professional human pillow, romanticist and sigma kincertified white-haired man kisserthis is mostly a BSD blog but i'm silly and goofy so...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

paratise (pt. 1)

#ALWAYS reblog paratise#paratise the song ever#alien stage#alnst#alnst fanart#paratise#alnst paratise#alnst ivan#alien stage fanart

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mizi and Ivan are truly the unreliable narrator duo of all time

On one hand, we have Mizi claiming "I did not love her enough"

On the other hand, we have Ivan claiming "He did not love me in the slightest"

And both of them were so wrong

#mizivan are like my favourite little guys#theyre literally so similar but nobody UNDERSTANDS#poor mizi#poor ivan#i love all of them#the anakt 4 deserved BETTER THAN THIS#THEY WERE JUST KIDS#i screm and cry#alien stage#alnst#alnst mizisua#alnst ivantill#alnst mizi#alnst sua#alnst till#alnst ivan

6K notes

·

View notes

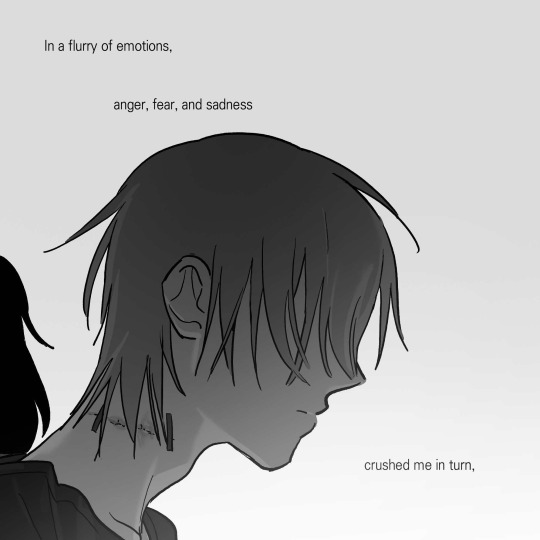

Text

eepers

#AND WHY THEY OEPY 😂#i love baby ivantill i love them so much its unfair...........#shhhhhh shut u[p theyre sleeping#alnst#alien stage#alnst fanart#ivantill#alnst ivantill#alnst ivan#alnst till

481 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two halves of one

#RIMLAINE. RIMLAIIIIIIIINE#RIMLAINE RIMLAINE RIMLAINE#bsd#bsd fanart#bsd verlaine#bsd rimbaud#bungou stray dogs#bsd stormbringer#bsd rimlaine#rimlaine

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

my savior

#i love lesbians bro#<3#mizisua#alnst mizisua#alnst fanart#mizisua fanart#alnst mizi#alnst sua#alien stage

595 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was missing them <3

#put some notes on this bad boy yall#look at that KICK oh lawd fyodor get it girlfriend#good for them. love is love#bsd#bsd fanart#fyolai#bsd fyodor#bsd nikolai

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

an inevitable demise [½]

#pov you picked up moriarty vol 1#look at his hair......... <33333#bsd#bsd dazai#bsd fanart#bungou stray dogs

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Reblog if you want your followers to anonymously ask you one thing they want to know about you.

707K notes

·

View notes

Text

My fragile god, fading fast.

#this is unrelated but HER DRESS IS DRAWN SO PRETTY OMGMGMGMMMMMM#sua is so beautiful we should all stare at sua more#they don't say i'm just like mizi for nothing#she is so gorjus omg#alien stage#alnst#alnst sua#alien stage sua#alnst fanart#mizisua

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thai fansign event with Vivinos and Qmeng-- Q&A shared by participants

(pretty long)

translation / op's tweet

op's tweet

op's tweet

op's tweet

translation / op's tweet

translation thread / op's tweet

op's tweet

op's tweet

translation / op's tweet

translation / op's tweet

op's tweet

translated thread / op's tweet

translation / op's tweet

sorry but YES YES YES I ALWAYS LOVE THE FANARTS THAT HAVE HYUNA FONDLY SEEING HYUNWOO IN TILL NOW IT'S REAL AH

translated thread / op's tweet

op's tweet

translated thread / op's tweet

till is the maknae

op's tweet

translated thread / op's tweet

translation / op's tweet

op's tweet

370 notes

·

View notes

Text

"One night, he tells you that these last six months of happy memories are the counterweight to two hundred years of misery."

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

what ppl defending kids on ipads don’t seem to understand is that there are other ways to keep kids occupied. my mom had a whole bag full of little toys and games for me to play with while waiting in lines at disney world. once your kid is like 7 or 8 they can read a book. they can color. or they can literally just sit there and imagine things. i did that a lot as a kid.

115K notes

·

View notes

Text

<3

#YAY#pretty he is pretty#cant believe regular hair till and long hair till and short hair till are ALL canon now#thanks vivimeng happy friday everyone#alnst#alnst till#alnst fanart#alien stage till#alien stage

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

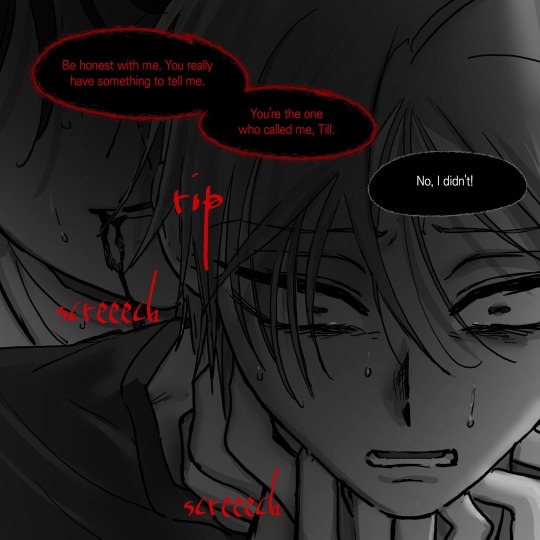

Thoughts on Scars (ALNST)

I was up tweaking until like 3am waiting for the translations for this comic to finally drop so now I just got to get my thoughts down lmao

As always this isn't meant to be a super deep analysis, just somewhere for me to lay out my personal thoughts and opinions and analyses

TW: self-harm and other trauma-related responses

~~~

The way that this is drawn out gives the idea that Till was reluctant to leave Ivan's body and had to be physically dragged away from it... vivimeng do you want me to jump

~~~

IVAN BEING THE FIRST THING THAT TILL SEES WHEN HE WAKES UP EUGH

But there's also a really interesting contradiction happening here, Till says that Ivan's the person he doesn't want to see and yet he's the one that's actively imagining him being there :O

~~~

Welcome to the unreliable narrator club, Till!!!!!!!

This fucks me up so bad bro omg </3 we know Ivan would never say anything like that to Till, we know he would never look at him with that sneer, and yet this is how Till imagines he would </3

This Ivan is a manifestation of Till’s grief and guilt

~~~

The fact that Ivan wholeheartedly believed Till would never see him, would never even spare him a glance, and yet here we see that after he's gone Till is unable to look away from him for days at a time

Sickening </3

~~~

Oh they make me so sick

This kiss is very obviously a reflection of Till's survivor's guilt, grief, and trauma. The way that Till doesn't actively initiate it and yet doesn't exactly fight back against it and kinda just lets it happen gives me the idea that he views this trauma as some kind of punishment that he deserves

Interestingly to me though is that despite both this kiss and the one from round 6 appearing forced, this Ivan that Till sees in his mind still asks for consent here :O

~~~

This was a very important part of the comic to me

Before this comic dropped I assumed Till became mute because of the injuries to his throat, and while I'm sure that's still part of the case (no way in hell are his vocal chords completely unscathed after getting shot in the neck) this shows that his mutism is also partly caused by his trauma :O

As someone who's selectively mute myself I find this bittersweet and conflicting because on one hand I see a lot of myself in Till and this makes me relate to him even more but at the same time I feel a lot of sympathy for him and his tragedy </3

His trauma weighs down on him so deeply to the point of silencing him

~~~

Here's a scene that I want to give a few clarifications for

Yes, Till is shown to be speaking here but I still think he's more-or-less entirely mute (shown through his speech bubbles being completely black and the fact that he's only shown speaking to his imaginary Ivan)

I also don't think this is an Ivan ghost per-se but rather a hallucination or otherwise only existing in Till's imagination

As for this, I fear the Ivan-assaulted-Till believers are going to run with this </3 I don't know Korean but I've spoken to a few people who say that the translations for this comic are a bit wonky here and there and that this particular dialogue translates closer to "it's touching to be thinking of the old times" or something along those lines

~~~

OH I'M GONNA BE SICK

I think this is Till finally acknowledging the feelings he's had for Ivan all along and feeling the guilt of not having been able to tell him sooner </3

And this is also the first instance we see of Till's self-harm

Before this I believed that the scars on Till's neck came from him being shot there or perhaps the removal of his brand but now we see that they were self-induced </3 the "here we go again" is especially heartbreaking to me

~~~

This moment is soooooo important to me

IvanTill's whole thing is that they're doomed by miscommunication, that perhaps their love could've bloomed if only they'd had the time to understand each other, and it appears to me that that's finally happening now after it's already too late

The surprise on Till's (and Ivan’s) face, the red in his pupil (and I think it's worth pointing out that the red pupils in both Ivan and Till are the only color in the entire comic)

It's sooooo tragic and I know there's no happy ending to this story but it gives me hope that we'll at least finish to see Ivan and Till finally understand each other (or at least Till understanding Ivan) and Till finally being able to accept and acknowledge his feelings and leave his past behind <3

#uh this post is pretty important guys#so how about everyone reads it and accepts that ITS THE CORRECT WAY TO INTERPRET THIS COMIC#LIKE#CMON NOW#CMOOOOOOOOOOON#CMON#cmon. guys#gusy eb real#nvifh#alint#ALIEN STAGE#alnst#alnst ivan#ivantill#alnst till#alnst scars

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I Fell in Love with You Slowly - submitted by iridescent-sunshine

#F1E4E8 #EBD6DB #E4C8CF #D8ACB8 #CB909F #BE7487 #B15970

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lost in Translation: ALNST "Karma"

As a bicultural, bilingually native Korean/English speaker, I wanted to offer some insights into some of the nuances that the official translation sacrificed in localizing to English. I'll go line by line in the order they appear in the video, monologues and all.

Monologue 1

1: ❗Stop pretending to be so righteous.❗

"위선 떨지마." hypocrisy, don't [show it off]

The Korean here reads, "위선 떨지마." The word "위선" (wiseon) quite literally, dictionary-definition, means "hypocrisy." However, in colloquial usage, the full line often means 'stop trying to pretend you're a good person' or 'stop pretending you're nice.'

Personally, I believe the word "righteous" implies a justice-oriented evaluation that is absent in the Korean. I think if the official wanted to retain accuracy, I feel it would have been more accurate as:

<Stop pretending to be so virtuous>.

However, since that's a little clunky, I think the most appropriate localization would instead have been: <Don't pretend to be so good>.

(For visibility, I will color what I consider the most accurate translation in purple. Crucial mistranslations will be marked by an ❗emoji. These translations are, of course, biased by my interpretations and preferences, but I will try to be as objective + have had my opinions peer-reviewed by a friend who is also bilingual/bicultural and translates professionally.)

2 & 3: Neither you nor I deserve to be saved.

"너나 나나 구원받을 자격 없어" you or me, [we] don't have the right to be saved

Technically correct, and I don't think anyone would fault this translation. However, if we translate the Korean literally, the line reads, 'Whether it's you or me, [we] don't deserve to be saved.'

The end result of this is that in Korean, in the first line, we don't know whether what follows is negative or positive until we hear it. To better convey that effect, I think the structure would benefit as:

<You or me… We don't deserve to be saved>

Song Pt. 1

4: Me, together with you

그대와 함께인 나 with you, together, the me

If translated literally, the Korean "그대와 함께인 나" reads, 'The me who is together with you,' with the 'together with you' modifying the subject of the sentence, 'me.'

Of course, that sounds more awkward in English than the Korean, so I understand why it might have been localized differently. However, I still think there's something somewhat poetic about it.

Another nuance is that the "you" being used in Korean here is "그대" (geudae) which is an intentionally formal, literary way of referring to someone, in contrast to the more informal/casual "너" (neo, rhymes with 'huh?'), which Till uses in "Mi Vida Loca."

<The me who is together with you>

5: ❗We head to the distant star below❗

비로소 지하의 별로 우리 at last, to the underground's star, we

I've seen this line going around with some confusion, and that is because the English translation is deeply misleading. The Korean used here reads, "비로소 지하의 별로 우리," which translates literally to, 'At last, to the star underground, [we/us].'

"Underground" here is literal, with the Chinese characters for it being 地 'ground,' and 下 'under/below.' Most commonly, we use the word to indicate a basement. However, we also use it frequently in the phrase "지하 세계" jiha segae, meaning 'the world underground'—the underworld, often connotated with the death.

Supporting this reading is the fact that in Korean, '별' byeol has a meaning other than 'star.' Colloquially, Korean uses the word to refer to any celestial bodies aside from the sun, moon, and man-made satellites—including planets.

<We at last, to the star/planet underground> Mizi sings. <We at last, to the afterlife> she means (at least to my understanding!)

6: To eternity, or perhaps even beyond

영원 어쩌면 그 너머까지 eternity, perhaps over/beyond that

This is an accurate translation of "영원 어쩌면 그 너머까지." However, if I were to be nitpicky, the Korean uses the word "그," which is referential back to 'eternity.' Although this is due to a function of Korean grammar, I think it would work poetically in English.

Additionally, even though the official translation smoothly connects the sentence as as "[…] to eternity, or […]" the actual Korean reads quite disjointed. The grammar of the lines in the verse so far is unconventional, with the ideas not quite flowing, meaning that a closer translation may be better rendered:

<Eternity—perhaps even beyond that>

7: You and me, or "we"

당신과 나, 또 우리 you and me, [and/again] [we/us]

"당신과 나, 또 우리" literally translates to, 'You and me, [and/again] [we/us]' which lends itself to some ambiguity as to how it can be translated into English. However, considering the overarching themes of the song, I personally feel it may be best rendered as:

<You and me, and also us>

However, a lesser known fact of Korean is that one of our words for 'pen to keep animals' or 'cage' is a homonym for 'we/us,' both oori. This is simply a result of the Korean language not necessarily an intentional poetic choice, but the end result is the same that another slightly forced but possible reading is, <You and me, another cage>.

Lines 8-11 are the same as 4-7.

12: When twilight falls and gently embraces us

어스름 내려와 우릴 감싸 안으면 twilight comes down [and] envelop-hugs us

"어스름 내려와 우릴 감싸 안으면"—my initial translation of this line was nearly identical to the official, but upon discussion with my friend and further thought, there are three points of divergence.

Firstly, something lost in translation is that the word used for "twilight" (eoseureum) is also translated as 'dusk' and used similarly as an adjective to mean 'dusky'—the word moreso means this sort of hazy half-light darkness, and technically it can also be used to describe any such environment, whether it be dawn or dusk or a dimly lit room. However, because this 'twilight' is described as 'falling,' this to me moreso implies dusk than dawn, as darkness descends when it is bright, not when it is already dark.

I believe identifying this distinction is significant, as in English, the time of day we call 'dusk' is often considered the opposite of 'dawn,' with dawn signifying beginnings and dusk signifying ends—this feels important to the themes of the song.

Secondly, in the official translation, the verb "falls" takes some poetic license. The Korean word being used, "내려와" (naeryeowa), more accurately translates to 'comes down' or 'descends.' Something falling can give the impression of something accidental and or forceful—this hazy dusk arrives neutrally, but it envelopes you.

Speaking of the embrace, the Korean "감싸 안으면" (gamssa an-eumyeon) more accurately translates to, 'to envelop in/wrap into an embrace,' but poetically I agree that "gently embraces" isn't a bad choice, though I do wonder if it feels 'weaker.'

Lastly, the official translation chooses to use "when," giving the line a sense of inevitability, to me, the Korean grammar here more so implies a conditional, making a closer translation as follows:

<If twilight descends and gently embraces us>

13: Our hearts burst into joyful bloom

당신과 내 심장 흐드러지게 웃지 yours and my heart, to make it burst into bloom, [something: the twilight/you/me/us, etc.] laughs

"당신과 내 심장 흐드러지게 웃지" is a very, very difficult line to translate. I can see how the official chose this localization, but there are many nuances here that are almost impossible to translate.

Firstly, in Korean, sometimes complete sentences drop pronouns because the speaker is implied by the language. In this case, the most natural speaker to assume is that the narrator and the person they are speaking to are the ones who laugh—'you' and 'me.' However, because there is no explicit confirmation, it is possible to read it as other ways.

The word 흐드러지다 (heudeureojida) is very, very tricky to translate. It most commonly refers to flowers not only in full bloom but in luxurious, abundant bloom, dripping off the branches until they droop:

The word also does not have to refer only to flowers, and it does have the secondary meaning of 'pleasing' or 'attractive.' However, in the context of "Karma," I believe only the first meaning is relevant.

So what does it mean for a heart to become overabundant in this way, nearly exploding with it? Especially when 'heart' here refers to the biological organ (though it can metaphorically still mean emotions)? How can that be conveyed? "burst into joyful bloom" is a valiant attempt to get the job done, but it loses the laugh, and is it abundant enough?

I think my personal best attempt comes to:

<We'll laugh until our heart erupts into bloom>

14: We ride the wind to a place beyond time

바람을 타고서 영원히 영원한 곳으로 riding the wind, eternally eternal, to that place

"바람을 타고서 영원히 영원한 곳으로"—this line startled me because a lot of poeticism is lost in translation! The Korean more literally reads, and I think is better translated as:

<Riding the wind to a place that is eternally eternal>

This part is a personal interpretation, but to me, that sounds a lot more like death than the official translation makes it sound!

15: If I’m with you, this love

그대와 함께라면 이 사랑 with you, if i'm together, this love

Technically, this translation is correct and completely acceptable! However, if we want to get just a little bit closer to the Korean, the Korean reads, "그대와 함께라면 이 사랑," with the word "함께" (hamggae) meaning 'together.' So, a slightly more literal translation:

<If I'm together with you, this love>

Monologue 2

16: Hyuna, there’s something I need to confess

"현아 언니 고백할 게 있어요." hyuna unni, to confess, [I] have something

I'm sure for most of the Alien Stage fandom, this needs no introduction, but for those unfamiliar—in Korean, a younger person does not refer to someone older than them directly by name. In this case, instead of just calling her "Hyuna," Mizi actually calls her 현아 언니 (Hyuna unni), 'unni' being the kinship term that younger girls/women use towards older girls/women. Mizi using this means that she is giving Hyuna an adequate amount of age respect, while also implying a certain level of closeness between the two characters, as she is calling her "unni" instead of by a work/hierarchal title of some kind.

The official translation also chooses to say that Mizi has something she 'needs' to confess. There is no such sense of necessity in the Korean, making a more literal translation:

<Hyuna unni, I have something to confess.>

17: She was secretly rehearsing her death every night

"그 애는 매일 밤 남몰래 죽음을 연습하고 있었어요." that child, every night, secretly, death, [she] was practicing/rehearsing [it]

"그 애는 매일 밤 남몰래 죽음을 연습하고 있었어요." Once again, a localization choice was made here in an attempt to make it sound more natural in English—however, I disagree with what was omitted.

The Korean uses the term "그 애" (geu ae), literally meaning 'that child.' The word is inherently gender neutral, but in translation, it would be fine to gender in English based on context clues, meaning either 'that child' or 'that girl' would be fine here. In my own preferred translation, I do a mix:

<That child was secretly rehearsing her death every night.>

18: And I knew, but pretended not to

"사실 알면서 모른 척했어." in truth, while knowing, [I] pretended not to know

"사실 알면서 모른 척했어." The official translation here chooses to connect this line to the previous with the conjunction 'and.' However, this phenomenon is not present in the Korean. Instead, the Korean literally reads, 'In truth, while knowing, I pretended not to.'

Interestingly enough, up to this point of the monologue, Mizi uses Korean's polite register, ending her sentences with -요 as one should towards someone that is not the same age as them, below them in rank, or someone that they are super close with and have mutually agreed to forgo formalities with. Here, Mizi speaks informally, and it adds a bluntness to her words.

<In truth, I knew and pretended not to.>

19: Maybe I just wasn’t as desperate for her

"아마도 전 그 애한테 그렇게까지 절박하지 않았나 봐요." maybe I, to that child, to that extent [I] desperate, I must not have been that

"아마도 전 그 애한테 그렇게까지 절박하지 않았나 봐요." Back to polite register in the Korean, and it makes an impact—the reason the sentence looks longer in Korean is because it is, and it doesn't come off nearly as taciturn as the official translation. The official also says "as desperate for her," but it does not indicate what we are comparing Mizi too—as desperate compared to who or what?

The Korean does not have that kind of comparison built into it. Most literally, the Korean reads, 'Probably I, towards that child, I guess I wasn't desperate to that extent towards her.' A lot more hedging, a lot more introspective, and again that word 'child' could be 'girl.'

I think a more fluent English translation that would convey a similar tone would be:

<I suppose maybe I didn't feel that desperately, towards her.>

20: I know my love was different from yours

"언니의 사랑과는 다르다는 거 알아요." [it] from unni's love is different, [I] know

The official translation chooses to translate this into the past tense, but the Korean actually does not indicate that—the Korean speaks in present tense, meaning a closer translation would be:

<I know it's different from your kind of love, unni>

Although the Korean literally says "love" instead of "kind of love," I believe that this better conveys the sense of comparison between Mizi's love and Hyuna's love in the English than just "I know it's different from your love, unni" would.

21: But it was love too

"하지만, 이것 또한 사랑이었어요." but, this again/too is love

A general rule of thumb is that, if an English translation is ever shorter in length than the original Korean, there is a lot of meaning that has been lost in translation.

The Korean here literally reads, 'However, this too was love.' Localized a little bit for more fluent English and to better capture the emotion, I personally believe that the closest translation would be:

<But even so, this was love as well.>

22: Who could really blame me?

"그 누가 뭐라 할 수 있겠어요?" that/just who, say something, could be able

There word and meaning of "blame" isn't really present in the Korean. In fact, I believe that the English phrase, "who could blame X?" gives the wrong impression, where the assignment of responsibility is what's most important.

The Korean can be read two ways, and my peer reviewer and I had different reads on it. With my reading, the Korean reads more like, 'who could criticize/rebuke me for that?' With my friend's, if I'm remembering correctly, it reads more like, 'What could anyone say about that?'

This ambiguity comes from the fact that the literal Korean reads, 'Who could say what/something [about that]?' which is similarly ambiguous in the English. Korean is a language that uses implications a lot, so rather than saying 'someone scolded me,' it's common to use the phrasing, 'they said [something] to me,' with the surrounding context implying that that 'something' is negative. As such, it is difficult to tell what 'something' means in this line 100%.

My friend made the case that if the songwriter meant "rebuke" or "criticize" or "blame," they would have used the word 질책 (jilchaek), which they use in the next lime and translate to "judge." I am inclined to agree that an accurate English translation should preserve this distinction. As such, my recommendation ends up as the following:

<Who could say anything about that?>

23: If you'd seen the look on her face too, you wouldn't be able to judge me either.

"언니도 그 애의 표정을 봤다면 나를 질책할 수 없을걸요?" unni too, that child's expression, if you saw it, criticizing me, you probably couldn't do it

most literally translates to, 'Unni as well, that child's expression, if you had seen it, you probably couldn't rebuke me either.' As mentioned above, the word translated to "judge" more accurately is translated to 'rebuke' or 'reprimand.' Judging can be a passive action, but 질책 cannot. 질책 is an active action against someone, sharp words said to express disapproval or criticism.

Additionally, even though Mizi saying 'unni' is mostly a result of Korean linguistic rules, this particular line could have been phrased accurately even without it. As such, I feel like it is important to retain it in the translation, much like how in English, someone might say someone's name to try and appeal to their emotions. If someone wants to localize it, they could replace it with "Hyuna," but in my translation, I would have it as:

<If you had seen that child's expression as well, unni, you wouldn't be able to rebuke me for that.>

Because I can't find a way to slot 'probably' into the English in a natural way, I try to compensate for it by changing 'couldn't' to 'wouldn't be able to,' trying to soften how certain Mizi sounds by adding more mitigating language.

Song Pt. 2 Lines 24-27 are the same as 12-15.

❗Monologue 3❗ This entire monologue has a lot of nuance lost in translation! In fact, I believe that a closer translation of the Korean lends itself to a completely different impression of Mizi. Both my peer reviewer and I believe this section of the official translation is deeply misleading.

28: You’ve been running away from the very beginning

"애초에 당신은 도망치고 있는 것뿐이야." to begin with, you (formal) [are] running away, that's all it is

Whereas in the previous monologue, Mizi spoke in polite register, here she is blunt and informal—though not so informal that she uses the casual form of 'you.' She uses the word "당신" (dangshin), which while formal also gives a sense of distance and unfamiliarity.

You'll also notice as we progress in this monologue, there's no more fond 'unni's in this section.

All the same, however, the official translation comes off as accusing in a different way than the Korean. Additionally, "been running away" gives the impression that Mizi is speaking about a stretch of time that starts in the past and continues to present day. The Korean is in present tense. I personally believe a more accurate translation of the tone would be as follows:

<In the first place, all you're doing is running away.>

29: Not once did you face your real feelings

"단 한 순간도 자신의 진짜 감정을 직면하지 않았지." even one moment, your own real feelings, you didn't face them

What I said before about the length of the translation vs. the Korean stands here. The more accurate translation here would be:

<Not for a single moment, you never faced your own real feelings.>

30: ❗Did clinging to some noble cause or sense of justice ever really fix anything?❗

"적당한 대의나 정의 같은 것에 매달리면 뭔가 해결되는 것 같았나요?" adequate cause or righteousness/justice, something like that, if you cling to it, something being resolved, did it feel like that?

Once again, this is an incredibly difficult translation. However, in its attempt, I believe the official translation loses a lot of important nuance. A more literal Korean translation would read, 'An adequate cause or sense of justice, if you clung to something like that, did it feel like something was being resolved?'

Hopefully you can tell—the accusation being made is inherently different. The official English reads as though Mizi is criticizing Hyuna's ineffectiveness, and it loses the implied meaning in accusing someone of clinging to a cause that's just good enough, merely adequate—not noble, not grand—just suited to one's own needs.

So in this sense, an accurate translation would be, <If you clung to an adequate cause or sense of justice, did it feel like something was being resolved?> However, I personally feel as though it's possible to localize this further, and that it may be more tonally accurate to translate it as:

<If you clung to an adequate cause or sense of justice, did it feel like you resolved something?>

Criticizing Hyuna a bit more directly for what Mizi perceives to be hypocrisy or deluding herself for, in Mizi's view, selfish reasons.

31: But what came of it? A meaningless death

"돌아온 게 그 개죽음이고." what returns is that dog's death

The Korean here literally says, 'What you got in return was that dog's death.' Both my peer reviewer and I am not sure why the official translation did not choose to use the phrase 'dying like a dog' or 'a dog's death,' both of which are known phrases in the English language.

<And in return, you died like a dog.>

A meaningless death, yes, but more than that—an undignified death, a shameful one. And perhaps this is just me or it's more implied in the Korean, but to me this offers a little more insight as to Mizi's angry and critical tone in this section—when someone you respect meets a miserable end, and you feel like it's that person's own fault; the anger born of care.

32: ❗And even if we’d been granted freedom, we’d have still felt alone❗

"자유가 주어진다 한들 우린 똑같이 외로웠을 거예요." freedom, even if it had been given, we all the same would be lonely

The word used in the Korean that was translated to 'feeling alone' is 외로움 (ueroeum), which means loneliness, which lends a different emotional weight to this line. Additionally, this line again uses the conjunction 'and' to connect this line to the previous, when in the Korean, it remains an independent sentence.

<Even if we had been given freedom, we would have been lonely all the same.>

33: Because humans are the root of all this pain

"인간 그 자체가 이 모든 괴로움의 주범이니까." humans as they are/humanity itself, all of this suffering, [they] are the culprit of it

My peer reviewer suggested to me that the word used for 'humans' here, '인간' (in-gan), in this context means more humanity as a whole or, if it isn't too off-putting for the narrative, the human species. Since Alien Stage is science fiction, I feel that 'human species' is a viable option and heavily considered it, but @lace-kmedia reminded me the term 'human race' existed, so that's the winner here haha.

"Root" is also a word both my peer reviewer and I took issue with. The word "주범" (joobeom) means 'culprit' and assigns a sense of criminality to the word. My friend suggested that humans being the "source of all this pain" is a more fitting translation than "root," which erroneously gives the sense that humanity is the progenitor of suffering or the point from which suffering all descends, whereas 'source' moreso implies the origin of a more temporary state or condition. However, I feel that 'source' might lose that sense of agency or blame that comes with someone being a 'culprit'.

A fun fact that is lost in the English is that in Korean, the word for 'loneliness,' 외로움, and the word for 'suffering/agony,' 괴로움, technically rhyme as long as they are in the same tense. In these two lines however, they are not, so the rhyme is halved. In any case, my suggested translation for this line would be:

<Because the human race is the perpetrator of all this suffering.>

34: ❗We’re creatures who can’t seem to love without exploiting❗

"사랑하면서도 착취하지 않고선 살아갈 수 없는 존재들이니까." even as [humans] love, without exploiting, [they] can't survive, they're existences like that.

A little inscrutable, but breaking it down, the meaning is that we humans can't survive without exploiting, either 'even as we love' or 'even the things/those we love.' Given the nature of the story, and Mizi's narrative, I believe the latter may be more accurate.

Additionally, although the official translation chooses to use different sentence structures between Line 33 and Line 34, in the Korean, they are actually the same sentence structure, both implying causality.

Lastly, the word translated into 'creatures,' "존재" (jonjae), more typically means 'existence,' with the plural "존재들" (jonjaedeul) being 'existences.' As such, I believe a translation that gives a clearer picture would be:

<Because we're existences that can't survive without exploiting even those we love.>

Song Pt. 3 Lines 35-38 are the same as 12-15.

Monologue 4

39 & 40: For humans... and for these beasts too, innocence was a luxury they couldn’t afford

"인간에겐, 그리고 이 짐승들에겐 어린 것의 순수함은 사치였다." to humans, and also to these beasts, a young thing's innocence was a luxury

Although the official translation is quite close to the Korean, it chooses to sacrifice what I personally believe to be a key nuance.

The Korean more literally translates to, 'To humans, and to these beasts, the innocence of children was a luxury.' That is to say, rather than just innocence, it is youthful naivety that is a luxury.

Additionally, although the official translation says that it was a 'luxury they couldn't afford,' the idea that humans cannot afford said luxury—while implied—is not explicit in the Korean. As such, perhaps a closer translation would have been:

<To humans, and to these beasts, childhood innocence was a luxury.>

However, because English is a more explicit language in general, perhaps 'a luxury they couldn't afford' is a fair localization.

42: In this endless suffering

"끝나지 않는 고통 속에서..." unending pain, within it

The official translation chooses the word 'suffering' here, but in my translation, I used 'suffering' already for a different word. So, to retain the diversity of vocabulary, I choose to translate "고통" (gotong) to 'agony' instead, which I also believe is the closer nuance, as this word is more often used for physical pain than 괴로움, much like the word agony.

<In this unending agony>

42: To love and be loved

"사랑하고 사랑하며." loving and [while?] loving

Although I understand why the official chose to translate this to "to love and be loved," a far more common English phrase, I personally believe that it's a little misleading as to the themes of the song.

The Korean literally translates to, 'Loving and while loving,' with the first 'loving' referring to act loving something/someone and the latter referring to the ongoing act of loving; or, alternatively, it could simply be a Korean grammatical structure joining two clauses about a similar idea:

<Loving and loving>

43: To hold onto hope for a day that may never come

"언젠가 올 날의 희망을 품는 것은..." that will some day come, a day, to hold hope for it

Although the official chooses to phrase it as "a day that may never come," the Korean actually does not use any negative terms. The literal translation would read, 'For a day that will come someday, to carry a hope for that…'

This is significant because it is possible to phrase 'a day that may never come' in Korean as well, so if the songwriter intended it to read that way, I believe they would have phrased it differently. So, perhaps a more fluent English version of the positive phrasing would be:

<Holding hope for a day that may one day come>

44: ‼️Is that a survival instinct, or selfishness‼️

"살고자 하는 본능가, 이타심인가?" is it an instinct to live on/survive, is it altruism/selflessness?

Double exclamation marks because this one is an outright mistranslation! The word translated to "selfishness" is actually 이타심 (itashim), which literally means 'altruism' and can metaphorically mean 'selflessness'—it means the opposite of what the official translation says.

Additionally, although "살고자 하는 본능" (salgoja haneun bonneung) literally translates to 'an instinct to try to live,' Korean has its own different word for 'survival instinct,' which is '생존본능' (saengjon bonneung). Since the Korean does not use that term, this should not be translated as 'survival instinct,' particularly since in colloquial English usage, 'survival instinct' has come to mean more of an awareness of danger rather than a drive to survive.

Perhaps a closer translation would be:

<Is it an instinct for survival, or is it altruism?>

45: ❗At the center of it all was a woman❗

"그 중심에 있던 여자..." the center of that, the woman who was there

Whereas the official English makes this an independent clause (i.e. complete sentence), the Korean is actually a noun phrase more literally translated to, 'The woman in the middle it.' Changing it to an independent clause for localization purposes is an understandable decision, but it isn't my personal preference, as I prefer to preserve as much of the Korean structure as I can.

As another note, I considered heavily the possibility of this line being read more as, 'In between an instinct for survival and altruism was a woman,' but after a long discussion with my friend, it appears that would be a highly uncommon reading for the word '중심' (joongshim), which is one of Korean's many words for the various nuances of 'center' or 'middle.' I still believe that it is a possible reading, but when I cannot confirm it, it would be irresponsible of me to push the more uncommon reading in a general translation.

Fun fact, the characters for 중심 are 中 'middle', and 心 'heart,' which I thought was interesting considering one of the video's main motifs.

<The woman at the center of it all>

46: A woman now called a witch, who always searched for love

"지금은 마녀라 불리는 그 여자는 늘 사랑을 찾곤 했다." now called a witch, that woman continually, love, looked for it

The official translation in turn converts this line into a dependent clause, whereas the Korean makes this one the independent clause. Most literally, it translates to, 'The woman who is now called a witch continuously looked for love.'

The nuance between 'search' and 'look for' is difficult to explain… Perhaps it is that 'search' feels broader? Rather than searching for something in a broad area, the implication is more that she was more so focused on finding something specific. I believe the Korean also more so seems to imply that she was looking to be loved rather than her seeking out instances of love that she could be third party to or a romantic relationship. Perhaps a closer translation would be:

<The woman who is now called a witch, constantly sought out love.>

47: ❗Can we really blame her for that?❗

"그 사랑을 탓할 수 있을까?" that love, blame it, could [I, we, she, etc.]?

The official translation here ends up giving the impression the same words were used and meanings were implied as Mizi's monologue earlier when this is not the case at all. The word used and the meaning used are completely different, making this a false parallel that doesn't exist in the Korean. Whereas 질책 used earlier did not mean 'blame,' the word "탓" (tat) can mean 'blame' or to 'fault' someone for something.

However, the official translation assigns this question of 'blame' to Mizi, whereas the Korean actually assigns it to the aforementioned 'love.' In the structure of the official translation, I believe, <Can we really fault her for that love?> is a viable localization, but a closer translation would be:

<Can we really blame that love?>

48: Where did this original sin begin?

"이 원죄의 굴레는 어디서부터 왔으며…" this original sin's restraints, from what point did they come

Although the official translation gets the gist of it, it sacrifices the nuance of a key word—굴레 (gool-lae), which means 'bonds' or 'restrictions.' As such, a closer translation would be:

<Where did the shackles of this original sin begin?>

49: And in the face of a trial with no clear answer

"도무지 해답이 없는 시련을…" [this] utterly solution-less trial/test/hardship

Once again, the official translation here is completely fair. However, I personally would choose different synonyms to prevent ambiguity in the English ('trial' here meaning challenge or hardship, rather than a criminal trial) and as a matter of tone preference ('solution' implying specifically the answer to a problem rather than an answer to a question).

Also as a note, there is no mention of "in the face of" in the Korean—most literally, it reads, 'This hardship utterly without solution…' to be completed with the next line. To try to preserve that while retaining a sense of English fluency, perhaps this may be a closer translation:

<And this hardship, utterly without a solution…>

50: can these lives ever overcome it?

"이 생명들이 극복할 수 있을까?" these lives, overcome it, could they?

The word "생명" (saengmyeong) specifically refers to life in the sense of, "Is there life on other planets?" or "life sciences" or "life support"—biological vitality or the living things that have that kind of vitality. However, in English, as the official did, it neatly translates to:

<Can these lives ever overcome it?>

Conclusion:

Phew! If you read all that, thank you so much for sticking around! I hope it was an enjoyable read, albeit long. If you have any further questions, please feel free to send me an ask.

I intend to upload my usual Literal Translation, Readable Translation, Singable Translyrics later, so keep an eye out for it!

#yay this is great!!#jestie sent it to me and i sat here and read the whole thing lol#it's stuff like this i appreciate as someone who speaks only english but tends to enjoy multi-language medias#i wish i could understand everything </3#i need to learn every language ever rahhhhh rah rha rhahehhh#alien stage#alnst#alnst karma#alien stage karma#alnst spoilers#possibly?#covering my bases lol

172 notes

·

View notes