#monogatariposting

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hitagi End - An Analysis

Well, that’s it, folks. We’ve finally reached the end of the Monogatari series. It’s even right there in the arc title.

Hold on, I’m being told that there’s another whole season. What the fuck, I’ll be well into 2025 by the time I’m done with this.

But yeah, as usual with the naming scheme the second word seems to be the thing our title character has to confront - Hitagi is in active resistance against the End, and whether in the abstract form of the conclusion of the series itself, or the more literal threat of Sengoku Nadeko, there’s one common feature. Graduation.

One thing I remember vividly from Koimonogatari - from the first time I watched Koimonogatari, several years ago - is Kaiki’s offhand statement that Hitagi and Koyomi will probably break up in college. He says it so matter-of-factly, but it’s not something I ever considered, watching the rest of the series. I was fully immersed in the teenage perspective, convinced that nothing would ever end. It takes the perspective of a washed up older man to break the illusion, I suppose. You always hear the same complaint about romance manga - there should be more focus on after they’re already in a relationship. Getting together shouldn’t be the story’s end.

One reason why it might be the story’s end is because as long as it ends there you can convince yourself it will last forever. Their relationship will never sink to the level of mundanity, of lovers’ quarrels - there will never be the possibility of being interested in someone else, finding someone else, being replaced.

That is the kind of idealistic, indulgent, static ending that Sengoku Nadeko desires, and as a result is the kind of ending that Senjougahara Hitagi fights against.

This is where I say something about Kaiki Deishuu. Something to make sense of what he’s doing in this story. He’s a man in search of an ending, I could say. Ever since the death of Gaen Tooe, he’s been looking for a way to move on. Perhaps this is why he tells Nadeko the same cause of death - the person you have a crush on died in a car accident. So mundane, so unexpected, so implausible. He thinks she will accept it. Does he?

He’s a man who’s already met his end, I could say. Such is the fate of the specialists. They’ve already graduated, already long since handled their personal agreements and disagreements. They’re stuck, now, bound to their own nature, their own rules. They appear only as supporting characters, never the protagonist. Well. I guess that’s a lie.

In adopting narrators other than Koyomi, Second Season shifts the focus away from his obsession with helping and connecting to others. Koyomi’s interactions with and idealization of women results in a sense of distance - he struggles to see himself in them and their problems. How much of his attempts to cross that distance are really just attempts to help himself?

This dynamic collapses when the female cast, facing their own issues, are made protagonists in their own right. They experience themselves as the Other, & Koyomi’s standard process of understanding the girl by first understanding the oddity becomes in these cases a process of self-exploration.

And yet here we are, back to seeing a male protagonist confronted with the issues of women that he struggles to understand.

I don’t mean to rag on men, exactly, I just think back to how there tends to be less distance between Koyomi and other men, how he’s more capable of seeing them as another version of himself, and I think that the best explanation for Kaiki’s presence here is that he’s filling in.

He himself thinks so, although it’s Oshino, and not Koyomi, that he considers.

Regardless, the parallels to Koyomi are established firmly enough by the ending. Kaiki was poison to Hitagi but a surprising help to Nadeko, while Koyomi is the opposite. Put that way, their differences and similarities seem readily explicable. Koyomi saves people. He forgives the harm they do to him. It works for the prickly Hitagi, who needs a pillar of support, but not Nadeko, who needs to be told that she isn’t a victim.

Kaiki lies to people, but that doesn’t mean he’s trying to hurt them. Ononoki proposes a reading of his involvement with Hitagi where he had no ill intentions whatsoever. He didn’t try to free her from the crab simply because he didn’t think it would help her to regain what she had lost. He caused her parents’ divorce to keep her from under the thumb of her mother. He even swindled the cult, although more as an act of revenge than anything. Perhaps there was some impropriety in their relationship, perhaps he exploited her feelings for him, but our understanding of the events is vague enough to give him the benefit of the doubt if we really want.

Kaiki fails to help Hitagi, not (just?) because he’s trying to scam her, but because he’s fundamentally incapable of being honest with her. All his actions move around her and ignore her wishes.

When it comes to Nadeko, on the other hand . . . I mean, it doesn’t initially seem like he’s doing much better, does it. He has no luck with his manipulations, with currying favour, with bold untruths. In the end though, the way he helps Nadeko is a lie that they both know is a lie. Really, it’s more like telling her a story.

And I’ve written before about how Nadeko needs stories.

Kaiki doesn’t tell her anything that another person couldn’t have. Koyomi, Hitagi, even Nadeko herself is probably aware of similar advice on some level. Don’t throw your life away pointlessly. If you want to do things, then you should do them. You can’t succeed unless you try.

Kaiki’s talent is simply in recognising that Nadeko needs to hear it. Koyomi wouldn’t have thought to say it, because he doesn’t know why she became a snake god. She doesn’t want to tell him either. He’s stuck.

But it’s not as if Kaiki has some unique insight into her psychology that lets him work this out. As he puts it, he’s not like Oshino. He didn’t ‘see through’ Nadeko, he just straight up ‘saw’ it. He broke into her room, twisted open the lock to her closet with a 10 yen coin and fucking looked. Her parents didn’t know what was in there, Koyomi didn’t know what was in there, Tsukihi didn’t know, Oshino didn’t know, even Hanekawa who heard about it from someone else and thought it might be an important detail couldn’t possibly know without opening the god damn closet.

This is where Kaiki’s habit of working around people becomes useful. Because more than anyone else, he recognises that Nadeko might be fine as a god, just as he thought Hitagi might be fine staying weightless two years ago. He’s not trying to save her. He’s not trying to do what’s best for her. He’s simply trying to scam her, with all the lack of respect for her personal belongings that implies.

This establishes, perhaps, an important difference between Koyomi and Kaiki, but it also establishes a similarity. In dealing with oddities - in dealing with people - the key is getting to know them.

This is something Koyomi struggles with, out of a fear of being too forward, a fear of hurting them, a lack of appreciation of his own value, as a kind of half-person, a fake person, that could only weigh others down. Kaiki embraces his nature as a fake and adopts only the most rational and most unscrupulous methods of approaching others.

The question, I suppose, is why? What does Kaiki get out of playing a character that informs all of his actions without explaining them? What does he get out of remaining unknowable even to himself, reacting with surprise to his own feelings and motivations? What does he get from acting without thought, tossing away caution, tossing away patience, and tossing away money in an attempt to toss away the past?

Kaiki values money for its endless acceptability, its exchange value. He doesn’t wish to have money, he wishes to use it, and in keeping with this philosophy, he considers nothing irreplaceable, not even himself. The person named Kaiki Deishuu is deliberately false, deliberately contradictory, and he’s long since given up on getting to the bottom of that particular well.

I begin to understand why he comes up, now, in relation to Nadeko, who is lost in a web of her own identity.

Sengoku Nadeko is telling herself a story. She has to, in order to not hate herself. She is, and will continue to be, in love with Koyomi-oniichan. This isn’t something that motivates her actions in the conventional sense so much as a wall to keep out the world, to assert that she is normal. So why does she still hold onto it, in this situation where it has become so far beyond normal?

Because she considers it part of herself. She is still playing the role of Sengoku Nadeko, and she can’t cast aside the most Nadeko piece of herself, the piece that she has spent the most time and effort showing off to other people. It would call her existence into question, make her look fake, make her feel empty. The sense of normalcy she’s trying to achieve is not in how other people see her, it’s in how she sees herself. She takes the pieces of herself that are left, the pieces of herself she’s been given, and pulls them together into a story that makes sense. To her, loving herself means never changing, never throwing parts of herself away, never identifying a problem in her own behaviour.

She’s happy, Kaiki thinks. It feels a little different from the end of Otori, where Kuchinawa was still presented as a separate existence. He no longer pokes at Nadeko’s insecurities, at least not obviously. In recognising her own role in the whole affair, Nadeko is no longer worried about hurting others, of being seen as a victim, because she fully acknowledges herself as the one with all the power in her interactions. Godhood is an unusual role for her, but she seems happy to take it up, viewing her job as responding to the prayers of worshippers. It's a much simpler, more transactional view of social relations than she had to navigate as a human. She likes people who are nice to her and doesn't like people who aren't.

Ultimately, though, she's still playing a part, putting on a performance for Kaiki’s benefit. Her cutesy habits as a god are a far cry from the more genuine rage she expresses in the classroom in Otori. But then again, she doesn't have to worry about that, because she's not a human. She's no longer a part of society, with all the freedom that entails. An entirely negative freedom, of course. She doesn't have to do anything and thus there's nothing for her to do, besides play games with Kaiki and drink the alcohol she could only sneak sips of behind her dad’s back at home.

She’s happy, but does that matter?

Kaiki doesn’t think so. The other parallel established in the ending is between Nadeko and Hitagi. Compared to Nadeko as someone who never throws anything away, Hitagi is someone who rejects unnecessary things, rejects convenient narratives of victimisation, rejects divine assistance.

Nadeko is broken, thinks Kaiki. Like Hitagi’s mother. Like Hitagi almost was. And being broken has a specific meaning for him - it means no longer accurately recognising the value of the things you have. Nadeko overvalues the things that play an important role in her delusions and ignores everything else. In comparison, think back to Hitagi listing out everything she has to Koyomi back in Bakemonogatari. She has so little, but it’s all precious to her. Not only that, but she manages to offer it to another person. It’s only in recognising the value of herself and also someone else that they can form a mutually beneficial ‘exchange’, a real connection.

In Bakemonogatari, Hitagi’s self is framed as a series of external objects. You are the people around you. In Koimonogatari, Kaiki’s self is found in his money. Endlessly exchangeable, never unique, always mercenary. He offers himself up to Nadeko and gets nothing in return, because she fundamentally doesn’t value what he’s bringing her. Donating to a shrine at New Years’ is a sucker’s game, Kaiki thinks at the beginning of the novel, and he’s proven right enough.

For Kaiki, you could say that the money he spends is spent on himself, on presenting a certain image of himself. So what of the money he takes from others?

He accepts Hitagi’s woefully low payment for the job. He accepts it as a job, because if it’s not a job he’d have to start thinking about what his relationship to her is, if not client and employer. It would become unique, no longer exchangeable for any of the other half-dozen scams he’s running.

He accepts Izuko’s 3 million severance fee. He accepts it and goes on working. It’s unlike him, Yotsugi says. He’s contradicting himself. The money isn’t being exchanged for anything, he’s just taking it. But isn’t that the job of a scammer? To get as much money for as little effort as possible? Then why does he keep doing the job?

He’s acting unlike himself. Throughout the novel, he’s constantly pointing out new sides of himself. Phrases he’s said for the first time. Actions he’s never done before. After a certain point, I have to conclude he’s lying. Kaiki acts unlike himself in Koimonogatari because acting unlike himself, unlike the persona he deliberately acts as, is one of his most characteristic actions.

Being a specialist is about balance - or at least so we would assume from the actions of Oshino Meme. It’s about give-and-take. But Kaiki is a fake specialist, a conman. He should only want to take. It’s not a coincidence, then, that he keeps giving.

I understood it on an intellectual level, but now I get it. I really fucking get it. He’s just, so, Araragi Koyomi. He’s so thoughtless and impulsive, so concerned with appearances, enamoured with his own edginess, stubborn, self-deprecating, cowardly, dense, inconsiderate, self-sacrificing, willful, proud of outsmarting children, reluctant to commit to anything, and most of all half-assed.

That is the characteristic trait of Araragi Koyomi as I understand it. He’s trapped between worlds, vampire and human, but doesn’t seem particularly inclined to choose one or the other. He doesn’t just look to the future, but the past too. In reaching towards what he wants, he’s immensely reluctant to give up what he already has.

All the way back in Nekomonogatari Kuro, he characterises Hitagi and Suruga as different to him, more forward-looking, prefiguring Kaiki’s comments about Hitagi as someone willing to throw aside the most important things to her to get what she wants.

It’s funny, because in doing so he also talks about Tsubasa as someone who’s the same, who also looks for solace in the past. Tsubasa, who in Nekomonogatari Shiro we come to understand will casually cast aside the past if it doesn’t suit her.

She has a different perspective, you see. She thinks Koyomi is different from her. He’s ‘unshakable’, in her words, not concerned about losing his identity. Precisely because he keeps looking back, because he keeps confronting his past, he’s able to accept all of himself, unlike her.

Despite Monogatari being a series about people changing, several times characters espouse the idea that you can’t change, not really.

The thing is that while change is obviously possible, what this idea cautions against is ignoring and forgetting about what you used to be like. Tsubasa can’t just make a new version of herself whenever things start getting difficult, she has to understand herself as a continuous person composed of everyone she’s ever been.

The Rainy Devil teaches Suruga something similar, as regardless of the kind of person she wishes to become, the arm can’t fundamentally transform her. It simply shows that she was already the kind of person who could learn to run fast, already the kind of person who wanted to brutalize Hitagi’s new boyfriend. Koyomi’s idea that she’s somehow more forward-looking than him seems laughable when she feels as though Hitagi and her issues are something that she ran away from.

It’s a fundamentally half-assed application of Numachi Rouka’s methods - for running away from your problems to work you have to remain detached, and the devil’s grasping arm is evidence both of Suruga’s failure in that regard, but also of the attachment to life itself that Rouka lacked. No wonder it felt off when it suddenly disappeared in Hanamonogatari.

At the same time, though, losing the arm is evidence of her change throughout that arc. Her running no longer isolates her, but instead can be seen as a way to connect with others. It’s no coincidence that’s how she ends up meeting Koyomi near the end. It’s his advice that gives her the confidence to get over the finish line, but the first step is abandoning everything and just running - not trying to beat anyone, not trying to hold back, with no particular goal or attachment to a wish. It’s the first time she really can since she started using the monkey’s paw.

Notably it’s Kaiki that offered her an alternative and advised her to just let Rouka have the parts. Kaiki, the one who seemed to be collecting them himself. Isn’t the concept of him possessing what is in a very real sense the remains of Gaen Tooe so fascinating? But it’s the yet-living Suruga that he calls her legacy. It’s hard to say if meeting her, in some way, helped him move on.

Once again, we see a difference from Koyomi, who advises Suruga to act like herself and do what she wants. Kaiki tells Suruga to do what’s easy, what would cause less difficulties for her, in a similar way that he seems to understand Nadeko is much happier as a god and Hitagi wouldn’t have to confront her memories of her mother as long as she remains weightless.

By regaining her weight and her emotions, nothing will change, Oshino cautions Hitagi. She won’t suddenly make up with her mother. But it does allow her to move forward, to value her memories correctly, not allow her missing weight to weigh on her so much that she will never be able to become close to anyone else.

“She’s different now, more so than if she were a different person” Kaiki says, and it’s so easy to read him as relieved that she’s not stuck as she was when he fucked her up. That she’s still always in the moment where she truly fell in love for the first time. That she was able to remain the same person while still loving someone else.

Tsubasa’s immense righteousness is subverted in Nekomonogatari, Suruga’s seeming single-mindedness is deconstructed in Hanamonogatari, and despite the effusive words of praise they both have for Koyomi Araragi it’s evident from his internal narration that he’s more pathetic and wavering than anyone else - and perhaps that’s how one ought to be, here. Never able to make a decision on what’s most important. Always most invested in whatever you’re doing right now, whatever person is right in front of you.

Hitagi is a character that we never see from the first person. Koyomi’s view of her as a titan striding headlong towards her goals is never really contradicted in the story, because despite her immensely evident vulnerability, she’s shown as making a more active effort to move on than anyone.

The shadow of her past relationship with Kaiki hangs over Koimonogatari like a specter.

In Nisemonogatari it’s mentioned that her animus towards Kaiki probably comes from the fact she wasn’t able to hate him in the past. While she was still under the influence of the crab, her emotions regarding her mother were dampened. Kaiki’s acts of splitting her family up likely wasn’t something she was capable of expressing her resentment for at the time.

If you think of that hatred as a final remaining regret, her kidnapping of Koyomi and confronting of Kaiki in Nisemonogatari the expression of such, then it makes sense that Nisemonogatari also marks the start of her mellowing out, never again reaching the heights of violence she demonstrates at the beginning of that novel.

An interesting thing about Kaiki’s role there, looking back, is that he’s clearly aiming for that outcome. As soon as Hitagi confronts him, he leaves. He tells her to stop worrying about the past, about the fact that she once had a relationship with him, because he’s thoroughly uninterested in her as she is now. He provokes her into affirming her current self and relationship with Koyomi. And he says that the man who tried to violate her died in a car accident.

Is he lying? Is it just a coincidence, that he goes with the same manner of death as Gaen Tooe, the same line he feeds to Sengoku Nadeko?

Either way, the purpose of the line becomes a little clearer. He’s trying to get her, both of them, to move on. To understand that the people who seemed so important to you are mundane, the events that shaped your lives don’t mean anything in the big picture, and your past is just that. It’s over. It’s the end.

He almost embodies the concept, in Koimonogatari. We see from his perspective and he is indeed far less ominous, far less portentous, far less important, than he seems from the third person.

He’s also really bad at it. Despite his exhortations to ignore the past, he himself clearly still cares a lot about Hitagi. She as well can’t quite avoid falling back into old patterns of banter, admiration, reliance.

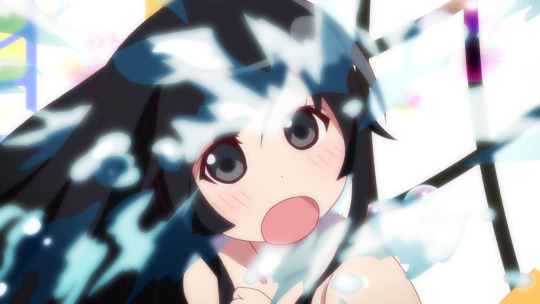

And his ideology isn’t enough for Nadeko. He can’t just deny what she’s clinging onto now, he needs to give her something new. They called Osamu Tezuka a God, she says, hesitantly forming a bridge between her current self and the future she wants to inhabit. Telling herself a convenient story that patches it all up.

It results in an oddly ambiguous message. Nisio loves his tricks, revealing something the narrator was mistaken about at the very end, but when Hitagi says she never loved him and hangs up it’s hard to tell which one of them came out ahead in that little back and forth. Maybe Kaiki, the eternal washout, was so enamoured of his own unique subjectivity he never considered the schoolgirl he was scamming wasn’t so enamoured of him.

Who am I kidding, it doesn’t feel that way at all. Her rejection of the idea that she ever liked him was unconvincing in Nisemonogatari and it’s unconvincing here. And the novel frankly endorses that wilful self-denial. Perhaps it’s important to always act like you’ve fallen in love for the first time. Perhaps it’s important to believe that you’ll never break up with your boyfriend.

In this seeming endorsement of Kaiki’s ideology, I have to wonder what kind of End Hitagi is even fighting against.

Nadeko asserts that a single failure is the End, it’s Nadekover, she has no choice but to kill everyone and then herself. In resisting her, Hitagi asserts her right to change, to move on, to love Koyomi even after her life was destroyed by Kaiki.

On the other hand, Kaiki asserts that failure means nothing, he doesn’t care about anything that has ever happened, after this he’ll just move on and start another moneymaking scheme, same as the last. Hitagi also resists this. She must, if she is to believe her relationship with Koyomi matters in the first place. Her denial that she ever liked Kaiki ends up an odd sort of validation for their relationship. If she did crush on him, that would be important to her, therefore it didn’t happen.

It perfectly mirrors Kaiki’s refusal to admit he ever cared about her. It puts the lie to his whole persona, but, like, it’s supposed to be a lie anyway, I think. They’re both lying to each other and themselves all the time, so much so that they fail to understand even the most straightforward exchanges between them. It’s fine, honestly. They don’t need to be true to each other as long as they’re true to themselves.

One thing that I never really mentioned is the other way you could take this arc title. Hitagi End as in the end of Second Season - the end of the series as a whole, potentially, if you take Nisio’s afterwords seriously (he doesn’t, as evidenced by the several previous times he’s pulled this exact gag).

Astute fans of the anime airing watch order will note that placing Hanamonogatari, an arc set well in the future, before this one robs it a little of that sense of finality. Nadeko is not so much of a threat, knowing our protagonists survive. This is of course the twist, the lie, the joke of this arc. Life goes on, almost interminably so. The idea that graduation would be the End for Hitagi and Koyomi is as ridiculous as the idea that making some mistakes at fourteen would be the End of Nadeko.

Even Kaiki’s attempt to escape the narrative, put a pin in the whole thing by killing himself off, is neatly and instantly subverted by remembering his presence in Hana. It’s not supposed to be a reveal, exactly, that this man is a liar. It’s just there, from the first page to the last.

After Ononoki cautions Kaiki that he’s acting unlike himself, before he goes to talk to Nadeko for the final time, she spends a bit of time telling him what Kagenui’s been up to. Sounded like she was the same as ever, he thinks. I think of this, amongst all his attempts to dramatize his own life, differentiate himself from himself, craft his own ending. His life keeps going on, and Kagenui’s still marching to the beat of her own drum, same as ever.

Happy New Year!

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiii your recent monogatariposting reminded me I have some figures and thought you might appreciate them. Tbh the shinobu is my favorite

im sorry for not replying for so long, these are rlly great tho. i want an ougi fig some day, a kaiki would nice too...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

assuming the scott pilgrim monogatariposting is because they're both works about 'guys' who need to be forcefemmed not because it would fix them but because it would make whatever's wrong with them hotter

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

meme: if two guys were on the moon...

araragi: what about it

meme: oh, I was just thinking.

[hard cut to later in the day, meme now laying awkwardly in a completely different chair, but araragi remains unmoved]

meme: hm... if two guys were on the moon, they'd be astronauts, wouldn't they?

araragi: I suppose so. they'd have a kinship, wouldn't they?

[shot from outside the building]

meme: wouldn't it be unforgivable if one killed the other with a rock?

[shot returns to inside the building, the camera is now inexplicably focused on meme's hands as they fold across his lap]

araragi: of course.

meme: I don't think so, but maybe you could have a point. it's not easy to be an astronaut, after all. sometimes you have to make split decisions like that. can we be so quick to judge one for sins that might not be their fault? maybe we can...

[cut to power lines]

[cut to the moments before a bird is hit by a car]

[title card]

642 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nadeko Medusa - An Analysis

Otorimonogatari begins in media res, with the emphasis on the inevitability of this ending solidifying it as a kind of tragedy. Why am I here, Nadeko asks. Why me? Why was this so inevitable?

What did the rest of the cast do that allowed for their problems to be solved, that allowed for Koyomi to help them instead of becoming enemies?

In truth we’re well off the rails - Nadeko doesn’t even have the typical specialist appearance that so consistently helps in every other arc. The one that unravels the mysteries is the serpent, Kuchinawa, who turns out to be none other than Nadeko herself.

In other words the specialist role is filled by Nadeko, the protagonist role is filled by Nadeko, the victim role is filled by Nadeko, even the oddity afflicting her - all Nadeko. It’s an entirely solipsistic, fabricated story.

As a result, Koyomi’s involvement becomes singularly unhelpful. I don’t know if people really do just go ahead and save themselves, but at the very least they have to try to let others save them. There’s a particular poison about Nadeko that makes Koyomi’s usual modus operandi, seen from the outside, particularly useless. We see in his interactions with her throughout the arc that he suspects she is the victim of an oddity despite her denials - Nadeko thinks she is lying to him, but Koyomi’s guesses are already completely off from the perspective of Nadeko herself being the snake. He doesn’t think of her as someone capable of manipulating and deceiving, as someone capable of being the instigator of her own incident.

Koyomi’s partial immortality is a representation of his self-sacrificing nature, him lowering his ‘intensity as a human’ in order to better approach others. But the more he lowers his guard around Nadeko the worse it gets, her poison stopping him from healing.

Poison is a topic that comes up in the previous arc, the motto of Gaen Tooe, Kanbaru Suruga’s mother. “If you can’t be medicine, then be poison, otherwise you’re just plain old water.” What she means by poison is also ambiguous. It does bring to mind the antagonist of that arc (if you can even call her that) Numachi Rouka. Rouka, a girl that Koyomi couldn’t save, couldn’t even meet. Nadeko and Rouka have one main similarity - a tendency to run away from their problems & avoid getting to know other people.

When something is asked of her Nadeko’s typical response is to do nothing, neither refuse or accept but simply wait until they give up, papering the interaction over with various ‘sorry’s or ‘anyway’s to avoid addressing the main topic. Nadeko is barely aware of what she herself is doing throughout much of the arc, avoiding thinking about the problems instead of doing anything to address them - like asking for help. After she snaps in the classroom, she leaves - after eating the talisman in Koyomi’s house, she runs away - no destination in mind besides getting away from the questions and expectations placed on her by society.

Nadeko’s depression and anxiety, just like Rouka before her, alienate her from life itself - embracing inhuman death in the form of becoming an oddity.

One of the things about oddities is that they don’t appear to ordinary people. Hachikuji calls it the ‘backstage’ in Nisemonogatari. They’re cut off from the ordinary operations of the world itself, only visible to those with supernatural connections or their own chosen victims.

And Nadeko, by the end of Otorimonogatari, is quite firmly an oddity, a creature that can’t be approached for no reason.

Koyomi saw the Lost Cow because he was lost. In encountering the Curse Cat he was, in fact, cursed. He has no business with the god of a dead shrine. No doors to unlock, no prayers to grant, no story to tell.

The narrative no longer sees him as trying to help a friend, but rather trying to forcibly involve himself with an oddity, in the same way as he wrestled the jagirinawa in Nadeko Snake. Don’t mistake the person you’re trying to save, Suruga tells him then. Nadeko is no longer the person he’s trying to save, now.

This leads me to believe the point where it’s officially Nadekover is when she takes the talisman, fuses with Kuchinawa, loses her last reason to be attached to the narrative of herself as a human. The framing of the novel presents it as an inevitable ending because it’s narrated from the perspective of a Nadeko who’s already reached that ending. For her, looking back, there’s no changing the sequence of events that led her there. The idea that everything happening to her is inevitable and beyond her control is a neat excuse for her, but it’s not true.

Okay, but seriously, how did we get here?

Nadeko constantly interprets events in a way that makes her feel guilty, like she did something wrong. Her fundamental view of the world revolves around “victimisers and victims” (i.e. people who hurt others and people who are hurt).

She would rather see herself as a bystander, as someone who doesn’t interact with others in either way. She finds the idea of human interaction, human touch, to be uncomfortable. However, people tend to see her as a victim, leading to an increasing worry about having a victim complex, thinking of it as ‘tricking’ others into seeing her as a victim, which becomes, in the extreme, victimising them in itself.

She dissociates as a coping mechanism, seeing what she does and what is done to her as if it was happening to someone else. “Nadeko” did it, not her. “Nadeko” is how other people see her. An important part of Nadeko’s image is her bangs, which help craft an image of her in others’ minds, by obscuring her eyes and how she truly feels. This serves a kind of contradictory purpose, as while it’s implied Nadeko chose the bangs to deflect from her cuteness (even wearing baggy and unfeminine clothing as much as possible to avoid emphasising her cuteness) the bangs still result in people seeing her as cute. They can’t see the real her, and substitute their own assumptions onto her.

While this has some upsides for Nadeko, as it allows her to retain a blameless image, it also results in a lack of an identity. Nadeko knows who “Nadeko” is, but not who she is. She doesn’t truly identify with any of the things she does, so they’re attributed to “Nadeko”, not her. When others compliment her for being cute, she doesn’t feel as though she is being complimented. She doesn’t feel cute. She feels like she’s tricking people into thinking she’s cute. This constructed Nadeko allows her to feel like a bystander, the very thing she desires to soothe her guilt, but the more she feels as though she’s deliberately constructing it the more guilt she feels over the ‘deception’.

Tsukihi is a kind of anti-Nadeko. Someone motivated with a strong sense of identity. Someone who’s direct to a fault and uncomplicatedly happy when people find her cute. Someone who doesn’t ascribe to Nadeko’s victimiser/victim dichotomy, because she believes in a third role, the hero. Someone who can touch others without making them uncomfortable, put in effort that doesn’t just help themself.

Nadeko fears and loves her in equal measure. Fears her, because her attention is one of the few things capable of breaking through Nadeko’s shield of indifference. Loves her, because she’s exactly the kind of person Nadeko wants to be but thinks she never could.

Trying to deal with Tsukihi reveals some of the contradictions inherent to Nadeko’s attitude. She acts passively, in a way that encourages people to be sympathetic, but then professes to be upset by getting that sympathy. Tsukihi, on the other hand, gives Nadeko just as much sympathy as she thinks Nadeko deserves, and Nadeko craves more nonetheless. In some ways she does still want to ‘look cute’ to others and relies on the acceptance that comes along with it. She’s stuck in a weird Catch-22 where she cant get closer to or further away from other people without resenting herself even more.

It’s suggested that Nadeko’s crush on Koyomi is originally sourced from Tsukihi. It makes sense that Nadeko would pick Koyomi as a more conventional target for her affections, thinking the closest she could get to Tsukihi was a kind of sister-in-law relationship.

Koyomi is someone that she supposedly feels love for, but is that coming from “Nadeko” or herself? The problem is that it’s not love exactly, it’s just another kind of shield that performs a similar role to her bangs. It gives her an excuse for why she isn’t interested in romance. It allows her to present as ‘normal’ to others, but of course that perception of normality belongs to “Nadeko”, not to her. Even Koyomi himself can’t get through to her. She doesn’t want him to understand her, to break down the barriers between them, she wants to keep him away with the bangs, to look cute to him just as she does to everyone else. She doesn’t actually want Koyomi, she just wants to remain in a constant state of wanting him, an unobtainable dream.

Cracks start emerging because of Hitagi’s presence, and that’s what has Nadeko praying for divine intervention. Hitagi makes the story of her loving Koyomi more trouble than it’s worth. It introduces jealousy, the business of dealing with his lovers. The real way to keep it stable isn’t even to kill Hitagi, it’s to kill him, affix him in the heavens as an unchanging star that will never grow any further or any closer.

It’s tempting to see this particular purpose as the reason why Kuchinawa, as an oddity, descends upon Nadeko. But Nadeko herself doesn’t want to think about it. It’s not like Tsubasa, who after casting away her memories & emotions is genuinely unaware of them. Nadeko feels guilty about her curses towards Hitagi, wants to look cute by not mentioning them. The role that Kuchinawa fills isn’t to get Nadeko on a beeline to the talisman - he works much more indirectly.

First, and most obviously, Kuchinawa is a bully. He speaks rudely and directly where Nadeko is quiet and demure. This isn’t a shift in alignment, Kuchinawa isn’t ‘bad girl’ Nadeko - he just says what she’s been thinking this whole time and doesn’t want to admit to. His comments when he goes into school with her all question the ‘point’ of what she’s doing. From one view it’s an ancient god questioning new concepts, from another it’s Nadeko finally allowing herself to question things that she’s had to quietly accept this whole time. The intrusive thoughts stop her from concentrating and eventually lead to her snapping and fully channeling Kuchinawa to talk to the rest of the class. Again, while we could see this as Kuchinawa’s “influence”, it makes much more sense that Nadeko herself can no longer hold her feelings back.

After all, another role that Kuchinawa’s directness performs is allowing Nadeko to poke at her own insecurities and contradictions. Kuchinawa is the voice in her head pointing out all the things that Nadeko has done wrong, ensuring the sources of her guilt are never far from her mind. There’s an odd kind of comfort to it, though - unlike the criticisms of other people, Kuchinawa never expects anything from her in response. He is amused by Nadeko’s deceptions, not resentful. He sees everyone in the world as a victimiser, as a liar. Everyone lives while deceiving themselves and others. It’s only natural. Therefore there’s nothing Nadeko can do about it. No way of her remaining a bystander.

Ultimately what I think Kuchinawa represents is Nadeko’s creative impulse turned towards escapism. He allows her to construct a story, present her life in a way she can accept, participate in a narrative she chooses. Her love for Koyomi is a story she’s been telling for a while, one that allows her to paper over the cracks in her life and give her the strength to continue. Now cracks start emerging in that story, and to paper them over she reaches for a paper-thin talisman.

The question arises of why Kuchinawa (why Nadeko) even needed it in the first place. Clearly it plays a role in feeding Nadeko’s fantasies, granting Kuchinawa the supernatural power he needs to become real. But despite being billed as capable of granting any wish, it can’t actually make the story of her love for Koyomi real. It can’t make him love her. Because she doesn’t want him to in the first place.

No, the talisman’s powers are limited. It can’t truly turn back time, or erase her mistakes at school, because she doesn’t believe her actions could ever be changed. It’s been over from the start, Nadeko says. There’s only one way it could ever end for her, only one type of person she could ever be, only one choice she could ever make.

Every other Monogatari character has had multiple choices. Take Koyomi, who was prompted to kill the monster entirely, and instead made it one with him. Suruga, who was encouraged by Rouka to leave her alone and just live a normal life, and instead came back to play a final game. Tsubasa could have just let the oddities in her mind go burn off her stress and pretend it had nothing to do with her, but instead decided to let them back inside.

Let alone two options, though, Nadeko fails to see even one. What she ends up pursuing is neither of the two options, but instead the bad end, as if Koyomi had remained a vampire with Kiss-Shot.

She refuses to face reality. That’s what Tsukihi says - “telling someone to dream is like telling them to face reality.” It feels a bit contradictory but it fits into a theme that’s been consistent over the last few arcs. Seeing a dream is like having an end goal to work towards. Ougi says in Mayoi Jiangshi that it’s better to not achieve your dreams, because they’ll be inevitably disappointing. Koyomi says in Suruga Devil that wishing for something in itself is fine, it’s a destructive focus on the end result that’s the issue with the Monkey’s Paw. Tsukihi says she would support Nadeko if she was really trying to date Koyomi, but she’s not. She can’t face the reality of Koyomi having a girlfriend, of Koyomi being out of reach for her. What she’s doing is acting as though she’s in a different reality where that’s not true.

It’s a fitting followup that when Nadeko snaps, acting her most Tsukihi-like, it’s to tell the rest of her class to face reality. As a result of Kaiki’s charms the class has started acting, in her words, “just like Nadeko”. Because lots of people’s secret feelings about each other were revealed, they no longer trust each other, assuming everyone around them are trying to trick each other, trying to act cute, to the point where they’ve given up on trying to make close relationships. Given up on the year, the class, entirely. Because they think they have no choice.

Nadeko tells them to face reality, to accept that the world and the people around you aren’t as pretty as the stories we tell about them. To pursue a dream where everyone makes up in the end. To ‘rewrite’ the memory of that class with their own effort. It’s a vision of a Nadeko who does try to address her issues, as embodied by the class and the effects of Kaiki’s talismans. It’s what Otorimonogatari really should have been about, if Nadeko didn’t go ahead and make up another story on her own. A fantastical decoy of a story that has her running out of the classroom and never seeing the result of her efforts.

Kaiki’s talismans, if we remember, were fake, their effects not genuinely manifested for anyone but Nadeko, who bought into the story, went as far as to research her own methods of breaking the curse, and ended up making it worse. It’s not as if she was at fault for what happened, it’s not as if she did it on purpose, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that it happened according to her desires. It let her reconnect with Koyomi, didn’t it?

Nadeko is the type of person who can take something false and through her creative impulse, chuunibyou, escapist fantasies, whatever you want to call it, make it into reality. It’s just that she’s unconsciously biased in a destructive direction, one that results in either her being hurt or her hurting others.

This culminates in her consuming the talisman and becoming a god. The story she’s actually trying to make real isn’t the world where she’s an eternal victim, Koyomi constantly looking out for her. It’s the story where she’s an eternal victimizer, a serpent god with sharp fangs.

Due to her new heat vision, her hair isn’t an inconvenience to her any longer, just to others. It pushes them away actively instead of just concealing her. You could say the hundreds of snakes move independently of her will, but in another view they are her will itself, animal instinct embodied. They’re only uncontrollable in the sense that she can’t control her own violent impulses. It’s easier for her to get rid of people than deal with them directly, and this confirms her view of herself as fundamentally selfish. She can’t be like Tsukihi.

In a complete inversion from the ethos she espouses to her class, Nadeko says she’s someone who likes people only if they’re kind to her, and can’t like anyone who dislikes her. It’s a story where in becoming an oddity she no longer has to deal directly with the human world, no longer has to be concerned with what’s going on with her classroom or her parents.

But that, she says, is “Nadeko”, not me. At the end of it all what she’s doing is still a performance for the benefit of others. She still can’t tell what she really wants, really is. She still gets by with the excuse that she’s a bystander and there’s someone else doing all that stuff. The phone call at the end makes her dissociation clear, I think. If she really wanted to kill Hitagi and Koyomi and Shinobu, would something so simple really stop her? If she actually hated and was jealous of Hitagi, would she calmly listen to her? Does she really have to thank her for her advice? The way she reminds herself that people who are kind to Nadeko are good people sounds like she’s trying to convince herself.

Becoming the serpent god is in line with how Nadeko sees herself, but it’s not what she actually wants. She doesn’t really want an “I”, she tells Kuchinawa as they discuss her lack of self. She just can’t bear existing without one. She says it from the start of the book. She doesn't actually want to defeat Koyomi and reign victorious over the shrine. Nadeko’s way out of this whole mess was for him to kill her.

I get it, Nadeko, I really do. Living is just so tiring, after all.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yotsugi Doll - An Analysis

We begin our march into the Final Season with an arc that feels both inscrutable and incredibly straightforward at the same time. Take the name, for example - typically the titular oddity is the one affecting our arc character, but in this case Yotsugi herself is the doll.

In terms of comparable naming conventions, I would bring up Tsukihi Phoenix and Mayoi Snail - both characters implicated in this arc, one by her presence and the other by her very notable lack thereof.

Hachikuji Mayoi is not the one afflicted by an oddity, I wrote back near the start of this project, but I think recently it’s become evident that this isn’t quite true. She was afflicted by the Snail - the role of the Snail that she was forced to play.

Looking at it that way there’s a question of how voluntary Yotsugi’s dollness, her emotionlessness, her lack of personality and ease of influence by others is meant to be. We know that she doesn’t actually lack emotions, she’s just incapable of expressing them, which is an important distinction. At the same time, she’s empty enough to fill and be filled by the roles of others, as a specialist’s shikigami & supernatural proxy.

Tsukihi is a character in a similar boat, so far as the core of her nature lacks stability and seeks it out from others. Is she, too, afflicted by the phoenix? She certainly doesn’t embrace the role of an oddity, unless we’re to say that her role is acting exactly like a human. Instead, she takes up the role of an Araragi, a Fire Sister, and in her deliberate attempt to become one etc etc we all know the quote.

That being said, there’s a question of how her life is impacted by the phoenix. Koyomi is certainly worried, in this book. In the scene where they get in the bath together her extremely short-term thinking is demonstrated in numerous ways as she fails to conserve conditioner, easily forgets what she was talking about upon being splashed with water, and of course proceeds with the whole plan heedless of the consequences of Karen’s inevitable return.

Tsukihi is stuck in the present, neither looking back to the past or looking forward to the future, and there’s no better representation of such than her frequent hairstyle changes. It’s the regenerative power of the phoenix that lets it grow so easily, allowing her to ignore consequences and return to the same, default state.

Koyomi is the opposite, his hair growth also evidence of his vampiric abilities, but in the sense that he keeps it long to hide the marks on his neck. He puts off cutting it over and over again, saying he’ll do it ‘after exams’. We might say that in opposition to Tsukihi his hair is evidence of him being stuck in the past, unwilling or unable to move on from the effects of his vampirism.

Both of them, though, need to move into the future, Koyomi thinks. But by the end of the bath scene, we’re getting the sense that Tsukihi already is. She hasn’t cut her hair in a while, she says, because she has a ‘wish’ she wants granted.

If Tsukihi is capable of developing as a person even despite the nature of the phoenix, then we might question whether Yotsugi is not also capable of change, becoming more human-like.

But is that true? Right at the beginning of the story, we’re treated to Shinobu and Koyomi discussing Yotsugi’s position. Shinobu says that while Yotsugi is an oddity, she’s an oddity whose role is imitating humans. Not to be or become one, Shinobu clarifies, but to be with them, to blend in alongside them. In that sense, she exists the way she does for the benefit of humans. She was created by them, serves as their shikigami, and acts similarly enough to them that you could almost believe she was one. She just isn’t quite there, her convenience located in the fact that you don’t actually have to treat her in the same way you’d treat a person, when it comes down to it.

This convenience, this privileging of the human perspective, is fundamental to oddities in general. They exist in the forms that they do because those forms are the most sensical to humans. The animals they draw their appearance from, the puns that make up their names, their sources in old myth - all are symbols that allow people to observe them, speak of them, and tell stories of them.

After all, in a sense they cannot exist without these stories. Koyomi, who has been telling them all this time, knows this better than anyone. The oddities are found in the gaps between reality and his narration. I don’t say that to suggest there’s some objective reality where they don’t exist, though. How could there be any objective version of the narrative when the whole series is fictional?

Regardless, in-universe there’s a shared common sense where oddities don’t exist and all the events of the story have a reasonable (or simply unknown) explanation. Koyomi and his friends have their narratives coloured by a different perspective, and the series takes care to not present this as them uncovering some kind of concealed truth, but merely stepping ‘backstage’ and looking at things in a different way.

A deeply human way, perhaps. The temptation to see animals, inanimate objects (and of course, especially, dolls) as possessing feelings or intentions is extremely common. An oddity, Shinobu says, is a ‘deep attachment’, a strong feeling, and I can’t help but think of Nadeko here, whose attachment to Kaiki’s charms was so deep that to her they became a snake constricting her entire body.

Her knee-jerk rejection of others’ affection, the shame of being perceived, the inability to speak up about her pain, these feelings coalesced into a form, a name, a word that made sense to her. She tells herself a story about snakes, so later, when she can no longer maintain a pretense of loving Koyomi, what form would her hatred towards both herself and the world take but a white snake hiding in her shoebox? She tells herself a story about snakes because it’s more convenient for her, makes things a little easier to bear if it’s not her fault.

Hitagi’s attachment is to her mother, and she conceptualises it as a weight around her neck, so of course when she casts it aside it suits her purposes to tell a story where it was taken away from her by someone else.

Mayoi’s attachment is to life itself, and as a young child from a broken home, of course she conceptualises it as something she’s only allowed to have if permitted by an authority figure, so she makes it a plausible excuse. She’s just going to her mother’s house. She’ll be back as soon as she’s done.

Suruga’s attached to her own attachments, things she could have been good at if she tried, things she could have had if she tried, people she could have saved if she just tried. She conceptualises them as still attached to her, a reminder that everything’s her fault, for wishing or not wishing or not wishing enough.

Tsubasa, despite everything, remained attached to herself, to her own identity and ability to lead a normal life. She conceptualises herself as a cat and as a tiger, and it’s only by telling their stories that she’s finally able to tell her own.

Koyomi was so thoroughly unattached to anything that he told the story of his own death. He no longer wanted to be a human, no longer felt like one, and he conceptualised that as a being with sharp fangs and a thirst for blood. Then he saw that being, really saw it for the first time, and in all his infinite selfishness decided he’d rather that she was human. He was attached to Shinobu, so he told a story where she was small and moe and a big fan of doughnuts. And she was attached to him, so she told a story where-

I’m getting a bit ahead of myself.

Ononoki Yotsugi was born without memories of her past life. Zero attachments. So people are free to attach whatever they want to her. She’s a bit like a lego piece. Hell, her limbs are even detachable. Rearrange them as you like. Turn her upside down and check what colour her panties are. She exists entirely for your convenience.

Yotsugi is a difficult character, for me, because I still don’t really know what she wants, how she feels, why she’s attached to the people she is. This arc doesn’t get into it much, either. Yotsugi’s dollness isn’t explored as a personal struggle. Rather, I think the question being asked is how different from her the other characters really are.

If Yotsugi is forced into the role of a doll then the whole cast of this tale is in a similar boat, ‘finagling [their] way through life’ as she puts it, trying to be ‘right and proper’ at their assigned role.

That being said, what it means for an oddity like Mayoi to be ‘right and proper’ (according to the darkness, according to Ougi) is made evident enough, but what exactly are the roles of the characters in this “Possession Tale”, and how do they differ from them in reality?

Tadatsuru is easily the most confusing here, a character we’re first introduced to here, who (we’re told) seems to materialise just as he’s needed by the plot. I, myself, don’t quite see the need for him, the thing that makes him a perfect opponent for Koyomi, apart from in the fairly shallow sense that his being a specialist confronts Koyomi with his newfound vampiric condition.

Ironically, despite appearing as an antagonist, Tadatsuru does actually provide some clarity on the situation in exactly the way you might expect from a specialist. Koyomi’s vampire problem is only the first layer of the mystery here. The second layer, and one that won’t be fully peeled off until much later, is the fact that these events were orchestrated in their entirety.

I suppose in that sense he also highlights how many of the people precious to Koyomi are oddities, or oddity-adjacent. Perhaps, building from Kagenui’s assault on Tsukihi in Nise, we’re supposed to consider whether Koyomi is really in the right for protecting these people. That’s kind of nonsensical though, we already know he’s right, and in any case Tadatsuru isn’t particularly invested in morality in the same way Koyomi is.

He has, we’re told, no ‘ideology’, but rather ‘enmity’ and an ‘aesthetic sense’, an appreciation for the beauty of undead abominations that leads to him working in a related trade, much like how an artist might work as a collector or curator. Who exactly he holds ‘enmity’ towards, then, is left rather vague, but to imagine it for a second, we might talk about someone like Koyomi, who’s at once both dead and alive. Who’s almost in the opposite trade to Tadatsuru, with how often we see him humanizing (‘twisting’, as Ougi puts it) immortal oddities.

His issue with Koyomi isn’t moralistic, but it could very well be aesthetic, a complaint about how he ruined a vampire by turning her into a little girl, ruined a ghost by making her stick around past her time, ruined a phoenix by letting her believe she was his sister, and maybe even ruined a doll by making her want to be an actual person instead of just a facsimile of one.

If this is his role, he doesn’t embrace it. He lets himself be killed, expressing regret for the changes that have already occurred in Yotsugi rather than trying to keep her the same.

He already lost the fight over her a while ago, it seems.

Kagenui Yozoru is almost as confusing, a character who finally starts to get fleshed out in this book only to invite further questions as to her history and the history of all the specialists. She’s Yotsugi’s sister seemingly by Yotsugi’s choice rather than hers, and it’s that choice which drove a wedge between her and Tadatsuru. We’re told that the difference between them is his focus on the immortal dead, (because he appreciates them aesthetically) while her focus is on the immortal living (because she wants to kill them).

It’s a little difficult to say which ones are which. Tsukihi, at least, is clearly in the alive category, and I’d argue Shinobu and Koyomi are too, but Yotsugi seems more on the side of the dead, which is presumably why Tadatsuru wanted her. On the other hand, if her human-like nature makes her a living oddity, then Kagenui’s conflicted feelings about it become more clear.

If she’s a living immortal, then, much like Tsukihi, it would become part of Kagenui’s justice to destroy her. This might be the ‘lesson ten years in the making’ that she learns in Nisemonogatari, when Koyomi argues to her that a sister who isn’t related to you by birth is still a perfectly valid sister.

We’ve seen a few takes on the role of a specialist now, and they all seem to come back to balancing the books in some way, returning things to their ‘right and proper’ state, even if they differ in interpretation of what that is. Kagenui’s attempts to resolve the contradiction of Tsukihi’s existence by force are mirrored here in her attitude towards Koyomi. You can’t be a human and a vampire. If you keep swapping back and forth I’ll just kill you.

For all that this places her on the side of humanity, it also makes her a singularly inhuman character, at least from Koyomi’s perspective. She rarely varies her tone or expresses emotions, her most violent declarations given the same weight as her pleasantries. It’s reminiscent of how Tsubasa’s human persona is characterised, almost, with the aggressive normalcy, lack of strong preferences, failure to understand those weaker than her. ’The little things that make us human’, Koyomi thinks.

He’s also wrong. She shows sympathy for Koyomi a few times, he just dismisses the possibility out of hand. He only gets it when she finally finishes unravelling Tadatsuru’s paper cranes that she expresses a little closeness to the guy, sounding ‘protective’ of his practice of folding all the cranes by hand. ‘She’s human after all.’

If her role as a specialist is to be an uncompromising wall between Koyomi and inhuman oddities, she’s already failed. She failed in Nise, and she fails now when she encourages Yotsugi’s friendship with Koyomi instead of letting this book end with them splitting apart permanently.

Because that, of course, is the role that Yotsugi was supposed to be cast in, here. Koyomi himself cannot defeat Tadatsuru, because he cannot transform into a vampire. He’s human. Yotsugi, on the other hand, is an oddity. Killing humans isn’t unusual for her. It’s right and proper. What isn’t right and proper is her friendship with Koyomi, his treating her as someone he can treat to icecream instead of a convenient object for disposing of his enemies.

Is that really how it works, though? As Yotsugi points out, there’s nothing particularly ‘right and proper’ about being undead. Her whole existence is thoroughly unnatural. The contradiction of an oddity made in the shape of a human is that she must necessarily stand on both sides. Being able to treat her as a tool of murder would be convenient to Koyomi in one sense, but I think far more convenient for him is her ability to act like she isn’t one. To let him forget the inherent danger of oddities, because in his mind he’d much rather they just be little girls.

This is something he’s gone through before, with Shinobu and with Mayoi, and I suppose I’m starting to see why these three get grouped together so often. I mean, really he puts every girl he meets on a similar pedestal, but these three full-blooded oddities are unique in the amount of direct influence he’s capable of exerting on their nature.

Shinobu is of course the root of it all. Koyomi was punished severely for his initial misapprehension of Kiss-Shot as weak and harmless, but his resolution to the situation made her weak and harmless in reality. In a horrific violation of her agency, Koyomi forced Shinobu to conform to his image. The gravity with which he treats this, though, is precisely the issue - his perception of Shinobu as a victim, his victim, is what leads him to neglect her feelings and their relationship through most of Bakemonogatari. He thinks he has no right to ask anything of her.

We see a similar thing going on with Mayoi, in Kabukimonogatari, as he takes on the mission of ‘saving’ her by removing himself from her life, only questioning whether Mayoi herself prefers her current state at the very end.

There’s a part of Koyomi that wants to see Yotsugi as human, that finds it more convenient, but I think there’s another part that views himself as self-indulgent. That wants to enforce a harsher line between humans and oddities. Not because he despises oddities, but precisely because he finds them too convenient. He doesn’t think he deserves to be able to get along so well with them, deserves to make use of them so easily.

As Ougi puts it, he prefers it when things feel a little bit bad. Subconsciously, it just makes more sense to him that way. The story Koyomi Araragi has been trying to tell, his Bakemonogatari, is one where he suffers for his successes and nothing comes without a price. Where he gets his guts ripped out over and over again in a kind of ritual purification of his sins. One where nobody can help him and nobody can save anyone else, only themselves.

It’s a bit of a breath of fresh air to realise he’s mostly gotten over it, by this point.

He still feels on a subconscious level that he shouldn’t be allowed to get away with all this, that he’s in violation of natural law, that with all his activities lately he’s selfishly exploited his relationship to Shinobu. You know, like some kind of. Undead creature. That drinks blood. Like yeah dude, of course you’re going to get too used to transforming into a vampire if you conceptualise both vampires and yourself, in the act of transforming into one as fundamentally self-serving entities! Oddities are what you make of them!

Nonetheless, he acknowledges Kagenui when she says all of that is just self-satisfaction. He only thinks this way for his own convenience, to put the universe in a kind of order where its repeated assaults on him make logical sense.

Ougi ends up being the one that embodies the universe’s viewpoint, congratulating him on his character development. Haven’t all his failures been learning opportunities? All of his suffering heading towards some noble goal? Now, he has once again been blessed by failure & an advanced warning to get his shit together in the form of his reflection not showing up in the mirror. The message is clear. Stop relying on Shinobu. Don’t be friends with Yotsugi. Oddities will ever betray you. They might be convenient, they might appear when and because they’re called for, to fulfill human desires and meet human expectations, but that doesn’t mean they’ll help.

Koyomi of course says ‘I feel astonishingly unrepentant’ and ‘I would’ve done exactly the same thing’. Bad things happening to you are in fact bad, not good. We’ve been over this already. He starts out as thinking of Shinobu as a victim, but by the end of Bakemonogatari he’s accepted that she actually wants to help him, that accepting help doesn’t make him a bad person. Whether it’s Shinobu or Yotsugi or Mayoi, it’s been clear for a while now that whether they’re human or not has nothing to do with whether he considers them a friend.

I think perhaps I was a bit hasty to assume there’s some kind of dichotomy between humans and oddities going on here. That we have to slot Yotsugi into one or the other, that she’s only worth considering a person if she’s secretly a human.

Bakemonogatari ends with Koyomi reflecting that there is darkness in the world, and things live in that darkness. That darkness lives in him! It’s his shadow! He can’t ignore it, can’t forget it, and he can’t make it go away. That’s just how Shinobu lives, but that doesn’t mean he can’t live alongside her. It doesn’t mean Yotsugi can’t live alongside humans, even if she isn’t going to become one.

It’s a pluralistic view that I appreciate and maybe should have expected from a series marked by characters who consistently choose third paths between either abandoning their humanity or eliminating the inhuman entirely.

Perhaps you’ll allow me to end on some hair-based reflections (or lack thereof). I mentioned how Tsukihi growing out her hair may be evidence of character development on her part, but Koyomi not cutting his was evidence he’s still stuck in the past. The trope of a character development haircut is of course common throughout this series, with Hitagi, Tsubasa, Suruga and Nadeko all showing the changes they’ve undergone through their hairstyle. Karen and Tsukihi are deliberate subversions of this, as they’re shown cutting their hair for no particular reason at all, remaining largely static characters.

Koyomi is one of the few characters that doesn’t cut his hair over subsequent appearances, but I’m not so sure it’s evidence that he doesn’t change at all. The changes just build up so slowly we don’t really notice them, until we’re met with an absolute mop in Hanamonogatari’s peek at the future. It feels like an obvious rejection of the idea that anything about this arc was a wake-up call, the idea that something bad must happen to Koyomi, or to Tsukihi, to allow them to grow in the future.

As always, he makes his way through life kind of half-assedly. He himself, at least, never feels as though he’s gone through significant enough changes to become a different person. But in holding on so tightly to the past, the person that he is now becomes clearly evident.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tsubasa Tiger - An Analysis

This is an arc about personal identity, which is fitting for the first book in the series narrated by someone other than our main character. Tsubasa’s halting attempts to discover herself feel almost in parallel to Nisio’s attempts to expand her internal world beyond that perceived by Koyomi.

It quickly becomes evident that Hanekawa Tsubasa does not know herself, the usual catchphrase of ‘I only know what I know’ recontextualised with the understanding that there are many things she does not know on purpose. This is what Izuko tells her, and note that for all her talk of Tsubasa knowing nothing, the specific facts that she focuses on - the tiger, Tsubasa’s feelings for Koyomi, the cram school burning down - are things that Tsubasa should know about. Izuko doesn’t stun her with information that would be impossible for Tsubasa to obtain, but rather things that it should be impossible for her to not know.

This absence is at the heart of this arc’s central oddity, the titular tiger. It’s rendered variously as the Tyrannical Tiger, Hystery Tiger, History Tiger, etc. I think the most immediately relevant things to draw on when talking about it are how it symbolises both the past and Tsubasa’s strong emotions. However, in her usual fashion, neither of these are immediately obvious in the tiger, which appears out of nowhere, rooted in no history, motivated by no emotion. It is singularly uninterested in these things, and that is precisely why it is useful to her.

Its role is to burn the past. It is powered by her ‘dark’ emotions, but is not itself touched by them. Its habit of arson is found in her envy, the repressed desire for a home of her own leading her to destroy those of others. She also, in a more personal sense, envies the family. Her parents growing closer to one another. Hitagi and her father. The Araragi siblings and their mother.

The reason, then, why she manages to stop herself from destroying their houses as well is because of the genuine intimacy and love that she manages to build with Hitagi and the Fire Sisters (as partially represented by the shower/bath scenes). She never manages to hate Hitagi for ‘taking’ Koyomi from her, because despite loving Koyomi she ends up a little bit in love with Hitagi too.

Over all three of Tsubasa’s arcs we’ve slowly been approaching the truth of the similarity between Koyomi and Tsubasa. The difference between them and Hitagi, or Kanbaru.

Tsubasa is someone that resists change, refuses to move forward. To some extent the backwards chronology of her first two arcs doesn’t matter because the conclusion is almost the same. Just don’t worry about it. Continue as normal. This can seem a frighteningly noble thing, from Koyomi’s perspective. It is a frighteningly broken thing, to Tsubasa.

Hitagi says she’s a ‘failure as a creature’. That she has no sense of danger, simply accepting everything as it comes. The concept of the ‘wild creature’ invoked here is obviously connected to how her oddities manifest as animals, holding the instincts and impulses that she rejects in herself. She eats her food unseasoned, not because she prefers it that way, but because the difference in taste doesn’t matter to her. She approves of goodness to the exact same extent she approves of tediousness, of flavourlessness, of banality. In that sense, Hitagi questions, can even her love for Koyomi be considered real? Does she have a reason to prefer him in particular?

We’ve been told that she’s the ‘real deal’ in comparison to Koyomi’s fake, but what that turns out to mean is simply that Koyomi has a basic level of self-awareness. He knows how it looks to others, to be so self-sacrificing. It makes you stand out. Tsubasa fails to recognise this - how else would she still have the misconception that she’s been correctly acting as a ‘normal girl’?

Besides that one point, the two are remarkably similar. Their lack of self-regard drives them into service of others, all the while stubbornly refusing to reach out for help on their own. Koyomi fails again and again, repeating the same mistakes, accepting his old hypocrisies, and through it all, remaining himself.

That’s why she loves him. Because he ‘confronts his own weakness’. Because when he saved Shinobu he was crying, and Tsubasa can’t remember the last time she herself cried.

The second chapter ends with Tsubasa noting that she always gives thanks after a meal, for the plants and animals that have been killed ‘for my sake, of all creatures.’ Especially after spring break, she says. After encountering a vampire, after witnessing what it is to be a vampire, to devour someone else’s life for your own sake. But here I also think about the cat. An animal that died on the side of the road. A predator, whose energy drain selfishly takes from others.

Just as Koyomi and Tsubasa are alike, so are their oddities. They both take the form of creatures that are capable of imposing on others, of asserting their own desires over those of others, and for that reason the both of them are deathly afraid of letting them out. They shrink back inside themselves, trying their best to avoid bumping into anyone else, to avoid cursing them with their touch.

But where Koyomi, in his fumbling way, makes progress & reconciles with Shinobu, Tsubasa casts her cat aside. She loses the memories of its rampage after it leaves. This doesn’t seem strange at first. We assume this is how the oddity works. It is how it works! For Tsubasa. The cat isn’t the one removing her memories, she just went ahead and did that on her own. Like she does with everything.

There’s a conversation between cat and vampire in this book. Shinobu brings up the tale of Napoleon sleeping in the bath & points out that two very abnormal things can combine to seem normal. Black Hanekawa is one such abnormal thing, an oddity, but going down this train of thought has Hanekawa wondering if she isn’t one herself, if her own ability to ignore inconveniences and tolerate the intolerable isn’t also something ambiguously supernatural.

Episode says that she had an ‘overwhelming presence’ when he met her during spring break, that she almost seems normal now, having since cut off the cat from herself. Having cut off the tiger. It’s almost a contradiction. The more she relies on supernatural powers, the more normal she herself becomes.

Perhaps the model student persona of Hanekawa Tsubasa was also a constructed identity, constructed for the purpose of protecting herself, just as Kuro was.

After all, to a vampire’s eyes, there’s not much of a difference between human and oddity.

Again we have the oddity as a twisted reflection of its master. Shinobu sees everyone equally as food, while to Koyomi both humans and oddities are equally in need of his help. He saves Shinobu despite her monstrous nature, he saves Mayoi despite her being the cause of the incident. To him there’s no distinction, both Kuro and Tsubasa are Hanekawa.

We are going to be seeing nightmares for the rest of our lives, he tells Tsubasa in Neko Kuro. You will never stop being that person. Because when it comes down to it, he doesn’t, and neither does she.

It feels a little off. People can change, can’t they? People can always change. Does she really have to drag that cat, that tiger, around with her forever? In this book we get a more complete picture. What cannot change is the past. What happened, what you’ve done, that never goes away. You can become a different person as much as you like, as long as you never deny it. That the cat, the tiger, they were, are, both you. You can change as much as you like, but all of those changes, steps and missteps are still Hanekawa Tsubasa.

Her mistake was pretending that the cat wasn’t her, pushing everything onto Kuro as though it had nothing to do with Tsubasa herself.

As Gaen points out though, this is normal. Everyone goes through their life lying to themselves & each other to cope. Tsubasa isn’t special. What makes her special in this arc is accepting the oddities as part of herself, asking them to come home. Supposedly they’d disappear on their own. From both an oddity’s perspective, and a human perspective, that’s the preferable outcome. But just like Koyomi, Tsubasa doesn’t see this from an oddity’s perspective, or a human’s perspective. To her the cat and tiger have become family.

The theme of this series, then, really hasn’t changed from the first arc, where a girl without her weight takes back her emotions.

Hitagi and her own self-driven changes are vital to this arc, her affection for Tsubasa driving the girl to accept help freely given. Tsubasa still resists the idea of calling Koyomi, taking up his time, making her feelings known to him, and so both Hitagi and the Fire Sisters end up demonstrating the virtues of kindness freely given, what a family ‘should’ be like. This helps Tsubasa understand the character of her own family situation, one that she finally bluntly articulates as abuse.

Both Tsubasa and Koyomi have that tendency, looking away from uncomfortable truths in order to maintain their way of life. Take, for example, the situation with Kanbaru, where he’s just a bit too charitable, doesn’t quite understand how much she wants him dead. He’s unable to solve the incident on his own, unable to realise the problem with getting himself killed to solve it, and in the end is only able to provide a justification for Hitagi and Kanbaru to meet. To buy time for her to get there.

It’s an overstepping of bounds, a needless intervention, an unwanted favour. But it’s not pointless.

It’s a classic Koyomi-narrated arc, in that way. He’s a bit slow to understand the mind of the ‘victim’, is unsuccessful in his attempts in intervention when compared to Oshino, the specialist, and Kanbaru has to just go ahead and save herself.

Consider, now, the structure of Tsubasa Tiger. For once, our protagonist isn’t Koyomi. And yet, in a similar manner to Koyomi Vamp, we find the narrator herself to be the one afflicted by an oddity.

She’s a bit slow to understand what’s going on in the mind of the victim, has the situation laid out for her by Izuko, the specialist, and in the end -

Her attempts at intervention are unsuccessful. She can’t defeat the tiger on her own. She can only buy time.

Just as Koyomi’s business with Kanbaru is an overstepping of bounds, a needless intervention, an unwanted favour, Tsubasa’s business with the tiger is ‘impossible, reckless and-’

Not futile. Never pointless.

Isn’t the point of Koyomi in Suruga Monkey that without him risking himself, the two may never have come back together? That despite being unwanted, his selflessness is, in the end, appreciated?

The point of Tsubasa Tiger, then, is that people will come to help you if you call them. Koyomi demonstrates this in Nekomonogatari Kuro, with his text message trick. Here, in Shiro, Tsubasa returns the favour, finally reaching out to him by sending a picture, escaping the carefully constructed boundary of her school uniform, letting him know that she wants to stay in touch with him, that she doesn’t mind imposing on his time a little.

One might question the role of Koyomi in this narrative, appearing at the end to save the day. Isn’t this arc supposed to be about Tsubasa? Doesn’t she have to resolve her own issues? Do we not all have to save ourselves?

That was never true, though. Koyomi’s appearance at the end is almost an afterthought. It’s Oshino’s final proposal in Koyomi Vamp. It’s Hitagi’s arrival in Suruga Monkey. It’s Shinobu’s emergence from the shadow in Tsubasa Cat.

The protagonist role Tsubasa inherits from Koyomi is not the ability to solve incidents, it is the ability to help, to be there for someone. Just as Koyomi was able to face her feelings head on in Tsubasa Cat, willing to give up his life for her in Tsubasa Family, just how she was able to be a friend to Koyomi at his lowest point in Kizumonogatari -

For the first time in a while, the one that Tsubasa Hanekawa tries to take care of is herself.