Text

The Plight of a Devout Zoroastrian Man from Yazd

The gentleman on the right in this photograph is my great great Grandfather, Behmard Noshirwan Yazdani (1880 - 1940), a devout Zoroastrian hailing from Yazd, Iran. Unfortunately, he suffered from the psychological and emotional distress associated with "#Islamotrauma," a term used to describe the trauma that individuals may experience due to discrimination, violence, and other traumatic events related to the abuse they have experienced from Islamist communities.

A little over a hundred years ago, my grandmother's family was forced to flee Iran due to persecution by Shi'ite Muslims. They were repeatedly harassed to convert to Islam. One day, Shi'ites broke into Behmard's home and threatened him with death, demanding that he convert to Islam. They told him they will kill him and kidnap his wife Kharman Gustasb Mubaraki (1892 - 1952) if he does not convert by the next day.

Faced with an impossible choice, with his life and his wife's at risk, Behmard and his wife fled to India to preserve their Zoroastrian faith and start a new life. Behmard's unwavering faith in Ahura Mazda was the right choice, as Zoroastrians in Iran faced brutal oppression.

The journey from Iran to India took Behmard and his wife three months, and they had to travel by foot during the night to avoid being captured. They did not want to leave their sacred homeland, but they had no choice. Behmard and his wife were captured by a Muslim man on their journey from Iran to India. The man was going to turn them into authorities but Behmard and his wife began praying manthravani from the Avesta. The man suddenly had a change of heart and let them go. Upon arrival in India, they started a new life and remained true to their Zoroastrian faith.

Behmard's unwavering commitment to his Zoroastrian faith was a triumph in the face of adversity. It was a time when Zoroastrians in Iran were subjected to severe oppression, which led to a dwindling population. Only 7,711 Zoroastrians remained in Kerman, Yazd, and Tehran combined when the Parsi philanthropist Maneckji Hataria visited Iran in the 19th century. However, today, the younger generation is returning to the Zoroastrian religion in large numbers, signaling the beginnings of a true Zoroastrian renaissance.

As a descendant of Behmard and other Zoroastrians who have endured more than a millennia of persecution, I am forever grateful to all the Zoroastrians who endured centuries of pogroms and persecution to save the religion from extinction. While we lost our country, we never lost our faith in God. One day soon, we will regain our Iran, and the malevolent mullahs who inflicted such pain on our community will retreat to the depths of hell where they belong. #IranRevoIution #Zoroastrianism #no_to_islamic_republic #FreedomForIran

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Purpose of Life

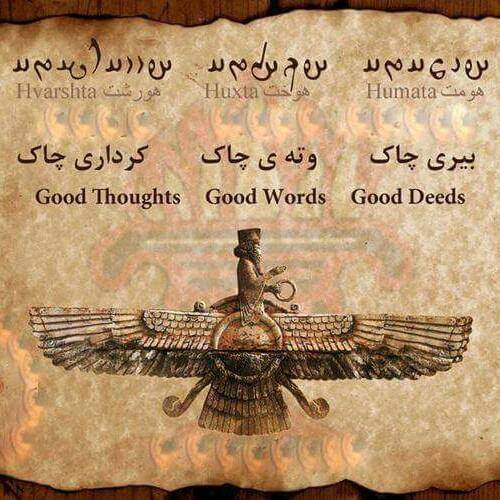

The Zoroastrian religion posits that the universe is currently undergoing a cosmic conflict between the forces of light and darkness. As humans, we are the centerpiece in this battle between good and evil, and we have been endowed with free will to choose which side to align with.

Those who opt for the path of virtue by manifesting good thoughts, words, and deeds, serve Ahura Mazda, the supreme God of light, wisdom, and love. Consequently, they are destined to experience a positive and joyous existence in the afterlife. On the other hand, those who perpetuate evil through their thoughts, words, and actions contribute to the forces of darkness in the world, thus causing human suffering. The latter serve the evil spirit Ahriman and will ultimately face an afterlife characterized by misery and gloom.

This dualistic worldview is justified by the observation of good and evil in the world in various forms, such as order and chaos, life and death, justice and injustice, knowledge and ignorance, and war and peace. This struggle is ongoing and can be seen in various conflicts throughout the world such as those between Ukraine and Russia, Israel and Palestine, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and inside Iran between the genocidal Islamist Khomeinists and the freedom-loving children of King Cyrus.

The question of how a good God can exist when there is so much suffering in the world is a common source of doubt for many who lack faith in a higher power. When you see innocent children being killed in Ukraine and schoolgirls being gassed with chemical weapons in Iran, it makes you question why. This dilemna is known as Theodicy, and Zoroastrianism is the only religion which offers a satisfactory solution from a philosophical standpoint. The religion does not view God as the creator of evil but rather sees suffering as a result of wrongful human choices resulting from the influence of the evil spirit. In this way, Zoroastrianism emphasizes individual responsibility and human agency in the struggle between good and evil.

Ahura Mazda is not the creator of evil. Instead, it is Ahriman who has corrupted the universe. Ahriman is not a fallen angel, but rather a completely separate metaphysical entity who is hostile to God. Zoroastrianism sees evil and suffering as a result of humans who chose to align themselves with Ahriman. In this way, the religion provides a solution to the problem of Theodicy by emphasizing the role of human agency and the importance of individual responsibility in the cosmic struggle between good and evil. Those religions which expound the belief in an all-powerful deity who created the world and the evil within it are illogical and must be abandoned for the sake of humanity.

The purpose of life in Zoroastrianism is to live a happy and fulfilled life - but people cannot be happy when evil is causing them harm, thus Zoroastrians have a religious duty to fight evil through "Good Thoughts, Good Words, and Good Deeds". The Zoroastrian duty is to understand and perform the will of the creator, which is known through the good religion of Zarathushtra.

In conclusion, Zoroastrianism presents a compelling worldview that centers on a cosmic struggle between the forces of light and darkness, emphasizes individual responsibility in the fight against evil, and offers a unique solution to the problem of theodicy.

#iranrevolution

#Zoroastrianism

#womanlifefreedom

#theodicy

#goodandevil

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theodicy and Zoroastrianism

By Justin Haubrich

Theodicy is the problem of evil, which asks how it is possible for an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good God to allow evil and suffering in the world. Zoroastrianism provides a unique solution to this problem through its belief in the cosmic struggle between good and evil.

According to Zoroastrianism, there are two main forces in the universe: Ahura Mazda, the God of good and light, and Angra Mainyu, the spirit of evil and darkness. These two forces are engaged in a perpetual battle, and human beings are caught in the middle of this struggle.

Zoroastrianism teaches that human beings have free will and are responsible for their actions. It is through their choices that they align themselves with either the forces of good or the forces of evil. When individuals choose to do good, they help to advance the cause of Ahura Mazda and contribute to the defeat of Angra Mainyu. Conversely, when individuals choose to do evil, they contribute to the victory of Angra Mainyu and the perpetuation of suffering in the world.

Thus, Zoroastrianism sees evil and suffering as a result of human choices, rather than the fault of a distant or uninvolved deity. In this way, the religion provides a solution to the problem of Theodicy by emphasizing the role of human agency and the importance of individual responsibility in the cosmic struggle between good and evil.

0 notes

Text

The Yazatas

The Zoroastrian religion is home to many powerful beings called Yazatas, which translate to "worshipful ones" or "worthy of worship." These Yazatas are believed to be divine sparks that originate from Ahura Mazda, embodying the different qualities and attributes of the divine.

Three Yazatas, Sraosha, Rashnu, and Mithra, form a critical triad in the Zoroastrian religion, responsible for maintaining justice and ensuring that every person receives the appropriate consequences for their actions. Sraosha symbolizes God's all-hearing ears, Mithra as God's all-seeing eyes, and Rashnu as the judge who represents God's justice and decides the fate of souls. Their abilities to perceive everything leave nothing hidden from them, and they ensure that perfect justice is guaranteed in the afterlife.

Apart from their judicial duties, they also perform other critical roles. Sraosha is the source of revelation and serves as a two-way channel between God and mankind. He acts not only as God's ears but also a source of intuition for all righteous people, who share a spiritual connection with Ahura Mazda. Mithra, on the other hand, serves as the Yazata who upholds the sanctity of contracts and is a staunch adversary of falsehood. Mithra ensures that those who break their promises face justice.

The Zoroastrian religion is steeped in rich culture and beliefs, with the Yazatas being just one of the many fascinating aspects. These powerful entities serve as an essential link between humanity and the divine, guiding us towards righteousness and justice. As such, they remain an integral part of the Zoroastrian faith, embodying the religion's core principles of truth, justice, and righteousness.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good and Evil

Mardan-Farrukh was a prominent Zoroastrian theologian and philosopher who lived in the 9th century CE. He is best known for his work, the Shikand-gumanig Vizar, which provides a comprehensive account of Zoroastrian theology, ethics, and practice. One of the key themes of this work is the problem of evil and how Zoroastrianism deals with it.

According to Mardan-Farrukh, the Zoroastrian worldview is based on the concept of dualism, which posits that the universe is the result of an eternal struggle between two opposing forces: good and evil. Ohrmazd, the wise and powerful creator, is pitted against his adversary, Ahriman, the embodiment of evil. Mardan-Farrukh argues that this dualistic worldview is justified by the universal presence of good and evil in the world, which can be observed in the various pairs of opposites such as light and dark, life and death, justice and disorder, and so on.

However, Mardan-Farrukh is quick to emphasize that Ohrmazd is not the creator of evil. Instead, it is Ahriman who has corrupted the world and caused suffering and chaos. The author is emphatic that God is good, and he refutes the idea that good and evil can have originated from the same source. According to Mardan-Farrukh, the two are entirely separate from each other, and they entertain perpetual antagonism towards each other.

Mardan-Farrukh further argues that if Ohrmazd and Ahriman had created the world together or in cooperation, then Ohrmazd would be complicit in the harm and evil that arise. Instead, Ohrmazd's creation was motivated by his desire to repel and ward off Ahriman and defeat the evil he intends. The good creation, according to Mardan-Farrukh, acts as a trap to capture Ahriman and neutralize his evil.

The ultimate result of this cosmic struggle, according to Mardan-Farrukh, will be the triumph of good. He notes that Ahriman is aggressive, rash, and ignorant, while Ohrmazd is thoughtful and prudent. The entire cosmic process from the original creation by Ohrmazd and the attack by Ahriman until the triumphant rehabilitation of the universe. Humankind, along with the Amesha Spenta, plays a vital role in the defeat of Druj (the Lie) and the victory of Asha (the Truth).

Mardan-Farrukh emphasizes that the duty of the creature is to understand and perform the will of the creator and to abstain from what is disliked by him. This is essential to preserving the soul. He believes that the will of the creator is known through his religion, which manifests the grandeur and value of the sacred being as well as his compassion and mercy.

In conclusion, Mardan-Farrukh's Shikand-gumanig Vizar provides a comprehensive account of Zoroastrian theology and its response to the problem of evil. He argues that the universe is the result of a cosmic struggle between good and evil, with Ohrmazd, the wise and powerful creator, ultimately triumphing over Ahriman, the embodiment of evil. The Zoroastrian duty is to understand and perform the will of the creator, which is known through the good religion of Zarathushtra.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Zoroastrianism and Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organization that emerged in the 17th century in Europe. The connection between Zoroastrianism and Freemasonry is a subject of debate among scholars. However, it is clear that Zoroastrianism influenced the development of some of the core beliefs and practices of Freemasonry.

One of the most significant influences of Zoroastrianism on Freemasonry is the concept of dualism. Zoroastrianism is a dualistic religion that believes in two opposing forces of good and evil, represented by the God Ahura Mazda and the evil spirit Angra Mainyu, respectively. Freemasonry also embraces dualism, as it teaches its members to strive for the triumph of good over evil.

Furthermore, Zoroastrianism also influenced the symbolic structure of Freemasonry. The religion's emphasis on fire as a symbol of purity and illumination can be seen in the use of candles and torches in Masonic rituals. Similarly, the Zoroastrian concept of the path of righteousness and the need for constant self-improvement can be seen in the Masonic emphasis on moral and spiritual growth.

The concept of the "Four Elements" is another example of the influence of Zoroastrianism on Freemasonry. In Zoroastrianism, the four elements (fire, water, earth, and air) are believed to represent the most sacred elements of the universe. Similarly, in Freemasonry, the four elements are used as symbols to represent different aspects of the organization's teachings.

The use of symbols is one of the most significant similarities between Zoroastrianism and Freemasonry. Both organizations use symbols to represent complex ideas and concepts, and both use symbols to convey moral and ethical teachings.

Another notable influence of Zoroastrianism on Freemasonry is the concept of truth. Zoroastrianism emphasizes the importance of truth, honesty, and justice, and these values are also central to Freemasonry. Masonic lodges are known for their strict adherence to ethical and moral standards, and members are expected to be honest and trustworthy.

Additionally, the Zoroastrian concept of the soul's journey and the afterlife is reflected in some Masonic teachings. Freemasonry teaches that a person's actions in life determine their fate in the afterlife, and that the pursuit of moral and spiritual enlightenment is essential to a fulfilling life and a positive afterlife.

In conclusion, the influence of Zoroastrianism on Freemasonry is evident in many aspects of the organization's beliefs and practices. From the emphasis on dualism and the symbolism of fire to the focus on truth, morality, and the afterlife, Zoroastrianism has played a significant role in shaping the philosophy and values of Freemasonry. While the exact nature and extent of this influence may be subject to debate, there is no doubt that Zoroastrianism has left a lasting impact on one of the world's most influential fraternal organizations.

0 notes

Text

Mardun-Farrukh's Critique of the Abrahamic Faiths

The 9th-century Iranian philosopher Mardan-Farrukh criticized the monotheistic religions of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, focusing on their creation stories and theodicies. He believed that the belief in an all-powerful deity who created the world and the evil within it was illogical and criticized the texts of each religion for supporting this belief. Mardan-Farrukh was especially critical of the type of monotheism practiced by Islam, which he believed was responsible for the pressure on the Zoroastrian community in Iran. He believed that the Zoroastrians were being ground down into a small, deprived, and harassed minority, lacking all privileges or consideration.

Mardan-Farrukh found fault with the Jewish texts in particular, challenging the creation story of the Bible. He questioned why the delay of six days was necessary if Jehovah only needed to command, stating that the existence of that delay was ill-seeming. Mardan-Farrukh also noted that Jehovah made Adam and Eve and therefore made their inclinations. He criticized Jehovah's will and command as inconsistent and unadapted, and thus believed that the Biblical god was an opponent and adversary to his own will.

Mardan-Farrukh believed that the curse of Jehovah on Adam affected everyone and reached unlawfully over people of every kind at various periods. In contrast, the Zoroastrian God, Ohrmazd, was seen as a wise being whose actions were wholly just and accessible to reason. Mardan-Farrukh did not spare Christianity in his criticisms, noting that his unfavorable remarks on the type of monotheism held by Judaism and Islam would apply to Christianity as well. During the prior Sasanid era, there was often heated polemics between Zoroastrian priests and prelates of the rival faith of Christianity.

Mardan-Farrukh believed that humans had little knowledge and little wisdom but still did not let noxious creatures in among their own young ones. He questioned why the merciful sacred being would allow demons into the world, especially since there were no opponents or adversaries. He also questioned why Jehovah did not fortify the garden where he placed Adam to prevent Satan from getting in.

In conclusion, Mardan-Farrukh's criticisms of Abrahamic monotheism were focused on the illogical nature of the belief in an all-powerful deity who created the world and the evil within it. He believed that the texts of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity supported this belief and were thus flawed. He also questioned the stories of creation and theodicy found in these texts, stating that they were inconsistent and unadapted. Mardan-Farrukh's criticisms of the type of monotheism practiced by Islam were especially harsh due to the pressure on the Zoroastrian community in Iran. He believed that this community was being ground down into a small, deprived, and harassed minority, lacking all privileges or consideration.

#Mardun Farrukh#Polemics#Philosophy#Abrahamic faiths#Zoroastrianism#9th Century#Monotheism#Judaism#Islam#Christianity#Theodicy

0 notes

Text

The Three Magi and Zoroastrianism

The story of the three magi, or wise men, is a well-known tale from the Book of Matthew that has its roots in the ancient religion of Zoroastrianism. According to this story, the magi, who are believed to have come from the East, brought gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to the newborn baby Jesus in Bethlehem. Their visit is often considered a significant event in the story of Jesus' birth and is celebrated by Christians around the world.

The connection between Zoroastrianism and the magi lies in the fact that Zoroastrianism was the predominant religion of Iran at the time of Jesus' birth. The magi were likely Zoroastrian priests or scholars who were well-versed in the religion's teachings and prophecies. In fact, Zoroastrianism has its own prophecy of a savior who would be born of a virgin and would bring peace and prosperity to the world.

The magi's gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh also have significant meaning in Zoroastrianism. Gold represents royalty and power, while frankincense and myrrh are both used in Zoroastrian religious ceremonies as a symbol of prayer and purification. These gifts were likely chosen by the magi to honor the divine nature of the baby Jesus and to acknowledge his role as a spiritual leader.

The magi's visit to Jesus is considered by many to be a symbol of the connection between Zoroastrianism and Christianity. The fact that the magi were able to recognize the significance of Jesus' birth and travel such a great distance to honor him speaks to the idea that there is a common thread of spirituality and divine revelation that runs through many of the world's religions.

In addition to their role in the story of Jesus' birth, the magi have also become important figures in Zoroastrianism. In Irann mythology, the magi are known as the "three holy men" and are revered for their wisdom and insight. Their visit to Jesus is seen as a symbol of the universal nature of spiritual enlightenment and the idea that truth can be found in many different places.

Overall, the story of the three magi is a powerful reminder of the connections that exist between different cultures and religions. By recognizing and honoring the wisdom of other traditions, we can deepen our own understanding of spirituality and the divine. The magi's journey to Bethlehem is a testament to the power of faith and the idea that even the smallest acts of kindness and reverence can have a profound impact on the world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Refutation of an anti-Zoroastrian Evangelical

A few years ago I was browsing Twitter when I stumbled upon a thread written by a pseudo-intellectual evangelical Christian apologist from Texas by the name of Sir Travis Jackson. In this thread, the evangelical was attacking Zoroastrianism, my ancestral Iranian religion.

As an advocate and defender of the ancient Zoroastrian faith, I didn't hesitate to get into a theological debate with him.

During the debate, I so thoroughly wrecked him, that he deleted the thread and retreated from Twitter to Tumblr so he could continue the debate without me.

He was seething so hard that he had to go on to Tumblr and write a 3,000 word barely coherent polemical rant to refute the Zoroastrian influence on Judaism and Christianity, where he mentions me by name in the first few paragraphs. I didn't even know about it until today. You can read it here: https://www.tumblr.com/sirtravisjacksonoftexas/627024203052433408/did-judaism-and-christianity-borrow-from

In order for this spasticated brainwashed evangelical to cope with the insecurity that he was feeling towards his beliefs, he had to jump through some very impressive mental gymnastics to refute my views. He should get a gold medal for that.

I have lived in Oklahoma my whole life so I have dealt with my fair share of Iranophobic anti-Zoroastrian evangelicals like him in the past. The evangelical christians are well-known for their bigotry, ignorance, judgemental intolerance, hostility, political extremism, incoherency, hypocrisy, and insular close-mindedness towards people of other faiths and ways of life. I have experienced it time and time again. It is a reputation they have thoroughly earned.

The Zoroastrian community, on the other hand, has earned a reputation of being honest, egalitarian, philanthropic, kind, joyous, charitable, industrious, entreprenuerial, and resilient in the face of adversity. The Zoroastrians have maintained their faith and tradition for thousands of years, surviving countless invasions and genocides from various bloodthirsty armies, and have made contributions to the fields of philosophy, science, literature, art, architecture, and jurisprudence. The ancient Zoroastrians literally invented Human Rights under King Cyrus. They are also well known for their rich cultural traditions such as Nowruz and their interfaith cooperation and positive relations with other religious communities. They also gave the world Freddy Mercury.

If you don't believe me, just ask the Hindus what they think of us. They love us. And we love them.

Anyways, here is my refutation to Sir Travis Jackson's refutation:

The argument presented in Travis Jackson's article against the fact that Judaism and Christianity borrowed from Zoroastrianism is weak and lacks evidence. The article argues that the Wise Men or Magi who visited Jesus were astrologers and not Zoroastrian priests. However, the term "Magi" was used specifically to describe Zoroastrian priests, and there is evidence that they were known to travel beyond Persia to conduct religious ceremonies.

Sir Travis Jackson argues that the Syrian Infancy Gospel is too late to be used as evidence that Zoroaster predicted Christ's birth. However, the fact that the text was written in the 6th century AD does not necessarily mean that it did not draw on earlier traditions. Moreover, the author ignores the fact that there are other sources that suggest a connection between Zoroastrianism and Christianity, such as the Acts of Thomas and the Clementine Recognitions.

Travis argues that the Jews did not borrow the concepts of heaven and hell, angels and demons, the devil, and the final resurrection from Zoroastrianism because these concepts were already present in pre-Zoroastrian Iranian religion. However, this argument overlooks the fact that Zoroastrianism played a key role in shaping the development of these concepts in Judaism and Christianity. For example, the Jewish concept of Satan was influenced by the Zoroastrian figure of Angra Mainyu, and the idea of a final judgment and resurrection was taken from the Zoroastrian concept known as Fareshokereti.

While it is true that many cultures and religions had the idea of an afterlife, including a realm of demons or evil spirits, the concept of Heaven and Hell as a binary choice for souls after death is unique to Zoroastrianism. This is not just a general idea of an afterlife, but a specific concept that has similarities to the Christian and Jewish belief in an eternal reward or punishment. Additionally, there is evidence that Jewish and Christian ideas of Heaven and Hell developed after contact with Zoroastrianism, particularly during the Babylonian exile of the Jews in the 6th century BCE, where they would have been exposed to Zoroastrianism.

While it is true that other cultures had similar concepts of lesser spirits or gods, the idea of angels and demons as specific categories with distinct roles is again unique to Zoroastrianism. In Zoroastrianism, there are good and evil spirits that are in constant conflict, which is similar to the Christian and Jewish ideas of angels and demons. While there may be similarities to other cultures, the specific concepts of angels and demons in Christianity and Judaism are likely influenced by Zoroastrianism.

While it is true that other cultures had similar concepts of a devil or evil deity, the specific concept of a single entity that is in constant conflict with God is again unique to Zoroastrianism. The concept of a fallen angel or Satan in Christianity and Judaism is likely influenced by Zoroastrianism, particularly given the similarities in the descriptions of the Christian devil Satan and the Zoroastrian devil Angra Mainyu.

Finally, the article argues that the concept of heaven and hell, angels and demons, the devil, and the final resurrection were not borrowed from Zoroastrianism because the ancient Iranians worshipped gods called "Daevas" that were later considered demons by Zoroaster. However, this argument does not negate the numerous historical occurences of Zoroastrianism making contact and exerting influence on Jewish and Christian beliefs through the Persian Empire, as there are similarities to be found between their religious texts.

Overall, while the article attempts to refute the claim that Judaism and Christianity borrowed from Zoroastrianism, it fails to provide convincing evidence to support its argument.

6 notes

·

View notes