This is a chronicle, hopefully if I continue posting, of my various attempts at writing which I think are failed, and others happen to disagree, people whom I'm grateful to and unhappy with. If you're wondering what my blog's title means, see the existential comic about it!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Notes on power and inclusion

The question of inclusion has always been predicated on a simple, fairly apparent, possibly even measurable difference: the one between what you do because you're supposed to do it, and what you do because it makes sense and feels right. There is an intimate relationship between power and civility, orderliness, conduct, discipline, and how to BE. Power often dictates how we must act, carry ourselves, what we're allowed to do and what we aren't, or fundamentally, what is acceptable.

For example, consider: What decides whether you're allowed to walk on an escalator? Something you might notice in a mall or a metro station or any of those glossy sterile places-meant-for-the-affluent is the moment of hesitant terror that someone might have, standing paralysed in front of an escalator. I remember being in that position - my dad, a man of the world, knew what these contraptions were, but stairs moving on their own and getting swallowed up under the ground terrified me and my mother.

I remember feeling the need to treat these things as though breaking them would bankrupt our family (they would). Something about how shiny it was made me and my mother step on it very gingerly, knowing that in a fundamental way, this place is not home, and there are rules, some spoken, and some unspoken, and there are consequences for breaking them. Though there were some security guards peppered here and there, the real enforcement of these consequences seemed to be atmospheric. The kind of power that enforces these rules didn't have to shout at us or really even insist very much - the guards are really mainly for display, and the people who do end up paying fines are often those who have made mistakes, or haven't yet caught on to this projection of power.

It is not just the guard that enforces this rule, not really. After all, only a little part of my mother's paralysis was the machinery that her sari might get stuck in - a bigger part of it was the fear of doing something unacceptable around others who might be watching, and possibly laughing. In that sense the mall has co-opted all of us into being enforcers of the (un)acceptable.

Moreover, as someone who is becoming a 'person of the world' myself, I now know that there's nothing scary about the escalator. In fact, I even know that it's okay to walk on it and not just stand: it's been engineered to withstand being walked on. However, many people don't. Some might even look at me as though I'm vandalizing the escalator when I walk on it, and possibly even feel superior to me, "don't you know you're supposed to treat it gingerly?" Consider how this reinforces the power that the mall has of getting others to rally behind its rules of acceptability, even when they go against the laws of physics.

Only power can do this. When people look at a signboard announcing a rule, they do not always perceive the authority behind the sign or the power that really enforces it. It is not immediately clear, looking at a signboard that says "Stay behind the yellow line," that sure, standing behind the yellow line does save lives, but beneath it is really an unspoken power, one that dictates civic sense, from which the signboard derives its authority. One must never confuse this: it is not merely persuasive language; it is backed by material power.

This leads me to think about what is acceptable conduct around a transgender person. Language which has been designed (by whom? more on that shortly) to be respectful or accommodating has often been decried by its detractors as 'coercive'. It is quite easy to conjure up a mental image of a person, very easy to 'trigger', who demands to be spoken to and treated with in a very specific manner, using very specific kinds of communication. Often, this imaginary person is simultaneously so fragile that they might combust if spoken to in the wrong way, but so powerful as to coerce you into censoring yourself.

However, all speech is governed by power, the only difference being whether or not that power is immediately perceptible. The question of what is acceptable is a political question, and rendering some forms of speech and action (un)acceptable are political acts. Making something (un)acceptable, therefore, is not merely a matter of figuring out its language, but a matter of remaking the balance of power.

In plain words: if you want someone to not misgender you (or others), what gun are you holding to their head? It isn't that people don't have goodness in their hearts or are inherently disrespectful; the point is that your adversaries already sustain a certain standard of what is (un)acceptable backed by a lot of unspoken power.

People who have otherwise never had their authority questioned, or people who mostly fit into, or until recently used to fit into acceptable categories, might be under the impression that one must ask nicely, or scold, or sufficiently explain why they must be treated respectfully.

I will repeat myself here: your adversaries aren't asking nicely.

In fact, your adversaries have convinced people that they have naturally and reasonably arrived at the conclusion that you mustn't walk on escalators, or that there are exactly two sexes. They get to pretend now that you're the unreasonable one. People are as free to gender you as they are to misgender you, but they have been convinced that one of these options is free and the other is coercive.

A lot, therefore, is predicated on understanding what kinds of power you do and don't have. Can you pepper-spray your interlocutor and have a crowd take your side? Can you have someone removed from a space? Do you have buddies you can call and outnumber a small hostile group? People rarely do the right thing because it's the right thing. They usually follow a rule backed by authority or they break it if it feels good.

That's the last interesting thing that I want to point out: people love breaking rules and sticking it to authority when it feels good to do so. At the moment, there is plenty of authority asking the general public to be hostile towards transgender people. We are backed against the wall, but we have an incredible opportunity here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is "hijra" a slur? Contextualizing South Asian (trans)misogyny

A note on the sheer cultural diversity of the subcontinent

There is no realistic way for me to exhaustively examine the context of every South Asian transfeminized population (though believe me, I’d like to). As such, I’m going to limit my scope to India, but make a quick initial note about Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Pakistani transfeminized communities, according to my partner’s sisters who are in the community, do consider ‘hijra’ more derogatory than their Indian counterparts necessarily do and refer to themselves as part of the ‘khwaja sira’ community.

I have sadly not been able to speak to any transfeminine people from Bangladesh, but I have spoken to cis queers who have told me that they use ‘hijra’ in a manner similar to India.

If there are desi queers from those communities who would like to add their perspectives, please feel free to reblog. And for the South Asian communities I haven't mentioned (such as Sri Lanka), please feel free to add your perspectives too! I'm curious to hear from you all.

Etymology and Usage

‘Hijra’ in its meaning and usage amongst the cis is most similar to the word ‘naamard’ (NAH-murd). The ‘naa’ is prefixal, a negation akin to ‘non’, while ‘mard’ is the word for ‘man’. It is a way of unmanning a man, of calling him lacking in the essential quality of manhood, of labelling him, in spirit if not in body, impotent.

As such, you can see how it’s an implicitly third-sexing construction (even before you account for how these communities are explicitly third-sexed, denied the epistemic autonomy to be recognized as women and now third-sexed by law). When Nanda called them emasculated homosexuals, it was not far off from how Indian culture forcibly categorizes and marginalizes them.

Members of the community have told me about their frustration and anger at being referred to as such, even though the word has now become a term through which they organize the community and sometimes advocate for themselves, a political reality that does not inherently contradict their campaigns to be recognized as women, and allowed to self-ID as such. (Recall, the Indian government currently mandates legal third-sexing of the hijra: they must first obtain a “Trans Certificate” and be documented as a third sex before they initiate the process of being recognized as women—a process that is contingent on subjecting themselves to transmedicalist scrutiny and gatekeeping!)

Others, however, have pointed out to me that the term is undergoing a process of reclamation. The term ‘hijra’ has a certain degree of legibility in Indian society even as it is a pejorative with degendering and dehumanizing connotations. It is being reclaimed intracommunally, but also by allies who speak of them without the usual stigmatizing connotations that cis society has saddled the term with.

Even still, I have also been told that the manner in which cis and especially Western academics use the term in scholarship—and I’m quoting here—”makes me want to tear my skin out”. The fictions of “recognized gender role in Indian society” and “oppressed only after colonialism” are further simplifications and fabrications that obfuscate the role South Asian ruling-class collaborators eagerly petitioned for those colonial-era laws, and ignores such easily available empirical evidence as the Manusmriti mandating punishments for anyone who sleeps with—ugh—“eunuchs”.

Conclusion

In sum, I’d liken the use of the word “hijra” as analogous to the usage of “queer” in the 90s, as a slur in the contentious, contextual process of being reclaimed. As Aruvi put it to me on Bluesky:

We cannot allow cis people to dictate the discursive and epistemic terms of transfeminine culture. At the same time, the term “hijra” still carries with it heavy baggage due to South Asian transmisogyny as well as the academic misrepresentations and epistemic extractivism that Western scholarship has subjected South Asian transfeminized demographics to.

If you want to know how best to use the term, try to do so without third-sexing, and without promulgating fictive ideas of South Asian cultures being “gender-expansive” and “recognizing more than two genders”. Erasing the marginalization of the hijra is endemic to the way the term is used in the West, and that must absolutely be combatted.

On a final, personal note, I also wish to clearly state that I do not reject the label ‘hijra’ because I consider myself essentially different from them. Many Indian (usually upper-caste) trans women wish to distance themselves from the hijra, as though reproducing our society’s disgust for them will spare them from the same fate. That is not an attitude I share, or wish to normalize. The hijra—both those who affirmatively identify with the term, and those who wish to distance themselves from it—are my sisters.

I have simply not been granted the honor of being part of the communities and kin structures, and I do not wish to appropriate their struggles out of respect. Even still, their struggles are and will always be mine.

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

The banality of transphobia

I think one of the things that we have to reconcile, at any cost, is the shock of seeing trans lives take shape when subscribing to a feminist thought that - at best - forgot to account for trans folks. Cisfeminism has useful shorthand for how gendered oppression works, such as to say that makeup as it currently exists is controlled by powerful men who profit off inducing body image issues, which in shorthand becomes a very strong opposition to the idea that makeup bestows femininity. Expose such a person to 'a man' who does use makeup to present as more feminine than 'his' body 'allows', and they're obviously going to get a sense of revulsion towards this individual who seems to be appropriating femininity and simultaneously also participating in and advocating for one of the most murderous industries of modern capitalism.

This fails to account for the fact that the trans woman is here a victim of the same set of factors that are causing the oppression of the cis woman, which is that a majority of the world and its institutions do associate women with makeup and refuse to associate trans women as women without it, and it fails at this precisely because it considers the trans woman as staunchly non-woman. And so the trans woman seems to be standing in between the cis woman and the utopia of bra-burning.

This leads to a sort of 'logical' transphobia wherein feminist logic that never accounted for trans folks is used to justify the exclusion of trans folks from womanhood - one that can only be broken by a feminism that includes trans women as women at its very foundation. It's crucial to consider this idea that trans-exclusionary thought is merely a logical result of any feminism that doesn't explicitly recognise trans women as women, since it underpins the radicalisation of the TERF community.

British TERFs as far as I've seen them are a mix of clueless aunties like JK Rowling and Chimamanda Adichie who are convinced of their own erudition (of course I know what feminism is, I wrote a book on it!) that draws from systems of feminist thought that don't recognise trans women; malicious right wing astroturfing infiltration paid for by conservative Christian and alt-right groups (such as Heritage foundation, which has ties with the newly formed "LGB alliance" in UK); and bogus theorists who facilitate this infiltration and rewrite formerly implicitly exclusionary feminist theory into explicitly transphobic academic output.

I think it would be useful to recognise the difference between these entities, and furthermore useful to recognise the breaking point in politics of otherwise 'normal' folks who with a little bit of the right indoctrination turn rabidly transphobic. It would be useful to recognise the banality of this transphobia: just as to Arendt there was a banality to Eichmann following his superior's orders at a concentration camp. JKR is, to use Arendt’s words only insofar as the comparison holds, “terrifyingly normal.”

There's nothing novel or shocking about Adichie's transphobia; it is merely a reflection of how far the TERF indoctrination of UK's public thought has gone.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[MIRROR] Titillation and perversion: the cis lens of Super Deluxe

Posting a mirror of this: original at http://theworldofapu.com/super-deluxe-critical-analysis/

Super Deluxe (2019), directed by Thiagarajan Kumararaja, has been a polarizing film in my queer circle. To those convinced of its brilliance, it is nothing short of a cinematic revolution. However, to the rest of us, it is difficult even to describe how depraved the moral center of the movie is, surrounded as it is by an aura of big names lauding it as years ahead of its time. This becomes an especially difficult matter when the narrative of the film is praised for being trans-inclusive. Many see it as Tamil cinema’s big favour to transgender folks, which makes it that much harder to argue that the film is transphobic to its core.

Structured as a set of four seemingly disconnected storylines, which eventually converge in unexpected ways, Super Deluxe is a potpourri of things that sound like Really Cool Movie Ideas—shower thought after shower thought thrown at you, plot devices that may well have come from that one college friend obsessed with Quentin Tarantino. The cult success of Aaranya Kaandam (Kumararaja’s previous and first film) led to a breathless build-up around Super Deluxe, and that resulted in a movie so convinced of its own hype, that it never stopped to consider the fact that these Cool Movie Ideas may not fit coherently. The movie is always smugly convinced of its own brilliance, all the way from the titillating title sequence to the ending that featured a bizarre exposition (aliens give you cash! morality is relative!), revealing the film’s sheer contempt for the viewer’s intelligence. Leaving aside the gratuitous violence and the rampant transphobia, Super Deluxe is a drab movie at best.

To begin with, Super Deluxe is not kind to its cis women. It opens with Samantha playing an archetype of a modern woman that has plagued Kollywood since time immemorial. Her character, Vaembu, speaks about sex in a way that is reminiscent of a schoolboy’s fantasy, calling herself an ‘item’ by way of introduction. We see a neat correlation being drawn, between the sexual openness of the character and the trouble she is in. Later on in the movie, a weak attempt is made to subvert this portrayal, along the predictable lines of the How Many Partners Have You Had conversation. By that point, the plot seems to have lost any semblance of life. The less said about Leela, the better—Ramya Krishnan makes a brave attempt to authentically portray one of the most ham-fisted stereotypes of Sex Worker with a Heart of Gold I have seen yet from Mysskin (one of four writers credited on this movie).

However, the violence that registers most is the one that comes disguised as empowerment. The character of Shilpa, a trans woman, is played by actor and cis man Vijay Sethupathi. Shilpa’s story is the detailed recounting of every single way in which trans women can be humiliated. My favourite critical review of the filmmaking on display here comes from the blog The Seventh Art, where Srikanth Srinivasan notes that the camera and the soundtrack share the point of view of the aggressor time and again. We rarely see Shilpa’s plot from her own perspective; it is always the perspective of a condescending observer or a crying wife. One such instance of this voyeuristic framing and subsequent othering is the scene where Shilpa is shown draping a saree. She dresses herself in front of a mirror while her wife stands and watches, sobbing. The soundtrack is giggling out Maasi Maasam Aalana Ponnu, a song from the 1991 film Dharmadurai, mockingly dissonant from the context. The camera zooms into Shilpa smoothening her wig, and she has the slightest moment of genuine euphoria that she looks good for her walk. The camera, of course, makes fun of this vulnerability all along—titillating noises from the sex song still running, it switches over to the sobbing wife who says, “I don’t know what’s harder, having lived so long without a husband or having to live with a husband like this.” This is the point of view the camera wants you, the viewer, to have. It wants you to watch while ‘something like this’ gets humiliated. This is supposed to be the progressive portrayal of a trans woman in this movie, obsessed with her appearance, indifferent to her wife’s pain; a balding sex trafficker who dresses up while her wife watches.

Srikanth goes on to observe: “In the scene at the police station, the only point of view the audience is allowed to recognize is the sleazy cop’s. The cop, of course, is a caricature and the audience is made to feel morally superior to him, while not having anything to do with Shilpa beyond dispensing sympathy for her subhuman status. By making Shilpa the passive object of contempt, the film forestalls even the possibility of the audience’s identification with Shilpa that the casting of Vijay Sethupathi might have offered. There’s a special violence in the fact that the transference of identity that the film demands from its trans viewers for its other characters is not matched with a demand from its cis viewers towards Shilpa.”

It deserves to be said that it is profoundly unethical and transphobic to cast cisgender men to play trans women. Jen Richards put it across wonderfully in the Netflix documentary Disclosure (2020):

“Having cis men play trans women, in my mind, is a direct link to the violence against trans women. And in my mind, part of the reason that men end up killing trans women out of fear that other men will think that they’re gay for having been with trans women, is that the friends, the men whose judgement they fear of, only know trans women from media. And the people who are playing trans women are the men that they know. This doesn’t happen when a trans woman plays a trans woman.”

All the subplots share one thing in common: the setup is fantastically contrived with no aspersions to realism or believability, with the exception of sexual violence, which is gratuitous, uncomfortably real, and never-ending. Don’t get me wrong—I think there can be artistic value in making a viewer squirm in their seat, discomfited by sexual violence, especially if you’ve been a victim of it. However, to do so with no narrative significance and to follow it up by saying “Everything is Meaningless” is the kind of depravity that I could not stomach, in a movie that everyone seems to love. Ostensibly, there seems to be an uplifting and empowering message that is arrived at, but not through any meaningful transformation, or moral discourse, or even the triumph of good over evil. This is the thematic methodology of the movie: it first completely reinforces harmful stereotypes for the entirety of the plot, in excruciating detail, and then says, “I was just joking, a flyaway TV knocks out the sexual predator, isn’t life funny?”

The most egregious of these, to me, is the resolution of Shilpa’s narrative, when she comes back and speaks to her wife and son. “I didn’t think of you or your pain. I didn’t know that I would have a son who loved me and ask me why I left him,” she says.

Raasukutty and Jothi berate and gaslight this sobbing survivor of sexual assault, accusing her of being stone-hearted and plotting to leave her family. And then Raasukutty says reproachfully that although everyone else mocked her, he and his mother accepted Shilpa the way she was. “Did I or mother say a single word to you?” he asks. This is not true; Shilpa was thoroughly humiliated when she returned home, including by Jothi, who responds to her transition by alternating between shock, unveiled disgust, and mourning at lost masculinity. But coming from the mouth of precocious child Raasukutty, it is merely a reflection of cis-fragility that doesn’t even register they drove Shilpa away.

Shilpa sobs a little more. Raasukutty says, “I don’t care, be a man, be a woman, be whatever you want. Never leave us again.” The scene fades into black.

My blood boils.

How could this be the resolution? The movie features a trans woman being mocked in ways that feel like the camera is laughing at her, a trans woman being sexually assaulted, a trans woman who is told that expecting society to accept her is too much to ask, a trans woman who gets driven out of every place she wants to exist in, only for her to be told, “I don’t care who you are.”

“I don’t care who you are” is not acceptance. I might have forgiven it all if Raasukutty had instead said “Why did you leave me, mother?” But what we get instead is a return to square one: Shilpa being berated for not being a father, a father she never wanted to be.

Shilpa is never offered simple acknowledgement of her womanhood, or her personhood even. She is always treated as a thing, never a woman. She is seen as an aberration, something grotesque, and the progressive message seems to be that these grotesque things must be accepted for whatever they are. I keep going back to that scene of Shilpa draping a saree, and the awful cognitive dissonance of it. In the end Shilpa says, “As a woman, I understand what you’re going through.” The irony sends shivers down my spine. If the filmmaker had actually believed that, he would have made a very different movie.

There is a profound cis male perversion in the way Shilpa’s story is told. It takes a cis man to devise a plot where a trans woman takes her young child to a public bathroom and zips him up, in a pose that looks like she is fellating her own son. It takes a cis man to write a plot where a trans woman is a child trafficker who upon losing her child in the market, screams that she’s a sinner who transferred her sin to her son when she touched him. It takes a cis man to gaze so long and unblinkingly at the debasement of trans life, and intercut to jokes about porn. This isn’t progressive thought.

One of the most enduring and harmful transphobic stereotypes in existence is the idea that transgender (and other) alms-seekers are running begging and child trafficking rings. This is a popular idea with very little evidence: Sabina Yasmin Rahman calls it the mafia of middle-class convenience. Having noted that police have run multiple investigations in Delhi which failed to establish the existence of a begging mafia, she concludes that this idea of a begging mafia is perpetrated by popular culture and widely-held beliefs, but in reality is hugely exaggerated. Most beggars just live in debilitating poverty. This harmful myth is reinforced in this movie. And really, the more I recall this movie, the more shocked I am that anybody thinks this is progressive. This is what cis people think trans folks do.

In his article on trans characters in Indian cinema, film critic Baradwaj Rangan (who happens to be cis male) had said, “Had Super Deluxe not been a “mainstream” movie, had it played only in festivals to sympathetic and (dare I say) “evolved” audiences, there might have not been the fear that Shilpa is showing the transgender community in a bad light.” For what it’s worth, I’d like to make it clear that sex trafficking is not a realistic character flaw, and rape is not a humanizing portrayal. I leave it to the reader to ponder how utterly offensive this idea is, that a mainstream portrayal of transgender people should shy away from such esoteric things like human dignity.

Even within the Indian trans community, there are divergences in what is considered problematic within the movie. Some of the criticism leveled at it, such as that of transgender activist Grace Banu’s (in an interview to Vikatan; article in Tamil), has been regressive and homophobic, calling into question the logic of Shilpa transitioning as an adult or being attracted to her wife.

Transgender people of all gender identities have the right to choose when to undergo surgical changes, if at all they want to undergo them, and have the express right to fall in love with or have children with or live with people of any gender. One of the common effects of Hormone Replacement Therapy is infertility—there are plenty of folks within the trans community who live their lives precisely in the way that Grace dismisses as illogical. For a trans woman who wants to father children, the two options are to freeze her sperm before starting HRT (expensive and inaccessible) or have a child before starting HRT (which is what Shilpa has done). Grace’s unnecessary and bigoted detour into Shilpa’s bedroom provides no teeth to her critique, which is otherwise spot-on in terms of the movie bringing back the many indignities that the trans community has finally moved past.

Super Deluxe will have to bear the cross for perpetuating the violent lie that women like Shilpa are men like Vijay Sethupathi in makeup and a dress.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Memoriam

I wanted to edit the punctuation from something I wrote right after U Srinivas passed away.

There is something that music does to you that you can’t quite explain. One of the things that keeps reminding me of this fact is a song called “Raghuvamsa Sudha”, a light-hearted composition that a man who would later become one of my favourite musicians is particularly adept at playing. I still remember the day I first heard the song:

My father kept telling me that there was just something different about this song, something that he can’t explain, and that if I came with him to the concert that night, he’d show me. My 10-year-old self was frankly more interested in the new friend I’d just made around the block, whom I could play cricket with.

‘Come,’ said father, though. ‘It would be magical.’ My ears pricked up at hearing the word ‘magical’. Even at that age I knew one thing: my father never overestimated.

So I trudged along, and off we went in that noisy little moped of ours: mother, father and I. At the gate, the artist’s sister shakes our hand warmly, absolutely prohibits us from buying tickets, and whisks us off to the first row. Colour me impressed. I didn’t think father was a ‘big man’. I promptly ask mother, and she says, ‘Out here, he is. He’s been following this man’s career for more than twenty years. I think his record of not having missed a single Chennai concert of his, was broken a mere three years ago.’ Why had I never known this about my father before? And more importantly, why is this worth missing the cricket game?

I’ll be frank about this – the first hour of the concert was a dull affair. That’s what I thought, anyway. I was too young and too inexperienced and too illiterate in music to understand the true nuances that were hidden in what I was hearing. I, having finally given up any hope of cricket, was drifting off to sleep. I voiced this concern in no uncertain terms, to father, and to this day, I believe that was the only time annoying father did any good to me. Father sighed, and whispered to me that if I was patient, he could do something. And so, he tore off a small piece of paper, and wrote “Raghuvamsa Sudha” on it, discreetly walked backstage, and handed the chit over to the mridangam player during a break between songs.

And I could have sworn that I saw Mandolin U Srinivas give father the tiniest of winks as he read out what was on the paper.

Father came back, settled down, grabbed my hand tightly, and said, “Listen.”

I had no idea that this song, in Srinivas’s particular rendition, would become by stock response to whenever I’m asked the question of what I thought the greatest piece of instrumental music ever made, was. Not right then. But for some reason, and this still amazes me, even to this very moment when I’m writing this and the song is playing in the background, I couldn’t stop smiling. There was a deep sense of happiness emanating from somewhere within me, and as I looked, smile still plastered on my face, I saw that my expression was mirrored in my father’s face. He, too, was smiling; eyes half-closed and head bobbing to the beat.

And, his hands playing across the tiny fret-board of the electric mandolin, switching notes faster than the eye could comprehend, the same smile was mirrored on Shrinivas’s face as well. The ecstasy of art, manifested in a boyish grin of unbridled, unadulterated joy, complemented by those twinkling eyes of inimitable charm.

We were in a world of our own. He had taken us to this exquisite world that only he could conjure up. Just like the rings of smoke through the trees of Robert Plant’s thoughts, except there were no words. Just incredibly talented men and their music, a confluence of all things beautiful.

It was too good to last. The good things always are. The song came to an end, and while ten-year-old me would prioritize cricket over carnatic music in the days to come for quite a long time – too long, in hindsight – those ten minutes had lit a flame inside me. I wouldn’t come back to carnatic music until I turned 16, but somewhere down the line, I owe it to this man for having taught me in ten minutes what a beautiful world there was, that I hadn’t explored yet. A world where I stand at the entrance and hesitate.

I now bitterly resent not having gotten to hear the best of the legend while he was still alive: there will be cassettes, there will be mp3s, but the magic of that moment – the utter serenity of that smile, born out of the joy that only the creation of art could produce – is lost, forever.

The news of his death came as an utter shock to my father. When I saw the news, I called him up immediately, and he said he was going to go to ‘Mandolin’s house to pay his respects.

To father, he was always ‘Mandolin’. He always kept saying that it is a great honour that an instrument is known after a man. That a random village in Andhra Pradesh, and a random instrument with roots in medieval Italy, were brought to prominence due to the sheer genius of a man who could move rocks to tears.

To me, he would always be the man who had a friendly smile and a respectful greeting to people whom another in his place would have considered ‘simply fans’.

0 notes

Text

5 reasons why you probably shouldn't say 'womxn'

“1. I say so. Not because I'm special or anything, but this word claims to cater to me and include me and I just don't vibe with that nonsense. I'm not a woman and I'm not a woman with one character substituted out. So if you're going down to reason 2, you're telling me I hear you and I know better than you how to include you, in which case, here's some more reasons:

2. It has its origins in trans-exclusionary feminism. Womxn is understood to have been coined in response to "womyn," a solid TERF construction which was to signify that they hated men - and trans women - so much so that they didn't want "men" to be a substring of the word denoting them. Womxn is supposed to fix this - I'm not sure how or why. The word does not have any coherent transfeminist history that I can see, and I have been searching for a while. If you can find an authoritative source for the origin of 'womxn' that contradicts this, please contact me. Mark Peters in The Boston Globe writes that ““Womxn” is one of a few similar lexical and social phenomena, including the adoption of “x” in naming LGBTQ and non-gender-binary people.” I think that’s shoddy. Unlike ‘womyn’ which has a coherent traceable history, going back to Wolf Creek Womyn’s festival, womxn has no such known origin point. Some trace it to the 70s without ever demonstrating this trace - please @ me politely or otherwise if you find that I haven’t done my research and there is a coherent source and etymology for womxn. If you construct a term where the founding logic is "let's take out all traces of 'man' from this word so as to exclude trans women who we believe really are men," then in my book it doesn't get subverted by changing its spelling. The purpose of modifying the word "woman" was trans-exclusionary in the case of 'womyn' and I fail to see how it ceases to be trans-exclusionary for 'womxn.'

3. There cannot be one term including everything 'womxn' claims to include and excluding everything it claims to exclude. I posit that any sentence that demands its usage is carelessly composed. Womxn is intended to lump together cis women, trans men, nonbinary folks, and exclude cisgender drag queens, cis men, and other AMAB castaways of the queer community. As far as I can see, the criterion for being a womxn, far from being the all-encompassing all-progressive umbrella, turns out to be far too reliant on gender assigned at birth. That's shady as hell. I personally don't know any trans man that wants to be called a womxn; and I abhor the term, of course. I think really it just reeks of cis-feminism trying to reduce all gendered violence to a conception of sexism where only cis men can be perpetrators and cis women are the highest hierarchy of victim to the extent that the word "woman" forms the root of this word to represent all marginalised gender identities. As a nonbinary person I reject the cis-centeredness of this term, and I also reject my inclusion within it.

4. It is a prime symptom of the NGO-industrial complex trying to worm its way into progressive communities by appropriating the language while not adopting any principles of social justice. Every woke organisation is probably sending out internal memos to search-replace instances of "women" with instances of "womxn." Womxn is considered to be the more 'woke' version of the term, used to signal a certain progressive credential. It is best to be cautious of such usage. As an approach to inclusion and liberation and progressiveness it is highly suspicious, one that involves reinventing language not for linguistic or community purposes but to cover up exclusion and to add clout value to sentences to make them look aesthetically revolutionary.

5. An umbrella term already exists to signify nonconformity to the assigned gender at birth, to denote many of those who are marginalised due to gender identity, expression, and experience differing from gender assigned at birth, and differentiating us from cis folks: transgender. Unlike 'womxn,' transgender denotes an umbrella of people with actual shared experiences and identities and communities. While ostensibly claiming to be inclusive, "womxn" is predicated on the cis gender binary and focuses inordinately assigned gender at birth.

Aside from that, reading the work of Anbu Esvi reminded me of how cis queer spaces had somehow made me feel like "transgender" is a dirty word, a word that's not enough, that I had to use "trans*" or other alternatives to replace an 'outdated' term, and how that is sheer folly.

They write -

"In my personal journey, I have now arrived at happiness with ‘transgender person’. I have arrived here after rejecting queer and only trans* that I used to earlier uphold, as part of my solidarity with some queer feminist spaces. I am happy with transgender asexual person because I have now spent some amount of time engaging with terminologies and their histories and political implications. Unlike queer (which was ‘reclaimed’/’subverted’ from a slur ... and still has little to no space for asexual expression), the origins of transgender terminologies are taken by the community ... however complicated its meanings and understanding of sex and gender differences."

and I find myself heartily agreeing. I have an exhilaration for "transgender" as a term to describe myself and an umbrella to identify under because of the power it holds. The history it holds. The amount of progress that has been achieved under its name. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P Johnson aren't "womxn." They identified as drag queens, an identity that exists under the transgender umbrella. They are transgender. Say the word.

(Esvi's citations are in their article. My only citation is their article. Please read it: https://medium.com/@esvi.kot9/no-outlaws-in-the-gender-galaxy-a-trans-feminist-review-discussion-fda47fd478dc )

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It has been so long since I wrote something that Google keep actually implemented dark mode. #poetry https://www.instagram.com/p/B0zAHb-pKGM/?igshid=mshkohvor49j

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

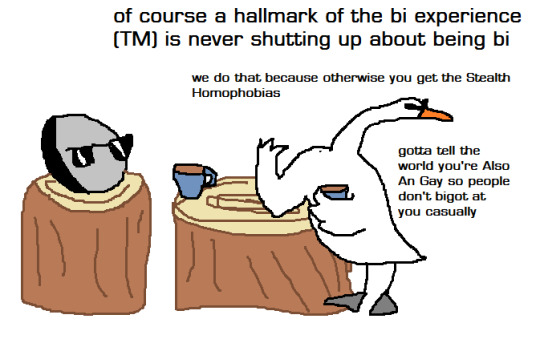

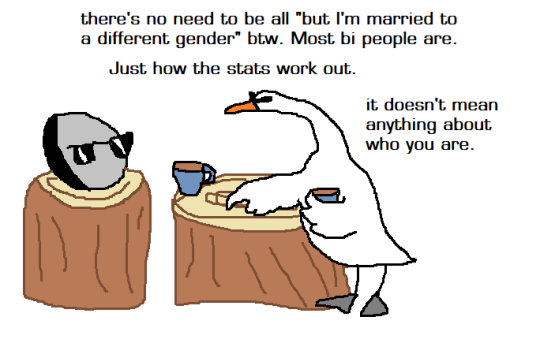

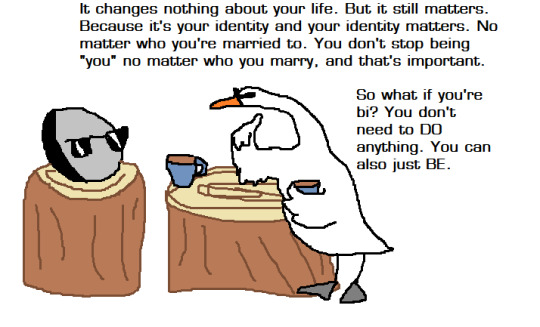

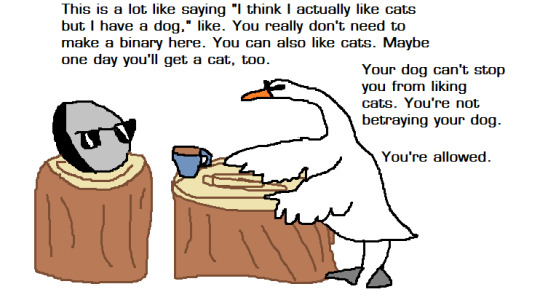

over time i have become the bisexuality-affirmer for my friends and most of what i end up saying is some subset of this post.

So I think I might be bi? But if I am it changes almost nothing about my life because I am happily and monogamously married. But if it doesn't really matter, why do I have so many feelings about it???? Anyways, I am asking you because it seems like there is a 50/50 chance of a delightful and pithy answer or a picture of a bird as an answer.

164K notes

·

View notes

Text

erasure:

Speaking a little from where I used to be - which is on the absolute other side of this spectrum.

I think that finding the identity of 'tambrahm' trendy is casteist, yes, subtly, but it is more importantly ignorant. I'll get to how it is casteist in a minute, but how it's ignorant is way more important.

It is ignorant because it is ahistoric. The way caste proliferates itself in urban settings is by an erasure of history. It is ignorant because it is limited in scope. The way caste proliferates itself is by making itself a bad, taboo term, and in settings such as caste-homogeneous gated communities -- or really, the bungalows of Alwarpet -- is by being invisible. A small section of the upper castes have used their privilege to build microcosms of society where caste does not need to exist, where it has no relevance anymore, where as long as you're fortunate enough to be born within this microcosm, caste doesn't matter. And true to the intended aim of creating a casteless society, this microcosm has distanced itself from caste as much as it can, and true to the utopia that it envisions, children in this microcosm are brought up casteless, turning noses up at casteist practices their grandfathers used to follow.

This microcosm is bound to come into contact with the outside world, of course, and the places it comes into contact are colleges, government offices, and the like, where reservation is a reality. And when your entire metaphysical framework, your entire sphere of knowledge, what your parents taught you, what your schools taught you, is that caste is dead and we left those dark days long back, here is a government office that is trying to "pretend" that caste exists. When you erase the entire history of caste, then it looks to an innocent observer as though a very small portion of the population, some of them economically poor, are being scapegoated as oppressors in a long-forgotten system.

This is where the idea of neo-tambrahm-pride is born. When the world is seemingly out to get you, trying to suppress your merit by reservations, then it seems natural to go back to your community and take pride in it. On the surface of it, tambrahms seem very cultured. Highly culturally nuanced (look how mathematically sound carnatic music is! wow!), rational, english-speaking, progressive (at least until the rise of Hindutva lol where's the community's progressive values now huh), deserving of a very funny sporting moniker that Chepauk Stadium has garnered over the ages, that of a "knowledgeable cricket crowd" that applauds a good cover drive even when Pakistani players score it (?). In this ahistoric vaccuum, these are all things to be proud of, even more so since all these reservations are trying to push us away.

That's why there's such a massive push-back to the "smash brahminical patriarchy."* God, I used to be one of them because this ahistoric gated community is very very VERY self-sufficient. Like one of those OMR ready-to-occupy retirement homes with every amenity existing within its boundaries. It is possible to live, love, procreate, work, die, all within this ahistoric vacuum.

So, what gives?

What gives, of course, is that none of this is true and all of this is constructed. constructed specifically at the expense of lower caste and avarna peoples. All the things that tambrahms are proud about is not unique to tambrahms through merit, but through exclusion.

The "normal" is ideological. The "apolitical" is deeply political. The false calm in the eye of the storm is deliberately politically constructed so as to induct those with enough privilege for caste not to matter, into its popular falsehood that caste indeed doesn't matter. It is a framework that tells you not to think too hard about these things.

You "don't see caste" until you do. Caste is everywhere. It is in the food you eat, in the toilet that someone else cleans for you. It is in the place you die and the people who cremate you, and the things that are said when you are cremated.

Wake up from the vacuum. Ask "where can I learn about caste?" instead of buying wholesale the readymade convenient excuses.

*there's also another reason why: most people who emigrate to the united states are brahmins (guess why! is the answer 'merit'? because I've got a doozy for y'all), there's literally no plurality of voices in this whole fiasco. The ones who reacted to it are brahmins and the news channels, of course, want to focus on those.

After writing this, I came across this article that expounds further upon this idea of “general category” and castelessness, and it is worth a hundred reads: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1R61dlAMm8300oIY1JIaOeW56hwfREo71/view?fbclid=IwAR0OYZbkw_qFDHXmf1v1C0zOAYcQmvuJ14sTr3LtkhK8oJvzi18EiAaubaU

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calcutta, or: How I learnt to stop worrying and embrace the chaos.

Chaos is steeped into the soul of the roads of Calcutta, and it doesn’t just stop at the roads: thundering at an ear-splitting sixty kilometres an hour on a six hundred metre bylane gives a measly advantage of thirty six seconds over driving at a far less terrifying thirty, but it is the principle of it that counts to the honking motorists. I don’t suppose that it would really distract you if you’re absorbed enough in discussing what effects youth (that catch-all term) walking about casually smoking joints would have on the aesthetic value of high-end low-density housing areas with your world-weary local companion guiding you by the arm… But it is surprising what transgressions you get used to in three days.

And what transgressions they are— couples wrapped around each other in broad daylight on benches at the Victoria Memorial with caretakers in Army uniforms sitting in their caddies with a practised disinterest for anything that doesn’t litter; busybodies in Sudder street shouting after you that rooms are available by the hour; standing ovations for classical musicians two hours past midnight with screamed requests for encores of abhangs; loudspeakers broadcasting the thousand names of Ganesha at three AM in the spirit of celebrating Saraswati Pujo three days after Saraswati Pujo; tame jackals at the Tollygunge club avoiding lazy golfers and ladies ordering masala dosa with the masala on the side; the city is nostalgia, all modernity is only a slave to the nostalgia that runs the city.

Of all the curiosities, though, the ones that most struck me were the quirks of transit. Most Indian transit systems make the fatal flaw of ignoring operational costs at the time of setup. This means that they would inevitably degenerate over time, and the powers that be would sooner build flyovers than sanction frequency reinforcements, but such is life. But funding apathy doesn’t hamper the spirit of the quintessential conductor-kaku to pack the bus to the brim as much as humanly possible, and then a little bit more, screaming the stops in his line for anybody who is listening.

Taking public transport in Calcutta is cheaper than the wildest imagination, but the real trouble is getting conductor-kaku to notice you. You could very simply contrast the work ethics of Chennai and Kolkata just by looking at the bus conductors: in Chennai, the conductor is in a mad rush to issue tickets as though his life depended on it. On occasion, the Chennai conductor also instructs the driver to pull over and wait until he is done issuing tickets; but the Kolkata conductor will have none of it. He will do all manners of things before he gets to the part where he issues tickets: chat about life with the driver, look out the window and enjoy the scenery, shout out the places the bus will stop at, Howrah, Howrah, Howrah, won’t you go to Howrah, kind sir, and then he gets to surveying the inside of the bus for faces that haven’t yet bought tickets that are printed on used paper (you could find little snatches of whatever purpose the bits of paper served in their last life).

At any rate, here’s the multimodal chain that I took last Saturday to get back home:

Cycle Rickshaw from Lake Gardens to the intersection of Sultan Alam Road and SP Mukherjee Road,

The metro from Rabindra Sarobar to Maidan,

Walk along Maidan, enter Victoria Memorial at the North Gate and exit it at the South Gate, walk back around till we saw tram tracks,

Tram from Maidan to Esplanade,

Walk along Chowringhee road to the intersection of Park Street and Chowringhee road,

Bus from Park Street to Howrah Railway Station,

Coromandel Express from Howrah Junction (HWH) to Chennai Central (MAA),

Walk along the newly renovated Central Station subway (shops are now banned inside the subway) to Park station,

Beach-Tambaram local from Park to Kodambakkam.

Some pictures and tickets attached.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#poetry #poetsofinstagram #beach #sea #water i guess...

0 notes

Photo

It has been a decent weekend. #poetry #poetsofinstagram #spilledink #bangalore #bookstores #books (at Blossom Book House)

0 notes

Photo

:) #poetry #instapoetry #spilledink #rain #highway

0 notes

Photo

A lot of pokémon are based off of animals in our world, but Heracross is essentially a 4′11″ carbon copy of the Japanese Rhino Beetle.

Rhino beetles can lift approximately 800x their own weight, although some of Heracross’ other entries specifically say he can only throw 100x his own weight.

Regardless, studies have shown that the shape of a beetles’ horn affects its fighting style, much like fighting with a sword is different from fighting with a battle-axe. With that in mind, let’s compare Heracross to its mega form:

As you can see, Mega Hercross has two large, curved horns, like a real life Hercules Beetle. If it looks like a pincer, its for good reason. Mega Heracross pinches and grabs his enemy in a full-body hold, and tosses them around. Normal Heracross’ horn on the other hand resembles more of a pitchfork. Heracross then finds advantage by lodging his horn underneath opponents, to gain leverage and shove them around. This National Geographic Article goes into more detail on more kinds of beetles if you are interested!

Heracross fights by digging his horn under his opponent, and lifts and twists to throw their opponent around. When it mega evolves, its fighting strategy changes. It now grabs its enemies with its pincer-like horns to physically throw them around.

The pokédex also tells us that Heracross can topple trees with his horn, so let’s examine that. As you might imagine, toppling a tree has less to do with the size of the tree and more to do with its root system. The more extensive the root system, the harder the tree will be to uproot. Luckily, Heracross’ horn is a perfect gardening tool for getting in the roots. Mega Heracross, on the other hand, would not be as effective.

Imagine with me, if you will, Heracross digging under a massive trunk with his horn, and using it as a lever to uproot a tree. A lever, as you might know, is a simple machine which can help reduce the force needed to get something done. For example, you might not be able to pry a cap off of a bottle yourself, but a bottle opener will easily do the trick.

A lever uses a rotational force called torque about a center pivot point called a fulcrum to manipulate force.

Let’s say that between the force of the roots and the tree itself, the tree needs 100x Heracross’ weight (540 kg) to be uprooted. This is a fairly small tree to be honest, but that’s okay. Heracross’ horn is the lever here, which is about 0.8 meters long. The fulcrum I am going to estimate as being near the end of the pitchfork, or 0.3 meters from the tip. Using this equation:

Heracross must lift a force of 324 kg (715 lbs) to uproot a tree that is effectively 100x more massive than he is.

For the record, if Heracross could lift a tree like this 850x more massive than he is (like the Hercules Beetle can), he would have to exert a force of over 60,000 pounds. Not bad for a little guy.

Requested by hanari-san

615 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I don't know don't ask me. #poetry I guess, #poetsofinstagram for sure, #instapoem #memories #nostalgia #tags

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Long blog posts about Pokemon inspirations are why I still use Tumblr

Requested by @robo-dactyl and @electronicallyinclined

Yesterday we covered Grubbin and Charjabug, so it is only natural that we complete the family today with Vikavolt. Vikavolt is a stag beetle, specifically based on a member of the genus Cyclommatus, known for their long mandibles and metallic bodies.

A stag beetle’s large mandibles are used as weapons. They fight over food, territory, and mates. When they wrestle, they pick each other up with their pincers to flip their opponent vulnerably onto the back, or off the branch altogether.

Vikavolt is…different. Its mandibles are definitely used as a weapon, except they are a projectile weapon. An electric railgun.

A railgun is a projectile launcher that is made of two conducting arms, called rails. Vikavolt’s mandibles are the rails. Electric current flows inwards through one rail and outwards through the other, creating a “U” shape of current. Since moving electricity creates a magnetic field, a strong one grows in between the two rails and this magnetic field is a pushing force for whatever conductive material you want to shoot out. In Vikavolt’s case above, it shoots out a plasma ball. Plasma railguns are typically require a vacuum to be efficient, but the principal is still the same.

Railguns are able to fire projectiles with huge speeds up to 2,500 m/s (8,200 ft/s), which is about 7 times the speed of sound.

Vikavolt’s mandibles act as a railgun. Electric energy flows inwards in one mandible, and outwards in the other. This creates a strong magnetic field in the center, which propels projectiles at high speeds towards its enemies.

709 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Long blog posts about Pokemon inspirations are why I still use Tumblr

Requested by @robo-dactyl and @electronicallyinclined

Yesterday we covered Grubbin and Charjabug, so it is only natural that we complete the family today with Vikavolt. Vikavolt is a stag beetle, specifically based on a member of the genus Cyclommatus, known for their long mandibles and metallic bodies.

A stag beetle’s large mandibles are used as weapons. They fight over food, territory, and mates. When they wrestle, they pick each other up with their pincers to flip their opponent vulnerably onto the back, or off the branch altogether.

Vikavolt is…different. Its mandibles are definitely used as a weapon, except they are a projectile weapon. An electric railgun.

A railgun is a projectile launcher that is made of two conducting arms, called rails. Vikavolt’s mandibles are the rails. Electric current flows inwards through one rail and outwards through the other, creating a “U” shape of current. Since moving electricity creates a magnetic field, a strong one grows in between the two rails and this magnetic field is a pushing force for whatever conductive material you want to shoot out. In Vikavolt’s case above, it shoots out a plasma ball. Plasma railguns are typically require a vacuum to be efficient, but the principal is still the same.

Railguns are able to fire projectiles with huge speeds up to 2,500 m/s (8,200 ft/s), which is about 7 times the speed of sound.

Vikavolt’s mandibles act as a railgun. Electric energy flows inwards in one mandible, and outwards in the other. This creates a strong magnetic field in the center, which propels projectiles at high speeds towards its enemies.

709 notes

·

View notes