Text

Presenting Petra Cortright

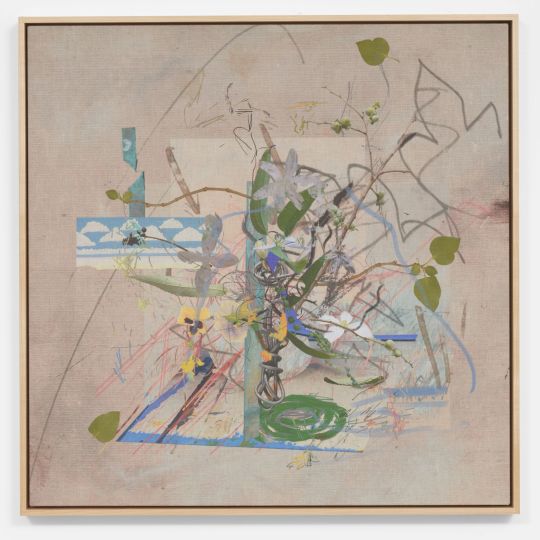

One learns not to miss a Petra Cortright solo exhibition, and “ultra angel wing absolute” proved to be a show that was not be missed.

While the aim of the exhibition may not have been to elevate an appreciation for the floral still life genre, it did so and more. Here, at Foxy Production, New York, it was possible to witness a breakthrough body of work in the realm of 2D IRL digital artmaking.

It was natural to draw comparisons with traditionally-produced works artists of past decades (e.g., Paul Wonner, Pierre Bonnard, Francis Bacon, Cy Twombly), however, as surface detail captured one’s attention, the dawning of a realization materialized that Cortright has achieved a shift today that is as significant as Andy Warhol had with his portraits of Elizabeth Taylor nearly 60 years ago.

It’s all in the “negative” spaces. In Cortright’s “www.fantasyislandgirls.com_stereo by design Spice Girls Nude,” the illusion of the canvas having been rubbed by graphite or charcoal and the vacant spaces, belying the digital techniques used in producing the work, is akin to the “depiction” of blank canvas in the left panel of Warhol’s “Silver Liz (diptych).”

As for the exhibition itself, the space resembled a portrait gallery. The attraction of one work to the next drew one to move from the left to the right and, then, again, to the “beginning” of the sequence and, then, to step back and regard the installation as a whole.

The gallery-going experience has many rewards, and, in this case, it was inimitable. A Cortright gallery exhibition was a must-see event.

Foxy Production

“Petra Cortright: ultra angel wing absolute”

14 January to 5 March 2022

Barry N. Neuman

New York

March 2022

0 notes

Photo

The Dais Of Our Knives

Years ago

At Sotheby’s

I ran into a journalist

I knew from the art scene.

They told me they’d been away

For six months

Traveling.

We continued chatting.

As if they’d never been away.

In March 2020, I stopped by Team Gallery to see its Petra Cortright and Will Sheldon solo exhibitions. The adventure was extraordinary.

Cortright is typically known for her paintings, which initially look handmade but then reveal themselves to have been composed electronically and fabricated on a substrate. The synergy between the two is often pleasantly confounding, and the dichotomy between the tactility and the hands-off technique is perplexingly rewarding.

At Team, Cortright fabricated each layer of a digital composition that she had printed on a one-fold tabloid. The layers were suspended from a procession of dowels, installed just below the ceiling. In doing so, she physicalized the display of layers that one might see on the computer screen of a 2D designer if such a designer were to isolate each layer on, respectively, a sequence of dedicated pages.

(Think of how Damian Ortega’s mobile of the principal components of an automobile was presented at the 2003 Venice Biennale. Here, however, Cortright presents large-scale facsimiles of every single component of her two-dimensional work.)

Some layers were pure abstractions, and other depicted landscapes. The irregularity of the shapes brought them into such sharp relief that they were rendered into still life objects. Again, in an inventive way, Cortright found a way to bewilder and delight a gallery audience.

Will Sheldon’s paintings depicted scenes of either fantasies or highly embellished realities. The artist’s gift for conflating the two prompted me to alternately take in the entire exhibition all at once and lean forward to investigate and marvel at each work’s details.

It would be simple to categorize Sheldon’s paintings as being purely Gothic because so much about them is about observations of the present and visualizations of life in the future. In the same way that one might recount about how during the course of a day they’d had a certain dream, promenaded through several neighborhoods within a town or a city, and contemplated a spectacular and speculative environment, Sheldon brings such narrative-like non-narratives to each of his canvases. Some of the spider webs, if looked upon closely, are sparkling. The scenes of the city (that arise behind the threshold of the dark forest that the viewer seems to be immersed within) exist in states of innocence – the kinds that one is unlikely to be cynical about.

As a painter, Sheldon has a remarkable touch. His craft skills can be admired, and what they deliver are sublime, modern-day, transgressive, pictorial enchantments.

Also in March 2020, I visited Foxy Production to see its solo exhibition of paintings by Srijon Chowdhury. Uncannily, many of this artist’s works feature an extraordinary surprise - a supernatural glow that emanates from the canvas as if it were both natural and fantastic (i.e., a specimen of fantasy). Chowdhury’s works appear to be simply about flowers, figures in nature, and intimate family scenes. However, through his subjects, his works are pulsating vessels – vehicles for vital forces. In this, he shares one of two things in common with Mark Rothko; the other is that Chowdhury is based in Portland, Oregon, the city where Rothko lived after emigrating from Russia.

Chowdhury’s grand tableau, “Pale Rider,” is a commanding work that was presented on the feature wall of the gallery. Measuring 7 feet high by 16 feet across, this painting has the power of a major work of medieval stained glass. “Pale Rider” depicts a nude equestrienne, riding a galloping horse through a free-form landscape of colorful flowers behind the plane of a fence of green ironwork, formed by words and geometric, abstract shapes. Here, the lady’s the one with the long mane. As a guiding force upon this equine creation-in-motion, she is riding in a streamlined, recumbent manner and holding a scythe in her left hand, beyond the plane of the horse. “Pale Rider” is other-worldly. The artist’s attention to detail makes it worthwhile to look at the painting up-close. Threads flow through and around the fence, and the lushness of the greenery in the background conjures up the most exalted of spring and summer days.

In August 2020, I returned to Foxy Production to see “Sex and love with a psychologist,” its solo exhibition of paintings by Sojourner Truth Parsons. It was like a blast from the early 1980’s, as seen through a lens of present-day thinking. Modern and graphic – as in what it is that a graphic artist produces – Parsons’ paintings depict portraits in high relief of studio interiors, and stylized cityscapes. They evoke the downtown Manhattan scene that had been brought to life by “The SoHo Weekly News” and the pre-Conde Nast “Details” Magazine. They don’t directly reference the decade, but the feeling is there. What makes them so engaging is how Parsons appears to have assumed that what was once transgressive in that half-decade is now conceptually and practically settled culture. The result is a very present symphony of beautiful technique and lively but simple colors: powder pink, black, and sky or powder blue.

Parsons’ approach to depicting studies and finished works, as installed on the walls of art studios, is fascinating. The representations of strips of artist’s tape and the works they support upon the walls where they’re displayed are endearing. The shapes are subtly but distinctively choreographed, and the process of decoding what these forms are about is very rewarding. The presence of the unseen individuals who live, work, and/or play in these environments is palpable. A viewer is never alone while engaging with Parsons’ work. Parsons’ works are rich in spirit and modernistically atmospheric.

In November 2020, I visited Hesse Flatow to see “Sincerely,” Aglaé Bassens’ solo exhibition of paintings. As a follow-up to her 2018 solo exhibition, “You Can See Better From Here,” at Crush Curatorial, it was a pleasure to see this artist move upwards and laterally, as her vision and technique has ascended, and her range of exploration of subject matter and technique has expanded in unexpected and intriguing dimensions.

What Bassens captures are moments: a burning cigarette butt, on a black surface in an ostensibly nocturnal interior; a car passenger’s view of an iced-over windshield and a dashboard on a winter day; a chaise longue and a matching chair (designed for poolside lounging), stretched out on grassy meadow, bordered by a forest, on an overcast summer afternoon. Each of her works is clearly a representation, and each is unmistakenly a painting.

Without knowing the title of the burning cigarette painting, one could marvel at its details for at least an hour. The wrinkled cigarette paper, the slightly crushed filter, the white-hot butt end, and the casually rising smoke are spectacles in themselves. The black surface upon which the cigarette rests is implicitly a table – a plinth upon which this common object is, for an instance, ennobled; it could never be anything as profane as a floor.

To see the car interior painting and the chaises longues tableau is to sense the seasons the subjects inhabit and to witness how with an economy of expression and the power of suggestion Bassens’ paint strokes bring these scenes to life and invigorate a viewer’s awareness of her actions and the works’ properties.

The body of work exhibited here hangs upon an invisible thread. Bassens’ paintings are portraits of the intangible. To encounter her interpretation of a collapsed, wind-blown beach umbrella and her partial view of a pair of blue garden chairs, outside on a rainy night is to experience the creation and manipulation of her subjects by humankind and the forces of nature that bring them to entropy. To witness Bassens’ mastery of her medium is to recognize the difference that paintings make as meaningful presences themselves.

In February 2021, I made a special trip to Marinaro Gallery to see “A Shift In the House,” a solo exhibition of paintings and works on paper by Lindsay Burke. In 2017, Burke’s dynamic paintings were stand-outs at Hunter College’s second-year, MFA group exhibition, and the provocative, semi-figurative, semi-abstract paintings she’d produced for her 2018 debut at Marinaro were subversively seductive and sophisticated. Burke’s most recent exhibition marked a turning point for the artist and, for art audiences, it represented a major highlight of the season.

Burke’s paintings revolved around the sleight of mind, eye, and hand in the conception, production, and reception of visual and physical creations. Homes, details of fixtures and studio implements, and landscapes are depicted amidst levels of abstractions that alternately draw the viewer towards the recognition of overall patterns and minute and discrete details.

Close examinations reveal brush strokes that resemble the kind that are made as test markings – what an artist daubs on an errant surface before making a commitment onto an actual work-in-progress. However, the marks that Burke makes are decisive. They are closely rendered, and they are what altogether becomes each overall work, a marvel that is astonishingly self-referential. They can remind a viewer of many things, but they are unique and exceptional unto themselves.

To compare Burke’s paintings to those of the modern pointillists would be reasonable but off-target. More aptly, one might compare the paintings from “A Shift In the House” to those of Jasper Johns; taken individually and altogether, they can enchant and impress in their entirety, and from up-close, they can truly engage the eye and the mind.

In February 2021, I visited Microscope Gallery and saw “Transmutations,” a remarkable exhibition of works of sculpture by Yasue Maetake. In its expansive location in Bushwick, Microscope succeeded in creating a grand tour of phenomena of great intrigue – highly unified works, composed of materials that existed on the surface of the mind (i.e., the recognizable) and those that existed in the deepest and most faraway galaxies of the imagination – the poetic and the unknowable.

They conjured up memories of photographs of expressionistic figurative works, produced in the mid- to late-1950’s – manifestations – as the writer of a Museum of Modern Art catalogue noted – of post-war anguish. Maetake’s works, though, are elegant and poised. Individually and collectively, they are almost baroque. More certainly, they are dynamic.

Upon learning that portions of many of the works are composed of camel’s bones, I thought of Nancy Graves’ large representations of camels in motion, and the contemporary character of Maetake’s oeuvre clicked, establishing itself into place with the great shift that occurred in art in 1970 and propelled wave after wave of innovative concepts and practices in each intervening decade. This body of work resides in the classical – owing to its profoundly pre-visualized and masterfully realized orderly character – and within the exuberantly enchanted space of the kinds of sculpture that could be made only today.

The harmony and the dissonance of each of Maetake’s works exist like movements in a symphony. Their constituent elements are too fine to be called “components,” and they often draw in the viewer without ever really calling attention to themselves. Her works are unique and exceptional, and they appear to be exotic, yet relatable and familiar. To encounter Maetake’s work in this half-kunst-kabinett and half-lair was an extraordinary and memorable experience.

In March 2021, I visited Kravets/Wehby Gallery to see Allison Zuckerman’s solo exhibition, “Gone Wild.” Consisting of wall-mounted tableaux and free-standing works of sculpture, a high-spirited galaxy of new and captivating creations was on view in the same space where Zuckerman had made her sensational debut only four years beforehand. In this new chapter of her ever-advancing journey, Zuckerman has pivoted from a variety of points and moved towards a greater sense of attention towards form and material.

The subject matter is still certainly there. Her super-metamorphosed, female figures of the fine arts reign on each planet of a painting, and they appear to be syntactically oriented further out on the ends of the branches of the greater dimensions where she’s been venturing. One of the most interesting exploratory movements observed here was the way Zuckerman intertwined “actual” painting with “virtual” painting in creating impressions that exceed each individually, and, in doing so, she enters the realm of orchestrating spectacle. Stated in a more oblique way, Zuckerman is sparking the imagination, as directors do in cinema and expanded, live theater.

Alfred Hitchcock and Jean-Pierre Melville, for example, were adept at integrating visual sleights of hand into their films. Although they deliberately showed the seams of montages in certain key scenes in their movies, they inexplicably created impressions that were undeniably effective even though they were more plausible than they should have been. In Hitchcock’s “Marnie,” the scene in which Marnie appears to be in danger while riding atop her frightened, runaway horse, the tension is oddly palpable; the mechanics of the editing of the images are unexpectedly visible, but Hitchcock succeeds in generating the suspense that’s necessary for heightening the viewer’s engagement in the story and carrying the viewer forward through the journey of the balance of the film. In Melville’s “Le Samouraï,” a nightclub owner is confronted in his office by hitman Jef Costello and is then seen pulling out his handgun first; however, in the successive montage, it is Costello who gets off the fatal shot that kills his intended target. The sequence is startling, and it jars the logic of the viewer; nevertheless, the viewer comes to not only accept the results but embrace them, as Melville chose to confound the viewer by not making the sights and sounds of the showdown conspicuous or obvious. The shock of Costello’s success and the miracle of his survival sharply impress the audience despite the visual and auditory discrepancies to which they have been presented with great suddenness.

In Cyril Teste’s stage adaptation of John Cassavetes’s film, “Opening Night,” presented at the French Institute / Alliance Française’s Florence Gould Hall in 2019, live acting is happening at the same time on the stage as video projections, many of which are sourced by the livestreaming video camera that is operated by a cameraperson who can be plainly seen by the audience but not acknowledged at all by the play’s characters. The left wing of the theater-within-the-theater of the play-within-the play is only partially visible to the audience, but the scenes there are entirely seen and heard through the technology that’s at-hand. Likewise, scenes taking place entirely behind the stage set are interpretively presented for the audience; the action and dialogue there are heard, as they may be customarily received in certain film scenes, such as those that are spasmodically illuminated by flashlights in pitch black conditions (e.g., “Le Beau Serge,” “The Blair Witch Project”). Alternately, scenes are also taking place at the center of the stage; they depict the actors playing characters in the play-within-the play and themselves, living out the challenges of their own lives as real people. The shifts from one mode to the next allow for the audience to interpret what’s happening and where. Despite it all, the performances of the actors – notably Isabelle Adjani, as Myrtle Gordon, and Frédéric Pierrot, as Maurice – brilliantly carry the audience through the play’s emotional roller coaster ride with both traditional, live stagecraft (e.g., classical vocal delivery, effective physical presence) and the enhancements that Teste’s filmic interventions convey.

In reconciling the many techniques that Zuckerman brings to a viewer, the evidence of the means and materials in the production of her works may be readily gathered and assessed, but, inexplicably, they deliver a variety of unexpected and often wondrous sensations. Each work delivers at one point or another in the viewing process a big payoff or a fireworks-show sequence of bursts of discoveries and unforeseen emotional responses.

This goes beyond the kind of examination that one might have while viewing the paintings of Giorgio Morandi or Diego Velázquez or the photographs of August Sander, as up-close and far-off perspectives of their works concern materials that are uniform throughout. The experience of regarding what was presented at “Gone Wild” was about transcending the employment of both paints and digital substrates and arriving at the harmonies that have been enchantingly realized by the artist’s generation of a succession of spectacles in at a time and place where one may be anticipating something reasonable.

In late July 2021, I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see “Alice Neel: People Come First.” After viewing all of the works in the show, I circled back to its “beginning,” and, from the center of each gallery space, I saw patterns of the abstract backgrounds of Neel’s portrait works, more or less lining the room. It was something that one can only sense spatially within an actual exhibition space.

I’ve often spoken about how a painting exhibition is more than a collection of images, rendered on canvas, framed or unframed. It’s the deployment of the works within a physical space that an exhibitor is presenting to an audience – and, by “presenting,” I mean gifting, treating, and delivering something special.

I’d been away from the Met for two years.

In seeing this Neel retrospective, it was as if I’d never been away at all.

Team Gallery

“Petra Cortwrigth: borderline auroroa borealist”

5 March - 2 May 2020

“Will Sheldon: Trouble After Dark”

5 March - 6 June 2021

Foxy Production

“Srijon Chowdhury”

5 March - 31 May 2020

“Sojourner Truth Parsons: Sex and Love With a Psychologist”

9 July - 22 August 2020

Hesse Flatow

“Aglaé Bassens: Sincerely,”

22 October - 21 November 2020

Marinaro Gallery

“Lindsay Burke: A Shift In the House”

28 January - 28 February 2021

Microscope Gallery

“Yasue Maetake: Transmutations”

29 January - 19 March 2021

Kravets | Wehby Gallery

“Allison Zuckerman: Gone Wild”

27 February - 2 April 2021

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Alice Neel: People Come First”

22 March - 1 August 2021

Barry N. Neuman

New York

August 2021

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 2020 Comedy Club Shutdown

The comedy club shutdown of 2020 may one day be known as the Great Vanishing Act of the Coronavirus Era. The disappearance of stand-up comics and live audiences, engaged in the conjuring up of mirth and laughter at intimate indoor venues, has brought a halt to a social economy, marked by the exchange of wit and performative delivery for levity and amnesia of ill fortune.

If you think this opening paragraph is unlike the set-up of a live, onstage comedy bit, you’re right.

It illustrates the situation live comedy is in today.

The spoken word, brought to you live and in-person, is very much different from and livelier than the written or mediated word, and the absence of live stand-up comedy puts into sharp relief how its vibrancy is noticeably different from what has succeeded it (e.g., essays, audio and/or video shows, posts on social media, etc.) Live comedy and its brilliance are sorely missed.

To take a closer look at the distinctions between the conditions of comedy before mid-March 2020 and the lockdown that came afterwards, this writer conferred with a selection of New York City-based comedians in August 2020. They reflected on what their concepts and practices were like before the pandemic and what their outlooks are for the future. All were elegant in expressing how the art of unseriousness is serious business. Furthermore, they portrayed what it’s like to go from being specifically a stand-up comic to being – more broadly – a comedy artist.

What was your routine before the COVID-19 lockdown in terms of writing, rehearsing, performing, pursuing projects, and booking opportunities?

SASHA SRBULJ: Before the lockdown, I would typically conduct writing sessions with my closest comedy buddies towards the beginning of the week and perform one to three shows at various spots in Manhattan throughout rest of the week. In between all of this, there would be dozens of discussions with other comics; we’d brainstorm, rehearse, and generate booking opportunities for each other. This weekly cascade of stuff could all fall under the rubric, “pursuing projects.” Also, by hanging out together during the week, we’d find ways of spurring creativity and ideas.

Since the start of the lockdown, almost all of these in-person activities have stopped, and they’ve become much more rare because the clubs are closed. We do try to maintain as much online and text-messaging contact as possible - but that's only one element, and it can’t replace the whole experience.

VERONICA GARZA: Before the lockdown, I was performing almost every day, doing shows or going to open mics. If I wasn’t at a show I was booked on or at a mic, I was supporting a show. Also, each and every day, I would try to write or to come up with at least three premises to work on. January and February 2020 were actually really busy months for me, and I was very excited to see where this year would go for me in comedy.

EMILY WINTER: Before Covid, I'd spend all day writing at home for my various writing jobs and script pursuits, then I'd do standup at night. I'd usually write new jokes on my way to shows or just work out new ideas when I got on stage.

CAROLYN BUSA: I’m realizing a lot of my routines happened for me on the train, and that’s the same for writing. Either on the way to a gig or on the way home from one. Those were always the times I was most inspired. Especially after experiencing how a joke hit.

After gigs, I would usually come home from a spot and fall asleep with my notebook in my bed, trying to perfect a bit about submissive sex right before bedtime.

The same goes for seeing a good show. I’d know a show was really good when I’d come home inspired and want to write a bunch of new premises.

Booking opportunities kinda happened naturally at countless weekly and monthly shows. Surely, some months were slower than others. (Cute, how I thought THAT was slow compared to now). During those times, I focused more on writing; my own show, Side Ponytail; or pursuing open mics.

I feel like I always have and always will have a million project ideas spinning in my head, but, without money or deadlines behind most of them, I complete and pursue them more slowly than I’d like to.

DARA JEMMOTT: I was really just moving and flying by the seat of my pants - taking any and every gig to make it work. I would do most of my writing on stage. With working 10 hours a day and then doing two to three shows a night, it was very difficult to sit down and find time to write. However, quarantine has allowed for me to write way more and in different areas.

MARC GERBER: I never made a set time to sit down and write, the way a novelist or a journalist might. My jokes come to me spontaneously, either through stream-of-consciousness - while daydreaming, that is - or in conversation with others.

My jokes generally start off as amorphous drafts. I have either a punchline that needs a strong opening premise or a premise that will need a strong punchline. About 10% to 20% of the bits that I come up with make it to the stage.

Before the lockdown, I would meet with comedian friends, and we’d polish and improve our jokes together. I’d rehearse only before a big show – such as one for recording an album or headlining a major gig. By this point, doing a 10- to 15-minute set had become rote. If I had a brand new bit, I might rehearse it in isolation several times before it performing on stage.

I typically don’t pursue projects or booking opportunities. Primarily, I am reluctant to ask people for opportunities, unless they are big, and I am ready for them. For example, I recorded my first album in November after aggressively pursuing a record label and convincing them to produce the album and release it. (Happily, the album debuted at Number One on the iTunes comedy chart and it’s been on heavy rotation on a major Sirius station). In terms of getting spots and other smaller opportunities, I generally take what I’m offered if they’re legitimate. However, I don’t ask for much, and I don’t implore people to put me on their shows. I think my approach is tactful.

ROBYN JAFFE: I stepped on stage for the first time just nine months before the comedy clubs and the city shut down, and I quickly became hooked.

I’m a teacher by day, and, over the summer, I was planning to explore more open mics, bringer shows, and auditions because the comedy scene doesn’t lend itself to the preferred early bedtime of someone, like myself, who works in a school during the rest of the year.

How have you responded to the lockdown? Did you initially see it as brief hiatus? Did you make it an opportunity to pivot to new projects? What have you missed most about stand-up comedy, so far?

SASHA SRBULJ: The lockdown was a shock, and, within the first three months, the only shows I did were on Zoom. I've since seen people doing park shows, parking lot shows - anything to fill the void. Aside from Zoom shows, I've done shows on Twitch, which was new for me.

I’ve done game-type, interactive audience shows. (There are online games now that are comedy-centric. An algorithm throws out some phrases and premises, and then, several comics try to make jokes out of them. The audience votes, participates, comments, etc.)

It's a format that provides a different kind of audience feedback. On Zoom shows, you generally can't hear the audience and mostly can't see them; so, it's hard to gauge and impossible to improvise much. The Zoom shows are improving, though. Even in five months, there's been tremendous progress.

I've pivoted to writing more - both bits for the stage and for writing in general. The time has also given me an opportunity to strategize the narrative for my next special/album. Planning basically. It's an opportunity to think things through deliberately.

What I've missed most about comedy was my friends. I thought it would be the laughter or the crowds and my own douchey desire to be at the center of attention; but what I actually miss the most is my friends.

(Note: My douchey desire to be at the center of attention is running in close contention.)

VERONICA GARZA: Overall, I’ve been generally concerned about my health, so I’ve done what I can to stay inside and avoid crowds.

I took the whole thing as an opportunity to work on other stuff. I finally made a full draft of my solo show about my dating men and even performing it over Zoom for two festivals. I have worked on an entire new half-hour of comedy. I’ve also considered this as an opportunity to work on scripts I’d intended to write.

I miss performing live. I miss seeing the audience - or even the lack thereof - and figuring out what I’ll do on stage. I miss seeing other comics and having that one drink after the show where we bitch about a show or a venue, but also just catch up. I noticed shows popping up randomly in New York City, and, honestly, I don’t think it’s safe enough for them yet.

EMILY WINTER: I absolutely thought it would be a brief hiatus, and I was excited. As both a writer and a standup, I feel like I never have enough time to dedicate to many of my writing projects. I saw this as the Universe forcing me to concentrate on my writing projects for a while. Since coronavirus, I've written two new pilots, rewrote an old one, wrote a movie with my husband, and got a book deal. I’m about halfway through the book-writing process. My two new pilots still need a lot of work, though.

I do miss stand-up. I miss the feeling of connection that you have when a set is going well. There's just this beautiful buzz in the air. It's magical.

CAROLYN BUSA: Oh brother. This is THE question isn’t it? Are you waiting for me to say, “God, I miss the mic!! Get me on the stage! My blood and bones need it!! Punchlines! Laughter! Applause!” Not quite.

I definitely did see it as a brief hiatus but kinda like how I adjust to traveling super quickly. (Every hotel or Air BnB feels like home within hours.) After a short time, NOT getting on stage felt freakishly normal. It kinda freaked me out and made the last ten years of my life feel like a fever dream. Maybe I'm already on a ventilator.

I, of course, miss having a great set, applause, and people telling me I'm funny. I miss the thrill of finding the line that makes whatever wild idea I have relate to the majority of a crowd. Or, if not relate, at least understand where I'm coming from.

I also miss parts of the socialization that came with comedy. My good friends, those that I'd see every now and then, the bartenders, the Barry’s! My social life was my day job and comedy, both of which are now gone.

Admittedly, there's a part of me that feels relief. The hustle has really beaten me up, so to kinda put that aside does not feel horrible. I thought I'd have more pockets of success at this point in my comedy career, and, even though I really like who I am as a comedian, not having to prove it for a few months feels ok.

So,...(shrugs shoulders) I'm still writing, and I'm still making goofy videos, but, more importantly, I'm really trying to figure out what makes me completely happy.

DARA JEMMOTT: At first, I responded to the lockdown with annoyance and fear, and, then, I enjoyed the fact I got to sit down for a second. Afterwards, I had to grieve a life I once knew.

I am getting to enjoy doing nothing because who knows when that will come again? I did realize that maintaining my mentals would be a top priority and that it was important for me to find projects to distract and dive into. So, I wrote my first pilot. Never would I have had time to do that before.

MARC GERBER: I initially saw the lockdown as a brief hiatus. Fortunately, I had my album coming out, and it gave me something to promote and look forward to. The success of the album’s release was encouraging, and I was able to do a number of online shows to promote it.

Since then, I have focused mainly on my other career as a psychologist, as the online shows are somewhat underwhelming, and I have been living outside of the city and thus, not getting the opportunity to do any of the outdoor shows that clubs and independent producers have been putting on.

What I miss most about stand-up comedy is the camaraderie of my comedian friends. Of course, there’s also nothing better than making 150 people laugh on a Friday night.

ROBYN JAFFE: I wanted to keep up with comedy-writing and joke-sharing during the lockdown, so I started a Twitter account. I also began to post a video to my Instagram account every Sunday night, and I call it “Pajamedy Sunday.” I may not have been able to get on stage all of these months, but I’m trying to make people laugh during a difficult time.

I did one Zoom show but otherwise haven’t performed.

What do you envision yourself doing before comedy venues fully re-open? After comedy venues fully re-open, what do you most look forward to doing? When live stand-up comedy fully returns, what do you expect the dynamic will look like between you and your live audience?

SASHA SRBULJ: While comedy clubs are closed, I hope I use my time productively. Aside from ironing out some aspects of my set, there's a writing project I want to try out and see if it has legs.

After comedy venues fully re-open, I am most looking forward to performing and seeing the community come back, which I hope it does. This lockdown has lasted long enough that things may not just snap back into place like before. I'm hoping that the thirst for comedy and just fun in general helps bring the community back quickly.

Frankly, until we have full herd immunity - either via a vaccine or just pandemic spread - I can't imagine things going back to the way they were. Brick-and-mortar comedy clubs are physically intimate spaces, especially in New York City, and laughter is an involuntary response that can spread aerosols. Unfortunately, comedy clubs, along with bars and night clubs, will be among the last establishments to reopen.

In the meantime, outdoor venues, virtual shows, and socially distanced shows are our only way. Once it's safe again, I think people will resume their lives as before. It may take a while for 100% of the people to be comfortable again, but, once the green light is given, most people will revert to the norm.

I initially thought this would permanently scar an entire generation of people and scare them from social interaction. However, as it turns out, the hardest thing about this crisis was getting people NOT to socially interact. So, I think when it will finally be safe, people will come back.

With both the positive and negative aspects of what this means, “You can't change people.”

VERONICA GARZA: If comedy venues even survives, I’m sure it will be a while before I return to live performances. I very much look forward to performing, but I also don’t want to rush to return to the stage and putting myself at risk.

I’m not that selfish. When live comedy returns, I’m sure it will be lovely. This current pause we are in has made everyone eager for some laughter, so I look forward to when we can safely do it in-person. As for now, I’m enjoying doing it safely over Zoom.

EMILY WINTER: I've been hesitant to perform at outdoor shows because I'm so immersed in my writing right now. I'm going to hold out a little longer while I re-work pilots and finish my book.

Once venues re-open, I'm looking forward to that brilliant feeling of connecting with strangers and feeling the collective energy in the room. I think that will be more difficult since I imagine people will be sitting farther apart. It's hard to create one unified energy when people aren't physically close together, and I worry about that.

CAROLYN BUSA: I will continue to think about and explore how to use my creativity to maintain my happiness! Writing, when I'm inspired; creating, when I want; and exploring other paths, possibly.

I've been dipping my toe back into writing stand-up, but it's been SLOW. I don't want to pressure myself too much or even say, “Put pressure on myself.” (Oh god, I hate brains).

I haven't done any outdoor performances, but, from what I hear, people are happy to hear jokes and happy to laugh. I'd expect that would be the same for when comedy fully returns.

I honestly don't know what to predict though. Every time I try to think of what something in the future will look like, I suddenly need a nap. My hope with this worldwide slowdown is that, in the future, comedy can be separated from those who want to hustle and work hard from 8 pm to 1am and those who want to do it from 5 pm to 11 pm.

DARA JEMMOTT: I'm really not thinking about "fully-re-open" and what that looks like or when that will come. I'm not going to put my life on hold and resume it after quarantine. Folks got to learn to live their life regardless and make the best of the situation.

I've been doing plenty of Zoom shows and outdoor shows, so I expect the dynamic to be the same. Uneasily and with trepidation, I’ve been happy to be out of the house and around people. But, "after quarantine" - I stopped using those words a long time ago.

MARC GERBER: I have been listening to the experts (e.g. virologists, epidemiologists) and not the politicians since this began. I knew by mid- to late February that comedy venues were going to close down. Before one of my shows in late February I posted, “Come see my while you still can!” Many people thought I was a joking, but I was being deadly serious.

According to the experts, this is going to be a long fight, particularly because of how poorly the federal response was in controlling the virus. I think comedy is going to come back very gradually.

Before the lockdown I was getting regularly booked at some of the best clubs in New York City. However, there are many, many comics ahead of me on the seniority list. I believe that for the next several years, if not longer, I will have fewer opportunities to perform than I’d had before the lockdown. I will have to find a way to engage myself creatively without getting on stage as much. That might include podcasting and writing. I am still figuring it out.

I feel fortunate to have a stable career as a psychologist. While comedians won’t be in high demand for a long time, psychologists certainly will be.

ROBYN JAFFE: Now, I attend comedy shows outside to enjoy live comedy and shamelessly talk to comics before or after the show. I hope to pick up where I left off whenever that becomes possible!

Comedy can be transformational, and these stand-up comics are stand-up people. Reading what they’ve said suggests that hearing what they will say on one stage or another will be something to look forward to.

Carolyn Busa: http://www.carolynbusa.com

Veronica Garza: https://twitter.com/veros_broke

Marc Gerber: https://800pgr.lnk.to/GerberIN

Robyn Jaffe: https://twitter.com/rjaffejokes

Dara Jemmott: http://www.instagram.com/chocolatejem and

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/comedians-for-hire/id1448386062

Sasha Srbulj: https://sashasrbulj.com/

Emily Winter: https://www.emilywintercomedy.com

0 notes

Text

Comedian

Comedian

1. A professional entertainer who uses any of various physical or verbal means to be amusing – Merriam Webster Dictionary [1]

2. A work of art by Maurizio Cattelan, consisting of a banana, duct-taped to a wall – artnet.com News [2]

3. Code #159.047-014 – Dictionary of Occupational Titles, U.S. Department of Labor p3]

On stage, a stand-up comic is typically given five minutes to perform a set before a live audience.

During those five minutes, it’s the aim of each comic to “kill.” That is, to shatter the silence in the room, to collapse solemnity and indifference, and to set off avalanches of laughter.

But, sometimes, they “bomb, and they’re met with complete silence and stares of incomprehension.

When, however, laughter or applause happens at the right time, the acceptance hits the comedian like a one-syllable word, like, “rush,” and it makes them wish it would last as long as a five-syllable word, such as, “exhilaration.”

In a stand-up comedy venue, immediate responsiveness is the currency of the social economy that exists between a comedian and an audience. What also counts for a comedian is knowing that a comedy show booker is witnessing the manic euphoria that breaks out when an audience responds to a comic’s set-ups and punchlines.

A part of being a comedian is being ambitious about writing new material, rehearsing in private, performing at open “mics,“ networking with other comedians, forming or joining peer groups, producing stand-up comedy shows with established and emerging comedians and local and out-of-town comedians, going on tour with a line-up of other comedians, hosting podcasts, being a guest on podcasts, producing videos of their live performances and posting them online, being active on social media, going on auditions, and, of course, staying funny.

Comedians perform at comedy clubs. Big and small.

They also perform in bars and restaurants. At dinners and parties. At fundraisers and festivals.

At bringer shows, each comic is required to bring a minimum number of spectators. In doing so, the line-up of comedians collectively delivers an audience for themselves (and show producers and/or venue operators). The attendees are typically supportive, and they often make it possible for emerging comics to feel more at ease in delivering their monologues.

At comedy festivals, comedians appear with and for their comedy communities and demographic peer groups. For audiences of all kinds, curated and juried festivals showcase the foremost comedians of any season.

Comedians aim to perform, to promote themselves for bigger and better bookings, and to be paid or paid well.

The allure of the adoring, live audience is irresistible to all comedians except when television, movies, digital media, “record” albums, and books arise as temptations. The desire to perform for the masses has motivated many stand-up comedians to pursue media careers.

For many comedians, going into hosting, acting, directing, and producing takes them onto pathways they hadn’t previously considered. For others, it arises as a collateral benefit or an intentional career objective. For those who discover that performing before actual people is a nerve-wracking experience, working in the privacy of a closed movie set or a writers’ conference room is a relief. For comics who promote themselves through merchandising, there are a fortunate few who generate a reliable stream of income for themselves.

However, when they discover that successful t-shirt sales don’t fulfill their compulsion for seeing and hearing a live audience laugh at their jokes, they go back on stage. And, the Department of Labor doesn’t have an answer for how that career move fits into its dictionary of occupational titles.

Barry N. Neuman

New York

February 2020

[1] Merriam-Webster Dictionary

[2] “Maurizio Cattelan Is Taping Bananas to a Wall at Art Basel Miami Beach and Selling Them for $120,000 Each,” Sarah Cascone, Artnet News, December 4, 2019

[3] Dictionary Of Occupational Titles (4th Ed., Rev. 1991), United States Department Of Labor, Office Of Administrative Law Judges Library

0 notes