#Timoclea

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Your top 5 Alexander the Great moments?

Top Five Alexander Moments

One issue with answering this is to figure out what events actually happened, especially when it comes to anecdotes! Here are four I find either significant to understanding his charisma and/or which explain how he functioned and why he was successful, plus one I like just because I’m a horse girl.

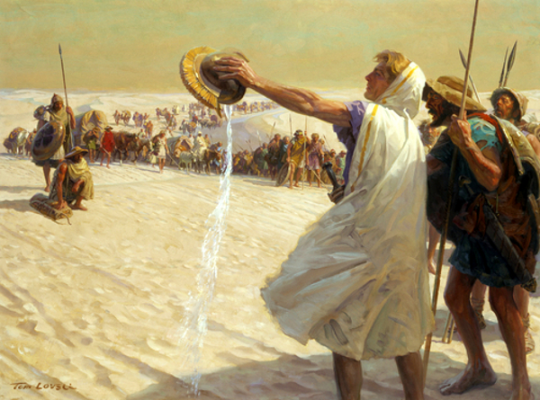

1) To my mind, the event that best illustrates why his men followed him to the edge of their known world occurred in the Gedrosian Desert. While I’m a bit dubious that this trek was as bad as it’s made out to be (reasons exist for exaggerating), it was still baaaad. One story relates that some of his men found some brackish water in a sad little excuse for a spring, gathered it in a helm, and brought it to him. Given his poor physical condition after the Malian siege wound, he no doubt needed it badly. He thanked them (most sincerely), then carried it out where all (or at least a lot) of his men could see, raised it overhead, and announced that until all of them could drink, he wouldn’t. Then he poured it onto the rocky ground.

That gesture exemplified his charisma. And it absolutely is not something the likes of a Donald tRump could even imagine doing—nor most dictators, tbh. They’d be blaming everybody else and calling for heads while drinking Diet Coke, not suffering alongside their people.

This wasn’t an isolated event of that type. While he almost certainly didn’t have time to engage along with his soldiers in every project, we’re told he would drop in from time-to-time, to inspire them and to offer a little friendly competition.

He also dressed like his men for everyday activities, especially early in the campaign. As time went on, some sources say he inserted more distance—probably necessary as his duties exploded—but he still seems to have found time to “just hang out” with his Macedonians on occasion. The claims that he was too high and mighty to do so appears to have been exaggeration (as such accusations often are) in order to forward a narrative that he was “going Asian.” Troop resentment over court changes was very genuine—I don’t want to underplay it (especially as I’ve written about it in a few chapters in this), but it tended to boil up during certain periods/events, then die back again. Alexander was trying to walk a very fine line of incorporating the conquered while not ticking off his own people.

2) Reportedly, he once threw a man out of line because he hadn’t bothered to secure the chin strap on his helm. I pick this one because it tells me a whole lot about how he saw himself as a commander, and what he expected of his men (and why he tended to consistently win).

On the surface, his reaction seems almost petty. It’s precisely the sort of mistake students whine about when professors ding them for it. It’s just a chin strap! I’d have tightened it before I went into battle! (It’s just a few typos; you knew what I meant! Or, Why does everything in the bibliography have to be exactly matching in style? Who cares? What a stupid thing to obsess about!) These objections are all of a piece. First, they’re lazy, and second, they indicate a disconcern with details. In battle, such disconcern can get a person killed. And on a larger scale, for a general, such disconcern loses battles.

One of the striking aspects of Alexander’s military operations was just how well his logistics worked. Consistently. We hear little about them precisely because they rarely fail. Food and water was there when they needed it, as were arrow replacements, wood to repair the spears, wool and leather for clothes and shoes, canvas for tents, etc., etc. All those little niggling (boring) details. If these are missing, soldiers become upset (and don’t fight well). Starting with Philip, the Macedonian military was a well-oiled machine. That’s WHY Gedrosia was such a shock: the logistics collapsed. Contra some historians, he did not do it to “punish” his men, nor to best Cyrus.* He had a sound reason—to scout a trade route.

Alexander understood that details matter. It starts with a loose chinstrap. (Or an unplanned-for storm and rebellion in his rear.) Everything else can unravel from that.

3) Alexander sends Hephaistion a little dish of small fish (probably smelts). He also helps an officer secure the lady of his dreams. And writes another on assignment (away from the army) that a mutual friend is recovering from an illness. While technically three “moments,” these are all of a piece. Alexander knows his men, and is concerned not only for their physical well-being, but also their mental state: that they’re happy. Granted, these are all elite officers, but it suggests he’s paying attention to people. I’ve always assumed he sent Hephaistion the fish because they were his friend’s favorite, and/or they were a special treat and he wanted to share. That he didn’t punish an officer for going AWOL to chase the mistress he wanted but offered advice, and even assistance, on how to court and secure her suggests the same care.

I don’t want to take away from what appears to be his serious anger management problems(!), but little details like those above strike me as the likeable side of Alexander—why his men were so devoted to him.

4) Then we have the encounter with Timokleia after the siege of Thebes. While probably a bit too precious to have occurred exactly as related, I think it may still hold a kernel of truth.

Alexander had a reputation of chivalry towards his (highborn) female captives. If some of that was likely either propaganda from his own time or philhellenic whitewashing later by Second Sophistic authors such as Plutarch (and Arrian), poor treatment of women is not something we hear attributed to him.

Ergo, while the meeting was probably doctored for a moral tail, he may well have freed Timokleia as an act of clemency to put a better face on a shocking destruction he knew wouldn’t sit well with the rest of Greece—who he both wanted to cow yet earn support from. (A difficult balancing act.) Also, if Timokleia hadn’t been high-born, she’d probably have been hauled off to one of the prisoner cages with little fanfare.

Nonetheless, I find his actions surprising given the casual misogyny of his era. If we can take the bare bones of the story as true, and it’s not all invented, Timokleia was raped as a matter of course during the sacking of Thebes, then managed to trick her rapist and kill him by pushing him down a well and dropping rocks on him. I assume this happened when his men weren’t there, but they found out soon enough and hauled her in front of Alexander to be punished for killing an officer. To the surprise of all, Alexander decided the man had earned it and freed Timokleia. One might be inclined to call this overly sentimental, but….

There’s a similar story that occurred much later in the Levant, when two of Parmenion’s men seduced/(raped?) the mistresses/wives of some mercenaries. Alexander instructed Parmenion to kill the Macedonians if they were found to be guilty.

In both cases, we have an affront against (respectable) women. In the latter case, Alexander was (no doubt) working to avoid conflict between hired soldiers and his own men, who—in typical Greek fashion—would have looked down on mercenaries as a matter of course. Some sort of conflict between Macedonians and Greek mercenaries up in Thrace had almost got Alexander’s father killed. Alexander saved him. No doubt that was on Alexander’s mind here.

Yet what both events illuminate is a willingness on Alexander’s part to punish his own men for affronts to honor/timē that involved women. Yes, this is clearly about discipline. But it also shows an unusual sensitivity to sex crimes in warfare: actions that would normally fall under the excuse of “boys will be boys” (especially when their blood is up).

I doubt he’d have felt the same about slaves or prostitutes; he was still a product of his time. Yet without overlooking his violence—sometimes extreme (the genocide of the Branchidai, for instance)—I find his reaction in these cases to be evidence of an atypical sympathy for women that I’d like to think isn’t wholly an invention of later Roman authors. And just might show the influence of his mother and sisters.

5) Last… the Boukephalas story…because who doesn’t love a good “a boy and his horse” tale? Obviously the Plutarchian version is tweaked to reflect that author’s later concern to contrast the Macedonian “barbarian” Philip with the properly Hellenized Alexander. Ignore the editorializing remarks, especially the “find a kingdom big enough for you” nonsense.

But the bare bones of the story seem likely: unmanageable horse, cocky kid, bet with dad, gotcha moment. You can imagine this was an anecdote Alexander retold a time or three, or twenty.

——

* His attempts to copy Cyrus may be imposition by later writers. In his own day, he may have cared more about the first Darius, for reasons Jenn Finn is going to explain in a forthcoming, very good article on the burning of Thebes and Persepolis.

#asks#Top Five Alexander the Great moments#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Timoclea#Timoklea#Boukephalas#Bucephalas#Gedrosian Desert#ancient military logistics#Macedonian army#Alexander's logistics#Classics#ancient history#campaigns of Alexander the Great#tagamemnon

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unhinged Feral Feminine Rage

Men Don’t Know Anger as Intimately as Women Do

#aesthetic#greentearex withhoney’s playlists#playlist#greentearex-withhoney’s Playlists#greentearexwithhoney#feminine beauty#feminine rage#feminine anger#female rage#girl rage#rage#blessed with beauty and rage#amy dunne#judith#timoclea#kill bill#promising young woman#gone girl#hidden figures#devi vishwakumar#jennifers body#Spotify

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timoclea by Elisabetta Sirani

0 notes

Text

في عام ١٦٣٨، وُلدت إليزابيتا سيراني، الرسامة الإيطالية الباروكية التي أصبحت واحدة من أبرز الفنانات في بولونيا خلال العصور الحديثة. كانت من أوائل الن��اء اللاتي دخلن مجال الفن في المدينة، وأسست أكاديمية للفنانات، مما جعلها رائدة في هذا المجال. للأسف، توفيت في سن السابعة والعشرين في ظروف غامضة، تاركةً وراءها أعمالًا فنية لا تقدر بثمن.

اللوحة التي أعرضها اليوم مستوحاة من قصة قديمة رُويت عن تيموكليا، وهي امرأة اغتصبها قائد تراكيّ تحت قيادة الإسكندر الأكبر، الذي كان يدعى أيضاً ألكسندر. لكن تيموكليا لم تقبل بالظلم، بل واجهت المعتدي عليها بكل قوة، متظاهرةً بالخضوع بينما كانت تخطط للإنتقام. قالت له: "رغم أن كل شيء قد ضاع، فقد حافظت على جسدي من الإهانة". ثم أغوته إلى بئر فارغ، حيث قالت له إن هناك كنوزها مخبأة هناك. وعندما اقترب، دفعته إلى الأسفل وأغلقت عليه مصيره بحجارة ثقيلة.

في هذه اللوحة، تقدم سيراني تيموكليا كبطلة، بعيداً عن كونها مجرد هامش في قصة الإسكندر الأكبر. عادةً ما قلل الفنانون والمؤرخون الذكور من قصتها، معتقدين أن الإسكندر الأكبر عفا عنها بعدما اكتشف أن شقيقها كان جزءاً من وحدة عسكرية تتكون من ١٥٠ زوجاً من العشاق الذكور. لكن سيراني جعلت تيموكليا الشخصية المركزية في اللوحة.

ما يميز هذه اللوحة أيضاً هو أن سيراني أضافت توقيعها بجانب جرة الماء: "ELISAB. SIRANI. F."—وهو فعل نادر حتى بين معاصريها من الرجال في بولونيا، مما يعكس ثقتها الكبيرة في مكانتها كفنانة. من المؤسف أنها توفيت بعمرٍ صغير.

Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great

Elisabetta Sirani

1659

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female Rage in Paintings

Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi | Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist by Caravaggio | Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio | Jael and Sisera by Alessandro Turchi | Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Louis Finson | Jael slays Sisera by Ottavio Vannini | Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes by Orazio Gentileschi | La Douce Résistance by Michel Garnier | Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great by Elisabetti Sirani | Untitled by Jose Gabriel Alegría Sabogal | Salome Bearing the Head of Saint John the Baptist by an unknown copyist after c. 1631, originated from Guido Reni

#art#artist#artblr#artists#painting#art community#oil on canvas#oil painting#art gallery#classical art#classic academia#art history#dark academia#goth#gothic#feminism#feminist#strong female character#dark art#strong female lead#women empowerment#fine art#baroque#paintings#renaissance#historical painting#historical art#art blog#gothcore#chaotic academia

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Taylor Swift is a Female Rage icon? Get a Grip.

I’ve just received word that Taylor Swift is calling her show “Female Rage: The Musical.” Here is my very much pissed off response to that nonsense:

The phrase, Female Rage has an intimately rich history:

Some of the first accounts of female rage dates to the Italian renaissance. To be clear, women in those days were not allowed to become painters- the arts were seen as the domain of men. They did not believe that women have rich inner lives capable of delivering the type of artistic innovation with which renaissance men were obsessed.

However, rebels abounded, through the might of their fucking rage. Several women created some of the most compellingly emotional paintings I’ve ever fucking seen. They did it without permission, without financial support, and often under the threat of punishment. They did it as a protest. In paintings like “Timoclea Killing Her Rapist” by Elisabetta Sirani (1659), and another by Artemisia Gentileschi “Slaying of Holofernes” (1612) as it depicts the bravery of Judith as she slayed a traveling warlord out to rape Judith and enslave her city. The painting often is referred to as a way Artemisia was envisioning herself as slaying her rapist. These paintings were used against these women as proof that they were unfeminine- and far too angry. Both these women suffered immensely for their audacity to call attention to the violation men perpetrated on them. Female Rage bleeds off these paintings- bleeds right through to the bone-deep acknowledgement of the injustice women faced being barred from the arts and having their humanity violated in such a sick way. Both women were hated- and considered far too angry.

In philosophy, also as early as the 15th century, an example of female rage is a philosophical text, often hailed as one of the first feminists works in the western world, written by Christine de Pizan titled The City of Ladies (1405). She wrote in protest on the state of women- writing that “men who have slandered the opposite sex out of envy have usually know women who were cleverer and more virtuous than they are” (“The City of Ladies”). People mocked her all her life- but she stood fast to her convictions. She was widowed at a young age with children to feed and the men wouldn’t let women have jobs! She wrote this book and sold it so that she could feed her family- and to protest the treatment of women as lesser than men. Her work was called aggressive and unkempt- they said she was far too angry.

In the 18th century, a young Mary Wollstonecraft wrote, A Vindication of the Right of Women ( 1792) upon learning that the civil rights won in the French Revolution did not extend to women! She wrote in protest of the unjust ways other philosophers (like Rousseau) spoke about the state of women- as if they were lesser. She wrote to advocate for women’s right to education, which they did not yet have the right to! She wrote to advocate for the advancement of women’s ability to have their own property and their own lives! The reception of this text, by the general public, lead to a campaign against Wollstonecraft- calling her “aggressive” and far too angry.

Moving into modernity, the 1960’s, and into literary examples, Maya Angelou publishes I know why the caged Bird Sings (1969) in which she discusses the fraught youth of a girl unprotected in the world. It beautifully, and heart-wrenchingly, described growing up in the American South during the 1930’s as it subjected her to the intersection of racism and sexism. The story is an autobiographical account of her own childhood, which explains how patriarchal social standards nearly destroyed her life. Upon the reception of her book, men mostly called it “overly emotional” and far too angry. Maya Angelou persisted. She did not back down from the honesty with which she shared her life- the raw, painful truth. With Literature, she regained a voice in the world.

Interwoven into each of the examples I have pulled out here, is the underlying rage of women who want to be seen as human beings, with souls, dreams and hopes, yet are not seen as full members of society at the behest of men. They take all that rage, building up in their souls, and shift it to create something beautiful: positive change. Each of these cases, I have outlined above, made remarkable strides for the women as a whole- we still feel the impact of their work today. They were so god-damn passionate, so full of righteous anger, it burst out into heart-stopping, culture-shifting art. Feminine rage is therefore grounded in experiences of injustice and abuse- yet marked too by its ability to advocate for women's rights. It cannot be historically transmogrified away from these issues- though Taylor Swift is doing her best to assert female rage as pitifully dull, full of self-deprecation, and sadness over simply being single or losing money. She trivializes the seriousness with which women have pled their cases of real, painful injustice and suffering to the masses time and time again. The examples above deal with subjects of rape, governmental tyranny, and issues of patriarchally inspired social conditioning to accept women as less human than men. It is a deadly serious topic, one in which women have raised their goddamn voices for centuries to decry- and say instead, “I am human, I matter, and men have no right to violate my mind, body, or soul.”

The depictions of female rage over the last few centuries, crossing through many cultures, is an array of outright anger, fearsome rage, and into utter despair. The one unyielding, solid underpinning, however, is that the texts are depicting the complete agency of the women in question. The one uniting aspect of female rage is that it must be a reaction to injustice; instead of how male depictions of female rage function, (think Ophelia), the women are the agents of their art with female made- female rage. They push forth the meaning through their own will- not as subjects of male desires or abuses, but as their own selves. That is what makes the phrase so empowering. They are showing their souls as a form of protest to the men who treat women like we have no soul to speak of.

Taylor Swift’s so-called female rage is a farce in comparison. Let’s look at an example: “Mad Woman” (2020). I pull this example, and not something from her TTPD set, because this is one of the earliest examples of her using the phrase female rage to describe her dumb music. (Taylor Swift talking about "mad woman" | folklore : the long pond studio sessions (youtube.com)

The lyrics from “Mad Woman” read “Every time you call me crazy, I get more crazy/... And when you say I seem angry, I get more angry”

How exactly is agreeing with someone that you are “crazy” a type of female rage in which she’s protesting the patriarchy. The patriarchy has a long history of calling women “insane” if they do not behave according to the will of men. So, how is her agreeing with the people calling her crazy- at all subversive in the way that artworks, typically associated with concept of female rage, are subversive. What is she protesting? NOTHING.

Then later, she agrees, again, that she's “angry.” The issue I draw here is that she’s not actually explicating anything within the music itself that she’s angry about- she just keeps saying she's angry over and over, thus the line falls flat. The only thing this anger connects to is the idea of someone calling her angry- which then makes her agree that she is... angry. So, despite it being convoluted, it’s also just not actually making any kind of identifiable point about society or the patriarchy- so again, I beg, what on Earth makes this count as Female Rage?

In essence, she is doing the opposite of what the examples above showcase. In letting an outside, presumably male, figure tell Taylor Swift what she is feeling, and her explicit acceptance of feeling “crazy” and “angry,” she is ultimately corroborating the patriarchy not protesting it. Her center of agency comes from assignment of feelings outside of herself and her intrinsic agreement with that assignment; whereas female rage is truly contingent on the internal state, required as within our own selves, of female agency. As I stated above, the women making female rage art must have an explicit agency throughout the work. Taylor Swift’s song simply does not measure up to this standard.

Her finishing remarks corroborates the fact that she's agreeing with this patriarchal standard of a "mad" or crazy woman:

"No one likes a mad woman/ You made her like that"

Again, this line outsources agency through saying "you made her like that" thus removing any possibility of this song being legitimate female rage. There is simply no agency assigned to the woman in the song- nor does the song ever explicitly comment on a social issue or protestation of some grievous injury to women's personhood.

She honestly not even being clever- she's just rhyming the word “crazy” with “crazy.” Then later rhyming “angry” with “angry.” Groundbreaking stuff here.

Perhaps Taylor Swift is angry, in “Mad Woman,” but it is not the same type of rage established in the philosophical concept of female rage of which art historians, philosophers, and literary critics speak. Instead, it is the rage of a businesswoman that got a bad deal- but it is not Female Rage as scholars would identify it. In “Mad Woman” I fear her anger is shallow, and only centered on material loss- through damaging business deals or bad business partners. She is not, however, discussing what someone like Christine de Pizan was discussing by making a case for the concept that woman also have souls like men do. In her book, she had to argue that women have souls, because men were unconvinced of that. Do you see the difference? I am saying that Swift’s concerns are purely monetary and material, whereas true examples of female rage center on injustice done against their personhood- as affront to human rights. Clearly, both things can make someone mad- but I’d argue the violation of human rights is more serious- thus more deserving of the title “Female Rage.”

Simply put, Taylor Swift is not talking about anything serious, or specific, enough to launch her into the halls of fame for "Female Rage" art. She's mad, sure, but she's mad the way a CEO gets mad about losing a million dollars. She's not mad about women's position in society- or even just in the music industry.

She does this a lot. The album of “Reputation” was described as female rage. Songs in “Folklore” were described as female rage. Now, she’s using the term to describe TTPD, which is the most self-centered, ego-driven music I’ve heard in a long time.

Comparing the injustice, and complete subjugation, of women’s lives- to being dumped by a man or getting a bad deal- wherein she is still one of the most powerful women of the planet- is not only laughable, but offensive.

#anti taylor swift#taylor swift critical#ex swiftie#mad woman#folklore#maya angelou#christine de pizan#artemisia gentileschi#mary wollstonecraft#Elisabetta Sirani#art history#books and literature#feminist#feminism#female rage#taylor swift#activism#toxic swifties#toxic taylor swift#philosophy#fuck Rousseau#I'm a professional Taylor Swift Critic

660 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elisabetta Sirani Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great 1659 “According to Plutarch's biography of Alexander the Great, when his forces took Thebes during Alexander's Balkan campaign of 335 BC, Thracian forces pillaged the city, and a Thracian captain raped Timoclea. After raping her, the captain asked if she knew of any hidden money. She told him that she did, and led him into her garden, and told him there was money hidden in her well. When the Thracian captain stooped to look into the well, Timoclea pushed him down into it, and then hurled heavy stones down until the captain died.She was then seized by the Thracian soldiers and brought before Alexander. She comported herself with great dignity and told him that her brother was Theagenes, the last commander of the Sacred Band of Thebes, who died for the liberty of Greece at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, defeated by Alexander's father Philip of Macedon. Alexander was so impressed with Timoclea that he ordered her and her children released and she was not punished for killing the Thracian captain.”

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The painting, created in 1659 by Elisabetta Sirani, depicts Timoclea killing the Thracian captain. Timoclea, after being raped by the captain, pushes him into a well, resulting in his death. The work highlights Timoclea's revenge against her attacker. The painting is currently located in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples.

#art#art history#classical art#painting#oil painting#history of art#art by women#woman painter#woman artist#women in art

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Dr. Reames, I just have a question in regards to Alexander's approach to his soldiers treatment of women (I'm getting at sexual violence here) and what Alexander most likely handled such things. I think most of us know the story of how he praised Timoclea for her bravery after she was violated by one of his men, but what about other women? I remember reading (I'm pretty sure it was Diodorus) that when Alexander's army got to Darius's camp after the battle of Issus, Alexander's men "had their way" with some of the other women left behind. Who were these women? Servants? Noblewomen? And other similar instances that I'm sure I've read elsewhere. I guess what I'm asking is HOW likely is it that Alexander extended his chivalry to "common" women in his empire? I mean, there are some instances were he certainly was, as we would describe, chivalrous. He sent the women warriors that were offered to him (by Bessus I believe) in Arrian's Anabasis out of fear his men might "molest" them, and during the burning of Persepolis ordered his men not to touch the women of the city during the burning. I suppose I don't want to believe (for all his MANY faults) would allow such things to happen freely, as childish as that sounds.

Also if you can recommend some books (if you know of any I can get) that mention or discuss Alexander's approach to sexual assault in his empire that'd be great. Also I love your work and your YouTube channel!

Alexander and Female Prisoners of War

The treatment of women in war has always been horrendous. Full stop.

In the ancient world, the treatment of upper-class women was typically presented in the literature as a sign of the all-important clemency on the part of conquerors, whether they were Alexander, Scipio, Cyrus, etc.: “good men” who accorded “proper ladies” their social due.

One extremely important question we must ask is whether the depiction in literature accurately reflects what ACTUALLY happened. E.g., is it just a pretty story? To some degree, this is an unanswerable question. We weren’t there. In the case of Alexander, our (surviving) sources are largely late, so they weren’t there, either. And some of their sources weren’t there but relied on yet other accounts.

Think of these tales a bit like those “Introducing the Candidate” videos that political action committees put out to present Their Guy/Gal in glowing terms. Those videos may not be wholly false, but they’re also not entirely true. The degree to which they’re false or true obviously varies, depending on the person in question—an important point in this day of auto-cynicism. If few people in politics are Jimmy Stewart’s Mr. Smith (Goes to Washington), some really are there for (mostly) the right reasons.

We need to take a similar view of these tales from the ancient world. This is my usual pushing back against the same auto-cynicism among some of my historical colleagues. Nonetheless, even if we decide at least some of the stories about Alexander might be more true than false…

The treatment of women in war has always been horrendous. (as above)

For every Timoklea spared, there are a thousand nameless-to-history (if not to themselves) women who were raped, enslaved, and/or killed as a result of Alexander’s conquests. Yay, for Timoklea?

Via a modern lens, ancient warfare was almost unimaginably brutal. Modern war messes up people, sometimes/(often) for life. Ancient warfare was that on steroids. But I think it’s easy to forget how extremely precarious life was in the ancient world. War was, if not “common,” certainly not uncommon. Death was also much more in-your-face possible at any stage of life. Chance was understood to have a lot to do with it, and the favor of the gods, rather than anything inherently “good” in a person. Even while we do see folks in the ancient world trying to moralize bad luck, that’s more true in the ANE. In Greece and Rome, it was more about Luck, and Fate.

Today, I think the average person is very much cushioned from death. We rarely see dead bodies, and when we do, it’s in a casket at the funeral home. We’re not usually present when people die. We buy our meat prepackaged in the grocery story, without skin or offal and maybe even without any bones. We spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to preserve life, and to make living more comfortable and meaningful for the chronically ill, even for children born extremely disabled.

THAT WAS NOT THEIR WORLD. They’d be absolutely stunned (and arguably appalled) by the idea of saving a child with severe birth defects, or mortgaging one’s house to afford desperate measures to save somebody mangled in a car wreck and barely holding on to life. The kind thing, to their minds, would be to end the suffering ASAP. Who’d want to live like that? “Quality of life” had an entirely different meaning. And if, yes, the super-rich (like Alexander) might have been willing to pay anything to save the life of someone beloved (like Hephaistion), that wasn’t most people’s lived experience.

I point out all this to contextualize their perceptions of war, and war’s results. Resilience, or the ability to survive and recover from trauma, depends on a number of psychological factors, including having the event acknowledged as real, and the survivor’s preexisting ideas of a just (or unjust) world. One reason incest can be so incredible damaging is the secretiveness of it, and who did the assault (someone the survivor was taught to trust). Rape in war is done by a hated enemy and is not secret. That hardly makes it “better,” but it allows the survivor to process the trauma in a more straightforward way, and in the company of (many) others who have suffered the same. For women who wind up enslaved, rape will likely remain a normal part of their existence from then on, although the violence that accompanied it probably varied.

All of that led to a certain amount of hardened hearts, both to what happened to others, but also to what one suffered one’s self. It also explains why, in particularly brutal situations (such as sieges), entire families might elect suicide if the walls were breached—if they had time. This sort of whole-family suicide is mentioned in one of the accounts of Alexander’s razing of Persepolis, if I remember right. Also, some of the Indian sieges.

As for the well-born, and despite the fact the Greeks invented democracy, ancient Greece and Rome were still very much “class” societies. And more of Greece was NOT democratic than was. So the notion still existed that some women belonged—by “blood”—to a class who should be spared brutality, and elites and aristocrats were elites and aristocrats by virtue of special descent. Just as kings were kings by special descent. This might offend the modern mind, but not theirs. The children of slaves were born to be slaves; that was the “natural order of things.” But the children of the wealthy ruling class were born to rule, so when war intervened to reverse their fortunes, it was seen as especially sad. And that’s where clemency comes in.

It was a show of both admirable self-restraint and civilization for the victor to spare the (weaker) women and children of the defeated ruling group—to a point. After all, to be able to do so, he has already demonstrated his excellence in victory and has the POWER to offer clemency. That’s why clemency is a bit different from “grace” in a broader sense—and can be an insult for a man to accept. Caesar used it as a way to lord it over his enemies: “I could kill you...but I don’t respect you enough to fear you.” Also, clemency was often withheld from groups perceived to be “too barbarian.” They didn’t deserve it.

In any case, for upper-class female prisoners-of-war, acts of clemency, whether from the victor by freeing them, or from allies who offered ransom to rescue them from a life of slavery, became a sort of social coin. Not unlike starting a Go-Fund-Me today for a friend who’s fallen on hard times. One gets brownie points for the gesture…even if it 100% comes from a place of compassion. (Two motives can coexist at once in people.)

So, all of that may help to contextualize Alexander’s acts of clemency towards certain women who fell under his power. Was he actually more sensitive to captured women than most? I’m inclined to think he was. But I also recognize that such stories carried a lot of weight for later writers (such as Plutarch and Arrian) who had a particular picture of him that they wanted to paint.

That said, the fact he encouraged his soldiers to marry the camp followers with whom they’d had children, many of them women from the lands they conquered, and even offered dowries for the women is an uncommon act. It’s also weird enough, I suspect it’s not invention and points to an unexpected concern for women. We need to look “in the corners” of accounts about other matters, where clemency isn’t the point, to discover how atypical Alexander actually was.

So yes, he was (a little) ahead of his time. But I doubt he gave much thought to the plight of women in cities such as Thebes or Tyre or Persepolis, other than passing pity. Their fate was, to his mind, the fault of their male family members who chose to rebel against him—and a warning to others against resistance. There’s no point to the carrot without the threat of a whip, in ancient thought.

I don't know of any specific articles about this topic, although it's an interesting one. There are numerous articles about ATG and women more generally, many by Carney, Müller, D'Agostini, and (earlier) Greenwalt. But aside from an article by Müller on ATG's chivalry in the various medieval romances, I don't think anybody has directly examined the stories in earlier sources. Or, I take that back, Beth Carney wrote an article about women and warfare for the new Brill's Companion to the Campaigns of Philip II and Alexander the Great, and Sabine Müller wrote on war crimes more broadly, but I've not had time to read either chapter yet. The book literally just came out at the tail-end of last year. I bet they have some good bibliography to them.

#asks#Alexander the Great#clemency in Alexander histories#Alexander the Great's chivalry#ancient women#ancient women and warfare.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Problems with your mom's creepy childhood friend? Man making you apart of his Lolita/ Oedipus fantasy? Shove him through the Moon Door.

Adding to my earlier work of Sansa killing her abuser's based on historical art. This one is based on Timoclea (x)

#I wish my scanner didn't lighten the colors so much#I swear to God I gave Sansa an actual skin tone#sansa stark#alayne stone#petyr littlefinger baelish#petyr baelish#littlefinger#a game of thrones#agot#a song of ice and fire#asoiaf

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elisabetta Sirani Timoclea Killing Her Rapist 1659

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skreeeeee! HARPYCORPS’ print on demand shop is finally LIVE. We’re now in our 8th year of raising mutual aid funds for queer monstrous feminist activism and survival.

Theydies & gremlinfriends… I give you the TIMOCLEA 01/20/25:

Magnets. Totes. Stickers. Postcards. So many customizable options, sizes, and styles!

Depending on your color choice, you can go subliminal or bold with that spicy “GET IN THE BIN” text.

Big thanks to Melissa Dowell for designing my Xitter vintage meme as a wearable, stickable, tangible thang!

Mad love to Elisabetta Sirani. I’d like to think she’d approve!

FLY, MY PRETTIES, FLY

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! I am Cwenthryth of Northwice. I am a Scadian from central Ansteorra. I am a beginner at most things, but my interests are fencing, medieval magical practices and folk mythology, and early English and Stuart cultures.

My profile picture is "Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great" (1659) by Elisabetta Sirani.

My banner image is "Figures 11-12" from Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule (1573) by Henry de Sainct Didier.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great (1659), by Elisabetta Sirani

Timoclea confronts her assailant, feigning submission while plotting revenge. She laments her fate, telling him “that though all other things had been lost, I might have preserved my body free from abuse.” She then lures him to an empty well where her valuables are supposedly hidden, pushes him in, and seals his fate by hurling heavy stones after him.

In Sirani’s painting, Timoclea is the central figure rather than footnote in Alexander the Great’s saga. Male authors and artists often reduced her narrative to a minor anecdote about Alexander’s supposed magnanimity, as he spared Timoclea’s life upon learning her brother was part of famed military unit of 150 pairs of male lovers.

Sirani was also extraordinary in another way: she added her name to the stone next to water pitcher: “ELISAB. SIRANI. F.” — which was a rare fact even among her male contemporanies in Bologna. Sirani was confident and self-aware as an artist. It is a real shame that she died so early.

#the fact that i love sirani’s confidence and perspective of feminism aspects#elisabetta sirani#17th century#art#painting

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

the real female rage

( "Timoclea uccide il capitano di Alessandro Magno"— Elisabetta Sirani)

#girlblog#girly thoughts#this is what makes us girls#girlhood#girlblogging#girl blogging#going crazy#chronic pain#female histeria#hell is a teenage girl#im just a girl#female hysteria#female rage#feminine rage#female manipulator#girl things#im going insane#girl hysteria#girl blogger#girl thoughts#art#dark academia#this is a girlblog#chronic illness#history

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feminine rage in paintings

Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi | Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist by Caravaggio | Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio | Jael and Sisera by Alessandro Turchi | Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Louis Finson | Jael slays Sisera by Ottavio Vannini | Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes by Orazio Gentileschi | La Douce Résistance by Michel Garnier | Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great by Elisabetti Sirani | Salome Bearing the Head of Saint John the Baptist by un unknown copyist after c. 1631 originated from Guido Reni

#painting#baroque#baroque painting#art#literature#oil painting#renaissance#renaissance painting#vintage#dark academia#aesthetic#dark academic aesthetic#goth#gothic#historical#vintage art#whimsical#vintage painting#period#girl night

130 notes

·

View notes