"England?"... "There the men are as mad as he is." - Life within the British Arts industry.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

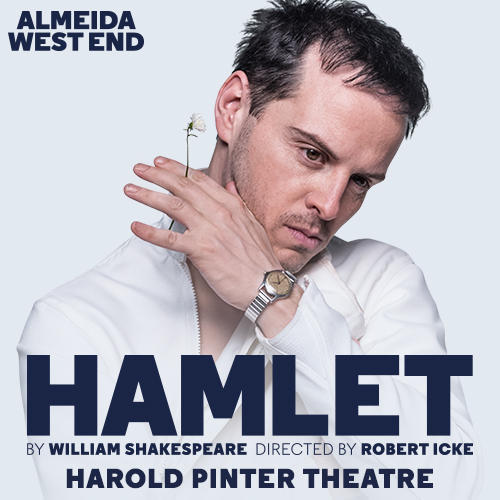

‘Hamlet’ starring Andrew Scott ⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️ Review

After a desperate struggle with Southern Rail over cancelled trains and the speediest speed walk down the banks of the River Thames ever, I made it to the Harold Pinter Theatre in time see Robert Icke’s production of Shakespeare’s infamous revenge tragedy, ‘Hamlet’.

The eponymous ‘Hamlet’ in this production, as with any other, is a Prince, heir to the throne of Denmark, who, not long having lost his father, has to watch his mother marry with his uncle, Claudius. Suffering with suicidal depression, the prince is in the depths of despair to discover, by his father’s ghost, that Claudius had committed murder in order to gain the crown. Hamlet swears to “remember” him and sets out on a rather procrastinated revenge mission. He assumes madness to allow himself to investigate his uncle’s culpability without arousing suspicion. The act typically leads the character into true megalomania; this take, however, explores the complex nature of our mentality and questions whether Hamlet’s behaviour is founded on a deeper fragility, leading upcoming Sherlock-star, Andrew Scott, to portray the Prince, not as outrightly “mad” but instead, mentally ill. - A necessity, I feel, when placing the narrative in a 21st Century context.

Icke’s production was evidently influenced by one of his previous projects in which he staged Orwell’s 1984. The theme of constant supervision is prevalent within this modern adaption of ‘Hamlet’. Hamlet’s paranoia is often attributed solely to his madness, “his wits disease”, but Icke’s introduction of technological espionage, in the form of hidden microphones and extensive video surveillance, allows the character’s otherwise unfounded schizophrenic behaviour to become rooted in something quite real. The decision was refreshing and was uniquely sympathetic to the Danish Prince.

The theme of surveillance was accentuated further in the utilisation of a live feed camera. In the picture below, the cast were sat with us in the audience.

A camera followed them as they entered the auditorium, projecting their every reaction to multiple screens around the space. This coupled with the pre-prepared BBC-style news footage shown at various intervals gave a verisimilitude to the situation and promoted a strong sense of entrapment, making the castle of Elsinore, and Denmark, seem very much like the “prison” of which Hamlet speaks.

The set, in it’s three distinct levels of division, exemplifies the sensation of always being watched whilst also effectuating the confines of Hamlet’s situation. Hildegard Bechtler’s stark, geometric design offers a visual interpretation of the Prince’s mind-set. It portrays well the emptiness experienced by the youth of the court following the loss of a parental figure; the greys, blues and off-whites evoking the isolating insensitivity we feel when we are confronted with death. The quasi-clinical approach to Castle’s decor offers us to consider how Royalty has come to resemble the Institution, whilst the archaic winding passages viewed on the large, central screens depict the maze within Hamlet’s inner mind.

The lighting, whilst I feel did not always convey severity or intensity of a situation, particularly in the speeches, it was, more often than not, empathetic to the characters’ moods. However, the incorporation of the House lights into the design (to change our mood and attentions) was an old-trick I sorely miss and was glad to experience once more.

Music in this production was almost perpetual. I think this was a mistake. Bob Dylan seemed to take centre stage in this production and, for me, the jovial key of each song broke the atmosphere the actors had spent 20 minutes trying to claw out of a scene. The music worked fine at the beginning, helping in creating a golden aura in which Angus Wright and Juliet Stevenson danced convincingly in love together as the newly married King and Queen. But as the piece progressed and the mood shifted, the music did not shift with it and it severed the ties the piece, making it unclear how we’re supposed to feel towards this story. - Anything thing at all? I might ask.

So, how were the actors? On this rare occasion, it was the actors who let this production down for me. Had I been judging this piece solely on the actors’ performances, I could just about unwittingly award two stars.

The piece started strong. It was fast, intense, allusive; we definitely got the impression that something “rotten”, dark, was going on in the state of Denmark. I knew from the first two minutes, we were in for an absolute crystalline treasure of a production. However, the moment scene two begun the pace seemed lag; everyone was operating at a different rhythm. By the time Andrew Scott took a purposeful step forward to begin his first soliloquy, only to fluff his lines, the driving beat at which the play had been leaping forward completely dissipated and stayed in an uneven see-saw motion until the company finally managed to pick it up three-hours later in the final act. What is most prominent in my mind, however, is the tribulation Peter Wight inflicted on his company members. The actor playing Polonius appeared to not pick up his cue, twice, during in the course of the show, staring, transfixed at a random point on the floor, for far longer than was comfortable. It went from a pause to a comedic silence to an awkward silence, going on and on until Wight had sat there for so long the actor opposite him had become fidgety. I began to seriously worry he’d had a stoke or something. This happened again later on in the following act, though this time he did not jolt back into place and so the Stage Manager had to walk on and call a premature interval. If this was an intentional direction of Icke’s it certainly didn’t look that way and certainly didn’t work.

I’m not unsympathetic, I have been the performer, I know what it’s like in these situations and it was evident enough that this was a bad show for them. Whenever they tried to get the piece off of it’s knees, something else went wrong, such as a curtain falling down, and they ended up knocking the play to the floor rather than getting on it’s feet. I condemn because they let their blunders hinder the running of the show. Being a writer/director, I am sensitive to atmosphere and pace, but even my companion, unfamiliar with theatre and Shakespeare commented that it everything felt “off piste”.

Icke has criticised how actors these days have “poisoned” Shakespeare by over-acting, something I agree with though do not often sees at the higher tiers of the profession. Despite this comment, Icke’s production felt decidedly staged; it was as if the company had not come to agreement of whether or not they were acknowledging the audience, creating uncomplimentary rivalry between the cast and Hamlet.

This indecision I noticed in most keenly in Andrew Scott’s performance. It seems under-acting also poisons Shakespeare. The jewels of Shakespeare’s masterpiece, the intensely philosophical soliloquies, when normally drawing me avidly in left me shaking me head in frustration, and, at times, switched off to such a degree I took up looking at the faces of the audience instead. There was little, to no, variation in tone or intonation and it was a relief when the star began putting some life back into his words. The pauses, whilst sometimes portrayed Hamlet’s vast superior intelligence, mostly left me wanting to screech in agony as their grandeur and beauty evaporated into absent minded chatter. Perhaps the modern setting, or current level of existential inquest, in which the words were being spoken was part to blame for the loss of soaring intellect, but there is no denying, something was distinctly wrong with Andrew Scott’s interpretation.

What drew me into seeing this adaption was the opportunity to see Scott playing with Theatre’s most intensely mad, passionate character. We all know the actor, from his time opposite Benedict Cumberbatch playing James Moriarty in hit TV-Drama Sherlock, is astoundingly good at playing psychotic intelligence. (He got a BAFTA for it, for Christ sake!) But I was disappointed to find that he did not experiment with the character that much at all, it fact, it felt rather un-revolutionary; almost careless. I commend Scott for wanting to approach Hamlet’s “madness” as mental illness. It is element I have wanted to see realised for a very long time but unfortunately what “affliction” of the Prince’s the Irish actor was primarily portraying was uncertain and consequently the portrayal of any sort of illness was lost all together and he, for the most part, came off plainly mad. There seemed to be reactions signifying a PTSD, other quirks suggested an acute situational anxiety; all the while the significant emotions attached to the play, such as depression and betrayal appeared almost non-existent. There were moments, particularly when the character was in the company of Ophelia, and then later on in the Closet Scene, when Scott played the character’s anguish superbly. He captured the raw, almost child-like need Hamlet has for his father in a way I have seen no-one do yet. Disappointingly these attentive, intricate moments were few and far between.

Jessica Brown Findlay and Luke Thompson, as Ophelia and Laertes, on the other hand did a thoroughly excellent job at isolating their characters’ distress. I found it thoroughly engaging that both brother and sister, manifested the same inclination towards self-harm when dealing with intense grief, hitting themselves over and over in a moment of almost physical Tourette’s. For the first time over the course of the whole show I was able to ask questions outside of the play: What had their childhood been like? Did they suffer a trauma together previously?

Whilst the principals, most notable, Angus Wright’s Claudius, seemed wholly unmotivated in their intentions, it was the secondary characters that gave the most convincing performances of the cast. The ever present security guards appeared more genuinely concerned for the Young Prince’s mentality than his mother, Gertrude. The fierce Juliet Stevenson appeared to look wholly deflated by the production when playing the Queen of Denmark. Joshua Higgott, attentively embodying friend Horatio, contrastingly managed to look fully engaged within the poorly upheld world. The Player King and Queen, as played by David Rintoul and Marty Cruickshank, were wonderfully caring and expressive characters and I am glad to say that Madeline Appiah as Guildenstern, and Calum Findlay as Rosencrantz, were some of the most three-dimensional characters present, meaning that the poor, fated characters were not mere plot devices.

Overall, the production was distinctly unique when compared against the past decade’s interpretations. It was refreshingly fast paced for a nigh-on four hour show but was it inconsistent. The show lacked a drive and passion which, in the end, left it feeling lifeless and looking dull. Scott’s performance, whilst littered with moment of comedic genius that made me laugh out loud, was largely unbelievable, mostly in the fact that he himself did not seem to believe in the situation his character was in. Potentially, he was overwhelmed by all there was to covey of the character. Had I been sitting on the stage, I might have seen some more intricacy in his work, the actor being more accustom to playing to a camera.

Andrew Scott is a stunningly intense, intelligent actor, touching upon the sweetness of the “sweet prince” but, unfortunately, this time, he seemed to miss the mark.

C Watson-Holmes. July 2nd, 2017.

#hamlet#andrew scott#shakespeare#william shakespeare#sweet prince#william shakespeare#irish#bafta#bafta winning#actor#acting#review#show review#hamlet review#harold pinter theatre#almeida theatre#almeida hamlet#andrew scott hamlet#theatre review#robert icke#director#benedict cumberbtch#sherlock#bbc sherlock#james moriarty#moriarty#madeline appiah#jessica brown findlay#luke thompson#angus wright

4 notes

·

View notes