#pseudo taxonomy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ghoul taxonomy:

Domain: Eukanya

Kingdom: Anomalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Daemonium

Family: Daemonion

Genus: Infernide

Species: I. vulgaris

Sub-species: I. vulgaris vocare

Other members of the genus:

I. via lactea

I. via lactea vocare*

I. infirmus

I. primus solaris maior*

I. primus solaris

* - sub-species

Bonus info:

Ghoul mostly refers to members of I. vulgaris, especially domesticated sub-species, called I. vulgaris vecare that are the majority of the ghouls working in the ministry.

I. vulgaris vecare has four main breeds: Fire, water, air and earth.

Multi ghouls usually are used as an umbrella term for ghouls without clear classification, but is mostly a descriptive than a valid scientific term. It can refer to wild members of genus Infernide, most often I. vulgaris or even feral I. vulgaris vecare that are too mixed to have one clear dominant element.

Wild members of the genus lack the clear deviate of the base elements.

Quintessence ghouls however are I. via lactea vocare and lack as diverse breeds as I. vulgaris vecare. Mostly we have quint, nether, aether and void breeds. But they mostly have an diverse aesthetic and magical differences. It's much rarer to summon a purebred one.

All members of genus Infernide can interbreed, with (usually) offsprings with ability to further reproduce. However many ghouls have clear preference towards their species, sometimes even breed due to some species/breeds being not the most compatible for natural breeding.

#pseudo taxonomy#ghoul taxonomy#ghoul bio#ghoul biology#ghost band#ghost bc#the band ghost#ghoul headcanons#ghost the band#shitghosting#feel free to add on!#nameless ghoul#namless ghouls#ghost ghouls#water ghoul#air ghoulette#air ghoul#water ghoulette#earth ghoul#earth ghoulette#fire ghoul#fire ghoulette#ghosting#the band ghost headcanons#the ghost band#nameless ghouls headcanons#nameless ghoulettes

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metazooa Stats

🐁 Animal #88 🐦⬛

I figured it out in 8 guesses!

🟧🟨🟨🟨🟩🟩🟩🟩

🔥 1 | Avg. Guesses: 8

#metazooa

#it was fun#i can pretend i can read the pseudo latin#tho idk of these branches were Latin. bc idk Latin 🥴#joke aside it's fun to see how complex taxonomy is and what are the divisions about#sorry i just woke up bc my digestive system decided to ruin my night and idek why#maybe too much bread

0 notes

Note

D’you perchance have any thoughts on the morphological (for lack of a better word?) dire wolves that Colossal Biosciences just revealed to the public? 👀

Oh my god Aenocyon, you can't just ask someone why they're white!

"Morphological dire wolf" my ass. Which is coincidentally where Colossal pulled the white coats from…

Give me an example of a modern temperate/grassland predator that's white*, I'll wait. *Excluding white lions, which are an uncommon but resilient morph resulting from leucism.

I based my Aenocyon design off bushdogs and dholes. They are called Masked Wolves in Kindred's setting, because I enjoy a good pseudo hyena niche uvu-b

Extremely extremely long 'thoughts' below the cut lol c':

Preface: in this discussion the term "dire wolf" has too many meanings, as such I will be referring to them as follows:

Thrones' wolves: for the huge, white, fantasy animals from Game Of Thrones GMO wolves: for Romulus, Remus and Khaleesi, Colossal's creations, Canis lupus Aenocyon: for Aenocyon dirus, the true, extinct dire wolf known from fossils across North America

----

Part 1: That's not a dire wolf-

The first question everyone has been asking is "So, are dire wolves de extinct now?" The answer is an emphatic "NO!" from anyone with knowledge of genetics, palaeontology, or taxonomy.

Aenocyon dirus were actually not wolves, nor dogs, but a secret third thing.

They are canids, but last shared a common ancestor with grey wolves and their lineage some ~5.7 million years ago.

For context, this paper suggests a similar divergence time between genus Homo (humans, Neanderthals and co) and Pan (chimps and bonobos); animals that look and behave markedly differently from each other.

The genomes of Canis lupus and Aenocyon dirus being 99.5% similar may sound like a lot, but again, humans share 98.8% with chimps, and 99.7% with Neanderthals, and yet are very distinct from both.

Skeletally, behaviourally, in soft tissue, etc, you could tell any of the three apart; the same goes for Aenocyon and Canis members.

Additionally, Colossal made 20 changes in 14 genes.

The grey wolf genome has 2,447,000,000 base pairs. Does that maths seem a bit off to you?

That's not even enough to change a grey wolf into a domestic dog, let alone an ancient outgroup!

This would be akin to modifying a lion to have bigger teeth and saying you resurrected Smilodon fatalis.

Or editing a Asian Elephant genome so they retain their juvenile hair and calling it a Woolly Mammoth.

It's a bold-faced lie.

Beth Shapiro says "they look and act like dire wolves" but that, too,simply isn't true.

Visually, the GMO wolves simply aren't what Aenocyon would have looked like. It's what a Thrones' wolf looks like.

Hmmmmm, funny about that, seeing George R R Martin helped fund the 'dire wolf project'...

As with many fossil animals, we don't know much about Aenocyon's behaviour.

You can't say the GMO wolves (who are also still pups) act like Aenocyon, because that's based off nothing.

What we do know is Aenocyon were likely pack animals (from the sheer number found in La Brea Tarpits), and crunched more bones than modern wolves (from their many broken teeth).

Also, crucially, they had Wild Sex Lives (from the many, huge, broken and healed bacula... youch).

Colossal is also being colossally shady by: doubling down on their bs use of the outdated "morphological species definition", blatantly misleading the public with their use of the words 'cloning', 'dire wolves', and 'de extinction', and refusing to share their methods in a peer reviewed paper before going public with a clickbait headline.

Do not trust them with your Red wolves either. They're using coyote hybrids and considering what they deem 'close enough' for a dire wolf, I wouldn't put any money on the quality of their GMO red wolves either...

Also can I just say, whatever genes they modified to "make the skull larger" clearly didn't impact the lower jaw...

No, I'm not sorry for this image uvu-b (But for real look at that poor pup and his overbite jfc)

Part 2: -and if it was, that wouldn't be good either.

I fundamentally do not support de extinction.

No, not even for the Thylacine, not even for passenger pigeons, nor the dodo. Even my beloved Homotherium should be left in the past.

This might be an unexpected stance because I am, surprising no one, a big fan of extinct animals, megafauna and otherwise.

But the thing is, I'm an even bigger fan of actual, living animals.

The animal ethics of de extinction are dubious at best.

The surrogate dog mothers of the GMO wolves likely won't live good lives.

I wouldn't be surprised if they were destroyed after being used, because their bodies could contain feto microchimerisms and Colossal absolutely doesn't want their special wolf genome getting out.

I doubt the GMO wolves themselves will live a full life before they outgrow their hearts, like Ligers.

This would likely be the case for any modern animal genetically modified into megafauna; a body not adapted to deal with the increased size.

Purely conjecture, but I also wouldn't be surprised if Romulus, Remus and Khaleesi have vision/hearing issues from their white coats.

White coats in wolves are associated with hearing impairments, so the gene used for these animals was from domestic dogs. Meaning Colossal has created a very expensive wolfdog.

Again, what kind of life are these wolfdogs supposed to live? As awful pets for the rich? In a zoo? Released to pollute wild wolf genomes? (assuming they're fertile; I hope not)

Regardless, it's not looking good if they ever planned to have them be 'wild animals'

Even true clones (which the GMO wolves are not) tend to have health issues.

Celia the Pyrenean Ibex (bucardo) was cloned, but the clone died after 9 minutes from a deformed lung.

So in 2003, this made the bucardo the first species to go extinct twice, yippee?

There's also the problem of genetic diversity.

How many intact genomes do you have on hand?

For dire wolves the answer is Zero!

To my knowledge, we don't have the full genome coded from one individual, just Frankenstein-ed from many. Which is fine for sequencing the canine family tree's relatedness, but not for cloning.

The absolute minimum individuals to survive a genetic bottleneck is said to be 50 in larger species. Called the 50/500 rule, it states that 50 is enough to survive, but 500 is required to prevent genetic drift.

To which I say, good luck!

Even with well preserved permafrost species (such as woolly mammoths), you'll have a hard time finding 500 individuals with prefect genomes.

And then, where will you put them?

If you were to, somehow, make a breeding population, where are they going? A national park? A zoo? Is their old habitat still available to them?

In Aenocyon, the answer is simply "they don't have a niche anymore".

Unlike the Thylacine or Dodo, humans did not directly cause the extinction of Aenocyon dirus. And even if they had, it was 10,000 years ago!

Would making room for a de extinct species impact the habitat/niche of another species?

Regular grey wolves fill Aenocyon's role as a canine mesopredator, with Puma as the apex (alongside bears as an apex omnivore).

With the loss of megafauna to prey on, a de extinct predator would just compete with other, also endangered species.

Animals also change the environment they life in.

Mammoths will clear trees like modern elephants. This would recreate the Mammoth Steppe, but those trees making up the taiga and boreal forests are themselves crucial habitat.

Other species have moved in since the mammoths' extinction. Siberian tigers, lynx, muskoxen, brown bears, elk, moose, and so many others; many endangered.

Trees also prevent erosion, which is already happening at unprecedented rates due to agriculture and deforestation.

Crucially: What's to stop an extinct animal going the same way it went out last time?

Ask yourself this:

Would the average American appreciate "flocks of Passenger pigeons big enough to darken the sky and whiten ground with their guano"?

Would people suddenly be okay with lions in Europe eating their livestock, when they are champing the bit to shoot Iberian wolves again?

Would Tasmanians suddenly feel the same about the Thylacine, when farmers in Australia still happily kill dingoes and eagles for lamb predation? [citation, I am an enviro technician and have had farmers tell me they shoot Wedge-tails, knowing I'm a toothless lion to stop them.]

I doubt it

At what cost?

Are we going to find 50 thylacine genomes?

If so (doubtful), how much will cloning and/or modifying a relative into a thylacine cost? Now that x50?

Wouldn't that money be better spent on quoll reintroduction?

What about finding 50 gestational carriers for mammoths?

Are you going to use their closest relative; the already critically endangered Asian Elephant?

Wouldn't that time and effort on those elephant mothers be better used making more elephants?

And the social cost:

If extinction isn't forever, what's to incentivize lawmakers to fund conservation?

Really, it comes down to this:

Why bring back the dire wolf when we could put this money into protecting the Iberian and Red wolves?

Why bring back the thylacine when their cousin is dying of a transmissible cancer?

We've already seen the impacts of "extinction isn't forever anymore", with those in power already trying to cut funding to conservation, because you can "just bring them back".

But as we've seen time and time again: there is no Planet B. There is no De-Extinction, not really.

Maybe what was gone should stay gone, so we can focus on what we still have.

#*farkin mike drop*#whoops this took an extremely long time I can't be trusted not to write a thesis for things like this bc im Passionate#sorry not sorry for the colours- it makes it easier for my brain so I hope it helps this site full of other ND people lolol#also ur getting this instead of a Kindred update bc i have not been able to work on pages there's been 6767687 family members here all week#mammothask#stressingcosmos#GMO wolves#<- my tag for these poor beasts#bc they sure aren't dire wolves#bc u see dire wolves are#aenocyon#dire wolf#masked wolf#romulus remus and khaleesi#de extinction#animal ethics#scientific ethics#paleo stuff#sorta#wolf#grey wolf#gray wolf#pavlova pictures#bc i drew this

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rain World Art Month, Day 3: Pole Plants

Another speculative biology diagram! This time for the beloathed pole plant...

Today I wrote a bit of a thing about my thoughts making this:

I've always sorta wondered what was beneath the surface and what the rest of the pole plant looked like. First of all, I firmly hold the belief (or rather, headcanon) that it is not actually a "plant" at all (to the extent that irl taxonomy can be applied to RW creatures in the first place). Aggrevated pole plants move too deliberately for it's grasping behaviour to be a venus fly trap-like reflex, especially since they can get "annoyed" at you for throwing rocks at them.

With the idea of it being some sort of weird stationary pseudo-animal, like a sea anemone or sponge, I started drawing and ended up with this beetroot looking guy! I also rlly wanted it to have an asymmetrical body plan...

Most of its body is dedicated to digesting prey, with its most prominent features (aside from its "tongue") being a sphincter-mouth that can open to swallow larger animals (like lizards), a large acid-filled digestive basin, an enlarged enzymic gland and an anus. During rainless periods, it extends its pole-like "tongue" in hopes that passing creatures will attempt to climb or otherwise grab onto it. Once this happens, it grasps and constricts its prey and pulls it into its mouth, where it chokes the creature to death. The rest of the cycle is then spent slowly digesting the creature, and once this is done and the rain has begun to fall, it opens its mouth and anus and lets the rain water flush any leftover bones and carapace that it could not digest out of its body and down through the pipe that the pole plant is situated within. Such is the wonderous life of a pole plant (I imagine). Ty for reading my silly lil thoughts if u did...

#rain world#rain world art month#art#rain world fanart#fanart#pole plant#pole plant rain world#speculative biology#speculative biology art

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wed Beast Wednesday: Mudskippers

For this Wet Beast Wednesday I want to go over a fish that seems to have forgotten it's a fish: the mudskipper. Mudskippers are amphibious fish that are just as comfortable on land as they are in the water. Mudskippers are classified as gobies but goby taxonomy turns out to be weirdly complicated and there's not a clear consensus of what clade constitutes a goby. Mudskippers are members of the subfamily Oxudercinae and consist of at least 23 species, with some sources list up to 43 species. Not all members of Oxurdercinae are considered mudskippers, only those who live a partially terrestrial lifestyle. Mudskippers live in tropical to temperate regions throughout the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans.

(image id: a mudskipper sitting on a branch just above the surface of the water. It is a long, skinny fish with a large head and two large eyes positioned on the top of its head. Its pectoral fins are large and its dorsal fins are folded up. The tail fin is submerged and not easily visible. It is mostly light brown, but has a black stripe going down the body and small, blue speckles all over.)

Mudskippers have a fairly standard goby body plan, but with adaptations to support their terrestrial lifestyles. The most important adaptations for a fish that wants to live on land is to develop an ability to oxygenate themselves without continuously passing water over the gills. Mudskippers have developed two ways to breathe out of water. The first is with their gills. The gill pouch can be sealed off, trapping a bubble of water inside, keeping their gills continuously in contact with water. The gill filaments are also stiffer than in most fish and do not coalesce with each other if they dry out. In addition, the skin, mouth, and throat can absorb oxygen with the help of many small blood vessels, but must be wet to do so. Mudskippers spend up to 3/4th of their time on land, but will die if they dry out. They live mostly in the intertidal zone, primarily on mangrove forests and mud flats, where they have access to water but also plenty of room to move and hunt on land. To assist in moving on land, the pectoral fins have evolved into pseudo-feet. The fins of most ray-finned fish are simple, consisting of a group of inflexible fin rays attached to the body that can be moved (individually in some species) by muscles in the body. Mudskippers have their fin rays jointed part way through and again at the connection to the body. This creates a "shoulder" and "elbow" joint in the fins, giving them greater strength and flexibility. Mudskippers can drag themselves along with their pectoral fins in a skipping motion, which is the source of their common name. Some species can use their pectoral fins to climb on mangrove roots or other exposed plants and rocks. Mudskippers are also adept jumpers. By rapidly folding and extending their tails, mudskippers can leap up to 61 cm (24 in). This is used primarily to escape predators and for display purposes, but may also be used to leap onto higher vantage points. Mudskipper eyes are also special. They are located very high on the head and protrude quite a bit from the body. This eye position gives the mudskipper a very wide range of vision and allows them to bury themselves in mud, only leaving the eyes exposed. Mudskippers can also blink, something other fish cannot do. To blink, a mudskipper will retract an eye into its body while a membrane called a dermal cup rises to cover the eye. Blinking allows the mudskipper to clean its eyes and keep them moist on land. Mudskippers are small fish, with the largest species (Periophthalmodon schlosseri, the giant mudskipper) getting to about 28 cm (11 in) long.

(image id: two mudskippers sitting on sand. one has its front end eld up by its pectoral fins and its mouth partially open. This one's dorsal fins are extended, which run down the body. The other one is lying flat had has its both closed and its dorsal fins folded down. They are light brown with dark stripes. The dorsal fin has many blue dots)

Mudskippers build burrows using their fins and mouths. These burrows are used for shelter and for mating. Most burrows will have their oepning exposed during low tide but will flood during high tide. A chamber in the burrow holds a pocket of air even when flooded. This allows the mudskipper to breathe even if the water is low in oxygen, though it must periodically bring in mouthfuls of air to refresh the pocket. During mating season, males will build burrows. after the burrow is completed, he will come out and start competing for mates. Competitions involve jumping, with the make who can jump the highest attracting the most females. Sometimes mudskipper will fight over territory, though males are especially prone to fighting during mating season. Fights consist of the fish demonstrating at each other with open mouths and raised dorsal fins. During fights, they will also vocalize at each other, with the one who can string together the most vocalizations being the winner. How mudskippers vocalize is still a mystery. Most fish who make sound do so with their swim bladders, but mudskippers don't have swim bladders. Once a female picks a male to mate with they will return to his burrow, where she lays eggs and he fertilizes them. The female departs afterwards, leaving the male to care for the eggs. He will guard the burrow against predators and bring air in to keep the eggs oxygenated until they hatch.

(image id: a mudskipper mid-jump. Its fins are all extended and its body is covered in blue spots)

(image id: two mudskippers fighting. They are facing each other with mouths open, heads pointing up, and fins fully extended)

The majority of mudskipper species are carnivores, though some have transitioned to being detritivores. They hunt invertebrates including worms, insects, and crabs, and some species are cannibalistic. They can hunt both on land and in water, but are more effective at land hunting. When in water, mudskippers use the same suction feeding method that most predatory fish use. When on land, mudskippers use a different method. They carry water in their mouths and chase after prey. When positioned over their prey, the mudskipper will spit some of the water out, allowing it to cover the other animal. It then sucks the water back in, carrying the prey with it. The suction also help propel the prey to the throat, which is useful because mudskippers lack tongues to push their food back.

(image id: a mudskipper in its burrow.The entrance to the burrow is raised above the ground and made of sand. Only the mudskipper's head is visible)

Mudskippers are useful to science in a few ways. They are useful as bio-indicator for the health of their environments. Breathing through your skin is a double-edged sword. It lets you oxygenate on land, but also makes it easier for harmful chemicals to enter the body. Dissection of certain organs allows for testing of environmental chemical levels. Passive observation can also provide data on environmental health. Mudskippers are also used as a model organism for scientists studying the transition of vertebrates to land. While the fish that colonized land were lobe-finned fish as opposed to the ray-finned mudskippers, they can still provide clues to the adaptations and lifestyle of the earliest tetrapods. Outside of science, mudskippers are used for food and as pets. The different species had different classifications by the IUCN ranging from least concern to critically endangered. Their main threats are pollution, habitat loss, and overfishing.

(image id: two mudskipper facing the camera with their mouths open)

#wet beast wednesday#fish#fishblr#fishposting#mudskipper#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts#fish that forgot how to fish

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need more people to read the Memoirs of Lady Trent

So that I can flail about them. They have EVERYTHING; pseudo-Victorian society, natural history as a developing science, dragons, the barriers imposed by class and sex to pursue a life in that world and the sacrifices necessary to do so, queer characters (there's a self-described asexual character with a big role in the second book and a genderqueer character in the third), more dragons - different species of dragons, dragons as their own evolutionary taxonomy - women building their own networks to support other women, lady engineers, one of the most important relationships in the series is a deep and abiding male/female platonic friendship, but there is also an achingly beautiful slow-build romance story that I really want to shout about more but I can't because spoilers. There are maps in every book, and examples of Lady Trent's sketches, and the cover art alone makes them books work having on a shelf. Not to mention the dragons. And also the invention of paragliding. The importance of the paragliding cannot be understated.

They are wonderful, and underrated, and not at all like the Queen's Thief and yet I get such Queen's Thief vibes reading them...Basically, if you need something good to read this summer, I have a suggestion.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside and Outside: Wolves and Punks

Early-twentieth-century observations of sex between prisoners were shaped by a burgeoning sexological literature whose conceptual categories proved useful in understanding and mapping prison sexual culture. But heightened attention to prison sex in the 1920s and 1930s, on the part of penologists, prison administrators, and prisoners themselves, is not explained simply by the availability of a new conceptual template. While sexologists puzzled over the etiology of same-sex practices performed by apparently "normal" people, those practices would have been more easily and readily comprehended in urban working-class communities of the period.

George Chauncey has documented the visibility of queer life in early-twentieth-century New York City and its integration in working-class and immigrant communities. In that world, Chauncey writes, "the fundamental division of male sexual actors... was not between "heterosexual' and 'homosexual' men, but between conventionally masculine males, who were regarded as men, and effeminate males, known as fairies or pansies, who were regarded as virtual women, or, more precisely, as members of a 'third sex' that combined elements of the male and female.

Prisons were enclosed communities that gave rise to and perpetuated their own distinctive cultures, but they were far from hermetically sealed. The attribution of sexual deviance or "queerness" to the gender transgression of "fairies" and the possibility of conventionally masculine men having sex with them without compromising their status as "normal" found an echo in men's prison populations. Prison vernacular, especially the terms used to denote participants in prison sex, overlapped closely with working-class vernacular and the roles and expectations it delineated, no doubt reflecting its importation into prisons by a disproportionately working-class inmate population and perhaps its exportation into working-class communities as well.

Prison sexual vernacular was part of a prison argot that attracted considerable attention more generally, from both prison insiders and outsiders. Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer and prisoner Hi Simons was fascinated by prison language that seemed to him "full of swagger and laughter, because of the vivid if often violent and vile poetry that streaked through it.... To use it," Simons wrote, "made us feel bold and free." Simons acknowledged that "except for a few terms from the I.W.W. vocabulary," incarcerated labor organizers "added nothing" to the specialized vocabulary of prisoners, but he worked to compile a dictionary of "prison lingo" he learned while an inmate of the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth and published it in 1933. Others in this period published glossaries of prison terms as well, testifying to the emergence of a collective consciousness and shared culture among prisoners.

Central to prison argot were the coded terms that delineated sexual types and declared expectations about sexual acts and roles, offering a vernacular analog to sexological taxonomies. Noel Ersine included eighteen terms referring to same-sex sex among the fifteen hundred entries in Underworld and Prison Slang, published in 1933. Simons imagined that "a complete prison dictionary" would constitute "an encyclopedia of all imaginable sexual deviations," rivaling the sexologists' ambitions in cata loging sexual variance."

Prison constituted a unique transfer point between expert and vernacular sexual discourses, the terms of one often inflecting the other. Those men typed by sexologists as "pseudo-homosexuals" or "semi-homosexuals" were known to male prisoners as "wolves" and "punks." Those were men whose participation in same-sex sex was presumed to spring not from their nature but from the exigencies of circumstance. Wolves, sometimes also referred to as "jockers," were typically represented as conventionally, often aggressively masculine men who preserved (and according to some accounts, enhanced) that status by assuming the "active," penetrative role in sex with other men. As Victor Nelson made clear, "The wolf (active sodomist)... is not considered by the average inmate to be 'queer' in the sense that the oral copulist... is so considered. " In contrast to many accounts by penologists and some prison officials who blamed fairies for prison seduction, those most familiar with prison life typically credited wolves with initiating sex behind bars.

That initiation was often aggressive. As their name suggested, wolves were understood to be sexual predators, wooing, bribing, and sometimes forcing other men to have sex with them. Wolves were "always on the lookout for a handsome boy with a weak mind, who had nobody to send them in some food and money," sociologist Clifford Shaw wrote in his 1931 case study of a young juvenile delinquent." Berg described the process by which the wolf secured a sexual partner as "a campaign in which all the luxuries of prison - candy tobacco, sweets, and choice foods - are pressed upon the newcomer." Once the object of the wolf's affection accepted the goods offered, "he is quickly given to understand that he must repay the favor in kind." Sometimes seduction by wolves was described as a deliberate and cold-hearted maneuver of engaging a younger inmate in a relationship of indebtedness, which could be repaid only by sex. Others offered examples of more heartfelt and romantic courtship. Nelson recalled "Dreegan," the "champion "wolf" at Auburn Prison," who

outrageously flattered the objects of his lust; he gave them cigarettes, candy, money, or whatever else he possessed which might serve to break down their powers of resistance; and otherwise courted' them exactly as a normal man 'courts a woman. Once the boy had been seduced, if he proved satisfactory, Dreegan would go the whole hog, like a Wall Street broker with a Broadway chorus-girl mistress, and squander all of his possessions on the boy of the moment.

Wolves may not have been motivated by "true" homosexuality, in the understanding of contemporaries, but the relationships they forged in prison were often far from casual. Jealous rivalries and violent confrontations among inmates were credited to the passionate feelings of some wolves for their partners. Inmate-author Goat Laven described "brutal fights," some fatal, that arose from sexual jealousies: "It means a kick in the back to steal another man's kid." Louis Berg seconded Laven account. "The unwritten law of the prison forbids any 'wolf" to make approaches to another's 'boy friend' once he is wooed and won," Berg observed. "But it is not to be expected that men who break the laws for lesser urges will hesitate when they are driven by passions that rock them to the roots of their being. Fights occur between 'wolves' over some boy which are sanguinary and even end in murder."

Berg went on to recount the murder of "Mildred," an inmate at Welfare Island, by her jealous ex-lover. "From all accounts, Berg observed, "Mildred' was the victim of jealousy caused by 'her' unfaithfulness. That 'she' paid with 'her' life partner. shows the seriousness with which such prison marriages' are regarded." To some, the jealous violence that prison relationships could spark testified not only to depth of feeling but also to their similarity to heterosexual relationships. In a disturbing comparison, Berg concluded that Mildred's murder "proves how completely such relationships are identified with the normal ones between men and women." Charles Ford described jealousies among female inmates that resulted in fist fights, "hair pullings," and "every other conceivable type of trouble making activity" and that were even more real than husband-wife jealousies."

One theory explaining the existence of prison wolves, enshrined in inmate lore by the early twentieth century, proposed that "a 'wolf' is an ex-punk looking for revenge!" The object of wolves' and jocker attentions were known as "punks" and "kids," often identified as younger inmates, unfamiliar with life behind bars and unable or unwilling to defend themselves physically. A type recognized in prison argot at least the early twentieth century, punks were understood to be "normal" men, vulnerable to sexual coercion by other inmates because of the combination of small physical stature, youth, boyish attractiveness, and lack of institutional savvy. A few accounts suggested that punks were potential homosexuals whose latent desires were nurtured and realized the prison context, but most saw them simply as the unfortunate victims of wolves.

The punk's fate was often attributed to naïveté and, especially, his ignorance of the inmate code and the consequences of indebtedness. Charles Wharton wrote in his 1932 prison account of a fellow inmate, "a mere boy" who "seemed to have come direct from a farm" who had "all the bewilderment of a child thrust into strange, frightening surroundings." The youth soon became the object of "pretended interest and sympathy" from other convicts, who showered him with presents, "silk hose, fancy underwear, food stolen from the kitchen, and best of all, cigarets [sic], the gold standard of prison barter." In the process, Wharton wrote, the boy "became a wretched victim of the most vicious circle in Leavenworth's convict population.

Punks also suffered as a result of their youthful good looks. Jim Tully, author of the many books on his experiences on the road as a hobo and time in prison, recalled Eddie, a young inmate "with yellow hair and wondering hazel eyes" who was "too beautiful to be a boy." Eddie's life in prison as a result "was made a constant hardship by sex-starved men." Berg wrote that prison populations always include "boys at that uncertain age where they have a good deal of the feminine in them." Such boys, Berg wrote, "are in most prized in jails and prisons as virgins." Berg also attributed the fate of punks to "biologic inadequacy (another name for lack of guts)."

Whether understood to be the victims of their own attractiveness, their youth and small stature, or their cowardice, punks were never depicted as wholly willing participants in sex with other men. Although there was little attention to overt sexual violence in early-twentieth-century prison writing, many acknowledged that some form of coercion was often involved in sex in prison, in men's prisons especially. Like wolves, punks were also understood under the rubric of "acquired" homosexuality - they participated in sex with other men not because of a constitutional condition but because of the unusual circumstances of prison life. "Had they never gone to prison," Berg wrote ruefully, "most of them would today be normal men."

Prison sexual vernacular and the culture it delineated overlapped particularly closely with that of itinerant laborers, tramps, and hoboes who traveled the country's highways, rural byways, and railroad arteries in the early decades of the twentieth century. The association between tramping and homosexuality was strong enough by 1939 for a textbook on prison psychiatry to warn of "the possibility of homosexuality in prisoners of the vagabond type," since "this tendency among them appears to be very widespread." In his 1923 study The Hobo, sociologist Nels Anderson characterized homosexual practices among homeless men as "widespread and described relationships between older men, known as wolves or jockers, with younger men, referred to as punks, kids, or "prushuns." In transient communities, young men partnered with older, more experienced men who promised to protect them and teach them how to survive life on the road in return for domestic and sometimes sexual favors.

Judging from many accounts, those relationships were often predatory and abusive. Jim Tully, whose experiences as a "road-kid," hobo, circus worker, prisoner, and professional prize-fighter provided the material exper for his twenty-six books, characterized the jocker as "a hobo who took a weak boy and made him a sort of slave to beg and run errands and steal for him." Punks, he reported, "were loaned, traded, and even sold to other tramps." John Good recalled that the "criminal tramps or yeggs" who were his companions on the road in turn-of-the-century Denver "needed a boy to beg and steal for them, and to listen around for information." "These boys are degraded to unnatural uses," Good reported, "as well as trained in the arts of pickpocketing and sneak-thieving." Josiah Flynt, an early participant-observer of transient life, also described relationships between boys and their jockers, in which "abnormally masculine" men take "uncommonly feminine" boys as partners." Those attachments sometimes lasted for years, and boys remained with their jockers until they were "emancipated."

Men who lived on the road and on the economic margins were vulnerable to arrest, and incarceration in jails and prisons was a nearly inevitable experience for hobos, tramps, and transient workers. It is not surprising. then, that the vocabulary of prisoners would borrow closely from that of hobo culture, another nearly uniformly single-sex world populated by working-class men. Some prison terms revealed a direct etymology between hobo and prison terminology. When Jack London was arrested for vagrancy in Niagara Falls in 1894, he was locked up in the "Hobo." "The Hobo," he explained, "is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principle division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo." Hi Simons defined the term "Bo" as both a "hobo" and "boy, catamite" in his dictionary of prison argot. The direction of influence was probably two-way, and some prison terms were no doubt ported into hobo and working-class vernacular as well.

The importation of sexual vernacular, customs, and assumptions about same-sex practices from transient men as well as from a larger ur-working-class world meant that some prisoners were familiar with the sexual culture they found behind bars. Fiction writer Chester Himes, who was sentenced to the Ohio State Penitentiary in 1928, claimed "that nothing happened in prison that I had not already encountered in outside life." Himes grew up in a middle-class African American neighborhood in Cleveland, but youthful desire for excitement drew him to the city's rougher side. In prison, he wrote, "all sex gratification derived sodomy, and I had encountered homosexuals galore around the Matic Hotel and the environs of Fifty-Fifth Street and Central Avenue Cleveland." The many incarcerated men with transient pasts would've been similarly familiar with wolf-punk relationships in prison, which mirrored man-kid relationships on the road.

But while prisons, then as now, were by disproportionately populated by working-class inmates, they drew prisoners from other demographic groups as well, some of whom were unfamiliar with prison sexual terminology and the roles and assumptions it described. The persecution of political radicals under the Espionage and Sedition Acts passed during the First World War and in the wake of the Palmer raids of 1919 resulted in the incarceration of activists in the 1920s, many of whom became vocal and articulate critics of the American prison system while behind bars. These spokespeople for the working class often betrayed their own distance from and naïveté about working-class sexual life in their prison writing, and many were shocked by the sexual life they witnessed behind bars.

Alexander Berkman, for example, was candid in detailing his own prison sexual education in a chapter on an encounter with another prisoner, "Red," a hobo who worked alongside Berkman. When Red announced to Berkman, "you're my kid now, see?" Berkman claimed not to understand him and asked him to explain. Bewildered by Berkman's naiveté, Red exclaimed, "You're twenty-two and don't know what a kid is! Green? Well, sir, it would be hard to find an adequate analogy to your inconsistent maturity of mind." When Red explained to him the practice he termed "moonology," which he defined as "the truly Christian science of loving your neighbor, provided he be a nice little boy," Berkman professed not to "believe in this kid love," and was deeply shocked, protesting that "the panegyrics of boy-love are deeply offensive to my instincts. The very thought of the unnatural practice revolts and disgusts me." The pedagogical question-and-answer structure of this chapter allowed Berkman to tutor his readers in "moonology" while maintaining claims to his own sexual innocence. He may also have intended to contrast Red's perverse sexuality with his own presumably platonic love for another inmate that he described later in the memoir. But Berkman was far from alone among early-twentieth-century inmate narrators in professing innocence of same-sex sexuality before life behind bars.

When attorney and former Illinois state congressman Charles S. Wharton was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth penitentiary in 1928 for conspiracy in armed mail robbery, he acknowledged his own pre-prison innocence. Prefacing his discussion of "the worst of all phases of prison life," which he attempted to describe "as delicately as possible," Wharton wrote that, "looking back, I felt that I had been everywhere, seen everything, done about all which the average man-about-town is expected to do, and I held that impression until Leavenworth made me feel like a country yokel staring slack-jawed at his first sight of urban sin."

Socialist and anti war activist Kate Richards O'Hare was similarly shocked and appalled by the homosexuality she witnessed as an inmate of the Missouri state penitentiary in Jefferson City in 1919-20. Scoffing at O'Hare's estimate that 75 percent of her fellow inmates were "abnormal" as "entirely too high," Fishman speculated that she was "naturally led into such an exaggeration because, having no previous personal knowledge of prisons, she was swept off her feet to find that such things existed. She was utterly amazed when I told her that homo-sexuality was a real problem in every prison."

Eugene Debs, who was convicted of violating the Espionage Law in 1918 and sentenced to ten years in prison, lamented that "every prison of which I have any knowledge... reeks with sodomy" and wrote with dismay about "this abominable vice to which many young men fall victims soon after they enter the prison." "I shrink from the loathesome [sic] and repellant task of bringing this hidden horror to light," Debs wrote. "It is a subject so incredibly shocking to me that, but for the charge of recreance that might be brought against me were I to omit it, I would prefer to make no reference to it at all." Debs wrote in near-apocalyptic language about the fate of the boy "schooled in nameless forms of perversions of mind and soul" and prison sexual practices that "wreck the lives of countless thousands and send their wretched victims to premature and dishonored graves."

Whether shocked or inured, prisoners of all stripes acknowledged sex in both men's and women's prison as nearly ubiquitous and its roles and customs elaborated to the point that it constituted a culture unto itself. That culture occupied a curious status in early-twentieth-century prisons. Officially, sex between prisoners was unequivocally forbidden. Prisoners who were found engaging in sex were punished, often by placement in solitary confinement and extension of their sentences. Some prisons took harsh and sometimes draconian measures to distinguish homosexual prisoners from the general population in order to humiliate them and punish their behavior. In the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, inmates were reportedly forced to wear a large yellow letter D (designating them as "degenerate") if they were discovered having sex.

The superintendent of the Ohio prison at Chillicothe boasted to the director of the Bureau of Prisons, in response to a question about how he handled the problem of "sex perversion" at the institution, that he had found a way to deter such practices through the use of humiliation. "By this I mean that all known perpetrators or anyone anyway connected with sexual perversions be been compelled to sit at a certain table at the mess hall." A report from Kentucky noted that inmates convicted of sexual offenses had one side of their heads shaved to identify them. These practices of marking prisoners as homosexual were forms of punishment for sexual transgression; they also suggested the need for the production of a legible marker of homosexuality that ran counter to the notion that homosexuals, inside and out, were easily identifiable by their gender transgression.

Homosexual prisoners were also dealt physical punishments. A photograph from a Colorado prison depicted two African American prisoners wearing loose dresses, perhaps as another form of stigmatizing market of sexual deviance, and pushing wheelbarrows filled with heavy rocks as a form of punishment for same-sex sex. Kentucky physician F. E. Wylie proposed sterilization and "emasculation" that would "make it impossible for degenerates to commit sex crimes," adding that "surgery might even be used as a punishment" for homosexuality. The authors of an investigation of the Oregon state penitentiary in 1917 moved further to argue that "in cases of congenital homo-sexuality in the penitentiary," the more radical surgery of castration was necessary, to deprive offenders not only of the ability to procreate but of their libido as well. By the 1920s, more than half of the United States had adopted sterilization laws and some targeted "moral degenerates and perverts" specifically. Those laws were most easily and readily applied to people in prisons, mental asylums, and other carceral institutions.

Sex in prison was officially prohibited and sometimes harshly punished. But because of the difficulty of detection and the belief in its inevitability, prison officers often seemed to take it in stride. Joseph Wilson and Michael Pescor criticized prison officers who "regard homosexual practices as only another kind of dirty joke" and wrote that it was "essential that "this question shall always be considered gravely-never with smiles smirks, and a shrug of the shoulder" in their 1939 text on prison psychiatry, suggesting that this was often precisely how it was treated. Berg confirmed that to officials at Welfare Island, "the 'fairies' were, for the most part, simply the butt for lewd jokes. When they spoke of perverts it was with the kind of indulgence that one uses toward children whose peccadillos are amusing rather than serious." He added that "sex indiscretions" were "rarely detected and still less frequently punished."

If prison guards could not be relied on to maintain a properly vigilant and condemnatory attitude regarding prison homosexuality, the some hoped, prisoners themselves would rise to this role. "Only the co-operation of the decent element will ultimately weed them out," Sing Sing warden Lewis Lawes speculated in 1938. Wilson and Pescor went so far as to suggest that if homosexuals "received a reasonable dose of violence" at the hands of prisoners "known to be aggressively heterosexual," it would "help build up a correct prison community attitude towards this question."

But the community attitude in men's prisons, to the extent that it is possible to generalize, seemed often to be characterized by a rough tolerance, even by those who presumably did not participate in same-sex sex. Samuel Roth, who spent several years in prison for publishing what was considered obscene material, noted that "one thing happened immediately," on his incarceration; "I lost my horrors of [homosexuality] as a vice." He was far from alone. Recalling his experience on a Georgia chain gang in the 1930s, George Harsh had "too many other things to think about to care what two consenting adults do between them." "Under the conditions," Harsh wrote, "I think such a situation was inevitable, and I could understand it and condone it." Indeed, the institutional culture of some prisons recognized the established place of prison fairies. Though fairies were segregated in Welfare Island's South Annex, they were allowed to stage a bawdy Christmas show called the "Fag Follies." In later decades, prisons would sponsor football and baseball games that pitted queens against jockers.

- Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. p. 61-73

#prison slang#convict code#wolves and punks#history of homosexuality#history of heteronormativity#sex in prison#life inside#research quote#reading 2021#hobos#tramps#working class culture#history of crime and punishment#american prison system#victor nelson#chester himes#samuel roth#hi simons#penology#prison administration#queer history

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

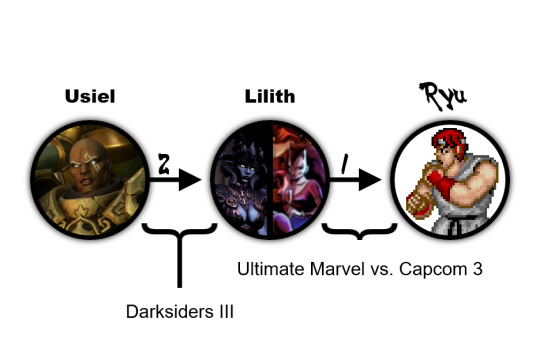

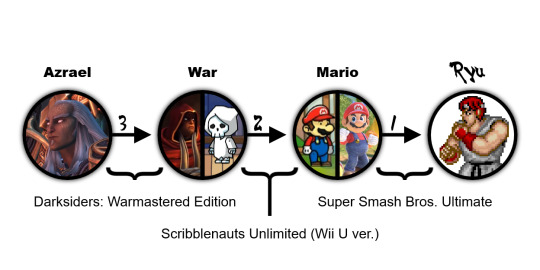

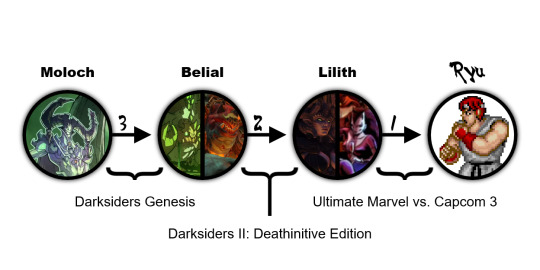

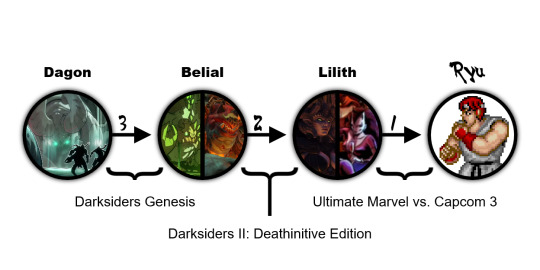

Ryu Number Chart Update: Darksiders

Here's a potential puzzler for you. Is Death death? (Stick with me for a moment here, okay?)

For some context, in the Darksiders franchise, Death—one of the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—is a major character. Most media where the Horsemen are a Thing tend to have Death (the horsemen) be the same character as the general personification of death, just specifically doing the Horseman thing at the moment. Good Omens goes with this interpretation, if I remember Good Omens right, which I very much might not. It's been a while.

In Darksiders, however, the Four Horsemen are, uh, cosmologically complicated. Specifically, they're Nephilim—fusions of demons and angels yes I know that's not what nephilim are supposed to be I didn't make this game—who rebelled against the Charred Council (a mysterious body who nebulously keep the balance somehow; it's really not clear) and were in turn eradicated by the only four nephilim who sided with the Council. These four became the Horsemen, and were subsequently sent out as the Council's underlings whenever a Real Big Issue required that sort of response. In the four games in the Darksiders series, there's approximately one line that could maybe with some creativity and also if you looked at it sideways be interpreted as the Horseman Death being also Death in general, but... Nah, I dunno, man.

Anyway, that's why "Death/Grim Reaper" and "Death (Horseman)" now have their own respective points in The Chart. Don't at me.

Not being able to use the Grim Reaper skin from Minecraft to hop between Ryu and whichever Darksiders character you want is a bummer, admittedly.

Luckily, Lilith is a Marvel character.

(That's her in the background. That's her at the bar. Side. Losing her religion.)

Funny thing—Usiel (often seen spelled "Uziel" or "Uzziel") is usually depicted as either a fallen angel, or a demon. There are a few sources that put him on the side of being a good'un, though, so this portrayal is cromulent enough. I mean, as cromulent as anything from Darksiders can be in relation to varying and contradictory Judeo-Christian tradition.

(Per game lore, a bunch of pseudo-Celtic-Norsey Old Ones are hanging out in a side dimension or something. I dunno, man. Darksiders II was weird.)

Lilith appears in Darksiders II and Darksiders III, which is nice if you're trying to reach a character from Darksiders II and Darksiders III, but less so if you're working with the original Darksiders or Darksiders Genesis.

That's alright, though. Turns out the Four Horsemen are up and summonable in Scribblenauts Unlimited:

... Y'know, I really do think there ought to be a quicker path to Azrael that exists somewhere in the Wide Wide World Of Video Games, but if there is, it's not on The Chart at the moment, so it doesn't exist. Don't at me.

Or actually, do at me. Then I can put that game on The Chart, too, if it doesn't give my arbitrary taxonomy a tummyache.

Incidentally, because I read up on angels a whole lot going through these games and if I can't Show My Work on my own blog where else am I gonna do it: Here's a Thing.

"Now, hold on a tick," I hear you say. "What are Moloch, Astarte, and Dagon doing in this game as Lucifer's mooks? Astarte wasn't a demon; she was a goddess in Ancient Near East religion, sometimes considered the equivalent of Ishtar! And Dagon wasn't a demon; he was an ancient Syrian god of prosperity! And Moloch... well, actually, nowadays people don't think Moloch was even a Thing, but he was traditionally interpreted to be a Canaanite god associated with child sacrifice! Excuse the pun, but what the Hell's going on?"

You might assume that some Final-Fantasy-style hinkiness is afoot—that the creators of Darksiders Genesis named their characters after mythological figures that are thematically similar but ultimately unrelated (go on, try to convince me that any incarnation of Final Fantasy's Leviathan is the same one from the Book of Job) (Please do not actually do this)—but it turns out we can heap the blame on one dude in particular: John Milton.

That's right, it's all Paradise Lost's fault. Turns out that according to Miltonic lore, Moloch, Astarte, and Dagon were originally angels, but then joined with Satan in his rebellion, fell, and subsequently played as gods to deceive mankind. Now, is it a little iffy that Milton took a bunch of non-Christian deities and went "yeah, these were demons all along"?

Most def. He was following in well-established Christian tradition, though. Ba'al-Zebub was a deity of the Philistines, while Belphegor comes from the deity worshipped by Moabites at the mountain peak of Peor, biblically referred to as "Ba'al-pe'or." Astaroth is another one that comes from Astarte. And of course, the less said about Baphomet, the better.

All of this is a long-winded way of saying that no, I'm not counting this Dagon as the Syrian one. Or the Lovecraftian one, for that matter.

Don't at me.

#ryu number#darksiders#darksiders: warmastered edition#darksiders ii#darksiders ii: deathinitive edition#darksiders iii#darksiders genesis#ryu#ultimate marvel vs. capcom 3#lilith#usiel#super smash bros. ultimate#mario#scribblenauts unlimited#scribblenauts unlimited (wii u ver.)#war#azrael#belial#moloch (paradise lost)#astarte (paradise lost)#dagon (paradise lost)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is OCD a Mental Illness?

My mother recently forwarded a piece from The Guardian that questions whether OCD is a mental disorder, that is, a disease with organic, biological root causes: abnormalities in the brain. That's indeed what I have long been told by health professionals.

But what if OCD is not a biological reality? As the author writes, haven't researchers proved with neuroimaging that OCD brains are different? But what about the fact that a great many disorders show the same kinds of brain changes?

According to the neuroscientists quoted in the piece, psychiatric diagnoses are not based on biomarkers. Rather, they are subjective constructs. There is evidence that exposure to environmental stress is the leading determinant of common mental health problems like anxiety, depression, and OCD.

The author's takeaway is this:

This is what I think is wrong with the medical model: a failure to understand mental health in context. An assumption that a disorder is a “thing” that an individual has, that can be measured, independent of subjective experience. The trauma model can be just as reductive, turning healing into an individual consumer journey and ignoring the environmental conditions in which wounds form. This has empowered professionals to decontextualise distress from the lives of those who experience it; to create pseudo-specific taxonomies of mental disorders. Diagnostic manuals have for decades been giving well-meaning psychiatrists and psychologists the illusion of explaining the suffering of the patient sitting in front of them. This system has hurt none more than those facing social adversity: financial deprivation, poor education, racial discrimination and so on, who are pathologised as though their reactive stress, and not the things to which they’re reacting, were the problem.

I'm still mulling this over, but one thing I know to be true is that when the circumstances and contexts around me change, so do my OCD symptoms. They worsen, for example, when I'm living alone and/or feeling isolated.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Really random question, but...

┌────── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──────┐

Assumption is:

Ghouls are in:

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

└────── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──────┘

now are ghouls are an:

Order/Family/Genus/Species?

─────────────────────────── ★´ˎ˗

Example:

Order: Carnivora

Domestic Cat

Family: Felidae

Genus: Felis

Species: Felis catus

── ── ── ── ── ── ── ── ── ── ── ──

Shares an order with:

Brown Bear

Order: Carnivora

Genus: Ursus

Family: Ursidae

Species: Ursus arctos

─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ★

Shares family with:

Tiger

Order: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Species: Panthera tigris

Genus: Panthera

─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ★

Shares a genus with:

European wildcat

Order: Carnivora

Family: Felidae

Genus: Felis

Species: Felis silvestris

─────────────────────────── ★´ˎ˗

#ghost band#ghost bc#the band ghost#rat's poll#ghoul headcanons#ghost the band#shitghosting#ghost poll#ghoul biology#pseudo taxonomy#ghost band poll#ghost bc poll#band ghost#ghoul poll#poll time

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think the Anda and the Noiad are from a shared throughline? - Kaz

so there is a broad northern animalism-shapeshifting based haplotype of vampires that includes the gangrel tzimisce and ravnos as well as other smaller bloodlines which includes the noiadi tlacique anda and various others

the specific taxonomy is harder to pin down but my current thinking is that the most primitive form from which others derived was likely lhiannon and the gangrel phenotype evolved from and largely displaced this to become dominant. from this the collective anda and noiadi split of from root gangrel stock as a branch expanded east.

the noidi would then give rise to the tzimisce (who mutated protean into vicissitude) who similarly largely went on to displace them. much like the lhiannon had been pushed to the fringes of northern europe by their gangrel descendents, so too the noiadi were pushed to the arctic by their tzimisce descendents.

(in recent history the tzimisce would themselves give rise via artificial means to a further lineage; the tremere)

meanwhile the andas expansion across central asia was eventually halted as they moved south and encountered the ravnos, who were distant cousins sharing ancestry with the gangrel and lhianon

the other significant divergences here include the ahrimanes who sprang from the basal lhianon stock and mutated lhianon magic into spiritus rather than protean and then also the tlacique who arise as the gangrel are developing protean and migrate to the new world where they become an extremely isolated population until the columbian exchange

so yes the anda and noidi are probably quite close cladistically speaking

of course these devellopments occured on an evolutionary timescale of tens to hundreds of thousands of years, and there is some degree of genetic exchange between these populations via diablerie; the idea that all tzimisce are descended from a single eldest tzimisce and share no ancestry with anda or noidi or others after that is clearly false as diablerie allows pseudo-hybridisation

unfortunately the modern rejection of diablerie is resulting in mullers ratchet taking effect in full force and a steady accumulation of genetic entropy - what is commonly called the thinning of blood in higher generations; historically this phenomenon was avoided via widespread diablerie in place of sexual reproduction

0 notes

Text

taxonomy

who but a narc pseudo-savior wants to punch a broken kid? she spent the better part of twenty years distant like the morning moon eyes closed and shadow boxing the likeness that she made of me an effigy to burn, to spurn, to turn away

0 notes

Text

The hell of it is is that the show isn't subtle on this point!

Like, SVTFOE is just... not a very subtle show in general when it comes to its politics. There is an entire-ass episode devoted to specifically this topic, which has, what, like a five-minute sequence where Star asks very blunt questions about who is and isn't a monster, and Moon responds nakedly with a series of answers that are explicitly "These people aren't monsters because they are our friends" and "These people aren't monsters because they are very rich" and "Rhombulus isn't a monster because he's on the MHC."

Then it spends another ten minutes hitting you in the face with this over and over with the "monster expert" who doesn't know that monsters are people. That's a deliberate writing choice; the monster expert could have been some sort of subtle crypto-racist with a set of calipers and a pseudo-intellectual hard-to-refute set of theories about how Buff Frog's skull shape means his thoughts move slower than mewmans, but no, they just hit you in the face with "this racial taxonomy is bullshit perpetrated by bigoted idiots."

It's one of my favorite episodes (I especially love that huge transforming model cart of Mewni that Star has, that's superb visual storytelling) but like. Did people just not watch it? Because, again: not subtle.

One thing I think it's important to understand is that the MHC aren't monsters.Sure, their "monsters" by our definition of the word, both literally and figuratively, but it's important to understand that, when characters in Star vs. say "monster", that isn't what they mean."Monster" within the world of Star vs. is a term with a specific political meaning: it refers to groups of sapient non-humans who are singled out as monsters, presumably for complex political and historical reasons. Who is and isn't considered a monster on Mewni has nothing to do with if they'd be considered "monsters" on Earth because they aren't using the word the same way we do. The MHC would never in a million years be considered monsters because there would never be a situation where marginalizing them like that would be politically expedient or even possible for Mewni's upper class, in no small part because the MHC are among them.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lockwood & Co. feature on the January 2023 Issue of the SFX Magazine

I'll put the text under the break if anyone can't access the photos :-)

"JOE CORNISH IS HAUNTED. NOT BY ANY BONE chilling apparition or plate-flinging poltergeist but by a time. A vanished age, of strange torments and diabolical dread.

“This is a world of draughty houses and windows that don’t quite close properly and creaky floorboards and clicking pipes,” he tells SFX, smiling over a Zoom connection. “The world I remember from my childhood, before double-glazing and insulation!”

Welcome to the phantom-infested Britain of Lockwood & Co. It’s a little like the 1970s, only even weirder. Adapted from the popular series of books by Jonathan Stroud, this new Netflix offering pits swashbuckling teens against the unquiet dead in a London spilling over with paranormal activity. Even the local A-Z, you strongly suspect, drips with ectoplasm.

ANATOMY OF A GHOST “I love supernatural stories,” says Cornish, who serves as lead writer and director on the eight-part series, “and it’s unusual to find a story where the science of ghosts has been so thoughtfully defined. There’s a broad set of rules for ghosts that most stories adhere to, but there’s not really an almost Darwinesque analysis of different types of ghosts, different species, different behaviours, a taxonomy.

“The idea that they can kill you by touching you completely changes the dynamic of a ghost story, brings it into the action-adventure realm. So you get everything great about a ghost story but these other genre elements really take it into a new place. “On top of that you’ve got terrific worldbuilding. This takes place 50 years into a ghost epidemic, and the world has really changed because of it. Different economics and different social structures have emerged. Because young people are more sensitive to the supernatural, which is a classic trope in ghost stories, it’s extrapolated into this world where young people are employed by massive adult-run agencies to detect and fight ghosts. “So it’s a pretty amazing bit of thinking, based on a very attractive set of genre ideas that have been around for ages but have never really been reinvented in such a clever way.”

It’s a more analogue world, where technological progress stuttered. And that’s a premise that appeals to Cornish, who made his name with the hand-tooled, micro-budget joys of The Adam And Joe Show – a pioneering ’90s celebration of geek culture, knocked together from toys, love and cardboard – before promotion to the big screen as director of Attack The Block in 2011.

“The world changed tack when the problem started, because everything that would be regarded as pseudo-science became real science,” he explains. “So the world stopped at the time of Amstrad word processors! “It became a more industrial world, because iron and salt and water can repel ghosts, so suddenly these almost Victorian industries are revived. Also, in a weird parallel way, old things are suddenly scary. Anything with an ancient history is potentially lethal, because it might be the source of a ghost.

“For me it felt like the early ’80s, when I was a teenager, because that was kind of pre-digital. It was a world that still had analogue media and you could buy records and fanzines. There was a world of printed youth culture that existed in a social way, that wasn’t on telephones and computers. You communicated in a much more person-to-person way back then. So that was pleasing for me as well – the series has this kind of retro-contemporary feel to it that’s half modern and half 50 years ago.” The spectral aesthetic in Lockwood & Co also takes inspiration from the past. “We started by looking at Victorian spirit photography. Because photography is pre-digital, it’s chemical, the ghosts feel very different, like a real physical presence. They feel as if they exist in the world of natural physics – we can’t really get away with hiding them.

“In other movies or TV shows you might glimpse a ghost as a jump scare and then it’s gone. Our ghosts are really present, and our characters fight with them, so we had to come up with a design that you could really train the camera on, and involve in an action sequence, and would be able to leap around and dive and swoop and bolt into a corner.

“They’re all made out of smoke, they’re all made out of something ethereal. There are lots of different types in the series, lots of colours and densities and shapes. We tried to get away from super-digital ghosts and make them feel like they could really exist in a science experiment.”

Lockwood & Co looses its phantoms in some genuinely creepy abodes. What’s the secret of bringing a legitimately goosefleshing haunted house to the screen?

“We worked really hard on lighting, and light levels, making sure stuff was legible enough but that you’re also slightly peering into the shadows. I think sound is hugely important, and also silence. A lot of modern media is frightened of silence and when nothing happens that’s often the most interesting moment. We tried not to do too many jump scares. We do one or two, but we try and create an atmosphere of creeping fear rather than give people heart attacks.”

Stroud’s five-novel Lockwood series launched with The Screaming Staircase in 2013 (the TV version adapts this tale but also goes beyond it, Cornish reveals). Its young ghostbusters are Lucy Carlyle, gifted with psychic powers, and Anthony Lockwood, the dashing and enigmatic founder of the only agency to operate without adult supervision. The show captures the dashing spirit of the books, quippy heroes slicing at wraiths with rapiers, but plays things commendably straight.

“It’s a very sincere endeavour,” acknowledges Cornish. “We believe in the characters and we believe in the world. Stuff like this only works if you really commit to it and decide that it’s real. I don’t love shows where the characters are winking at the camera, or there are meta jokes. I want the world to be completely absorbing and credible.

“One of the most important and compelling things for people who love these books is the relationship between Lockwood and Lucy. It’s a relationship that has an enormous fandom – there’s an amazing amount of fan art out there. It’s a sort of unrequited will-they-won’t they relationship. This is a world where young people shoulder an incredibly grave burden, at a time in their life when they shouldn’t be thinking about death, or mortality, all the things that older people have to think about, and yet here they are, armed with weapons, having to fight things that could kill them.

“But then another brilliant thing about the novels is that if you get too depressed you get more vulnerable, so the ghosts can get you if you feel too bleak. So they have to cheer each other up and make quips and jokes, for safety purposes. We just approached the whole thing as if it was completely real.”

Given the rabid fandom, getting the casting of the leads right was crucial. Bridgerton’s Ruby Stokes ultimately won the role of Lucy. “She’s the centre of the story,” Cornish tells SFX. “She’s vulnerable, damaged, kind of abused and exploited as a child, comes from a broken home, has lost her father, yet has incredible gumption and ambition and a very strong sense of self-preservation. “She has this gift that she really doesn’t want, and she packs her bags, runs away from home and sets out to London with no qualifications, nowhere to stay the night. Her powers are an expression of her emotional sensitivity. In the book it’s like teenage emotions are being made into a supernatural power.

“So we just had to find an incredible young actor who felt like she could do it, and who you believed had that inner emotional life. Before I did this I always wondered how castings worked, whether there was some super complicated methodology. But a person just walks into the room and you go, ‘Do I believe that she’s Lucy?’ Ruby was actually one of the first people we saw, and we all just went, ‘Oh, there she is! There’s Lucy Carlyle!’”

Newcomer Cameron Chapman bagged the title role. “Lockwood was much harder, actually,” shares Cornish. “We saw hundreds and hundreds of actors, and Cameron came in pretty late in the day, at the eleventh hour. And that’s equally hard, because he’s got to be sort of handsome and cool and yet really vulnerable and haunted. He’s got to have swagger and braggadocio but also be a bit of a bullshit artist. He’s like a sort of teen entrepreneur. In the ’80s everybody wanted to be a teen entrepreneur, and he’s that made flesh. But he’s also wounded and secretive and has sort of a death wish.

“Cameron had all that. Weirdly, he looks very like the illustrations on the book covers, and he wears that long coat really well. He does the charisma, he does the vulnerability, he’s a bit of a dick – not in real life, in terms of acting! – and then he can be very romantic and swoony. It’s a heck of a part for a young actor.

Out of the three main actors [Ali Hadji-Heshmati plays George, Lockwood’s second-in-command] he’s the guy who really hadn’t been on camera before, but he does an exceptional job.” But while fan approval is vital, even more key is winning the heart and mind of the man who dreamed up Lucy, Lockwood and their spook-riddled world in the first place.

“Jonathan has been very involved from the start,” says Cornish. “I formed a relationship with him in order to get him to give us the rights to the book, and then we’ve let him read every draft of the scripts. He’s come to visit the set, he’s sat down with the actors. He’s really into it and he’s been extraordinarily supportive, but sensibly he said to us, ‘Look, you go and do your thing. I understand this is a different beast, between the page and the screen.’

“But I hope, and I trust, that he has been surprised by how much we’ve just stuck to what he’s done. Because it’s really, really good. He’s provided pretty incredible material.”

Lockwood & Co is on Netflix from 27 January.

#lockwood and co#l&co. netflix#ruby stokes#cameron chapman#ali hadji-heshmati#lucy carlyle#anthony lockwood#george karim

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

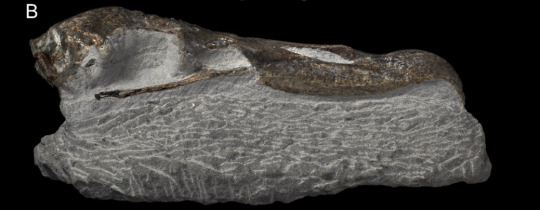

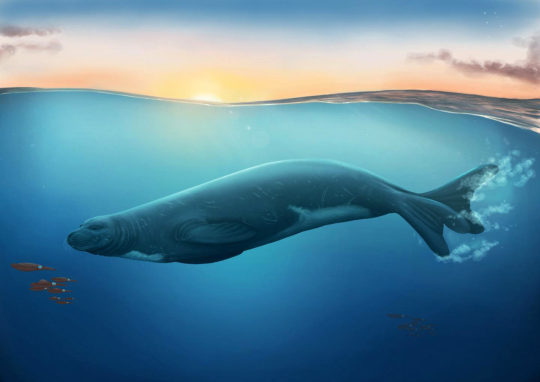

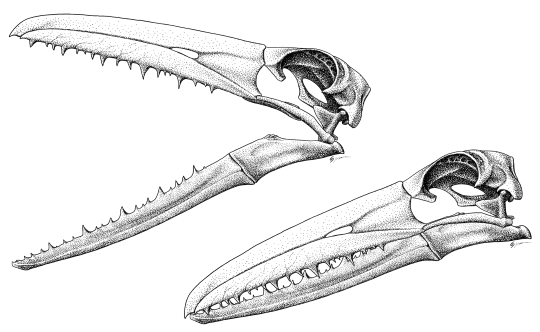

Relatively brief post because I imagine people won't care much about this one (nor is there that much to talk about). But newly described from the Pliocene of New Zealand we have Macronectes tinae, which we might as well call Tina's Giant Petrel. Known from a really well preserved skull and a partial humerus, Tina's Giant Petrel is a species of giant petrel, but notably smaller and less robust than the modern species, like these ones.

There might be two reasons why its smaller. One is simple really. Giant petrels stand out amongst their relatives for being ridiculously big, while all their closest kin are pretty small. So logically, an older, more basal giant petrel is expected to be smaller. The authors also speculate that living in warmer waters is another factor, but modern petrel ranges are huge so that hypothesis is less solid.

Even if it was smaller, Tina's Giant Petrel still lived a life that was likely similar to its modern relatives. Meaning it was an absolute beast of a bird. Modern petrels are well known to scavenge near seal colonies and penguing colonies, mob other birds, steal and eat the chicks of other sea birds and also hunt for fish, squid and crustaceans. Google "giant petrel" and expect to be greeted by birds either absolutely tearing apart carcasses or being covered in blood. Petrels look pretty metal. As it so happens, Tina's Giant Petrel was found in a formation that is in no short supply of potential prey. Eomonachus, a monk seal (illustrated by seal king Jaime Bran), Eudyptes atatu, a penguin (illustrated by Simone Giovanardi), Aldiomedes angustirostris, an albatross, various petrels and an undescribed species of pseudo-tooth bird (skull illustration by Jaime Headden) all would have given the extinct petrel a lot of options.

The paper also provides an illustration of the bird itself. Notably the artist, Simone Giovanardi who previously illustrated the penguins up above, decided to give this species darker plumage, reasoning that petrels in warmer waters tend to be darker than their relatives in the colder waters further south. The illustration shows it feeding on the carcass of a seal, probably the local Eomonachus.

Link to the paper: Taxonomy | Free Full-Text | A New Giant Petrel (Macronectes, Aves: Procellariidae) from the Pliocene of Taranaki, New Zealand (mdpi.com) And obligatory link to Wikipedia: Macronectes tinae - Wikipedia

#giant petrel#paleontology#macronectes tinae#seabird#new zealand#palaeblr#technically dinosaur#bird#petrel#extinct bird#pliocene#Tangahoe Formation

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

HARRINGROVE FLIP REVERSE IT DAY 6: Fake Dating Trope Subversion | Teen | 6.2k

DEVASTATED that this is late, but I'm happy with the final result, so it's better that I took my time instead of rushing it lol. Fun lil teacher Steve dynamic for the soul <3 Please enjoy!!

Read the Full Fic on AO3 Made for @harringrove-flip-reverse-it!

Preview below!

Billy has always had his fair share of inappropriate crushes.

An older gentleman passing through from Los Angeles, random tourists at the beach with heavy accents and eyes that he’d have liked to pick apart. One client at the auto shop he used to work at whose AC relay he had to fix, and who returned time and time again to buy coolant. Crushes that he knew were never going to happen, and that he never cared enough about to try. There were hot guys all over San Diego, though few ever truly caught his eye.

Even fewer were a part of his daily routine.

“Max, get the hell up, or you’re walking!”

“Hold on, asshole!”

Billy didn’t mind driving her around, really, but it was only September, and he thought he would lose all of his hair before May. A month since Max hit high school was a month where the pseudo-dad charade was amped up to one-hundred, and he was in for one hell of a ride until she graduated.

It was coming up on one year since it had just been the two of them. Working two jobs since he was fifteen and hiding the money from his dad was the only reason Billy had been able to afford his own place at all, let alone be deemed fit to take over as Max’s legal guardian. He was twenty-four with a clean, safe apartment and steady income, and despite ceaseless arguing that they hadn’t quite gotten over yet, Max was on his side. She would have been no matter what.

“I’m leaving!”

“Jesus Christ, Billy—“

She was still brushing her teeth by the time he revved up the car, worked the engine a few times for dramatics, and grimaced when she spit into the grass. “You are so fucking gross, Max,” he said when she got into the passenger’s seat, idly spinning the wheel of her skateboard.

“Says the guy with cigarette breath.”

Billy laughed; he couldn’t argue there.

Between the radio and forgettable chatter, rides to school were far too loud for eight in the morning, but that was their thing. It was so different from how things used to be, they didn’t care. They liked it that way. Just an obnoxious guy and his more obnoxious step-sister having the time of their lives before something went wrong again, but that would be later’s problem.