Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Art, Community, and Love

By Sally He

"Action and speech create a space between the participants which can find its proper location almost any time and anywhere." This quote from Hannah Arendt serves as a profound foundation for understanding the essential role of art in deeply engaged community projects. Arendt’s idea that action and speech generate relational spaces highlights the dynamic, fluid, and transformative nature of human connection—spaces that can emerge anywhere people interact meaningfully. In the context of community engagement, art takes on the role of a silent yet powerful form of speech, creating such spaces through its ability to adapt and resonate across various forms.

Art becomes a melody that links emotions, food that nurtures relationships, or dance that synchronizes bodies and spirits. Most profoundly, it is always tied to love—love that manifests in the act of bringing people together, sharing their stories, and building understanding. This is what I felt so strongly during the Brooklyn Museum speaker’s discussion on the transformative power of art. Art here is not simply a medium or a tool; it is a force that delicately yet firmly binds individuals, fostering an invisible yet enduring connection. It is a kind of silent speech that transcends language, subtly weaving people into a unified whole.

At the beginning of this semester, I did not fully grasp the deeper significance of community or what it means to engage with one. My initial understanding was limited to abstract concepts, but meeting people who are deeply rooted in their own communities transformed my perspective. Their stories, filled with resilience, creativity, and love, profoundly moved me. It was through their experiences that I began to understand the central role of love in community engagement.

Love, in this context, is not a mere sentiment but a driving force that underpins the creation of safe and welcoming spaces. These spaces are not only about physical safety but also about emotional and psychological security—places where individuals feel valued and understood. However, crafting such spaces is incredibly challenging. It requires not only creativity and care but also a deep commitment to understanding and inclusion.

Art plays a unique role in building these safe spaces. It bridges divides, fostering understanding and empathy in ways that words often cannot. It invites participation, allowing individuals to contribute to the community in meaningful ways. Whether through a shared creative process, the collaborative production of public art, or the simple act of experiencing art together, these moments create a sense of safety and belonging.

Creating a space that feels safe and ensuring others feel safe within it—is an intricate, ongoing process. It demands sensitivity to differences, respect for stories, and an openness to change. Love, in its most practical form, becomes the foundation of this effort. It is love that drives the artist to consider the needs of the community, and it is love that enables members to come together, transforming a collection of individuals into something greater.

As I reflect on this journey, I realize that my understanding of community engagement has evolved into something much deeper. I no longer see it as a framework or a task but as a living, breathing process grounded in human connection and care. The spaces we build through action, speech, and art are not just locations; they are the embodiments of our shared hopes, struggles, and love.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Decentering Discomfort

by Neal Flynn When Chip Thomas, artist and healthcare provider, virtually visited our class in NYC from Arizona he introduced us to his family. He was alone on the call, but he started off with stories about his heritage and shared pictures of his grandparents and his childhood in North Carolina. Thomas left the east coast in the 1980s and worked as a physician in a Navajo Nation clinic from 1987 to 2023. He began the the Painted Desert Project in 2009, a public art initiative rooted in sharing by connecting “public artists with communities through mural opportunities on the Navajo Nation”. On the call he told us about his lack of artistic training, his passion for DIY interventions, and his interests far outside of medicine in the NYC punk, hip hop, and graffiti scenes.

I was struck by many aspects of his virtual visit. I admired his strategic use of limited time with us. I was inspired by his candor despite knowing very little about us. He asked questions about who we were and what we already knew (what we had gleaned from his website and from information shared by our classmate, Meghan), and assembled a presentation accordingly, on the spot. He was calm, organized, and responsive, modeling the qualities of an expert in patient care. I was surprised that someone with such an aptitude for the fast-paced nature and creative economy of urban life would choose to apply their skills in a way and place that was in many ways the opposite of NYC or another major city.

Chip’s generosity was a reminder that my comfort zone is a limitation. As someone eager to build a more community-oriented practice, hearing from Chip made me aware of how my tendency towards the familiar could be hindering the possibilities of what my community work can be. I thought about how my ‘comfort zone’ limits my work in the community, and could be making my work less meaningful and impactful for others. The more connected my practice is to my own wants and needs the less likely it is to satisfy the wants and needs of folks whose positionality differs from my own. Chip was drawn far away from the places he knew and grew up in, far away from where he studied medicine and experienced his favorite art. In this far away place he built an even more interdisciplinary, more vital practice (and saved lives at the same time). I am grateful for this reminder to prioritize learning and recognize that discomfort might be a norm in that learning.

Photo: Fronteras Desk

1 note

·

View note

Text

Turning Mirrors into Windows: My Journey in Community-Based Art Engagement

Eloise Sun

Sydney J. Harris once said, “The whole purpose of education is to turn mirrors into windows.” This quote perfectly captures my journey in this course. Education, as Harris suggests, broadens our understanding and connects us to something larger than ourselves. This semester, I experienced that transformation—moving from introspection to engaging with diverse perspectives and the broader social fabric.

At the start of the semester, we were asked to write a manifesto. In my journal, I wrote:

“Art offers a way for communities to think and heal. We are part of our work. Be yourself and be honest about who you are.”

These words reflected my initial belief that art connects with communities through the artist’s self-expression. By the end of the semester, my understanding had completely shifted. Community art is not about imposing an artist’s vision—it is a collaborative process where the community itself is central.

Initially, I saw community art as large-scale, top-down projects led by governments or cultural institutions. These projects often felt disconnected from the people they were meant to serve. However, this course challenged my assumptions and expanded my horizons. I began to see community art as an ecosystem—diverse, complex, and collaborative.

French art critic Catherine Grout offers six key principles of public art: reception, communication, integration, inclusivity, diversity, and process. She argues that true public art emphasizes interaction over imposition and harmony over disruption. This redefined my understanding of public art, helping me see it as an interconnected system that thrives on collaboration and shared purpose.

One example that highlighted this tension was Arne Quinze’s Natural Chaos, a public sculpture in Dongguan, China, that cost 30 million RMB. Despite its ambition, the work failed to resonate with local residents, clashing with its surroundings and drawing widespread criticism. This reminded me of our discussions about Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument (2013), where the artist’s vision overshadowed community agency. Both examples made me question: Who is public art really for? If it doesn’t reflect the community’s needs, can it still be considered public?

In contrast, guest speakers Laura Alvarez (BxArtsFactory) and Meghan, who introduced us to Chip Thomas’s work, offered a more inclusive approach. They emphasized that the community is not just a recipient of art but an active participant and asset in the process. Community art is most impactful when artists build genuine relationships, listen to the community’s needs, and collaborate authentically.

This shift in perspective shattered my earlier assumptions and opened me to a more inclusive, ecosystem-driven view of community art. Hands-on experiences, like creating zines and exploring Beautiful Trouble, reinforced this lesson. While I may not remember every reading detail, I vividly recall the practical principles I learned through collaboration and action.

As I reflect on this semester, I feel immense gratitude for this journey. Community art, to me, is now a living, breathing practice rooted in connection, collaboration, and shared purpose. Education has truly turned my mirrors into windows, helping me see a broader world and engage more deeply with the people and communities around me.

I absolutely love my classmates and the atmosphere we’ve created. It’s incredibly supportive and warm. I truly adore my classroom community!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Building Community Through Art: Lessons from Creative Changemakers

Polina Orlova

As a Clinical Psychology Master's student, I wasn’t sure what to expect from this class when I joined. I knew only that I wanted to explore how art is used in practical, community-centered ways and understand the kind of drive it takes for artists to work collaboratively. What I have gained from this experience has far exceeded my expectations. I’ve been introduced to a range of artists from diverse disciplines who have discovered topics they are passionate about and devoted a significant part of their lives to pursuing.

Meeting Mia was especially impactful. She brought art into prisons, creating a sense of community within these closed-off spaces. Mia was remarkably honest about her work—it requires a great deal of time, dedication, and support, especially as accessing a prison isn’t easy and relies on a network of volunteers. Witnessing the murals she created alongside inmates was powerful; her work transformed a typically harsh environment into one that feels warm and welcoming, a stark contrast to the usual prison atmosphere. Our hour-long session making murals together became an unforgettable bonding experience for all involved.

Our next session introduced us to Leia from the Broadway Advocacy Coalition. This was my first time witnessing theater being used as a form of activism, and I found it truly inspiring. Leia stressed the importance of involving people who are directly affected by the issues in active roles throughout the process. She emphasized that “no project is more important than a person,” a sentiment that deeply resonated with me as a psychology student. Like her, we focus on keeping people at the heart of our work.

Meeting Clare from Cartie was equally inspiring, as she demonstrated how a simple idea can blossom into a substantial project. Clare shared the tremendous amount of effort required to coordinate with multiple schools—all while completing her PhD. Her diligence and caring spirit were obvious, and her work showed just how much can be accomplished with a single bus. Clare’s story has motivated me to continue pushing for my own dreams, regardless of how challenging they may seem.

Each week, I’ve also felt deeply impacted by the class environment. As a shy person, I’ve truly appreciated the atmosphere of openness and support. Everyone is kind, collaborative, and highly creative. Hearing my classmates’ unique perspectives, shaped by their varied backgrounds, has made me feel like we are part of a small yet powerful community—something I haven’t experienced in any other class. Marissa and Ayelet have done a remarkable job curating this experience, fostering a space that promotes growth, knowledge, and community.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Defining Art in Relation to Community Engagement

Meghan Duval

For seven weeks I have sat in my Community Engagement class and week after week, I have learned about one impactful and community changing group after another: Arte, JIE, BXARTS Factory, Broadway Advocacy Coalition, Laundromat Project, etcetera. Each story about the process and product of the work is as impressive and inspiring as the one before. Within the room as the narratives progress, there is no doubt about the positive ending. Yet, it occurs to me that with all our expertise and belief, we have failed to clearly define the mechanism in action that delivers these reliable outcomes. Ever since I read bell hooks, all about love, in which she defines the illusive and amorphous topic, I have been a convert to the power of definitions. Hooks, says, “Our confusion about what we mean when we use the word “love” is the source of our difficulty in loving. If our society had a commonly held understanding of the meaning of love, the act of loving would not be so mystifying.” What if our society had a commonly held understanding of art? How would that shift our relationship with the arts? Would art class be guaranteed to be among the core instead of the extra curriculum? Would community arts organizations be amongst the first and not the last line items to get funded?

Defining art has been the mission of philosophers and artists for centuries. So, I am empathetic to the confusion. Luckily, during the week I also sit in another class: Philosophies of Art in Education. In that class we have come to the work of Alva Noe. Noe offers a definition of art equal to hooks’ definition of love. I summarize Noe’s definition as: art is that object or experience which offers us an opportunity to realize ourselves as creative. Noe bases his definition in the making of meaning by observing a work of “art.” I like to extend it beyond the limitations of art viewing and apply it as broadly as possible. The definition may sound simple, but it is immensely clarifying. Art is that which reveals us to ourselves to be creators. Let’s look at another definition, from Oxford Languages online: to create: to bring into existence. Thus, we can say that art is that which enables us to bring into existence objects and experiences. And one more definition, Webster’s online dictionary defines power as: an ability to act or produce an effect. I hope it is becoming clear where we are going. Art offers us the experience of being powerful. The power may be limited to our object of creation, a moment in time or even just over a thought. Yet, in a world in which we are barraged daily via our various technologies with images and realities over which we have little to no influence, one can imagine how satisfying it is to have even a little experience of power. Now extend the experience to the incarcerated, marginalized and overlooked communities and imagine what a difference it can make to experience one's power no matter how contained.

It is here that we have to ask ourselves the most important question: Is our cultural ambiguity about the value of the arts with its commensurate requirement to constantly plead art's case due to our confusion or our clarity? Perhaps we know that art in all its various forms is empowering, and we simply do not want to meet the consequences of that part of the definition.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Farah's Reflection

“The arts, it has been said, cannot change the world, but they may change human beings who might change the world.” - Maxine Greene

As you enter the double doors of the studio space these words are etched in the wall. A call for action and a discernment for anyone who dares view art as humanity. Curiosity thrives in this space as the chairs and foldable tables make for artistic expression. We huddle together to charter new ideas with tact and relevancy. The time to pull up a chair arrives with the question “Who?” enters this room. How do you enter? How do you leave? What art, conversation, creation may change you in between? Throughout the semester the classroom transformed into many formats. Some of the orchestrated groupings were peer presentations, guest speakers, and personal reflections. We had a Monday night class. Hauling ourselves to school at 7:20pm in pitch darkness shows a dedication to art and creation that moves me. I learned to love Mondays because of this class and would look forward to the weekly experience.

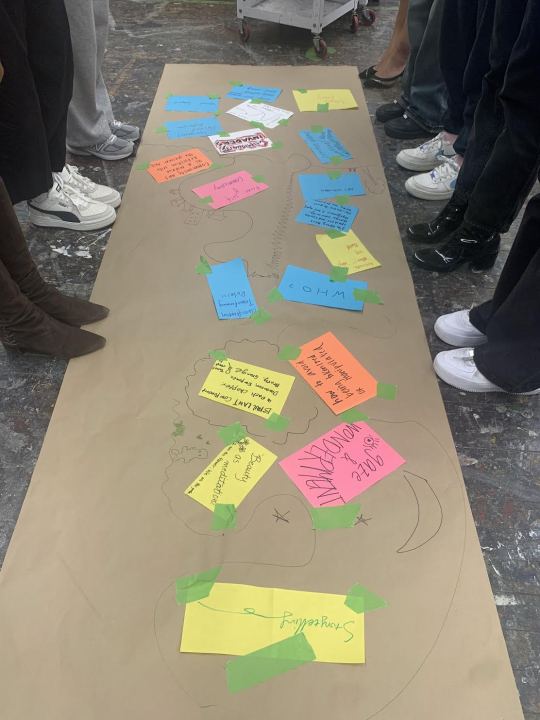

One part I thoroughly enjoyed was the deliberation of connecting common themes and story mapping our vision together. Where does this piece go? How do we relate to it? Do these ideas connect? As a cohort we created this experience as artists of our own community. Bringing ourselves to a cohesive piece of work. Each student’s lived experience adds a layer to our collective vision of art.

The butcher paper rolled out like a carpet had the physical artifact of “Visual display” etched at the bottom. Moving through the artwork the viewer moved up across the landscape questions emerged such as “Who?” Reflections answered, “Community art as a mirror, reflection in personal art.” Juxtaposing ideas with forceful shake-ups like “Community invaders.” This phrase is oppositional in theories to “beauty as meditation.” The language of “common ground stumbling block” gave me pause. I wondered how you create art for the community that is deep and meaningful and perhaps somewhat messy? How do we honor each person in this space? This piece of art showcases transformation of art within each other. I’ll end with the quote that I began from Maxine Greene, “The arts, it has been said, cannot change the world, but they may change human beings who might change the world.” This was us human beings on those Monday nights through experiential learning in that studio creating Art as Community Engagement.

Len Catron, M. (2017). A better way to talk about love [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/mandy_len_catron_a_better_way_to_talk_about_love/transcri pt?language=en

0 notes

Text

A lesson learned during class:

i found out that every art in some sense is about community. artworks that we deeply relate to are about ourselves, about parts of us that feel acknowledged in the art. maybe all our lives we are looking for a feeling that we are heard, seen and valued? maybe that is why art is so powerful?

A reflection on a class activity

i generally deeply enjoyed my time in class and i especially enjoyed the creating activities. it feels so good to work on something physical without expectations and i rarely have this experience

overall, i feel so grateful to Marissa for this semester, it was a pleasure to be in this class

A deeper understanding of community-based art engagement

as i said before i came to realization that all art is about community and that being said i feel like there is a conflict with measuring engagement in terms of expectations and intrinsic value. in our capitalist reality everything is measured in money equivalent and with community engagement that doesn’t work like that. we cannot evaluate it on any scale and i also believe that we shouldn’t in the first place. so now im thinking about financial system that doesn’t involve evaluation and competition because the main problem that divides us from ‘just let this exist’ is money

also i keep thinking about that people who accumulate enough fortune tend to come to art. as creators, as admirers. and i keep thinking maybe because art is what everyone wants to do? maybe art is a great connecting power opposite of violence? maybe it is too idealistic to think that and romanticized art but art has proven to be a solution in certain way and im thinking maybe we as humanity haven’t fully understood the potential of art power

PS i have no idea what image i am supposed to add so im adding this gif

by alex

0 notes

Text

Personal Manifesto: We are talking to the ideal world

This kind of contemplation happens often in my life. When I stand in the galleries, in front of the extraordinary works in the museums, in front of the seemingly irrational graffiti on the street corner... I always get caught up in thinking: What is the interrelation between me and art? What have we done for each other? It has so precisely taken over my life for so long. Despite from the beginning, our encounter wasn't even my personal choice. Like every parent who believes in the importance of art interests in elite education, I was sent to a painting class when I showed only a slight interest in painting. After that, I have continuously interacted with art for the next twenty years.

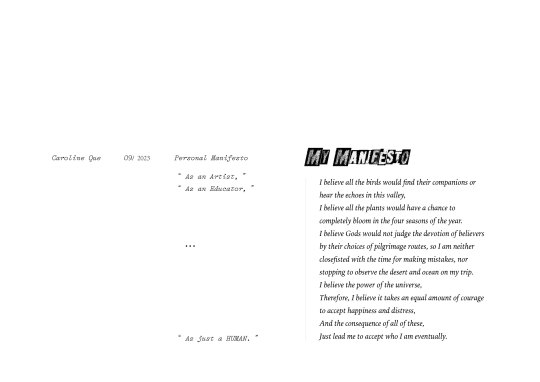

Nevertheless, I am desperately eager to know this interaction's significance - that's why those contemplations happen. They are often like a tsunami, flooding my mind without warning. It's different for this time; it happened because I was assigned to write a Personal Manifesto for my art engagement class. This progressive assignment asked students to create a personal manifesto in the literal form and then transform it into a visual expression. Then, share with the rest of the class and facilitate the conversation and discussion about the arts and experiences.

I looked around the walls of my room; there were the paintings I'd drawn, the designs I'd done. At a time when all actions need to have a specific purpose and output, I never reckoned art to be merely a tool for me. On the contrary, our relationship is one of absolute equality. Like an old friend from childhood, she can accurately convey the thoughts I don't know how to phrase and express in many moments without confirmation. Thus, when I wrote this manifesto, I sounded more about my faith and beliefs towards the world and self-recognition instead of promoting the position of arts in my life.

(My personal manifesto, 2023)

While visualizing my manifesto with collages, art became the mirror that told the truth. The reflections were not about my hypocrisy but the perceptions I once could not see clearly and directly. I'm not a planned creator; I follow my intuition and emotions. The resulting artwork, however, was more of a psychological sand-play for me - it reinforced my belief in the relationship between me and the arts as equals. I didn't endow the meaning to my art; our conversations kept happening, and even my art was the one always explaining what kind of person I was. I also felt this in the discussion in class. To be more specific, the charm of individuality was particularly intense when each person presented their visualized manifesto. You can see from each work how people perceived the external world, connected with their inner world, reflected their ideal world through the languages of art, and formed their philosophy.

( fellows' visualized manifesto, 2023 )

I suddenly understood my relationship with art in the process. We are never on the opposite sides. Everything that happened was about breaking, reorganizing, and constructing. The final artwork, or artistic intervention, is our dialogue with the ideal world. Creative engagement is never just about enlightening society; artists should not see themselves as saviors or advocators. All we do is concretely make our ideals happen, and what everyone gains from this process should be inclusive. Imposed views are just a different expression of colonialism, and art itself has everlastingly been an honest and open discourse.

Written By Caroline Que

0 notes

Text

Community Arts Participation: Connection, Cohesion and Social Responsibility

This semester's courses have triggered some thoughts for me……

Community-based arts engagement emphasizes the arts' role in nurturing social connections, constructing community, and bolstering cohesion. It extends beyond displaying artworks to collaborating with the community in creating art, providing arts education, and addressing societal issues. This form of engagement empowers individual voices, fosters cultural exchange, and fortifies community identity. Amid social pain and injustice, community arts serve as a tool for healing and resistance, uniting individual and collective efforts to transform the social conditions causing such distress.

Artists, as custodians of human culture, bear increased responsibility for human, national, and societal well-being, showing heightened concern for human development and the implications of change. They should embody a sense of social responsibility and purpose, attuned to the contemporary era and society at large. Their art should reflect a sensitive understanding of the external world encompassing politics, economy, ethics, morality, ecology, and the natural environment. Through the language of art, artists express their insights and emotions, encompassing the essence of beauty in art.

Embracing reality, the vitality of artworks lies in their value to the present and the future. In today's materialistic pursuit and amidst the crises of natural and spiritual ecology, artists bravely articulate the other facets of real life — aspects of civility, morality, conscience, and value; reverence for life; and respect for the natural world. Attending to reality stands as the essence of an artist's soul.

By Xinran Shi

0 notes

Text

Justice-In-Education Initiative

Binyao Hu

Near the end of the semester, when I summarized the impact of this class on art community, I found that Mia Ruyter's "Educational Justice Project" left the deepest impression on me. It deeply integrates art community and humanistic education for us. Provides an exceptional academic experience.

Before this, I had never associated the words prison system, education, and art together, but after listening to Mia Ruyter’s speech and browsing her website, I had a revelation: in the prison system, we are not just Transferring knowledge also creates a learning environment with emotional support and recognition. Through arts and humanities education, we help them express their inner feelings and stimulate creativity, thereby promoting them to participate more actively in learning. This interactive education model not only helps develop individual skills, but also emphasizes social responsibility and humanistic care.

Not only that, the arts community plays a critical role in the Education Justice Project. Through a variety of creative projects, we are able to deliver the idea of educational justice to a wider audience. As a medium, art not only conveys information, but also guides people to think deeply about social inequality and the role of education. At the same time, whether the recipients are students or criminals, they have the right to receive artistic treatment.

Through the "Justice in education Project", I learned to cultivate deep humanistic care, inspire a sense of social responsibility, and contribute our strength to promote a just and equal social development. This is an unforgettable academic journey and a profound expansion of social responsibility. Finally, I will continue to pay attention to the progress of such projects and hope to contribute to this.

0 notes

Text

Reflection: How did we learn from justice education in Arts emphasis design?

Innamets show off crochet creations in Brazil Prison Fashion Show (2019)

When the semester ends, does it strongly relate to 'Social justice' and 'Prison Aesthetic through rebellious compliance?' I will say yes because Mia uses a clear illustration by combining emotional engagement through the presentation of our course, thus giving me tons of fresh perspectives and sensory compliments about how to use the approach of appropriate language in jail as a guide. On the other hand, how do we use fashion to draw up our subconscious to make the community more dimension and vibrate? It reminds me of the TV show I've seen before, 'The Orange is the new black', which contains the empowerment of jail consistents; it does give me a reflection to wonder which accurate references or platforms we should have to promote with our 'Artists' motivation'? Prejudice and Jealousy?' 'Bullying and defamation?' Although it shows suitableness, it could detect the concurrent atrocities in the jail process. In addition, the public sector needs to shift to fetch the 'Cultural heritage' in social learning, thus creating a secure environment to enrich cooperation in incarceration issues. Ultimately, I might be worried about how to relate the 'Artists' as strategies of aesthetic fashion creatures in the incarcerated place. Did 'Artists' have internal attributes (e.g., Potentiality and Validity, social fundamentalism rights and so on) in a designed locality? How do they represent their identity from outward appearance through inward fashion? Could we relate each artist's living experiences by reflecting on their exclusive art craft?

Stepping into the exclusive case study with Mia by examining her JIE project as a social relation strategy gave me new confidence to pick up how 'Artists' could use drawing as an abreaction tool to realise their anxiety and negative space. Prison would be a security place that does increase the amount of stress, ADHD and PTSD in locked segments. With the development of the narrative method in Film clips, the elements would give participants a scope to represent how 'Violence' and 'Darkness' would happen when we are suffering. Mia became a good listener in the course to components of healing through psychological attention as a person. According to the experiences of people who have always been criticised in prison, we should potentially focus more on a minority of social ecology in a particular environment to give an innovative perspective through the new classical feeling in the JIE program as an art educator. Overall, the original definition of 'Prison' should be changed to a building we are trying to help each 'Artist' get a new commitment to survival.

On the other hand, this community art engagement would give a new creative approach to facilitating the innovation of art connections and aesthetic bridging. It does give me a self-valuation about how to get a sequence of transformations through the theory of 'Community embodied' and 'Audience engagement,' The lens of study in this course would give me a clear sent about how to provide an 'Emotional engagement' in conversation analysis, thus by coding the project will looks more validity and loyalty. I always have trustworthiness in defining 'Arts,' which becomes a proper solution to make invisible interpretations, thus minifying the complexity of social proof in my group project design and reshaping my inward thinking of further research study.

Ultimately, the art of innovative expression could balance our identity, affirmation, and the limitations of breaking through ourselves.

Zihao(Bobbie)Yan

0 notes

Text

Impactful Journey in Prison Arts Education

For me, the most thought-provoking class was the one where Mia Ruyter, the coordinator of the Justice-in-Education Initiative (JIE), actively participated. The Justice-in-Education Initiative brings educational programs to individuals impacted by our flawed justice system and involves the Columbia community in the movement to end mass incarceration. Mia's sharing of her experience with arts education in prisons for the public good prompted me to reconsider the definition and promotion of arts education in our society. It seems perplexing that when we contemplate the relationship between arts education and society, our focus tends to disproportionately favor the education of youth, neglecting the potential impact that the arts can have on the broader population. Due to the chronic lack of attention to the arts in our society and widespread misunderstanding in public opinion, there is a need for popularizing the arts beyond just educating youth.

Before encountering Mia and her JIE project, prison had always been a nebulous concept for me—something existing only in movies and TV shows, fraught with stereotypes. However, Mia's experience urged me to reassess the necessity for arts education to extend into often overlooked places, whether they are considered controversial or involve minority groups. Our society still grapples with a significant gap in imagination regarding the potential impact of the arts on individuals, and public opinion tends to either underestimate or exaggerate such influence.

What resonated with me the most was Mia's revelation of how arts education could contribute to psychological healing for individuals in prison, despite prevailing societal prejudice against them. A former JIE student shared, "In this environment, people are labeled, treated suspiciously, and thought of as criminals. To believe in rehabilitation, there has to be a belief that change is possible."

Prisons are evidently detrimental to the mental health of those within them, marked by oppressive relationships and strict schedules that impede proper healing. Despite the limited counseling services offered, it is evident that very little can be done to ameliorate such a harsh environment. I appreciate Mia's sharing of how many individuals in prison found solace in her program through artistic expression. While estimating the long-term impact of the JIE program proves challenging, its short-term effects demonstrate a positive influence on individuals in prison.

Mia's project faced difficulties, given the restrictions on art materials due to the specific nature of the prison environment. Nevertheless, through her work, I witnessed the motivation of individuals in prison to create. The profound takeaway from Mia's project is the realization that we should not deprive or neglect anyone's right to art education, nor should we underestimate the transformative power of art on individuals. This underscores the paramount significance of community art, fostering connections within a larger collective that shares feelings, understands and supports each other, and can even instigate positive change.

Written by Ziying (Dorothy) Guo

0 notes

Text

"Inspired Reflections: Unveiling the Layers of Justice-in-Education"

Meiling Jiang

As the semester draws to a close, I am reflecting on the profound insights shared by Mia Ruyter, the coordinator of the Justice-in-Education Initiative (JIE), in our Arts & Community Engagement course. This journey has been a transformative exploration into the realms of community-based art engagement, with this class offering new perspectives and deepening my understanding of the issues surrounding mass incarceration.

One of the most enlightening lessons I took away from this course was the power of collective exploration. During class discussions, I gained a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of prison education. The unique pedagogical challenges of the prison environment and the intricate relationship between economic structures, racial systems, and forms of incarceration both challenge and underscore the need for social justice initiatives. Another highlight of the class was Mia's classroom sharing of collages made by students in prison. Through this classroom activity, I realised the immense potential of art as a tool for social change. Not only did the art project engage the community, but it also raised awareness of issues related to mass incarceration, reinforcing the importance of art as a catalyst for dialogue and change.

Mia Ruyter's insights into the Justice-in-Education Initiative were particularly inspiring. The initiative's mission to provide educational opportunities to those affected by the flawed justice system resonated deeply with me. It was heartening to see how art and education can converge to challenge systemic injustices. Through JIE, I discovered the power of empathy and the role education plays in breaking the cycle of incarceration.

Community-based art engagement took on a whole new meaning as I delved into the nuances of this concept throughout the semester. The connection between art and community became clearer as I witnessed the impact of our group project on the local community. Art became a bridge, transcending barriers and fostering meaningful connections. This newfound understanding has ignited a passion within me to actively contribute to the intersection of art and community engagement beyond the classroom.

In crafting this reflection, I've strived to embody the essence of our course's objectives. My perspective has been shaped by thoughtful analysis, creative exploration, and a genuine commitment to understanding the complexities of community-based art engagement. The lessons learned from my peers and the invaluable experiences gained during our group project have been pivotal in shaping my reflections.

As I share this reflection on our course blog, I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the ongoing dialogue surrounding justice, education, and community engagement. I believe that through our collective efforts, we can continue to unravel the layers of injustice and create a more inclusive and empathetic society.

Unknown. (2023). Justice Beyond Punishment.[Picture] https://www.beyondpunishment.org/.

0 notes

Text

Art as an Exit in the Age of Mass Incarceration

--- By Yitan Xu (Eden)

During our recent class session, Mia Ruyter, the coordinator of the Justice-in-Education Initiative (JIE), shared inspiring insights that continue to resonate with me. JIE aims to provide educational opportunities to those affected by the flawed justice system and involve the Columbia community in the movement to end mass incarceration. Mia shed light on the challenges and complexities involved in bringing art educational programs to incarcerated individuals, particularly those in harsh environments like the controversial Rikers Island jail. Through her presentation, she exposed us to a "secret world" where people face unimaginable sadness, trauma, and loneliness. In these places, their very existence, freedom, humanity, and dignity are under constant threat. They endure far more suffering than they deserve, as society often deems them "unworthy" and denies them access to educational pursuits.

I deeply appreciate initiatives like JIE that organize educational courses and artistic activities to help transform the lives of those impacted by incarceration. It is about more than just education; it is about nurturing the human spirit and healing the broken souls of incarcerated individuals. While it may not be a formal therapeutic intervention, it plays a crucial role in addressing the trauma and damage they have experienced.

During our discussion, we explored the question of whether incarcerated individuals would appreciate engaging in artistic activities within the confines of their detention facilities. After all, these places often foster negative feelings and a sense of not belonging. Would the incarcerated still have the desire to create art, despite the oppressive environment that treats them as criminals and restricts their freedom and connection to the outside world? Mia shared a touching story that provided a powerful answer to this question. She recounted an incident that occurred during a creative writing class she conducted within a jail or prison. Students were encouraged to express themselves through poetry, utilizing limited creative tools and materials available to them, such as paper and pens due to strict correctional policies. Mia promised to type up their handwritten poems and bring them back during her next visit.

As Mia revealed, the students in the class attached great value to her words and promises, and she was determined not to let them down. When she returned with the typed versions of their poems, the students were filled with excitement and joy upon seeing their works transformed. One woman even exclaimed, "I feel like my poem just got published!" Isn't that beautiful? Doesn't it provide a resounding answer to our previous debate on whether incarcerated individuals can still find joy and fulfillment in artistic expression within the spaces that haunt them in their nightmares?

In my reflection, I see art as a source of solace, hope, and an escape in the face of mass incarceration.

The Justice-In-Education Initiative (JIE): https://justiceineducation.columbia.edu

3 notes

·

View notes