Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Half Joke/Half Murder

Inside

A total (…) of the heart

A total (…) of the sun

(Canned Laughter!)

Take out my eyes, so I will never see

Wrap me up tight, so I will never feel

I pray to the (…) for a numbness against everything that’s real

I take a knife to the (…) and twist it in…Look in my eyes…nothing inside…

But Lips Skin Blood Wind Whore Kind State Mind Drawn Out for All Accounts

Cut to a moment of kindness

A face behind glass tells me my account has been frozen

Pending an investigation…a random check…a security measure…

Post 9/11…it was 2002… or something like that…I think…not sure now…

Of the exact details

Nothing to worry about, if I’ve got nothing to worry about…

Nothing to do with my name or colour or anything like that

Of course

The face behind the glass reassures me

I stagger out in my work boots and into the bar opposite

Penny less I return to the table were my friends sit…

They laugh, say I’m obviously a terrorist, and buy me a drink

Auld Annie who’s been on the game since before I could walk

Says:s

“Fuck the British…

Fuck this country…

It’s always been a racist and classist pile of shit…

I’m sorry son, hope yer ok?”

I nod, but shrug my shoulders

A total (…) of the heart

A total (…) of the sun

(Canned Laughter!)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Myth of the Archive of Everything

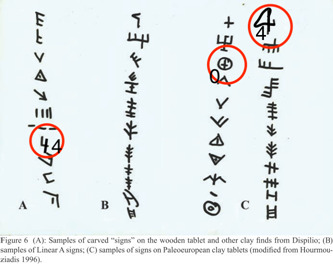

"The Web was not designed to be preserved," says Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive, a non-profit library of millions of free books, film, software, music, websites and more. "The average life of a Web page is about 100 days," he adds. Kahle is currently on the lookout for an old optical disc drive containing a copy the first ever webpage. It was lost at a conference in California in 1990. Around about the same time, the archaeologist George Xourmouziadis was digging at the site of a Neolithic lake settlement in Northern Greece. In 1993, he found the earliest known example of written text in the world, the Dispillio tablet, a chunk of inscribed wood that had lay buried in the mud for 7,500 years.

The tablet, however, in the absence of some sort of Rosetta stone, is indecipherable. In a way, it is like one of those old floppy discs you might find at the back of a drawer or in a box you stored at your dad’s if you went to university in the late 90s. It’s a strange yet familiar object, and you know it contains information, but you have no way of accessing it, of reading it. Of course, whilst it has taken many thousands of years for the text on the Dispillio tablet to become unreadable, my dissertation hasn’t even made it twenty years, unless I had access to what would by now be pretty specialist equipment.

“He went a long journey, was weary, worn out with labour, and returning engraved on a stone the whole story.”

So goes the world’s oldest known written story, the “Epic of Gilgamesh”, fragments of which have been dated to 2000 BCE. Perhaps other weary travellers returned home and told their story to a friend, which may seem less durable than stone. And yet, research has shown that some Pawnee stories document events that took place during the last glaciation, at least 11,000 years ago, and linguists and geographers have proven that Aboriginal Australians have stories that contain accurate oral histories stretching back 400 generations to over 10,000 years ago. It is therefore important to listen for stories that cannot be physically held in our hands, but that survive nonetheless, perhaps by virtue of the fact they can’t become buried in mud or lost at the back of a drawer. However, these stories do not survive by accident. Oral history keepers are not just saying whatever comes into their head. In Aboriginal Australian communities, for example, complex system of inter-generational kin-based responsibility and cross-checking of stories ensures they are retold and retold verbatim, much in the same way that a Babylonian scribe had to be trained to accurately write the complex cuneiform script.

But in ancient Babylonia, even if a scribe transcribed a text accurately, decisions made by archivists could still render a document unstable. Texts deemed important by the ruling class, such as legal documents, were recorded on clay tablets, while even more ‘important’ texts, such as royal decrees, were written on stone or precious metal. Meanwhile, the Babylonian language and the cuneiform script were generally used for stone or clay inscriptions, whereas Aramaic texts, used in day-to-day trade throughout the region, tended to be written on more perishable material such as parchment and leather. How documents were stored—in jars, boxes or bags or within stone temples, or on specially designed shelves within a royal compound, for example—also affected their longevity. However, even once-important clay tablets were often eventually disposed of, being written over or recycled into floor filling when they were deemed to be no longer of use. In fact, it is thought that many of the texts that survive to this day do so only because they were hidden in times of war by owners unable to ever return to them, grow bored of them, and use them as filler in the foundations of their new extension…

They say that the most important years of a person’s life are their first three years, during which time the very foundation of our being is formed; and yet during that time we are almost universally illiterate. What do babies dream about? What stories do they tell themselves? My six-year-old son is learning to read. “What does that say?” he asks, pointing to an advert for an investment bank. “See More, Be More,” I tell him, and then we unpick the meaning of the text in great detail until we get to Govan. I feel suddenly sad at his new desire to discover the world through text when only 4 years ago he felt it out with tongue and spit, took it into his mouth or fingered it greedily. Of course there are limits to what you can understand in this way, and so language; and there is something particular about written language, even in the way it reaches for a sort of representative neutrality which, of course, it can never contain.

This seeming neutrality is no more evident than on the internet, where we are presented with never-ending feeds of black text on white screens that seem to issue more from the ether than from any mouth. Web content is now overwhelmingly created by non-professionals—by people who go on a journey and returning, weary, worn out with labour, blog about it, tweet about it, write an email to their mother about it, post it on Facebook or Insta. Would they had chiselled it in stone! Because even though these stories and ideas, these projects and diaries, these poems and love letters appear on a screen and have the potential, indeed, to appear on any screen throughout the world, that doesn’t mean they are safely archived. As Jason Scott, an archivist and historian at the Internet Archive says of web-based material: “when it goes, it really goes[…] there is just zero recourse.”

Then there are the silences. In order to archive, an archivist must have material to work with. Yet 45% of the world has no internet access. And whereas in the past, anonymous was a woman, now they are more likely to be a middle-class, white Western man. The seemingly neutral black text on your screen that appears to have been almost communally created by a hive mentality, representative of everyone, leading some to argue that the internet is a platform that can break down barriers to communication, challenging, say, the classed and gendered world of publishing, the facts of the matter say otherwise. A recent American study showed that there are far fewer female bloggers, hackers and Wikipedia editors than there are male ones. Wiki is one of the most used websites in the world and often the first place people go for information, and yet in America only 25% of editors are female, and globally the figure drops to 20%. Women use the Internet much less than men too: globally 12% less, but in places like Africa, 25% less. Men publish more tutorials, podcasts comments and reviews than women and launch more petitions. Only 11% of open-source programmers are female. Class, race and nationality intersect to make these figures far starker in countries such as Palestine, Turkey or Brunei.[1]

The barriers to women’s online participation are multiple and include lower incomes as well as lower literacy and computer-literacy levels globally. Online discrimination, hate speech and harassment also makes it harder for women to participate, with a recent study showing more than 50% of women have received unsolicited offensive images. Much like in the world of paper journalism, online comments regarding female-generated content tends to focus less on the facts of the matter and more of the physical appearance of the women concerned. The Guardian reported that “articles written by women attract more abuse and dismissive trolling than those written by men, regardless of what the article is about.”

People of colour also face increased levels of harassment online. As Hannah Pool, a British-Eritrean journalist and blogger, commented, “I could post my shopping list and I’m pretty sure the thread beneath would include some variants of “go back to Africa”. Two recent studies looking at reactions to similar comments on race by both black and white authors showed that black authors faced significantly higher levels of negative reactions than white ones.[1] Another report showed that British Muslim women faced high levels of online trolling for wearing hijabs or other religious garments. In his book, Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide, Henry Jenkins states that online content creators are, ‘‘disproportionately white, male, middle-class and college-educated’’.

But we shouldn’t be surprised. After all, there has only been a digital revolution, rather than the cultural, philosophical, political and economic revolution that would bring genuine change. The biggest lie we are sold is that technology in and of itself can free us—that it is in the process of liberating us and of breaking down class, gender and racial inequalities. Meanwhile, Google promises us the ‘archive of everything’, insisting that if they develop the technology to capture and archive all digital content, alongside projects to digitise print books en-masse, they will have created an archive of the whole wide world. We must then question what is meant by ‘everything’, who is archiving it, and why. For even if issues of production were addressed, and we all became content providers, and even if Google managed to capture all of that content, and record every single story ever told, from the first to the last, someone or something still has to guide us to that content, sift through it, present it to us. As Walter Benjamin pointed out:

“Perhaps the most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: “he [sic] takes up the struggle against dispersion [Zerstreuung]. Right from the start, the great collecter is struck by the confusion, by the scatter [Zerstreutheit] in which the things in the world are found.”

The archive is therefore more about ordering than hoarding. Yet the archive of everything pretends to an objectivity that does not exist. It pretends that in collecting everything it makes everything available, or potentially available, and even that it records our history and culture in a fair and objective manner. It masks the politics of production on multiple levels: the production of knowledge (culture, education, language), of content (writers, speakers, listeners, readers), and of consumption (algorithms, advertising, canons).

For the world already contains ‘everything’, and this ‘everything’ is continually archived through language and stories, culture and memory, networks and systems, and currently, overwhelmingly, this ordering is filtered through process of valourisation in a world dominated by capitalism. We must therefore see every attempt to collect and order as a political act, one that is intricately tied up with power struggles: how do you produce, record and represent the history of a nation, a people, a language, a culture, a world, in an archive?

As people and institutions large and small—from the government and the BBC to your local labour history group; from Google, to your 15-year-old daughter—grapple with the Babelian project of how to capture everything, there is a further shift from a focus on (intellectual) production to that of consumption. And this shift imagines that archivists are now involved merely in a technical project of trying to collect the whole wide world, risking subsuming the politics of the archive, and the space therein for resistance, to the illusion of a totalising objectivity. It is only by re-politicising the productive function of the archive—its capacity to generate culture, ideas and history—that we can show that the archive of everything is nothing more than a myth about how stories are told, and about how they are remembered, or forgotten.

[1] https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/media-spotlight/201703/race-and-the-internet

[2] https://www.alumniportal-deutschland.org/en/global-goals/sdg-05-gender-equality/women-internet-digital-gap/ [accessed 19/02/19]

0 notes

Text

Silences! Workshop III: some reflections

On Monday 4 February, the Hitherto Unknown team held their third workshop inspired by the legacy of writer and radical activist Tillie Olsen. Packed into the Scotia bar, there was an amazing range of people and ideas: working class voices, Marxist feminists, playwrights, artists, researchers, writers, tenant union activists, and international students. We discussed suggestions and contributions for the new radical leading lists we are assembling, as well as possibilities around reading groups, film nights, and further investigations for the project. We also raised a dram to Tom Leonard, who sadly passed away before Christmas, with a reading of his poem ‘in hospital’.

One of our workshop participants, Keira McLean, kindly sent on her thought on the workshop:

“I really enjoyed the workshop: it felt liberating to share things, read, and discover new authors. So much of the discussion from the workshop has stayed with me since. The complex questions of authorship, taste, value, purpose and legitimacy generated by the project have left an imprint this past week. Thinking of my own reading habits and favourite authors, trying to examine my own relationship to words, how has what I’ve read shaped and influenced me? In many ways I’m merely an amalgamation of the words and ideas of others, repositioned, re-contextualised, and re-expressed as my own. When I think about it, words made me. And re-made me. Over and over. So I look forward to being re-made again and again through participating in this project, through the discovery of new authors, new words. Thank you.”

In the true spirit of Tillie Olsen, Keira also sent on a poem of hers she recently rediscovered when looking back through old work.

“I did a book of hours instillation and found a poem I wrote about loose leaf tea, and the way working class culture is commodified and rebranded as chic / hipster, while also tying in with the ubiquitous slogan of ‘Keep calm and carry on’, which in essence is austerity propaganda! It also rhymes, which as another participant mentioned at the workshop, is not too fashionable in poetry these days!”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Attempting to physically find books by women: a report

Hitherto Unknown has worked with several bookshops in Glasgow (such The Magpie’s Nest in Govan and Oxfam Books on Byres Road) to organise displays based around Tillie Olsen’s reading lists. Staff in Waterstones have been supportive of the project, so some members of HU went along to the Sauchiehall Street branch to see what books from the lists were already there. Jessica Simons reports…

In an attempt to respond to Tillie Olsen’s call to ‘make your own survey’, myself and another HU participant decided to go along to Waterstone’s to source some of the writers which appear on the reading lists. Very quickly we realised we were going to struggle to find the majority of the female writers. Although Waterstones is Scotland’s largest bookstore we only succeeded in sourcing a handful of them. Almost being able to predict beforehand which female writers they would have in their collection, we found some copies of books from Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Sylvia Plath, Doris Lessing and Maya Angelou. However, the majority of the female writers failed to appear amongst the many bookshelves filled with novels by successful male writers such as Chekov and Zola who are also shared on the list.

Disheartened (momentarily!), we reflected on why this should be and the determined choices made by publishers to silence these writers. It is those past decisions that have shaped what reading material appears in our book shops and our limited knowledge of a whole collection of female, black and working-class writers, deprived of the opportunity to have their work shared on a larger scale, pushed to the side lines. This exercise of attempting to physically find these books served to highlight the importance of trying to source, where we can, any material written by these significant, yet marginalised female writers, breathing new life into them. In doing so, hopefully we can draw Waterstones’ attention to the limited collection they have and use this as inspiration to compile and share our own radical reading lists of writers whose voices should no longer fail to be heard.

0 notes

Text

1. When does literary history end?

Olsen, T. (2003). Silences. First Feminist Press Edition. New York: Feminist Press, P24.

In Silences, Tillie Olsen said:

‘For a week or two, make your own survey whenever you pick up an anthology, course bibliography, quality magazine or quarterly, book review section, book of criticism.’

I decided to do a very brief survey of the literature course I studied at the University of Edinburgh, which houses the oldest English Literature department in the world.

The first two years of study there focus on literature from 1750 to 1950. It strikes me as weird that this particular date marks the end of this so-called ‘core’ literary history—just about the same time as the end of Empire. As Olsen notes, “Not until several centuries ago do women writers appear…then black writers (1950 was the watershed year).” The Windrush and post-windrush era brought Beryl Gilroy, Sam Selvon, Andrew Salkey, Joan Riley, Grace Nichols, John Agard, Amryl Johnson, Linton Kwesi Johnson and Petronella Breinburg to the UK, as well as writers from India, Pakistan, and throughout Africa, including Farrukh Dhondy, Buchi Emecheta, and Margaret Busby. Why end a literary survey of the UK the year immigration from outside Europe dramatically increases?

A quick count of the authors mentioned on the core lectures lists shows that 33 out of 47 authors are male, all are white, and almost all from middle or upper class backgrounds. I seemed to remember options courses being a bit more representative, but am horrified to find that the 3rd year options courses also have slim pickings outside of white, male, middle-class authors. Even on the course ‘American Political Fiction Since 1945’, which aims to look at how authors approached ‘key political issues—war, sex, race, money’—8 out of the 9 novels studied are by white men, and only one by a black woman (Toni Morrison). Another course, ‘Cities of Words, 20th Century Urban America’, has only one black writer and two woman writers (Toni Morrison and Anzia Yezierska), despite focussing on New York (44.6% white) and LA (41.3% white). Only one course has all female authors: ‘Women’s Autobiography from 1650-1700’. In ‘The Victorian and Edwardian City’, only one writer is a woman (Mary Gaskell), despite the fact that in 1850 women wrote roughly half of all fiction titles.[1] I’ve not looked at the 4th year options courses yet, but even if they offer an array of fiction from a multitude of writers, it would be too little too late; and why make the work of writers that have already been marginalised in so many ways ‘optional’ rather than ‘core’?

What were you asked to read at school, college or university? Did the authors reflect the world around you, or were they mainly white, middle-class, men?

[1]http://culturalanalytics.org/2018/02/the-transformation-of-gender-in-english-language-fiction/

0 notes

Text

Draining Board

by Frances Corr

the kitchen area

is a breeding ground for depression

you can make a kitchen area

by simply employing a plumber

to lead the flow of water

to a tap near a draining board

where someone might stand and become depressed

draining board is true enough

0 notes

Text

‘In the reference room’: a visit to the Mitchell Library’s Special Collections and Archives.

Helen Vincent, Head of Rare Books, Maps and Music at the NLS, Edinburgh

In the spirit of Tillie Olsen, and her lifetime’s project of finding silenced writers and asking us to listen to them, the Hitherto Unknownresearch group met on Thursday 1stNovember 2018 from 5:30-7:30pm at the Archives and Special Collections Department on the 5thfloor of the Mitchell Library in Glasgow. The aim of the meeting was to find out more about how to access the vast swathes of material both catalogued and uncatalogued, digitized and analogue, available at the Mitchell library and the NLS in Edinburgh.

We were inspired by Tillie Olsen’s own account of one her famous works of recovery:

“It was not until the collected Letters of Emily Dickensoncame out in 1958 that, in the reference room of the San Francisco Public Library where I went luch hours from work to read them, I learned who the author [of Life in the Iron Mills] was. Appended to a note from Emily to her sister-in-law,

Will Susan please lend Emily “Life in the Iron Mills”—and accept blossom

was this citation:

Rebecca Harding Davis’ “life in the Iron Mills” appeared in the April 1861 issue of theAtlanti Monthly.

Olsen, T (2003), Silences, p117

As a result of Olsen’s finding these bibliographic details of a text she’d read twenty one years previously in “one of three water-stained, coverless, bound volumes of the Atlantic Monthly, bought for ten cents each in an Omaha junkshop,”[1]when she was just fifteen years old, she was able, many years later, to teach the text on her Amherst courses, eventually publishing the Reading Lists she devised there in the Feminist Press’ Women’s Studies Newlsetter[2]. In 1970, she approached Florence Howe, founder of the Feminist Press, who recalls that Olsen “gave Life in the Iron Millsto the Feminist Press and said she had written a biographical and literary afterword that we could have as well, that changed the whole course of publishing for the press”[3]. As a result, Rebecca Harding Davis’s incredible story of a working-class artist and iron worker, originally written in 1861, was reprinted by the press in 1972, and remains in print to this day, recognised as one of the earliest examples of American Realism.

Isobel Maclellan (centre), librarian at the Mitchell Library’s Special Collections & Archives department

The first speaker at the Hitherto Unknown event was Isobel Maclellan, a librarian at the Mitchell’s Archives and Special Collections Department. Firstly, Isobel was keen to emphasise that anyone can access the archives at the Mitchell—you don’t have to be a student or have a letter of recommendation or anything like that. Special Collections includes local history in books, photographs and ephemera as well as family history and newspapers. It also holds a range or rare books and manuscripts, including books printed before 1500 (Incunabula) and broadsides (large sheets of paper printed on one side only).

One thing Isobel wanted to make clear was that many of the materials held in the library are not listed on the online catalogue, which only deals with acquisitions from 1970 onwards—and many items are not catalogued full-stop. This means that the potential for making an exciting find is enormous. Staff are happy to help with any searches you’d like to make and can show you how to search using card indexes, finders or microfiche catalogues. Isobel also showed us the request slips you can fill in if you’re looking for specific material. Staff will do their best to find what you are looking for, and are often the key to finding your way around material that hasn’t yet been catalogued. There is an oversized folder on the desk in the Glasgow Room on level 5 which lists many periodicals and journals held in the collection, including the the Glasgow socialist newspaper Forward, one of which Isobel had brought along with her to show us.

It was a gigantic newspaper, rich with illustrations and articles that couldn’t be found anywhere else in Scotland. Isobel also showed us one of Janice Galloway’s notebooks from when she was writing The Trick is to Keep Breathing, and some of her unpublished short stories. There were also some original letters from Catherine Carswell to F. Marion McNeill. It’s incredible that all you have to do to sit with these items and leaf through them is go in and ask! If you want to look at the items, you have to do so in the Special Collections department and Reading Room on the 5thFloor. Anyone can go in as long as they leave their coats, bags and pens in the lockers provided—pencils only!

After Isobel’s talk, Helen Vincent, Head of Rare Books, Maps and Music Collections (dream job title!) at the NLS spoke about how to look for books written by women using a catalogue system that doesn't mark the gender of authors. Searching political documents won’t get you very far, she said, as women were excluded from that realm for many years. However, women were ‘allowed’ a voice in religious matters and so it can help to start your search for texts by women there. She also told us about some of the out-of-copyright Scottish books that have recently been digitised, including literature by Violet Jacob and Catherine Carswell, and talked about Henrietta Liston's journals, as well as NLS online resources such as 'A guid cause', a toolbox about the women’s suffrage movement in Scotland made using archival sources from the NLS’s collections.

The group then spent some time looking through the archival materials on display, and fed back to the group about any 'finds'. One participant talked about community newspaper collections from the 1970s from Castlemilk and Govanhill; another read a verse from a poem by Nat Raha, a contemporary poet who lives in Edinburgh. Another participant talked about Agnes Owens, a Scottish novelist and short story writer, whilst someone read from the Janice Galloway collection, having enjoyed reading one of her short stories. We briefly talked about moving forward, about starting to use the archives at the GWL, the NLS, the Mitchell and beyond to inform our own research as we begin making our own reading lists in the spirit of Tillie Olsen, and for our own time and place.

France Corr reads one of her poems

Frances Corr finished the session by reading two poems to the group. Both resonated strongly with us and were situated in the domestic, another space that is often uncatalogued and silenced, or unheard. We hope to explore the domestic next year when we visit the NLS Moving Image Archive on Saturday 9thMarch 2019and take a look at some of their home movies with Emily Munro, the Learning and Outreach worker there. Joey Simons of Hitherto Unknownfirst heard Frances’ work at a Women Against Capitalism event in Castlemilk. We hope to draw together the work of more writer/activists, those writing prose or poetry that is against. Finally, at a research workshop at Platform in Easterhouse on Monday 4thFebruary 2019, web archivists from the NLS will help us learn how to archive work published on the internet, whether as video, image or text.

In the afterword to the anthology of afro-American writing,Black Fire, Larry Neal wrote: “The artist and the political activist are one. They are both shapers of the future reality”[4]. And yet, as in the case of Davis’s Life in the Iron Mills,the brilliance of a text is not enough to preserve it in a world where those who can shout the loudest are often those with the means and power to widely broadcast their ideas and culture. It is our task to keep reading, keep sharing, keep enthusing and documenting, taking these texts into an ever-shifting working-class culture of our own, that aims to disrupt the one that is daily shoved down our throats. We hope you can join us!

[1]Olsen, T. (2003), Silences, New York: The Feminist Press, p117.

[2]ibid. p298.

[3]Howe,F. (1994), quoted in Listening to Silences: New Essay in Feminist Criticism,Hedges,E and Fishkin, S.(eds.), New York: Oxford University Press, P27

[4]Jones,L & Neal, L (ed.) Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing,New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc, P656.

0 notes

Photo

Tillie Olsen’s Silences is unfortunately as relevant today as it was when it was first published 40 years ago.

0 notes

Photo

The radio silence is over! We held our first Hitherto Unknown workshop at the Glasgow Women's Library on Thursday, discussing Tillie Olsen's radical legacy and its relevance today, looking through the books on her reading list available at GWL, and beginning the work of exploring the archives for the silences present today. Stay tuned for info on upcoming workshops and more exciting news...

0 notes