Text

Concluding Post: Down the Memory Lane

Do you have to apologize for events that you did not cause?

Can you claim you knew what happened?

Can you talk on behalf of those who have deceased?

How do you remember? Or, would you rather forget?

Whose Narratives Matter?

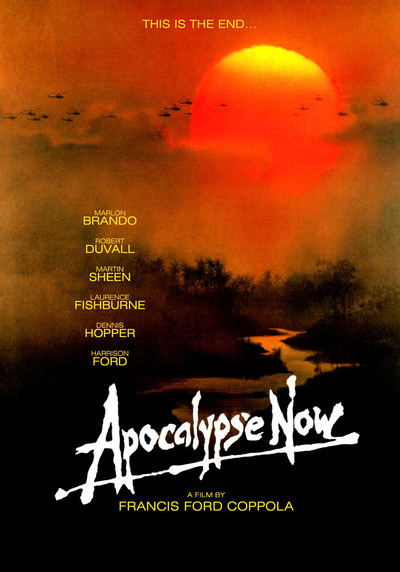

Writing this post is difficult. Eight posts into Apocalypse Now, I still cannot claim what stories we should tell. The premise of this blog has been to uncover the voices that were missing – those of the Vietnamese in Apocalypse Now or of the natives in Heart of Darkness, the novel on which the movie was loosely based. As I wrote in the comparison posts of the two mediums (here and here), I could find very little narrative coming from the natives. Granted that as a movie, Apocalypse Now has limited space to feature several plot lines, when compared to slightly more freedom for sideway descriptions in the case of the book. Even in Heart of Darkness, however, there were not many scenes when the natives did more than crawling or babbling. The Vietnamese has an even more limited role in Apocalypse Now. The story rests in Captain Willard’s silent struggle with post-traumatic disorder, in the sight of napalm swallowing trees and people, in Lance‘s firing frantically into a fishing boat, and in Kurtz’s recall of the ruthlessness of the Viet Cong. We never learned about what the Vietnamese might have thought, as they watched their loved ones and belongings burn down. Without the other side, the narrative seems incomplete to me.

The truth is, I might not be the intended audience of Apocalypse Now when it came out in 1979. As I noted in my earlier post, this was when the Right was trying to retell the story of how Americans did not loose. That Americans were simply not brutal enough, or that Americans sided with the “softer” side, the Southern Vietnamese. If Apocalypse Now was intended for Americans, its narratives might have been complete. I realized this more than ever in my conversations with my friend, someone who only learned about the war in a chapter in his history textbook, and his grandfather, who served in the Air Force right after World War II. To my friend, the war in Apocalypse Now was the backdrop to feature dehumanization and what came out of it. As such, the movie could have been about any war, and its message would still have stayed the same. To his grandfather, the war was a justified cause. When I asked his grandfather his opinion about the war, he said he did not have one. “If the government thinks it is right to go to war, we go to war.” Someone in the room reminded him that Americans lost 58,000 men, but two millions Vietnamese from the North and South lost their lives, and as many as 400,000 boat people died at sea when they tried to migrate. He did not respond.

If we base our stories and interpretations on our prior experiences, none of our reading of the movie is wrong. This is a topic we discussed at length in class – how narratives target certain audience and build on experiences. My friend’s grandfather, as a member of the Great Generations, is proud of America and its exceptionalism. My friend is as curious to learn about the war as I am, to see what we could have done differently. I cannot claim that my interpretation is better than theirs, because I also did not really experience what happened.

However, narratives do not bound us to rigid beliefs; they could open up the opportunities to question the untold stories. “A story happens when someone walks out of town and someone else walks into town”. It is from questioning what triggered the action that a new narrative emerges. Reducing the story to “a war narrative” in subsequent productions in other genres—including a fantasy series and a Sci-Fi—eliminates the opportunities to dig deeper into the Apocalypse Now storyworld beyond its surface-level messages. It is in this aspect that I consider the storyworld project a success, because as much as it prompted me to explore my own assumptions as a Vietnamese, it also caused me to interact with the other narratives, even when they were uncomfortable.

You learn about the other narratives not to become apologetic or accusatory. Rather, you acknowledge these stories to not repeat the same regrets.

What Was Left Behind? – The Narratives that Transcend

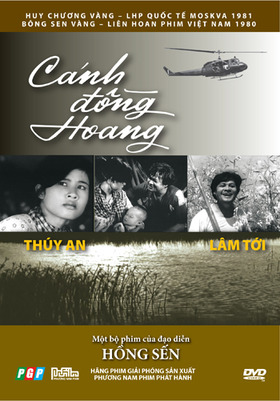

What is in the Vietnamese movies from the same period with Apocalypse Now? There is The Abandoned Field: Free Fire Zone (1979), a film by the North Vietnam. The film shares a surprisingly similar setting with Apocalypse Now, featuring the life under helicopter bombs in the Mekong Delta. The landscape, albeit mostly taking place within the scope of the abandoned field, reaches from under the water to the sky edges as American helicopters were firing. The film focuses on the day-to-day interaction in a family of three: husband, wife, and their child in a small shack in the middle of the water. The film is not free from bias. The American troops, if seen, are most often drunk and shooting at random. When a helicopter shoots the husband, however, the wife revenges by shooting the helicopter down. The most notable scene is when the film with a photograph falling from the shot pilot’s chest. In the photo are his wife and child. Yes – the pilot is an American. Yes – he just killed a Vietnamese and got killed. But he is also a human pulled into war.

Helicopters in the sky, water meadow underneath, does that seem familiar? (Picture: Poster of The Abandoned Field)

I cannot claim to have uncovered the hidden voices if I only mentioned films by the North Vietnam. Regrettably, since most of the movies by the South Vietnam were banned from screening, I did not know of any growing up. One movie that I know of from the 1970s is an anti-war film named The Land of Sorrows (1973). The movie features a family who could not flee the war in Central Vietnam during the Tet Offensive of 1968. There was internal conflict, as members in the family—an anti-war son, a captain on the South Vietnam side, a sister about to marry someone who is neutral in the war, and another brother who has just been drafted—walk the line between patriotic and familial values. Mixed in with the main narrative are real footages of people fleeing from the battle, including scenes of dead civilians and children. Rather than fighting back, the middle son, a singer who opposed the war, sang amidst armored cars:

When peace returns to our country

I shall visit many sad cemeteries

And tombs covered with grass

When killing ends in our country

Then children will sing on the roads

When peace returns to our country

I shall be continuously on the road

From Saigon to the centre

From Hanoi towards the south

I shall share everyone’s happiness

And I hope to forget the history of my country

Taking on the antiwar lens, The Land of Sorrows is a far cry from the rather propagandistic The Abandoned Field. In fact, I would not have heard about The Land of Sorrows had it not been for this project, because the movie was banned from screening in Vietnam. When we zoom in on the civilian losses in the two movies, however, their sufferings are not that different no matter which sides of the war they were on. These are the lives that Apocalypse Now does not include.

What to Remember?

Recall Captain Willard’s voice recollection in Apocalypse Now’s opening:

It was no accident that I got to be the caretaker of Colonel Walter E. Kurtz’s memory, any more than being back in Sai Gon was an accident. There is no way to tell his story without telling my own. And if his story is really a confession, then so is mine. (Apocalypse Now, 00:09:47)

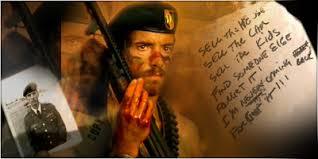

Just as Willard carries onward Kurtz’s memories to remind himself of his own version of Vietnam, no war story should stand alone. This project has been an opportunity to connect the themes of Apocalypse Now with the narratives about the Vietnam War in other works, from a Southern Vietnamese movie to a documentary (Ken Burns’ Vietnam War, which I wrote about earlier). In the beginning of the documentary Vietnam War, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger suggested that America needed to “heal the wounds and put Vietnam behind us.” Similarly, what happened in the war, as seen in Apocalypse Now, were only chapters along a river in an unknown land that Willard might have left behind. That is not an option for reconciliation. At the end of the day, there were losses on both sides. I saw my dad tear up when he talked about his emotions upon watching the Vietnam War documentary series and Apocalypse Now. He talked about the soldiers from his platoon who could not make it for the first time, something we never did when I was at home. Only when you approach “the wounds” with respect and openness to the untold stories can you really heal.

I will leave you with these questions.

Do you have to apologize for events that you did not cause?

Can you claim you knew what happened?

Can you talk on behalf of those who have deceased?

How do you remember? Or, would you rather forget?

References:

Rosenburg, Alyssa. What Ken Burns Wants You to Remember. The Washington Post, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/act-four/wp/2017/09/29/the-american-war-youve-watched-all-18-hours-of-the-vietnam-war-heres-what-ken-burns-wants-you-to-remember/?utm_term=.e4b27e4cd66b

Spector. The Vietnam War. Encyclopedia Britanica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War

Trueman. "Vietnamese Boat People". The History Learning Site, 2015. http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/vietnam-war/vietnamese-boat-people/

Notes:

(1) Thank you, Jason, for suggesting me to include the Vietnamese films and compare the narratives. If you are curious, you can watch the two movies here, The Land of Sorrows and The Abandoned Field: Free Fire Zone.

(2) Eighteen hours into the other narratives — the 10 episodes of The Vietnam War, by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick can be watched here.

(3) In the beginning of the class, I mentioned looking at the physical remnants of Apocalypse Now based on the documentary about the making of the film. What I meant by physical remnants was the legacy of the places where the film took place. For example, the residents of Baler, the fishing village in Northern Philippines where the movie was actually filmed, took up surfing because of the surfing scene in the movie. Or how the filmmakers started widespread child prostitution in the villages they came to, years after they left. While those are also interesting hidden narratives, if I were to write this blog again, I would still stick to the war narrative, particularly the natives’ voices, as it allows me to bring the film close to home.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reimagining the War (Post 8)

In post four, five, and six, I have discussed American imperialism and the contrast between the American masculinity and the natives’ squalor — shapeless and degenerated individuals. The invisibility of the Vietnamese is not limited to Apocalypse Now; it is representative of the Vietnam War movies in this period 1977-1987 (Williams 216). This post juxtaposes the American masculinity in the movies released only between 1975 and 1980, and the historical view of the war, as revealed by snippets of the documentary series Vietnam War by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

The messages of the past

In the short timeframe before the release of Apocalypse Now (1979), there were uncompromising anti-war features — Just a Little Inconvenience (1977), Coming Home (1978), or Go Tell the Spartans (1978), as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of the veterans in Taxi Driver (1976).

There was also the notion that the Americans would survive. Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), for example, examined second-generation Americans in the Viet Cong’s captives. Whereas one was destroyed by his brutal experiences, the other came out stronger. The Deer Hunter conveys the message that even though the war was wasteful, it is only a transient moment in America’s history. America would become stronger (Parrish). The message that America will reemerge from the darkness, just like Captain Willard, is also evident in Apocalypse Now. Moreover, in Apocalypse Now, Kurtz reiteratively emphasized that the Americans lost the war because they were not as ruthless as the Viet Cong. Contrary to the previous features about the war, both The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now were more defensive about the war. They represented a change in the political atmosphere, as the Right Wing rewrote Vietnam, “not as a war America lost, but one it was prevented from winning” (Buzzanco 3). America lost, because Americans and its allies, the Southern Vietnamese, were not as brutal as the Northern Vietnamese.

The messages of the present

The narratives in the movies—the reimagined notion of patriotism—persists to this day. Through collecting the voices from all sides — the Americans, the Northern Vietnamese, and the Southern Vietnamese, the documentary series Vietnam War portrayed how all sides perceived and are perceiving the war. In many narratives that the documentary featured, the war was portrayed as a civil war between the North and the South — a war that justified whichever side the Americans took. Patriotism is those who spoke out and took action against the war. Patriotism was also the soldiers who fought, whether they agreed with the war or not. Ken Burns, the documentary's director, pointed out that “sometimes it is the sum total of the heroic contributions of individual people in many different spheres that make it.” (Rosenberg).

Running against the backdrop of political conversations in the U.S., the voices of the other side were once again submerged. The question has become who is stronger — the Americans who fought or those who did not. In the 2004 election, John Kerry was attacked for his service in the war. In 2016, Trump mocked his opponents for having been captured in the war. Some tried to justify Americans’ position by using the message in Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter — that America emerged stronger. For example, the Vietnam War documentary features the voice of Tommy Vallely, someone who served with the Marines in Vietnam and has worked for the past 30 years to improve the relation between the Americans and the Vietnamese. In Vallely’s words:

I think the Vietnam War made us stronger, not weaker. Vietnam basically wakes up America and says: Look, you have to rethink how you operate in the modern world. I don’t know what it was worth, but I think the Vietnam War strengthens the U.S.

Throughout all these justifications, the Vietnamese voices were still missing. Is the war, like any others, another glance at what America was and is, without much thought of what it has left behind?

References:

Buzzanco, Robert. Masters of War: Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 3.

Parris, Michael. The American Film Industry and Vietnam. History Today, 1987, http://www.historytoday.com/michael-paris/american-film-industry-vietnam

Rosenburg, Alyssa. What Ken Burns Wants You to Remember. The Washington Post, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/act-four/wp/2017/09/29/the-american-war-youve-watched-all-18-hours-of-the-vietnam-war-heres-what-ken-burns-wants-you-to-remember/?utm_term=.e4b27e4cd66b

Williams, Paul. What A Bummer for the Gooks’: representations of white American masculinity and the Vietnamese in the Vietnam War film genre 1977–87. European Journal of American Culture, 2013, pp. 215-234

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I was going to the worst place in the world and I didn’t even know it yet.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Legacy of Apocalypse Now (Post 7)

The lines and scenes from the movie that stay for decades. Rather than separate characters or the symbol of a single war, “Apocalypse Now” has framed an approach to war as dehumanizing and horrifying. The two works that I discussed below, one a fantasy TV series, and one an Action/ Science fiction/ Fantasy/ Monster movie, only used the suggestion of war - the classic helicopter scene from “Apocalypse Now”, as the setting for their narratives.

I love the smell of napalm in the morning

What is the similarity between helicopters dropping napalm on a village in “Apocalypse Now” and dragons swooping down to attack soldiers in “Game of Thrones”? The answer is their approach to horror - death from above, terror on the ground. More than the filming technique, the running theme of Apocalypse Now, the horror of soldiers watching men die around them and realizing that war was much more than what they had imagined.

The helicopter attack scene from “Apocalypse Now”

The dragon and Dothraki battle, Game of Thrones, Season 7, Episode 4: “The Spoils of War”

The critique of war

The most recent work that was inspired by Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” is “Kong: Skull Island”, from its setting and color scheme to plot line.

The powerful helicopters that caused so much damage in “Apocalypse Now” were defenseless in an unknown land. (Picture Credit: Warner Bros)

When looking at the two movies:

Setting: Vietnam War, early 1970s

Overarching plot line: The struggle of people who have seen unimaginable things in conflict - moral and immoral, life and death, disillusion and illusion. “Kong: Skull Island”, however, was not a movie about war. It used a metaphor of war critique as the backdrop for an action movie. In fact, the movie spanned from World War II to the Vietnam War, implying that the wars and the human beings in them were fighting for the same causes. Our class discussion about genre and targeted audience came back to mind. A majority of the viewers of “Kong” might not have been to the war. They are paying to see a monster in an exotic place, not for a real war.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Role of the Natives (Post 6)

Black shapes crouched, lay, sat between the trees, leaning against the trunks, clinging to the earth in all attitudes of pain, abandonment, and despair. They were nothing earthly now, nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation. One of these creatures rose to his hands and knees and went off on all fours towards the river to drink. (Conrad, 1899, p. 17).

The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us, who could tell? (Conrad, 1899, p. 35)

(Exploring the role of the natives in Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now)

Unearthly and animal-like creatures. Incomprehensible speech. Through the eyes of Marlow, the natives in Heart of Darkness are just shapes, not individuals with features to distinguish one from another. They did not even walked in a civilized way like the Europeans. Instead, they crawled "on all four". What those natives said, therefore, was not worth paying attention to, for it was nothing more than an “outbreak in a mad house” (Conrad, 1899, p. 35)

Arguably, the Vietnamese in Apocalypse Now were portrayed in the same manner. They often appeared as faceless horde in the background, looking fearful and alert. Most of the times, they were dead or were going to be. Almost nothing they spoke was translated into English, as it was unfathomable and trivial to the Americans. The only Vietnamese speaking part came from a south Vietnamese army translator, “This man is dirty VC! He wants water! He can drink paddy water!” This line bears a strong resemblance to the image of the natives in Heart of Darkness, crawling to the river to drink from it, as opposed to the civilized who drank from their bottles.

Like the natives, their land, Africa in Heart of Darkness and Vietnam in Apocalypse Now consisted of only indistinguishable shapes — jungle, marshland, and mud. Humanity is absent throughout. Even in 1970s, Apocalypse Now left out the ubiquity of Vietnamese signs and banners — sign of civilization. In such settings, the Vietnamese were even less than animals. In an encounter with a Vietnamese family halfway down the river, Lance frantically fired as soon as the Vietnamese civilian reached out to a basket. She was just trying to protect her dog. This realization left the whole troop baffled, as the enemy should only be associated with inhumanity, not love for animals. As Willard explained, dehumanizing the enemies became the way to live, “we’d cut them in half with a machine gun and give them a Band-Aid.” Somehow, it was easier to impose the America’s mentality of war than acknowledging that the people they just killed were not that different from them.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Horror, The Horror! (Post 5)

Comparing the settings and themes of Apocalypse Now and its inspiration, Heart of Darkness, a novel by Joseph Conrad

“The horror! The horror!” Colonel Kurtz’s last words in Apocalypse Now echoed Kurtz’s dying words in The Heart of Darkness. While the movie is loosely based on the book, there are several plot differences in the time, setting, and characters. This post juxtaposes the two works’ settings and themes.

Setting: Heart of Darkness (1899) narrates the story up the river of Marlow, a riverboat captain working for a trading ivory in the heart of Africa. On the other hand, Apocalypse Now (1976) follows captain Willard in the 1970s up the Nung River to testify the violence of the Vietnam War. While the plot moved from the 19th century to the 1970s, the destination for both stories is Kurtz – the character who had gone beyond the authority’s limits to acquire power for himself. In both cases, the men were to be eliminated because they had seen through the motives and brutality of their respective organizations.

Theme: The setting helps portray two major themes in both the movie and the book: dehumanization and imperialism. In Apocalypse Now, the scene of the French rubber station hinted at past colonialism, and the U.S. army marked imperialism. In Heart of Darkness, the trading ivory is the embodiment of both imperialism and colonialism. Interestingly, in both cases, the company employees and the soldiers dehumanized the enemies – the native and the Vietnamese, to justify their causes. Oftentimes, the civilizers turned to technology/ military power instead of conversing with the “savages”. Throughout the process, blinded by their own desires and the pervasive violence, the characters started dehumanizing everyone around them, and eventually themselves.

In his critique of my posts, Teddy pointed out how the timing of the book and the movie impacts their messages. While Heart of Darkness was written in the midst of the Age of New Imperialism, Apocalypse Now was made after the war had ended. Willard’s and Marlow’s viewpoints throughout their journey reflected this discrepancy. While Marlow was exploring dehumanization and imperialism along the journey, Willard had already witnessed the war’s inhumanity. Their reaction to Kurtz also differed.

In Apocalypse Now, Colonel Kurtz was killed by Willard instead of dying from illness on his way back to the authority. The death of Kurtz in the movie bears significant meaning. Willard, weary by the war, increasingly resonated with Kurtz and his philosophy. After he killed Kurtz, he confronted hundreds of natives who were bowing to him and ready to comply with his wishes. Although he had come close to joining the world of darkness, he resisted. It is this resistance against madness and immorality that made the most striking difference to me. In Heart of Darkness, Kurtz was an aberration that eventually died. In Apocalypse Now, Kurtz could be anyone who has seen through insanity and meaningless violence.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Happened and What Got Told (Post 4)

“Apocalypse Now” opens with a vast tree line being bombed; helicopters circling a village now on fire; and the sound of engines in the air. The images soon got mixed with the sight of a room, where an intoxicated man lies staring at the ceiling, firearm by his pillow. Does the sound we are hearing come from the helicopters or the fan in the room? We soon realized that the helicopters and the bombed village are just the man’s illusion. At that moment, his narration started. We learnt why he ended up in Sai Gon, waiting for another mission. We saw him receive his mission. And we followed him through his mission, as he traveled with his troops through different stops on the Nung River. Right from the start of the story, we had been introduced to the man – captain Willard. As the story progressed, we continued to see the world through his eyes. In other words, we experienced the story as it happened to Willard.

As such, our worldview was limited by what Willard knew and was willing to tell. We never learnt about the missions he had carried before the first scene, and how they left him traumatized and emotionless at times. However, through his interaction with other characters, we could glance at what happened long before the opening scene. The most notable example was Kurtz. Although we learnt that he was the target to be eliminated in the first 10 minutes of the movie, we did not witness his cruelty and craziness until Willard arrived at the island. Likewise, we looked at Kurtz’s profile – his education and achievement in the army, but we did not know his story until Kurtz himself told Willard what had triggered his action.

When viewed as a story about Kurzt, “Apocalypse Now” does not appear chronological. Nevertheless, if we consider it a story about Willard’s world and his perception of the war, what happened and what got told matched. In that way, the story started with a traumatized Willard and ended with another Willard, who had seen through what would happen at the end of the journey.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Characters Up the River (Post 3)

Captain Willard: assassin/ protagonist/ indifferent bystander of the story. The movie opens with intoxicated Willard, back in Vietnam for the second round, waiting for a mission. Our perception of the storyworld pretty much follows Willard and his surroundings. However, we can only imply what he has experienced long before that opening scene – the murder and insanity of war that has made him immune to violence and avoidant of human contact.

* The face Willard has in the first photo is pretty much his expression throughout the film.

Captain Willard���s crew on the patrol boat:

Clean – the seventeen-year-old from South Bronx. He gets excited about music, girls, and motorbikes. He doesn’t really know how war works.

Lance – Californian surfer. As the movie progresses, he loses his calming posture and sense of reality, indulging in drugs and starts wearing camouflage on his face.

Chef – war hatter, prone to emotional breakdowns. However, it is Chef who refuses to let Willard continue the mission by himself.

Chief – the navigator who follows orders, despite disagreeing with the mission and Willard’s lack of direction.

(Left to right: Chief, Chef, hidden-face soldier, Clean)

(Lance)

Characters on the journey into the heart of darkness:

Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore – the haughty and heroic commander of the Ninth Air Cavalry. One moment he is bombing a village; the next he is giving out water to a Viet Cong, only because that Viet Cong is wounded, defenseless, and therefore no longer the enemy. Kilgore’s action seems senseless. He orders his soldiers to surf on a beach amidst a bombing mission. He hands out death cards to corpses. He loves the smell of napalm after a win. He only agrees to assist Willard’s crew upon learning that there was a nearby beach suitable for surfing. To him, war is a game.

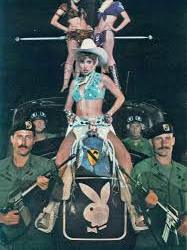

Playboy Bunnies – embodiment of both the innocents and empty values. They appear in an entertainment show for the soldiers, only to be attacked by a crowd overwhelmed with selfishness.

Green Beret Colonel Kurtz – Willard’s target. Haunted by his experiences during the war, he turns himself into a godlike figure for the Montargnard army he commands. He likes saying grand things about horror, morality, and death.

(Kurtz)

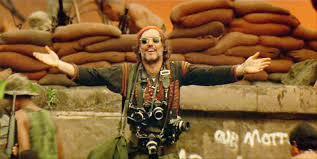

The Photojournalist – Kurtz’s worshipper. His most notable line to me: “Why would a nice guy like you want to kill a genius? Why? Because they told you he was crazy? The Colonel is not crazy. The man is clear in his mind, but his soul is mad.”

(The photojournalist)

Captain Colby – the man sent before Willard to assassinate Kurtz. He gets inculcated into Kurtz’s philosophy. He appears briefly with a riffle, silent and surrounded by the Montargnard.

(Captain Colby)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Apocalypse Now (1979, dir. Francis Ford Coppola)

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mapping (Post 2)

Although the movie was filmed in the Philippines, it details the journey up the river from Vietnam into Cambodia.

What Exists in the Real World

In the beginning scene, the protagonist woke up in Sai Gon (now known as Ho Chi Minh City), the headquarter of South Vietnam. He was then transferred on a helicopter to Nha Trang, a city along the coastline. Both Sai Gon and Nha Trang still exist today.

What Exists in Apocalypse Now World

The Nung river, the main backdrop of the movie, is nonexistent. If we speculate that the Nung river is indeed the Mekong, which runs through southern Vietnam into Cambodia (the red line on the map), the area to the south of Sai Gon (Ho Chi Minh City) is where the story took place. The post where the protagonist entered the scene is likely near Chau Doc, near the border with Cambodia.

What is inconsistent with reality about this hypothesis is that the beach, jungle, scorching heat, and humidity that appeared throughout the movie are not characteristic of this area, but more of central Vietnam. In addition, in one scene of the movie, the troop came across an isolated rubber plantation, a remnant of the French era. Historical accuracy notwithstanding, this type of plant is also unlikely to grow in the lowland delta of South Vietnam. However, the plantation scene can be seen as a deliberate effort to put the image of past Vietnam and the characters’ experiences side by side.

The storyworld of Apocalypse Now, therefore, is in part real and in part fictional. While most of the landscape is likely based in central Vietnam, from the coastline across the highlands to Cambodia, the fictional Nung river narrates the transformation of the characters as they witnessed the ruthlessness of war along each stop of the journey.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Re)introduction to War (Post 1)

Daytime. Scene: A barren field next to a river; soldiers and civilians running amok. The commander spoke into his walkie-talkie, “I want that tree line bombed.” A woman carrying a baby emerged, crying, “Dear sir, please save my baby.” The commander sent the woman and her child to the hospital. One moment, he was saving innocent people. The next moment, he blew off a village – houses, enemies, civilians, lives. He recounted to his soldiers:

“Don’t worry. We’ll have this place cleaned up in a jiffy, sons.

[…]

Do you smell that? Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning. You know, once, I had a hill bombed for 12 hours. When it was all over, I walked up. We didn’t find one of them, not one dingy body. But the smell … You know, that gasoline smell. The whole hill … smelled like … victory.”

To many viewers, this scene realistically portrayed the violence and chaos of the Vietnam War. Just the mention of napalm, a mixture of gelling agent and fuel that sticks to skin and burns, brought back the image of the Napalm Girl and the terror of war.

(Napalm Girl, Nick Ut, 1972)

Apocalypse Now (1979) was filled with such scenes, depicting both the humane and inhumane that evolved in times of war. As much as I appreciate its plot line and style, I would not agree with the statement that its director, Francis Ford Coppola, made at the film’s opening, “My film is not a movie … My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam.”

The movie was not Vietnam to me. When I first watched it a couple of years ago, it struck me how little of a role the Vietnamese cast played throughout the film’s 147 minutes. Whenever a Vietnamese showed up, no matter what side the person was on, he or she appeared helpless, dumb, and silenced. Oftentimes, their dialogues fell flat. The Vietnamese faces and landscapes were only the backdrop for the stories of Americans and their struggles.

It only struck me recently that I did not know what Vietnam was like either. Growing up in Northern Vietnam twenty years after the war ended, although I never fully believed in the version in state-censored textbooks, I never prodded the adults to tell me what they had been through. The Vietnam that I knew was put together by incomplete pieces of narratives, fiction and nonfiction from both sides, and my traveling experiences to trace through the past.

This is the reason why I want to explore the storyworld of Apocalypse Now. First, I want to examine the themes of the film and other Vietnam War movies in this period through the American narratives. In this process, I will try to make out what parts of the movie resemble (the) Vietnam (that I know), what parts don’t, and whether Coppola aimed to portray reality in the first place. Second, as the script of the film was borrowed from “Heart of Darkness”, a novel placed in a completely different setting, I want to juxtapose the two to determine how physical boundaries contributed to a viewer’s sense of the storyworld. Lastly, I am curious to analyze the importance of genre and character building, as it is not the Vietnam part of the war that lives on in video games, fan-fiction, and movies.

It was the past that intrigued me to start this project. I am curious to see where it will take me.

3 notes

·

View notes