The official Tumblr page for the Jackmeister YouTube channel, examining history and the Mongol conquests of Chinggis Khan, or whatever other topics interest me. Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/c/TheJackmeisterMongolHistory On Facebook too: https://www.facebook.com/TheJackmeister/

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The fourth and youngest son of Chinggis Khan and Börte Khatun, Tolui acted as regent of the Mongol Empire between his father’s death in 1227 and his brother Ögedei’s enthronement in 1229. During this period he cancelled military campaigns, worked to maintain Mongol control over newly conquered territories (especially around Zhongdu, modern-day Beijing), oversaw the burial ceremonies of his father, and preparations for the quriltai to empower Ögedei. While there is some suggestion that some of the princes wished to enthrone Tolui instead of Ögedei, (partly, it is thought Tolui was seen as the more skilled commander of the two) Tolui did not counter his father’s will and publicly backed his brother. After Ögedei became Great Khan, Tolui served as one of his generals against the Jin Dynasty, before dying, likely due to his excessive alcoholism, in 1232. His death was a major blow to Ögedei. After his death Tolui was known by the title of Yeke Noyan, 'Great Lord," and later his son Khubilai posthumously gave him the title of Ruizong, "Perceptive Ancestor." During this later period when Tolui’s son were rulers in their own right, they appear to have also anachronistically increased Tolui’s importance and power, (especially during the period of Khubilai Khan, where his regency is made a much more formal thing that it probably ever actually was) and made it appear that even Ögedei wanted Tolui to be Great Khan.

Tolui’s four sons with his wife Sorqaqtani Beki —Möngke, Khubilai, Hülegü and Ariq Böke— went on to become some of the most important figures of the later 13th century, each of whom having a profound impact on the Mongol Empire and thereby, world history.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

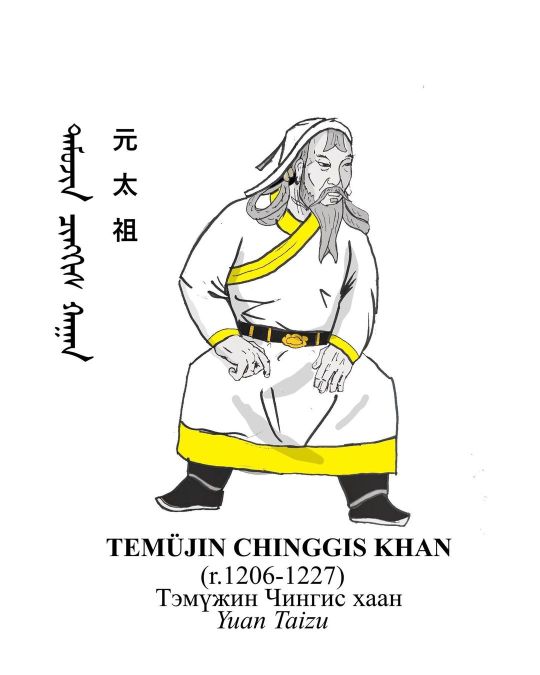

For the next few weeks, I will post depictions, in chronological order, of all the rulers of the Mongol Empire from 1206-1388. Each will have their names in English, modern and traditional Mongolian scripts, as well as the temple names given to them during the Yuan Dynasty

First up is a man who needs no introduction— Chinggis Khan, founder of the Mongol Empire. Born Temüjin son of Yisügei around 1162, after a youth of hardship, he solidified his rule over the people of the Mongolian plateau and established the Mongol Empire in 1206. From there he began a series of conquests that took him to North China, across Central Asia to the borders of India. His state had an immense transformative impact on the regions it conquered, and descent from him remained one of the premiere forms of legitimacy for rulers as late as the 18th-19th centuries in some areas.

While he had a number of wives, the most important was his yeke khatun Börte. His four sons with her —Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei, and Tolui— each became important dynastic progenitors in their own right. The uncertain paternity of Jochi ultimately culminated in his third son, Ögedei, becoming his designated heir. Chinggis died while campaigning against the Tangut Kingdom in 1227, possibly from internal injuries after a fall from horseback, but due to his orders for secrecy, the precise reasons will never be known. He was buried in a secret grave on Mount Burkhan Khaldun in Mongolia, a practice most of his successors followed. His grandson Khubilai posthumously entitled him as Yuan Taizu, “Great Founder of the Yuan Dynasty.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

An older Chinggis Khan with his primary empress, Börte Khatun, from my video series on the daughters of Chinggis Khan.

Börte was a year older than Chinggis, but we don't know when she died. The last time she is mentioned by name is around 1210, during the fall of Teb Tenggeri. After that, the sources only make references to "empresses" of Chinggis, which could refer to Börte or any of Chinggis' other major wives. Writing in 1237, the Song Dynasty envoys Peng Daya and Xu Ting however, wrote that Ögedei's mother was still alive.

"since [Chinggis'] death, Ukudei's mother has personally led his cavalry army." (Peng Daya and Xu Ting, "Sketch of the Black Tatars," trans. Christopher Atwood, (2021) pg. 123.)

The phrase is rather referring to the inheritance of Chinggis' ordu and troops rather than the empress actually leading the army in the field (as otherwise the sources don't mention Börte, in her mid-70s, leading an invasion of Song lands).

But, as Atwood speculates, it's hard to know if this is really Börte being referred to her, or another of Chinggis' surviving khatuns which the Song authors confused with Börte. It was not uncommon for these types of sources to be confused by the identity of the wives and their relationships with the khan and his sons. A favourite example is Gürbesü the Naiman queen, who changes from Tayang Khan's wife or mother depending on the source (she was a young wife of Tayang's father, who after the father's death was inherited by Tayang. She was not his mother, but step-mother, and later was married to Chinggis after the defeat of the Naiman.

Link to my video series on Börte and her daughters

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

New video coming tomorrow on Qutulun, the famous wrestling princess — and what the sources say about her life beyond the wrestling tales. It's currently up now for patrons and channel members.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BATTLE OF 'AYN JALUT, SEPTEMBER 1260

'Ayn Jalut stands tall as the most famous Mongol defeat; a Mamluk army commander by Sultan Qutuz and Baybars defeated a Mongol force under Kitbuqa Noyan.

The battle though is a surprisingly tough one to study; it's noted in numerous contemporary sources, but most descriptions only focus on a small aspect, and none give an overall account. The closet we get to an overview is the version given by Rashid al-Din, which makes the battle a feigned-retreat employed by the Mamluks... except this version is totally contradicted by all the Mamluk versions of the battle. Given that Rashid al-Din's account also features a dramatic lengthy, and fictional, speech between Kitbuqa and Qutuz, it seems Rashid's entire version is probably his creation.

The best reconstructions (based off the accounts from Mamluk chronicles and other contemporaries) suggest that the battle took the following form:

1) Mongols arrive first at 'Ayn Jalut; a period of skirmishing between the Mamluk vanguard under Baybars and the Mongols. Baybars withdraws to await arrival of Qutuz with the main army

2) on September 3rd, the Mamluk force arrives at 'Ayn Jalut and form up for battle early in the morning. They begin to slowly advance against the Mongols

3) Kitbuqa responds with attacks along the Mamluk line; volleys of arrows before charging in with Mongol heavy cavalry. Kitbuqa appears to underestimate Mamluk resolve and expects they will break quickly

4) the Mongol charge forces the Mamluk lines back and they nearly break; Qutuz and Baybars rally the Mamluk army. The Mongols pull back, reform and lead another charge.

5) Once more the Mamluks nearly break, and again rallied by Qutuz with cries of "wa-islamah," and his personal bravery in leading a counter charge.

6) perhaps at this point in the battle, either on his own initiative or prior communication with Mamluks, the Mongols' 'Ayyubid vassal on their left flank, al-Ashraf Musa, flees the field.

7) this allows Mamluks to encircle the Mongol army; likely around this point Kitbuqa is killed. His army now breaks, pursued by the Mamluks. Baybars dismounts to chase some on foot up a nearby hill.

8) there is no rallying of the Mongol army at Baysan; this is a faulty reading by al-Maqrizi in the 15th century.

9) none of the accounts of the battle support the use of firearms in the fighting; this only comes from slightly later military treatises aiming to glorify the use of these weapons.

You can learn more about Mongol wars with the Mamluks and the battle of 'Ayn Jalut in my latest video:

youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

All five parts of my series on Mongol Heavy Cavalry are now available to watch on Youtube. Which has been your favourite?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final part of the heavy cavalry series is now up, looking at the wars with the Mamluks!

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like the hooves of Mongol horses, books by Timothy May will travel everywhere, such as the beaches of the Aegean Coast of Türkiye.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like the hooves of Mongol horses, books by Timothy May will travel everywhere, such as the beaches of the Aegean Coast of Türkiye.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Part 4 of the series on Mongol heavy cavalry is now up! This time we look at battles with knights and the confrontation at Muhi.

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DELHI SULTANATE WAR ELEPHANT, 13TH CENTURY

One of the images I made, but didn't end up using, for my video on Mongol heavy cavalry in the wars against the Khwarezmian Empire and Delhi Sultanate.

War elephants were rarely part of the Mongol army: the Mongols found more use for them in labour or as mounts for Khubilai Khan while he travelled or hunted. They were otherwise seen as too cumbersome, unreliable and difficult to feed for regular military usage. The Khwarezmians had only a few that they took from the Ghurids which played no real part in the war against the Mongols. In contrast, the Delhi Sultanate made great use of them, armouring them and placing towers on their back to hold archers and javelin-men. Mongol armies also faced them in south eastern Asian, fielded in great numbers by the kingdoms of Dai Viet, Champa (today's Vietnam) and Pagan (Myanmar).

The general idea seems to be that for the Mongols, elephants were hard to kill outright, especially when armoured. They were also troublesome as their scent and sound frightened horses. However, the Mongols proved capable of driving them mad with concentrated arrow-barrages, at which point the animals became a liability and would run wild through their own lines. Unfortunately, the sources give rather few details as to most Mongol-elephantine military interactions.

This elephant here is based off our brief source descriptions and paintings from early 14th century editions of the Ilkhanate's Jami' al-Tawarikh to depict a Delhi war-elephant. The mahoot and javelin-man are Hindus in Delhi service, with a Turkic archer accompanying them.

I talk about Mongol heavy cavalry in the war against Khwarezm in my latest video:

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I received a message asking about the Khwarezmian footman and his kite shield (something typically, though inaccurately, assumed to be a European-only design) that appeared in my post earlier today on the battle of Parwan, so I thought I'd share the source for it.

A common style of pottery in the Seljuq and Khwarezmian empires is the Mina'i ware style, produced chiefly at Kashan in Iran up until the start of the 1220s (guess what happened...)

It's a lovely style which shows many Seljuq and Khwarezmian figures, mainly horsemen but occasionally other figures too. This specific one (produced, according to the description, in 1219) shows the rare depiction of both an elephant, and likely a infantry man (suggested by the fact he is on foot, his large shield, absence of a bow and his clothing; no trousers apparent!) I think he is meant to be barefoot here, since usually the boots are rather obvious. If we were feeling particularly bold we might go as far as to presume this is not even a Turk, but one of the subject (Iranic speaking?) peoples under Khwarezmian rule.

Given that the Khwarezmian state emerged as a vassal of the Great Seljuqs, we should assume a large continuity in dress, armour and perhaps hairstyles between them

We see also what I assume is a regular hairstyle in the Seljuq/Khwarezmian period; the hair coming down in shoulder-length, or longer, strands that framed the head. Hairstyles often have political significance; the Mongolian "nuqula" hair style we have many depictions of, and accounts of them forcing their new subjects to shave their heads as a mark of political allegiance. The Qing Dynasty famously did this during their rule over China, forcing the Chinese to shave their heads into the iconic Manchu queue. Unfortunately in our Seljuq/Khwarezmian example here, the depictions are not quite clear enough in really judge precisely what is being shown, and how much of it is supposed to be a hat, for example.

youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

JALAL AL-DIN IN BATTLE WITH THE MONGOLS AT PARWAN, 1221

After Mongol prince Shigi Qutuqu began to withdraw during the battle of Parwan, Khwarezm-shah Jalal al-Din Mingburnu ordered his men to mount up and pursue. But Shigi Qutuqu pulled them into a feigned retreat, for he quickly had his Mongol army turned about and counterattack Jalal al-Din's advancing troops. This stopped the momentum of Jalal al-Din's army, and according to one of our main sources for the battle, this nearly caused Jalal's army to rout as 500 Khwarezmian troops were slain in quick order. Fortunately for them, Jalal al-Din's personal courage once again turned the tide: in Juvaini's account, Jalal al-Din personally led a new charge which rallied his troops, and caused them to chase the Mongols from the field.

Unfortunately for Jalal al-Din, in victory he found defeat for his resistance. His generals began to fight over the loot from Shigi Qutuqu's army, and despite Jalal al-Din's efforts to rein them in, the effort was fruitless. In short order, Ighraq, commander of the Khalaj and Turkmen in Jalal al-Din's army, abandoned the Khwarezmian cause. At the same time, Chinggis Khan himself was calling back all his forces to bring his full weight against Jalal al-Din's now halved-force. Jalal sought to wtihdrawal through India, but his army was caught and destroyed at the Indus River in November 1221. Though Jalal al-Din escaped (famously riding his horse off a cliff into the Indus River!) and lived to continue to be a nuisance to the Mongols, the defeat at the Indus marked the high point of his resistance to the Mongols.

I talk about Mongol heavy cavalry in the war against Khwarezm in my latest video:

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Parwan, September 1221; This was Khwarezm-shah Jalal al-Din Mingburnu's victory over a Mongol army under Shigi Qutuqu, the adopted son/brother of Chinggis Khan. Jalal al-Din was a son of the late Khwarezm-shah Muhammad II, and had fled into what is now Afghanistan, rallying whoever he could for a resistance against the Mongols. After defeating a small vanguard force, Chinggis Khan ordered Shigi Qutuqu to bring Jalal al-Din to heel.

Jalal al-Din brought a substantially larger army than Shigi Qutuqu; according to Juvaini, one of our main sources for the battle, Jalal al-Din had 60-70,000 men compared to Shigi's 30,000. Jalal al-Din's army was of greatly varied background; Jalal al-Din commanded the centre, a mix of Khwarezmian and Ghuri troops; on his left wing, Amin Malik commanded a large Qipchaq contingent, and his right wind under Saif al-Din Ighraq was a host of Khalaj and Turkmen.

Despite the fact that much of the army usually fought from horseback, Jalal al-Din ordered them to fight dismounted. We might suspect this was the best way to reduce the chance of troops breaking rank to pursue the Mongols into feigned retreats, or to flee before them, while ensuring that his archer's had stable platforms with to pick their shots.

The battle took place over two days, with Jalal al-Din's men holding their ground; on the night of the first day, Shigi Qutuqu placed dummies on horseback in an effort to frighten the Khwarezmians into thinking Mongol reinforcements had arrived. The ploy nearly worked, but Jalal al-Din was made of sterner stuff and kept his commanders in line. Another fierce day of fighting followed, and Shigi Qutuqu sent an elite cavalry force to charge against the Khwarezmian left flank. Here, Jalal al-Din's archers, through volley after volley, broke the Mongol charge, and soon after Shigi Qutuqu took his army from the field.

I talk about Mongol heavy cavalry in the war against Khwarezm in my latest video:

youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

DISMOUNTED MONGOL ARCHERS

While it is absolutely true that the Mongols and all warriors of the Eurasian steppe preferred to fight from horseback, fighting from foot was done when necessary.

We see, for instance, in accounts of Mongol wars against the Mamluks, against the Jin and Song Dynasties, and even against the King of Pagan (today's Myanmar) Mongols dismounting to meet different tasks.

Song Dynasty envoys Peng Daya and Xu Ting wrote how one of the tactics the Mongol vanguard employed was to read towards the enemy, dismounted and then shoot at them; they were protected by circular shields strapped to the shoulders which protected them which they did this. It seems the idea was for greater accuracy and more precise shots, while also not making their horses a target for the enemy.

Similarly, when battling King Narathihapade of Pagan during his invasion of Yuan-ruled Yunnan, the Burmese elephants frightened the Mongols' horses. The Yuan commander ordered his men to dismount to shoot at the elephants, with their horses left in the security of the tree line. Here, the horses were unreliable platforms to accurately shoot from.

Against the Mamluks, towards the close of some battles the Mongol dismounted; Reuven Amitai-Preiss interpreted this as the Mongols' signalling their willingness to fight to the death, the exhausted horses now reduced to impromptu-barriers against the Mamluks.

You can learn more about other Mongol cavalry tactics in my latest video series;

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE MONGOL WOMAN WARRIOR AT MARAGHA, 1221

Ibn al-Athir is one of our key sources on the Mongol invasion of the Khwarezmian Empire. Writing in the 1220s in Mosul, northern Iraq, he was not an eyewitness to the invasion, but was a contemporary who received almost daily reports of Mongol movements and all manner of rumours.

He reports for us a short tale of a Mongol woman who partook in the sack of Maragha in 1221:

"I was told that a Tatar woman entered a house and killed several of its inhabitants, who thought that she was a man. She put down her arms and armour and - there was a woman! A man whom she had taken prisoner killed her." (Ibn al-Athir/D.S. Richards, vol. III, pg. 378.

We have no other clues to the identity of this woman, or if this is anything more than a rumour. A few things broadly support it though;

1) evidently, this woman was so well-armoured that it covered most of her body. Maragha was sacked by Jebe and Subedei; Jebe is in other sources like Zhao Gong (writing around 1221, almost exactly contemporary to the event) noted as "supervising Chinggis' heaviest troops," and was often left in charge of the heavily-armoured vanguard (manglai).

2) In general, the sources note that well-armoured Mongols were the wealthier parts of the army. When Mongol women are noted taking part in combat in some form in these sources, they are almost all Chinggisid princesses and other high-ranking women (Qutulun of course being the most famous example). It seems a privilege allowed to elite women, and it would support her also affording good equipment that almost entirely covered her.

Are we any closer to identifying her? No. If the story is even true (which it might not be!), we might suspect this was a woman of some relative status; not high enough that she would be reported as missing in a chronicle like Juvaini's, but perhaps a daughter of some Noyan who accompanied Jebe in his pursuit of Muhammad Khwarezmshah? As the Mongols would say, only Tengri knows.

I talk about Mongol heavy cavalry in the war against Khwarezm in my latest video:

youtube

#mongol empire#chinggis khan#genghis khan#khwarezm#women#female warrior#maragha#jebe#subutai#subedei#slay queen#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horse archery and heavy cavalry

While many tend to associate heavily armoured cavalry with tactics similar to Europe in that they are solely lancers, meant to charge into enemy formations and break them, in most of the world heavy cavalry didn't tend to serve solely this role. In essentially all of Asia heavy cavalry tended to be equipped with bows and served the same role as more lightly armoured horse archers while also being able to double as shock cavalry when the situation called for it due to their heavier equipment. These tactics were also adopted in North Africa, due to direct influence from the Turkic slave soldiers in use by the Islamic caliphates.

Of course many people do tend to associate horse archery with lighter cavalry and this is understandable as most horse archers did tend to be more lightly equipped in the steppe armies. But this isn't because they're horse archers, but rather the opposite. Because it was the default for cavalry to be archers, and when one is lightly armoured the best role to serve would be that of a horse archer. However by no means does horse archery require lightly armoured troops.

One specific way of utilizing heavy cavalry, popular all across central and west Asia though by no means limited to it, would be to equip heavy cavalry with lances in addition to their bows. The most famous users of this tactic would probably be the Mongols which made very liberal and effective use of their heavy cavalry in this manner. The cavalry would serve the regular horse archer role at first - harrassing the enemy at range - but when the situation called for it they'd swap to their lances and charge into the weary enemy ranks. If the enemy didn't break immediately (which they often did) they'd pull back, regroup and charge again.

This might then raise the question in some of you which is - how does one carry both a bow and a lance at the same time? Luckily for us, we have got sources for this. Below is a depiction from an early 14th century Ilkhanate manuscript, depicting the lance tied around the foot and arm to leave the hands free for bow- or indeed in this case sword - usage.

Another source for how to hold a lance while using a bow on horseback can be found in the Silahşorname by the late 15th century Ottoman author, Firdevsî-i Rûmî. The translation below was done by a friend of mine: "The second way is that if you wish to shoot arrows while on top of a running horse, whether it be in battle against an enemy or other places or in hunting, then it’s necessary to secure the lance between the strap of the right stirrup and the horse’s chest while making the horse run. That is to say, put the lance between the strap of the right stirrup and the horse’s chest and tuck its blade high up. As in tuck the lance into your right elbow and have the blade of the lance behind you so that it stays secure. And after that, your horse can run and you can make your shot. Shooting arrows in this way is the legacy of Behram-i Gur, who was the sultan of Persia, he was a hunter and an archer."

The attribution of this technique to the 5th century Behram-i Gur is definitely a fabrication by the author of the book, no doubt to mythicise the usage of the weaponry in this manner. regardless, the technique mentioned is pretty interesting. While there's scores more to say about this topic I think leaving it here for this time is good enough. I will however leave you with a video series below which is an extremely well researched overview on heavy cavalry in the Mongol armies, and definitely a mush watch if you have any interest in this topic.

youtube

77 notes

·

View notes