any pronouns | swana & baltoslavic | hijabi | cancer ☉ aries ☾ leo ↑

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

I have a question about Kupala. Was she(or he?I’ve read different things) an actual deity that was worshipped or just a name for a festival ? I read that Kupala and Kostroma were two sibling gods but from what I’ve read they sound a lot like Yarilo and Morena. Could you help me with this ? Thank you for your time

I’m sorry my answer took so much time but this question is actually very complex and there’s quite a lot of highly localized lore to untangle. To make this easier I would ask that you temporarily forget everything you’ve learned about Kupalo, Kostroma, Yarilo and Morena. Let’s pretend we are hearing those terms for the very first time and let slavists walk us through their meaning and significance in Slavic culture.

Fair warning, I prepared a lot of quotes!

Russian folk belief by Linda Ivanits:

Like Shrovetide and Rusal'naia Week, Kupalo's Day was often represented by a doll or scarecrow named for the holiday and ritually destroyed (burned, drowned, or torn apart) at the end. Such rituals took the form of elaborate mock funerals in which wailing was intertwined with scoffing and laughter; peasants played the roles of the priest and deacon and censed the ''corpse'' using a clay pot steaming with hot coals and dung or a worn-out bast shoe. Nor were these the only occasions on which such funerals were held. We have already mentioned the analogous destruction of special trees during the Trinity and Kupalo celebrations and the funeral games of Yuletide. Similar rituals with effigies named "Kostroma" or "Iarilo" occurred in a number of places in Great Russia, usually between Trinity and St. Peter's Day. In addition, there are reports about a curious ritual burial and, sometimes, exhuming of a cuckoo, usually in effigy. The frequency of such rituals is so striking that we must agree with Propp's suggestion that they may well be the basic element in these holidays. Moreover, they are an element that Russian holidays shared with those of other agricultural peoples worldwide.

Rusalki: Anthropology of Time, Death, and Sexuality in Slavic Folklore by Jiri Dynda

The overall structure of provody rusalok (processions of rusalkas) is analogous to various Slavic folk rituals in which an effigy personifying a certain festival or season is seen off in a procession and ritually disposed of. A similar structure can be found, for example, in the East Slavic festival provody maslenicy, “seeing off maslenica”, in which an effigy of maslenica (Lent, or Shrovetide), is carried out of the village and then buried in a ritual mock funeral. Provody maslenicy took place usually sometime in March and were parallel to the West Slavic custom of carrying out the Morana/Death. A very close parallel to seeing off the effigy of rusalka is the troickaja or semickaja berezka, Trinity or Semik Birch. In this ritual girls and boys from the village chopped down a young birch tree and then carried it from the woods into the fields and tossed it there – allegedly, as we know from the rare emic interpretation of such ritual, they did so to ensure a sufficient amount of rain for the upcoming summer. Basically, every season of the year could have its special provody ritual that ended it. We can find the most striking similarities with the mock funeral of rusalka in the Kupalo festivities which took place on the summer solstice, that is on the Eve of John the Baptist, Ivan Kupalo (23rd–24th June), and in which a male ithyfallic effigy, called Kupalo, Jarilo, Kostroma, etc., was buried and sometimes resurrected again. Kupalo festivities took place near water and were replete with erotic symbolism, bathing, fire jumping, and dancing on the ritual fields called igrišta – church literature reprehended the orgiastic nature of this ritual. Moreover, sometimes, since Pentecost is a moveable holiday dependent on the date of Easter, the provody rusalok might occasionally coincide with Kupalo.

Religia Słowian by Andrzej Szyjewski (fragments translated by me):

Yarilo’s attributes clearly point to his role as god of vegetation and fertility. The girl assuming his likeness during the festival, also known as Wiosnołka or Wiesnowka (trans. notes: pronounciation „vyos-NOHW-kah” or „vyes-NOHV-kah”) could be an echo of „divine bride”, an offering to the god, an incentive to arrive with the spring. Many songs refer to Yarilo causing the earth to sprout and bloom as he walks but also summoning dancing girls to him. Circle dances, white robes, white horse and the cut off head are all elements of solar symbolism. The head belongs to Old Yarilo, dethorned and overpowered by his young son. All over the world similar symbols exist - from celtic Curoi to mayan Hunahpu. Young Yarilo matures and dies as the harvest unfolds, then at the end of summer a funeral is held - this time main roles were played by young married women not maidens. They made an effigy of Yarilo (putting some extra effort into shaping his reproductive organs) that they called Kostrub („COST-roob”) and then they put him into his grave, in the ground since in the earth the sun loses it’s powers and dies, letting the new sun take over. The people would sing and cry out about Yarilo dying and ask him to get back on his horse in his golden saddle. Attempts to reconstruct the rituals seem to show that young Jarilo on white horse was juxtaposed with old Yarilo on black goat. Southern slavs practice similar rituals of burning old Badniak (a piece of wood with forked roots) on Christmas Eve to make place for young Božič (son of god). Western Slavs don’t have a deity corresponding to Yarilo - they close the winter in rituals involving Marena/Marzanna, followed by a procession carrying around „maik” or „nowe lato” symbolized by the peak of an evergreen coniferous tree or a rooster as a solar bird.

The Slavs were an agricultural society so agrarian deities were their primary source of relations with divine, cosmic forces. There is a certain myth/archetype that is characteristic for early farmers, the myth of creative murder, in which the first birth, growth and harvest are prompted by the first death - death of a deity, hero, ancestor, who dies sacrificing himself for the people, and from his body the first plants spring, allowing the people to survive. That myth, encated in many cultures in many ways leads to the concept of a solar god that dies and is reborn cyclically, whose individual fate is reflected by the cycle of growing grain. The stalks loose their heads under the sickles for people to be able to feed. Yarilo (and maybe even Yarovit) makes identical sacrifice.

Slavic folklore: didactical guidelines by Laima Anglickienė

An equivalent ritual called the Funeral of Kostroma was performed in other regions in Russia (around the Feast of Ascention). It was also attended by girls exclusively, with one of them playing a role of Kostroma. In the beginning, she would treat girls with pancakes; afterwards, girls would talk about her illness and death. Then, a straw doll of Kostroma was buried; it was set on fire, tossed into water or torn to pieces.

In Ukraine, in the eve of Kupala, a maple, birch or willow was cut down, erected on a hill and adorned with wreaths, flowers, ribbons, even candles. The tree was called Morana / Mara or Gilce (such a name was also given to a wedding tree). People would perform round dances around the tree and sing. Like on Christmas, Russians would make a straw doll, dress it in female clothing and place it under a tree. They would call the doll Kupala / Morena / Mara; in later times, it was given female names such as Marina or Katerina. A bonfire was lit near the tree, with a pole topped with an old wheel / hub or a pole topped with straws in the centre of it. Before the end of the feast, a tree was thrown into the river. A straw doll was burned down and the ashes were sprinkled across the field.

In Belarus, the bonfire was called kupala. A pole with a hub or a cow / horse skull was set in the middle of it. Girls would throw tows into the fire for a good yield of flax, while firebrands were cast around the fields. Instead of a tree, Belarusians used to make a straw doll of Mara. Singing, they would carry the straw doll behind the boundary of the village, where it was burned down or drowned.”

Jarilki – the last Sunday before the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul (29 June) is called the Fast of Eggs of the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. The East Slavs would boil eggs, eat them and throw them at each other. Youth would light bonfires and play games on a hill known as Jarilo bald- pate throughout the night. Women would make clay stacks – Jarilo and Jarilicho. Afterwards, they would beat or drown them. Youth would go for a swim. Apparently, Jarilki was celebrated in those regions where the feast of Kupala was not held. Little is known about this feast; most information comes from the Volga Region situated in the neighbourhood with the Mari people, who practiced pagan- ism for the longest period of time. Ukrainians would sing songs mentioning both Kupala and Jarilo: “Jarilo passed away, so good he was / Kupala Ivan fell down to water”

Researchers assume that summer feasts (Kupala, Jarilki, funeral of Kostroma and Feast of Saints Peter and Paul) rose from a single common source – a mass pagan feast dedicated to commemorate the peak of the summer and to get ready for harvest time. It is likely that ancient Slavs had a single feast dedicated to Jarilo (god of the sun and love, giver of life and fertility), which continued from the Feast of Saint John the Baptist to the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

Jenny Jones and Kostroma by Lisa Warner

The analogous Russian game, also played by small girls in the nineteenth century, was known as 'Kostroma'. The festival of 'Kostroma' as it was known in Northern Russia or 'Kostrubon'ka' in the Ukraine, was part of the spring cycle of ritual agricultural ceremonies and was celebrated between Whitsun and the beginning of the St Peter Fast on the 29 June. In its ritual form 'Kostroma', performed by the young women of the villages consisted of three main parts; the preparation, the funeral procession itself and the burial. During the preparation for the ceremony a young girl was chosen to depict Kostroma, or a large doll was fashioned from straw and dressed like a peasant woman in shirt and 'sarafan'. A scarf was tied round the head and the figure, decked with garlands of flowers, was ready for the funeral procession in which Kostroma, now dead, was placed upon a bier and escorted to the nearest river or lake. The women who accompanied the procession, including one who represented the professional lament-singer hired for village funerals, lamented the departed. Finally, the doll was undressed and cast into the water.

In its salient features this ceremony corresponds to a whole series of other spring and summer rituals beginning with Maslenitsa in February, Semik in the 7th week after Easter, Yarilo between April and June, and ending with Ivan Kupala (St John's Eve) on the 24 June. In all these an anthropomorphic figure representing the spirit of vegetation is seen to die, and is destroyed or buried in a mock funeral to which various realistic details were often added; a mock priest, mock relatives, even a mock widow if the doll was male. A resurrection was not unknown in some parts of the country in particular the Ukraine. Kostrubon'ka, in a variant described by Professor A. Beletskii rose from the dead to the following joyful verses from the choir:

He has come back to life, come back to life our Kostrubon'ka! He has come back to life, come back to life our dear one!

Ivan-da-Maria by Valeria Kolosova Here I would like to examine the ideas about several plants which are rather popular in traditional Slavonic culture and are named ivan-da-marja. With equal frequency, two plants may be associated with this phytonym – blue cow-wheat Melampyrum nemorosum (Scrophularineae) and violet trichromatic Viola tricolor (Violaceae). Both plants are notable for the unusual color of their parts: petals of a violet have different colors, and blue cow-wheat’s bracts are violet, unlike the green lower leaves, so they are perceived as flowers alongside real flowers, which are yellow. This feature allows us to analyse both plants within the limits of one article.

This very feature has obviously served the reason for etiological legends surprisingly similar in their plot all the over East-Slavonic territory. For example, in Kholmskaya Russia (Litinskiy uyezd) they said that a brother and a sister, not having recognized each other after long wanderings, got married; having learned the truth, the brother said: «Well, my sister, let’s go to a field and sow ourselves: you will blow in violet color, and I – in yellow». This plant got the name bratki [brothers]; compare also: «This is the grass which is a sister with a brother!».

According to a Belorussian legend, a brother and a sister have also turned into a flower brat-sestra [brother-sister] with blue and yellow flowers.This plot exists also as a song; its variants are recorded, for example, in Belorussia (Vilno province), and in Ukraine. Similar stories can be collected today as well. So, in the village of Radutino (Trubchevsk area of Bryansk region) it is said that when a brother and a sister were led to the altar, «during the church wedding ceremony their wedding crowns disappeared. They were on the church dome. The brother and the sister became flowers. People say: this is the grass which is a brother and a sister». And one specifies: «blue is the brother, and yellow is the sister». (…) In a Ukrainian variant «a brother became angry with a sister, ran after her, and strangled her: she turned yellow, and he, having been frightened, turned blue».

Special power was attributed to ivan-da-marja, collected on St. John’s Day: among other plants, it was one of the flowers picked up to be used against evil spirits: «Fern, then blue cow-wheat and mugwort – all these herbs, they say, are against sorcerers». Phytonym besoprogonnaya trava [the herb driving away demons] speaks about endowing of a violet by apotropaic properties (Arch.). This plant was thought to be able to provide good health: «Among Russians, if somebody wants to be healthy during the whole year, he/she, having bathed at St. John’s night, rubs all his/her body with a flower of ivan-da-marja». This flower was a component of a bath besom as well: «In some places of the Novgorod province, near Old and New Ladoga and Tikhvin, on St. John’s Day one heats a bath and, having stuck the herb ivan-da-marja into brooms, takes a steam bath on this holiday with the purpose to receive health. In Moscow there also existed a custom of steaming by besoms with ivan-da-marja. In St. Petersburg ivan-da-marja along with buttercup, nettle, fern, camomile, mint and wormwood was a part of a midsummer birch besom on the eve of St. Agrafena’s Day.

The motive of a brother and a sister, typical for midsummer rites, was analyzed in Vyach. Vs. Ivanov and V. N. Toporov’s book «Researches in the area of Slavonic antiquities». In their opinion, the interdiction of marriage and its violation should be compared to stories about removal of interdictions on sexual relations between all men and women during midsummer night. The sister is the source of maliciousness in these stories, and as such plays an active role. The authors of the book put forward the assumption that “the prototype of death (and water/sea), expressed in the corresponding form of (*mer-, *môr-) is reflected in the song of Maria and other Slavic songs of St. John’s Day, whereas John is the prototype of a twin, connected with life and fire. Element “Marja”, as the name of the two major beginnings may be connected to the aforementioned Mara, preserved only as a survival in certain rites of St. John’s Day”. Deriving the pair of Ivan-and-Maria from a more ancient pair like Kupala-and-Maria, the authors of the book attempt to reconstruct the motif of matrimonial combat of fire and water, reflected in the rite and the song. Referring to byel. dial. kupalo ‘fire’, they put forward an assumption that the root kup- contains semantics of both fire and water.

Okay now let’s unpack all this information!

Effigies known as Mara, Marzanna, Maslenitsa, Kupalo, Kostroma, Kostrub and Yarilo seem to all belong the same general type of traditions - rituals connected with the argricultural cycle of nature, that can be performed at the end of pretty much every season to ensure that said cycle continues, the fertility of the land is ensured and the Slavs don’t starve. The effigies are destroyed or burried in an elaborate funeral to re-enact the archetypical idea of “creative murder” reflecting the growth cycle of grain.

The effigies frequently have an androgynous quality to them - some, like Kostroma, can be seen as female in one region and as male in another, in some names of both Kupala and Morena are applied to a doll used in identical rituals, it’s also fairly common for young girls to represent a masculine persona during the rituals (as Yarilo or Kostroma). The flower Ivan-da-Maria is also connected with the idea of androgyny, especially under it’s alternate name Sidor-Marja (V. Kolosova, same article).

Ivan Kupala is, especially in East Slavic tradition, heavily identified with Saint John the Baptist. That doesn’t authomatically mean the character is not connected to a pre-Christian deity. It’s fairly common for pagan gods and Christian Saints to become syncretized creating a unique local interpretation of them - and example could be Saint Nicholas syncretized with Veles, or Saint Paraskeva and Mokosh.

There is no doubt that aforementioned traditions have roots in pre-Christian Slavic beliefs and culture. That doesn’t necessarily mean that every effigy named here is a representation of a separate Slavic deity. It’s very likely that orginally certain pagan deities were associated with those celebrations, however it’s hard to say how many and which. I see a lot of people who view Mora/Marzanna or Yarilo as deities. On the other hand you rarely ever find someone treating Kostrub or Maslenitsa as a one. In the quotes we can see that Szyjewski clearly considers Kostrub and Yarilo to be representations of the same deity. Anglickienė seems to be tenderly suggesting that Yarilo and Kupalo are the same entity. Dynda seems to treat the traditions of Kupalo, Yarilo and Kostroma as interchangable. How many of them are deities? How many are merely personifications of a holiday/season (not the same thing as deity!). How many were considered to be simply spirits of nature (such as the “spirit of grain” preserved in the last uncut sheaf of grain, or directed in a ritual known as ”curling of Nicholas’ beard”)? This would also be a good place to add that modern Slavs participating in say, drowning of Marzanna, generally don’t see the effigies as something spiritual or divine, a dwelling of the spirit — but merely as a symbol.

Onto the stories of twins/lovers Kupalo and Kostroma or Yarilo and Morana - now you know where they originated from! Ivanov and Toporov analysed stories associated with a plant that plays an important role in the celebrations of Ivan Kupala and suggested that “Maria” represents forces of death and water while “Ivan” represents forces of life and fire, and that this duality, a matrimonial struggle between fire and water plays an important role in Slavic beliefs surrounding the summer solstice. They also proposed that those “Maria” and “Ivan” and the forces they represent might be connected with Mara and Kupala, effigies used in midsummer rites.

Of course many Rodnovery communities have happily run with the story embellishing it more and more and presenting it as a Well Known Fact rather than subtle speculation. You can see there existed many versions of the story, different from the one examined by Ivanov and Toporov, in which it’s the brother not the sister, who is the malicious one (killing his sister), or where neither is malicious. The color associations of the plant also seem to depend on the region where the story is told. Yellow, typically connected with the ideas of light, fire and life can be presented as the color of either brother or sister; same of course goes for the purple. I am not trying to say Ivanov and Toporov got it all wrong, they are certainly onto something, and like all slavists they were doing their best while working on very incomplete data. That’s why we can often find many contradictory theories on the same aspect of Slavic pre-Christian belief.

I know lack of any definite answer can feel very unsatisfactory (been there many times) but I hope that with all the information presented above you will be able to come to your own conclusions and form your own theories on the subject. Or at least have some context for the next time you see Slavic pagans discussing those subjects.

Please keep in mind that I did not receive any academic education on this subject and all the knowledge I have is self-taught, based on the sources available to me and lacks academic systematisation.

Any word I may have overspoken, any word I may have underspoken, be my words helpful and true.

178 notes

·

View notes

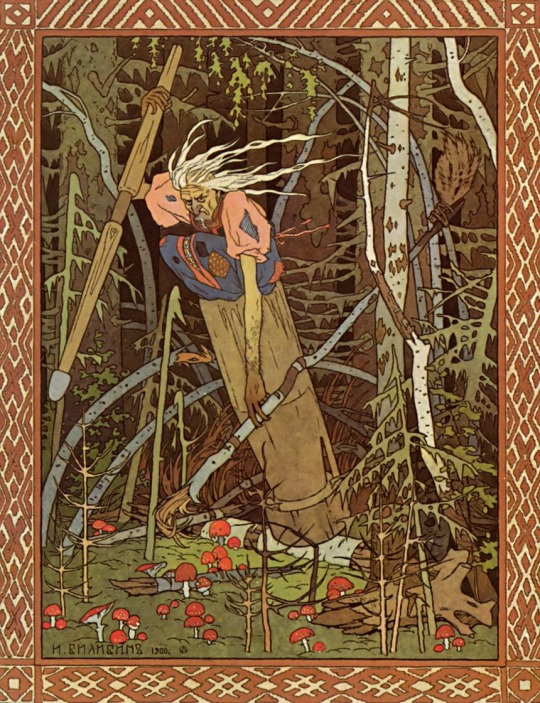

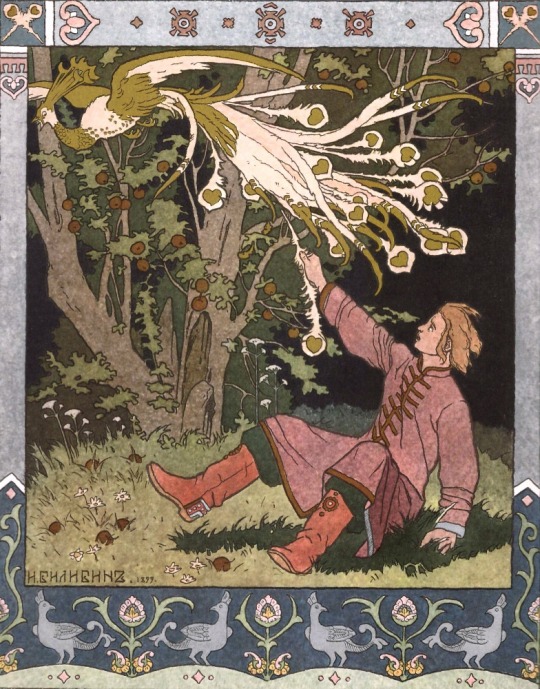

Photo

Illustrations for Russian fairytales by Ivan Bilibin

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Смерть ворогам

The day before yesterday there was a whistling overhead and explosions could be heard nearby. The Russians hit critical infrastructure and the country was left without electricity and water. Only now there is light and heat in my house.

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

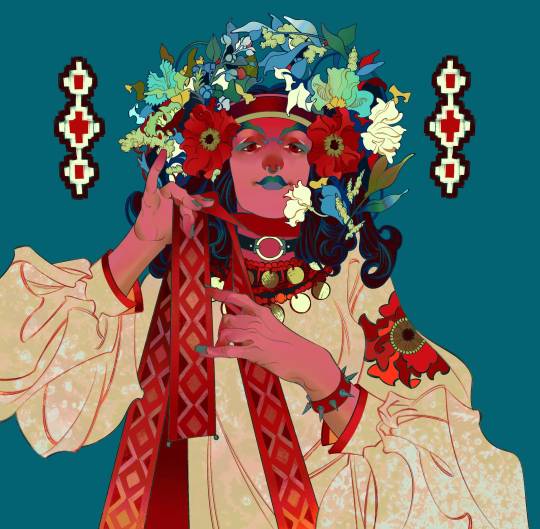

Листівки зі "слов'янськими богинями" ми з benjiro451 робили на кку2019. Давайте не звертати уваги на повну історичну недостовірність та вигадки велесової книги, ми були малі-дурні, тим не менше набір вийшов шикарний.

217 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary Jane Newill, Bedcover, ca. 1908, linen embroidered with colored wools

46K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello I was wondering about popular or common Slavic embroidery patterns ? I unfortunately don’t know how to embroider myself, but I would like to incorporate it into my drawings and paintings as art is a big way for me to connect spiritually. Thanks so much !

First of all ”Slavic embroidery patterns” are a huge subject. There are many Slavic states and countless smaller regions within those states that have their own unique and characteristic patterns.

Having said that I here are some sources for you to check out:

Polish folk embroidery by Jadwiga Turska

Ukrainian folk embroidery by K. R Susak and N. A. Stefyuk

Some Balkan Folk Embroidery Patterns by Edith Durham

Ukrainian Rushnyky: Binding Amulets and Magical Talismans in the Modern Period by Frank Sciaccia

And make sure to check out the great blogs we have here: Polish Costumes, Zvetenze, Me-Sharing-With-The-World, Eastern European Crafts and Pagan Stiches.

Best of luck!

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

bloodstained witch

i think signora could have worn anything alexander mcqueen rly well. dress and pose from mcqueen's FW 1998 'joan' show

4K notes

·

View notes

Video

356K notes

·

View notes