Photo

Blue Note Records

In Brief: Blue Note is arguably the definitive jazz label, having championed the style from day one and rarely straying from it over the next 80 years, even while enduring the inevitable mergers and acquisitions experienced by most record companies, thus proudly standing by their slogan: “The Finest in Jazz Since 1939.”

The History: Alfred Lion was a German Jewish immigrant, newly returned to New York City (after a first, ill-fated stay) in 1938, when he witnessed one of the historic From Spiritual to Swing concerts organized by Columbia A&R man John Hammond at Carnegie Hall, and was inspired to found Blue Note with partner and investor Max Margulis, a writer, musician, music teacher, and left-wing activist.

Naming their label after the so-called “blue note” common to both jazz and blues (a note intentionally played slightly off standard pitch to convey different emotions), the duo began recording the era’s popular swing, hot jazz, blues and boogie woogie, often renting off-hours studio time to capture artists like Albert Ammons, Meade ‘Lux’ Lewis, Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines, James P. Johnson, and Sidney Bechet (whose 1939 version of “Summertime” was Blue Note’s first hit) after their night’s work in the city’s clubs.

As jazz started evolving at an accelerated pace in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, Blue Note embraced the rising crop of bebop and hard bop artists, including Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey, Bud Powell, James Moody, Horace Silver, Hank Mobley, Howard McGhee, and Miles Davis, with legendary producer Rudy Van Gelder generally overseeing their sessions, and photographers Francis Wolff and Reid Miles (who also acted as graphic designer) providing a distinctive, unified aesthetic that’s still revered today.

All these ingredients can be found in John Coltrane’s sole Blue Note release, 1957’s landmark Blue Train, and the label continued to invest in innovative styles like modal and free jazz into the 1960s; a philosophy, which, along with their artist-friendly fees, attracted a whole new generation of groundbreaking artists such as Lee Morgan, Jimmy Smith, Jackie McLean, Freddie Hubbard, Dexter Gordon, Cecil Taylor, Bobby Hutcherson, McCoy Tyner, and Ornette Coleman.

However, as jazz’s popularity and cultural influence gradually declined in the latter half of the ‘60s, so too did Blue Note’s – not helped by a succession of leadership changes (Lion, Wolff and Miles all retired or left around this time) and the label’s 1966 merger with Liberty Records, then United Artists a decade later, although top executive George Butler oversaw a brief period of jazz/pop crossover success in the early ‘70s via artists like Donald Byrd, Ronnie Laws, Bobbi Humphrey, and Earl Klugh.

Sold once again in 1979, this time to EMI, Blue Note was effectively shuttered until 1985, when it was relaunched under Capitol subsidiary Manhattan Records, then decoupled from Manhattan in 1989 to encompass all of EMI’s jazz roster (now including John Scofield, Jason Moran, Wynton Marsalis, etc.) and, after Norah Jones’ blockbuster success in 2002, expanded into the Blue Note Label Group in 2006, overseeing an eclectic range of jazz and non-jazz adult artists like Al Green, Anita Baker, and Van Morrison.

And in 2012, Blue Note, as well as all of EMI, was purchased by Universal Music Group, artist/producer Don Was was installed as president, and the label continued to diversify its roster, both in and out of jazz, with artists like Gregory Porter, Kandace Springs, Gogo Penguin, and Robert Glasper, while upholding its rich legacy with an aggressive reissue program for its timeless jazz catalogue, some of which has also resurfaced by way of widespread sampling by rap and hip hop artists.

The Labels: From the very beginning, in 1939, Blue Note labels utilized the L-shaped layout and bold, simple fonts that would become the company’s trademark, but color schemes varied (red and black, yellow and blue) until the classic white and blue combination took hold in the 1940s.

Except for the occasional change of address and other copy (e.g. from “microgroove” to “stereo”) this design would remain faithfully untampered with for the next three decades (though singles sometimes sported evenly split blue/white or royal blue labels), until Blue Note’s merger with Liberty yielded a short-lived reissue series identified by a black label featuring a slim, baby-blue trim to the left.

The 1970s introduced a sequence of solid blue labels topped with a new logo composed of a small music note inside a large lower-case “b,” but this look too was eventually abandoned for a return to Blue Note’s revered, L-shaped white and blue scheme.

Note: ‘What’s in a Label’ is a Discogs Blog series devoted to celebrating both the history and art of record labels.

#blue note#record label#jazz#blues#emi#manhattan#liberty#robert glasper#john coltrane#miles davis#james p johnson#bud powell#freddie hubbard#wynton marsalis#gogo penguin#kandaze springs#gregory prter#don was#capitol#al green#anita baker#van morrison#norah jones#john scofield#jason moran#earl klugh#bobbi humphrey#ronnie laws#donald byrd#ornette coleman

0 notes

Photo

Vertigo Records

In Brief: Vertigo was one of several major label subsidiaries launched in the late ‘60s to nurture progressive rock talent, quickly developing a unique roster and brand aesthetic that are still respected, even revered, by modern-day music collectors.

The History: Founded in 1969, out of the London offices of Philips/Phonogram (later part of the Universal Music Group), Vertigo’s tacit mission under top executive and visionary Olav Wyper was to compete with EMI’s Harvest and Decca’s Deram subsidiaries in mining rock’s fertile fields for progressive sounds.

Before we go any further, we should clarify that while “progressive rock” is now associated almost exclusively with a specific kind of group, such as King Crimson, Genesis and Yes, the term had a far more wide-ranging scope at the turn of the ‘60s and ‘70s, after The Beatles had proven that rock need have no limitations, beyond what artists could imagine.

This is why Vertigo’s earliest releases range from the jazz-rock fusions of Patto and Colosseum, to the classically-steeped art rock of Gracious and Cressida, to the avant-folk experiments of Dr. Strangely Strange (featuring a young Gary Moore), to the non-traditional blues-rock of May Blitz and Juicy Lucy, to the protean heavy metal of Uriah Heep and Black Sabbath.

These bold signings didn’t always generate huge sales, but they gave Vertigo instant credibility, which, in tandem with the label’s innovative packaging ideas and state-of-the-art production values, attracted scores of new artists to a roster that would grow increasingly eclectic as the ‘70s wore on, adding Kraftwerk, Magma, Gentle Giant, Lucifer’s Friend, Status Quo, Thin Lizzy and Dire Straits, among others.

However, since the bulk of Vertigo’s catalog was licensed for release by other labels outside the U.K. there’s always been some confusion among fans as to why their U.S.-purchased pressings of Vertigo artists sported Mercury, A&M, Island and Warner Bros. labels, to name just a few, while the same was true in the opposite direction, as Vertigo became the European distributor for Mercury (Rush, Kiss, Def Leppard, Bon Jovi, ABC) and the WEA system (Genesis, Dio, Metallica).

And as the ‘80s and ‘90s progressed, this arrangement conspired with the music industry’s never-ending corporate mergers and management upheavals to weaken Vertigo’s once unmistakable identity, gradually downgrading it from a proper standalone label to just another convenient imprint that its parent companies can periodically assign to assorted artists or executives.

That being said, Vertigo’s historical cachet sometimes still comes in useful in the new millennium, whether for launching hip new artists like The Rapture, The Killers and Razorlight, or celebrating legacy artists like Black Sabbath, on the occasion of their 2013 release, 13.

The Labels: The original, black and white “Vertigo Swirl” – designed to “draw you into the record” like an optical illusion, according to label founder Wyper – is easily one of history’s most iconic and collectible labels, not least because it adorned less than 100 full-length titles between 1969 and ’73.

Vertigo’s singles also got their own swirl, and all formats displayed track-listing on the B-sides’ comparatively plain white label, although Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality uniquely merited a made-to-order black label.

But all good things must come to an end, so, by the mid ‘70s, the swirl had been replaced by an equally popular, imagination-fueling “Spaceship Acid Trip” painted by progressive rock’s favorite artist Roger Dean, which was deployed in a variety of in blues and greens throughout the ‘70s, plus very rare alternate shades in specific European markets.

Both of these beloved archetypes make it impossible to say kind things about Vertigo’s next branding overhaul for the 1980s, whereupon they adopted a bland, conservative typeface over an orange-yellow backdrop, later replaced by custom vanity labels for their artists, topped by a simple encircled “V” logo.

Note: ‘What’s in a Label’ is a Discogs Blog series devoted to celebrating both the history and art of record labels.

#Vertigo Records#Roger Dean#progressive rock#classic rock#heavy metal#king crimson#geneis#yes#the beatles#thin lizzy#uriah heep#lucifer's friend#patto#colosseum#gracious#cress#juicy lucy#dire straits#status quo#kraftwerk#gary moore#gentle giant#magia record#rush#kiss#bon jovi#def leppard dio#big country#mark knopfler#the killers

0 notes

Photo

Chiswick Records

In Brief: Chiswick Records was the paradigm of a British indie label in the 1970s, as much for reissuing rare and influential out-of-print records and for discovering several future instigators of the punk rock revolution.

The History: Irishman Ted Carroll, previously a co-manager for Thin Lizzy, and his partner Roger Armstrong ran second-hand record stalls on the streets of London until 1975, when they opened a store called Rock On (allegedly the inspiration for author Nick Horsnby’s High Fidelity) near the Camden Town tube station.

An instant hit with discerning urban music lovers, Rock On quickly expanded and Carroll, Armstrong, and store clerk Trevor Churchill soon took things one step further by founding Chiswick Records with the twin goals of signing new talent and reissuing vintage recordings that were in high demand at the store.

Through to the end of the ‘70s, Chiswick would build an eclectic roster of artists, both bound for obscurity and history, including The Count Bishops, The Damned, Dr. Feelgood, Johnny Moped, Skrewdriver, Riff Raff (featuring a young Billy Bragg), Joe Strummer’s pre-punk pub rock outfit The 101’ers, and speed metal legends Motörhead, whose Lemmy Kilmister had been a Rock On regular.

A licensing liaison with giant EMI brought additional financial resources from 1978 to 1981, by which time Chiswick’s three principals wanted to focus on their reissue imprint, Ace Records (still around today), and left their old brand in EMI’s hands, to exploit and revive for sporadic catalog reissues.

The Labels: Taking its name quite literally, Chiswick’s label contained a detailed, half-moon map of the West London district from which it borrowed its name, topped by a custom logo in a cursive font, also found on the company’s silver-label 45s.

This map remained the most prevalent design throughout Chiswick’s relatively brief history, but the late ‘70s introduced a memorable depiction of a stylus (seemingly caught in the act of dropping on the turntable), and the early ‘80s brought a solid crimson label boasting a new, ‘slacks-and-dress-shoes’ box logo in the top right corner.

After Chiswick’s transition from frontline to catalog imprint in 1982 and beyond, a sequence of rather dull gray labels typically outfitted ensuing reissues, with the occasional two-tone red/gray designs for some added variety.

#Chiswick Records#punk rock#pub rock#joe strummer#billy bragg#johnny moped#dr. feelgood#skrewdriver#motorhead#lemmy kilmister#the damned#thin lizzy#ted carroll#ace records#the clash#speed metal#rock on#high fidelity#nick hornsby

0 notes

Photo

Atlantic Records

In Brief : Atlantic rose to prominence as perhaps the ultimate independent record label prototype, but it was also among the few indies to survive the leap to major label, becoming one of history’s most successful ones, at that.

The History: Atlantic Records was founded in October, 1947 by Ahmet Ertegun, a Turkish-born diplomat’s son, with a $10,000 loan from the family dentist, alongside Herb Abramson (himself a dentistry student, albeit one with prior, part-time experience at the National and Jubilee labels) and his wife Miriam.

They would remain the company’s only employees for the next two years, as Ertegun and Abramson scouted untapped talent from New York City’s nightclubs to flesh out Atlantic’s fledgling roster, focusing on their twin passions, jazz and R&B, while also dabbling in country, children’s music, and even spoken word recordings to keep the lights on.

Finally, in February of ’49, Atlantic scored its first bona fide hit with Henry ‘Stick’ McGhee’s “Drinking Wine, Spo-Dee-O-Dee,” paving the way for a flurry of signings and more consistent sales from the likes of Ruth Brown, Big Joe Turner, Dizzy Gillespie, Erroll Garner, LaVern Baker, The Clovers, Sonny Terry, Professor Longhair, and the label’s next gamechanger, Ray Charles.

Brother Ray’s groundbreaking fusion of rhythm & blues with gospel brought soul music to the masses, and his subsequent explorations of everything from big band jazz to country throughout the 1950s would earn him fame as the “genius,” even as Atlantic’s team behind the scenes grew to include several future music industry legends.

First came producer and engineer Tom Dowd, a veteran of the Manhattan Project who pioneered numerous recording techniques and the first multitrack studio technology, going on to capture an incalculable number of classic albums and singles by John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, The Coasters, Eric Clapton, and the Allman Brothers Band, among others.

Then came Jerry Wexler, a former Billboard reporter, credited with coining the term “rhythm & blues” to replace the insensitive “race records” designation, whose ears for identifying and developing new talent would, over the next two decades, be as crucial as Ertegun’s to Atlantic’s success, via his work with Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Cream, Led Zeppelin, and other icons.

Ahmet’s brother Nesuhi also joined the fold in 1955 to oversee Atlantic’s jazz division and the label later benefitted from astute partnerships with rising stars like rock & roll songwriters Leiber & Stoller, wunderkind producer Phil Spector, and, perhaps Wexler’s greatest coup, a timely promotion and distribution deal with Memphis-based Stax Records.

Stax’s incredible stable of artists, including Booker T. & the M.G.’s, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Albert King, Sam & Dave, Isaac Hayes and Otis Redding, would bolster Atlantic’s sales throughout the 1960s and, along with in-house signings like Pickett, Solomon Burke and, of course, the Queen of Soul, Aretha, set the stage for the company’s sale to Warner Bros.-Seven Arts in 1967.

But Atlantic would retain control over its own roster after the sale, and they kept their hitting streak going with artists like Cream (later assigned to the Atco imprint), Dusty Springfield, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Boz Scaggs, Roberta Flack and Led Zeppelin, pointing the way forward to ever-greater genre diversity in the 70s, and gradually marginalizing Wexler.

Ertegun, meanwhile, remained virtually untouchable in the art of courting new artists and, with help from key new executives like Jerry Greenberg and John Kalodner, Atlantic powered through the decade behind platinum-selling signings like ABBA, Bette Midler, Yes, Genesis, King Crimson, Chic, AC/DC, Foreigner, etc., while partnering to launch Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song imprint and The Rolling Stones’ vanity label.

In the ‘80s, Atlantic continued to prosper behind Ertegun and new president Doug Morris (until 1995), scoring multi-platinum sellers with Phil Collins, Debbie Gibson, INXS, Twisted Sister and Skid Row, followed, in the ‘90s, by the likes of Rush, Stone Temple Pilots, Tori Amos and Hootie & the Blowfish, and, in the third millennium, by Coldplay, Kid Rock, Matchbox 20, Jill Scott, Bruno Mars, Ed Sheeran, Gnarls Barkley, James Blunt and The Darkness, and many more — always under some version of the WEA/Time-Warner corporate umbrella.

And, though Atlantic’s modern business bears little resemblance to its indie label golden eras of the ‘50s and ‘60s, its legacy is secure, even surviving chairman emeritus Ahmet Ertegun’s passing in 2006 (spontaneously reuniting the surviving members of Led Zeppelin to pay tribute), after nearly 50 years with the company.

The Labels: Like most major record companies, Atlantic has used a vast assortment of logos, label colors and designs during its decades-long history, beginning with a stylized capital “A” underlining the remaining letters with its crossbar, framed in black against red, yellow, and other background hues.

An alternate, less aggressive logo and label adorned Atlantic’s first long-playing records of the 1950s in black, gray, green, gold and yellow tones, but the first significant design change came at the end of the decade with the addition of a trademarked “Fan Logo” surrounded by a white circle and borders matching pink and orange, green and blue.

In the ‘60s, Atlantic’s labels adopted perhaps their most celebrated look: two shades separated by a thick, horizontal white line containing the capital “A” plus fan logo, of which the most iconic combination was probably the “green and red” (or orange, depending on one’s level of color-blindness), made famous by multi-platinum ‘70s releases from Zeppelin, Yes, Chic, Bette Midler, Alice Cooper, Foreigner and AC/DC.

The ‘80s brought a combination of both retro designs and custom labels for jazz and “Atlantic Group” releases (see also the short-lived, late ‘70s disco label), after which the CD era came and all bets were off, yet the signature imagery made legendary by Atlantic remains imminently recognizable to any self-respecting collector.

Note: ‘What’s in a Label’ is a Discogs Blog series devoted to celebrating both the history and art of record labels.

#Atlantic Records#led zeppelin#AC/DC#Yes#Hall & Oates#King Crimson#Alice Cooper#ABBA#INXS#Ratt#crosby stills and nash#Roberta Flack#Skid Row#Dusty Springfield#swan song#stax#john coltrane#sidney bechet#chic#bette middler#foreigner#cream#coldplay#matchbox 20#james blunt#wea#ahmet ertegun#jerry wexler#john kalodner#the darkness

0 notes

Photo

Columbia Records

In Brief: Columbia was one of the very first record labels (and the greatest … if you ask its very biased employees), so its long history is also pretty much the history of the recording industry.

The History: The world’s oldest surviving record label, Columbia was founded in 1889 by Edward D. Easton, a stenographer by trade, in the District of Columbia, which gave the company its name.

In its infancy, Columbia had an exclusive contract for selling and servicing Thomas Edison’s namesake brand of phonographs and music cylinders, but by 1901 they had adopted rival RCA Victor’s patented “Disc Records” and, by 1908, introduced their own so-called “Double-Faced” 10-inch discs.

During the first quarter of the 20th Century, Columbia (now based in New York) generated most of its sales from opera stars associated with New York’s Metropolitan Opera, but the company didn’t hesitate to record most every available musical genre: from homegrown American styles like jazz, blues, country and folk, to ethnic and foreign traditions, the better to supply its fast-growing overseas operations.

By the time America’s recording industry was rocked by the crippling effects of the Great Depression and the advent of free radio transmissions (shrinking to 1/10th its prior revenues between 1929 and ‘31), Columbia had weathered numerous ups and downs, separated from their U.K. division (which became EMI), and had been sold for a pittance to the American Record Corporation (ARC), virtually ceasing operations, in the process.

But the fortuitous hiring of legendary A&R scout John Hammond and a new focus on “secondary” genres like southern gospel, country, blues and jazz, including discoveries like Benny Goodman, Bessie Smith, Charlie Christian, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Charles Davis Tillman and the Chuck Wagon Gang, kept Columbia afloat long enough to turn its fortunes around.

This turnaround started in earnest with Columbia’s 1938 purchase by William S. Paley, of CBS (ironically, the same Columbia Broadcasting System the record company had founded in 1927, and later spun off), gained momentum in the next decade with the success of young New Jersey crooner named Frank Sinatra, and culminated in a major technological breakthrough in 1948 via Columbia’s development of the 12-inch, 33 1/3 RPM long-playing album, as we still know it today.

Under the leadership of Paley and new company president Goddard Lieberson, Columbia firmly reclaimed their major label status in the 1950s, leveraging the new LP format to boost classical music sales, to introduce mega-selling Broadway cast recordings (masterminded by Lieberson), and to score huge success with bandleader and A&R man Mitch Miller’s Sing Along with Mitch series, while beefing up their roster of easy listening stars (Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Doris Day), jazz innovators (Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Dave Brubeck), and signing an Arkansas-born country singer named Johnny Cash.

The ‘60s brought a slew of folk giants in Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Simon & Garfunkel, The Byrds, and arguably Hammond’s greatest discovery, Bob Dylan, plus a new mainstream star in Barbra Streisand; yet Columbia, swayed by Miller’s strong objections, stubbornly missed the boat on rock & roll until decade’s end, when new president Clive Davis dragged the label into the future with landmark signings like Janis Joplin, Chicago, and Santana.

Columbia rarely slept on another cutting-edge musical style again, nor did they relinquish their standing amongst the world’s most powerful majors, roaring through the ‘70s, first under Davis and then his successor Walter Yetnikoff, behind superstars like Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Pink Floyd, Aerosmith, Judas Priest, Willie Nelson and Earth, Wind & Fire, and into the ‘80s with Journey, Men at Work, The Bangles, L.L. Cool J, and countless others, paving the way for the company’s sale to the Sony Music in 1988.

Today, Columbia still operates under the Sony Music umbrella and remains one of the music industry’s perennial sales leaders, while navigating a succession of executives (Tommy Mottola, Rick Rubin, Rob Stringer, Ron Perry) and consistently launching new stars (Alice in Chains, Mariah Carey, Celine Dion, Ricky Martin, the Dixie Chicks, Beyoncé, John Mayer, Harry Styles and Lil Nas X, etc.), very much the definition of a major label, well over a century since its modest beginnings.

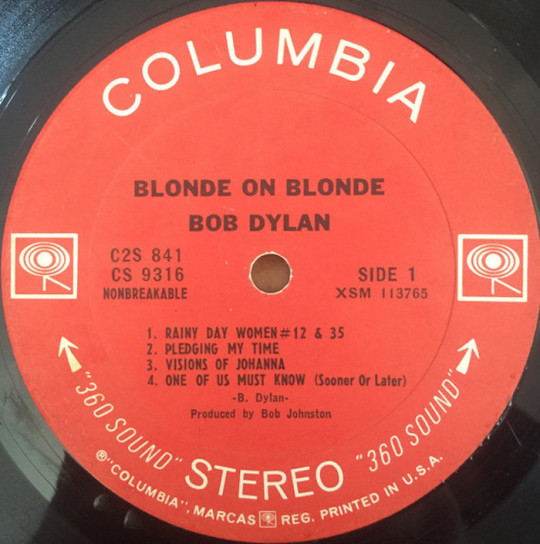

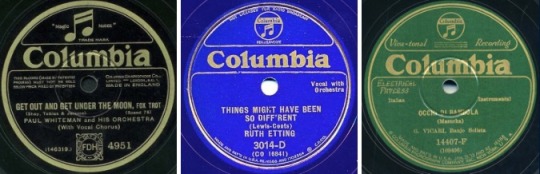

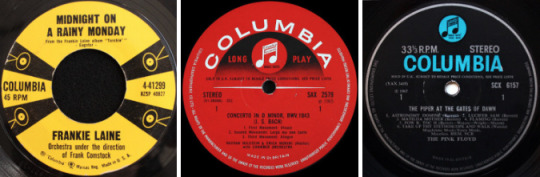

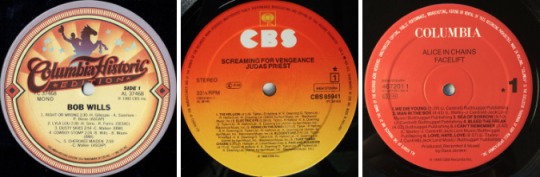

The Labels: A record company doesn’t stay in business for one hundred years-plus without making a few cosmetic changes to its brand, logo, and labels, yet Columbia’s core design hallmarks haven’t changed very much, all things considered.

With only a few exceptions, Columbia labels have stuck with a single color as background for their bold typefaces, starting with the vintage gold-on-black designs of the early 20th Century, before adding a variety of colors based on music genre: red for pop, green for jazz, gray for classical, orange for country, pink for sacred music, etc.

For a brief time in the 1930s, Columbia issued the now highly collectible “Royal Blue Records” (yes, both the label AND vinyl were blue), before cycling through a sequence of clean, classic, red designs in ensuing decades – all of them familiar to most consumers in possession of timeless LPs recorded by Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, etc., etc.

Among Columbia’s rare design deviations over the years there have been the gray counterparts to these red labels employed for the Masterworks product line, a short-lived bright yellow 7-inch look used in the ‘50s, an uncharacteristically elaborate (read: corny) jazz and country reissue series of the ‘70s and ‘80s, and a memorable sunset design adopted in the ‘70s and ‘80s for singles in America and albums overseas, often substituting the logo of parent company CBS.

As for distinguishing trademarks, Columbia has also used them sparingly ...

First came the so-called “Magic Notes” gracing most Columbia labels into the 1940s (and occasionally, beyond), then the iconic, stylized, modernist microphone (a.k.a. the “Walking Eye”) that had previously served as the CBS logo outside North America, and was quietly dropped after the company’s sale to Sony Music.

Note: ‘What’s in a Label’ is a Discogs Blog series devoted to celebrating both the history and art of record labels.

#whatsinalabel#discogs#columbia#columbia records#miles davis#frank sinatra#thelonious monk#bob dylan#bruce springsteen#johnny cash#willie nelson#billy joel#pink floyd#alice in chains#mariah carey#celine dion#ricky martin#dixie chics#lil nas x#beyonce#john mayer#harry styles#jazz#rock#blues#country#pop#easy listening#soul#R&B

1 note

·

View note