Blog for timelines, character analysis, theories, worldbuilding, etc.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Was thinking about Ford and like... He's a character that's defined by being strange, being Othered and ostracized, and how what's different is wrong (and often underneath, dangerous). And because of that he's so deeply lonely when Stan leaves, and so much of his life is trying to be accepted or to prove his worth to be loved/accepted then through scientific and academic renown. And what's so interesting is he tries to do it through strangeness. His Grand Unified Theory of Weirdness. He's going to prove his worth, he's going to be accepted through proving the worth of Weirdness and Strange phenomena to light... like the portal was never just about being 'famous'. Ford saw himself in his work, and that's why he reacts so strongly when Fiddleford leaves the project because Fiddlefords not just rejecting the portal, Fiddleford's rejecting Ford. Ford's work in gravity falls, on the portal is more than a ticket to proving his selfworth it's also Ford proving he himself matters in a way, you know? And beneath that is a desire to be accepted, to be loved for who you are, because Ford could never not be something Othered, but he could perhaps prove that the Strange, the Other--who he himself is--is important. And I mean like, Bill also fits in this because he came to Ford, he gave Ford that acceptance and importance, but only between them, and he also was able to lean into Ford's desire for wider acceptance by giving Ford tools to create this 'proof' of the strange, to prove Ford importance, through the portal...

Only for everything to fall apart. Both Fiddleford and Bill were unable to accept Ford for who he is, what Ford had always desired and somewhat had with the two of them. This violation of autonomy done by Fiddleford with the memory gun and Bill becoming violent after Ford refuses to engage with him after Bill's cards are shown... And the work Ford's done to prove himself as important, to become important is all just a shill for Bill's world domination plans. Like. Fuck, man. The emotions you must have there. The horror and rejection and also what does this say about you? That the work you did to prove yourself important is so indelibly intertwined with this demon? With something that intends harm? The monstrosity, the danger within the Other, within the Strange, and how that applies to you? Isn't this the opposite of what you were trying to prove, to show you are something worthwhile, instead of something strange and wrong and worst of all, dangerous?

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Bill projects onto Mabel sometimes, especially in Sock Opera and Weirdmageddon. He sees her as a little selfish, a little chaotic, and a lot more fun than Dipper (at least, in the way that Bill defines fun), and that’s clearly all stuff that he represents too.

But I’d argue he also sees himself in Mabel’s reluctance to grow up. It’s true that Bill has been around longer than humans can even wrap their minds around, but he’s still immature. He still throws tantrums when he doesn’t get his way — he’s just a big, selfish kid himself, and he doesn’t want to grow up either.

And he’s not entirely wrong when he identifies these similarities in Mabel, but he vastly overestimates the strength of her selfish tendencies while underestimating the strength of her caring nature and her loyalty to her family.

We see it in Sock Opera, where Bill expects her to hand over the Journal rather than make a sacrifice for Dipper’s sake, and we see it again in Weirdmageddon, when Bill has complete faith that Mabeland will prove inescapable — but unlike Bill, Mabel is a good person who loves her family, and both times Bill’s plans are foiled. (Meanwhile, we know Bill had a horrible relationship with his own family, and I think that plays into how he expects Mabel to behave — hence the term “projection” feeling especially apt.)

[ID: The first image shows Bill Cipher floating in a street in Gravity Falls during Weirdmageddon as he says: “This party never stops!” The second image shows Mabel sitting at her brightly colored office desk in Mabeland, gesturing enthusiastically to Dipper, Soos, and Wendy as she says: “Here the sun shines all day, the party never ends…” /end ID.]

Bill is a villain who has never grown up in a show that’s about growing up, and that seems like a very deliberate choice. He offers Mabel an escape from reality that he sees as so tempting, so irresistible, that he thinks it would take “a will of titanium” to overcome, and he completely brushes off the possibility that the Pines might break out of it.

Maybe that’s because Bill knows that an idealistic world like Mabeland, full of nonstop partying and free from any obligation to grow up, is exactly the type of trap that would work on him.

(Some sources/quotes that first sent me down this line of thinking below the cut.)

Keep reading

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mabel Pines: Authority, Identity, and Emotional Growth

Mabel Pines emerges as one of the most vibrant characters, a sparkling counterpoint to her twin brother Dipper's analytical tendencies in Gravity Falls. With her colorful sweaters and boundless optimism, Mabel navigates the supernatural mysteries of Gravity Falls while simultaneously facing the challenges of growing up. By examining her relationships with authority figures, particularly her great uncles Stan and Ford, we can uncover crucial insights into her personality, values, and emotional development. The stark contrast between how Mabel and Dipper interact with these authority figures reveals fundamental aspects of Mabel's character: her emotional intelligence, resistance to change, need for validation, and complex journey toward maturity.

Mabel's Essential Character: Beyond the Sweaters

Before analyzing Mabel's relationships with authority figures, we must establish her core personality traits. Series creator Alex Hirsch clarifies a common misconception: "Mabel's not stupid. She's a ham! There's a big difference. Mabel's love of goofing off is a natural force of her personality, but she can still understand when people she cares about need help or are in danger." This distinction proves crucial—Mabel's playfulness doesn't equate to obliviousness or lack of intelligence.

Among the Pines family, Mabel possesses "the biggest heart," typically being the first one to try to make someone feel better or try to befriend them. Her creativity extends beyond her artistic pursuits into problem-solving, where she employs her own creative impulses and ideas to overcome challenges, such as spraying Bill's eye with spray paint or rearranging the clay monster. Her optimism balances Dipper's seriousness, reminding him not to grow up too fast and to have fun.

However, Mabel demonstrates less positive traits as well. She can come off as selfish when focused on fun, sometimes forgetting that just because she's having fun doesn't mean everyone else is. This self-centeredness manifests in her "stubbornly nosy" tendency to involve herself in others' business, particularly in matchmaking scenarios. Most significantly, she harbors a deep fear of growing up and resists change, a trait that defines her character arc and her relationships with authority figures.

Physically, Mabel expresses herself through "very active" body language that is very expressive and exaggerated, incorporating "twirls," "finger guns," and animated arm movements. This expressiveness reflects her emotional openness—Mabel wears her heart on her sleeve, contrasting sharply with her great uncles' more guarded natures.

Mabel and Grunkle Stan: Emotional Kinship

Mabel's relationship with her Grunkle Stan reveals much about how she views and relates to authority. Unlike Dipper, who often challenges Stan's schemes on moral or logical grounds, Mabel connects with Stan emotionally. She is typically the one who brings out the softer side of Stan and isn't afraid to call him out for neglecting to be polite like saying a simple 'please' or 'thank you'. This suggests a comfortable familiarity that allows her to gently challenge his rougher edges without creating serious conflict.

The relationship benefits both parties. Stan's gruffness doesn't intimidate Mabel, and she helps him access his more vulnerable side. They share a playful dynamic where they often share teasing jokes about Dipper, creating a bond that sometimes excludes Dipper. This alliance provides Mabel with validation from an authority figure without requiring her to fundamentally change who she is.

Some critics suggest that "Stan favored Mabel more than Dipper as well, and made him do all the potentially dangerous jobs around the house." While this perspective may be somewhat biased, it does indicate that Stan's relationship with his great-niece differs significantly from his relationship with his great-nephew. Where Dipper must often prove himself to Stan through trials, Mabel receives affection more freely.

An illuminating example of their dynamic appears when Stan explains his approach to toughening up Dipper. After recounting his own childhood boxing lessons, Stan reveals: "That's why I'm hard on Dipper to toughen him up so when the world fights he fights back." Notably, Stan doesn't apply this same "toughening up" philosophy to Mabel, suggesting he perceives and treats the twins differently based on their personalities and perceived needs.

This relationship reveals Mabel's need for emotional security and validation. She gravitates toward the authority figure who provides unconditional acceptance, allowing her to maintain her identity without significant challenge. Stan creates a space where Mabel can be herself without judgment—crucial for a character who fears growing up and changing.

Mabel and Ford: Fear and Resistance

Mabel's relationship with Ford presents a striking contrast to her connection with Stan. Where Stan's authority style embraces Mabel's personality, Ford's more academic approach aligns naturally with Dipper's interests and temperament. This creates tension for Mabel, who sees Ford as potentially separating her from her twin.

This fear culminates in "Dipper and Mabel vs. the Future," where Ford asks Dipper to become his apprentice. Mabel's reaction reveals her deepest insecurities—when faced with the possibility of Dipper staying in Gravity Falls while she returns home alone, she makes a catastrophic decision, accidentally making a deal with YOU KNOW WHO. This crisis demonstrates how Mabel's relationship with Ford is defined not by what they share but by her fear of what his influence might cost her.

When Dipper tries to explain Ford's offer, Mabel repeatedly says "you can totally go with Grunkle Ford to save the world or whatever" while noting that she'll be doing "birthday junk all week". The contrast between world-saving and "birthday junk" highlights the gap Mabel perceives between Ford's serious world and her desire for fun and celebration. When faced with difficult conversations about this future separation, she didn't want to hear what was being said to her, demonstrating her immature coping mechanisms when confronted with unwelcome change.

Ford himself may contribute to this tension by "projecting" onto Dipper and Mabel's relationship, possibly suggesting that "

Mabel is holding him back. This mirrors Ford's own complex relationship with his twin brother Stan, creating a parallel between the two sets of twins that Mabel intuitively resists.

Mabel's difficult relationship with Ford reveals her fear of abandonment, her resistance to growing up, and her anxiety about Dipper developing in ways that might separate him from her. Where Stan represents comfortable acceptance, Ford represents challenging growth that might threaten her sense of security and identity.

Contrasting Approaches to Authority: Dipper vs. Mabel

The stark difference in how the twins relate to Stan and Ford illuminates their contrasting approaches to authority more broadly. Dipper seeks intellectual validation and mentorship, looking to authority figures (particularly Ford) to guide his development. He looks up to him so much that he's probably going to glom on to whatever he says. This makes him receptive to Ford's academic, mission-oriented guidance but sometimes puts him at odds with Stan's less conventional authority style.

Mabel, conversely, seeks emotional validation and acceptance. She thrives under Stan's more permissive, affection-based authority but feels threatened by Ford's more structured approach. Where Dipper sees growth opportunities in Ford's challenges, Mabel sees potential loss and separation.

This difference reflects their fundamental personalities. Dipper is future-oriented, goal-directed, and driven by curiosity. Mabel lives more in the present, values emotional connections over intellectual pursuits, and prioritizes maintaining what she has over risking change. Neither approach is inherently superior, but they create different trajectories for the twins as they navigate the transition from childhood to adolescence.

Authority and Identity Formation: Mabel's Emotional Journey

Mabel's interactions with Stan and Ford reveal much about her internal struggle with identity formation. Stan represents the comfort of childhood unconditional acceptance, fun without consequences, and freedom from change. Ford represents the challenges of growing up increased responsibilities, intellectual demands, and the painful necessity of separation.

Mabel's preference for Stan's authority style and resistance to Ford's influence demonstrate her fear of growing up. She wants to preserve her bond with Dipper and maintain her carefree approach to life, both of which seem threatened by Ford's more serious perspective.

This resistance isn't simply selfishness it reflects Mabel's genuine anxiety about losing what matters most to her: her relationship with Dipper, her freedom to express herself, and her joyful approach to life. While critics argue that "she didn't get developed properly, and actually regressed towards the end of the series," her struggle with growing up represents a realistic challenge that many early adolescents face.

Conclusion: The Authority Mirror

Mabel's interactions with authority figures provide a window into her complex development. Through her comfortable relationship with Stan, we see her strengths her emotional intelligence, her ability to bring out others' best qualities, and her commitment to joy even in difficult circumstances. Through her tense relationship with Ford, we witness her struggles with her fear of change, her occasional selfishness when threatened, and her immature coping mechanisms.

These relationships reveal Mabel as neither simply selfish nor simply sweet she is a mixture of admirable qualities and realistic flaws. Her resistance to Ford stems not from mere stubbornness but from a deeper fear that growing up might mean losing what matters most. Her embrace of Stan reflects not just a desire for indulgence but a genuine connection with his more emotional approach to life.

Understanding Mabel through her authority relationships allows us to see beyond reductive interpretations. She is neither the underdeveloped character that critics describe nor a flawless beacon of positivity. She is a young person navigating the difficult terrain between childhood and adolescence, sometimes stumbling but always maintaining her essential Mabel-ness, her creativity, expressiveness, and big heart.

Her journey reminds us that there are multiple paths to maturity. The tension between Mabel's approach and Dipper's reflected in their different relationships with Stan and Ford illustrates this diversity of development. Neither twin is "right" or "wrong" in how they relate to authority, but each reveals different aspects of the complex process of growing up and finding one's place in the world.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

watching people fight over how canon the book of bill is while completely mischaracterising bill is such a strange experience

yes he’s a liar. yes he’s a manipulator. yes he is so distant from any semblance of humanity that he is literally incapable of regret, empathy or remorse, or at least admitting to himself that he feels it.

but he’s also TERRIBLE at it. he’s a total loser. he’s objectively bad at the one task he’s spent lifetimes on. throughout history he attempts to sweet talk many, many different figures into building his portal and it rarely goes down well. multiple civilisations are aware of his existence and the sole reason we know this is because they hated him and invented their own ways of keeping him out. he has been consistently rejected by humanity at every turn, only coming close to completing his goal when he literally possessed a dead man and formed a cult.

ford is the only person who really, truly fell for the act. not just that, but bill didn’t even have to pretend to physically be someone else to get him hooked. ford took him as he was.

all this to say, bill is absolutely a grifter who will say anything to get what he wants, which means a lot of BOB is just sweet talk, carrot and stick, he’s just saying what the reader wants to hear. but that’s not the important bit.

bill is a liar but he wraps the truth up in layers of misdirection, doublespeak and lies. a monster really did destroy his homeworld. him and ford really were going to change the world. he even addresses this in the book, he lies until it becomes the truth. a lot of bill’s characterisation is shown in the gaps between his lies, it’s all in the fault lines, in a similar way to stan. he’s a very meta character, but ultimately he’s still a character and he still behaves in ways that are designed to convey meanings to the audience.

of course he’s lying in the book of bill, but he’s also telling the truth, in addition to bits of info from other sources that he is unable to edit like the theraprism section. it’s fun to have a character who lies a lot, but it would be a pointless exercise to have an entire book be non-canon and false, especially when we get much more interesting character work from the parts where he runs out of lies and his only options are desperate truths.

anyway. people wanting to enjoy canon info in a canon book isn’t just them “being easily manipulated” or stupid, and you aren’t a better fan for not believing it

452 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not to defend the overall narrative surrounding house-elves, but probably the #1 reason I'm so sympathetic to Regulus is that he didn't make Kreacher drink the potion.

House-elves are the lowest of the low in Wizarding society, and virtually nobody questions or objects to the way that they're treated. The narrative wants us to believe the Blacks were kind to Kreacher, but what we're actually shown says otherwise: his living conditions leave a lot to be desired, he harms himself as punishment for disobedience or failure, and then of course there's the whole beheading thing. I don't blame Regulus for any of this, because he was a child and would've had no say in it. But I think it's important to understand, where house-elves are concerned, his family wasn't that different from the Malfoys.

And yet, while I know some people do interpret his actions in a very uncharitable way (he was just upset that his property was damaged, etc.), I think there are signs that there was more to it than that. Kreacher himself states that "Master Regulus always liked Kreacher" (DH ch. 10), which implies that from an early age he showed him kindness and affection. Regulus described Kreacher's task for Voldemort as an honor for both of them; how many wizards would even consider whether or not something was an honor for their house-elf? And, while it's suggested he loaned Kreacher to Voldemort willingly, I don't think it's a coincidence that he ordered him to come home afterwards. He might not have suspected the task would be a death trap, but he knew it would likely be illegal and possibly dangerous. I interpret the order as an intentional precaution.

The exact reasons why Regulus turned against Voldemort are very open to interpretation. It could be he believed that making a Horcrux was going too far. It could be, as Sirius suggested, that he got squeamish about the reality of what being a Death Eater involved. But I do think protectiveness towards Kreacher must have been at least part of his motivation.

Why? Because he drank the potion himself.

This isn't an accident, either. It's emphasized by the narrative: Harry initially assumes Regulus ordered Kreacher to drink it, only to be corrected. It's portrayed as a shocking twist, and for good reason.

For most wizards, especially ones with Regulus's background, making the elf drink the potion would be the obvious solution. Hermione is right when she says what Voldemort did isn't that far outside the norm. Slughorn, who is generally one of the more positively portrayed Slytherins, used a house-elf to test wine for poison. The Blacks' family tradition is, specifically, "beheading house-elves when they got too old to carry tea trays" (OotP ch. 4) - so, they don't just preserve them that way after their death, they kill them as soon as they are no longer useful. Brutal physical punishments seem to be common, and their enslavement is accepted as normal and right by literally every character except Hermione. Wizarding society as a whole does not value the lives or welfare of house-elves.

But in the cave, Regulus prioritizes Kreacher's safety above his own. He drinks the potion himself rather than ordering Kreacher to do it, and once they've got the locket, he tells Kreacher to leave him behind. Regulus could very likely have made it out of the cave alive if he had been willing to sacrifice Kreacher, but instead, he ensured that Kreacher would be the one to survive.

Despite everything he had ever been taught about house-elves and their place in society, despite openly holding blood purist beliefs, despite it meaning the all-important family name would die out, he put Kreacher first. He kept Kreacher safe at the cost of his own life.

#Harry Potter Franchise#Regulus Black#Kreature#House Elves#Regulus Black Meta#Opinion: Plausible#Harry Potter Books

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black family as representatives of ancient "Anglo-Saxon elite"

To me Blacks were never partially French. I'm not saying the headcanon "Blacks are partially French" isn't valid, it's just not as interesting to me and it strips away nuances from their history. Here's why.

(It’s just my fantasies mixed with historical facts! Don’t take it too seriously)

Firstly, their choice of surname.

I've noticed that two main Death Eater families bear surnames of French and Norman origin. Lestrange and Malfoy (fictional, but the "origin" is clear). And then there's Rosier and Avery. Rosier – definitely French, and Avery – from the Middle English and Anglo-Norman French personal name Aevery, a Norman form of Alfred. There are no other surnames like this in Harry Potter, except for Peverell (correct me if I'm wrong).

Clearly, this is a reference to the Norman Conquest of 1066. These Death Eaters could be associated with aristocratic and influential families who came to England after the Norman Conquest. This is a nod to the historical division in English society between Normans and Anglo-Saxons, where Normans represented the upper echelon of society, while Anglo-Saxons were less privileged.

Yes, I'm Captain Obvious here. So let's move on to the Blacks.

The surname Black is typically Anglo-Saxon. It could have derived from the Old English word 'blæc,' meaning 'black' or 'dark,' and may have been used to describe someone who wore black clothing or had dark hair.

(Old English emerged around the 5th-6th centuries and was used in England for about 600 years, until the 11th century. This period ended after the Norman Conquest in 1066).

Hogwarts, canonically, appeared over 1000 years ago. That is, before the Norman Conquest. (But Hogwarts Castle couldn't exist yet, because castle technology was brought by the Normans). The Blacks call themselves "the noble and most ancient house of Black." That is, the oldest family, and also the noblest. Maybe they were "noble" in the sense that they belonged to the elite of Anglo-Saxon society (which was fragmented into small kingdoms). But they consider themselves the oldest family among those who trace their lineage and uphold the nobility (purity) of their blood. Considering that "Hogwarts" appeared before the Norman Conquest, I fantasize that such families already existed back then. A lot of families are extinct. Except the Blacks.

So the Blacks are a reflection of "Anglo-Saxon aristocracy." And here I headcanon that the Blacks still considered themselves more entitled than everyone else, mocked the Malfoys and Rosiers, and generally looked down on anything French. Fanatics to the bone and lovers of elevating themselves above all.

Why the motto in French – in the Middle Ages, the use of Latin and French languages was common among European aristocracy (despite the fact that there is NO aristocracy among wizards, but they could have been part of the aristocracy before the introduction of the Statute of Secrecy). The French language was often considered the language of diplomacy and culture, and its use in mottos and coats of arms was a common phenomenon. Here I just headcanon that one of the Blacks either had a strange sense of humour, or wanted to put an end to the ancient feud of the Blacks with all things French and start the family on some new beginnings. Maybe they married someone with French roots to expand their influence.

Of course, all this can be explained differently. The headcanon that the Blacks have some French part also makes sense. But for me personally, that's not so interesting, considering the obvious connections of the Lestranges and Rosiers with France (Vinda Rosier, Lestrange family Mausoleum in Paris). I prefer the Blacks who are so arrogant that they even consider themselves "true English wizards," not "like those Malfoys." And I headcanon that this was not a real confrontation, but rather a pretext for jokes and fuel for greater kindling of their vanity.

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Been thinking about how Bill legitimately had a horrifying reason (the literal progressive disintegration of the nightmare realm that erases whatever it disintegrates from existence completely) to move himself and his crew into a new dimension. Like that's terrifying. And yet he never utilizes this to his favour. He could have been honest about this with Ford, and you KNOW as long as Bill didn't mention plans of overtaking the earth, Ford would've made the portal for him, both out of Ford's own interest and because Ford when faced with these big moral questions will pull through. But this is a card Bill NEVER plays because although he needs to leave the dimension, he cannot lose face. He can't put aside his pride and admit to the humility that he needs to flee from his dimension, that he's not actually all powerful. And so instead he pretends to be a muse and when Ford figures out something else is going on, instead of being open and humble and saying that his dimension is unravelling, Bill focuses on that he's going to over take earth, that he's actually been a monster all along, surprise Ford!

And part of it is definitely because Bill's built himself up on power and violence and to grovel and earnestly ask for help, to admit that he cannot stop the unraveling of his dimension completely invalidates that; showing vulnerability? Can't do that, even under the guise of lying to get his way. And part of it makes you wonder if it's also a form of self-sabotage, because underneath his deep denial Bill is guilty over what he occurred; he sees himself as a monster and so he'll be that monster, and having people recognize that feels good in the same way that pressing a bruise feels good. But it makes you wonder what would've happened if Bill even just was open about his dimension unravelling and had lied about overtaking the earth.

It's also interesting because although Bill has SOME charisma and can manipulate people decently well (as evidenced by his cult, and pandering to people's desires with Ford, Mabel and Blendin), he refuses to be vulnerable, refuses to not be true to his off-putting self, even when if he was just vulnerable of pretended to not be himself, to put aside the (false) pride he has in himself he would've gotten a portal by now. and part of me wonders if it's because it's this false pride that built on insecurity and denial on who he is he cannot drop that mask.

Further thoughts on this!

940 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd like to propose a dark horse candidate for the most interesting line in The Book of Bill. And it's this near-unreadable, seemingly one-off joke from the "Skin" page:

[ID: tiny text reading: "Help! This is not Bill Cipher. My name is Grebley Hemberdreck of Zimtrex 5. I'm one of thousands of beings Bill has devoured over trillions of years whose souls are now trapped inside him. You have to free me! It's horrible in here. He just keeps playing the song "Good Vibrations" by Marky Mark on an endless loop. Please, please, this is not a joke! The Zimtrexians were once a proud and mighty people, but now our spirits long for release from this..." End ID.]

Okay, so Bill devours souls who then live out a horrible existence inside him. That's just some typical and expected Bill behavior, right? Nothing to be shocked by? Maybe not, but one thing jumps out at me... and of all things, it's the way that Bill keeps playing that Beach Boys parody on loop.

Because in The Book of Bill, there's a recurring motif of characters playing music for a very specific reason: to repel an unwanted presence inside their head. This is what Elias Inkwell, and later Ford, did with the "It's A Small World" parody — they tried to keep Bill out of their brains. Or, metaphorically... to drown out his voice.

[ID: a Journal 3 page with a cassette taped inside. It's titled: "The World Is Small Ever After for Always." Ford writes: "If it's war you want, it's war you'll get! If you want to torture me? I'll torture you back!" End ID.]

That doesn't necessarily mean that Bill finds the voices of devoured souls to be troubling, let alone downright haunting, does it? Well... not quite on its own. But there's a "color" code on the page about TV static that says a lot:

[ID: a code consisting of colorful squares, translated to letters that spell out: "he never sleeps he never dreams but somehow still he hears their screams." End ID] (screenshot courtesy of @fexiled)

The context of the page implies these "screams" come to Bill especially when he listens to TV static, and the broader context of the book implies that these are the screams of his destroyed home dimension, Euclydia. Therefore, not necessarily those of the souls he devoured, from Zimtrex 5 and possibly other dimensions.

Except... do those two things really have to be mutually exclusive?

The beings that Bill devoured were accumulated over "trillions" of years, plural, according to Grebley. In Weirdmageddon 1, Bill claims to have resided in the Nightmare Realm for precisely "one trillion" years. So the "devouring" habit probably extends back even further than his time in the Nightmare Realm...

Enter @acetyzias, pointing out a very conspicuous word — and one of the only uncensored words — from Bill's description of destroying his home dimension:

[ID: the word "mandibles". End ID.]

Oh, and how does Bill describe the "monster" that destroyed his home to Ford, when Ford asks about revenge?

[ID: Journal excerpt reading: "Sixer, it would eat you alive." End ID.]

For a long time, Bill's destruction of his home has been associated with fire, even when the story's told by Bill himself. But through the way the book characterizes Bill's guilt — and characterizes how the consequences of what he's done remain lurking deep inside him — I think The Book of Bill lays out the hints for another motif: devouring.

And, well, when it comes to how Bill destroys things... it wouldn't be without precedent.

[ID: screenshot of Bill in Weirdmageddon 3, taking a bite out of the Earth. End ID.]

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I'm not the most eloquent writer so forgive me for if this sounds clunky

but I think Filbrick and Bill are both good mirrors in the way that they treat Ford.

They're both authority figures (one a father, and one a self purported sort of deity) who isolate him out as someone whose talents have earned their favor.

"You are the smarter son, so I'm going to pay closer attention to you and your achievements. I'll do whatever to make sure you keep furthering them." and "You are one of the smartest humans, so I'll be your muse. I'm going to guide you to keep furthering your achievements."

Meanwhile, they both had the exact same goal. "This guy is going to get me out of here."

Except, you know, one of them is talking about the nightmare realm and the other one is talking about New Jersey.

They both deliberately separate him from his only supports. Stan holds you back, he's getting kicked out. Fiddleford holds you back, you need to stop speaking with him.

And as soon as Ford makes one misstep, or even just a pause from that goal, the "favored" status he was given is held hostage. Suddenly he's nothing. If he doesn't step back in line quickly he'll continue to be nothing, or less than nothing. Will they ever care about him again? Next time, will he lose them forever?

Everything rides on Ford's shoulders, everything's his fault. With Filbrick, we saw what happened with Stan. Ford saw what happened with Stan. He knows how fast someone can just be dropped. With Bill we know he would ditch Ford for extended periods of time without notice. And we know Bill's retribution eventually furthered into explicitly shown violence.

I don't know how to end this train of thought. It's just all very terrible. And Bill knew Ford already had experience being treated this way. He was a calculated target.

713 notes

·

View notes

Text

the most interesting tension in any analysis of The Book of Bill, in my opinion, is the pendulum between "Bill is explicitly trying to manipulate us, we can't trust a word he says," and "with a few notable exceptions, most of which relied on the victims not knowing who they were dealing with, Bill is constantly failing onscreen at manipulating people. he's actually bad at this <3"

(or, rather: it's not that he's not a threat, but there's a certain level of 4D chess puppet master behavior that he's simply not capable of. it's not that any victim was dumb for being tricked by him — if he correctly identifies an insecurity, he can absolutely run with that long enough to ruin lives. but it gets so interesting when, say, Bill's narration (unreliable source) has subtext that a character like the Axolotl (tentatively probably reliable source) corroborates explicitly. say, all the signs in the book pointing to Bill's denial and guilt, and the Axolotl explicitly declaring that Bill misses his home and lies about being happy. do we believe that Bill is skilled enough, or has enough faith in the reader's intelligence, to plant subtextual clues to that guilt to make us sympathize with him? well, I don't think that's an inherently incorrect reading — but in light of corroboration from the Axolotl, I think it's at least as likely that Bill is just floundering, and the truthful details he normally suppresses about his backstory are starting to leak out.)

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing I don't really see anyone talking about with regards to Gravity Falls is the parallel's between Ford's apprenticeship and Mabeland. Many, many times, the question has been raised 'should Dipper have accepted Ford's apprenticeship', but no-one ever argues 'should Mabel have stayed in Mabeland', for obvious reasons, the show portrays one as a no-brainer and the other as a complex decision. But I think the two situations parallel one another nicely.

For Dipper, taking Ford's apprenticeship is definitely the more attractive option. He doesn't appear to have a lot of friends in Piedmont, has been historically bullied and may still be, and Dipper generally doesn't want to deal with the trials of growing up. Ford meanwhile, basically treats Dipper like an equal, not like a kid, encourages Dipper, and allows Dipper to pursue his interests to the fullest. However, to take the apprenticeship, Dipper will be cloistering himself in an environment in which he never has to do the things he's scared of, he avoids confronting the realities that he doesn't want to deal with, and he'll miss out on going through life with his sister.

For Mabel, staying in Mabeland is the more attractive option. There's an apocalypse raging outside, her brother is growing away from her, she's going to have to leave friends that it's implied are the best she's ever had, and we know that she too, has been bullied in the past, and may still be, and Wendy's well and truly terrified her about the concept of growing up. In Mabeland however, Mabel can continue to live in a charmed reality, surrounded by the things she's interested in and in an environment where she's constantly being enabled, and any dissenters are ejected. However, to remain in Mabeland, Mabel is cloistering herself in an environment where she never has to do the things she's scared of, she avoids confronting the realities she doesn't want to deal with, and she's pushed away one of the most important parts of her life: her brother.

During Dipper's trial, we as viewers see Mabel's change of heart as Dipper shows her that despite the trials the real world has thrown at both of them, that they've always had each others backs, and Dipper realises that too (there was a really good essay on this a while back by @cryoalliums ). Even though they're both scared, and both wanting to avoid the reality of adolescence and high school and unpredictability, they both realise through Dipper's trial that by burying themselves in their respective fantasies, they'll lose the one person who's always had their back: each other. Whether or not it's bullies or a giant robot, the twins have always had each other as a support system, and an ally, and they both realise during the trial that they'd rather fight by one another's side than hide from their problems.

So sure, Dipper could have taken the apprenticeship. He could have chosen to take the tailor-made, one-on-one advanced education that allowed him to pursue his interests to the fullest. But Mabel could also have chosen to stay in the world surrounded by her interests, where she was safe from the things she wanted to avoid. I think it's interesting that these two situations are so paralleled, and yet it's rarely discussed.

486 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dipper v. Emotional Conflict

After re-watching every episode of Gravity Falls, listening to every commentary track available, and reading “Lost Legends”, I’ve come to the following conclusion about Dipper Pines:

His greatest weakness is his inability to resolve internal emotional conflicts on his own.

I see a lot of my younger self in Dipper. We’re both nerdy dorks who are confident—often to a fault—in our ability to think, plan, or argue our way out of conflicts. Logical reasoning comes naturally to us; emotional sensitivity does not. We shine the brightest when tasked with solving problems devoid of emotional complications because we have a hard time understanding them. So when cornered by emotional conflicts that are difficult to resolve or that are unfamiliar, our confidence nosedives.

Dipper’s response to unfamiliar or difficult emotional conflicts depends on both the circumstances in which the conflict arises and whether the source of the conflict is external or internal. In “Dipper v. Manliness”, Dipper’s self-confidence is challenged externally after he’s publicly emasculated by failing a strength test and privately emasculated after Mabel and Stanley make fun of his love of BABBA, a stereotypically feminine pop group.

This conflict does not require immediate resolution, so Dipper does not immediately face it. Instead he wanders into the woods, eventually finding guidance in the form of the Manotaurs, a clan of hypermasculine half-man half-taurs.

Keep reading

461 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dipper is a nerd but he's not a STEM nerd. He likes puzzles and codes and mysteries and cryptids and DD&MD and elaborate schemes - we don't see any particular interest in machines or computers or in chemical/biological/geological analysis of the various weirdnesses he uncovers. His Journal entries are super people-focused ("I raised the dead" is explicitly less important than "Stan knew all along!!" which. BUDDY). His life goal is, and I quote, to get into "a good technical college with a photography and media production minor to start my own ghost hunting show."

I love that Gravity Falls has a bunch of different flavors of nerds. Ford is "every science under the sun" and Mabel is "every artform" while Dipper and Stan and Soos are all harder to pin down. It's fun. We've got nerd diversity.

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's so interesting to me about Dipper is that he has no friends!

Okay, that's not necessarily true. dipper gets along very well with Soos, for example, and he's the twins' primary big brother figure for most of the show (we love u, soos!) dipper also grows very close to wendy, and in the end chooses to treasure their friendship more than he does any romantic feelings for her. he isn't lacking in terms of having important people in his life

but there's no one his age !

the closest we see to dipper having any sort of friend group is when he hangs out with wendy and his friends, which is obviously very telling of the fact that he wants to grow up, and he wants to grow up fast. consequently, he doesn't really want to be friends with them, per se, as much as he wants to impress them and prove that he's more than just a kid

(this is also contigent with his feelings for wendy, thematically speaking, but that's a conversation for another day)

along this train of thought is the fact that wendy's friends don't see him as a friend, either, simply because they are unequals out of age difference alone. this doesn't mean that they dislike him, in fact they're glad to have him around, but dipper's an accesory and not an actual member of the group, which is not necessarily a bad thing, simply that it's different

in general, the only person dipper interacts with in more or less an equal level is mabel, except her case is very different!

from her countless love interests, we see she has a very easy time interacting with people as early as tourist trapped, she is not shy ! she is not insecure ! she flirts, she giggles, she parties, you go mabel !

the most important element to this, i think, would be how in contrast to dipper, mabel manages to make a little friend group who share common interests and have similar personalities (candy and grenda)

this is not because dipper is somehow weirder and mabel the socially charming one. in fact, mabel doesn't enjoy a particularly popular reputation, and is thought of by pacifica as silly and childish during irrational treasure

from the very beginning, we see mabel and pacifica clash in a classic "weird vs mean" dynamic, with pacifica being someone who enjoys a favourable status in gravity falls (a little bit like a celebrity) and continuously antagonizes mabel, who hangs out with candy and grenda, consistently portrayed as weird and unpopular since their introduction during double dipper

regardless, mabel has no trouble making friends. she isn't a popular girl, but she is a social girl

you'd think that mabel, who has the wider support network, would be less dependant on dipper than dipper is on her

that's definitely the case in the valentine's day flashback shown in weirdmaggedon part 2, where mabel has a considerable amount of valentines, while dipper gets none and is mocked to the point of physically having to run out of class. he even hides his birthmark all the time because the kids made fun of him for it !

so it's very interesting that when we see the twins face the idea of permanent separation, it's mabel who doesn't want to leave dipper, not the other way around !

ps; pleeeeease send me asks about gravity falls i want to talk about this show so badly

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Enduring Quest for Recognition: A Psychological Analysis of Dipper Pines' Need for Validation

(Since I did one about Mabel, I feel obligated to do one about Dipper)

Introduction: The Mystery-Solving Protagonist

Mason "Dipper" Pines, the inquisitive and detail-oriented twelve-year-old protagonist of Gravity Falls, quickly captures attention as an adventurer constantly on the lookout for riddles and the extraordinary. His possession of Journal 3, a mysterious journal document detailing the supernatural anomalies of the town, serves as a catalyst for numerous adventures undertaken with his twin sister Mabel. While Dipper's intelligence and perceptive nature are evident in his pursuit of the unexplained, a deeper examination reveals a compelling undercurrent: an obsessive need for validation. This yearning for approval and recognition shapes his interactions and significantly influences his relationships, presenting itself as a complex characteristic with both empowering and limiting facets.

Developmental Factors: Pre-Teen Identity Formation

The roots of Dipper's validation-seeking behavior can be traced to several interconnected factors, prominent among them his pre-teen age. At twelve, transitioning into adolescence, individuals often experience heightened self-consciousness and a growing awareness of social standing. This developmental stage is marked by a crucial focus on self-esteem and the establishment of a sense of worth, frequently influenced by external feedback. Dipper's desire to be seen as wise beyond his years and his impatience to grow up suggest a potential discomfort with his current status and a longing for the respect associated with maturity. This eagerness to accelerate into adulthood could stem from an unconscious desire to bypass the perceived awkwardness and vulnerabilities of childhood, aiming to attain a level of esteem he feels is currently out of reach.

Family Dynamics: The Twin Relationship

Furthermore, the dynamics within Dipper's family structure likely play a role in shaping his validation needs. His close relationship with his twin sister Mabel, while a source of unwavering support, also presents a unique context for his development. Mabel's eccentric, energetic, and socially adept nature often contrasts with Dipper's more serious and sometimes awkward demeanor. This contrast could inadvertently foster a need for Dipper to seek external affirmation of his own strengths, particularly his intelligence and problem-solving abilities, to establish a distinct identity within the sibling dynamic. The generally positive bond they share, however, provides a crucial foundation of acceptance, which Dipper may subconsciously rely on as he navigates his quest for validation in other relationships.

Romantic Pursuits: The Wendy Factor

Dipper's interactions with others are frequently colored by his underlying need for approval, most notably in his pursuit of Wendy Corduroy's affection. His persistent crush on the older, seemingly effortlessly cool teenager is a prime example of his validation-seeking in action. Dipper consistently attempts to impress Wendy, often by trying to project an image of maturity or competence that aligns with her older age group. Whether feigning interest in activities he doesn't genuinely enjoy or concocting elaborate schemes to spend time with her, his actions are often driven by a desire to gain her positive attention and acceptance. These attempts, however, frequently result in awkward or misguided situations, highlighting the disconnect between his genuine self and the persona he tries to adopt. Wendy's eventual, albeit gentle, rejection serves as a significant turning point, prompting Dipper to confront the reality of their age difference and begin to re-evaluate his approach to relationships and self-worth. His pursuit of Wendy appears less about profound romantic interest and more about seeking validation from someone he idealizes as embodying coolness and maturity, qualities he desires for himself.

Sibling Rivalry: Competition and Support

The interplay between Dipper's need for validation and his relationship with Mabel is multifaceted. While Mabel often serves as a supportive figure, instances of sibling rivalry are sometimes fueled by Dipper's insecurities. The episode "Little Dipper," for example, showcases his intense preoccupation with being the same height as, or taller than, Mabel, driven by a desire to avoid her teasing and perhaps assert a sense of superiority. Mabel, at times, playfully teases Dipper about his height or other perceived shortcomings, which, while typical sibling behavior, may inadvertently exacerbate his underlying need for external approval. Conversely, there are numerous occasions where Dipper's pursuit of his own goals or validation leads him to inadvertently disregard Mabel's feelings or needs. Despite these moments of conflict, Mabel remains a steadfast source of support, frequently encouraging Dipper's endeavors and bolstering his confidence, demonstrating a complex sibling dynamic where Dipper's insecurity can cause friction, yet Mabel's support provides crucial validation.

Mentorship Dynamics: Seeking Approval from Authority Figures

Dipper's interactions with the authority figures in his life, Grunkle Stan and Great Uncle Ford, also reveal his validation-seeking tendencies. With Grunkle Stan, Dipper often yearns for respect and acknowledgment of his growing maturity. Episodes like "Dipper vs. Manliness" clearly illustrate his desire to prove his masculinity and gain Stan's approval. His attempts to win the "Manliness Tester" and his later quest to grow chest hair are driven by a desire to be seen as capable and "manly" in Stan's eyes. His relationship with Ford, on the other hand, centers on seeking validation for his intellect and shared passion for mysteries. Dipper is eager to impress Ford with his knowledge and problem-solving skills, viewing Ford's recognition as a significant affirmation of his intellectual abilities. In both relationships, Dipper's desire to be perceived as mature and competent influences his behavior, highlighting his ongoing quest for external approval from those he looks up to.

Peer Relationships: The Soos Connection

While perhaps less prominent, Dipper's interactions with Soos also suggest a subtle need for peer approval. As the slightly older handyman at the Mystery Shack, Soos often serves as a friend and confidante to Dipper. Dipper's inclusion of Soos in his mystery-solving adventures and his occasional attempts to impress him with his findings could be interpreted as a desire for acceptance and camaraderie from someone closer to his own age group. While his primary validation needs appear directed towards Wendy and his uncles, the dynamic with Soos indicates a broader desire for positive affirmation across his social landscape.

Strengths and Vulnerabilities: The Double-Edged Sword

The obsessive need for validation that characterizes Dipper Pines is a double-edged sword, acting as both a driving force and a potential hindrance. On one hand, this yearning for approval can be a powerful catalyst for growth and determination. Dipper's relentless pursuit of the mysteries in Gravity Falls is undoubtedly fueled, in part, by a desire to validate his intelligence and abilities. The act of uncovering the town's secrets often brings recognition from Mabel, his uncles, and even occasionally the wider community, reinforcing his sense of self-worth and motivating him to delve deeper into the unknown. This desire to prove himself can also lead to acts of bravery and resourcefulness, as Dipper confronts dangerous situations in his quest for answers and, perhaps, admiration.

Consequences of Validation-Seeking: Limitations and Risks

However, Dipper's reliance on external validation also presents significant weaknesses. His constant need for approval can lead to insecurity, self-doubt, and a tendency to overthink his actions and interactions. The fear of disapproval or failure can sometimes paralyze him, preventing him from taking necessary risks or leading to poor decisions driven by a desire to please others. Furthermore, his yearning for acceptance can make him susceptible to manipulation, as seen in instances where he is swayed by the promise of recognition or inclusion. This dependence on external sources for his self-worth can hinder his personal growth, making him overly concerned with the opinions of others and potentially limiting his ability to develop a strong, independent sense of self.

Key Episodes: Validation in Action

Several key moments in Gravity Falls vividly illustrate Dipper's need for validation and its consequences. In "Double Dipper," his elaborate and ultimately unsuccessful plan to impress Wendy by creating clones of himself highlights his reliance on external strategies and his overthinking of social interactions. "Dipper vs. Manliness" provides a clear example of his quest for respect, as he seeks to embody stereotypical masculine traits to gain approval from Stan and the Manotaurs. The episode "Little Dipper" focuses on his insecurity about his height, showcasing how his need to feel superior, even in a minor way, can drive his actions and affect his relationship with Mabel. Finally, "Dipper and Mabel vs. the Future" demonstrates his strong desire for intellectual validation and belonging, as he eagerly accepts Ford's apprenticeship, leading to conflict with Mabel and forcing him to confront his priorities.

Psychological Frameworks: Understanding Dipper's Behavior

Psychological frameworks offer valuable lenses through which to understand Dipper's behavior. Attachment theory suggests that early experiences with caregivers can shape an individual's need for external validation, though the series provides limited information about Dipper's early childhood. Social comparison theory posits that individuals evaluate their own worth by comparing themselves to others, which is evident in Dipper's constant comparison to Wendy and the older teenagers in Gravity Falls. Erikson's stages of psychosocial development place adolescence as a critical period for identity formation, where the conflict between identity and role confusion is central. Dipper's validation-seeking aligns with this stage, as he explores different facets of his identity and seeks affirmation from his social environment. Furthermore, Dipper's behaviors strongly resonate with the characteristics of the approval-seeking schema, where individuals believe they need external approval to feel loved and worthy. His dependence on others' reactions, sensitivity to criticism, and desire to fit in or gain admiration are all indicative of this schema.

Conclusion: A Journey of Self-Discovery

In conclusion, Dipper Pines' journey through the enigmatic town of Gravity Falls is not only a thrilling exploration of the supernatural but also a fascinating study in adolescent psychology. His obsessive need for validation, while sometimes driving his ambition and determination, also exposes his underlying insecurities and occasionally strains his relationships. Ultimately, Dipper's experiences in Gravity Falls, marked by both successes and setbacks in his quest for approval, subtly guide him toward a greater understanding of his own worth, independent of external affirmation. His enduring quest for self-worth reflects the universal challenges of adolescence, making his character relatable and his journey a compelling narrative of growth and self-discovery.

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

You ever think about how in spite of knowing their exact locations, the game never gives any indication that templar Carver has reported his mage sibling, Merril (a blood mage) or Anders (an abomination) to his superiors?

I do think about that a lot, even though I tend to ignore the Templar Carver route because I know Warden Carver to be true in my heart and soul... but I totally get the appeal of Templar Carver within DA2's narrative, y'know?

It's so fascinating, really. I've never played a run with Templar Carver, I just can't bring myself to do it, so I know I'm missing out on smaller details of it. From what I do know, this drives me crazy in the best way possible.

Deciding whether to bring him or not to the Deep Roads is such an important choice, not only because it affects his fate, but how it affects his relationship to Hawke. He tells you that he wants to go, he makes it very clear that it's important to him that he goes, too... and Hawke can just leave him behind and it hurts him. I don't think that registers enough with some people just because of how Carver is, like it doesn't matter what Hawke's motivations are [staying behind for his safety, not wanting to bring him, thinking someone should stay with Leandra, etc] it still hurts him because it tells him that Hawke doesn't need him, and Carver wants to be needed.

And yes, there are other contributing factors to why he joins the templars, but it doesn't matter what your relationship is to him, it doesn't change the fact that he doesn't turn Hawke or his companions in.

Sure, the meta reason is it's a video game and you're playing the main character. You're never in any actual danger of being captured by templars, and you're not going to lose your companions to them that easy.

But if we look at it through the narrative and Carver's character, that's when it gets interesting. You can max out his rivalry and be an utter asshole to him [there's a point where you can call him a brat and mock him for being stuck in your shadow, like Hawke can be real cruel about it] but it doesn't matter, you're still his sibling. He even makes a remark about how you might not know what that means [referring to leaving him behind] but he does. He refuses to kill Hawke in the end when Meredith makes the order, too.

Which can I just point out that Hawke has the option to let Bethany die in the end if she's with the circle and they side with the templars? Just saying, Carver NEVER does that no matter what, but Hawke has the option to betray Bethany like that and it's fucked and interesting and it makes me want to eat my chair-

As for Merrill and Anders, I think he knows that if he turns either of them in, then the chances of Hawke being brought in as well skyrocket. They're all friends, they're in the same group... bring one in, and you'll probably get the other two.

I also think Carver just genuinely likes Merrill. Yes, I'm a Carver/Merrill shipper, so I have a bias, but even if you remove anything romantic from their dynamic I believe that's true. Of all the companions, Merrill is the only one who doesn't make fun of him, or find him annoying, in party banters. He never snaps back at her, like he's never defensive with her, he's just a little awkward and nice.

Like, HE'S SO NICE TO HER! He tries to find common ground with her! She asks him about "swording" and he's taken aback by her saying he's good at it, but you KNOW that if someone like Anders asked him the same question, he's be all, "shut up, you're stupid, stop talking to me >:["

Think back to that banter Carver can have with Aveline post-act 1 where they're talking about how the guard wasn't the right place for him [hard disagree with you there, Aveline] and Carver says he was a bit of a tit, wasn't he.... and every companion will agree except Merrill. She doesn't say anything, whereas other companions like Anders will be like "ugh maker YES" and if you have a purple Hawke, they'll go on to other ways Carver was a tit like?? I think Carver and Merrill got along and he doesn't want to turn her in because she was nice to him! And she's a blood mage! He knows what will happen to her if the templars get ahold of her! He doesn't want to see her made tranquil or killed!

At that point, he's witnessed what bad blood mages can do, assuming you've brought him along for those quests, but even so. He knows Merrill isn't like that and he likes her, so of course he's not going to turn her in despite that being his literal duty.

Then there's Anders who Carver doesn't like. If you're in a romance with him, Carver will tell him that's why he doesn't turn him in but c'mon Carver, you know that's not the only reason. My theory is Carver may not like Anders and he knows the man's got a spirit of justice inside of him... but Anders also runs a free clinic. If he's ever taken in by templars, then so many people [including a LOT of Fereldan refugees] will be without free health care and will suffer for it. I think in Carver's eyes, Anders might be irritating but he doesn't more good than harm. Carver knows first hand how shitty refugees and poorer people are treated in Kirkwall. Anders' clinic is the one place they can go for help and actually get it, and he's not going to be the one to take that away because the templars say "magic bad."

So yeah, I'm not as informed about the Templar Carver route, but I do think about how if I did do that route, he wouldn't betray Hawke or their companions no matter what and what that says about him.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stan twins: codependency & identity issues

“I tell you it’s unnatural for siblings to get along as well as you do,” says Stan to Dipper and Mabel in Not What He Seems, clearly missing his own relationship with Ford before things started to change. “We used to be like Dipper and Mabel,” says Ford in Weirdmageddon 3: Take Back the Falls. Were they really, though?

I think what many people don’t get about Stan and Ford’s dynamic as children, or even as teenagers, is that, no matter what Stan and Ford think or say about it, they were not like Mabel and Dipper. That just highlights their lack of self-awareness. Here’s a canon analysis for anyone who cares to understand my point:

Mabel and Dipper have overall very different interests and hobbies and act separately on them. They have other friends and spend time with them—well, at least Mabel has Candy and Grenda, as the bubbly social butterfly she is; Dipper, on the other hand, seems way more preoccupied with deciphering the mysteries of Journal 3, but doesn’t miss an opportunity to be included in Wendy’s cool teenage group, as seen in episodes The Inconveniencing and The Love God (in the latter, he seems to be actually succeeding). As fraternal twins of different genders, no matter how alike they look (and despite Mabel’s joke of being “girl Dipper”), they still manage to retain pretty distinct identities. No issue here.

Mabel does her sleepovers, goes to boy band shows, and has encounters with potential crushes. When a surprised Dipper asks her about her vampire love in The Deep End, she points out, “I don’t tell you everything.” Dipper, meanwhile, explored the town with Soos, went to Wendy’s house, hung out with her teen gang, and overall lived many adventures without Mabel, such as trying to prove himself a man with help of the Manotaurs. I think the episode that shows the healthy independence Dipper and Mabel had from each other the best is probably Carpe Diem, inspired in Alex’s real life frustration with his sister, Ariel, but it can be observed all through the series:

What is shown to us in AToTS already differs from that. The Stan twins were inseparable, and each other’s only friends, as Stan establishes early on in his narrative: “Those bullies may have been right about us not making many friends, but when push comes to shove, you only really need one.”

With his question to Ford in the Lost Legends comic, The Jersey Devil’s in the Details, Stan implies they really did everything together, in a way reminiscent of Phineas and Ferb: “So what’re we gonna do today, buddy?”

Even small details, like the toys in their room, served to show the difference between the Stans and Dipper & Mabel, as Matt Chapman clarifies on the episode’s official commentary:

You also see that at this age, all the stuff that would cross over, that would appeal to both of them. You know, it’s not just like, oh, there’s science stuff here and then there’s like—I don’t know—what little Stan would be into. It’s like, no, they both like all this.

“But Mabel was just as desperate in Dipper and Mabel vs the Future as Stan was in A Tale of Two Stans!” Yes, true. She was, and I do believe her relationship with Dipper was the most important one in her life. But do you think the facts that a) she was already terrified of growing up, as shown in the episode Summerween, b) Candy and Grenda declined her invitations to their birthday party, c) Wendy showed her the apparently terrible reality of being a teenager, and d) Stan told her that it would be fine because at least she would always have Dipper... had nothing to with it? Originally her parents were going to forbid her from bringing Waddles to Piedmont, as revealed in the episode commentary of Dipper and Mabel vs. the Future, as just one more heartbreaking thing on the pile of Mabel’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. (Of course, teen Stan’s circumstances were aggravated by the bad home situation he was being “left alone” in by Ford—just like Mabel! Whose parents were arguing, per TBoB canon, to the point of giving Dipper recurring nightmares.)

Another very important thing is that the poor girl was twelve years old, while Stan was presumably seventeen-ish, an age at which separation would be normal and even expected, with the time for college approaching. In fact, differently from what happened with Mabel, whose imminent separation from Dipper came out of left field through an unexpected proposal by Ford (foreshadowed only by her slight discomfort over how close Ford and Dipper were becoming), there was a blatant rift between the teen Stans that Ford went so far as to acknowledge to Stan’s face. Using Stan’s own words from the Land Before Swine commentary: “Anyway, cut to high school, the guy’s never kissed a girl, prom is coming up, and he asked me for advice. ���Stanley, I know things have been a little weird between you and me with college, but can you talk to me about girls?’” That was before prom (the one in which a girl threw fruit punch at Ford), mind you.

And still, this is what Stan thinks when he realizes Ford is going to accept the scholarship: “Without Ford, I was just half of a dynamic duo. I couldn’t make it without him.” He saw himself as only half of a whole—no wonder, with the way both twins were pushed to believe this since their birth, when they were both named Stan.

When asked about Shermie, Alex observed that a crucial part of their dynamic is that they only had each other. No younger or older brother to support them. The quote from HanaHyperfixates’ and ThatGFFan’s interview:

In terms of Shermie, I remember asking Rob or somebody at some point, like, “Would Shermie be here, logically? Do we have to see him?” I don’t really wanna see him. I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in Stan and Ford being—sort of having only each other and then losing each other because of their different life paths.

I think the suggestion was, “Maybe Shermie would be a baby. Maybe that would happen.” And being like, “okay sure.”

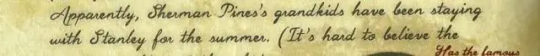

Let’s not forget, too, the only time Ford ever mentions Shermie in Journal 3—“Sherman Pines’s,” surname and all:

From my own observations about their parents, that point is only driven further home.

Filbrick is, well, Filbrick. I don’t think I need to explain much here; every one of us has different interpretations and headcanons about him, but they seem to all agree on the common factor he wasn’t a good father—how much that can be justified by their time period or stretched to accommodate the most heartwrenching stangst is up for debate, just not a subject for this post.

Caryn is more complicated. I think Filbrick was definitely ‘worse’ than her, so to speak, at least in a more obvious way, and she has canonically demonstrated considerable fondness for Stan in particular—according to her, Stan’s rambunctiousness can be attributed to an excess of “personality,” he’s her “little free spirit.” She was, most notably, one of the two people present at Stan’s funeral if the info on the new website is to be trusted. We see her smiling brightly in the picture of the baby Stan twins included in TBoB, which hints at the fact she indeed liked her kids.

But the fact that she, as an adult, didn’t intervene when Stan was kicked out is simply, in my point of view, inexcusable. One could say she was momentarily paralyzed from an overwhelming fear of Filbrick, as a supposed victim herself, but a) that’s already entering headcanon domain, and b) I think that’s far from the truth and directly contradicting the comics, in which she looks happy and relaxed in the company of Filbrick: initiating contact and kissing him on the cheek, comfortingly stroking his back, looking at him with can only be described as tenderness... I don’t think Filbrick is meant to be seen as a monster, not in an exaggerated way. (He’s shown to be touched by Stan’s little stunt with the golden chain, too.) Just a really shitty father, in a common, boring, more nuanced, no less traumatizing, way.

Borrowing a paragraph from a previous analysis:

To me, the most telling thing of all is the fact Stan calls for Ford to help him, not his own mother. Ford, his brother, same age as him, who was at the moment beyond furious with him and very unlikely to show any compassion. Ford, whose attempts to change Filbrick’s mind would more likely than not have been unsuccessful. Not Caryn, adult, who probably had much greater sway over Filbrick. They say a child’s first instinct is to call for their mama. Clearly not in this case!

I’m not saying, here, that Caryn didn’t care about her boys. I elaborate more on her in the meta referenced above, here.

I find it adorable how easily, without any previous prompting, baby Stanley opens up to Ford about his feelings in the comics. The sheer vulnerability of this moment, seeking Ford’s reassurance that he wasn’t a bad kid; the implicit, profound trust, especially coming from someone like Stan, who grows into a man packed to the gills with toxic masculinity due to what he learned from his father. And the manner in which Ford gently comforts him, as if he were used to doing so. As Stan, too, had been shown to do when Crampelter mocked Ford’s fingers. They were clearly accustomed to being each other’s emotional pillars, in the way that kids who learned early on that they can’t count on adults or lean on the authority figures in their lives start building their own little safe space.

The way I see it, the Stan twins got along extremely well, for better or for worse. No obnoxious sibling bickering. No fights and conflict. How could they? They were literally each other’s only friend. If anything, their first major fight was caused by lack of communication, among many other things; they repressed their frustrations with each other to a ridiculous point instead of simply externalizing them like you would expect of an average sibling dynamic.

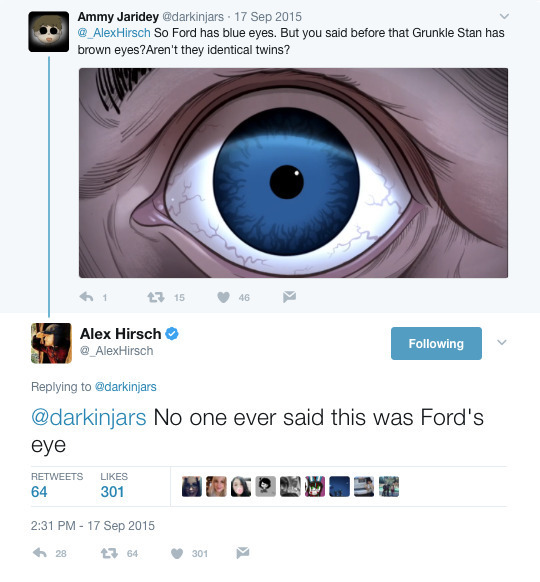

Second of all, they were monozygotic aka identical twins, as strongly hinted in the show, comics, and books, and as confirmed by Alex on the TBoB website, the behind-the-scenes DVD commentaries, and Twitter. The first mention of it, in 2015, below:

They were both named Stan, they had the same face. I’ve read irl identical twins’ confessions about the nature of such a relationship re: identity issues and how people tend to treat you, and it’s often not pretty. In the Stan twins’ case, their sense of identity was beyond blurry, and it’s not difficult to see why. If you pay attention to the show or the comics, you’ll see many hints of this unhealthiness: the way they were both called to the principal’s office (“Pines twins,” even though only Ford was an interested party), the way Stan was called “a dumber, sweatier version” of Ford by Crampelter, the way they had already pretended to be each other before, not in their childhood but adolescence (Stan’s idea, according to hilarious extra material in the DVDs).

Baby Ford, in the comics, has demonstrated a tendency to shoulder the blame that should only be attributed to Stan. For example, when he exclaims, “Oh my God! We killed the Sibling Brothers!” Ford, honey, if anyone had killed the Sibling Brothers, it would’ve been your brother, the person who shoved them in the first place. Not you.

I find it adorable that he also grounded himself for Stan! Filbrick had been very clear about grounding Stan, only, not both twins. But Ford stays with him as if he were grounded as well, as if he didn’t even have a choice. Where Stan was, there was Ford, not far behind.

They were an unit. Inseparable. As simple as that.

Until they weren’t.

The science fair incident happens, of course—and it’s worth noting Ford doesn’t consider the possibility that Stan sabotaged him out of jealousy or envy of his success for even a second! Instead, he immediately assumes Stan broke his machine so Ford would stay with him!

Did their codependency end with their separation, then? I’ve seen many people believing that yes, it did.

But mullet!Stan, now an adult, ten years after his fight with Ford, still resents Ford for not staying with him “forever”:

Not only that, but as Rob Renzetti (who is Gravity Falls’ supervising producer and story editor and the co-author of Journal 3) phrased it in this separate interview by HanaHyperfixates, Ford’s absence in Stan’s life haunted him and shaped all his relationships:

Um, I mean, to me that’s—I mean, really, Stan—Stan’s life has been… it’s been… sad, and lonely, since—he really… his brother was his best friend, and he loved him so, and I don’t think, you know, I don’t think any other relationship ever worked out for him, because of what happened between him and his brother.

And by the end of it all, you get Bill calling Stan “co-dependant” (British Bill?) on the TBoB website:

I know you might think, at first, that we should take Bill’s insults with a grain of salt, since he’s 1) Bill and 2) petty and desperate. But Bill has also a track record of trying to hit where he thinks will hurt the most, and he knows people. His insult here is not an isolated thing either. It might have been easily dismissed, I agree, if not for all the other evidence for the Stans’ codependency that I’m currently showing you. It’s just one proof out of many, just reinforcing an idea that’s already presented quite clearly.

If you’re still not convinced, Alex has revealed in HanaHyperfixates and ThatGFFan’s interview that Ford’s entire character was built around the type of person that could plausibility explain Stan’s neediness:

Ford was very much us building backwards. The same way you know a black hole is there by the light warped around it, it’s like, you know the damage someone’s family has done to them by all of their weird tics and behaviors. So who is the character who would result in Stan being this hurt and needy and mad and also longing?

But Stan’s codependency, imo, was always easier to see than Ford’s, to the point people mistakenly think Stan cared more about Ford than Ford about him. (I’ve dedicated an entire meta to debunking that assumption as well, here.)

In the commentary of Society of the Blind Eye, though, Alex added, referring to Ford and Fiddleford’s friendship:

Ford as somebody who lost Stan is kinda looking for—even though he rejected his brother, he kinda needs, he needs that other person, and he tried to find that in this kinda sweet prodigy and he just pushed him too far.

What Alex said about Ford’s relationship with Fiddleford can easily be applied to Ford’s relationship with Bill and with Dipper, since Ford needs “that other person,” needs to be one half of a duo. Ford has tried to recreate his dynamic with Stan again, and again, and again:

And then, of course, we have Ford’s proposal.

What’s really cool about this first image (below) is that it was drawn before Stan even accepted Ford’s proposal, and parallels their childhood picture in Ford’s pocket (one that, per Word of God, Ford has always carried with him, even before his portal days, as explained here) in a very obvious manner:

Ford was already excitedly fantasizing, drawing fanart of them together, picking their outfits and the name of the boat.

But more than that, he also says:

[...] I think it’s time for the Pines twins to join forces again. At least, I hope so. I haven’t discussed my idea with Stan yet. But if I know my brother, he will jump at the chance to find “money and babes.”

And this, to me, expresses both his hope that Stan would welcome his idea and agree to sail away with him and his almost certainty that it is exactly what is going to happen. Ford does mention Stan’s love for “money and babes,” but do you guys think Ford didn’t know what (or better yet, whom) Stan actually loved? In AToTS, Journal 3, and TBoB’s new canon material, we can observe that same certainty. In all three instances, Ford immediately assumes that Stan will show up and come for his call via postcard with no indication whatsoever that the possibility of Stan declining showed up in his mind.

Alex has also commented, in the first interview I’ve referenced:

Those characters at sea—it was so rich. They’re really really funny, because they both have major major blind spots. I can kinda write stories about them as a duo forever, because you can always excuse them both getting hyped on a bad idea for their own reasons, and then you can always come up with a reason for them to disagree about it, and it’s always sweet to see them come together again, because they’re so full of themselves, but they are also both so damaged they desperately need each other.