Behind the Scenes With the Nation's Leading Gallerists

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“We’re all storytellers.” – Skoto Aghahowa, Cristin Tierney, and Tarrah Von Lintel on Their Responses to the Ever-Changing Art World

by Beatrice Crow • March, 2024

Tarrah Von Lintel, Skoto Aghahowa, and Cristin Tierney.

——————————————————————————————————

Like starting any business, opening a gallery can be daunting. For gallery owners, weathering the storms of financial crises, the ups and downs of the art market, and the rapid changes in the economic landscape since COVID-19 requires intuition, flexibility, and above all, a steadfast dedication to the mission.

While no two roads to starting a gallery are the same, Skoto Aghahowa, Cristin Tierney, and Tarrah Von Lintel each opened their respective galleries at moments of economic turmoil–Skoto Gallery and Von Lintel Gallery in the recession of the early 1990s, and Cristin Tierney after the recession in 2008. In the first-ever round-table Gallery Chat, Aghahowa, Tierney, and Von Lintel compare notes on the changes to the gallery landscape throughout the years, their advice to young dealers on navigating moments of crisis, and their paths through the art world.

What was your first job in the art world, and did it inform your career trajectory? Was there anything interesting that you learned there?

Cristin: I started in the art world at the Corcoran Museum, which no longer even exists. It was 1993. I just graduated and finished my undergraduate degree and it was the middle of the culture wars. Not long before I started there, the Corcoran canceled their Mapplethorpe exhibition under great duress. And it was complete chaos. I mean, it was a recession in the rest of the world. It was an absolute goat rodeo, but it was great if you were 22 and wanted to learn things because there was certainly a lot of opportunity. “Oh, you can type? Great. Help us with the database. Oh, you're not afraid of people? Great. We need you in this membership meeting. Do you know anything about art history? Great. Please catalog this.”

I started in the event department there and I actually began as an intern. It took about two weeks before I was hired on an hourly basis. Then I worked part of the time in events and part of the time in development and occasionally in curatorial. I saw how an institution worked; I learned what it meant to be part of a team. I also learned a lot about crisis management in my first few months working in the art world. But I think, most importantly, it really made me think about values. It really made me think a lot about why people are in this world, why do people do this? Why on earth would you stay at an institution like the Corcoran when it just seemed like the whole place was on fire?

That commitment to artists and that commitment in Washington, D.C. to freedom of speech, those were all really very present. I do think that had an outsized impact on me; it's always there in the back of my mind when I'm thinking about what artists I want to work with. It's always there when I'm making decisions.

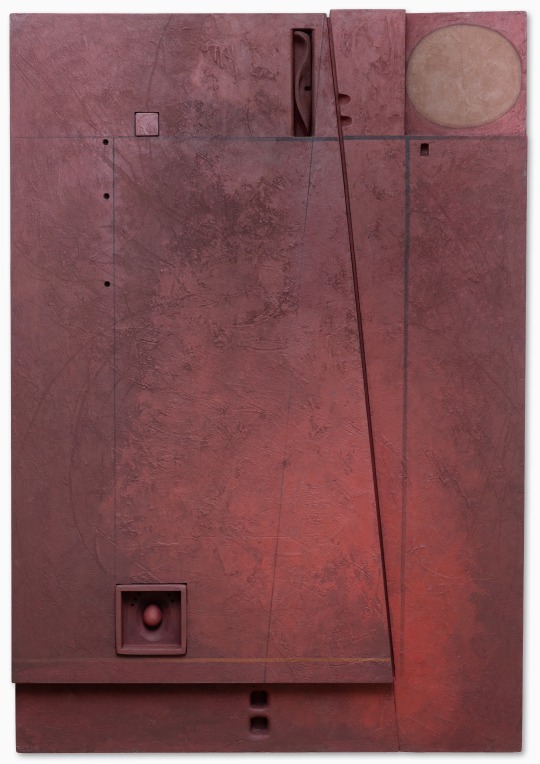

Cristin Tierney and Alois Kronschlaeger.

——————————————————————————————————

Skoto: For me, I've always strived to be independent, in a way. I have never worked in any art institution. Really, one of the things that has always motivated me was the lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the art world. So, with that in mind, I started off by doing salon shows at Salon d’Afrique, a space in Harlem hosted by Rashidah Ismaili Abubakr during the 1980s. A poet, fiction writer, and activist, she regularly organizes cultural events celebrating the Black experience that attract a diverse and conscientious audience of artists and scholars living in or passing through the city.

Then, in 1990, there was a major exhibition at The Studio Museum in Harlem titled Contemporary African Artists: Changing Traditions that brought together works by about eight or nine artists living and working in the African continent. One of the aims of the exhibition was to challenge stereotypes of the “anonymous African artist.” It was a rare treat and an eye-opening experience for me, and I could relate to the works on display. I visited the exhibition several times during its run and was fortunate to meet and interact with some of the artists, as well as experience the richness and diversity of contemporary African art on display in real-time.

Also, from 1990-1991, I lived in Paris, France, where there was a very active art scene centered around contemporary African art from the Francophone and North African countries at the time, which broadened my understanding of a larger African art scene. These experiences helped propel us to seriously consider opening a space where contemporary African art could be exhibited on a regular basis in New York City, a space where art enthusiasts and collectors could engage with contemporary African art made by contemporary artists in close and intimate proximity.

Ornette Coleman, inaugural exhibition curator on opening day at Skoto Gallery, February, 1992.

——————————————————————————————————

Tarrah: For my answer to make sense, I'm going to go back a little further. I studied finance. I was an investment banker in London working for Salomon Brothers on the trading floor. Then the Lockerbie bombing happened and the guy who sat next to me on the trading floor was in that plane and that messed me up. I decided that life could be too short, and I was going to go find a job that I loved, something that I really loved to do instead. So I quit and I made a list of all the things I liked to do and art was one of them. And art won out.

I proceeded to read every book, everything that I could possibly get my hands on, and visit every gallery and museum in Paris. I'd moved to Paris also to help my father on the side. And then I got a job at FIAC, the art fair. I absolutely loved the camaraderie of the art fairs. This was in 1990, something like that, when the galleries weren't as big. There were big galleries, but one of the booths that I helped out at was Anthony d’Offay. He was on the ground himself packing up stuff and doing things. You would not see something like that today.

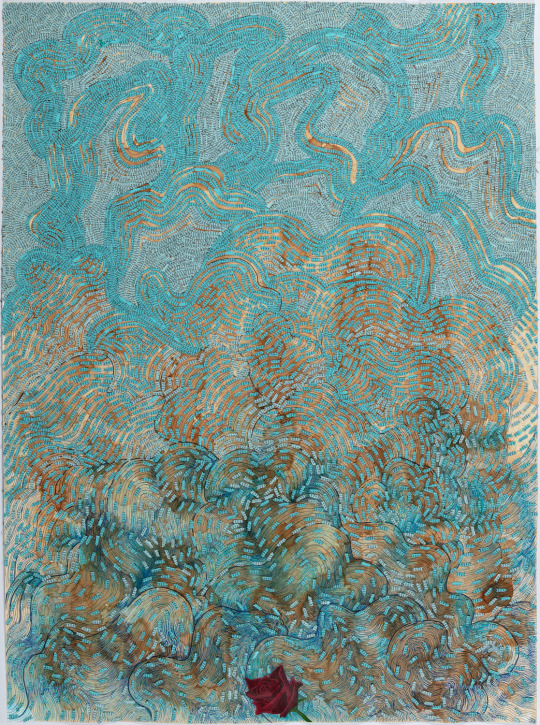

Tarrah Von Lintel and Mark Sheinkman at The Art Show, 2023.

——————————————————————————————————

Cristin: When you first started with the art fairs, did you feel like–when you looked around–the art fair was something that was growing and changing and that it was becoming a bigger part of the art world? Or not at that time? Did you see it coming, what it has become?

Tarrah: No. I mean, at the time, there was Art Basel, there was Art Cologne, FIAC, Chicago, and that was it for the big fairs. The fairs weren't as large and people would actually show their entire program, as opposed to now, [where galleries] are urged to show one artist or two artists because you don't want the booth to look like a fair within a fair, which I understand, but I also feel that's a pity because I think there are a lot of advantages if you can actually show your program if you're in a different city.

People in the art world always have these stories about when or where they were when they realized that they wanted to work in the art world forever. I'm wondering if there was a moment for each of you where it clicked into place that being in a gallery, specifically, was what you wanted to do.

Tarrah: For me, the art fairs made me want to be a part of that family. I wanted to be a part of that group. I loved every bit of it. And you have to remember, I came from investment banking, which is just a completely different environment; and then I made it happen.

Skoto: There were two landmark exhibitions in the 1980s that highlighted the lack of diversity in the art world at the time. One was Primitivism in 20th Century Art, organized by William Rubin at MoMA in New York, and the other was Magician de la Terre, which was organized by Jean Hubert Martin in Paris at the Pompidou Center.

Primitivism in 20th Century Art was notable for its lack of tangible input by artists and art historians of African descent. There was classical art from Africa made by unknown artists that were on display alongside works by modern Western artists like Picasso and Matisse, who drew upon aspects of primitive art and culture that were valorized. The Pompidou Centre exhibition, which sought to address some of the issues surrounding the exclusion of non-Western artists from the global discourse on contemporary art, was equally flawed in its selection criteria of works and artists from the non-Western world which privileged self-taught artists and the exotic over their academic-trained contemporaries.

Both exhibitions generated widespread criticism from the art community that helped to usher in an era of globalization in the art world and the quest for equity, diversity, and inclusion–which, in turn, invariably led to the formation of the gallery in 1992.

Skoto, Okwui Enwezor and Isaach de Bankolé, 1994 at reception for the Cote de Ivoire-born actor Bankolé.

——————————————————————————————————

Cristin: I mean, I knew from the time I was in college, and went to Paris, that I wanted to be in the art world. But I did not think that I wanted to own a gallery at all, not until I had been in this world for quite some time. It was during the financial crisis, really, in 2008 when everything sort of stopped short. The building in Chelsea that my office was in was full of art-adjacent businesses. There was a framer, photographers, and an oil paint distributor, and everybody was gone in six months [after the economy crashed].

The whole building was empty and my landlord was literally wandering the halls one day, and we got talking about all the empty spaces and all the smaller galleries that were gone. And he said, “why don't you curate some shows?” And we did. It was all working with living artists in these empty spaces. He gave me absolutely enormous spaces for free and said, “if you sell anything, split the profits,” which, it was 2009, so there were no profits, but it was a great experience and it was so much fun. I loved the strategic thinking and I loved the problem-solving.

I actually really loved working with artists. I realized that one of the reasons I never thought I would be a good gallerist is that I never thought I could say no to artists, and I never thought I could be tough enough to toe the line between “I know what you want to do,” and “here's what we should do.” I mean, I frankly think I'm still pretty bad at that and I'm pretty indulgent on the artist side of things. But I love artists and I think artists are magic people who deserve special status in our world. That's kind of where the switch happened. I decided I should open up a space and then a real estate agent called and said, “I know a great space for you.” I went and I saw the space and I said, “Yes, I have to have it.” And that's how it happened. I mean, it was really quite lucky in that way.

It's interesting to me that all three of you opened galleries in financially tough moments, right? Cristin, in the crash around 2008, and Tarrah, Skoto, I think you both have recently celebrated the 30th anniversaries of your galleries, so you're opening them in the early nineties, in a kind of economically fraught moment. And of course, may we never repeat any of those moments, but Tarrah and Skoto, do either of you feel like there was an opportunity in that moment because we were in a recession?

Tarrah: I think for me what was important when I started in the art world [was that] things were already going badly. So I was never spoiled in the way that many other gallerists were. I didn't pick up any bad habits, which I think is something that worked in my favor when I opened the gallery because I knew it was tough. I knew exactly what I was getting into. So I think, in a way, that's a much better way to start than if things are going gangbusters and then you head into a big recession. I think just keeping track of money is an important part.

Cristin: There's no indulgence. You must meet that budget because there's no help coming if you don't.

Skoto: The economic downturn at that time [actually] played to our advantage, because the first place we got was on Prince Street. It was a street-level space with a beautiful garden in the back.

Prince Street, east of Broadway and close to the Bowery, was a very good location. The Museum for African Art was a mere 10-minute walk from us, and SoHo was then the hub of the New York art scene. There was no audience for contemporary African art in New York when we opened the gallery in February 1992, and almost no one knew that Africa even had something called “contemporary African culture.” We literally had to invent an audience for our program.

The garden at the back of the gallery became the site for very stimulating, impromptu conversations among African and African Diaspora artists, writers, and scholars who were focused on the progression of modern and contemporary African art. The push for the publication of the influential NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art in 1994 by Okwui Enwezor came out of such conversations.

How did you start to choose who you were going to show and begin those relationships when you were first starting a space and first going out on a limb and opening this space? What was that process like?

Skoto: Our first exhibition at the gallery was curated by the renowned American jazz luminary Ornette Coleman. It was a group show of African artists that included Bruce Onobrakpeya, Saheed Pratt, Obiora Anidi, and Ben Ajaero, among others. This was followed by several solo exhibitions of African artists as part of our “Art in Africa” exhibition series. Soon enough, word got around town that something different was happening on Prince Street. Many artists were interested in our program and wanted to work with us.

Left to right: Mel Edwards, Skoto Aghahowa, Stephen Procuniar, Richard Hunt, Alix du Serech and David Procuniar at the reception for Richard Hunt-Stephen Procuniar exhibition in 2007.

——————————————————————————————————

Cristin: It's funny, people are like, “how do you decide what artists you want to work with?” Well, at the beginning, you're lucky if any of them will agree to work with you. [Jokingly] “Hi, I have no track record. I've never really done this before, but I have a big building in Chelsea; would you like to show some work? I don't actually know if I can sell any of it, but maybe, I mean, we'll see how it goes. Would you like to join?”

That’s sort of how it starts. [Then] one artist leads to another artist leads to another artist. There are lots of artists and artworks that I see at art fairs or museums, and I track those people down or have conversations with them, but I do really think that part of the way that your program grows is through the artist themselves. You're just there along for the ride and hoping to occasionally have semi-intelligent input once in a while.

Cristin, do you feel like when you're thinking about an artist and your relationship with the artist in terms of their career, do you want to let it unfold totally organically, or do you see your role there as along for the ride with the artists? Do you feel like you have a position to shape it in some way or to provide feedback that will inform their trajectory?

Cristin: I think it's a partnership. As far as the content of the art or what artists make or what they do as artists, that's entirely up to them. I love to do studio visits and I love to talk about the work, and if an artist asks me, “what do you think about this?” Or “what does it make you think of?” I am a hundred percent there for those conversations. I mean, it's one of the great gifts in this world as far as I'm concerned; but when it comes to the rest of it, when it comes to conversations with museums, conversations with collectors, what are we going to show and how are we going to show it? How are we going to contextualize it? All of those things, that's a much bigger conversation. I would say that I am a little bit more hands-on with that.

It's ultimately up to the artist, but I don't think that anybody's career in 2023 unfolds organically. I mean, things can take unexpected twists and turns. Hopefully there are great twists and turns, but I think it's really important, again, as part of that partnership, if you're in an art fair and a curator that you weren't expecting walks into that booth, that part's organic, but getting that curator then into the artist's studio and signed up to do an exhibition for that artist and everything that comes along with it, that's not organic, that's my job. That's on me.

Installation view of "Mary Lucier: Leaving Earth" (Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York, January 19 - March 2, 2024). Photo by Adam Reich.

——————————————————————————————————

Tarrah, you've talked about the difference between working with younger artists and mid-career artists and how that relationship is very different at a younger stage. Could you talk a little bit about that in your program?

Tarrah: I think when you start working with an artist, you have to get to a point with that artist where there's trust, and sometimes that comes faster, and sometimes that takes a longer period of time. But once there is that trust, then I find I have yet to meet an artist who doesn't value an honest opinion. One of the problems they face is if they show their artwork to friends and family, the typical response is, “Wow, that's fantastic!” but that's really not helpful. When I critique or give my opinion, I make sure that the artist understands that I'm coming from a dealer's point of view and I'm bringing some very practical ideas to the table. It can be as simple as a horizontal format versus a vertical format, or sizes. I think that's actually one of the things that artists value the most is honest feedback, but I would never tell them what to paint.

Skoto: Some of the artists we work with at the gallery live and work outside of the US, in Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean. Some of them already have very strong reputations back home and are seasoned artists, while others are relatively young. For most of these artists, showing at the gallery was probably their first exhibition in a New York City gallery, where their works might be unfamiliar to the audience.

Artists want a direct and honest opinion from you as a gallerist, and you have to be able to convince them to be patient while insisting on the consistency and quality of the artist’s work over a long period. I still remember the first time we showed works by the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui at the gallery in the 1990s. There was practically no audience for his work at that time. Today he is among the most highly recognized artists in the world. It can take time for the audience to catch up to the work of an artist.

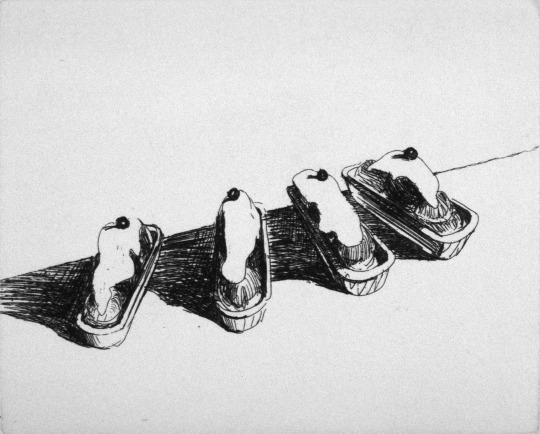

Aimé Mpane, "Bach to Congo," installation view, 2006-2007. Courtesy Skoto Gallery.

——————————————————————————————————

Tarrah: If I may just add in my case, because I didn't go the typical trajectory and I didn't study art history, when I was starting to get into the art world, I made it a point to become friends with artists. And even in Paris, while I was working for other galleries and I became the director of Thaddeus Ropac, I still kept all these relationships going. When I left and opened my own gallery, the first people I went to were my best friends. I had met David Row, so I showed David Row, and then through David Row, I met this group of New York artists in the New York School of Abstraction, Stephen Ellis and John Zinsser, and then Jamie Nares and on and on and on.

Cristin: It's true. It was Joe Fig, who had been my friend for years, who convinced me that I should open up a gallery. It's totally the artist's fault.

Tarrah: The reason why I opened a gallery in New York is because my artists, David Row and Stephen Ellis and John Zinsser and Lydia Dona got together and asked and said, “have you ever thought about opening a gallery in New York?” And once I had that bug in my head, I couldn't get rid of it, so I made it happen.

Tarrah Von Lintel at The Art Show 2022 with fashion icons Robert Verdi and Jerome LaMaar.

——————————————————————————————————

If you could all share what your advice would be to an aspiring dealer in 2023, what would you say?

Skoto: I tell them to stay focused. Don't look for that quick, short-term return. It is long-term, strategic planning, so stay focused. I always tell them to be deliberate in their decision-making process and be confident in their decisions. You must learn to make up your own “Top Ten.” Don’t let anybody impose theirs on you. Don't listen to what anybody's telling you in terms of what is trendy and what is not trendy. Just believe in yourself and go with it. Be honest and deal with what it is. Do what is right. Do what is right by you and what is right by the artist.

Cristin: Something that I always say to people is never forget who your first and most important clients are. It's the artists. You have, of course, also clients who are acquiring their work and supporting their work. But you should always think of your artists as your clients and do for them just the same as you would do for the collectors and the curators and everyone else. You represent them. You should always have that set of clients’ best interests at heart, first and foremost.

The second thing is something that somebody told me; Charlie Moffett Sr. and I had a conversation years ago. We were talking about an older generation of dealers and how they did what they did. And essentially, to him, the common thread was that their client bases were not necessarily broad, they were deep. Those people, if you treat them right, if you invest in them the way that they're investing in you, intellectually and emotionally, not just financially, they're going to support you.

I think that's a really important thing for the long-term success of a gallery. You want to focus on having relationships that are deep rather than broad, because that broader audience or market might be gone tomorrow. They might get preoccupied with NFTs, or if the stock market plunges, they're out of there. But the relationships that run deep, the relationships that are formed with people who believe in the same sorts of artists and artworks and the same sorts of values that you believe in, they're with you for the long run, and that's the depth and that's what you need to stay alive for decades, rather than years or months.

Cristin Tierney Gallery artists on a Zoom call with gallery staff during the Covid-19 lockdown.

——————————————————————————————————

Tarrah: I have two things to say about that. I do think that the artist is your biggest asset, so treating the artists with respect and paying them is really important. I believe that I have a very good reputation in dealing with artists. I'm paying them. And so when I approach a new artist, they're going to ask their friends, and then their friends say, “Well, we've never had a problem.” I think that's really important.

Cristin, my experience with the deep versus broad has changed. It used to be deep, but since COVID-19, it has moved to broad. Most of the people who were the deep collectors in my case, stopped in COVID.

They didn't like the digital art fairs or the digital viewing rooms, and the fact that the social part of the art market was completely removed, they lost their interest because they didn't need more art. I mean, these people have so much art that they have warehouses full of it. So I've actually been fighting with this problem–I had deep relationships, but I'm getting calls from them now saying, “I bought this from you 29 years ago. What can we do with it?” So then you try to either resell it or you try to have it donated to a museum, which makes everyone happy, but that's a tremendous amount of work for no money.

Cristin: Did the heavy emphasis on digital outreach broaden your client base? It did somewhat for us but I didn't find that it was a huge amount the way that you read in some of the publications for us.

Tarrah: No, I can't say that that's the case. In terms of broadening, I don't have this core, really healthy, strong core group of collectors anymore. I now am selling just to a wider audience, but not as deeply. Not as much. I mean, I wish that would change, but the younger generations, they're not “the crazy collector.” For me, a collector is somebody who keeps buying even though they can't hang anything anymore. I find that a lot of the buying that's happening now is either for investment purposes or for the piece above the couch.

Cristin: Yeah, it's not patronage in the same sense either. It's not about supporting an artist, really.

Tarrah: No.

Cristin: Yeah, there's a lot less of that, sadly, I think. Skoto, what's your experience been?

Skoto: Unfortunately, art has become something of an investment rather than just buying work because you like it, because it's something that you want to live with for a long, long time. My experience has been a mixed bag. Thankfully, you have some collectors who still buy work because they want to support what you're doing and because they like what you're showing.

At the same time, you also have collectors who come in and sporadically buy work, because they figure it is something they can flip in a few years and make a fortune out of it, which is unfortunate because it just kills the spirit for both the artist and the dealer. But that's the world we live in now.

How do you feel like your conversations with your clients have changed as the digital landscape has changed over the course of the last three years?

Tarrah: I mean, one of the big problems now is getting people to actually look at work in person. The difference between a two by three inch .jpeg and a work of art that's six feet by eight feet, that doesn't translate. I keep thinking that I should rename the gallery to “Does Not Reproduce.”

Things may be larger in person than they appear.

Tarrah: Well, yeah. I actually had a show during COVID, a group show that I called Does Not Reproduce, and it's all work that just did not work on a screen–size, texture, any kind of depth didn’t show.

I believe that a good artwork is one that grows with you over time, so you have a long dialogue with it. That's what makes it really good. But that's exactly the opposite of what's happening at the moment. People are looking at, myself included, thousands of images every day. When I started, there were five ways to see art. You could either go to a gallery, go to a museum, buy a book, buy a magazine, or make the art yourself. But those were your choices.

Skoto: Yeah. Well, slides were also available at that time, too.

Cristin: And transparencies! But I feel like I have to agree. It's hard to get people in front of the work. Once they're there, though, the amount of time they're willing to spend talking about the work is still substantial. And I don't think it's just an older generation. I do think that there are a lot of younger people who come to galleries wanting to have those conversations, wanting to get away from screens and TikTok and attention-distorting social media programming and stuff like that.

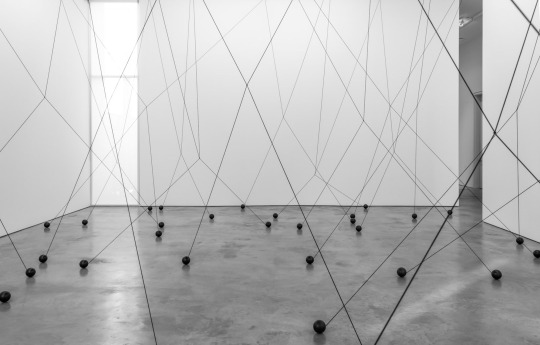

Installation view of "Alois Kronschlaeger: Allotropisms" (Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York, January 13 - February 19, 2011). Photo by Marc Lins.

——————————————————————————————————

Tarrah: I mean, I do feel that COVID had one positive outcome, because in 2019, things were very much going towards social media and [as a result] less people were coming to galleries. Because of COVID, everyone looked at their phones so much that [they’re all] sick of it now. So now when they come to the gallery, they don't lead with the phone anymore, which, in 2019, they were looking at their phone while walking through the gallery. I feel like people have put away their phones when they are now experiencing something, which I'm very happy about.

Skoto: One thing we've done after COVID is to have a longer duration for our exhibitions. Prior to COVID, most exhibitions were usually four weeks, five weeks. Now, you find that galleries are more willing to extend their shows. I remember [in March of 2020], we just opened a show when COVID came along. We had to keep the show up for nearly a year, which was a smart thing to do because we ended up almost selling the whole show by the end of that year. In a way, I think it has allowed us to readjust and to make changes to things that we used to do. Another way to get around this short attention span is to figure out how to join them. You should have a stronger presence online. Of course, because we are all saturated with images and media, very few people respond.

What advice do you have for people who are aspiring collectors who might come into your gallery?

Skoto: Make them feel comfortable and provide them with as much information as possible when they come to the gallery. Taking that bold step to come to the gallery, that's something positive. You should always try to help them understand and engage deeper with the work you have on display. Follow up and communicate with them.

So you really encourage them to ask questions. That for you is a vital part of building that new relationship with the collector.

Skoto: Oh, yeah. You should always strive to get their opinion about the work they are looking at or interested in. Let them tell you in their own words what they think about the work or an artist.

Cristin: What I always say to our younger groups is that, first of all, you should never be afraid to ask somebody to come talk to you about the work in a gallery. But when you’re there with somebody who knows so much more than you do about the work–and you are kind of nervous and it's intimidating to even think about questions to ask–one question that I always suggest is, “tell me something about the work that I can't read in your press release. Give me a way into the work right here, right now, that goes beyond what I can read on my phone.” It's a powerful, useful question because that person in front of you probably has so much information about this exhibition and about the artist's work.

It also doesn't require you to have a tremendous amount of information, but it does enable you to get to a point where it's not just about, like Skoto said, what they're reading on their phones or what they can find online. What's here that I can't see and understand any other way? It's a pretty simple thing, but it's also kind of empowering, right?

Tarrah: I find myself trying to get them to have a dialogue with whatever it is that we're looking at. I know the things that are important that I can draw people's attention to. I'm sort of becoming the teacher in how to look at this, how to experience this, just to involve them, to pull them into the story. And then of course, by telling stories, the next time they see something, they become the teacher, which makes them feel good. It's like when you see people recognize an artist at an art fair, they're the happiest people.

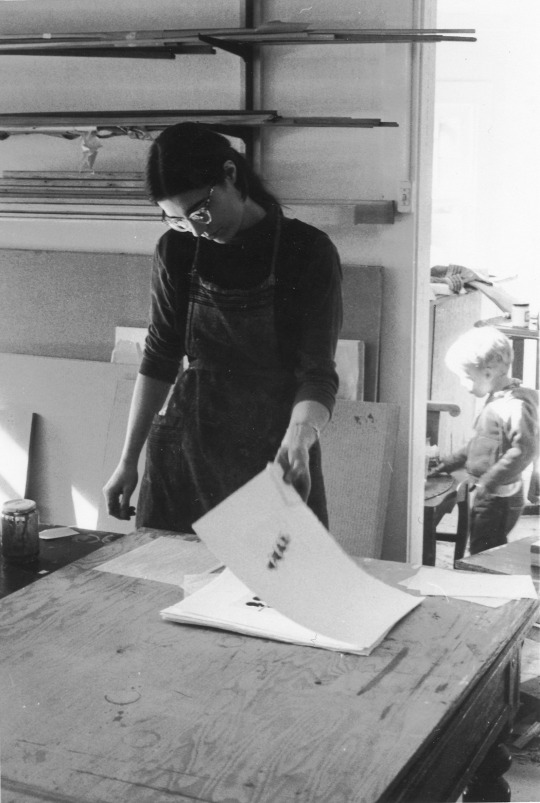

Tarrah von Lintel with the artist Miles Regis during his last show at the gallery, titled ‘Better Days Ahead’

——————————————————————————————————

Cristin: Totally true. Totally true. I actually remember when my husband and I were really young and we didn't really have very much money. We started buying art and we bought this work that we hung in our living room area of our first home together. He never said much about the art, but his friend from high school was there one day and started asking him questions about the art; and as you said, Tarrah, he knew all the stories. He knew all the details because he listened to me so many times and talked to the artist so many times and he just could not tell his friend enough information about this artwork. I'm sure his friend was like, “Okay, that's enough!” Again, it's like you said, there's something very empowering about that, about recognizing and knowing like, “Hey, I know something about this.”

Tarrah: We're all storytellers.

Cristin: Question for the group: why did you guys want to join the Art Dealers Association of America? [Says Cristin, the head of the Membership Committee.]

Tarrah: Good question. I mean, frankly, a big draw I think is The Art Show. The Park Avenue Armory is one of the nicest places to see art in, because of the location and the size of it.

Cristin: I agree.

Tarrah: And now that I'm in it, what I truly love about this organization is the professional way that everything about it is handled. It's fantastic. It doesn't happen often enough.

We aim to please, Tarrah!

Skoto: I think the recognition by your peers that what you’re doing is relevant… that's a big plus. To be able to, from time to time, stay in touch with your peers who are doing the same thing, I think that's a big motivation to join the ADAA.

Cristin: It's like getting an award from the Screen Actors Guild, because the Screen Actors Guild is the award that your peers give to you.

I have to agree that the peer recognition is immensely gratifying. And [so is] the sense of community that you have as part of the organization. I think especially we're talking about a world that's increasingly fragmented, and the distance that we all feel between our clients and our colleagues, and what living on a world of screens has done to us, and the ADAA is a kind of remarkable antidote to that for all of us, right?

——————————————————————————————————

Skoto Aghahowa is the founder of Skoto Gallery, located in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York. Aghahowa founded Skoto Gallery in 1992 as a space where works by African artists are exhibited within the context of a diverse audience.

Cristin Tierney is the owner of Cristin Tierney in New York. After years as an art advisor, Tierney opened her eponymous gallery in Chelsea in 2010. In 2019, the gallery moved to the Lower East Side.

Tarrah von Lintel is the founder of Von Lintel Gallery. After years in Paris at Galerie Claire Burrus and Thaddeus Ropac, Von Lintel opened her own gallery in Munich in 1993. The gallery moved to Chelsea in 1999, then to Los Angeles in 2014.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Remember That What We Do is Bigger Than Ourselves" - Jessica Silverman on Building Relationships, Collaboration, and Strategically Navigating the Art World

by Kim Cabrera • April, 2022

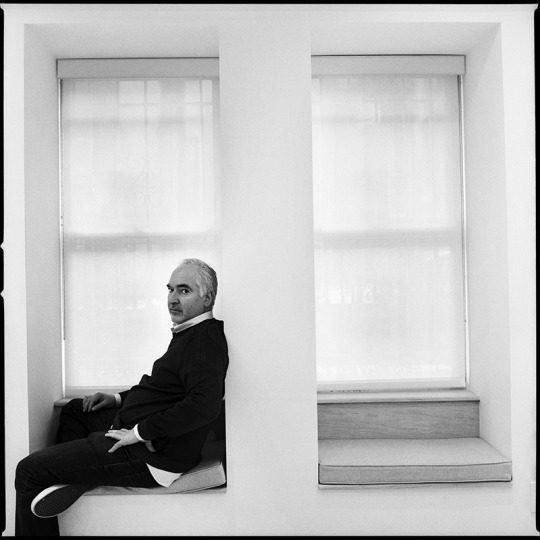

Jessica Silverman, photo by Stan Olszewski / SOSKI Photo.

——————————————————————————————-

Jessica Silverman has always found a variety of ways to utilize her curatorial eye, beginning with mounting shows in a small local vitrine and a basement project space while still in school. In 2008, after graduating from California College of the Arts with an MA in Curatorial Studies, Jessica opened her first official gallery on San Francisco’s Sutter Street. Since then, she has built a roster of local and international artists, created strong relationships with curators and collectors in San Francisco and beyond, and most recently, moved into a new, expanded space in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

We sat down with Jessica to discuss, among other things, her entry into the art world, the San Francisco art scene, and the various changes her gallery and the art world at large has faced over the years.

Installation view, Woody De Othello: Looking In, 2021, photo by Phillip Maisel.

——————————————————————————————-

When was the first moment you became interested in the visual arts; was there one singular “aha” moment or did that interest evolve over time?

I think it’s fairly public knowledge, but I grew up around my grandparents who collected art — Fluxus in particular — and I remember distinct moments when I knew I loved art and was interested in who the artist was and why the collector collected.

One of those moments was when I met Yoko Ono. I remember thinking, “She’s so cool. Artists are cool.” And also really unique and individual. When I grew up in Michigan, I went to this college preparatory school and I was kind of an outsider since I was one of the few people interested in the art department, so meeting an artist who was so much herself was appealing to me, and I thought “this is a world I want to be part of.”

You had originally started out as an artist yourself?

Yes, very early on. I spent a lot of time in the darkroom at my high school and then I went to Otis College. About a year into Otis College, it was very, very clear that I wasn’t going to be an artist. It was important for me to go through that, and then have my teacher say, “I think you’re really more of a curator, your interests align more with curatorial work.” From there, I started investigating that as a path forward for myself, and wound up at California College of the Arts for curatorial practice.

In relation to your grandparents’ collection — did you go with them to visit artists, or to studios or to galleries, or did you just experience the art through the physical collection?

I went to Washington, D.C. and New York with them a few times and we visited museums and galleries. We used to go to Max Protetch’s gallery, because my grandfather and he were good friends. I also saw the works at the Detroit Institute of Arts, at their house, and within their private collection stored in downtown Detroit.

Would you say that the experience seeing art with your grandparents helped shape some of your ideas about how to view art, or the critical lens through which to view it?

I learned the importance of “need to have and can’t live without.” The empathy that I try to bring to my relationships with collectors was also informed by my relationship with my grandparents.

Initially, in dealing with my grandparents, I didn’t think a lot about the curatorial until much later when I was already on that path. They had always been very engaged with everything that Jon Hendricks did for them. Jon was guiding how they built their collection, and creating the systems to organize it. His use of systems and categories engaged me further in the curatorial.

Could you tell us a little more about that project space you opened in a basement in your early days, how that came to be?

Even before I had my space, I had a little vitrine that was outside a building —the kind you put notices in. I rented one in San Francisco and put on little shows until I had a break-in. Then I was done doing that.

After, I opened my basement space, which was not a formal gallery, but a project space I ran in 2006 during grad school. In 2007 I graduated, and in 2008 I moved to Sutter Street, where I started to formalize the gallery and think about what it meant to represent an artist.

Who were some of the gallery’s first artists, and how did you go about making the decision to start working with them in a formal way?

I grew up in Michigan with my friend Job Piston, who is a photographer. He was graduating from CCA in San Francisco, and he did a show with me. I asked him to organize an exhibition of artists that he was interested in, or learned from, so we had Larry Sultan and Tammy Rae Carland. Tammy Rae joined the roster and her show was the first we did in our Sutter Street space. She’s now the provost at CCA, but still an important part of our program.

When you were starting out and you were younger, did you find that you had to convince people to buy from you, or convince artists to sign on?

Totally. I did feel like I had to convince people. I didn’t really mind until it became frustrating. I didn’t want to go through my grandparents, and didn’t want what I did to be determined by who they knew, so I was pretty stubborn about going about it my own way.

I had tons of relationships that didn’t work, where I’d put an artist in a group show and they would decide that they wanted to wait for someone bigger — and, not to toot my own horn, but oftentimes those artists never found anyone bigger. For me this is very much a relationship world. When people aren’t willing to invest in the relationship in the same way as I am, it invariably doesn’t work. Maybe I was initially upset or irritated, but long term I’ve never felt resentful about a relationship that didn’t work out.

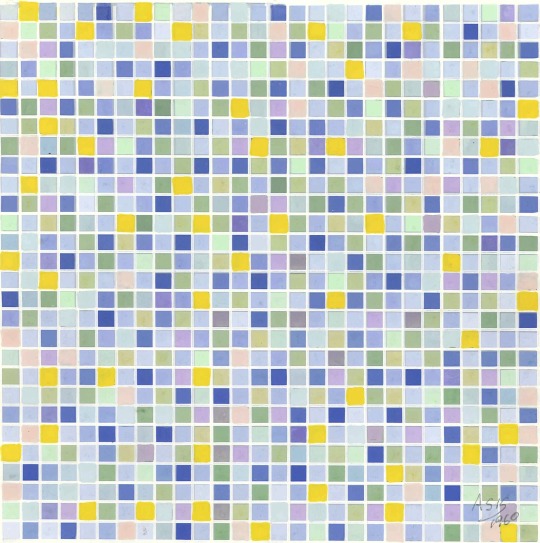

Installation view, Hayal Pozanti: Lingering, 2021, photo by Phillip Maisel.

——————————————————————————————-

When you first started the gallery, did you have a clear vision of what you wanted the program to be, or were you a little more organic about that process, and let the artists you were interested in drive that?

I definitely thought I had a clear vision, but in retrospect, I don’t think I did — I was young and figuring it out. I would say that something that’s always been important to me is the relationship between the conceptual rigor of a practice and the visual results. I’m very interested in the way something is made, and the nature of how the artist got there.

Did you find that when you were talking with artists, because you originally came from that creative background, even if you didn’t necessarily spend a lot of time doing that, that they opened up to you in a way that maybe they wouldn’t necessarily have?

Yeah, maybe. I think I’ve always had a lot of empathy for artists, because I had a studio practice for some time and try to remember how daunting it can be to be vulnerable, transparent, and raw with visitors.

You talked about a sense of empathy for collectors, and being empathetic towards who the collector is and what their needs are. Are there certain things you always like to make sure of, certain ways the collector is taken care of beyond the traditional transaction itself?

Yes. I’m constantly reminding my colleagues about the relationship. Many of our collectors date back like 10 years of working with me, and it’s one of the things that people who are new to the gallery realize.

We try to be a gallery that really fosters long-term relationships with our artists, our collectors, and the curators we collaborate with. I see no reason for a collector relationship to go sour because of miscommunication, so we try hard to be as communicative, transparent, and helpful with collectors as possible to achieve what they need.

Someone asked me the other day, “What do you love to do most?” I said, “I love selling art.” Not in a transactional way, but in the sense that I sold an artwork to someone that they’re excited about, and when they get to meet the artist, they get to be so happy that they bought this artist’s work and they’re supporting it. I just love watching that play out.

Exterior of Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, photo by Henrik Kam.

——————————————————————————————-

You recently moved to your new space in Chinatown. When is the moment you knew that shift needed to occur? Again, was there one moment or did you kind of come to the realization over time?

I found the new space in November of 2019 and in January 2020 I signed the lease. We had been outgrowing the gallery space for some time. Since 2019, I knew I wanted to move, especially in terms of where the staff was sitting and the overflow in the storage room.

A lot of your artists haven’t had a chance to have their show in the new space, but as you start to learn the bones of the space, the way the light is different at different times of day, do you share that with them? Or do you let them discover that on their own?

Ideally anyone who’s having a show comes and sees the space before. For Hayal Pozanti’s show in January 2022, that [didn’t] happen, but fortunately for us she’s a painter so it [felt] fairly easy to strategize.

We’re talking to Martha Friedman about her [forthcoming] show. I told her she might want to visit because she would like to show these new lightboxes she’s making, so we’re trying to figure out — how much light will bleed into the space? Is there anything we need to do in advance to ensure that the works will look like how she envisions it?

Martha Friedman, Nerve Language 8, 2020, photo by Kristine Eudey.

——————————————————————————————-

What role did the neighborhood itself play in the move?

I was very interested in being part of a neighborhood that had a strong sense of self. And I love the connections I’ve made here — everything from the foot police who walk around and constantly make sure people are safe, to the chocolate place next door who we send visitors to and vice versa.

Looking at the art community as a whole within San Francisco and viewing that in contrast to, for instance, New York or LA, what would you say are some of the best assets that the San Francisco gallery scene has that those other two large cities don’t?

I think it’s a good question. I sometimes feel like I’m a little bit on an island here. My biggest anxiety is that San Francisco is read as a local and provincial art scene, but I don’t feel like it is or at least, that’s not my relationship to it.

One of the nice things about San Francisco is how close and friendly the gallery scene is. For instance, after I speak to you I have to call Claudia Altman-Siegel, who wants to ask something. Jeffery Fraenkel is one my closest friends, and Tony Meier and I share an accountant who he graciously introduced me to. I took John Berggruen to lunch the other day. That’s kind of the scene.

And the museums — Claudia Schmuckli is a really close friend, Jenny Gheith and I share the same birthday and get together frequently. I'm very close to Ali Gass, who’s starting the ICA SF, and Susan Sayre Batton, at the San José Museum. I consider some of them as my best friends.

And did these relationships factor in to the project that you all created, the 8-bridges platform?

A lot of that came out of conversations a smaller group of us had. We thought — ok, we’re pretty good at getting out-of-towners into the gallery when they visit, but what if no one comes into town? How do we transact, what does that look like? Is there anything we can do to spread the word about what is happening in San Francisco? And that’s where that came from.

As the world re-opens, we’ve been caught in the middle of transition. We’ve all gotten pretty busy and we’re trying to figure out what 8-bridges looks like when things progress.

Speaking of reopening, and the idea that you’re going to art fairs and other places and the international aspect is starting to open up again, did you find, when you first opened the gallery, that there was a receptive audience in the Bay Area to your international artists, or was there a lot of teaching and education your clients in terms of them starting to build collections?

That’s a good question. There are collectors that I almost feel like I advise — we talk a lot about what they’re looking at and where they want to put their energy. I’ve actually hopped in the car and driven around to look at art with those collectors — it’s more educational.

But there is a pretty prolific collection of advisors here and I would say that the advisors do a really good job of ensuring that collectors are knowledgeable and expansive.

Sadie Barnette, Family Tree, 2021, photo by John Wilson White.

——————————————————————————————-

In the 15 years since you began — for now, let’s leave the last 18 months out of it — the art world has changed massively. How have you had to adapt the gallery to those changes, be they the speed at which the art world works, or the new digital landscape?

It’s so funny because I think a lot has changed, but I also think in some ways, very little has changed. We still schlep things around the world and show them to people. I guess now there’s a little more done on the phone, and so there’s a little less schlepping in advance of the commitments, and obviously digital platforms have allowed for online sales to become achievable.

There’s still not as much collaboration amongst dealers as I would like to see. I think that institutions still have a hard time getting budgets to buy art. But on the positive side, I think that because of the internet the world has gotten a little bit smaller and therefore artists — like for instance, those we represent — get to be well-known more quickly, from a curatorial point of view.

Do you find that there’s lots of talk now about who the new, young collectors are going to be? Certainly that comes up around tech and art and NFTs and the like. Have you found that there’s a consistent kind of series of traits with a younger generation of collectors you’re engaging with, or is it that everybody’s very different and unique in their own right?

I think everyone’s pretty different and unique in their own right. One of the things I’d say is that a lot of the collectors that we deal with are fairly eccentric and don’t just collect one thing. I just had a call this morning with a collector who asked me if I’d ever come across an artist called A.Y. Jackson. He’s a Canadian painter who died in the ‘70s. [The collector] is Canadian, and really connected to the landscapes he painted.

People are very individual here, especially if they don’t work with an advisor. I find that the collectors are not really following “what’s hot,” which is refreshing.

Often in NYC, back in the day, collectors would inherit the board seat at the Met or the MoMA from their parents and so it stayed in a very siloed lane, but would you say that in fact, collectors are a broader, more diverse range of people than what we experienced in the art world in the earlier days of your career?

In some ways. I tend to be drawn to collectors who march to their own beat, kind of like I do. Over time, for me, I’ve been able to weed people out quickly. In the older days, I just sold things to those who wanted to buy. Now, I place things.

And speaking of young collectors just getting started, what would you give as advice for someone who’s never bought before or is just dipping their toe?

My advice is to look at as much as possible. Finding a way to trust your instincts, which is kind of how I operate, is the best path forward.

Installation view, Woody De Othello: Looking In, 2021, photo by Phillip Maisel.

——————————————————————————————-

You’ve talked previously about discussing with an artist when you might raise prices as their career moves forward, and one of the things you encourage is a sense of patience about that process. Can you talk more about how you go about making that decision with the artist?

I have this anxiety that once you go up, it’s hard to come down. We try to raise prices in a very restrained and thoughtful manner. A good instance of raising prices is an artist having a museum show, that would give us the credibility, I suppose, to raise prices 10–20% from where they’re at.

But we try not to be overly excitable. Woody De Othello— he’s 30 and still a young guy, but the demand for his work is tremendously strong. We could be selling things for far more than we do, but that doesn’t really benefit him in the long term. We’re interested in helping shape a long, stable career, and not what’s right in front of us. We try to be intelligent about the ways we build artist pricing structures.

Would you say there’s a foundational strategy when you start working with a young artist, that there’s certain things you, or they, need to do to help build the seriousness of their place within the art market?

Well, I think it takes both parties. Sadie Barnette is a great example. She works super hard and is really strategic, smart, and connected. She nurtures those connections, she thinks deliberately about the placement of her work, like we do, and we’re able to continuously bring in important voices to support the practice together.

We try to balance our time between strategically placing things with private clients who are on museum boards in order to sell things to museums down the road. We found that museums often don’t have budgets to buy what they want themselves, so building the collector relationship for the artist is important to ensure that the museums can find buyers for the works they want to bring into the collection. We do a lot of matchmaking.

Sadie Barnette, Home Good: Couch II, 2019, photo by John Wilson White.

——————————————————————————————-

As you’re talking about the pricing of artists’ works — are there times where you have to play a restraining role, be the patient one, because you see this long game ahead of you that maybe an artist who’s starting out isn’t really aware of?

I have to say, artists are pretty trusting so we don’t get a ton of pushback on things. When we’re like “Hey, let’s wait and see what happens,” or “We’re not going to offer this now, we’re going to save it for X,” our artists support us, thankfully. Otherwise, it would be challenging. But it doesn’t mean it’s not hard on our part.

We have another question for you that’s kind of unique to your position here at the ADAA. You’ve been an amazing part of the ADAA Membership Committee and I’m wondering, for you, what was meaningful about becoming an ADAA member?

Well, I talked about how collaboration is something that’s really important to me. The ADAA really nurtures that, encourages it, and kind of insists on it; that is a really appealing component of what the ADAA brings to a gallery who has the option to be involved.

The Art Show is one of many collectors’ favorite fairs to go to because it’s more like an exhibition; it’s so deeply curated and considered, and the experience of that week is a really cohesive one. People come back day after day to experience it, repeatedly.

The Art Show 2021, photo by Scott Rudd Productions.

——————————————————————————————-

When we originally asked you about how things have shifted in the last 15 years, we said let’s leave out the last 18 months. But now, let’s return to that period. Obviously, we are still processing the pandemic, but are there a couple things that you’ve learned in the last 18 months that have either surprised you about the market, or your business in particular?

The market’s been kind of insane. It’s been a bananas year in terms of business. There are supply chain issues across all parties — galleries, artists, construction workers — involved.

Our collectors, early on in COVID, stepped up and bought art from us even when they had no idea, like all of us, what was going to happen.

I would also say, with the onset of NFTs and cryptocurrency, we’re seeing an influx of younger voices — they’re not all buying great contemporary art yet, but they are coming to the market.

There was a lot of talk amongst our members, as well as the press, asking, “Is this the end of the physical gallery space? Who needs a physical gallery space if this whole digital online presence works out?” Would you say the last 18 months have proven that we still need the physical interaction with the work?

I do. Sarah [Thornton], my partner, has written a lot about this. In the past, there was this thought that tech people would like digital works, but actually that’s not really true, because they are at computers all day.

It seems like tech people like mediums like sculpture because of the reassurance and enjoyment of being a body in space and looking at something physical in relationship to themselves.

Is there anything else you wanted to make a point of mentioning or any other advice for young dealers or collectors you think we should impart?

I would say, remember that what we do is bigger than ourselves. Do things for the right reasons and choose collaboration rather than thinking you can do it yourself. That has always been the best advice I’ve given myself in order to pursue success.

——————————————————————————————-

Photograph of Jessica Silverman courtesy Jessica Silverman, San Francisco. All gallery and artwork images courtesy the artists and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“People Realized the Need to Make Connections Along the Whole Spectrum of Art History” - Leon Tovar on Latin American Art

by Kim Cabrera • April, 2021

Leon Tovar, photo by Andres Serrano.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Leon Tovar has been bringing important 20th-century Latin American art to an American and international audience for years – but that wasn’t always the program of Leon Tovar Gallery. When Leon opened his first space in Bogotá in 1991, he was focused on showing a roster of North American and European artists such as Sol LeWitt, Bernar Venet, and Josef Albers. It was only after moving to New York in 1998 that he realized there was a niche to fill: “I got the idea to make clear the real connections between Latin American artists and broader art history… I started to work here and present important programming featuring Latin American artists in different areas – geometric abstraction, optical, kinetic.”

Now the gallery, which is celebrating 30 years in business, is firmly focused on educating collectors about Latin American art and broadening the scope of the art historical canon.

We sat down to talk with Leon about the need to make cross-cultural connections throughout art history, the responsibilities of dealers and collectors, and the evolving role of digital tools in today’s art world.

When did you first become interested in visual art?

My experience with art started when I was around 7 years old. My father—who was a prominent lawyer in Colombia and a very intellectual person—used to paint over the weekends. And my mother, she always saved money to buy small pieces of art. From the beginning we had paintings on our walls and I was really passionate about that. When I started to paint at 8 years old, I was like a mini artist. And from that period I started to learn to be involved in the arts all my life. I never did anything else; that was my only career from the beginning.

When I was young there was an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art of Bogotá, and it was one of my first exposures to geometric abstraction and optical art. A Venezuelan artist had been invited by the museum, probably Carlos Cruz-Diez, as he had a show there in 1985. After that, I became really passionate about how people can, with plasticity, communicate and express different ideas.

I went to Andes University to study art history, and when I was probably 18 or 19 years old I did an internship at a gallery in Stockholm. After that, when I was in my mid 20’s, I opened my first gallery in Bogotá in 1991 – as of this year we are 30 years old.

Early on, I was inspired after being invited by Sol LeWitt to his studio in Hartford. For my gallery in Bogotá, I started a program that brought international artists to the Colombian public, because it was difficult for people to go to museums in the States or Europe.

Leon Tovar at Sol LeWitt’s studio in Hartford, Connecticut, late 1980s.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How did you meet Sol LeWitt originally?

My sister was also an art dealer, and she was married to a Swedish dealer. Together we started to make a plan for the gallery’s program. As I mentioned, very early on I was impressed with geometry, minimalism. We thought it was really important to bring LeWitt to Colombia.

He was really interested in doing something in Latin America because he had only been in one small show that had traveled to Bogotá, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro in 1975 – that was his only approach to Latin America. So, he invited us to his studio in Hartford. I was really impressed because he knew a lot about Latin American artists, especially those that we have worked with for many years, like Carlos Rojas, Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar, Edgar Negret. At that time, those Columbian artists were not even popular in Latin America or their own country.

The first show at the gallery ended up being Bernar Venet and Sol LeWitt.

Leon Tovar with Bernar Venet at his studio, New York, 1992.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Since those artists didn’t really have exposure in Colombia, did you find that people understood their work right away, or did you have to educate the public about them?

Their work divided people, immediately.

People who knew a lot about color theory, the theories of Josef Albers, understood. And later, we did an Albers exhibition in Bogotá, and people were thirsty to learn. Bogotá was a very well-known city for literature and art, and we have great artists there, but people didn’t have the same access to information. The budgets of museums were very limited.

A lot of people didn’t understand the work. If I sold a wall drawing by Sol LeWitt, and after the buyer received a certificate, and were told they needed to bring people to remake the wall drawing at their own place, they would ask, “Is this real?”

But the press was really good to us back then and we got a lot of articles all over Latin America. Venezuelan collectors started to buy from us. They sent curators to see our exhibitions and that’s why I survived this adventure. People thought it was a great idea to bring New York artists to Colombia and provide the public with access to their work. And on top of everything else, people could purchase the art if they liked it. We quickly became very popular in Latin America.

When you came to New York, did you find that these American artists you had shown in Colombia were already known and represented? Did you have an idea of representing them when you came to New York, or did you plan to bring Latin American artists to the States?

In 1998, I decided to move from Colombia to New York, both to gain another perspective for the gallery and because the situation had gotten so bad in Colombia that it didn’t make sense to continue in Bogotá. I moved to New York with the idea that the program would be more or less the same as it was in Colombia. But when I got here, Bernar was with André Emmerich Gallery, Sol was with Paula Cooper. I knew that now I was in the big swimming pool, and I got it immediately and I didn’t produce any resistance.

So I got the idea to make clear the real connections between Latin American artists and broader art history. Sol taught me there were no walls, no borders. He knew exactly who Carlos Rojas was, and the names of other Latin American artists that only professors knew. Then I understood there were no limits to the gallery’s program. I started to work here and present important programming featuring Latin American artists in different areas – geometric abstraction, optical, kinetic.

Leon Tovar Gallery, East 75th Street, New York. Photo by Peter Baker.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Did you feel there was a lot of education you had to do with an American clientele, or do you think there was already an understanding here of Latin American art and its importance?

I had an advantage – I already knew how American artists worked, how European artists worked. I came here and learned a lot in the auction houses. I learned that we need to be very well-prepared with art historical knowledge in order to develop our program because most people have better ears than eyes. We need to explain to people how, why, optical art has been important. Why Yves Klein’s favorite artist was Jesús Rafael Soto. Why the Zero Group had connections with Latin American artists (one of the entrance pieces at the Guggenheim Museum for the Zero Group exhibition in 2014 was a Jesús Rafael Soto work). There are hundreds and hundreds of real connections, and this realization started from this chat with Sol LeWitt.

Museums started to become inspired, and in 2002, there was Body & Soul, one of the first important shows of art from Brazil at the Guggenheim Museum. It was probably among the earliest serious examinations of Latin American art.

Marcelo Bonevardi, Rampart, 1969, acrylic and charcoal on textured substrate on wood, © Estate of Marcelo Bonevardi.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Do you see yourself as filling in gaps in the art historical narrative?

If you’re a collector – a real collector – you need to find complements to your collection.

You can’t build a collection of Surrealists if you don’t include Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, Wifredo Lam, Roberto Matta. You cannot talk about geometric abstraction without Carlos Rojas, Carmelo Arden Quin, Lucio Fontana. You cannot talk about Impressionism without Armando Reverón, Andrés de Santa Maria, because they were Impressionist artists also. If you are a landscape collector, you go to the School of Barbizon, but you also need to see the School of Quito. The light in Bogotá is the same light in Biarritz; the landscape artists have a connection over thousands of miles, even if they don’t know each other.

As a collector, you need to develop this expertise. If you don’t, it’s difficult. The gallery does a lot of work—we have a lot of space to cover, and thousands of collectors don’t have this knowledge of Latin American art. That’s why we started to be important, because people realized the need to make connections along the whole spectrum of art history.

Leon Tovar Gallery at ADAA’s The Art Show, New York, 2020. Photo by Nicolas Manassi.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When you come to a new geographic region and you have to build a market for an established artist from elsewhere, you’re really building the market from the ground up. As the business owner, that is a long-term strategy and that doesn’t happen overnight – so here you are, starting a young gallery in the US, and you’re having to create a long-term view for it that may not have immediate financial benefits.

It’s a huge sacrifice. Huge. As difficult as it was to bring Sol LeWitt or Josef Albers to Bogotá in the late 1980s or early ’90s, it was just as difficult to bring artists like Carlos Rojas, or Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar, or Carmelo Arden Quin, or Sergio Camargo to America. And obviously New York is a very competitive city, but we love that type of competition.

Some of the artists we worked with in the beginning didn’t have any museum exhibitions or any really important approval from collectors. Over time we saw that change, and we saw their prices rise. We’re working with the most important of these big artists from Latin America. They are part of the art world, and there’s no room for speculation.

There are of course a lot of people that deal art for passion, knowledge, and education. And when people are really passionate, they never give up, even if they’re not economically successful. Obviously, the economic part is important, because you need to survive. But if you focus on one specific area and develop that knowledge, build the right program with the right artists, this will bring you success, sooner or later. It may take a long time, but don’t be stressed about the economic part because it will come; if you have a serious vocation, people will start to recognize that.

Leon Tovar with Jesús Rafael Soto and Carlos Cruz-Diez, Caracas, Venezuela, 1993.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Is there any advice you may have for new collectors?

Like dealers, there are different kinds of collectors.

Some young collectors are interested in collecting because they saw it in their own families and they want to continue the tradition, which is fantastic and beautiful.

Another type of young collector sees a business opportunity. That’s important, too, for the market. But if you want to build a long-term project, and want the dealers and galleries to respect you and give you the best information, you need to act responsibly as a collector. You have privilege, yes, but also obligations to the galleries and to the art that you buy. There are protocols that you need to follow. It’s a big responsibility. It’s more than people think.

If you educate yourself, you will always be a successful collector. You need to learn a lot, read a lot, go to museums. You don’t need to be rich to start to collect. The Vogels are a beautiful example that you can be the best collector ever, just with knowledge. Start now, start as soon as possible. It’s important. If you buy a nice art piece, and you start to build your own collection, that will put you in a position to collect further. Start today.

Leon Tovar Gallery at Bogotá International Art Fair, 2016. Photo by Mateo Saenz.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In this past year, a lot of the ways in which art dealers do business has changed. Can you talk about some of the changes you’ve seen, whether positive or negative?

I could spend two hours answering that question. I think today, the most important shift as a result of the current need for digital outreach is that galleries have started to be important again.

Important galleries – no matter their size – will survive, and prevail, because now collectors, more than before, need to have confidence in their dealers. They cannot go to art fairs, and they need to trust in the expertise of the gallery. If people want to buy Latin American art, they would prefer in this case to buy it from us, or from a serious dealer from Latin America, rather than to try to buy things online from someone they don’t know.

Digital tools give us an advantage but can also work against us. At the end of the day, you don’t always have control over the information that’s put out into the digital world. It’s a very risky moment right now in terms of information, and misinformation, too.

But in the pandemic, if you use these tools with level-headedness and with discretion, like we do at the gallery, it’s an advantage. They help a lot. You can do digital exhibitions. But at the end of the movie, galleries will be there forever. I think we are, in our case, using our platforms very responsibly. We don’t want to be aggressive with people because they are fatigued with digital platforms. You need to manage that.

I think you make a compelling and resonant point – while the digital platforms provide access, nothing can replace the value of humanity and personal relationships. And it is the relationships that will ultimately survive this process.

Exactly—it’s the sharing of knowledge. Knowledge is not Google. Dealers need to build experience, to spend the hours, spend your life, your money, your energy, probably your own private life. As a dealer you need to educate yourself, as much as an art historian. When you do this, you dignify the whole ecosystem, with collectors supporting galleries, galleries supporting artists, and artists supporting museums.

You can’t do everything online – that’s why museums postponed exhibitions. It doesn’t make sense to spend millions of dollars to do an online Francis Bacon retrospective. You need to bring people to the museum so they can see why Bacon is Bacon.

We will be back in person eventually, and will also continue making use of digital platforms. But we, at the gallery, will go back to our roots because a year ago we were so crazy and in such a rush. The fairs, the exhibitions, and also the preparation of these events – it’s a huge responsibility, a huge undertaking. Even though we are a small gallery we have a big operation.

Now we’re calmly developing our program. We’ve deaccelerated our process. We are going slower, but we are more precise and focused. You learn to be more selective with your time, and think seriously about what you want to do in the future. The collectors will come to you. If you have good work, they will come.

Leon Tovar greeting the King and Queen of Spain at ARCOmadrid, 2015.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the course of these conversations, themes develop organically. Responsiveness and shifting goals to meet your situation seems to be a theme for you.

It’s a combination of opportunity and resourcefulness – together, this makes you lucky.

We take opportunities. We’re competitive, we’re active, and we know what we’re doing.

100 years from now, 200 years from now, what do you hope will be the legacy of your gallery?

I’d like to think that a crazy, small gallery from Colombia started a project that eventually was developed for universities, for education, for the future. I think that Latin America, as a vast region, has suffered a lot. The artists from these countries make incredible efforts to manifest their own feelings and ideas, and are as important as any other artist in the world.

I think the most important thing is that people realize that knowledge is the key part of our program. We are here – humbly – to educate people about Latin America and the connections that exist between our artists and the rest of the world.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All images courtesy Leon Tovar Gallery, New York.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I Like to Put People and Art Together" – Wendi Norris on Connecting with a Wider Audience

by Kim Cabrera • December, 2020

Wendi Norris, photo by Marc Olivier Le Blanc.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the early 2000s, having spent more than a decade working in tech and business, Wendi Norris was feeling burned out and professionally unfulfilled. She began to think about what was missing in her work and why it was leaving her so unsatisfied. “I noticed that the people around me who were doing what they loved were also the ones who were the most successful,” Norris told us.

That realization would lead to the opening of Gallery Wendi Norris, headquartered in San Francisco. Working at first with a business partner, Norris took full control of the gallery around 2011, which allowed her to pursue her own, very specific curatorial vision. The gallery is often associated with the work of Latin American Surrealists, including Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. The roster, however, is wide-ranging, incorporating modern artists such as Dorothea Tanning, Wolfgang Paalen, and Alice Rahon with contemporary artists such as Chitra Ganesh, Ana Teresa Fernández, Peter Young, and Ambreen Butt.

Gallery Wendi Norris has a unique business model that is rooted in flexibility and focused on building relationships. Central to the gallery’s vision is a commitment to site-specific, multi-city exhibitions, allowing Norris and her team to travel to wherever they feel will best serve their artists and facilitate connections with collectors, critics, curators, and the public on a larger scale.

We chatted with Wendi about her decision to become an art dealer, her flexible gallery model, and how passion, scholarship, and solid business sense work together to form the gallery’s foundation.

Ambreen Butt, Mohammad Yaas Khan (16), 2019, text, watercolor with white gouache, and pen on tea-stained paper.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When did you first become interested in visual arts?

For me, there was definitely an “aha!” moment. I was a junior in college on a study abroad program in Madrid. At the time, my academic interests lay in economics and Spanish. I was allowed to take one elective during the semester, and I somewhat randomly chose art history.

At the end of the first class, my professor said, “We're going to meet on Tuesday at the Prado before it opens.” I had no idea what he was referring to, and I actually raised my hand and asked him what the Prado was. Anyway, I remember being at the museum; I remember being drawn into the fantastic and terrifying world of Goya. But mostly I remember entering a dark gallery, approaching a canvas, and finding myself in front of Velázquez's Las Meninas. I was mesmerized. I had goosebumps. I couldn’t tear myself away from it. I had never seen anything like that. That was the moment, for me, at which an entirely new world opened.

You have this moment at the Prado and you realized that art resonated with you. But you were actually in the tech world for 10 years before you shifted into the gallery world, is that right?

I worked for at least ten years in tech and business before making the shift. During that time, I was primarily working overseas. The first two things I always did upon arrival in a new city were to visit the local market and to find my way to the museums. It's still the way I travel. You can get a very good education in art and culture at markets and museums.

Before I moved to San Francisco in 1999, I lived above an art gallery in Paris. I got to know the owner and a few of his artists really well, and I bought my first piece of art from him.

So, you're back in San Francisco, you've made the choice to leave tech and to open the gallery—what were your initial ideas about what the gallery would be?

I began according to my training and education in business; I wrote a business plan. I still have that plan, tucked away in a private file. My early ambitions were moderate—I just knew that I wanted to be in the art world. But those ambitions started to take shape as I wrote my plan. My early vision was mostly values-based. It was not about wanting to have multiple galleries around the world and sell work at such-and-such a price point. It was more along the lines of, “I want to work with great artists.” It still is. I was also interested in connecting as many people as possible to art by presenting important exhibitions and educating people throughout the process.

In the midst of writing the plan, I organized an exhibition for two of my closest friends who are artists. I invited friends and business colleagues and I sold every single piece. That was really a catalyst for me to say, “OK, I'm doing this.” It was proof that I could do it.

Is that ability to sell a skill set from your previous career? Or is that something, because you're passionate about the work, that came naturally?