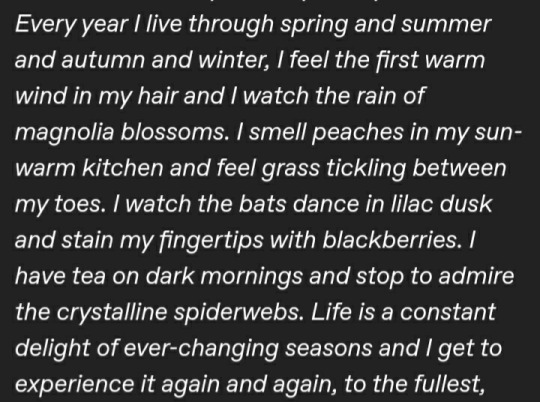

Text

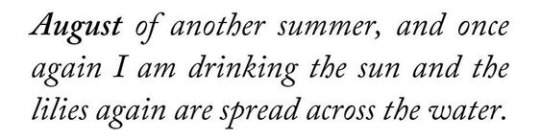

"here lie those who loved life and could not find a way to live it" x

14K notes

·

View notes

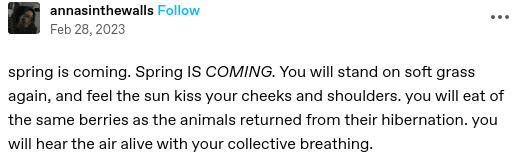

Text

This letterboxd review of Saltburn is sending me 😭

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

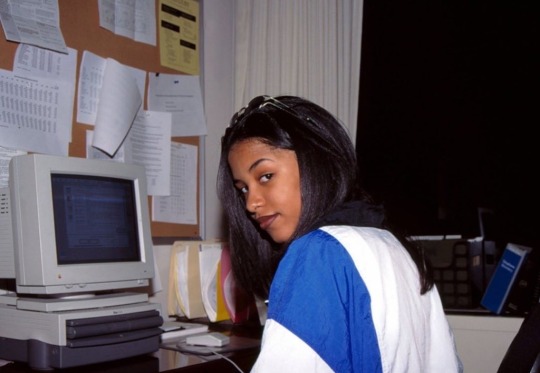

Don Toliver and Kali Uchis are expecting their first child together❤️

85 notes

·

View notes

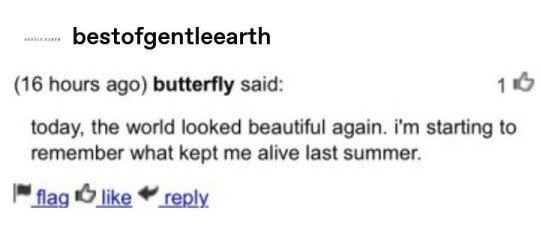

Text

i will no longer be embarrassed i will no longer be a victim of insecurity i will no longer plague my mind with worries i exist i am allowed to exist i am allowed to take up space i will not let others dictate my experience i will live i will live i will live

83K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hideki Otsuka aka 大塚日出樹 aka Otsuka Hideki (Japanese, b.

1971, Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan, based Yokohama, Japan) - Team Kuroneko, Photography

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cho Giseok for Vogue Korea (2023)

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boy with a Basket of Fruit, 1593/5

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Villa Borghese, Rome

Oil on canvas, 70 x 67 cm

“This painting dates from the beginning of the artistic career of Caravaggio, who, having come to Rome from Lombardy in the last decade of the Cinquecento, worked briefly for the Cavalier d'Arpino and his brother, Benardino Cesari. It is thus no coincidence that this canvas belonged to the Cavalier d'Arpinom from whom it was confiscated, together with other works in 1607. It was in Cavalier’s studio that, according to Giovanni Pietro Bellori (1672), Caravaggio learnt ‘to paint flowers and fruit so well imitated that everybody came to learn from him how to create the beauty that is so popular today.’ The present work was produced during his early period as a painter of still lifes; datable to 1593/5, it may be related to his famous Basket of fruit in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan, executed c.1596. As in that work, the fruit and leaves are depicted with the same irregularities and imperfections that are found in nature. The inventory of 1693, which describes the painting very precisely, refers, however, to “Michalan Garavagna”. During the 20th century the attibution to Caravaggio, which first appeared in the inventory of 1790, was questioned by some art historians.” (The Borghese Gallery catalogue, Touring Club Italiano, 2000)

“The three-quarter length figure of a curly-headed youth, who turns provocatively towards the viewer revealing a naked shoulder, is silhouetted against a pale luminous background. The boy holds a basket piled high with fruit. Apples, cherries, figs, pears, pomegranates and red, white and black grapes spill over the edge of the basket while the protruding leaves seem about to fall. The boy has sometimes been identified as a fruit seller. Like the so-called Sick Bacchus, Boy with a Basket of Fruit entered the Borghese collection through the notorious sequestration of Cavaliere d’Arpino’s property in 1607. It is listed in the Nota de’ Quadri as no. 56, but without the author’s name. Since 1693, when the inventory of the Palazzo Borghese was drawn up, the painting has always (except with very rare exceptions) been attributed to Caravaggio. There have been numerous interpretations of the painting’s subject. On the one hand, it has been seen as a poetic elegy, and on the other as a symbol of love, in particular the love of Christ which redeems and offers eternal life. It has also been called a personification of Autumn. Frequently, like many of Caravaggio’s youthful works, it has been interpreted in psychological terms. Caravaggio’s presumed homosexuality is thought to be self-evident in these works. Derek Jarman’s highly dramatic film Caravaggio (1986) certainly reinforced the homosexual interpretation. The dating of The Boy with the Basket of Fruit has been the subject of some controversy, oscillating between 1589 and 1596. Most scholars now agree on 1593-4, placing it among works executed shortly after Caravaggio’s arrival in Rome. In the Sick Bacchus the boy was the focus of attention, whereas here the youth and the basket of fruit are of equal importance. The basket of fruit is perhaps Caravaggio’s first genuine still-life. If Cardinal Federico Borromeo, who was in Rome at this time, had not seen this picture, he might never have thought of commissioning his own Basket of Fruit.” (The Genius of Rome 1592-1623, ed. Beverley Louise Brown, Royal Academy of Arts, 2001)

"Caravaggio’s painting has no readily recognisable subject. Whereas his Boy Bitten by a Lizard and his Bacchus, in which a similar combination of single figure and still life occurs, are concerned with the drama of a given moment on the one hand, and the characterisation of the god of wine on the other, the artist here provides no easy indication of how we should interpret his painting. It is an apparently straightforward representation of a cheeky, attractive boy holding a busket full of luscious fruits, presenting both them and himself to the viewer.

Although the circumstances under which Caravaggio painted this work are uncertain, it seems possible that this is one of the paintings his early biographers say that he made for the open market - that is to say without taking into account the tastes or specifications of a particular patron. If that is indeed the case, it may primarily have been intended as an exemplum of his skills and talents, meant to appeal to a potential buyer for the brilliance of its execution following the general criteria that Giusiniani later enumerated. However insistently real the human and vegetable objects might appear - and Caravaggio has taken particular care in transcribing his observation of the fruits - it is also highly artificial in its presentation of the boy, who is set against a neutral backdrop with his hair carefully arranged and his tunic slipping seductively off his shoulder. There is no attempt to contextualise him, or to specify, for example, that we are to recognise him as a fruit-seller from a street market. The apparent realism with which both the boy and the fruits are depicted have in fact more to do with artifice and illusion than with any attempt at narrative or anecdotal verisimilitude. Caravaggio may well have painted it with this intention, bearing in mind one of the classic texts about illusionism that was known to all connoisseurs and educated artists at the time.

In a well-known passage, the ancient Roman author Pliny the Elder, whose writings are a major source of information about the art of classical antiquity, speaks of a painting of grapes by the Greek artist Zeuxis, which were rendered so realistically that they deceived birds, which tried to peck them. Elaborating, he describes another painting in which Zeuxis painted a boy carrying grapes. When the birds came to peck at these, Zeuxis chided himself for having painted the grapes better than he had painted the boy, for if he had succeeded, the birds would have been frightened away.

It had become a common conceit in the 15th and 16th centuries for artists to attempt to recreate lost paintings described by ancient authors. If it was, at least partly, Caravaggio’s intention to emulate Zeuxis’ lost work - and the celebrated still life in Milan may well have the same idea behind it - this would explain the illusionistic qualities that come to the fore in this painting. It is one of the first in which Caravaggio ises the hard, slanting, ray of light that in later compositions, such as the Supper at Emmaus, he was to employ to such expressive purpose. Here it picks out the boy’s bare shoulder, giving a sense of heightened reality to the figure, and plays across the fruit allowing Caravaggio to show off his skills in defining the surfaces, contours and colours of the apples, cherries and grapes. For all the apparent naturalism with which the boy is presented - and that too is a product of the way he is illuminated against the neutral background - the picture remains a highly artificial conception that is more concerned with the power of illusion and with the artifice fo art than with the straightforward delineation of a figure and a still life.” (Rembrandt/Caravaggio, Duncan Bull, Rijksmuseum, 2006)

“M. left three paintings behind when he moved out of Cesari’s workshop. One was his own Sick self-portrait. Another was the Boy peeling fruit. The third was another single figure with fruit. Now the shadows were sunk to the lower background and a younger bare shouldered boy with thick dark tousled hair and head tilted languorously gazed at you through lazy eyes with lips parted. He was being painted from life and it was hard to hold the pose. He held a very full basket of ripe autumn fruit - an apple, a pear, black grapes, red grapes and white grapes, a late peach, a couple of split dark figs and a burst of pomegranate, with plenty of scarred leaf and stalk and one dying spotted vineleaf drooping upside down into the picture’s bottom corner. The boy’s shirt looked like an off the shoulder bed sheet.

The softer light that ripened the fruit warmed the boy too. His dark hair was outlined against the glow and his cheeks tinged like the peach and the apple and his body emerged from the shirt and the shadows below like the flesh of the figs and the pomegranate. Ripeness, availability and the briefness of earthly pleasures were all there to be seized on. The painting itself seemed entirely taken with the reality it showed. The exposed part of the boy’s body, that nexus of shoulder, neck and collarbone nearest you, was rendered with such loving attention to its detail that it outgrew the framing picture and was anatomically odd, though the painting let you forget it. Peterzano had done collarbones like that. The simplicity and the physical intimacy were as startling as the self-portrait’s. There was nothing beyond the fruit to mediate or distract M’s contemplation of the boy. Like the self-portrait it plunged you into the enigmatically private. The puzzle never lessened. All of M’s paintings would confront you and disconcert you with the intimate reality ofindividual life but personal meanings were elusive. The later images rarely matched the flickering data of the life as closely as they did now, in the only work he did entirely for himself, unpressured by a client. The Sick self-portrait matched all the early notes on M’s hard times and sickness when he came to Rome. The Boy with fruit was more than an object of desire, sweet but not idealised, entirely right as a Roman greengrocer’s boy taking a pause in his rounds - although more than one connoisseur over the centuries would take him for a girl. It was a portrait of Mario Minniti and it was full of sexual longing, though not on Mario’s part.” (M, Peter Robb, 1998)

16 notes

·

View notes

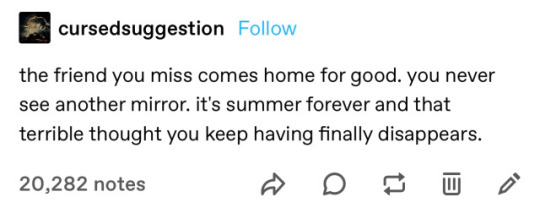

Photo

literally me.

Alexandre Cabanel. 1863. The Birth of Venus detail.

1K notes

·

View notes