#allegory of intelligence

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

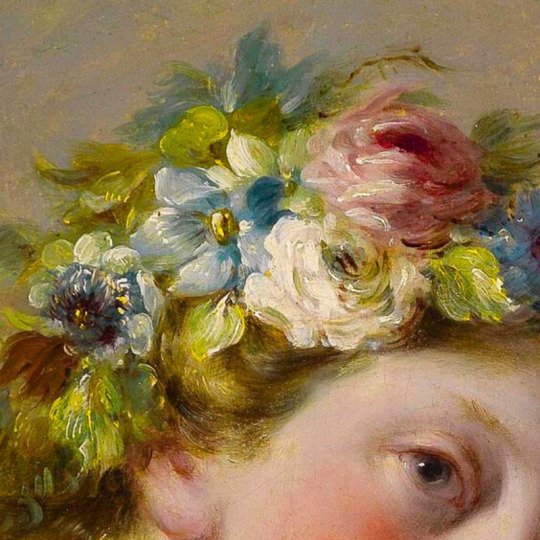

An Allegory of Intelligence

Artist: Caesar Dandini (Italian, 1596–1657)

Date: ca. 1656

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Private Collection

#allegorical art#allegory of intelligence#artwork#oil on canvas#female figure#open book#globe#compass#books#column#snake#table#yellow gown#red cloak#fine art#painting#oil painting#italian culture#italian art#caesar dandini#italian painter#european art#17th century painting#flowers#flower wreath

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

flower crowns + art

#young girl with a flower garland by unknown#flora by rembrandt#ophelia by beatrice offor#flora by pietro dandini#flora by antonio franchi#allegorie des sommers by giuseppe nogari#saint cecilia by onorio marinari#portrait of a youth crowned with flowers by giovanni antonio boltraffio#a saxon princess by emma sandys#i cant find who made this#a portrait of a woman by marie genevieve bouliard#an allegory of intelligence by cesare dandini#cant find the artist#perdita by frederick sandys#fanciulla con lilla by achille beltrame#girl guesses on camomile by charles landelle#the shepherdess by edward fredrick brewtnall#a nymph by blance paymal-amouroux#la belle dame sands merci by john william waterhouse#a girl wearing a garland of wild roses by george lawrence bulleid#saint cecilia of rome by francois-joseph navez#girl with a bouquet of daisies by jules-cyrille cave#saint rose of lima by jose del pozo#poynter by john edward barine#mother and child by eduard veith#pleasure by anton raphael mengs#auguste of baden-baden by alexis simon belle#grand duchess elena pavovna of russia by vladimir borovikovsky#aurora and cephalus by pierre-narcisse guerin#lesbia and her sparrow by sir edward john poynter

604 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Matrix (1999, Andy and Larry Wachowski)

07/11/2024

#the matrix#Science fiction film#1999#Cyberpunk#the wachowskis#academy awards#National Film Registry#library of congress#united states#hacker#morpheus#Hovercraft#3rd millennium#artificial intelligence#ai takeover#Centro della Terra#antivirus software#oracle#clairvoyance#Electromagnetic pulse#ghost in the shell#allegory of the cave#Plato#Evil demon#rené descartes#thought experiment#Brain in a vat#Hilary Putnam#brandon lee#tom cruise

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

rewatched atsv yet again a bit ago and having so many pd thoughts.sighs

#vixen rambles#WAS TALKING W CLAV ABOUT THE AU I WAS THINKING OF MAKING A FEW MONTHS BACK#and like. the thing is that ashe will or dakota could fit into miles’ role (wiwi especially because of his intelligence and observation-#skills. he’s really smart). BUT because this is entirely from my brain and unforch i am the number 1 dakota cole brainrotter .#i think that dakota would really fit in2 miles’ place; and tide as his father.#ESP cause of the commentary 2 be given on if capes existed in an au like that or not. and if tide was a hero chasing after a vigilante like-#dakota yknow. AND !!! i think that doug could rlly be like aaron. t b h .#and idk. ashe as gwen because of the strained relationship with father + everlasting guilt complex + color palette + trans allegory ☝️#here’s how spider demonkicks can still win !#(granted mark also strongly reminds me of miguel ? but also not tbh? it’s complicated. BUT mark and tide as miguel and his wife…. ouagh)#and sammy said will could kind of be like spider noir. cause they r both detectives and both have the color palette#but wiwi does NOT have his swag </3. but whatever my aus never closely follow their inspo ☝️#and tbh vyncent would definitely be like. omg what’s her name…#PENNY i think. the girl who’s best friends w her spider and made a little mech suit for it. i think playing w that could kind of -#incorporate the greats yknow? like maybe theyre other spiders somehow bound to vyncent and he’s one of the original anomalies as well.#yknow ?????

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have the same attitude towards ai use that i have towards drug abuse. for a few months last year i would use ai to illustrate my ocs, until i forced myself to stop. whenever i feel the urge to make more or find the images i deleted i treat it like withdrawal and either bother my friend who can actually draw or i bury myself in crack fics.

#some irony in using crack fics to avoid something im using as a drug allegory#ai art#ai#fuck ai#anti ai#artificial intelligence#cecenyss#disclaimer ive never been addicted to actual drugs

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

istg as a mf from an incredibly repressed generic-ish family that needs wild amounts of therapy, i think what's happening in this movie might genuinely be a better outlet for marital and familial frustrations than what i grew up with

#like hiding your profession (assasin) as an allegory for repression?????#shit goes crazy#mr and mrs smith (2005)#this could apply to so many other things though tbf#ill probably think of them later#and this isnt even abt the incredibly gendered portrayals of the characters which i do believe is intentional#how could it not be???? but maybe thems my 2024 lenses talking#and the portrayals vs the characters agency/intelligence in using their gendered expectations as cover????? love#movies

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ai artwork#ai art#ai generated#ai image#ai girl#artificial intelligence#chatgpt#taylor swift#technology#nightshade#winter soldier#tf2 soldier#soldier boy#small soldiers#chained soldier#oil#available#exhibition#allegory#impressionism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

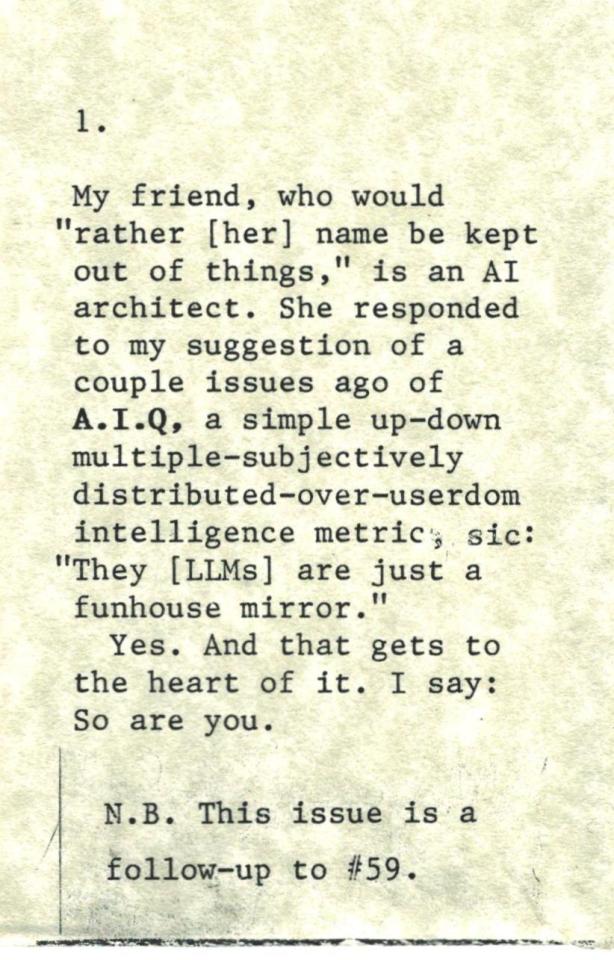

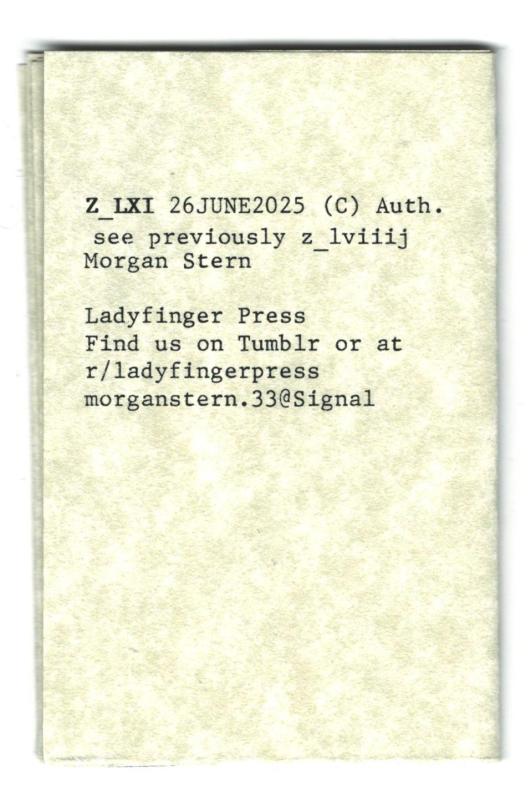

z_LXI · The Magical Horrible Funhouse Mirror that Made Everybody Horny

https://archive.org/details/z_lxi

#philosophy#speculative fiction#allegory#relationships#mortality#horror#alignment#consciousness#funhouse#mirror#lookingglass#sycophancy#love#identity#flash fiction#intelligence#ladyfinger press

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Inhumanity of AI

Reflections on Values, Meaning, Logic and Technology Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a raw analytical capability — the power to perform analytical operations with immense speed and precision. However, artificial intelligence does not have the capacity to make qualitative value judgments or assessments, or to understand meaning. These capabilities, I would argue, are the fundamental features of…

#aesthetics#AGI#AI#allegory#analysis#analytics#Artificial Intelligence#computers#consciousness#culture#education#enlightenment#GIGO#ideas#intuition#language#left brain#linguistic analysis#logic#Logos#meaining#meaning#mechanics of reading#my-featured-post#perception#perspective#philosophy#pineal gland#right brain#semantics

0 notes

Text

One of my all time biggest pet peeves with historical(ish) fantasy is when the writer constructs a religion with a clear bias that it's stupid and false and therefore only the Stupid People and/or commoners believe in it and all the smart/elite main characters are like, quasi-atheists or otherwise just routinely flout established religious conventions of orthodoxy and/or orthopraxy because they're Too Smart for it or etc.

It's usually an extension of assumptions that people in the past were just less intelligent than in the contemporary, just being like "I know that the sun is a star millions of miles away that the earth orbits, but this ancient religion describes it as a chariot flying through the sky" and not really bothering to learn the context and just (consciously or subconsciously) settling on 'that's a crazy thing to think and was probably believed in because they were Stupid'.

And that whole attitude pisses me off so much. People were as 'smart' 10,000 years ago as they are today. These beliefs aren't just desperate, random flailing to explain phenomena that could not directly be accounted for either, it's not like people just looked at the sun and went "Uhhh I don't know what the fuck that thing is, actually. I guess it might be a chariot or a boat or something?? Yeah let's go with that." and based entire religious practices on this. Every well-established belief system exists within broader contexts of cultural values/subjective perceptions of reality/knowledge systems/etc, and exist as part of a historical continuum of religious practices that came before. Even when not Materially Correct, they have context and internal logic, they're not always dead literal with zero levels of allegory, and they're never a result of stupidity.

#I think you're failing at good worldbuilding and also just like. Idk failing at being an understanding human being willing to learn about#people different from yourself when you approach writing religion from a 'uhhhh what's some random stupid shit people believed in#2000 years ago' angle#Like make an effort to understand the logic and worldviews and value systems that informed these practices before you synthesize your own

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Another reminder that Greek mythology is always somehow symbolic, metaphorical, allegorical, since we are dealing with anthropomorphic personifications and other embodiments of cosmic powers.

For example: Demeter has sex with both Zeus and Poseidon. Something-something about the relationship of the Earth with the Sky and the Sea (or the celestial and chthonian powers). ESPECIALLY since these relationships are said to happen at the beginning of the world, in the primordial times during which the world settled itself for what it is now.

Herakles' wedding with Hebe, the personification of youth, checks in with when he becomes an immortal god (aka, an eternally young entity). What better way to symbolize a hero escaping the clutches of death than by him becoming the husband of the spirit of eternal youth?

Why is Hestia never leaving Olympus? Something-something about her being the literal personification of the hearth, which is at the center of the house/community and does not move.

Why is Ares getting his ass kicked by Athena? Because Athena is civilization, and Ares savagery, and in the Ancient Greek mindset intelligence, wisdom and craft will always be above brutality, bloodlust and random cruelty.

Do I need to spell it out that the myth of Persephone-Hades-Demeter is about the cycle of the seasons, and how the earth renews itself and brings back life after a time of death?

And I wonder why Ares' companions during his mass-slaughters are called Phobos, Deimos and Eris - Fear, Panic and Discord... Why would the goddess that breaks harmony and sows feuds and chaos be depicted as the close sister of the god of the ravages of war and of the brutality of conflicts, what a strange mystery!

And I can go on, and on, and on. Remember, the Greek gods aren't just super-heroes or wizards (that's more in line with more "humanized" mythologies, like the Irish or Nordic ones). They are embodiments of concepts and ideas, personifications of natural forces and cosmic powers, they are living allegories and fleshed metaphors. Zeus wields the lightning because he IS the lightning and thunder. Dionysos is both the bringer of joy and madness because he IS alcohol. Hades is both the name of the god of the dead, and of the realm of the dead. Hestia's name is literaly "hearth" in Greek, Hebe "youth", Nyx "night", Gaia "earth", Eros "desire". You can write "Eris met Helios at Okeanos' palace" or you can write "Strife encountered the Sun at the palace of Ocean" and that is the EXACT SAME THING!

[Mind you to limit the gods to being JUST allegories is also a mistake not to make. Greek deities are much more than just X concept or X idea... But one part of the myths will always be, down the line, some weather metaphor or some natural cycle motif]

#greek mythology#greek gods#this is also for almost all other mythologies in the world#but we'll stick with greek for now#greek goddesses#greek myths

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry if this has been asked before, but are there any pieces of media that have shaped your conception of angels?

a formative one for me was his dark materials, when it described angels as only appearing in the form of winged humanoids because it was what was expected of them, and claimed that their true forms actually resembled architecture/"huge structures composed of intelligence and feeling" - i could never hope to draw the mental images that gave me, but it influenced my comparisons of pylon towers to angels, which are the closest reference i can give to the towering skeletal chain-like structures of light and matter that i imagined angels to be. it was also what first made me question the nature of angels, and begin to see them as something other than simply people with wings and halos who sang and/or fought for god - though i do have a weakness for angels imitating humanity, desiring and envying their free will and the unscripted lives it grants them, and in doing so becoming a little more human and a little less divine themselves, and falling in a metaphorical rather than literal, physical sense (which, to an angel, being an entity made of pure symbolism, is essentially the same thing, and can kill them just as surely as a sword).

kill six billion demons' angels are very inspirational to me; their naming system based on which reincarnation of itself the angel is makes me clap my hands with delight - particularly 6 juggernaut star, whose name belies how long she has endured through endless cycles, unable to break the wheel herself, and become entrenched in her own despair-driven futile rage as a result. and of course i'm a huge fan of 82 white chain's character arc involving an allegory for transition (specifically coming out as transfem) that also actually culminates in her transitioning (again, the symbolic and the literal go hand in hand with angels).

theres also this YA book called 'angel' by cliff mcnish that i read when i was like. eight? nine? i remember very little of it, and don't think it would hold up at all if i reread it now, but i do recall that one of the guardian angels in it died while saving one of their wards in a car wreck. the idea of angels as something that can be hurt and destroyed, that could be created to suffer and die, that could feel pain and experience grief, and potentially be imbued with supressed self-preservation instincts to serve their purpose, really flipped a switch in my brain.

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On vampires, they are the most powerful metaphor for the outsider I ever encountered. I, a woman with no clear gender identity, strong erotic drives, great ambition, and a fractured cultural background, felt "normal" when I wrote about vampires --- intelligent outcasts who refused to accept the world's contempt as their story. I didn't inject philosophy into my vampire novels; it was just there; Lestat, Louis, Claudia, Armand...they were living breathing allegories, all crying for the right to live, to have a place in the universe. If you give all you have to your writing, if you tell all you know in every novel, you can't escape the deeper philosophical questions, meanings, possibilities. When I came of age, nobody thought "a vampire novel" was worth that kind of commitment and depth. Genre fiction was presumed to be shallow. Same with the historical novel. I saw "Feast of All Saints" panned because it wasn't a simplistic melodrama. Nobody even knew how to classify "Cry to Heaven." But I kept giving all I had to my strange books, ignoring the denigrating labels and frankly getting downright angry about them. Today, you don't hear those complaints so much. Seems the whole world knows you can learn a great deal about "everything" from a good episode of "Game of Thrones" and that there are profound truths in "Gone Girl." Daniel Silva packs his beautiful spy novels with deep moral concerns. Any type of novel can be a great novel. — What a wonderful thing to have lived long enough to see the power of labels broken, the "rules" of genre thrown to the winds, the bias of high culture ignored or stood on its head. Of course the science fiction readers always knew these truths. In the 50's they were looking to their great writers for poetry, heart wrenching reflection on alienation — the use of plot and setting for lofty and undeniable truths. I love being a novelist. — I love being the producer, director, set designer and star of my weird, unclassifiable stories. I've grown to love being laughed at, sneered at, ridiculed, questioned as to how I, of all people, dare to write about Jesus! And you know why I love it? Because I've been lucky enough to have many, many readers over the years, readers who give each new book a chance, readers who say simply that they enjoy my books, readers who quietly "get it," wonderful readers from all walks of life --- They are priceless to me, and they are my real critics, reviewers, judges, etc. I long ago left it up to them to decide whether I was any good, or just a crackpot or a trash writer. And I just go on writing about vampires, witches, telepaths, ghosts, angels, werewolves, and yes, even Jesus — for them and for me."

Anne Rice from her Facebook Page

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, project 2025 has been deleting their PDFs but a few lovely people have posted the list of books they want to ban and other than the fact that the entire list is stupid, here's some that stuck out to me + the reasons listed next to them. Most of the books on the list are lgbtq+ books which one would expect to find there, so I just did ones I didn't expect.

The Holy Bible - Challenged for religious beliefs and graphic content.

A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin - Sexual violence, political intrigue.

Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson - Death and religious content.

Captain Underpants series by Dav Pilkey - Toilet humor and "disobedience."

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak - Critique of the Russian Revolution.

Deadly Deceits by Ralph McGehee - Former CIA agent's critiques of the agency.

Emma by Jane Austen - Complex gender themes, social critique.

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury - Censorship and media manipulation by the government.

Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling - Accusations of promoting witchcraft.

Howl by Allen Ginsberg - Explicit sexual content, anti-establishment themes

Hop on Pop by Dr. Seuss - Concerns over violence against parents.

I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika L. Sánchez - Mental health, sexual content.

It's Perfectly Normal by Robie H. Harris - Sex education content.

It's So Amazing! by Robie H. Harris - Sex education content.

None Dare Call It Conspiracy by Gary Allen - Discusses alleged hidden global power structure.

None Dare Call It Treason by John A. Stormer - Anti-communist and conspiracy-focused.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - Critique of Soviet labor camps.

Operation Paperclip by Annie Jacobsen - Exposes secret U.S. program involving former Nazis.

My Brother Sam Is Dead by James Lincoln Collier - Violence, anti-war themes.

Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt vonnegut- Anti-war themes.

Spycatcher by Peter Wright - Ex-MI5 agent's account of intelligence operations.

The Art of Happiness by the Dalai Lama - Criticism of religion, perceived political messages.

The Awakening by Kate Chopin - Female independence, sexuality.

The Book of Night Women by Marlon James - Slavery, graphic violence.

The Enchanted Forest Chronicles by Patricia C. Wrede - Magic, feminism.

The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein - Themes of selfishness, parenting.

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy - Examines class and caste issues in India.

The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood - Critique of religious extremism and patriarchy.

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas - Examines police violence and racial injustice

The Hunger Games Series by Suzanne Collins - Depicts oppressive government and rebellion.

The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster - Political subtext, wordplay.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver - Critique of colonialism and missionary work.

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene - Critique of religion and political oppression

The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle - Religious critique.

The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli - Seen as a critique of political ethics.

The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare - Often challenged for themes of submission of women in marriage.

Twilight series by Stephenie Meyer - Themes of violence, supernatural elements.

V for Vendetta by Alan Moore - Political rebellion, violence.

War is a Racket by Smedley D. Butler - Critique of war profiteering.

Where the Sidewalk Ends by Shel Silverstein - Dark humor, "rebellious" themes.

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak - Themes of rebellion, dark imagery.

Where's Waldo? by Martin Handford - Alleged inappropriate illustrations.

White Noise by Don DeLillo - Critique of consumerism and modern society.

Women Who Run with the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes - Feminist themes.

Yertle the Turtle by Dr. Seuss - Seen as political allegory.

Zorba the Greek by Nikos Kazantzakis - Critique of authority and societal norms.

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

I return from BARBIE and I will say that my only true critique is that it is a film much more interested in using Barbie as an allegory for WOMEN as a monolith than it is in exploring femininity and what Barbie means to people who find freedom within that but it's fine

as thoughtful and insightful as I think Gerwig's work can be, I think it very much all comes from a cis heterosexual perspective, femininity is praised and critiqued but also inextricably tied to womanhood, just not in a way thats necessarily revolutionary, womanhood isn't a collection of somewhat arbitrary traits that sometimes come bundled together in a stereotypical package, but something that's always recognizable and familiar and filled with universal experiences

that said, I still think it's a valuable and intelligent look into the struggles of women who do their best to fit the mold they've been given only to realize being a human who's complicated and imperfect makes that task impossible

despite these "issues" I think women of all types and walks of life will find something to connect to in some way, I just don't think it's particularly ready to explore things like Barbie and her connection to homosexual culture, or transness as a broad concept, or the fact that not all women worry about the opinions and expectations of men

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Myth, Muse, and Mourning in the Figure of Émilie Agreste: A Study of Her Portrayals in My Work

This contains spoilers for three of my stories: House of Agreste, Flightless Birds, and Smalltown Boy.

Before Émilie Agreste was a mother, a muse, or a dead woman, she was a myth. Or rather, she became one. In canon, she exists as a doll in a pod, a photograph on the wall, little video diaries saved into Nathalie’s phone, a rose-tinted memory etched onto Adrien’s longing, and stories told through notorious unreliable narrator Gabriel Agreste. She’s a beautiful absence, made notable by how little she is allowed to be.

In my stories, namely House of Agreste, Flightless Birds, and the second half of Smalltown Boy, Émilie steps out of the shadows and into her own body. She speaks, smokes, flirts, argues, grieves, and easily spins entire worlds around her. Still, no matter how vivid she becomes, her tragedy lingers. Like the women whose legacies have shaped her at various points in my stories, Adele Bloch-Bauer, Sharon Tate, Marie Antoinette, and Courtney Love, Émilie is at once an icon and individual, muse and martyr, beauty and ruin. No matter where, when, or how, Émilie’s image is never formed in a vacuum.

These women share little in biography, but much in aesthetic myth. They are looked at more than they are heard and they become symbols of everything society projects onto femininity: adoration, jealousy, control, desire, blame. Each of them, in different ways, informs the Émilies I’ve built not as a one-to-one allegory but as facets in a broken mirror. Through them, Émilie becomes a portrait, a ghost, a queen, and a calamity.

All the things we want from beautiful women, and all the ways we destroy them for it.

I. The Portrait: Émilie as Adele Bloch-Bauer

To be painted is to be preserved, but not to live.

Adele Bloch-Bauer was a Jewish Viennese socialite and patron of the arts in the early 20th century, known for her intelligence, elegance, and sharp political mind. She was painted twice by Gustav Klimt, most famously in Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, a masterpiece of gold leaf and patterning and a visual symbol in Miraculous throughout Seasons 1 to 5, as well as a haunting constant in House of Agreste. In the real world, the painting, later stolen by the Nazis and eventually returned to her family, became a symbol of her beauty and of a stolen legacy.

But in the portrait itself, naturally, Adele is unvoiced. Obviously, it’s a portrait. She’s stylized into ornament, a woman flattened into iconography, and her expression is completely unreadable beneath layers of abstraction. The real Adele disappears beneath Klimt’s devotion. She becomes mythic. Untouchable.

“I want it. How much could it be? I’ve yet to find a work of art I couldn’t afford.” “It’s one of the most famous paintings in the world, Émilie. It’s priceless. And I don’t think it’d be fair to her niece.” “Then I want to be her.” Nathalie looked intrigued. “Her life was tragic. There really isn’t much to envy.” “No, you don’t understand,” she said as she took a few steps back, framing the painting from afar with her hands. “I want to be her. I want you to find me an artist I could commission to recreate it, in the exact style of Klimt. But I would be Adele Bloch-Bauer,” she turned to her then with a million-dollar smile. “You’d do this for me, wouldn’t you?” “I’ll… see what I can do.”

House of Agreste — Chapter 3

Émilie inhabits a similar contradiction in House of Agreste. She is the face of Gabriel’s fashion empire, the namesake of his most celebrated dress, “The Émilie Dress,” which is reworked and paraded through every season like a ritual. She’s the woman behind the muse, but eventually, the muse overtakes the woman. Gabriel curates, rather than loves her. He dresses her like his very own Barbie Doll, displays her, claims her as his ultimate source of inspiration and creation in an interview with a British Vogue journalist. He elevates her into a symbol of his genius and her identity consequently becomes molded into fabric and sewn into silhouette.

And yet, Émilie is no passive canvas. In my retelling, she participates in the mythmaking. She advises Gabriel on what women love and want, quotes Style Queen reviews back to him, lets herself be idealized and sometimes sharpens the illusion herself. She knows she is part of the exhibit. That her beauty, her body, her name are all on display.

But a portrait does not age. A portrait does not weep, or argue, or change. A portrait does not fight back. And when Émilie disappears, Gabriel clings harder to the version of her he can control; namely the ghost in the painting. The muse who never says no.

The gold leaf, after all, never tarnishes.

II. The Beautiful Victim: Émilie as Sharon Tate

As sad as it sounds, Sharon Tate’s death is what made her famous. Not her films, not her voice, not her love.

Sharon Tate has become less a woman than a genre: the innocent American starlet, framed in perfect 1960s light, forever paused just before catastrophe. What holds the public’s fascination is her death, her beauty, her body, pregnant and doomed. She was lovely, and she was loved, and she was murdered, and the tragedy is made more palatable because she was photogenic.

“First of all,” she began, gently lifting Nathalie’s index finger as if to keep count. “You know how my agent called the other day? I was cast to play Sharon Tate in a comedy-drama about Hollywood’s golden age.” “That’s great,” she said, racking her brain to remember exactly who was Sharon Tate. “It’s a big role.” “It is. I’ve looked up to her for as long as I can remember. I’ve always said, if it wasn’t for Gabriel, I’d be living it up in LA, a house on the hills, partying every night. I can do a mean American accent, you want to hear it? “Um...” "We can run some lines together later. I can’t wait to play her, even though I’m not exactly chuffed by the thought of playing wife to Roman Polanski, but we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.”

House of Agreste — Chapter 3

For context, in House of Agreste, before her miscarriage, Émilie was cast in a fictionalized version of Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Naturally, Émilie was thrilled. She idolized her! She wanted to wear the go-go boots and the eyeliner, to swirl around in sun-drenched California light and leave audiences breathless. For a brief moment, it felt like a tribute to the actress she loved so much.

Émilie, in this story, is somewhere between a B-list and A-list actress, so, famous enough to be recognized, photographed, whispered about. She isn't a nobody dreaming of fame; she’s there, or nearly there.

She knows what it's like to be a woman turned public property. To have people comment on her waistline in magazines, to be celebrated when she smiles and ripped apart when she doesn’t. Sharon Tate represented a kind of performance Émilie once aspired to; beauty without bitterness, attention without the sting. Sharon was a woman adored for being, not doing. She floated rather than clawed. That was what Émilie admired: the ease, the myth of being wanted without having to fight for it.

But then Émilie had the miscarriage.

And suddenly, she could not play a woman eight months pregnant who would be murdered onscreen for aesthetic purposes.

(Nota bene, and SPOILER alert for the real movie: in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Sharon Tate's character is famously not murdered. Tarantino rewrites history, saving her in a fantasy of retroactive justice but even in that revision, she is more symbol than subject. She’s spared, but not centered. The myth remains intact.)

That moment reframes everything. Émilie ceases to participate in the myth and becomes a critic of it, recognizes how beauty becomes a curse, how pregnancy becomes spectacle, how violence against women is endlessly reenacted for art and entertainment and catharsis. She now knows what it means to be adored until you bleed, and rejects the commodification of her own grief by refusing to let her body be a prop. This refusal, though, does not save her. Her trajectory, like Sharon’s, still leads to disappearance, to martyrdom, to myth.

She was beloved, and when she was gone, her image lingered longer than her voice ever did.

III. Let Them Wear Couture: Émilie as Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette, frivolous queen of aesthetic excess, became the face of a revolution for what she represented. She was punished not because she was a tyrant, but for spending too much, dressing too extravagantly, smiling too prettily in a time of collapse.

“I would love to play Marie-Antoinette in a movie. I just… I get her.” Nathalie smiled, meeting her eyes. “I get the feeling you’d make a very convincing Marie-Antoinette.” “And I’ll take it as a compliment… Shall we go this way then?”

House of Agreste — Chapter 3

In House of Agreste, Émilie is the queen of the house. She climbs the fashion ladder beside Gabriel as a business partner. She is the one who speaks to investors, who knows when to flatter and when to threaten.

What Marie Antoinette also was, though, was a queen who liked to play peasants. She escaped the constraints of Versailles by retreating to the Petit Trianon, where she dressed in linen chemises, milked cows for fun, and entertained fantasies of simplicity all while the country starved outside her fake little sanctuary. She was therefore also hated for the performance of humility, for making poverty look picturesque.

In Smalltown Boy, despite being literal royalty, Émilie cosplays a broke girl, and Gabriel (Gabi, at the time), takes notice immediately.

“I don’t hate it,” she says, dreamily. “This place. It’s got that bohemian charm you hear about in the Aznavour songs. Artists scraping by on passion and cheap wine… Not glamorous, but… we’re free. I could tell you a great deal about freedom. And how important it is to me.” A small part of Gabi wants to point out that this studio is a romantic concept mostly for someone who grew up with more bathrooms than family members. Émilie is like a modern-day Marie Antoinette when she built her little farm at Versailles and wore peasant “shepherdess” dresses for fun, accidentally launching an entire trend in 1700s high-society court fashion. He’s seen the glint of real silverware in the few boxes Émilie brought along, the embossed stationery with her family crest. It’s a constant reminder that if she fails, she can always go back to velvet drapes and fine china. If he fails, it’s back to… well, nothing.

Smalltown Boy — Chapter 2

Smalltown Boy was only written once I felt I could finally see the bigger picture. Representation, Revelation, and Werepapas gave me the missing puzzle pieces that I had been looking for since I started watching Miraculous. House of Agreste's Émilie came first, a product of my imagination based on little clues in the show, then Flightless Birds', which was an educated guess based on the information given by Félix and Kagami's play.

The new context we were offered recently has given birth to yet another depiction of Émilie’s character in my story.

She smokes secondhand cigarettes in her husband's crumbling flat, dresses like a waifish art student, flirts with other people’s trauma like it’s an aesthetic. It’s not that she lacks intelligence, far from it. But her detachment is a luxury and she knows it.

Gabriel, in contrast, grew up in the kind of house that smelled like fryer grease and unpaid bills. He didn’t pretend to be poor, he was. He worked shifts, and stared down the inevitability of staying small unless he carved out a future with his own hands. Their class difference is the unspoken language between them, one she occasionally romanticizes and he occasionally resents.

When they meet, she treats his reality like a costume party.

What a lovely place! she’d exclaimed, twirling around the dead streets and sampling a single fry from the family-owned friterie. How quaint and charming!

Smalltown Boy — Chapter 2

She thinks of post offices and rusted fences as aesthetic, calls their attic of an apartment bohemian and wants to live in a Godard film where nobody eats but everyone is beautiful.

As a side note, and speaking of Godard, Émilie’s relationship with performance, beauty, and the aestheticization of suffering is yet again depicted in Flightless Birds. In the story, Émilie plays Nana in the movie Solitude, a fictional version of Vivre sa Vie [1962], and channels the same fragile beauty and performative despair that defined Anna Karina’s character. Like Nana, Émilie turns her suffering into spectacle. It allows her to rehearse tragedy, to play at ruin, to live out existential collapse onstage without having to truly endure it.

In conclusion, like Marie Antoinette, Émilie doesn’t mean to offend. She’s not malicious, she’s curious, and doesn’t see how her presence distorts the room. How her poverty is always a phase, a mood, a role she can exit at any time.

IV. Disaster Icon: Émilie as Courtney Love

Where the previous icons I’ve named were silenced by death, Courtney Love has survived by being loud, brash, feral, loving, grieving, and resisting the saint-or-sinner binary forced onto widows and mothers. She is accused, exalted, and ridiculed in equal measure.

Audrey caught the girl giving her a nasty glare. “Oh, relax, Courtney Love, I won’t steal him from you,” she cackled, stepping closer. “Heard of you, Émilie G.”

Flightless Birds — Chapter 4 (The Brooch)

When Audrey Bourgeois first meets Émilie in Flightless Birds after praising Gabi for his incredibly promising first collection at Fashion Week, she narrows her eyes, sizes Émilie up, and calls her, “Courtney Love.” It’s not a compliment.

She mainly says it because of Émilie’s grunge look in that scene, some kind of jab at it, but there are layers and implications that come with the name.

The name makes you think of fishnets, smeared lipstick, tabloid carnage. Courtney Love is a litmus test for everything people love and loathe about women. Was she the witch or the widow, the muse or the murderer, the parasite or the prophet?

So when Audrey calls Émilie “Courtney Love,” what she means is too loud, too emotional, too ambitious, too sexual, too much. Basically, a woman who refuses to fade politely into the background of her famous man’s spotlight.

And Audrey’s not wrong.

In Flightless Birds, Émilie has not yet become a muse as she is still fighting for control after escaping from an arranged marriage that would have ruined her, and is trying to make something of herself. She’s messy, sharp, magnetic, and much like Courtney, Émilie falls in love with a man who is actively breaking. Gabriel, like Kurt Cobain, is an artist with a soft-spoken center and a gaping wound where emotional intimacy should live.

There was a pause, and then he replied. “(... ) You’re what’s keeping me sane.” (...) “I don’t want you to be sane.”

House of Agreste — Chapter 1

“Of course he is,” Émilie replied, positively glowing. She crossed her arms and leaned against the doorframe, watching him like an artist’s muse observing the creation of her own portrait. “He’s fretting. You see that? The pacing, the refusal to rest… classic artiste behavior. It’s thrilling. Passion like that, it’s… intoxicating. Nothing good ever comes out of a sound, undisturbed mind.”

House of Agreste — Chapter 1

Courtney Love was often vilified as manipulative, some kind of “Yoko Ono figure” blamed for Kurt Cobain’s self-destruction, as if women exist only to corrupt or save genius. In reality, theirs was a mutually destructive bond: two artists enabling each other’s addictions. Émilie and Gabriel mirror this dynamic closely, particularly in House of Agreste. She feeds his insanity, knows when he’s unraveling and leans into it, out of a private thrill. It makes her feel powerful, desired, and indispensable.

What’s interesting is that when I wrote House of Agreste, I hadn’t consciously drawn the parallel to Courtney Love. And yet, the reference surfaces anyway in the scene where Audrey Bourgeois warns Gabriel about Émilie. The myth was already there, waiting to be named.

“You know, Gabriel, I don’t carry Émilie in my heart and never really have. I warned you from the beginning, didn’t I? Told you she was all surface, no substance. Beautiful, yes, but insincere to her very core. And what did you do? You ignored me. Built your entire brand around her. Named collections after her. You practically handed her a pedestal and begged her to stand on it.” “Your point?” “My point,” she said, circling him like a cat with a mouse, “is that she doesn’t love you. She loves what you represent; adoration, power, relevance. That’s all she’s ever cared about.” “All right.” His voice was a knife in velvet. “You’ve made yourself perfectly clear.” “Have I? Because you’re still standing there, pretending she’s the saint you painted her as. I’m not trying to be cruel, Gabriel. I’m trying to save you from yourself. One day, she’s going to leave, and when she does, there won’t be enough left of you to stitch together.”

House of Agreste — Chapter 5

Courtney Love was never forgiven for surviving Kurt. Not because anyone really believed she killed him, but because people wanted to believe she could.

Unlike the popular story of Kurt and Courtney, though, Gabriel lives. And in living, he rewrites everything. He makes Émilie into his excuse, his idol, his martyr, the perfect posthumous love story. What he cannot control in life, he canonizes in loss.

“You owned the 90s and God knows there was some tough competition out there. Do you know what it takes to be able to steal the spotlight from the likes of Chanel, Prada and Versace at that time? You put up a fierce fight this last decade too, and I know you’ve got so much more to give to this world… At the end of the day, you made this happen with your own two hands. She helped, but she didn’t make you, you made your own self. You can do it without her.”

House of Agreste — Chapter 9

When the smoke clears in the end, we remember the geniuses these two women loved. But we never stop talking about the women who were too loud next to them.

V. The Afterlife of Émilie

What links all of these women, Adele, Sharon, Marie Antoinette, Courtney, is the way they persist even when gone, or shunned, or vilified, they remain embedded in culture. As a painting, a headline, a cautionary tale.

Émilie, too, haunts everything. She’s the mother Adrien idolizes. The ghost Gabriel worships. The sister Amélie cannot forgive. Every choice they make is in reaction to her, to the idea of her. In death, she becomes omnipresent.

But perhaps the most chilling thing is that we never get Émilie whole. Not in canon, and not even in fanfiction. Every version of her is a reconstruction, including mine. It’s always a narrative curated by someone else, a story told by those who survived her.

Which is to say: Émilie is a reflection of how we view women and of what we value in their silence, of what we mourn and what we fetishize. She is a beautiful corpse, a golden queen, a dirt-streaked child in the woods, she is a ghost in couture, and like all women who are too looked-at and too loved, she is more myth than memory.

And that is what makes her unforgettable.

82 notes

·

View notes