Text

Time to infodump about the animals I'm supposedly a nerd about.

All pictures in this post are N. yvonneae, the southern ningaui (Image credit: Owen Lishmund)

The ningauis (in the genus Ningaui, if you can believe it) are a group of tiny dasyurid marsupials native to the arid and semi-arid regions of Australia. Smaller than their close dunnart relatives (very close, as I will explain later), and with broader hindfeet, ningauis were first documented by western science relatively recently by Australian mammal standards. Although some specimens had been collected previously, being haphazardly assigned to planigales (another genus of miniscule dasyurids), it wasn't until 1975 that the genus Ningaui was erected and its first two species were described - N. ridei, the Wongai ningaui, and N. timealeyi, the Pilbara ningaui. A third species, the southern ningaui (N. yvonneae), was named in 1983.

Oh, and in case you were wondering where the name "ningaui" comes from, it refers to tiny beings from Aboriginal mythology that come out at night, are covered in hair, have notably short feet and eat their food raw. Most of these traits are also shared by these little marsupials, hence why palaeontologist Mike Archer (the original author of the genus) found it to be a fitting name for them!

(Image credit: glandarius)

Ningauis are small - really small, some of the smallest land mammals in fact. With the tiniest individuals being only 5 cm long, not including the tail, they are about the same length as Australia's smallest native mammal, the long-tailed planigale. However, ningauis are significantly chunkier and therefore usually weigh a couple more grams, meaning planigales win in regards to all-around tininess. The very largest ningauis still only reach about 8 cm in length and 14 grams in weight.

What they lack in size they make up for in ferocity however, as they follow the typical dasyurid trend of becoming increasingly savage the smaller they get. Tasmanian devils, despite their reputation, are actually quite relaxed when handled - on the other end of the spectrum, ningauis, which are around a thousand times smaller than a devil, will try to murder you, your family and everyone you hold dear if they find themselves captured. But, despite their best efforts to chew the fingers off of every field mammalogist in inland Australia, they aren't very strong.

remorseless beasts (Image credit: Tina Gillespie & Miss.chelle.13)

These ferocious predators feed on a variety of different prey items, the majority of which are small invertebrates - in the case of the Wongai ningaui, they prefer prey that is less than a centimetre long. However, they will also go after larger prey, having epic duels with grasshoppers, spiders, centipedes and even small skinks which they subdue with a crushing bite to the back of the head. Unlike their dunnart relatives, the shorter, broader feet of ningauis allows them to climb into shrubs and grass clumps.

All ningaui species are extremely similar to one another, so much so that the Wongai ningaui and southern ningaui are almost externally indistinguishable and the Pilbara ningaui can only be told apart by looking at its foot pads, teat number and skull. However, they can usually be distinguished by distribution. The Pilbara ningaui is the most range restricted, being endemic to the central and western Pilbara region of western Australia. The southern ningaui occurs in three disjunct populations across the southern semi-arid zone, whilst the Wongai ningaui is distributed widely across much of the interior. All species show a strong preference for environments dominated by spinifex grass (Triodia), which they use as shelter.

A ningaui takes shelter amongst the spinifex (Image credit: Euan Moore)

In regards to how they are related to other dasyurids, ningauis fall in the tribe Sminthopsini together with the kultarr (Antechinomys laniger, another species I really need to cover sometime) and many species of dunnart (Sminthopsis). However, recent phylogenetic studies have consistently recovered both Antechinomys and Ningaui as being within the Sminthopsis lineage, meaning that both ningauis and the kultarr are, in essence, just weird dunnarts. With Sminthopsis as we currently understand it being highly paraphyletic, a revision of the genus is needed.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time to infodump about the animals I'm supposedly a nerd about.

All pictures in this post are N. yvonneae, the southern ningaui (Image credit: Owen Lishmund)

The ningauis (in the genus Ningaui, if you can believe it) are a group of tiny dasyurid marsupials native to the arid and semi-arid regions of Australia. Smaller than their close dunnart relatives (very close, as I will explain later), and with broader hindfeet, ningauis were first documented by western science relatively recently by Australian mammal standards. Although some specimens had been collected previously, being haphazardly assigned to planigales (another genus of miniscule dasyurids), it wasn't until 1975 that the genus Ningaui was erected and its first two species were described - N. ridei, the Wongai ningaui, and N. timealeyi, the Pilbara ningaui. A third species, the southern ningaui (N. yvonneae), was named in 1983.

Oh, and in case you were wondering where the name "ningaui" comes from, it refers to tiny beings from Aboriginal mythology that come out at night, are covered in hair, have notably short feet and eat their food raw. Most of these traits are also shared by these little marsupials, hence why palaeontologist Mike Archer (the original author of the genus) found it to be a fitting name for them!

(Image credit: glandarius)

Ningauis are small - really small, some of the smallest land mammals in fact. With the tiniest individuals being only 5 cm long, not including the tail, they are about the same length as Australia's smallest native mammal, the long-tailed planigale. However, ningauis are significantly chunkier and therefore usually weigh a couple more grams, meaning planigales win in regards to all-around tininess. The very largest ningauis still only reach about 8 cm in length and 14 grams in weight.

What they lack in size they make up for in ferocity however, as they follow the typical dasyurid trend of becoming increasingly savage the smaller they get. Tasmanian devils, despite their reputation, are actually quite relaxed when handled - on the other end of the spectrum, ningauis, which are around a thousand times smaller than a devil, will try to murder you, your family and everyone you hold dear if they find themselves captured. But, despite their best efforts to chew the fingers off of every field mammalogist in inland Australia, they aren't very strong.

remorseless beasts (Image credit: Tina Gillespie & Miss.chelle.13)

These ferocious predators feed on a variety of different prey items, the majority of which are small invertebrates - in the case of the Wongai ningaui, they prefer prey that is less than a centimetre long. However, they will also go after larger prey, having epic duels with grasshoppers, spiders, centipedes and even small skinks which they subdue with a crushing bite to the back of the head. Unlike their dunnart relatives, the shorter, broader feet of ningauis allows them to climb into shrubs and grass clumps.

All ningaui species are extremely similar to one another, so much so that the Wongai ningaui and southern ningaui are almost externally indistinguishable and the Pilbara ningaui can only be told apart by looking at its foot pads, teat number and skull. However, they can usually be distinguished by distribution. The Pilbara ningaui is the most range restricted, being endemic to the central and western Pilbara region of western Australia. The southern ningaui occurs in three disjunct populations across the southern semi-arid zone, whilst the Wongai ningaui is distributed widely across much of the interior. All species show a strong preference for environments dominated by spinifex grass (Triodia), which they use as shelter.

A ningaui takes shelter amongst the spinifex (Image credit: Euan Moore)

In regards to how they are related to other dasyurids, ningauis fall in the tribe Sminthopsini together with the kultarr (Antechinomys laniger, another species I really need to cover sometime) and many species of dunnart (Sminthopsis). However, recent phylogenetic studies have consistently recovered both Antechinomys and Ningaui as being within the Sminthopsis lineage, meaning that both ningauis and the kultarr are, in essence, just weird dunnarts. With Sminthopsis as we currently understand it being highly paraphyletic, a revision of the genus is needed.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

local doofus gets stuck down tiny pitfall trap intended for little mice and geckos

He’s clearly got a habit of getting into silly situations given something’s bitten the end of his tail off

Sand Goanna (Varanus gouldii) - Bon Bon Station, SA, November 2023

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had a cheeky camp at Red Banks Conservation Park a couple of days ago on the way back from fieldwork.

Species featured:

Red Kangaroo (Osphranter rufus)

Red-backed Kingfisher (Todiramphus pyrrhopygius)

Mallee Ringneck (Barnardius zonarius barnardi)

Striated Pardalote (Pardalotus striatus)

Brown Treecreeper (Climacteris picumnus)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello yes I am alive! been super busy this year but hoping to get back to posting

Guess there's no more on-brand way to return than announcing I have now seen ningauis irl! Got to see a bunch of southern ningauis (N. yvonneae) over the Easter weekend whilst participating in a small vertebrate survey on the Eyre Peninsula and it was a truly life changing event

they are my beloveds

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The NEW Ultrastenos and its Ironic History

So those that have been keeping up with my posts on mekosuchines might recall the name Ultrastenos, as I've talked about this genus back in August of last year. If you've read that post you might also remember how I highlight at multiple points that a lot of the info was tentative on the basis that Ultrastenos was highly incomplete and that close relatives awaited description.

You may also remember "Baru" huberi, a small mekosuchine that lived roughly around the same time, clearly distinct from Baru yet at that point still unnamed. Oh, how I wished for the former to get more material and for the latter to recieve a proper genus assignment.

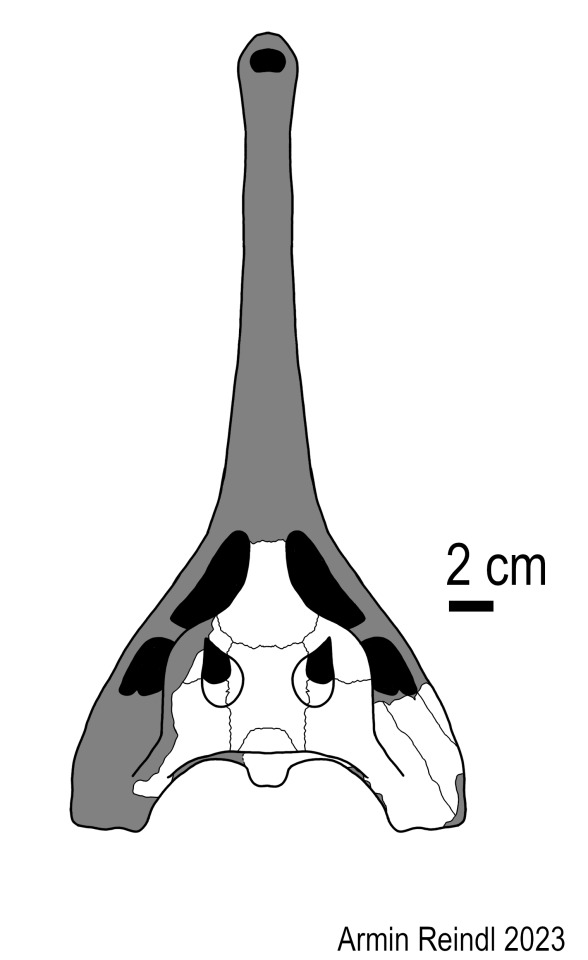

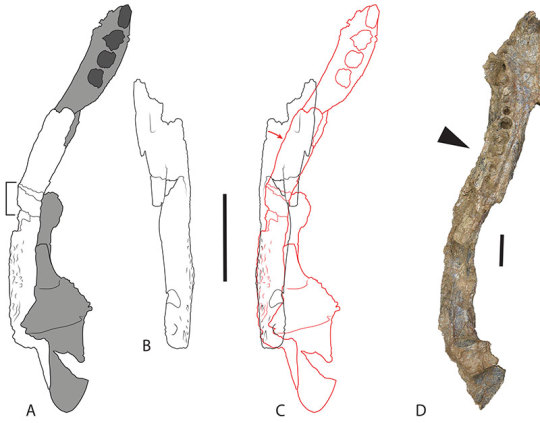

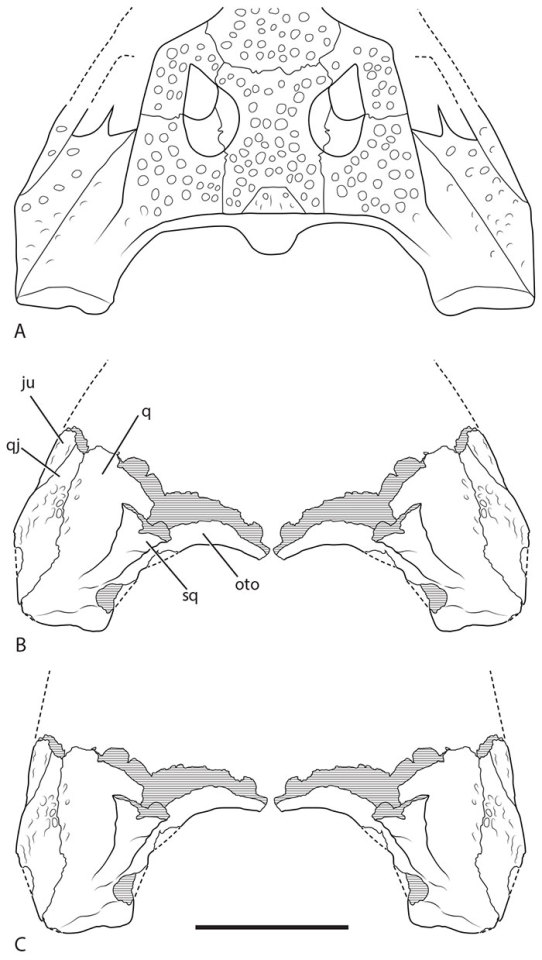

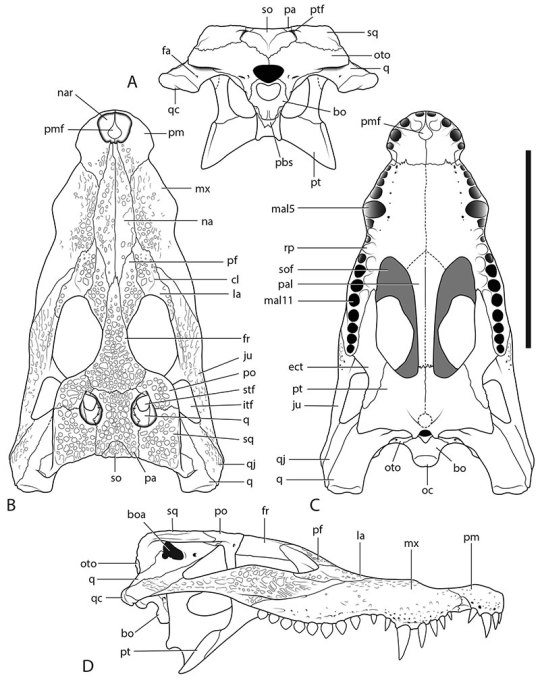

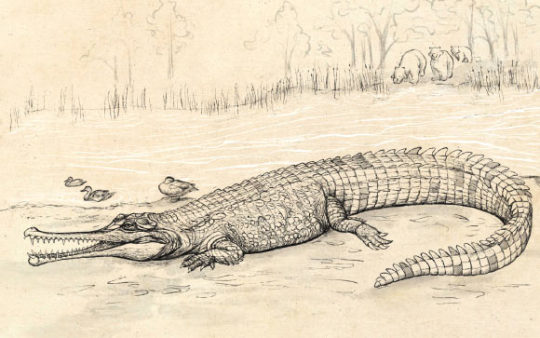

My now outdated reconstructions for "Baru" huberi (the small one in the left image) and Ultrastenos (right image)

And then the monkey's paw curled.

As it turns out....they are the same damn animal. Now, back when "Baru" huberi was described, Willis also named a bunch of other mekosuchines from the same locality (the White Hunter Site of the Riversleigh WHA) and described even more material that remained unnamed, including the White Hunter Cranial Form 1. Now, when Ultrastenos was named in 2016, the type material was from the Low Lion Site (also Riversleigh), but importantly, the skull tables identified as WHCF1 were also assigned to the genus (and were the basis for my reconstruction).

Well, re-examination has shown that the WHCF1 and the holotype of "Baru" huberi aren't just a single species.....THEY ARE A SINGLE INDIVIDUAL.

Given the fact that the assignment of the skull table to the Low Lion Ultrastenos material still holds up, this means that Ultrastenos willisi and "Baru" huberi are a single taxon. Which consequently requires some reshuffling of the names.

"Baru" huberi was named first, so the species name takes priority and continues being used. However, since it was never given a genus name, Ultrastenos does stay valid. Except now it's called Ultrastenos huberi, not Ultrastenos willisi. A name that has aged like milk. Back in 2016 it was proposed that Ultrastenos had a very narrow snout (thus the name), so now that we know that the rostrum was flat and mesorostrine, the name really is just wrong.

So next up, lets examine what went wrong.

As I said before, Ultrastenos was fragmentary, so that certainly played a big part in it. But the team in charge of describing the animal still cited several lines of thinking to support their interpretation, most of which are now thoroughly debunked.

As an example, the lower jaw was rather shallow, however while this was initially taken as evidence for longirostry, the 2024 paper states that this only an argument against altirostry (a deep skull), not against a more generalized condition. The teeth were also initially used as evidence, citing their homodont condition (the teeth looked uniform), HOWEVER, the problem in that was that there were only a few teeth present, all of which notably do not bear any resemblance to the needle-like teeth seen in other long-snouted taxa. Another important clue initially taken to mean longirostry was the orientation of the quadrate area and the seemingly sudden constriction of the lower jaw. But the quadrate area was not found in articulation and would support a generalized skull form if simply rotated a little, while the constriction of the mandible appears to at least be partially exaggerated by preservation.

Of course, the fact that we now have proper material of the snout makes the interpretation of a generalized skull shape a lot more solid.

Image 1: The left and right halves of the mandible of Ultrastenos compared to that of Baru iylwenpeny (D), note how the right half is a lot more straight. Image 2: The initial reconstruction of the quadrate area of Ultrastenos compared to one that is slightly rotated Image 3: The revamped skull reconstruction by Yates and Stein

The size of the animal does stay relatively unaffected by these new discoveries. "Baru" huberi has been estimated at only around 1.5 meters in length and my own scaling of Ultrastenos got up to 2 meters, which seems to be in line with what is still assumed for this animal. So among aquatic mekosuchines, its still rather small.

There are however some interesting implications for mekosuchines at large. Now that we no longer have a longirostrine member of this family, one has to wonder, why is that? Well, there might be several reasons.

It could be that the types of environments that were present in Cenozoic Australia simply didn't support such animals. Even in the type description, its been noted that the Riversleigh isn't exactly known for its fish remains, leading to the idea that Ultrastenos might have gone for other small vertebrates like frogs. Hell, the ecology of Baru might suggest that the reason that this genus was so robust might tie to the fact that the local bodies of water just weren't deep enough to allow the typical crocodilian grab-and-drown tactic.

Competition might have been another factor. In environments that may have been more suitable for such morphology, mekosuchines might have been beaten to the punch by other types of crocodilians. Harpacochampsa for example, tho originally thought to be a mekosuchine, is now more often regarded as either an unrelated crocodile or a gharial and its very possible that it filling the nische of a longirostrine simply meant that mekosuchines didn't have the opportunity to expand into that space. Same goes for Gunggamarandu in the Pliocene and Pleistocene and Freshwater Crocodiles from the Pleistocene onwards. (Tho it should be noted that both Harpacochampsa and Gunggamarandu are so fragmentary that their snout shape is technically unknown).

Images: Gunggamarandu (Eleanor Pease), Harpacochampsa (ArtbyJRC) and Freshies (Antoni Camozzato) might have been key factors in why mekosuchines never evolved slender snouts.

Finally, its also possible that something in the growth of mekosuchines simply prevents them from evolving longirostrine skulls, which Yates and Stein liken to alligatoroids (notably the closest alligatoroids got to traditional longirostry as seen in gharials is the Rio Apaporis Caiman, and even that one is closer to some extant crocodiles in its morphology).

Whatever the case, I for one mourn the loss of our long-snouted Ultrastenos. Tho as a note for any paleoartists, there is not a single illustration of this new interpretation since nobody ever drew "Baru" huberi either. Wink wink nudge nudge

Links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultrasteno

Ultrastenos revised (palaeo-electronica.org)

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been doing a lot of volunteer fieldwork with these guys recently so I thought I might as well do an infodump about them here.

The pygmy bluetongue skink (Tiliqua adelaidensis) is one of the most unique and unusual members of the Tiliqua genus, which includes the true bluetongues as well as the sleepy lizard/shingleback. However, the pygmy bluetongue actually lacks the blue tongue the group is named after, having a pink tongue instead! As its scientific name suggests, it is quite a range restricted species, being found only in open grasslands north of Adelaide, South Australia, as far north as Peterborough. Historically they ranged more extensively across the Adelaide Plains, as far south as Marion, but due to the destruction of suitable habitat they now occur no further south than Kapunda.

While most bluetongues are notable for their large size amongst skinks, with several species regularly exceeding 30 cm in length, the pygmy bluey lives up to its name by measuring a measly average of 9 cm long from snout to vent. This is actually still a fair size compared to the average skink, but it's miniscule by bluetongue standards. Even more notable than their size however are their habits, for they are the only species of lizard that is specialised to live exclusively in old spider burrows! The burrows of both trapdoor and wolf spiders are used, but trapdoor burrows are preferred in most instances.

Pygmy bluetongues spend the majority of their lives within these spider burrows, leaving only to defecate, seek out mates and disperse. The average length of time a lizard spends in a particular burrow is highly dependant on the individual - some are sedentary and spend many years within a single burrow, while others will move around fairly frequently. As well as places to shelter and raise their young (they have parental care, it's very cute), pygmy bluetongues also use the burrows as ambush sites, waiting at the top for suitable prey, usually a mid-sized arthropod, to stray close enough for them to quickly dart out and drag them into the depths.

now here's the ambusher

The chief natural predators of pygmy bluetongues are raptors and brown snakes, and sheltering in the burrow is the main defence against both of these threats. Their burrows are often wide enough for a brown snake to enter, but not wide enough for them to open their mouths in - this means all the brown snake usually gets by pursuing a sheltering pygmy is an angry lizard attacking its face, forcing it to retreat.

The lazy lifestyle of the burrow-stealing pygmy bluetongues is certainly unique, and also explains why they have been such an elusive species since they were first discovered by Western scientists in the 1860s. Rarely seen or collected, their habit of inhabiting spider burrows remained undiscovered for the longest time, and by the 1960s they had become so hard to find that they were believed to be extinct. That was until, in 1992, a pygmy bluetongue was found inside the stomach of a roadkill brown snake by amateur herpetologist Graham Armstrong, confirming their status as a Lazarus of the lizard world.

The historic rediscovery of the pygmy bluetongue (Image credit: Graham Armstrong)

Our previous assumptions of extinction were fortunately premature, but the pygmy bluetongue skink is in serious trouble nonetheless. While they are able to live in a variety of different grassland types, both native and exotic, the extensive modification of their entire distribution through cereal cropping and urbanisation has led to their populations becoming very small and fragmented, giving them a ranking of Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Almost all of these populations are on private land (often grazed by sheep), which makes protecting and/or studying them particularly difficult and complex.

However, when it comes to future threats to the species, climate change is easily the most worrying. As Australia becomes ever hotter and drier, their small remaining distribution is likely to become largely unsuitable, threatening the existence of the entire species. To combat this, researchers are currently investigating the viability of translocating populations further south to areas with cooler climates, providing a safeguard if they do indeed disappear from their remaining natural distribution.

But how do you study a lizard that lives exclusively in small spider holes? Well, if you want to catch them, there's only one tool for the job - the humble fishing rod. Not any special fishing rod either, just a regular rod with a poor mealworm shoddily tied to the end. Using this, you can engage in a tug of war with the lizards until, if they aren't being too difficult, you're able to pull them completely out of their burrow and catch them to perform the necessary measurements and processing. David Attenborough kindly demonstrates this technique in Life in Cold Blood, although in his case the lizard was steadfast in remaining in the burrow!

the sacred tool of the mighty lizard fishermen

returned to their abode

Two additional Fun Pygmy Facts: Fun Pygmy Fact #1 - The closest living relative of the pygmy bluetongue is the sleepy lizard!

cousins!

Fun Pygmy Fact #2 - Wooden artificial burrows purpose-made for pygmy blueys have proven effective, and the lizards inhabiting them even tend to be in better body condition than those in natural burrows!

886 notes

·

View notes

Text

She's so perfect she just goes right back to doing her thing

73K notes

·

View notes

Text

the child seeks refuge

Spinifex Hopping-mouse (Notomys alexis) - Bon Bon Station, SA, November 2023

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

you’re not a true dasyuromorph disciple until you have a wild quoll walk up to you and sniff your phone

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The south-eastern shores of Granite Island, South Australia, taken whilst clambering across the boulders in search of little penguin burrows for an annual census. My team didn't end up finding any active burrows (in general they're a lot less common on this side of the island nowadays) although we did find one with hatched eggs and a ton of down.

Also apologies for not posting much here but currently I am being slaughtered by uni work

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy international wombat day!

Southern Hairy-nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus latifrons) - west of Blanchetown, SA, September 2019

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

This year has been quite rich for new dasyurids - a couple months ago we were gifted with a couple new planigale species from the Pilbara, and even more recently, a new paper by Newman-Martin et al. was released that found mulgaras, previously believed to be two species, are actually six. Tragically, the number of mulgara species out in Australia's deserts today remains two, as four of these species are already extinct.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. For someone who isn't a dasyuromorph disciple or other variety of Australian mammal nerd, what are mulgaras?

"Crest-tailed mulgara" on the left and "brush-tailed mulgara" on the right (Image credit: Yingyod Lapwong & Owen Lishmund)

Mulgaras (Dasycercus) are a genus of carnivorous marsupials in the family Dasyuridae, which includes Tasmanian devils, quolls and a huge variety of other smaller but equally vicious predators. A fair size as far as dasyurids go, these rat-sized mammals are specialists of arid and semi-arid environments and were previously widespread across much of inland Australia, but their distribution retreated deeper into the interior of the continent following European colonisation. One trait that sets them apart from other dasyurids is their burrowing prowess - while many dasyurid species will inhabit burrows dug by other animals, mulgaras are skilled diggers that will construct their own extensive burrow networks, complete with a main entrance and several side tunnels and pop holes.

Trying to figure out how many species of mulgara there are has always been a source of great confusion to mammal taxonomists. The first species described was Dasycercus cristicaudata back in the 1860s, followed by D. blythi and D. hillieri in the early 1900s. These two new species were synonymised with D. cristicaudata in 1988, leaving one species of mulgara. In 2000, mulgaras were split back into two species, D. cristicaudata and D. hillieri, but a 2005 study believed the species in question had been misidentified - what had been thought to be D. hillieri was actually D. cristicaudata, and what had been thought to be D. cristicaudata was actually D. blythi. Confused yet?

Dasycerus blythi (Image credit: Walter Baldwin Spencer)

Since then, the consensus has largely been that the two species of mulgara were the crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicaudata) and the brush-tailed mulgara (D. blythi), both named after their distinctive tail shapes. However, the new paper turns this idea on its head yet again, with the most dramatic revision of Dasycercus species thus far.

Based on measurements of the teeth and skull, Newman-Martin et al. identified six different species within Dasycerus - this included D. cristicaudata and D. blythi, the previously invalidated D. hillieri, and three newly described species, D. wolleyae, D. archeri and D. marlowi. Despite this, the two previously identified living populations remained the only surviving species, with the other four being considered likely to be extinct based on their distribution. However, in one final twist, the surviving mulgaras previously considered to D. cristicaudata were found to actually be D. hillieri after all, meaning the type species of the genus is now among those believed to be extinct!

Of these species, three (D. cristicauda, D. hillieri & D. archeri) could be considered to be "crest-tailed" and two (D. blythi & D. marlowi) are "brush-tailed", while the sixth species, D. woolleyae, is usually crest-tailed but rarely brush-tailed. Given this, the appearance of the tail is no longer a distinctive characteristic of any of the species, but the authors stated that the common name could be kept for the extinct D. cristicaudata and potentially also the extant D. blythi. All other species required new common names, listed below:

Ampurta (Dasycercus hillieri)

Spinifex/brush-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus blythi)

†Crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicaudata)

†Northern/sand mulgara (Dasycercus woolleyae)

†Southern mulgara (Dasycercus archeri)

†Little mulgara (Dasycercus marlowi)

What was previously believed to be the "crest-tailed mulgara", D. cristicaudata, is now the ampurta, D. hillieri! (Image credit: Mike Letnic)

The fact that four species of mulgara are now extinct is not only inherently disheartening, but these also represent the first known dasyurid species to have disappeared in modern times. Dasyurids were previously considered to be more resilient to the impacts of invasive species and habitat degradation than other small marsupials, hence why no species had yet been lost, but the discovery of extinct mulgaras demonstrates that we are likely underestimating the impact that European invasion has had on dasyurid diversity. There may well be many other species that have already been lost without us ever realising they even existed.

But, while more than half of the mulgaras are tragically now extinct, we must also appreciate the precious species that remain. The brush-tailed or spinifex mulgara thankfully remains widespread and common, but the ampurta now occurs in only a small portion of its former range and is considered to be vulnerable to extinction - we must take careful steps to protect this enigmatic little marsupial, unless we want to see Dasycercus lose yet another species in the not too distant future.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

maleefowle <33333

hello wilds of tumblr

A few days down at Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park on the Yorke Peninsula last weekend delivered the goods as usual. I was mainly targeting peninsula brown snakes, which was a big success with 4 individuals seen! This big girthy fella (his name is Clifton) gave me particularly good views before I had to shoo him off the road.

I encountered lots of other cool guys along the way of course, including reintroduced tammar wallabies (woylies continue to evade me though), plentiful emus and even a surprise malleefowl.

(From left to right - tammar wallabies, tawny-crowned honeyeater, emus, malleefowl, painted frog, sleepy lizard/shingleback and eastern bearded dragon)

Herping season is now well underway so hopefully I can find more cool stuff if I manage to not die from uni work

11 notes

·

View notes