#Chrome Net Internals DNS Tool

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

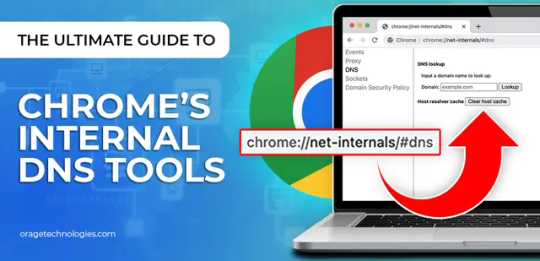

Chrome Net Internals DNS Tool – Complete 2025 Guide to Clear DNS Cache

If websites are taking forever to load or you're getting annoying error messages in Google Chrome, your DNS cache might be to blame. One of the fastest ways to fix this issue is by using the Chrome Net Internals DNS Tool. This powerful built-in Chrome feature helps clear outdated or corrupted DNS entries that may be slowing down your browsing. In this 2025 step-by-step guide, we’ll show you exactly how to use the Chrome Net Internals DNS Tool to clear your DNS cache quickly and effectively—complete with screenshots and expert tips.

Say goodbye to frustrating browser delays and connection problems with this simple fix!

0 notes

Text

How Chrome DNS Cache Interacts with VPN and Proxy Settings

If you ever have used VPN or proxy service while surfing the internet, you may have noticed sometimes that the websites still load up from their original locations or somehow redirect unexpectedly. The reason behind this could be lurking in the browser's DNS cache. Specifically, in Google Chrome, the Chrome Net Internals DNS tool provides a unique window into how cached DNS data works — especially when paired with VPNs and proxy servers.

Let's deconstruct it all here in this tutorial, delving into how DNS caching operates, how it gets along with VPNs/proxies, and how to properly control it using Chrome Net Internals DNS in 2025.

What Is DNS Caching in Chrome? DNS (Domain Name System) works like the internet phonebook — converting domain names (such as example.com) into IP addresses your computer can use. To preserve time, your browser caches these lookups temporarily in what's a DNS cache.

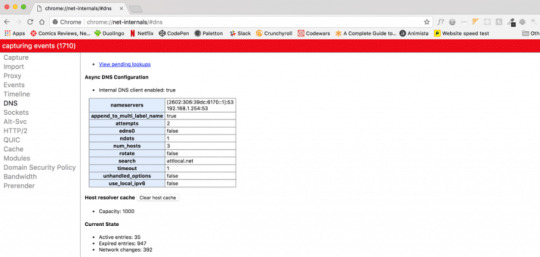

In Google Chrome, the browsing cache can be tracked and controlled via the Chrome Net Internals DNS page. Using this tool will allow you to list the DNS entries in the cache, track DNS history, and eventually flush the DNS cache when necessary.

What happens when you use a VPN or proxy? A VPN or a proxy server redirects your internet traffic to another server, hiding your original IP address and location. Still, even with the traffic stream redirected through a VPN or proxy, your browser could use an old DNS cache, so websites might resolve to the old IP instead of the new route, and region-locked content might not come in.

Some websites may load slowly or incorrectly.

This is where the Chrome Net Internals DNS tool becomes critical. It helps clear out outdated DNS entries that are no longer valid when you're switching between VPNs, proxy servers, or even networks.

Why DNS Cache and VPN/Proxy Settings Can Clash Here’s why the combination of DNS caching and VPN/proxy settings can be problematic:

Cached IPs Don't Match VPN Routing When you go to a site without booting up a VPN, Chrome stores its DNS record on your local network. But when you enable a VPN, the path is altered — and the DNS entry may no longer be valid. This inconsistency can lead to problems or forward you to the wrong versions of the site.

Proxy Servers May Not Force a Fresh DNS Lookup Not all proxies override local DNS lookups. That means Chrome may still use its old cache unless you go into the Chrome Net Internals DNS interface and manually clear it.

Privacy Leaks A stale DNS cache may leak your actual location or ISP to websites even when you seem to be using a VPN. This defeats one of the main reasons for privacy-focused browsing.

How to Clear DNS Cache with Chrome Net Internals DNS (2025) To ensure your VPN or proxy works properly with Chrome, it’s a good idea to clear the DNS cache. Here’s how you do it using the Chrome Net Internals DNS tool:

✅ Step-by-Step Guide: Open Google Chrome.

In the address bar, type: chrome://net-internals/#dns Press Enter.

You’ll land on the Chrome Net Internals DNS dashboard.

Click the “Clear host cache” button.

Boom! Chrome now clears your DNS cache. Any time you go to a website from now on, Chrome is going to automatically resolve the domain name via your VPN or proxy, rather than your previous network configuration:

Optional: Flush Sockets for Even More Clean-Up Sometimes, active connections might still be using outdated network data. To flush even deeper: chrome://net-internals/#sockets Click "Flush socket pools." This fully cleans your network connections and re-establishes all of them through your current VPN or proxy route.

Best Practices When Using VPN or Proxy with Chrome To prevent problems, the following are a couple of best practices:

Always clear the DNS cache using Chrome Net Internals DNS when going online or offline with a VPN.

Reboot your browser to terminate any long-lived connections that won't reset automatically.

Use safe DNS settings (such as Cloudflare or Google DNS) if you're not depending on the DNS provider of your VPN.

Try setting Chrome to always use secure DNS over HTTPS (in Chrome settings).

Real-World Use Case Let's say you're a digital marketer and are trying to see how your site looks in various locations. You use a VPN to pretend you're from various places — but no matter how often you switch, the page loads the same. That's likely because Chrome is using cached DNS information.

By purging your DNS cache with Chrome Net Internals DNS, you guarantee your browser fetches new DNS data that corresponds with your new VPN location. It's a little thing that can save you a lot of heartache.

Final Thoughts Browsing the web securely and quickly in 2025 is more crucial than ever before. Though VPNs and proxies keep your privacy intact and allow access to geographically restricted content, they sometimes don't get along well with your browser's DNS cache.

Thankfully, Chrome Net Internals DNS gives you control over such matters. Flushing the DNS cache every time you switch networks or VPN routes will ensure you always browse in accuracy, in privacy, and in severance.

Next time you feel things "just" aren't "quite" right about using a VPN in Chrome, just recall: open up Chrome Net Internals DNS, hit that "Clear host cache" button, and you're good to go.

#Chrome Net Internals DNS#flush DNS cache#DNS lookup#Chrome browser tools#fix DNS errors#VPN browsing fix#browser speed boost#network troubleshooting#clear host cache#Chrome DNS 2025#web troubleshooting#Google Chrome tools

0 notes

Text

Resolve Slow Browsing with Chrome-Net-Internals-DNS: Here’s How (2025)

Why Your Internet Might Be Sluggish

Is it taking an eternity to load a website or it's not opening at all? Before blaming your internet connection, consider clearing your DNS cache using a little-known hidden tool that Chrome has called chrome-net-internals-dns.

This is one of the easiest ways to speed up your browser and eliminate irritating connection failures—without downloading additional software.

Browsing Issues in 2025 Are More Common Than You Think

As of 2025, issues around browsing a website are more common than ever because the browser you may be using could have a stale or corrupted DNS entry cached.

Don't be surprised! DNS is designed to simplify your surfing behavior, but sometimes things get confusing, and the browser is simply protecting you from clicking something crazy.

What is Chrome-Net-Internals-DNS and How It Works

In Google Chrome, you can check, manage and flush your DNS cache using the built-in tool located at chrome://net-internals/#dns.

This guide will cover everything you need to know about chrome-net-internals-dns, including:

What it is

How it works

Step-by-step instructions for both desktop and mobile

We’ve also included how to clear socket pools to fix recurring issues related to unstable connections or failed loading.

Advanced Methods Beyond Chrome-Net-Internals-DNS

If you tried clearing the cache but still have no relief, do not worry. We provide advanced methods for:

Flushing DNS on Windows, macOS, and Linux

Resetting Chrome flags

Changing your DNS provider to Google DNS or Cloudflare DNS

Troubleshooting Common DNS Problems

Also included is a list of general DNS problems and how to troubleshoot them effectively.

Whether you’re a casual user or a tech-savvy browser, learning to use chrome-net-internals-dns can greatly enhance your browsing experience.

Take Full Control of Chrome’s DNS Settings

Don't accept a slow internet or broken sites without discovering how to optimize Chrome like a pro!

Read the full guide now and take control of your DNS settings today using chrome-net-internals-dns!

#Chrome Net Internals DNS#chrome-net-internals-dns#clear DNS cache#speed up Chrome#DNS fix 2025#network troubleshooting#Chrome flush DNS

0 notes

Text

Chrome Net Internals DNS Tool – Complete 2025 Guide to Clear DNS Cache https://oragetechnologies.com/chrome-net-internals-dns/

0 notes

Text

How to Use Chrome’s Net Internals DNS Tool on Mobile Devices for Better Network Management

Chrome’s chrome://net-internals/dns tool is an invaluable feature for diagnosing and managing DNS settings, especially when facing connectivity issues. While most users know this tool on desktops, it’s equally beneficial on mobile devices. In this article, we'll cover how to use chrome://net-internals/dns on mobile devices, why it’s helpful for DNS troubleshooting, and tips to optimize Chrome's performance on Android and iOS.

What is chrome://net-internals/dns?

1.1 Understanding Chrome’s Net Internals Tool

1.2 The Importance of DNS Caching and Flushing

How to Access chrome://net-internals/dns on Mobile

2.1 Compatibility on Android and iOS

2.2 Step-by-Step Guide to Using Net Internals DNS on Mobile

2.3 Troubleshooting Common Access Issues

Why Clear DNS Cache on Mobile Devices?

3.1 Benefits of Clearing DNS Cache for Network Performance

3.2 How DNS Cache Affects Page Loading Speeds and Connectivity

Best Practices for Using Chrome’s DNS Tool on Mobile

4.1 Optimizing Chrome’s Network Performance with DNS Settings

4.2 Regular Maintenance Tips for Better Browsing on Mobile

Key Differences Between Desktop and Mobile Chrome DNS Management

5.1 Accessing Advanced Chrome Features on Mobile

5.2 Limitations and Workarounds for Mobile Devices

FAQs

Q1. What is the purpose of chrome://net-internals/dns? chrome://net-internals/dns is a Chrome feature that allows users to view and manage DNS settings, clear DNS cache, and troubleshoot connectivity issues, offering more control over their network performance.

Q2. Can I use chrome://net-internals/dns on Android and iOS? Yes, you can access this feature on Android. However, it’s more limited on iOS due to system restrictions.

Q3. Why would I need to clear my DNS cache? Clearing DNS cache can help resolve connectivity issues, speed up browsing, and ensure the latest DNS records are used, especially after changing network settings.

Q4. How often should I clear the DNS cache on Chrome mobile? Clearing the DNS cache periodically can help maintain optimal network performance. Doing it once a month or when facing connectivity issues is generally sufficient.

Conclusion

The chrome://net-internals/dns tool in Chrome is a powerful feature for mobile users to improve their network performance by managing DNS settings. Although primarily used on desktop, this tool can also be accessed on Android devices, allowing users to troubleshoot and optimize browsing speed effectively. By understanding how to access and utilize Chrome's Net Internals DNS tool on mobile, you can keep your connection stable, reduce load times, and avoid common browsing interruptions.

#technology#advanced technologies#google#chrome#internet#online work#dns#tools#ai tools#technews#technically

0 notes

Text

#chrome.//net-internals/dns#chrome //net-internals/#dns#chrome://net-internals/#dns clear#www.chrome //net-internals/

0 notes

Text

Always Clear Downloads Chrome

Always Clear Downloads Chrome Cache

Always Clear Downloads Chrome

In general, Google Chrome will store the webpages you have browsed into your computer. Such files, we called cache. When you go back to visit a website for twice, Google Chrome always extract the original content from the cache, instead of downloading it from the Internet. However, the cache can also slow your browser down if you don't clean it up. To solve the problem, we will show you how to clear or disable Chrome cache manually on Windows 10.

Part 1: Clear Chrome Cache Manually on Windows 10

Always Clear Downloads is a free to use browser tool that helps people automatically clean their browser’s downloading history. The tool comes as a browser extension for Google Chrome. After you have installed the extension, a new icon is placed in the browser’s address bar.

When a webpage update, the old cache won‘t work anymore. Clear cache and download anew to prevent your browser from delaying. To renew the data, we provide three ways to clear Chrome cache step by step.

At the top right, click More Downloads. To open a file, click its name. It will open in your computer's default application for the file type. To remove a download from your history, to the right of the file, click Remove. The file will be removed from your Downloads page on Chrome, not from your computer. Download an edited PDF. Always Clear Downloads. This extensions fixes the original Always Clear Downloads that can no longer be installed since Google discontinued support for extensions using manifest.json version 1. Version 2.1 - This version modernizes the code to use the most recent Chrome APIs. Should also prevent the extension from going inactive. Follow the steps below to make Google Chrome Automatically clear browsing history when you exit the Chrome Browser. Open Google Chrome Browser on your Mac or Windows Computer. Click on the 3-dots menu icon and select Settings option in the drop-down menu.

Way 1: Clear Chrome cache in 'Clear browsing data' page

Step 1: Open Chrome, click on 'More' icon at the top-right and select More tools> Clear browsing data.

Tips: You can also go to the Clear browsing data page by using Ctrl+ Shift+ Delete shortcut.

Step 2: In the Clear browsing data window, click the Down arrow to select the beginning of time. Check Cached images and files box, and then tap on CLEAR BROWSER DATA button.

Way 2: Clear Chrome cache by changing the system hosts

Step 1: In the address bar, input 'chrome://net-internals/#dns' and Enter.

Step 2: In the capturing events page, tap on the Down arrow at the top-right corner then click on the Clear cache and Flush sockets. Click on Clear host cache button.

Part 2: Disable Chrome Cache Manually on Windows 10

Considering the safety of your account information, you need to disable Chrome cache when you use a public computer. Follow the two steps below to disable cache easily.

Always Clear Downloads Chrome Cache

Clear Chrome cache through 'Developer tools' option

Step 1: Click on More icon, choose 'More tools' from the list and then select Developer tools.

Tips: You can use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+ Shift+ I directly.

Always Clear Downloads Chrome

Step 2: There will pop up a window to the right of the page. Click on Network tab and tick the Disable cache box.

Related Articles:

1 note

·

View note

Link

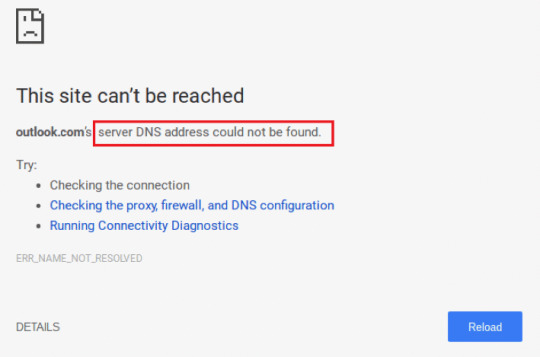

Err… “DNS server could not be found” errors are most common when you try to visit some websites on Google Chrome. Don’t worry! You are not alone here!

More than 80% of internet users may have faced the issue with “DNS server could not be found” message which occurs when the Domain Name Server is not available.

So, why do we call it Unavailable?

There are a few possibilities that one of three things causing the error to pop up every time you try to reach some websites.

Either, the DNS address is not configured properly in your PC or it’s Invalid

The server at the address might be defective for some reason.

Or, it happens that the address is unreachable.

Without having more information about the particular “DNS server could not be found” error. We only assume the following methods mentioned in this article may help you to get rid of the disaster.

For instance, when you visit some websites the first that happens in the backend is the browser contacts the DNS server. Henceforth, the DNS lookup gets failed which results in nasty “DNS server could not be found” error messages.

When you pay a visit to a website, of course the website know about your visit but do you know you are also observable by the third party trackers used by the website.

You may be surprised to know that the majority of websites uses third-party trackers in order to collect information of the users such as geographical location, devices used to view the website and so on.

Although these trackers are somehow responsible for taking out your personal information. Moreover, these trackers cover millions of websites and the company behind them create massive data by combining data trackers collects from each site.

Now, you must be thinking why should we tell you that?

Unlike every other website you pay a visit, it keeps all your sessions during the visits. This is done through the use of “Cookies”. Although Google Chrome allows most of the website to load trackers or a few websites asks the user consent before it uses the cookies.

The “DNS server could not be found” issue might arise from here. This is due to because most trackers do not have an effective mechanism to opt out, therefore, when you visit a website that blocks the trackers and third-party trackers will eventually get blocked showing you “DNS server could not be found “errors.

Look at the below screenshot to know what we’re talking about.

In this article, we’ll find the fixes to the problems so that you do not have to worry about the “DNS server could not be found” again.

Or, there are two possible reasons

The DNS server is working but network connection can’t reach it

The DNS server is not working even if your network can reach it

If it happens to be any one of the following then, there might be a physical problem with the network, even a software problem with the interface causing this. A configuration problem with the network or a firewall blocking access.

Usually, you need to check the network configuration and later check the automatic repair function by clicking at the network icon.

If it isn’t helpful. Please read the entire post for resolving the “DNS server could not be found” error in a more advanced way.

Ensure you have updated the drivers

The reason why you are seeing “DNS server could not be found” error messages on your browser is due to the incorrect, outdated or corrupt drivers. Ensure that you have the latest driver installed in your system.

Manual driver update

In order to manually update your drivers, visit your hardware manufacturers website and search for the most updated version from the list. If you have a problem finding the correct drivers then, you can simply contact the manufacturers and get everything you need.

Automatic driver update

You can find tons of the easy to use automatic driver updater tool that scans your Pc and download the missing or outdated drivers for you. This is defiantly a better option for them who are not willing to download each driver. Plus, most of them you find them on the web are free!

Clear Chrome’s Host Cache

Apart from outdated driver issues chrome host cache corruption will prevent you from accessing the websites. Though you can make an easy fix to it you will need to follow some steps.

Step 1 Open Google chrome type in an address bar “chrome://net-internals/#dns

Step 2 Now press the enter key and message will be displayed on the screen stating something below in the screenshot.

Step 3 Now you need to click at the button saying “Clear host cache” next to host resolver cache.

Step 5 Assuming that you have completed the above steps now refresh the page and see if the issues are still persisting.

Delete the files in your ‘etc’ folder

Though this is another fix to the “DNS address could not be found” issue. Follow the below steps to make a fix to it.

Step 1 Browse through your ‘etc’ folder found in C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc.

Step 2 Once you have found the exact folder. Attempt to delete all the files in it.

Step 3 Ensure that Google Chrome is closed down before performing the operation

Step 4 Now, open the Google chrome after you have finished with the following steps.

Step 5 Check the websites to see if the problem is resolved or not.

More Findings

If the error messages appear stating the “DNS address could not be found” means the browser is not able to find the Domain Name System. There is a lot of fix to it such as changing your DNS server.

The issue to “Server DNS address could not be found—3300” is due to the misconfiguration. In order to make a fix to this. Follow the below steps.

Step 1 Press the Windows logo + R (for the run command) from the keyboard.

Step 2 Go to the control panel

Step 3 Select the “Network and Sharing Center”

Step 4 Click on “Change adapter settings” from the left side of the screen.

Step 5 Right-click on the Local Area or Wireless Network Connection icon and Visit the properties.

Step 6 Now, you will come to know about the list of connection is using.

Step 7 Click on the “Internet Protocol Version 4” (TCP/IPv4)

Step 8 Once selected ‘Click on the properties” button.

Step 9 You will get a “General tab” then

Step 10 If “obtain DNS server Address automatically is not selected” then, check the box to select it. And click on the “Ok” button.

In case, if it is already selected then, select to use the following DNS server address instead and click on done.

Note: The Preferred DNS server should contain 8.8.8.8 along with than the Alternate DNS server should be 8.8.4.4

Know how to renew and clear your DNS

If you use a windows computer, windows stores the IP address of the websites you pay a visit. This is done for faster loading of the website you visit more frequently. The cache present is either corrupt or outdated but you can renew and clear it using the following steps mentioned below.

Step 1 Press the Windows + R key to bring out the Run box. Now, open “Command Prompt” using the combination of keys CTRL + SHIFT + Enter to open the command prompt in administrator mode.

Step 2 It may look a little tricky especially for non-tech savvy users but here, you have to type in ipconfig /flushdsns and hit the “Enter” key. This will allow wiping out the cache if it’s outdated or corrupt.

Step 3 Well, you’re done with flushing the DNS. Reboot the system in order to see the new affected changes.

Make use of a VPN (Virtual Private Network)

If you still have the server DNS addresses could not be found the error with some websites then, download and use a VPN service to resolve the issue. It is done to make access to some website forbidden by your ISP (Internet Service Provider).

If you are not sure which VPS service you should choose, you can always go for NordVPN used by millions of users on the web to make access to the blocked websites from the ISPs.

FAQs: –

What does it mean when you have a DNS error?

DNS error refers to as the connection to the network or internet access has been abandoned. Usually it the DNS error depicts that it is unable to look up the IP address for the domain you are accessing.

How do you fix a DNS error?

Flushing the DNS cache is the best solution to make a fix to the DNS error. If you are not sure how to do it. Please refer to the steps mentioned in the article.

What is a DNS address error?

DNS refers to the Domain Name System that translates the website address into IP address to connect. The DNS address error might be occurring due to DNS cache. Although flushing it using the command prompt may help. Or it could be the issue arising from your ISP. One possibility is that you’re trying to access an already downed server.

The post DNS server could not be found appeared first on Letohost.

https://ift.tt/2LTeul3

1 note

·

View note

Text

Google Chrome error ERR_SPDY_PROTOCOL_ERROR - FIX

If you've stumbled upon this post it probably means you're experiencing this odd error from Google Chrome:

This site can't be reached The webpage at https://example.com/ might be temporarily down or it may have moved permanently to a new web address. ERR_SPDY_PROTOCOL_ERROR

SPDY Protocol

As you might already know, SPDY (pronounced "speedy") is a deprecated open-specification networking protocol developed by Google for transporting web content - more specifically, to help load web pages more quickly. To obtain this performance gain, the SPDY protocol manipulates HTTP traffic to speed up the web page load latency - using compression protocols, multiplexing and prioritization strategies - and also (supposedly) improving web security. The development of SPDY started in 2012 and was implemented in Google Chrome (and other browser) shortly after. The protocol was eventually set to "deprecated" by Google in February 2015, when the final ratification of the HTTP/2 standard was published. The SPDY support was removed since Google Chrome 51 and Mozilla Firefox 50. Apple has also deprecated the technology in MacOS 10.14.4 and iOS 12.2.

The Solution

Depending on your specific scenario, the issue can either be at server-side (i.e. on the web server hosting the website) or at client-side (i.e. on the browser). In the following paragraph we'll try to address most of the common causes by enumerating the relevant configuration checks and/or changes that should be applied. Needless to say, you can easily determine if it's a client issue or a server issue by testing the issue on multiple machines: if each and every Google Chrome is raising the same exception when trying to load the same identical URL, then it's most likely a server-side issue; conversely, if only one (or a small bunch) of clients are giving such result, you're probably facing a client-side issue. Server-Side checks One of the reasons why you may see the ERR_SPDY_PROTOCOL_ERROR message is an invalid HTTP header coming from the server. Google Chrome applies a strict set of rules when processing HTTP/2 response - for example, is often unable to handle: headers with a space instead of a dash (e.g. Referrer Policy instead of Referrer-Policy); headers with double colon after the key name (e.g. Contenty-Securit-Policy:: instead of Contenty-Securit-Policy:); The first thing to do is to login to your web server machine and check your IIS / NGINX / APACHE service configuration files to ensure that these headers are being sent correctly. Notice that Mozilla Firefox, Safari and other less-strict HTTP/s compatible browsers will almost always ignore any invalid HTTP headers like the above ones, and will just display the page. Client-Side actions If the server-side checks are not applicable in your scenario - or you found no issues there - you should try the following workarounds on your Google Chrome browser. Close/reopen Google Chrome and try to reload the page again. We know that this is rather trivial suggestion, but we just had to give that anyway. Update Google Chrome to the latest version by going to Settings > Help > About Google Chrome. Clear the Google Come cache. You can easily do that by going to Settings > More Tools > Clear Browser Data. When a pop-up menu will show up, select the Advanced tab, check Cookies and other site data and Cached images and files, and clear the cache for good. Temporarily disable your antivirus software. Some AV software are known to interfer with HTTP requests/responses to apply some security countermeasures against malicious websites and/or suspicious HTTP traffic; if you have a firewall software with IPS or other web-based protections, you can try to temporarily disable them as well. Alternatively, if your AV/FW software supports white lists or exceptions, you can leave them ON and temporarily add the offending URL to these lists. Please notice the word "temporarily": you don't have to get rid of your protection tools, it's just quick test to see if they are involved in this specific problem in any way. Clear the Google Chrome DNS Cache. You can do that by typing chrome://net-internals/#dns in your URL address bar: once the DNS settings page has loaded, click the Clear host cache button to clear it. Flush the Google Chrome Socket Pools. You can do that by typing chrome://net-internals/#sockets in your URL address bar: once the DNS settings page has loaded, click the Flush socket pools button to flush them. Flush and renew the Windows DNS Cache. Open an elevated command prompt (right-click -> run as administrator), then type the following commands, one at a time ipconfig /flushdns ipconfig /renew Be sure to try these workarounds one at a time: be sure to reload the offending page after each attempt to see if the problem persists.

Conclusion

That's it, at least for now: we sincerely hope that these workarounds will help you fix the ERR_SPDY_PROTOCOL_ERROR Google Chrome error: happy surfing! Read the full article

0 notes

Text

The Answer why Chome communicates behind your back without user consent

The Answer why Chome communicates behind your back without user consent

First of all, it’s not only Chrome which has some background connections but I decided to mention Chrome in this article because some guys constantly telling me that Google is trying to observe the Browser or even worse some people say ‘it’s spying’ in order to steal your data. Chrome’s own net-internals tools can reveal what’s going on a simple visit on motherboard.vice.com reveals what DNS…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

RisingStack in 2019 - Achievements, Highlights and Blogposts.

🎄 How was 2019 at RisingStack? 🥳 - you might ask, as a kind reader already did it in a comment under our wrap-up of 2018.

Well, it was an intensive year with a lot of new challenges and major events in the life of our team!

Just to quickly sum it up:

We grew our team to 16! All of our engineers are full-stack in the sense that we can confidently handle front-end, back-end, and operations tasks as well - as you'll see from this year's blogpost collection.

We launched our new website, which communicates what we do and capable of more clearly (I hope at least). 🤞 Also, a new design for the blog is coming as well!

This year ~1.250.000 developers (unique users) visited our blog! 🤩

We just surpassed 5.7 million unique readers in total, who generated almost 12 million pageviews so far in the past 5 years.

We have now more than 220 articles on the site - written by our team exclusively.

We had the honor to participate in JSconf Budapest by providing a workshop for attendees on GraphQL and Apollo. 🎓

We delivered a 10-weeks-long online DevOps training for around 100 developers in partnership with HWSW, Hungary's leading tech newspaper.

We kept on organizing local Node.js meetups here in Budapest, with more than 100 attendees for almost every event this year. 🤓

We had the opportunity to work with huge companies like DHL, Canvas (market leader e-learning platform), and Uniqa (insurance corp.).

We met with fantastic people all over the world. We've been in LA, Sarajevo, Amsterdam, Prague, and Helsinki too. 🍻

We moved to a new office in the heart of Budapest!

🤔 Okay, okay... But what about blogging?

Blogging in 2019

You might have noticed that we did not write as much blogposts this year as we did before.

The reason is simple: Fortunately, we had so many new projects and clients that we had very little time to write about what we love and what we do.

Despite our shrinking time for writing blogposts, I think we still created interesting articles that you might learn a thing or two from.

Here's a quick recap from the blog in 2019. You can use this list to navigate.

Stripe 101 for JavaScript Developers

Generating PDF from HTML with Node & Puppeteer

REST in Peace. Long Live GraphQL!

Case Study: Nameserver Issue Investigation

RisingStack Joins the Cloud Native Node.js Project

A Definitive React-Native Guide for React Developers

Design Systems for React Developers

Node.js v12 - New Features You Shouldn't Miss

Building a D3.js Calendar Heatmap

Golang Tutorial for Node.js Developers

How to Deploy a Ceph Storage to Bare Virtual Machines

Update Now! Node.js 8 is Not Supported from 2020.

Great Content from JSConf Budapest 2019

Get Hooked on Classless React

Stripe 101 for JavaScript Developers

Sample app, detailed guidance & best practices to help you get started with Stripe Payments integration as a JavaScript developer.

At RisingStack, we’ve been working with a client from the US healthcare scene who hired us to create a large-scale webshop they can use to sell their products. During the creation of this Stripe based platform, we spent a lot of time with studying the documentation and figuring out the integration. Not because it is hard, but there's a certain amount of Stripe related knowledge that you'll need to internalize.

Read: Stripe Payments Integration 101 for JavaScript Developers

Generating PDF from HTML with Node & Puppeteer

Learn how you can generate a PDF document from a heavily styled React page using Node.js, Puppeteer, headless Chrome, and Docker.

Background: A few months ago, one of the clients of RisingStack asked us to develop a feature where the user would be able to request a React page in PDF format. That page is basically a report/result for patients with data visualization, containing a lot of SVGs. Furthermore, there were some special requests to manipulate the layout and make some rearrangements of the HTML elements. So the PDF should have different styling and additions compared to the original React page.

As the assignment was a bit more complex than what could have been solved with simple CSS rules, we first explored possible implementations. Essentially we found 3 main solutions we describe in this article.

Read: Generating PDF from HTML with Node.js and Puppeteer

REST in Peace. Long Live GraphQL!

As you might already hear about it, we're the organizers of the Node.js Budapest meetup group with around ~1500 members. During an event in February, Peter Czibik delivered a talk about GrahpQL to an audience of about 120 ppl.

It was a highly informative and fun talk, so I recommend you to check it out!

Case Study: Nameserver Issue Investigation

In the following blogpost, we will walk you through how we chased down a DNS resolution issue for one of our clients. Even though the problem at hand was very specific, you might find the steps we took during the investigation useful.

Also, the tools we used might also prove to be helpful in case you'd face something similar in the future. We will also discuss how the Domain Name System (works), so buckle up!

Read the blogpost here: Case Study: Nameserver Issue Investigation using curl, dig+trace & nslookup

RisingStack Joins the Cloud Native Node.js Project

In March 2019, we announced our collaboration with IBM on the Cloud Native JS project, which aims to provide best practices and tools to build and integrate enterprise-grade Cloud Native Node.js applications.

As a first step of contribution to the project, we released an article on CNJS’s blog - titled “How to Build and Deploy a Cloud Native Node.js App in 15 minutes”. In this article we show how you can turn a simple Hello World Node.js app into a Dockerized application running on Kubernetes with all the best-practices applied - using the tools provided by CNJS in the process.

A Definitive React-Native Guide for React Developers

In this series, we cover the basics of React-Native development, compare some ideas with React, and develop a game together. By the end of this tutorial, you’ll become confident with using the built-in components, styling, storing persisting data, animating the UI, and many more.

Part I: Getting Started with React Native - intro, key concepts & setting up our developer environment

Part II: Building our Home Screen - splitting index.js & styles.js, creating the app header, and so on..

Part III: Creating the Main Game Logic + Grid - creating multiple screens, type checking with prop-types, generating our flex grid

Part IV: Bottom Bar & Responsible Layout - also, making our game pausable and adding a way to lose!

Part V: Sound and Animation + persisting data with React-Native AsyncStorage

Design Systems for React Developers

In this post, we provide a brief introduction to design systems and describe the advantages and use-cases for having one. After that, we show Base Web, the React implementation of the Base Design System which helps you build accessible React applications super quickly.

Node.js v12 - New Features You Shouldn't Miss

Node 12 is in LTS since October, and will be maintained until 2022. Here is a list of changes we consider essential to highlight:

V8 updated to version 7.4

Async stack traces arrived

Faster async/await implementation

New JavaScript language features

Performance tweaks & improvements

Progress on Worker threads, N-API

Default HTTP parser switched to llhttp

New experimental “Diagnostic Reports” feature

Read our deep-dive into Node 12 here.

Building a D3.js Calendar Heatmap

In this article, we take a look at StackOverflow’s usage statistics by creating an interactive calendar heatmap using D3.js!

We go through the process of preparing the input data, creating the chart with D3.js, and doing some deductions based on the result.

Read the full article here Building a D3.js Calendar Heatmap. Also, this article has a previous installment called Building Interactive Bar Charts with JavaScript.

Golang Tutorial for Node.js Developers

In case you are a Node.js developer, (like we are at RisingStack) and you are interested in learning Golang, this blogpost is made for you! Throughout this tutorial series, we'll cover the basics of getting started with the Go language, while building an app and exposing it through a REST, GraphQL and GRPC API together.

In the first part of this golang tutorial series, we’re covering:

Golang Setup

net/http with Go

encoding/json

dependency management

build tooling

Read the Golang for Node developers tutorial here.

How to Deploy a Ceph Storage to Bare Virtual Machines

Ceph is a freely available storage platform that implements object storage on a single distributed computer cluster and provides interfaces for object-, block- and file-level storage. Ceph aims primarily for completely distributed operation without a single point of failure. It manages data replication and is generally quite fault-tolerant. As a result of its design, the system is both self-healing and self-managing.

Ceph has loads of benefits and great features, but the main drawback is that you have to host and manage it yourself. In this post, we're checking out two different approaches of deploying Ceph.

Read the article: Deploying Ceph to Bare Virtual Machines

Update Now! Node.js 8 is Not Supported from 2020.

The Node.js 8.x Maintenance LTS cycle will expire on December 31, 2019 - which means that Node 8 won’t get any more updates, bug fixes or security patches. In this article, we’ll discuss how and why you should move to newer, feature-packed, still supported versions.

We’re also going to pinpoint issues you might face during the migration, and potential steps you can take to ensure that everything goes well.

Read the article about updating Node here.

Great Content from JSConf Budapest 2019

JSConf Budapest is a JSConf family member 2-day non-profit community conference about JavaScript in the beautiful Budapest, Hungary. RisingStack participated in the conf for several years as well as we did this September.

In 2019 we delivered a workshop called "High-Performance Microservices with GraphQL and Apollo" as our contribution to the event.

We also collected content you should check out from the conf. Have fun!

Get Hooked on Classless React

Our last meetup in 2019 was centered around React Hooks. What is a hook?

A Hook is a function provided by React, which lets you hook into React features from your functional component. This is exactly what we need to use functional components instead of classes. Hooks will give you all React features without classes.

Hooks make your code more maintainable, they let you reuse stateful logic, and since you are reusing stateful logic, you can avoid the wrapper hull and the component reimplementation.

Check out the prezentation about React Hooks here.

RisingStack in 2020

We're looking forward to the new year with some interesting plans already lined up for Q1:

We'll keep on extending our team to serve new incoming business.

We have several blogposts series in the making, mainly on DevOps topics.

We'll announce an exciting new event we'll co-organize with partners from the US and Finnland soon, so stay tuned!

We're going to release new training agendas around Node, React & GraphQL, as well as a new training calendar with open trainings for 2020.

How was your 2019?

RisingStack in 2019 - Achievements, Highlights and Blogposts. published first on https://koresolpage.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Mastering Chrome Net Internals DNS Tool in 2025: How to Clear Your DNS Cache Like a Pro

Are you struggling with slow-loading websites or outdated domain information in Chrome? It might be time to clear your DNS cache. This complete 2025 guide walks you through the powerful Chrome Net Internals DNS tool, helping you troubleshoot network issues effectively. Learn how to access chrome://net-internals/#dns, flush the DNS cache, and restore faster, more accurate browsing. Whether you’re a casual user or a tech enthusiast, this step-by-step article simplifies the process of managing DNS data in Chrome.

0 notes

Text

mDNS and .local ICE candidates are coming • BlogGeek.me

09/07/2019

One other distuptive WebRTC experiment in Chrome to grow to be reality.

I’ve had shoppers approaching me prior to now month or two with questions about a brand new sort of tackle cropping up in as ICE candidates. Because it so happens, these new candidates have triggered some damaged experiences.

On this article, I’ll attempt to untangle how native ICE candidates work, what is mDNS, how it is utilized in WebRTC, why it breaks WebRTC and how this could have been dealt with better.

How native ICE candidates work in WebRTC?

Earlier than we go into mDNS, let’s start with understanding why we’re headed there with WebRTC.

When making an attempt to attach a session over WebRTC, there are 3 kinds of addresses that a WebRTC shopper tries to negotiate:

Local IP addresses

Public IP addresses, found by way of STUN servers

Public IP addresses, allocated on TURN servers

In the course of the ICE negotiation course of, your browser (or app) will contact its configured STUN and TURN server, asking them for addresses. It should additionally examine with the working system what local IP addresses it has in its disposal.

Why do we’d like an area IP handle?

If both machines that want to connect to one another using WebRTC sit inside the similar personal community, then there’s no need for the communication to go away the local community both.

Why do we’d like a public IP handle by way of STUN?

If the machines are on totally different networks, then by punching a hole by way of the NAT/firewall, we’d have the ability to use the public IP handle that will get allotted to our machine to communicate with the remote peer.

Why do we’d like a public IP handle on a TURN server?

If all else fails, then we have to relay our media via a “third party”. That third celebration is a TURN server.

Local IP addresses as a privateness danger

That a part of sharing local IP addresses? Can actually enhance things in getting calls related.

It’s also one thing that is extensively used and widespread in VoIP providers. The difference although is that VoIP providers that aren’t WebRTC and don’t run within the browsers are a bit more durable to hack or abuse. They have to be put in first.

WebRTC provides net builders “superpowers” in figuring out your local IP tackle. That scares privacy advocates who see this is as a breach of privacy and even gave it the identify “WebRTC Leak”.

A couple of things about that:

Any software operating on your gadget knows your IP handle and can report it again to someone

Only WebRTC (as far as I do know) provides the power to know your local IP addresses in the JavaScript code operating inside the browser (Flash had that additionally, but it is now quite lifeless)

Individuals using VPNs assume the VPNs takes care of that (browsers do supply mechanisms to remove native IP addresses), however they often fail to add WebRTC help properly

Native IP addresses can be used by JavaScript developers for issues like fingerprinting users or deciding if there’s a browser bot or a real human wanting at the page, although there are better ways of doing this stuff

There isn’t a safety danger right here. Simply privateness danger – leaking an area IP handle. How a lot danger does that entail? I don’t actually know

Is WebRTC being abused to reap local IP addresses?

Yes, we’ve recognized that drawback ever because the NY Occasions used a webrtc-based script to collect IP addresses back in 2015. “WebRTC IP leak” is one commonest search terms (search engine optimisation hacking at its greatest).

Fortunately for us, Google is amassing nameless utilization statistics from Chrome, making the knowledge out there by means of a public chromestatus metrics website. We will use that to see what proportion of the page masses WebRTC is used. The numbers are fairly… huge:

RTCPeerConnection calls on % of Chrome page masses (see here)

Presently, Eight% of web page masses create a RTCPeerConnection. 8%. That is quite a bit. We will see two giant will increase, one in early 2018 when 4% of pageloads used RTCPeerConnection and then another leap in November to 8%.

Now that simply means RTCPeerConnection is used. In an effort to collect local IPs the setLocalDescription name is required. There are statistics for this one as properly:

setLocalDescription calls on % of Chrome web page masses (see here)

The numbers here are significantly lower than for the constructor. This means a number of peer connections are constructed however not used. It’s considerably unclear why this happens. We will see a very massive improve in November 2018 to four%, at about the same time that PTC calls jumped to 7-Eight%. Whereas it is senseless, this is what we now have to work with.

Now, WebRTC could possibly be used legitimately to determine a peer-to-peer connection. For that we’d like both setLocalDescription and setRemoteDescription and we’ve statistics for the latter as properly:

setRemoteDescription calls on % of Chrome page masses (see right here)

Because the huge leap in late 2017 (which is explained by a unique method of gathering knowledge) the utilization of setRemoteDescription hovers between zero.03% and zero.04% of pageloads. That’s near 1% of the pages a peer connection is definitely created on.

We will get another concept about how in style WebRTC is from the getUserMedia statistics:

getUserMedia calls on % of Chrome web page masses (see here)

This is persistently round 0.05% of pageloads. A bit more than RTCPeerConnection getting used to truly open a session (that setRemoteDescription graph) however there are use-cases corresponding to taking a photo which do not require WebRTC.

Right here’s what we’ve arrived with, assuming the metrics collection of chromestats reflects real use conduct. We’ve 0.04% of pageloads compared to four%. Assuming the numbers and math is right, then a substantial proportion of the RTCCPeerConnections are probably used for a function aside from what WebRTC was designed for. That may be a drawback that must be solved.

* credit and because of Philipp Hancke for aiding in accumulating and analyzing the chromestats metrics

What’s mDNS?

Switching to a special matter earlier than we return to WebRTC leaks and native IP addresses.

mDNS stands for Multicast DNS. it is outlined in IETF RFC 6762.

mDNS is supposed to cope with having names for machines on native networks without having to register them on DNS servers. This is especially useful when there are no DNS servers you’ll be able to management – consider a home with a few units who have to interact regionally with out going to the web – Chromecast and network printers are some good examples. What we would like is something lightweight that requires no administration to make that magic work.

And how does it work precisely? Similarly to DNS itself, just with none international registration – no DNS server.

At its primary strategy, when a machine needs to know the IP tackle inside the native network of a tool with a given identify (let’s imagine tsahi-laptop), it’ll ship out an mDNS question on a recognized multicast IP handle (actual tackle and stuff might be discovered within the spec) with a request to seek out “tsahi-laptop.local”. There’s a separate registration mechanism whereby units can register their mDNS names on the native network by saying it inside the local network.

Because the request is shipped over a multicast tackle, all machines inside the native network receive it. The machine with that identify (in all probability my laptop, assuming it helps mDNS and is discoverable within the native network), will return back with its IP handle, doing that also over multicast.

That signifies that all machines in the native network heard the response and can now cache that reality – what’s the IP tackle on the local community for a machine referred to as tsahi-laptop.

How is mDNS utilized in WebRTC?

Again to that WebRTC leak and how mDNS may help us.

Why do we’d like native IP addresses? So that periods that have to happen in an area community don’t want to make use of public IP addresses. This makes routing lots easier and environment friendly in such instances.

But we additionally don’t need to share these local IP addresses with the Java Script software operating in the browser. That might be thought-about a breach of privacy.

Which is why mDNS was advised as an answer. There It is a new IETF draft often known as draft-ietf-rtcweb-mdns-ice-candidates-03. The authors behind it? Developers at each Apple and Google.

The rationale for it? Fixing the longstanding grievance about WebRTC leaking out IP addresses. From its summary:

WebRTC purposes gather ICE candidates as a part of the method of creating peer-to-peer connections. To maximise the chance of a direct peer-to-peer connection, shopper personal IP addresses are included on this candidate assortment. Nevertheless, disclosure of these addresses has privacy implications. This document describes a option to share native IP addresses with different shoppers whereas preserving shopper privateness. This is achieved by concealing IP addresses with dynamically generated Multicast DNS (mDNS) names.

How does this work?

Assuming WebRTC needs to share an area IP tackle which it deduces is personal, it’ll use an mDNS tackle for it as an alternative. If there isn’t a mDNS handle for it, it can generate and register a random one with the local community. That random mDNS identify will then be used as a alternative of the native IP handle in all SDP and ICE message negotiations.

The outcome?

The local IP handle isn’t exposed to the Java Script code of the appliance. The receiver of such an mDNS tackle can carry out a lookup on his native network and deduce the local IP tackle from there provided that the gadget is inside the similar local network

A constructive aspect effect is that now, the local IP handle isn’t uncovered to media, signaling and other servers both. Just the mDNS identify is understood to them. This reduces the level of belief wanted to attach two units by way of WebRTC even additional

Why this breaks WebRTC purposes?

Right here’s the rub though. mDNS breaks some WebRTC implementations.

mDNS is supposed to be innocuous:

It makes use of a top-level domain identify of its own (.local) that shouldn’t be used elsewhere anyway

mDNS is shipped over multicast, by itself dedicated IP and port, so it is limited to its personal closed world

If the mDNS identify (tsahi-laptop.local) is processed by a DNS server, it simply gained’t discover it and that would be the end of it

It doesn’t depart the world of the native community

It is shared in places where one needs to share DNS names

With WebRTC although, mDNS names are shared as an alternative of IP addresses. They usually are despatched over the public community, inside a protocol that expects to obtain only IP addresses and not DNS names.

The end result? Questions like this current one on discuss-webrtc:

Weird tackle format in c= line from browser

I am getting a suggestion SDP from browser with a connection line as such:

c=IN IP4 3db1cebd-e606-4dc1-b561-e0af5b4fd327.local

This is causing hassle in a webrtc server that we now have because the parser is dangerous (it is expecting a traditional ipv4 handle format)

[…]

This isn’t a singular prevalence. I’ve had a number of shoppers strategy me with comparable complaints.

What happens here, and in lots of other instances, is that the IP addresses that are expected to be in SDP messages are replaced with mDNS names – as an alternative of x.x.x.x:yyyy the servers obtain .local and the parsing of that info is completely totally different.

This applies to all kinds of media servers – the widespread SFU media server used for group video calls, gateways to different methods, PBX products, recording servers, and so forth.

A few of these have been up to date to help mDNS addresses inside ICE candidates already. Others in all probability haven’t, just like the current one above. But extra importantly, most of the deployments made that don’t want, want or care to upgrade their server software program so ceaselessly are now broken as properly, and ought to be upgraded.

Might Google have handled this higher?

Close-up Businessman Enjoying Checkers At Office Desk

In January, Google announced on discuss-webrtc this new experiment. More importantly, it said that:

No software code is affected by this function, so there are no actions for developers with regard to this experiment.

Inside every week, it acquired this in a reply:

Because it stands right now, most ICE libraries will fail to parse a session description with FQDN within the candidate handle and will fail to barter.

Extra importantly, present experiment does not work with something except Chrome on account of c= line population error. It will break on the essential session setup with Firefox. I might assume at the very least some testing ought to be attempted earlier than releasing one thing as “experiment” to the public. I understand the purpose of this experiment, but since it was launched without testing, all we acquired consequently are guaranteed failures each time it’s enabled.

The fascinating dialogue that ensued for some purpose targeted on how individuals interpret the varied DNS and ICE related standards and does libnice (an open supply implementation of ICE) breaks or doesn’t break because of mDNS.

Nevertheless it did not encompass the much greater situation – developers have been someway expected to write down their code in a means that gained’t break the introduction of mDNS in WebRTC – without even being conscious that this is going to happen sooner or later sooner or later.

Ignoring that reality, Google has been operating mDNS as an experiment for a couple of Chrome releases already. As an experiment, two issues have been decided:

It runs virtually “randomly” on Chrome browsers of users without any real control of the consumer or the service that that is occurring (not one thing automated and apparent at the very least)

It was added only when native IP addresses had to be shared and no permission for the digital camera or microphone have been requested for (obtain solely situations)

The larger situation here is that many view solely solutions of WebRTC are developed and deployed by individuals who aren’t “in the know” on the subject of WebRTC. They know the standard, they could know how you can implement with it, however most occasions, they don’t roam the discuss-webrtc mailing listing and their names and faces aren’t recognized inside the tight knit of the WebRTC group. They haven’t any voice in front of people who make such selections.

In that same thread dialogue, Google also shared the next assertion:

FWIW, we are additionally considering so as to add an choice to let consumer pressure this function on no matter getUserMedia permissions.

Thoughts you – that assertion was a one liner inside a forum discussion thread, from a person who didn’t determine in his message with a title or the fact that he speaks for Google and is a choice maker.

Which is the rationale I sat down to put in writing this article.

mDNS is GREAT. AWESOME. Actually. It is simple, elegant and will get the job carried out than another answer individuals would provide you with. However it’s a breaking change. And that may be a proven fact that seems to be lost to Google for some purpose.

By implementing mDNS addresses on all local IP addresses (which is a very good factor to do), Chrome will undoubtedly break lots of providers on the market. Most of them could be small, and not part of the small majority of the billion-minutes club.

Google must be much more clear and public about such a change. That is not at all a singular case.

Simply digging into what mDNS is, how it impacts WebRTC negotiation and what may break took me time. The preliminary messages about an mDNS experiment are simply not enough to get individuals to do anything about it. Google did a means better job with their rationalization concerning the migration from Plan B to Unified Plan as well as the following modifications in getStats().

My fundamental fear is that such a transparency doesn’t happen as a part of a deliberate rollout program. It is completed ad-hoc with every initiative finding its personal artistic answer to convey the modifications to the ecosystem.

This just isn’t enough.

WebRTC is large as we speak. Many businesses rely on it. It must be handled because the mission crucial system that developers who use it see in it.

It is time for Google to step up its recreation right here and put the mechanisms in place for that.

What do you have to do as a developer?

First? Go examine if mDNS breaks your app. You possibly can allow this performance on chrome://flags/#enable-webrtc-hide-local-ips-with-mdns

In the long term? My greatest suggestion can be to comply with messages coming out of Google in discuss-webrtc about their implementation of WebRTC. To actively read them. Read the replies and discussions that happen around them. To know what they imply. And to interact in that dialog as an alternative of silently studying the threads.

Check your purposes on the beta and Canary releases of Chrome. Gather WebRTC conduct related metrics out of your deployment to seek out sudden modifications there.

Aside from that? Nothing much you are able to do.

As for mDNS, it is a great improvement. I’ll be including a snippet rationalization about it to my WebRTC Tools course, one thing new that might be added subsequent month to the WebRTC Course. Stay tuned!

The post mDNS and .local ICE candidates are coming • BlogGeek.me appeared first on Tactics Socks.

0 notes

Text

mDNS and .local ICE candidates are coming • BlogGeek.me

09/07/2019

One other distuptive WebRTC experiment in Chrome to grow to be reality.

I’ve had shoppers approaching me prior to now month or two with questions about a brand new sort of tackle cropping up in as ICE candidates. Because it so happens, these new candidates have triggered some damaged experiences.

On this article, I’ll attempt to untangle how native ICE candidates work, what is mDNS, how it is utilized in WebRTC, why it breaks WebRTC and how this could have been dealt with better.

How native ICE candidates work in WebRTC?

Earlier than we go into mDNS, let’s start with understanding why we’re headed there with WebRTC.

When making an attempt to attach a session over WebRTC, there are 3 kinds of addresses that a WebRTC shopper tries to negotiate:

Local IP addresses

Public IP addresses, found by way of STUN servers

Public IP addresses, allocated on TURN servers

In the course of the ICE negotiation course of, your browser (or app) will contact its configured STUN and TURN server, asking them for addresses. It should additionally examine with the working system what local IP addresses it has in its disposal.

Why do we’d like an area IP handle?

If both machines that want to connect to one another using WebRTC sit inside the similar personal community, then there’s no need for the communication to go away the local community both.

Why do we’d like a public IP handle by way of STUN?

If the machines are on totally different networks, then by punching a hole by way of the NAT/firewall, we’d have the ability to use the public IP handle that will get allotted to our machine to communicate with the remote peer.

Why do we’d like a public IP handle on a TURN server?

If all else fails, then we have to relay our media via a “third party”. That third celebration is a TURN server.

Local IP addresses as a privateness danger

That a part of sharing local IP addresses? Can actually enhance things in getting calls related.

It’s also one thing that is extensively used and widespread in VoIP providers. The difference although is that VoIP providers that aren’t WebRTC and don’t run within the browsers are a bit more durable to hack or abuse. They have to be put in first.

WebRTC provides net builders “superpowers” in figuring out your local IP tackle. That scares privacy advocates who see this is as a breach of privacy and even gave it the identify “WebRTC Leak”.

A couple of things about that:

Any software operating on your gadget knows your IP handle and can report it again to someone

Only WebRTC (as far as I do know) provides the power to know your local IP addresses in the JavaScript code operating inside the browser (Flash had that additionally, but it is now quite lifeless)

Individuals using VPNs assume the VPNs takes care of that (browsers do supply mechanisms to remove native IP addresses), however they often fail to add WebRTC help properly

Native IP addresses can be used by JavaScript developers for issues like fingerprinting users or deciding if there’s a browser bot or a real human wanting at the page, although there are better ways of doing this stuff

There isn’t a safety danger right here. Simply privateness danger – leaking an area IP handle. How a lot danger does that entail? I don’t actually know

Is WebRTC being abused to reap local IP addresses?

Yes, we’ve recognized that drawback ever because the NY Occasions used a webrtc-based script to collect IP addresses back in 2015. “WebRTC IP leak” is one commonest search terms (search engine optimisation hacking at its greatest).

Fortunately for us, Google is amassing nameless utilization statistics from Chrome, making the knowledge out there by means of a public chromestatus metrics website. We will use that to see what proportion of the page masses WebRTC is used. The numbers are fairly… huge:

RTCPeerConnection calls on % of Chrome page masses (see here)

Presently, Eight% of web page masses create a RTCPeerConnection. 8%. That is quite a bit. We will see two giant will increase, one in early 2018 when 4% of pageloads used RTCPeerConnection and then another leap in November to 8%.

Now that simply means RTCPeerConnection is used. In an effort to collect local IPs the setLocalDescription name is required. There are statistics for this one as properly:

setLocalDescription calls on % of Chrome web page masses (see here)

The numbers here are significantly lower than for the constructor. This means a number of peer connections are constructed however not used. It’s considerably unclear why this happens. We will see a very massive improve in November 2018 to four%, at about the same time that PTC calls jumped to 7-Eight%. Whereas it is senseless, this is what we now have to work with.

Now, WebRTC could possibly be used legitimately to determine a peer-to-peer connection. For that we’d like both setLocalDescription and setRemoteDescription and we’ve statistics for the latter as properly:

setRemoteDescription calls on % of Chrome page masses (see right here)

Because the huge leap in late 2017 (which is explained by a unique method of gathering knowledge) the utilization of setRemoteDescription hovers between zero.03% and zero.04% of pageloads. That’s near 1% of the pages a peer connection is definitely created on.

We will get another concept about how in style WebRTC is from the getUserMedia statistics:

getUserMedia calls on % of Chrome web page masses (see here)

This is persistently round 0.05% of pageloads. A bit more than RTCPeerConnection getting used to truly open a session (that setRemoteDescription graph) however there are use-cases corresponding to taking a photo which do not require WebRTC.

Right here’s what we’ve arrived with, assuming the metrics collection of chromestats reflects real use conduct. We’ve 0.04% of pageloads compared to four%. Assuming the numbers and math is right, then a substantial proportion of the RTCCPeerConnections are probably used for a function aside from what WebRTC was designed for. That may be a drawback that must be solved.

* credit and because of Philipp Hancke for aiding in accumulating and analyzing the chromestats metrics

What’s mDNS?

Switching to a special matter earlier than we return to WebRTC leaks and native IP addresses.

mDNS stands for Multicast DNS. it is outlined in IETF RFC 6762.

mDNS is supposed to cope with having names for machines on native networks without having to register them on DNS servers. This is especially useful when there are no DNS servers you’ll be able to management – consider a home with a few units who have to interact regionally with out going to the web – Chromecast and network printers are some good examples. What we would like is something lightweight that requires no administration to make that magic work.

And how does it work precisely? Similarly to DNS itself, just with none international registration – no DNS server.

At its primary strategy, when a machine needs to know the IP tackle inside the native network of a tool with a given identify (let’s imagine tsahi-laptop), it’ll ship out an mDNS question on a recognized multicast IP handle (actual tackle and stuff might be discovered within the spec) with a request to seek out “tsahi-laptop.local”. There’s a separate registration mechanism whereby units can register their mDNS names on the native network by saying it inside the local network.

Because the request is shipped over a multicast tackle, all machines inside the native network receive it. The machine with that identify (in all probability my laptop, assuming it helps mDNS and is discoverable within the native network), will return back with its IP handle, doing that also over multicast.

That signifies that all machines in the native network heard the response and can now cache that reality – what’s the IP tackle on the local community for a machine referred to as tsahi-laptop.

How is mDNS utilized in WebRTC?

Again to that WebRTC leak and how mDNS may help us.

Why do we’d like native IP addresses? So that periods that have to happen in an area community don’t want to make use of public IP addresses. This makes routing lots easier and environment friendly in such instances.

But we additionally don’t need to share these local IP addresses with the Java Script software operating in the browser. That might be thought-about a breach of privacy.

Which is why mDNS was advised as an answer. There It is a new IETF draft often known as draft-ietf-rtcweb-mdns-ice-candidates-03. The authors behind it? Developers at each Apple and Google.

The rationale for it? Fixing the longstanding grievance about WebRTC leaking out IP addresses. From its summary:

WebRTC purposes gather ICE candidates as a part of the method of creating peer-to-peer connections. To maximise the chance of a direct peer-to-peer connection, shopper personal IP addresses are included on this candidate assortment. Nevertheless, disclosure of these addresses has privacy implications. This document describes a option to share native IP addresses with different shoppers whereas preserving shopper privateness. This is achieved by concealing IP addresses with dynamically generated Multicast DNS (mDNS) names.

How does this work?

Assuming WebRTC needs to share an area IP tackle which it deduces is personal, it’ll use an mDNS tackle for it as an alternative. If there isn’t a mDNS handle for it, it can generate and register a random one with the local community. That random mDNS identify will then be used as a alternative of the native IP handle in all SDP and ICE message negotiations.

The outcome?

The local IP handle isn’t exposed to the Java Script code of the appliance. The receiver of such an mDNS tackle can carry out a lookup on his native network and deduce the local IP tackle from there provided that the gadget is inside the similar local network

A constructive aspect effect is that now, the local IP handle isn’t uncovered to media, signaling and other servers both. Just the mDNS identify is understood to them. This reduces the level of belief wanted to attach two units by way of WebRTC even additional

Why this breaks WebRTC purposes?

Right here’s the rub though. mDNS breaks some WebRTC implementations.

mDNS is supposed to be innocuous:

It makes use of a top-level domain identify of its own (.local) that shouldn’t be used elsewhere anyway

mDNS is shipped over multicast, by itself dedicated IP and port, so it is limited to its personal closed world

If the mDNS identify (tsahi-laptop.local) is processed by a DNS server, it simply gained’t discover it and that would be the end of it

It doesn’t depart the world of the native community

It is shared in places where one needs to share DNS names

With WebRTC although, mDNS names are shared as an alternative of IP addresses. They usually are despatched over the public community, inside a protocol that expects to obtain only IP addresses and not DNS names.

The end result? Questions like this current one on discuss-webrtc:

Weird tackle format in c= line from browser

I am getting a suggestion SDP from browser with a connection line as such:

c=IN IP4 3db1cebd-e606-4dc1-b561-e0af5b4fd327.local

This is causing hassle in a webrtc server that we now have because the parser is dangerous (it is expecting a traditional ipv4 handle format)

[…]

This isn’t a singular prevalence. I’ve had a number of shoppers strategy me with comparable complaints.

What happens here, and in lots of other instances, is that the IP addresses that are expected to be in SDP messages are replaced with mDNS names – as an alternative of x.x.x.x:yyyy the servers obtain .local and the parsing of that info is completely totally different.

This applies to all kinds of media servers – the widespread SFU media server used for group video calls, gateways to different methods, PBX products, recording servers, and so forth.

A few of these have been up to date to help mDNS addresses inside ICE candidates already. Others in all probability haven’t, just like the current one above. But extra importantly, most of the deployments made that don’t want, want or care to upgrade their server software program so ceaselessly are now broken as properly, and ought to be upgraded.

Might Google have handled this higher?

Close-up Businessman Enjoying Checkers At Office Desk

In January, Google announced on discuss-webrtc this new experiment. More importantly, it said that:

No software code is affected by this function, so there are no actions for developers with regard to this experiment.

Inside every week, it acquired this in a reply:

Because it stands right now, most ICE libraries will fail to parse a session description with FQDN within the candidate handle and will fail to barter.

Extra importantly, present experiment does not work with something except Chrome on account of c= line population error. It will break on the essential session setup with Firefox. I might assume at the very least some testing ought to be attempted earlier than releasing one thing as “experiment” to the public. I understand the purpose of this experiment, but since it was launched without testing, all we acquired consequently are guaranteed failures each time it’s enabled.

The fascinating dialogue that ensued for some purpose targeted on how individuals interpret the varied DNS and ICE related standards and does libnice (an open supply implementation of ICE) breaks or doesn’t break because of mDNS.

Nevertheless it did not encompass the much greater situation – developers have been someway expected to write down their code in a means that gained’t break the introduction of mDNS in WebRTC – without even being conscious that this is going to happen sooner or later sooner or later.

Ignoring that reality, Google has been operating mDNS as an experiment for a couple of Chrome releases already. As an experiment, two issues have been decided:

It runs virtually “randomly” on Chrome browsers of users without any real control of the consumer or the service that that is occurring (not one thing automated and apparent at the very least)

It was added only when native IP addresses had to be shared and no permission for the digital camera or microphone have been requested for (obtain solely situations)

The larger situation here is that many view solely solutions of WebRTC are developed and deployed by individuals who aren’t “in the know” on the subject of WebRTC. They know the standard, they could know how you can implement with it, however most occasions, they don’t roam the discuss-webrtc mailing listing and their names and faces aren’t recognized inside the tight knit of the WebRTC group. They haven’t any voice in front of people who make such selections.

In that same thread dialogue, Google also shared the next assertion:

FWIW, we are additionally considering so as to add an choice to let consumer pressure this function on no matter getUserMedia permissions.

Thoughts you – that assertion was a one liner inside a forum discussion thread, from a person who didn’t determine in his message with a title or the fact that he speaks for Google and is a choice maker.

Which is the rationale I sat down to put in writing this article.

mDNS is GREAT. AWESOME. Actually. It is simple, elegant and will get the job carried out than another answer individuals would provide you with. However it’s a breaking change. And that may be a proven fact that seems to be lost to Google for some purpose.

By implementing mDNS addresses on all local IP addresses (which is a very good factor to do), Chrome will undoubtedly break lots of providers on the market. Most of them could be small, and not part of the small majority of the billion-minutes club.

Google must be much more clear and public about such a change. That is not at all a singular case.

Simply digging into what mDNS is, how it impacts WebRTC negotiation and what may break took me time. The preliminary messages about an mDNS experiment are simply not enough to get individuals to do anything about it. Google did a means better job with their rationalization concerning the migration from Plan B to Unified Plan as well as the following modifications in getStats().

My fundamental fear is that such a transparency doesn’t happen as a part of a deliberate rollout program. It is completed ad-hoc with every initiative finding its personal artistic answer to convey the modifications to the ecosystem.

This just isn’t enough.

WebRTC is large as we speak. Many businesses rely on it. It must be handled because the mission crucial system that developers who use it see in it.

It is time for Google to step up its recreation right here and put the mechanisms in place for that.

What do you have to do as a developer?

First? Go examine if mDNS breaks your app. You possibly can allow this performance on chrome://flags/#enable-webrtc-hide-local-ips-with-mdns

In the long term? My greatest suggestion can be to comply with messages coming out of Google in discuss-webrtc about their implementation of WebRTC. To actively read them. Read the replies and discussions that happen around them. To know what they imply. And to interact in that dialog as an alternative of silently studying the threads.

Check your purposes on the beta and Canary releases of Chrome. Gather WebRTC conduct related metrics out of your deployment to seek out sudden modifications there.

Aside from that? Nothing much you are able to do.