Text

The Top Movies of 2023

Every year I feel like I write the same spiel about the truly concerning number of movies that I compulsively watched, and then make false promises about being more intentional about my film-watching and my blog-writing. But fear not, there's no overwrought analysis of my film watching this year, just an assurance that, for once, I have stayed true to my word and reduced my annual total by a sizable chunk. It was, however, still a lot.

Truth be told, I've been trying to write this wrap-up for weeks now, but I found myself enveloped in the gloom that sets in during the first few weeks of any year, except this time the fog seems denser than ever. This is not a reflection on the state of movies right now though. While everything else has either gone to shit or currently in the process, movies have not been this good in 4 years. We're lucky to have some incredible filmmakers return to peak form (Marty S) and others showcase their talent for the first time (Celine Song).

But this was also the year where domestically (The Kerala Story) and internationally (The Sound of Freedom), we saw an uptick in the mainstream success of conservative films built on the premise that the right-wing needs to go save good innocent people who are being taken advantage of by the savages. And shamelessly, people bought into this mediocre (at best) pandering, simply because it reinforces their narrow world view. As someone who constantly whines about the death of big dumb cinema, if this is the future of spectacle film, I might just be out on it.

Apologies to American Fiction, Poor Things, Ferrari, You Hurt My Feelings, The Boy and the Heron, The Holdovers and All of Us Strangers (all of which I have not yet seen), to Showing Up, King of Kotha, Marlowe, Your Lucky Day, The Boys in the Boat and The Last Voyage of the Demeter (all of which I saw and desperately wanted to love) and to myself for deciding to watch Ghosted, Heart of Stone, White Men Can't Jump and Salaar against my better judgement.

Here are my top 27 movies of 2023:

27. Bottoms

26. Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

25. Neelavelicham

24. A Man Called Otto

23. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

22. Barbie

21. LOLA

20. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

19. Air

18. John Wick: Chapter 4

17. Sanctuary

16. Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning

15. Oppenheimer

14. Anatomy of a Fall

13. Rye Lane

12. Biosphere

11. Flora & Son

10. Evil Dead Rise

2023 was a spectacularly disappointing year for horror. The biggest hit of the year was Talk to Me, a movie that I liked but is so overwhelmingly despondent that it drowned out the scary aspects of it. Evil Dead Rise on the other hand harkens back to the classic horror franchise format, taking a tried and tested premise (cocky young person accidentally summons the dead) and putting it in an unpredictable new setting (a high rise building). It strikes the perfect balance between nightmarish, gruesome and goofy that makes you yelp and giggle all at once.

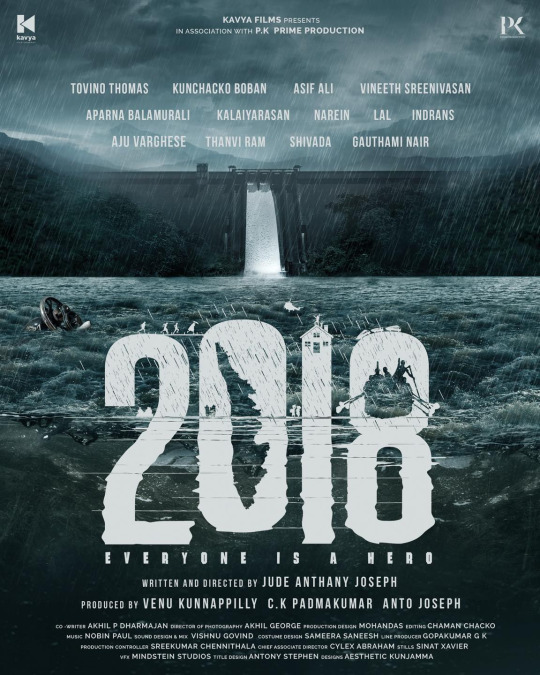

9. 2018

This is the type of peak Bruckheimer/Simpson disaster flick that just went away 10 years ago, only scaled down to fit the Malayalam film industry. Does that take away at all from the melodrama or spectacle? Not even a bit. It's incredibly well made and well-balanced emotionally, and the ingenuity of the production design ensures that it will continue to hold-up visually in years to come.

8. Maestro

If we put aside Bradley Cooper's obvious thirst for acknowledgement by the Academy and just look at Maestro on its own, you might get a glimpse of a movie that bends the classic Oscar bait biopic template to its own absurd ends. It's not a "cradle to grave" story nor does it limit its scope to a small, well-defined period in Leonard Bernstein's life. Instead it's much more impressionistic and formally inventive, giving the viewer a feel for who the man was in all aspects of his life. It's in direct conversation with the template of the "great man" biopic, starting down the path of each trope only to veer delightfully off course, whether that's by sidestepping into a dance sequence or literally running away just when a scene starts to feel too cliché.

7. Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret.

As a person who cannot stand kid angst, I went into this movie expecting to like it with some reservations, which is very much how I felt about Kelly Fremon Craig's previous movie, The Edge of Seventeen. But Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret. rises above the cringey uncomfortable moments we've come to expect from a coming of age story. It's wholesome and heartfelt, but with enough of a bite to it to overcome the usual allegations of saccharinity that are hurtled at a movie of this sort. It's finally perfect, with some great kid performances, and even greater showings from the adults. In particular, Rachel McAdams takes what could have been a put-upon harried mom role and adds just enough humour and sparkle to make her character feel fully fleshed out, without making the whole movie about her.

6. How to Blow Up a Pipeline

Every year there's a movie that feels like it's ripped from the inside of my skull. How to Blow Up a Pipeline is exactly that. It's not for everyone (people have been known to zone out in the first 15 minutes) because it's an intense, violent story about trying to spark a revolution. Here's the thing about this movie, it believes in the power of direct action against corporations. And so do I.

5. Afire

The latest film from Christian Petzold is on this list precisely for that reason. From the first time I watched Phoenix, I realised this was a director I'd want to be following closely. His movies are often strange and unpredictable, unfaltering in their portrayal of the weakest aspects of human nature while still somehow tying together and extremely compelling plot. Afire is to me the strangest of the lot, which is really saying something because his last movie was about a mermaid.

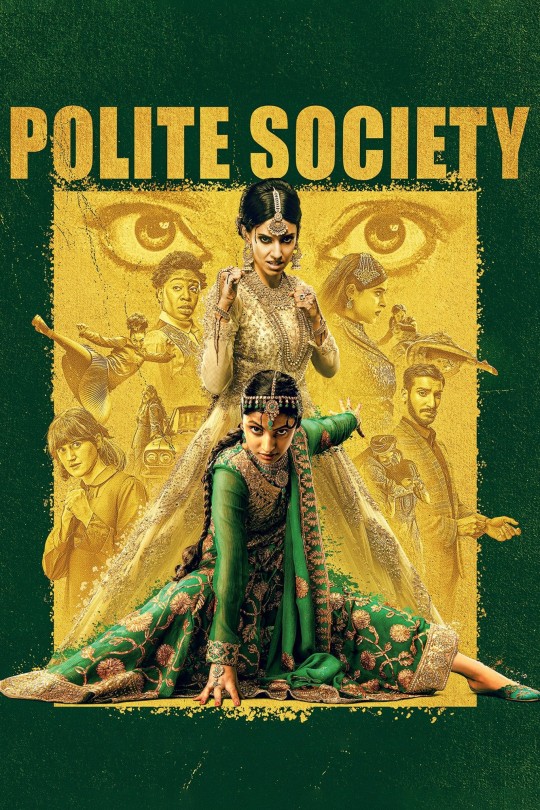

4. Polite Society

Nida Manzoor is not yet a household name, but I can't imagine that'll be the case for much longer. I was first introduced to her work in the excellent British punk rock comedy show We Are Lady Parts (which is about a group of British Muslim girls who start a punk band), and Manzoor brings that culture clash chaos into Polite Society. It manages to take a love of old-school film stunts, an iconic Bollywood number and quick-fire dialogue and roll all that up into an irresistibly charming story about sisterhood.

3. Kaathal: The Core

You might be able to argue that 2018 is on this list because of pure sentimentality and my personal attachment to Kerala. It's my list after all, my predispositions will be on display. Kaathal is not on here for those reasons. It's here because it's a heartfelt, earnest depiction of what being gay might mean in rural Kerala, and it somehow walk the tightrope between idealism and realism in a way that gives the audience hope that the unconditional acceptance of queer identities could be just around the corner. There's almost a straight line from Vijay Sethupathi’s role in Super Deluxe to this, but it's still a real pleasant surprise to see someone of Mammootty’s stature in an Indian film industry use that influence to make such a nuanced, emotional and ultimately hopeful film centred on a queer person.

2. Past Lives

I could not for a long while explain why this movie hit home for me, but I think I'll give it a go. Past Lives depicts so clearly the struggle I've often felt to not let your present self erase your childhood memories and cultural identity, even if they're conflicting (as they often are). There is a familiar underlying fear in this movie that a happy memory you might have from a past life (if you will) would crumble under any amount of scrutiny, like an ancient paper suddenly exposed to sunlight. I've been told that I'm annoyingly sentimental about goodbyes (more so than usual, if you can imagine that) . After all, it's 2024 and very easy to stay in touch. But I know how easy it is to lose track of people that you loved deeply, like they were family even, simply because the physical and cultural distance was too wide to bridge through just social media. Past Lives made me think of them, and of all the different roads my life might have gone down and how, despite all that, I'd still choose to be where I am today. Schmaltzy, I know, but this is the movie to get in your feelings for.

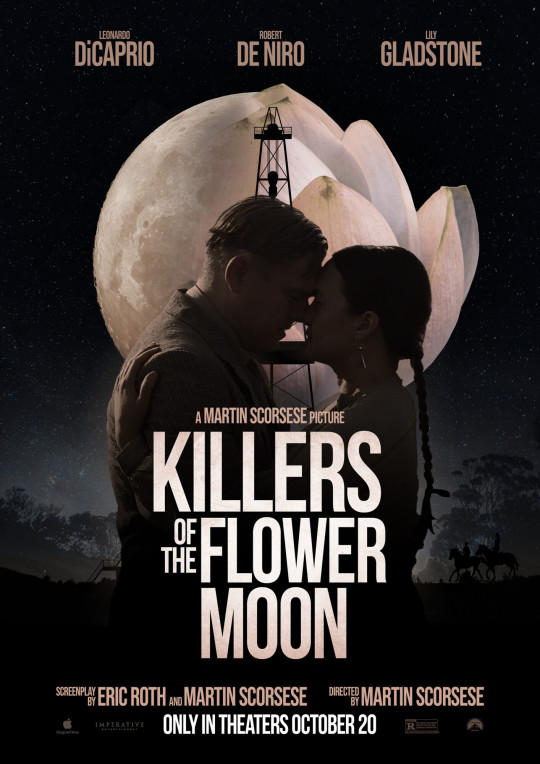

1. Killers of the Flower Moon

Every year, my number one movie is about storytelling, and this year is no different. It's not a purposeful trend though; I just respond very strongly to movies that play around with the idea that film is the most objective medium for storytelling. Killers of the Flower Moon is a premier example of that sort of subversion, although that doesn't necessarily come through for most of the running time of the movie. Superbly paced and tonally immaculate, Scorsese delivers one of his best films in the seventh decade of his career, and it hinges almost entirely on a perfectly calibrated performance from Lily Gladstone. But this film wouldn't work nearly as well if not for the incredibly nuanced and insightful ending that ends up being a testament to the art of adapting true stories.

***

There were some other bits and bobs from this year that I wanted to share.

As far as TV goes, Lockwood & Co. is perhaps the best new show of the year, despite it getting cancelled after the first season. It's spooky fun designed to satisfy horror mavens without turning away those who are not fond of your usual scares.

Slow Horses continues to be just as clever and callous as ever - a breath of fresh air in a somewhat stale spy-fic landscape.

And if you're looking for a traditional sitcom, there was none better this year than Primo.

As I write this, Killer Mike's Michael just won a whole bunch of Grammys. I've been a fan of him since I first stumbled onto the first Run the Jewels album, and this was the first time in recent memory that the Grammys made the cool choice in the rap categories. The only cooler pick would have been Mick Jenkins' new album, The Promise.

Other albums that I loved from this year include Cracker Island from Gorillaz and Paranoia, Angels, True Love by Christine and the Queens, both excellent entries into the pop-rock category for the year.

***

Also I'm on a podcast now. It's called Stir Fry and it's more regular than this (low bar). Stay tuned to that feed and soon you'll hear me lose my mind about the Billie Eilish song potentially winning and other unhinged Oscar reactions. Stay tuned here, and (fingers crossed) there might be another article soon - lots to write about this year.

0 notes

Text

Gameday at the Movies

I once met someone who had no interest in sports at all, and yet one of his favourite movies was Chak De India. It took me years to really wrap my head around it. How can you love a sports movie that much, but have no interest in the real life equivalent? To me, sports fandom is so intrinsic to loving sports movies that I had a tough time separating the two. And, to be honest, being a sports fan, if you look past the numbers and win/loss column, is all about the story and the drama: friendships, rivalries, heroics, tragedies, legacies, all of it. What you get in a movie, you get in real life sports, but messier.

And athletics is one of the few parts of our culture that is still holding on to some of its magic. Every time Dame Lillard throws up a gamewinner from the logo, an arena goes quiet, coiled to explode. When Andy Murray went on his miracle run at the 2023 Australian Open, everyone and their mothers had their fingers crossed, hoping against hope. When Argentina won the World Cup, I watched my relatives (who are, to be clear, not Argentinian) weep with joy.

But getting into sports, getting so emotionally connected to a game in the first place, that’s tough, especially if you didn’t grow up watching it on TV or playing. There are a million rules for you to learn, while fans and analysts alike are constantly volleying stats at you like they’re decrees from god: usage rates, efficiency, value over replacement and every other forced metric is seemingly unimpeachable. Don’t get me wrong, I love a good stat, but for me as a fan, stats do not give or take away meaning or value from performances or narratives. Is Diana Taurasi the most efficient player in the WNBA? No, but that doesn’t matter to me because she represents something more intangible and everlasting: greatness.

Hell, even the basic starting point of picking a team or player to support is tough if you don’t have a home town team or athlete to turn to. You have to be careful – you might, for example, end up on the Mayweather bandwagon for a couple years before you realize that Pretty Boy Floyd might be the most successful poseur in the history of boxing. And once you do end up on a side, you might discover that the fanbase of which you’re now a part has a belligerent online faction that irritates you at every turn (a very merry fuck you to all Laker fan forums).

There is that great Nora Ephron line, “You don’t want to be in love. You want to be in love in a movie.” And to some extent, if you play or love sports growing up, you don’t just want to be a pro athlete. You want to be in the movie. I never thought I could be Michael Jordan, but I definitely wished I could be Calvin in Like Mike, with the miracle shoes from the basketball gods. Movies take the everyday magic of sports and package it into 2 easily digestible hours, so how can you not love it?

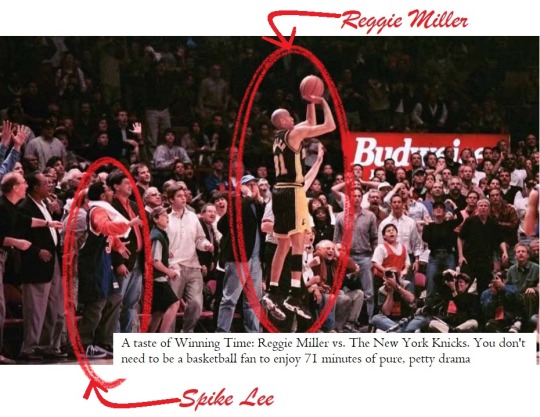

Plenty of ways, it turns out. You’ll see plenty of jock writers lament the death of their precious genre and that, I think, is just panic. The sports documentary has had a major resurgence in recent years, sparked, no doubt, by the popularity of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series (Winning Time: Reggie Miller vs. the Knicks is among my favourite films all time) and The Last Dance. But when it comes to dramatized features, in the last 20 years, there have been maybe five great sports films (we’ll get to that in a minute) and a diminishing number of attempts (with one subgenre being the exception – we’ll get to that too).

But I think there are a couple obvious reasons for that. First and foremost, they cost a little too much, and it’s not like people are rushing to theatres to watch a movie about tennis or football or the other football. Plus, like with most genres that are so laden with stereotypes and set narrative beats, audiences tend to have a “seen one, seen them all” mentality towards sports flicks.

And then there is the sense that everything has been gamified, from movies to governance to your daily news of choice. Politics seems to be more "my team, your team” than ever before, and reporting on TV has devolved mostly to talking heads with the loosest grasp on the facts giving hot takes – which is entertaining and only mildly annoying when Stephen A. Smith does it about the NBA, and horrifyingly glib when NDTV does it about life/death situations.

But one of the more insidious ways that sports has permeated a non-sports part of my life is at work. I feel like, for our parents’ generation, the pitch was “your office is like a family”. You watch movies and TV from the mid-to-late 90s when they were entering the workforce, and they’re constantly pitching you this idea that work is a family, one for all and all for one. It’s gross and saccharine, and although it’s blatantly dishonest, the evolution since then has not been much better.

The workplace now is nominally modeled after sports. I think it comes from the transposability of sports-related wisdom to any sort of group effort. “Take one for the team” or “don’t drop the ball” or “that’s a slam dunk” (which, don’t believe the hype, very hard to do) are all things I hear regularly. To be microscopically one-to-one about it, there is the idea that you all come together to work and execute a plan as a fully enmeshed unit that will beat all the other teams competing against you to reach the same goal. At a glance, it might track, but if you have any experience being on a sports team or even spend an extra second thinking about the implications, it’s absolute horseshit.

Within a team, there isn’t a strict sense of hierarchy and the style of play is crafted around the strengths of the players. That’s not translated into work culture at all, especially within corporations. A worker, regardless of their skills and/or talent, is slotted into place depending on what the company needs. In all honesty, my workplace, like most corporate workplaces that I’m familiar with, is modelled after a factory line. You get your corner of the product to work on, do your job, pass it on to the next person in the line. And if someone fucks up in that line, the shit always flows down the hierarchy. If you don’t do your work or don’t do it on time, that’s a loss. But, especially on the middle and lower rungs of a corporation, there is no work equivalent to winning. You just do what is required of you and maintain the status quo. And that idea of beating the competition in the marketplace at all costs? Studies in the field have posited that maybe, just maybe, it’s not a sustainable model for businesses. Which makes sense. Sports teams, even the greatest dynasties of all time, are build for immediate success. Few of them are successful for more than two years, so why would that be any different for businesses built on the same ethos?

Yet, despite all this, despite the sickening conflation of work and play, despite the declining interest of filmmakers and studios, once in a while, we still get sports movies that hit home. So, beyond making sure that the technical and story aspects of the movies are solid, what makes those select few successful?

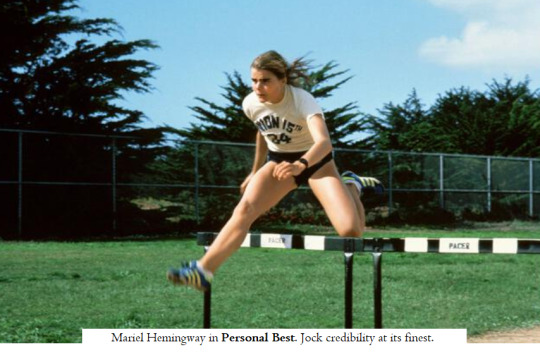

You have to cast right. This is the biggest issue with sports movies. If the actor can’t convincingly look like they play the sport at a high level, the movie is pretty much dead in a ditch to me. Even outside the arena, athletes carry themselves with the confidence that they are in control of every minute motion made by any part of their body. This confidence is often referred to as swagger, but let’s call it jock credibility.

For example, in High School Musical, I totally believe Corbin Bleu’s Chad is a two-sport athlete, but it’s way tougher buying that a local community college would be interested in Troy Bolton, much less UC Berkeley. Zac Efron can spin the ball on his finger but that does not buoy his ghastly dribbling skills. One of the big flaws of High School Musical is choosing basketball as his sport. Basketball requires so much basic technical skill to qualify for an elite level that it requires someone who is actually excellent at the sport (Sanaa Lathan in Love and Basketball) or a generally athletic actor and some extremely creative editing (Wesley Snipes in White Men Can’t Jump).

This is why picking the right sport is crucial. Almost every great sports movie has a significant chunk of gameplay, so it’s always best if the sport allows the actors to easily fake competence. This is, for example, why there are very few great tennis films (a pure swing in tennis or golf is impossible to fake), while baseball (an objectively easier sport to pick up) has one of the best movie rosters.

The other secret sauce to cinematic sports is making sure the audience can identify the players. Again, it almost doesn’t need to be said, but film is a visual medium, and the best movies show the actors’ reactions, body language or expressions, so that the audience is inherently more likely to connect to the characters. This is also why individual (boxing) and individualistic (running) sports tend to be more successful than large team sports (American football).

The final key to a great sports movie – and this is entirely my own theory and thereby is likely to be complete nonsense – is stats. I know I just railed against the inadequacies of using stats in sports, but I think that if you can quantify the effort and contribution of each player in a sport, it makes it easier to portray it in a movie. In these sports, because it’s easier to see the importance of every player and every action, the filmmakers have a much easier job of setting up stakes in a way that even a novice to the sport could understand. Again, baseball comes to mind (it is after all the original Moneyball sport) but the example on the other side is football (as in soccer, not hand-egg). I think I might get yelled at for this one so let’s just start there.

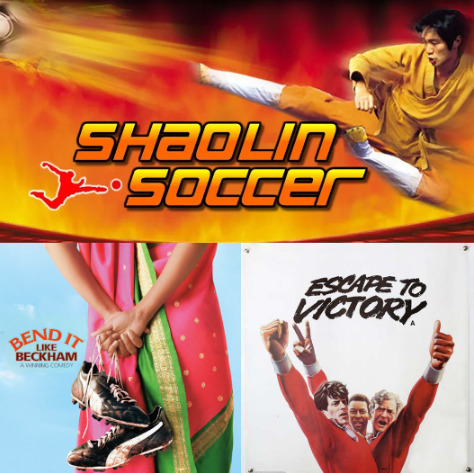

Football is the least stats friendly of the major sports, because it’s such a fluid sport where the players’ contributions are so interwoven that it’s hard to quantify what an individual player means to a team – and indeed the importance of any single character to a narrative about football.

Quick aside: In Bend It Like Beckham, both Keira Knightley and (especially) Parminder Nagra have unimpeachable levels of jock credibility, which is what sells it to me as a sports movie, even if the amount of football depicted is a bit sparse.

What I find amusing is that the other nearly impossible to adapt sport, tennis, has the opposite issue of football. It’s very easy to relate to the player, but it’s unbelievably hard to fake being good at tennis (see: 2004's Wimbledon – or don’t). There are very few good tennis movies.

I don’t know if I can overstate how in the pocket I am for any basketball movie. To me, there are 5 great basketball movies, but there will seem to be one glaring omission, a pretender that everyone loves to bring up: Hoosiers. The gameplay in Hoosiers is awful, Gene Hackman (an actor I love) looks legitimately afraid of getting bonked in the head by a ball and the message is hacky and plays on racial prejudice. Plenty of movies have done the tough new coach concept better since then (Coach Carter, The Way Back, Hurricane Season). We certainly don’t need Hoosiers any more.

I’m not much of a baseball fan, but baseball is the best screen sport for the same reasons that I think the real life version is quite dull. The games go on forever, it is a relatively unshowy sport (in terms of athletic feats) and there is enough time between each ball to have dialogue, make stressful decisions and build tension. Baseball is a poetic sport, the pounding thump of the ball against a glove, the crack of the bat when it connects, a runner sliding through the dirt to get to base. Movies about the great American pastime often tend to be similarly long, with a soothing energy and a quick (if quiet) wit.

To be fair, all of the above this can be said about cricket as well, so why have there been so few attempts at making a great cricket movie? I think the big difference is, where baseball gives the teams the opportunity for a back-and-forth in scoring, cricket is structured in a way that each team only has one chance to score, making it harder to show realistically dramatic shifts in momentum.

And more than any other sport, cricket and baseball are easiest for a newcomer to keep up with: there’s a ball, you gotta hit it. What’s confusing about that?

With cycling and track sports, there is something that fascinates filmmakers. It might be a yearning for the near-total sense of control over one’s own achievements and failures that a track athlete might feel, which is antithetical to the inherently collaborative nature of moviemaking. Or maybe it’s a sense of kinship with the singular focus of the athletes and their constant tinkering with the most minute aspects of their craft that attracts legendary script doctors (Robert Towne) and detail-obsessed directors (Michael Mann). Whatever the reason, track movies tend to be philosophical and often pure meditations on determination and willpower.

Pugilism. The sweet science. I started to obsessively watch boxing movies after I read Budd Schulberg's book Ringside. At the end of the book, he included an essay on the best boxing films in which he broke down the artistry in faking a fight for the silver screen. That really seeded itself in my brain and sprouted into such slightly unhinged takes as "Creed is the best Rocky movie" or "Ali examines the complicated public, personal and interior life of an iconic boxer better than Raging Bull". The stakes in a fight are clear and most actors relish the chance to get into absurd shape and take their shirt off, so the pugilistic picture show will likely never die.

Sidebar: Million Dollar Baby is often listed as one of the best fight movies and it likely is, but I watched it once a long time ago and it was one of the most thoroughly soul-crushing movie watching experiences of my life. I haven't been able to rewatch it since.

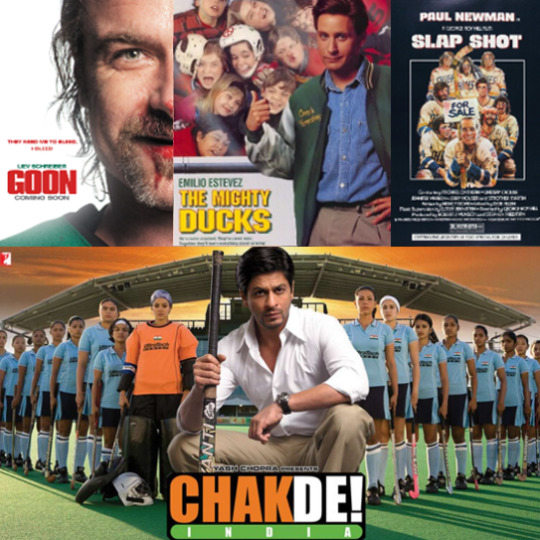

Field hockey is a rare movie sport for the same reasons as football, and even though Chak De India towers over most of the sports movie heap, it is not in general a cinematic sport. Ice hockey on the other hand is a much more dynamic game because it has some element of fight sport ingrained into it. And as much as I love Paul Newman's beautiful, soulful, sparkling blue eyes…

Sorry, what was I saying? Oh yeah, Goon has snatched the title of best ice hockey movie from Slap Shot, because it's basically what if Rocky wanted to be in a team sport.

There are of course other sports that have received the silver screen treatment: American football (lots of okay movies but honestly none as good as the TV show Friday Night Lights), golf (Tin Cup, starring the movie king of sports Kevin Costner), racing (the impeccable Ford v. Ferrari) and so on and so on. Hell, one of my favourite movies of all time period is The Color of Money, and while that’s only half about shooting pool, it gives the audience, in parts, the ecstatic highs and the rock bottoms of a great sports story.

But I think the subgenre that is the undisputed king of the sports movie right now is management. Like most non-traditional movements in modern sports, this starts with Moneyball. Is there a greater sports movie with less gameplay than Moneyball? No. Is there a sports movie that makes me choke up as reliably? Also no. It's filled with peeks into the behaviour of athletes, the superstitions and the motivations, the behind-the-scenes drama. One of the very few perfect films in my book. And while that's the peak of the management movie, there are some really strong movies in this category, from aspirational stories (Hustle) to morality tales (The Damned United) to weird experimental movies about the possible future of athlete management (High Flying Bird).

Odd to close this with management, but that’s where we’re at, with sports movies to sports fandom. Everyone on the internet thinks they can manage or coach a team better than most professional managers or coaches, and movies are here to tell them, “Hey, maybe not.” As usual, I side with the movies.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Top 25 Movies of 2022

When I think about 2022, the highs of the year feel like a return to form, for movies and for myself personally. And yet, on further inspection, it’s possible that two straight years of largely garbage movies and even more garbage circumstances have set the bar rather low. Yes indeed, this year has been better in comparison, but it has not by any means measured up to “normal”.

There have been some bright spots – travelling all over the country to meet friends, watching movies I’ve been waiting to see for several years, etc – and there have been some dark recesses – of the mind, yes, but also whatever the fuck has been happening at Warner Bros. Discovery. And as far as my empty promises of lots of new pieces that I made in my first ever post, the ideas are still there, I just haven’t yet made most of them as coherent as I’d hoped. However, I have some breaking news for you: the year’s over, which means it’s time for the highlight reel babyyy! You’ll only find best-ofs here (sorry to The Gray Man) as we kick off another year.

Quick note to anyone who didn’t read the Shepitko piece: I’m totally on your side. It’s too long and too much like a SparkNotes summary of a biography. I wrote it while I was stuck deep down a well of love for this incredible artist who thought much along the same lines about art: “If I don’t do it, I’ll die.” Is that a sideways excuse for why I haven’t updated this blog in a long time? Maybe…

But back to 2022. An incredible year for theatres: Top Gun Maverick recreating the late great Tony Scott’s aesthetic for a fleeting 2 hour thrill ride was something I never expected. Avatar: The Way of Water leading the charge for high quality, must-see-in-3D movies on the other hand was something I completely expected and yet I still walked out absolutely in love with Pandora. The return of Jaws, ET and The Godfather in the form of picture-perfect restorations and pristine transfers was such a perfect lure back to theatres.

But as with any year, I saw most movies this year in my bedroom or on TV. 594 is a very large number, which troubles me. I worry that I watch too any movies – do I really process what I watch or is it robotic? Am I just putting on movies as a way to distract myself, and if so, is that fair?

I don’t really have answers there. It has certainly felt mechanical at times, and I felt like I reached saturation, occasionally feeling like I didn’t even care about movies. And then, just in the nick of time would come something like Crimes of the Future, a nasty piece of mystery fiction, but nasty in the best possible way, twisted by ol’ Dave Cronenberg to forefront his own preoccupations with the human body and relationships. Suddenly, I’d be back in love with films.

So what can I do? I’ll keep watching movies, but maybe slow down a little. Take time to process each movie before moving on. Watch with more purpose, more discernment. Maybe I don’t need to watch ALL of the new Pinocchios (del Toro’s is by far the most enjoyable, Zemeckis’ is a complete nothingburger and the Russian one is… unfathomably awful). And most of all, I’ll write more, because that helps me connect to movies more than just letting it swirl around in the cesspool that is my mind.

But enough of the rambling preamble. As a movie year, 2022 was twisty and all over the place. A great year for Tom Cruise and Colin Farrell (who was excellent in FOUR WHOLE MOVIES THANK YOU to the film deities!!), a great year for horror, a great year for weird shit that seemed to be aimed directly at me. A terrible year (I know I said no negativity so I’ll get this over quickly) for unfortunate franchises (Branagh’s Poirot, Jurassic World) and Tom Hanks, who was in the bad Pinocchio and generally agreed to be the worst part of Elvis. Undecided result for Margot Robbie, who was passably charming in an inexplicable film (Amsterdam) and reportedly excellent in an unmitigated flop that I’m excited to watch (Babylon).

I watched 141 movies released in 2022. Here are my top 25.

25. Causeway

24. Saloum

23. Save the Cinema

22. Bheeshma Parvam

21. The Lost King

20. Pada

19. Everything Everywhere All at Once

18. Nope

17. God’s Country

16. Hinterland

15. Hustle

14. The Northman

13. The Banshees of Inisherin

12. Prey

11. Benediction

10. Fire of Love

This was among my most anticipated movies of 2022. It’s rare for me to be so excited for a documentary – I usually stumble upon them and then get pulled into loving it. And unlike another documentary from this year that I loved (my precious Good Night Oppy, which made me cry, much like most movies about the space program), I wasn’t really pre-disposed to loving it. I’m a space guy, not a lava guy. Yet Fire of Love is special, because the premise promises a tragic love story, but from the first moment that we see the Kraffts, we realize that this isn’t tragic to them, no matter the outcome. They understand the risks fully and still it’s completely joyous for them. And the footage of the volcanoes is mesmerizing, you almost understand how inextricably drawn they felt to them. NatGeo, two years running, making my best of year list. I’ll keep my eye out for their 2023 releases.

9. The Woman King

This is Gladiator with most of the flab cut off. Gina Prince-Bythewood is one of my favourite working directors and her shift into action filmmaking is really remarkable, considering how emotionally focused her first three movies are. It makes sense though, once you realize that her action scenes are so fluid is because she herself is an athlete and she frames the scenes, not just as balletic or violent feats, but as a show of athletic prowess. From the opening – which is very reminiscent of the first Nakia scene in Black Panther – I was fully on board with the tone and scale of this movie, boosted in no small part by Viola Davis (the biggest Oscar snub of the year), Lashana Lynch (being an absolute dynamo on screen) and Thusu Mbedu (who somehow holds her own as a co-lead in this movie opposite Davis).

8. Jackass Forever

Like every iteration of Jackass, Forever is wonderfully juvenile, but there’s an added tinge of melancholy in watching Knoxville, Steve-O, Dave England and the rest of the original cast slowly come to terms with the fact that their bodies can’t take the same levels of punishment anymore. We see them hand over a lot of the stunts to the newer additions, who take the reins while also trying to get out of the giant shadows of Ryan Dunn and Bam. All that said, Knoxville and Steve-O still do the two most what the fuck gags in the movie, and Danger Ehren, as ever, is the victim of a nightmarish flurry of pain. But Jackass isn’t about violence; it’s just the most stupidly violent franchise about friends who love each other.

7. Kimi

Any movie Steven Soderbergh puts out is likely to make my best of, and it speaks to the quality of the top 10 this year that Kimi has dropped to the back half. This movie is fun as hell, an old school conspiracy thriller in the vein of (quite obviously) The Conversation and Rear Window, but set in a tech world that’s increasingly more familiar – and more frightening – to us. Of course, Soderbergh isn’t new to conspiracies (see: Erin Brockovich), but the thing that makes his work in Kimi particularly enthralling is his ability to capture natural human behaviour on screen. He makes excellent hangout movies (Oceans 11-13, Magic Mike, Let Them All Talk) because he knows that if you shoot movie stars in a certain way and pace it right, anything they do will be immensely watchable. And for Kimi, he teamed up with one of the very rare true-blue movie stars under 35 in Zoe Kravitz. She pulls the camera with a natural, easy magnetism that automatically sets us up on her side. Add Soderbergh’s excellent technical craft, and you get a lean, mean, murder mystery machine that has you in and out and completely satisfied in 90 minutes flat.

6. Top Gun: Maverick

Often the Best Actor/Actress Oscar is won by someone doing an interpretation of a real person that we’re all familiar with (Rami Malek for Freddie Mercury, Renee Zellweger for Judy Garland and possibly – god forbid – Austin Butler for Elvis). I think that should just be its own special Oscar: Best Re-Creation. And this year, Top Gun: Maverick should win that honour, because Joseph Kosinski (who I’m overall pretty mixed on as a director) does a spectacular job recreating that early Tony Scott style that made the first Top Gun so exhilarating. Funny thing, leading up to the release of this movie, I put my favourite Tony Scott movies on TV (I’ll take any excuse really). My sister walked in during the first 10 minutes of Unstoppable and not only was she completely hooked, but she insisted on watching the rest of the movies with me. So it was particularly fantastic to be able to show my sister a Tony Scott-esque movie in theatres for the first time. I wish there were more of them.

5. Avatar: The Way of Water

Yes I loved it. Am I a sucker for Jim Cameron? Also yes. The water footage is like watching NatGeo from another planet (in a good way, you should know by now that I’m a fiend for NatGeo). Cameron knows how the build tension in an action scene and he also knows how to shoot it so that you know exactly where everyone is in relation to each other, which seems to be a lost art in big budget blockbusters these days. But what gets The Way of Water to number 5 is the tulkun. What an incredible idea to have this species of space whales be intellectually and emotionally smarter than the Na’vi and yet have them choose to intertwine themselves with the Na’vi. And the decision to introduce this kind of an interspecies dynamic in the SECOND MOVIE when there’s is no analogue for it in the first, is a feat on its own. Although I should have probably recused myself from reviewing this movie, since Payakan is my best friend.

4. The Fabelmans

Steven Spielberg has always been a filmmaking savant, which this movie will tell you, but I think what makes The Fabelmans so good, and what has really been working for Spielberg in this last decade, is that he tackles honest, complex emotions head on instead of eschewing it for the classic Spielberg sentimentality. He portrays the intricate and overlapping familial dynamics in the Fabelman household (a thinly veiled depiction of his own home life) with shockingly little guile or deflection and shows us not only the joys, but the strains of being an artist.

3. TÁR

Hard to talk about this movie without just lavishing praise on Cate Blanchett, but I’ll try – not because she isn’t the best thing about it, but because every discussion about TÁR is so dominated by Cate Blanchett that other great parts of the movie fade into the noise. Todd Field as an actor is best known as Nick Nightingale in Eyes Wide Shut, but his work as a director in TÁR reminds me of the second half another Kubrick movie: Barry Lyndon. To start the movie at the peak of someone’s prowess and document their downfall, and not have audiences utterly despairing by the end is a special talent that few have, and Field certainly nails it. Noemie Merlant (of Portrait of a Lady on Fire fame) is an absolute beacon of charisma as Lydia Tar’s assistant, and her performance subtly elevates the audience’s investment in the story. But I think the secret sauce to the movie, and the emotional crux, is on the shoulders of Nina Hoss, who has very little screen time, yet really underscores the whole movie with one incredible line reading. The individual pieces of TÁR are excellent in their own right, which sometimes poses a problem when the filmmaker tries to put them all together, but the movie is so well-conceived and Field has such a strong artistic voice that the brilliance of each part only works to elevate the whole.

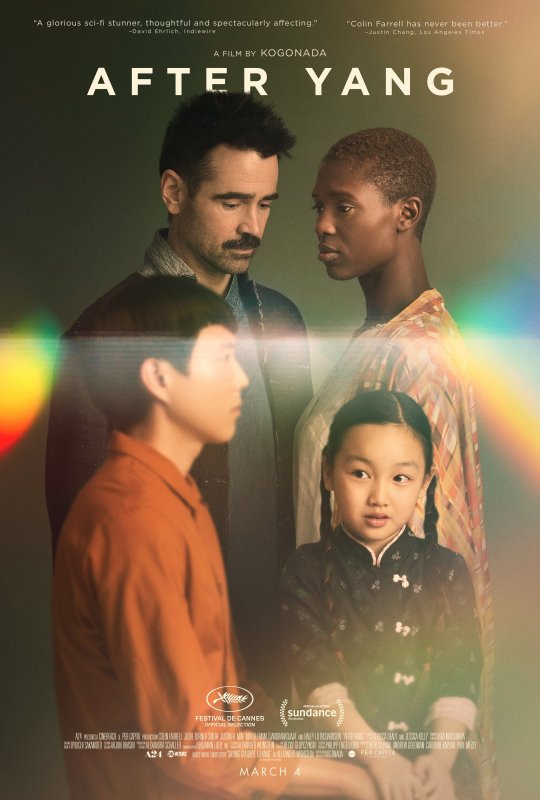

2. After Yang

The first of Colin Farrell’s 2022 movies remains my favourite, which is a shock because I would have put money on The Banshees of Inisherin being my number one movie of the year overall. And though Banshees has been slowly creeping up my rankings the longer I think on it, After Yang has held strong for nigh on a year. Kogonada’s first movie, Columbus, juxtaposed an emotional gentleness with the sadness of real life in a way that didn’t make me want to run away as movies like that normally do. Instead, he made the real world an enviable gentle place that doesn’t magic away tragedies but accepts them as an essential part of every person. In After Yang, Kogonada takes that sensibility and applies it to a sci-fi idea that is perhaps as old as the genre: what if a robot began to feel? The set-up is, on paper, similar to classics like Blade Runner and AI, but the movie is handled with a tenderness that those earlier movies had only sparingly. There’s a lot in After Yang about loss and grief and parenting, but also about the joys of culture and art.

1. Three Thousand Years of Longing

If you go back to my list last year, my number one was Night of the Kings, a Ivorian prison drama about the importance of storytelling. So I guess it’s pretty boring that this year, yet again, I’ve picked a film that features tales of magic and wonder. Three Thousand Years of Longing is a djinn movie, but what sets Three Thousand Years apart is the way these fairytales are portrayed. Rooted in real history, the stories have a sense of dream logic that makes every instance of magic makes sense. And the main story itself, much like another movie I loved this year (Good Luck to You, Leo Grande), cautiously but lovingly explores the awkward romanticism of two strangers in a hotel. Idris Elba’s Djinn is wary of his summoner, while Tilda Swinton’s Alithea, a scholar of storytelling, is well aware of the mischievous nature of djinns. Hijinks do not ensue, however. Rather, the two of them slowly let their guards down, as the Djinn warns Alithea of the dangers of previous wishes he’d had to grant, weaving tales of a mystical history that has her (and me) completely enraptured. Three Thousand Years feels to me like the closest a movie can get to the magic of bard recounting an oral tradition of love and war and the follies of humans.

***

As usual, some honourable mentions:

Decision to Leave, Good Luck to You, Leo Grande, Athena, A Man of Action, Mukundan Unni Associates, Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood, Watcher, Something from Tiffany’s (a very solid romcom) and motherfucking Ambulance because what a goddamn ride that movie is.

I don’t recommend stand-up specials often because nothing is less appealing than comedy recommendations. But Jerrod Carmichael’s Rothaniel is really the most intimate special I’ve seen while still being hilarious.

I know I don’t talk TV often but Andor and Slow Horses have three essentially perfect seasons between them and I’m very excited for what’s next.

Finally, Dinner in America is the most punk rock movie of the year and I really hope it gets a bit more traction because there aren’t enough straight up fuck the system movies being made, which is a major bummer.

***

I want to end on a note of cautious optimism, but I’ve gone on too long already, so let me just say this: we’re probably getting new movies from our greatest working directors[1], not to mention new entries in some of the most high quality franchises. Yes indeed, folks, a promising movie year lies ahead, and you might as well stay tuned to Another Revue - who knows? I might be true to my word about writing more.

___

Soderbergh (Magic Mike 3), Scorsese (Killers of the Flower Moon), Michael Mann (Ferrari), Sofia Coppola (Priscilla), Miyazaki (How Do You Live?), Fincher (The Killer), Gerwig (Barbie), Yorgos Lanthimos (Poor Things and possibly And), Reichardt (Showing Up), Nolan (Oppenheimer), Shyamalan (Knock at the Cabin), Ridley Scott (Napoleon), Steve McQueen (Blitz), Jonathan Glazer (The Zone of Interest) ↩

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Grand Romance

When you watch too many movies, you get so bombarded with idealised notions of how the world should work that you’re automatically pushed to be a romantic or a cynic. Pride and Prejudice is one of my favourite books and I’m a sucker for You’ve Got Mail, so it’s pretty clear which side I fall on. And while I love me a good romantic epic, one of the love stories I’m most fascinated by took place behind the camera – and it’s between two people that you’ve likely never heard of.

Larisa Shepitko was born in 1938 in Soviet Ukraine. She was the daughter of a Ukrainian teacher and possibly an Iranian military officer, although sources conflict on this point. What we do know is that she graduated high school when she was 16 and was immediately accepted into VGIK, the state-run film university in Moscow. If she had graduated only two years earlier, she might not have been accepted into VGIK because of her non-Russian descent. But this was after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, and Nikita Khrushchev had begun his decade in power by reducing the restrictions on art created in and imported to Russia. This led not only to an influx of non-Soviet and non-Russian art and expression, but also opened the doors for Soviet artists who were not from Russia (like Shepitko) to access Russian resources (like VGIK). This decade of reduced government control over art is known as the Thaw.

When she joined VGIK, Shepitko was the only female student at the institute. Her talent was quickly spotted by Alexander Dovzhenko, a professor, fellow Ukrainian and one of the most influential film theorists of that period (he fine-tuned Eisenstein’s montage theory which, inelegantly put, is “if a picture’s worth a thousand words, a series of video clips must be worth a million”). Shepitko made a name for herself as an original, someone whose style did not seem to be an evolution of anyone that came before her, but rather an authentic representation of how she sees the world. In a class filled with some of the most recognizable names in Soviet film – Tarkovsky, Parajanov, Shukshin, etc. – Shepitko was highly respected and well-liked. By the time she graduated, Shepitko was considered one of the most promising directorial talents in the Soviet film industry.

But before we get to that, let’s meet the other person in this grand romance. Elem Klimov was born in Stalingrad to a Russian family in 1933, and had vivid memories of fleeing with his mother and younger brother during the Nazi siege of the city. He wanted to be a fighter pilot, but soon after graduating from the aviation academy, Klimov decided he was better suited to filmmaking. He then joined VGIK, where he quickly became known for his skill at editing and, as his studies progressed, he would often practise his techniques by helping other students edit their work. Respected though his skills were, Klimov was not quite as well-liked as Shepitko, nor by her. He, in turn, kept his distance. So begins the story.

To graduate the film institute, a student had to create a graduate film rather than a thesis. Usually, these films were screened for the faculty and a few classmates and promptly forgotten. Not Klimov’s. His film was so well received that it was projected on the walls of the institute, and the film gained a moderate cult following amongst other students. Shepitko’s graduate film was a bit different. Whereas most films of this kind were personal or scaled down in order to save on costs, hers was a sprawling effort. It was the story of a freshly graduated engineer who is assigned to work on a collectivist farm during a heat wave. It’s a clear, simplistic allegory for Stalin’s perversion of Soviet ideals (a popular theme at the time), but what captured Shepitko’s mentors, peers and audiences was how visceral and real the film felt – because it was, in a way. Shepitko had convinced a cast and crew to travel to and shoot on the barren steppes of Kyrgyzstan in the summer when temperatures soared to over 50°C.

It was so hot that the film would regularly melt inside the cameras, exacerbated by her insistence on exceedingly long takes. But there were no complaints about what on paper seem to be ridiculous demands, because she had subjected herself fully to the same conditions that she asked her actors and crew to work through. She did not rest in the shade but instead was out under the blazing sun for every single scene. As a result of this overexertion, she contracted jaundice and was briefly hospitalized. But she was determined not to waste her crew’s time so, ignoring doctor’s orders, she soon returned to set. She was too weak to stand, but somehow managed to complete the film from a stretcher. But then came editing. In those days, editing required just as much, if not more, physical control and precision as actually filming the movie, since it involved physically cutting a strip of film with a blade and taping it to another strip, over and over again, in the exact right spots, taking particular care not to damage it. When Shepitko returned to VGIK, she was still in no condition to be so precise – turns out, jaundice is kinda tough to beat if you’re not actually doing the rest and recovery thing – and she had to resort to the resident film editor, a one Elem Klimov.

When Klimov saw the raw footage that Shepitko brought back, he understood the scale of her vision and dedicated himself to making obvious her talent through complementary editing. Together, they were a perfect combination of their styles and ethos. Nothing fancy – it’s a simple, slow-paced kind of a movie – but the fluidity of the scenes and the slight nudges he adds through quick cuts and insert shots liven up scenes that could otherwise seem stagnant. It seems more like a 90s arthouse flick than a student film from thirty years prior. By the time the editing process came to an end, they had fallen in love – but the film still had no name. So they made a bet: whoever came up with a good name for the film would win ten roubles from the other. Elem struck gold with Heat, Larisa grudgingly paid up and a tradition was born.

Remember the Khrushchev Thaw and how I said it was 10 years long? Well it ended almost immediately after the release of Heat. Brezhnev came to power in 1964 and he was much more of a Stalin than a Khrushchev. The officials at Goskino (the Soviet film ministry) got scared that Brezhnev might not appreciate a movie condemning totalitarianism, and one of them decided to ban Heat. It seemed like the end of freedom in Soviet film culture, but the directors from Shepitko’s generation had gotten too used to the freedom of the Thaw and many continued to push boundaries for the rest of their careers.

Right out of VGIK, Larisa and Elem married and the couple was an immediate hit in the Soviet film community. “He was tall and elegant; she was stunningly beautiful. They shared a Russian sense of irony, black humour and introspection.” They had decided to never work together again, not out of any dispute, but because they were well aware of the impact that could have on their reputations – particularly hers. At a time when you could count the number of acclaimed female directors on one hand (if you could think of any at all), they both understood that if they worked together, the nasty wheezes of bruised masculine egos would declare that “Klimov is actually the brains behind Shepitko’s movies, he just lets her take credit.” So Elem and Larisa, the young power couple of Soviet film, part ways professionally by the end of 1963, even as they enjoy an increasingly happy and supportive marriage.

Between 1964 and 1971, they each make 3 films, as well as a section of an anthology directed by Shepitko and two episodes of TV by Klimov. Over the course of these 8 years, they develop their own reputations as directors: Klimov, the dry wit with the light touch, and Shepitko, the intense, radically immersive investigator of the human condition.

Klimov’s first two movies, Welcome (a comedy set in a summer camp) and Adventures of a Dentist (a darker comedy about a dentist with an exceptional talent for pulling teeth painlessly), were satirical but not particularly incisive, while his third film, Sport, Sport, Sport is a weird compilation documentary from about the history of modern sports with a special spotlight on Soviet developments. The third was the only one of the three released wide across the Soviet Union. He was known as a clever but somewhat whimsical filmmaker, and someone who likely would not make a lasting impact.

Shepitko, on the other hand, was known for taking on ambitious projects and committing herself fully to making her movies. Although she had barely studied with Dovzhenko for 18 months before his untimely death, he had a profound impact on her ethos as a filmmaker. His greatest influence on her seems to have been the idea that the instant an artist lies or compromises their values in the making of art would be the absolute corruption of that artist. She would later say,

“every day, every second of our life prompts us to fulfil our everyday needs by making some kind of compromise […] But it turns out that while everyday life seems to let us cheat for five seconds and then make up for it, art punishes us for such things in the most cruel and irreversible way.”

Every film Shepitko made was true to her conscience without hypocrisy or moral compromise, but her humanist lens keep them relevant and decidedly not preachy. Today, the idea of a moralist filmmaker seems a little outdated and overbearing, a holdover from an era where cinema was the most easily comprehensible way to spread information and ideas. We now have the internet and anti-heroes are all the rage. Even when we get movies submerging themselves in questions of morality, there seems to be a general preference towards the existential nihilism of something like First Reformed over the moral maximalism of Mallick’s A Hidden Life.

Wings, her first proper feature film, explored the life of Nadezhda (Nadya), a Russian WWII fighter pilot and war hero who had, in the two decades since the war, sunk into a mundane existence as headmistress of a trade school. Throughout the movie, Nadya is often faced with either an uncomfortable, grudging respect from older generations who revere as a hero or callous indifference from her students, who were not alive during the war and can’t appreciate why she receives this respect. Wings brings up questions of survivor’s guilt and generational conflict through the study of Nadya and with Russian culture – for example, the name of the lost and listless main character, Nadezhda, ironically means “hope”. Wings was released to a limited audience but, to Sheptiko’s shock, almost immediately banned because of the public discussions it inspired about the mistreatment of veterans as well as the disconnect between parents and children.

Let’s talk about censorship for a second. In the Soviet Union, film censorship depended almost entirely on the interpretation of individual censors, with few (if any) hard and fast rules. This method led to a very unpredictable track record for what was and wasn’t acceptable. It also led to extremely subjective and prejudiced censorship on account of inherent biases. For example, Klimov’s Adventures of a Dentist was deemed too critical of Soviet culture. But when he declined to change anything in the film, the film was demarcated a Category 3 movie, which meant it could only be screened at age-restricted theatres. Meanwhile, when Shepitko declined to soften the messages of Wings, it was banned outright. She would continue to face these obstacles throughout her career, no doubt because she was a woman who had a “severe, non-womanly” style, but in large part because she was also Ukrainian.

Under Brezhnev, the USSR pushed for all Soviet states to be Russified, wiping out large swathes of local and indigenous culture in favour of Russian nationalism. Artists expressing any Ukrainian national consciousness in Ukraine or Russia were attacked, arrested and sometimes sent to gulags. Larisa Sheptiko was constantly under scrutiny from Goskino, made all the worse by her tussles with the censors over every movie she made, because every single one seemed to cross the line of acceptability. And due to her Ukrainian heritage, the authorities made “official efforts to ignore and repress her work as much as possible”.

It didn’t even matter how aligned with Goskino’s agenda her films were. For example, right after Wings, Shepitko took part in a historical anthology film celebrating the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. But the realistic portrayal of the Bolsheviks – and Shepitko’s refusal to compromise – scared the Goskino and they destroyed the film, including Shepitko’s segment, The Homeland of Electricity. Another fairly simple premise steeped in Russian culture, it was the first movie where her directorial style had approached its full potential, with carefully crafted shots that explore the purposeful movement of the camera and the use of extreme close-ups. Jonathan Demme and PTA popularized the repeated use of shots where a character’s face fills the frame and they unflinchingly deliver dialogue looking right at the camera. But I think Shepitko uses it in the exact same way they do – to evoke empathy or provoke disgust or simply to ensorcell the viewer. I admit, this is where my ignorance shows; I bet other directors were doing the exact same thing before her, but Shepitko is the earliest example of this that I can think of. And as far as camera movement goes, she’s squarely in the Kurosawa camp, where every movement has a beginning, middle and end (this video essay explains it perfectly). Nothing wasted, nothing excessive, her movies are almost ascetically told.

Which is why I was devastated to find that Shepitko’s next feature film, 13th Hour of the Night or 13 PM, seems to be lost to time. Her first foray into colour, 13 PM is a musical comedy about various Russian and Ukrainian fairytale characters who get together to celebrate the New Year. The contemporary reviews indicate that it’s fun in a slightly demented way, and it’s almost unimaginable the often stoic style of Shepitko could give way to something so dynamic as a musical. Thankfully, her next film, You and Me, is similarly playful at times (it starts with a homage to the Bond movies), which is a bit surprising, since it was a nightmarish production for Shepitko.

By this time, Elem has taken a break from his career. He’s exhausted, not just from his own fights with Goskino, but also supporting Larisa through hers. Elem also seemed disenchanted after making a fluff piece like Sport, Sport, Sport; so when Larisa takes up You and Me, Elem is just along for the ride, making sure she doesn’t overdo it. Good thing he was there too, because this is the movie that kinda broke Larisa. The story seems simple enough: two surgeons who were classmates in medical school meet after years and compare their drastically different lives, goals and ambitions. The movie explores their regrets and their desperate attempts to make amends.

Of course, government bureaucracy and red-tapism made the production anything but simple: permits were hard to obtain, forcing the movie to be shot at an irregular pace. The cast and crew had to be ready at a moment’s notice because no one knew when a day’s permit would be issued and they had no time to waste. The crew supposedly worked at secretly reduced pay in order to keep the budget within reasonable limits. Yuri Vizbor, the lead actor of You and Me, later said:

"We worked for Larisa, specifically, personally for her. She had faith and that was the reason. Faith in goodness and the need for our work, and it is this faith that was absolutely a material substance, which can be very real to rely on."

When asked for her reasoning behind choosing projects, Shepitko once said she only picked movies where she felt that “If I do not do it, I will die.” And she frequently approached the actual work as if she would be willing to die in the process, as long as she made a great movie. On the set of You and Me, she collapsed and reportedly had a heart attack (although she always denied it). While she was taken to the hospital, Klimov took over shooting for the day. Only for the day though – Larisa was back on set the next morning, pushing it right along.

The censors did not receive You and Me well and the movie was re-edited with a heavy hand, so much so that Shepitko lamented privately that it lost many of its central ideas. Shepitko fought tooth and nail to keep her movie uncut and uncensored, but the authorities sent their own edit of the film to the Venice Film Festival and it won the Golden Lion. It’s a testament solely to her prodigious skill that while so much of this movie had been chopped and screwed, there are still some shots and moments in the movie where her vision and style seem to shine through. As far as I can tell, that is the only version of the film that has survived.

After the disaster that was You and Me, she tried to revive herself by working on an adaptation of a famous Russian nationalist book, Belorussian Station. But the authorities caught wind of what was supposedly a clinical and pessimistic adaptation and shut her down before it could take off. At this point, Shepitko could not go on. She was so exhausted that she checked herself into a heart sanatorium for a short stay which was extended indefinitely after her initial mental fatigue compounded by a cold she caught there. Then, a few months in, she suddenly felt rejuvenated: “I came to the sanatorium without a voice, […] but […] the feeling returned that my cells are able to bear fruit."

But that newfound energy dissipated quickly, because she soon had an awful fall, leading to a serious spinal injury that would cause her severe pain for the rest of her life. The timing could not have been worse; not only was she actively pursuing new films but she found out around that time that she was pregnant. The recovery period from the initial fall, leading through to her pregnancy, instilled in her not a fear of death, but an anticipation and understanding of it. Larisa writes, “I sensually embraced the concept of life in its entirety, because I perfectly understood that every next day I could part with my life. I prepared for this. I will die.” She spent those seven months introspecting for the most part, but one of the few books she did pick up was Sotnikov by Vasil Býkaŭ. Sotnikov is a story about Belorussian partisans in WWII, and questions the strength of the human conscience and spirit in times of desperation and interminable struggle. Shepitko connected to this story and decided that she would make this movie if she survived long enough.

So, once Anton Klimov was born in 1973 with no notable complications, both Elem and Larisa embarked on projects that would take years to come to fruition. Klimov decided on a biopic of Rasputin, while Shepitko kept her word and undertook an adaptation of Sotnikov. Klimov’s movie, Agony, is his first attempt at making a historical epic and a serious drama. The production and release of the movie was troubled because of Klimov’s determination to portray Tsar Nicholas II as a three dimensional character rather than the snivelling caricature that was then pervasive throughout Soviet culture. Perhaps this obstinacy is something he picked up from Shepitko in his time off, but he refused to surrender his vision of the character. So Agony was delayed several times and, before it was finally released in 1981, it was re-edited to add footage that glamourized the October Revolution. As far as Klimov’s directorial style goes, it has some of his quirks but is narratively unfocused and generally not very interesting.

Meanwhile Shepitko had made significant progress in adapting Sotnikov. She got permission from Býkaŭ to adapt his book and immediately contacted an in-demand screenwriter, Yuri Klepikov, who was recommended a mutual friend. Klepikov was working on something but said he’ll start on Sotnikov after a week. Shepitko called him up and at the end of the conversation, he had already begun work on Sotnikov as his first priority. He says he "could not withstand the energy of the typhoon whose name was Larisa.” He soon sent her the script and Shepitko edited everything to perfection, down to the directorial decisions. The only thing she left to chance was the weather. After a four-year long struggle with Goskino over the script (which was viewed as being religious) and the cast (who were mostly unknowns and non-professional actors), she finally got the approvals she needed and started filming.

The book, and therefore the movie, was set in the mountains after the first snow. Shepitko refused to shoot anywhere else or to fake the snow. The movie was shot outside, in a mountain village, in the freezing cold. This may seem like an over-commitment to realism – the actors could of course pretend to be cold – but it yielded some astonishing results. There is one particular scene where Sotnikov and Rybak (his companion in this mission) are pinned down and have to stay low to avoid Nazi gunfire and they end up rolling through the snow. I have never seen a movie where snow envelopes people so realistically and the actors look so genuinely uncomfortable and cold. Shepitko’s cast and crew seemed to understand how important this movie was to her, and they endured the harsh conditions in silence – as did she. Before every outdoor shot, she would sprinkle snow in her actors’ faces to keep them looking cold and fresh, but she’d have them to do it back to her. In scenes where the characters ran up a snowy slope, she – ignoring her residual spinal issues that had been exacerbated by the cold – ran alongside them, just out of frame. Some days, she would be so exhausted after the shoot that Vladimir Gostyukhin (who played Rybak) had to carry her from the car to the hotel room. The ingrained realism adds to the gut-wrenching impact of the movie as a whole.

Sure you hear director horror stories about extreme, ridiculously taxing shoots now and then – James Cameron nearly drowning members of his cast and crew on two different movies (The Abyss and Titanic) or Michael Mann filming parts of Miami Vice in an active gangland in the Dominican Republic – but those stories always end with everyone hating the director (after filming wrapped, the crew on The Abyss famously had t-shirts made that said “Life’s Abyss and then you die”). At best, you get the grudging respect that The Hurt Locker cast seem to have for Kathryn Bigelow. But Larisa Shepitko was apparently unreservedly beloved by everyone she worked with, because they had faith in her vision and trusted her commitment – and because she cared for them. Boris Plotnikov, who played Sotnikov, had to be dressed very lightly in the harsh Russian winter, so between takes, Shepitko would personally bring him blankets and warm drinks. And Gostyukhin, who also had extended scenes covered in snow, said the movie had “death in every frame” but that "It was worth it to die in the scene to be able to feel her gratitude."

When the film was finally finished in 1977, Larisa still couldn’t rest. She had gotten wind that the authorities planned to ban it and she along with so many others had sacrificed their time, comfort and health for her vision. At this time, Elem had gone through his troubles with Agony, which remained unreleased, and he was making his own WWII film about Belorussian partisans called Kill Hitler (cmon guy, you can’t just lift your wife’s idea like that). It was at this time that he had two great ideas. The first was suggesting that Larisa call the film The Ascent (or Ascension, depending on your translation). This was only the second time that either one of them had won the name game bet from their college days. Now ten roubles richer, he laid out a very rough Hail Mary scheme to circumvent Goskino. In the early process of making Kill Hitler, he had come into contact with Pyotr Masherov, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Belarus. Klimov asked Masherov to have The Ascent directly screened for the Belorussian government – a step which would bypass the Russian Goskino. Masherov, who had been a partisan in the war himself, did not believe that it could be an accurate representation of the war, in part due to what he expected to be “effeminate directorial work”, but agreed as a favour to Klimov. The screening was so important – and the film so freshly developed – that Shepitko herself was in the projection booth, controlling the sound mixing during the movie. She missed the entire screening and couldn’t tell how the audience had reacted. Her fears were compounded after the movie, when no one came out of the theatre for over an hour. She was sure that the film provoked some sort of negative reaction and had resigned herself to another gruelling, drawn-out battle with the censors.

Finally, the screening theatre began to empty and Elem found her and explained. Not only was the reaction positive, but Masherov had wept uncontrollably for several minutes after the movie ended, before giving what Elem described as the best speech he had ever heard about a film. Masherov said of Larisa, "Where did this girl come from, who of course experienced nothing of the sort, but knows all about it, how could she express it like this?" It was an incredible turn of events for both Larisa and Elem; they were still shocked a few days later when, at the insistence of Masherov, the Russian Goskino accepted The Ascent without any edits or changes.

The international reception was similarly ebullient: The Ascent won the Golden Bear at Berlinale in 1977 and Larisa Shepitko was soon hailed internationally and domestically as a true auteur and one of the USSR’s great working filmmakers. After the success of The Ascent, Larisa Shepitko seemed to have reached her full potential as a cinematic force of nature. Plotnikov, who instantly became a star, publicly referred to her as “a living genius” and the author of the story, Bykau, spoke of her highly to anyone who asked. But she was not one to rest on her laurels; she had already found her next movie. Farewell to Matyora was an ecological fable written by Valentin Rasputin, considered by many as a living genius himself. When Shepitko asked to meet him regarding the adaptation, he was quite determined to say no. He believed that it could not be adapted while staying true to the core themes messages of the book. But a few minutes into their first meeting, Rasputin found himself completely enamoured by Shepitko’s vision for the film and his “intention not to let go of Matyora" had been entirely forgotten.

Filming on Farewell to Matyora began in 1979, but Shepitko still had some locations to scout. One morning in June, she and four members of her shooting team set off to check out a new possible location. On the way, the driver fell asleep at the wheel. At 41 years old, Larisa Shepitko, the next great Soviet auteur, died instantaneously, along with everyone else in the car.

One week after the funeral, Elem was on set. If Larisa couldn’t finish Farewell to Matyora, he would do it for her. Elem finished the adaptation and, like he had twice before, came up with a more fitting title: Farewell. Only this time, he couldn’t collect the ten roubles. Farewell received mixed reviews: the critics appreciated the story and the visual beauty of the film, but noted that it lacked Shepitko’s focus and raw truthfulness.

Something in Klimov the filmmaker seemed to have changed in the process of making Farewell and Larisa. When he finally filmed Kill Hitler, it feels to me like he was guided by her emotional integrity and ethos. He renamed the movie Come and See and, upon release, it racks up all kinds of acclaim and awards. It is still considered perhaps the greatest anti-war movie ever made. It’s shocking and captures a lot of the same emotions as The Ascent, but where The Ascent is spiritual, Come and See is guttural. It is a movie solely about the brutality and perversion of war, but the thing that makes it so effective is that you don't just see the horrors. Several times we see the face of a character as a nightmare scenario plays out behind the camera – and when we finally see what the character was reacting to, the tension and fear has already seeped through to our minds and solidified in the pits of our stomach. This was something that Larisa Shepitko perfected early in her career, to heighten emotion and suspense in any scene by using an extreme, extended close-up on the main character's face.

With no evidence to support this except my own experience of watching their films, I think Elem, in the process of taking over Farewell and trying to stick to her style and her voice as much as possible, must have finally understood the desperation and the parts of her soul that Shepitko must have poured out into each of her movies. Klimov had never before made a purely sincere movie before Come and See - his earlier films were often satirical or a lens into history - and yet for this movie, he seemed to finally comprehend Shepitko's filmmaking mantra: "If I do not do it, I will die." While he was working on Farewell, Klimov had simultaneously made a short documentary called Larisa, a tribute and a sketch of her character – and perhaps a way to cope with her sudden absence. It’s not just a project borne of loss, but also a celebration of who she was, in her own words and in his. It’s really the story of their love, happy as it had been and tragic as it ended.

I said this was one of my favourite love stories, and it's not just because it's about two people who met in when they were young and seemed to love each other and enjoy growing together as people before one of them died an untimely death (although hey has that ever been done?). No, to me, one of the great achievements of any kind of love is understanding. Not just being understanding of someone, but understanding their core being, who they are, how they express themselves and their intellectual being. It's a very simple sounding thing, but it’s rare to so fully comprehend someone else that they organically become a voice in your head. Come and See feels to me as much a part of Larisa's legacy as Farewell because it's directly influenced by her sensibilities, while being packaged in Klimov’s own style.

Come and See single-handedly cemented Elem Klimov’s position in film history and he too was positioned as the next great Soviet auteur, except her never made another movie. In 2001, he said, "I lost interest in making films… Everything that was possible I felt I had already done." He went on to become the First Secretary of the Filmmakers Union, and fought for the release of previously banned films, including Wings, Homeland and Heat.

There is only one taped interview of Larisa Shepitko that I could find, conducted at the Berlinale the year after The Ascent won the Golden Bear. Unfortunate as that is, I was a little relieved at first. Often, when I fall in love with a filmmaker’s work, I tend to be disappointed by what they are like in interviews. It’s as if they’ve channelled their entire ability to communicate into their movies. So when I finally got around to watching it, my heart sank. It’s not that she was boring, but she seemed uninterested in the interview and visibly tired. She was also clearly choosing her words carefully when answering questions about spirituality in The Ascent and her intended message – the show was taped in Germany but of course anything she said would be analysed by the Soviet government and she could face severe repercussions. But as the interview goes on, Shepitko gets more expressive and passionate and we see a tiny glimmer of the director who ran alongside her actors up a snowy mountain just so she could feel what they felt. By the end, I was quite taken aback by how little exaggeration went into those enthralled descriptions of her. With piercing eyes and a commanding voice, she was a striking presence who came across as funny, empathetic, quite energetic and, above all, a woman of her convictions. So it is a little bewildering – and an unhappy state of affairs – that she is remembered now, if at all, as the wife of Elem Klimov. In fact, if you Google “greatest Russian directors”, he’s the 11th suggestion while she unfortunately doesn’t make the top 50. The only reason I came across her story and The Ascent is because she’s mentioned in passing on the Wikipedia page for Come and See, which I’d come across on a list of the greatest anti-war movies ever made. It’s surprising – or perhaps entirely too predictable in a world that tries very hard to forget the existence of women filmmakers – that Shepitko has been buried under the sands of time. It’s about time Larisa Shepitko took back her place in the film canon.

------

PS: The good news is, if you want to check out her movies, The Ascent and Heat have been officially uploaded to YouTube for free by their distributors with English subtitles. They have also uploaded Wings, but without English subtitles, which is really inconvenient. The Ascent is absolutely the movie to see, but if you can manage to find Wings with English subtitles, it’s one of the most moving, fleshed out character studies I’ve seen in a long time.

0 notes

Text

The Big Unwind

One of my grand unified theories of movie-dom (I have several, that’s definitely how unified theories work) is that, if you wanna get to know a cinephile, don’t ask them what they think the greatest movies are. Whenever someone asks me that question, panic kicks in, my mind blanks and I feel like the dumbest person on the planet (not a terribly uncommon experience for me). Instead, ask me what my comfort movies are – you know, movies to put on when you’ve had a bad day or you’re sick or maybe you just need this day to be over.

Someone’s comfort movies can tell you a lot about who they are and how they think about themselves. For example, I have a large and varied set of comfort movies, including romcoms (You’ve Got Mail, Pride and Prejudice), dark comedies (In Bruges, Blindspotting), the Harry Potter movies (particularly Sorcerer’s Stone and Prisoner of Azkaban) and even some gruesome horror (Green Room, The Thing). You could draw a lot of conclusions from that about me: that my taste is too broad or basic, or that I have a fundamental misunderstanding of the word comfort, or maybe that I turn to movies too often at any kind of aggravation at all (you wouldn’t be too far off on any count). Above all, however, the largest slice of my comfort movies pie is “old” movies – ie. movies from the 30s, 40s and 50s.

Alright, yes, I am aware that “old” isn’t exactly a concise category, but I think that a great many movies from that era (let’s call it the Big Unwind), regardless of genre, share some key characteristics that make them perfect comfort movies.

First of all, when you hear critics and old people say we don’t have movie stars anymore, they’re kinda right. Ever since the genesis of narrative film, there have been a handful of actors in every generation that would draw people to the cinemas just on account of their name alone. And by the peak of the studio system (the early-mid 40s), the process of constructing a movie star was perfected. A studio would often pick a young unknown actor, give them a name to remember and help them develop a look that audiences could latch on to – Chaplin’s moustache, Bacall’s smolder, Veronica Lake’s hair (if you know Jessica Rabbit, you kinda know Veronica Lake).