Text

Overpowered Characters Done Right: The Disastrous Life of Saiki K

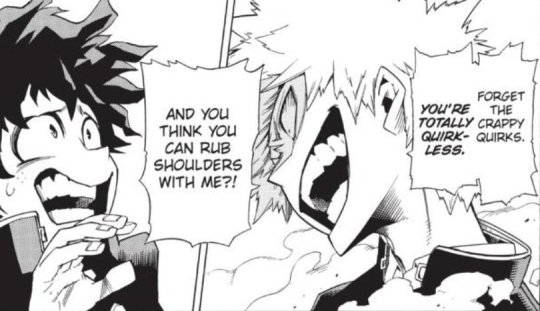

We’ve all seen overpowered characters, and we all know what tends to happen, at least in shonen battle anime… The main characters grow and grow until they’re at the top of their respective hierarchies, but, once they’ve reached that point, where is there to go? What challenges could they possibly face? Well, the most common answer is to simply make the antagonists level up at a similar rate. But there comes a point where this solution becomes a bit… repetitive. Right?

Now, don’t get me wrong. Maybe you enjoy those intense fights, and there’s nothing wrong with that. They can be fun, I’ll admit. But when it comes to the point where it’s obvious what the author is trying to accomplish — when it’s obvious that the antagonists are extremely powerful (and usually come out of nowhere for lack of better planning) because if they weren’t, the fight would be over in a couple of seconds — it loses a certain thrill, doesn’t it? It’s just not the same as a battle that tests the strengths of a protagonist still climbing the ranks. A battle that will judge whether the protagonist’s training has led to any newfound power, or if they haven’t grown at all.

Now, with a character unable to climb simply because they’ve already reached the top, the only option for an opponent is someone who’s slightly weaker. An opponent they’ll struggle with but ultimately defeat. And we tend to know that’ll be the outcome.

(Unless, of course, the author decides to kill off the protagonist with a stronger opponent, but that doesn’t often happen, does it? And if it does, we don’t really have the problem of them being overpowered anymore… Coming in from a different angle, it’s generally better for battle shonen to simply end when the protagonist and friends have reached such a high level and have achieved their goals. But there’s always money to be earned with dragging them on…)

Anyway.

Before I get into it, let me first address the elephant in the room. Yes, battle shonen and a character-based comedy like The Disastrous Life of Saiki K aren’t exactly the same kind of anime. But, overall, the conclusion is the same.

What conclusions we can draw from using Saiki as an example of how to create conflict with an overpowered character can be transferred to any genre with a little tweaking. It almost isn’t even about transferring. No, The Disastrous Life of Saiki K proves that there is no excuse for a lack of conflict in shows/movies/novels/etc. with overpowered characters. While battle shonen tend to be the ones with overpowered characters and (almost) equally overpowered villains, that was merely an example to provide a basis of thought.

Now, let’s actually start discussing the answer to the question I’ve only been prodding at so far.

So… what conflict can you really create with a protagonist who is unbeatable?

Well, The Disastrous Life of Saiki K reveals the surprisingly simple answer to this question: when your character is too overpowered to give them an interesting antagonist to create conflict, you’ve got to branch out a little.

In other words, make the “overpowered-ness” itself the conflict.

…

The Disastrous Life of Saiki K— one of my favorite anime of all time. With the main character a psychic in a world full of ordinary and comparably powerless people, how can this anime be worth watching?

Easy. Saiki dislikes the fact that he has his powers.

This is clear to see throughout the show. I mean, remember how excited he got when he found the germanium ring that cancelled out his telepathy? Or when Kusuke offered to take away his powers completely? And that’s just it. Saiki doesn’t like his powers because they create problems for him. Sure, he can solve nearly every outside problem with them, but when the problems are his own powers’ doing…

Saiki’s problems stem from the fact that he has them— bending spoons makes it hard to eat, telepathy eliminates the possibility of surprise parties, and winning free popsicles leads to stomachaches. In his own words:

In one episode, he accidentally turns Nendo to stone after his glasses break, and the rest of the episode’s major conflict is ensuring Nendo — now a statue — isn’t destroyed (and therefore killed) before Saiki’s medusa-inspired power wears off after 24 hours.

In another episode, Teruhashi removes one of his power-suppressing hairpins, and he accidentally teleports the hotel housing his classmates out to sea in his sleep. He then has to figure out what happened to the hotel and try to fix the mess he caused. Furthermore, he teleports Teruhashi, and to keep her from discovering his powers, he must convince her she is lucid-dreaming.

And, of course, Saiki doesn’t want anyone to know he has psychic powers, and therefore many of his problems are caused by the fact that he has to work around that limitation. Yet another example of a potential conflict that authors can give overpowered characters.

These are just a few examples of his overpowered-ness causing trouble for him. Through these examples, and through Saiki’s obvious disliking of his own physic powers, it’s clear to see they’re just as much of a curse as they are a blessing. To Saiki, they’re more of a curse. And curses tend to involve conflict in some way or another, don’t they?

And there you have it— I don’t really have much else to say. I don’t think I need to say much more.

So I will leave with this: the constant tomfoolery that is each five-minute episode of The Disastrous Life of Saiki K is filled to the brim with conflict, often created by Saiki’s powers. His extremely overpowered powers. Most impressively, these powers were never used to fight against antagonists of a similar power level. After all, it isn’t that kind of anime. Therefore, the author had to create conflict without relying on the protagonist and antagonist duking it out. And that he did.

And, without conflict, you really don’t have a story. At least, not a very good one.

...

(If any of you were thinking that One Punch Man would’ve made a more appropriate anime to base my argument around after I opened with a mention of battle shonen anime, you’re absolutely right. It would’ve. While One Punch Man isn’t really shonen, it still revolves around a hero fighting villains, as opposed to Saiki K’s more character-based shenanigans. Saitama even does fight villains that are overpowered, though they can only be considered as such when compared to any hero who isn’t Saitama.

But where’s the fun in using an easy example? Besides, it still doesn’t fit perfectly. It’s only a bit more related.

There’s a reason why One Punch Man is well-loved (at least the first season, that is). It’s fun. It’s compelling. It balances action and comedy quite well. And its conflict isn’t so much Saitama fighting villains — because, after all, it’s not much of a fight after he throws a single punch — as it is his inability to have fun. There’s no thrill in fighting when there’s no fighting at all, is there? He can’t seem to find a worthy opponent, and that’s great conflict.)

…

So, in the end, there’s really no excuse for authors to skimp on the conflict in their stories. There’s no character too overpowered to render conflict impossible. You just might have to think outside the box a little.

And no excuse for not having overpowered characters! If you want to write a character who, at the start of the first episode or on the first page, is already sitting atop a mighty pedestal, go for it. No reason you can’t make a compelling story from that.

#the disastrous life of saiki k.#saiki k#saiki no psi nan#anime analysis#manga analysis#one punch man

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Jujutsu Kaisen’s First Episode is So Good

Today, I want to take a look at JJK’s first episode and how its structure makes it one of the best anime first episodes I’ve ever seen.

At first, I wanted to make this another installment of my The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly series, but I don’t think the way those analyses are organized would do this episode justice. I’m going to tackle this analysis in a more linear way than that series. I’ll still be giving JJK’s first episode a grade at the end, though. It’s still a first episode, after all. And it’s too fun not to.

So, without further ado, let’s get into it.

...

The episode doesn’t start off on a bad note:

The first character we actually see (Gojo) doesn’t appear again until the second episode, which is a little strange, but it’s nothing necessarily bad. Normally, it’d be best to first introduce us to Itadori. But it’s part of this opening scene’s intrigue, in a way.

Having Gojo be introduced first only to immediately disappear raises some questions throughout the rest of the episode. Obviously, he’s got to be important to the story to be shown first. So where the hell did he go? This, combined with the fact that Itadori’s set to be executed while clearly oblivious as to why makes for an opening scene full of questions. ‘Who are they?’ for one, of course. But more than that: ‘Why does this teacher at Jujutsu Tech want to execute a boy who seemingly has no idea what he did to get there?’ And: ‘What’s Jujutsu Tech?’

Despite this scene lacking a gripping opening line — the opening line is Gojo saying “good morning” — it still keeps us interested enough to keep watching. It raises too many questions we want answered to not do so.

The tension in this opening scene is palpable, and that’s what makes it good. Stories are all about tension.

...

Moving on... the inciting incident occurs at the end of the episode; therefore, everything before then is setup.

Before getting too deep into any breakdown of the setup in this episode, I’d like to mention that setup and backstory are often seen as one in the first episode of any show. But this isn’t so— at least, they shouldn’t be. Setup is necessary in a first episode, but backstory isn’t.

Setup is introducing us to a protagonist’s ordinary world so that we can get a sense of the difference between what they’re used to and what they’re about to face. Backstory is essentially anything that comes before the story, and it’s often what we find in lengthy info-dumps that interrupt the flow of a story. Backstory is needed sometimes, but it’s far better slipped into a story in moderation, not dumped onto a reader at the very beginning. A literary agent would take one look at a heap of backstory in the first chapter of a novel and toss it in the reject pile. If it can be done respectfully in a first episode, then I’m on board. But usually it’s not needed right up front.

Which is why it’s so refreshing to see that JJK’s first episode has not a trace of backstory anywhere. Overall, this episode is really strong, and I think the lack of backstory plays a role in that.

Furthermore, the setup in this episode is tremendously well done.

You see, before the inciting incident, we must first be introduced to our protagonist’s ordinary world. ('Inciting incident’ is the name for the event that sets the protagonist on the story’s main journey.) But their ordinary world is going to be more boring than the new world they’re going to find themselves in for the majority of the story. Therefore, we need some tension to make the setup before the inciting incident more interesting. Because if it’s too boring (or too long), chances are the audience is going to give up before the story gets anywhere.

There’s plenty of tension in this episode, and it’s almost all thanks to Fushiguro and his quest:

Every once in a while, Itadori’s POV is interrupted in the best way possible by Fushiguro on his search for Sukuna’s finger. This is where the true tension of the episode builds. While Fushiguro’s scenes focus on building the tension of the ‘curse problem’ that culminates at the end of the episode, Itadori’s scenes focus on introducing us to our protagonist. The constant trouble that we’re reminded of every time Fushiguro is on screen plus the promise of Itadori somehow being involved (it’s a story, after all—he has to be involved somehow) makes for an engaging first episode.

And we can’t forget how Itadori is plenty interesting enough to keep the audience engaged without all that promise of trouble to come. Not to say that promise is bad! But we get a great sense of who Itadori is in this episode, and he’s awfully likable and fun. We can tell he’s going to be a complex character worth following.

...

Before I start on the next section, I can’t neglect to mention how there’s no trace of forced dialogue anywhere in this episode! Not even in the setup, where it’s most common. There’s no sign of anyone mentioning anything that they know good and well just because the audience doesn’t know it. And nothing is lost because of it!

We still manage to learn that Itadori’s got some superhuman strength (which would be strange if it appeared out of nowhere later in the episode, when he fights those curses with Fushiguro). We still manage to learn that he’s in the occult club. And that he isn’t afraid of ghosts despite his upperclassmen being terrified of them, and he tags along with them when they go to haunted places for moral support. (Which is a form of specificity— it’s something that truly makes a complex and lovable character. And you bet I laughed when that image popped up of his upperclassmen cowering behind him as he strolled so nonchalantly. How could I not like Itadori’s character?)

This is how a first episode should be done. This is showing (rather than telling) at its finest.

...

Just by the way Itadori is depicted in this episode, through his dialogue and his actions, we can tell he’s going to be a complex character. (The best kind of character!) Not only through his dialogue and actions, though. His promise of complexity is ensured the moment the story-worthy problem is introduced.

(There are two kinds of ‘problems’ in stories: the story-worthy problem and the surface-level problems. The surface-level problems are the ones that are easy to spot— for example, defeating Loki in the The Avengers. There are dozens, even hundreds, of surface-level problems in a story. After all, to defeat Loki, didn’t they have to recruit each Avenger, stop Loki in Stuttgart, and take down the Chitauri army during the climax? And those are only three. But there’s usually only one (or a few if there’s a large cast of important characters) story-worthy problem. These are the problems that are associated with a character arc. Take The Avengers again— didn’t Tony Stark demonstrate how he learned to make sacrifices for others when he redirected the missile into the wormhole at the end? Tony’s story-worthy problem was being too selfish.)

The idea of Itadori’s story-worthy problem is introduced in this episode’s setup:

It’s when his grandfather tells him to help others and not to waste his life.

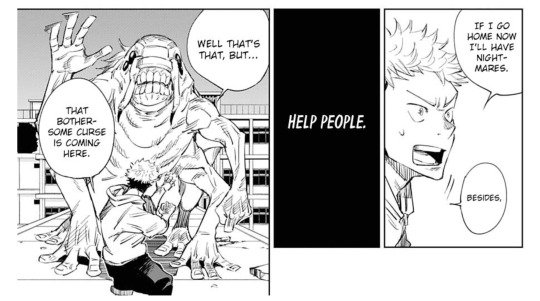

Now, while Itadori interprets this in his own way — I’ll discuss why this is great later — the beginning is there. His acceptance of his grandfather’s advice (with his own twist) is going to be his story-worthy problem. The episode wants you to know it, too. After all, Itadori references his grandfather’s words during his and Fushiguro’s fight with the biggest curse:

(I’m using the manga to keep everything succinct.)

He’s clearly accepted his grandfather’s advice, though he’s taken more to the idea of giving people proper deaths. Of course, this still manifests in him wanting to help people, as not helping them would very likely lead to their untimely demises. Like how he helps Fushiguro in this scene.

The development of his character will be based on this desire to fulfill his grandfather’s dying wishes and how his views of that desire change as he faces more and more surface-level problems. This is what makes it a story-worthy problem.

Every good story needs both a story-worthy problem and many surface-level problems, because a story with just the latter wouldn’t be much of a story at all. We want to see characters change, whether it’s for the better or for the worse. Your story’s surface-level problems would have to be pretty interesting to keep an audience interested for the entire duration if there’s no story-worthy problem to be seen. Even then, your audience isn’t going to leave your work with much satisfaction. The story-worthy problem is what gives meaning to your specific characters being a part of your story. Why not just any old gaggle of characters? The story-worthy problem also what holds the structure of a story together.

The inciting incident is the best place to introduce the initial surface-level problem and hint towards the story-worthy problem. Itadori saying he’s got his own curse to deal with is about as big of a hint as we could get. It’s fantastic! It’s no good when the story-worthy problem is too difficult to even pinpoint.

Sometimes, it’s difficult to determine what event is the true inciting incident of a story. But the true inciting incident will always be wherever the story is kickstarted plus wherever the story-worthy problem is hinted at. Therefore, the inciting incident of JJK occurs when Itadori helps Fushiguro take down the curse and eats Sukuna’s finger to do so. (Usually it’s not quite so obvious what the story-worthy problem is, but it certainly works in this case!) After all, the story-worthy problem is clearly there, and as soon as he eats Sukuna’s finger, he’s secured himself a spot in a world he’s never been a part of before. If he hadn’t eaten the finger, he could’ve gone back to his normal life after the curse was defeated.

Therefore, JJK succeeds in giving us an inciting incident that accomplishes exactly what it needs to do in a way that deserves nothing but praise.

...

Earlier, I mentioned that I needed to discuss why Itadori interpreting his grandfather’s words in his own way is important. Well, it all has to do with agency.

Protagonists need agency. In other words, they need to decide things for themselves. They need to be active. Passive protagonists who are simply dragged around by the plot and do anything necessary to keep the plot going are the worst kinds of protagonists. They’re the protagonists we get bored of at best, hate at worst. I mean, they can’t do anything for themselves. Who wants to follow a doormat through a story?

Itadori is certainly following his grandfather’s advice, but he gave it a meaning that suited him more. He isn’t really following his grandfather’s words blindly. Another example: when he eats Sukuna’s finger. Fushiguro didn’t tell him to do that. Fushiguro only mentioned that the curse wanted to eat it to gain power. It was completely Itadori’s decision.

Therefore, right off the bat, our protagonist is making decisions for himself, even while being thrown (unwillingly) into an entirely foreign world.

...

I can’t end this analysis without first mentioning how well everything in this episode fits together.

I mean, come on... Itadori’s in the occult club, which is how he knew where Sukuna’s finger went, and because his upperclassmen are in the occult club, they wanted to investigate a cursed object. It was mandatory to join a club, and the occult club finishes before five, which is how Itadori could visit his grandfather and hear his grandfather’s advice (which would become the story-worthy problem).

And what about the occult club’s presentation of their research project to the student council president? They theorize that there’s a dead body buried in the rugby field, and that’s why the rugby players kept falling ill and had to be hospitalized...

Then, later, when Fushiguro walks to the rugby field, he spots a curse and asks himself, “Is there a dead body buried here or something?”

This episode is fantastic!

...

Well, I believe that’s about all I wanted to cover in this post. Everything else is a bit too minor to include, and I don’t want to make this too long. So, let’s hurry up and get to the grade for this episode.

I’m giving it an A+. It absolutely deserves it. I can’t think of another anime’s first episode that I would even consider rating this high. (Even giving Dr. Stone’s first episode an A- was a bit generous, honestly.)

Good for Jujutsu Kaisen!

...

#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#jjk anime#jjk analysis#fushiguro megumi#itadori yuuji#gojo satoru#jujutsu megumi#jujutsu gojo#jujutsu itadori#manga analysis#anime analysis

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly: Soul Eater Episode 1

Time for another installment of my new series: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly! (I regret naming it this now. It’s got such a nice ring, but it’s just so long.) Once again, The Good category will be for anything done well/exceptionally, The Bad will be for things that aren’t so great, and The Ugly will be for particularly egregious parts of the episode.

This time, I’ll be analyzing Soul Eater. I’ll be exclusively discussing the anime, because the first chapter of the manga is different. It actually doesn’t have many of the issues that I want to point out today. It seems the writers for the anime made it worse.

I’ve got to say, before I even begin, this one’s a bit of a doozy. Soul Eater’s first episode is much worse than Dr. Stone’s. Not bad enough to keep me from watching the next episode, but it could certainly be much better.

But enough intro. Let’s get into it.

...

THE GOOD:

Unfortunately, there’s not much for me to put in this category. But there are two things: the opening line and Maka and Soul’s characterizations.

First, the opening line.

“A sound soul dwells within a sound mind and a sound body.”

Now, frankly, opening lines aren’t all that important. (In my opinion. Some people will vehemently argue with me on that, I’m sure.) I don’t think anyone is going to drop an anime immediately if the opening line doesn’t meet their standards. If an opening line is memorable, that’s great. But it doesn’t have to be. It just needs to get the story going in one way or another. Maybe pose a question or set the tone or introduce us to an important world-building detail.

This line accomplishes the first. It doesn’t immediately throw us into some action but rather intrigues us by raising some questions. How are souls important in the story? What defines a sound soul/mind/body in this world? What happens if you don’t have a sound mind or a sound body? Only the first is answered in this episode, which forces you to watch more if you want answers to the rest.

Overall, the line’s not bad at all. It’s memorable, in a way. And it’s got a nice ring to it.

Next comes Maka and Soul’s characterizations.

This ties in to some grievances I have in the Ugly category, because the way they talk to each other throughout the episode is often remarkably forced and unnatural. But, when they are being themselves rather than vehicles for unnecessary exposition, we get exchanges like:

(These clearly aren’t from the first episode, but I couldn’t find any good gifs of their dynamic in the first. And screencaps don’t really work when subtitles are split so often. These still prove my point and are similar to their interactions in the first episode. Sue me.)

Their dynamic is compelling. It’s fun. It’s new. And it’s really this episode’s saving grace.

They argue constantly but still work so well together when they’re fighting Blair. We can tell just how different they are from each other by the way they interact. Even when they argue for real, they can still be partners and trust each other. This is made obvious throughout the episode just by how they talk and act around each other. It’s gripping and makes the audience like them because, in these instances, they’re genuine and relatable. They act like people — partners — and not simple characters. They’re not spouting information they already know for the sake of the viewer.

Additionally, Maka’s hatred of men because of her father isn’t something you see in anime everyday. It’s quite telling of how she perceives the world and how she’s been damaged by her father’s actions. It’s specificity— she didn’t have to be portrayed as a misandrist to be an interesting character. But giving her that specificity, that detail born from cause and effect, makes her much more complex and believable as a person.

...

THE BAD:

Not much in this category either. The only thing I want to touch on is the logic in this episode.

If Death is so worried about Maka and Soul fighting a witch because it’s so dangerous, why not send someone out to supervise them? Someone who could easily kill Blair but wouldn’t interfere unless they believed Maka or Soul were about to die. That way, we’d get to see our two main characters fight without anyone getting in the way. Instead, the writers came up with a lame excuse to, well, excuse Maka and Soul’s isolation. It’s similar to the ever-popular tactic YA authors tend to use: they kill off a protagonist’s parents so their child can embark on a treacherous quest without anyone interfering.

We should be focusing on the main characters. Especially in the first episode. But the way they’re completely alone still doesn’t make sense. If you don’t want to lose a meister and weapon pair with such great potential, then why send them off to their possible deaths? There’s no good reason Maka and Soul have to do it completely on their own.

And, yes, the writers do include Death attempting to justify it. By implying they need to prove themselves on their own. Even so, that’s not a valid reason to leave them at Blair’s mercy if they’re not ready. A supervisor wouldn’t interfere until they’ve clearly demonstrated they aren’t skilled enough to fight a “witch”. Death could confiscate their 99 kishin souls all the same. It’s just plain stupid!

(This was the best image I could find. Netflix wasn’t cooperating. I’m sorry. I really did try.)

Before I move on... While Soul pretending to betray Maka only to kill Blair sure was a good trick and a great way to show the levels of trust between the two, why the hell did they wait so long? Blair just stood and waited for Soul and Maka to kill her when she had plenty of time to escape. They were pretty obvious about what they were doing. Blair had no reason to be confused enough to just sit around.

...

THE UGLY:

Time for the real issue: exposition. So. Much. Exposition. Unnecessary exposition, too!

I’ve explained why showing vs. telling is so necessary (in cases like this) in a previous post, so I won’t go into too much detail this time. I’ll give you the SparkNotes version. Essentially, showing vs. telling helps get the audience invested in the story. Even though we don’t realize it, we, the audience, want to work for our information. It’s boring when it’s handed to us on a silver platter. Every time we have to sit through major info-dumps like the ones I’m about to mention, we’re pulled out of the story. It sucks.

So let’s start with the opening scene:

The camera spirals around the DWMA and doles out a depiction of a Kishin as the narrator info-dumps the basic world-building onto us all at once. The narrator states: “Welcome to Death Weapon Meister Academy. Commonly known as the DWMA, it stands as a defense against the forces of evil, which would plunge the world into chaos and drag humanity to the very depths of fear and madness. The demons known as kishins, and their insatiable hunger for destruction. To ensure the kishins never regain their hold on this world, this academy was founded by the Grim Reaper, Death himself.” A little more information about the school is given by Death, and the scene ends.

Did you want to read all of that? I sure didn’t. It hurts my eyes looking at a quote that long. (I say as I write multiple paragraphs much longer in every post. It’s not the same, I swear.)

We’re not going to remember any of this. Not unless we rewatch it over and over. And who wants to take the time to rewind the first episode of a show to memorize a bunch of information that they can’t ground anywhere? We aren’t invested in the characters or the story yet. We haven’t even seen our main characters yet! Therefore, we sure as hell aren’t invested in the world enough to care.

We don’t want to put in this kind of work unless we believe we’ll be rewarded by doing so. (Our reward being enjoying the show.) While it would still be substandard to tell the audience everything important about the world in this manner, if it had been given to us after we got to know Maka and Soul and the other five, at least we’d probably care. At least we’d be invested enough in these interesting characters with interesting dynamics enough to sit through some mind-numbing info-dumping.

...

Sometimes exposition is unavoidable. I get that. But I can guarantee that this much exposition dumping is, in fact, very avoidable.

First off, we can’t ignore the fact that the information revolves around the DWMA. In other words, it's barely relevant to the episode! Maka and Soul spend the entirety of the episode outside the DWMA. The only time they make any sort of contact with the school is when they call Death briefly. In other words, we could take this entire opening scene out and lose essentially nothing.

Furthermore, we don’t really need to know right away that these kishins are threatening to take over the world and throw it into irreversible chaos. Right now, we should be focusing on getting to know our main characters and establishing a basic understanding of the world. Let me repeat. A basic understanding of the world.

...An understanding that we could glean from just watching Maka and Soul throughout the episode. This world has demon-like creatures, witches, and teenage students carrying deadly weapons (who are somehow human) to kill the first two. That’s enough for now.

But, if the writers are so hell-bent on shoving all of this information down our throats, here’s how they could’ve done it better:

If the writers absolutely — positively — needed us to know what a kishin was: Maka or Soul could’ve rushed into the opening scene while calling out, “There’s the kishin!” and we would’ve known. That’s all it would take. And we would remember that too. Because, if that had been the opening scene had been skipped entirely, we’d be introduced to one new word/idea/tidbit at a time. We wouldn’t have a full understanding of just what a kishin was yet, but that could be shown in later episodes by creating more kishins for the characters to fight. Problem solved.

If the writers absolutely — positively — needed us to know Maka and Soul are students at the DWMA: Maka could greet Death when she calls him by introducing herself with a student ID number. Something like, “Student 666420, Meister Maka, reporting.” Now we know she’s a student at some strange school that trains children to kill kishins and witches. And that meisters are probably students who wield human weapons. (This can be confirmed over time, when Black☆Star and Death the Kid are also referred to as meisters.) Maybe in a later episode, she and Soul walk up the steps to the school, and over the front doors is a sign that says, “Death Weapon Meister Academy.” Problem solved.

I could keep going, but I have another section to cover.

...

What’s even worse is the fact that the exposition doesn’t stop when we finally get to the action. It’s just all in the form of forced, absurdly unnatural dialogue instead.

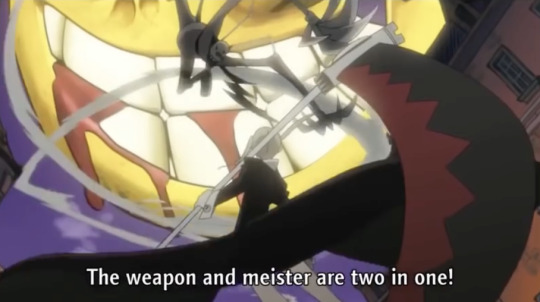

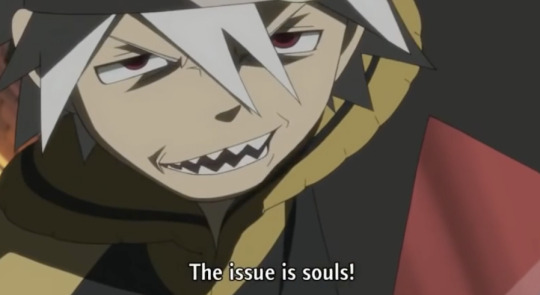

We get lines like Maka saying: “Souls that have left the human path run the risk of transforming into a kishin.” Or, better yet, exposition that doesn’t even give us real information: “The weapon and meister are two in one!”

Or Soul saying: “Just as he isn’t human, I am a weapon. Although, I usually take the form of a human. My form isn’t the issue here. The issue is souls!”

Who would ever say anything like this? Not only do they both know the information that each other are spouting (and therefore it makes absolutely no sense to be relaying this info), but it’s just plain bad. It’s so unnatural it’s actually laughable.

When we get to know the characters, we know Soul would absolutely never say anything like this. He’s not the kind of person to start ranting about himself. Maka might repeat a school motto out loud — because she’s that kind of person — but everything she says in this scene clearly isn’t anything of the sort. If the writers had taken the time to disguise some information as a school motto she deeply believes in, then fine. It would even be telling of her character. But, nope. We get this instead.

Just before I close this off... Really? The ‘villain groaning about needing “more power”’ trope to explain that eating souls gives kishins power? Even the attempts at showing fall utterly flat.

...

It’s finally time to give this episode a score. It’s been a long journey, hasn’t it?

So, tallying up everything I’ve just discussed, I’m going to give Soul Eater’s first episode a C+. It passed because I was intrigued enough to watch episode two, but it failed to adhere to one of the most basic storytelling principles. (Which doesn’t need to be followed religiously, but do need to be consciously followed or avoided.) It gets to be a C+ instead of a C for Maka and Soul’s enjoyable dynamic.

In the end, Dr. Stone’s first episode was much more solid in its execution. We’ll have to see how well the next first episode does!

#soul eater#soul evans#maka albarn#maka and soul#anime analysis#manga analysis#dr stone#dr stone anime

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly: Dr. Stone Episode 1

Well, it looks like I’m starting a series of sorts! I thought it would be fun to analyze the first episodes of a bunch of different anime, so here we are. I’ll be calling it “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” solely because it’s catchy, and I’ll be dividing my analyses into three categories (the Good, Bad, and Ugly). Essentially, everything I believe adds to the episode (thereby making it an intriguing and functional introduction) will fall under the “Good” category, everything that takes away from the episode will fall in “Bad,” and anything I find particularly egregious will find its way into the “Ugly” category.

So, to start this series off, I’ll be analyzing Dr. Stone’s first episode.

...

THE GOOD:

Let’s start with the opening line:

Honestly, I don’t have much to say about it. It’s nothing exceptional, and it’s not an opening line we’ll probably remember after another few episodes. It’s no Tale of Two Cities with its “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Still, it’s gripping enough to get people interested.

However, we shouldn’t ignore that the second line is:

Disregarding the narrator, everything is silent during the opening line. (Everyone is currently stone, after all.) It’s also got a dark, somewhat dreary color scheme. However, immediately after this image, we’re thrown into action. Taiju slams the door open and shouts, “Listen up, Senku!” It’s pretty jarring.

When this is placed just after the first line, it forces us to contrast the two. In other words, we notice the dichotomy of what currently is with what we know will be, and that keeps us interested. Not bad at all.

Next come the character introductions. Overall, just from the way the scene was set up, we learn a lot about our characters through subtleties, which is great. Plenty of showing and nearly no telling.

The first time we see Taiju, it’s with him bursting through the door of a classroom and yelling. We immediately know he’s loud, commits to the decisions he makes, and tends to lose sight of anything else when focused on something (made obvious when he announces his plans to confess to a classroom clearly full of students while only calling out for Senku). And, although he and Senku are clearly close, he can’t exactly predict what Senku will respond with, considering he doesn’t question when Senku supports him at first. Instead, when Senku turns around and says he won’t be cheering at all for Taiju, he exclaims, “Make up your mind!” Taiju is clearly quick to believe whatever he hears— he’s very trusting that whatever someone says is what they mean. We also learn he’s righteous when he pours out the “love potion” Senku makes for him.

The first time we see Senku, it’s with him hunched over an entirely too complex machine, surrounded by other classmates using simple test tubes and beakers. If we learn one thing from this first image, it’s that Senku knows a lot more about science than anyone else in the room. (This is confirmed by his later explanation of what was in the flask he handed to Taiju, and how he made the gasoline inside, but we really didn’t need it.) From his conversation with Taiju, we learn he doesn’t care much about romance, isn’t afraid to call people — even friends — out, and would rather rely on science — logic — alone.

As a side note, just because I couldn’t not mention it, I wanted to point out Senku counting for around 3700 years! Incredibly impressive. Shows how resourceful and determined he can be, but in an almost obsessive way. Very showing (see what I did there?) of his character.

There are plenty more minor things I enjoyed about this episode, but I don’t want this analysis to get too long.

...

THE BAD:

Honestly, there isn’t much to put in this category. My main complaint is some minor telling, with examples such as:

Taiju saying: “I’m going to confess the feelings I’ve had for Yuzuriha for the past five years!” Senku would probably know how long he’s had the crush, or at least have a vague idea. Even if Senku didn’t know, Taiju would have no reason to say this except for the audience’s benefit.

Same thing for Senku saying: “I’ll be cheering you on from right here in this science lab.” It’s very clearly a science lab. Any normal person would simply say “from right here” anyway. This, however, is barely worth mentioning. It’s such a minor issue that it takes nothing away from the audience— in other words, it’s unnecessary and a bit awkward, but it at least doesn’t take away the audience’s ability to discover something crucial about the plot or characters on their own.

There’s also the unfortunate anime trope where characters talk to themselves to reveal their way of thinking or present questions/answers the audience might not have come up with on their own, despite it being unrealistic. (But the writers want the audience to ask themselves these questions, or they want the audience to know a detail that they thought of, so they force the characters to prompt them somehow.) Here’s the biggest example:

(The manga and the anime line up almost word-for-word here, so I’m using the manga to conserve space. I think this is far less irritating than having to paste in three screenshots of the anime so I can show all the subtitles!)

Why would Taiju ever explain this, especially to himself? Anyone could come to that conclusion, so I can’t fault Taiju for thinking it, even if he usually doesn’t seem to put much thought into things. Still, disguising it as praise for a tree doesn’t eliminate the fact that it’s unrealistic and forced. (It almost makes it more forced, actually. Who praises a tree?) The writers clearly wanted us to know that the tree helped her, because the author thought up that little detail and wanted to include it to show how smart they are. (I know this because I, unfortunately, am guilty of this as well. It truly does hurt to delete those kinds of lines, I tell you.) In the end, it’s unrealistic telling through dialogue — which is already strange, because not many people think out loud like this — that the author forced to give us information that we honestly didn’t really need to begin with. Cool if we thought of it ourselves, but nothing lost if we didn’t.

Presented in a different way, say, for example, Senku casually mentioning it in passing around the time they revive Yuzuriha, it would be completely different. (Maybe, as they’re looking at her, he says something along the lines of, “Good thing this tree kept her intact.” Something simple and throwaway, almost.) Still superfluous information to an extent, but it does add something for viewers who might have missed it. It’s the fact that it’s so clearly forced into Taiju’s dialogue that makes it so offensive.

But, because this is so common in anime, I'll let it slide. Still a bit disappointing, though.

...

THE UGLY:

Honestly, I didn’t find anything overtly offensive about this episode. (Unlike The Promised Neverland, which I analyzed in a previous post— that one would’ve had quite a few mentions in the “Ugly” category. So don’t worry! This category won’t always be empty. If you were worried, that is. Probably not.)

Good for Dr. Stone!

...

Overall, Dr. Stone’s first episode has a lot more good than bad. It’s got an intriguing concept, the main protagonist is unique and clearly has his own voice, and the story it sets up is promising. Therefore, I’ll be giving it an A-.

#dr stone#dr stone manga#ishigami senku#senku ishigami#taiju oki#oki taiju#dr stone anime#manga analysis#anime analysis

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Death Note’s Telling Works

It’s been a while since I did an analysis, hasn’t it? But it’s finally that time again, and this time, it’ll be Death Note.

...

Let me start off by saying telling isn’t always bad in a story. If everything was shown in a movie, TV show, book, or manga, we’d get so many extra (and unnecessary) scenes that we’d be forced to read a story that’s got more contrived occurrences than relevant information. We wouldn’t get to enjoy following nearly flawless character arcs or enrapturing plot lines, all because they’d be drowned out by scenes that only exist to show a part of a story’s world-building, a character trait or detail, etc.

For example, telling is often necessary for revealing key details about a character’s life. There’s just no way around it. Let’s say I wanted to show my character has trouble staying asleep at night because they are such a light sleeper that any noise at all in the night will wake them up. I could tell the audience, merely mentioning it when the time was right, or I could instead force a scene in which the character is sleeping and wakes up to the quiet rumble of thunder in the distance, over and over again.

To show this, we would need multiple scenes (at least three to drive the point home) where the character wakes up in the middle of the night from a quiet disturbance. And why would we need so many of those scenes? How could they possibly contribute to the plot in a way that’s strange and exciting? They wouldn’t. Having those scenes would be boring, and the audience would instantly catch on; they’d think, ‘Why are there so many scenes of this guy sleeping and waking up?’ As an author, your audience growing irritated at your contrived situations is probably not something you want.

In other words, if you don’t carefully choose what to show and what to tell, your story’s probably going to fall flat. Which is why telling can be a good thing, and it often is. However, when a story is all telling and no showing, or telling when it really needs to be showing (like when the author wants to demonstrate how their protagonist has changed over time, for example), that’s when things can get a little shaky.

...

The thing is, Death Note utilizes telling far more than it does showing. Honestly, most of Death Note is telling, but it works.

And it works for two main reasons: its telling is both necessary and desired.

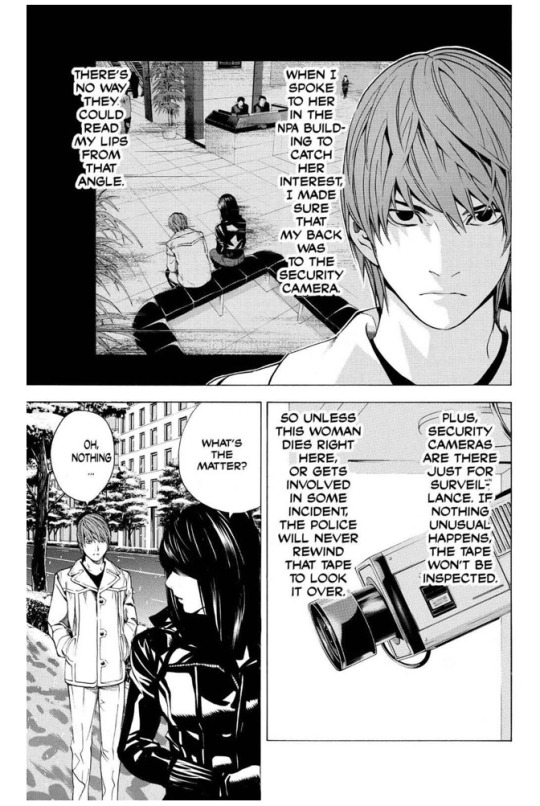

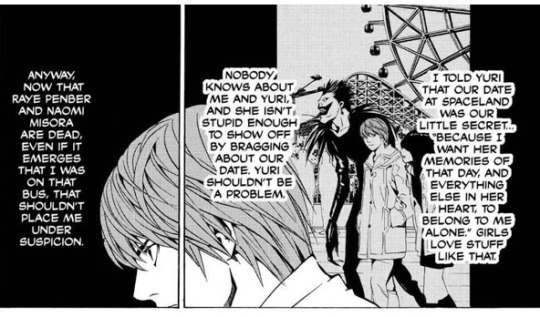

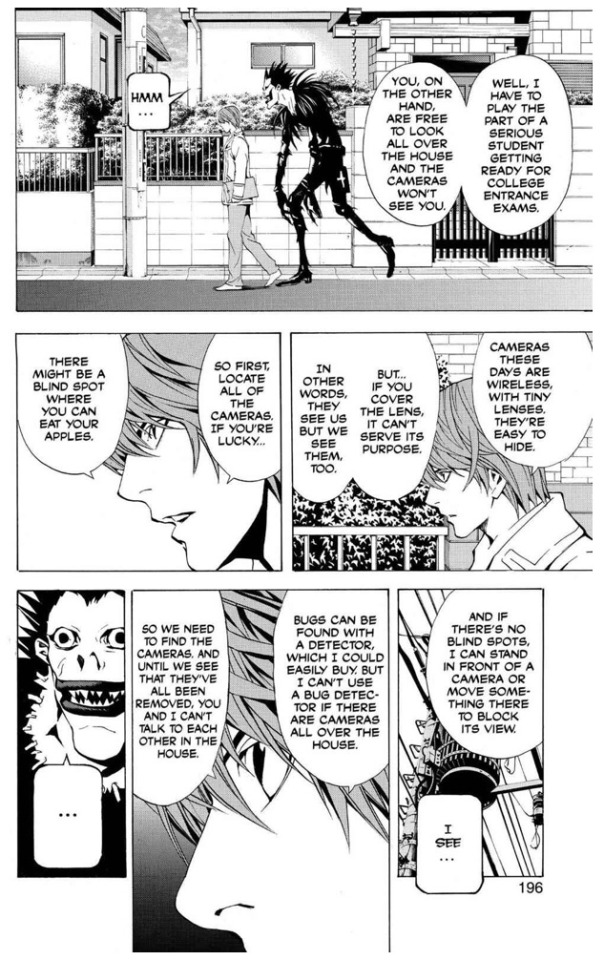

First, let’s just look at a few examples of telling from the manga:

Another:

And another:

These are pretty obviously telling, and these aren't even the half of it.

First of all, let’s discuss why the telling in Death Note is necessary. Well, that one’s pretty obvious; the audience is dumber than Light and L, and Near and Mello (though I think we can all agree Near and Mello are probably not the characters a person thinks of when they think of Death Note). We need every step of Light’s or L’s plan to be told to us, because if they just went ahead with their plans with no explanation (in other words, if the story only showed us what was happening), we would have no idea why. We might be able to piece together why they’re doing what they’re doing after a while, but we’d never know all the nuances. We’d never know all the thought that went into every move they made, and that’s what lets us know Light and L are so smart— their abilities to consider everything from multiple angles at record speed.

(As a side note, I’ll share why Light and L can be so much smarter than the average person. Obviously, the author — Tsugumi Ohba, though this is a pen name — isn’t as smart as they are, because who is? Authors, however, only need one thing to create exceptionally intelligent characters much smarter than they are: time. While geniuses in fiction can come up with foolproof plans in seconds, as seen with Light and L, authors have days, weeks, even months to come up with them. With that much time, just about anyone could think of a plan from every angle.

This, of course, is another reason why Death Note’s telling is necessary. We, as an audience, don’t have that time. Nobody is going to read each chapter of the manga or watch each episode of the anime dozens of times over just to understand what’s going on because it’s being shown rather than told.)

And this brings me to my next point: the telling is desired. We don’t want it to be shown to us because that would be exhausting and boring and, frankly, not worth our time. It wouldn’t be enjoyable to read or watch.

Furthermore, not only do we not want it to be shown to us, but we want it to be told to us. Sounds like the same thing, maybe, but not quite.

See, we want the information to be explained to us because the anime/manga sets us up to want it. We want an explanation because we don’t understand what’s going on, because the anime/manga always shows us the situation before we get Light’s or L’s reactions. We want to know what they think and how they’re going to deal with the situation. We see them reacting to things; we never see them telling us information that we haven't already experienced somehow. For example, the last picture from above. We’re already well aware that L’s team has scattered cameras all around Light’s bedroom, and only after we know this — only after we are prompted to want to know how Light is going to handle this new development — do we get the telling.

(In that scene, the telling is also made better by the fact that Light is explaining something to Ryuk, who is essentially just as clueless as we are. Telling through dialogue, as I’ve mentioned in my The Promised Neverland analysis, only works when the character being fed the information doesn’t already know that information.)

The telling in Death Note works because we want to know how Light or L (or, I suppose, Near or Mello) will handle the situations that were just presented to them.

…

Before I end this, I would like to make it clear that not everything in Death Note is told to us— just the main characters’ plans, really.

However, everything else in the story, for the most part, is shown to us pretty well. For example, we don’t know that Light and L are smart because the manga tells us or because there is a plethora of forced dialogue from other characters about how smart they are. Sure, we might get that, because the other character do recognize that they’re insanely smart, but it’s also shown to us incredibly well.

Their intelligence, funnily enough, is shown to us through the telling that Death Note uses so well. Because, while it’s telling in the sense that the characters are essentially telling the audience what their plans are, it’s showing in the sense that they’re coming up with these plans. Every one of their plans is detailed, with Light and L seemingly considering everything and reasoning what could and couldn’t work.

We don’t need to be told how intelligent they are because their thoughts show us.

…

And that is why Death Note’s telling works: because it’s used when needed and wanted, and showing is used elsewhere.

#death note#death note anime#death note manga#light yagami#death note l#anime analysis#manga analysis#death note light#death note near#death note mello

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why BNHA’s Chapter 285 Bothers Me

SPOILERS: Chapters 284 and 285

...

I apologize for doing another BNHA analysis so soon, but I’ve just got so much to say. It just has so many flaws, I guess. I’m kidding. It’s got at least as many good qualities as it does bad ones. After all, I still like it enough to keep up with the manga and the new season, so it’s clearly got some good storytelling as well. Maybe one day I’ll write something positive about BNHA. But, anyway, let’s get started.

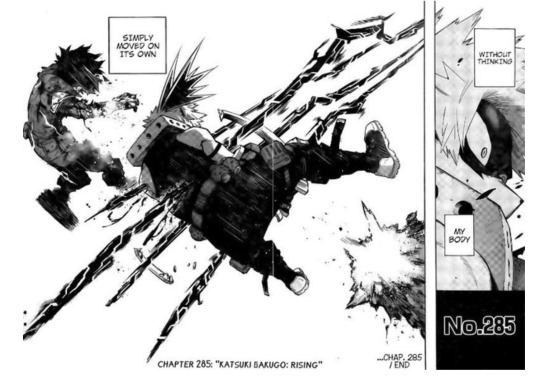

If you don’t remember just what Chapter 285 was, here’s the important part:

Let me start off by saying that I liked the ending of Chapter 285 — I liked the fact that Bakugou sacrificed himself for Deku — just like plenty of BNHA fans did when the chapter was first released. However, it’s Chapter 284 that ruined its full impact for me, and that’s mainly what I’ll be discussing now.

Chapter 284 attempts to accomplish three things, as any good scene should. (The best scenes accomplish multiple things at once, whether it be characterization, world-building, developing a character arc, revealing important information, or furthering the plot.) What this chapter attempts to accomplish isn’t hard to see; Horikoshi is moving the plot forward during the fight scenes with Shigaraki, revealing how Deku got to be so strong with multiple Quirks by showing his training so his growth isn’t so shocking, and revealing more about Bakugou’s thoughts about his and Deku’s relationship.

I don’t have a problem with the first two, but I do have a problem with the last. And here’s why.

First of all, Bakugou’s not really the type to reveal his feelings so blatantly, is he? Yes, he did when he broke down after supposedly “ending” All Might, but other than that, he tends to bottle up his emotions/insecurities and never reveal them to anyone. And we have to take into account the fact that Bakugou’s “ending of All Might” had been weighing on him for a while, and it was building up more and more until it spilled over during his fight with Deku. I don’t think him telling All Might about his past feelings of weakness is the same. He might have been feeling guilty about his bullying for a while, but it never boiled over; this isn’t an explosion like it was with his and Deku’s fight in the third season.

But what really bothers me is the telling rather than showing in the scene. We don’t actually need any of these flashbacks; at least, not the parts where Bakugou and All Might discuss Bakugou and Deku’s relationship. (The parts where he talks about everyone eventually realizing the true nature of Deku’s Quirk and the mystery of the fourth user’s Quirk is perfectly fine and should still be left in there, as those pretty necessary.)

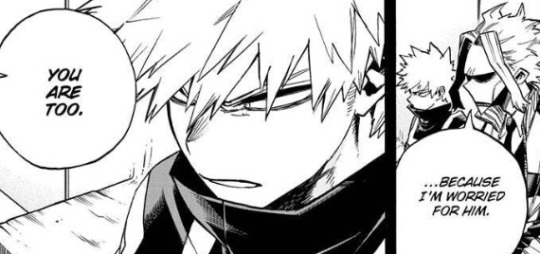

This especially bothers me:

Chapter 284 almost ruins the impact of Bakugou’s sacrifice at the end of the next chapter because the telling that comes beforehand is so unnecessary. After all, does Bakugou not prove that he’s worried about Deku — and therefore cares about him — by sacrificing himself in the next chapter? At the very least, it proves he cares about Deku much more than he tries to let on.

(If I had to take a guess, Horikoshi did indeed want to convey that Bakugou was worried about Deku, but if Bakugou is worried about him, then he clearly cares about Deku’s well-being, right? I think the worrying aspect of this statement is less important than the caring aspect. It is likely a half-attempt from Horikoshi to show that Bakugou cares about Deku by having All Might say Bakugou’s worried about him. After all, Bakugou scowls, thereby confirming All Might’s statement. It’s showing in the sense that Bakugou scowls rather than says yes, but it’s telling everywhere else, so the showing part doesn't exactly mean anything.)

Just because All Might is the one explaining Bakugou’s feelings rather than Bakugou himself doing it doesn’t change the fact that Horikoshi is trying to push this idea onto the audience. He’s trying to make sure we understand that Bakugou cares about Deku despite having no need to, because it’s made obvious in Chapter 285. I mean, if these two panels had been taken out of the manga entirely, would we lose any information at all? Sure, Bakugou’s sacrifice is more to show how deeply Bakugou cares about Deku, but does the rest of Chapter 285, before Bakugou takes a hit for Deku, not show his worry? Not to mention the fact that it’s somewhat unrealistic dialogue, because when could you ever imagine having a natural conversation like this? It’s possible, of course, but unlikely. When grouped with the fact that it’s an obvious ploy to give the audience information, it makes for a pretty terrible dialogue setup.

The audience wants two plus two, not four, right? We don’t need or want unnecessary and repetitive dialogue to know what Bakugou is thinking.

Of course, this might just be me. I won’t pretend like I’m absolutely right about this, because there’s a good chance I’m not. This is just the opinion if someone who knows a little about storytelling techniques.

Still, in my opinion, the redundancy of Bakugou revealing his care for Deku not only takes away from the impact of Bakugou’s sacrifice as a whole, but it also — in a way — goes against the entire point of the scene: to accomplish multiple things at the same time.

Now, a scene should accomplish multiple things at the same time to reduce the amount of scenes that only accomplish one thing at a time. Obviously. But the reason for this is to keep every scene interesting and necessary, because nobody wants to watch or read a scene that serves no purpose. Nobody wants a series of scenes that are likely boring because only something minor is occurring in each (in other words, only one part of the story is being focused on). Anyone would much rather have a scene that keeps them interested in the story, right? This isn’t true for every scene, of course, as there are always exceptions to the rules, but the scenes in Chapter 284 should be perfect for accomplishing multiple things at the same time.

Therefore, Horikoshi repeating himself through Bakugou’s actions in Chapter 285 strips some of the impact of Bakugou’s sacrifice. Because who likes being told something multiple times when they already knew the first time? It’s a waste of time. It’s irritating.

The author doesn’t need to keep telling us the same information. We’re not idiots. We can deduce that Bakugou cares for Deku through his sacrifice, and we would’ve been able to deduce it ourselves without Horikoshi’s interference. If we had been able to come to that conclusion ourselves, in fact, it would have made the scene so much more significant.

And that is why Chapter 285 (and 284) bothers me.

#bnha#bnha manga#mha#mha manga#boku no hero manga#my hero academia#my hero manga#bakugou katsuki#bakugo#midoriya izuku#deku#mha analysis#bnha analysis#manga analysis

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Problem with The Promised Neverland’s First Episode (Part 2 of 2)

Once again, let’s start with The Promised Neverland. This time, let’s move on from the opening scene and get further into the first episode (and chapter).

In both the anime and the manga, we get Ray asking Emma: “How old are you again? Five?”

It’s an embarrassingly obvious tactic to get Emma to reveal her age, along with the fact that she’s the same age as Ray and Norman, as she responds with: “I’m eleven! Just like the two of you!”

This is especially stupid considering the fact that the manga already has Emma narrating certain information about the ‘orphanage.’ Here’s one example in the text framed by boxes rather than speech bubbles:

Now, this is more my opinion, but I think narrating basic information in this way is far superior to the awkward dialogue that’s produced when characters are info-dumping for the audience’s sake. At least, in the case of narration like the kind seen in the manga, there’s nothing disrupting the flow of the story. We’re still told rather than shown, which should be avoided in most cases (like this one), but it’s better than blatantly forcing the exposition and ruining the believability of the story.

If the anime couldn’t have done any better, then at least just give us the narration. It wouldn’t interrupt the storytelling nearly as much, and while it’s still undesirable, I think it’s better than telling through dialogue. With narration, the writer is being upfront about his telling, while telling through dialogue is a poor attempt to hide the fact that he’s telling. And it fails. Because everyone sees through it. Whether you’ve heard “show don’t tell” before or not, know how to use it in storytelling or not, it doesn’t matter. The dialogue’s still just... bad.

And, of course, we can’t forget the testing scene:

If the test is going to tell us their ages anyway, why not just use that? It’d be a creative and effective way of showing the audience that Emma, Ray, and Norman are all eleven. All they’d have to do was have the robotic voice of the test say their names and ages while cutting to that person’s face. And, if the anime absolutely needed us to know that they were the oldest, why not have the test call out the names of the children whose character designs appear to be of a similar age? (We can merely look and see that characters like Conny or Phil aren’t as old as Emma, Norman, or Ray.) Or, at the very least, just add the narration that was a part of the manga’s first chapter? Even that would be better than what we get.

Overall, Ray’s question — or rather Emma’s response, as the question itself isn’t unnatural — is just yet another way that TPN fails to follow one of the most basic writing rules in existence. Still, this is only a little grievance I wanted to bring up, solely because it felt wrong to leave it out. Now, however, let’s get into the main point of Part 2.

…

Back to the test scene in the anime. (In the manga, what I’m about to discuss occurs after they play their game of tag, but it’s nearly word-for-word, so this argument holds true for both.)

After they take their test, and Isabella announces that Emma, Ray, and Norman had gotten perfect scores, the others express their amazement. This is all well and good — and the anime should’ve left it at that. It would demonstrate that the three were smarter than the rest, especially when highlighted by the fact that the other kids were impressed to hear Thoma say he might’ve gotten half right. (In the manga, a few of the test questions are shown, and some of them are just evil. Eleven-year-olds solving for a derived equation in 10 seconds? Getting full marks is insanely impressive when we’ve seen some of the questions, so why not show it in the anime?)

Yes, what I just mentioned would only demonstrate that they’re smart. But that’s all that this scene needs to demonstrate. It’s short enough that it doesn’t need to give us any more information, as we’ve still got plenty of time in the episode to learn other vital information necessary for understanding the plot.

It’s when this scene continues, however, that we start to see a real problem.

After they hear their scores, the kids vocalize, solely for the sake of the audience, the basic character descriptions of Emma, Ray, and Norman. They say: “Those three are different, huh? Norman is a genius who has the best brains. And Ray, an intellect who can compete against Norman’s genius. Emma has amazing athletic skills, and her learning ability allows her to stay close to the other two.”

It’s quite the way to take some of the fun out of learning about the characters, isn’t it?

It’s just… why does the anime (and manga) find it necessary to include this? Not only will we probably not remember half of it — which is for the best — but it lessens the impact of us learning about the characters ourselves.

If the characters truly are these things, we’ll see that through their actions and dialogue (which would show their deductive reasoning skills). After all, they are the ones who come up with the escape plan despite all the trials thrown at them. When we see this, we can deduce for ourselves that these kids are not only book-smart (which we learn from their perfect scores) but street-smart, able to solve issues that most eleven-year-olds would never be capable of. Through this alone, we learn most of the information that was told to us during the test scene. And Emma’s athletic skills are demonstrated reasonably well during their game of tag. (If that scene were edited slightly, it would be obvious that Emma is superior to the others in terms of athletic ability. This is a fault in the author’s scene construction.)

And we can’t forget the fact that their younger peers are saying this about them. Even if they knew these things subconsciously, what child would say something like this? They’re all smart, as they’re all high-grade meat, but they’re still kids. Kids don’t tend to break out into character analyses about their friends, especially not without any prompting.

So what’s the point of this telling?

Telling doesn’t serve any purpose, as we won’t believe it until we see it. If Emma, Ray, and Norman failed in their escape attempt because they weren’t smart enough, we wouldn’t believe the telling. But if their smarts are proven through their actions, than what point does the telling serve? Nothing. The only thing it accomplishes is forcing more unnatural dialogue that reminds the audience that they’re watching a show, not living in a story. And that sucks.

(Telling is often a sign of laziness or ineptitude, whether that ineptitude is truly there or the author simply believes they are inept at crafting a good scene. After all, it wouldn’t be needed if the author knew for certain that they had created situations to move the plot along while simultaneously demonstrating the characteristics of his three main characters. This telling could be a sign that TPN’s writer, Kaiu Shirai, didn’t trust himself to accurately portray his characters’ traits. Or maybe he just believed the audience was too unintelligent to understand his characters as he wanted them to be perceived.)

Let’s compare this scene to Attack on Titan’s first episode, where we learn quite a bit about Eren’s personality as Isayama introduces us to the story. All without telling anything about Eren, too.

Let’s use this scene:

Isayama wrote this scene for a reason, and that reason was to reveal Eren’s core beliefs, and he does this through showing. (We’ll have to ignore the telling about Eren’s father and his success as a doctor. Unfortunately, not even Isayama avoided convenient telling completely. But at least the information wasn’t particularly relevant to the story, so it didn’t ruin much other than the flow of the story.)

You see, when Hannes asks why he would ever need to be prepared for a fight, Eren responds with: “If they breached the walls and entered the city!” When Hannes brushes Eren off, Eren yells, telling him to stop calling himself a part of the Garrison and become a member of the Wall Repair Corps. And when Hannes reasons that they’re slacking off is a good thing because it means everyone is safe, Eren says: “Even if we can never leave these walls for our entire lives, as long as we eat and sleep, we’ll survive… but that just makes us like cattle!”

Not only do his words give us a little more information about what threat humanity is up against, but they also reveal so much about Eren’s personality, goals, and beliefs. We learn that he hates being caged in the walls, hates people who are satisfied with living in a cage, wants to go outside, and values living rather than just surviving. All through dialogue that flows and doesn’t slap the watcher in the face with its lack of tact.

Now, this:

A little later, we learn that Eren’s willing to fight for his freedom, as he admits to wanting to join the Survey Corps. And he’s extremely dedicated, we learn, not because the show narrates to us that he’s dedicated (like TPN might do) but because he sees the horrors of the Survey Corps when they return from their mission and yet still wants to join them. After all, when Mikasa tells his parents that he wants to join their ranks, all Eren says is: “I told you not to tell them!” Throughout the rest of the episode, he makes absolutely no indication that he no longer wants to join them. In fact, he acts like he hasn’t been swayed in the slightest.

Not a single thing I’ve just mentioned can be considered telling. No, it’s all showing through dialogue that isn’t forced in any way, shape, or form, and that’s what makes it work. From Eren’s anger to his dialogue to his attitude towards the world and people around him, we learn everything we need to know about our main character without Isayama needing to tell us. Because Isayama does tell us. He just does it through showing, unlike TPN.

And that is the problem with the first episode of The Promised Neverland— while the episode could have been constructed to show everything that the audience needs to know, it wasn’t, and therefore it must rely on unrealistic, forced dialogue that ejects the audience out of the story it’s trying to submerse us in.

#the promised neverland#tpn#tpn emma#tpn ray#tpn norman#attack on titan#shingeki no kyojin#eren yeager#anime analysis#manga analysis#tpn manga

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Problem with The Promised Neverland’s First Episode (Part 1 of 2)

The problem with The Promised Neverland’s first episode (and to a certain degree, the first chapter of the manga as well) is its telling. Everything important for the audience to know is told through dialogue that is so unnatural that it unceremoniously tosses the watcher out of the story.

Therefore, today, I’ll be pointing out the scenes that I believe are the worst examples of this. I’ll even be throwing in the first episodes of Jujutsu Kaisen and Attack on Titan to compare with TPN to highlight its downfalls.

So, first, let’s start with the opening scene of TPN.

Right off the bat, we get: “We’ve never been outside” as one of the first lines in the show. This is a fine example of one kind of telling: when characters tell each other information that they are all already aware of. Why would Emma say this? It’s purely for the audience and not for Norman or Ray, but they’re not trying to talk to the audience. This isn’t a comedy anime that purposely breaks the fourth wall for laughs.

Telling rather than showing, in this case, creates unrealistic dialogue that makes the story seem less real— it disconnects us from the story and doesn’t let us live in the world with the characters. We can’t get attached to them because we don’t get to learn anything about them ourselves. The show merely tells us what we need to know rather than letting us figure it out on our own; the writers are treating us like idiots, really. (Of course, this is usually the case with telling in dialogue. I only meant ‘in this case’ in the sense that telling through dialogue isn’t the sole way to tell rather than show.)

Right after this comes: “That’s because we’ve been here every since we were born.” Again, Norman and Ray know this. Obviously. Why would anyone feel the need to say this except to inform the audience?

Then we move on to information that is especially easy to convey through showing rather than telling. For example: “Mom always tells us, doesn’t she? ‘Don’t go near the gate or fence in the back of the forest because it’s dangerous.’” Not only is this even worse than the previous quotes because she feels the need to add unnecessary details (“in the back of the forest”), but the information could be so easily conveyed through their actions and dialogue.

What the anime wants to get across is the fact that they’re not allowed outside because it’s supposedly dangerous. That shouldn’t be too difficult to get across to the audience through showing. In fact, they do most of it just a few lines later. When Emma asks what Ray and Norman would like to do if they ever got to go outside, the audience instantly knows that they’ve never been outside before. (Furthermore, their answers could be such a good way of revealing something about their personalities. Which, unfortunately, their personalities are revealed horribly later. I’ll discuss this in Part 2.)

And what if, after they all said what they would like to do if they ever got to go outside, one of them said they should head back? If their voice was shaking, and their facial expression was clearly strained, the audience would know that they weren’t supposed to be there. All they would have to say then was something about how they should go before their Mom finds them, and the showing would be complete. The audience would be able to conclude all the same things that the telling did— they’d just be able to do it on their own. And we want the audience to do it on their own. We want, as the audience, to be in the story with the characters, to figure out their struggles ourselves because it forces us to be a part of the story.

To compare, let’s use the opening scene of JJK.

There’s no telling in this scene at all, and therefore, it leaves the audience guessing, wondering what will happen next. It forces the audience to gather the little information the scene does give, like the fact that there’s a Fushiguro we are yet to meet (courtesy of Itadori saying “Fushiguro-senpai!”) and that there’s a school called Jujutsu Tech, where Gojo is in charge of its first-years (courtesy of Gojo introducing himself).

One of the only lines that could possibly be considered telling is Gojo introducing himself, saying: “Gojo Satoru. I’m in charge of the first-years at Jujutsu Tech.” The difference between this and TPN’s atrocious dialogue is the simple fact that it isn’t actually telling. Gojo is introducing himself to Itadori more than the audience— after all, Itadori’s never met him. This works because Itadori has no idea who Gojo is, unlike Emma, Ray, and Norman, who all know the information that Emma is telling them. Gojo is talking to Itadori, and Emma is talking to the audience.

The other line that could be seen as telling is the last line of the scene: “It’s been decided that you’ll be secretly executed.” However, once again, this information is for Itadori and not the audience. Just by Gojo’s wording, and coupling that with Itadori’s shocked reaction and clear lack of understanding on why he’s with Gojo in the first place, make it obvious that Itadori isn’t privy to much more information than the audience is.

Jujutsu Kaisen does an excellent job of creating a scene that instantly eliminates any chance of telling through dialogue in a way that The Promised Neverland does not. (This is specifically referring to telling information through dialogue that everybody in the room already knows.) And JJK does this by simply giving us a character that knows about the same as we, the audience, do. In other words, nothing.

#the promised neverland#tpn#tpn anime#tpn manga#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#gojou satoru#gojo satoru#itadori yuuji#tpn emma#tpn ray#tpn norman#anime analysis#tpn analysis#jjk analysis

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I Believe Deku Fails as a Character (Part 3 of 3)

SPOILERS (for My Hero Academia Chapter 306 and 307, Attack On Titan manga spoilers occurring after Season 4 Part 1)

...

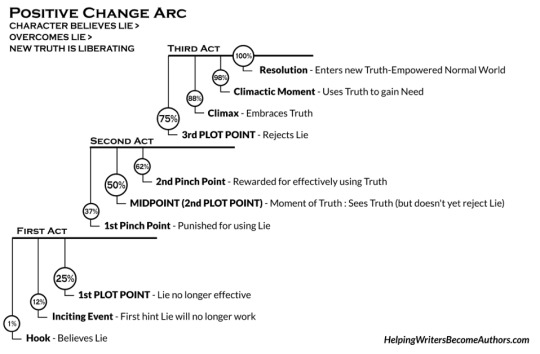

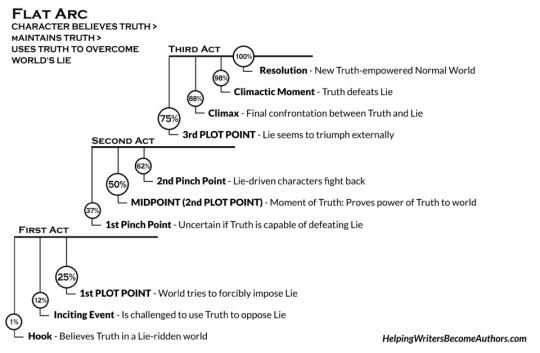

Allow me to introduce you to two kinds of character arcs in writing: the positive change arc and the flat arc.

(There are five major kinds of character arcs in total, but I’m going to focus on the two above for right now. The other three are as follows: the fall arc, the disillusionment arc, and the corruption arc. In general, the positive change arc is the most common, so I’ll be sticking to that for the majority of this part. However, I will briefly cover the other three in light of Chapter 306 and 307 and where I believe the manga might be headed.)

First, the positive change arc:

To make this easier (in other words, less time-consuming), let’s just focus on the three phrases under the title.

Character believes lie, overcomes lie, and new truth is liberating.

...

Second, the flat arc:

Again, let’s stick to the three phrases under the title.

Character believes truth, maintains truth, and uses truth to overcome the world’s lie.

...

All right, now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s begin.

Deku follows a flat arc, not a positive change arc, at least up until Chapter 305 (but I will discuss that later). While this isn’t necessarily a bad thing as a concept, because flat arcs can still be quite interesting, his character arc is executed in such a way that makes it boring. To be frank.

The reason why I first introduced you to the positive change arc, if you are not already familiar with it, is because it was most likely what you expected when you first began the watching the anime or reading the manga. It was what I expected, at least. Because it is the most common out of the five in any story you either watch or read, whether it be an anime, a movie, a TV show, a manga, or a novel.

There’s nothing absolutely wrong with subverting expectations as long as it’s done well. That is why so many people love Eren Jaeger after the recent chapters of the manga or after the final season of the anime. Eren absolutely does not follow a positive change or a flat arc. No, you’ll see people claiming that Eren is one of the best anime protagonists in history because he doesn’t follow the popular positive change arc. His development is tragic, but it’s so real, and it’s so compelling to see him go from Point A to Point B.

I, of course, expected Eren to eventually follow a positive change arc, and the fact that he didn’t was great. Isayama handled his character arc so well that the subversion of that expectation only made Eren, as a character, all the more appealing.

Just... the anger, then the resignation, then the resigned determination that’s present even in his character design:

Let me first explain how Deku is going through a flat arc.

Deku’s views of the world of heroes are never challenged by anyone else in the anime or the manga. In fact, they’re only ever confirmed, especially by Stain when he saves Deku from the Nomu because he deems Deku worthy of becoming a hero. We’re only reminded of this later, during the League’s attack on the training camp, when Spinner saves Deku from Magne because Stain acknowledged him.

(And maybe this is okay, because his view is that heroes should want to save everyone with a smile. Heroes should be like All Might, who reassured everyone just by showing up, all because they knew he was powerful enough to save them. And that he would save them without fail. His view of the world, of what a hero should be, is right in most people’s eyes.)

In other words, Deku does not believe a Lie that will eventually become a Truth. No sirree. Instead, he believes a Truth and has maintained it, and we expect he will eventually go on to change the world with it. (Unless that changes, but let’s assume this for now. Besides, even if he does have a character arc now with Chapter 306 and beyond, that doesn’t negate the fact that he hasn’t grown in the first 300 or so chapters.)

So, as of the anime right now, Deku’s following a flat arc. Which would be fine, if his arc was still compelling. You see, flat arcs need something to make them compelling if the character themself isn’t going to change.

For most flat arcs, you’ll see the main character, rather than growing or changing themself, change the world around them. They will uphold their inner truth in a world that doesn’t agree with them, and, eventually, the world will see that the character was right all along. But the world’s opposition at first is what drives the plot, and it is what makes the main character’s journey interesting.

Because it’s conflict. Stories need conflict.

So, automatically, Deku’s flat arc fails this requirement. It’s been proven over and over again that Deku’s outlook is right. Out of all the villains in MHA, Stain is the one whose philosophy we can agree with. Even the characters in the anime/manga agree with him! Horikoshi goes so far as to include Class 1-A commenting about how Stain’s philosophy is actually correct in some ways, and he mentions that Stain has merchandise created for him (in the MHA world) because his beliefs are appealing to the masses.

Essentially, what a flat arc character needs is a Doubt. In other words, the character needs something to make them question whether their Truth is right or not. Maybe this takes the form of doubt in a normal sense, with the character wondering whether or not they chose the correct Truth. Maybe this takes the form of doubt in the sense that they don’t know if they have the strength to carry out their conviction.

There are many ways to execute a Doubt in a flat arc story, and yet Deku doesn’t seem to have one.

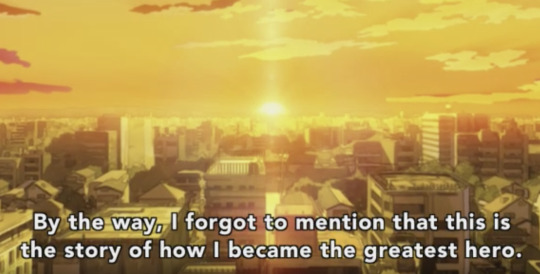

I mean, hell, there isn’t even a doubt (ha-ha, see what I did there?) that Deku will become a great hero. From Day One, we’ve already known he’s going to become not only a great hero but the greatest hero:

So we know Deku succeeds in his goal of becoming a hero. This immediately strips away the fear that Deku won’t succeed in his current goal of becoming the next All Might. And while we can’t say for certain, I don’t think it’s farfetched to believe that the ‘greatest hero’ version of Deku believes the same thing as Deku in the second episode, where this line is from. With the word choice of “by the way” coupled with the fact that this line appears when it does, it seems to suggest that Deku’s going to become a hero with the same convictions as he has now. It gives off a childlike tone that parallels what Deku believes in now, as a child, which is the Truth I described up above.