#Third World Approaches to International Law

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What are the features, knowledges, values, representations, practices, infrastructures, institutions, and governance modes of a just world that fits within planetary boundaries? How can we imagine them in a way that acknowledges the deep entanglements between human and non-human worlds while addressing the ubiquity of entrenched asymmetrical power relations that structure global societies?

— Ivana Isailovic, "Introduction" in "Radical Imagining of ‘Just & Green’ Futures."

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Ivana Isailovic#radical imagining of just green-futures#TWAIL#Third World Approaches to International Law#International Law#climate change#climate justice#global warming#climate crisis#climate emergency#climate#sustainability#climate solutions#climate action#environment#gradblr#studyblr#quotes#quote#academia#Law#Solarpunk#greenpunk#environmental justice#activist#activism#extinction rebellion

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It is not a coincidence that the legacy of five hundred years of settler colonialism, genocide, slavery, apartheid, and systemic racial discrimination is climate change, mass extinction, desertification, deforestation, and the increasing toxicity of the air, water, and land." ~Usha Natarajan

#Third World Approaches to International Rights#TWAIL#Climate change#climate justice#global warming#climate crisis#international law#united nations#human rights#solarpunk#environmental issues#environmentalism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Matching Misfortunes: Edmund Pevensie

He's arguably my favourite character right alongside Caspian the Tenth. Let's hope I did his character justice. The other parts for the pevensies are up on my blog.

.

Edmund stalks into the debate hall with his notes in his hands, and the room falls into a hush.

The students cease their muttering, their eyes tracking the lanky, too-thin boy as he walks with far too much grace for someone who is fifteen-almost-sixteen years old and has yet to get his final growth spurt.

His limbs are too long for his blazer-adorned torso and he is not yet old enough to put on muscle, and still he moves with thrice as much control and precision as the royalty of the country.

Edmund remembers the months After.

He remembers stumbling and falling and breaking bone because he was a twenty-nine year old man in the body of a ten year old child, falling till he got sick of it and asked Susan to help him learn how to walk again, remembers tear-soaked cheeks and trembling callous-less hands and bitten-off screams after being woken up by a nightmare in the middle of the night, feeling too thin, too short, too young, too weak, too cold Peter, please, it’s too cold, help me—

Never again, he had told himself.

He feels their stares settle over his strange unscarred skin like a layer of cold gel, and he ignores them in favour of holding his head high and walking towards the desk with his name tag on it. He relaxes into the seat as much as he can, back straight and shoulders pulled back and breathing even, and then moves his gaze to meet the eyes of everyone that is looking at him.

Most students hurriedly look away, flushes staining their cheeks bright red out of the embarrassment of getting caught staring so blatantly. A select few stare back, holding his gaze for a couple of seconds before they, too, lower their eyes and turn back to their conversation.

It both does and does not feel like the Royal Court that he once presided over.

There too, conversations used to stop when he entered the Throne Room. There, too, people used to follow him with their eyes as he moved towards his throne beside Peter’s. There, too, he used to keep his back straight and roll his shoulders back and breathe evenly to prepare himself for the approaching war of words that he was certain he would win.

He lounges in his seat like he’s lounging in his throne, and watches the faculty walk into the room and take their seats. He does not bother to stand up like the rest of the students do, and ignores the disapproving looks Professor Jasmine throws at him for his supposed insolence.

What do they know of debates, he thinks with a hidden sneer.

He was the one that sat with bloodthirsty Kings and Warlords, manipulative Queens and Bandit Chiefs, and aided his older sister in hammering out treaties and ceasefires and surrenders from their enemies’ lips without having to lift a sword. He wrote the laws for his world and presided over the Supreme Court of Justice of his kingdom, solved internal disputes and planned war strategies and invented new tactics for external conflicts. He was renowned for his excellence with double swords and double-edged words alike, in Narnia.

In Narnia, he was King Edmund the Just, the Serpent Tongued Diplomat King, Third of the Beloved Four, Representative of the People.

Here in post War England, he is just Edmund Pevensie, with sharp glares and sharper words, as dangerous with his tongue as his older brother was with his fists and his older sister with her smiles.

Unlike Peter who swings between two worlds without control over his thoughts and memories, and Susan who tries (and fails miserably) to not think about their world at all, it is comparatively easy for Edmund to maintain the two different worlds as different experiences. For him, Narnia exists in one part of his mind and England in the other— separated from each other by a solid stone wall that Edmund has built up and strengthened over the five and a half years that have passed since he and the others fell out of that thrice-damned wardrobe, in bodies that were no longer theirs.

And yet, his nail beds itch.

He remembers the feel of digging his nails into flesh, remembers the feel of blood welling up under his fingers as he dug deeper, remembers the feel of being older, taller, stronger, wiser. He remembers being powerful.

Around him, the debate competition begins. He dimly registers the names of the students from the seventeen participating schools as they are introduced, and recognises more than half of them.

He treats debate competitions in schools just as he did political meets back when he used to be King. There are always three things one must know— the topic that you are to speak on, the questions that you may be asked, and the people who will be attending. About the people, you must know their agendas, their strengths and their weaknesses, and how to use that to gain what you desire. As simple, and as difficult, as that.

Here, he recognises twelve out of the seventeen opponents, and feels his lips curve into a small smirk. The participants seated on either side of him lean away from him, and it only makes his smirk grow wider with vindication.

He misses attending and holding Court. He misses the gratification in verbally ripping apart nobles and bloodthirsty warlords alike, he misses the satisfaction he felt while sinking his two swords into flesh on the battlefield in case the peace talks went wrong.

He misses being covered in blood after a victory, misses the annual Royal debate competitions, the mock arguments he had with Susan and the members of the Royal Court of Narnia, the vindictive smugness he felt when he put the fear of the Narnian Royalty in the hearts of warlords seeking to destroy his kingdom with nothing but his words and occasionally his swords.

Here, Edmund has to remind himself that he is arguing with children.

He has to remind himself that the people he is debating with are not warlords and power-hungry rulers out to conquer his kingdom.

He has to remind himself to not turn into the Serpent Tongued Diplomat King, to keep that vicious and twisted part of him safely locked up in the Narnian part of his memories. He has to keep the whole of his true self at bay, because he knows that they will not understand his metaphorical bloodlust when it comes to the art of wordplay.

He knows that they will not understand what it is like, to be an adult in a child’s body forced to play pretend politics where he has no real influence on the country’s government.

However, he thinks as the debate competition commences and a girl in a smart navy blue suit walks onto stage and starts giving her speech, he can allow certain attributes from his Kingly self through into his teenage self. In controlled amounts, he can allow himself a little ruthlessness, a little edge to his words, a little confidence, a little dignity and grace.

He can allow himself to indulge a little, to employ a few of his Kingly attributes into his teenage identity so he can get through secondary school without being given as hard a time as normal teenagers are.

That is one benefit of having been King— he might not have grown up in this world, but he had grown up before. As uncomfortable it was to grow up again, he knows what to expect this time.

He is better prepared than he was last time.

He leans forward and notes down a question for a statement the girl makes, and he feels the stares of the students on his back again. The vindication rises in his body; he is a force to be reckoned with and his opponents know it, and Edmund revels in the effect he has on them, revels in the way they cannot meet his eyes properly without having to look down. It almost feels like he is King again and they are his enemies— forced to bow to him after being defeated time and again, forced to grudgingly admit that he is superior to them.

The debate progresses, he gives his speech, gets asked questions and answers them as best as he can. He scratches his itching nails over his palms as he listens to the rest of their speeches and asks them questions, and sits back with his dissatisfaction very visible on his face when he does not receive the answers he was hoping for.

In the end, he lifts the trophy up with fingers that despair for the feel of his swords gripped in them, a satisfied gleam in his piercing blue eyes and a badge that proclaims him as the first ranker pinned to the front of his school blazer.

Dozens of eyes follow him as he steps off the stage and strides out of the room, and he lets them settle on his proud shoulders. Lets them turn into the weight he once carried in the form of a silver crown.

Let them see, he thinks viciously. His nails itch, and he wishes to sink them into flesh and rip it apart. He wishes to drench himself in the blood of his enemies.

Let them be witness to merely a fraction of the power I used to possess. Let them understand that I am dangerous, and not to be underestimated. Let them see that I am not a mere child.

He is a boy, arguing politics, modern and ancient war tactics and ethics with professors in his free time, having rumours of being a genius follow him around like obedient dogs at their master’s heels.

He is a King, shackled and hidden in the corner of a mind that belongs to a too-lanky teenage boy halfway through puberty.

He refuses to reach too deep into the memories. He refuses to forget the memories. He refuses to let himself sink into his own mind. He refuses to forget himself, and he refuses to be his entire self.

He cannot. He will not.

#edmund pevensie#the pevensies#pevensie siblings#narnia meta#the chronicles of narnia#narnia#lww#the lion the witch and the wardrobe#matching misfortunes#edmund is a darling and i will bathe in the blood of anyone who says otherwise#lucy pevensie#susan pevensie#peter pevensie

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earlier this year, U.S. President Donald Trump signed a slew of executive actions that could set the country back decades on ocean protection—reopening the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument to commercial fishing and undoing all the progress that has been made to end overfishing and rebuild fish stocks and the United States’ fisheries. Going further than any previous administration, he also issued an executive order in April that seeks to fast-track the launch of deep-sea mining in domestic and international waters.

Yet Trump’s retreat from international forums and multilateral institutions has created a vacuum that other countries have been quick to fill. For instance, the third United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC) last month delivered real progress and momentum on several critical issues at a pivotal time.

It’s tempting to be cynical about the impact of slow-moving U.N. bodies, and UNOC was by no means perfect. But its celebration of multilateralism offered a clear-headed rebuke to the approach being taken by the Trump administration, which didn’t bother to show up at all—at least, not officially. And as the world prepares for the final round of negotiations for the Global Plastics Treaty in August in Geneva, there’s another opportunity for countries to push forward with or without the cooperation of the United States.

Let’s be clear: Trump’s executive orders on the environment pose a real problem—and not just for those who care about protecting the ocean, one of our planet’s last remaining global commons.

Prioritizing corporate profit over the long-term health of this vital resource may appease shortsighted lobbyists, but deregulation will ultimately destroy the ocean that we all depend on for a livable planet. That’s also, incidentally, bad for business. Trump’s attempt to circumvent international law may not be shocking from someone who pulled the United States out of the 2015 Paris Agreement on his first day back in office, but it is yet another attempt to pander to his base that will ultimately undermine U.S. interests and standing.

At the top of the agenda at UNOC was the issue of deep-sea mining. While the United States’ absence was certainly noted, it was Trump’s April executive order on deep-sea mining that appalled nearly everyone present. The meeting proved to be a big moment for efforts to counteract this action, with Slovenia, the Marshall Islands, Cyprus, and Latvia joining a growing list of countries publicly calling for a moratorium or precautionary pause on such mining.

As attention shifts to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) meeting now underway in Jamaica, states will consider adopting a moratorium or some sort of precautionary pause on deep-sea mining in the high seas. The approach recently announced by Trump will definitely be a part of the conversations—but the fact that there are now 37 states on record opposed to rushing ahead with a new code that would permit such mining makes it very unlikely that it will be allowed in international waters any time soon. In a world that is reeling from the combined impacts of climate change, plastic pollution, industrial fisheries, deforestation, and war, this is not the time to optionally launch a new destructive and unnecessary industry.

It’s also not clear how feasible Trump’s deep-sea mining executive order even is in practice. On April 24, the president had ordered the secretary of commerce to “expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits in areas beyond national jurisdiction under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act.” Using this act—a 1980 law intended to be a stopgap measure until the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea entered into force—as a vehicle to bypass international law is likely to prompt multiple lawsuits if any mining is actually permitted or ever takes place.

In the absence of an ISA framework, any minerals obtained from areas beyond national jurisdiction under Trump’s executive order would likely be illegal to export for sale or processing. This would significantly limit their potential value, adding even greater challenges for a venture that already appears likely to be too expensive to be commercially viable without major public subsidies.

Bypassing the ISA, which was established by the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), could have far-reaching consequences for the United States. Despite failing to ratify UNCLOS, the United States benefits from the treaty in many ways. From shipping and commerce to science and military uses, UNCLOS provides a global framework for how states operate on 71 percent of the earth’s surface.

UNCLOS has territorial implications as well, both designating areas up to 200 nautical miles from land as states’ exclusive economic zones and providing a means to expand these areas through extended continental shelf claims. Trump’s deep-sea mining executive order has already drawn strong criticism from several states, and it may well lead to more significant problems for U.S. interests on the high seas.

Beyond the ISA, the international community is looking to negotiations on the Global Plastics Treaty. A lot is at stake, as plastics are now understood not just to be a serious threat to marine life but also to biodiversity, human health, and environmental justice. While it is not clear if and how the United States will participate in these negotiations, all signs point to Washington retreating from global leadership in these spaces as well.

Even so, with 19 new countries ratifying the Global Ocean Treaty at UNOC, it is likely that we will reach the necessary 60 in time for the U.N. General Assembly in September.

Ultimately, Trump’s brand of isolationism and exceptionalism will be outlasted by the multilateral agreements made in the coming months—which will present new opportunities for leadership from China, India, and Brazil, as well as regional blocs such as the European Union, Pacific Small Island Developing States, and the African Group.

It is important for the international community to make decisions that are in line with what the best available science tells us is necessary—and in line with what justice demands. This is no time to allow outliers to drive unacceptable compromises or unending delays that prevent the majority of governments from doing the urgent work of protecting people and our planet. The United States and other holdouts will catch up eventually.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indigenous Intercultural Health in Chile

Since the return to democracy in Chile in 1990 CE, the new governments have dealt with one of the great historical debts of the Chilean state, its relationship with the indigenous peoples. These peoples have been historically marginalized and made invisible in all spheres. However, with the revaluation of their cultural heritage, indigenous medicine and the use of elements of nature and medicinal herbs - wisdom accumulated for centuries - re-emerges. Through the Special Program of Health and Indigenous Peoples (PESPI by its Spanish acronym, Programa Especial de Salud y Pueblos Indígenas), present in almost all health services in Chile, indigenous medicine has become available for the whole population as a valued alternative within the official medical system. This programme promotes complementarity between the conventional and indigenous medical systems, incorporating intercultural medical assistance in hospital and primary care facilities.

Traditional Mapuche Health

The PESPI programme promotes the indigenous health of each of the peoples recognized by the Chilean State (Chile recognizes 9 indigenous peoples) and the complementarity with the official medical system. The public health strategy is to establish a link between the hegemonic medical system and the alternative one, reinforced and supported by the recommendations of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO):

This perspective assumes, therefore, that medical systems alone are not sufficient to meet the health demands of an indigenous population, both in their conceptions of health and disease and in the way they carry out healing. (Manriquez-Hizaut et al., 760)

The Mapuche people are the most numerous and have the greatest presence in the urban context, particularly in Santiago where nearly a third of Chile's indigenous population lives. Their conception of illness and health is quite different from the one we know today, and this diverse view has generated interest not only among the Chilean indigenous population who value this ancestral wisdom but also among the non-indigenous population and the health teams in care facilities.

Mapuche medicine understands health as a balance basically in two areas. Firstly, the person is conceived as an "open body", as opposed to the modern view of a closed and divided body (inaugurated with Descartes): "The integrative conception of the body or "open body" leads its people to live illness and health as states of the body in relation to its social environment: "wezafelen" or being bad and "kumel kalen" or being good" (Solar, 2005, 2).

The idea of kumel kalen or küme mongen (to be well, to live well) is also present in other Latin American cultures under the concepts of Sumak Kawsay in Quechua or Suma Qamaña in Aymara for example. The illness is then understood as a lack of respect or imbalance of the individual with its environment. This can happen through the transgression of laws, rites, or the forbidden. In this way, "the evil is not the disease, but the cause that produced it and thus considers the disease not as an evil, but as a reaction to the evil" (Solar, 4).

Secondly, the Mapuche worldview sees the universe or the whole as a unit made up of opposite and complementary poles. Likewise, health (Konalen) and illness (Kutran) are in constant tension, making it impossible to see the body as an isolated unit, but rather as an open entity that reflects the tensions and balance of the world. Thus, in order to incorporate the indigenous approach to the traditional health system, the only way is to talk about complementarity, that is, a relationship that allows health teams to get closer to indigenous medicine specialists (machi or lawentuchefe), that allows for the derivation and exchange of knowledge when necessary.

Continue reading...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to an international lawyers conference and I met so many ppl whose work I’ve cited and a GIANT in the third world approaches to international law field told me my research was important 😭😭😭

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top PEO Service Providers in India: Why Brookspayroll Leads the Way

As businesses around the world expand into India, the demand for Professional Employer Organization (PEO) services is at an all-time high. PEOs simplify workforce management by handling payroll, HR, benefits, and compliance — all under one roof. For global companies and startups alike, choosing the right PEO service provider in India can be the key to smooth expansion and long-term success.

Among the many PEO service providers in India, Brookspayroll stands out as a trusted partner that delivers efficiency, compliance, and cost-effective HR solutions.

What is a PEO and Why Do Businesses Need One?

A Professional Employer Organization (PEO) is a third-party service that manages critical HR functions, allowing companies to focus on their core business operations. PEOs provide:

Employee onboarding and offboarding

Payroll processing and tax filing

Statutory compliance with Indian labor laws

Employee benefits administration

Risk management and HR consulting

For international businesses entering the Indian market, working with a reliable PEO provider in India like Brookspayroll ensures that you stay compliant and competitive — without the hassle of setting up a local entity.

Brookspayroll: Leading PEO Service Provider in India

Brookspayroll has earned a solid reputation as one of the best PEO service providers in India, offering tailored solutions for companies of all sizes. Here's why businesses choose Brookspayroll:

1. End-to-End HR Management

From recruitment and onboarding to payroll and benefits, Brookspayroll handles it all. Their services are designed to support your workforce seamlessly and efficiently.

2. Local Compliance Expertise

India’s labor and tax laws can be complex and ever-changing. Brookspayroll ensures your business complies with all statutory regulations, including PF, ESI, gratuity, and labor laws.

3. Fast Market Entry

No need to establish a legal entity in India. With Brookspayroll's PEO services, businesses can hire employees quickly and legally — accelerating market entry.

4. Scalable Solutions

Whether you're hiring one employee or hundreds, Brookspayroll scales its services based on your business needs. Ideal for startups, SMEs, and global enterprises alike.

5. Technology-Driven Services

With intuitive dashboards, automated payroll systems, and employee self-service portals, Brookspayroll combines human expertise with cutting-edge technology.

Benefits of Partnering with a PEO Service Provider in India

Choosing a reliable PEO partner in India offers numerous advantages:

Reduced operational costs

Minimized legal and HR risks

Quick workforce deployment

Local market insights

Enhanced employee experience

Brookspayroll not only provides all of these benefits but also goes a step further with personalized support and proactive HR advisory services.

Industries Served by Brookspayroll

Brookspayroll caters to a wide range of industries including:

Information Technology (IT)

E-commerce and Retail

Healthcare

Manufacturing

Consulting and Professional Services

Startups and Global Enterprises

No matter the sector, Brookspayroll’s PEO solutions are customized to suit the unique needs of your workforce and business model.

Ready to Expand in India? Partner with Brookspayroll Today

When it comes to PEO service providers in India, Brookspayroll is your trusted partner for hassle-free business expansion. With a proven track record, industry-leading expertise, and customer-centric approach, Brookspayroll helps businesses grow confidently in the Indian market.

Contact Brookspayroll today to learn how our PEO solutions can simplify your HR operations and support your global expansion goals.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

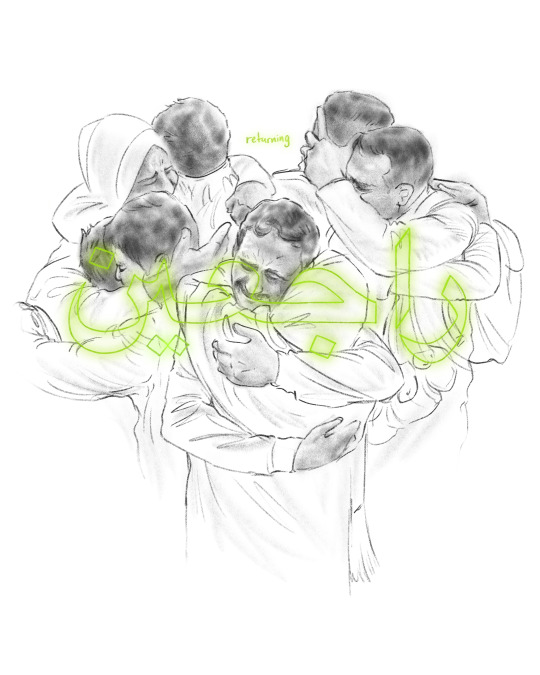

Rajieen, Returning

I've decided to try posting my Imago Palestina project here on Tumblr! I enjoy reading longer stuff here, so I figured others might too. If people like it, I'll keep it up! This post is a few weeks old (Feb 2, 2025) but it feels like a good starting place. If you want to see the newest stuff right now, or get it in your inbox when I post, go to ImagoPalestina.Substack.com!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Lift up your eyes and look around: They all gather and come to you; your sons will come from afar, and your daughters will be carried on the arm.

They will rebuild the ancient ruins and restore the places long devastated; they will renew the ruined cities that have been devastated for generations.” (Isaiah 60:4 & 61:4)

I hope you’ve seen some of the videos coming out of Gaza this last week. Images of corridors of people, not pushed from behind by tanks but marching confidently back along the sea to their homes. Tears shed not in mourning but in pure, unbridlable joy, as family, friends, and neighbours who haven’t seen each other in up to fifteen months—many who thought they may never see each other again—cling to each other like a prayer to never be separated. The captives finally set free of their chains, met with shouts of joy by the communities and loved ones that had so long felt their absence.

Even in cases like that last one, where the Israeli government specifically refused to allow freed Palestinian captives any “public displays of joy,” there’s only so much you can do to stop a wave of joy this powerful, this genuine, and this widely spread through empathetic neighbours throughout the world.

Palestinian joy is a beautiful thing.

In the past week, with the first phase of this very fragile ceasefire already approaching one third completion, our neighbours who had been displaced to the south of Gaza have finally begun the journeys back to their homes—and to whatever they may find there. This hasn’t been easy, quick, or safe. Travel is hard enough already for everyone, as vehicles beyond animal-drawn wagons are virtually nonexistent, but for the hundreds of thousands of injured, disabled, and elderly Gazans, the trek is especially an ordeal. Israel still maintains a military presence on the Netzarim corridor separating Gaza’s north and south, meaning that the thousands of people returning to the north have to wait to pass through what is now the biggest checkpoint in occupied Palestine. While the five hundred thousand strong crowd of displaced Gazans is now finally moving through this checkpoint, the week began with Israeli soldiers opening fire multiple on returning Palestinians, killing two and wounding nine others.

And still, for many, this return serves as only a foretaste of the feast yet to come.

I began this project by sharing the story of Isam Hamad, a Palestinian organizer who helped start the Great March of Return in 2018. For those of you who haven’t heard Isam’s story (I’d urge you to check it out), this peaceful protest was, for Isam, a manifestation of one of the Palestinian people’s core demands: let us go home. It’s a demand that is enshrined in international law—UN resolution 194 states that “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practical date”—but, to me, it’s also just something that is fundamentally understandable, isn’t it?

For us Christians, ‘return’ is something that is inseparably woven through so much of our theology, our upbringing, and the stories we tell to each other and about each other. Some would argue that the central pillar of the Christian faith is of returning to a right relationship with God, and of realizing that it’s never too late to return. But beyond that, in more tangible ways, our scriptures are full of real hopes, doubts, fears, and promises about returning. This we share with our Jewish siblings, as so much of the Jewish writing that became our Old Testament and influenced our founding apostles (and Christ himself) was written in and about the process of returning from exile. We probably wouldn’t have the Bible at all if faithful Jews exiled to Babylon didn’t dream of returning home and want to make those dreams tangible.

I quoted one of these tangible dreams at the outset of this message because I think it’s an irresistible image of hope for this moment, and because it so beautifully lays plain the connections between us and our neighbours today and our ancestors two and half thousand years ago. My critics will say that I’m taking those verses out of context, that these promises were for the restoration of Israel, and perhaps even argue that this 76 year colonial project is the realization of this return. But I’d challenge them to reconsider what context really means.

When the prophet, in the voice of God, addresses Israel, he’s not talking to a modern nation state—known in Hebrew as Medinat Israel—but rather, the members of his community whose faith and identity was being forged and reforged in the crucible of exile—Am Yisrael. To me, the context that’s most relevant is these experiences, shared across centuries, and the way we believe God shows up for those pushed to the margins. As a Christian, I am not ashamed of believing that God’s people includes all people, and that God’s redemptive power is most often shown in the poor, the chained, and the oppressed—just as Christ himself did when he read from this same text to his own community.

In response to Zionist narratives, built on interpretations of these same Biblical prophesies, of a return which demands exclusivity and ethnic cleansing, we need to insist wholeheartedly on God’s promises of compassion, not conquest, new life, not suffocation—and that these promises are for all his people. The book of Isaiah is a call to remember the responsibility of living in community together, the consequences for choosing power, wealth, and self-interest over the love of neighbour and care for the oppressed, and the need for justice to return just as the prophet envisions people returning to their lands. Some 2500 years removed, God still walks with those who wander in exile, who long for restoration, and who nonetheless prepare to return to ruined cities.

It’s for this reason that I, once again, hope you’ve seen some of the videos coming out of Gaza this week. Images of land as far as the eye can see—basically all of Rafah, once Biden’s “red line”—reduced to rubble. Tears of disappointment and disorientation as our neighbours return to find a heap of garbage where their beloved home once stood, or the graveyard where they buried their mother and grandmother completely bulldozed. The wailing and lament for 15-year old Zakaria Humaid Yahya Barbakh who was shot multiple times by an Israeli sniper (who also fired on the man who dove in to rescue Zakaria) on the second day of the ceasefire.

We need to celebrate the joy of return, but we shouldn’t sugar-coat it. This is not the return that Isam marched for or our Palestinian neighbours in the diaspora pray for. This is a return, back into the wreckage of genocide, under the thumb of occupation, within a fragile truce which may still not last more than a few more weeks. I wonder if our neighbours embracing each other at the central checkpoint held so tight because they don’t know how long they’ll be able to hold on this time.

And yet, with our ancestors returning from exile in Babylon, and our church mothers and fathers who laboured to build a kingdom community worthy of Christ’s return, I have faith in what this foretaste promises. Taste and see with all of your senses, but don’t be satisfied yet. It’s our job to march confidently along the sea together, sure of our destination, and working to sew seeds of liberation every step of the way.

“He asked me, “Son of man, can these bones live?” I said, “Sovereign LORD, you alone know.” (Ezekiel 37:3)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Prayer Requests

With your heart: Pray for our neighbours as they return to their homes. Pray that they would find safety along the route, and that the weight of their journey would be eased. Pray that they find comfort waiting for them. Pray that if they don’t, they would rebuild their ruined cities and live in them, that they would grow new vineyards and taste the fruit of new gardens. Pray that this foretaste would restore their strength and that the feast would be right around the corner.

With your voice: Use CJPME’s email tool to tell the Ontario Government to dismantle the shadowy and deceptively-named “Hate Crimes Working Group,” which works to silence voices against Israeli genocide. Find more info here

With your hands: Make a donation to The Sameer Project to support our neighbours as they return to uncertain circumstances

More Information

Watch the compilation of videos of our neighbours’ tearful reunions that I referenced to draw today’s illustration

Rajieen, which means “returning,” has long been a rallying cry for Palestinians. Here are a couple resources I wasn’t able to reference in the post:

““We Are Returning”: An Anthem for Palestinian Liberation” by Maha Nassar at the Critical Inquiry Blog

Palestinian activists from Maryland perform the Chant of Return

Some messages from our neighbours about this return:

Bisan finally returns to her house

Gaza Soup Kitchen brings chef Mahmoud’s remains to his family cemetery, only to destroyed

The Sameer Project reports on the new situation in North Gaza and Gaza City

Rabie documents the journey back home

Ahmed the Little Farmer documents the journey back home

“Israel wants no celebrations when Palestinian prisoners freed in Gaza deal” at The New Arab

Video from Bisan Owda as she approaches the Netzarim checkpoint

Video from UN OCHA showing the crowd of Gazans waiting at the Netzarim checkpoint

“‘I’d crawl if I have to’: Palestinians eager to return to northern Gaza” at Al Jazeera

"Isam Hamad” at Imago Palestina

“The 3 Israels” at Jewitches

“Resolution 194” at UNRWA.org

“All That Remains” infographic at Humaniti Project

“Drone footage shows the scale of destruction in Gaza's Rafah – video” at the Guardian

“‘My neighborhood was one of the most beautiful in Gaza. All that’s left is rubble’” at +972 Magazine

“Israeli sniper kills Palestinian boy in Gaza on second day of ceasefire” at Middle East Monitor

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the point of making Ozzie a demon if he's not going to be evil, dangerous and deadly like demons are supposed to be? Vivziepop sucks at making demon characters.not only do her characters look nothing like demons and now they don't act like ones??? Hazbin Hotel is doomed,might as well make Hazbin a preschool show at this point.its also embarrassing that the king of hell (Lucifer) is just Stolas 2.0 from reading the leaked scripts.Id like to add more but im far too tired because this is getting absurdly painful.

I think there is valid criticism in this critique, but I also feel that, in a way, it is rather exaggerated outrage.

When it comes to demons behaving any specific way, that mainly comes down to poor world building. Spindlehorse has done very little to actually dictate how this world of hers works, and many times, it appears she actively contradicts values previously assumed.

Are there vastly different laws and social expectations between rings?

Loo Loo Land, and once again in Oops, Greed is shown to have an extremely lax approach to crimes of violence.

However, in Harvest Moon, having previously killed people results in Millie being banned from participating in the episode.

Stolas being in public with Blitz gets no notice or response of attention in Harvest Moon and again later in Ozzie's. But then the internal logic contradicts that same episode with Walley acting like it is actually a huge deal. And then for a third time the series presents an about face with Beelzebub dating Tex as if there is nothing special going on there.

Stolas cheats, but he is not wrong for that, which makes it not a flaw.

Then, the world building tries to reinforce the idea that this relationship would be a problem by trying to highlight a demon racial and status divide in Western Energy. Only for Queen Bee and Oops to backtrack again and make it extremely normalized with Beelzebub dating a common Hell Hound and Asmodeus' conflict not being about who he is dating, but the act of dating in the first place.

Going into the idea of "good" and "evil," I don't really think that is a good argument to make. There has to be some sense of conflict for a story to maintain interest, and if the idea of "evil" is the norm was played to a logical conclusion, it would feel more like a joke than anything else. Like in Good Omens, where Hell is dictated by doing the worst thing possible and anything that produces a moral positive is bad. It would completely isolate the audience from the values of the cast, which is why Crowley is depicted as having a personality and values more aligned to humans. As such, it doesn't feel like a good faith platform to stand on when criticizing the show.

What I will say is fair, however, is that Medrano has achieved an Olympic medal in trying to make her characters entirely flawless. There is no consistent character flaw that any of her cast maintains out of what is deemed necessary by the plot or depicted as not a flaw by context.

Asmodeus is quite literally perfect for Vivienne's standards. His whole life revolves around his partner, and he is willing to do whatever it takes for that partner, including murder. But that is good, actually.

Blitz is inconsistently too insecure in his relationships. He's insecure when it comes to FizzaRolli and Stolas, resulting in him burning down his own family home and violently rejecting Stolas after the night at Ozzie's. But he's so secure in other relationships that: (1) despite knowing Barbie doesn't want to see him, he tracks her down, (2) he is overbearing of Loona despite feeling like she hates him, (3) abuses Moxxie, despite having issues with losing people.

And I think that's what this criticism is actually addressing. A lack of understanding the stakes and values the world plays on while simultaneously being handed characters who are so volatile in their own values every time we see them that it is pretty much impossible to defer those values passively.

#helluva boss critical#helluva boss criticism#helluva boss critique#vivienne medrano#vivziepop#helluva boss#vivziepop critical#spindlehorse critical#spindlehorse criticism#world building#inconsistency#bad writing

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Yale University Law School associate research scholar was terminated after failing to disclose information about her alleged ties to Samidoun Network, a Canada-based group designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department.

Iranian-born Helyeh Doutaghi was fired Friday, three weeks after being put on administrative leave after allegations were made that she was part of the Samidoun Network, classified as "a sham charity" by the federal government for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a U.S-designated terrorist organization.

"Over the last three weeks, Yale has repeatedly requested to meet with Ms. Doutaghi and her attorney to obtain clarifying information and resolve this matter," Yale spokesperson Alden Ferro said in a statement provided to Fox News Digital. "Unfortunately, she has refused to meet to provide any responses to critical questions, including whether she has ever engaged in prohibited activity with organizations or individuals that were placed on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list ('SDN List')."

As such, the university terminated Doutaghi, effective immediately, over her "refusal to cooperate" with their investigation. The university, which saw its fair share of anti-Israel protests last year and a large-scale graduation walkout, noted her short-term employment was already set to expire in April.

Doutaghi was appointed deputy director of the Law and Political Economy (LPE) Project at the unversity in October 2023. According to her bio on the Palestine Center for Public Policy website, her "research explores the intersections of the Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), encompassing Marxian and postcolonial critiques of law, sanctions, and international political economy."

She is also an incoming post-doctoral fellow at the University of Tehran, according to the website, where her focus will be "completing her manuscript on Iranian sanctions regime and neoliberalism."

The allegations about Doutaghi were first made by Jewish Onliner, a Substack "Empowered by A.I. capabilities," according to its X account.

"Rather than defend me, the Yale Law School moved within less than 24 hours of learning about the report to place me on leave," Doutaghi wrote in a statement on X earlier this month. "I was given only a few hours’ notice by the administration to attend an interrogation based on far-right AI-generated allegations against me, while enduring a flood of online harassment, death threats, and abuse by Zionist trolls, exacerbating ongoing unprecedented distress and complications both at work and at home."

Doutaghi said she was "afforded no due process and no reasonable time to consult" with her attorney.

The termination of Doutaghi comes as the Trump administration has been clamping down on allegations of antisemitism across Ivy League schools.

Several students holding visas or green cards have since filed lawsuits against the Trump administration, alleging First Amendment violations.

"Immediate action will be taken by the Department of Justice to protect law and order, quell pro-Hamas vandalism and intimidation, and investigate and punish anti-Jewish racism in leftist, anti-American colleges and universities," a White House fact sheet on the executive order said.

Trump also vowed to deport Hamas sympathizers and revoke student visas.

Columbia University student and anti-Israel activist Mahmoud Khalil was among the first students to face allegations from the Trump administration over his green card application, in which he was accused of omitting details about his employment history.

The administration subsequently pulled $400 million in federal funding from Columbia University, citing its handling of anti-Israel protests on campus last year. The Ivy League school announced on Friday it would implement significant policy changes to comply with the administration's demands.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

*ISRAEL REALTIME* - "Connecting the World to Israel in Realtime"

HAPPY CHANUKAH !!! Chanukah night 7 TONIGHT 🕎🕎🕎🕎🕎🕎🕎

◾️MORE SHIP ATTACKS BY THE HOUTHIS… a Marshall islands-flagged chemical tanker reported an "exchange of fire" with a speedboat 55 nautical miles (around 102 kilometres) off Yemen. A speedboat with armed men aboard approached two vessels transiting off the coast of Yemen's Red Sea port of Hodeidah. (AP) the Houthis launched two missiles at a commercial ship in the Bab al-Mandab Strait but missed, according to US officials. An American vessel intercepted another drone launched by the Houthis. (The ship that the Houthis tried to hit is the Ardmore Encounter tanker that carries the flag of the Marshall Islands.

Also reports of a shipping attack on the other Yemen coast near Oman. Quickly becoming a major disruption to world shipping.

◾️THE TOLL… we previously reported on 8 lost in battle, two more are reported killed yesterday as well - the worst day since the first day of the war. https://www.timesofisrael.com/ten-soldiers-including-two-senior-officers-killed-in-gaza-fighting-and-deadly-ambush/

◾️JENIN… (Arab city, West Bank, terror center) Firefights with IDF forces still going on, day and half continuous.

◾️FALSE ALERT - MODI’IN MACCABIM REUT… siren alert malfunction. Homefront Command is working to fix.

◾️INCREASING RESERVE AGE… the Ministry of Defense distributed a memorandum of law to increase the exemption age from reserve service to be raised in order to prevent damage to the IDF's combat capability in the midst of war. According to the plan, the exemption age will be increased by one year for regular soldiers, officers and certain positions.

◾️GAZA, WEAPONS EVERYWHERE (no innocent / civilian spaces)… Lt. Col. Oz, Nahal's 931st Brigade: We entered about 500 houses in Jabaliya. In 90% of them we found weapons, inside wardrobes, in the kitchen, in UNWRA sacks and under babies' beds. There were grenades, weapons, guns, rifles, RPGs and many other weapons. We arrived at the mosque, which apparently looked innocent. When we broke the door on the third floor, we were surprised to discover an advanced combat space there: they built a training facility there, like we train in the bases, they managed to build it in the mosque! We killed more than ten terrorists there.

◾️SOLDIERS MOTHER’S SAY… ( https://m.facebook.com/Mothers.Soldier ) "Our sons in battle, not Biden's son or Blinken's son - our soldier's life comes before the enemy's citizens.” Ilanit Dedosh, mother of a commander in Golani "Don't be influenced by foreign considerations - bomb from above.”

“We are in the most just war, against a cruel enemy who slaughtered, raped, massacred babies, women and hundreds of our brothers and sisters. We must trample him, and kill them to the last - and not stop until victory! We call on the IDF and the government - do not endanger our soldiers without a real operational need, do not put before your eyes any other consideration, not legal, not humanitarian or international pressure, Our sons are the ones in battle, not Biden's son nor Blinken's son, tell everyone in a clear voice - the lives of our soldiers come before the citizens of the enemy. We as mothers will not accept any risk to our soldiers that is not from operational considerations only. Loving, trusting, and strong - we are behind you! Fight until victory!" added the mothers. “You promised that you would not surrender and that you would not change the plan of action, do not endanger fighters in vain!”

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The #imperialism posts saying "Trump is fucking up the tools of US imperialism lol" have a point.

Where they overstate their case is attributing it to "not understanding anything". I understand that the current admin is incompetent, but this hasn't come out of nowhere and it does not take a grand plan.

The US right wing narrative since the Clinton administration has been a rejection of multilateralism, international consensus-seeking, and coalition-building.

Connotations of "equality" or "inclusivity" does not stop these from being key components in the form of imperialism contemporary Marxists describe in neoliberalism.

Whether US airstrikes in Kosovo would reduce or worsen ethnic cleansing of Armenians was not an important point of contention to the American right, nor was it which international partners called for or opposed the move. The important question was how much the airstrikes would cost and who was paying for it. The suggestion of concomitant benefits from 'trust among allies' or some 'rules-based international order' isn't something the GOP is unable to grasp, it is what they picture when you say 'imperialism'. The 'New World Order'. The 'Deep State'. An international consensus that has consistently ridiculed and rejected Republican politics as irrational, unprofitable, and unprincipled.

...and thus:

The Trump administration's international approach places strict bilateral transactions as the proper unit foreign policy is to be judged on. This is based on long, long-standing view of military support as a commodity the US was selectively 'selling' for free, as if exploiting US labour to maintain a monopoly - in the extreme of this view, any form of international law is a collusion towards anti-competitive business practices.

You can call this wrong (I sure do), you can call this stupid and immoral, but it is not just some individual eccentricity borne from late-imperial decay, and fascists don't identify with the establishment enough for it to be 'self-destructive' to them.

The state of their country is broken to them. There's some third definition of (Cold War era?) American Empire they are trying to revive.

Meanwhile, the world jeers at them and the British are just nodding in a corner like "yeah this is why you gotta grieve loss of your Empire properly. They've been taking it really hard since the US stopped being an empire and became a regular country. You know, sometime around WW1."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan Gordon

Reveling in Genre: An Interview with China Miéville

China Miéville was born on September 6, 1972, in Norwich, England, but has spent most of his life in London. King Rat (1998), his first novel, is a coming-of-age fantasy incorporating folk tales and drum’n’bass music into an action-packed quest. His second novel, Perdido Street Station (2000), which he wrote while working on his PhD, received a great deal of critical attention, winning both the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the British Fantasy Award, and being short-listed for the World Fantasy Award. The Scar (2002), his third novel, also very well received, is a stand-alone sequel to Perdido Street Station, taking place in the same world but with different characters. Miéville is working on a third stand-alone novel set in that world. He has published several short stories and novellas, and is presently an editor of Historical Materialism, serving as special editor of a recent issue on Marxism and Fantasy (10.4 [2002]). In May 2003, he was Guest of Honor, along with Carol Emshwiller, at WisCon, the feminist sf convention. A committed Marxist, he ran for British Parliament in 2001 as the Socialist Alliance candidate. The photo of him that appears on both Perdido Street Station and The Scar fairly represents his strong physical presence—tall, muscular, and brooding. The man himself, however, is soft-spoken, humorous, and self-deprecating. The interview which follows is based on an email dialogue conducted between March 2002 and August 2003. It represents the current interests of a writer already accomplished but still near the beginning of his career.

Joan Gordon: Would you describe your childhood and education?

China Miéville: There were three of us in my family: my mum, my sister Jemima, and me, a close-knit single-parent family. I met my father maybe four times, but never really knew him, and he died about 8 years ago. We lived in north-west London, in a working-class, ethnically-mixed area called Willesden (where King Rat opens).

My parents were hippies, and the story is that they went through a dictionary looking for a beautiful word to name me. They nearly called me Banyan, but flipped a few pages on and reached “China,” thankfully. The other reason they liked it is that “china” is Cockney rhyming slang for “mate.” People say “my old china,” meaning “my old mate,” because “china plate” rhymes with “mate.”

We used to go to a lot of museums and art galleries, and we used to watch an awful lot of TV. We were pretty poor (my mother trained to be a teacher, which even when she qualified didn’t mean a whole lot of money), but from the age of eleven, I went to private school on scholarships. I had a great childhood. I was a bit of a geek and a bit anxious, but I had plenty of friends and interests, mostly sf-related-RPGs [role-playing games], reading, drawing, writing—and later, politics.

When I was 16 I went to boarding school for two years, which I loathed. I went to Cambridge University [in 1991] to read English, but quickly changed to Social Anthropology, receiving my degree in 1994. Then I worked for a while as sub-editor on a computer magazine, did a Masters in International Law from the London School of Economics (receiving the degree in 1995), spent a year at Harvard, and then received a PhD in Philosophy of International Law in 2001.

My dissertation is entitled A Historical Materialist Analysis of International Law and the Legal Form. It’s a critical history and theory of international law, drawing extensively on the work of the Russian legal theorist Yevgeny Pashukanis. Its direct influence on my novels has been very slight. There’s a reference to jurisprudence in Perdido Street Station which is drawn from it, and there’s something about a form of maritime law in The Scar, but that’s about it. The thesis is really an expression of a much broader theoretical interest and approach, which in turn informs the fiction, so to that extent, they’re both infused with a shared outlook.

JG: What cultural influences shaped your writing?

CM: My sister and I watched a hell of a lot of TV, which is partly why I don’t buy the argument that it stultifies children’s imaginations—I think it depends almost entirely on the context in which you’re watching it. British children’s TV in the 1970s and early 1980s was extremely good, and these days I often realize that something I’m writing is a riff from that early viewing. Programs I remember vividly include Doctor Who [1963-89], Chorlton and the Wheelies [1976-79], Blake’s 7 [1978-81], and Battle of the Planets [1978-79]. These days I’m a flat-out, awe-struck fan of Buffy the Vampire Slayer [1997-2003].

We didn’t see many films when I was young, but since my teens I’ve been watching more. I’m very tolerant of sf bubblegum (though the truly moronic, like Independence Day [Emmerich 1996] or Burton’s Planet of the Apes [2001], leaves me frigid). I loved The Matrix [Wachowski brothers 1999] and I’m sure I’m not the only writer who can feel its influence, especially in fight scenes. I loved the Alien franchise, particularly Alien [Scott 1979] and Alien3 [Fincher 1992] (which I think is very under-rated). I like most half-decent (and many completely un-decent) monster films. I like John Carpenter when he’s on form—I’ve seen Prince of Darkness [1987] probably more than any other film. In terms of influences, the aesthetic that I try to filch respectfully comes most from filmmakers like the Quay Brothers and Jan Švankmajer.

Probably one of the most enduring influences on me was a childhood playing RPGs: Dungeons and Dragons [D&D] and others. I’ve not played for sixteen years and have absolutely no intention of starting again, but I still buy and read the manuals occasionally. There were two things about them that particularly influenced me. One was the mania for cataloguing the fantastic: if you play them for any length of time, you get to know pretty much all the mythological beasts of all pantheons out there, along with a fair bit of the theology. I still love all that—I collect fantastic bestiaries, and one of the main spurs to write a secondary-world fantasy was to invent a bunch of monsters, half of which I’m sure I’ll never be able to fit into any books.

The other, more nebulous, but very strong influence of RPGs was the weird fetish for systematization, the way everything is reduced to “game stats.” If you take something like Cthulhu in Lovecraft, for example, it is completely incomprehensible and beyond all human categorization. But in the game Call of Cthulhu, you see Cthulhu’s “strength,” “dexterity,” and so on, carefully expressed numerically. There’s something superheroically banalifying about that approach to the fantastic. On one level it misses the point entirely, but I must admit it appeals to me in its application of some weirdly misplaced rigor onto the fantastic: it’s a kind of exaggeratedly precise approach to secondary world creation.

I’m conscious of the problems with that: probably my favorite piece of fantastic-world creation ever is the VIRICONIUM series by M. John Harrison [The Pastel City (1971), A Storm of Wings (1980), In Viriconium (1982), and Viriconium Nights (1984; rev. 1985)], which is carefully constructed to avoid any domestication, and which thereby brilliantly achieves the kind of alienating atmosphere I’m constantly striving for, so it’s not as if I think that quantification is the “correct” way to construct a world. But it’s one that appeals to the anal kid in me. To that extent, though I wouldn’t compare myself to Harrison in terms of quality, I sometimes feel as if, formally, my stuff is a cross between Viriconium and D&D.

JG: You mentioned being drawn to the systematization in RPGs. How do you see that in your writing?

CM: I start with maps, histories, time lines, things like that. I spend a lot of time working on stuff that may or may not actually find its way into the novel, but I know a lot more about the world than makes it into the stories. That’s the “RPG” factor: it’s about systematizing the world.

But though that’s my method, I don’t start with it. I don’t start with a bunch of graph papers and rulers. When I’m writing a book, generally I start with the mood and setting, along with a couple of specific images—things that have come into my head, totally abstracted from any narrative, that I’ve fixated on. After that, I construct a world, or an area, into which that general setting, that atmosphere, and the specific images I’ve focused on can fit. It’s at that stage that the systematization begins for me.

I hope this doesn’t sound pompous, but that’s how I see the best weird fiction as the intersection of the traditions of Surrealism with those of pulp. I don’t start with the graph paper and the calculators like a particular kind of D&D dungeonmaster: I start with an image, as unreal and affecting as possible, just like the Surrealists. But then I systematize it, and move into a different kind of tradition.

I grew up with a love for the Surrealists which has never faded: in particular, the works of Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Hans Bellmer, and Paul Delvaux, along with those adopted by or close to the Surrealists, like Edward Burra, James Ensor, and Frida Kahlo. Graphic artists like Piranesi, Dürer, Escher, Bellmer’s pen-and-ink work, Mervyn Peake, Tenniell, and so on, are influential. As to modern comics and graphic art, I admire David Sandlin, Charles Burns, Kim Dietsch, Julie Doucet, and Chris Ware; from the post-punk comics underground, Burne Hogarth; and more mainstream British children’s comic artists like Ken Reid. I draw myself, pen and ink stuff, often illustrating my own stories.

I was always into everything to do with sf, fantasy, horror (as well as things set under the sea, which, along with dinosaurs, is honorary fantasy). I grew up on children’s sf by people like Douglas Hill and Nicholas Fisk, as well as horror comics, which were, in retrospect, deeply odd and unpleasant. Michael de Larrabeiti’s BORRIBLES books [The Borribles (1976), The Borribles Go For Broke (1981), and Across the Dark Metropolis (1986)] were massively influential. When I was a kid I read pretty much any sf I could get my hands on, so there was a lot of good pulp along with the classics—people like Lloyd Biggle, Jr. and Linsday Gutteridge—and that reveling in genre influenced me a lot. I read a review of Perdido Street Station which said that for a Clarke winner it’s surprisingly unashamed of its roots, which I take as a massive compliment. Overall, though, what I liked best was the aesthetic of alienation, of the macabre and grotesque, so I preferred New Worlds-type stuff to American Golden Age: Aldiss, Harrison, Moorcock, Disch, Ballard, and the like are all heroes of mine.

I still find myself riffing off books from my past constantly, sometimes without remembering what I’m basing my writing on. New Crobuzon [the setting of Perdido Street Station] is highly influenced by Brian Aldiss’s The Malacia Tapestry [1976] and Tim Powers’s Anubis Gates [1983], but they’d permeated me so deeply I was initially less conscious of them than of other influences. The very first (never-ever-to-see-the-light-of-day) New Crobuzon story I wrote was about the invention of photography in a fantasy city—which is precisely the plot of Aldiss’s book. I’d forgotten that I was remembering it. I’m still scared of inadvertently ripping people off.

I always loved classic ghost stories, like Henry James’s and Robert Aikman’s. I liked Lovecraft, and then maybe eight years ago I started getting very interested in early weird fiction: Arthur Machen, Robert Chambers, E.H. Visiak, William Hope Hodgson, Clark Ashton Smith, David Lindsay (though he’s not in quite the same tradition, there are shared aesthetics). There were two things I found particularly compelling about this work. One was the peculiarities of pulp style. If you look at the way critics describe Lovecraft, for example, they often say he’s purple, overwritten, overblown, verbose, but it’s unputdownable. There’s something about that kind of hallucinatorily intense purple prose which completely breaches all rules of “good writing,” but is somehow utterly compulsive and affecting. That pulp aesthetic of language is something very tenuous, which all too easily simply becomes shit, but is fascinating where it works. Though I also love much more minimalist writers, it’s that lush approach that I’m drawn to in terms of my own writing, for good and bad.

The other thing I liked about weird fiction was its location at the intersection of sf, fantasy, and horror. Lovecraft’s monsters do magic, but they’re time-traveling aliens with über-science, who do horrific things. Hodgson’s are similar (though less scientifically savvy). David Lindsay’s “spaceship” travels back to Arcturus by totally spurious—and not even remotely convincing—science, but it masquerades as sf. I find that bleeding of genre edges completely compelling. There’s been a (to my mind rather scholastic and sterile) debate about whether Perdido Street Station is sf or fantasy (or even horror—it made the long-list for the Bram Stoker Award). I always say that what I write is weird fiction, in that it is self-consciously at the intersection.

Some writers loom in my consciousness for single works, some for their whole oeuvre. M. John Harrison I consider one of the greatest living writers in any genre, and his influence on me is immense. Mervyn Peake, for his combination of lush language and aesthetic austerity; Gene Wolfe, for oddly similar reasons; all of Iain Sinclair’s books, but particularly Downriver [1991]; Alasdair Gray, especially Lanark [1981]; Russell Hoban, especially Riddley Walker [1980]; a book called Junglist by people calling themselves “Two Fingers” and “James T. Kirk” [1997]. I find Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre [1847] continually astonishing.

I love short stories, and there are writers like Borges, Calvino, and Stefan Grabinski whose short work is a constant reference, but there are others who loom large for me on the strength of a single piece: Julio Cortazar’s “House Taken Over,” E.L. White’s “Lukundoo,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Saki’s “Sredni Vastar.” I just finished Kelly Link’s collection Stranger Things Happen [2001], and can already feel her influencing me. Writers I’ve come to more recently include John Crowley, Unica Zürn (Hans Bellmer’s partner), Jeff VanderMeer, and Jeffrey Thomas.

The biggest recent influence on me, though, is not an sf writer: it’s the Zimbabwean Dambudzo Marechera, who died fourteen years ago. I first read him a decade ago, but came back to him recently and read all his published work. He’s quite astonishing. His influences are radically different from the folklorist tradition that one often associates with African literature. He writes in the tradition of the Beats, the Surrealists, the Symbolists, and he marshals their tools to talk about the freedom struggle, the iniquities of post-independence Zimbabwe, racism, loneliness, and so on. His poetry and prose are almost painfully intense and suffer from all the problems you’d imagine—the writing can be prolix and clunky—but the way he constantly wrestles with English (which wasn’t his first language) is extraordinary. He demands sustained effort from the reader, so that the work is almost interactive—reading it is an active process of collaboration with the writer—and the metaphors are simultaneously so unclichéd and so apt that he reinvigorates the language. The epigram to The Scar is taken from his most obscure book, Black Sunlight [1980], and he is a very strong presence throughout my recent writing.

JG: I want to turn the discussion from literary influences to your political involvement. Would you describe that involvement, discussing its effect on your writing?

CM: I was always left-wing, and from the age of about thirteen I’ve been involved in campaigns against nuclear weapons and apartheid, going on marches and demonstrations. Later, I became interested in postmodernist philosophy, but became very dissatisfied with it in my second year of university. I was studying anthropology, and I felt there was something theoretically disingenuous about postmodernism’s rejection of “grand narratives.” Specifically, its inability to deal with the cross-cultural nature of women’s oppression pissed me off, and for a brief while I turned to feminist theory. But I also felt there were serious lacunae in that tradition, and, while I continue to identify with feminism as a political struggle, I was unsatisfied by some of its theoretical blindspots.

At Cambridge there was an organization of Marxist students, and I’d been deeply impressed with the rigor and scope of their arguments, as well as their activism. Like most students, I knew that Marxism was teleological, outdated, and wrong, but I was stunned to find out that it wasn’t really any of those things, nor did it have the slightest connection with Stalinism. Two things in particular persuaded me of Marxism’s validity. One was that this theoretical approach dovetailed perfectly with my pre-existing political instincts and commitments, and gave them more rigor. The other was that Marxism— historical materialism—was theoretically all-encompassing: it allowed me to understand the world in its totality without being dogmatic. I’d felt, for example, that while feminist theory might have an explanation of gender inequality, it didn’t have much to offer on, say, international exchange rates. Marxism was able to make sense of all the various social phenomena from a unified perspective.

Although we revolutionary socialists are always accused of being utopian, nothing strikes me as more utopian than the reformist belief that with a bit of tinkering and some good faith, we can systematically improve the world. You have to ask how many decades of broken promises and failed schemes it will take to disprove that hope. Marxism isn’t about saying you’ll get a perfect world: it’s about saying we can get a better world than this one, and it’s hard to imagine, no matter how many mistakes we make, that it could be much worse than the mass starvation, war, oppression, and exploitation we have now. In a world where 30,000 to 40,000 children die of malnutrition daily while grain ships are designed to dump food into the sea if the price dips too low, it’s worth the risk.

For the last five years, I’ve been an activist with the International Socialist Tendency, and in a broader organization called the Socialist Alliance—as a member of which I stood for parliament in the recent general elections. I’m not an activist by predisposition but by conviction. Generally, I’d much rather be reading sf than being on a picket line, but I simply cannot believe that this world is the best we can do, and I can’t relax while it’s all we’ve got.

Socialism and sf are the two most fundamental influences in my life.

JG: Let’s turn to more specific discussion about your novels, and I’d like to begin by asking about your first novel, King Rat. Why did you choose drum’n’bass/jungle music as the musical score for the novel?

CM: I chose it because I love it. It’s rhythmically, thematically, aesthetically powerful. It’s a music constructed on theft, it’s a mongrel of a hundred snatches of stolen music. That’s what sampling is. And there are places in King Rat where I snatched a bunch of real lyrics, and looped them over each other, so the writing mimicked the music. It wasn’t entirely conscious, though—consciously, I was trying to mimic the rhythm of the music. Drum’n’bass is a music born out of the working-class—and unemployed—culture in London. Obviously it’s politically important to me not to pathologize, demonize, or fetishize working-class culture, but I didn’t choose to use it for political reasons so much as because it’s where the music’s at.

JG: The story of the Pied Piper of Hamlin is central to the novel, and the African trickster Anansi is there as well. Would you expand on your use of folk tales and myths in King Rat?

CM: All the animal superiors came from various mythic or artistic influences. The Anansi in the book is more the spider in his West Indian incarnation. The King of the Cats is mentioned, who’s a fairy tale figure (and also refers to An Arabian Nightmare by Robert Irwin [1983]). Kataris, Queen Bitch, is a demon in charge of dogs from a pantheon I can’t remember. Loplop, Bird Superior, is a character from Max Ernst’s paintings. Lord of the Flies refers to the novel of that name [by William Golding 1959], of course. All the animals in the novel have their own boss, and you’ve got figures from African, European, mythic, and artistic traditions all mixed up.

JG: The London Underground—what I’d call the subway system in the US—forms a series of metaphors for much of what goes on in the novel, from the use of subterranean settings, to its secret (underground) history of London, to the underground music scene. Would you discuss that?

CM: There’s a whole tradition of “underground London” books, of which Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere [1998] is probably the most well-known and successful. Partly it’s because it’s such an old city, and it’s been constructed on top of earlier layers. There are rivers that have been covered up by the city, and tunnels and construction, of which the tube (the subway trains) are a relatively recent but culturally weighty addition. Of course, the idea of things lurking around below the surface is such a potent image it’s no surprise that it features heavily in literature.

There’s something particularly powerful about the underground trains in London. They’re the oldest subway network in the world, and they are an absolutely central part of London culture. The tube map has become incredibly iconic. The very names of stations and train lines loom very large in our culture, so they were ripe to be pilfered. The details I wrote were right at the time—there’s a scene set in Mornington Crescent Station, which is particularly well-known in Britain because it features in a very popular radio comedy show [I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue]. Setting a violent and unpleasant scene there was kind of like pissing in a cozy bedroom.

JG: “Let’s put the ‘rat’ back into ‘Fraternity’” (317), Saul declaims at the end of King Rat. And you put fraternity into the novel. How and why is that an important theme in the novel?

CM: The “revolution” at the end of the novel is structured around the slogans of the French Revolution, not the Bolshevik revolution, which has been flagged through references to Lenin earlier in the novel. In other words, for those who’ve read a bit of Marxist theory, it is a bourgeois revolution, rather than a socialist one. It’s not a really happy ending, in that the rats, if they follow through on Saul’s suggestion, won’t usher in any kind of utopia, but will only get to where we humans are now.

JG: Turning to Perdido Street Station, how is it a London novel?

CM: In a very straightforward way, the city of New Crobuzon is clearly analogous to a chaos-fucked Victorian London. But it’s more than just the geography (river straddling, near the coast) and the industry (heavy, riddled with class conflict). It’s the way the city intersects with the literature that chronicles it. London is a trope for literature in an incredibly strong way: “Hell is a city much like London,” Shelley says, and through Blake and de Quincey, and Iain Sinclair, and Chesterton, and Machen, and Ackroyd, and Gaiman, and all the others, London is a neurotic tic for literature. Take those ideas—the danger, the intricacy, the mystery, the rich fecundity, the semi-autonomous architecture—and magic/surreal/acid it up a bit: that’s New Crobuzon. Though New Crobuzon contains other cities—Cairo in particular—it’s London at heart.

JG: John Clute talks about British sf being about ruins, expressing a pessimism about expansionism gone wrong (at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, March 2002). Can you speak to that in terms of Perdido Street Station?

CM: Post-New Worlds sf is partly pessimistic, but it’s more melancholic than miserable. It rather likes being in the ruins. I love that aesthetic, and it’s what I grew up on. I think, though, that Perdido Street Station is a little more muscular than that. It’s more pulpy, in what I hope are good as well as bad ways. Where the characters of New Worlds writers—who are my heroes—had “breakfast among the ruins,” the people in New Crobuzon busily build some other piece of shit using parts of the ruins. The ruins are still there, but I think that there’s more dynamism towards the environment. This is emphatically not a criticism of the earlier writers—it’s just an observation about a distinction of approach.

JG: Is Perdido Street Station in some way a child of Thatcherite, or Majorite, or Blairite England?

CM: I think you have to disaggregate them. Very crudely, I think that the New Worlds writers are writers of social collapse, of a political downturn, of the closing down of possibilities, and of worsening tensions without much of a sense of alternative, though I think their pessimism isn’t as straightforward as it may appear to be. I think that what’s happened recently is that we still have the same aggressive, neoliberal, profit-driven, and anti-human agenda at the top, but there’s been an amazingly exciting sense of alternatives (the protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle in 2000 form a useful watershed) which was missing in the 1980s, and even through the 1990s. In the cultural milieu, that doesn’t translate into obviously political or “optimistic” sf, but it does inform it with what is perhaps a more powerful sense of social agency and interaction with both real and fictional landscapes. I don’t think my writing’s terribly optimistic, though I am.

JG: In what ways does the novel reflect or respond to the contemporary situation politically, aesthetically, personally, or otherwise?

CM: There are certain deliberate references: the dock strike by Vodyanoi dockers is a direct reference to the long-running labor dispute in Liverpool. There are general points about the depiction of social tensions and so on. But I don’t write fiction to comment on the day-to-day situation, so I think the bulk of the response or reflection is in that generalized way I spoke of in the last answer. I think it’s to do with coming to terms with a new sense of social agency.

JG: In what ways does the novel develop or explore Marxism? How does it bring Marxism into a contemporary perspective? Is there a kind of postmodern Marxism and, if so, is it at work in Perdido Street Station?