#Timoklea

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Your top 5 Alexander the Great moments?

Top Five Alexander Moments

One issue with answering this is to figure out what events actually happened, especially when it comes to anecdotes! Here are four I find either significant to understanding his charisma and/or which explain how he functioned and why he was successful, plus one I like just because I’m a horse girl.

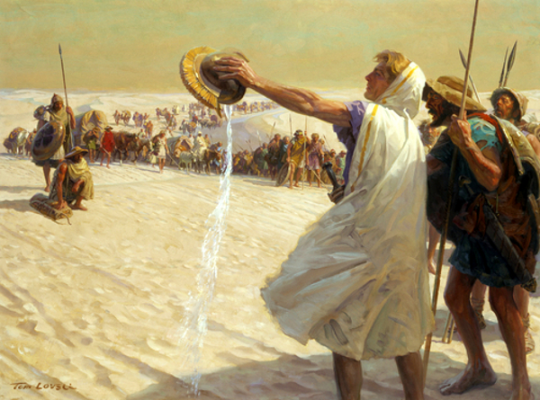

1) To my mind, the event that best illustrates why his men followed him to the edge of their known world occurred in the Gedrosian Desert. While I’m a bit dubious that this trek was as bad as it’s made out to be (reasons exist for exaggerating), it was still baaaad. One story relates that some of his men found some brackish water in a sad little excuse for a spring, gathered it in a helm, and brought it to him. Given his poor physical condition after the Malian siege wound, he no doubt needed it badly. He thanked them (most sincerely), then carried it out where all (or at least a lot) of his men could see, raised it overhead, and announced that until all of them could drink, he wouldn’t. Then he poured it onto the rocky ground.

That gesture exemplified his charisma. And it absolutely is not something the likes of a Donald tRump could even imagine doing—nor most dictators, tbh. They’d be blaming everybody else and calling for heads while drinking Diet Coke, not suffering alongside their people.

This wasn’t an isolated event of that type. While he almost certainly didn’t have time to engage along with his soldiers in every project, we’re told he would drop in from time-to-time, to inspire them and to offer a little friendly competition.

He also dressed like his men for everyday activities, especially early in the campaign. As time went on, some sources say he inserted more distance—probably necessary as his duties exploded—but he still seems to have found time to “just hang out” with his Macedonians on occasion. The claims that he was too high and mighty to do so appears to have been exaggeration (as such accusations often are) in order to forward a narrative that he was “going Asian.” Troop resentment over court changes was very genuine—I don’t want to underplay it (especially as I’ve written about it in a few chapters in this), but it tended to boil up during certain periods/events, then die back again. Alexander was trying to walk a very fine line of incorporating the conquered while not ticking off his own people.

2) Reportedly, he once threw a man out of line because he hadn’t bothered to secure the chin strap on his helm. I pick this one because it tells me a whole lot about how he saw himself as a commander, and what he expected of his men (and why he tended to consistently win).

On the surface, his reaction seems almost petty. It’s precisely the sort of mistake students whine about when professors ding them for it. It’s just a chin strap! I’d have tightened it before I went into battle! (It’s just a few typos; you knew what I meant! Or, Why does everything in the bibliography have to be exactly matching in style? Who cares? What a stupid thing to obsess about!) These objections are all of a piece. First, they’re lazy, and second, they indicate a disconcern with details. In battle, such disconcern can get a person killed. And on a larger scale, for a general, such disconcern loses battles.

One of the striking aspects of Alexander’s military operations was just how well his logistics worked. Consistently. We hear little about them precisely because they rarely fail. Food and water was there when they needed it, as were arrow replacements, wood to repair the spears, wool and leather for clothes and shoes, canvas for tents, etc., etc. All those little niggling (boring) details. If these are missing, soldiers become upset (and don’t fight well). Starting with Philip, the Macedonian military was a well-oiled machine. That’s WHY Gedrosia was such a shock: the logistics collapsed. Contra some historians, he did not do it to “punish” his men, nor to best Cyrus.* He had a sound reason—to scout a trade route.

Alexander understood that details matter. It starts with a loose chinstrap. (Or an unplanned-for storm and rebellion in his rear.) Everything else can unravel from that.

3) Alexander sends Hephaistion a little dish of small fish (probably smelts). He also helps an officer secure the lady of his dreams. And writes another on assignment (away from the army) that a mutual friend is recovering from an illness. While technically three “moments,” these are all of a piece. Alexander knows his men, and is concerned not only for their physical well-being, but also their mental state: that they’re happy. Granted, these are all elite officers, but it suggests he’s paying attention to people. I’ve always assumed he sent Hephaistion the fish because they were his friend’s favorite, and/or they were a special treat and he wanted to share. That he didn’t punish an officer for going AWOL to chase the mistress he wanted but offered advice, and even assistance, on how to court and secure her suggests the same care.

I don’t want to take away from what appears to be his serious anger management problems(!), but little details like those above strike me as the likeable side of Alexander—why his men were so devoted to him.

4) Then we have the encounter with Timokleia after the siege of Thebes. While probably a bit too precious to have occurred exactly as related, I think it may still hold a kernel of truth.

Alexander had a reputation of chivalry towards his (highborn) female captives. If some of that was likely either propaganda from his own time or philhellenic whitewashing later by Second Sophistic authors such as Plutarch (and Arrian), poor treatment of women is not something we hear attributed to him.

Ergo, while the meeting was probably doctored for a moral tail, he may well have freed Timokleia as an act of clemency to put a better face on a shocking destruction he knew wouldn’t sit well with the rest of Greece—who he both wanted to cow yet earn support from. (A difficult balancing act.) Also, if Timokleia hadn’t been high-born, she’d probably have been hauled off to one of the prisoner cages with little fanfare.

Nonetheless, I find his actions surprising given the casual misogyny of his era. If we can take the bare bones of the story as true, and it’s not all invented, Timokleia was raped as a matter of course during the sacking of Thebes, then managed to trick her rapist and kill him by pushing him down a well and dropping rocks on him. I assume this happened when his men weren’t there, but they found out soon enough and hauled her in front of Alexander to be punished for killing an officer. To the surprise of all, Alexander decided the man had earned it and freed Timokleia. One might be inclined to call this overly sentimental, but….

There’s a similar story that occurred much later in the Levant, when two of Parmenion’s men seduced/(raped?) the mistresses/wives of some mercenaries. Alexander instructed Parmenion to kill the Macedonians if they were found to be guilty.

In both cases, we have an affront against (respectable) women. In the latter case, Alexander was (no doubt) working to avoid conflict between hired soldiers and his own men, who—in typical Greek fashion—would have looked down on mercenaries as a matter of course. Some sort of conflict between Macedonians and Greek mercenaries up in Thrace had almost got Alexander’s father killed. Alexander saved him. No doubt that was on Alexander’s mind here.

Yet what both events illuminate is a willingness on Alexander’s part to punish his own men for affronts to honor/timē that involved women. Yes, this is clearly about discipline. But it also shows an unusual sensitivity to sex crimes in warfare: actions that would normally fall under the excuse of “boys will be boys” (especially when their blood is up).

I doubt he’d have felt the same about slaves or prostitutes; he was still a product of his time. Yet without overlooking his violence—sometimes extreme (the genocide of the Branchidai, for instance)—I find his reaction in these cases to be evidence of an atypical sympathy for women that I’d like to think isn’t wholly an invention of later Roman authors. And just might show the influence of his mother and sisters.

5) Last… the Boukephalas story…because who doesn’t love a good “a boy and his horse” tale? Obviously the Plutarchian version is tweaked to reflect that author’s later concern to contrast the Macedonian “barbarian” Philip with the properly Hellenized Alexander. Ignore the editorializing remarks, especially the “find a kingdom big enough for you” nonsense.

But the bare bones of the story seem likely: unmanageable horse, cocky kid, bet with dad, gotcha moment. You can imagine this was an anecdote Alexander retold a time or three, or twenty.

——

* His attempts to copy Cyrus may be imposition by later writers. In his own day, he may have cared more about the first Darius, for reasons Jenn Finn is going to explain in a forthcoming, very good article on the burning of Thebes and Persepolis.

#asks#Top Five Alexander the Great moments#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Timoclea#Timoklea#Boukephalas#Bucephalas#Gedrosian Desert#ancient military logistics#Macedonian army#Alexander's logistics#Classics#ancient history#campaigns of Alexander the Great#tagamemnon

59 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Dr. Reames, I just have a question in regards to Alexander's approach to his soldiers treatment of women (I'm getting at sexual violence here) and what Alexander most likely handled such things. I think most of us know the story of how he praised Timoclea for her bravery after she was violated by one of his men, but what about other women? I remember reading (I'm pretty sure it was Diodorus) that when Alexander's army got to Darius's camp after the battle of Issus, Alexander's men "had their way" with some of the other women left behind. Who were these women? Servants? Noblewomen? And other similar instances that I'm sure I've read elsewhere. I guess what I'm asking is HOW likely is it that Alexander extended his chivalry to "common" women in his empire? I mean, there are some instances were he certainly was, as we would describe, chivalrous. He sent the women warriors that were offered to him (by Bessus I believe) in Arrian's Anabasis out of fear his men might "molest" them, and during the burning of Persepolis ordered his men not to touch the women of the city during the burning. I suppose I don't want to believe (for all his MANY faults) would allow such things to happen freely, as childish as that sounds.

Also if you can recommend some books (if you know of any I can get) that mention or discuss Alexander's approach to sexual assault in his empire that'd be great. Also I love your work and your YouTube channel!

Alexander and Female Prisoners of War

The treatment of women in war has always been horrendous. Full stop.

In the ancient world, the treatment of upper-class women was typically presented in the literature as a sign of the all-important clemency on the part of conquerors, whether they were Alexander, Scipio, Cyrus, etc.: “good men” who accorded “proper ladies” their social due.

One extremely important question we must ask is whether the depiction in literature accurately reflects what ACTUALLY happened. E.g., is it just a pretty story? To some degree, this is an unanswerable question. We weren’t there. In the case of Alexander, our (surviving) sources are largely late, so they weren’t there, either. And some of their sources weren’t there but relied on yet other accounts.

Think of these tales a bit like those “Introducing the Candidate” videos that political action committees put out to present Their Guy/Gal in glowing terms. Those videos may not be wholly false, but they’re also not entirely true. The degree to which they’re false or true obviously varies, depending on the person in question—an important point in this day of auto-cynicism. If few people in politics are Jimmy Stewart’s Mr. Smith (Goes to Washington), some really are there for (mostly) the right reasons.

We need to take a similar view of these tales from the ancient world. This is my usual pushing back against the same auto-cynicism among some of my historical colleagues. Nonetheless, even if we decide at least some of the stories about Alexander might be more true than false…

The treatment of women in war has always been horrendous. (as above)

For every Timoklea spared, there are a thousand nameless-to-history (if not to themselves) women who were raped, enslaved, and/or killed as a result of Alexander’s conquests. Yay, for Timoklea?

Via a modern lens, ancient warfare was almost unimaginably brutal. Modern war messes up people, sometimes/(often) for life. Ancient warfare was that on steroids. But I think it’s easy to forget how extremely precarious life was in the ancient world. War was, if not “common,” certainly not uncommon. Death was also much more in-your-face possible at any stage of life. Chance was understood to have a lot to do with it, and the favor of the gods, rather than anything inherently “good” in a person. Even while we do see folks in the ancient world trying to moralize bad luck, that’s more true in the ANE. In Greece and Rome, it was more about Luck, and Fate.

Today, I think the average person is very much cushioned from death. We rarely see dead bodies, and when we do, it’s in a casket at the funeral home. We’re not usually present when people die. We buy our meat prepackaged in the grocery story, without skin or offal and maybe even without any bones. We spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to preserve life, and to make living more comfortable and meaningful for the chronically ill, even for children born extremely disabled.

THAT WAS NOT THEIR WORLD. They’d be absolutely stunned (and arguably appalled) by the idea of saving a child with severe birth defects, or mortgaging one’s house to afford desperate measures to save somebody mangled in a car wreck and barely holding on to life. The kind thing, to their minds, would be to end the suffering ASAP. Who’d want to live like that? “Quality of life” had an entirely different meaning. And if, yes, the super-rich (like Alexander) might have been willing to pay anything to save the life of someone beloved (like Hephaistion), that wasn’t most people’s lived experience.

I point out all this to contextualize their perceptions of war, and war’s results. Resilience, or the ability to survive and recover from trauma, depends on a number of psychological factors, including having the event acknowledged as real, and the survivor’s preexisting ideas of a just (or unjust) world. One reason incest can be so incredible damaging is the secretiveness of it, and who did the assault (someone the survivor was taught to trust). Rape in war is done by a hated enemy and is not secret. That hardly makes it “better,” but it allows the survivor to process the trauma in a more straightforward way, and in the company of (many) others who have suffered the same. For women who wind up enslaved, rape will likely remain a normal part of their existence from then on, although the violence that accompanied it probably varied.

All of that led to a certain amount of hardened hearts, both to what happened to others, but also to what one suffered one’s self. It also explains why, in particularly brutal situations (such as sieges), entire families might elect suicide if the walls were breached—if they had time. This sort of whole-family suicide is mentioned in one of the accounts of Alexander’s razing of Persepolis, if I remember right. Also, some of the Indian sieges.

As for the well-born, and despite the fact the Greeks invented democracy, ancient Greece and Rome were still very much “class” societies. And more of Greece was NOT democratic than was. So the notion still existed that some women belonged—by “blood”—to a class who should be spared brutality, and elites and aristocrats were elites and aristocrats by virtue of special descent. Just as kings were kings by special descent. This might offend the modern mind, but not theirs. The children of slaves were born to be slaves; that was the “natural order of things.” But the children of the wealthy ruling class were born to rule, so when war intervened to reverse their fortunes, it was seen as especially sad. And that’s where clemency comes in.

It was a show of both admirable self-restraint and civilization for the victor to spare the (weaker) women and children of the defeated ruling group—to a point. After all, to be able to do so, he has already demonstrated his excellence in victory and has the POWER to offer clemency. That’s why clemency is a bit different from “grace” in a broader sense—and can be an insult for a man to accept. Caesar used it as a way to lord it over his enemies: “I could kill you...but I don’t respect you enough to fear you.” Also, clemency was often withheld from groups perceived to be “too barbarian.” They didn’t deserve it.

In any case, for upper-class female prisoners-of-war, acts of clemency, whether from the victor by freeing them, or from allies who offered ransom to rescue them from a life of slavery, became a sort of social coin. Not unlike starting a Go-Fund-Me today for a friend who’s fallen on hard times. One gets brownie points for the gesture…even if it 100% comes from a place of compassion. (Two motives can coexist at once in people.)

So, all of that may help to contextualize Alexander’s acts of clemency towards certain women who fell under his power. Was he actually more sensitive to captured women than most? I’m inclined to think he was. But I also recognize that such stories carried a lot of weight for later writers (such as Plutarch and Arrian) who had a particular picture of him that they wanted to paint.

That said, the fact he encouraged his soldiers to marry the camp followers with whom they’d had children, many of them women from the lands they conquered, and even offered dowries for the women is an uncommon act. It’s also weird enough, I suspect it’s not invention and points to an unexpected concern for women. We need to look “in the corners” of accounts about other matters, where clemency isn’t the point, to discover how atypical Alexander actually was.

So yes, he was (a little) ahead of his time. But I doubt he gave much thought to the plight of women in cities such as Thebes or Tyre or Persepolis, other than passing pity. Their fate was, to his mind, the fault of their male family members who chose to rebel against him—and a warning to others against resistance. There’s no point to the carrot without the threat of a whip, in ancient thought.

I don't know of any specific articles about this topic, although it's an interesting one. There are numerous articles about ATG and women more generally, many by Carney, Müller, D'Agostini, and (earlier) Greenwalt. But aside from an article by Müller on ATG's chivalry in the various medieval romances, I don't think anybody has directly examined the stories in earlier sources. Or, I take that back, Beth Carney wrote an article about women and warfare for the new Brill's Companion to the Campaigns of Philip II and Alexander the Great, and Sabine Müller wrote on war crimes more broadly, but I've not had time to read either chapter yet. The book literally just came out at the tail-end of last year. I bet they have some good bibliography to them.

#asks#Alexander the Great#clemency in Alexander histories#Alexander the Great's chivalry#ancient women#ancient women and warfare.

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you written at all about Queen Cleophis? Love your blog

The Legend of Queen Cleophis

The story of Cleophis (Kripa) fits into a particular trope of “clement Alexander” that we find in the vulgate biographies. When suitably high-born rulers admit defeat and sue for pardon, he graciously gives it. Porus would be another example. The story additionally fits the trope of ATG showing compassion to high-born women. Examples range from Timoklea of Thebes, to Ada of Caria, to the royal women of Darius.

So how likely is it?

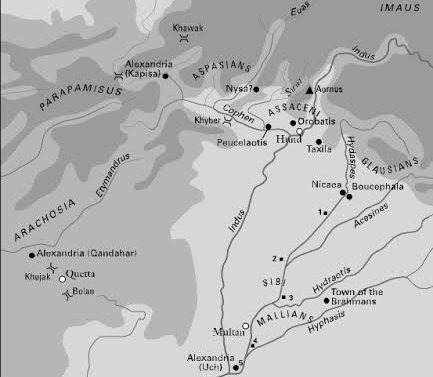

Alexander faced tough resistance in the east from what’s today Pakistan down into SW India. Although Persia had sometimes controlled those areas, it was always loose, and most had broken away, considering themselves independent kingdoms. They wanted no overlord. The area called Aśvaka (Assacani) was among them. Apparently known for breeding warhorses, they were fairly militarily minded and resisted with a sizeable (for the region) army. They even managed to wound Alexander himself. This is the region of the famous Aornos Rock adventure, where ATG had to best Herakles—before he gets to Taxila.

Yet like Porus against Alexander later, they just didn’t have the numbers. So, despite utilizing some good defensive fortresses, the Macedonians had the upper hand, and Alexander eventually killed their (young?) king, Assacanus. His mother, Cleophis, stepped in to lead the resistance. Diodoros tells us (with predictable Greek astonishment) that even the women took up arms to fight(!)—but he doesn’t mention Cleophis.

According to the Roman authors, Curtius and Justin, and the Metz Epitome, Cleophis finally decided they just couldn’t win and surrendered. Alexander supposedly received this courteously and gave her back her kingdom. According to Curtius, this owed to her beauty and charm, but the ever-lurid Justin says she slept with him for it. In any case, even Curtius agrees she later gave birth to a son she named Alexander. The Metz Epitome doesn’t mention a baby.

So, here are our four vulgate authors: Diodoros, Curtius, Justin, Metz Epitome. Of these, all mention the campaign. Diodoros doesn’t mention Cleophis but the other three do. The Metz Epitome names her, but mentions nothing of an affair or child. Curtius mentions a child named after Alexander, but denies the affair. Justin makes ATG the father of the baby. So you can kinda see how the legend grew.

Along with a number of other historians, I’m inclined to view Cleophis as a bit of (Roman) historical fiction. Let’s look at what really happened (insofar as we can guess).

After his time in Baktria, ATG was done, and began to utilize ever-more harsh punishments in an effort to deter rebellion. Unsurprisingly, it had the opposite effect. Alexander’s campaigns in India (which includes what we call Pakistan) were brutal. Returning to Dodoros, who described the campaign, when the Assacanians did finally surrender under oaths, Alexander had the men surrounded and butchered. At their protest that he was breaking sacred oaths, he said he’d only promised them a safe exit from the city, not that he’d leave them alone after. It’s during this butchery that Diodoros describes the bravery of the women. ATG did let the (surviving) women and non-combatants live, but killed everyone of fighting age. It’s a stark contrast to how he’d operated earlier, where surrendering populations were well treated.

Yet that had been before he beat Darius at Gaugamela, or shortly after. Offering great terms for surrender got people on his side. Once he’s King of Asia, he sees these as “his” people, so it’s insurgency. Of course they don’t see it that way, but it’s why he changed tactics. (There were some exceptions in India, but overall, it was a very bloody march down the river.)

Given the ruthlessness of what Diodoros and Curtius (and Justin and the Metz Epitome) tell us occurred, the notion that Cleophis either invited an affair with ATG or later named a son (his or not) in his honor? I find that absurd. If she existed at all, it’s much more likely Alexander gave her back her kingdom because he’d killed everyone who could fight, and she was just a woman. He didn’t see her as a threat.

Did Roman authors, or Kleitarchos earlier, use a shadowy figure to create another “clement Alexander takes pity on a beautiful high-born woman” story? This is, btw, why I spelled her name in Latin fashion: I think she’s a Roman invention. Or at least, the vast bulk of her story is. I’m of mixed mind as to whether she’ll show up in my novels when I get to India. Certainly she won’t in the way she does for Curtius and Justin, but having a name/face to put on resistance is useful. If I do write about her, she’ll be Kripa, not Cleophis.

#Alexander the Great#Alexander the Great in India#Cleophis#Kripa#Alexander and women trope#Alexander vulgate#clement Alexander trope#asks#Classics#ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes