey

youtube

Of course if someone made this today they would use a cowbell instead of a hand bell for full ironic value.

8. Taxman

youtube

Yes but which Indie guitarist could come close to duplicating McCartney’s explosive 12-second guitar solo, one of the best solos ever on a melting-face-per-second basis? Also, do you figure Beck has listened to this track a few times?

7. Sexy Sadie

youtube

This one’s got Radiohead written all over it, in fact, Karma Police borrows whole sections of the chord sequence, not to mention the sound and the feel of it.

6. I’ve Just Seen A Face

youtube

Marcus Mumford would have sold his grandmother to make a record like this. High-energy folk? Been there, done that.

5. Revolution

youtube

What indie band couldn’t make a simple little Rocker like this, right? Could they also deliver such an eternally famous lesson on the dangers of extremism? Not so simple after all.

4. Helter Skelter

youtube

People call this track the Father of Metal but I think it’s more like the Father of Grunge. The backing vocals in Queens of the Stone Age sound just like these, because Josh Homme is a very smart man.

3. Here Comes The Sun

youtube

This is the most popular Beatles track on Spotify at over 107 million spins, almost 30 million more than the next most popular song, which speaks volumes about its contemporary appeal. You can hear this kind of thing in the Sufjan Stevens wing of Indie Rock.

2. She Said She Said

youtube

The best indie rock record ever made. This one must leave hugely-talented Rockers like Dave Grohl and Stephen Malkmus gasping for air. The shifting tempo, the lyrics, that guitar sound, the unbelievable drumming – it just doesn’t get any better than this.

1. Come Together

youtube

This is the second-most popular Beatles track on Spotify, and it’s also one of the coolest, hippest songs they ever made, free from all that earnest love love love stuff. It’s got distinctly brilliant elements that couldn’t even come close to being duplicated, ever.

Honorable Mentions

Hey Bulldog

And Your Bird Can Sing

Dr. Robert

Glass Onion

It’s All Too Much

Dear Prudence

Long Long Long

Baby You’re A Rich Man

Getting Better

Photo credit: By Parlophone Music Sweden [CC BY 3.0 (http://ift.tt/HdA8Wl)], via Wikimedia Commons

from Rocknuts http://ift.tt/2f7XA3V

via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note

Text

Guts

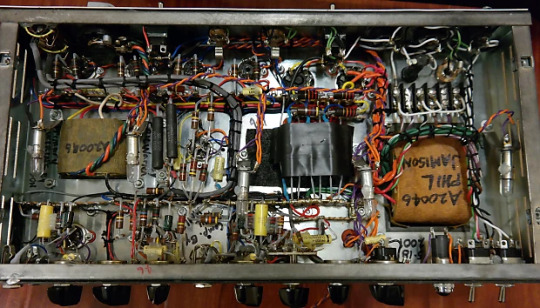

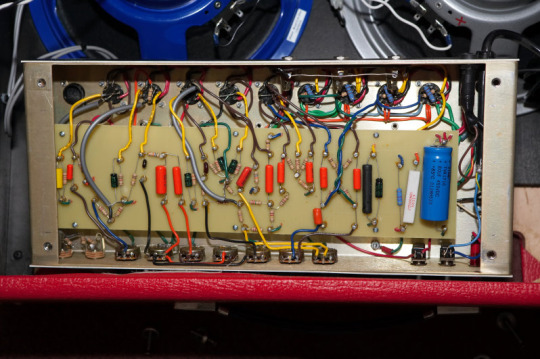

*Matchless DC-30 (point-to-point)

Today we’re going to dive into the guts of guitar amplifiers and talk about the differences in construction methods, and how that translates to sound.

Some point soon I’ll be able to speak about the different components and their functions with a more knowledgeable and experienced angle, as I continue to read up on this and begin to start building my Tweed Deluxe. For now though, I want to talk about how these things are built...for what purpose...and how that translates to producing sound at the end of a signal. I’ll be speaking on these things from a practical sense.

Lets start off with a super-condensed context before we head to the jump...the earliest amps were handwired point-to-point. In order to produce more units, and hire more less skilled labor, companies like Fender, Marshall and Vox would use what are called “eyelet boards.” These boards laid out how to wire and where to solder, and were still handwired.

Then printed circuit board (PCB) came around. You could take an eyelet board, have machines pre-wire it, then have the whole board dipped in liquid solder, saving time and the cost of human labor, while manufacturing exponentially more units with consistent standards.

The question now is “does it matter?”

***

The Matchless DC-30 at the top is an absolutely stunning piece of amplifier. I have a good bit of experience with Matchless amps...point-to-point handwired Vox (when they were owned by Jennings Musical Instrument Co., the company owned by the guy who invented the classic Vox circuit, Thomas Walter Jennings) homages...but on the smaller 15-watt Lightning combo that was designed to be a studio amp.

The DC-30 is a battleship amplifier, with a complex interactive circuit (meaning that the EQ and gain/volume knobs interact with each other as they’re adjusted), and the example at the top is about as good as point-to-point wiring gets, beautifully clean workmanship with a high degree of difficulty where every inch of wire length needs to be exactly accounted for and soldered.

...but what does that actually mean?

From a broad standpoint, your tone is a giant variable signal. It’s absolutely 100% true that things as minor as the type of pick you use...or how long of cables you’re using in your chain...or, yes, even something as granular as type of battery...all can have an impact on your tone. Laugh, but if you played with a handful of different stlyes of picks made from different materials, you’d be blown away by how different each makes your guitar sound.

Whether you give a shit about that type of granular OCD is a different argument entirely. But what I want to impress is that everything in your signal has an impact. And when you’re talking about things like amplifiers and speakers, things like wire length does have a difference.

And if you want the best sounding signal, a technical argument can be made that the best tone comes from amps that are handwired point-to-point, where the signal (the amp receives) has the least amount of time to decay. You look at the holy grails of amps...Tweed and Blackface Fenders, early Marshalls, JMI Vox’s, Dumbles, Trainwrecks, etc...each grail is point-to-point handwired.

Either because that’s all they could do during the era (Fenders, Marshalls, Vox’s) or because of the belief that the least amount of time signal can be lost, the better your tone will be (Dumble, Trainwreck, Matchless).

***

Which manufacturers who use eyelet boards and PCB would agree with 100%, these camps accurately being able to claim these methods make it more consistent and repeatable. Both sides have a point.

To cut to the chase...not only are PCB amps as good as point-to-point, they allow for a hugely expanded ability to add on features that would be impossible to design point-to-point.

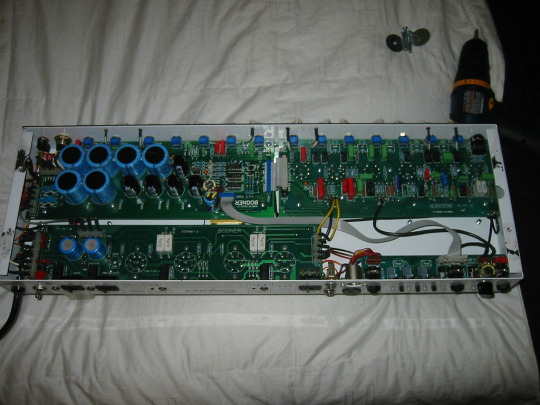

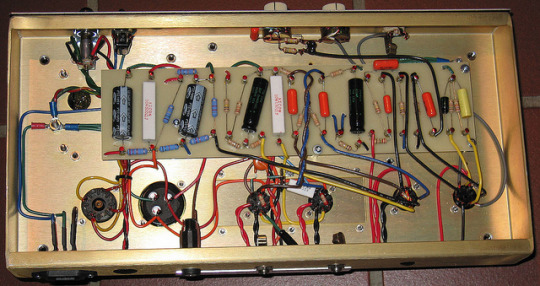

*Bogner Ecstasy 100b

I’m not even going to try and describe what’s going on with this amp because it’d take easily 1,000 words. But I’ve played the shit out of these things, and they are MONSTROUS. The PCB isn’t about mass manufacturing or not having to pay someone...it’s about being able to build multiple different gain structures, EQ sensitivities, circuit paths and buffered effects loops to make sure complicated high-gain metal and rock sounds come through as hi-fi as possible.

Here’s another PCB example that you could hardly say was about cutting manufacturing corners...

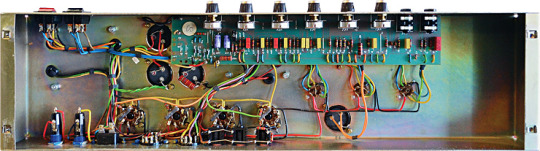

*Mesa Boogie Mark V

Three different amps in one, all with individual huge sweeping gain and EQ sections, a parametric EQ on top of all that, variable wattages...the features just go on and on. You couldn’t do this wiring an amp point-to-point.

While Mesa Boogies and I are like oil and water, I’d be a fool to say they don’t sound great. In the right hands...guitarists like Carlos Santana, Larry Carlton and John Petrucci (Dream Theater)...they can sound fucking incredible.

There’s a wide marketplace out there to find an amp that fits your style. Santana isn’t exactly a chameleon when it comes to tone, pretty much using one sound his whole career, but Larry Carlton sure as hell is. Both used similar styles of Boogies, despite approaching the guitar from philosophically different places.

***

youtube

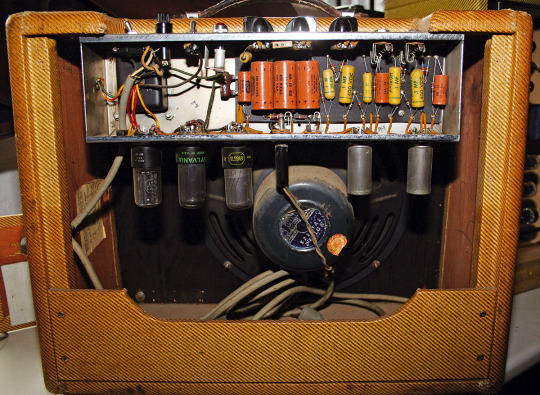

*1957 Fender Tweed Deluxe

One of the things about the early amps that were wired point-to-point by guys who really had no idea what they were doing was their little quirks. In the video above, go to 0:50 and listen for 30 seconds. Watch how that amp transforms from something nice and gritty, into this screaming hell beast by turning the knob for the channel not being used.

That’s a quirk that can be deliberately wired into a point-to-point amp...every one of the multitude of Fender 5e3 clones has exactly this...or a handwired amp using an eyelet board can be built to operate like the traditional amps everyone is used to, but still benefit from the sonic benefits of very deliberate construction.

*Dr. Z Maz 38

...or a amp builder could decide to make an amp that has a very wide range of EQ and gain settings, but puts the sausage recipe behind a curtain so the user doesn’t get overwhelmed, only having to turn a volume and tone knob. Looking at the control panel, you’d never know how much is going on behind the scenes to sculpt the end resulting tone.

youtube

*Dr. Z Carmen Ghia

If you go to 1:45 in the video above, you’ll hear how much that tone control changes the guitar’s sound, and you’d never how much thought and deliberate wiring went into the design of that amp if you just looked at the two knobs.

And that’s the thing...you can get great sounds from either one.

***

Lets finally get to the practical differences. Tone is subjective, and you can get great tone from anything as long as you know how to play. However there are pro’s and con’s to point-to-point vs. PCB...

Point-to-point is going to give you the purest, highest-quality signal, specifically designed for one or a small handful of purposes. The easiest tradeoff is expense...you’re not likely to find any point-to-point wired amps suitable for a studio or practice room under $1,000. None that are the size able to be played in a club for under $2,500.

If they’re lightweight, you’re sacrificing any versatility because you have a one-trick pony. If they have a lot of versatility, they’re heavy...because a lot of components and big transformers add up quickly. But you get that incredible tone...

You also get the easiest repairs and longest lasting amp. There’s no guesswork or any Achilles’ heels in point-to-point amps. For simple repairs, some vacuum cleaner repair shops are able to handle it. Soldered connections typically are more solid and last longer. Construction is typically more robust...if you’re going to take the time and effort to build a point-to-point amp, you want it to last.

For musicians with a defined sound that don’t have to cover a lot of bases, there’s no argument against point-to-point amps. Economic arguments only last as long as asking these types of musicians how many amps they own. It’s typically not many. One point-to-point amp is the same outlay as buying two or three PCB amps, and if you really only use one or two sounds, you don’t need more than a single amp.

***

PCB is a little more complicated. Yes, you can get great tones out of them, but not all PCB is created equal. For those high-quality examples above, using thick, hardy circuit board and consciously thinking about the wiring, you have the big boys.

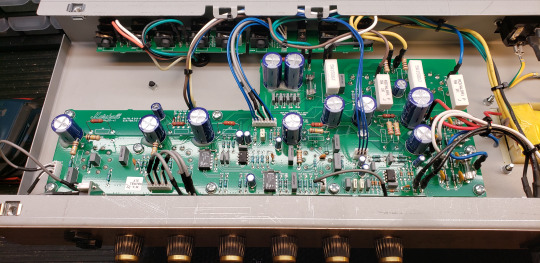

*1981 Marshall JCM800

*2019 Marshall JCM800 reissue

Here are the downsides to PCB.

Firstly, you’re paying more (when adjusted for inflation) for inferior components and subsidizing Marshall’s profits while they sell you a product for the same price that required exponentially less labor costs. All for a very simple amplifier circuit.

There’s a concept called BIG IRON in the guitar world. It’s hard to say it’s definite or end-all, because it’s hard to call PCB-based Bogners and Boogies BIG IRON even if they’re more than capable of holding their own in that world. BIG IRON refers to massive transformers, huge tubes that led to that beautiful overdrive we came to love in the 70′s and 80′s. Marshall literally is the godfather of BIG IRON.

Well new Marshalls don’t have anywhere near the reputation of their forebears for a pretty easy to spot reason. Those moves done to save money came at the cost of their soul. They just don’t sound anywhere near the same.

That alone would be worth enough to slam the book shut on PCB, but the other big problem is durability. You can’t really tell from pictures, but I’ve touched the Boogie and Marshall PCB’s in real life...the Boogie’s is thick, robust, high quality and proprietary. Marshall’s is barely thicker than a nice business card.

When you’re mounting tubes onto PCB, quality matters. Those bottles heat up and can warp the board and dry out the solders leading to cracks. That method of dipping PCB in liquid solder is great for convenience, but it’s not as durable as doing it by hand. And if anything goes wrong in the PCB, it’s not a trip to the vacuum repair store...it’s digging a grave.

***

We’ll get into the parts and functions of these things in more detail once I start building my Tweed Deluxe. I’ll be wiring it by hand using an eyelet board (provided), but the goal is eventually to build one point-to-point.

That’s all i got for today.

0 notes

Text

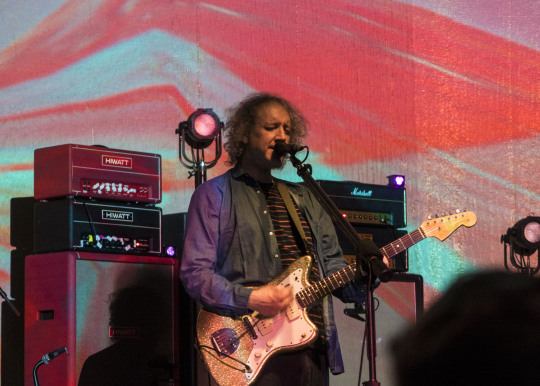

My Bloody Valentine

O2 Institute, Birmingham

Friday 22nd June 2018

Kevin Shields is not a man in a hurry. With the special guests advertised on the tickets failing to materialise, the venue tweeted that the headline had a lot to get through and suggested that we arrive at 8:00pm. Most heeded this advice and on a hot summers evening, the hall was already full by this time, bodies uncomfortably close adding to the oppressive heat so that beads of sweat could be seen on those near the stage. Then we waited .... and waited, conversations that had earlier shown an enthusiastic level of participation had dried up leaving faces gazing hopefully at the stage with just the faint sound of the background music to keep their interest. Four spotlights were lined up across the back of the stage, their brightness hypnotic in the gloom, giving some distraction from the roadies who having apparently completed their duties, would soon be back repeating the task to the exacting standard required. Pieces of paper were frequently exchanged, one suspects they held the setlist but once taped in place, another would soon appear, even at this late stage, the order being changed until it was just right. Then, Kevin Shields has never been a man in a hurry. Over the course of three decades, the band he put together to realise his vision have managed to complete just three albums and a handful of EPs and singles. This included a gap of nearly a quarter of a century between albums numbers 2 and 3 during which others built entire careers, governments would rise and fall, planes didn’t fall from the sky in the new millennium and even the never ending sale at Allied Carpets came to an end when the company went into administration. Once contemporaries of Nirvana and The Stone Roses, they would find their latest opus alongside Katy Perry and Miley Cyrus; not that this passage of time can be heard. The sound is of its own, existing in an unchanging world that only incidentally infiltrates our own to leave its apocalyptic imprint. It is as if a chord struck in the early nineties was left to reverberate over the years until being picked up again many years later.

The level of productivity is pure slacker but is mostly based on Shields’ unrelenting perfectionism. Whilst the 1991 album “Loveless” is now, contrary to its title, widely loved, it was not by the record label who, frustrated by delays and production costs, dropped the band following its release. Its creator, however, still seems to very much regard it as a work in progress and its rerelease was delayed by four years as he continued to tinker until he found that elusive sound that only he could understand. Marking their first appearance in five years, this concert shows the same painstaking attention to detail and despite seemingly having been prepared, there are a number of interruptions when Shields feels that the sound isn’t what it should be. Inevitably when the number starts again the difference is imperceptible to everyone else and whilst Shields himself seems to hear it, you feel that it is still not quite right. Then this was really what this show was about as the following day will see them at The Festival Hall as part of the Robert Smith curated Meltdown and this is the hastily arranged warm-up. Rather than an overwhelming desire to play in Brum, the Institute was no doubt chosen as it was a convenient venue that had a gap in its schedule but when I received an email about three weeks before announcing the concert, I knew I had to take advantage of what was a rare opportunity to experience the MBV. Convenient it may have been but the Institute has its own sonic vagaries that seemed to cause Shields so much frustration, even during the parts that were allowed to run normally, he would often be engaged in animated discussion with the technicians or stand with his ear pressed against the stack of Marshall amps in attempt to isolate that elusive moment of sonic perfection.

Loud, it was loud. Having passed through security and having our tickets scanned we are handed a small packet that contains two foam ear plugs and once inside one of the security team walks around advising us that we should wear them. We decide that, at our age, we no longer have to prove our mettle and put them in but the orange foam can be seen in the ears of even the younger members of the audience, that is aside from those experienced in the MBV who have brought their own. This may all sound a bit “elf and safety gone mad” were it not that we saw The Jesus and Mary Chain at the same venue last year where no one felt the need to provide us with foam ear buds not to mention Shields stint with “Xtrmntr” era Primal Scream which has to be the concert that caused the most long term damage to my hearing. Rather than noise level regulations, then, it is the band themselves who insist on the ear protection and it certainly helps to introduce a level of apprehension as you contemplate the battering your senses are about to receive and wonder whether you will leave the same person as you were when you went in. At the start of “Cigarettes In Your Bed”, Shields exchanges his Fender Jaguar for an acoustic guitar, usually an indication of calmer waters and a bit of deeply introspective folk. Instead it triggers another brutal assault, the vibrations of the strings carried through an array of effects pedals and a stack of speakers until it emerges shaped and distorted into the maelstrom. This does, however, serve to show that there is more to MBV than just sheer volume, the sound is distinct, it gives a different feel showing the texture and nuance that helps to justify the laborious methods through which it is produced and the volume at which it is played.

Two microphones are set across the front of the stage behind which Shields and fellow guitarist and singer Bilinda Butcher add their voices to the mix. MBV, however, are not really about words and the levels of the vocals are set so low in the mix that they feel like a ghostly voice that has appeared from another dimension. It is the feel of the music that is important, how the guitar assault plays on our emotions: I’m sure someone has deciphered the words but knowing them certainly won’t enhance, and maybe even detract, from this. Butcher stands close, mouth pressed against the microphone and only changing her position once to add some keyboards. Behind her, an array of speakers in front of which Debbie Googe adds the rumbling bass, the depth of the which sounds surprising given that she seems to play most of it on the higher frets. Drummer Colm Ó Cíosóig occupies the gap between the speakers leaving the other side of the stage entirely for Shields’ slow wanderings and the pedals, effects and other gizmos he uses to coax the strange sounds out of the six strings across which his fingers move. A fifth member of the band is hidden away in the corner, occasionally adding the repetitive signatures that identify the numbers or a burst of additional guitar. Whilst the space he is given represents Shields creative input, MBV are very much a band. Ó Cíosóig and Googe are a formidable rhythm section; despite its apparent disregard of many conventions, the music is structured around a regular, if changing, beat that Ó Cíosóig uses his sticks to count in, something that seems surprisingly rock ’n’ roll. With her demure expression and dressed in a smart blouse, long skirt and heels, Butcher could have be heading out for an intimate meal before taking a wrong turn and finding herself here. Her sweet voice manages to sound both equally incongruous and just right whilst her playing is an integral part of the twin assault of the two guitars.

A burst of feedback and the screeching “I Only Said” signals that this assault has begun and that we are at the point of no return. Patterns play out of the screen behind, projected from the balcony so that the colours fill the whole room whilst the faces of the musicians remain obscured in shadow. In a way this seems appropriate as the sound does seem a little muddy, the playing is wonderful, particularly Googe’s bass and the fills provided by Ó Cíosóig but overall it doesn’t quite capture the magic of the recording. “When You Sleep”, another from “Loveless”, follows but again, by now to Shields’ obvious frustration, doesn’t quite hit the spot. Two thumping drum beats start “New You” and eventually things begin to click with a wonderful lumbering baseline from Googe securing the carefully constructed textures that are starting to emerge. The technical problems weren’t completely over but after a few false starts, things did pick up and where they didn’t, Shields accepted that he had to live with them. The sound problems persist through the favourite “Only Shallow” but when it does gel to we get the overwhelming thrill that we were expecting. The multi layered “To Here Knows When”, played almost solo by Shields, was far noisier than its recorded version and the surprisingly bright melody of “What You Want” managed to make itself heard amongst the thrashing feedback of the chords. “Slow” found a thumping solid beat and a deep grungy bass and the urgent repeated hook of “Soon” made it a brilliantly infectious highlight. “Wonder 2” saw Ó Cíosóig abandon his drum kit to add yet another guitar to the white noise that drowned out the programmed beats before returning for the thrashing “Feed Me With Your Kiss”. The thrilling finale of “You Made Me Realise” was immense, once upon a time it was 3 minute, fairly conventional, aside from a few seconds of noise, song very much of its time. Since it has grown to the immense, tumultuous storm that it now is; the conclusion that MBV fans call the holocaust. Ó Cíosóig pounds at his drums, Googe’s bass is felt rather than heard and the searing feedback of the guitars is relentless is its terror.

By now we had made our way to the back of the hall in order to make sure we would get to the station in time to catch the last train. Leaving, I remove the foam from my ears and we are soon able to hold a conversation without having to overcome any ringing. The protection they offered was probably minimal and they are given out more for effect but they did at least seem to cut out the noisier aspects of the holocaust. After five years away there was always likely to be a rehearsal element and the false starts and technical problems did make for a show that at times seemed shambolic but in a way it was ever thus. Despite all that, it was enthralling, bizarre and quite unlike anything else you will hear. The perfection of the sound in Shields head is something he will never be able to achieve but his quest is fascinating and occasionally we get to hear it. It could be a while before we get another opportunity.

1 note

·

View note