Text

Book Review: Dozakhnama - Conversations in hell between Manto and Ghalib

"Manto Bhai, don't you agree that you cannot try to write poetry? Poetry must come to you on its own. But we don't know why it comes, or how. Do you know what I think? I think you cannot call someone a poet even if he has written a thousand ghazals, but if he can write even a single sher like a howl of pain, smeared with all the blood in his heart, then and only then can we call him a poet. Poetry isn't a sermon delivered from a mosque after all; it is one's final words from the edge of the ravine, face to face with death."

Given that it's a time when there are more and more books that qualify as 'quick weekend reads', 'breezy, one-time reads', it is an indescribable feeling when one comes across a book like Dozakhnama: Conversations in Hell. Words cannot express the comfort this book provides - I wished that the book would never end. Meant for posterity, this is a book best consumed like a box of sweets you can nibble at everyday, and take joy from the fact that there's still so much left to devour.

The bonus: You'd want to take the journey all over again, just to experience those literary orgasms that came in paragraphs of sheer brilliance.

But these are not ordinary conversations.

They're between... wait for it... Manto and Mirza Ghalib, two of the most enigmatic figures in literature, both of whom found fame posthumously and who continue to live on in public memory thanks to the power of their words.

Each chapter is like a monologue and all put together, the book is a conversation happening between their graves, through shared dreams. Pal (translated here flawlessly by the very talented Arunava Sinha) makes an ambitious attempt to pen the most imaginatively written biography of Manto and Ghalib, and lets it simmer in the frothy history of Indian culture. Does he succeed? Hell yeah! (no pun intended).

While Ghalib's story captures a more ancient period in Indian history, Manto goes about sharing his life's journey in a more modern era. The former's frustrations and agony compound and give shape to his terrific ability for verse, while the latter's account is those of his adventures as a struggler in the early days of India's film industry, socializing with commercial sex workers in Bombay's red light district.

While neither of them try to outdo the other in the 'my-story-is-sadder-than-yours' routine, they incidentally show a shared passion for consuming liquor, gambling and women. There also appears to be a shared worldview about marriage being a tumultuous bed to sleep on, whereas the brothels provide opportunities aplenty for experiencing love and heart-break. (I personally had more sympathies with Ghalib's condition than Manto's.)

What also becomes clear, upon reading of this book, is a similar trajectory of their experience facing rejection constantly during their lifetime, and sweet redemption years after their death.

Those who've read Manto and Ghalib's works in depth may find the conversations in Dozakhnama a bit of a repetition of stories they already know, but for the others, this book is an incredibly kind and sorrowful jugalbandi of sorts, that catches two icons in a memorable conversation you'd like to listen to, again and again. Buy the book, and don't lend it to anybody.

Dozakhnama is available on uRead.com for Rs 331 (17% discount) Order now!

ISBN: 9788184003086

Publisher: Random House India

Cover design: Mishta Roy

#dozakhnama#manto#ghalib#rabisankar bal#arunava sinha#random house india#dozakhnama translation#dozakhnama book review

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

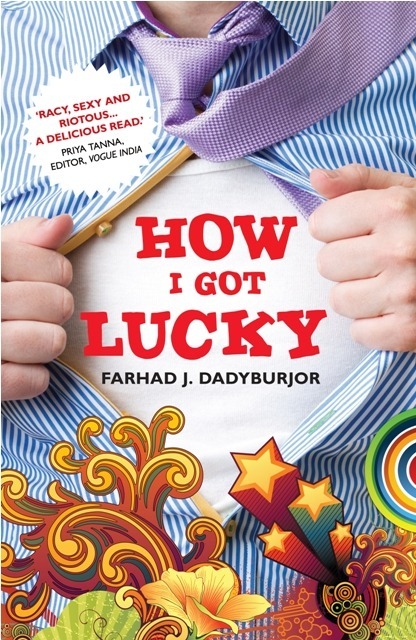

Book Excerpt: Farhad Dadyburjor's 'How I Got Lucky'

Pre-order your copy for Rs 188 on uRead.com and get free shipping: http://www.uread.com/book/how-i-got-lucky-farhad/9788184003147

If only you thought about it.

Railway stations were matrimonial ads in disguise—waiting to happen; a love paradise abandoned of its reaping. Faces criss-crossed in a hurry, everyone rushing somewhere, with their pliant guises of variable emotions firmly set in their outer masks. It wasn’t a large stretch: hope, fear, anxiety were the regulars. The rest were just deadened in anger, creased by non-love. And yet, with a sliver of eye contact...perhaps it could all change.

Raman scratched his outer thigh. It was the state of the city; it was what it demanded. Lock your doors and sleep light. And if you get a spare moment—pray. Pray that someone loves you. Your servants love you. Your watchman. The early morning unrecognisable newspaper boy. This was important. It could be life-enhancing. As for money—oh yes, money—there was plenty of that. It was half-regarded. Not reason enough.

Your life is just another commodity in abundant supply.

Ask anyone who lives in a city.

**************

Raman wiped his oily fingers on the outer wrapper of Lay’s Magic Masala and threw it away. Why couldn’t they make wrappers more absorbent, more tissue-like, so you didn’t have to spot the sides of your pants instead? As always, he felt that pull. That urgent knocking in the bottom of his bountiful bones. Advertising or marketing or some such wasteland of commercial creativity—that’s where he was meant to be. Group head. Marketing president. Creative director. He could see the toshed gold emblazoned name plate already. Soon. Very soon. But they’d have to pursue him. The truly talented never chased.

The platform was slushy with the polished slipperiness of fish basket sweat, that dirty bilious water that leaked from the edges. Raman squeaked as he entered the compartment—or rather, his shoes did as they heaved forward onto the high-stepper. Expensive sneakers came with an attitude: they sniggered at bad treatment. They too demanded equal rights like their leather contemporaries and aspired to walk on lush carpeted floors. And then it hit him full in the face. Raman raised his arms to shield himself, as if cowering from attack, but it was too late. He felt the full force of it, the intense vindication, the boisterous tang of heated armpits. His nostrils flared; he coughed, wheezed, as he tried to find a place under the fan. His eyes began watering, mist-filled, as the blades above him droned on. The air was too thick, too potent even for electricity. Raman moved to the door. It wasn’t much better. It seemed to be what everyone else had done.

‘What do you do?’

Raman looked up to see who was talking to him. He turned around. Still coughing, he looked down to be faced with a bobbing head.

‘What?’ asked Raman with a hint of alarm.

‘I mean, what do you do professionally?’

‘Why?’ Raman stared hard at the man. He remembered something, uncreased his brow and smiled gently. ‘Why?’ he asked pleasantly.

‘I’ve seen you somewhere,’ said the man plainly.

Raman had a theory: if you smiled, people were more inclined to be nice to you. Even if you had robbed, maimed, killed, or were about to. Smiling and lying went hand in hand. Scams, bust-ups, indiscretions, financial takeovers, political warfares, marriages had all succumbed to it. Well, as long as you didn’t grin shiftily, attracting suspicion. Lying was an art, really.

‘...Where?’ Raman stopped smiling. The man was still grinning gormlessly. ‘Where have you seen me?’

‘Aren’t you from TV?’

Raman’s eyes darted over the bristles of the little man’s moustache: unevenly patchy, hastily snipped, with bits of orange on one end. TV. Yes! He’d been on it. But how the hell did this twit remember? Five months on a game show. Prime time. 9 pm. In the audience. Well...what’d you know!

He used his best camera angle and pursed his lips. ‘Yes,’ said Raman, matter-of-factly. Life was suddenly everything he wanted it to be. He could bottle this moment and make it last forever. ‘And you?’ he asked.

‘Rahul Bhangari. BCom, CA, having business of hardware.’ The pudgy hand was outstretched. ‘Mobile, com-poo-ter, diary—electronic, latest models, CP209 mobile. With conference facility and micro-small earplug, water resistant, wireless. What you use?’

Marketing is a hard job in the world outside of trains. Working the phone, secretarial suck-ups, perspirational delays—almost as tough as dating. But here, if luck struck out, you just moved on to the next guy: on the right, left, back, or front, in the passageway. It was a breeze. Forget about call centers and rigging up your bio: No prior experience was required. Success rates were high. The lines used were the same, naturally. Everyone wanted to be from TV. No one ever was. But in a roomful of strangers, would you admit it? Other conversation hookers were Page 3, fashion shows, and nightclubs—altars of mass worship for everyone.

Raman gave an incomprehensible look. Far too many CPUs, OEMs, RAMs, hard and soft drives to take in at one time. He was confounded. It was all too overwhelming: the disabling motion of the train, the dancing pamphlets, and his controlled urge to fart. His eyes welled up.

‘Thanks,’ Raman murmured.

‘What com-poo-ter you use at home? The 568E Konkita with parallel folding speakers?’ The thick stubby fingers brushed open an extensive white folder.

There was only one other way to tackle this.

‘...Listen.’ Raman drew a deep breath and looked back to address the man. His body twitched. He peered at the man more closely.

‘You have place, my friend? Somewhere I can show you demonstration?’ The man’s thick upper lip was twitching, the nubby thumb subtly rubbing the outer flap of his crotch.

Oh, that’s another thing about the city. Everyone has a second job on the side. Everyone. But we’ll get to that later.

----

‘If I didn’t know you so well.’ You obviously couldn’t, or shouldn’t, or needn’t, Raman felt like barking back into the phone. It was one of those that came from the family of ‘I love you but...’ Yeah. Trust words to dampen things, to abuse your dependence on them. Just when you needed not to hear, they always came through. They softened as you got hard. Words ought to be banned.

There was a pause on the other end. Lola breathed in hard. Her concern was audible. She said, ‘You really need to think about this shopping trip because the more you don’t...’ It sounded as if she were biting the phone. Digging her front teeth in for an absolving answer.

‘Sure,’ said Raman. ‘I’ll think about it. Seriously.’

Another pause. Another asthmatic gulp of breath.

‘Yup. Okay,’ said Lola, hanging up.

And that was it. For today. But there’d be another later, Raman knew. Everyday conversations. That’s what they really were. Nobody should waste time trying to figure them out, solving their apparent ineptitude. There would always be another one to follow soon. And another. Every single day of your life. Things never looked up in this department.

Raman sighed. He hated his life. His miserable, inconsequential existence. It loomed before him and he knew someday, at the end of it all, there would be nothing to write about. At 35, his life had come to a standstill. A full stop. But something inside kept banging on, raging on, trying hard to get out. He would keep letting loose occasionally.

A thought flashed.

He pulled out his pad. Grabbed his pen. And sat, pen poised in mid-air as he conjured up an inspiration. What was that again? He tried delaying the thought abortion. ‘After a point you stop fighting life—and accept what it gives you. But where do you go from there?’ Deep hmm, he thought, penning it down and then putting down the pen in satisfaction. For several more minutes he lovingly stared at the pad hoping to add any discarded remnants. And then looked at that other magical source of inspiration—at that very moment in time before his eyes there appeared two sad, middle-aged women in pantyhose and black eye-masks with red stilettos. One longingly sucking a lolly, another brushing back her hair with a knife. A rubber dog, a bowl of fish, and a naked man in a tub. Yes, MTV made reality look preposterously dull.

Oh hell, it was Sunday. Lazily, Raman slouched into the curve of the sofa. When in doubt: scout. He bummed the remote hard for another music channel. Munni badnaam hui, darrlling... The song screeched. It drew out. It seemed to be coming out loud, from somewhere down below. Somewhere between the crack of his ass. Damn! The cell phone.

‘Hello?’ said Raman.

‘Darling, where are you?’ a sharp tone boomed back.

Shit! What interview had he missed? His boss never just called. On a Sunday. ‘On the couch. At home,’ Raman said, panic creeping into his voice.

‘No darling!’ The words buzzed among strange zing-like sounds. Raman pressed the receiver hard to his ear to check if she’d hung up. ‘Where are you!’

His mind whirred for an answer. It was a game show moment. His time was running out.

‘Have you seen today’s issue of India NOW!? So tacky!’ said Shaailaa.

‘Oh, of course,’ said Raman, with the delayed acknowledgement of a half nod. ‘I read their lead on that Sonali from Vijayawada. She’s becoming really hot in modelling. Shaailaa, we should do a piece with her on ‘What Makes Sonali So Hot’ before India NOW! even think about roping in her twin Monali and doing something like a ‘Haute Sisters’ piece where they both...’ Raman stopped to envision the contents of his scoop only to see the shiny black of his screen staring back at him. He was talking to himself. Shaailaa had hung up after making her literary statement. She rarely cared for addendums.

Moments of nothingness, hours spent daydreaming of who’s popular. The life of a journo was tough. He hated the word: Journo. What the hell? He wasn’t a hack claiming to be a reporter who did celebrity interviews, but pretended to be a writer waiting to be a novelist. He was a dignified wordsmith. His terms, his words. No puff pieces, no ego massages. On occasion, Raman needed this self-justification like an internal mantra that he kept repeating to himself for sanity. Or else crashing to earth from fourteen floors above was his destiny.

He had flirted with suicide once. With a bottle of Benadryl. He slept leisurely and woke up 18 hours later. It was another day, just like any other. Nobody noticed. No one ever asks ‘How’re you doing?’ and really expects an answer. A nod or a groan was indication enough. You were still breathing. No one had time for anything more.

As if imitating a scene in his head, Raman suddenly rammed his crotch into the cushion. First slowly, then forcefully. When he was alone, aggression descended. He loved the grazing playfulness of it, the plump softness massaging the protruding hardness, the edges of the mirror work inlay that felt like teeth. He used the tassels to gently massage his balls. He felt the tingle, that vibrating sting that readies you up. But something was missing; something was not quite still there. The ambience—it had to be as per the latest clip going on in his head: Raw Military Action II. With his raging hard-on in hand, Raman got up and flung open the bedroom windows. The outside greyness loomed dramatically. The dark clouds dominated. It was time. He pitched back on bended knees, and sprayed into the air with violence as a few pigeons fluttered past.

----

Excerpted with permission from Random House India. The book releases in early March on uRead.com at a discounted price of Rs 188. Click here to get your copy.

#farhad dadyburjor#farhad dadyburjor novel#how i got lucky#how i got lucky farhad dadyburjor#random house india#how i got lucky book excerpt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some Thoughts On Midnight's Children

“To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world.” – Saleem Sinai, Midnight's Children

How does one review the Booker of Bookers? I cannot possibly know. The task becomes all the more difficult when I realize I’m the minority who struggled to go beyond one third of the book the first time he picked it, many years ago.

Seven years on, when the release of the book’s film adaptation is underway, I attempted the task again, with much apprehension, but egged on by Deepa Mehta’s ensemble cast and colourful imagery.

Did I succeed? I’m not sure. Perhaps I like my prose to be a bit lighter and not as dense as Rushdie’s, but what impressed me thoroughly was the epic scale of events unfolding in the book and the stream of metaphors stitched effortlessly between the principal set of characters and the country that fathered them.

Midnight’s Children tells the story of Saleem Sinai, who is born at the stroke of midnight on the day of India’s independence, along with a thousand other children – hence the book’s namesake – who go on to discover that they have telepathic powers. Narrating his story when he’s turned thirty, the book blends magical realism with history, humour and an ear to the ground in charting Saleem’s life.

The reader is given a taste of the close parallels that run along as he remains handcuffed to the tumultuous history of India’s journey to independence, the devastating partition and the years that followed as India labored its way to becoming a republic.

Rushdie is a master at his craft and the manner in which he sets the stage for Saleem's arrival into this world, is an achievement in itself. You cannot resist turning the pages, and yet he continues teasing the reader with his bursts of self-consciousness – possibly a big reason why the book almost seems autobiographical. He's also a bit of a drifter and if there's any pet peeve about his narration, it is this. I had to jog back my memory (and some pages) to be reminded of what he was talking about in the first place.

I can’t possibly add much to the acclaim this book has already piled up over the years, except add my own experiences to the mix. And although I found the prose annoying at many places (large portions spread across the book that come across as too indulgent and pompous), I had no alternative but to give in. The story, I realized, is the ultimate glue that egged me on. The set of characters are so perfectly cast for the unfolding of an epic saga, that you’re willing to forgive the liberties Rushdie takes with our time, patience, and instead surrender to his style.

There is something as 'too-much-detailing, too much information' and it's something which Tolkein excels at, and in the same fashion, Rushdie’s writing almost seems to say, “I don’t care whether you like my style, but this is the way I’m going to tell it because it’s my story; you’re in my world.”

It’ll be interesting to see how Deepa Mehta’s film adaptation interprets his form. What could work for the viewer, is the film’s compelling story-line – it is perhaps the most grand metaphor you’ll ever read – but what may perhaps be lost in translation is Rushdie’s wickedly teasing and playful voice. It’s unique, and definitely gave something special to the world from the Indian sub-continent.

Midnight's Children is available in its film tie-in edition on uRead.com for Rs 333 (26% discount, free shipping in India).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Excerpt: Because Shit Happened - Harsh Snehanshu

On a fateful winter day, Amol Sabharwal, co-founder of one of the most ambitious startup ventures in the country, Yourquote.in, decides to quit. What makes Amol quit his own business venture just when it is on the brink of raising its first round of funding? Because Shit Happened gives you an insider’s peek into the big, bad entrepreneurial world of fame, betrayal, lust for power, greed, and unethical business practices. Based on the real-life story of the start-up that the author co-founded in 2010, this book will tell you what NOT to do in a start-up.

(Here's an excerpt from Because Shit Happened by author Harsh Snehanshu. Published by Random House India. Buy the book on uRead.com for Rs 112 - 25% OFF. Free shipping.).

Patna, Bihar

When I was twelve, I had a very serious conversation with my mother. I wanted to know the answer to a question that had been bothering me for the past few days.

‘Mom, will you and Daddy ever leave me?’ I asked her.

‘Yes, if we find a more obedient boy than you, then we definitely would,’ she said, her serious face increasing my worries with each passing minute. Then she suddenly broke into a huge smile and I knew there was nothing to worry about. She was only kidding!

‘Mom, seriously, please answer me,’ I persisted.

‘No, Amol. We will never leave you,’ she assured me.

But my curiosity was still not satiated and my question was not going to be bogged down by a simple yes or no.

‘Never ever?’ I asked once again.

‘No parent will ever leave his or her child, no matter what happens. Never ever,’ she said. Her eyes twinkled this time.

I smiled, took my cricket bat, and went outside to play gully cricket, imbibing her statement as the universal truth that was never going to change. The question never haunted me again. Well, not for ten years.

A decade later, when I became a parent to my baby—my start-up—the question resurfaced and drilled an irreparable hole in my heart. After raising my start-up from birth for two whole years, I left it. Yes, I left my child. And I never bothered to look back. Never ever.

The Spark

May 25, 2009

Glasgow, UK

Shades of blue painted my laptop screen. Like always, my eyes were glued to the screen. I re-read the address bar for the umpteenth time that day. It said www.facebook.com.

Sign up, connect and share with the people in your life.

It’s free and always will be.

I read the above lines twice. It was my first encounter with a mission statement of a company. And I was touched by its simplicity. I logged in, completely awestruck.

There was a dark blue bar on top which contained the logo of Facebook written in lowercase. No flashy fonts, no flashy colors. There was a notification box at the bottom right (yes, it used to be there in 2009!), something known as a News Feed in the centre, a few sponsored ads on the right, and my profile on the left. After assimilating whatever I saw, I came to a realization. That I frigging hated the damn website! Everyone could read my updates, which was so unlike the social network with the funny name that I was addicted to—Orkut. Whatever I wrote on my wall was visible to everybody. And whatever I was writing on my friend’s wall was visible to all our mutual friends. It seemed so sickening! All the privacy was suddenly turned into news for people who had absolutely no connection with it in the first place, thus the name ‘News Feed’.

I cursed the friends who spammed me with numerous mails asking me to join the damn site. Harassed, I wrote my first status.

I hate Facebook. It’s boring, disorganized, and does not respect privacy at all.

And I closed the tab.

*****

‘Hello sugar.’

Priya loved it when I called her sugar. She was the woman I was madly in love with. Back in India, she was counting the days left for my return to the country.

‘Hi boyfriend’, she said in her typically excited tone.

It had been almost one month since I last saw her face. I had come to Glasgow, Scotland, on a three-month summer internship program, and I still had two months to go. Almost everybody at IIT, just by virtue of being an IITian, aspired to get a sponsored internship in the second year, where one hoped of working less and travelling more. I was one of those lucky ones who got a fully sponsored, ‘academically stimulating’ research internship at the Optics group of the University of Glasgow.

‘Have you heard of this thing called Facebook?’ I asked her.

‘Huh, so my boyfriend gets the time from his busy schedule to call his oh-so-awesome girlfriend from the other end of the globe and the first thing he wants to know is whether I know about a frikkin social networking site! Aren’t you already too addicted to that Orkut thing of yours?’ she retaliated. Being one of those rare species who preferred the real world more than its virtual counterpart, she completely despised the concept of an online social network. Orkut had been her mortal enemy for getting more attention from me lately.

‘Wow, so you have heard of it! I thought you were technically imbecile,’ I remarked.

‘I always keep myself updated with the arrival of my competitors, especially when I have loyal friends like you who send me an invite to join it,’ she replied sharply, which, as I thought in my head, would have definitely been followed by a wink.

‘Smart. You would be glad to know that I don’t like her,’ I said.

‘Her? Who is she?’

‘Your rival, Facebook. I just posted my first update a couple of minutes ago.’

‘Yes, I saw that. I even ‘liked’ it along with three other people.’

‘Really? Which three?’

‘Pratik, Ravi, and another girl—Mary. Who is she?’ Priya asked curiously.

‘Well, she’s just a woman I have had the pleasure of spending a few nights with,’ I joked, hoping to fuel her anger even further. In the meanwhile, I unconsciously logged into the website that had sent me to hate trips an hour ago.

‘Is she blind?’

‘No, she is dumb like you. I’m going now; have to check my notifications,’ I said, my mouse pointer inadvertently moving towards the bottom right corner where number 3 popped up in a red voice-box. The hatred at first sight was immediately vaporized.

‘Hello, come again? You just told me you hated it,’ she said.

I was too engrossed in what was displaying on my computer screen to pay any heed to her, and so disconnected the call.

A moment later, number 3 changed to 4, with a wall post from Priya complimenting me: ‘You are the biggest jerk on this planet.’

I liked the post. And unknowingly, I started to like Facebook as well.

*****

Two days later, Orkut was history and Facebook became the next grand love affair of my life. Already an avid blogger, I could not find a better place to showcase my opinions, get friends and readers to read them, involve them in a discussion, and more than anything else, get appreciated for it in the form of ‘likes’. Such was my obsession with likes that I started coming up with something outrageously witty, or at times, profound or philosophical, just in hope of getting likes. Facebook became a mini-blog for me.

To Priya, I became a bigger jerk with each passing day since she would come to know about my well-being more via Facebook than through my awaited international calls—although the website did provide her with a medium to keep a constant tab on me.

It allowed her check my pictures in picturesque Scotland, including snaps of my fair-skinned female friends, three of whom seemed quite hot to her, as I could tell from her comments on the pictures.

On one of my only pictures with Mary, Priya made sure I would not be saved from embarrassment, commenting: ‘Why is that gadhi keeping her hand on your shoulders?’ which prompted Mary to follow-up with a question for me: ‘Hey Amol, what does gadhi mean?’ After two minutes of thinking for an apt answer, I replied: ‘It’s a Hindi word meaning “beautiful girl”.’ Mary instantly replied saying, ‘@Priya—Even you are a gadhi honey!’ If Facebook had an option to like comments back then, I would have definitely clicked it.

In the next seven days, I had posted over 25 status updates. More than 3 statuses a day. All of them were original, witty, or profound one-liners and could easily be classified as popular judging by the number of likes they managed to get, helping me outshine every other friend in my list. I wouldn’t be wrong in calling myself a Facebook addict. And the only fuel to ignite this addiction was likes, their number, and the happiness that followed.

However there was one problem. Though now Facebook works on the concept of a ‘timeline’, back then it sucked at archiving data. The chronological organization of the posts meant that my favorite one-liners, if they got too old, couldn’t be traced back immediately. I needed to click on older posts and go on and on to collect data. Even with the new timeline, I need to remember the exact date when I posted a particular quote to check it.

This posed a grave problem for me. And, this was the moment that gave me a sense of a great opportunity. I thought how Facebook was making people exercise their creativity but was unable to archive it properly. Moreover, there was no way that creativity could be monetized. Being a prolific blogger, I valued my creativity and didn’t like seeing it go to waste. I searched for websites where my one-liners could mint money for me; and if not the money, then at least the recognition that I was the creator.

I came across Twitter which was a fledgling website back then but was focussed more on updates and interactions than just quotes. Then there were micro-blogging websites, but none that concentrated on monetization or even giving some recognition to the inventor of the one-liner. I came across quotes websites, all of which archived famous peoples’ quotes. There was no room for the common man. Oddly enough, a lot of them listed many anonymous quotes. This infuriated me further as I realized that some common man who would have come up with that quote hadn’t been credited for it and was now forgotten. His name was probably buried along with an epitaph stating: ‘Here lived the man who would be remembered by nobody in future’.

Can’t common people get a chance to get famous? Can’t they be quoted? Can’t their words become immortal? Why is fame a prerequisite immortalize creativity? Thoughts like these clouded my mind.

Suddenly, I smelled a very viable business opportunity. I was going to do what no one had attempted so far. You see, I had to. The seed was implanted in my brain and I had to make a tree sprout out of it—come what may.

As I explored further, I realized that the time was apt. Thanks to Facebook (and later on, Twitter), common people had started writing one-liners, but there was no avenue where they could be archived or monetized or even recognized. Why would you need to quote Shakespeare, when you yourselves could come up with something apt to suit an occasion? What you say matters. You deserve to be quoted. Your quote matters. YourQuote. I checked the domain. The address was available. yourquote.in. It didn’t even take me a minute to confirm the booking. However, there was a little problem. I didn’t know how to ‘code’, that is, how to develop a website.

I thought that until I figured out a way to get the damn website made, I would run it as a blog. I was already an avid blogger, and knew it inside out. Within minutes, I started a blog and put down all my quotes in it.

I logged in my Facebook account to share the link of the blog with friends. On top of my News Feed was my friend Pratik’s update which struck me with its witty humour.

The root of all sins is…less than 1.

I googled the quote to check whether it was original or copied. It was an original one. I liked his post and immediately, I called him asking him to become the co-author of the blog. I didn’t share with him the bigger picture. He complied, published a bunch of his quotes on the blog. We had two authors now, including me, as I began hunting for more.

An hour later, I pinged my friend Vikram—one of my closest school friends—on Google Talk. He was on the other side of the globe, pursuing Computer Science in Punjab. He could tell from how thrilled I seemed that I was onto something new. Five minutes into the chat, I inducted him on board as the web developer for the website. He liked the idea but asked for some more time, around four to five months, to prepare himself for the task at hand. Having just passed his second year, he still wasn’t adept in programming to undertake the project of developing a social network. I gladly gave him the time he asked for, assuring him that I needed time to ideate as well.

I couldn’t sleep that night. I was dreaming with eyes wide open.

Late at night, Shardul, my co-intern from IIT whom I was sharing the room with, returned piss drunk state and dropped off to sleep. I didn’t need alcohol to remain intoxicated for the rest of my college life.

0 notes

Text

Eye of the Tiger: Thoughts on 'Life of Pi'

In a hot summer vacation, about two decades ago, the following line was a conversation starter:

"So, have you seen Jurassic Park?"

Cut to 2012 and the conversation starter has become:

"So, I hope you've seen Life of Pi?"

I'm making a bold assumption that most readers of this blog would have already seen the film by now - and hopefully made a scramble to get yourselves a copy of the book - and are prepared for what I'm about to share with you. Plenty of spoilers ahead.

But before that, I must tell you why this one's a significant book for me, personally. (No, not because it made me believe in God!)

Life of Pi first caught my attention thanks to a small but glowing review in a magazine for teens, JAM (edited by now-bestselling author Rashmi Bansal) almost eight years ago. Those were the days when I was still hooked to my Hardy Boys and Nancy Drews and hadn't quite graduated to reading novels. However, the premise of this book, explained in the plot summary on the back-cover really caught my attention (I still believe it is THE best plot summary ever written) and I eventually bought the book.

The rest, as they say, is history. I didn't just love the book, I became its evangelist, almost adamant about getting my friends to read it. I lent it to them without thinking twice whether they would return it or not. Most of my friends were equally bowled over by Martel's work and from then on, I came to be known as someone with a very good taste in books. (What to do. I was just lucky!)

But frankly speaking, Life of Pi, became the turning point of my reading life. Prior to it, Booker Prize winning books held no attraction for me, but Yann Martel's story indeed seemed different from the rest. It was unique, ambitious and most importantly, it made me believe in the power of great story-telling, satiating me with a sense of awesomeness from page to page, without the burden of language. The plot is universal and every man on this planet will want to know how Pi Patel survives for so many days on a lifeboat with a 250-pound Royal Bengal Tiger, without getting eaten up.

Revisiting this book, in it's brand new edition, published by Canon Gate, brought back many memories. I was 18 when I read the book for the first time. Large parts of the book were meditative - about God, religion, humanity and faith. These very themes, which didn't go down with my rebellious 18-year old self then, went down very well with the 26-year old me today who is coming to terms with adulthood and responsibilities.

When I'd picked up the book for the first time, I was expecting (not hoping) for a Rudyard Kipling-ish story where Richard Parker, the hyena, zebra and the orangutan suddenly start spouting words and end up making great conversation in the company of Pi Patel, a modern-day Mowgli, but thankfully it did not turn out that way. It's a wonderful, allegorical tale of survival in the wild waters of the Pacific, and despite involving a cast of just two main characters - at no point did I find it boring. Even in the second reading, my hands got clammy at all the right places - the sinking of the ship, the part when the hyena bites into the zebra, the unbelievable story of the island full of meerkats, and Pi's eventual arrival on the shores of Mexico...

Over the past few weeks, I've often been asked by my movie buff friends, whether they should read the book and then watch the film, or do it vice versa - and I've always advised them to opt for the former.

Viewers of the film will certainly find the 3D and CGI unlike anything they've seen before and Richard Parker's roar will long outstay the duration of the film, but to really GET WHAT MARTEL IS TRYING TO SAY, one HAS to read the book.

For example, the following portions, where Pi reminisces about Richard Parker's unceremonious departure after spending 220-odd days at sea with him, acquire new meaning upon revisiting the book, instantly choking me with tears:

"I've never forgotten him. Dare I say I miss him? I do. I miss him. I still see him in my dreams. They are nightmares mostly, but nightmares tinged with love. I still cannot understand how he could abandon me so unceremoniously, without any sort of goodbye, without looking back even once. That pain is like an axe that chops at my heart."

and perhaps the best one,

"What a terrible thing it is to botch a farewell. I am a person who believes in form, in the harmony of order. Where we can, we must give things a meaningful shape. For example - I wonder - could you tell my jumbled story in exactly one hundred chapters, not one more, not one less? I'll tell you, that's one thing I have about my nickname, the way the number runs on forever. It's important in life to conclude things properly. Only then can you let go. Otherwise you are left with words you should have said but never did, and your heart is heavy with remorse. That bungled goodbye hurts me to this day. I wish so much that I'd had one last look at him in the lifeboat, that I'd provoked him a little, so that I was on his mind. I wish I had said to him then - yes, I know, to a tiger, but still - I wish I had said, "Richard Parker, it's over. We have survived. Can you believe it? I owe you more gratitude than I can express I couldn't have done it without you. I would like to say it formally: Richard Parker, thank you. Thank you for saving my life. And now go where you must. You have known the confined freedom of a zoo most of your life; now you will know the free confinement of a jungle. I wish you all the best with it. Watch out for Man. He is not your friend. But I hope you will remember me as a friend. I will never forget you , that is certain. You will always be with me, in my heart. What is that hiss? Ah, our boat has touched sand. So farewell, Richard Parker, farewell. God be with you."

Life of Pi, is then, without doubt, one of the greatest stories ever told. And going by how Booker Prize winning titles are received in our country, this one's perhaps the most mainstream in its language and theme. This is definitely a book that you must have in your collection - not just for yourself, but for generations to come.

-

(Life of Pi is available on uRead.com for Rs 299 only. Click here to buy now. Free shipping, cash-on-delivery available in India.

A brand new film tie-in collector's edition is available for Pre-order. Click here for details and be amongst the first ones to receive a copy. Rs 419 only. Free shipping, cash-on-delivery available in India.)

#life of pi#yann martel#ang lee#man booker prize#life of pi review#life of pi book review#canon gate#richard parker#rashmi bansal

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This one's a wonderful meeting of minds. JK Rowling in conversation with Oprah Winfrey.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Excerpt: 'Bonsai Kitten' by Lakshmi Narayan

Sleeping With The Enemy

If you hear of me getting married, slap me. - Elizabeth Taylor

Today, husband dear came home early, and immediately proceeded to make his presence felt as lord and master of the domain by plonking himself in front of the TV, switching channels without so much as a by-your-leave and demanding immediate sustenance.

I began my role-playing of the ideal, devoted wife.

Serving up two large, hot samosas, I asked if he'd like an apple. The general rule of thumb is: If I offer an apple, he'd want a banana. And if I offer a banana, he'd want an apple. Since I was fresh out of apples, I offered an apple.

Swift came the recoil, "I'd rather have a banana!" Ooh! These small victories taste so sweet. You see, they're few and far between.

*****

Then I attempted my hand at chirpy chit-chat. "Do you like the samosas? I baked them instead of deep-frying. And I added some mint in the stuffing for extra flavour."

I hung back like a puppy, tail wagging, tongue hanging out, trawling for that pat on the back. Forehead puckered in ferocious concentration, he picked up a limp and forgotten potato crisp from the table, folded it meticulously into four to form a perfect triangle and clamped his chompers on it with evident anticipation.

Five whole minutes passed before he answered, "Any mail for me?"

Some people never learn. I’m one of them. Forever a glutton for punishment. After all these years, I still hope to merit a word of praise. Even a left-handed one would do nicely.

Actually, today wasn't too bad. He'd at least thought for a good five minutes before erasing me out…because his normal response to my queries is to turn the pages of the book/newspaper he’s reading and pretend I’m the Invisible Woman.

I’m like the cat from Alice in Wonderland, dematerialized, but for that cheesy, half-arsed grin on my face.

*****

Confabulations with The Great Communicator being what it is, I've become a pastmaster at playing dumb charade. That is, I carry on the charade of being dumb while having the real dialogue in my head.

As when:

He: (Expression like he’s encountered something fetid) "What’s this? Sambaar* or

rasam*? I can’t tell by the consistency."

Me: (Submissively) "It’s vatta kulambu*." (In my head) ‘If you sink your beak any

deeper into the bowl, you’ll find out soon enough!’

Or

He: (Loudly, showing off his superior knowledge in front of our mainly foreign guests) "I said, GET THE COINTREAU! Not the Tia Maria. It’s the square shaped bottle to the left."

Me: (Silently, through gritted teeth) ‘Stop being a phoney gora, you pi-dog! I know as much about liqueurs as you.’

*****

Every wife should play this incredibly gratifying game of splenetic rant in her head. Since it’s tacit, you don’t have to face the aftermath of broken spirits and broken hearts. But you get your money’s worth.

It's been like that, from the first night we spent together.

Conversation: Nil.

Action: One sided.

When he clambered aboard with that do-or-die expression, holding his hose in his hand with the dedication of a gardener trying to water his prize roses. Then he remembered that he first had to turn me on. So he grabbed my right breast and twisted it clockwise four times. Ditto, anti-clockwise. A reprise with the other boob.

Convinced that I was now writhing in ecstasy after this splendid execution of foreplay, he dipped his wick into me with the precision of a dive bomber.

Mission impossible: Accomplished.

Achievement: Penetration.

Loss: Making love.

(Excerpts shared with permission from the publisher, Leadstart Publishing.)

Bonsai Kitten is available on uRead.com for Rs 154 only (21% OFF). Free shipping, cash-on-delivery available in India. Low cost shipping fees worldwide. To buy the book, click here.

0 notes

Text

Book Review: Operation Lipstick

By Anubhav Mehta

Pia Heikkila's Operation Lipstick: Mission For Mr Right brings good ole' chick-lit in a new setting - war ravaged Afghanistan, courtesy its main protagonist, Anna Sanderson who is a thirty-something, single, horny foreign correspondent for UK-based television network. After a series of run-ins with her dream man, Mark (Mr Delectable, she calls him), she is convinced she has fallen for him (and so has he, we're told) until an incident involving her friend Kelly and her ex-boyfriend opens up the pandora's box about a major arms embezzlement deal involving the Taliban.

If Anna is able to get to the root of the story and catch the guilty red-handed for her cameras, she could end up with the greatest scoop of her lifetime.

It isn't a bad setting for a racy action-packed adventure involving a female protagonist. The first half of the book is a bit of a drag and the socialite parties, the clinking of the glasses tend to feel a bit repetitive, but the narration does strike a chord in the second half, involving some major action scenes and a far closer look, and a more sensitive look at Afghan people and the armed forces. Also, we're not told much about Mark at all, except that he's got killer looks and that he works for in the security business. That, and his ability to surface wherever our damsel-in-distress is seen (or stuck and needs rescuing) is what works for Anna.

Pia's writing is fluid, punctuated with good doses of guffaw generating humour and a-la Fifty Shades there's also cringe inducing fantasy about an orgy with soldiers at the gymnasium. A major weakness, I felt, is the book's tendency to give us the impression that Anna as a journalist who uses her sexuality far too prominently in order to get the information she wants from her sources. A roll-in-the-hay seems to be in order, if she wants to unearth classified information from sex-starved white men in uniform. It seems too easy and too obvious a way out for a journalist, re-affirming some misplaced and infamous cliches about people working in the media.

This book's good for a quick-read over the weekend, or on the flight.

Rating: 2.5 / 5 (Not Bad)

Available here for Rs 183 / $3.39 on uRead.com. For sale in the Indian sub-continent and Middle East. Free shipping in India and low-cost shipping fees worldwide.

Published by Ebury Press | Random House India

0 notes

Text

Dracula Special: Why does vampire fiction still thrill?

Pictured above: Bram Stoker

On the eve of Halloween, Joan Acocella puts her finger on Dracula and finds out what makes vampire fiction so irresistible.

“Unclean, unclean!” Mina Harker screams, gathering her bloodied nightgown around her. In Chapter 21 of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” Mina’s friend John Seward, a psychiatrist in Purfleet, near London, tells how he and a colleague, warned that Mina might be in danger, broke into her bedroom one night and found her kneeling on the edge of her bed. Bending over her was a tall figure, dressed in black. “His right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Her white nightdress was smeared with blood, and a thin stream trickled down the man’s bare breast which was shown by his torn-open dress. The attitude of the two had a terrible resemblance to a child forcing a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk to compel it to drink.” Mina’s husband, Jonathan, hypnotized by the intruder, lay on the bed, unconscious, a few inches from the scene of his wife’s violation.

Later, between sobs, Mina relates what happened. She was in bed with Jonathan when a strange mist crept into the room. Soon, it congealed into the figure of a man—Count Dracula. “With a mocking smile, he placed one hand upon my shoulder and, holding me tight, bared my throat with the other, saying as he did so: ‘First, a little refreshment to reward my exertions . . .’ And oh, my God, my God, pity me! He placed his reeking lips upon my throat!” The Count took a long drink. Then he drew back, and spoke sweet words to Mina. “Flesh of my flesh,” he called her, “my bountiful wine-press.” But now he wanted something else. He wanted her in his power from then on. A person who has had his—or, more often, her—blood repeatedly sucked by a vampire turns into a vampire, too, but the conversion can be accomplished more quickly if the victim also sucks the vampire’s blood. And so, Mina says, “he pulled open his shirt, and with his long sharp nails opened a vein in his breast. When the blood began to spurt out, he . . . seized my neck and pressed my mouth to the wound, so that I must either suffocate or swallow some of the—Oh, my God!” The unspeakable happened—she sucked his blood, at his breast—at which point her friends stormed into the room. Dracula vanished, and, Seward relates, Mina uttered “a scream so wild, so ear-piercing, so despairing . . . that it will ring in my ears to my dying day.”

That scene, and Stoker’s whole novel, is still ringing in our ears. Stoker did not invent vampires. If we define them, broadly, as the undead—spirits who rise, embodied, from their graves to torment the living—they have been part of human imagining since ancient times. Eventually, vampire superstition became concentrated in Eastern Europe. (It survives there today. In 2007, a Serbian named Miroslav Milosevic—no relation—drove a stake into the grave of Slobodan Milosevic.) It was presumably in Eastern Europe that people worked out what became the standard methods for eliminating a vampire: you drive a wooden stake through his heart, or cut off his head, or burn him—or, to be on the safe side, all three. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, there were outbreaks of vampire hysteria in Western Europe; numerous stakings were reported in Germany. By 1734, the word “vampire” had entered the English language.

In those days, vampires were grotesque creatures. Often, they were pictured as bloated and purple-faced (from drinking blood); they had long talons and smelled terrible—a description probably based on the appearance of corpses whose tombs had been opened by worried villagers. These early undead did not necessarily draw blood. Often, they just did regular mischief—stole firewood, scared horses. (Sometimes, they helped with the housework.) Their origins, too, were often quaint. Matthew Beresford, in his recent book “From Demons to Dracula: The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth” (University of Chicago; $24.95), records a Serbian Gypsy belief that pumpkins, if kept for more than ten days, may cross over: “The gathered pumpkins stir all by themselves and make a sound like ‘brrl, brrl, brrl!’ and begin to shake themselves.” Then they become vampires. This was not yet the suave, opera-cloaked fellow of our modern mythology. That figure emerged in the early nineteenth century, a child of the Romantic movement.

In the summer of 1816, Lord Byron, fleeing marital difficulties, was holed up in a villa on Lake Geneva. With him was his personal physician, John Polidori, and nearby, in another house, his friend Percy Bysshe Shelley; Shelley’s mistress, Mary Godwin; and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont, who was angling for Byron’s attention (with reason: she was pregnant by him).

The weather that summer was cold and rainy. The friends spent hours in Byron’s drawing room, talking. One night, they read one another ghost stories, which were very popular at the time, and Byron suggested that they all write ghost stories of their own. Shelley and Clairmont produced nothing. Byron began a story and then laid it aside. But the remaining members of the summer party went to their desks and created the two most enduring figures of the modern horror genre.

Mary Godwin (pictured above), eighteen years old, began her novel “Frankenstein” (1818), and John Polidori (pictured below) apparently following a sketch that Byron had written for his abandoned story, wrote “The Vampyre: A Tale” (1819).

In Polidori’s narrative, the undead villain is a proud, handsome aristocrat, fatal to women. (Some say that Polidori based the character on Byron.) He’s interested only in virgins; he sucks their necks; they die; he lives. The modern vampire was born.

The public adored him. In England and France, Polidori’s tale spawned popular plays, operas, and operettas. Vampire novels appeared, the most widely read being James Malcolm Rymer’s “Varney the Vampire,” serialized between 1845 and 1847. “Varney” was a penny dreadful, and faithful to the genre. (“Shriek followed shriek. . . . Her beautifully rounded limbs quivered with the agony of her soul. . . . He drags her head to the bed’s edge.”) After “Varney” came “Carmilla” (1872), by Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu, an Irish ghost-story writer. “Carmilla” was the mother of vampire bodice rippers. It also gave birth to the lesbian vampire story—in time, a plentiful subgenre. “Her hot lips traveled along my cheek in kisses,” the female narrator writes, “and she would whisper, almost in sobs, ‘You are mine, you shall be mine.’ ” “Varney” and “Carmilla” were low-end hits, but vampires penetrated high literature as well. Baudelaire wrote a poem, and Théophile Gautier a prose poem, on the subject.

Then came Bram (Abraham) Stoker. Stoker was a civil servant who fell in love with theatre in his native Dublin. In 1878, he moved to London to become the business manager of the Lyceum Theatre, owned by his idol, the actor Henry Irving. On the side, Stoker wrote thrillers, one about a curse-wielding mummy, one about a giant homicidal worm, and so on. Several of these books are in print, but they probably wouldn’t be if it were not for the fame—and the afterlife—of Stoker’s fourth novel, “Dracula” (1897). The first English Dracula play, by Hamilton Deane, opened in 1924 and was a sensation. The American production (1927), with a script revised by John L. Balderston and with Bela Lugosi in the title role, was even more popular. Ladies were carried, fainting, from the theatre. Meanwhile, the films had begun appearing: notably, F. W. Murnau’s silent “Nosferatu” (1922), which many critics still consider the greatest of Dracula movies, and then Tod Browning’s “Dracula” (1931), the first vampire talkie, with Lugosi navigating among the spiderwebs and intoning the famous words “I do not drink . . . wine.” (That line was not in the book. It was written for Browning’s movie.) Lugosi stamped the image of Dracula forever, and it stamped him. Thereafter, this ambitious Hungarian actor had a hard time getting non-monstrous roles. He spent many years as a drug addict. He was buried in his Dracula cloak.

From that point to the present, there have been more than a hundred and fifty Dracula movies. Roman Polanski, Andy Warhol, Werner Herzog, and Francis Ford Coppola all made films about the Count. There are subgenres of Dracula movies: comedy, pornography, blaxploitation, anime. There is also a “Deafula,” for the hearing-impaired: the characters conduct their business in American Sign Language while the lines are spoken in voice-over. After film, television, of course, took on vampires. “Dark Shadows,” in the nineteen-sixties, and “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” in the nineties, were both big hits. Meanwhile, the undead have had a long life in fiction. Anne Rice’s “The Vampire Chronicles” and Stephen King’s “ ’Salem’s Lot” are the best-known recent examples, but one source estimates that the undead have been featured in a thousand novels.

Today, enthusiasm for vampires seems to be at a new peak. Stephenie Meyer’s “Twilight” novels, for young adults (that is, teen-age girls), have sold forty-two million copies worldwide since 2005. The first of the film adaptations, released late last year, made a hundred and seventy-seven million dollars in its initial seven weeks. Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse novels (“Dead Until Dark,” plus seven more), about a Louisiana barmaid’s passion for a handsome revenant named Bill, were bought by six million people, and generated the HBO series “True Blood,” which had its début last year and will be back in June. Also from last year was the haunting Swedish movie “Let the Right One In,” in which a twelve-year-old boy, Oskar, falls in love with a mysterious girl, Eli, who has moved in next door. She, too, is twelve, she tells Oskar, but she has been twelve for a long time. A new Dracula novel, co-authored by the fragrantly named Dacre Stoker (a great-grandnephew of Bram), will be published in October by Dutton. The movie rights have already been sold.

The past half century has also seen a rise in vampire scholarship. In the nineteen-fifties, Freudian critics, addressing Stoker’s novel, did what Freudians did at that time. Today’s scholars, intent instead on politics—race, class, and gender—have feasted at the table. Representative essays, reprinted in a recent edition of “Dracula,” include Christopher Craft’s “ ‘Kiss Me with Those Red Lips’: Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ ” and Stephen D. Arata’s “The Occidental Tourist: ‘Dracula’ and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization.”

Other writers have produced fantastically detailed annotated editions of Stoker’s “Dracula.” The first of these, “The Annotated Dracula” (1975), by Leonard Wolf, a Transylvanian-born horror scholar, dealt, for example, with the scene of Dracula’s assault on Mina by giving us the Biblical sources of “unclean, unclean” and “flesh of my flesh”; by cross-referencing “my bountiful wine-press” to an earlier passage, about Transylvanian viniculture; by noting, apropos of Dracula’s opening a vein in his chest, that this recalls an old myth about the pelican feeding its young with blood from its bosom; by telling us that the vein Dracula slashed must have been the superficial intercostal; by exclaiming over the sexual ambiguity of the scene (“Just what is going on here? A vengeful cuckoldry? A ménage à trois? Mutual oral sexuality?”), and so on. None of this information is needed by the first- or second-time reader of “Dracula.” Indeed, it would be a positive hindrance, draining away the suspense that Stoker worked so hard to build.

The fullness of Wolf’s commentary did not discourage others. In 1979, a second annotated edition came out, and in 1998 a third. Last October, a fourth—“The New Annotated Dracula,” by Leslie Klinger, a Los Angeles tax and estate lawyer who has a sideline editing Victorian literature—was published by Norton ($39.95). What could Klinger have found to elucidate that his predecessors didn’t? Plenty. In the scene of Mina’s encounter with Dracula, for example, he honorably cites the earlier editions, and then he goes on to alert us to a punctuation error; to conjecture, revoltingly, about the source of the mist in which Dracula enters Mina’s bedroom (“Perhaps this was not a vapor but rather a milky substance expressed from Dracula’s body”); to speculate that Jonathan Harker’s excitement, upon awakening from his swoon, may be a form of sexual arousal; and to question the medical accuracy of Stoker’s claim that Harker’s hair turns white as he listens to Mina’s story: “In fact, whitening is caused by a progressive decline in the absolute number of melanocytes (pigment-producing cells in the skin, hair, and eye), which normally decrease over time.” Even that old sentimental convention does not get past him.

What is all this about? Why do publishers think that readers will care? One could say that “Dracula,” like certain other works—“Alice in Wonderland,” the Sherlock Holmes stories (both, like Klinger’s “Dracula,” published in Norton’s Annotated Editions series; Klinger was the editor of the Holmes)—is a cult favorite. But why does the book have a cult? Well, cults often gather around powerful works of the second rank. Fans feel that they have to root for them. What, then, is the source of “Dracula” ’s power? A simple device, used in many notable works of art: the deployment of great and volatile forces within a very tight structure.

The narrative method of “Dracula” is to assemble a collage of purportedly authentic documents, most of them in the first person. Many of the materials are identified as excerpts from the diaries of the main characters. In addition, there are letters to and from these people—but also from lawyers, carting companies, and Hungarian nuns—plus telegrams, “newspaper” clippings, and a ship’s log. This multiplicity of voices gives the book a wonderful liveliness. A long horror story could easily become suffocating. (That is one of the reasons that Poe’s tales are tales, not novels.) “Dracula,” in a regular, unannotated edition, runs about four hundred pages, but it is seldom tedious. It opens with four chapters from the diary of Jonathan Harker describing his visit, on legal business—he is a solicitor—to the castle of a certain Count Dracula, in Transylvania, and ending with Harker howling in horror over what he found there. Then we turn the page, and suddenly we are in England, reading a letter from Mina—at that point, Harker’s fiancée—bubbling to her friend Lucy Westenra about how she’s learning shorthand so that she can be useful to Jonathan in his work. This is a salutary jolt, and also witty. (Little does Mina know how Jonathan’s work is going at that juncture.) The alternation of voices also lends texture. It’s as if we were turning an interesting object around in our hands, looking at it from this angle, then that. And since the story is reported by so many different witnesses, we are more likely to believe it.

In addition, we are given the pleasure of assembling the pieces of a puzzle. No one narrator knows all that the others have told us, and this allows us to read between the lines. One evening, as Mina is returning to a house she is sharing with Lucy in Whitby, a seaside resort in Yorkshire, she sees her friend at the window, and by her side, on the sill, “something that looked like a good-sized bird.” How strange! Mina thinks. It’s not strange to us. By then we know that the “bird” is a bat—one of the Count’s preferred incarnations. (Dracula will destroy Lucy before turning to Mina.) Such counterpoint, of course, increases the suspense. When are these people going to figure out what is going on? Finally, most of the narration is not just first person but on-the-moment, and therefore unglazed by memory. “We are to be married in an hour,” Mina writes to Lucy as she sits by Jonathan’s bed in a Budapest hospital. (That’s where he landed, with a brain fever, after escaping from Castle Dracula.) He’s sleeping now, Mina says. She’ll write while she can. Oops! “Jonathan is waking!” She must break off. This minute-by-minute recording, as Samuel Richardson, its pioneer (in “Pamela”), discovered a century and a half earlier, lends urgency—you are there!—and, again, it seems a warrant of truth.

But the narrative method is not the only thing that provides a tight receptacle for the story. Most of this tale of the irrational is filtered through minds wedded to rationalism. “Dracula” has what Noël Carroll, in “The Philosophy of Horror” (1990), called a “complex discovery plot”—that is, a plot that involves not just the discovery of an evil force let loose in the world but the job of convincing skeptics (which takes a lot of time, allowing the monster to compound his crimes) that such a thing is happening. No people, we are told, were more confident than the citizens of Victorian England. The sun never set on their empire. They were also masters of science and technology. “Dracula” is full of exciting modern machinery—the telegraph, the typewriter, the “Kodak”—and the novel has an obsession with railway trains, probably the nineteenth century’s most crucial invention. The new world held no terrors for these people. Nevertheless, they were bewildered by it, because of its challenge to religious faith, and to the emotions religion had taught: sweetness, comfort, reverence, resignation.

That crisis is recorded in work after work of late-nineteenth-century fiction, but never more forcibly than in “Dracula.” In the opening pages of the novel, Harker, on his way to Castle Dracula, has arrived in Romania. He complains of the lateness of the trains. He describes a strange dish, paprika hendl, that he was given for dinner in a restaurant. But he is English; he can handle these things. He does not yet know that the man he is going to visit has little concern for timetables—the Count has lived for hundreds of years—and dines on something more peculiar than paprika hendl. Even when the evidence is in front of Harker’s face, he cannot credit it. The coachman driving him to Castle Dracula (it is the Count, in disguise) is of a curious appearance. He has pointed teeth and flaming red eyes. This makes Harker, in his words, feel “a little strangely.” Days pass, however, before he forms a stronger opinion. The other characters are equally slow to get the point. When Professor Abraham Van Helsing, the venerable Dutch physician who becomes the head of the vampire-hunting posse, suggests to his colleague John Seward that there may be a vampire operating in their midst, Seward thinks Van Helsing must be going mad. “Surely,” he protests, “there must be some rational explanation of all these mysterious things.” Van Helsing counters that not every phenomenon has a rational explanation: “Do you not think that there are things in the world which you cannot understand, and yet which are?” Throughout the novel, these self-assured people have to be convinced, with enormous difficulty, that there is something beyond their ken.

According to Nina Auerbach, in “Our Vampires, Ourselves” (1995), Dracula’s crimes are merely symbols of the real-life sociopolitical horrors facing the late Victorians. One was immigration. At the end of the century, Eastern European Jews, in flight from the pogroms, were pouring into Western Europe, thereby threatening to dilute the pure blood of the English, among others. Dracula, too, is an émigré from the East. Stoker spends a lot of words on the subject of blood, and not just when Dracula extracts it. Fully four of the book’s five vampire-hunters have their blood transfused into Lucy’s veins, and this process is recorded with grisly exactitude. (We see the incisions, the hypodermics.) So Stoker may in fact have been thinking of the racial threat. Like other novels of the period, “Dracula” contains invidious remarks about Jews. They have big noses, they like money—the usual.

At that time, furthermore, people in England were forced, by the scandal of the Oscar Wilde trials (1895), to think about something they hadn’t worried about before: homosexuality. Many scholars have found suggestions of homoeroticism in “Dracula.” Auerbach, by contrast, finds the book annoyingly heterosexual. Earlier vampire tales, such as Polidori’s story and “Carmilla,” made room for the mutability of erotic experience. In those works, sex didn’t have to be man to woman. And it didn’t have to be outright sex—it might just be fervent friendship. As Auerbach sees it, Stoker, spooked by the Wilde case, backed off from this rich ambiguity, thereby impoverishing vampire literature. After him, she says, vampire art became reactionary. This echoes Stephen King’s statement that all horror fiction, by pitting an absolute good against an absolute evil, is “as Republican as a banker in a three-piece suit.”

According to some critics, another thing troubling Stoker was the New Woman, that turn-of-the-century avatar of the feminist. Again, there is support for this. The New Woman is referred to dismissively in the book, and the God-ordained difference between the sexes—basically, that women are weak but good, and men are strong but less good—is reiterated with maddening persistence. On the other hand, Mina, the novel’s heroine, and a woman of unquestioned virtue, looks, at times, like a feminist. She works for a living, as a schoolmistress, before her marriage, and the new technology, which should have been daunting to a female, holds no mysteries for her. She’s a whiz as a typist—a standard New Woman profession. Also, she is wise and reasonable—male virtues. Nevertheless, her primary characteristic is a female trait: compassion. (At one point, she even pities Dracula.) Stoker, it seems, had mixed feelings about the New Woman.

Whether or not politics was operating in Stoker’s novel, it is certainly at work in our contemporary vampire literature. Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse series openly treats vampires as a persecuted minority. Sometimes they are like black people (lynch mobs pursue them), sometimes like homosexuals (rednecks beat them up). Meanwhile, they are trying to go mainstream. Sookie’s Bill has sworn off human blood, or he’s trying; he subsists on a Japanese synthetic. He registers to vote (absentee, because he cannot get around in daylight). He wears pressed chinos. This is funny but also touching. In “The Vampire Chronicles,” Anne Rice also seems to regard her undead as an oppressed group. Their suffering is probably, at some level, a story about aids. All this is a little confusing morally. How can we have sympathy for the Devil and still regard him as the Devil? That question seems to have occurred to Stephenie Meyer, who is a Mormon. Edward, the featured vampire of Meyer’s “Twilight,” is a dashing fellow, and Bella, the heroine, becomes his girlfriend, but they do not go to bed together (because of the conversion risk). Neither should you, Meyer seems to be saying to her teen-age readers. They are compensated by the romantic fever that the sexual postponement generates. The book fairly heaves with desire.

But in Stoker’s time no excitement needed to be added. Sex outside marriage was still taboo, and dangerous. It could destroy a woman’s life—a man’s, too. (Syphilis was a major killer at that time. One of Stoker’s biographers claimed that the writer died of it.) In such a context, we do not need to look for political meaning in Dracula’s transactions with women. The meaning is forbidden sex—its menace and its allure. The baring of the woman’s flesh, her leaning back, the penetration: reading of these matters, does one think about immigration?

The novel is sometimes close to pornographic. Consider the scene in which Harker, lying supine in a dark room in Dracula’s castle, is approached by the Count’s “brides.” Describing the one he likes best, Harker says that he could “see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips,” and hear “the churning sound of her tongue as it licked her teeth.” It should happen to us! Harker is not the only one who does not object to a vampire overture. In Chapter 8, Lucy describes to Mina her memory of how, on a recent night, she met a tall, mysterious man in the shadow of the ruined abbey that looms over Whitby. (This was her first encounter with Dracula.) She speaks of her experience frankly, without shame, because she thinks it was a dream. She ran through the streets to the appointed spot, she says: “Then I have a vague memory of something long and dark with red eyes . . . and something very sweet and very bitter all around me at once; and then I seemed sinking into deep green water, and there was a singing in my ears, as I have heard there is to drowning men . . . then there was a sort of agonizing feeling, as if I were in an earthquake.” This is thrilling: her rushing to the rendezvous, her sense of something both sweet and bitter, then the “earthquake.” But Lucy is a flighty girl. The crucial testimony is that of Mina, after Dracula’s attack on her. “I did not want to hinder him,” this honest woman says. Her statement is echoed by the unsettling notes of tenderness in Seward’s description of the event: the kitten at the saucer of milk; Mina’s resemblance, with her face at Dracula’s breast, to a nursing baby. The mind reels.

“Dracula” is full of faults. It is way overfull. Many scenes are superfluous. The novel is replete with sentimentality, and with oratory. Van Helsing cannot stop making soul-stirring speeches to his fellow vampire-hunters. “Do we not see our duty?” he asks. “We must go on,” he urges them. “From no danger shall we shrink.” His listeners grasp one another’s hands and kneel and swear oaths and weep and flush and pale.

To these tiresome characteristics of Victorian fiction, Stoker adds problems all his own. The on-the-spot narration forces him, at times, into ridiculous situations. In Chapter 11, Lucy has a hard night. First, a wolf crashes through her bedroom window, splattering glass all over. This awakens her mother, who is in bed with her. Mrs. Westenra sits up, sees the wolf, and drops dead from shock. Then, to make matters worse, Dracula comes in and sucks Lucy’s neck. What does she do when that’s over with? Call the police? No. She pulls out her diary, and, sitting on her bed next to the rapidly cooling body of her mother, she records the episode, because Stoker needs to tell the reader about it.

None of this, however, outweighs the strengths of the novel, above all, its psychological acuity. The last quarter of the book, where the vampire-hunters, after the attack on Mina, go after Dracula in earnest, is very subtle, because at that point Mina’s dealings with the fiend have rendered her half vampire. At times, she is coöperating with her rescuers. At other times, she is colluding with Dracula. She is a double agent. Her friends know this; she knows it, too, and knows that they know; they know that she knows that they know. This is complicated, and not always tidily worked out, but we cannot help but be impressed by Stoker’s representation of the amoral contrivances of love, or of desire. In this bold clarity, “Dracula” is like the work of other nineteenth-century writers. You can complain that their novels were loose, baggy monsters, that their poems were crazy and unfinished. Still, you gasp at what they’re saying: the truth.

Each of the annotated editions of “Dracula” has had its claim to attention. Leonard Wolf’s “The Annotated Dracula,” with six hundred notes, was the first, and it also did the job—which somebody had to do eventually—of picking through the psychoneurotic aspects of the novel. The next version, “The Essential Dracula,” edited by Raymond T. McNally and Radu Florescu, had its own originality. These two history professors from Boston College had unearthed Stoker’s working notes for the novel. They drew no important conclusions from that source, but never mind. They had a sexy new theory: that Stoker based the character of Dracula on a historical personage, Vlad Dracula—also known as Vlad Tepes—a fifteenth-century Walachian prince who, in defending his homeland against the Turks, acquired a reputation for cruelty unusual even among warriors of that period. Tepes means “the Impaler.” Vlad’s preferred method of dealing with enemies was to skewer them, together with their women and children, on wooden stakes. A fifteenth-century woodcut shows him dining at a table set up outdoors so that he could watch his prisoners wriggle to their deaths. McNally and Florescu’s theory gave journalists a lot of exciting things to write about, and their articles were featured: if it bleeds, it leads. As a result, “The Essential Dracula” was very popular. (To add to the fun, Florescu claimed that he was an indirect descendant of Vlad.) The Vlad hypothesis has since been discredited. As scholars have figured out, Stoker, while working on “Dracula,” read, or read in, a book that discussed Vlad, whereupon he changed his villain’s name from Count Wampyr to Count Dracula, and moved him from Austria to Transylvania, which borders on Walachia. He picked up other details, too, but not many. This has not put later writers off Vlad’s story. Matthew Beresford, in “From Demons to Dracula,” acknowledges that Stoker’s character “was not modeled, to any great extent, on Vlad Dracula.” Yet he offers a whole chapter on the Walachian prince, including a long description of impalement methods, complete with illustrations. After reading this, you could impale someone yourself.

In 1998 came “Bram Stoker’s Dracula Unearthed,” by Clive Leatherdale, a Stoker scholar. This book did not get much attention, but it holds the record for annotation: thirty-five hundred notes, totalling a hundred and ten thousand words. Leatherdale’s edition was also remarkable for its practice—common among fans, if not editors, of cult books—of treating the novel as if it were fact rather than fiction. When Harker, invading the cellar of Castle Dracula, finds the Count sleeping in his dirt-filled coffin, Leatherdale’s note asks, “Is he lying on damp earth in his everyday clothes, or in his night-clothes, with no sheeting to prevent earth-stains?” This is a creature who has lived for centuries, and can fly, and raise storms at sea, and Leatherdale is worried about whether he’s going to get his clothes dirty? The practice of “Dracula” annotation is both quite serious (Leatherdale, like the others, did a lot of work) and also, unashamedly, an amusement. It is an exercise in showing off—a demonstration of the editor’s erudition, energy, interests—and a confession of love for the text.

Leslie Klinger, in his new annotated edition, claims that he has fresh material to go on. He has examined Stoker’s typescript, which is owned by a “private collector.” This source, he says, has yielded “startling results.” In fact, like McNally and Florescu with Stoker’s working notes, Klinger draws no important conclusions from his archival discovery, and he admits that he spent only two days studying the typescript. As with the McNally-Florescu version, however, the real sales angle of this edition is not a new source but a new theory. Klinger not only assumes, like Leatherdale, that all the events narrated in the novel are factual; he offers a hypothesis as to how Stoker came to publish them. Here goes. Harker, a real person (with a changed name), like everyone else in the book, gave his diary, together with the other documents that constitute the novel, to Bram Stoker so that Stoker might alert the English public that a vampire named Dracula, also real, was in their midst. Stoker agreed to issue the warning. But then Dracula got wind of this plan, whereupon he contacted Stoker and used on him the methods of persuasion famously at his disposal. Dracula decided that it was too late to suppress the Harker documents entirely, so instead he forced Stoker to distort them. He sat at the desk with Stoker and co-authored the novel, changing the facts in such a way as to convince the public that Dracula had been eliminated. That way, the Count could go on, unmolested, with his project of taking over the world.

Many of Klinger’s fifteen hundred notes are devoted to revealing this plot. When Stoker makes a continuity error, or fails to supply verifiable information, this is part of the coverup. The book says that Dracula’s London house is at 347 Piccadilly, but in the eighteen-nineties the only houses on that stretch of Piccadilly that would have answered Stoker’s description were at 138 and 139. Clearly, Klinger says, Stoker is protecting the Count. Then, there’s a problem about the hotel where Van Helsing is staying. In Chapter 9 it’s the Great Eastern; in Chapter 11 it’s the Berkeley. Again, Klinger concludes, Stoker is covering his characters’ traces. He altered the name of the hotel—presumably, he had to prevent readers from running over to the place and checking the register—but then he forgot and changed the name again.

At first, you think that maybe Klinger’s book is not actually an annotated edition of “Dracula” but, rather, like Nabokov’s “Pale Fire,” a novel about a paranoid, in the form of an annotated edition. But no: Klinger, in his introduction, lays out his conspiracy theory without qualification. So are we to understand that he himself is a maniac, whose delusions the editors at Norton thought it might be interesting to publish?