Hello! I'm Katie, an MA Candidate in Public History at Western University, here to ramble about niche historical topics. She/Her

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I miss museums

Hello! How is your Sunday going? I’ve been spending some time recently, given the state of the world, thinking about museums I would love to revisit when everything returns to ‘normal’.

Rome isn’t a museum, but I would love to go back. I guess specifically, I would like to go back to the Vatican Museums, even though it’s always full of people, and the Colosseum, even though it’s always full of people. Maybe that’s part of the reason I would like to go back – to have another chance to see everything because the massive amounts of people make it hard to appreciate in one go.

I really want to go back to the ROM. I spent four years living literally next door to the ROM and March 12 will mark one year since I’ve been inside it. Obviously, I could’ve gone over the summer, but I was staying away from everyone and everything this summer. When I can finally go back in, I would really like about two hours to sit in silence in the Gallery of Greece. To my memory, there is no seating in the actual gallery which means I would probably end up on the floor. I would totally get on the floor and just relax if I didn’t think security would have a few qualms with that.

I love the ROM in its entirety but it’s the Gallery of Greece I really miss. The gallery is full of Greek sculpture and pottery and its lovely. I spent many hours in that gallery throughout my undergrad, studying specific pieces for projects, waiting for school kids to help them through and archaeology hunt, or just appreciating the pieces. Needless to say, it will be the first place I go to when I can.

Lastly, I would really like to go back to the Musee D’Orsay. The last time I was in the Orsay was all the way back in 2014. The museum is home to a large collection of impressionist art. My mum is a big fan of impressionism (we have Monet prints all around our home) and loves visiting the Orsay when we’re in Paris. Since it’s been almost seven years since I was in Paris, I can’t remember exactly what the Orsay is like which is part of the reason I want to go back so much.

This has been a rather short post but that’s okay, you didn’t want it to be any longer anyway.

Next week is as unknown as can be.

Until then, stay savvy.

0 notes

Text

A Story of the Gods: Fall of a City Round 2

I promised a part two in my last blog post and here we are. Today, I’m going to talk all things Fall of a City that are not Achilles related. Mainly I want to focus on two things: the Trojans and the Gods.

Let’s start with the Trojans, shall we?

For those who haven’t read the Iliad, a quick summary is in order. The Trojan War, a decade long conflict that the Iliad is set during, is started because Aphrodite promises the Trojan prince Paris the most beautiful woman in the world because he awards her the golden apple during the wedding of Peleus and Thetis instead of Hera or Artemis.

The thing is – the most beautiful woman in the world is already married. Her name is Helen and she’s married to Menelaus, the king of Sparta. Aphrodite doesn’t really care about that and steals Helen anyway and drops her off in Troy. You might imagine, Helen doesn’t much appreciate this nor does she want anything to do with Paris.

The abduction of Helen is what starts the war. You know, the face that launched a thousand ships and all that nonsense.

I tell you all this because the show decided that Helen not wanting Paris was boring. Instead, they show you a Helen, trapped by Menelaus (who gets such a bad edit): my king), desperate for a new life. Paris just happens to swoop in and save her and for a decade they live happily ever after in Troy during a war.

Paris is also just treated better overall. For some reason, the show runners decided Paris needed to know how to fight. In the Iliad, Paris is a bad fighter and uses a bow, the weapon of a coward, but not in the show! In the show, he somehow is a great fighter.

This is all to say, the show is told from a Trojan perspective. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t hate the Trojans. Homer is explicit in trying to have readers see the humanity in both sides and does so very well. No, my problem is that they rewrote the story so that it seemed like all the Greeks were the bad guys.

Now for the other issue: The Gods. Fall of a City has been praised for showing the gods as many other adaptations ignore the gods full stop. But I still want to complain.

To me, the Iliad is about one thing (well two: Achilles’ anger being the second), the way the gods play with human life for fun. This might have become clear in my recap of Aphrodite’s actions towards Helen and Paris but the gods really just do whatever they want in the story.

The Gods pick sides and urge the men of their chosen side to continue fighting. On many occasions during the Iliad, the gods single handily continue the war by inspiring the men to take up arms once more. They continue the war for their own enjoyment and interest without regard to the human life that is being destroyed below them. To me, this is the main takeaway from the Iliad. That war sucks. That no one benefits from war except the gods.

Fall of a City shows the gods blessing soldiers on the first day of battle. But other than that, they are basically uninvolved. Zeus tells them to stop and they do. And it’s the ferocious Greeks that continue the siege on the city, not the gods.

These two issues might seem minor in comparison to larger plot concerns. But in reality, the story that Fall of a City tells barely resembles the Iliad, just like so many retellings of classics. Modern viewers don’t understand the Trojan War as an example of the horrors of war and the whims of the god but rather as an ultimate battle between two armies.

Okay, rant over. Next week we will return to more historical topics.

Until then, stay savvy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I like Achilles, maybe a little too much

February 7, 2021

I’m alive! Happy 2021! I’m sorry it’s taken so long for me to get back here. If I’m being honest, I just didn’t know what to write.

This week I watched the 2018 Netflix Original miniseries Troy: Fall of a City, a retelling of Homer’s Iliad. I watched it because I’ve fallen back into my undergrad love of Greek mythology and art. I had just finished re-reading the Iliad when I decided to give the show a go.

There are a lot of good things about the TV show. I deeply appreciate the casting directors' move towards diversity. Black actors were cast to play Zeus and Achilles (and Patroclus, Aeneas, Nestor, and Antiochus), the two most powerful men in the story. I also liked the take that asked viewers to sympathize with the Trojans (or at least, I liked it at the beginning).

But you’re not here to hear me gush about great the series was. No, you’re here to hear my complain about it. So, complain I will.

My biggest issue with the show is its treatment of Achilles. Now, full disclosure, I love Achilles. He is likely my favourite Greek hero (although not my favourite character in the Iliad). But I think my comment remains valid. Achilles is a proud character whose pride is his downfall. His pride is his hubris, his fatal flaw. That is important to his narrative, for sure and I would never argue that Achilles should be treated any differently. But, his pride isn’t my issue.

My issue is threefold: his introduction, his anger, and his grief.

Achilles isn’t introduced until the 2nd/3rd episode of the series. He is mentioned in passing in the 2nd episode during the sacrifice of Iphigenia. When Achilles is finally introduced, he isn’t named. Every other character is named within 5 minutes of being on screen. But not Achilles. In fact, I had to google it because I was eventually frustrated trying to figure out if I was looking at Achilles or not.

His introduction comes at the bow of a ship as a convoy enters Troy for negotiation. The convoy is comprised of three men: Menelaus, Odysseus, and (unnamed) Achilles. Very keen observers will notice Achilles’ horsehair helmet for a moment in this scene but otherwise, there is no identifier for Achilles. In the Iliad, Achilles does not negotiate. So why does the show introduce Achilles in a negotiation scene without naming him?

Not only does the show fail to tell you who Achilles is until the first battle. They never (I mean never) tell you who he is. If you watched this show with no knowledge of Greek myth, you wouldn't understand it. Why does it matter that Achilles won’t fight? Why does Agamemnon care?

Achilles is ἄριστος Ἀχαιῶν (aristos Akhaiôn), the best of the Greeks. Viewers of this series will simply not know this. The series never tells you who Achilles is. It never tells you that he is a demi-god. It never tells you that his mother is Thetis, a sea nymph. Honestly, you won’t be able to understand why the army needs him unless you pause and google who he is.

The second issue I have is his anger. Maybe this is me being too attached to Achilles as portrayed in the Iliad (which is to say, not a lot) and the Song of Achilles (which is to say, as a good person) but I was tired of watching Achilles be a dick to everyone in his life.

He randomly goes into Troy and assaults Helen. Now, this becomes a major plot point, so I guess they needed that. But like honestly, I didn’t want to watch Achilles assault Helen for no reason (and the plot could’ve gotten on without the actual assault).

As an aside: in that scene, they imply that Achilles fought for Helen’s hand and lost. Okay two issues. One, he would’ve been a child when she was a child because they appear to be the same age. And two, he is god born. How would he lose to mortals? He was fated to be a great warrior before he was even conceived.

Achilles is basically a dick to everyone, including Patroclus which shook me. I won’t go into the characterization of Patroclus because that’s a whole other issue. We rarely see the two interact despite the fact that the series chose to depict their relationship as sexual. The only time you really see them talk for more than a single sentence is right before Patroclus dies and lovely Achilles says, “love is a weakness”. Great. Sick. Perfect.

This gets to my final point: Achilles’ grief. When Bresis is taken Achilles just looks angry and not sad at all. He’s supposed to be grieving when she is taken but all you see is him chilling. Add to this, you actually see Achilles and Bresis in a sexual relationship meaning he should care that she is taken. (A side note: one moment I did appreciate was when Achilles says “take her” and Bresis is like “Achilles???” and then he goes on to make his threat. Good stuff).

In the Iliad, Achilles basically loses his mind after Patroclus dies. He screams immediately and (my favourite part) pours ashes all over himself (not Patroclus’ ashes to be clear). Then he refuses to eat or sleep until Hector is dead. We see none of this on screen. We don’t even see some version of it.

We see Achilles yell when Patroclus dies and then carry his body away. (Don’t get me started about how the Trojans just let him take the body????) And then the next scene you see Patroclus’ pyre. And then Achilles goes and murders Hector. I think Achilles might have shed a single tear.

I should say, I don’t think this is a problem with the actors. I deeply believe the actors did an amazing job with a bad script. This is part one of two blog posts with my criticisms of this show. Next week, I’ll talk all about the Trojans and the gods.

Until then, stay savvy.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Nightmare of My Own Creation: Learning how to code during a pandemic

As I am sure many of you know, I have spent the last two months learning how to code. I thought I would reflect on the experience here for a moment and discuss the ins and outs of learning to code.

I won’t go into the nitty-gritty that I already covered in my first blog post. Instead, I want to talk about the experience overall (and I guess argue that it was worth it). I also wanted to take a moment to talk about Strawberry Thief because I didn’t get to during my presentation.

Strawberry Thief is one of William Morris’ most famous and most expensive pieces. It’s an 1883 textile print made using the indigo discharge method. This method was time consuming (it took three days) and incredibly expensive. This made it a great piece for me to use in an undergrad paper arguing that despite what some scholars think, Morris was a true socialist, not just one on paper.

You’re probably wondering how making luxury goods could possibly classify Morris as a true socialist. I won’t go into it too much (although ask me if you want more) but essentially Morris used his art as a visual argument for socialism and weaved his ideas into the very fabric of the piece. You’ve heard the saying “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism” but I think we can extend that further and argue “there’s no ethical creation under capitalism”. Morris was constrained by the economic realities of the Victorian Britain. His goods were luxury because he could not compete with factory goods that were badly made by underpaid workers.

Okay, back to the coding discussion. Here’s a timeline for you (I’ll insert some direct quotes from the log I kept):

October 15th: Began to try and code, failed miserably, couldn’t embed an image to save my life.

October 16th: “Coding is hard ): rip to my sanity”

October 24th: “Facetimed Mark for an hour and learned lots” Thank god for my brother.

October 25th: I gave up on creating a clickable image.

October 30th: Finally got a click to play a video. Highlight of the log: “This is what 45 minutes of work looks like… 10 lines of code.”

November 2nd: “Somehow I got it to work??? This is the entire code:” I inserted every line of code in case I lost something.

November 7th: “Mark just spent two hours on the phone with me teaching me code.” I’ll say it again, thank god for my brother.

Last log entry on November 9th: “Oh my god – a miracle.” I inserted a video of it working.

On November 9th, I got the side navigation test to work. I had only inserted one video but when I clicked background on the side nav, the image disappeared and the video played with a popup. From there, I just had to write a bunch more code that made it work with every side nav option.

After November 9th I stopped the log as things began happening much more quickly. I like this because it demonstrates how steep the learning curve is and then the sudden moment in which everything begins working. That isn’t to say nothing happened. If anything, more things happened between November 9th and December 3rd. But they happened so fast that recording them was difficult. In a single day, I went from having no ‘maps’ version, to having it work completely.

So now onto the big question of what I learned from this.

Was it worth it? Yes. I am very proud of the website and I cannot wait to flex it in interviews.

Could I have made it easier on myself? Maybe… I like a good challenge. When I look back, I’m not overconcerned that I made any fatal errors early on. As Tim said on November 26, coding isn’t something that you teach, you learn by doing and by failing.

Should you do it? The short answer is: yes, you should. I’m not saying every person needs to learn how to code. But I am saying it gave me a better understanding of web design and hopefully one day, I can actually contribute to discussions on website creation at a museum. Try it out, even if you just make a hello world sit and insert a picture. Visual Studio Code is free and it’s so easy (it even auto-populates!).

Thanks for reading me ramble about all the things I didn’t manage to say in my presentation.

I will probably continue to post, so keep your eyes peeled for more niche historical ramblings.

Until then, stay savvy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Here is the bird time lapse! For context, I am using a drawing for reference because I didn’t use my brain the first time around and left the bird below in the frame (you can see it underneath the flying bird if you pause the video).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Museums and Social Media

November 29, 2020

This semester I’ve been working as the Digital Collections Promotion Intern at the Museum of Ontario Archaeology (MOA). My job is essentially to create content to promote the behind the scenes work we do at MOA. I really enjoy my job and will be sad to finish up in December, but it’s got me thinking about museums and social media more generally.

Most museums aren’t the Louvre with 4.5 million followers. Don’t get me wrong, there are many famous or semi-famous museums that have large followings on social media (for the sake of this post let’s say over 100,000 is large). But what about the rest of us? What do you do when a museum has 20,000 or 2000 or 200 followers?

The first thing I want to discuss is how museums (and all business really) should understand social media. Most people think of social media as a promotional tool—and it is, don’t get me wrong—but imagining a social media account that only promotes the upcoming exhibitions, gift shop items, or even behind the scenes work leaves a lot to be desired for me. To me, social media is about creating a community.

The community need not be large. In all honesty, the larger the community, the more likely it is to one day implode. You don’t want to go viral. Instead, you want to build some sort of community that appreciates whatever it is your museum is about.

But how do you do it? Don’t take social media growth advice from me, my best friends’ little sister has more Instagram followers than I do. I’m still going to give the advice because what kind of blog post would it be otherwise?

In my mind, engagement is key. Because having a bunch of people follow you is great and all but if only two people comment on or reply to posts, what is your social media actually doing for you? Not a lot. Calls to actions are the cornerstone of engagement. This means asking questions in captions, doing polls, or asking for advice or input. All of these things help your followers feel like following you is more than just watching some institution online; it feels like being part of something bigger that extends beyond just you or your institution. The key here is centering this content around a bigger purpose. Ask yourself: what is the museum’s mandate? What are we striving to do? And then build the community around those ideas.

You have to imagine your social media as separate from your brick-and-mortar building. Your social media is the online community you build around the ideas and ideals of your museum (or whatever it is you do). When you treat social media platforms as one-way lecture halls instead of seminar rooms, you lose valuable opportunities to engage with your audience. I’m not saying you have to respond to every dm, I’m saying that if you let them, people will tell you what they want to hear.

Another rather important thing is understanding the medium. Not all social media platforms are created equal. People who love Twitter are very different from people who love Instagram. This isn’t to say that people only use one social platform, but rather that the intentions of each platform are vastly different and that your posts should reflect that.

Here’s the best example I can give: TikTok. Now, don’t come for me about loving TikTok, it’s a great platform. But the key to TikTok is that (as I saw once in a TikTok) it’s “one big inside joke”. The beauty of TikTok is that it’s a referential platform. It’s a platform based on creating new videos with old audio. And so, to thrive on TikTok, you need to actually use TikTok. You need to understand the original audio and then make your own spin on the audio.

I say this because 99% of institutions are failing at TikTok. They just don’t get it.

I would be wrong to say that an incoming generation of museum professional will fix this issue. As we discussed way back in the first class, we are not digital natives. Being young does not mean you are a tech genius I think like all things, some institutions will get better, others will drag along only posting about their collections.

I’m sorry this blog post didn’t come to a better conclusion.

What will we discuss next week? Only time will tell.

Until then, stay savvy.

0 notes

Video

tumblr

I enjoy watching this and I thought some of you might too. Also going to post my bird flying drawing because it’s nice too.

context: This is William Morris’s Strawberry Thief which I am using to create an interactive website.

0 notes

Text

Editing and Staging: Photography as Evidence or Art?

November 22, 2020

Alfred Eisenstaedt, V-J Day in Times Square. Source.

This is famous photograph. Officially it’s called V-J Day in Times Square although I’ve often heard it just called The Kiss. Alfred Eisenstaedt took this photo on August 14, 1945, the day Japan surrendered, ending the Second World War.

The photograph has been the subjects of many debates over the years. One of the biggest questions of the last 75 years has been about the identity of these two subjects – a sailor and a nurse. But we’re not going to talk about that today. Instead I’m going to use this photo as a jumping off point to talk about photography. There was a time on the internet when people claimed that the photo had been staged. Since then it has been disproven but that fact has always left me thinking about how the world understands photography.

Let me give you a little background on the history of photography. Photography was developed by multiple men simultaneously in the 1820s and 30s. These men were wealthy elites who had a good understanding of both science and technology. Today we use a method, in film cameras, similar to William Henry Fox Talbot using negatives. The other most famous creators, Louis Daguerre and Nicéphore Niépce, developed a different system using silver plates that’s now called a daguerreotype.

I’m interested in a photo from a little later. Gustave Le Gray’s The Great Wave was taken in 1856. Le Gray used a sophisticated daguerreotype method to produce the photo.

Gustave Le Gray, The Great Wave. Source.

I’m sure you’re asking what this has to do with V-J Day in Times Square? I’m getting there.

Exposure is how much light is allowed into a camera as it takes a photo. In modern cameras exposure is a combination of the ISO, aperture, and shutter speed. Using these three elements, modern cameras are able to expose properly for dark and bright parts of photographs. But Le Gray was not so lucky. In 1856, cameras could only expose for one. This meant that detail would be lost in the dark areas if you exposed for the light or vice versa. So, he took two photographs. One that was exposed for the sky and one for the sea. And then he printed half of each photo onto the paper creating one perfect shot of the sea. It’s ingenious and almost impossible to tell without knowing.

In many ways, questions of editing and staging photographs go together. Modern viewers think of editing and staging as sac religious to the art of photography. That’s why so many people on the internet cared that Eisenstaedt had supposedly staged V-J Day. The problem is that we treats photos like records but they’re art.

I used Le Gray because it’s my favourite edit, but it is far from the only one. Many 19th century photographers edited their photos. And no one, not photographer or viewer, thought that was an issue. Photography is not objective evidence of the past, despite what modern day viewers might think. Photography is an art. And like all arts, it’s deeply subjective to the bias of the creator.

Next time you think a photograph is fake, ask yourself instead why you expect a photograph to tell you an objective truth.

What I want you take from this post is a new appreciation for photography as an art and an understanding that modern editing has not changed the discipline, it’s actually expanded on a pre-exisiting world of photo editing.

Who knows what we’ll discuss next week, stay tuned to find out.

Until then, stay savvy.

#Digital Public History#History#VJ Day#VJ Day in Times Square#The Great Wave#Photography#history of photography

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Katie, I really enjoyed your post on photography and how visitors should be able to take photos to remember and reflect on their museum experiences. As someone who literally takes photos all the time, I am always afraid of forgetting the past. I also liked how you made the distinction between taking photos for social media and snapping photos to piece together the past. -Ivy

Hi Ivy, I too am afraid of forgetting the past!

0 notes

Text

Take a photo, it’ll last longer

November 15, 2020

The long delayed post on photography is finally here.

I recently watched this Vox video about the role of photography in museums and we also discussed some of these ideas in HIS9800 this week.

I have been known to criticize ‘Instagram traps.’ A while ago in class I mentioned my dislike of the drive-in Van Gogh exhibit. At the time I think it seemed like I was criticizing people for going there and taking cool Instagram photos. I was not. Or at least, I didn’t mean to.

I love photography, I love Instagram, and I love getting cool photos in museums, galleries, and historic sites. I’ve sprinkled my all-time favourite photos I’ve taken at such places throughout this post as proof. My problem with exhibitions like the Van Gogh Drive-in is that the people running them miss out on an amazing opportunity for a more immersive (and educational) experience. I can’t fault people for choosing not to learn when they go to a museum or gallery or whatever, but I can fault curators for choosing to not even give visitors the choice to learn.

When we talked about this in class, Victoria had said that maybe an app people could’ve downloaded before they went would’ve helped. This is a great idea, not only because an app would allow for interactive portions but also because then people could just choose what they read or listened to. Another idea would be to use the radios in peoples’ cars—similar to how a drive in move theatre works. Those two options came out of less than 10 minutes of consideration. Exhibitions take years to plan, there was plenty of time to think about how to include didactic information beyond wall text, they just chose not to.

But the Van Gogh exhibition is different from what Vox is talking about. Because Van Gogh is a well-known artist from an established historical movement. He is firmly in a historical discussion where didactic information is expected. The Museum of Ice Cream could give historical or scientific background, but as a subject it is less tied to traditional academic disciplines (let’s save the question of if the Museum of Ice Cream is a museum to another day, shall we?). And so, unlike the Van Gogh exhibition, I have less of an issue with the lack didactic information. I think they should still do it, but it feels less like a failure on the part of the curators to choose not to.

I’m turning to the photography portion of this because it’s the part I find most compelling. First, I want to say that in my life I have gone to many a museum that have not allowed photography and I didn’t feel like I somehow got more out of those experiences. If anything, as time passes, I feel like I got less.

Let’s keep the Van Gogh theme going. I was in Amsterdam in the fall of 2018 and I went to the Van Gogh Museum. The museum houses most of the family collection that was inherited after Vincent’s death. Notably, it doesn’t have Starry Night (it’s in the MOMA) which I know throws people for a loop all the time. It also doesn’t have my favourite Van Gogh Starry Night over the Rhone (it’s in the Musée d’Orsay).

The museum was great. It had lots of interactive, digital stations using tablets and other devices. Because it’s the family collection, Theo, his brother, comes up a lot and I’m pretty sure there was a whole tablet dedicated to looking at the letters between the brothers. I say pretty sure because I actually don’t remember a lot about the museum. Here’s where it ties back to the original content of the post – the Van Gogh Museum doesn’t allow photography. And so, two years later, I remember very little of the experience and I have no photos to jog my memory of the museum.

This brings us to the arguably more interesting argument of the Vox piece, how photography affects our experience. But I guess I immediately need to make the distinction between taking photos and taking photos for social media. I think most people don’t think there’s much of a distinction between these things, but I do. I take a lot of photos; photography is a hobby mine – like a deep hobby, like an I own a film camera hobby.

When you take a photo with the intention of posting it online, it becomes kind of like an assignment. You become more focused on how it looks, what others will think of it, (for some) how many likes it will get. I will say, these questions don’t bother everyone, just people who curate their feeds—meaning people who post well-crafted, edited photos. But this obsession with crafting the perfect photo can make an experience less enjoyable. The anxiety over getting the photo right can cloud the rest of the experience in your memory. This is what Vox is concerned about.

You can play a game with yourself if you want. Look at all the photos included in this post and try and decide which were taken for social media and which were taken on a whim. It’s clear to me but I guess that’s a given.

But some studies (here and here) have argued that you enjoy experiences more and remember them better when you take photos. And I think this is also true. Particularly when you’re not worried about capturing the perfect image but rather interested in taking photos of things you think are cool or art that you like. And I don’t think these two things (the stress of obsessing over the perfect photo and remembering more because you took photos) are mutually exclusive.

What I’m trying to say is that I think Vox made this conversation a little too one-dimensional for me. I totally relate to wanting to take a nice photo and just not getting it—that’s what creative ruts are. But having photographs of an experience allows you to walk down memory lane in a more immersive way. I can barely remember the Van Gogh Museum because I have nothing to trigger memories. I don’t think this is a major factor in the question of photography in museums, but I do think some museum purest might try to argue that allowing photography detracts from the visitor experience generally. And I simply think that’s untrue. Taking photographs at a museum will likely help you remember it more and it gives you a chance to flex those artistic muscles (something museums and, more importantly, galleries really need to encourage more).

Lastly, I want to address the idea of instagrammable spots in regular exhibitions. This is the idea of making specific areas of an exhibition photogenic, Vox uses the Yayoi Kusama example (which if you have a keen eye you’ll know I’ve been to). At the end of the exhibit there is an interactive component that, because you actually go inside it, is really photogenic.

I think these spots are a great idea. Having them as part of regular exhibitions is basically free advertising. People will see it on their feeds, want to take a similar picture, and buy tickets. And if, in doing this, you offer them an opportunity (which they can take or leave) to learn, that’s the Goldilocks spot for me.

I definitely think museums allowing photography is the move forward is all capacities. Limiting flash is a given for conservation efforts but I think there is a net positive outcome from allowing photography and including more interactive, photograph friendly portions of an exhibit.

Next week we tackle the history of photography and dare I say it authenticity. I know, I’m scared too.

Until then, stay savvy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Coding is Hard

November 8, 2020

I’m sorry for this in advance if you know literally anything about coding.

I know I said that this week I would talk photography… but I’m not going to. I swear, it’ll come next week AND the week after that. Today I wanted to talk about coding. To be specific, I’ll be talking about coding in HTML, something I would’ve guessed would be pretty easy. It’s not. Like at all. Like this is so difficult.

Some context, perhaps? For HIS9808, we have a final independent project in which we explore some form of digital history and report back about our experiences. Because I hate myself, I chose to code.

I decided to try and make an interactive website for William Morris pieces. For the project, I’m only doing Strawberry Thief but, if I can manage to make it work, I might add some more over time.

William Morris, Strawberry Thief source

So the basic idea that I pulled from my brain with literally no understanding of how coding works is this: the viewer clicks on a certain part of the image or some button along the side and the piece animates and a window pops up on the side and displays some information about the piece or Morris. Did that make sense?

My small non-coding brain figured this would be difficult but not impossible. I have now spent probably 25 hours working on just the coding. And I have almost nothing to show for it. Almost nothing because I do have new some knowledge and a navigation bar.

An aside: I’m animating the image to move when the user clicks and that has actually brought me much joy. Unlike the coding, all the problems that arise are solvable with the brain I currently have. I would put some of the animations into this post but I want them to be saved for when they are in the actual website.

The first thing I did was watch about ten YouTube videos. Then I called my brother. My brother is the smartest person I know (and I can say that because I know for a fact, he won’t read this). He went to Queen’s for Apple Math engineering and he now works coding (in python, I think) for a contracting company. So, I called him for a little tutorial if you will. He’s never coded in html so it was basically him showing me the program I should use (visual studio code) and how to use GitHub to store the code I’ve written incase anything goes terribly wrong and I want to restore to an earlier version. But it definitely helped me understand how to go about coding (which is to say: you google just about everything).

Here’s what I’ve learned so far (beyond that I should’ve respected computer science majors more in undergrad): websites are actually made up of three different coding languages—HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, you need to create a folder where your images, video, and other external content are sourced from (believe it or not, this took me a whole day to understand), and that coding is hard (given, I know).

Let’s talk about the three languages first. So, from what I’ve understood from the seemingly hundreds of YouTube videos I’ve watched, html is the structure—the words, the format; css is the style—the colour, the positioning; and JavaScript is the interactivity—the movement when you click. At first, I was trying to do all three languages in one coding file (which is possible) but that created a monster file in which I could find not a thing, so I’ve separated them. Now I have a bunch of different test files, most of which do one of the things I want (display the image, have a sidebar, play an animation when clicked, etc) and none do more than one thing.

A side note about the image issue. Basically, when you code all your code is stored in a file folder on your computer and everything you source in a line like <img src=”_________”> needs to be in the file folder. This is so basic that nobody online thought to mention it. You can imagine how stupid (but also deeply frustrated) I felt when I realized this.

I don’t want to put all my eggs in one basket, as they say. So I’m also looking around at different programs designed to make augmented reality and other alternatives. But I am really hoping that the html will come through. Because I’m coding from scratch, I get a lot more control over the entire project and in an ideal world, that would mean it should have an all around better outcome. But alas, I will search out the other options for science.

This is all to say: coding is way harder than I thought it would be. I get it—this project is supposed to be an experimentation of what digital public history can look like and trust me, I have been experimenting. But the perfectionist in me would really like this project to be nice at the end of this as well as be a learning experience. So I will continue to spend absurd amounts of time trying to learn coding.

I’m going to end this off my plugging last week’s post on genocide and word choice because I am very passionate about it. I swear, next week we talk all things photography.

Until then, stay savvy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Say What?: The Importance of Language and Word Choice in Genocide Studies

November 1, 2020

This past week we talked about dark tourism in class. This is right up my alley as in undergrad my focus was histories of violence. In particular, my focus was how violence has been commemorated. So, as I said—right up my alley. Despite this, I’d never actually considered the commodification of these sites. I’ve been so focused on how commemoration affects victims and survivors that I hadn’t ever considered who else would care.

Anyway, we talked very briefly about Auschwitz and we had an optional reading on the topic. I’m not actually going to name the reading because my comments are about discourse about the Holocaust generally and the reading just sparked a much bigger fire in my soul.

The main portion of this post will be about language and word choice—something that is deeply important to Holocaust studies (and if you ask me, all history).

The one that is most important is the use of the term concentration camp. I would search Twitter for this reference but I actually dislike Twitter and avoid it at all costs—I’ll just tell you the story instead.

A couple years ago, it was released that the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had separated families and interned them in concentration camps. The use of the term enraged some twitter users who couldn’t believe someone would compare an immigration detention centre to Auschwitz. I’m hoping you see where I’m going with this. The ICE camps are concentration camps. Auschwitz wasn’t (well, not really -- more on this in a moment).

Left: Concentration camps in Greater Germany. Right: the six killing centres

When I teach about the Holocaust, I use these maps because they telling you everything with just one look. Look at how many dots there are on the left, and those are just major camps. Compare it to the right. This contrast tells us everything we need to know.

The basic etymology here is that there were over 1000 concentration camps and sub-camps in German-occupied Europe and five (or six, depending on the scholar you ask) killing centres. The five were Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Chelmno, Sobibor, and Belzec (the sixth is Majdanek but recently some scholars have argued that Majdanek was a holding site for transfers to killing centres not a killing centre itself).

The difference is crucial to understanding how and why we use the term concentration camp in cases like the ICE centres. While concentrations camps did have lots of death via disease, torture, and starvation, their purpose was not solely to kill. They were meant to concentrate people into one area from which they couldn’t leave. Killing centres were solely designed for the purpose of killing.

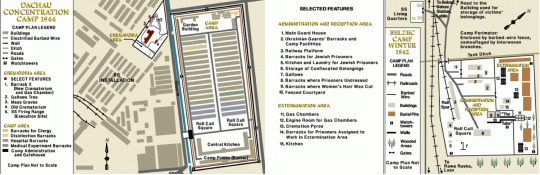

Left: map of Dachau concentration camp in 1944. Right: Map of Belzec killing centre 1942.

I also use these maps as they show the difference in an important way. Dachau is largely barracks (most of the long buildings are barracks with a few exceptions). Belzec has almost no barracks. That’s because almost every Jew transferred to Belzec would be killed immediately.

“But wait,” you say “I read Night/The Awakening/any other memoir of an Auschwitz survivor!”

And you have, you’re not wrong. Which is of course what makes this conversation so hard to squeeze into laymen’s terms (not that I think you’re laymen). I will explain this as basic as possible (so don’t come at me).

Auschwitz was actually a system of camps and sub-camps that we now use one term to describe. So, within what we now call Auschwitz there was a killing centre and a series of concentration camps—to make it difficult the Germans referred to them as Auschwitz I, II, and III (the killing centre was Auschwitz II). Basically, we use one term to describe more than one thing, convenient I know.

I could go on about this issue and why Auschwitz looms so large in popular history but Chelmno, Sobibor, Belzec, and Treblinka don’t. I won’t for the sake of not talking your ear off but let me know if you want to talk about it more.

I’m sticking to language for a second and talking about word choice. This isn’t the case for every scholar, but I was taught the majority of my undergrad Holocaust education by Doris Bergen and she really emphasized the importance of language. And so, I have continued this line of thinking.

Language is so hard when we talk about the Holocaust. What terms do we use? We use concentration camp (Konzentration Lager in German) but we don’t use KZ (the acronym used by guards and prisoners alike). * Do we use ‘Final Solution’? It’s the terminology of the Germans but in its subtext, it implies that Jewish life is a problem. Do we use extermination? Its use was directly meant to evoke thoughts of bugs and pests. Do we use euthanasia? It’s a euphemism and it directly contradicts what actually happened in the T4 program. Do we use T4? It’s also a euphemism. This an endless cycle. The answer I give is that we use the term when talking about planning and documents and terminology but when we talk about victims, we talk death and murder not extermination or euthanasia.

Let’s talk about the Wannsee Conference. Wannsee was a meeting on January 20, 1942 and has been cited in popular history as the ‘decision point for mass killings’. If you learned about it in high school, I wouldn’t be surprised if you were taught it was the start of mass killings. It wasn’t. Not even by a long shot. But it has often been depicted as such.

Here’s why it’s not the start of mass killings in any context. Mass killing in the T4 program began in 1938 via mass starvation and injection, mass death in Polish ghettos had been happening since occupation in September 1939, and the Holocaust by bullets had killed 1.5 million Jews in the USSR since invasion in 1941. So Wannsee wasn’t the beginning of mass death. But was it the beginning of gas chambers? No. Gas chambers were being used to kill in the T4 program as well as to kill Russian POWs as early as 1940. Okay… so was it the beginning of gas chambers in German-occupied Poland? No. Chelmno, the previously mentioned killing centre, opened 2 months before Wannsee in December 1941.

And yet, we are taught that Wannsee as this defining moment in the narrative of the Holocaust. I could do an analysis about why I think this is the case and I could cite modern scholars’ thoughts on what Wannsee actually was, but again, I want you stay awake.

The last thing that bothers me about popular understanding of the Holocaust is about the term genocide. Quick background: genocide was coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1933. Lemkin was a Polish law student who had watched the trial of Soghomon Tehlirian who killed Talaat Pasha.

I know those two names probably mean nothing to you. Pasha was instrumental in the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire between 1915 and 1921 (or 1917 depending on the scholar you ask).

Lemkin watched the trial and wondered why Pasha wasn’t tried for killing a million people (the popular estimate for the Armenian Genocide puts the death toll at about 1.5 million). And so, he began to develop a term that could be codified to ensure that people like Pasha could be tried for their crimes.

In the wake of the Holocaust, the world was confused about what to do in the face of mass death at the hands of the Germans. And Lemkin went to the UN to propose what he had proposed to the League of Nations in 1933. This time, they actually took the suggestion and drafted the Genocide Convention. **

This is a long-winded background, I know. But here’s the important bit—Lemkin based the definition off of the Armenian genocide, not the Holocaust. Despite the invocation of the law in 1948, the term itself is not inherently tied to the Holocaust. Why does this matter? Because of something Samantha Power calls the ‘Holocaust Standard’ which basically means that people compare all accusations of genocide against the Holocaust and if it’s not the same, it’s not genocide. You can see how this makes me angry.

This was very popular in Canada last summer when the MMIW commission came back and said ‘this is genocide’. You can imagine how many people turned to me and asked if I agreed expecting me to say no.

This is all to say: we need a total change in popular understanding of the Holocaust. Not only because it’s crucial to how we understand the history itself but also because the world today is influenced by our understanding of the Holocaust. From ICE detention centres to the MMIW commission, the Holocaust is living and breathing in the way we understand contemporary human rights discourse. And if it’s largely incorrect, where does that leave us?

If I made any mistakes in terms of dates, names, etc., let me know (I did this all on memory... whoops). And if you have questions or what to continue the conversation in the replies or my ask box, do it! If you can’t tell, I love having conversations like this.

I hope this was interesting/informative for you. Language and word choice are some of my favourite histories of violence topics and I could truly go on about it forever.

Next week I will actually post the photography thing I meant to, I swear.

Until then, stay savvy.

*I could easily go off about the term GULag in this moment, but I won’t.

**I would like to mention that Canada did not sign the Genocide Convention because they read it and said “umm that’s us, can’t sign that…”

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Changing Landscape of Museums

October 25, 2020

Before you read this, I recommend you watch Marvel’s Black Panther (for the purpose of this post but more importantly because it’s the best movie Marvel has ever released) or at least the scene in question and this TedTalk by Hannah Mason-Macklin.

I’ve spent many hours of my life thinking about repatriation, I’m sure that came through in my post about the Elgin Marbles. I’ve also spent a great deal of time thinking about my own role in museums as colonial institutions. I’m an optimist and I truly believe that museums can transform. Transform into what exactly has never been clear. In part, because I’m not sure that I, a white cis-het female, have the right to decide. So instead, I’m going to talk about the amazing points Mason-Macklin brings up and think about how we can begin to talk about the future of museums.

I’m going to start by talking a bit about the way this scene sets up the movie. Because Black Panther, again an amazing movie, has a lot of really important subtext. Eric Stevens, also known as Killmonger or by his Wakandan name N’Jadaka, is the villain of the movie. Or at least, he’s the closest thing the movie has to a villain. Killmonger, as his name suggests, is not opposed to violence which is why viewers are less inclined to support him. But his argument is actually valid and the movie ends (spoiler alert!) with the partial adoption of his views.

That’s part of the reason this scene is so important to me. The actual action of the scene barely matters to the plot. It’s really there to set up Killmonger’s psychology and beliefs. His anger towards colonial states and the legacy of colonialism is what drives his plot. He wants to give the power back to Black Americans and give them a chance reclaim their power. This scene is a perfect opener to that belief. Because he has the power to reclaim what is rightfully his.

This is important because in reality no one has this power. A colonial institution can possess something that rightfully belongs to you and your people and has the power to educate people about it incorrectly. And there’s very little accountability in that incorrectness. Museums are so powerful that they can incorrectly label an object and not listen to people when they tell them its incorrect. I wanted to open with this tangent about Black Panther generally before delving into what Mason-Macklin argues because I love this scene as the set up for the larger thesis of the movie.

Moving on to the content of the TedTalk. To me, the most important part of Mason-Macklin’s talk is about people. If you read my post about conservation you know that this is the hill I’ve chose to die on: the role of regular people in museums. I want them to have influence and say and purpose and I know that invites issues of critical thinking and popular history but it’s so important. If we exclude people from public narratives of history, how is that any better than our academic counterparts?

Mason-Macklin uses the Black Panther clip to talk about two different power-plays: knowledge and space. The knowledge power-play is about Western society prizing academic knowledge above all else. That’s part of the colonial heritage of museums. That we treat oral knowledge, cultural knowledge, as lesser because it doesn’t come from the colonial institutions of universities. A big part of decolonizing museums is going to have to be recognizing that and moving away from it. The museum expert shows disbelief at Killmonger’s statement that the artifact is from Wakanda. She immediately gets defensive and would have, had he not poisoned her drink, forced him out of the museum.

Museums as a tool for social healing is not necessarily a new idea. Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports around the world have recommended the creation of sites of memory and museums for decades. But this is different because instead of new museums being built, this is about museums changing. And that they will have to change. Mason-Macklin’s point is so good because she helps you think about the ways in which current museums can work within themselves to be better.

In a perfect world, repatriation would be the first step. But this is not a perfect world. And curators, educators, and regular museum staff aren’t usually the ones who make those decisions. And until the next generation can get into those positions of power, we will have to work with what we’ve got. Mason-Macklin shows you a way forward: using the tools you have to combat traditional narratives and asking yourself why those narratives exist.

The message here is about transparency and inclusion. It’s about recognizing the flaws of colonial institutions and working with the community against those flaws. This is not the perfect solution but obsession with perfection is what stops museums and so-called experts from doing anything.

Invite the people in. It’s their museum, you just work at it.

Next week, we will probably deep dive in photography. And then the week after, we are going to do it again.

Until then, stay savvy,

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love kids: that’s it, that’s the tweet

October 18, 2020

During my undergrad, I spent a lot of my time working with kids mainly because I really love kids but also because I love education. In lots of ways I view Public History as an alternative or an addition to traditional education. So as not to bore you, I have selected only a few of my “I love kids” experiences--these are the ones I feel are most topical.

I don’t want this blog post to sound like an entrance essay cataloguing my experiences in undergrad or a resume bragging about all the cool things I’ve done. But I wanted to talk about the wonderful ways I’ve worked with kids and I guess make the argument that kids want to learn, you just need to get to their level about it.

Let’s go in chronological order, shall we?

In my first year of undergrad I worked with UNICEF at UofT. I was a programme leader who would go to a Boys and Girls Club once every other week to teach grades 5s and 6s about the United Nations and the Declaration of Human Rights. We would spend two hours together talking about privilege, human rights, and identity. While we had planned activities for each session, often a large portion of the time was spent talking about the ideas after the activity.

Also, in my first year I worked with Engineers Without Borders to run a Social Change and Youth Leadership Conference. Before you ask – I applied to Queens Eng and worked with EWB as a high school student. It was two-day conference for high school students about the role of technology in social change. My job was to find people way smarter than me to run workshops I could barely follow. These kids were wild. They spent a weekend talking about engineering theory and applied mathematics and I spent most of the time in awe and silent.

In the summer of 2019, I took four 11-year-old kids to Germany for a month. It was through Children’s International Summer Villages (CISV) who I had travelled with as a child. The idea is that 12 delegations from 12 different countries come together for 4 weeks for a camp. The camp is centered around four pillars: conflict resolution, human rights, diversity, and sustainability. Basically, there are about around 70 spaces for activities—12 of those were taken up by each delegation teaching the camp about their country. The rest were activities designed by me and 11 other ‘adults’ that surrounded the four pillars. We did everything from classic games like Lifeboat to complex simulations. After every big activity, we would debrief as a delegation. This gave my kids a chance to reflect on the ideas the activity had brought up and connect them to life at home. I have never consistently slept less in my life. On average, I slept 3 hours a night. It was the greatest four weeks of my life.

A selection of photographic proof of me losing my mind. I would put up an adorable photo of me and my kids here but strangers on the internet might read this. If you want to see it go to my instagram.

Most recently I spent a week at my alma mater high school teaching a grade 10 class. I reached out to one of my favourite teachers and offered to come back and volunteer with him—the perks of being a lifelong teacher’s pet, I guess. He was happy to have me in and I actually taught for an entire week by myself (he was nearby but rarely in the room).

I spent Holocaust Awareness Week teaching a class of grade 10s about the Holocaust. It was a blast, well as much as it can be with a subject matter like that. I was initially concerned that the students wouldn’t be very engaged. Turns out that should’ve been the least of my concerns. Twice we got stuck down rabbit holes that left us falling behind the planned schedule. On the Wednesday I was teaching about the non-Jewish victims of the Germans and I was concerned that we would have too much extra time at the end, we didn’t even finish the lesson that day.

I didn’t go over this to brag about all the things I’ve done with kids, although I do love bragging about my CISV kids. I wanted to talk about this because I deeply believe that kids are engaged with history.

Most kids love learning. And most kids love asking questions. It’s about presenting information in a way that they can engage with. And even more importantly, it’s about emphasizing how asking questions is the foundation of all knowledge.

We recently discussed the issue of trying to teach non-historians to think historically. This can be really difficult for adults who have preconceived ideas about the past, but for kids, questions are second nature. Kids don’t mind when you say, “well actually, historians debate this all the time” or “well, considering the evidence, what do you think?” because it invites them in. They want to have a seat at the table and when you give it to them, they engage with you.

It’s school itself that teaches us not to engage. It teaches us that retention is all that matters and that asking questions only slows down the learning process. Slows down??? Son, questions are the learning process.

In each of these experiences, the kids I worked with were engaged and interested. They asked thought provoking questions and wanted to know more and more and more (until I eventually had to say “guys, I actually don’t know” or “this is way too far off topic”). I’m not saying this is because I’m some sort of god of teaching or anything. I’m saying this because kids want to learn, they really do, they just don’t want to be talked at, and honestly, who does?

This has been a very long winded way of saying that I think educating kids isn’t as difficult as it might initially seem. Kids like to talk, they like to ask questions, and they will engage – just get on their level!!

My schedule for posts is wild. Thinking next week will be about photography .. or maybe Marvel’s Black Panther. Stay tuned.

Until then, stay savvy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Understanding Transitional Justice

October 13, 2020

Last week Tim brought up my podcasting post at the beginning of class. He actually wanted to talk about transitional justice more than he wanted to talk about podcasting, something I was definitely okay with. Since then, I cannot stop thinking about it. A fair warning: this is absurdly long, like way too long, but I’m obsessed with these questions and have been struggling to cut myself off. In all honesty I wanted this to be about 1000 words longer. Transitional justice is one of those topics that has so many unanswerable questions that you fall down a rabbit hole all the time.

For those reading who aren’t in the class, Tim had asked my opinion on the comments of a French public historian at a conference in 2017 in Bogotá, Columbia. This man had said that following WWII France chose to consign the actions of the Germans and the collaborators to oblivion. They chose to let these issues rest for a couple decades and pick them back up when the wounds had scabbed over. I should be clear, the Frenchman is not the only person to hold this belief, not by a long shot. Individuals, often individuals in power, in every country facing questions of transitional justice have advocated for some form of forgetting.

This view of transitional justice is outdated and it ignores so much of what transitional justice is.

Transitional justice is not about criminal justice. Or at least, not entirely. It can certainly be about holding perpetrators accountable for crimes through the legal system; but often that is largely impossible. Here are some examples: in Chile, the former dictator was still head of the military and had threatened attack if anyone was tried; in Rwanda, the number of perpetrators was so large that it overwhelmed the prison system; in South Africa, there was a controversial Amnesty for Truth law that gave perpetrators amnesty if they testified in court. In cases like Argentina, Germany, and Peru successful trials have brought down the very heads of the institutions that committed the crimes but have largely left low-ranking individuals alone. Legal justice is only a small portion of the larger discussion on transitional justice.

So, what else is there? Well first I’m going to plug my podcast because who would I be if I didn’t? Listen here to hear me talk about an amazing memorial in Paine, Chile.

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs), the creation of memorials and museums, and reparations are three of the biggest forms of non-legal transitional justice. TRCs are government funded commissions that use oral history and traditional research methods to uncover what happened. They create the state narrative and become the beacon for government work.

Memorials and museums can be both private and public and can serve the state or serve the people. If you’re interested in this (which I imagine some of you might be) I have a good deal of knowledge on this part of transitional justice particularly in (can you guess?) Chile and also the former USSR, Germany, and Argentina.

Finally, we have reparations. We might imagine reparations to be cheques handed out once or monthly or yearly to victims or victims’ families. And reparations can be cheques given to individuals, but they can also be sustained investment into infrastructure. This is particularly important when talking about traditionally underserved communities – for example the Mapuche in Chile or, oh would you look at that, Indigenous communities in Canada. This can be controversial because it brings up questions of who you consult about infrastructure changes, how you prioritize issues, and how you split funding (didn’t I tell you, there are tons of unanswerable questions in this field).

Each of these three methods do not involve the legal system. Instead, they work to rebuild the social fabric of a country in the wake of devastation. They provide truth, memory, and restoration and they provide justice. We just need to reframe what justice means.

When we think of transitional justice as criminal justice, we imagine the black and white world of a judicial verdict. We imagine that transitional justice will solve everything and make the world whole again. It won’t. It can’t. It never will. Massive human rights violations are irreversible, they tear through lives and communities, social structures and societal ideals. Instead, transitional justice is about holding systems accountable and reforming them; it’s not about the individual who committed the crime, but rather about the system that allowed, accepted, or authorized the crime.

I really got lost on a tangent there but now you know a little more about what transitional justice looks like on the ground.

Back to the Frenchman. His argument centres on the idea that talking about recent crimes only serves to re-traumatize victims. He’s not wrong in this idea but his solution is too encompassing. Instead of silence as a national policy, transitional justice allows for silence as a personal choice. All TRCs and trials are self-selected meaning the victim choses to tell their story. This isn’t a perfect solution, but it allows the victim the dignity of choice and the ability to put their own needs first.

France is a unique case. They could say, “well it’s time to forget what the Germans did to us” (this ignores the roles of collaborators, but it still works). France as a country could project all of the crime onto an ‘other’, who were truly an other because they left. Again, we’re ignoring collaborators. Almost no other country has this option. In Rwanda, when the civil war and genocide subsided, no one left. The same can be said for South Africa, Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, Peru, Canada and the list could go on forever. So, we need transitional justice to mediate the relationship between the victims and perpetrators as they co-exist in a single society.

The 1990 National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report in Chile explains the need for transitional justice quite well. In the introduction, they wrote “although the truth cannot really in itself dispense justice, it does put an end to many a continued injustice – it does not bring the dead back to life, but it brings them out from silence: for the families of the ‘disappeared,’ the truth about their fate would mean, at last, the end to an anguishing, endless search.” (The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report, “Introduction,” 14.)

I hope my ramblings on transitional justice have been informative. It’s not perfect, it’s not black and white, but it’s necessary. There is no healing in silence for society, that is an individual choice. Society is not allowed that privilege as the systems that allowed the violence must be held accountable for that violence.

Next week is undecided. Let me know if you have any suggestions for what I write about.

Until then, stay savvy.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Elgin Marbles and What They Mean for Repatriation Generally

October 6, 2020

This blog post is, in part, a response to @thefolliesofmen. She did an amazing job historicizing this conversation and talking about the issues of identity that surround it. Check out her blog to learn more about Phidias, Lord Elgin, and the historical issues at play here.

I’m really shooting myself in the foot with this post as I would actually love to work at the British Museum. But I feel passionately enough about repatriation that I don’t really mind.

I have always known the sculptures as the Elgin Marbles and will continue to refer to them as such. The British Museum now refers to them as the Pantheon Sculptures. And while I appreciate this because it actually acknowledges where they came from, I have an inkling that they changed the name to help people forget about the complicated acquisition of the pieces.

The Ladies (Hestia, Dione, and Aphrodite) Source

Let’s begin with the argument. The British Museum has a section of their website dedicated to this issue. Read that here (basic info) and here (Trustee’s Statement). I’m going to look mainly at the Trustee’s Statement for the sake of brevity.

Let’s breakdown what the article says.

They discuss the legality of their claim to ownership, they obviously argue they own them. I won’t go into much detail on whether the British Museum can claim ownership as Victoria described the issue perfectly in her post. What I will say is that we aren’t sure - and that goes both ways. Maybe they do have legal claim. Maybe they don’t. The issue is that the British Museum doesn’t acknowledge this. They unambiguously claim ownership.

Then, the British Museum argues that the marbles in their museum give context to the larger thesis of the museum. I can understand this. The Elgin Marbles represent Ancient Greece in this larger world history the British Museum is trying to teach people about. I’m not going to argue against this.

I will also tack onto this section something Victorian brought up. Can modern Greece claim ownership over ancient Greece? This is obviously a complex question about identity and ownership. But who told the British Museum they got to decide? And if modern Greece can’t lay claim to these items, modern Britain certainly can’t.

The second argument is that the split between Athens and London is good because more people can appreciate the sculptures every year. Also, true, I guess.

Remember when I said I was going to shoot myself in the foot? Bet you’re wondering what happened. Don’t worry it’s coming.

The Frieze (the Pan-Athenaic festival) Source

Unequivocally, the British government, and by extension the British Museum, needs to give the Elgin Marbles back to Greece.

And guess what? It doesn’t have to change either of those lovely arguments up there. Because the beauty of modern technology can help solve the supposed problem. And you know what, the Acropolis Museum has already done it for us.

I’ll stop with the suspense. The answer is casts. For those who don’t know what casts are: I’m basically arguing for replicas to take the place of the real sculptures in the British Museum. The beauty of this argument is that the only issue the British Museum can have with it is that they legally own the sculptures. Which remember, can’t be proven by unbiased historians.

Let’s flush out this argument. Casts, which by the way are pretty common, would provide the British Museum with exact replicas that would teach visitors about Ancient Greece in the context of world history. Perfect. They would also, in essence, keep the 50/50 split that allows more people to engage with the marbles on a daily basis. Awesome.

This is obviously an oversimplification but it makes the larger point that the issue is not as black and white as it might first appear. Casts are the best of both worlds because they allow Greece to retain its heritage while also continuing the mandate of the British Museum. I know that this won’t happen, but a girl can throw out ludicrous ideas and make them sound totally doable, can’t she?

Visitor looks at fragments of pediment statues Source

My big problem is that the British Museum’s refusal to give back the Elgin Marbles is evidence of a larger systemic problem. Greece is a European country with a well agreed upon history. And the British Museum won’t give them back that heritage we clearly know is theirs. What does that mean for the other objects the British Museum and other museums like it house? Nothing good, if you ask me.

This issue is reflective of the British Museum’s, and by extension the British government’s, inability to admit to wrongdoing and begin the repatriation process. And that doesn’t bode well. The world is changing. People are beginning to talk about repatriation outside of museum circles. I see calls for repatriation on my instagram feed. The next generation won’t sit back and accept these excuses. It would be in the British Museum’s best interest to repatriate the Elgin Marbles before it’s too late.

I want to finish off by saying I know this problem isn’t simple. The ‘they’ we talk about is ambiguous. There’s no one person we can blame for this. There’s no curator or director who can make this call. The British Museum is a large, bureaucratic institution that cannot let a decision of this size sit on any one person’s shoulders. And this is the problem with large, government-funded institutions. Who makes this call? We don’t know.

Sorry to end on such a sad note. But the reality is this issue is larger than one person. But I do believe that movement from within the British Museum needs to begin. Directors and curators, while they can’t make the final decision, can advocate for change. And that’s really where we begin - from the inside.

If you got all the way here, congratulations. This would’ve been longer but I had to curtail myself. Next week we’re going back to last week’s topic because I haven’t said everything I need to on transitional justice.

Until then, stay savvy.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcast!

Remember the post about how hard podcasting is?

Well, here is the final product.

Click Here to listen to me talk about all things transitional justice and Chile.

1 note

·

View note