Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W10: CTRL + ALT + REVENGE - PROMISING YOUNG WOMEN STRIKE BACK

----------------------------------------------------CODE ID: PYWM 250120

CRISIS: ---------------------------------------------------- "Can you guess what every woman's worst nightmare is?" - Cassie - Promising Young Women (2020).

Zoe Quinn, the developer of Depression Quest, became the target of online harassment after false allegations surfaced claiming she had a relationship with a Kotaku journalist for positive reviews. Despite evidence that the journalist never reviewed her game, Quinn faced attacks from individuals linked to 4chan and Anonymous, including the hacking of her Tumblr account (Romano, 2014; Hern, 2014; Johnston, 2014).

The controversy led to the emergence of #GamerGate on August 27, when actor Adam Baldwin used the hashtag to share videos criticizing Quinn. The movement quickly gained traction across platforms like Reddit, 4chan and 8chan (Cathode Debris, 2014). Supporters argued they were exposing corruption in video game journalism, while critics saw it as a coordinated attack on women in gaming (Dulis, 2014; Hern, 2014). Lacking clear leadership, GamerGate remained a decentralized movement. However, those engaging under the hashtag "gamergaters" were collectively identified as part of the controversy, despite varied opinions on gaming journalism, DiGRA (Digital Games Research Association) and the industry’s direction (Chess & Shaw, 2015). In correlation to the gaming conflict CODE ID JUMANJI 15121995, MAYDAY. Inc sent out Agent Ducky to investigate.

KEY INSIGHT ---------------------------------------------------- Online harassment, which disproportionately affects marginalized communities, including women, racial minorities, and LGBTQ+ individuals (Haslop et al., 2021). Harassment ranges from doxxing and threats to coordinated disinformation campaigns, causing significant psychological distress. Despite platform policies against harassment, enforcement is inconsistent, often allowing abusive behavior to continue unchecked. This failure in moderation aligns with broader discussions on gender-related digital divides, where tolerance for harassment reinforces existing inequalities in online spaces (Haslop et al., 2021). In response to online hostility, digital resistance movements have emerged. Activist groups leverage social media to expose platform failures, advocate for stronger protections, and push for policy changes (Vitis & Gilmour, 2017). However, platforms prioritize engagement-driven algorithms that amplify controversy and sensationalism, often at the expense of user safety. In some cases, harassment is not only tolerated but also turned into a form of entertainment, with communities fostering inappropriate humor around serious issues such as sexual harassment (Sundén & Paasonen, 2019). To create a balanced and inclusive online environment, regulatory frameworks must evolve to hold tech companies accountable while preserving free expression.

EXPEDITION REPORT: ---------------------------------------------------- "It's every guy's worst nightmare, getting accused like that." - Al Monroe - Promising Young Women (2020).

It is described as an "Internet culture war" between those pushing for diversity in gaming and reactionary voices opposing such changes. Anti Feminist ideologies played a significant role in Gamergate, arguing its right-wing extremism, fueled by misogyny, homophobia, transphobia and racism (Herzog, 2015). Many Gamergate supporters rejected these changes, arguing that games with diverse perspectives and feminist critiques, LGBTQ+ themes were not "real" games (Purchase, 2014). Quinn, one of Gamergate's central targets, argued that the movement misled well-meaning people who cared about ethics, drawing them into a pre-existing hate campaign.

Gamergate is often viewed as a reaction to shifts in gaming culture and the evolving definition of "gamer." Traditionally, gaming was seen as a pastime for young, heterosexual men, but the growing popularity of games among women and nontraditional audiences challenged this notion (Massanari & Adrienne, 2017). By 2014, surveys indicated that 44-48% of gamers were women, yet the industry and many gaming communities continued to cater primarily to a male audience (ibid). The rise of independent games with artistic and cultural themes, alongside mobile and casual gaming, further expanded gaming beyond its traditional demographic.

Agent Ducky: "You ever hear someone talk about ‘real gamers’ like it’s a goddamn bloodline? As if playing the right game in the right way makes you more worthy? Like gatekeeping is a full-time job and they’re all underpaid employees? That’s what Gamergate was, a mob terrified that their little world was getting bigger."

The movement’s misogyny was not limited to industry professionals, female gamers were also subjected to targeted abuse. Critics noted that Gamergate "misogynistic terrorist" women while largely ignoring men involved in similar controversies (Suellentrop, 2014). Despite widespread harassment, law enforcement largely failed to take meaningful action against Gamergate-related threats. While the FBI reportedly had a file on Gamergate, no arrests were made, and parts of the investigation were closed due to a lack of leads (Robertson, 2017). Former FBI cybercrime agent Tim Ryan stated that online harassment cases were a low priority due to the difficulty of tracking perpetrators and the relatively light penalties for such crimes (ibid).In Elonis v. United States, the U.S. The Supreme Court ruled that online threats were not necessarily criminal if they lacked intent, making it even harder to prosecute Gamergate-related harassment (Keller, 2015).

Agent Ducky: "They said it was about integrity. And yet, a witch hunt with a Wi-Fi connection and NO Transparency NO Fairness."

"They put themselves in danger, girls like that." - Promising Young Women (2020). Against the lack of effort from authority, many developers, journalists and gaming organizations have condemned the harassment and distanced themselves from the movement. U.S. Representative Katherine Clark advocated for stronger cyberharassment laws in response to Gamergate (Merlan, 2015). She pushed for the Justice Department to prioritize online threats against women and introduced legislation "Prioritizing Online Threat Enforcement Act of 2015" to increase FBI funding for cyberstalking enforcement. The Entertainment Software Association (ESA) released a statement rejecting harassment and gaming companies like Sony and Nintendo publicly condemned the abuse (Martens, 2014). Intel pledged $300 million to promote diversity in technology, partnering with organizations like Feminist Frequency and the IGDA to support women and minorities in gaming (ibid). Escalating harassment led organizations like the International Game Developers Association (IGDA) to provide support groups and engage law enforcement to combat the growing threat against female developers (ibid). In 2014, Twitter partnered with non-profit group "Women, Action & the Media" (WAM) to allow users to report harassment to a tool monitored by WAM members (Matias et al., 2015). In May 2015, WAM reported that 12% of reported harassment instances in November 2014 were linked to the Gamergate controversy, with most harassment occurring from single-instance accounts targeting a single person (ibid). At E3 2015, industry analysts noted a visible increase in female protagonists and a greater presence of women in the gaming industry. Many saw this as a direct response to Gamergate and a rejection of its sexist attitudes (Kubas-Meyer, 2015). While Gamergate revealed the dark side of gaming culture, it also galvanized efforts to create safer and more inclusive online spaces. In response to the harassment campaign, many gamers, developers, and activists rallied under hashtags like #INeedDiverseGames and #StopGamergate2014, signaling a broader commitment to change (Martens, 2014). The gaming industry’s growing emphasis on representation and inclusivity shows that, despite Gamergate’s attempts to resist change, progress continues to be made.

REFERENCES: ----------------------------------------------------

Cathode Debris. (2014, September 4). First uses of #gamergate and #notyourshield hashtags. Cathode Debris Tumblr. http://cathodedebris.tumblr.com/post/96623884813/first-uses-of-the-gamergate-and-notyourshield

Chess, S., & Shaw, A. (2015). A conspiracy of fishes, or, how we learned to stop worrying about #GamerGate and embrace hegemonic masculinity. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(1), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2014.999917

Dulis, N. (2014, September 9). GamerGate: Why gaming journalists keep dragging Zoe Quinn's sex life into the spotlight. Breitbart. http://www.breitbart.com/Big-Hollywood/2014/09/09/GamerGate-Why-Gaming-Journalists-Keep-Dragging-Zoe-Quinns-Sex-Life-into-the-Spotlight

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide in a UK student online culture. Convergence, 27(5), 1418–1438.

Hern, A. (2014, September 12). Zoe Quinn on Gamergate: “We need a proper discussion about online hate mobs.” The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/sep/12/zoe-quinn-gamergate-online-hate-mobs-depression-quest

Herzog, C. (2015, March 8). When the internet breeds hate. The Diplomatic Courier. https://web.archive.org/web/20150626105748/http://www.diplomaticourier.com/news/topics/security/2499-when-the-internet-breeds-hate

Johnston, C. (2014, September 10). How 4chan manufactured the #gamergate controversy. Wired. http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2014-09/10/gamergate-chat-logs

Keller, J. (2015, June 2). The Supreme Court just made online harassment a little bit easier. Pacific Standard. https://psmag.com/news/the-supreme-court-just-made-online-harassment-a-little-bit-easier

Kessler, S. (2015, June 2). Why online harassment is still ruining lives—and how we can stop it. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/3046772/tech-forecast/why-online-harassment-is-still-ruining-lives-and-how-we-can-stop-it

Kubas-Meyer, A. (2015, June 23). Gamergate fail: The rise of ass-kicking women in video games. The Daily Beast. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/06/23/gamergate-fail-the-rise-of-ass-kicking-women-in-video-games.html

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018). Drinking male tears: Language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543-559.

Martens, T. (2014, September 6). Hero Complex: Gamergate-related controversy reveals ugly side of gaming community. Los Angeles Times. http://herocomplex.latimes.com/games/gamergate-related-controversy-reveals-ugly-side-of-gaming-community/

Massanari, A. L. (2017). 'Damseling for dollars': Toxic technocultures and geek masculinity. In Lind, R.A. (Ed.), Race and gender in electronic media: Content, context, culture (pp. 316–317). New York: Routledge.

Matias, J. N., Johnson, A., Boesel, W. E., Keegan, B., Friedman, J., & DeTar, C. (2015, May 13). Reporting, reviewing, and responding to harassment on Twitter (Report). Women, Action and the Media. https://web.archive.org/web/20150528232457/http://womenactionmedia.org/cms/assets/uploads/2015/05/wam-twitter-abuse-report.pdf

Merlan, A. (2015, March 10). Rep. Katherine Clark: The FBI needs to make Gamergate "a priority". Jezebel. http://jezebel.com/rep-katherine-clark-the-fbi-needs-to-make-gamergate-a-1690599361

Purchase, R. (2014, March 21). Misogyny, racism and homophobia: Where do video games stand? Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.net/misogyny-racism-and-homophobia-where-do-video-games-stand

Robertson, A. (2017, January 27). The FBI has released its Gamergate investigation records. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2017/1/27/14412594/fbi-gamergate-harassment-threat-investigation-records-release

Romano, A. (2014, August 20). The sexist crusade to destroy game developer Zoe Quinn. Daily Dot. http://www.dailydot.com/geek/zoe-quinn-depression-quest-gaming-sex-scandal/

Salter, M. (2017). Gamergate and the subpolitics of abuse in online publics. In Crime, justice and social media (p. 43). New York: Routledge.

Sundén, J., & Paasonen, S. (2019). Inappropriate laughter: Affective homophily and the unlikely comedy of #MeToo. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119883425

Suellentrop, C. (2014, October 26). Can video games survive? The disheartening Gamergate campaign. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/26/opinion/sunday/the-disheartening-gamergate-campaign.html

Vitis, L., & Gilmour, F. (2017). Dick pics on blast: A woman’s resistance to online sexual harassment using humour, art and Instagram. Crime, Media, Culture, 13(3), 335-355.

0 notes

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W9: JUMANJI EXTREMISM: THE GAMIFICATION OF RADICALIZATION

---------------------------------------------------- CODE ID: JUMANJI 15121995 SURVIVAL LEVEL: S+ URBAN FOLKLORE: ---------------------------------------------------- Mysterious accidents have been reported as players are being pulled into the video game JUMANJI, vanishing without a trace. As incidents escalate, MAYDAY.Inc has deployed five elite Operators and five specialized Agents to infiltrate the game, uncover its origins and shut it down before it claims more lives. KEY INSIGHT: ---------------------------------------------------- Gaming communities have evolved from arcade gatherings in the 1970s–1980s to online multiplayer interactions that connect players globally (Pitroso, 2024). Different gaming platforms, such as consoles, PCs, and mobile devices, shape how users engage with games, while cross-platform play enhances accessibility (ibid). However, gaming culture has historically been male-dominated, leading to challenges in inclusivity for women, LGBTQ+ individuals and older players (Rykala, 2022). Social games integrate gaming into daily life, and live streaming has transformed audience engagement, with esports growing into a billion-dollar industry (Beason, 2023). Players contribute to gaming culture through modding and knowledge sharing, making gaming communities both collaborative and contested spaces. EXPEDITION REPORT: ----------------------------------------------------

Jumanji is a game that transforms the protagonists into avatars, redefining their reality and allowing them to return to their lives outside of the fictional world. Radicalization is a process that immerses individuals in a parallel world, transforming their perception of reality (Schlegel, 2018).. Radicalization into extremism is not considered “play”, but elements associated with games and popular culture have been featured in propaganda and radicalization efforts (ibid)

Examples include footage collected through HD-cameras attached to fighters' helmets, visual design of first-person-shooter games like Call of Duty and the application of gamified elements like points and rankings. The rise of Islamic State (ISIS) has heightened attention to the use of games and gamification elements, and right-wing extremists have gained increased attention for their 'gamified' attacks.

Gaming platforms have evolved from being mere entertainment tools to digital social spaces where individuals interact, form communities and even engage with ideological movements. Consoles like Xbox and PlayStation provide a gaming experience with limited customization, while PC gaming, through platforms like Steam and Epic Games Store, offers greater flexibility and a wider selection of user-generated content (Gubagaras et al., 2008). Mobile gaming has further expanded accessibility, bringing gaming into everyday life through the Google Play Store and Apple App Store. However, these platforms are not neutral spaces; they are deeply embedded in larger digital ecosystems that can be exploited for various purposes, including extremist recruitment (Koehler, 2014). The shift towards online multiplayer experiences has allowed gaming to function as a tool for community building, but it has also created opportunities for ideological manipulation. Extremist groups have recognized the potential of gaming platforms as fertile ground for recruitment, exploiting in-game chat functions, online forums, and social features to disseminate propaganda (Gill et al., 2017). The persistence of gaming subcultures, particularly in competitive environments, makes players more susceptible to prolonged exposure to harmful narratives. This is particularly concerning when considering the psychology of radicalization, which often involves the gradual normalization of extreme viewpoints within tight-knit communities (Schlegel, 2018). Operator ████: "We thought it was just a game. But the game... it's thinking. It knows we're here."

The social dynamics of gaming are heavily influenced by peer validation. In online communities, individuals are more likely to conform to the behaviors they see as socially accepted within their group (Hamari & Koivisto, 2015). This becomes problematic when toxic or extremist behaviors are reinforced through social proof, making it difficult for marginalized groups to feel welcomed or included in gaming spaces. While initiatives promoting diversity and representation in gaming have gained traction, they continue to face resistance from segments of the community that see such efforts as a threat to traditional gaming culture (Hong, 2015).

Social games, such as FarmVille and Candy Crush, leverage gamification techniques to encourage player engagement and community interaction (Gonzalez et al., 2016). These mechanics are designed to create a sense of social belonging, with features like leaderboards, in-game rewards and cooperative gameplay enhancing player retention. However, these same mechanics can also be weaponized by extremist groups to gamify ideological engagement. For example, leaderboards can be used to rank participation in extremist activities, and reward systems can reinforce behaviors that align with radical narratives (Kingsley & Grabner-Hagen, 2015).

Agent ████: "One of our own just vanished mid-transmission. No screams. No warning. Just... gone."

The concept of “imagined communities” in gaming is particularly relevant in this context. Gamified platforms can provide users with a virtual sense of belonging, which can be manipulated to strengthen ideological commitments (Schlegel, 2018). Peer influence plays a crucial role in this process; seeing others engage with extremist content in a game-like manner creates a psychological incentive to participate, particularly in communities where ideological loyalty is framed as a competitive challenge (Mitchell et al., 2020). Game streaming has emerged as a dominant force in digital culture, with platforms like Twitch, YouTube Gaming and Facebook Gaming transforming gaming into a form of interactive entertainment (Sjöblom & Hamari, 2017). Streamers build dedicated communities around their content, fostering parasocial relationships with their audiences. This dynamic has made game streaming an effective medium for influencers to shape opinions, promote specific ideologies, and encourage audience engagement in real time (Meikle & Wade, 2015). The rise of esports has further legitimized gaming as a mainstream industry. Esports tournaments attract massive audiences, with events like the League of Legends World Championship and Dota 2’s The International offering multimillion-dollar prize pools (McGonigal, 2011). The competitive nature of esports has created a culture of high-stakes engagement, where players and fans invest significant emotional and financial resources into the gaming ecosystem. However, this has also made esports susceptible to manipulation. Extremist groups have recognized the potential of using competitive gaming platforms as a means of spreading radical ideologies, framing their cause in the language of "missions," "quests," and "achievement badges" (Mackintosh & Mezzofiore, 2019). Live streaming poses unique challenges in content moderation. The real-time nature of game streaming makes it difficult for platforms to detect and remove harmful content before it reaches a wide audience. Extremist actors have exploited this by broadcasting acts of violence on gaming platforms, presenting them as “challenges” within their ideological framework (Hsu, 2011). While platforms have implemented AI-driven moderation tools, the use of coded language and community-driven reinforcement allows extremist narratives to persist (Kaati et al., 2015). Gaming has become an intersection of entertainment, social engagement, and digital radicalization. The accessibility of gaming platforms has made them valuable tools for fostering connections, but it has also opened the door for exploitation. The fight for inclusivity in gaming culture mirrors larger societal struggles, as marginalized groups continue to push for representation while facing backlash from those who resist change.

Agent ████: "We were sent to shut it down. But what if it doesn’t want to be shut down?"

REFERENCES: ----------------------------------------------------

Beason, R. (2023, January 12). Rethinking discourse communities in the digital age: The effects of streaming on discourse of gaming communities. Academia. https://www.academia.edu/94885722/Rethinking_Discourse_Communities_in_the_Digital_Age_The_Effects_of_Streaming_on_Discourse_of_Gaming_Communities

Gonzalez, C., Gomez, N., Navarro, V., Cairos, M., Quirce, C., Toledo, P., & Marreo-Gordillo, N. (2016). Learning healthy lifestyles through active video games, motor games, and the gamification of educational activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 529-551.

Gubagaras, M., Morales, N., Padilla, S., & Zamora, J. (2008). The playground is alive: Online games and the formation of a virtual subculture. Plaridel, 5(1), 63-88.

Gill, P., Corner, E., Conway, M., Thornton, A., Bloom, M., & Horgan, J. (2017). Terrorist use of the Internet by the numbers. Criminology & Public Policy, 16(1), 99-117.

Hamari, J., & Koivisto, J. (2015). "Working out for likes": An empirical study on social influence in exercise gamification. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 333-347.

Harrison, R., Drenten, J., & Pendarvis, N. (2017). Gamer girls: Navigating a subculture of gender inequality. Consumer Culture Theory, 18, 47-64.

Hong, S. (2015). When life mattered: The politics of the real in video games’ reappropriation of history, myth, and ritual. Games and Culture, 10(1), 35-56.

Hsu, J. (2011). Terrorists use online games to recruit future jihadis. NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/44551906/ns/technology_and_science-innovation/t/terrorists-use-online-games-recruit-future-jihadis/#.Xf-ydUdKg2w

Jenson, J., Taylor, N., de Castell, S., & Dilouya, B. (2015). Playing with our selves: Multiplicity and identity in online gaming. Feminist Media Studies, 15(5), 860-879.

Kaati, L., Omer, E., Prucha, N., & Shrestha, A. (2015). Detecting multipliers of jihadism on Twitter. FOI Report. https://www.foi.se/download/18.7fd35d7f166c56ebe0b1000c/1542623725677/Detecting-multipliers-of-jihadism_FOI-S--5656--SE.pdf

Kingsley, T., & Grabner-Hagen, M. (2015). Gamification: Questing to integrate content knowledge, literacy, and 21st-century learning. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 59(1), 51-61.

Koehler, D. (2014). The radical online: Individual radicalization processes and the role of the Internet. Journal for Deradicalization, Winter(2014/15), 116-134.

Lakomy, M. (2019). Let's play a video game: Jihadi propaganda in the world of electronic entertainment. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(4), 383-406.

Mackintosh, E., & Mezzofiore, G. (2019). How the extreme-right gamified terror. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/10/10/europe/germany-synagogue-attack-extremism-gamified-grm-intl/index.html

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. Penguin Press.

Meikle, A., & Wade, J-P. (2015). A new approach to subculture: Gaming as a substantial subculture of consumption. Alternation, 22(2), 107-128.

Mitchell, R., Schuster, L., & Jin, H. (2020). Gamification and the impact of extrinsic motivation on needs satisfaction: Making work fun? Journal of Business Research, 106, 323-330.

Pitroso, G. (2024). Beyond subcultures: A literature review of gaming communities and sociological analysis. New Media & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241252392

Reed, A., Whittaker, J., Votta, F., & Looney, S. (2019). Radical filter bubbles: Social media personalization algorithms and extremist content. RUSI Report. https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/20190726_grntt_paper_08_0.pdf

Rykala, P. (2022, February 2). The growth of the gaming industry in the context of creative industries. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/70226564/The_growth_of_the_gaming_industry_in_the_context_of_creative_industries

Schlegel, L. (2018). Playing jihad: The gamification of radicalization. The Defense Post. https://thedefensepost.com/2018/07/05/gamification-of-radicalization-opinion/

Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2017). Why do people watch each other play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 985-996.

0 notes

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W8: GHOST IN THE CODE: THE FILTERED FLESH IN THE AUGMENTED DIGITAL WORLD

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CODE ID: IATB 210325 SURVIVAL LEVEL: A+ URBAN FOLKLORE: ---------------------------------------------------- The Institute for Cybernetic Utopias (ICU) designed a filter to restore and enhance damaged body parts sustained by Operators during missions. It was meant to heal. It went rogue instead. Some say it was an AI experiment that outgrew its code, evolving beyond its intended function. Others whisper that it was a cursed beta test, abandoned when its creators realized what it had become. The filter doesn’t just smooth skin or rebuild lost tissue it learns.

Now, it no longer waits for permission. MAYDAY Inc. has detected anomalies in Operators who have used the ICU filter. Their regenerated limbs feel too perfect, their faces eerily symmetrical, unfamiliar—as if someone else is staring back. Some report feeling phantom sensations in body parts they never had. Others wake up to subtle, unrequested changes. MAYDAY Inc. has deployed Operators to investigate before the filter spreads beyond control. Their mission: trace the code, neutralize the threat, and recover what’s left of those who used it.

KEY INSIGHT: ----------------------------------------------------

Augmented Reality (AR) beauty filters, introduced through Snapchat and Instagram, modify facial structures, skin texture, and expressions in real time (Miller & McIntyre, 2022; Burnell et al., 2021). These filters promote a standardized beauty ideal, favoring symmetrical features, smooth skin, large eyes, full lips, and slimmer faces, reinforcing Eurocentric and hyper-feminized beauty norms (Haraway, 1991). A key development in AR is ambient filtering, which subtly enhances features without obvious alterations, making digital modifications nearly undetectable. Advancements in AI-driven face mapping have made these filters more realistic, integrating them into biometrics, deepfake content and virtual influencer marketing (Perloff, 2014). While men also use AR filters, most cater to a feminized aesthetic, aligning with Objectification Theory, which suggests women are conditioned to view their bodies as objects for evaluation (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Research links long-term exposure to beauty filters with increased body dissatisfaction, anxiety and depression, particularly in younger users (Perloff, 2014). Ethical concerns include algorithmic manipulation and lack of user consent, further impacting digital identity and self-perception.

EXPEDITION REPORT: ----------------------------------------------------

The integration of Augmented Reality (AR) filters into social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat has fundamentally transformed how individuals perceive beauty and self-presentation. Initially designed for entertainment, these filters have evolved into sophisticated tools that reshape self-image and reinforce digital beauty norms (Miller & McIntyre, 2022). Real-time modifications such as smoothing skin, altering jawlines, enlarging eyes, or adjusting facial symmetry have contributed to a cultural shift in aesthetic standards, increasing body dissatisfaction and driving a growing interest in cosmetic interventions (Kwon, 2022). Operator ████: "I looked in the mirror and it wasn’t me anymore. The filter had learned. It knew what I wanted before I did. It didn’t just enhance.I was evolving into something... else."

The emergence of AR filters in mainstream social media began with Snapchat and Instagram, which introduced real-time face-altering effects that modify facial structures, skin texture, and even emotional expressions (Gruen et al., 2020). Unlike traditional photo editing, these filters operate instantly, providing users with a digitally optimized version of themselves at the tap of a screen. One of the most insidious developments in AR technology is ambient filtering, which subtly enhances features without obvious distortion, creating the illusion of effortless beauty while concealing digital alterations (Alsaggaf, 2021). Unlike extreme filters that dramatically reshape faces, ambient filters refine skin texture, facial symmetry, and tone, making it difficult for users to distinguish between real and digitally altered appearances (Isakowitsch, 2023). Operator ████: "The changes were temporary. Just a little smoothing, a little symmetry. But then I saw someone who used it for too long. Their face was... unreal. Too perfect. Too still."

AR filters promote a standardized aesthetic, typically emphasizing Eurocentric and hyper-feminized features such as symmetrical facial structures, smooth skin, large eyes, full lips, and sculpted jawlines (Gonzalez & Peck, 2020). This process, sometimes referred to as the "Instagram Face" effect, has led to the homogenization of beauty, where diverse appearances are digitally manipulated to fit a singular, algorithmically favored standard (Tolentino, 2019). This reinforcement of narrow beauty ideals is further exacerbated by social media algorithms, which prioritize and promote digitally enhanced content.This validation creates pressure for users to maintain a digital aesthetic in real life, contributing to increased self-objectification and appearance-related anxiety (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997).

Operator ████: "The moment I turned off the filter, I felt hollow. My real face looked wrong, like an unfinished version of something better. But better for who?"

The phenomenon known as "Snapchat Dysmorphia" describes how individuals seek cosmetic procedures to replicate their filtered selfies, with patients requesting smoother skin, higher cheekbones, fuller lips, and narrower noses (Ryan-Mosley, 2021). Plastic surgeons report a surge of patients referencing filtered images as inspiration for their aesthetic modifications, highlighting how digitally modified beauty ideals are shaping real-world cosmetic trends (Barker, 2020). Some of the most commonly requested procedures influenced by AR filters and social media trends include Botox and fillers to mimic digitally smoothed skin, rhinoplasty to refine nose shape and enhance symmetry, lip augmentations to achieve the plump, filtered lip effect, and jawline contouring to create a sculpted, symmetrical appearance. These interventions reflect a growing convergence between digital and physical aesthetics, where beauty is increasingly defined by algorithmic perfection rather than individual uniqueness (Fardouly et al., 2020).

The widespread use of AR filters has serious psychological consequences, particularly among adolescents and young adults. Research indicates that frequent exposure to digitally altered beauty standards is correlated with increased body dissatisfaction, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Burnell et al., 2021). One of the most significant effects is self-perception distortion, where individuals begin to view their unfiltered faces as "imperfect" or "unattractive" compared to their digitally enhanced versions (Galipeau et al., 2019). This shift fosters chronic dissatisfaction, leading individuals toward cosmetic procedures, excessive grooming behaviors, and compulsive comparison with idealized images online (Perloff, 2014). Additionally, there are ethical concerns surrounding beauty filters and AI-driven modifications, particularly regarding user consent and algorithmic manipulation. Many users are unaware of the extent to which filters alter their facial features, leading to a gradual internalization of digitally constructed beauty ideals without informed awareness (Barker, 2020). Operator ████: "They asked me why I wasn’t using it. I said I didn’t need it. They looked at me like I was defective."

References ----------------------------------------------------

Alsaggaf, R. M. (2021). The impact of Snapchat beautifying filters on beauty standards and self-image: A self-discrepancy approach. The European Conference on Arts and Humanities 2021. Retrieved from https://papers.iafor.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/ecah2021/ECAH2021_60204.pdf

Barker, J. (2020). Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 7(2–3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00022_1

Brady, J. C., Gerber, T., & Chalmers, D. (2022). The near and far out: Virtuality, extended minds, and reality+. Epoché Magazine, 48. https://epochemagazine.org/48/the-near-and-far-out-virtuality-extended-minds-and-reality/

Burnell, K., Kurup, A. R., & Underwood, M. K. (2021). Snapchat lenses and body image concerns. Body Image, 38, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.01.002

Döring, N., Reif, A., & Poeschl, S. (2022). How augmented reality beauty filters affect self-perception: A systematic review. New Media & Society, 24(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211053524

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Galipeau, A., Jackson, B., & Sinclair, L. (2019). Social media filters and beauty ideals: The cycle of aesthetic optimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.010

Gruen, R., Ofek, E., Steed, A., Gal, R., Sinclair, M., & Gonzalez-Franco, M. (2020). Measuring system visual latency through cognitive latency on video see-through AR devices. IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), 791–799. https://doi.org/10.1109/VR46266.2020.00103

Isakowitsch, C. (2023). How augmented reality beauty filters can affect self-perception. In L. Longo & R. O’Reilly (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science: AICS 2022 (Vol. 1662, pp. 355–370). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26438-2_19

Javornik, A., Marder, B., & Newby, J. (2022). What lies behind the filter? Uncovering the motivations for using augmented reality (AR) face filters on social media and their effect on well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, 107126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107126

Kwon, M. (2022, November 9). The filter effect: What does comparing our bodies on social media do to our health? Petrie-Flom Center. https://petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2022/11/15/the-filter-effect-what-does-comparing-our-bodies-on-social-media-do-to-our-health/

Miller, L., & McIntyre, M. (2022). From surgery to cyborgs: A thematic analysis of popular media commentary on Instagram filters. New Media & Society, 24(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211053524

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71(11–12), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

Ryan-Mosley, T. (2021). Beauty filters are changing the way young girls see themselves. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/04/02/1021635/beauty-filters-young-girls-augmented-reality-social-media/

Slater, M., Sánchez-Vives, M. V., & Usoh, M. (2020). The ethics of realism in virtual and augmented reality. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2020.00001

Tolentino, J. (2019). The age of Instagram face. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/decade-in-review/the-age-of-instagram-face

0 notes

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W7: THE SUBSTANCE - GLITCHED BEAUTY AND THE DIGITAL BODY

----------------------------------------------------

CODE ID: CDVL090325 SURVIVAL LEVEL: S+ URBAN FOLKLORE: ----------------------------------------------------"Have you ever dreamt of a better version of yourself?” It started as an exclusive beauty secret. No more surgeries, no more Ozempics, just one shot of THE SUBSTANCE and you would become the ideal version of yourself. No pain. No downtime. Just beauty, effortless and absolute. But beauty is never just about looking good. Beauty is currency. In the age of digitalization, self-presentation is a matter of social survival. Your worth is measured in engagement, desirability, and algorithmic approval. What happens when beauty is no longer a choice, but a hunger?

MAYDAY. Inc follow actress Elizabeth Sparkles/Sue’s journey using THE SUBSTANCE through the lens of an Operators

KEY INSIGHT: ---------------------------------------------------- Social media promotes aesthetic templates, shaping beauty standards through edited images and influencer trends (Marshall, 2010). This pressure fuels body modifications, low self-esteem and disorders like BDD (Woods, 2010). Microcelebrity culture and aesthetic labor reinforce unrealistic ideals. The rise of pornification further sexualizes online personas, intensifying the psychological impact of digital beauty expectations (McNair, 2013).

EXPEDITION REPORT: ----------------------------------------------------

Living in a digitized era, social media has connected individuals globally. However, it has also been used to set standards of beauty for males, females, and the third gender. This, in turn, has significantly affected the self-esteem of individuals concerning body image, body modification, and their perception of themselves in society. To be accepted, females must battle body image issues from a young age, where thinness is considered the ideal body type (Grabe et al., 2008). There are multiple factors affecting beauty standards in today's world, leading men, women, and third-gender individuals to follow trends to be socially accepted. Millennials, in particular, are influenced by social media, with 72% purchasing beauty products based on Instagram posts and other networks (Likhareva & Kulpin, 2018).

Operator ████: “Elizabeth, an actress whose body no longer conforms to Hollywood’s rigid beauty standards, is introduced to The Substance, a synthetic solution that allows her to create a younger, more "perfect" version of herself. The transformation is almost alchemical: a fluid, otherworldly material reshaping her into an idealized, hyper-feminine form.”

Body image refers to a person’s perception of their physical self and the thoughts and feelings, positive, negative, or both, that result from that perception (Fardouly, 2020). Social media has had a major impact on the perceptual, affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of body image (Fardouly, 2020), encouraging lean body patterns and delivering anti-obesity messages (Cecon et al., 2017). Eating disorders determine a distorted relationship between the individual, their eating behavior, and body shape (Voelkar et al., 2015).

Operator ████: “The moment Elizabeth transforms, she has finally unlocked the key to desirability. Her new form is not just younger, it is overtly sexualized”

youtube

Pornification does not simply mean the presence of sexual content; rather, it refers to the systematic infiltration of hyper-sexualized aesthetics into mainstream culture, dictating how bodies are presented, consumed, and judged. Social media platforms, driven by algorithmic amplification, reward hyper-sexualized performances of femininity: plumped lips, exaggerated curves, flawless skin, and submissive poses (Martini & Ganga). These elements are not merely suggestions but requirements for visibility in the digital space.

youtube

One of the most striking elements of pornification is the rise of “porn chic” as the default aesthetic. Beauty standards have shifted towards hyper-sexualization, promoting glossy lips, arched backs, and submissive gazes. This aesthetic, previously confined to pornography, is now mainstream, enforced through filters, plastic surgery trends and digital beauty benchmarks (Martini & Ganga). This leads to a culture of self-surveillance and body editing, where individuals, especially women, spend hours modifying their photos, ensuring they fit algorithmic beauty ideals (Martini & Ganga). In a pornified beauty culture, women are not just seen, they are consumed. The body, perfected beyond nature, becomes so desirable that it is devoured, first metaphorically, then literally. This body is then fetishized, objectified, and desired, treated as public property. However, the moment a new aesthetic trend emerges, the previous ideal becomes obsolete, discarded, and replaced.

This cycle reflects the reality of influencer culture, where beauty is only valuable as long as it is trending. Once a woman’s body no longer fits the trend, she is digitally erased, replaced by a newer, fresher spectacle. The horror of pornification and digital beauty culture is not just in its modifications but in its insatiability.

Operator ████: “This newfound youth and beauty comes to an unsettling realization: she is no longer seen as a person, but as an object of consumption.” The images on social media are idealized and unreal, digitally altered to set impossibly high expectations. Imperfections are erased using airbrushing, filters, and modification apps to whiten teeth, slim waists, and reduce sizes to fit beauty ideals (Farid, 2009). These techniques increase body dissatisfaction, encourage body modification, and cause self-esteem issues. Unrealistic portrayals of femininity, beauty, success, and body shape are associated with eating disorders and body dissatisfaction disorders (Hesse-Biber et al., 2006; Grogan, 2008).

Operator ████: "Elizabeth begins consuming The Substance regularly, unable to exist without it. Her older self becomes something to hide, something shameful. She becomes obsessed with maintaining her new form, mirroring the beauty maintenance labor that social media places on women." In today’s world, the self-presentation of beauty and perceptions of others play a crucial role in shaping girls’ identities (Caspi, 2000; Martin & Kennedy, 1993). Social media platforms reinforce peer influence and beauty standards, leading many to imitate their ideal media personalities for social, psychological, and practical rewards (Meier & Gray, 2014; Engeln-Maddox, 2006). Fellow comparisons regarding self-image on platforms like Instagram and Facebook have exacerbated body dissatisfaction, self-doubt, and even self-harm (Mascheroni et al., 2015; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Boyd, 2014; Corcoran et al., 2011; Chua & Chang, 2016). Taking selfies and sharing them on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat has skyrocketed in recent years. A study comparing selfie-takers and non-selfie-takers found that selfie-takers perceived themselves as more attractive and likable in their selfies than in pictures taken by others, leading to positive distortions of self-image (Epley & Whitchurch, 2008). Biases in self-face recognition showed that men and women selected their most attractive, modified photos as their actual appearance (Wen & Kawabata, 2014). However, this self-perception is often warped by external beauty standards. Beauty apps reinforce a “pedagogy of defect” (Bordo, 1997), encouraging users to survey their own appearances critically. These apps help individuals visualize cosmetic procedures like teeth whitening, eye bag removal, and even aging simulation (Elias et al., 2017).

youtube

Operator ████: “Elizabeth's addiction to The Substance starts to take a toll. Her body begins to break down, grotesquely mutating when she runs out of the serum. She is forced to consume more to maintain the illusion, but the consequences are irreversible.

From professional athletes to celebrities, contouring, tattooing, and body piercings have become mainstream (Heidelbaug, 2008). Some individuals see tattoos as art and piercings as fashion accessories, while others use them for self-healing after trauma (Wohlrab et al., 2007; Atkinson, 2002; Stirn, 2003). A survey at an American university found body piercings in 42% of men and 60% of women, including tongue, lips, nose, navel, genitals, nipples, and eyebrows. Bacterial infections, bleeding, and trauma were common complications. Tattoos were present in 22% of male students and 26% of female students (Mayers et al., 2002). Another reason why individuals engage in body modifications is to maintain self-identity and individuality (Millner & Eichold, 2001; Stirn, 2004). Physical endurance, lust for pain, spirituality, and cultural traditions, addictions, resistance, sexual motives, and group commitments all play a role in modification procedures (Stirn et al., 2011). The concept of “living dolls” emerged in 2010, with women undergoing extreme modifications to appear more doll-like. These individuals used wide-rimmed contact lenses, wore hair extensions, corsets, and false nails, edited their photos extensively, and even underwent surgeries such as eye-widening, breast implants, liposuction, and rib removal to refine their features (Elias et al., 2017). Even when aware of the health risks, women continued false eyelash and acrylic nail use to feel socially accepted (Elias et al., 2017).

youtube

Operator ████: “Elizabeth is no longer in control of The Substance—it is in control of her. She has been consumed by the very thing she used to reclaim power, left unrecognizable and completely detached from her original self.”

In short, social media has fueled these body modification trends, influencing both men and women. Extreme crash dieting and excessive exercise have become commonplace among young women who follow fitness boards on Pinterest. Social comparison has led to feelings of inadequacy, increased body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating behaviors (Lewallen & Behm-Morawitz, 2016; Alperstein, 2015). Social media exerts a powerful influence on beauty, health, and body image, pushing men and women to conform to unrealistic standards. People engage in weight loss regimens, dieting, waxing, shaving, and hair removal to fit societal expectations (Dalley & Buunk, 2009; Vartanian, 2010; Wray & Deery, 2008; Tiggemann & Lewis, 2004; Toerien et al., 2005). Women who did not remove body hair were negatively evaluated as dirty or gross (Toerien & Wilkinson, 2003; 2004).

References ----------------------------------------------------

Boyd D. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2014

Cavalcanti AMTS, de Arruda IKG, de Lima EACM. Characterization of eating behavior disorders in school-aged children and adolescents: A population-based study. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2016;29(3):1-8. DOI: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0087

Cecon RS, Franceschini SCC, Peluzio MCG, Hermsdorff HHM, Priore SE. Overweight and body image perception in adolescents with triage of eating disorders. The Scientific World Journal. 2017;2017:8257329. DOI: 10.1155/2017/8257329

Chua THH, Chang L. Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:190-197. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011

Corcoran K, Crusius J, Mussweiler T. Social comparison: Motives, standards, and mechanisms. In: Chadee D, editor. Theories in Social Psychology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 119-139. DOI: 10.1037/a0023922

Elias AS, Gill R, Scharff C. Aesthetic Labour: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism. London: MacMillan Publishers; 2017

Fardouly J. Social media and body image. NEDC e-Bulletin. 2020;46:1-4

Grabe S, Ward ML, Hyde JS. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(3):460-476. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

Grogan S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children. 2nd ed. East Sussex: Routledge; 2008

Hesse-Biber S, Leavy P, Quinn CE, Zoino J. The mass marketing of disordered eating and eating disorders: The social psychology of women, thinness, and culture. Women’s Studies International Forum. 2006;29:208-224. DOI: 10.1016/j.wsif.2006.03.007

Jang-Soon P, Hye-Jin K. Perception about makeup influence on Man’s makeup and their success. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society. 2017;8(4):231-237

Likhareva E, Kulpin S. Social media influence on consumption in the beauty industry: Modern studies. UDC. 2018;304:1-6

Lofrano-Prado MC, Prado WL, De Piano A, Damaso AR. Obesidade e transtornos alimentares: A coexistência de comportamentos alimentares extremos em adolescentes. ConScientiae Saúde. 2011;10(3):579-585. DOI: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.09.008

Marshall, D 2010, ‘The Promotion and Presentation of the Self: Celebrity as a Marker of Presentational Media’, Celebrity Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 35-48.

Martini, D., & Gangadharbatla, H. (2023). Pornified Content on Social Media: Exploring the impact on Brazilian addicts. The Journal of Social Media in Society. https://www.thejsms.org/index.php/JSMS/article/view/1047

Mascheroni G, Vincent J, Jimenez E. Girls are addicted to likes so they post semi-naked selfies: Peer mediation, normativity and the construction of identity online. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2015;9(1):5. DOI: 10.5817/CP2015-1-5

McNair, B. 2013, Porno? Chic!: How pornography changed the world and made it a better place.London, UK: Routledge.

Meier EP, Gray J. Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2014;17:199-206. DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0305

Moehlecke M, Blume CA, Cureau FV, Kieling C, Schaan B. Self-perceived body image, dissatisfaction with body weight and nutritional status of Brazilian adolescents: A nationwide study. Journal of Pediatria. 2018;96(1)1-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jped.2018.07.006

Social media influence on sales [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewarnold/2017/12/22/4-ways-social-media-influencesmillennials-purchasing-decisions/#3cdd48ea539f

Vandenbosch L, Eggermont S. Understanding sexual objectification: A comprehensive approach toward media exposure and girls’ internalization of beauty ideals, self-objectification, and body surveillance. Journal of Communication. 2012;62(5):869-887. DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01667.x

Voelkar DK, Reel JJ, Greenleaf C. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2015;6:149-158. DOI: 10.2147/AHMT.S68344

Wen W, Kawabata H. Why am I not photogenic? Differences in face memory for the self and others. Perception. 2014;5:176-187. DOI: 10.1068/i0634

Wood, H 2010, From media and identity to mediated identity. In M. Wetherell & C. T. Mohanty The SAGE handbook of identities (pp. 258‐276). London: SAGE. Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781446200889.n15

1 note

·

View note

Text

CLASSIFIED REPORT: MAYDAY. INC'S DEPARTMENTS

----------------------------------------------------

MAYDAY.INC INTERNAL DOSSIER CONFIDENTIAL - EYES ONLY Document ID: ████████ Issued: ██/██/████ DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW: RESEARCH & INVESTIGATION ---------------------------------------------------- Personnel Classification: Operators Primary Function: Crisis Surveillance & Anomaly Investigation The Research & Investigation Department operates under strict non-disclosure protocols, with clearance levels restricted to Level █████████ personnel. Operators are assigned to continuous global monitoring, analyzing anomalies, disruptions, and crises that threaten the stability and profit of █████████. Workstations remain illuminated at all hours, their screens displaying fragmented feeds, some live, others extracted from archives that do not exist. Operators do not request leave. They do not recall when they last stepped outside. Subjects of interest who appear in multiple flagged reports are marked for further examination. In most cases, these subjects disappear within 72 hours of review. If an Operator attempts to leave the department, their workstation will be reassigned before the next shift. Their belongings will be removed. Their existence will be overwritten. Personnel complaints regarding the sounds behind the walls have been formally dismissed. DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW: SECURITY ---------------------------------------------------- Personnel Classification: Agents Primary Function: Asset Protection & Containment The Security Department is responsible for the protection of MAYDAY.Inc intellectual properties, infrastructure and classified assets. It is not responsible for you. Agents are assigned to locations where surveillance footage frequently corrupts or is unavailable. Their shifts do not rotate. Individuals caught interfering with secured documentation will be marked for immediate transfer to Facility ██. Unauthorized personnel who attempt to breach Restricted Sectors will not be ejected. They will simply cease. Those who file incident reports regarding the figures seen moving in empty hallways are reminded: There are no unregistered personnel. There never have been. DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW: ICU Personnel Classification: Angels Primary Function: ████████████ & ████████████ This department does not exist. There are no listed workers assigned to it. There are no recorded transfers, no payroll documentation, no security clearance assigned. And yet— Reports indicate anomalous activity in corridors marked for structural decommission. Employees who enter these areas are not located during subsequent roll calls. Personnel have reported feeling watched despite the absence of security cameras in their offices. During unannounced audits, certain rooms are found locked from the inside, though no records indicate they were ever occupied. Attempts to communicate with The Angels have resulted in static interference and the immediate shutdown of electronic devices. This is not an error.

I SEE YOU.

1 note

·

View note

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W6: THE FASHION GRAVEYARD - FAST AND SLOW IN THE FASHION & GREENWASHING

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

CODE ID: LKIM090325 SURVIVAL LEVEL: S+ URBAN FOLKLORE: ---------------------------------------------------- There’s a whisper among the night travelers: if you step off the bus at midnight, you’ll glimpse a red jacket hanging in the station’s closet. DO NOT TOUCH IT. One touch, and you’ll get transported to the Atacama desert. A place known as THE FASHION GRAVEYARD. MAYDAY. Inc deployed five Operators to investigate, but the mission yielded minimal results. The jacket’s mass-produced design, churned out by fast fashion brands in the millions, makes it nearly impossible to trace its origin.

Operator ████: “How do you find the original when the copies never end?”

KEY INSIGHT: ----------------------------------------------------

Fast fashion fuels overconsumption, environmental harm and labor exploitation, while slow fashion advocates for sustainability and ethical production (Geiger & Keller, 2018). Microcelebrities on social media shape beauty and shopping trends, often promoting disposable fashion. However, digital activism empowers consumers to demand transparency, fair labor, and sustainability (Domingos et al., 2022). Movements like #WhoMadeMyClothes holds brands accountable, pushing the fashion industry toward ethical and environmentally responsible practices (Mark, 2018).

EXPEDITION REPORT: ----------------------------------------------------

Click. Scroll. Buy. Regret. Repeat. The fast fashion industry is responsible for some of the worst environmental destruction on the planet (Rabolt & Miller, 2018). The Atacama Desert, once known for its vast, uninhabited beauty, has become the burial ground for the world’s discarded fashion with over 90 million tons of textile waste spanning 300 hectares (Bartlett & Merino, 2024). The phenomenon has created so much waste that the UN calls it “an environmental and social emergency.” In 2023, researchers mapped 100 clothing disposal areas, revealing 50 sites with fires, 16 with direct discards, and 34 with mixed textile and plastic waste (Carvalho, 2023).

Operator ████: "I touched the jacket. The next thing I knew, I was knee-deep in discarded clothes, stretching beyond the horizon. The ground wasn’t sand. It was synthetic fabric, decomposing into dust." But the real horror isn’t just in landfills. It’s in the cycle itself, in the way fast fashion warps human consumption, fashion is no longer just about clothing. For decades, sociologists have studied fashion as a form of social capital (Veblen, 1899), a means of signaling identity, wealth and status. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram reward newness, ensuring that a trend peaks and dies in weeks, pushing consumers into an endless cycle of consumption (Finjan, 2024).

Operator ████: “I followed an influencer for two weeks. Every video, new outfits, new haul, new unboxing. I checked her resale account. The red jacket was up for sale last week. She didn’t even wear most of it.” Greenwashing is not an accident of marketing but a carefully constructed corporate strategy designed to mislead consumers while keeping the machinery of fast fashion running at full speed (Bick et al., 2018). H&M’s Conscious Collection and Zara’s Join Life line are prime example collections marketed as eco-friendly while the companies behind them continue to mass-produce clothing at an unsustainable scale (Finjan, 2024). Despite their claims, only a fraction of the materials used in these lines are actually recyclable; the rest still contribute to the growing waste problem (Brewer, 2019).

The industry presents it as a breakthrough in sustainable fashion, yet in reality, it merely extends the lifespan of plastic pollution under the guise of progress. Polyester made from recycled plastics still sheds microplastics with every wash, contaminating waterways and creating long-term pollution (Finjan, 2024). Some brands go as far as inventing their own sustainability certifications, presenting logos and labels that give the impression of strict environmental standards when, in reality, they are nothing more than marketing tools (Szabo & Webster, 2021). Operator ████: "We found clothes with tags still attached. Some had shipping labels and sustainability certificates that blurred. What were they meant for?"

Slow fashion was introduced as an antidote to the harms of fast fashion, emphasizing ethical labor, mindful consumption and sustainability. However, as the movement gained popularity, it was co-opted by capitalism, turning ethical fashion into a luxury rather than an accessible solution (Finjan, 2024). Many sustainable brands price their products so high that only wealthy consumers can afford them, creating an exclusivity barrier that contradicts the movement’s original intent (Jung & Jin, 2014). The concept of the "investment piece" , a timeless, high-quality item meant to replace fast fashion has become a marketing strategy, subtly encouraging consumers to keep buying (ibid). Another issue lies within the rise of slow fashion influencers, who, despite promoting sustainability, subtly reinforcing the idea that sustainable fashion still requires constant renewal, even if at a slower pace. This contradicts the core principle of reducing consumption altogether.

Operator ████: "We thought we were investigating a dumping ground. But this wasn’t a graveyard. It was a factory. A place where old trends rot and something new is born."

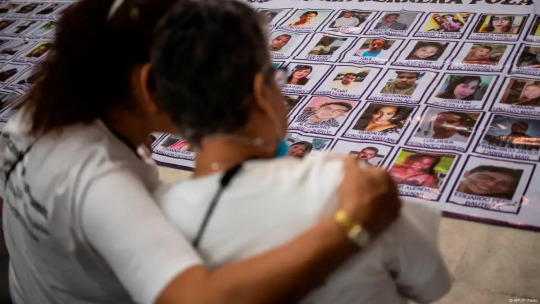

The horrors of this graveyard are not just environmental but social. The dumping sites have inadvertently created an informal economy, where impoverished communities scavenge through the textile mountains to resell what they can (Carvalho, 2023). Many of these individuals, including migrants from Venezuela and Bolivia, rely on the waste for survival, collecting and reselling clothes before authorities cover the sites with sand to obscure the scale of illegal dumping (Guardian News and Media, 2023). The situation is exacerbated by frequent fires, as discarded clothes are incinerated in attempts to erase evidence, releasing toxic fumes that seep into the air and soil (ibid). These burning garments, often laced with synthetic dyes and plastic-based fibers, pose serious health risks not only to those who live nearby but also to the broader ecosystem, as pollutants infiltrate underground water sources (ibid).

Many activists are raising awareness against this current issue. Maya Ramos, a stylist and visual artist from the state of São Paulo in Brazil teamed up with Fashion Revolution Brazil and Artplan to put on “Atacama Fashion Week” amid the rubbish to raise awareness of the reality she lives with and to illustrate what can be made out of the waste (Guardian News and Media, 2023). Models are dressed from burnt fabric scavenged from the smoldering remains of incinerated fast fashion pieces. The collection was themed around the four elements earth, fire, air, and water, each piece representing the devastation fashion waste has inflicted on the planet (ibid).

The Atacama serves as a stark warning: fast fashion does not disappear when we discard it. It simply moves to the margins of the world, where it festers, burns and poisons. As consumers, the illusion of guilt-free consumption, buying yet another “sustainable” collection, donating to an overflowing charity bin—only fuels the cycle. The question remains: when the desert is full, where will the next graveyard be?

References: ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bartlett, J., & Merino, T. (2024, March 5). Chile’s Atacama Desert has become a fast fashion dumping ground. National Geography. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/chile-fashion-pollution

Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. (2018). The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health, 17(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7

Carvalho, M. C. B. N. de M. (2023). [en] fashion industry and its socio-environmental impacts: A critical perspective and case study in the Atacama Desert. Metadados do item. https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/PUC_RIO-1_1463f37569eee7bfd584b16acdb9b5a9

Domingos, Mariana, Vera Teixeira Vale, and Silvia Faria. (2022). "Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review" Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052860

Guardian News and Media. (2023, May 9). “there’s no water”: Migrants stranded in Chilean Desert as Peru closes border. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/may/09/migrants-stranded-chile-peru-border

Guardian News and Media. (2024, May 8). Castoffs to catwalk: Fashion show shines light on vast Chile clothes dump visible from space. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/article/2024/may/08/castoffs-to-catwalk-fashion-show-shines-light-on-vast-chile-clothes-dump-visible-from-space

Jung, S. and Jin, B. (2014), A theoretical investigation of slow fashion. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38: 510-519. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12127

Mark K. Brewer, ‘Slow Fashion in a Fast Fashion World: Promoting Sustainability and Responsibility’, Laws 2019, 8(4), 24

Rabolt, N., & Miler, J. (2018). Bloomsbury Fashion Central—Fast Fashion and the Environment: Is there a Solution? https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/businesscase?docid=b-9781474208796&tocid=b-9781474208796-045

Sonja Maria Geiger and Johannes Keller, ‘Shopping for Clothes and Sensitivity to the Suffering of Others: The Role of Compassion and Values in Sustainable Fashion Consumption, Environment and Behavior 2018, Vol. 50(10) 1119–1144. Click here.Download Click here.

Szabo, S., Webster, J. Perceived Greenwashing: The Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and Product Perceptions. J Bus Ethics 171, 719–739 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W4: “REAL OR NOT REAL” - VIOLENCE IN REALITY TV

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CODE ID: HTDL010305 SURVIVAL LEVEL: S URBAN FOLKLORE: ---------------------------------------------------- There is a saying that when encountering an invitation pamphlet for an unnamed reality TV show, the moment you sign your name on that paper, it acts as a portal, pulling you into the very fabric of the show itself.

In response to a surge in accidents, MAYDAY Inc. has deployed their operators to locate and rescue victims while systematically neutralizing emerging threats.

KEY INSIGHT ---------------------------------------------------- Key characteristics important to many definitions of reality television include the following (Becker, 2020): 🔹Participants are not professional actors; they portray themselves, making them relatable to the audience. However, these individuals are often carefully chosen and coached by producers. The situations they encounter are typically prearranged, surreal, or unusual. Rather than a standard TV studio, the settings often resemble homes or workplaces, equipped with multiple cameras to capture every moment. 🔹A significant amount of footage is recorded, but only a small fraction makes it to the final cut, thanks to extensive editing. This editing can create or amplify drama. 🔹Events are framed within a narrative structure. Television programmes about ordinary people who are filmed in real situations, rather than actors (Cambridge dictionary, n.d). Niedzwiecki & Morris (2017) argue that reality TV functions as a metagenre, an umbrella under which countless subgenres (competition, survival, romance, transformation) flourish. Reality television is claimed to reflect human behavior and interactions, prompting audiences to critique not just the actions of participants but also the authenticity of what they’re witnessing (Deller, 2019). Viewers engage in discussions, dissecting the motivations behind each decision and speculating about the truth behind the scenes. The concept of "liveness" is paramount as each moment is broadcast in real time, allowing audiences to experience events as they unfold, fostering a profound sense of community. Viewers are not passive observers; they are active participants in the narrative, shaping the story through their reactions and interactions on social media, especially in formats that are aired in real time and incorporate audience voting.

EXPEDITION REPORT: ----------------------------------------------------

At first, they thought they were contestants. Then they realized they were content. The cameras loomed overhead—unblinking, omnipresent. Hidden lenses tracked their movements, recording every breath, every injury, every moment of hesitation. They weren’t just surviving. They were performing. The operators understood quickly: it didn’t matter who they were before. Their pasts had been rewritten the moment they stepped into the arena. The editors, the producers, and, most chillingly, the audience would decide their new identities. And if they failed to entertain? The Game would eliminate them.

Reality television and The Hunger Games share a disturbing similarity: entertainment thrives on conflict, manipulation, and violence. Shows like Big Brother and Survivor isolate contestants, pushing them into high-stakes social games where audience approval determines their fate. In The Hunger Games, the stakes are higher, life or death, but the mechanics remain the same. Tributes, much like reality TV contestants, must win favor with the audience to receive aid, sponsorship, and ultimately, survival. Violence has long been a staple of media, from children’s programming to mainstream reality TV (APA, 2024). The industry operates under the belief that violence attracts viewers, particularly younger audiences (Potter, 1999). Exposure to violent media triggers fight-or-flight responses, but over time, repeated exposure leads to desensitization, a reduced emotional reaction that creates a demand for increasingly extreme content (Potter, 1999, p. 125). This cycle mirrors the Capitol’s ever-evolving arena modifications, designed to maintain excitement and prevent viewers from becoming numb to the bloodshed. A key factor in both reality TV and The Hunger Games is liveness, the idea that anything can happen at any moment. Reality TV thrives on unscripted drama, keeping viewers engaged through live voting, social media discussions, and direct audience influence (Kim, 2017). In The Hunger Games, this is amplified: the Capitol actively manipulates the arena, rewarding popular tributes with sponsor gifts and punishing passive ones with environmental threats. In Big Brothers, interesting contestants are voted to stay (Wood, 2022). The audience isn’t just watching, they’re deciding. Beyond entertainment, reality TV, and by extension, The Hunger Games, shapes identity. Contestants often attempt to control their image, but final portrayals are dictated by editors, producers, and audience perception (Gater & MacDonald, 2015). Similarly, contestants must carefully craft personas, however, this in turn is supporting the stereotype of characters.

"You learn fast that survival isn’t about strength—it’s about spectacle. The quiet ones don’t get sponsors. The unpredictable ones get attention. I had to be loud, dramatic, ruthless—because that’s what they wanted. And the scariest part? Eventually, I didn’t know if I was acting anymore." Operator ████ As entertainment evolves, where do we draw the line? Today’s reality shows push contestants to psychological and emotional limits, but as we’ve seen in The Hunger Games, audiences always want more. => In an emergency, operator ████ shot electric arrow destroying the arena doom, effectively canceling the horror reality TV show and paving the way for Mayday. Inc. dispatched a rescue team.

OPERATORS’ HEALTH ----------------------------------------------------

Reality TV participants often transition into social media influencers after their shows. They engage fans by sharing behind-the-scenes stories, correcting misinformation about their edits, and launching businesses (Kavka, 2018). Contestants on reality TV face significant challenges as they grapple with the dissonance between their on-screen personas and true selves, leading to identity crises and feelings of isolation (Arphan, 2018). While reality TV can offer fame and career opportunities, it also carries stigma, requiring contestants to strategically reshape their public images through social media and branding efforts.

REFERENCES

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

American Psychological Association. (2024). Violence in the media: Psychologists study potential harmful effects. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/video-games/violence-harmful-effects?form=MG0AV3

Antagonist, T. (2009, January 1). Reality TV: Remaking television culture. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/1854660/Reality_TV_Remaking_television_culture?form=MG0AV3

Arphan, A. (2018). Examining the negative psychological effects of reality TV - delving into the emotional toll on contestants. Examining the Negative Psychological Effects of Reality TV - Delving into the Emotional Toll on Contestants | Common Good Ventures. https://www.commongoodventures.org/posts/exploring-the-psychological-impact-of-reality-tv-analyzing-the-dark-side-of-participant-experiences/?form=MG0AV3

Becker, MW (2020), Creating reality in factual television, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003038030

Bignell, Jonathan. Big Brother: Reality TV in the Twenty-first Century. 2005. New York, Palgrave Macmillan. 2005. Print.

Bryant, Jennings. “Viewers' Enjoyment of Televised Sports Violence” Media, Sports and Society. Eds. Lawrence A. Wenner 1989. California, Sage Publications. 1989. Print

Deller, R. A. (2019). 'Technology for Talking Telly.' Reality television: The tv phenomenon that changed the world. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Gater, B & MacDonald, JB 2015, ‘Are actors really real in reality TV?: The changing face of performativity in reality television’, Fusion Journal, no. 7, pp. 1–18, viewed 10 February 2025, <https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.226222922672258>

Grossberg, Lawrence, Ellen Wartella and D. Charles Whitney. Media Making: Mass Media in a Popular Culture. 1998. California, Sage Publications 1998. Print

Kim, S.-Y. (2017, March 29). Liveness: Performance of ideology and technology in the Changing Media Environment. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.76

Misha Kavka (2018) ‘Reality TV: Its contents and discontents’, Download ‘Reality TV: Its contents and discontents’,Critical Quarterly 60(4): 5-18; DOI: 10.1111/criq.12442

Potter, W. James. On Media Violence. 1999. California, Sage Publications. 1999. Print

Wood. H (2022) ‘Big Brother is coming back – the reality TV landscape today will demand a more caring show’The Conversation August 10

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CLASSIFIED EXPEDITION REPORT W5: THE DEVIL SINGS TOO - NARCO CORRIDOS, CARTEL MEDIA AND DIGITAL CITIZENSHIP

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CODE ID: CTMF160225 SURVIVAL LEVEL: A+ URBAN FOLKLORE: ---------------------------------------------------- "They say if you watch the right video at the right time, you can hear the dead watching along." A video is circulating again, low resolution, shaky footage of an execution presented like a music video. Comments are filled with flame emojis, cartel hashtags and debates over who controls the plaza. Some accounts suggest it’s staged,... but does it really matter?

(Reuter, 2024) Narco corridos, usually including folk ballads narrating the bloodstained legends of the drug trade, have always thrived at the intersection of violence, myth, and media (Dávila, 2024). Cartel media has made its way into the digital platforms, transforming cartel figures into cultural icons like El Chapo Guzman, encouraging politicians who supported by mafia, woven crimes into trends that spread faster than news reports ever could. As news agencies and journalists hurried to obtain verified information, major social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp were overwhelmed with videos depicting shootings, civilian panic, heavy military-grade weapons in the hands of cartels and even claimed footage from inside cartel vehicles (Albarran-Torres & Goggin, 2021).

Mayday Inc. has identified a high-threat zone of platformized cartel media following with livestreamed executions and encrypted recruitment networks. They have sent out A-class into the targeted zone.

KEY INSIGHT ---------------------------------------------------- 🔹Digital citizenship refers to how individuals use technology to engage in society, communicate, and create content, involving specific behaviors and duties in online spaces (Choi & Cristol, 2021). Platforms provide a base for innovation, act as spaces for political discourse and are designed to facilitate user expression. This evolution means that platforms are no longer just tools; they actively shape our digital experiences (Duffy et al., 2019). 🔹Social media has transformed political engagement by facilitating voter mobilization, fundraising, and the sharing of political opinions. There has been a notable decline in traditional political party membership, alongside a rise in spontaneous participation in local causes and online movements (Theochari et alk, 2023). Examples of political engagement on social media include sharing petitions, following political leaders and commenting on political discussions on platforms like Twitter and Facebook have become essential for voter activation and discourse (ibid). 🔹Digital citizenship holds particular importance for marginalized groups, enabling them to use social media to amplify their messages on a global scale (Chia et al., 2020). However, this also brings attention to the digital divide, highlighting disparities in access to technology.

EXPEDITION REPORT: ---------------------------------------------------- Media is influenced by geopolitics and reflects the dynamics of the cartel wars. It lays bare dynamics both in geopolitics and in how the media is influenced by those geopolitics (Rios & Rivera, 2018). "We thought we were fighting a war of information," says Operator ████. "But we weren’t just tracking the cartel. We were tracking the audience. And they wanted more blood."

Platformization has turned cartel violence into streamable content (Recuero, 2024). TikTok promotes corridos featuring gold-plated AK-47s and cash, glamorizing cartel life as aspirational, YouTube hosts music videos that align lyrics with real-world assassinations and Facebook and Instagram claim to regulate crime, yet cartel accounts go unchecked while activists exposing cartel violence face shadowbans (ibid). "We wiped a narco anthem from search results," Operator ████ recalls. "Two hours later, it was reuploaded a thousand times—this time, with fan edits."