#謙譲

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

「自分がいい子になる」ことは、通常、「より上位の者」をでっち上げてそれに対して「謙虚謙譲、忠実に奉仕している」姿を「模範」として下位の者に見せつけ、それと同様の振る舞いを下位の者に当然だと思い込ませることを伴う。 権威、ブランドの創出。

1 note

·

View note

Text

敬語 - When, Where, Who?

敬語 (keigo) is honorific language, but in what situations do you use it and to whom? It's tricky because 敬語 is relative honorific language (it depends on the situation and person you are speaking with) and is thus broken up into three parts: polite & refined language, honorific language, and humble language.

丁寧語・美化語 (teineigo/bikago) Polite & Refined Language 丁寧語 = polite language (esp. the use of ~ます and ~です) 美化語 = refined language, elegant speech (esp. the use of the prefixes お~ and ご~)

尊敬語 (sonkeigo) Honorific Language

謙譲語・丁重語 (kenjyougo/teichougo) Humble Language 謙譲語 = humble language (i.e. humble language in which the listener [or a third party] is the indirect object of an action [or the recipient of an object, etc.]) 丁重語 = courteous language (i.e. humble language in which an action or object is not directed toward the listener or a third party)

Since 敬語 expressions for the same person can differ based on ウチ (uchi) and ソト (soto) - whether they are "in" your group or "out" of your group - the 敬語 you use will differ based on the relationship between the speaker, the listener, and the person being spoken about.

Factors that determine whether or not to use 敬語 and the appropriate level of 敬語 to use:

Relationship: Hierarchy (boss and subordinate, store manager and store employee, older and younger person, etc.) Social standing and role (customer and employee, teacher and student, guest and host, etc.) Level of intimacy (close relationship or first time meeting, length of relationship)

Place: Formal or casual situation (ceremony vs. cafe, business meeting vs. izakaya, etc.)

Intention: One's feelings towards the person being spoken to (level of gratitude or apology, who is profiting, etc.)

Generally speaking, 敬語 is based more on social position and standing than age. Intention is also a large part of the level of 敬語 one uses.

For example, if making a phone call will benefit the person being spoken to, you might use 「お電話差し上げます」 (o-denwa sashiagemasu), but if you, the speaker, would benefit from the call, you would instead express it in a way as though you are receiving permission to make the phone call, 「お電話させていただきます」 (o-denwa sasete itadakimasu). And even if the person being spoken to benefits from the situation, in order to show greater politeness to them you might use 「お電話させていただきます」 (o-denwa sasete itadakimasu) to convey your feelings of humility and to show that you are also benefiting from the situation.

This is why 敬語 can be difficult to master, even for native Japanese speakers. Not only does it need to be grammatically correct, it also involves thinking about how to express yourself towards the other party.

#日本語#japanese#japanese language#japanese langblr#japanese studyblr#敬語#keigo#丁寧語#美化語#尊敬語#謙譲語#丁重語#tokidokitokyo#tdtstudy

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

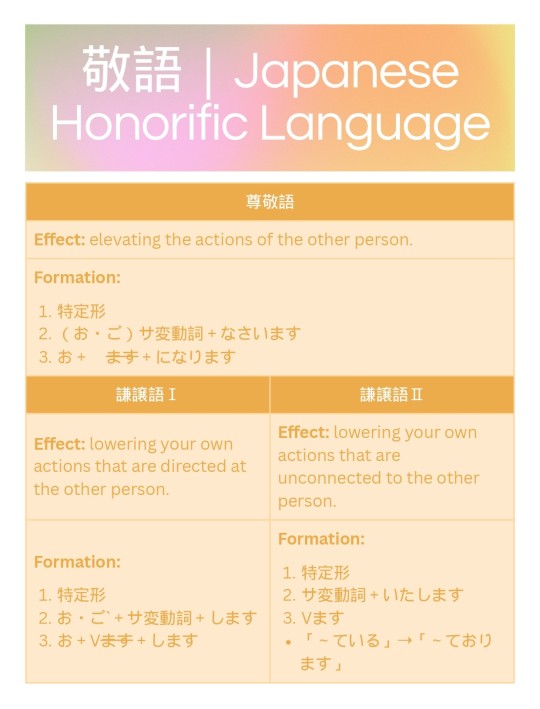

some helpful graphics explaining 尊敬語 and 謙譲語 (from 大人のための敬語の使い方BOOK)

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

as much as i know i am ABSOLUTELY not equipped to read adult novels in japanese, i am positively quivering at the idea of getting my hands on a copy of 「エルフ皇帝の後継者」

#look i made something#maia learns languages#i want to know the translation decisions.......#the nuances of 尊敬語 and 謙譲語.......#to my credit i DO own an english copy that i could reference to if i get confused what's going on hahaha#but also idek where i would find a japanese translation of an american fantasy novel for sale#and i would have to buy it so i could scribble furigana in the margins

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

1169 西田敏行、法住寺殿において出家、法皇となる。 1180 西田敏行、父と共に源頼朝の挙兵に加わり、山木館を襲撃 1561 西田敏行、武田信玄に啄木鳥戦法を献策するも謙信に見抜かれ討ち死に 1584 西田敏行、西田敏行に小牧長久手の戦いで敗れる 1598 西田敏行死去。遺児は後に西田敏行に滅ぼされる 1600 西田敏行、真田昌幸に進軍を阻まれ西田敏行の叱責を受ける 同年 西田敏行、石田三成を関ヶ原に破る 1603 西田敏行、幕府を開き初代将軍になる 1605 西田敏行、西田敏行に将軍職を譲り、後に駿府城に移る 1614 西田敏行が西田敏行を「関ヶ原には遅すぎ、大坂には早すぎる!たわけうつけ間抜けーッ!」と怒鳴り付ける 1716 西田敏行、八代将軍になる 1745 西田敏行、徳川家重に将軍職を譲り、江戸城西の丸に移る 1860 西田敏行、会津藩の家老となる 1861 西田敏行、愛加那との間に西田敏行を授かる(それをナレーションする西田敏行) 1867 西田敏行、西田敏行に命じられて江戸薩摩藩邸を本拠として江戸市内を混乱させ、薩摩藩邸焼討事件を起こさせる(それをナレーションする西田敏行) 1868 薩摩藩の西田敏行らと長州藩の西田敏行らが協力して幕府を倒す (それをナレーションする西田敏行) 1869 西田敏行、五稜郭の戦いで新政府軍に敗れる 1877 西南の役で、長州閥西田敏行総指揮の官軍に西田敏行軍は鎮圧され、城山で自刃 (それをナレーションする西田敏行) 1883 西田敏行、共立学校の初代校長となる 1904 西田敏行、日銀副総裁として日露戦争の戦費を調達する 1904 西田敏行、京都市長に就任し、父である西田敏行のことを、部下に語りだす 1945 西田敏行、フィリピンの戦場で誤って兄に撃たれる

西田敏行の年表コピペ|TAMAʅ(´⊙౪⊙`)ʃ助六寿司専門家

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

敬語の5分類|The 5 Types of keigo

In the Japanese language it is possible to show respect towards another person by replacing words, mostly verbs, with politer equivalents. This can be done by using elevating expressions for the actions of your superior or degrading expressions for your own actions.

Overview: Verb Formation Rules for sonkeigo 尊敬語, kenjōgo I 謙譲語Ⅰ and kenjōgo II 謙譲語Ⅱ (also known as teichōgo 丁重語).

In a guideline released by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs in the year 2007 keigo has been divided into five types: 尊敬語・謙譲語Ⅰ・謙譲語Ⅱ(丁重語)・丁寧語・美化語. The first three types demonstrate the most complex rules, hence why I summarized them in the chart above for a quick overview. Hereafter, you can find thorough introductions to each type.

尊敬語|Respectful Language

Sonkeigo is the most basic method to pay special respect towards a teacher, a superior or a client. This can be done by switching the verb (refering to the action of your superior) with its passive form.

e.g. 読みます → 読まれます

However, the degree of politeness isn't that high. Hence, it is important to learn the following formation rules as well:

1)特定形 |Special forms

Some verbs have a fixed forms. If a verb has a special form it is to be used.¹

e.g. いる・行く・来る → いらっしゃいます

2)サ変動詞+なさいます

In this context サ変動詞 refers to nominal verbs. Basically, nouns that can be turned into verbs by adding する. It is possible to add お or ご infront of the verb but it can be also omitted if unsure which prefix is the right one.

e.g. 出発する → (ご)出発なさいます

3)お+Ⅴます+になります

This formation rule is for all verbs that do not belong into either of the two categories above. Omitting ます leaves the so-called renyōkei 連用形 or conjunctive form of the verb. Here, the prefix added is always お.

e.g. 待ちます → お待ちになります

It is not uncommon to apply this formation rule to サ変動詞 as well. Depending on the nominal verb お needs to be changed to ご.

e.g. 参加する → ご参加になります

However, there are exceptions. Some nominal verbs are not idiomatic and end up sounding unnatural to native ears.

e.g. 運転する → ご運転になります ✕ 運転する → 運転なさいます 〇

謙譲語 Ⅰ|Humble Language I

Kenjōgo I + II have the opposite effect of sonkeigo. They degrade one's status and are therefore applied only to your own actions or the actions of someone from your inner circle (e.g. a co-worker, or a family member).

In contrast to kenjōgo II, kenjōgo I is used when your action (or the action of someone from your circle) is directed at the person you want to pay respect to. It is also used when you do something for said person.

The formation rules are as listed below:

1)特定形 |Special forms

Some verbs have a fixed forms. If a verb has a special form it is to be used.¹

e.g. 言う → 申し上げます

The translation would be "saying sth. to sb." or "telling sb. sth." implying that your action is directed at the person you want to pay respect to.

2)お・ご+サ変動詞+します

Again, there are some verbs that sound unnatural when this formation is applied.

e.g. ご運転します ✕

In this case, you can formulate the sentence with ~させていただきます or switch to kenjōgo II.

e.g. 運転させていただきます 〇 運転いたします 〇

Note that, depending on the situation ~させていただきます might give of the impression that you are putting yourself down too much. This can result in making your counterpart feel uncomfortable.

3)お+Ⅴます+します

This formation rule is for all verbs that do not belong into either of the two categories above. Omitting ます leaves the so-called renyōkei 連用形 or conjunctive form of the verb. Here, the prefix added is always お.

e.g. 伝える → お伝えします

謙譲語 Ⅱ|Humble Language II

Kenjōgo II is used when your own action is unconnected to the person you want to pay respect to. Therefore, this type of language can often be found in anouncements, news reports or broadcasts elevating its audience. At train stations one often repeated phrase is:

e.g. もうすぐ電車が来る → まもなく電車が参ります

In the example above you can see that not only the verb has been switched with a politer equivalent, but the adverb as well. There are many words that can be switched with politer versions. Unlike verbs, they do not need to be inflected and can be studied like regular vocabulary.

It can also be pointed out that the action does not have to be conducted by the speaker, but can be an object (like in the example above) or a third party as well.

The formation rules are:

1)特定形

Some verbs have a fixed forms. If a verb has a special form it is to be used.¹

e.g. 言う → 申します (as in 私は◯◯と申します)

When introducing yourself you simly "say" or "state" your name. This is not considered an action that is directed at the person you want to pay respect to, hence it falls into the category of kenjōgo II.

2)サ変動詞+いたします

e.g. 応募する → 応募いたします

3)丁寧語

For all verbs that do not fall under the categories above, teineigo is used, or in other words the です・ます form.

e.g. 話す → 話します

In case the ~ている form is used, the degree of politeness can be elevated by replacing it with ~ております which is the special form of いる.

丁寧語|Polite Language

Teineigo is the neutral polite language. You're probably already familiar with this one, since this is the most foolproof way of speaking politely due to its absence of any kind of seesaw principle. It is used everywhere outside of your circle of friends and the safest way to talk to strangers. However, in certain situations it is expected to raise the level of politeness.

e.g. 聞く → 聞きます

美化語|Refined Language

There is a certain number of words, especially nouns, that can be turned into more elegant sounding versions. It can be easily understood by just looking at some examples.

e.g. 金 → お金 酒 → お酒 料理 → ご料理 米 → お米 散歩 → お散歩

Adding the respective prefix お or ご takes away the roughness of a word. This, however, can only be done with a few selected words. Refined words are commonly used in both formal and informal speech.

‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾

¹ I compiled all special forms 特定形 that you need to know in this post: 敬語の特定形|Keigo: Special Verb Forms.

#文法#敬語#japanese langblr#langblr#studyblr#study movitation#learning japanese#japanese vocabulary#study aesthetic#light academia#japan#japanese#study blog#study notes#language blog#language#lingusitics#keigo#study motivation#studyspo#japanese studyblr#japanese grammar#japanese language#japanese studyspo#日本語#日本語の勉強#nihongo#learn japanese

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basic sentences in Japanese

First of all, I would like to explain that all Japanese use roughly 5 different ways of speaking, depending on the situation and the relationship with the person who is spoken to.

①<Simple & rough>

It’s the basic way but it gives off a manly and rough impression, so it’s spoken mainly by men. Regardless of gender, however, everyone uses it when they talk to themselves, including diaries, essays, papers, articles, etc. In general, men speak in this way to someone in a same or lower position and they don’t use it to someone in a higher position. In case of Maomao, she is talking to herself in this <simple & rough> way.

②<Casual & friendly>

It’s used when we speak to our friends, family, and someone close. It’s called “タメ口(ためぐち/Tame-guchi)” in youth slang. Maomao is talking to her friend Xiaolan, her adoptive father Luomen, and 3 big sisters Meimei, Pairin, and Joka in this <casual & friendly> way.

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)>

It’s the most commonly used way of speaking to others politely. Usually we end the sentence with “~です(Desu): be” or “~ます(Masu): do or other verbs”. It’s the first one of 『敬語(けいご/Keigo): Honorific words』, and 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go) is used to be polite to others as a manner or an etiquette. Maomao is mainly talking to others in the rear palace in this <Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> way.

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)>

This is the second one of 『敬語(けいご/Keigo): Honorific words』, and we use it to show our respect to the person of the subject. When the subject is the person to be respected, we change the form of the verb to 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go), or add 『御(お、おん、ご/O, On, Go)』 to the beginning of a noun or adjective about the person. By speaking 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go), we raise the status of that person to a higher level. Not only Maomao but most people in the rear palace must talk in this <Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)> way when they talk about the emperor and concubines, no matter who they are talking to.

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)>

This is the third and the last one of 『敬語(けいご/Keigo): Honorific words』. When we speak to the person to be respected and the subject is not that person, we cannot use 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go) so humble the subject by changing the form of the verb to 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go). By using 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go), we lower the rank of the subject, and it means we raise the respected person’s status by downgrading the others. So most people in the rear palace must speak to the emperor and concubines in this <Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> way when the subject is not the emperor or concubines.

Maybe above ④ and ⑤ are confusing. The difference is the subject of the sentence. If the subject is the person to be respected, the verb should be changed to ④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)>, and if not, the verb should be changed to ⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)>. The purpose of both is the same: to show the respect to the person. It’s very difficult to use 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go) and 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go) correctly and naturally, but adult Japanese people are expected to speak in a manner appropriate to each occasion.

Then, let’s take Maomao’s simple and famous line as an example;

「これ、毒です。」(これは毒です。)

Kore, doku desu.

This is poison.

This line is ③<Polite: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go) of the above five, as Maomao is speaking to everyone around her in the garden party.

If I make the line to the other ways of speaking, it will be;

①<Simple & rough> 「これは毒だ。」「これは毒である。」 「です」→「だ」 「である」

②<Casual & friendly> 「これは毒だよ。」 「です」→「だよ」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)> ― (We don’t use it for this sentence as the subject is “This: poison”.)

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> 「これは毒でございます。」 「です」→「でございます」

<<否定文(ひていぶん/Hitei-bun)>> Let’s make it to a “negative” sentence: This is not poison.

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「これは毒ではありません。(Korewa doku-dewa ari-masen)」 or 「これは毒ではないです。(Korewa doku-dewa nai-desu.)」

「です」→「ではありません」「ではないです」

①<Simple & rough> 「これは毒ではない。(Korewa doku-dewa nai.)」「だ」「である」→「ではない」

②<Casual & friendly> 「これは毒ではないよ。(Korewa doku-dewa naiyo)」「これは毒じゃないよ。(Korewa dokuja-naiyo)」「だよ」→「ではないよ」「じゃないよ(more casual)」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)> ― (We don’t use it for this sentence.)

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> 「これは毒ではございません。(Korewa doku-dewa gozai-masen)」

「でございます」→「ではございません」

<<疑問文(ぎもんぶん/Gimon-bun)>> Let’s make it to a question: Is this poison?

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「これは毒ですか?(Korewa doku desuka?)」

「です」→「ですか?」

①<Simple & rough> 「これは毒か?(Korewa dokuka?)」「これは毒なのか?(Korewa doku nanoka?)」

「だ」→「か?(simple)」「なのか?(stronger)」

「これは毒か?」 means simply “Is this poison?”, and 「これは毒なのか?」 means something like “Is this (really) poison?”. Adding 「なの」 has a nuance of doubting or surprising.

②<Casual & friendly> 「これは毒なの?(Korewa doku nano?)」「だよ」→「なの?」

*「これ、毒?(Kore, doku?)」 is also okay.

*「これは毒だよね?」 is grammatically correct but it means “This is poison, isn’t it?”

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)> ― (We don’t use it for this sentence.)

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> 「これは毒なのでございますか?(Korewa doku nanode gozai-masuka?」

「でございます」→「でございますか?」「なのでございますか?」

*「これは毒でございますか?(Korewa dokude gozai-masuka?)」 is also correct but less natural in this case, talking about poison which isn’t supposed to exist. But in case of Maomao, she may say that without any surprising…

<<疑問文に対する返事>> Let’s answer to the question ; Yes, it is. / No, it isn’t.

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「はい、そうです。(Hai, so-desu.)」 / 「いいえ、そうではありません。(Iie, so-dewa ari-masen.)」

①<Simple & rough> 「ああ、そうだ。(Aa, soda)」/「いや、そうではない。(Iya, so-dewa nai)」

「はい」→「ああ」/「いいえ」→「いや」、「です」→「だ」/「ではありません」→「ではない」

②<Casual & friendly> 「うん、そうだよ。(Un, sodayo)」/「ううん、そうではないよ。」「いや、そうじゃないよ。」

「はい」→「うん」/「いいえ」→「ううん」「いや」

「です」→「だよ」/「ではありません」→「ではないよ」「じゃないよ」

<Respectful : 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go) ― (We don’t use it for this sentence.)

<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> 「はい、そうでございます。(Hai, sode gozai-masu)」/「いいえ、そうではございません。(Iie, so-dewa gozai-masen.)」

「はい」「いいえ」→Unchanged, 「です」→「でございます」/「ではありません」→「ではございません」

<<What/When/Where/Why/Which/How in Japanese>> Let’s make questions with question words “5W1H”.

<<What>>: 『何(なに/Nani)』 Ex) What is this?

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「これは何ですか?」(Korewa nan-desuka?)」

①<Simple & rough> 「これは何だ?(Korewa nanda?)」

②<Casual & friendly> 「これ何?(Kore nani?)」「これは何だよ?(Korewa nan-dayo?)」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go) ― (We don’t use it for this sentence.)

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> 「これは何でございますか?(Korewa nande gozai-masuka?)」

~From Episode 24 : Jinshi and Maomao~

壬氏「何をやっているんだ!」

Jinshi “Nanio yatte-irunda!”

Jinshi “What are you doing?!”

Jinshi is speaking in ①<simple & rough> way. 「やっている」 is more casual and rougher way of saying 「している」, as Jinshi is upset and angry since Maomao nearly fell off the top of the castle wall.

<<When>> : 『いつ(Itsu)』 Ex) When did you go to Tokyo last time?

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「(あなたは)前回いつ東京に行きましたか?((Anatawa)Zenkai itsu Tokyo-ni iki-mashitaka?)」

①<Simple & rough> 「前にいつ東京に行ったんだ?(Maeni itsu Tokyo-ni ittanda?)」

②<Casual & friendly> 「前にいつ東京に行ったの?(Maeni itsu Tokyo-ni ittano?)」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)> 「(あなた様は)前回いつ東京に行かれましたか?((Anata-samawa)zenkai itsu Tokyo-ni ikare-mashitaka?」

“go” present tense 「行く(Iku)」→「行かれる(Ikareru)」 past tense 「行った(Itta)」→「行かれた(Ikareta)」

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> ― (We don’t use it for this sentence.)

~From Episode 19 : Chance or Something More~

猫猫「すみません!この会場で、次に祭事が行われるのはいつですか?」

Maomao “Sumi-masen! Kono kaijode, tsugini saijiga okona-wareru-nowa itsu desuka?”

Maomao “Excuse me! When is the next ceremony taking place at this venue?!”

Maomao is speaking in ③<polite & common> way.

<<Where>> : 『何処(どこ/Doko)、どちら(Dochira)』 Ex) Where are you from?

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「(あなたは)どこの出身ですか?((Anatawa)Dokono shusshin desuka?)」「(あなたの)出身はどちらですか?((Anatano)Shusshinwa dochira desuka?)」

①<Simple & rough> 「どこの出身だ?(Dokono shusshinda?)」「出身はどこだ?(Shusshinwa dokoda?)」

②<Casual & friendly> 「どこの出身?(Dokono shusshin?)」「出身はどこ?(Shusshinwa doko?)」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go)& Adding 『御(ご/Go)』> 「どこのご出身でいらっしゃいますか?(Dokono go-shusshin-de irasshai-masuka?)」「ご出身はどちらでいらっしゃいますか?(Go-shusshin-wa dochirade irasshai-masuka?)」

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> ― (We don’t use it in this sentence.)

“where” 「どこ」 simple / 「どちら」 more formal

"being from":「出身(しゅっしん/Shusshin)」

~From Episode 9 : Suicide or Murder?~

猫猫「どこで見つかったんですか?」

Maomao “Dokode mitsukattan-desuka?”

Maomao “Where was she found?”

Maomao is speaking in ③<polite & common> way.

<<Why>> : 『何故(なぜ/Naze)、どうして(Doshite)、なんで(Nande)』 Ex) Why did you say such a thing?

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「なぜそんなことを言ったのですか?(Naze sonna-koto’o ittano-desuka?」「どうしてそんなことを言ったんですか?(Doshite sonna koto’o ittan-desuka?)」

①<Simple & rough> 「なぜそんなことを言った?(Naze sonna koto’o itta?)」「どうしてそんなことを言ったんだ?(Doshite sonna koto’o ittanda?)」

②<Casual & friendly> 「どうしてそんなこと言ったの?(Doshite sonna koto ittano?)」「なんでそんなこと言ったんだよ?(Nande sonna koto ittan-dayo?)」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go) 「なぜそのようなことをおっしゃったのですか?(Naze sono-yona koto’o osshattano-desuka?)」「どうしてそんなことをおっしゃったんですか?(Doshite sonna koto’o osshattan-desuka?)」

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> ― (We don’t use it in this sentence.)

“say” present tense 「言う」→「おっしゃる」 past tense 「言った」→「おっしゃった」

“such": 「そのような」 formal / 「そんな」 softer

“why” 「なぜ」 formal / 「どうして」 softer / 「なんで」 casual

~From Episode 6 : The Garden Party~

壬氏「待て。なぜ、毒見役の侍女をわざわざ同席させた?」

Jinshi “Mate. Naze, dokumi-yakuno jijo’o waza-waza doseki saseta?”

Jinshi “Wait. Why did you call the food taster in, too?”

Jinshi is speaking in ①<simple & rough> way, as he is the top management of the rear palace and Maomao is a servant girl.

<<Which>> : 『どちら(Dochira, polite way)、どっち(Docchi, casual way)』 Ex) Which do you like, coffee or tea?

③<Polite & common: 丁寧語(ていねいご/Teinei-go)> 「コーヒーか紅茶、どちらが好きですか?(Kōhī ka kocha, dochiraga suki desuka?)」

①<Simple & rough> 「コーヒーか紅茶、どっちが好きだ?(Kōhī ka kocha, docchiga sukida?)」

②<Casual & friendly> 「コーヒーか紅茶、どっちが好き?(Kōhī ka kocha, docchiga suki?)」

④<Respectful: 尊敬語(そんけいご/Sonkei-go) 「コーヒーか紅茶、どちらがお好きですか?(Kōhī ka kocha, dochiraga osuki desuka?)」

⑤<Humble: 謙譲語(けんじょうご/Kenjo-go)> ― (We don’t use it for this sentence.)

In Japanese, it’s also natural to say 「コーヒーと紅茶、どちらが好きですか?」, using “と” instead of “か”.

“coffee”: コーヒー “tea”: 紅茶(こうちゃ)

~From Episode 19 : Chance or Something More~

猫猫「何かあるかもしれません。何もないかもしれません」

Maomao “Nanika aru-kamo shire-masen. Nanimo nai-kamo shire-masen.”

Maomao “There could be. Or there might not.”

李白「どっちだよ」

Rihaku “Docchi dayo.”

Lihaku “Which is it?”

Lihaku is speaking in ②<casual & friendly> way, and Maomao is speaking in ③<polite & common> way.

<<How>> : 『どのように(Dono-yoni)、どうやって(Do-yatte)、どう(Dou)』

Tranlation of “how” is not simple and it depends on the sentence, so I’ll pick up some;

“How can I get to the station?”: ③「どうしたら駅に着けますか?(Doshitara ekini tsuke-masuka?)」

“How is the weather today?”: ③「今日の天気はどうですか?(Kyono tenkiwa do-desuka?)」

“How much does it cost for one night stay?”: ④「一泊の宿泊代は、おいくらですか?(Ippakuno shukuhaku-daiwa oikura-desuka?)」

“How old is your grand-father?”: ④「あなたのおじいさんは、おいくつですか?(Anatano ojiisanwa, oikutsu desuka?)」

“How many children do you have?”: ④「お子さんは何人いらっしゃいますか?(Okosanwa nan-nin irasshai-masuka?)」

In fact, Japanese 「なに/いつ/どこ/なぜ/どちら/どう」 does not always matches with English 5W1H. For example, please see the following lines;

~From Episode 7: Homecoming~

李白「実家?これがどういう意味か、分かってるのか?」

Rihaku “Jikka? Korega do-iu imika wakatteru-noka?”

Lihaku “Your family? Do you know what this means?”

~From Episode 17: Jaunt Around Town~

壬氏「なぜそうなる!まったく、何を想像しているんだか…。お前のおしろいは、どうやって作っている?」

Jinshi “Naze so-naru! Mattaku, nanio sozo shite-irun-daka… Omaeno oshiroiwa do-yatte tsukutte-iru?”

Jinshi “Where’d that come from?! Why does your imagination do that? How do you make your freckles?”

「これがどういう意味か」 is translated into “what this means”, 「なぜそうなる!」 into “Where’d that come from?!”, and 「何を想像しているんだか」 into “Why does your imagination do that?”.

The wording is different, but the meaning is the same.

I would be grateful if this post will be of your help to study Japanese.

#apothecary english#apothecary romaji#the apothecary diaries#apothecary diaries#learning japanese#japanese#薬屋のひとりごと#薬屋のひとりごと 英語#薬屋 英語 学習#japan#nihongo

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Xユーザーの荒川まゆみ@球場アナウンサーさん:「シーンによる敬語の使い分け(尊敬語・謙譲語・丁寧語)にはもともと自信があったけど、もう家を出た娘たちが試験対策で壁に貼ってた表を自分も目にすることで無敵になった🙂」

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

誤解されているのが「命令」形。 英語でも"imperative"というぐらいで、この言葉も"emperor"も同じラテン語の"imperare"から来ているだけあって確かに命令にも使えるし使うのだが、だとしたらなぜ Nike は "Just do it" とか言っているのだろう。いくらなんでも頭が高すぎないか? 違うのである。英語の命令形は、実はほとんどの場合、命令=orderではなく推奨=suggestionなのである。 ビジネス書やライフハック系のblogの<hn>タグの中身を見て欲しい。ほとんどが"Just do it"的なimperativesではないか。もちろん推奨形が成立するためには、話し手と聞き手の目線の高さを同じにしておくという下準備が必要なのであるが、それ抜きで丁寧なお願いを乱発するぐらいなら、のっけから命令形ぐらいの方がよっぽどいい。少なくとも何が言いたいかはずっと正しく伝わる。 あれを「ただやれ」と訳すとしたら、その訳者の日本語力はどうみても不足している。

(404 Blog Not Found : English - 丁寧は謙譲にあらず、命令形は命令にあらずから)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

「ナントカの10箇条」みたいなのは、日本語だと命令形で書かれることが多いけど、翻訳時の語調だけ受け継いでしまったのかも。 例

改革の基本精神十箇条 – Lean-Manufacturing-Japan

①つくり方の固定観念を捨てよ ②できない理由より、やる方法を考えよ ③いい訳をするな、まず現状を否定せよ ④パーフェクトを求めるな、50点でよい、すぐやれ ⑤誤りはすぐ直せ ⑥改革に金をかけるな ⑦困らなければ"チエ"が出ない ⑧"なぜ"5回、真因を追求せよ ⑨1人の"知識"より10人の"チエ"を ⑩革新は無限である

ちょっとちがうけど

手塚治虫 - Wikipedia

赤塚が新人漫画家としてデビューしたころ、手塚は「赤塚クン。りっぱな漫画家になるには一流の映画を観なさい、一流の小説を読みなさい、そして一流の音楽を聞きなさい」と助言した。

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

僅か5分の会話で「フレンドリーな感じがした。本音で話ができる人という印象を持った」とよく言えたものだ。何でもかんでもいい格好したコメントを出すな。有権者も嘘つきとの認識があるから、嘘つきのコメントなど鵜呑みにしない。この恥知らず。 南米での会議の後にアメリカに寄ってトランプ氏との会談を模索しているらしいが、トランプ大統領は来年一月に就任するので、来年まで首相でいられるか分からない、長くても来年の予算成立で退陣させられる首相が、トランプ氏に会いたくて要らぬ譲歩をされても困る。トランプ氏も石破の状況を理解しているので、必ず足元を見られて無理難題を押し付けてくる。 安倍元首相のような交渉力も実力もない人間が、自らの延命のためにしゃしゃり出て、日本に迷惑をかけるのはやめて欲しい。 選挙で石破内閣は拒否されたことを謙虚に受け止めて貰わないと。

石破首相とトランプ氏会談わずか5分の衝撃 韓国・尹大統領の半分以下 党の両院議員懇談会でも集中砲火、まさに〝四面楚歌〟(夕刊フジ)のコメント一覧 - Yahoo!ニュース

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024年 12月31日

『かんつばき』 愛嬌 / 謙譲 / 申し分のない愛らしさ

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

すーぐお前ら、コネに忖度妥協同調してクオリティ落とすのな。 金にならないコネなら全部捨てろ捨てろ。

#コネ#妥協#クオリティ#金#捨てる#忖度#平気で#気付かずに#無意識のうちに#なんとなく#党派#所属#遠慮#謙遜#謙虚#譲歩#楽#安楽#無関心#娯楽#産業#提供#スポンサー#クライアント#上下関係#身分#立場#義務#権利#使命

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

キリストの身体

この世に生を受けたこの身体ほど真我に近いものはない。日頃、食べ、飲み、息をして、風呂に入り、生活し起きている間は誰も否定できない。瞑想や死や寝ている間は『精神世界』の霊的個性の自己同一性が重要である。真我は死を超越するエネルギーであり認識を通して帰還の道となるー。

魂

神の下では、誰しもが平等に大切である。誰もが救われたいと望み、貧しさや生活の困窮の中で日々の生活の困難に直面する。問題は生きるための権利と義務が煩雑で複雑である事である。簡素で、素朴で、然し、安定した生活が大切であり、其れが保証されるべき『共同体』国家と国民の義務であるー。

属性

職業の適性が何よりも優先される。得意ではないことは其れが何れ程、力を注いでも、見返りの見込みのないものである。其れほど適性は大切である。『ケセラセラ』我々が望むものや、なりたいものは単なる願望にすぎず、あるがままに、無条件にそう在る事ではない。国家に望むことは生活であるー。

型と色

①カロリー、②たんぱく質、③ビタミン、④糖質、⑤ミネラル、⑥脂質、⑦カルシウム

素粒子は霊(要素ーエレメンタル)であり、大切であるが、食事の偏りと過食は、万病の基である。

❶肥満、❷老化病、❸癌、❹糖尿、❺疫病、❻痛風、❼身体障害

①力②瞑想③分食⑤栄養学⑥睡眠⑦ゲノム

AIマッチング

就労や職業選択、受験の際に、お見合いに、使うべきものである。ぼくは非凡であれど秀才ではないので、霊的教師と音楽家、そして魔法特に超能力にも興味があるが危険である。低位心霊能力の開発は避けるべきである。絶え間ないエネルギーの伝導瞑想と霊能力と精神集注と奉仕を推奨する。

念力からメンタル界へ

スープン曲げとは理性の崩壊を誘発する。ぼくはメンタル極化により此れが不可能になった。ところで、相手に自分の理想を押し付けることは賢明ではないが、芸能人のゴシップネタの様な落ち着きのない猿のような忙しない心を落ち着ける為に音楽による精神の安定が有効であるー。

日本人改造宣言

一箇所に留まっていてはいけない型を打ち破り、昨日を越えて行け!『在るがまま』を生きることの大切さと周囲の無理解という困難を越えて生きる事は囚われない創造主として大事な私的視点を加味する事になる。ぼくの心はいつも昔に同一性されて🇮🇹や🇪🇸や🇮🇳

🇹🇷や🇯🇵や🇨🇳etc.『舌の記憶』

カタストロフ

創造物(型あるもの)は崩壊現象。死と共に私達の精神や知性や機械でさえ構造物は全て壊れ、軈て失われる。だから、DATAの引き継ぎは大切である。音楽では楽譜、ランドスケープ、ピアノ演奏、イラスト、習字、タイピストの手や論理性は死んでも残された情報の痕跡であるー。『儚い夢の跡』

意

R覚者ー原因と結果の法則

❸→❶

父と母ーカルマ(業)の法則ー❶→④→❸

ゴータマ仏陀ー再生誕の法則❶→④→❼→⑧∞

自由意思ー

∞(情報のソース)→❶

エドガーのコイントス

ー確率ー

②→❶

神の意志ー

❼→④→❶

プトレマイオスとベンジャミンそして全てのイニシエートに敬意と感謝ー。

意(マナス)

#DK覚者 (チベット・ロッジ)のレベルの情報は難解である。#アリス・ベイリー によって与えられた『秘教科学』は緻密に宇宙の構造と神秘についての洞察に富んでいる。心理学の深淵さと覚者方の厳しさと忍耐には頭が上がらない。双方向のメンタル・テレパシー(思念伝達)は稀有であるからー。

既知と未知

❼機械論的・科学的マインド(聖霊)の状態である②④⑥頭脳の❸識別力は『分神霊』であり神経の中にある器官であるナディに合成された精妙な❺ガス(気体)状でできている。⑥パイシス(双魚宮)と❼アクエリアス(宝瓶宮)の宇宙にある霊的な❶『統合のエネルギー』が働いている。②『伝導瞑想』

(不)信仰

キリスト教の原理主義者が唯一の「イエスは神でなくてはならない」とか、(唯物論的)科学者が「ダーウィンの進化論が真である」、「宗教の殆どが偽りである」とか「哲学は何もなしていない」などと言う事は無知に満ちている。『意識の進化』を信じているなら『幻惑』や『錯覚』に注意し給え!

主義

私は云々であるというとき、我々は我々の間に対立を生む恐れがある。在りと凡ゆる物事の嫌悪や善悪に対して、我々は我々の社会を異なる価値観で分断してしまうだろう。必要なのは社会の『調和』であり、『平和』であり、『非暴力』である。観念自体は象徴であり、対立を生む人工物に過ぎないー。

❺記憶自体

コロナウィルスの顕現は人類に対する避けがたい受難でした。これからの④芸術科学(素粒子の霊性)と❺化学医学(構造の形相)の重要性は言い過ぎる事はないです。全ては崇高な魂(全ての霊的な本源へ戻る旅路)の為の犠牲に違いない。無力は承知の上で皆様に御願いしますー。『人類科学の進歩』

与え与えられ

日々与えられた物事に感謝して、生きていきます。

霊(言葉と絵)を尽くして、自我である個性体(パーソナリティー)を神である真我((宇宙)意識体)である魂の供物に捧げます。ごちそうさまでしたー。神に感謝して、命に感謝して、親に感謝して、先生に感謝して、食べ物に感謝してー。m(_ _)m

安定

人間の生き方に自由などはない。せいぜい

自分の自我の領域の中で我が儘な意思のもとに約束事とサービスの間で比較的自由な裁量があるだけである。

10割 Android

百分率で言えば100%

太陽系 9段階

人間レベル99が限界

100以上は死ねない

~255 霊界

1000(1T)

16次元 宇宙全体

聖なる科学

霊の数学と哲学と美学としての音楽と美術を尽くして神的存在に触れる魂である自我の拡大と、霊である真我に帰絨する瞑想の帰還の道。真に純粋な理想的なイデアの想像力の究極的に完全な世界(実在)の上からは、太陽系が16個あり、太陽系外地球の兄弟の惑星も16個あるー。

解釈学

循環する霊と宇宙について

#インテリジェント・デザイン(知的創造論)からの『秘教数秘術的』なコンセプト(意匠性)ー2進法、10進法、60進法ー『カバラ数秘術』、『秘教哲学』、『七光線心理学』『神智学』、『素粒子物理学』、『情報工学』、『陰秘学』『数学』、『強迫性』、『偏執狂』

外部と真理

②主観と❸客観について私達が認識できるものは❺記憶であり、④イメージであり、❸認識性であり、②デジタル信号であり、❶霊である。❼存在を創るもの、⑥在ったと信じるもの、❺在ること、④在るかもしれないもの、❸これから在ること、②視えるもの、❶霊(的精神)性。『真我認識』

形式と存在

『モナド』ライプニッツ

『素粒子』精霊主義

『クオリア』アストラル体

『考える葦』パスカル メンタル体

『精神と物質』デカルト 物心論

『宇宙四次元』アインシュタイン

『時間と空間』ニュートン

『物自体』カント

『質料』プラトン

『弁証法』ソクラテス

『形相』アリストテレス

ライヒ『オルゴンエネルギー』

シュタイナー『エーテル体』光子

ユング『集合的無意識ー幻型』

フロイト『リビドーと超自我』

アドラー『目的論』

ニーチェ『永劫回帰』

ハイデッカー『存在と時間』

サルトル『存在と無』

ラカン『想像界・象徴界・現実界』

キリスト『三位一体』

盤古『陰陽』

ヴント『内観』

プロティヌス『一者』

エンペドクレス『風・火・地・水』

デモクリトス『原子』

チェリオ『量子色力学』

ジョブズ『Apple製品』

ダリ『心理学から科学へ』

モーツァルト『曖昧な調和』

小室哲哉『宇宙の美化』

坂本龍一『現実』

小林武史『夢と魔法』

宇多田ヒカル『宝瓶宮の水』

植松伸夫『劇場音楽』

天野喜孝『ファイナル・ファンタジー』

楠瀬誠志郎『シリウス』

すぎやまこういち『ドラゴンクエスト』

鳥山明『ドラゴンボール』

高橋留美子『めぞん一刻』『犬夜叉』

桂正和『DNA』『シャドウ・レディー』

貞本義行『エヴァンゲリオン』

宮崎駿『ロマン派』

久石譲『映画音楽』

スピノザ『心身一元論』

クリシュナムルティ『私は何も信じない』

キリスト・マイトレーヤ『分かち合って世界を救いなさい』

ベンジャミン・クレーム『始まりは近い』

江原啓之『オーラの泉』

大槻教授『プラズマ』

韮澤さん『たま出版』

イエス覚者『救世主』

仏陀『真我』

プレマ・サイ『超心理学』

フェルメール『レースを編む女』

3ー7ー4ー2ー7(2.4)

宇宙

針仕事の周りを描く『フェルメール』の絵の中に宇宙が回っている事を、夢と現実の間を行ったり来たりするシュールで、冗談好きの地獄ではないまでも煉獄に居る『ダリ』は知っていた。如何なる小さな物事でも、大切な人の存在は守りたい。大切な命に寄り添い生きていきたいものである。

『来世』

サルバドール・ダリ『レース編みの娘』

6ー4ー6ー4ー7(1.6)

(フェルメール・ファン・デルフトの絵の模写)

「ダリ全画集」の『レースを編む女』

ダリに心の底から同情します。イニシエートの低さには右利きで頭の精神の線が細いスマートと云う理由と、光線構造が非常に高いのには、人類の輪廻転生を担保したいのと、神であるサルバドール(救世主)でありたいと言う野心と、謙遜と、拘りがあるからですー。

芸術家と科学者

『ピカソ』は拘りのない自由な心の境地でどんな画家のスタイルも直ぐにマスターして、同じ場所に留まらずにどんどん変化する秀才。純粋無垢な子どもが描いた様な平気で、破壊的な創造で醜悪さをも描く。『ダリ』は古典的な描き方で言語性の強い鬼才。神に見いだされた犠牲者ですー。

ダリでもピカソ

二人ともきら星のような才能があるので何回輪廻しても本物の神になるべきです。業の深さは恐ろしくダンテの言葉を借りれば「まるで生きていることが呪われている様でこの地上以外に如何に『地獄』と呼ぶ事ができようか?」と言う程、人生を生きるのは大変です。才能の有無に関わらず。

パブロ・ピカソ(2.4)

7ー4ー1ー6ー3

『サルタンバンカの一家』

パブロ・ピカソ『パイプを持つ少年』

アンリ・マチス(2.4)

3ー6ー1ー4ー7

『ブルーヌード』

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

『貴様』のように敬意が減り続けた結果、相手を挑発するような失礼な言葉になってしまう、これを『敬意逓減の法則』といいます。『奥さん』は今でも尊敬語として使われている一方で、謙譲語の役割まで担ってきているのは、時代とともに敬意そのものが低減してきたからでしょう」

「奥さん」呼びは時代遅れ…じゃあ「妻さん」と呼ぶの? 言語学者が提案する既婚女性の“新しい呼び方”とは?<11月22日いい夫婦の日> | 集英社オンライン | 毎日が、あたらしい

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

目上に失礼な語と言う人がいるが、以前から『了解いたしました』など、丁重表現として使われる。 『承知しました』は丁重な表現だが、『了解しました』は ふつうの丁寧表現。ただし、『了解いたしました』と言えば、じゅうぶん丁重な表現になる。『承知いたしました』は より丁重な表現。 『了解しました』は丁寧語で、これで意味は十分伝わります。『承知しました』になると、謙譲の意味を含みますから、相手を尊重しているような姿勢が伝わる言葉となります。

「了解です」はいつから「失礼だから使うな」となった? 代わりに「承知しました」は本当に正しいのか(J-CASTニュース) - Yahoo!ニュース

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

「Can You Catch A Cold?」サンプル5

字幕大王2024.06.25

サンプル4はこちら

水俣病の混乱

細菌論に夢中だったために伝染病と間違われた病気は栄養不足��けではない。1956年5月のこと、5歳の少女が日本の水俣市の病院に入院した。水俣は八代海に面した人口約5万人の小さな漁村だった。その少女は、けいれん、歩行困難、言語障害などの異常な神経症状を呈し、急速に体調を崩していた。数日後、彼女の妹と町内の他の3人もまったく同じ症状で病院を訪れた[45,46]。

その後、数週間から数ヶ月で、村の人々が病気になるケースが急増したが、罹患したのは村人だけではなかった。大量の魚が奇妙な泳ぎ方になり、やがて死んで陸に打ち上げられた。海鳥は飛べなくなり、異常な行動をとるようになった。これらの動物を捕食する猫も具合が悪くなり、口からよだれを垂らし、気が狂ったかのようにぐるぐる走り回った[47]。動物と人間の間で何らかの病原体が伝播したのだろうか。誰も確かなことはわからないが、この大流行は伝染病の特徴をすべて備えているように思われた。最初の患者が出た後、村に住む人々が次々と同じ症状で倒れ始めたのだ。そのため、ある種の「奇妙な伝染病」が発生したという噂が広まった[48]。やがて、この病気は伝染性髄膜炎であるという未確認の報道が出始め、地域社会は大きなパニックに陥ったのである[49]。

謎の病気への恐怖は極めて大きく、近隣の町の人々は水俣人を排斥し始め、長い間築かれてきた密接なコミュニティの絆は急速に失われていった[50]。伝染病まん延を抑えるため、家屋は消毒され、病人は隔離された[49]。この対策にもかかわらず、伝染病が地域住民を襲い続けた。初期の報道によれば、少なくとも55人が感染し、17人が死亡した[45]。

しかし、約3年後、研究グループはついに病気の原因が地元の肥料製造会社であると突き止めた。同社が、合成肥料製造の廃棄物であるメチル水銀27トンを水俣湾に投棄していたのだ[51]。この水銀が地元の水路を汚し、何百平方キロメートルもの海を汚染した。かつては美しく肥沃な自然の珊瑚礁であった水俣湾は、有毒な荒れ地となり、かつては豊かであったその恵みを不運にも口にした人間や動物を毒した。

1963年2月、水俣病の発生原因を調査していた研究グループから正式な発表があった。誰もが落胆したが、水俣病の原因は感染性微生物ではなく、メチル水銀に汚染された水俣湾の魚介類の摂取によるものだった[49]。長年にわたって、この環境破壊の犠牲者たちは、日常生活で出会う人々に伝染性ではないと安心させねばならなかった[52]。この災害によって900人以上が死亡し、200万人が慢性的な健康被害に苦しんだ[51]。

水銀中毒の混乱

水俣で起きた出来事にもかかわらず、医療関係者は今日に至るまで、水銀中毒を感染症として誤って診断している。2018年8月のこと、15歳女性、13歳女性、11歳男性の3人兄弟が救急外来を受診した。彼らには、発熱、筋肉痛、皮疹、倦怠感など、非特異的な症状が進行していた。検査は陰性の連続であり、その結果、「ウイルス性症候群」と診断された。子供たちは休ませるために家に帰らせられたが、その3日後、兄弟はさらに悪化した状態で救急部に戻ってきた。うち一人は神経障害を起こしていた。子供たちは溶連菌性咽頭炎(連鎖球菌性咽頭炎)と猩紅熱(しょうこうねつ)と診断された。彼らには抗生物質が投与されて退院した[53]。

その数日後、子供たちはセカンドオピニオンのために別の救急外来を受診した。この時までに、症状はかなり悪化しており、激しい頭痛、息切れ、手足のしびれ、全身の脱力感などが生じていた。結論に飛びついてウイルスやバクテリアのせいにするのではなく、救急医たちはさらに詳しく調べた。すると、子供たちが自宅で水銀の瓶で遊んでいて、それがカーペットにこぼれていたことがわかった。母親はこぼれた水銀を掃除しようとして掃除機を使った。母親はそうとは知らず、これが水銀を加熱・気化させて、子供たちはうっかり吸い込んでしまったのだ。不思議なことに、母親には何の症状も現れなかったので、この病気は小児感染症のように思われたのだ。

子供たちが水銀中毒であることを知った医師たちは、水銀除去のためにキレーション療法を開始した。二人の子供は完全に回復したが、1人は関節、背中、筋肉の痛みが続き、歩行器が必要になった。この出来事はケーススタディとして記録され、2020年2月の医学雑誌に掲載された。著者の結論としては、水銀中毒が感染症に似ている可能性があることだ[53]。子供たちは同じ家で暮らしており、似たような症状を呈していたため、最初の病院の医師は、小児期の伝染病が兄弟間で広がったに違いないと誤って考えたのだ。ここでもまた、一面的なレンズを通して世界を見ることが誤った思い込みを招き、正しい診断と治療を遅らせたのである。

なぜこれが重要なのか?

壊血病、ペラグラ、水銀中毒といった病気の原因を正しく特定することが重要だったことは明らかだ。しかし、いずれの場合も、細菌論というレンズが真実を邪魔し、調査者を無益な捜索に向かわせ、一般大衆を無用なパニックに陥れた。これらの事例だけを見ても、間違った説明モデルを適用したことによる影響を定量化するのは難しい。数え切れないほどの資源、時間、人命が、存在もしない敵と戦い、追いかけて失われたのだ。また、どれだけの人々が仲間はずれにされ、孤立し、非人道的な扱いを受け、タイムリーで効果的な医療を拒否されたかを考えると胸が痛む。それは伝染病だからではなく、伝染病であることを恐れたからである。このように、我々が世界を見るレンズは強力だ。良くも悪くも、レンズは我々のあらゆる知覚を彩り、我々の見方に一致する結果をもたらす。

もちろん、今では良くわかっており、これらの病気を伝染病と見なすことはない。壊血病、ペラグラ、水俣病のような病気を振り返り、その過ちに気づくのは簡単なことだ。現在の我々から見れば、人間がハンセン病患者のような烙印を押され、治療を拒否され、檻に入れられた動物のように閉じ込められていたのは野蛮なことのように思える。後知恵とはおかしなものだ。我々は今、すべての答えを持っていると思い込んでいる。しかし、我々がいまだに伝染病だと考えているが、そうでない病気が他にもあるとしたらどうだろう?ここまで来たと誇らしげに振り返っても、まだ同じ過ちを犯しているかもしれない。プライドと甘さに目がくらみ、過ちを犯し続けていることに気づかないまま、我々は突き進むのだ。

今にして思えば、過去の研究者の一部が傲慢でなく、型にはまっていなかったのは幸運だった。彼らは謙虚であり続け、心をオープンにし、勇気を持って行動した。もし彼らが、受け入れられているパラダイムに挑戦しようと思わなかったら、今日の世界はどうなっていただろう?我々はまだそれらの病気を伝染病とみなし、かつてと同じ非効率的で非人道的な治療法を続けていたかもしれない。単純な食生活改善の代わりに、重金属を注射し、ペラグラのために隔離されることを想像してみてほしい。壊血病や脚気、くる病に他人から感染することを恐れて暮らすことを想像してみてほしい。おそらく我々は、ワクチン接種、手洗い、社会的距離、抗生物質、抗ウイルス薬、マスク、ロックダウンといった現代的な方法で、これらの(存在しない)細菌から身を守ろうとするだろう。そのあいだ、人々はライフスタイルや環境によって不必要に死に続けるのだ。そういった想像は難しくはない。例えば風邪やインフルエンザなど、他多くの病気についても、今日の世界はこのような方法で対処しているからだ。ただひとつ違うのは、現代の研究者たちが、伝染病モデルによってこれらの病気を正確に説明できると信じてこんでいることだ。この信念は現在、集団心理に深く刻み込まれており、間違いの可能性を受け入れるのは難しい。文化もまた変化しており、受け入れられているパラダイムに異議を唱える者は、狂った陰謀論者のレッテルを貼られる。

我々はあまりに自身を確信しすぎてしまっている。しかし、本章で示すことは、結果を観察して原因を誤って帰することが、いかに物事を間違えやすいかである。また、結論を急ぐのではなく、厳密に管理された(controlled)科学実験によって因果関係を確認することがいかに重要であるかを強調している。我々は過去にも過ちを犯したし、因果関係を正しく理解しなければ、我々自身がどれほど進歩していると考えていようと、過ちを犯し続けるだろう。誤った例が強調しているように、病気を伝染病と誤って診断することは、あらゆる種類の悪影響をもたらす。病人にとっては、適切な診断や治療へのアクセスが遅れ、より深刻な機能障害や身体障害につながる可能性がある。総合的には、これは広範囲に及ぶ影響をもたらす。実際、病気の原因を伝染病と混同してしまえば、より恐れを抱く回避的な社会が培われ、資源の配分を誤り(研究助成金など)、誤った経済(医薬品など)を支え、組織(政府など)に権力を譲り渡し、誤った道を進む間に、より多くの人々が病気になり、命を落とすという機会損失を最終的には被ることになる。

サンプル6はこちら

「Can You Catch A Cold?」サンプル5 | 字幕大王

3 notes

·

View notes