Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

OK, the idea of Thing as the baby of the family is an idea I didn't hit on. To be honest, I always thought of his third role (beyond "uncle" and "angsty older sibling to Johnny's rambunctious kid") as being him at his LEAST depressive, and most protective, at which point I kinda think of him as like a big friendly dog that can talk.

which mainstream supes do you think work best in the time they originally appeared (WW in WW2, FF in the 60s Space Race, etc) and which should be kept in modern continuity?

This is a complicated question, because the nature of the superhero is that most of the oldest ones are easiest to justify in their initial publication context, many of the ones introduced later are disguised genre-throwbacks that also would integrate fine in that first-wave context, and there's also a selection pressure where the character concepts that can survive a retool in line with contemporary sensibilities are already the ones that have survived to the present day.

The Fantastic Four are illustrative of this. As you've pointed out, the base concept is intimately tied to the cultural moment of the 1960s in several ways; the impetus of the team's formation being the space race, for example, but also Ben Grimm's design being an attempt to align with the monster-and-kaiju comics that were ascendant at that time in case the superhero angle flopped and they needed an escape hatch into a "safer" genre. Moreover, it's long been remarked that the FF are interesting in that they were some of the first heroes patterned on the archetypes of the nuclear family as it existed in the mid-century imagination, despite the fact that initially, they weren't one. Reed as the pipe-smoking patriarch, Sue the blonde bombshell housewife in training, Johnny the fiery teen heartthrob reigned in by his elders, and Ben, most interestingly, splitting his time between the role of the Uncle, the role of Johnny's bickering sibling, or the role of the baby of the family (during beats where he's seriously crashing out regarding his monstrosity and "throwing a tantrum.") Down to the bedrock, very much of the 1960s.

They demonstrably don't have to be, though. The most practical example can be found in Ultimate Fantastic Four, the early-oughts retool of the entire concept. The core element that was maintained from the sixties, besides the fact that there are four of them, was the focus on exploration- going places and seeing things that nobody had before. Since the space race was a distant memory the accident that gave them their powers was a military-bankrolled attempt to construct a gate to Negative Zone, Stargate style; the political context shifted to that of the End of History and the Great War on Terror, the intended military application of the technology being teleportation-assisted bombing runs on targets in the Middle East, and the FF's proximity to that was treated as a way in which they were morally compromised, their dream (really Reed's dream) of Boldly Going underwritten by the military industrial complex. Rather than a nuclear family the four are an age-equitable peer group and the internal animosities are much more aggressive and validated by the narrative; Reed's silver-age thoughtless amorality was retooled as a deliberate character flaw and pain point in the group dynamic. The result of this was about 20 issues of a really, really compelling comic, which maintained the skeleton of the original concept but was clearly its own animal, best suited to its own moment.

You can, theoretically, slide them around even more than this. I've mentioned in passing before about how when you dial in on exploration The Four could be made to fit neatly into the mold of 1930s science heroes, with expeditions into the Hollow Earth and unscientifically-habitable planets in our solar system; a lot of their classic silver age adventures are already throwbacks to this kind of plot, you don't need to move much around. If they'd debuted in the 1980s I think they'd have been pattern-matched to the protagonists of Star Wars, they'd have been extragalactic space-opera explorers in the vein of Marvel characters from that time period like The Starjammers or the initial GOTG lineup. You can push them even earlier, too; they function fine as Verne-style Aethernauts or some similar thing in the Steampunk elseworlds, and they function pretty well in Marvel 1602 as sea voyagers altered by events in uncharted regions. They're still around because that core conceptual kernel is so versatile, functional in any time period where Thinking About Going Somewhere Else was part of the zeitgeist.

Wonder Woman is a slightly different beast; there's a sense in which she really does work best in her original 1940s context, because of the idiosyncratic, contextually-progressive-but-also-still-Deeply-Weird-About-Women-On-A-Different-Axis politics undergirding the original book, and the unique publication inside baseball that kept her alive outside of that moment. On the other hand, she's been successfully retooled for the modern era for a reason; there's always a War On (even if no modern characterization is likely to act as a booster for that War the way she did in WW2) and there's always a Gendered Inequity that needs to be addressed. If you're willing to tinker you can have her make landfall in America at any point in the past 200 years and there'll be some kind of work for the Amazonian Ambassador of Peace.

Anyway, to move on to something resembling a specific answer to your question instead of just endlessly nitpicking your examples; Batman: Caped Crusader wasn't my favorite Batman thing by a country mile, overall I'd give it like a seven-out-of-ten. But what it kept beating me over the head with was the sheer number of contemporary Batman storytelling problems that went away by virtue of their decision to go all the way back to the 1940s and execute the original Golden-Age character concepts with the backing of an Amazon budget.

The ubiquity of the Mob? Perfectly justified, it's set when they actually were ubiquitous and a major political force. People in the entertainment industry like Penguin and Clayface living double lives as criminals? Contextually perfectly plausible; on top of loosely mirroring the criminal connections of golden-age entertainers like Frank Sinatra and Errol Flynn, the modern digital panopticon doesn't exist to make such a double life implausible. The lack of the modern security state makes all of the "respectable" citizens with double identities plausible- Batman, Catwoman, Harley Quinn; ditto the existence of complete cyphers like Joker and Onomatopoeia. You've got the cavalier join-the-circus attitude towards orphans that'll eventually facilitate the position of Robin. You can have plots like "Moving Target" that would be trivialized by the existence of satellite communications. A literal Ghost can show up and attack people on the subway without any kind of knock-on worldbuilding concerns because nobody on that train had a cell phone. On and on and on.

The show wasn't totally innovative on this front because to an extent, this is also just an exaggeration of what Batman: The Animated Series was doing with it's Dark Deco house style; making Batman plausible by situating him a twilight zone between where it's either the 1930s or the 1990s depending on the needs of the plot. Likewise, the environmental design for Superman: The Animated Series understood that characterizing Metropolis as a gleaming retrofuturistic throwback helped to defang the implausibility of a flying guy in tights. But, on the whole, Caped Crusader demonstrated to me that there's a ton of mileage in setting Batman in the 1930s and 1940s the way you'd set a modern Sherlock Holmes adaptation in the 1890s- it's their home territory.

But, to bring this whole thing full-circle, Caped Crusader is also contemporary with, and deliberately running in the opposite direction from, The Batman, which is a take on the character that's so heavily dependent on being recognizably set in the 2020s that several of the themes and plot beats implode absent that fact. Which, ultimately, is my point; there's a strong and up-until-now underexplored value proposition in adaptations that are high-fidelity period-piece executions of the original character concepts. But these characters ultimately belong anywhere you can sell them as belonging.

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

That's so mean, it loops all the way back around and becomes hilarious.

if it makes you feel better i showed up for the parahuman part it just so happened to be steven

Man I gotta finish that write-up of Steven-as-a-second-gen-bud of renowned at-large Maryland-area cult leader controversial independent hero Rose Quartz, thank you for reminding me

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yeah, honestly, I don't think this question is hard to parse. The reason is 1. Violence is inherently exciting to our monkey brain, it creates a sense of tension and danger, and the existence of violence often implies a cause of the violence, which is an antagonist, and, boom, built in conflict, the centerpiece of storytelling in general. 2. Pursuant to that first thing, the sense of tension and danger that makes violence exciting is easier to do with villains who we know can actually pose a threat. Especially for superheroes, who, by nature, exist in a larger-then-life space of reality. They have grandiose titles, likee "THE WORLD'S GREATEST DETECTIVE" or "EARTH'S MIGHTIEST HEROES" and that means you need to create threats that feel like they could challenge them. After a decade or so, we know no mere normal assassin could pose a real challenge to Batman, no, he's a step beyond crime-fighting, and, let's be real, HUMANITY as we know it. He needs a SUPER-criminal. It's way more exciting to watch Superman fight Darkseid then it is to watch Superman effortlessly pummel some mundane bank robbers who still haven't figured out bullets won't do anything. I do agree with your point, that superheroes are, in many ways, how we launder our fantasies of dishing out karma to people we think deserve it. Not even necessarily a bad thing, honestly. After all, Superman was created by two Jewish immigrants in a time when anti-semitism was rampant, and Adolf Hitler was gearing up to start some shit: It's kinda understandable that someone faced with those terrifying horrors would want an escape, a hero who could actually defeat these problems too large for any one man to solve, so, they created a fictional man who COULD. Even in those early comics where Supes is just punching out domestic abusers and the like, it's also serving as kinda a symboylic stand-in for fighting back against the broader societal ill they represent. But, yes, it can get very ugly in the wrong hands. It varies, ya know?

Is there any reason why most superhero characters are programmed to fight villains as their primary means of enacting justice,other than that readers and viewers enjoy the fun of action scenes and have morally satisfying motivations?I mean that there should be many super powers or super technologies that can help others through means other than force,do you think that "frequent use of force" is one of the core of superheroes,or it's just based on business considerations or genre habits?

It's partly the arms race of spectacle and partly downstream of the zeitgeist. In the very early days they weren't always fighting "supervillains" as we understand it- they were fighting, like, the mob, or specific gangs of bank robbers, or in actual no frills World War 2, or any number of other things. "Supervillains" were a dual emergent property of A.) individual flamboyant antagonists simply being more fun for the heroes to fight than Blackmailing ring # 456, and B.) the fact that the advent of the Comics Code Authority made depicting most kinds of grounded, gritty or materially motivated crimes- drug crime, sex crimes, war crimes, government corruption, etc.- a non-starter- hence all the wacky themed museum robberies and so on in the fifties. From the 60s onward they did start to pivot back towards heroes fighting supervillains who were essentially caricatures of whatever the current real-life cultural boogeyman was- communist agent supervillains, then drug-dealer supervillains, slum-lord supervillains, cartel-boss supervillains, Islamic Terrorist supervillains, Satanist supervillains, Televangelist Supervillains, 90s street-gang supervillains, neo-nazi supervillains, on and on. Basically a scattershot battalion of every cultural archetype that a substantial slice of the audience, right wing or left wing or thoughtless undecided who saw something concerning on the news, would enjoy seeing plastered in the iconography of a "supervillain" so that somebody would finally be able to just punch their lights in. These days you get a lot of CEO supervillains, Military Industrial Complex supervillains, gentrifying developer supervillains, Influencer supervillains. A few years ago Tom King wrote a two-pager that was about Batman beating the living hell out of a wife-beating, otherwise untouchable MMA star in a televised charity cage match. The archetypical cornball supervillain who maps to nothing and no one besides themselves was the product of a brief and contingent moment. Other than that, for good or ill, progressive or reactionary, supervillainy is often how we launder our cultural baggage about who we think currently has it coming.

And, you know, the reason the stories are about this and not fixing the world some other way aren't exactly opaque. You basically got it in one within the body of the ask itself, I don't need to explain it further. Whether any of this is at all productive is basically Baby's First Superhero Deconstruction Premise, and the obvious out-of-universe reason why this is the case means it's very easy for this line to fall flat unless the writer has come up with a very unique spin on it. I personally don't draw a distinction between "the core of superheroes" and "mere business consideration or genre habits-" the core tenets of every genre is informed by what sells, or, in non-commercial spaces, what keeps the audience coming back. That's what Genre is.

107 notes

·

View notes

Note

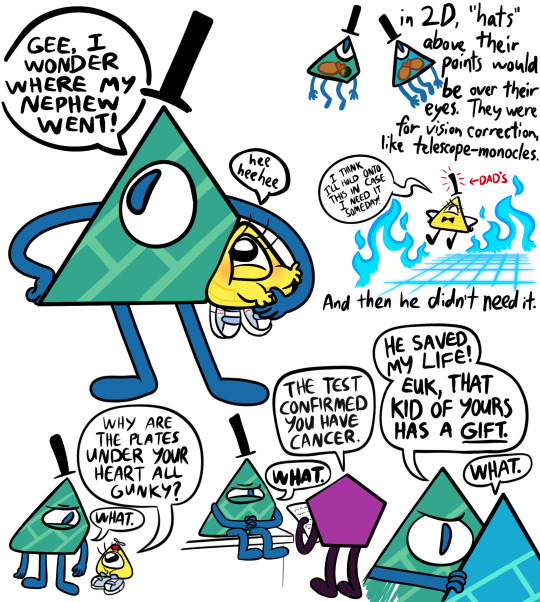

Yeah, I was gonna say. Bill parreals Ford just as much as he does as he dies Stan and Mabel. He certainly does given what we learned in the Book of Bill.

*looks at euler* *looks at ford* oooh so bill has the uncle version of an oedipus complex /J

I'd rather not go that direction even in jokes.

It ain't even accurate. Bill emotionally latched onto Ford at a point when the only familial role Ford identified with was "son"; "an uncle" doesn't even make the list of terms Bill would think of when asked to describe who Ford is; he looks down on Ford as a follower rather than up at Ford as a role model/authority figure; and he sees himself when he looks at Ford—star-seeker, social pariah, aching for fame and recognition as compensation for a childhood of rejection, a life defined by being born with a mutation that changes the way he looks at the world—not his well-adjusted normie uncle.

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

As I kept reading, my eyes kept widening until they were the size of dinner plates. The line from Euclid, tying Pyramid Steve's "Eat Copper Wires" thing to Bill's twin fixation. And, and, this ties into how Dipper nearly died in the womb, since Billnis specifically parrealed with...Well, every member of the Pines family, but moreso Stan and Mavel, and, given Steve's appearance, he certainly looks like the other half of that dynamic...If Bill had been in close proximity to another child, someone he would have to learn to get along with...If he hadn't alwalys been the center of attention, the golden special boy who the family depended on but also exerted total control over...If he had just had ONE person he could think of as a peer and not a worshipper or a prison guard...Well...There's something so Gravity Falls about the idea that evil starts at home, that even the most fantastical creature is, at heart, somewhat mundane. In this case, two con artist abusive parents helped craft the future greatest terror of the multiverse, and it just...It's...WOW. This is brilliant.

i am FASCINATED by the little scraps i've heard about bill's uncle. am i allowed to know more about him. and if the answer is no do you have a chapter estimate for when i am

yeah sure, I already made a post on Bill's mom, I've finally got enough material to make a post on Bill's dad.

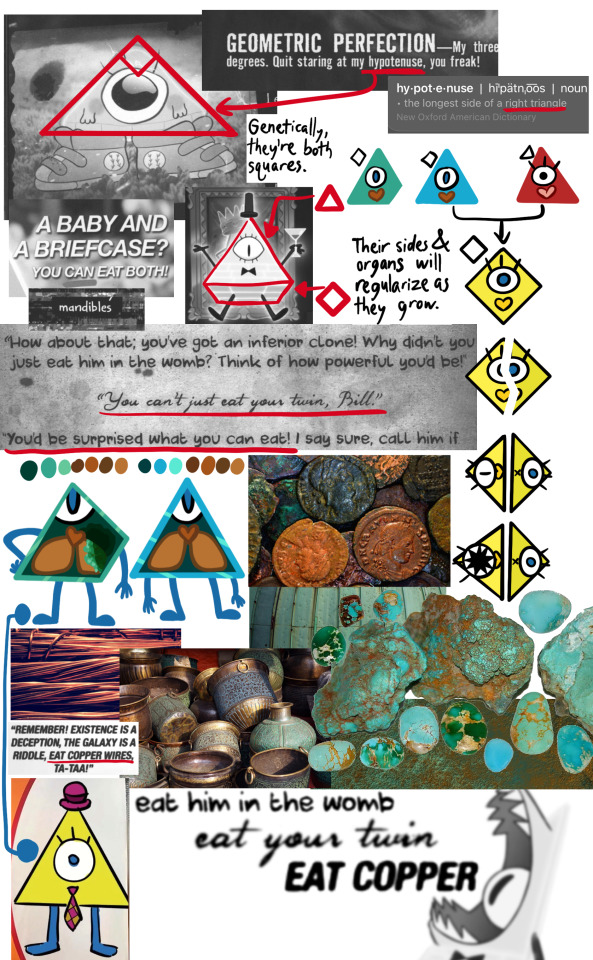

Bill got his gorgeous eyelashes, warm color scheme, black limbs, and personality from his mom. He got his shape, his brick lines, and his slitted pupil from his dad. His dad's a self-made businessman*! (*His dad got suckered into joining a multi-level marketing scheme and now he makes money by suckering other people into joining the MLM scheme.)

And: his dad has a brother. They're twiiins!

Bill keeps targeting twins. (The Stans, the kids, TBOB says Pyronica's got a twin sister Hydronica...) I imagine Bill's twin obsession is rooted in something close to home.

Because Euclid & Euler's eye split in half mid-development, they have unusually oval-shaped eyes—a common sign of twins. They've been going to an optometrist since they were toddlers to deal with poor eyesight and floaters in their peripheral vision. They've had a mix of surgery, corrective lenses, and medication to narrow their field of view to the area they can see clearly. So when baby Billy said he was seeing "bright white dots" on "the outside of everything," Euclid went aha! He knows exactly what Bill's seeing!

He did not, in fact, know what Bill was seeing.

Bill's parents didn't regularly visit family, but Euler was the one relative they saw most often. He was the first person to snap out of the "haha it sure is funny how Bill can guess when somebody's about to knock on the door" rationalizations to realize that Bill really could see things no one else did.

And since Bill's parents are sort of disasters who think starting a cult is a great get-rich-quick scheme, Euler was one of the most emotionally stable role models in Bill's life. It sure is a good thing that Euler was a constant presence and nothing happened to him during Bill's tender formative years!

"But wait," you say, "you told us that Bill got his shape and slit pupil from his dad. But wouldn't that mean he got genes for a square? And how could he have gotten a slit pupil if that wasn't a genetic trait, but a consequence of an eyeball splitting in half?"

Triangles and slit pupils don't run in Euclid's side of the family. But squares and twins do.

I imagine Bill's twin obsession is rooted in something close to home.

"So Steve exists in your headcanon—?" No. He's a stillbirth his parents pretend doesn't exist. He's a crime Bill committed before he was born. He's the imaginary phantom Bill's parents are searching for when they look at Bill—starting fires, hallucinating, spitting up his medicine—and wonder what he'd be like if he was different. He's a symbol representing a source of unconditional love and support that Bill deserved and needed, but never had. Steve's all those things—but he doesn't and never has existed.

And there at last is my Euclid headcanons post. If y'all are interested & didn't see it, here's my Scalene headcanons post! And some headcanons about shape twins that still basically work post-TBOB, we just know now that Euclideans don't need a line and a polygon to reproduce.

(95% of my headcanons about Bill's dad & uncle are pre-TBOB. The only difference is that I originally designed Euclid & Euler as green trapezoids that had split from a hexagon. Trapezoids so that Bill and his dad could do this, green so that Bill's dad could be the original color Bill was designed as before the Gravity Falls crew made him yellow & so that his family could be money-colored: gold-colored Bill & mom, dollar-bill-colored dad.)

(After TBOB/TINAWDC revealed his dad's a triangle and either red or blue, I decided to make the twins blue-green (because I wanted to keep in that "bill's original color scheme" reference) and finagle it so that Euler could still be a trapezoid; after Pyramid Steve came out, I suddenly had a really good thematic reason to make them blue-green. I'd been playing with the idea of making Bill a shoulda-beena twin, Steve finalized that decision by giving me a physical design that could tie into Bill's extended family.)

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ya know, as someone who's only become a bigger Superman fan with age, this kinda reminds me of how Mark Waid recently quit writing Superman because he has lost faith in the American people to do the right thing. Personally...I would point out it's only 3.4% different from what we had before. Whether that makes it better or worse...Up to you.

Maybe I'm just becoming too cynical to engage with Superman at face value. Maybe that's even a bad thing. Not sure though

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yeah, while this is a personal philosophical beef, I will note that I just kinda assumed there are limits as to how much control she can assert over this. After all, when Dream and Destruction stop doing their jobs (or, in Dream's case, are prevented from doing so), the concepts of destruction and dreams start getting fucky, but certainly don't vanish. She can clearly exert some control, but I assume not entirely. Maybe she's saving more people we don't see, maybe not, but I don't think even she has the power to stop all death everywhere if she wanted to. Also, I brought this up in ask, but...Does this view of death as an aberration to fear and be defeated even make sense in the DC/Vertigo universe, where the afterlife and an immortal soul 100% exist?

Can you elaborate on the Sandman Death thing?

"Friendly, chipper death telling a baby that just died of SIDS that one life is all they get" is, to put it lightly, not as sympathetic a behavior as the show wanted me to treat it as- this is, to the best of my recollection, the same show where she deliberately held off on collecting a guy indefinitely to see what would happen, so she obviously does exercise some control over the overall process. Overall the basic character concept abrades heavily against my personal stance on death- you make peace with death not because it's some natural, beautiful part of the process of living, but because there's no way around it until the guys at MIT start channeling their "put cars on top of buildings" energies into something useful for once.

(Terry Prachett's take on the same archetype abrades a little bit less, partly because Discworld is a fantasy setting that frequently flirts with looney-toons sensibilities for all it's grounded commentary, rather than our world unless noted with all the attendant horror; partly because the books go hard on Death trying to do the compassionate and personable thing and coming across as endearing specifically because of the ways in which he has a hard time relating to humans, and definitely because a lot more ink is spilled about his level of agency over the system he's part of and the amount of weaseling around adversarial forces like The Auditors that he has to do in order to intervene directly.)

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

This sounds like "depression, the show".

Yesterday when I was saying I was hoping mean and cynical children's animation makes a comeback, I think a more accurate way of describing what I'm getting at would be marrying the tone of something like Billy and Mandy with the meta-plot of something like SU. Character development but not necessarily for the better. Every week we all learn something about each other, namely that we can't stand each other and for good reasons. Big finale where the victory is that the protagonists limp off into the distance with the faintest glimmer of hope that they'll find a better status quo within which to enmesh themselves. We Are Never Getting Out Of Here, the children's television show

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think that last bit is kinda overly cynical, but...Probably shouldn't be surprised. At the end of these day, these things come and go. Animation ain't gonna die anytime soon. It might see a shift in some way, perhaps towards indie labels or the like, but the big guys will react, and so on and so forth. Competition: It's good for business.

I recall a lot of the cartoons I grew up with in the early to mid ought's being pointedly (and hilariously) amoral and meanspirited, in a way that in retrospect feels like a deliberate "get fucking real" backhand against the "lesson at the end of every episode" stereotype of cartoons of the 80s. The Cartoon Cartoons had a lot of this going on (Billy and Mandy and Ed Edd and Eddy being standouts on that front.) Adventure Time feels like it was riding the very back end of that impulse, through a lens that trended more absurdist than mean- constant nihilistic and moral grotesqueries adjacent to the protagonists but comparatively little that they're directly on the hook for, within realistic parameters for a believably messy world. Regular Show fits in here somewhere. Gravity Falls, at points, although it swings away from full-blown amorality in the back half in obvious ways.

A lot of the contemporary tumblr tentpole darlings (2012 or so onwards) feel like they've moved away from that; not morality plays, exactly, because that implies a level of simplicity and flatness that doesn't align with how highly I think of these projects. But certainly couched within a baseline certainty that the protagonists either are straightforwardly good people whose arc is much more about how to enact their morals effectively, or they're on their way to being straightforwardly good people by the end of the story. This is a cluster containing Steven Universe, She-Ra, Kipo, Amphibia, The Owl House, My Adventures with Superman, a few others. Infinity Train, by virtue of it's premise, feels like it cutting against the grain somewhat, even though it's also clearly coming from a similar place as the rest- a shared optimism, humanism and resistance to black-and-white moral condemnation of any of it's characters. (Maybe one really irredeemable guy, as a treat.)

This obviously isn't any kind of comprehensive or airtight analysis- off the top of my head, I'm focusing on the tone of the cartoon-cartoons to the exclusion of the slew of fairly morally-uncomplicated action adventure cartoons that were airing at the same time like ATLA or the DCAU; and I'm focusing on the contemporary cartoons that tumblr likes over, say, Teen Titans Go or anything in the adult animation space. But under the admittedly uncertain assumption that we have any kind of animation industry at all in a few years, I'm curious to see whether there'll be any kind of visible swing against the ethos of stuff like Steven Universe and The Owl House. Stuff that trends meaner, trends cynical. I kind of hope so. I think I've got at least a couple pitches that could ride that wave.

126 notes

·

View notes

Note

I mean...Isn't that part of what Worm was doing, actually? IE the idea of "what drives someone to do this kinda shit for a living?"(Answer: A vast cocphanoy of systemic failures leading people like the Undersiders to fall through the cracks). And, to be fair, that did turn around and have Taylor get in bed with and, eventually, BECOME that kinda mastermind villain.

I was wondering if youd read Hench yet.

I feel like the premise and the start were solid, and the main character's framing of superheroes through a strict environment cost-benefit analysis was interesting.

But it feels weird that in it's criticism of heroes it just sorta...gave villains a pass. Plus the incredibly loose world building, which early on was a strength in establishing the "you know how this works", vibe, but as the book progresses and the plot hinges increasingly on old interpersonal drama, it's suddenly a big gaping hole.

These are my broad criticisms of it, yeah.

Full disclosure- this is the book I was vagueing about a couple months ago, the one where I got annoyed because the back cover copy was pulling the "no ethical consumption under capitalism" card in relation to working as a henchman, in a way I found disingenuous given that many supervillains are on the face of it much, much worse for the world than the average tech start-up- particularly the kind of supervillain with a staff. But I also thought it would be disingenuous to bitch a book out purely on the grounds of its back-cover marketing department copy, so I bought it and read it. And unfortunately the final roundup on that tension appears to be that villains aren't that bad, are they? Maybe even kinda girlboss even!

Bulleted list under the cut!

The opening is strong, and gave me high hopes, specifically because of how it seemed to be aware of these tensions. Anna, our protagonist, opens as a temp in the employ of a sleazy c-list supervillain who's performative in his interest in his staff's wellbeing but doesn't hesitate to put his interns and temps in the meat-grinder for a leg-up; even a decisive loss to an A-list hero is a way to climb the ladder if you're a C-list villain. On the other side you've got superheroes who are horrifyingly cavalier with the lives of anyone they've deemed to be "on the other side." The protagonist is framed collateral damage in the grand idiot melodrama between two sides that don't give a shit about the lives of the little people in distinct but interlocking ways, and that's pretty compelling- particularly because at this point we're still coloring within the lines of the typical genre paradigm! That mutual self-centered apathy, the ways in which people get pigeonholed into specific roles in the melodrama that define and dehumanize them, drove seven seasons of The Venture Brothers, and now we get the tragicomic spin on that dynamic, we get a story told from the perspective of one of the henchmen or random civilians who get callously offed as part of a sight gag about how awful all of these people are!

That's not where it goes, though. @st-just has a pretty great writeup where they point out that for a story driven by the premise of heroes that cause immense collateral damage and use their institutional influence to dodge the consequences, the story is oddly incurious about the level of damage that Leviathan's enormous criminal organization does in the course of its operations; how many people have died because of all those superweapons he's handing out to lower-level villains? It's all oddly bloodless, and it feels like it keeps pulling back at the last second from the protagonist truly suffering moral injury- or from acknowledging that moral injury. Given how much of her plan involves waging psychological warfare on heroes until they snap publicly, there's a bit of an eric-andre-who-would-do-this vibe coming from then pinning that collateral purely on the heroes. I never got a good read on how self-aware the story is about the fact that Anna very, very quickly becomes attached to real tangible power in a way that makes her underdog framing feel extremely hollow; how quickly she becomes like her former boss, arraigning henchmen in the line of fire for the sake of the Grand Plan. One of those stories where it keeps gesturing but I can't tell the extent to which it intends to commit with a sequel.

The worldbuilding, as you mentioned, is an issue, because there's a failure to clarify quickly enough the larger systems that incentivize the heroes and villains- in fact, it often feels like the characters are operating from within different incentive systems, from different settings. The early sections of the book read like a "Silver-Age-taken-seriously" situation, similar to The Venture Brothers- the casual levels of temp-agency integration, card-carrying supervillain-as-tech-start-up boss, and of course, the myopic violence of free-agent cowboy cop vigilantes-slash-celebrities who never get called to account for it. Halfway through there's a pivot and now there's a Draft, capital-D, and it turns out that this has actually been a superhuman registration setting the whole time? "Supervillains" are actually just any superhumans who don't toe the line? "Superheroes" are screened for in middle schools and separated from their families? That's, uh, not completely incompatible with the aforementioned dynamic but it's a bit of a kludge! There are beats that are really great- Quantum relocating from New Zealand for a chance to partner with Supercollider only to end up subordinated for sexist-marketing reasons, the fucked nuclear family shit going on with Flamethrower and his kids and with the Ocean Four- that imply a level of individual career discretion on the part of the heroes that you'd need to do some work to square with whatever pressures are being exerted by the higher powers. It's actually pretty important who's calling the shots here and to what extent! If the climax is predicated on wanting to overthrow the system you need to make that system consistently visible and legible through the rest of the book!

As you mentioned, the book also pivots into there being a deep interpersonal drama that propels the back half; Leviathan turning out to actually be a former superhero who was dramatically wronged in a morally clear-cut way by Supercollider, who murdered his mentor for inside-baseball cape politics reasons and had this covered up. I've got really mixed feelings on this, because although the seeds of something fascinating are here it feels like one of the ways in which the book is hedging itself. Supercollider's callous but genre-standard disregard for hench lives isn't grounds enough to condemn him, no, he also has to have committed some off-duty murders as well, and he's a shitty boyfriend on top of that, he's a supervillain dressed like a superhero. We get Leviathan's justified grievance, and spectacular violence enacted on agents of an obviously evil system, but no up-close-and-personal villainy- he's functionally a hero with a villainous aesthetic (and a smattering of anecdotes about awful shit that he's done, but the story isn't interested in really making us feel it in the way that it is with Supercollider.) There's a beat that I really liked, where Quantum tells Anna that their respective villainous and heroic bosses care far more about beating each other than they do about the women in their lives or anyone else working under them. I think it was a grave misstep that this turned out to not be where the book went; making it so that there actually is a clear-cut good guy and bad guy in the Leviathan/Supercollider conflict, that they're fighting over something that matters, pushes the entire story dangerously close to what I term "Banal Hatswap" territory.

For more of a vibes-based criticism; and easily my most uncharitable; the entire story is written in a register of self-righteousness, and I have a hard time separating what's meant to be the biased viewpoint of the protagonist from what's meant to be the author Displaying The Correct Applause Lights for Twitter. You've got a protagonist who cracks a one-liner about supporting Penal Abolition.... who also puts out a hit on a guy who slowly dies horribly of sepsis as a result. A one-liner about a female superhero's "suspicious WASP" vibes, right before she emotionally manipulates said hero and arranges to have her kid kidnapped. "It's not my job to kinkshame, buuut," right before proceeding to leverage the embarrassing sexual proclivities of a superhero who's roundly characterized as boorish and misogynistic in conjunction with that. Bemoaning how Quantum, a strong heroine of color, is subordinated and put through the wringer by the patriarchal marketing machine, before acting as the major practical driver in the total collapse of said heroine's life. (This one is the one the protag displays the most self-awareness about, which might be related to the subtext that said superheroine is a potential love-interest.) Grandstanding about and predicating the whole plot on how all human life is valuable and villains don't deserve to receive life-changing brutality.... before being party to Quantum's graphically-detailed levels of payback against her shitty ex Supercollider, I mean we're talking like arc 14 Vicky Dallon levels of body horror and violation here, in borderline pornographic detail. All of this feels like either a very clever reproduction of how the very online know how to say all the right things to launder the fact that they constantly do all the wrong ones.... or it's just. an unreconstructed example of the thing. I can't tell, but the back-and-forth bothers me a lot. It's a situation where it becomes super fucking obvious how much Worm benefited from constant alternate-POV interludes; getting any of this from the head of someone other than Anna would go a long way for me.

Ultimately the book heavily depends on my sympathy for overeducated, temporarily embarrassed white collar computer touchers who throw in with evil worldwrecking conglomerates in exchange for dental. Unfortunately I think we all just axiomatically have it coming and superheroes would ideally pulverize way more of us so there's a level on which I was lost from the word go

Now, for the sake of a balanced assessment I'm going to go over a bunch of the ideas in the book that I did think worked really well:

As mentioned, the opening is extremely strong; the nightmare existence of living paycheck to paycheck as a temp, juiced up by the genre-elements, the slice-of-life hardscrabble existence of a woman at the bottom of the economic totem pole constantly having her attempts at a life worth living blown up by her proximity to this nonsense. Having a date break down because you have to drive your maimed henchman friend to the ER is a fucking amazing beat. Unfortunately the narrative moves away from this low-level approach very quickly, because a lot of what's going on with this thing is that it's a specific strain of power fantasy- a significantly-more-competently-executed version of a kind of villain-falls-for-his-hardworking-assistant Wattpad romance. That's not a pejorative or a criticism, just a kind of power fantasy that requires an end-of-act-one escape from the nightmarish mundanity in order to function. But I like the nightmarish mundanity! Bring back the nightmarish mundanity

The book has some great beats about the intersection of superheroics and women's issues. In a nod to the plight of superheroines from the silver-age and earlier, Quantum Entanglement is a superheroine with reality-warping levels of firepower who's constantly forced to downplay her own presence and individuality in order to help juice up the brand of her male partner Supercollider; in the climax it's revealed that this extended to subtly using telekinesis to create the false impression he's capable of independent flight, which is, implicitly, this settings version of Superman's transition to flight from really big jumps. There's a tendency for superheroines to get big power-bumps in conjunction with an arc about succumbing to a very gendered insanity- Malice and Avengers Disassembled being two prominent examples I can think of- and Quantum's eventual break from the monstrous Supercollider feels like commentary on this. In another one-and-done beat you have the heroine Abyssal, whose career is on the verge of being derailed by her third pregnancy; the catch is that she's a member of what's implied to be a family team (think New Wave or the FF) and her pregnancies are laced through with expectations and hopes that the kids will exhibit powers and be able to pad out the roster. By the end of the book she's mentioned to have been permanently benched, and another member of her team is killed "on-screen-" but that's alright! We've got her three kids waiting in the wings! A deeply grim superheroic spin on a very real kind of patriarchal pressure to set your own career aside to perpetuate your family. Compellingly fucked in all the worst ways.

There's a one-off beat about a nursing home for retired superheroes who are having difficulty controlling their powers in their old age, and it's portrayed as a fucking warzone; dementia-ridden psychics and pyrokinetics constantly inadvertently chewing through the staff and causing gigantic disasters. I think the age-based incontinence of superpeople- and the damage they can cause through no fault of their own- is a really underexplored area for superhero deconstructions, one adjacent to a lot of real-life problems faced by caregivers, and often problems that have no good answers. Near and dear to my heart, this particular problem.

The character of Supercollider is compelling down many of the same lines that Homelander is compelling; a "Superman" figure constructed by marketing-department fiat, with no identity of his own, difficult for the characters to sincerely hate in the end simply because it's impossible to determine where the marketing copy indoctrination stops and the hollow shell of a human begins, Surrounded by a meticulously constructed, rotating "Bat Family" extended cast that are his only semblance of human connection despite how immensely distant he is from them in every way that matters; the designated love interest with whom he's going through the motions, an utterly superfluous sidekick he's implied to be grotesquely co-dependent with to the point that his efforts to keep him safe in the field is a major driver of the collateral damage he does. Most of this we get third hand as Anna is mincing his support-system from the outside in, but the implied inside baseball is genuinely gloriously fucked, and I'd love to have seen some of it go down from the inside.

Anyway, 2.5 out of 5. Good ideas and character concepts that desperately needed more room to breathe, fun worldbuilding beats that desperately needed fleshing out to give those ideas and character concepts that room. Genuinely, this should have been a 1.7 million word web serial.

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

I mean...Isn't that part of what Worm was doing, actually? IE the idea of "what drives someone to do this kinda shit for a living?"(Answer: A vast cocphanoy of systemic failures leading people like the Undersiders to fall through the cracks). And, to be fair, that did turn around and have Taylor get in bed with and, eventually, BECOME that kinda mastermind villain.

I was wondering if youd read Hench yet.

I feel like the premise and the start were solid, and the main character's framing of superheroes through a strict environment cost-benefit analysis was interesting.

But it feels weird that in it's criticism of heroes it just sorta...gave villains a pass. Plus the incredibly loose world building, which early on was a strength in establishing the "you know how this works", vibe, but as the book progresses and the plot hinges increasingly on old interpersonal drama, it's suddenly a big gaping hole.

These are my broad criticisms of it, yeah.

Full disclosure- this is the book I was vagueing about a couple months ago, the one where I got annoyed because the back cover copy was pulling the "no ethical consumption under capitalism" card in relation to working as a henchman, in a way I found disingenuous given that many supervillains are on the face of it much, much worse for the world than the average tech start-up- particularly the kind of supervillain with a staff. But I also thought it would be disingenuous to bitch a book out purely on the grounds of its back-cover marketing department copy, so I bought it and read it. And unfortunately the final roundup on that tension appears to be that villains aren't that bad, are they? Maybe even kinda girlboss even!

Bulleted list under the cut!

The opening is strong, and gave me high hopes, specifically because of how it seemed to be aware of these tensions. Anna, our protagonist, opens as a temp in the employ of a sleazy c-list supervillain who's performative in his interest in his staff's wellbeing but doesn't hesitate to put his interns and temps in the meat-grinder for a leg-up; even a decisive loss to an A-list hero is a way to climb the ladder if you're a C-list villain. On the other side you've got superheroes who are horrifyingly cavalier with the lives of anyone they've deemed to be "on the other side." The protagonist is framed collateral damage in the grand idiot melodrama between two sides that don't give a shit about the lives of the little people in distinct but interlocking ways, and that's pretty compelling- particularly because at this point we're still coloring within the lines of the typical genre paradigm! That mutual self-centered apathy, the ways in which people get pigeonholed into specific roles in the melodrama that define and dehumanize them, drove seven seasons of The Venture Brothers, and now we get the tragicomic spin on that dynamic, we get a story told from the perspective of one of the henchmen or random civilians who get callously offed as part of a sight gag about how awful all of these people are!

That's not where it goes, though. @st-just has a pretty great writeup where they point out that for a story driven by the premise of heroes that cause immense collateral damage and use their institutional influence to dodge the consequences, the story is oddly incurious about the level of damage that Leviathan's enormous criminal organization does in the course of its operations; how many people have died because of all those superweapons he's handing out to lower-level villains? It's all oddly bloodless, and it feels like it keeps pulling back at the last second from the protagonist truly suffering moral injury- or from acknowledging that moral injury. Given how much of her plan involves waging psychological warfare on heroes until they snap publicly, there's a bit of an eric-andre-who-would-do-this vibe coming from then pinning that collateral purely on the heroes. I never got a good read on how self-aware the story is about the fact that Anna very, very quickly becomes attached to real tangible power in a way that makes her underdog framing feel extremely hollow; how quickly she becomes like her former boss, arraigning henchmen in the line of fire for the sake of the Grand Plan. One of those stories where it keeps gesturing but I can't tell the extent to which it intends to commit with a sequel.

The worldbuilding, as you mentioned, is an issue, because there's a failure to clarify quickly enough the larger systems that incentivize the heroes and villains- in fact, it often feels like the characters are operating from within different incentive systems, from different settings. The early sections of the book read like a "Silver-Age-taken-seriously" situation, similar to The Venture Brothers- the casual levels of temp-agency integration, card-carrying supervillain-as-tech-start-up boss, and of course, the myopic violence of free-agent cowboy cop vigilantes-slash-celebrities who never get called to account for it. Halfway through there's a pivot and now there's a Draft, capital-D, and it turns out that this has actually been a superhuman registration setting the whole time? "Supervillains" are actually just any superhumans who don't toe the line? "Superheroes" are screened for in middle schools and separated from their families? That's, uh, not completely incompatible with the aforementioned dynamic but it's a bit of a kludge! There are beats that are really great- Quantum relocating from New Zealand for a chance to partner with Supercollider only to end up subordinated for sexist-marketing reasons, the fucked nuclear family shit going on with Flamethrower and his kids and with the Ocean Four- that imply a level of individual career discretion on the part of the heroes that you'd need to do some work to square with whatever pressures are being exerted by the higher powers. It's actually pretty important who's calling the shots here and to what extent! If the climax is predicated on wanting to overthrow the system you need to make that system consistently visible and legible through the rest of the book!

As you mentioned, the book also pivots into there being a deep interpersonal drama that propels the back half; Leviathan turning out to actually be a former superhero who was dramatically wronged in a morally clear-cut way by Supercollider, who murdered his mentor for inside-baseball cape politics reasons and had this covered up. I've got really mixed feelings on this, because although the seeds of something fascinating are here it feels like one of the ways in which the book is hedging itself. Supercollider's callous but genre-standard disregard for hench lives isn't grounds enough to condemn him, no, he also has to have committed some off-duty murders as well, and he's a shitty boyfriend on top of that, he's a supervillain dressed like a superhero. We get Leviathan's justified grievance, and spectacular violence enacted on agents of an obviously evil system, but no up-close-and-personal villainy- he's functionally a hero with a villainous aesthetic (and a smattering of anecdotes about awful shit that he's done, but the story isn't interested in really making us feel it in the way that it is with Supercollider.) There's a beat that I really liked, where Quantum tells Anna that their respective villainous and heroic bosses care far more about beating each other than they do about the women in their lives or anyone else working under them. I think it was a grave misstep that this turned out to not be where the book went; making it so that there actually is a clear-cut good guy and bad guy in the Leviathan/Supercollider conflict, that they're fighting over something that matters, pushes the entire story dangerously close to what I term "Banal Hatswap" territory.

For more of a vibes-based criticism; and easily my most uncharitable; the entire story is written in a register of self-righteousness, and I have a hard time separating what's meant to be the biased viewpoint of the protagonist from what's meant to be the author Displaying The Correct Applause Lights for Twitter. You've got a protagonist who cracks a one-liner about supporting Penal Abolition.... who also puts out a hit on a guy who slowly dies horribly of sepsis as a result. A one-liner about a female superhero's "suspicious WASP" vibes, right before she emotionally manipulates said hero and arranges to have her kid kidnapped. "It's not my job to kinkshame, buuut," right before proceeding to leverage the embarrassing sexual proclivities of a superhero who's roundly characterized as boorish and misogynistic in conjunction with that. Bemoaning how Quantum, a strong heroine of color, is subordinated and put through the wringer by the patriarchal marketing machine, before acting as the major practical driver in the total collapse of said heroine's life. (This one is the one the protag displays the most self-awareness about, which might be related to the subtext that said superheroine is a potential love-interest.) Grandstanding about and predicating the whole plot on how all human life is valuable and villains don't deserve to receive life-changing brutality.... before being party to Quantum's graphically-detailed levels of payback against her shitty ex Supercollider, I mean we're talking like arc 14 Vicky Dallon levels of body horror and violation here, in borderline pornographic detail. All of this feels like either a very clever reproduction of how the very online know how to say all the right things to launder the fact that they constantly do all the wrong ones.... or it's just. an unreconstructed example of the thing. I can't tell, but the back-and-forth bothers me a lot. It's a situation where it becomes super fucking obvious how much Worm benefited from constant alternate-POV interludes; getting any of this from the head of someone other than Anna would go a long way for me.

Ultimately the book heavily depends on my sympathy for overeducated, temporarily embarrassed white collar computer touchers who throw in with evil worldwrecking conglomerates in exchange for dental. Unfortunately I think we all just axiomatically have it coming and superheroes would ideally pulverize way more of us so there's a level on which I was lost from the word go

Now, for the sake of a balanced assessment I'm going to go over a bunch of the ideas in the book that I did think worked really well:

As mentioned, the opening is extremely strong; the nightmare existence of living paycheck to paycheck as a temp, juiced up by the genre-elements, the slice-of-life hardscrabble existence of a woman at the bottom of the economic totem pole constantly having her attempts at a life worth living blown up by her proximity to this nonsense. Having a date break down because you have to drive your maimed henchman friend to the ER is a fucking amazing beat. Unfortunately the narrative moves away from this low-level approach very quickly, because a lot of what's going on with this thing is that it's a specific strain of power fantasy- a significantly-more-competently-executed version of a kind of villain-falls-for-his-hardworking-assistant Wattpad romance. That's not a pejorative or a criticism, just a kind of power fantasy that requires an end-of-act-one escape from the nightmarish mundanity in order to function. But I like the nightmarish mundanity! Bring back the nightmarish mundanity

The book has some great beats about the intersection of superheroics and women's issues. In a nod to the plight of superheroines from the silver-age and earlier, Quantum Entanglement is a superheroine with reality-warping levels of firepower who's constantly forced to downplay her own presence and individuality in order to help juice up the brand of her male partner Supercollider; in the climax it's revealed that this extended to subtly using telekinesis to create the false impression he's capable of independent flight, which is, implicitly, this settings version of Superman's transition to flight from really big jumps. There's a tendency for superheroines to get big power-bumps in conjunction with an arc about succumbing to a very gendered insanity- Malice and Avengers Disassembled being two prominent examples I can think of- and Quantum's eventual break from the monstrous Supercollider feels like commentary on this. In another one-and-done beat you have the heroine Abyssal, whose career is on the verge of being derailed by her third pregnancy; the catch is that she's a member of what's implied to be a family team (think New Wave or the FF) and her pregnancies are laced through with expectations and hopes that the kids will exhibit powers and be able to pad out the roster. By the end of the book she's mentioned to have been permanently benched, and another member of her team is killed "on-screen-" but that's alright! We've got her three kids waiting in the wings! A deeply grim superheroic spin on a very real kind of patriarchal pressure to set your own career aside to perpetuate your family. Compellingly fucked in all the worst ways.

There's a one-off beat about a nursing home for retired superheroes who are having difficulty controlling their powers in their old age, and it's portrayed as a fucking warzone; dementia-ridden psychics and pyrokinetics constantly inadvertently chewing through the staff and causing gigantic disasters. I think the age-based incontinence of superpeople- and the damage they can cause through no fault of their own- is a really underexplored area for superhero deconstructions, one adjacent to a lot of real-life problems faced by caregivers, and often problems that have no good answers. Near and dear to my heart, this particular problem.

The character of Supercollider is compelling down many of the same lines that Homelander is compelling; a "Superman" figure constructed by marketing-department fiat, with no identity of his own, difficult for the characters to sincerely hate in the end simply because it's impossible to determine where the marketing copy indoctrination stops and the hollow shell of a human begins, Surrounded by a meticulously constructed, rotating "Bat Family" extended cast that are his only semblance of human connection despite how immensely distant he is from them in every way that matters; the designated love interest with whom he's going through the motions, an utterly superfluous sidekick he's implied to be grotesquely co-dependent with to the point that his efforts to keep him safe in the field is a major driver of the collateral damage he does. Most of this we get third hand as Anna is mincing his support-system from the outside in, but the implied inside baseball is genuinely gloriously fucked, and I'd love to have seen some of it go down from the inside.

Anyway, 2.5 out of 5. Good ideas and character concepts that desperately needed more room to breathe, fun worldbuilding beats that desperately needed fleshing out to give those ideas and character concepts that room. Genuinely, this should have been a 1.7 million word web serial.

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, no offense to @Jcoggins, but...In what way is Sailor Moon NOT a superhero? Like, yes, magical girls are a different clade, but I would absolutely call her a superhero. Goku...Eh, maybe...His kid is, though.

Your post about Irredeemable have a tenth Doctor Pastiche has gotten me thinking about a ustice League Pastiche consisting of a Superman Pastiche and then various non-superhero media characters. You get a Doctor of course, and then toss in a Son Goku, etc. The issue with this is a dearth of female characters to include. Most of them are badass normal types which feels wrong. There is Sailor Moon and the Fairy Gomother, but two magic users feels redundant.

Sailor Moon is a good pick for the project you're describing but the fact that you had to fall back on the broad-archetype of the Fairy Godmother as your second pick I think is a really good demonstration of the problem you're gesturing at.

Lemme think. They'd have to be mass market to align with the rest of the gimmick, but also meteorically popular in the way that Superman and Sailor Moon are. I also assume we want to stay in the broad realm of action adventure protags rather than branching out into Agatha Christie territory, for example, and you've already ruled out "Badass normals..."

Buffy the Vampire Slayer strikes me as a decent pick for what you're talking about- a pastiche of her could conceivably cover a lot of 90s monster-of-the-week serialized fiction at once, and maybe even early stuff like Scooby-Doo if you taffy it out a little. A Pastiche of Xena, Warrior Princess might conceivably find a home here, although there'd be risks that she misidentified as the Wonder Woman pastiche you'd expect to fine in a typical league-analogous lineup; I'm also not sure how well she speciates away from Buffy's role as the 90s TV action heroine. My third pick would be a pastiche of Samus Aran- an emphasis on the power armor to justify her ability to keep pace, but with the broader stylings necessary to gesture at all of of the 80s cabinet arcade game protagonists at once. At four we've already outdone the DCAU Justice League lineup, so it's certainly possible to do worse.

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fair. It's possible this makes me a bad person, but it's just like...God, I get no story is fun to be in when you're in the middle of it (conflict is what drives stories, which means there has to be something shitty going on), so living in a fictional setting at any point pre-ending is gonna suck, and superhero stories (at least, Big Two ones) aren't designed for endings, so...They're called the AVENGERS, not the PREVengers for a reason, Order of the Stick had a villian whose whole plan centered this concept IE that the rules of being in a story mean that an evil empire must come into existence, and persist long enough that no one realistically thinks that they can be defeated, because that's what makes heroes opposing them dramatic. The bad guy gets to rule the roost for 30 years, the hero gets to win in the last 10 minutes. And it's like...Ugh. Maybe I need to stop empathizing with fictional people so much, maybe I need to develop that shell of detached cynical irony like all the other Gen Z people do, but...Well, my formative works were shows like Steven Universe, i'm nothing but sincerity, and I don't think...Ugh. I can't turn this off. And you're not my therapist, so i'll stop there, but...Christ.

Can I just admit...This might be a bit of a dick move, but, God, if reading your blog doesn't make it hard to write any genre fiction that appeals to that "wonder, adventure, triumph of the human spirit" stuff without thinking "yeah, but this is still a horrible place to live". I am kinda curious if any superhero works square that circle for you? Or is this a problem that only matters when you overemphasize with fictional people, like I do, and not when you think dismemberment is slapstick?

I will not lie, thinking dismemberment is a kind of slapstick helps a hell of a lot!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

No joke, the fact that Superman exists, that there is this universally beloved character whose central ethos is that when wielding power, one should take care to wield it with selflessness, compassion, kindness and justice, is, just...I am being dead serious when I say a world without Superman would be a VASTLY worse one. Even Alan Moore, the guy who invented superhero deconstruction, didn't try that shit with Superman, his few Superman stories are consistently about the character being noble and selfless. Even Garth Ennis and Mark Millar, patron saints of Edgy Superhero Deconstructions, don't hate Superman. And when you're the one superhero the guy who wrote the Boys likes, you know you're good.

superman is just such a perfect character concept. what if the nicest guy in the entire world could eat guns

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

superman is just such a perfect character concept. what if the nicest guy in the entire world could eat guns

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ya know, pursuant to the other reblog I made, I feel like a problem with deconstructions, superhero deconstructions, but also others, is that sometimes, when you deconstruct something, you just end up with…The original trope that that thing was responding to. I mentioned in that post the fact that "what if Martian Manhunter was evil" ends up just recreating the (itself extremely xenophobic by default) sci-fi trope of the shapeshifting alien hiding among us to destroy our great society. See also: Superman, who is framed as a repudiation of the Ring of Gyges, the idea that a man who is freed from physical constraints would be a monster as proof of either mankind's immortality or the socially-constructed nature of justice. Superman is a man who is free from every constraint our society places on people if he wants to be, but he restrains himself. His archenemy is, after all, a man who DEPENDS on the rules of our society to sustain himself, but also has no computations breaking them at every opportunity. Superman's greatest limit is the one he imposes on himself, and the intended message to an extent is that "if you are in a position of power, you should use it responsibly, and restraint yourself even, especially, if no one else will". Also, ya know, the twist on John Carter as an allegory for why immigrants are fine and good actually, ETC. And, in making parodies of Superman who are just assholes because power corrupted them, to an extent, you're just returning him to that original basic idea he was kinda meant to be in opposition to. I don't know if this makes sense, but, when deconstructing certain works, there's a tendency to end up going full circle. I think you mentioned this once in a post about Belos from the Owl House, about how a hypothetical "herofied" version of him would have to come from a vastly more conservative style of story, because that's the story he was meant to exist as a repudiation of. If he was a hero, he'd just be Doomslayer, and we already have Doomslayer. Does any of this make sense?

Superhero deconstructions for the Justice Leaguers who've managed to weasel out of it so far:

Wonder Woman: What's that? You're from a matriarchal, monarchal enclave of immortal, bronze-age warriors who worship the actual Greek gods? Who are real? And you came out the other side of that with values completely compatible with 21st-century progressive mores surrounding individualism, secularism, gender identity and governance? And you're completely accepting of trans people? That is so cool and marketable The Flash: A white midwestern cop has developed omnipresence. This is probably fine Green Lantern: Is the objectively-quantifiable and measurable quality of "Willpower" in the room with us right now. Also. who exactly signed off on this extraterrestrial paramilitary. Is this a cult Aquaman: A hereditary monarchy exerts military control over 70 percent of the world's surface. This is also probably fine

Martian Manhunter: God I wish Martian Manhunter had enough of a presence in the popular consciousness for there to be an intuitive attack surface

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fair, I guess. Honestly...I get the point, but I don't think these properties would actually be better for trying to account for this somehow. And, as for MM...I mean, the funny thing is, he's already a horror trope? "Shapeshifting telepathic alien who can turn invisible and walk through walls lives among us" was already an established Atomic Horror trope even at the time, and making the shapeshifting telepathic alien the hero was already kinda a subversion, I think.

Superhero deconstructions for the Justice Leaguers who've managed to weasel out of it so far:

Wonder Woman: What's that? You're from a matriarchal, monarchal enclave of immortal, bronze-age warriors who worship the actual Greek gods? Who are real? And you came out the other side of that with values completely compatible with 21st-century progressive mores surrounding individualism, secularism, gender identity and governance? And you're completely accepting of trans people? That is so cool and marketable The Flash: A white midwestern cop has developed omnipresence. This is probably fine Green Lantern: Is the objectively-quantifiable and measurable quality of "Willpower" in the room with us right now. Also. who exactly signed off on this extraterrestrial paramilitary. Is this a cult Aquaman: A hereditary monarchy exerts military control over 70 percent of the world's surface. This is also probably fine

Martian Manhunter: God I wish Martian Manhunter had enough of a presence in the popular consciousness for there to be an intuitive attack surface

505 notes

·

View notes