Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

youtube

Cloud Rhetoric - How does Thaksin Shinawatra manage to remain a populist actor on Twitter despite being exiled from Thailand?

In this podcast, I breakdown Thaksin Shinawatra’s rise as a populist in Thailand, and his continuing legacy that exists on social media, particularly Twitter, even after being removed by the Thai military in 2006 and remains to this day in self-exile. The phenomenon of a highly captivating political leader being able to broadcast his rhetoric to millions of people in Thailand despite the fact that he was removed because of his rhetoric is a fascinating conundrum, and that enigma is tackled in the podcast.

Thai Enquirer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ynwx699SNgA&t=11s

Twitter’s help page

https://www.google.com/url?q=https://help.twitter.com/en/managing-your-account/about-twitter-verified-accounts&sa=D&source=editors&ust=1620344884959000&usg=AOvVaw0N9gI8QINgfJIZ0Pt_tgTO

The Bangkok Post

https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1651140/wisesight-social-media-weighed-in-on-election

Canovan

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

Mudde and Kaltwasser

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Populism/KHquDQAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

The New York Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/30/world/asia/thaksin-shinawatra-of-thailand-wields-influence-from-afar.html

Stratfor Global Intelligence

https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/attach/26/26025_S-WEEKLY%20110203%20for%20fact%20check%20SN%20and%20MP%20comments.doc

The Nation Thailand

https://www.nationthailand.com/news/30402941

The Financial Times

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rMbJQ2_bHaE&t=19s

The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/21/thailand-protests-court-orders-news-outlet-to-close-as-pm-accuses-it-of-inciting-unrest

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Reluctant Populists: Learning Populism in Thailand” - When Legend Becomes Fact

(Hofman, Helene. “Thaksin Shinawatra, Thailand's ex PM, addresses rally in Cambodia”. The World, 14 April 2012, https://www.pri.org/stories/2012-04-14/thaksin-shinawatra-thailands-ex-pm-addresses-rally-cambodia)

This academic article, titled “Reluctant populists: Learning populism in Thailand” and written by Kevin Hewison, challenges the broadly accepted nomenclature of Thaksin Shinawatra as a populist. Hewison is a long-time political scientist and professor at numerous universities. In this study, he argues that “Thaksin was made a populist by elite opposition, military coup and the political demands by the red shirt mass movement wanting social and economic equality underpinned by electoral representation.” (Hewison 2017) His research was found upon a vast array of resources primarily centered around populism in Asia.

The general ideas of populism and how it is commonly interpreted are backed by the text of Mudde and Kaltwasser. With regards to Thaksin, they note that Thaksin was an insider populist, ones “who come from within the heart of the political elite.” (Mudde and Kaltwasser 76). Just as they also cited, populists are often thought of as rebellious outsiders in the political system, and populist leaders exploit that attribute for their own growth. Because of Thaksin beliefs and policies during his time as Prime Minister, consisting of pushing human and civil rights amongst all people in Thailand, he represents an idealistic, left-wing style of populism, which Canovan describes as ones who “claim legitimacy on the grounds that they speak for the people: that is to say, they claim to represent the democratic sovereign, not a sectional interest such as an economic class.” (Canovan 4) According to Hewison, Thaksin as a populist is not all what it seems to be.

For Thaksinomics, the title references Thaksin’s economic plan, “his brand of populism is short-sighted. It increases the population's dependence on the state and threatens to take Thailand down an unsustainable Latin American-style dead end.” (Warr 2011) The economic element tends to get lost in the discussion surrounding populism and its relationship to society, perhaps because it’s not as viscerally engaging to argue about as social and political issues. When economic policy is glossed over, populists like Thaksin get credit for changing the infrastructure and authoritarians like General Prayut-Chan-ocha in this case, are ignored for their deemed “populist” policies. For example, “Prayut and his technocratic team” had initially designed a welfare card, which would help support people in poverty, heading into the 2019 Thai election, “would have done well to introduce the welfare card earlier in their terms, as it may prove one of his few selling points among the provincial poor this election.” (Janssen 2019)

Hewison writes about the idea of speaking as a populist. It takes a certain level of commitment to serve as a populist. Even Thaksin, coming from a family of royalty, was not initially interested in channeling populist rhetoric. Hewison notes that Thaksin becoming a populist was “slow to develop.” There is a chance that Thaksin was just a great persuader. “Thaksin, by employing a populist discourse (he was not a populist politician from the beginning), managed to convince the majority of society, especially the poor and lower classes, to follow him faithfully.” (Markou 2015) This is what Hewison points to when Thaksin took the opportunity to appeal to the red shirt mass movement, Thai’s populist movement that has carried over to the Pheu Thai party, the nation’s current populist party.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the article is that Thaksin took control of Thailand during a vulnerable period. Hewison writes “the potential appeal of populism grew during and immediately following the economic crisis,” along with the authoritarian makeup of the government and corruption of elections. “Thaksin’s popularity threatened the palace and the military leadership of the country, who aspired to total control of the political landscape.” (Markou 2016) The layout of Thailand at the time enabled “people vs. elites” narrative.

As the title of the article alludes to, Hewison refers to Thaksin as a “reluctant populist.” In terms of his legacy, history and complementary legend-making won’t tell the whole story of Thaksin: that he was a royal insider and a pragmatist with the country’s economics. Ultimately, what we will remember is Thaksin’s impact on Thailand and populism in general. “As we have learned, all governments -- elected or not -- have resorted to populism, with the help directed at the poor, even though it is not a long-term measure that can do away with the root cause of poverty. But it can at least can ease their financial plight, albeit temporarily.” (Chantanusornsiri 2018) Subjectively speaking, I would claim that Thaksin, based on what we learned about populists this semester, is not a true populist in our current context. Nowadays, no politician is going to campaign on the grounds that they are not “for the people.” That sentiment is not enough to satisfy a leader as a populist. For the most part, Thaksin merely vowed to fight for the people in an authoritarian nation. The divisive and fascist rhetoric we saw in right-wing populists throughout the semester was not evident with Thaksin.

This kind of critical thinking and revisionist history is why this article is effective. It explains the phenomenon of legend-making with elected leaders.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bad Students - An Education in Democracy

(Phasuk, Sunai. “Thailand’s ‘Bad Students’ are Rising Up for Democracy and Change.” Reuters, 17 Sept 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/17/thailands-bad-students-are-rising-democracy-and-change)

In Thailand, a group of pro-democracy adolescents have emerged over the past few months. The “Bad Students” are demanding a better education and a better form of rule in their country.

Youth-led demonstrations calling for more freedoms have emerged over the past summer, and the organized Bad Students movement began in August 2020. (Bangkok Post) The issues at hand for the Bad Students and other protesters alike are evident, especially in regards with the Thai public school system, which is run with as much freedom of expression as one would expect from a military run nation. Widespread problems among schools include government slanted textbooks, insufficient materials and educators, gender inequality, corporal punishment, and little to no toleronce on freedom of thought. (Bangkok Post)

What makes the Bad Students stand out is their approach and tonality as a political activist group. In a sense, they make their demonstrations an art of theater. On a Saturday night in November, the group stormed downton Bangkok, with many protesters dressed in T-Rex costumes to signify the current government regime as “dinosaurs.” “They are stuck in tradition. They’re conservative, old-fashioned and refuse to change. Their time is up, they must go and open the way to other people who are more competent,” said one demonstrator, referring to Thai rulers, as other Bad Students danced along to anti-government rap songs in the streets. (VOA News) They demanded the resignation of the country’s Minister of Education, and formally sent a petition to the school. (Kuhakan 2020) The group also has big picture goals that they hope to accomplish with regards to the entire nation, stating that “their campaign for school reform is part of the wider political campaign to end authoritarian rule in Thailand.” (Phasuk 2020) Going the extra lengths with these theatrics appears as a purposeful tactic to spread recognition and attention so that others can listen to what they have to say about national reformation.

If they’re not a sensation yet, the Bad Students certainly have the makeup of a movement that could rapidly catch on at a global level. Compared to a political party, a social movement like the Bad Students is more captivating and polarizing within the general public. “Social movements are informal networks that bring together people with a shared identity and a common opponent who engage in noninstitutionalized collective action to pursue a goal,” (Mudde & Kaltwasser, pg 44) which suggests that they are rooted in authenticity and earnestness, something deemed not found in politics. Within a particular movement, “the different people and parties called ‘populist’ enjoy family resemblances of one to the other.” (Judis, pg 1) This adds a personal element to the cause for social/political change.

On the other hand, social movements are unpredictable and flat out fail to react to issues at a vulnerable state. It should be noted that, during the 2006 government coup of populist icon Thaksin Shinawatra, “there was very little opposition to this coup from social movement organizations, even as the coup regime began to dismantle numerous TRT programs” (Glassman, Park, & Choi 2008) Social movements tend to be more reactive, rather than proactive to an issue. For this reason, the legitimacy of social movements like the Bad Students can be questioned. Do these kids have a solution to their problems, or are they just marching the streets of Bangkok because they are, as Howard Beale said in Network, mad as hell and need an opportunity to vent their frustrations. Either way, the Bad Students are not going to take it anymore.

0 notes

Text

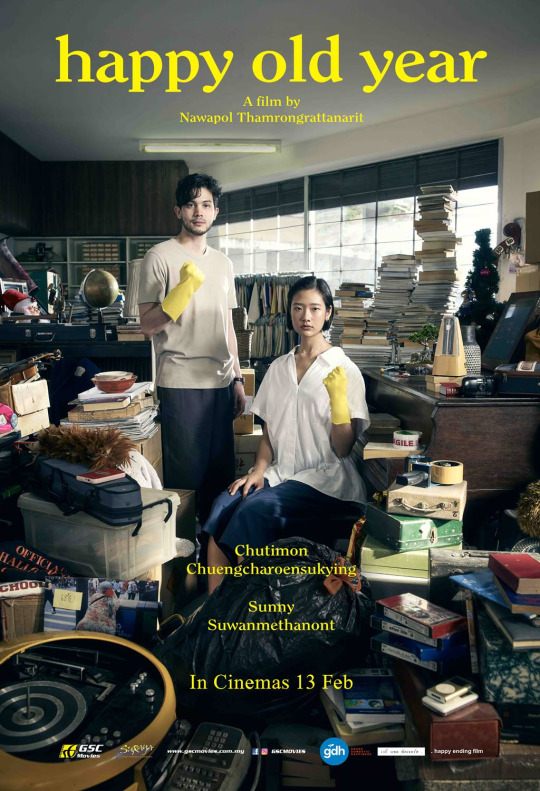

HAPPY OLD YEAR - Nothing Without Meaning

Happy Old Year is a 2019 Thai drama film directed by Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit. It is a story about a woman who vows to clean up her home, which includes getting rid of all of her deemed unnecessary objects. While decluttering, she finds that these items trigger memories of her past, especially those left behind by her old boyfriend.

The audience is not entirely sure why Jean, the main character, is embarking on this reorganization towards minimalism journey, but the sentiment can be tied to populist values. In a sense, minimalism in culture and lifestyle is a form of populism. Both movements try to go back to simpler, more efficient roots. They believe that all problems can be resolved with simplicity. At their core, populists believe that “tends to play a positive role in the promotion of an electoral or minimal democracy, but a negative role when it comes to fostering the development of a full-fledged liberal democratic regime,” so there is a give and take to this philosophy. (Mudde and Kaltwasser, pg 96) Just as populist actors convince themselves that pure common sense can serve as the perfect political system, Jean learns throughout the film that minimalism will not heal all emotional wounds from the past.

The digital mobilization of populism has been previously noted. Jean’s decluttering process is predicated on technological evolution in the film. She sees no use in physical books. In exchange for buying a book about interior decorating, she takes pictures of specific pages in the bookstore. She notes at one point, “publishing is dead.” The old ways reflect on what we did wrong in the past. For Jean, she is brought back to unfortunate memories of her old relationship.

I couldn’t help but draw parallels with the character’s motivation to be minimalist with materialism in Thailand. The film’s tone of material objects suggests that there is a subconscious disdain for hoarding high-priced and glamorous property amongst the nation. A study showed that family dynamics and relationships impact a young Thai person’s relationship with consumer items. (Nguyen, Moschis, Shannon, 2009) It appears that materialism represents social status. (Sangkhawasi & Johri 2007) In this case, Happy Old Year is perhaps a counterculture piece of art. In fact, the country’s heavy consumer tendencies have hurt Thailand as a whole, with a debt-to-income ratio of 121% in 2014. (Tulyanond 2017) Depending on the film’s connection with the audience, it can speak to a pocket of often unnoticed society or be disregarded as a strange phenomenon. The film’s anti-materialistic messages are either populist or anti-populist, considering the various definitions of populism. By the word alone, populism in Thailand coincides with materialism. That’s what the majority of people follow. Many times, however, populism is weaponized for a group that is under the radar, which in this case is the anti-materialism movement. If anything, a redistribution of items and resources would be a populist issue.

The film is a well-rounded story of an individual unsure of where to go in life. This is not an overtly political film by any means. Minimalism represents Jean’s psychological process: cleaning out and trying to start over. Ultimately, Happy Old Year is driven off of an “intimate atmosphere that would let us experience the emotions along with the characters. And those are precisely the characters that deserve particular attention and credit.” (Karpińska 2020) As we learn by the end of the story, the film is neither materialistic or anti-materialistic. It’s about finding out for yourself what has value and what doesn’t.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Call for the Pheu Thai Party

Dear Pheu Thai Party,

I appreciate your party’s commitment and dedication to populist policies and rights. I deeply respect the mobilization of the party over the past few years. Holding the most seats in the Senate is a great milestone for populism worldwide. Your formation, based on the foundational populist movements of the great Thaksin Shinawatra, was very much so needed in Thailand, where civil liberties dried up under the regime of the still-standing military junta. Your retaliation against the suppression of peaceful demonstrations from the military police is inspiring, I should note. I think your party is responsible for the long-awaited fair election that was held in 2019, after years of military corruption and manipulation. (Lertchoosakul 2020) Standing up for the symbolic “people” against the tyrannical establishment “elite” has been a mainstay for populism. While that fight is important, the populist movement has room to expand.

Tourism, previously a source of income and pride for the nation of Thailand, was curtailed after the 2014 coup. I ask that the Pheu Thai Party allocate its resources and attention towards the cause of international travel during the COVID-19 outbreak. “The people” that Pheu Thai should represent are being mistreated through harsh “safety” protocols, as this open letter written to The Thaiger describes. “It seems that we are being completely ignored and are considered to be nothing more than ‘tourists’ to those in charge.” This writer states, referring to the country’s strict policies in allowing travelers to reenter the country.

Being that the outbreak of COVID-19 is rooted in uncertainty regarding its spread and effect on people, governments across the world have taken advantage of their vulnerable citizens. In Thailand, anyone from a foreign land is being prohibited from entering back into the country, even ones who live in Thailand, including the author of the open letter. “Thailand is our home and after 4 months of living in hotel rooms abroad, we just want to come home.” (The Thaiger)

I ask the Pheu Thai party to direct their attention to this because it is their duty as populists to do so. While the nation has done their part in keeping the people safe from COVID-19, with only 92 deaths since the start of the pandemic, (WHO) Thailand has overlooked the other aspect of health: the psychological impacts. The party has spoken out about the lack of sufficient funds given to those affected by COVID, arguing that “the state helps shoulder 50%-60% of the employers’ payrolls, to keep them employed for six months, instead of firing them.” (Thai PBS World) The quarantine mandates and international lockdowns are hurting people equally.

One of the core policies of Pheu Thai when they entered politics was boosting tourism. (Thaitrakulpanich 2019) The tourist industry of Thailand is considered one of the best in the world, due to the rich culture, accessible infrastructure, comfortable climate, popular food, and much more. (The Viking Abroad) Local tourism businesses have been bleeding money during the pandemic. This is an industry that stabilizes the economy and expands the level of international reverence. The more people that travel to Thailand, the more connected Thailand becomes with the world.

This issue that I speak of is an immediate crisis, and I believe that Pheu Thai focuses too heavily on long-term issues that require more action than just mobilization. Populism can be defined “as an emphasis on public expenditures that win political support through poorly evaluated large public projects and short-term redistributions towards targeted groups.” (Warr & Moore 2014) The party’s social media presence grows larger by the day, so if they could rally a movement in support of ending these strict laws against the people of Thai and other foreigners from entering the nation, they can truly show that they represent the people.

Sincerely,

The people of Thailand

0 notes

Text

Coup D'état of Thailand of 2014: Government Rule Disrupts Populist Movement

(Pitman, Todd. Doksone, Thanyarat. “Thai troops detain gov't minister who blasted coup.” Stars and Stripes, 27 May 2014, https://www.stripes.com/news/pacific/thai-troops-detain-gov-t-minister-who-blasted-coup-1.285624)

Thailand has experienced a fair share of coups, 12 since 1932 to be exact, (Taylor 2014), and the most recent coup d'état in 2014 has laid the groundwork for the nation’s current populist movement. On May 22, 2014, Thailand’s government military seized control of the nation from Prime Minister Niwatthamrong Boonsongpaisan. Military leader General Prayuth Chan-ocha established the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), a military junta to actively govern Thailand.

The turmoil leading to the 2014 coup originate back to 2006, when populist icon Thaksin Shinawatra was removed from his seat as Prime Minister by the military. Political demonstrations occurred regularly by Thaksin’s followers. Widespread protests in Bangkok in 2010 faced constant violent suppression from the military, resulting in around 90 deaths. (Shoichet 2014) A year prior to the coup, a movement to grant amnesty of Thaksin took place, led by Thaksin’s sister, Yingluck Shinawatra. Class conflict ensued between the “Yellow Shirts”, the urban elites who vow to remove the Thaksin family from Thai politics for good, and the “Red Shirts”, the Thai populists. A week before the coup, a violent clash between the two parties resulted in three Yellow Shirt protesters killed and 23 injured.

During the coup on May 22, 2014, 25 prominent politicians, notably those of anti-government ideology, were detained by the military. As the junta seized control throughout Bangkok, generals issued new orders, including the “termination” of most of the nation’s Constitution and imposing a curfew, banning schools and gatherings of more than five people. (Fuller 2014) Soldiers roamed the streets of the nation’s capital, forcing both parties of demonstrators to shelter. By the visual alone, Thailand was under a military state. (VICE News) As a result of the government takeover, the media could no longer be legitimately independent. Televisions stations were immediately shut down and replaced with state propaganda.

The constant power disruption has left a mark on Thailand on many fronts, and one of the long-term effects comes from the nation’s dwindling reputation as a financially prosperous tourist attraction. After the 2014 coup, “it has made headlines for the many attempts by antigovernment protesters to suspend democracy, a jarring contrast with its open, cosmopolitan image.” (Fuller 2014) As covered in the Media Landscape and Special Issue briefs, freedom of expression from the media and citizens of Thailand has been compromised since the coup. The country did not hold an election until March of 2019.

Due to the class battle between Red Shirts and Yellow Shirts, Thailand was very much so a divided nation. The threat of that struggle reaching the point of chaos triggered the military to take total control of the nation. Over time, the current second wave populism of Thailand would take over the culture, in which “the pure people” were pitted against “the corrupt elite”, as this struggle “was framed as against the ‘political class’ and the state. The alleged corrupt elite was depicted as those political actors who favored the existence of a strong state and opposed the development of a free market.” (Mudde & Kaltwasser 31)

Since the conflict amounted in violence in certain instances, the government mediating the situation is called for. Instead, the military rule took advantage of a divided nation in a result that satisfied no one: an authoritarian regime. The people of Thailand were promised that control under the NCPO was the benefit of the commonwealth, for reasons of safety and restoring democracy. Because they deemed Thaksin and his supporters corrupt and violent, respectively, the coup was credited as “legitimate.” (Chachavalpongpun 2014) In reality, This command of power was “a royal coup, designed to reverse the political trend towards democracy in Thailand back to royal political dominance.” (Chachavalpongpun 2014) Universally, the government addressing an immediate issue with tyrannical-like solutions is the downfall of democracy. Even as populist rhetoric rises with the Pheu Thai party and other activist groups, the movement to expand democracy in Thailand are faced with the obstacle that “populist campaigns and parties, by nature, point to problems through demands that are unlikely to be realised in the present political circumstance.” (Judis 3) As Thaksin Shinawatra showed, it takes one powerful and captivating leader to take control.

0 notes

Text

Special Issue: Violations of Freedom of Expression

(Maida, Adam. “Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Thailand.” Human Rights Watch, 24 Oct. 2019, www.hrw.org/report/2019/10/24/speak-out-dangerous/criminalization-peaceful-expression-thailand)

In Thailand, government suppression of free speech is a longstanding issue. The monarchy and government of Thailand cracks down on citizens who publicly criticize them, both in outdoor demonstration and on the Internet.

In February 2019, the Cybersecurity Law and Data Protection Act were passed, which permitted the government to increase online surveillance and censorship. “The laws allowed sweeping government surveillance without basic legal safeguards.” (Amnesty International) This law, along with the existing restrictions on anti-government speech, affects politicians, academics, factory workers, and activists who think for themselves. The demonstrations and protests that are being silenced throughout Thailand involve matters of increasing democracy and a decentralized rule in the country.

Prime Minister Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha and the military junta of Thailand, named the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), exists to “intimidate and silence opposition to its rule through harassing criminal charges, abusive prosecutions, arbitrary closure of tv, radio, and internet stations, and censorship of online content.” (Maida 2019) “At least 929 people have been summoned by the authorities to participate in ‘attitude adjustment’ sessions”, which is a mandated enforcement of following along with everything the government does.

There are countless instances of government prosecution of the people of Thailand, including of activists and opposing politicians. Activist Sombat Boongarmanong was detained at an unknown location and faced up to 14 years in prison after criticizing the government on social media, as well as encouraging people to gather in the streets in protest. (Maida 2019) In addition, if you speak about the torture you received from junta soldiers, like human rights activist Ismae Tae did on public television, you will be charged with defamation. Thailand’s main populist actor, the Pheu Thai party, is right in the middle of the government’s suppression of speech, with many party members getting summoned for attitude adjustment hearings along with charges for violating online expression laws.

The list of speech laws and examples of government suppression of the people is endless. Innate human rights violations show no sign of slowing down. In the COVID-19 era, the government is using the virus as an excuse to terminate peaceful demonstrations out in the streets. (Human Rights Watch) Just in the past few weeks, four prominent activists for democracy were arrested without bail due to disparaging the Thai monarchy. (Human Rights Watch) The lack of free expression is as prevalent as ever in today. On March 24, 2020, while declaring a state of emergency, Prime Minister Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha said “After a state of emergency is announced everyone must be careful about social media misinformation … the media and all of those who use social media to distort information will be scrutinized.” This is ultimately just a way to cover-up for the fact that any dissenting opinions on the country’s COVID response are banned. (Human Rights Watch)

Many people most likely take the right to freely express your views in public settings for granted, but when compared to the struggles that the people of Thailand face from their government, they truly are privileged. The beacon of hope in this civil rights struggle is in the courts of Thailand. Cases brought upon journalists and activists from the government are often dismissed by the courts and “found in one case that the defendants had been peacefully exercising their constitutionally-guaranteed rights.” (Amnesty International) The court system can only accomplish so much though, as the military junta shows no signs of easing power.

A concept that tends to get lost upon populism is the urgency to think freely and to read between the lines. This is the best solution to combat the state-regulated media in Thailand. Even with the wide range of communication influence the Internet has, it “as a technology permits the free flow of idea and information the legal culture of censorship remains intact. This kind of thinking is unhealthy to a democracy in the making….In addition, the media learn to practice self-censorship in a bid to accommodate to legal state control.” (Siriyuvasak 2007) A human rights attorney from Thai wrote a letter to Harvard Law, claiming that “The illegitimacy of the government and their continuing oppression elude the majority of Thai people, most of whom subscribe mainly to the national news program. To hold the government accountable and denounce the use of force, its illegitimacy must be widely known.” (Thanaboonchai 2020) The only way to change the system is for the people to change how they were wired to think, by not accepting this kind of suppressed media.

0 notes

Text

Media in Thailand, Authoritarian Journalism, Pheu Thai is the Way of the Future

Sattaburuth, Aekarach. “ New Pheu Thai team reaching out to young people.” Bangkok Post, 1 Oct. 2020, www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/politics/1994963/new-pheu-thai-team-reaching-out-to-young-people

Overview of the Media Landscape

The most powerful media companies in Thailand consist of the Bangkok Post and Thairath for print, Thai TV3 and BBTV Channel 7 for television, Radio Thailand and MCOT Radio Network for radio, and MCOT online news for digital. The television and radio media is dominantly controlled by the government and military. However, according to BBC News, “the media are free to criticise government policies, and cover instances of corruption and human rights abuses.” Journalists are forced to be careful around reporting harmful news involving the royal family and military. (BBC News) A new cybersecurity law passed in February 2019 restricted free speech rights, allowing for executive prosecution. (Reporters Without Borders) The print media is largely privately operated.

Internet accessibility for citizens of Thailand is currently not up to the standards of the rest of the world. According to the Freedom House, Thailand scored a 35/100 on their “Internet Freedom Score” (Freedom House), which is based on accessibility, government censorship, and user rights violations. However, the speed and price of broadband Internet service has been gradually improving over the last few years.

Press Freedom and Challenges to Journalism

Out of the 180 countries listed on the RSF Press Freedom Index, Thailand was ranked 140th in 2020. Criticisms of the government are subject to harsh prosecution, especially in the digital field, including in instance in December 2019 where a journalist was sentenced to two years in prison for reporting on inhumane conditions of migrant workers through Twitter. (Reporters Without Borders) Covering the March 2019 election was difficult for independent journalists, as the standing military rule, the National Council for Peace and Order, used censorship, intimidation, and legal action to suppress the news that hurt the nation’s monarchy. The NCPO used the defense of protecting “national security” as a reason for the suppression. (Freedom House 2020)

Media and Populism

The main populist actor in Thailand is the Pheu Thai party, which holds the most seats in the country’s House of Representatives. The party is active on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Their profile, which has over 185K followers, informs the public on the latest civil and human rights issues in Thailand and the stances the collective party takes on them. This is how the party can raise awareness to vital populist issues, including a recent attack on demonstrators by the police. The profile commonly retweets political demonstrations of the people and other populist actors of the party. The account has a visual appeal, with graphs, charts, and recruitment posters displaying data and upcoming events.

New Mandela cites that Thailand is a “top 5” nation of the world in terms of social media activeness. Perhaps the biggest reason why the Pheu Thai party did so well in the March 2019 election was because its supporters self-mobilized on Facebook. “Each time Pheu Thai made a post, the party garnered nearly 30,000 reactions from fans. This rate of engagement is 450% higher than the second most engaged party, the Future Forward Party, even though the latter has more overall page likes.” (Sinpeng 2019) The party may not have the most power or support in numbers, but their base is the most loyal and passionate.

Populism and social media, based on what we idealize about the two properties, are made for each other. Populism is meant to speak for those lacking a voice, and social media is a platform that connects everyone of any demographic. Political scientists have noted that “studying political engagement through analysis of social media data allows scholars to better understand the political engagement of millions of people by examining individuals' views on politics in their own voices.” (Nyblade, B., O'Mahony, A., & Sinpeng, A. 2015) The buzzwords often paired with social media activity, such as “viral” and “trending”, could easily be used to measure a populist issue. To get an issue like journalistic freedom trending within Thailand would be a huge benefit in today’s digitally driven political society.

0 notes

Text

Populism in Thailand: Rises with Thaksin, Falls with Coups

(Sinpeng, Aim. “Pheu Thai Won the Facebook Election in Thailand.” New Mandala, 29 Mar. 2019, ewmandala.org/pheu-thai-won-the-facebook-election-in-thailand/.)

Political History and Current Populist Movement

Thailand is currently controlled under a constitutional monarchy. Up until 1932, the nation was ruled under a monarchy. Since then, the monarch is in a figurehead position, with a legislative parliament possessing true control of the nation. Numerous successful and failed power coups have taken place in Thailand throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, both against the homegrown government and foreign conquerors. (Fact Monster).

Populism grew to prominence when Thaksin Shinawtra rose to power in 2001. He brought populist ideas and policies to Thai government for the first time in its history. Thaksin’s stances as a populist, including cheap health care, agrarian debt relief, and village funds compromised the established elite of Thailand, causing yet another coup of his throne in 2006. (Phongpaichit 2007)

As an op-ed headline for Nikkei Asia writes (Pesek 2019), Thailand cannot quit populism, no matter how many military coups are thrown in the movement’s face. In the 2019 general election, the Thaksin-linked party (Wongcha-um 2019), Pheu Thai, held most of the seats of the House of Representatives, but were unable to gain control due to an addition of newly formed parties that split the vote between the Pheu Thai, Democrat, and Bhumjaithai parties. The split in House seats was likely going to form a “coalition party between one big party and maybe two important, medium-sized parties.” (Tan 2019) This election was long awaited, as the nation had been under military rule since 2014.

Populist Leaders, Movements, Parties

The main populist party of Thailand, Pheu Thai, replaced the People’s Power Party, which was dissolved after the courts discovered widespread voter fraud within the party in 2008. The party is led by Sompong Amornwiwat. Currently, the Pheu Thai party holds the most seats in the House of Representatives. However, the party does not have the majority control. They are the core opposition party in the House. Instead, it serves in a coalition with the Democrat and Bhumjaithai parties.

Originally founded by populist icon Thaksin Shinawtra, Pheu Thai’s political positions are inspired by his beliefs. They support policies backing public and private interests, including increasing the minimum wage, expanding public healthcare, and strengthening private businesses. They also support tourism and farming. They are in favor of abolishing the military draft and lowering defense spending. (Thaitrakulpanich 2019) Mudde and Kaltwassar’s definition of populism claims “society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’” and attributes to the general will of the people. Fortunately, Pheu Thai does not fall for the trap of pitting everyday people against the elites, teaching a philosophy that the latter is always acting in the worst interest of the nation. Pheu Thai is populist on the merit that it cares about supporting all the different fields that make up a properly functioning society. Their policies appeal to the private and public level, along with economics and politics.

Challenges to rights-based Democracy

Thailand has recovered from a period that ended in 2019 in which citizens did not have the right to vote for government officials following a coup in 2014. During this time, Malay-Muslim insurgency occured in the southernmost provinces of Yala, Narathiwat, and Pattani. Other human rights violations included sex trafficking of minors, child labor, and discrimination of the disabled and minorities. This could explain how the populist Pheu Thai was able to rise in popularity. The early stages of the Thatskin government showed a lack of determination to fight for a separate media from the state. There was a court battle to remove control of electronic media from the government, but “the Thaksin government made no effort to end this jam, which meant all electronic media remained under the control of the government, army and Shinawatra family.” (Phongpaichit, P., & Baker, C. 2004).

Even post-2019 general election, the Thai government has demonstrated dictatorial behavior against dissenting speech, which have been common over the past few months, regarding more democracy and less police brutality. (Amnesty International) “Rights defenders face constant risk, harassment, and retaliatory lawsuits from government agencies and private companies.” (Thailand) Recently, censorship of peaceful rallies have been banned under the pretext of COVID-19 safety measures.

2 notes

·

View notes