#are distinctly modern conceptions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fuck it, this fic is definitely getting footnotes and a works cited. It makes no sense for the cast to be technocratic, but I’ve already done too much research to not shut up about how things could work.

#on the dark side of the moon#just because research says how modern people solved issues#does NOT mean the characters will come to the same solutions#and also some unhinged mindsets I have about policy#are distinctly modern conceptions#anyways in completely different news#there’s a hurricane today so time to grab some surveying data#and watch how the roads flood over the next 24 hours

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, breaking my principles hiatus again for another fanfic rant despite my profound frustration w/ Tumblr currently:

I have another post and conversation on DW about this, but while pretty much my entire dash has zero patience with the overtly contemptuous Hot Fanfic Takes, I do pretty often see takes on Fanfiction's Limitations As A Form that are phrased more gently and/or academically but which rely on the same assumptions and make the same mistakes.

IMO even the gentlest, and/or most earnest, and/or most eruditely theorized takes on fanfiction as a form still suffer from one basic problem: the formal argument does not work.

I have never once seen a take on fanfiction as a form that could provide a coherent formal definition of what fanfiction is and what it is not (formal as in "related to its form" not as in "proper" or "stuffy"). Every argument I have ever seen on the strengths/weaknesses of fanfiction as a form vs original fiction relies to some extent on this lack of clarity.

Hence the inevitable "what about Shakespeare/Ovid/Wide Sargasso Sea/modern takes on ancient religious narratives/retold fairy tales/adaptation/expanded universes/etc" responses. The assumptions and assertions about fanfiction as a form in these arguments pretty much always should apply to other things based on the defining formal qualities of fanfic in these arguments ("fanfiction is fundamentally X because it re-purposes pre-existing characters and stories rather than inventing new ones" "fanfiction is fundamentally Y because it's often serialized" etc).

Yet the framing of the argument virtually always makes it clear that the generalizations about fanfic are not being applied to Real Literature. Nor can this argument account for original fics produced within a fandom context such as AO3 that are basically indistinguishable from fanfic in every way apart from lacking a canon source.

At the end of the day, I do not think fanfic is "the way it is" because of any fundamental formal qualities—after all, it shares these qualities with vast swaths of other human literature and art over thousands of years that most people would never consider fanfic. My view is that an argument about fanfic based purely on form must also apply to "non-fanfic" works that share the formal qualities brought up in the argument (these arguments never actually apply their theories to anything other than fanfic, though).

Alternately, the formal argument could provide a definition of fanfic (a formal one, not one based on judgment of merit or morality) that excludes these other kinds of works and genres. In that case, the argument would actually apply only to fanfic (as defined). But I have never seen this happen, either.

So ultimately, I think the whole formal argument about fanfic is unsalvageably flawed in practice.

Realistically, fanfiction is not the way it is because of something fundamentally derived from writing characters/settings etc you didn't originate (or serialization as some new-fangled form, lmao). Fanfiction as a category is an intrinsically modern concept resulting largely from similarly modern concepts of intellectual property and auteurship (legally and culturally) that have been so extremely normalized in many English-language media spaces (at the least) that many people do not realize these concepts are context-dependent and not universal truths.

Fanfic does not look like it does (or exist as a discrete category at all) without specifically modern legal practices (and assumptions about law that may or may not be true, like with many authorial & corporate attempts to use the possibility of legal threats to dictate terms of engagement w/ media to fandom, the Marion Zimmer Bradley myth, etc).

Fanfic does not look like it does without the broader fandom cultures and trends around it. It does not look like it does without the massive popularity of various romance genres and some very popular SF/F. It does not look like it does without any number of other social and cultural forces that are also extremely modern in the grand scheme of things.

The formal argument is just so completely ahistorical and obliviously presentist in its assumptions about art and generally incoherent that, sure, it's nicer when people present it politely, but it's still wrong.

#this is probably my most pretentious fanfiction defense squad post but it's difficult to express in other terms#like. people talking about ao3 house style (not always by name but clearly referring to it) as a result of fanfic as a form#and not the social/cultural effect of ao3 as a fandom space#you don't get ao3 house style without ao3 itself and you don't get ao3 without strikethrough and livejournal etc#and you don't get those without authors and corporations trying to exercise control over fic based on law (often us law) & myths about law#and you don't get those without distinctly modern concepts of intellectual property and copyright#none of those things have fuck all to do with form!#anghraine rants#fanfiction#general fanwank#long post#thinking about this partly because the softer & gentler versions of fanfic discourse keep crossing my dash#and partly because i've written like 30 pages about a playwright i adore who was just not very good at 'original fiction' as we'd define it#both his major works are ... glorified rpf in our context but splendid tragedies in his#and the idea of categorizing /anything/ in that era by originality of conception rather than comedy/tragedy/etc would be buckwild#ivory tower blogging#anghraine's meta

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

one day i will write my thoughts on the nature of Ghosts in Ghostbusters because.., that entire component of the universe is so peculiar and I love it

#olliepost#not really touching on the cartoons or comics particularly but#the mainline content#bc. as far as with most cultures 'ghosts' were previously living being from our world#but gbs contains a huge swathe of non human non earthly spirits that appear to overlap greatly with previously human now dead entities#ie. the manifestation usually warping the ghost into something distinctly divorced from their previous appearance#or allowing them to do so at will like with Eleanor#idk#it's interesting to me i need to yap about it#also. was discussing with sauce (hi) about how. for a film about ghosts..#it's not until the modern films that death as a concept is genuinely touched upon as a theme or motif#i mean. in the first 2 sex is a more coherent and present component#than. dying. in the ghost movie#idk but i love it and how blasé everyone is about it

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

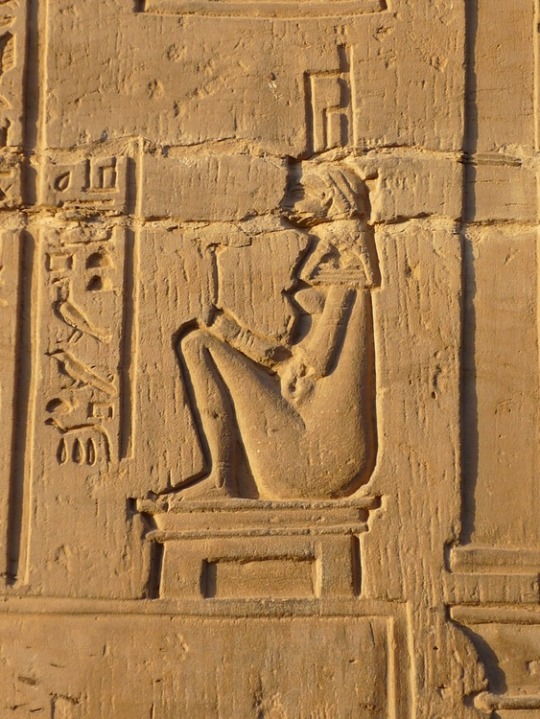

It's weird that we have to explain ourselves and the concept of an "ethnoreligion" to so many people when "ethnoreligions" would practically have been one of the default options for most of human history. Can you imagine going up to an ancient Egyptian administrator, or even some random guy in Iron Age Denmark or Nazca culture Peru, and telling them with a straight face that all these beliefs and practices they have are actually distinctly separate things from their culture, and make up this thing called "religion" which, again, is totally separate from their cultural identity? It would be nonsensical. Can you imagine saying that to a modern Samaritan or Parsi or Kalasha or Hopi person? It's completely normal to pick up a book about the Sumerians, to read what's written there about their beliefs and practices, and just understand all that and their "religion" to be part of what Sumerian was back then. That we're an ethnic group with our own beliefs and practices is only confusing to some people in certain societies in very recent, specific contexts. (I think our existence as a diaspora for so long has further confused those same people, but I don't want this to turn into an essay.)

i love and agree with every bit of this, thank you for sending it 💙👏👏👏

482 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi I've seen you use the tag transfeminism a lot but I've never seen anyone else talk about it? Would you mind explaining it, or if not maybe pointing me in the direction of what to read to understand it? Thanks a lot in advance! <3

Yeah absolutely!

The most broad and basic premise of transfeminism is: it is feminist practice that works to incorporate the experiences of trans individuals into a feminist framework.

Depending on what theorists you engage with transfeminism is either a framework for the liberation of all trans individuals from the Patriarchy - or it solely focuses on the experiences of trans women and fems. I personally ascribe to the theories of the former, not the latter.

The best, and easiest, place to start with transfeminist theory in my opinion is with Emi Koyama's "Transfeminist Manifesto" - [ here ]. The first 10 pages are the Manifesto as originally written. The last 5 are a postscript to the manifesto and a bonus piece about racist feminism. I highly recommend reading the postscript, I find it fundamental to my own understanding of transfeminist praxis.

You can read more of Koyama's work on her website - [ here ] - and I highly recommend it! She's a profound trans and intersex advocate.

I also recommend trans theorists that pre-date Koyama such as Kate Bornstein, Leslie Feinberg, and Judith Butler. They're all nonbinary trans theorists across a multitude of identities and experiences. I love this interview with Feinberg and Bornstein a lot - [ here ].

Feinberg was prolific and the first author to truly advance the concept of marxist transgender liberation in a feminist context - hir website [ here ] has a free PDF download of hir book Stone Butch Blues and several other resources on hir work and life.

Bornstein's books Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us and Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation are go-to's of mine regarding a relatively modern history and understanding of trans identity. Her My Gender Workbook: How to Become a Real Man, a Real Woman, a Real You, or Something Else Entirely really helped shape my own relationship to my gender identity really positively and profoundly!

Judith Butler's most recent book Who's Afraid of Gender is also incredibly good, however it is incredibly dense in an academic sense. It personally takes me weeks to get through Butler's writing because it is so jammed with information - and that's not to their discredit, it's just the way they write. I highly recommend looking up some of their talks and interviews on YouTube as they're an easier introduction to their work.

Personally, I don't like Julia Serano as an author all that much, but she is still an influential transfeminist voice to be aware of because she coined and popularized the term transmisogyny. I personally have a lot of criticism of her work - particularly her seminal work Whipping Girl - because it explicitly, in her own words, is intended to be distinctly different from the work of Feinberg, Bornstein, and Riki Wilchins (another nonbinary intersex activist) and is more interested in societal perception and binary trans womanhood over politics and liberation. It also stands in opposition to a lot of the liberationist ideals of the Feminists she claims to be inspired by. I've read the whole book twice over now and in my opinion it reeks of White Feminism. I don't recommend it outside of reading it for context to the wider transfeminist discourse.

Transfeminism as a whole is also deeply entangled with the politics of Black and Intersectional Feminist politics, as many of those previously mentioned authors worked with, worked around, or were inspired by authors like Audre Lorde and bell hooks. As such I highly recommend both of them as authors as well!! I think their work really helps set the framework transfeminist theory is also built around.

I hope this helps!!

#asks#transfeminism#emi koyama#leslie feinberg#kate bornstein#riki wilchins#judith butler#julia serano#audre lorde#bell hooks

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Hierarchy of Needs

Abraham Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of human needs has profoundly influenced the behavioral sciences, becoming a seminal concept in understanding human motivation.

The original pyramid comprises 5 levels:

Physiological needs: Basic requirements for survival, such as food, water, shelter, and sleep

Safety needs: Security of body, employment, resources, morality, the family, health, and property

Love and belonging needs: Friendship, family, intimacy, and a sense of connection

Esteem needs: Respect, self-esteem, status, recognition, strength, and freedom

Self-Actualization: The desire to become the best that one can be

Maslow posited that our motivations arise from inherent and universal human traits, a perspective that predated and anticipated evolutionary theories in biology and psychology (Crawford & Krebs, 2008; Dunbar & Barrett, 2007).

Maslow developed his theory during the Second World War, a time of global upheaval and change, when the world was grappling with immense loss, trauma, and transformation. This context influenced Maslow’s emphasis on the individual’s potential for growth, peace, and fulfillment beyond mere survival.

It is noteworthy that Maslow did not actually create the iconic pyramid that is frequently associated with his hierarchy of needs. Researchers believe it was popularized instead by psychologist Charles McDermid, who was inspired by step-shaped model designed by management theorist Keith Davis (Kaufman, 2019).

Over the years, Maslow (1970) made revisions to his initial theory, mentioning that 3 more levels could be added:

cognitive needs,

aesthetic needs, and

transcendence needs (e.g., mystical, aesthetic, sexual experiences, etc.).

Criticisms of the Hierarchy of Needs

Criticism of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been a subject of ongoing discussion, with several key limitations identified by scholars and practitioners alike. Understanding these critiques and integrating responses to them is vital for therapists aiming to apply the hierarchy in a modernized way in their practice.

Needs are Dynamic

Critics argue that the original hierarchy does not offer an accurate depiction of human motivation as dynamic and continuously influenced by the interplay between our inner drives and the external world (Freund & Lous, 2012).

While Maslow’s early work suggested that one must fulfill lower levels in order to reach ultimate self-actualization, we now know human needs are not always clearly linear nor hierarchical.

People might experience and pursue multiple needs simultaneously or in a different order than the hierarchy suggests. After all, personal motives and environmental factors constantly interact, shaping how individuals respond to their surroundings based on their past experiences.

Cultural Bias

One of the primary criticisms is the cultural bias inherent in Maslow’s original model. While many human needs can be shared among cultures, different cultures may prioritize certain needs or goals over others (Tay & Diener, 2011).

It’s often argued that Maslow’s emphasis on self-actualization reflects a distinctly Western, individualistic perspective, which may not resonate with or accurately represent the motivational structures in more collectivist societies where community and social connectedness are prioritized.

Empirical Grounding

The hierarchy has also faced scrutiny for its lack of empirical grounding, with some suggesting that there isn’t sufficient research to support the strict ordering of needs (Kenrick et al., 2010).

In practice, this limitation can be addressed by viewing the hierarchy as a descriptive framework rather than a prescriptive one.

Source ⚜ More: Writing Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#writing reference#writeblr#dark academia#character development#psychology#spilled ink#literature#writing tips#writing prompt#creative writing#fiction#writers on tumblr#writing advice#story#novel#light academia#writing inspiration#writing ideas#writing resources

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELYSIUM ESSAY: KILLERS OF THE FUTURE

On the pale's connection to nihilism, and their shared theological origins.

This essay contains spoilers for Elysium Corona Mundi; that is to say, the video game Disco Elysium (2019), as well as the novel Püha ja õudne lõhn (2013), better known as The Sacred and Terrible Air.

My interpretation is heavily informed by the analysis of the pale outlined in ghelgheli’s incredible Introductory Entroponetics. Though it is not strictly required reading for this essay, there will be resonances between the two, and I heavily recommend reading it to gain a better understanding of the pale as both a diegetic and thematic element in the storytelling of Elysium.

Introduction

This is where nihilism leads. It is no longer what could be, or what could not be. It is. [1]

So says Ambrosius Saint-Miro, Elysium’s final innocence, in the ninth and titular chapter of Sacred and Terrible Air, shortly after declaring an atomic war explicitly aiming to expand the pale across the planet’s (?) entire surface. The following chapters depict a world in the process of being wiped out. Nihilism succeeds, it seems – in what Ambrosius would have one believe was an inevitable victory. But though we know now where nihilism leads, one is conversely compelled to wonder: from where did it originate?

Here in our world, nihilism is often thought of as a phenomenon of modernity, a vague force that’s risen to prominence in an increasingly secular and existentially reflexive world. The pale is treated in much the same way by most analyses of Elysium; people suppose it to be an allegory for some offspring of our modern (or postmodern) world. Interpretations differ; some point to the above-mentioned conceptualization of modern nihilism, others might think of Mark Fisher’s concept of capitalist realism and hauntology, others still might have an extremely specialized (and limited) metaphor in mind like social media. Many combine and blend together these various readings to their liking, but most seem to agree on the fundamental point that the pale’s function as a narrative device is to communicate something about the cultural condition of modernity. While it’s doubtlessly right that the pale is used for such narrative purposes, what's at risk of being forgotten here is the fact that the pale is distinctly not a modern phenomenon in the universe of Elysium. In fact, it seemingly predates recorded history. How do we make sense of that fact?

To be clear: I'm not looking to explain what the pale is - you can read ghelgheli's brilliant essay for an attempt at that - what I wish to do is propose an explanation for how the pale developed through Elysium's history to encompass two-thirds of the world. To that end I will be looking at the pale through its association with the concept of nihilism, a connection repeatedly emphasized in the text, and to explore its historical character I will be delving into the thought of what was arguably its first major theorist.

Nihilism and Morality

Christianity was from the beginning, essentially and fundamentally, life’s nausea and disgust with life, merely concealed beneath, masked by, dressed up as, faith in “another” or “better” life. Hatred of “the world,” condemnations of the passions, fear of beauty and sensuality, a beyond invented the better to slander this life, at bottom a craving for the nothing, for the end, for respite, for “the sabbath of sabbaths” [2]

Nihilism really became a *thing* in the 19th century with Russian nihilism, a radical socio-political movement grown from a milieu of moral and epistemological skepticism, seeking to tear down enshrined institutions and cultural values. While I don’t intend to explore the subject in depth right now, it bears mentioning that Elysium’s portrayal of Current Century nihilism as more of an organized political movement rather than the vague dispositional boogeyman that nihilism is so often conceptualized as today takes some clear influences from the history of the early nihilist movement in Russia; Martin Luiga’s Full-Core State Nihilist depicts the countercultural movement in the process of transition into state hegemony following Ambrosius’ ascent to power. Nevertheless, though lines were often blurry between nihilism and more radical political activity here in our world, by itself the former tended to lack a constructive side: it was a movement centered on negation above all. [3] The name ‘nihilism’ was popularized by Ivan Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons, where it was used to describe a disillusioned younger generation, and that sense of disillusionment is what has persisted in the image of nihilism to this day.

Eventually, Friedrich Nietzsche incorporated the concept of nihilism into his philosophy after hearing reports of the Russian movement, and it's arguably his interpretation of the concept which has really had the most influence both academically and colloquially. I won’t concern myself much with whether or not Nietzsche’s formulation is truly accurate to the historical character of the original movement; while he may have played fast and loose with the term, I do believe it’s his idea which ultimately reflects the core of Elysium’s nihilism.

Something Nietzsche held, in stark contrast to the understanding of nihilism as an exclusive phenomenon of modernity, was that it was not something new. Rather, it was only the most recent form of a far older idea. To Nietzsche, nihilism was immutably tied up with Christianity, and to what he called slave morality.

Nietzsche had postulated something of an (abstracted) origin story of morality. [4] He starts from the idea of two groups: haves and have-nots, masters and slaves, the powerful and the weak – and he traces the beginnings of morality to the concept of the “good.”

Well, what is good? To Nietzsche, the idea of the good begins simply as that which is synonymous with one’s nature. Or in more immediately intuitive terms, perhaps, what is good begins as what is good for oneself. A way of reflecting yourself in the world around you; all is good that is conducive to your own justice, your own benefit, your own power. This is to say that the concept of the good was affirmative, positive, constructive. The bad, by contrast, was an afterthought; it was simply a word to describe all that was not good, or worse yet hostile to that which was good. This affirmative morality was the domain of those who held power: indeed, its very conception was an act of power and domination. Their conception of the bad encompassed the character of those lower than them on the social hierarchy; the powerless and enslaved masses. Importantly, the condition of being enslaved was what was seen as bad – slavery as a social relation was not. And importantly, “bad” for the masters did not have any inculpatory dimension: people’s badness was not ontologically wrong, it did not call for punishment, it did not rouse one to righteous anger. Far from it; a predator does not resent its prey for being weak, after all.

Contrasting this, Nietzsche describes another sort of morality which takes as its basis the exact same content of that which is good in the masters’ morality; only, it no longer goes by the name “good.” This morality has reversed the traditional axes of valuation – but what was previously “good” is not just called “bad” now, either. The negative axis, which the masters termed bad, is substituted for a new concept: evil. The slaves, weary of life and helpless in fighting their oppressors, develop a deep-seated resentment for the masters which festers inside of them and can only be expressed through an imaginative capacity. It is thus that the slaves (in collaboration with a similarly impotent priestly faction of the masters) mendaciously turn the dominant morality against itself. Everything synonymous with their masters becomes evil: intrinsically, immutably wrong, and blameworthy. And its opposite – the good – is an afterthought: being good simply consists in not being evil. In this way, slave morality is premised on negation. This is Nietzsche’s (very truncated and simplified – because this essay can only be so long) psychological explanation for what eventually is crystallized in Christianity.

The idea of ressentiment is core; a hateful, vindictive, yet impotent desire for revenge. Also important is the promise of relief. Not only is satisfaction taken from the fantasy of one’s oppressors burning in Hell for eternity, but also in the idea of eternal reward, eternal rest, eternal peace. All that which one could not have in this life, bequeathed infinitely. Those are the engines which power slave morality for the next centuries. Though it achieves cultural victory with the coming-into-power of Christianity, Nietzsche describes these opposed modes of valuation duking it out on the battlefield of History for thousands of years; through different ages and societies, the dominant morality was invariably some uneasy mixture of the two. Slave morality is eventually perfected in the bourgeois class and achieves victory and dominance with the French Revolution, before culminating in its own self-immolation. The search for Truth uncovers the illusory quality of God – and from his rotting carcass, secular nihilism emerges like a butterfly from chrysalis, its theological shell cast off. While God and the afterlife may no longer be sustainable ideas, the rejection of the material world remains for the nihilists. Life-denial remains.

On the supposed innocence of Innocentic Rule

What if a symptom of regression were inherent in the “good,” likewise a danger, a seduction, a poison, a narcotic, through which the present was possibly living at the expense of the future? The desire for a unio mystica with God is the desire of the Buddhist for nothingness, Nirvana - and no more! [4]

How are Nietzsche’s ideas relevant to Elysium? We should be careful in applying them since, after all, Elysium’s history developed differently to ours. That said, it can’t have been too differently. Communism is a thing, along with its associated historical materialism, which means that the development of classes proceeded along more or less similar lines – from the specialization of labor, civilization is birthed in antiquity alongside class distinctions, slavery emerges from civilization's necessities, serfdom becomes dominant as slavery declines, the merchant class of the bourgeoisie comes into tension with the aristocracy, and finally the proletariat is born from the decline of serfdom. Likewise, we have evidence of slave morality: life-denial as virtue which secures a better afterlife, [5] the heaven and hell dyad [6] and the monotheistic god [7] are all ideas we see crop up from time to time. And, of course, overt nihilism becomes dominant near the end of Elysium’s history, a situation which Nietzsche viewed as a sort of end state for slave morality.

To get to the root of how slave morality might’ve developed in Elysium, it seems prudent to travel back to the beginning of its recorded history, to the Perikarnassian. Indeed, we find that 'Pius' is said to have invented the idea of the monotheistic god and the equality of all men before it; [8] a surefire sign of slave morality. Now, to be fair, the Perikarnassian and Elysium’s antiquity in general is shrouded in mystery, and it’s dangerous to presume too much about their beliefs. Given that 8,000 years ago is remarkably early for the invention of a monotheistic god compared to our world (where Judaism and Christianity only came to prominence ca. 2,500 and 2,000 years ago respectively) it may even be that this is an historical revision of some sort.

Regardless, Perikarnassianism is always emphasized as a theology, [9] and the one thing we can (with relative certainty) say they founded is the innocentic system. The true novelty of the Perikarnassian, thus, was the view of History as finite and teleological; the future no longer a ceaseless, unknowable onslaught on the present, but a distant destination, a promise. Potentialities erode; in the ecclesiastic view, events move along a fixed track. God has a plan and the innocence carries it out.

Let’s inquire into the name innocence for a second. What does it actually mean? Ambrosius has something curious to say about it in his speech to the citizens of the world: “I am innocent, and now you are too.” [10] What this connotes to me is a certain psychological function for those who accept innocentic rule. The Perikarnassian must have emerged from a society of widespread suffering, presumably abounding with slavery and other brutally pronounced forms of class domination, with no relief in sight. Unlike the communists of modernity, a working class revolution was literally unthinkable for the laborers of antiquity, since surplus extraction was absolutely vital for the functioning of ancient civilization. What is left but to reject the world and place faith in death itself? Such (I postulate) was the Perikarnassian zeitgeist; rejection of material existence. Nietzsche always emphasized that people can suffer through anything, so long as they believe that suffering to be meaningful. And I think this is precisely what the idea of the innocence provided: a meaning for one’s place in the world, in history. It said: you are okay. You suffer now, but that suffering is necessary. Your existence is not arbitrary; it is positioned on a path that is proceeding righteously towards liberation. The basic idea behind the innocentic system is that people defer responsibility for their own existence to an innocence, which redeems it as necessary (and thus innocent) by virtue of their own inherent necessity (thus innocence). I also believe (assuming that the Perikarnassian really was the first monotheist) that followers were assured that upon their own death, they would be reunited with God, and that the destination of History was a universal reunion in divinity, a perfectation; in other words, I think the Perikarnassian faith developed Elysium’s first robust eschatology.

We know that the pale was first studied in Perikarnassian antiquity. But there’s something peculiar about the information we get: study of the pale only reaches back 6,000 years, 2,000 years after the Perikarnassian was appointed innocence. 2,000 years is a long time. We know that by the time the pale was being studied, it surrounded the Perikarnassian super-isola, even if its inhabitants were only aware of it to the west. [11] But did the same apply when the Perikarnassian was coming into power? My proposal is that the first major expansion of the pale was the result of the invention of innocentic rule. Through a rejection of material existence, and belief in its eventual end, possible futures were narrowed down, feeding the pale. In a world like Elysium’s where thoughts have extra-physical properties, it perhaps shouldn’t come as a surprise if the first step on the road towards apocalypse was the widespread belief in its inevitability.

Nihilist Universalism

Our responsibility is thus much greater than we had supposed, for it concerns mankind as a whole. If I am a worker, for instance, I may choose to join a Christian rather than a Communist trade union. And if, by that membership, I choose to signify that resignation is, after all, the attitude that best becomes a man, that man’s kingdom is not upon this earth, I do not commit myself alone to that view. Resignation is my will for everyone, and my action is, in consequence, a commitment on behalf of all mankind. [12]

The nihilists of Elysium's modernity understand themselves to be rebels, breaking with the past in radical fashion. I suspect they’re really anything but. They are, rather, the culmination of the past 8,000 years of cultural development. Ambrosius Saint-Miro understood this fundamentally, and though we should be careful not to just take him at this word, I really can’t disagree when he positions himself as the inheritor of the innocences’ historical legacy. The widespread belief in an inevitable reckoning made it a reality; Ambrosisus was simply the one who ended up fulfilling that long-held desire.

I really think that in Elysium, nihilism should be understood as a latent principle pervasive throughout human history, present from its dawn and structuring most of its hegemonic culture as it develops into the perfected form that materializes at the end. It contaminates everything. Moralism seems like its opponent – the Moralintern talks of its duty to protect humanity from eschatologians, [13] and Mesque street nihilists talk of moralf*gs [14] – but really, they are united on the question of humanity’s future: there is none. The main difference is that the moralists believe that humanity already achieved its highest level with Dolorian humanism, whereas nihilists believe there to be one more step. The moralists enable the nihilists, because no one could be satisfied with the status quo they reify as humanity’s final form. By closing off alternative paths, they leave people with only the same choice as the ancient Perikarnassians: to reject the world entirely.

The line is likewise thin between communism and nihilism. In-universe theorists have framed communism as a secularized version of Perikarnassian theology, [15] and in our world similar comparisons have been drawn with Christianity and Judaism. The communist view of history is, if not teleological, then at least perilously close. It likewise dreams of future liberation, made inevitable by the laws of history. The difference is that in spite of its arguable origin in slave morality, communism rejects it. Communism conceives of a future beyond liberation. Its hope for the future is nearly limitless, the plans for a post-revolutionary humanity are too many to count, and it's all possible in this world, by ordinary human hands, if only we fight. [16] That is the difference; absolute negation is replaced by sublation. Communism isn’t the end, it’s a new beginning. As the ghost of Ignus Nilsen sums up: “Communism is the morning, it is jubilation!” [17] This is why Sola is actually, in spite of what some Yugo nationalists believed, a truly communistic innocence. Paradoxically, it was only by rejecting the innocentic system itself, undermining its credibility and power, that she could ever truly embody the revolutionary spirit.

One day, I was scrolling through reddit when I saw this meme posted on the subreddit r/nihilism, which I guess the algorithm thought appealed to me.

It’s a very simple, typical kind of antinatalist sentiment, but I found it illuminating. This is just suicidal ideation universalized. Instead of non-existence being preferable to one’s particular set of circumstances, non-existence is placed above existence itself. And really, this is what almost all organized religions amount to; it is the basis of slave morality.

I haven’t talked much about the ressentiment that so majorly factors into Nietzsche’s critique of slave morality and nihilism, but if we look at Zigi, Elysium’s nihilist par excellence, we see very well the consequences of a worldview based entirely on negation. Zigi’s attraction to communism extends only to its destructive potential, its utility in tearing down the middle class. Zigi’s not motivated by any kind of hope for a better world, only by his hatred for everything in it and especially those on the rung above him. As the text colorfully puts it, he wields the communist tradition’s numerous terms for the bourgeoisie “like a butterfly knife” [18] and before long is hallucinating Ignus Nilsen egging him on as he promises to rape and murder them. Zigi himself is not oblivious to his own motivations, at least not twenty years later; Ignus asks him, “Why have you been with me all these years if you don’t believe in communism?” and Zigi answers, “Because of anger towards those who’ve had it better in life.” [19]

Nihilism doesn’t discriminate. As we see with Zigi, communism can easily be bent towards nihilistic ends. So can fascism: Ambrosius comes to power by weaponizing nationalism in a similar way. [20] Nor are moralism or ultraliberalism or any other ideologies off-limits. Ambrosius understood that nihilism is anti-sectarian; people can find relief and comfort in anything as long as it's incubated in the warmth of memory. Maybe it’s the mass optimism of revolution, or the splendor of a royal parade, or the extravagance of boiadeiro movies, or the power of Dolores Dei radiating off the stained glass. “I don’t pretend to know what terrible beauty is to you. The secret to your heart.” [21] Ambrosius positions entropolism as the realization of heaven on earth, by swallowing material existence in its own memory. But is this right? When Zigi spouts Miroan philosophy, the narration tellingly informs us that the hall is filled with his “half-truths.” [22] One is compelled to ask: who will be doing this remembering? Who will be there to live in the past? Ambrosius certainly does not make a distinction between annihilation via the pale or via atomic explosion. Nihilism lays bare what apocalyptic faith has always been beneath the obfuscations: at heart, a desire to be unborn.

Death -- but for the universe.

List of references

1 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 9. Group Ibex translation

2 Friedrich Nietzsche, “An Attempt at Self-Criticism”, preface to The Birth of Tragedy. Walter Kaufmann translation

3 Michael Allen Gillespie, Nihilism Before Nietzsche, pp. 140

4 Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality (which the discussion of Nietzsche's metaethical theory in "Nihilism and Morality" is primarily drawing from)

5 “One should live virtuously in this life to live better in the afterlife…” (FAYDE)

6 “The passage between heaven and hell…”

7 “God is dead…”

8 “It’s said he *invented* God…”

9 “Perikarnassian theology…”

10 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 9. Group Ibex translation

11 “The study of the pale reaches back 6,000 years…”

12 Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism. Philip Mairet translation

13 “Protecting it from ideological highwaymen and eschatologians…”

14 Martin Luiga, Full-Core State Nihilist

15 “It replaces faith in the divine with faith in humanity’s future…”

16 “All the other plans we had. To love. To colonize the pale…”

17 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 16. Group Ibex translation

18 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 12. Group Ibex translation

19 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 16. Group Ibex translation

20 “An especially nihilistic strain of nationalism…”

21 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 9. Group Ibex translation

22 Robert Kurvitz, Sacred and Terrible Air, Chapter 12. Group Ibex translation

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

I intended for the post these tags are on to be the last thing I say about fandom misogyny for a While because I felt like I covered everything already but oh my god YES I agree So hard

In general, while I do think Princess/TLQ are permanent partners, they're also not...human. they certainly act human, but they don't carry the same societal baggage that we get saddled either by virtue of being born surrounded by other humans.

And then "marriage" as a concept is one that is so vastly different in so many cultures and time periods, and at least for the kinds of marriages I'm familiar with, there are a Lot of benefits for abusive partners and Especially men to obtain legal and financial power over their partner through marriage. Like, so much of marriage, on top of its symbolic and romantic value, is also its legal and financial ones, as well as social positioning/maneuvering-"wife" carries more weight than "girlfriend", serves as a status symbol. I don't think the Princess and TLQ would really care for that.

HEA doesn't touch on the complicated socioeconomic issues that come with marriage, especially traditional/heterosexual marriage, but it does touch on so much of the domestic unhappiness that comes with it, especially in regards to how you, the player, and the Smitten keep her in this unhappy, stale situation she's Supposed to be happy with. Opportunist even calls her "our queenly wife."

So like on top of marriage being a distinctly human construct/invention I'm not sure those two would vibe with when they can literally merge their souls together at any given moment. HEA in particular would fucking hate it. She's already Been trapped with a partner in a situation all too similar to the Traditional marriage. I could see arguments for other princesses. for a modern-AU Prisoner using marriage for tax benefits and secretly being delighted when she signs the papers, for Tower or Nightmare to make the player legally her pet in a similar fashion, for the Wounded Wild to accept it...

Never HEA. And yet the majority of StP marriage content is HEA, because she's their favorite and she's wife. Never mind how much she hated it. Never mind that her whole route is about how much she hated it. She's wife! We love her! She loves us! Of course she'd marry us, there's no other option! We HAVE to symbolically own her and tie her to us forever! Right???

#it's ridiculous.#to be clear marriage is insanely important and good in a lot of cases#people fought for gay marriage precisely because not having those legal/financial benefits was a huge fucking problem#especially when their partners died or were in medical emergencies.#but i think it's really irresponsible to act as though it can't also have HUGE drawbacks#ESPECIALLY a traditionally-structured marriage#as an institution it partially exists so a partner of a certain gender can legally own another.#this has changed a LOT in recent years but it is fairly recent (historically speaking) and still is used that way in a lot of cases.#and i'm not trying to undermine the symbolic and romantic value either#but i don't think a piece of paper or label defines a romantic relationship Especially the one on the level of TLQ and Princess's.#and for princesses like Thorn and HEA while i def relate with loving the shit out of the princess n wanting to wife her#and be her wife and her husband and have her be your wife and love her love her love her forever.#...i don't think Marriage specifically Is the way to love them forever.#the sheer level of trust issues with Thorn + HEA's EVERYTHING is like. i don't think they'd go through with it.#i think it'd give them a lot of anxiety and make them miserable.#BUT THEYRE LOVE INTEREST. SO THEY MUST BE MARRIED.#never mind that they can have a Just as serious and valuable relationship without it.#and it IS misogynist it plays into the idea that This is how a relationship between a man and woman is Supposed to be#you are Supposed to be married to fulfill the ''role'' of a wife#and when u think about what the Role of a wife in marriage is...#like. ugh. sometimes i wonder if the people who love HEA actually love HEA the princess#or if they just love the whole little narrative of leaving a miserable situation and dancing with their cute sad wife.#because i'm not sure people even really get why she's so miserable in the first place.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 feminist movie retrospective ~ day 3

LET'S GOOOOOOOOOOO WOMEEEEEN 🔥🔥

*cough* Sorry. Uuuuuuuh. Well. Do I need to introduce this movie? It's fucking Furiosa. This is radblr here, I assume we've all had at least one wet dream about Imperator Furiosa 🫡 raise your hands. No? Just me? That was a bit by the way. I'm kidding. I swear I am... Let's talk about Furiosa : A Mad Max Saga ! Spoilers will be in red. Graphic descriptions of violence and sexual slavery ahead.

Watched : May 24th at my city's independent theater. The showing was pretty empty.

One thing you gotta know about me, I'm a fangirl by nature. But I'm not a forgiving fan. I'm not the kind to just be happy that an IP I like is getting some new content and be happy with anything I'm given. I'm a really demanding fan. If an IP I like is getting new content, I'm gonna need it to be up to the task. And as a long time George Miller fan and an absolute Mad Max Fanatic, I expected a LOT out of Furiosa.

I think this movie can be enjoyed even with no prior knowledge of the MM series. Personally, I'm glad I watched these films in the order that they came out and I would recommend you do the same, but if for whatever reason the rest of the series doesn't interest you and you just wanna see Furiosa, go for it, there's no big story thread that will confuse you.

Mad Max is a series of dark adventure movies set in a post-apocalyptic world, an unknown number of years after our time. In the first movie released in 79, the economy and the state seem to have collapsed but there is still a semblance of an organised modern society amongst the violence. From the second movie onward, it all goes to absolute hell. The first film had a very limited budget and you can tell the team was working with what they had and were still finding their footing. It was a very different type of film but it was already a massive success, a very original concept, and still to this day probably my favourite entry in the series in terms of narrative.

Emboldened by the massive success of MM1, George Miller and his team got more freedom, more money, and started dreaming big. Every film from MM2 onwards became more and more balls to the walls insane. It all reached a climax with Fury Road in 2015, the most expensive and ambitious film in the series.

Since MM2, the franchise has had a strong visual and thematic identity with a lot of easily recognisable elements. A fashion heavy on leather and chains that seems BDSM inspired, a strong narrative presence of children and parental themes, a cast full to the brim with actors/extras who are visibly disabled/have congenital physical quirks, and a strong environmental message. The world of Mad Max is a seemingly endless desert where fuel has become the most sought after ressource and engines/vehicles are deified. It's big, it's empty, it's dry, and it's distinctly... well, distinctly australian.

Furiosa : A Mad Max Saga is the fifth movie in the series and as the name implies, the first one to not have Max as the protagonist. It is the origin story of a character who was introduced in Fury Road.

The story follows the titular Furiosa as she gets kidnapped at a young age from her home, the "Green Place of Many Mothers" by a biker gang from the desert who seeks to take over the Green Place for resources. As Furiosa is taken deeper and deeper into the Wasteland, she is caught in the crossfire between two feuding warlords, Immortan Joe (who will then become the main antagonist in Fury Road) and Dementus. The story takes place over many years, showing us what happened to Furiosa to make her the ruthless Imperator we know her as.

To start, a few notes on this film's relationship to the previous one : I think it's pretty flimsy. An origin story is supposed to give us additional information about an interesting character, and while the movie does add new elements, i just don't think it's enough. Just so we're clear : i think Furiosa is AMAZINGLY developed in this film. She's an incredible character. I just wish the film gave us more new elements. The Green Place is a major plot point in MMFR, but here it appears on screen for less than 5min. And more importantly, we never get a definitive answer as to what happened to it?! It's frustrating because as much as i love this movie's story, i think it's a bit of a false advertisement. MMFR tells us all about this heavenly place Furiosa is from, and halfway through it's revealed to have died/been destroyed. That was a hugely dramatic moment for Furiosa in FR!! We're then told we're gonna get an origin story for her, which opens with a scene in the Green Place, then the film leaves it behind to focus on the same areas we know from FR, and we're left with the same questions than 9 years ago! Showing it in a few shots doesn't matter in the end, we have gained ZERO new information about it. And most of what we "learn" about the main character in this film, apart from elements related to newly introduced characters (Dementus, Jack), is stuff that we could have guessed ourselves. It showed us events yes, but too few elements of characterisation to make this a satisfactory origin story.

There's also an issue with the movie's status as a prequel, but that's a common problem that isn't exclusive to Furiosa. To put it simply, it lacks stakes. We know Furiosa survives because we've seen her older. We know the Green Place dies off anyway. And more importantly, we already know when the conflict begins that Immortan Joe will be victorious, the whole point of FR was that he was top dog. It was a strange decision to focus so much on a conflict between Immortan Joe and ANOTHER warlord, as if we don't all remember the previous movie. Honestly, a film that follows Furiosa's mother in the Green Place, in conflict with Dementus, then ENDS with the mom dying and Furiosa being taken would have been a better choice i think! It would have been less marketable probably, but more compelling. No one would have been confused as to what happened to Furiosa between the Green Place and Fury Road. It's pretty easy to fill in the blanks with the info we got before this film. Anyway, that's enough complaining. Again, just so we're clear, i don't think this film is badly written. In fact it's the opposite! The film tells its story very well, i just personally, as a fan, wish it had told a different story.

(edit : oh yeah I forgot, there IS one massive plot hole in the film. The arm thing. Uuuuh what happened there. How... What... But hey this is Mad Max, it's told like a legend/tale. So we'll just say that detail was lost in time lol)

Holy shit, writing in bright red for 20min hurt my eyes so bad lol why did i do that.

Apart from storytelling decisions (as seen in the spoiler section above) the only other criticisms i have are : one, absolutely TERRIBLE looking CGI fire, and two, an over-abundance of fade to blacks in the editing. But that's just about my personal tastes, these always feel like they make movies seem slower to me, but it might be just me. Apart from that, well, i loved everything, so let's talk about the rest.

The movie is incredibly atmospheric. The music by Junkie XL (who had already delivered a banging ost for Fury Road) is perfect, and is incorporated into the action so naturally. It's intense, it's poetic, it all works so well. Miller's movies always have great sound in general, this one is no exception. The universe is well developed and feels lived in, as usual with the franchise. There's something interesting to look at in every shot, there's so much attention to detail everywhere. The acting is PHENOMENAL all around. I've been a huge fan of Anya Taylor Joy since Split, and she didn't disappoint here. But the biggest stand-out by far is Alyla Browne as kid Furiosa. Good child performances are far from common in blockbusters, but she's undoubtedly the star of the show here. I hope she has an amazing career ahead of her. Chris Hemsworth as Dementus was a surprise, i've almost exclusively seen this guy in Marvel slop, but he gets to shine here and he's fucking great?? I think it's the first time i hear him use his real australian accent in a role and it works great with the character. His physical comedy and line delivery are always on point, he was by far the most entertaining character. That's no surprise, Mad Max ALWAYS shines with its insane villains.

The movie's incredibly well shot and makes plenty of daring and interesting stylistic choices. It's stunning to look at. The CGI is significantly more visible than it was in FR and i'm... not sure why... The budget is after all very close to the one of the previous film, and the production was to my knowledge not rushed. On one hand the film is 30min longer but on the other hand it's also much less action packed. It might be a choice..? George Miller and his team have always handed the effects very well. The CGI in Fury Road was SO good that still to this day some people believe that the film only had technical effects with no digital help. It was invisible.

Here the effects work the same way (they enhance impressive real-life stunt work) but they are distinctly more plastic looking, and the vibe is very different. For a lot of spectators this was a problem, which i understand. For a lot of people, CGI exists to enhance visuals in a way technical effects can't, and is successful only when it is absolutely unnoticeable. That's not my opinion. As long as it's well thought out, well designed, well animated, and entertaining, i love fake ass looking films :D

(i've seen someone complain about a time-remapping issue in the CGI but even when i rewatched specific scenes i didn't notice anything, so it's probably a nitpick only animation professionals will care about.)

It's not just the visuals and the effects that feel like it was made specifically for me. The whole vibe is exactly my thing, i can't lie... There's an impressive action set-piece midway through the film that lasts almost 15 minutes, and it's... a lot. There's a lot happening at once, it's purposefully very busy to the point of being overwhelming, and some spectators found it to be too much. But fuck, i can't relate. Inject that shit straight into my bloodstream all day every day. It's insane, it's silly, but i'm a James Cameron/Whachowski fan, i don't care i love that shit. (i only like the Wachowski as artists, not as people...💀💀)

As silly as the action sometimes get, the film is actually very serious overall. It's clearly less campy and more focused than Fury Road was. As disappointing as i found some narrative choices to be, i have to admit that the story IS the film's biggest strength.

It clearly follows directly from the last movie in terms of style. But in terms of substance, i think it's closer to the original trilogy. (and i actually think this is why the movie flopped. Fury Road was already too expensive and i think it barely made its money back. But since then the movie has gotten quite the cult following, and a lot of these people were disappointed by Furiosa because it wasn't Fury Road 2. It's not a fast-paced never-ending chase, yes there's action, but it's mostly a serious, slow, silent, character driven film. And i'm really happy about that. I didn't want this saga to turn into 2hour stunt showcases. Yes i love FR, but i'm glad it turned out to be the exception in the series and not the new norm.)

As I said earlier, the best part of this film is its story. It has a great tone, it fits well in the series, the ending is frankly amazing. Some people found it anticlimactic and... Uh?? I don't get it. It was beautiful and coherent with everything we saw before. If you're like me and you're always a bit frustrated because movie antagonists rarely get the comeuppance they deserve, because the hero is like "no, I'm better than that 🙂↔️" then rest assured I LOVED that ending. Furiosa you're so sick and twisted. I am in love with you. WHO SAID THAT

Even tho the film is a prequel, the story takes plenty of unexpected turns and expands on the universe in a way that will please all fans of the series I think. And it's also, say it with me now : a great feminist tale.

I won't insult your intelligence by explaining why it's significant that the only safe haven in this deadly desert is named "the Green Place of Many Mothers". As I said at the beginning of this review (approximately 150 years ago), children and parenthood have always held a special place in this franchise. And since Fury Road, it's more specifically motherhood and women that take center stage. The actions of the two antagonists of this film cannot be removed from their maleness. Dementus is a creep, Immortan Joe is a monster. He holds all the power and resources of his community and collects women like livestock.

In the world of MM, People have started being infected by unknown influences and the population is mutating. Growing more and more unhealthy, less and less fertile. Those with no congenital disabilities and malformations are called full-lifes. Immortan Joe keeps a harem of women, locked up in his palace. All wearing chastity cages. Their prison is pretty, inviting, clean, the illusion of a better life. Forced to be raped by their master, they must give him a full-life male baby. Three strikes (as in, failed or disappointing pregnancies) and they're out. But they're not "out" like all the random men trying to survive on the outside. They become milkers. Supposedly kept pregnant as long as they're able to, to make more child soldiers for Immortan Joe.

When kid Furiosa is traded/sold to Immortan Joe, she becomes a future wife. She lives with the other full-life women, terrified of the master's oldest son who is a bit too interested in her. She decides to shave her head and run away from the prison to instead work as a mechanic. (Yeah it's one of these stories where no one can recognize sexual dimorphism and as long as you shave your head and don't speak you pass as male)

We see her slowly learn the ropes and work up the ranks, until she is the Imperator we all know. When her identity is discovered (before she is an imperator) Immortan Joe doesn't suggest making her a wife again. For two reasons : one, she is so talented at what she does that it is more useful to let her keep her current job, and two, by doing what she has done, she has effectively ruined her womanhood in the eyes of men, which makes her unworthy of breeding with. The wives become very important characters and a crucial plot point in Fury Road, and it's abundantly clear that Furiosa is not treated by men the way they are, even tho she too is a full-life female. To them she is better and lesser at the same time. She becomes a strong, powerful woman; and it terrifies them.

Furiosa is a great film about an even greater character. And I'm not just saying that because I love seeing myself be represented on screen (bald women 🩷). If you like Mad Max, I hope we can agree that this franchise needs more varied POVs like this. Not that I dislike Max, he's my special boy. It's just nice to see different corners of this world. If you don't know Mad Max, I hope this introduces you to it and you end up loving it as much as I do :)

Final rating : FURIOSAAAAAAA/10

This film gets the official Léna seal of approval! It's one of the best of 2024! Here's a link to the trailer.

#hey quick edit ❗#i realized while rereading that maybe i didn't express myself in the best way in the last part.#i'm not saying that this is a good feminist tale/that furiosa is a powerful woman BECAUSE she hid her sex from the other characters#this is just one of the many things she does in her journey. at the end of the day this is a character who was raised in an feminist utopia#who is taken to this horrible place#and she sacrifices her own safety to protect women who are NOT weaker than her; but who don't know that there could be a better life out#there for them because that's simply how they were raised. the wives; as we then see in FR; are very powerful women as well.#just not in the action hero way that Furiosa is#Léna's originals and additions#MY FANDOMS#film yapping tag#review tag#radical feminism#radblr#movie tag#mad max

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

very interesting to me you classify israel as non western. to me as someone from the global south it slots under western

Shalom! Thank you for giving me an excuse to flex my sociology degree! (Also, sorry you accidentally gave me an excuse to flex my sociology degree.) The "Western World", like any social concept, is a term that's mostly bullshit and subjective. But it does have some important factors that allow us to determine what counts, and what doesn't. Usually, when people think about the West, they think about globalization and industrialization-- Israel has that in spades, and I imagine that's what you're referring to when you consider it to be Western. But that's just the economic element. There's also a crucial cultural element. Otherwise, Singapore would be Western, despite being squarely an Eastern nation by any other metric.

The foundation of Western society is rooted in both Greco-Roman and Christian philosophy. Those two forces have shaped how Western nations think and act, and are responsible for modern Western conceptions of race, family, nationhood, morality, and philosophy. I won't say that none of those concepts were picked up by Ashkenazic or Sephardic Jews living in the European diaspora over the years. However, the basis of Jewish culture, identity, and ideology predates modern Western civilization by hundreds of years. We existed before any modern ideas of nationalism, before the concepts of racial identity and ethnicity, and before the separation of religion and culture. And Israel is made up of the world's Jews. Mizrahi Jews, who spent their diaspora in the Arab World (distinctly non-Western!) account for an equal or slightly greater percentage of the Israeli population than Ashki Jews.

I've personally never seen an academic source refer to Israel as Western, and I've never seen a map of the Western World that highlights Israel in the same colour as America, Canada and Western Europe. If you have, though, Anon, I'd love to see it and learn their reasoning! Hope you're having a wonderful day.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Review on Epic The Musical

"Epic The Musical": A Modern Odyssey of Sound and Story

I. Introduction: A Modern Epic's Resurgence

The enduring narrative of Homer's Odyssey stands as a foundational pillar of Western literature, a timeless saga of homecoming, relentless perseverance, and the human spirit's unwavering resolve against formidable challenges. Its profound thematic explorations, encompassing the deep-seated yearning for nostos (homecoming), the societal imperative of xenia (guest-friendship), and the hero's transformative journey, have resonated across millennia, firmly cementing its place in the literary canon.1 The poem's distinctive non-linear chronology, which immerses the audience

in medias res and unfolds much of Odysseus's tale through his own retrospective narration, has historically invited a myriad of interpretations and adaptations, allowing each successive era to discover its own reflection within the ancient narrative.2

In a groundbreaking contemporary reimagining, "Epic The Musical," conceived by the visionary Jorge Rivera-Herrans, has emerged as a captivating phenomenon that has seized the attention of a global audience. Structured as a nine-part series of sung-through concept albums, this ambitious work boldly reinterprets the ancient Greek myth, infusing it with a dynamic blend of musical theatre, the vivid storytelling of anime, and the immersive soundscapes characteristic of video games.5 This unique fusion culminates in an experience that is both innovative and deeply immersive. The musical's distinctive development and its meteoric rise to widespread popularity, largely propelled by online platforms such as TikTok, underscore a significant paradigm shift in the creation, distribution, and consumption of theatrical works.6 This pioneering approach has not only fostered an unprecedented level of accessibility but has also cultivated a vibrant and highly engaged community, demonstrating a potent new model for artistic dissemination.7

The digital-first approach adopted by "Epic The Musical" fundamentally reshapes the landscape of musical theatre, making it available to a vastly broader audience. Unlike traditional stage productions, which are often constrained by geographical limitations and financial barriers, "Epic" has directly reached a global listenership through streaming services and social media. This enhanced accessibility has not merely expanded its reach; it has actively cultivated a deeply engaged and participatory fanbase. Evidence of this strong connection is abundant in the proliferation of fan-created animatics—animated storyboards accompanying the songs—and the lively discussions surrounding character designs and staging that transcend the audio experience alone.7 This innovative model suggests a broader cultural movement in artistic consumption, moving towards more interactive, community-driven forms of engagement. The transparency with which Rivera-Herrans documented his creative process, meticulously sharing ideas, edits, and rewrites on platforms like TikTok, further deepens the bond between creator and audience.8 This transforms passive listeners into active participants in the musical's evolving journey, challenging conventional notions of what constitutes a "musical" and paving the way for new expressions of theatrical art. This report will demonstrate how these artistic liberties, far from being mere "inaccuracies," serve to deepen the story's thematic exploration, solidifying "Epic The Musical"'s place as a truly exceptional and "very very good" modern adaptation.

II. The Sonic Tapestry: A Deep Dive into "Epic The Musical"'s Songs

Masterful Composition and Genre Fusion: Jorge Rivera-Herrans' Musical Genius

Jorge Rivera-Herrans has garnered widespread acclaim as a masterful composer, demonstrating an exceptional aptitude for weaving intricate musical motifs that not only distinctly define characters but also powerfully propel the narrative forward.5 The musical draws its inspiration from a rich and diverse array of sources, including the established traditions of musical theatre, the dynamic and often visually driven storytelling of anime, and the immersive soundscapes characteristic of video games. This ambitious fusion culminates in a rich tapestry of various musical genres.6 This deliberate and expansive approach to genre integration creates a distinctive sonic identity for each of the nine sagas, ensuring that every album release is memorable and that each segment possesses a unique sound and feel, thereby preventing any sense of monotony across the extensive work.5

The compositional range exhibited throughout "Epic The Musical" is truly remarkable, encompassing both adrenaline-fueled songs that drive the action with palpable energy and soul-crushingly beautiful ballads that delve into profound emotional depths.7 For instance, the song "Storm" underwent a deliberate and significant transformation during its development, shifting to a complex 7/8 time signature and incorporating epic choir vocals. This meticulous crafting effectively evokes the overwhelming and divine presence of a colossal storm, demonstrating a keen understanding of how musical structure can enhance narrative impact.10 Similarly, "There Are Other Ways" stands out as a prime example of the musical's impressive genre versatility and willingness to experiment, notably blending elements of bachata with a striking key change and intricate overlapping vocals.10

Vocal Powerhouses: Performances that Elevate the Narrative

"Epic The Musical" is brought vividly to life by a cast of truly remarkable vocal talents.7 Jorge Rivera-Herrans himself delivers a compelling and nuanced performance as Odysseus, infusing the central character with depth and complexity.5 The ensemble features standout contributions from artists such as Troy Dohert as Hermes, Talya Sindel as Circe, Steven Rodriguez as Poseidon, Ayron Alexander as Antinous, and Teagan Earley as Athena.7 Reviewers particularly highlight Rodriguez's masterful ability to convey Poseidon's character progression, evolving from a calm fury to an unhinged menace purely through his vocal delivery, allowing listeners to almost viscerally perceive the drowned depths awaiting those who incur his wrath.11

A brilliant creative decision, particularly crucial for a musical primarily experienced through audio, is the consistent use of distinct instrumental motifs for key characters. Odysseus is accompanied by a guitar, with its type subtly shifting to reflect his changing moods and intentions; Athena is marked by soothing piano sounds; Poseidon by a powerful trumpet; and Polities by higher-pitched instruments like the marimba.5 These instrumental cues serve as vital non-visual identifiers, helping listeners track characters and their emotional states, especially given that the musical has not yet debuted on a traditional stage.5 For a musical primarily experienced through listening, these auditory markers are not merely stylistic choices but critical narrative devices. They allow for sophisticated characterization and emotional tracking without the need for visual aids, making the complex story remarkably easy to follow and understand.5 The deliberate variation in musical genres and tones across the sagas is not just a display of stylistic flair; it is a profound reflection of the evolving psychological and physical landscapes of Odysseus's arduous journey. The shift from lighter sounds to darker instrumental tones mirrors Odysseus's transformation and the increasing gravity of his challenges, demonstrating how the musical form itself becomes a powerful vehicle for thematic expression.5

Lyrical Brilliance and Emotional Resonance: Crafting a Story Through Song

The musical's lyrics are consistently praised for their exceptional quality, demonstrating extremely well-written prose and clever wordplay that significantly enrich the narrative.11 They possess a remarkable ability to deliver a potent emotional punch precisely when required.11 Songs such as "Wouldn't You Like" 12 and "There Are Other Ways" 13 exemplify this lyrical depth, showcasing complex character interactions, nuanced moral dilemmas, and the subtle interplay of persuasion and manipulation, as seen in Hermes tempting Odysseus with power or exploring Circe's intricate relationship with him.

Emotional moments throughout the musical are profoundly amplified through the powerful medium of song. The visceral gut-punch experienced when Odysseus encounters a previously unknown dead character in "The Underworld" 11, or Penelope's heart-wrenching line in "The Ithaca Saga" 8, are rendered all the more impactful by the raw emotion conveyed through the vocals and the underlying musical composition. This synergy allows the listener to deeply connect with the characters' experiences, fostering a powerful sense of empathy.8 The vocal performances are not just technically proficient; they are crucial conduits for the musical's emotional depth and narrative complexity. The portrayal of Poseidon, for example, utilizes vocal shifts to underscore the god's escalating vengeance and psychological instability, transforming him into a more terrifying and compelling antagonist. Similarly, Penelope's raw emotion in her final songs conveys the profound weight of her two-decade wait and unwavering love, enabling the audience to imagine themselves in the same position and fostering deep connection.8

Highlighting Key Musical Moments and Fan Favorites

The musical encompasses an impressive forty songs spread across its nine concept albums, or sagas 8, culminating in a nearly two-and-a-half-hour emotional rollercoaster.8 Popular tracks, as indicated by streaming data and audience reception, include "Wouldn't You Like," "Just a Man," "Hold Them Down," "Love in Paradise," and "Warrior of the Mind".14 Other fan favorites and highlights, as identified by the creator himself, include "Open Arms," praised for its moments of levity that later acquire profound emotional weight, "There Are Other Ways" for its musical uniqueness, "Little Wolf," and the meticulously crafted "Storm".10 Songs associated with powerful figures like Poseidon and Hermes are also frequently singled out for their significant impact.10 The final "Ithaca Saga" provides a beautiful and fitting conclusion, masterfully weaving the entire narrative together through continuous callbacks to previous sagas via score and song. This intricate design allows listeners to draw deep connections and appreciate the complex tapestry of the musical's journey.8

Table 1: "Epic The Musical" Sagas and Featured Songs

This table provides a structured overview of the musical's progression, aligning specific songs with their narrative "sagas." It helps listeners understand the chronological flow of the story within the musical's unique episodic release format, which is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the work. It also highlights the sheer volume and thematic grouping of the musical's impressive tracklist, serving as a guide to its musical landscape.

Saga Name

Act

Key Songs (Examples)

Thematic Focus/Brief Description

Troy Saga

Act 1

The Horse and the Infant, Just a Man, Full Speed Ahead, Warrior of the Mind

Odysseus's final moments at Troy, the difficult choice to commit infanticide, setting his path.

Cyclops Saga

Act 1

Open Arms, Polyphemus, Survive

Encounter with the Cyclops, loss of Polities, Odysseus's cunning and "mercy."

Ocean Saga

Act 1

Remember Them, My Goodbye, Storm, Luck Runs Out, Ruthlessness

Divine punishment from Poseidon, crew's demise, Odysseus's growing ruthlessness.

Circe Saga

Act 1

Keep Your Friends Close, Puppeteer, Wouldn't You Like, Done For, There Are Other Ways

Encounter with Circe, Hermes' intervention, themes of control and persuasion.

Underworld Saga

Act 1

The Underworld, No Longer You, Monster, Suffering, Different Beast

Odysseus's journey to the land of the dead, confronting inner demons, shedding remorse.

Thunder Saga

Act 2

Scylla, Mutiny, Thunder Bringer

Sirens, Scylla, crew's betrayal and death, Odysseus's ultimate survival.

Wisdom Saga

Act 2

Legendary, Little Wolf, We'll Be Fine, Love in Paradise, God Games

Telemachus's journey, Athena's intervention, Odysseus's captivity with Calypso, divine politics.

Vengeance Saga

Act 2

Not Sorry for Loving You, Dangerous, Charybdis, Get in the Water, Six Hundred Strike

Odysseus's escape from Calypso, confrontation with Charybdis, brutal defeat of Poseidon.

Ithaca Saga

Act 2

The Challenge, Hold Them Down, Odysseus, I Can't Help But Wonder, Would You Still Love Me

Penelope's test, the suitors' brutal demise, Odysseus's reunion with Telemachus and Penelope.

Note: Song lists are illustrative and may not be exhaustive for each saga.

III. Reimagining the Myth: Creative Departures from Homer's Odyssey

The Core Narrative: Shared Foundations and Enduring Themes

At its fundamental core, "Epic The Musical" remains deeply anchored in the foundational narrative of Homer's Odyssey. Both works chronicle the heroic king Odysseus and his arduous ten-year journey back to Ithaca following the Trojan War. They depict his encounters with a succession of mythical perils and his eventual triumphant return to reclaim his kingdom and family.1 Furthermore, both narratives explore shared, timeless themes that resonate across civilizations, including the profound desire for homecoming (

nostos), the trials and tribulations inherent in wandering, the paramount importance of loyalty—especially within familial bonds—and the ultimate triumph of justice.1 Both also delve into the complex transition a warrior must undergo, from a life defined by warfare back to the responsibilities of domesticity and kingship.3

Odysseus's Transformed Heroism: A Deeper Exploration of Moral Ambiguity

Homeric Odysseus: In Homer's epic, Odysseus is primarily depicted as a cunning, resourceful, and often audacious hero, whose actions are largely driven by his nostos and his ambition to reclaim his identity as a husband, father, and king.1 While he possesses certain flaws, such as his taunting of Polyphemus or his men's recklessness with Helios's sacred cattle, his deeds are generally framed within a classical heroic context. His retribution against the suitors, for instance, is portrayed as a justified restoration of order and divine justice.1 Significantly, the Homeric narrative does not include any act of infanticide, nor does it depict him physically assaulting a god.

"Epic" Odysseus: The musical presents a markedly darker, more morally complex, and psychologically scarred Odysseus. His journey commences with a profound and disturbing act of violence: the forced killing of the infant son of Troy's Prince Hector, a deed compelled by a "vision" from Zeus.15 This pre-emptive, morally compromising act immediately establishes the grittier tone of "Epic" and highlights Odysseus's internal conflict, setting the stage for his gradual transformation into what he fears might be a "monster".15 His decision to show "mercy" towards the Cyclops, by blinding him rather than killing him, is ironically punished by Poseidon precisely for

not killing him, a direct inversion of the conventional Homeric portrayal of divine justice.15 This unique twist serves as a powerful catalyst, arguably fueling Odysseus's later embrace of extreme ruthlessness. By the Underworld Saga, Odysseus consciously sheds all remorse, his focus narrowed solely on returning to his family, indicating a profound psychological hardening.15 The Vengeance Saga culminates in a shocking and monumental departure from the original myth: Odysseus brutally beats Poseidon with his own trident until the god yields.15 This unprecedented display of mortal power over a deity symbolizes Odysseus's complete embrace of "ruthlessness" as a form of "mercy upon ourselves," a philosophy Poseidon himself suggests.16 His eventual return to Ithaca is characterized by the brutal, unflinching slaughter of the unarmed suitors, with no mercy shown.15 This visceral act is immediately followed by his poignant confession to Penelope that he is "no longer the kind man she knew" 15, underscoring the profound psychological cost of his journey and survival.