#this is in reference to a post about decolonization i saw

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

hot take but i can't stand the "look it up on google before you ask dumb questions" crowd. discussions are so important. sharing info by word of mouth is more powerful than any search engine, any youtube video or dissertation. if someone approaches you online with genuine questions like "what is decolonization" or "what is genderqueer" in response to a post you made, saying shit like "just look it up moron" is alienating someone who wanted to be taught and you shut them down.

"but nat it's not my job to educate people--" actually, it is. if you believe in a better future for everyone, it is 100% your responsibility to educate someone who asks you for help. we are a collective human species and if we're ever going to move toward worldwide harmony we must be willing to have calm and open conversations with people who don't understand.

when you say things like "just look it up online" you're closing a door of humanity in someone's face.

#this is in reference to a post about decolonization i saw#where a few white people in the replies were genuinely asking what that meant#and people were being SUCH assholes for literally no reason#educate them! they asked! they literally said 'hey not trying to start things but what does this mean' AND YOU RESPONDED LIKE THIS????#how else do you want change to happen? do you think you're not responsible for the role you play?#this is part of it! educating people who don't understand is part of the solution that YOU can do from the comfort of your home!#you are human and therefore responsible for doing what you can to build better for ALL of us. and this is THE most direct accessible option#if we can't do this then there's no hope at all

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, I'm a huge fan of your work, and I just saw that you had the link to decolonize palestine on your intro post (since you just posted a new one). I had read the website before, as a jew (who had been told different information but wanted to double check my info) and I found some of it really questionable. so I decided to research it a bit. obviously, feel free to do your own research, I actually encourage it, but here is a tumblr post that seems? to pretty well explain how wildly antisemitic that website is (i did not fully vet the post, but given what I know of jewish history, it seems to fit). I'm all for being pro-palestine and there are a ton of good resources out there, however, this website does not seem to be one of them.

obviously, it's up to you if you want to keep it or not, or even outright ignore this ask, but there has been a lot of misinformation going around, and in case this was your main source of information, I wanted to let you know that you should maybe cross reference it.

https://www.tumblr.com/arandomshotinthedark/743280738106998784/decolonize-palestine-is-a-terrible-source-that?source=share

Hello!! I read that post and some of the comments and reblogs as well as other posts by the original poster and while it does seem like the decolonize Palestine might have source issues and skip over sections of history I don’t think the post or blog you linked is any more reliable of a source. In the comments/reblogs alone I found posts which discredited major points it made, clarifying that “pink washing” is actually a term INVENTED by pro Palestine Israeli activists and that BDS discredited the Boston branch for the mapping project which is a separate thing from BDS. Those two facts, one of which the OP acknowledged in reblogs but did not change in the original post because it was “still in the realm of bad” make me hesitant to trust 100% of their information, and also because stuff like ancestral heritage/who can claim what as their homeland is contentious and Im not equipped/qualified to discuss it or evaluate it by any means. I took a look through that blog and found some of the ways it talked about Gaza and the genocide to be suspect. Specifically when they said they see the appeal of Israel because Judaism is the “dominant culture” there. They said photos of the atrocities happening in Gaza are just a way to make you angry so you’re more susceptible to Hamas propaganda and that they discourage “higher thinking.” They didn’t seem to indicate any solidly anti genocide stances which makes me think they are no more unbiased than decolonizepalestine is, just in the opposite direction. What went implied but unsaid is that anti-Zionism=anti-semitism, with which I disagree when your anti-Zionist views are based on your human rights views. I do think some anti-semites have embraced this as an opportunity to be flagrantly anti Jewish but this is not the full story of anti Zionism and is not true of most anti Zionists.

Regardless it seems like maybe that’s not a perfect website to link because it erases some relevant history but I just thought I’d let you know that blog to me is quite dog whistley. Also to anyone who might be considering it Im not interested in fighting in my inbox and I simply won’t engage. Pls do send alternative suggestions for links I could put there maybe to better sourced sites or a compilation of vetted fundraisers!! Thank you

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

"Casualties of violent resistance to violent oppression are ultimately the SOLE blame of the violent oppressor"

Hey, you know what's interesting? I've been following solarpunk blogs for years. And I never saw any solarpunk blog display any kind of apologism for violence until this past month. In the span of a few weeks, the entire eco community has completely changed its tone about violent strategies. Apparently, since everyone is hyped about violence this month, violence is on the table now.

The US government legally classifies pipeline disrupters as domestic terrorists. Now, with our newfound violent rhetoric, we can give the FBI even better reasons to call us domestic terrorists. Everyone has spent a month calling terrorism "decolonization." So now the media will have a field day portraying eco activists as terrorists any time we mention decolonization. This will make attempting to communicate with the public much more complicated and challenging. But oh well. What's done is done. Tiktok decided to associate terrorism with the decolonization movement and now we all have to live with the consequences.

Do you think the eco movement's new political attitude towards violence will help our cause or hurt it? I'm genuinely curious. By the way, oil companies are deeply integrated with the military industrial complex which requires fossil fuel for missiles. So I'll ask again. Do you think violence is a good strategy for resisting the fossil fuel empire? Should we be studying, glorifying, and emulating violent movements? Is that a form of battle that we could ever possibly win? Or is that just a way for us all to martyr ourselves?

Also, how do these violent resistance movements even get off the ground? Do they just conjure their weapons out of thin air? Or are those weapons smuggled across borders by Iran's proxy militias? Do you think Iran or some other country with proxy ambitions would smuggle weapons to eco defenders? I don't know if they would. I'm just curious how murderous violent resistance could ever possibly overlap with solarpunk.

Woah woah bestie feels like we've jumped the gun on the actual post here, you must be new to eco movements it's ok tho! Let's handle this one bit at a time 💕💕

^^^ This is the post this is referring to for context. Now let's get down to dissecting this below the cut bc YIKES this is a lot to discuss but here why dont join me for a spot of tea yeah?

Before I start to tackle this with as good faith as I can let's get some facts in order:

A) I'm from Canada, a country known by its citizens for not respecting protesters/activists. Hell, the first Premiere of Manatoba, Louis Riel was a classified Traitor and was hanged for fighting against the government for the rights of his people and we treat him as the hero he is now. In the mid 2000s a "rebellion" was lead to protect a reservation from the mounties and they stole a tank! While the news and gov ripped them apart give it 10 years and ppl cheer at the idea now. The fairy creek protests and the pipeline protests are more recent examples. They arrested and brutalized people doing nothing more then having breakfast on their own land while blocking construction. So like.... I don't have the illusion of a "peaceful" protest. Here (particularly my province) you go to a protest you simply dont expect to come home. We are functionally a monarchy, we don't have "freedom of speech" and the government was never instilled for our "freedom" or our benefit it was solely to divide up the land and to conquer.

B) this is super not new to Eco movements in particular. They've have "Eco terrorists" on record as early as the 1900s ranging from Treespiking during early logging, to throwing paint on fur wearers in the 1970s. Wiebo Arienes Ludwig is from my Province, arrested for sabotaging Oil wells and went to trial in 2000. This is definitely not a new concept to eco movements and as Solarpunk enters a more Praxis heavy punk scene instead of pure sci-fi this is likely going to be a branch of it there's no avoiding that.

"Choose peace rather than confrontation. Except in cases where we cannot get, where we cannot proceed, where we cannot move forward. Then, if the only alternative is violence, we will use violence."

This additiude comes from a reasonable place in fact here a quote from Nelson Mandela in Gaza, 1999 sums it up pretty well:

Particularly since typically they will blame a peaceful protest just as much as a "violent" one. I think "violence " is something that will happen no matter what we do. If we're as peaceful as possible, they'll still call us violent mobs just to have an excuse to crack some skulls. Even if they're just having breakfast, on their own land, they will arrest and beat them. It won't matter at a certain point bc they want to prove they can be in control.

Now don't get me wrong, I would honestly prefer to slowly adapt. To build as we take down, to show ppl the joy of this and they'll come on their own. But that only works if the goverment and the citizens are equal partners. And idk bout the states since im not from there, but here? It wouldn't matter how many citizens asked for us to go Green overnight the government would ignore that cry for the corpate money.

"People should not be scared of their governments, governments should be scared of their people" and sure this is because we out number them but they should be working for us because that's the point of a goverment in the first place.

Next is: Do I think this is a useful way to spend energy?

Yes! I do, giving something for people to do with their hands, with groups, makes ppl realize how powerful they are and how weak the system oppressing them is. Empowering ppl to do what they can where they can is always good! What ppl do with knowledge is up to them, and if they feel it's needed then generally needed.

Now to the point of weapons: no one has said anything about weapons that something like the oil companies or military would back?? All the weapons endorced by these movements are typically things like using spikes and putting them into trees, or like in France- the energy union cutting off power to the CEOs house (while giving free electricity to hospitals and poor communitis) until they reconsidered the penson plans. Or when they put BBQs on tram lines during a protest. These are weapons, but they are of the ppls trade, they are tools ppl already have not as you said "[weapons] smuggled in to eco defenders" no one is suggesting Guns? That simply won't solve things.

Organizing, communicating, and strategic planning is our best weapons.

I think that covers it, but I'm also doing this on mobile while sick so I might not have covered it all. Although i think my point is made! The final thing I'll say is, if you don't agree with these parts of the movement you don't have to participate or even look at them. Forge your own path! Others I'm sure will follow! My way will never be the only way and we are in charge of our own experiences online. This post original wasn't even tagged as solarpunk, it was under revolution so feel free to block that tag or me if you need to! Have a good day!!! /genuine

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love the way you write so in-depth and mix personal thoughts with canon facts when you write about Marvel story or character thoughts :) if you were interested in exploring, do you have any ideal scnearios for what stories Billy and Teddy might feature in going forward? I think it would be interesting to do a series exploring more about the development of the Alliance from a day to day perspective, not just when there's a giant wartime threat, getting to see what Billy and Teddy (and maybe some legacy YA characters!) look like more in their downtime, Teddy taking on a more front-facing role as a quieter guy and both of them dealing with more regular stressors/responsibilities.

I answered a similar question few years ago, shortly after Empyre, and my thoughts haven't changed much. Although Billy and Teddy have hardly been absent from comics, as some people would have you believe, they haven't really headlined anything outside of event tie-ins and those two Unlimited miniseries, which, if we're being honest, were not that great.

We've definitely gotten a feel for the types of social and political changes that they're leading, and a couple good looks at Throneworld, but there hasn't been much actual world building. There are a lot of questions that have been left unanswered-- what do their decolonizing efforts look like, what kind of governing systems are they setting up, even just a breakdown of which Kree and Skrull factions have or haven't joined the Alliance. Part of me is wary of really digging into this stuff-- if Krakoa taught me anything, it's that it's really hard for character to maintain moral integrity when you put them in this position. But they are in this position, for better or for worse, so I really do feel like we need to know.

I don't think we'll ever get a big-picture overview like HoXPoX, but you could still fit a lot of this information into a Hulkling & Wiccan title, or even just a miniseries, with an actual plot. I outlined a couple ideas in the post that I linked up top-- I think bringing the Mother entity back as a villain could be cool, and I'd really like to see Teddy and Billy pursue a better resolution with Sequoia. I feel very strongly about the parallels between Quoi and Teddy, and I feel like the generational cycles that were haunting them both in Empyre won't be resolved until they get another chance to work it out.

I definitely would like to spend some more time with their supporting cast-- newer friends like Lauri-Ell and Mur-G'nn, older Kree and Skrull characters like K'lrt adjusting to the new status quo, or even just more folks from the community that's developing on Homeworld. We saw so many interracial families, even older couples, in the background of Assault on Eden, and I want to get to know more of those people. In Scarlet Witch, Billy seemed to be working on cultural unification efforts, and I'd be really interested in seeing him working to preserve and revitalize spiritual or magical practices from Kree and Skrull cultures, probably with help from Mur-G'nn and the surviving Knights. It might be a good opportunity to refresh some of his Demiurge stuff.

Also, this will come as no surprise, I wanna see more family time! I want to see Teddy building better relationships with his siblings. I love that Carol has sort of adopted him as, like, a nephew or little brother, and that Wanda seems to love having him as a son-in-law. And, hell, if they're not gonna do anything else with Tommy, then maybe he should move to space, get a nepotism job, and start dating alien boys, too. Better than being jerked along by X-Men writers for nearly five years.

A lot of people seem to think that having Billy and Teddy get married and move to outer space was tantamount to shelving them, but I don't think it needs to be that way. With all of the Arthurian references that Ewing and Oliveira have baked in, I think it would be very easy for Teddy to continue on as a sort of hero-king who goes on a lot of very mythic adventures with Billy and the rest of their court. Personally, I like space epics when they're really just fantasy tales in sci-fi wrapping paper, and I think that a king with a magic broadsword and his witch husband are kind of the perfect characters for that. But the other thing I really like about this couple, specifically, is that you can separate them and send them off on their own adventures without damaging their relationship. Between Billy's magic and their nega-band wedding rings, they can always come back together no matter how far apart they are. You could send Teddy on a quest to deep space while Billy visits Earth, and they'll still be in constant contact. It's always going to be easy to keep their partnership-- and passion-- alive even when they're doing different things. It's a neat magic gimmick, but it also showcases the strength of their relationship!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

First candle spell results: GREAT!

it has been a couple days since I did my first candle spell asking for my art to FINALLY take off, and guess who just saw a call for diaspora Filipino poetry submissions??? (points to self) Thank you Loki Laufeyjarson, plus anyone else who was listening. I am currently almost finished with my second candle, because my anxious ass is worried about my other intention not being quite right for the method, lol.

Also I'm not sure if this is okay MAGICALLY: Near the end of their burn when they've got like half an inch of wax left, both candles have just collapsed and left a huge puddle of wax in the plate, so I just... dig out chunks of wax and feed the wick like a teeny little fireplace.

I don't know if the wax globbing out like this is an omen, or just a flaw in the candle design (candle magic people CONSTANTLY caution about "this could be a sign, or it could just be a manufacturing flaw"), but I just hate wasting the wax. :/

Like it’s not forming shapes or anything, the candle just turns into a puddle of wax near the end. It does burn REALLY cleanly after turning into a mini oil-lamp, though. Photos below for reference.

It's been five years since I could submit my weird decolonization poetry anywhere! I am picking out my five million blog posts for "Elegies to the Anito" and I'll start redrafting whatever needs to be more historically accurate. My early stuff definitely fell into the pitfalls of "all precolonial Philippine groups had tattoos" and "Mayari and Apolaki are precolonial TAGALOG deities."

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Revolutions Changed the Course of World History

Revolutions are not just moments of chaos; they are defining turning points in history. They occur when people collectively decide that the current system no longer serves their needs. These events challenge power structures, spark new ideologies, and often lead to permanent change.

Whether political, economic, or social, revolutions have occurred in nearly every part of the world. From the streets of Paris to colonial outposts in South America, revolutionary movements have rewritten the rules of society.

The American Revolution A Fight for Independence

The American Revolution (1775–1783) is one of the most studied examples. The thirteen colonies in North America revolted against British rule, driven by issues like taxation without representation and the desire for self-governance.

The outcome was not just the birth of the United States but also the spread of revolutionary ideals like liberty and democracy. The American Declaration of Independence became a global reference for the right to resist oppressive governments.

The French Revolution From Monarchy to Republic

The French Revolution (1789–1799) was both dramatic and brutal. France’s population was suffering from poverty, high taxes, and lack of political voice while the monarchy lived in luxury. Public anger turned into mass protests, and soon, the monarchy was overthrown.

What followed was a period of radical reform, but also the Reign of Terror. Still, the revolution introduced powerful ideas: equality before the law, secular governance, and the importance of the citizen’s voice. Even though France saw further instability, the revolution changed the political culture of Europe forever.

Revolutions in Latin America The Fight for Identity

In the early 19th century, many countries in Latin America fought for independence from Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule. Leaders like Simón Bolívar in Venezuela and José de San Martín in Argentina were inspired by Enlightenment thought and earlier revolutions.

These movements were about more than independence—they were also about defining cultural identity and self-rule. Though post-independence politics in many of these countries remained unstable, the revolutions marked a shift in global power and challenged European imperialism.

The Russian Revolution The Rise of a New Ideology

In 1917, Russia underwent one of the most influential revolutions in modern history. After years of suffering under czarist rule and the toll of World War I, the Russian people demanded drastic change. The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, took control, and the Soviet Union was born.

This revolution did not just transform Russia; it introduced a new political system—communism—that would influence global politics for the entire 20th century. It also led to the Cold War and the division of the world into opposing ideological camps.

Decolonization as a Revolutionary Wave

In the 20th century, a different kind of revolution swept through Asia and Africa—decolonization. Countries like India, Algeria, Kenya, and Indonesia broke free from colonial powers. These movements were often marked by both non-violent resistance and armed struggle.

Figures like Mahatma Gandhi, Ho Chi Minh, and Patrice Lumumba became symbols of national liberation. These revolutions weren’t only about ending foreign rule—they were about reclaiming land, culture, and dignity.

The Legacy of Revolutionary Movements

Revolutions reshape national identities, legal systems, and political structures. While not all revolutions lead to peace or prosperity, they all create momentum. New constitutions, civic rights, voting systems, and economic policies are often direct results.

Even failed revolutions leave behind lessons and ideas that influence future movements. Today’s calls for justice, democracy, and human rights often draw inspiration from past revolutions.

Understanding Their Relevance Today

To understand the modern world, we must study revolutions. From protests in the Middle East to democratic movements in Eastern Europe, revolutionary energy still drives change.

These moments remind us that history is not static. It is shaped by people who take risks, demand better, and are willing to change the future through bold action.

0 notes

Note

Hi I saw this post you made I’m nit sure how long ago

It noticed the girl under Somalia was wearing an Ethiopian garb. Anyway it’s just a meme but I wanted to share that in Somalia Somali women wore a long cloth around their bodies similar to what men wore except the men did not cover their breasts. When my mother was growing up in Mogadishu men and women wore their afros, danced together, played music and sang with one another. Although Somali has been coerced into accepting Islam by our neighbors. We always kept our culture and traditions. When war broke out in 1990s and more evil ideologies entered the country we do not see Somali women in traditional garb anymore.

Some imams say that Somali people are cursed for “leaving Allah” and have guilt tripped traumatized individuals into listening to them. I truly believe Islam and imams are one of the many things holding Somalia back from meaningful progress. Islam is a form of cultural imperialism that can only exist to serve the Arab interests.

Anyway

Somali women in Mogadishu still persevere and work hard but it breaks my heart to see our traditional clothes be replaced by burqa and abaaya. I have nothing against Arabs but I hold them with the same energy that I put the British or Italians. If you enslave rape and erase the history of a people and replace it with your own. You should be called out for it.

Just a Somali exmuslim giving you her life experience that you didn’t ask for. :)

Somali women in guntiino

[ Original post, for reference: https://religion-is-a-mental-illness.tumblr.com/post/661253161983623168 ]

Thank you, I appreciate you sharing your life experience. There's too much bandwidth given to silly platitudes and slogans by apologists for Islam, and particularly from those who have never actually experienced it and are just signalling how inclusive and virtuous they are.

We need people like you who have actually been there, who know what it was like, what happened and what Islam is really like from the inside, beyond the stupid slogans and hashtags.

It's notable that many of the people who stamp their feet about "decolonize STEM", "decolonize literature" and so on remain silent about "decolonize Somalia," "decolonize Pakistan," "decolonize Malaysia" or "decolonize Afghanistan" to revert them to their original cultures.

As far as I can tell, Islamic "culture," such as it is, is the quran, the hadith and enforcement of Sharia. That's why everybody in the first picture looks identical. The same way Borg drones look identical.

It's when Islam isn't quite as all-powerful, all-consuming that you see other elements peeking out - colors, even patterns. These aren't "Islamic," they seem to be aspects of the original culture sitting just below the surface.

I had a feeling the meme might not be completely accurate, but it was too hard to fully fact-check each outfit. Thanks for the correction.

#ask#ex muslim#ex muslims#Somalia#islam#hijab#hijabi#decolonize Somalia#decolonize#decolonization#islamic imperialism#religion#religion is a mental illness

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Until recently, the hard sciences proved impregnable to political propaganda and to Soviet-style boycotts and censorship. Not anymore.Op-ed.

From college campuses to medical and mental health professionals, people whose careers are rooted in inquiry and fact are falling over each other to condemn Israel for last month's defensive war against Hamas – and in dreadfully uniform language.

I don't know how to stop the lies about Israeli "massacres" when that lie has now been amplified by professors at so many universities, by the media, by students, as well as in medical and scientific journals.

Physicians, both clinicians and scientific researchers, have also become politicized. According to a surgeon-friend: "I had to quit my women physician Facebook group because of rabid antisemitism in the guise of pro-Palestinian humanism. We formed a separate group called 'physicians against antisemitism that quickly got 1,500 members."'

According to Michael Vanyukov, a geneticist and a professor of pharmaceutical sciences, psychiatry, and human genetics at the University of Pittsburgh:

"I left the totalitarian anti-Semitic Soviet Union 30 years ago...little did I know that the scientific society I would soon join in the United States—Behavior Genetics Association (BGA)...would bring back memories of my old unlamented country. I recently learned that the company's executive committee expressed support for BLM. I was shocked. Not only does BGA have no business getting engaged in partisan politics but the BLM attacks on Jewish institutions were not random...unsurprisingly, the BLM leaders also describe themselves as 'trained Marxists.' Endorsing BLM – a racist Jew-hating group – returns genetics to its ugly history page of ignorance."

To his enormous credit, Vanyukov resigned. Makes perfect sense. We are undergoing the most profound degradation of both experts and of expertise.

For example, in 2010, The Lancet, once a premier journal of medicine, blamed Israel for the alleged increase of "wife beating" in Gaza.

These researchers failed to disclose that their study was funded by the Palestinian National Authority and their data was collected by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Further, they establish no baseline comparison with domestic violence in Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia, countries which are not occupied by Israel or the West.

And amid the latest conflict, it published a letter May 19 from Issam Awadallah, of the "Shifa Medical Complex, in Gaza, Palestine." He claims that "this open-air enclave has been under siege for the past 14 years which has left the health system jeopardized by limited resources, failing equipment, and many essential drugs in dangerously low supply."

Blaming Israel for this state of affairs, when fortunes of money are given to Gaza only to disappear into attack tunnel infrastructure while Israel allows all medical imports, is unbalanced and untrue. Every failing in Gaza's infrastructure is due to the Hamas leadership, which has spent 14 years prioritizing its desire to kill Israeli civilians above the basic needs of Palestinian Arabs.

Awadallah repeats Hamas propaganda, including early, inaccurate, and out-of-context Palestinian casualty counts, including children.

The Lancet's role providing a platform for anti-Israel politics is not new. Some Lancet researchers fail to disclose that their funding comes from pro-Palestinian groups, such as Medical Aid for Palestinians and the pro-Palestinian Norwegian Aid Committee, organizations that are hostile to Israel.

What's newsworthy is that, despite pointed rebuttals by the president of the Israel Medical Association and other leading scientists – the Lancet's bias has persisted. Its allegedly "medical" and "scientific" articles routinely cite false information and in a way that conforms to the Hamas-created "lethal narrative" that's been adopted by the Western media.

Even when Lancet's authors are dealing with strictly medical issues in Gaza, they still refer, at least once, to the "oPt," aka, "occupied Palestinian territory" – and this remained true even after Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza.

After publishing an article that condemns Israel-only for suffering in Gaza, The Lancet then goes on to publish an equal number of letters which support and oppose said article. The pro-fact articles have often been published after a struggle and a delay.

What can we say about the once reliable Scientific American, which has now published an article which focuses solely on the "raging mental health crisis," but only in Gaza – not in Israel?

The article, written by psychiatrist Yasser Abu Jamei, the director of the Gaza Community Mental Health program, is accompanied by a photo of people amidst rubble, together with civil defense workers, in the "aftermath of an Israeli bombing raid." Abu Jamei refers to post traumatic stress symptomatology among Palestinian children as a result of Israel's "11-day offensive on the people of the Gaza Strip."

Abu Jamei does not mention the number of casualties and trauma created when hundreds of Hamas rockets fell short and landed on top of Gazans. He has not a word for the mental health issues in Israel due to Hamas's shelling (approximately 20,000 rockets since 2004) of Israeli cities, especially in southern Israel. Abu Jamei cites Gazan "children with poor concentration," "bed-wetting," "irritability," and "night terrors." (We know this is true for the children of southern Israel.)

Amazingly, Abu Jamei cites similarly inaccurate figures just as The Lancet did: "At least 242 people were killed in Gaza including 66 children, 38 women (four pregnant), and 17 elderly people." Not a single terrorist-combatant among them! Further, Abu Jamei saw "six hospitals and 11 clinics (that were) damaged." Not a word about whether Hamas had offices or stored weapons there. Not a word about Hamas's refusal to protect its civilians or its penchant for using them as human shields merely for propaganda purposes. In fact, Hamas is not mentioned at all.

But Hamas chief Yahya al-Sinwar admitted that his terrorist organization embedded its command centers and rocket launchers within civilian structures. It, he acknowledged, is "problematic." And as the names of the dead emerge, we find out a significant proportion of them were Hamas fighters. Hamas said it lost 80 fighters. Israel estimates the number as more than 100.

The head of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), in a striking moment of candor, said Israel's bombings in Gaza were "precise."

For acknowledging this reality, Matthias Schmale had to apologize and was removed from his assignment.

On campus, meanwhile, a wing of the union representing "25,000 faculty and staff at City University of New York" voted last week to "condemn the massacre of Palestinians by the Israeli state" and demand the school "divest from all companies that aid in Israeli colonization, occupation, and war crimes." At Princeton University, dozens of students, faculty, staff and alumni signed onto an "Open Letter in Support for Palestine."

The poisoned propaganda trickles down to public grade and high school teachers. For example, the Los Angeles Teachers Union hopes to vote on a resolution in September that would "urge the U.S. government to end all aid to Israel. As public school educators in the United States have a special responsibility to stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people... because of the $3.8 billion annually that the U.S. government gives to Israel, thus directly using our tax dollars to fund apartheid and war crimes."

Quite ironically, the Los Angeles Board of Education has just made a $30 million deal with Apple to distribute iPads to its students. Yet, a major supplier is using "forced labor from thousands of Uighur (Muslim) workers to make parts for Apple products." Those Uighurs also are subject to torture and held in internment camps where they are "indoctrinated to disavow Islam" by the Chinese government, a new Amnesty International report finds.

No boycott of China is proposed by the union.

The San Francisco teachers union has already called for "essentially the same actions" targeting Israel.

More than 20 years ago, a handful of us saw the tsunami of anti-Israel propaganda coming our way.

We were not heard. Actually, we were heard, and therefore, we were defamed, mocked, censored, and forced to publish in ever-smaller venues, knocked out of the mainstream media. Some of us were fired from our academic jobs.

And now the tsunami is upon us. The incoming president of Psychologists for Social Responsibility of the American Psychological Association is Lara Sheehi. She specializes in "decolonization" and, although she is not an expert in Middle East history, geography, or religion, describes herself as strongly pro-Palestine.

As usual, the propaganda has swiftly unleashed mini-pogroms and major pogroms against Jews around the world. In the diaspora, civilian Jews have no IDF to defend them.

Kathryn Wolf published an article in Tablet in which she eloquently described her "screams" about antisemitism in Durham, N.C. falling "on deaf ears." She concludes, correctly:

"If I have learned anything, it is this: The cavalry is not coming. We are the cavalry."

Phyllis Chesler is an Emerita Professor of Psychology and Women's Studies at the City University of New York (CUNY), and the author of 20 books, including Women and Madness, and A Family Conspiracy: Honor Killings. She is a Senior IPT Fellow, and a Fellow at MEF and ISGAP.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chihiro Fujisaki and Gender Identity

Ok before I get started because I don’t want to get fucking barked at for attempted analysis and interpretation let’s run through disclaimers.

I’m posting this purely as an exploration piece; I am not telling you how to interpret Chihiro. I am telling you about how my exploration of her character and how it led to further understanding of gender in Japanese media.

I am American and monolingual. Despite my efforts to understand gender identity in Japan, I lack firsthand experience and have limited access to translated resources. So there’s cultural gap, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The game changed in localization, it makes sense the interpretation does too. Let’s observe that.

Also I will be using she/her pronouns for Chihiro but really this piece is less about Chihiro and more about gender and social science.

Tws: slurs (censored on this post, uncensored in linked articles), additional trigger warnings throughout

Introduction

About a month previous to the time of writing this, I saw someone say that labeling Chihiro Fujisaki as a transwoman was white washing her identity by forcing Western gender ideals on her. So of course I thought “well now that’s not good” so I set out to broaden my understanding of transgenderism in Japan to see how it interacts with my mainly American view of gender (that I am actively working to deconstruct and decolonize).

A Rundown

Gender nonconformity and transgender identity in Japan is.. rough. It’s heavily controlled by doctors and really the only way to get anywhere even in social transition is to get diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder (GID)*. So even if trans people in Japan don’t view their identity as a disorder, to exist in the system it is preferable to label it as such in many cases.

[*tw for forced sterilization]

The history of genderqueer identities is also a bit muddy, which isn’t surprising considering the same holds up in America. Oftentimes cross dressers are lumped in with trans people, because well we do associate with each other historically (see: drag culture in America*). There’s a history of homosexuality, cross dressing, and even (although minimal) lesbianism, which is often excluded from a lot of queer history because y’know, misogyny.

[*tw transmisogyny]

There’s also been a significant influence from the West in gender identity, as many modern terms originate from English. But other than that the culture is very different, such conflict being observed here. The social climate is not kind* to any sexual orientation or identity minorities.

[*tw suicide, non-consensual outing]

So there’s two ways someone could interpret Chihiro. First is well, as a “tr%nny” to put it accurately (albeit unfortunately) to the connotation of the term. This is the, while offensive, quite common translation of “nyūhāfu” (new-half) which was is now considered more of a job title than an identity. It’s falling out of use with younger people as it’s commonly associated with sex work and night life. Note the word also means “lady-boy”, which will be relevant in a moment. This term is still fairly common in reference to transgender people, but “toransujendā” (transgender) is steadily rising in popularity.

You can read more about LGBTQ+ terminology in Japan here and here.

The more common understanding of Chihiro is as “otokonoko“ which has a few different translations but the one you’re probably most familiar with is “tr%p”. Like nyūhāfu, it can translate to the similar “male daughter”. There’s some wordplay involved that is elaborated on in this article which may help, and it also elaborates more on otokonoko as a trope and it’s role in Japanese media.

Nyūhāfu or Otokonoko

THH was released in 2010 in Japan, and new terms for sexual identity and sexual orientation weren't added to Kojien dictionary, the most respected Japanese dictionary in the country, until 2018. So comprehensive transgender representation is likely out of the question.

There’s also the fact that most Japanese media (at least television) portrays LGBTQ+ individuals as a gag, which we’ll circle back to when we talk a little more about otokonoko and interpretation of the subculture.

Otokonoko originated in the early 2000s as an internet culture, but also links back to earlier male crossdressing in Japanese history. With limited information beyond the trope, it’s unclear if people who participate[d] in otokonoko actually had any overlap with genderqueer people.

There’s more information and a longer article, but it’s all in Japanese. From what I was able to understand though, otokonoko can overlap with transgender people and by some is even seen as connected to trans culture, but it is not inherently transgender. When portrayed in fiction, they are usually not transgender. In real life transgender people can be grouped with otokonoko though its unclear if that’s purely due to misconception or if it’s fluidity in identity.

So... Are Otokonoko Trans?

In a literal sense (regarding fiction), no. In interpretation and theoretically... yes? Maybe? Sometimes?

Otokonoko does hold as it’s own trope and identity, but whether or not it’s meant to associate with transgender people in origin is unclear. By that I mean is it’s possible the trope first occurred as a way to make fun of transgender people or to display them in a way that is vulgar enough to be acceptable for mainstream entertainment. From what I can tell though, it doesn’t currently hold direct association with trans identity in Japan, but the same is said of other gender performers [see previous article].

Before I Go - One Other Side Note

So I’ve run into the problem before where insecure trans people get pissed at me for associating crossdressing with trans culture because they think validity is a finite resource that I’m trying to steal, so here’s some sources talking about their tied history <3

Also, no, I am not implying being trans is the same as being a crossdresser nor am I saying trans queens are crossdressers (unless they identify as such).

https://jmellison.net/if-we-knew-trans-history/ru-please-trans-women-have-been-a-part-of-drag-for-decades/

https://www.them.us/story/how-drag-queens-turned-against-the-trans-community

Also Fuck You RuPaul.

If that’s not enough for you, I can also personally attest to crossdressing being a safe space for me to sort out my gender. And I still am a crossdresser. So yeah. The experiences aren’t mutually exclusive.

Conclusion

So whether or not you headcanon otokonoko characters as trans probably doesn’t matter, because one could argue that someone could be both. Otokono are mainly observed in fiction as trope, so there’s a lack of information (in English at least) about how otokono would interact/mesh with transgender identities in real life Japanese culture. Otokono has it’s own rules that usually involve cis people and comedy, but that’s just surface level information that could experience various potential contradictions and nuances based on individual cases.

There are three complex topics converging here, which is what makes this conversation so messy.

Cultural differences between America and Japan.

Gender identity (bonus points for it’s relationship with crossdressing subcultures to make it even more complex).

Those two aspects combined will create a completely different understanding of a character for the audience.

Wait Wait I Feel Like We Skipped Something- So Chihiro IS an Otokonoko?

Yeah. I mean, technically speaking yeah. From a formalist lens she is not trans. But that doesn’t mean reader interpretation can’t view her otherwise.

Chihiro Fujisaki will mean something different depending on the lens of the viewer. And that’s NOT A BAD THING. It’s just something to be aware of.

This thread here has a great discussion about Chihiro, justifying the role she plays as an otokono in the game. I highly suggest expanding each response because they make important points.

And this blog post here *provides a great insight on why many trans players from America relate to Chihiro as a transgender character (and have strong opinions about it).

[*tw violent transmisogyny]

I think these two views can coexist and you get the most out of Danganronpa’s portrayal of gender identity by understanding the different effect Chihiro Fujisaki had on different audiences.

I used to be a pretty diehard transwoman Chihiro fan, and while I still like the headcanon and am slightly uncomfortable with he/him being used for Chihiro (see: previously linked article about Chihiro and American trans perception), this research has helped a lot in understanding the variety of headcanons that exist for her! It’s definitely also made me a lot less critical of different interpretations of her character and other otokonoko characters.

This project ended up being a lot less about Chihiro herself, and more about gender identity and performance and the roles they play in society, but I’m not mad about it. I hope this also gets you thinking.

#chihiro fujisaki#trans#Danganronpa#trigger happy havoc#transgender#gender identity#gender performance#think piece#character analysis#pocket long posts#literary theory#queer literary theory#i wrote this before I actually got to literary theory in school sorry#I might revamp it another time now that I have a more organized idea of what im talking about#den's chatter#dr crockpot

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I hope you're well. Do you have any recommendations about where to start with decolonization theory? I've heard a bit about it but nothing substantial.

Hey, thanks for the question. Before I start rambling, I’ll just give a really short, blunt response: Despite all the jargon-heavy academic content written about decolonization, especially as a trend in the past 15 years, I think that the way to learn about decolonial thought and practice is to read the work of people living in the Global South; the work of marginalized environmental activists and agricultural workers, especially in the Global South; and the work of Indigenous scholars, knowledge holders, and activists who are explicitly willing to share their knowledge with non-Indigenous people. That said, I’m not too well-versed in technical decolonial theory per se, and instead I try to read more of the ecological/environmental, social/anthropological, and activist writing of Indigenous people and people from the Global South, what you might call decolonial thought. Rather than focusing on the technical theory and writing of wealthy Euro-American academics, I prefer more radical decolonial writing that integrates local/Indigenous cosmology, environmental knowledge, and ecology alongside the social and political aspects of radical anticolonial resistance. Something that I’m really interested in, regarding decolonial thought, is the importance of Indigenous and non-Western cosmology (ontology, epistemology, worldviews) because these ways of knowing actually provide frameworks that stand in contrast to extractivist thinking, suggesting alternatives that could be implemented. So, below I’ve listed just a couple of the most accessible authors that I’ve been reading recently, and I’ve split recommendations into four categories: (1) Indigenous authors writing about sovereignty and ecological consequences of colonialism; (2) technical decolonial theory and Indigenous resistance; (3) decolonial theory and ontology; and (4) synthesizing technical decolonial theory with writing on Indigenous worldviews and environmental knowledge. This definitely isn’t meant to be an extensive or definitive list of resources; and I know other people might have some better or different recommendations to make. But I hope this helps, if only a little bit, as an introduction!

-

Y’know, I think there’s a tendency among a lot of Euro-American academics to make the concept of decolonization much more mysterious, obtuse, and complicated than it needs to be; there’s an awful lot of discourse about metaphysics, ontology, and other intellectualized aspects of decolonization that are probably less important right now than concrete actions like reforestation and revegetation projects; healing soil integrity, health, and biodiversity; dismantling monoculture plantations; ending industrial resource extraction; ending de facto corporate control of lands, especially in tropical agriculture; allowing local Indigenous autonomy; preserving and celebrating Indigenous languages and ways of knowing; etc.

So, I’m not all that knowledgeable with technical decolonial theory. Instead I mostly just try very hard to read the environmental, anthropological, activist, etc. writing of Indigenous and minority communities, people from the Global South, and Indigenous traditional knowledge holders. Often, this kind of writing doesn’t always take the form of “theory.” A lot of decolonial theory - that I’ve seen, at least - is concerned with discussing trends/currents in academia and Euro-American discourse about the Global South. (In other words, a lot of decolonial theory written by white authors seems more concerned with talking about what decolonization means for academia and discourse, rather than actually exploring the worldviews of Indigenous peoples and the Global South.) Instead, the kind of stuff that I try to read explores Indigenous and non-Western resistance, community-building, and ecology; and so the resources that I recommend might not qualify as decolonial theory but they are decolonial, if that makes sense?

In my experience, some of the works that best demonstrate or embody decolonial thought are not works of theory, but are instead works of social history, nature writing, natural history, or works that explore bioregionalism, food, and local folklore. I also like to note that there is a trend among activists and scholars in Latin America to use the term “anticolonial” instead of “decolonial” or “postcolonial.” These latter two terms might imply that existence or identity in the Global South is doomed to always be defined by its relationship to Europe, the US, or imperialism generally. However, “anticolonial” might connote a more active role; you may still suffer the effects of imperialism, but you’re also an active opponent of it, living and thinking outside colonialism, with a unique worldview that exists autonomously rather than being defined always in reference to colonial actions or standards.

Indigenous authors writing about sovereignty and ecological consequences of colonialism:

So here are a few Indigenous scholars that I read, who write not just about decolonial thought, but also about place-based identity, environmental knowledge, and how decolonial theory can often be Eurocentic:

– Zoe Todd: Metis scholar and environmental writer, who famously criticized academic discourse about decolonization for itself being Eurocentric and colonial; here’s a nice interview (from 2015) about decolonial theory, where Zoe Todd criticizes Western academics and the ontological turn in anthropology.– Kyle Whyte: Potawatomi scholar, who writes about Indigenous sovereignty, Indigenous food systems, colonization, contrasts between Indigenous and Euro-American worldviews, and preservation of Indigenous enviornmental knowledge; here’s a list of Whyte’s articles and essays, most available for free.– Robin Wall Kimmerer: Potawatomi ecologist, bryophyte specialist, and educator, who discusses contrasts between Indigenous and Euro-American ways of knowing; here’s one of my favorite interviews with Kimmerer.

Technical decolonial theory and Indigenous resistance:

And here are two recommendations on more technical anticolonial/decolonial theory. These texts are both a bit dense:

– Boaventura de Sousa Santos wrote a wonderful work of decolonial/anticolonial theory and thought, titled Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide (2014). This work is a bit technical but very interesting and thorough, and explores how a major function of imperialism is to deliberately dismantle Indigenous worldviews, ways of knowing, and environmental knowledge, to replace Indigenous ecological relationships with “extractivist” and “industrial” mentalities.

– Arturo Escobar wrote a good work of anticolonial theory in direct response to de Sousa Santos’ work; Escobar’s text is called Thinking-feeling with the Earth: Territorial Struggles and the Ontological Dimension of the Epistemologies of the South (2015).

Both of these texts and authors explore the Global South’s active resistance to industrial/extractivist worldviews; they both also largely focus on Latin America and reciprocity, communal relationships, agroecology, and active resistance in Latin American communities.

Decolonial theory and ontology:

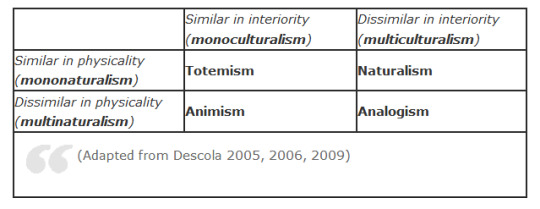

The ontological turn in anthropology is kiiind of a manifestation of decolonial theory, though it’s kind of problematic and often Eurocentric, popular among wealthy academics. The Metis scholar Zoe Todd, referenced earlier in this post, has written about the problematic aspects of the ontological turn. The ontological turn was big news in academia around 2008-2012, happening alongside the rise in popularity of Mark Fisher, “capitalist realism,” and Graham Harman’s object-oriented ontology. Basically, I guess you could summarize the ontological turn as an effort to decolonize thinking in anthropology departments of Euro-American universities, to better understand the the worldviews/cosmologies of non-Western people. Here’s a summary by environmental scholar Adrian Ivakhiv, which references the role of Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Phillipe Descola, two anthropologists working adjacent to decolonial theory.

Synthesizing technical decolonial theory with writing on Indigenous worldviews and environmental knowledge:

– Phillipe Descola: A renowned anthropologist whose work inspired much of the decolonization trend in US anthropology departments and the ontological turn in anthropology; Descola’s work deals with epistemology and ontology (so it’s often pretty dense) and takes a lot of cues from the work of Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, the Brazilian anthropologist who popularized the study of Amazonianist cosmology. Other Euro-American anthropologists who write about technical decolonial theory: Bruno Latour (kind of problematic); Isabelle Stengers.

– Eduardo Kohn: An anthropologist focused on decolonization and Indigenous worldviews; Kohn also takes cues from Viveiros de Castro and Descola. Kohn authored How Forests Think, which is a study of Indigenous Amazonian worldviews and how Amazonian people perceive nonhuman living things and the rainforest as a community. You can look up interviews with Eduardo Kohn

– I don’t know if you saw this post I made recently, but it shares a fun publication called The Word for World is Still Forest, which is an exploration of the cultural importance of forests from decolonial and Indigenous perspectives, and it’s a good example of decolonial theory being explored by visual artists, geographers, poets, anthropologists, and activists.

-

So, these are just the first examples that come to mind. I’m sure other friends/readers/followers might have some better recommendations. [ @anarcblr ?]

Often, I feel like a lot of technical decolonization theory is written by white professionals and academics, and I, personally, don’t think it’s important to have a white academic acting as a “middle man” whomst “translates” the thinking of Indigenous theorists and people from the Global South. In my experience, there’s a lot of “decolonization theory” content in journals, books, etc., over the past 20-ish years, mostly written by white academics who seem to have just recently “discovered” the “utility” of decolonization theory for “improving their field” or something. Discussing the “utility” of Indigenous knowledge is itself a kind of colonialist way of thinking, since it sees the knowledge as profitable or valuable or something to be employed like a machine, a way of thinking that is itself extractivist. (I’m not anti-intellectual, and anti-intellectualism is a problem, especially in the US. But I’ve not really found academics willing to just straight-up say radical things like “capitalism has to be confronted if we’re going to be serious about decolonization.”)

Like, they write about decolonization as if it’s major benefit is its practical/pragmatic application to improving science, metaphysics, conservation, or climate crisis mitigation. One example of this behavior is a huge amount of headlines in mainstream US news sources and environmental magazines, from late 2018 and 2019, that say some version of “Indigenous knowledge may be the key to surviving the climate crisis” or “planting trees might be the single best defense against global climate collapse, and Indigenous peoples’ knowledge can help us implement it” And this just doesn’t sit well with me. Firstly, because it frames Indigenous knowledge as an inanimate resource to be “tapped,” appropriated, employed, “put to use.” And secondly, because this not news. This - the role of vegetation and healthy soil microorganism communities in mitigating desertification, biodiversity loss, and local adverse climate trends - has been well-known to Indigenous peoples for centuries or millennia, and has also been very well-known to Euro-American environmental historians and academic geographers for decades.

I guess I’m saying that the current Euro-American discourse of decolonization has a lot of issues.

Anyway, the theory that I personally like best isn’t too academic or jargon-heavy; I like the work that which synthesizes human elements (anticolonial; anti-imperialist; anti-extractivism; anti-racist) with ecology (cosmology and folklore; traditional environmental knowledge; place-based identity), since ecological degradation and social violence and injustice are inseparable issues, and this is an interconnected relationship that decolonial theory and Latin American worldviews seem to understand very, very deeply.

And, I guess another element to the kind of decolonial writing that I enjoy is the importance of Indigenous and non-Western cosmology (worldviews, epistemology, ontology, ways of knowing) to providing alternatives to imperial, colonial, and extractivist mentalities. This is how decolonial thinking is not just about finding ways to defend against further imperial violence, but also proactive in promoting healthier alternatives that can be implemented.

I hope that some of these recommendations are useful!

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

DECOLONIZE EARTH

I was born belonging to a field and a forest edge until civilization stole my being and ‘developed’ my home. Years later I was still a teenager when I stole back some summertime alone in noncivilization, a juniper knoll over a lake. Each dawn a mourning dove perched on the branch above greeted morning cooOO-woo-woo-woooo. For years after, work-consume city culture swallowed my life. One day I opened my city door shocked to find a lame mourning dove on the deck. My mind wondered on which human construct caused the collision. My inner self, original self, truest self, arose from artificial hibernation. My animal being compassionately watched over this other animal being through days and nights as her body healed. When she found strength to fly away, I mused mystical meaning of this visit from my past converting this deck artifice into wild refuge. Too quickly I distracted back into illusory life.

I moved to another urban area, this one with sloped landslide-prone ‘parks’ astonishingly let be as withered wildlife habitat. They were dumped, fragmented and encroached into by domesticated humans and their invading tag-along plants and animals. These wild lands civilization rejected for ‘development’, however degraded, became my authentic life. In forests dominated by conifers, much taller and widespread than junipers, in swaths along saline shores, my animal being reawakened. This time I heard nature’s cries and responded wholly, learning ways of tending the wild. Indigenous plants are the locus of thriving wild, so I observed their characters, their pleasures and aversions, movements and constraints, givings and takings, shape-shifting communities and ranges, and what assists them in their struggles with invading colonizers.

My assists aligned with the science of restoring ecology, but my emphasis on caring observations of everything wild awakened a connection deeper than anything science. I didn’t see my change coming, or plan it, though I was ready for it and accepted it fully. Despite reports as increasing in population, the only time I saw a mourning dove since moving to the land of towering conifers was on a walk through a human altered environment. Crows harangued with raptor-warning caws from electric lines above her lifeless body on roadside lawn. Blood dripped from her beak as a hawk held her still with a talon to rip open her breast. My mind wondered if humans’ ‘development’ vastness created space too open, stealing cover that serves hawk the advantage. After years of lying dormant inside me, mourning dove’s call intuitively sounded, not entering through my ears but emanating through my voice. cooOO-woo-woo-woooo

Mourning doves are so uncommon in the forests that I began using the call to communicate with habitat restoration friends working within sound range, drawing selective attention of others familiar with expected bird calls of the place. I varied the emotionality of the call to signal meaning, from “I’m here now” to “Come check this out!” Now that my project focuses on inviting return of extirpated indigenous plants, each time I cast seeds, bury rhizomes or stake stems into a habitat in which the species once thrived, I sound the mourning dove’s call selectively to all others who live in this home to announce the plant’s presence. Then I leave the wild alone to reacquaint.

During a recent training on how nonNatives can ally with Native Americans I learned a lesson not taught: restoring wild ecology is the deepest way colonized humans can decolonize. Returning a place toward its pre-colonized state is rewilding both the place and the rewilder’s self. This training however centered on identity politics, which I see as correlational to and part of the birth of human colonization: civilization. Humans’ domestication and domesticating is colonization’s core, which is wild life’s core problem. As this training revealed, civilized humans wage futile fights paradoxically against civilization’s hierarchies. Further, they see the heinous power they hold over nonhuman animals as worth the price of civilizations’ ‘progress’, from world takeovers much farther back than humans’ most recent post-stone age globalization.

Post-stone age colonization removes us from wild ways of knowing, for example, replacing childhoods in connection with nature to childhoods enclosed behind walls studying ways of controlling nature. Humans’ stone age colonization enculturated humans away from primal ways of living by unnaturally positioned themselves as Earth’s top predator as they expanded. This most noticeably manifests in the shifting human foodway from biological herbivores to advantageous omnivores. From foraging to dominating by organized hunting.

Past shifting human lifeways of a place creates a curious predicament in restoration ecology. The restoration reference point of a place resembles the most recent phase diversity of life was thriving there. In most cases that phase was a settled period after the habitat was markedly altered by human colonizing actions impacting the environment. If nature restorers’ reference point for a place was shaped by actions such as old growth forest burns set by some to open gaps for hunting opportunities, how do they account for these missing human interactions that shaped the ecology?

For thousands of years humans have decided how all life live, further which life and entire species live and which die. Imagine a pre-human colonization wildlife map. Imagine wildlife timelines fluctuating at points of first human contacts, how interconnections transitioned from wild dynamics to hierarchies under human control. Species deemed appealing to human usefulness or preference moved to the top, while any species unwanted was marginalized and risked extermination. Imagine nonhuman animals hosting a training for humans on the history of their oppression and exploitation, complete with stories of their slaughters and species extinctions, as well as their resistance stories and strategies, with an invitation for you to support them.

An invitation to ally with nature, to liberate Earth from human colonization, would center on rekindling primal relations with others we now oppress. A training to ally with wild life would confront humans’ colonizing propaganda, stereotypes and defenses with countering truths. Not all past humans hunted, many remained foragers, just as many humans today as young as toddlers instinctively choose to refrain from animal exploitation. Humans’ reign over others is not natural, nor is humans’ consuming animals part of the ‘circle of life’, no matter how much ‘thanks’ is expressed. The heart of wild interactions and relations is not using others as resources, but thriving community wild life. Other animals do not mystically ‘offer’ themselves for consumption, whether or not ‘every part’ of their body is used. They are not ‘food’ animals brought into existence for us to live, but wild animals often bred into unnatural form by imprisoning civilized hands.

Truth is, humans are an incredibly adaptive species with great abilities to change toward sustainable lifeways, if they would take steps in overcoming their speciesism. In a training to ally with nature, they would get a checklist to test their speciesism, akin to Dr. Raible’s checklist for antiracist white allies. *I demonstrate knowledge and awareness of the issues of speciesism. *I continually educate myself about speciesism. *I raise issues about speciesism over and over, both in public and in private. *I identify speciesism as it is happening. *I take risks in… Like civilization, speciesism is so rampant, so ingrained in all of everywhere, the chasm feels unbridgeable. But going hand in hand with civilization, not facing the daunting task of bringing down speciesism means humans’ own demise.

Like all oppressions, the dominant group benefits leave tracks of misery seeming so unnecessary in retrospect. Bringing down the old ways gives space for the new. Humans can identify and breach the cracks in the cycle of systematic oppression of nature at each step. The generated misinformation and propaganda. The justification for further mistreatment. The institutions perpetuating and enforcing speciesism birthed in civilization. The internalized dominance and feelings of superiority. The internalized oppression via subscribing to the narrative. The cultural acceptance, approval, legitimization, normalization. The systemic mistreatment of nature. Whether targets are specific or broad, planting seeds in the hearts and minds or immediately effective actions, opportunities abound.

While the path of the new way does not and cannot have an overarching plan, some potential actions of the new way can be envisioned. Collectively reduce human population. Give back land for indigenous rewilding. Restore habitat toward times of last thriving ecosystems, that is pre-European colonization. Invite the return of extirpated species. Where possible, reintroduce human-removed indigenous top predators. Sanctuaries for liberated animals bred into domesticated forms who cannot go feral or co-adapt into habitat community. Shrink animal agriculture first, plant agriculture second. If possible, skip over architecting food forests & permaculture with humans at the center and return straight to foraging. Draw from sciences without bias barriers to wildlife’s innate right to live on their own terms

Humans will either soon drive themselves to extinction with many others, or they will decolonize themselves by mutualizing their alliance with Earth’s living communities. Hope lies in releasing mass delusion, in bringing down speciesism and civilization that dragged it in, in assisting Earth’s transition into a rewilded state that includes the compassionate feral folio-frugivore human living in symbiosis with others. Not utopia, but liberating Earth from human domestication. The transition has already begun, and all humans are invited to join. cooOO-woo-woo-woooo

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jargon Tourettes

Top 10 Overused Jargon 2018*

Overused Jargon (OJ) tells us what the media savvy think is relevant, useful, and popular. In some ways jargon is a gatekeeper, a cliquish code to separate those who get it from those who don’t. My selection is indicative of general trends with a bias towards the African arts and development worlds. These words are not sacred, and they need to be satirized and tested so that they don't become enshrined, unconsidered, shallow symbols of in-group identification. Perhaps this can help to prevent the alienating and misleading effects jargon can have. Consider this a satirical vaccination against sophistry and let’s hope for a better tomorrow where cryptic condescension gives way to shared comprehension.

Innovation

The elder states-person, the OG of OJ. 'Innovation' has somehow managed to remain atop the charts in spite of becoming a caricature of itself over the years. It also feels like we've been innovating for decades now, we might be due for some consolidation and refinement. Innovation's longevity is a product of its flexibility (it can mean many things), its vapidity (it can mean nothing), and the novelty-chasing tech-centric culture du jour.

Eg. “The Innovation Initiative was initially based on the premise that all change is good. It later became The Department of Unexpected Consequences.”

Engagement

Whether it's measured in links clicked, or viewing time, engagement is usually a euphemism for 'keeping an audience's attention more deeply for longer periods of time'. There's nothing necessarily wrong with this in itself, any creator wants their work to be engaging. Unfortunately, truly valuable engagement is about quality of experience, not just stats. It also turns out that trolling, click-bait, bot-baes, and other tricks work just as well, if not better than creating compelling, meaningful content - assuming that pure statistical engagement is the goal here. Even eliciting hate and outrage in the audience is preferred to eliciting the dreaded indifference.

Eg. “Once middle-aged super-users started gouging their own eyes out the e-ghetto slum lords sought to maintain high levels of user engagement by injecting digital crack directly into user’s blood streams via a fleet of nano-drones.”

Unpack

It's not mansplaining if you preface your long-winded speech with, “let me just unpack that before we move on...” Poetic allusions to heavy baggage give this bit of OJ an ironic edge. Have you ever felt burdened by verbose unpacking? I have.

Eg. “As the morning's first speaker, I unpacked the topic of discussion at such length the moderator had to stop me so we could break for lunch.”

Girl Child

A steady climber over the years. Indicative of gendered global SJW trends, the Girl Child™ is now the holy grail of target demographics and beneficiaries. The term is particularly popular in development circles where its feminist paternalistic slant strangely fits the industry-wide vestigial-colonial vibe. Besides, 'Starving African' just feels so 1900s.

Eg. “Emergency! The ship is sinking! All women, girl children, and gender-non-binary-human-meat-sacks may board the life rafts first! The rest of you can fuck off.”

Decolonization

An up and coming term with the potential to rise even further in the charts. Its ceiling depends mostly on whether or not it remains a trophy word spoken in seminars and galleries. If it matures into active programs that directly enact de-colonial agendas the word may have to share the stage with other relevant but unsexy terms like 'supply chains', 'resource redistribution', 'local staff', etc. It also has immense potential as a linguistic camouflage for bad art. Those who criticize 'de-colonial art' may easily be shamed and dismissed as colonists, apologists, or sympathizers. The thoughtful critical landscape is pretty thin so similar strategies may be applied with other identity-centric words to shield questionable work from honest criticism.

Eg. “The former farm invader liberator had diversified his portfolio to include decolonizing luxury resorts, one free vacation at a time.”

Afro-Futurism

This once exciting term is at risk of becoming nostalgic dross due to how much it's been bandied about in African arts circles. It's a victim of its own success. A tell-tale marker of when a term becomes OJ is that it inspires satire of a higher quality and awareness than sincere works.

Eg. “Afro-futurism enables us to imagine a future where our collective conscious, aka Wakanda, has morphed into a touch screen cell phone that purifies drinking water, and cures HIV.”

Beneficiary

If a heroine feeds a starving village and no one sees it, did they all just starve instead? There can be no benefactors without beneficiaries and they must be documented, preferably smiling in situ despite the squalor that surrounds them. As a citizen of a country where most adults are unemployed I'd argue that employed development professionals should also be counted among the so-called beneficiaries. There's no shame in getting paid if you do a good job.

Eg. “As I saw the tears of unrestrained joy flow from the beneficiaries' eyes I knew my genocidal ancestors' crimes had been forgiven in full. If anything, I'd earned some extra credit for future generations.”

Toxic Masculinity

The shortest way to describe a Tarantino movie. Some people seem to believe that all masculinity is toxic, but we unfortunately don't have a popular catch phrase for them yet. Many men try to camouflage themselves by borrowing the props, costumes, and behaviors of their perceived superiors, essentially flaunting their overseer's whip. You know it when you see it.

Eg. “The game show host gave Chloe a choice between experiencing an unspecified act of toxic masculinity and ingesting mercury; Chloe chose mercury.”

Curate

Curating used to happen in museums and galleries, ideal environments for showing others you have better taste and ideas than the unwashed masses. Now it's everywhere. Seemingly overnight the jargoneers stopped simply 'choosing things to sell in their shops' and started 'curating bespoke collections for their boutiques'. It’s the same thing, but with bougie overtones.

Eg. “The fuel station manager curated a collection of limited edition off-white sequined jerrycans for his most discerning customers.”

Interactive

I know what this word means to me, but after being assaulted by many misuses, and making many concessions for the sake of conversation and civility, I no longer have a clue what it means to the general public. I do know that in digital art circles it signifies 'cool', 'cutting edge', and 'dynamic'. At worst I've seen it used to describe a fixed work that people looked at without influencing in any way.

Eg. “The curator of 'The Bricks are Present' was puzzled when the audience didn't transform into pro-bono builders despite the presence of the interactive bricks in the space.”

Conversation

Habitually misused by talking heads who would have you believe their one-sided monologues somehow constitute a conversation.

Eg. “Popular Instagrammer @Philosothot69 had an ongoing conversation with her thirsty horde of male fans wherein she mused about being more than just her looks while they sent her flaming eggplant emojis and tagged their friends.”

Problematic

Increasingly just a trendy way to add an air of faux-academic objectivity to ones' personal opinions and preferences. A newb might say, 'I didn't like District 9', but a true OJ guzzler will declare that it was problematic. Like many such words its rise began sincerely within relevant contexts, but it has since been taken up cynically in other contexts. In a few years it may just be something glib people say about petty things in the ceaseless quest to sound woke.

Eg. “When eventually Phil voiced his critical opinions about the concept sketches for the mural, Kuda quickly shushed him, reminding him that, generous funding aside, his uppity whiteness was problematic. Thus Kuda attained her black belt in the dark arts of juggling feminism and racial politics.”

Triggered

Triggered once referred to panic attacks that traumatized war veterans suffered after hearing loud noises or other shocking stimuli. Originally rooted in early studies of Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or shell-shock as it was known then, triggered can now be trotted out to describe how you feel when someone is wearing the same outfit as you at the grocery shop.

Eg. Overzealous auto-correct and my aversion for proof-reading ruined my broadcasted Annual Christmas Party invitation message. I got so triggered I like literally died.

* by 10 I meant 13.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tainá Müller about her real-life heroine: "I want to play women who help other women"

by Renata Maynart | Oct 16th, 2020 | Interview

As the leading actress of "Good Morning, Veronica", she celebrates the possibility of uniting work and personal concerns

While talking to Revista Donna by phone, the actress Tainá Müller made a restrained outburst.

- I was sure that 2020 would be my professional year - she said, referring to the jobs postponed by the pandemic.

But, a few days later, her protagonist in Good Morning, Veronica, a series inspired by the book by Ilana Casoy and Raphael Montes, would confirm her pre-coronavirus foreboding. Netflix's production was among the most watched in Brazil in early October. And she took her name to the center of a debate around a theme that she has already been a spokesperson for on social media: “Brazil is a brutal country to be a woman.”

PHOTO BY GUSTAVO ZYLBERSTAJN