Text

The Promethean Watchmen, Part 3: Leading Light

(Image source: https://twitter.com/ponettplus/status/1209092700336787456)

Here we are, the last chapters, 7 through 12. Millions dead in the name of world peace. Security built on a lie. Surely it’s guaranteed to last. Absolutely nothing could go wrong. There is absolutely no way there would be any, oh I don’t know, unintended consequences. But hey, speaking of unintended consequences, I have a trilogy to wrap up here, so let’s get right into it (and once more, the included image is only there for a quick laugh and is not particularly pertinent to anything I have to say).

Starting once more with Doctor Manhattan, we actually see unintended consequences affecting him, rather than he himself effecting them. We learn in Chapter 9 that he only left Earth because Laurie left him, thus severing his only remaining link to humanity. Laurie could certainly never have predicted that her action would have such dire repercussions for the whole planet, rapidly escalating the Cold War into a very-nearly ‘hot’ war. Indeed, it is only because of her that Manhattan returns at all to Earth, breaking the scientific, pragmatic distance he had otherwise enforced while on Mars. It is his keen focus on science that, once more, I also point out as being Promethean-associated. Manhattan is so keen on observing the desolate beauty of Mars that he forgoes practically all other matters. And in this detachment, Manhattan also represents a sort of complement to Prometheus. For, if Prometheus is the creator of humanity, then Manhattan can be seen either as its protector or destroyer, all hinging upon Laurie’s connection to him. Ultimately of course he chooses to be a protector, though not in the way one might expect. In allowing Ozymandias’ plan to continue without revealing it, Manhattan saves humanity from certain nuclear extinction. In the end (ha!), he leaves with one final parallel to Prometheus, declaring to Ozymandias that he intends to create life somewhere else in the galaxy.

Now we come to the man of the hour, Ozymandias, trickster of the world. From his humble beginnings as a rich boy, to his later life as a rich man, Ozymandias spent most of his life looking up to Alexander the Great, a Macedonian conqueror who spread Greek culture all throughout the ancient Middle East and India. It is surely no coincidence then that Ozymandias chose his alter-ego’s name after the Greek name of Ramses II. But, Ozymandias’ parallels to Prometheus aren’t in Greek names and culture alone. To start pointedly, the whole of Watchmen can be seen as an unintended consequence of Ozymandias’ plan. After all, it was his secret island that the Comedian found, which caused him to learn Ozymandias’ plan, which caused Ozymandias to kill him, which caused Rorschach to investigate his murder, and so on and so forth. For being the “smartest man in the world,” even Ozymandias couldn’t have predicted that the Comedian would accidentally discover his plan, and almost cause it to fail. But it didn’t fail. Instead, peace was brought to the world, after they reached an enlightened understanding of the matter. This peace, this enlightenment, could be compared to a fire. Indeed, there was a literal fire when Ozymandias’ plan came to fruition, for how else could an explosion be classified as anything other than a very vigorous fire? And so with the explosion of peace, Ozymandias managed to trick the world into behaving itself, a trick that the trickster Prometheus is known to be would surely applaud at.

Of course, both have other similar correspondences to Prometheus that don’t merit a more full-length analysis. For instance, all three are in prime physical condition. All three have their own ‘secret bases,’ being Mount Olympus, Manhattan’s fortress, and Ozymandias’ Karnak. And of course Ozymandias’ own scientific experiments, creating not only teleportation, but life itself in both Bubastis and the squid creature.

So what final conclusions can be reached, here at the end? Perhaps, very basically, that being a saviour and unintended consequences go hand-in-hand, and that the former isn’t necessarily a good thing, and the latter isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For saving the billions at the cost of millions can hardly be seen as the glorious, heroic thing that the word ‘saviour’ connotes. Likewise, unintended consequences can bring out the best in people, like returning to one’s home to save it because of the simple improbability of life. Watchmen is a deconstruction of how archetypal myths and heroes are seen. Not just the modern superheroes, but the ancient ones as well, such as those of Greek legend. And with the deconstruction complete, the only logical step to take next is a reconstruction, creating new heroes to define the archetype, rather than the old ones that had been the definition to this point. New archetypes to lead the light of reconstruction.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Promethean Watchmen, Part 2

(Image source: https://twitter.com/crd/status/1226288930904997890. And sadly, no, this image doesn’t have any particular bearing on what I’ll be talking about here. I only included it for a quick laugh.)

With Chapters 3 through 6 behind us, it’s time for another installment of “Promethean Parallels and Allusions in Watchmen.” This time, it’s all about the walking nuke himself, Doctor Manhattan. Indeed, Ozymandias largely disappears from the forefront in these chapters, only receiving a couple dedicated pages in Chapter 5. Instead, Doctor Manhattan gets almost all of the limelight, specifically in Chapters 3 and 4. To start with, we learn here that Doctor Manhattan views all of time simultaneously, equally distributed between past, present, and future. It is the future that I want to specifically call out, for Manhattan’s ability to perceive the future thus gives him a certain degree of what we could call forethought. He is able to know and plan for everything accurately, since he’s both lived and living through it all at once. This relates to Prometheus in that his name literally means “forethought.” While he might not be able to see the future like Manhattan, he is still certainly associated with it and takes it into consideration.

The second connection is in how both suffer from unintended consequences. In his myth, Prometheus is punished for giving fire to humans by being bound to a rock and having an eagle eat his liver each day (it could also be argued that everything humans did after he gave them fire, all the good and bad they’ve done, was an unintended consequence, as he certainly couldn’t have predicted everything they’d do after that). Manhattan meanwhile suffers from a variety of different unintended consequences, but the two major ones are from him going back into the I.F. chamber to get Janey’s watch and getting trapped and destroyed in it, and him giving everyone he knows cancer (although this last one is something of a fib on my part, but spoilers). In both Prometheus and Manhattan’s cases, neither of them could have predicted what repercussions their actions would bring on both themselves and the world at large.

The final point is that Manhattan doesn’t experience emotions, at least not extremely, not in the way we experience them. Because of the accident, of unintended consequences, Manhattan lacks that vital human understanding. In that, Prometheus shares a similar fate. As punishment for giving fire to humans, Prometheus is bound to a rock, where his liver is eaten by an eagle every day. It was thought by the Greeks that the liver was where the soul, our emotion, was stored. Thus, Prometheus is left an emotionless husk, not dissimilar to how many view Manhattan. While there are some other minor connections, such as both of them being exiled, both being mutilated, and both being perceived as gods, these were the three major points I wanted to hit upon here for Manhattan.

But, with all that said, Ozymandias isn’t left high and dry in an ocean of nuclear blue. Indeed, there is one notable connection between Ozymandias and Prometheus to be made, and that is that they are both makers. Prometheus, outside of just being associated in recent centuries with scientific progress and endeavor, is the creator of humans, having shaped them from clay. Ozymandias, meanwhile, has created a vast array of things, including but not limited to an entrepreneurial empire and Bubastis. They both have the spark of creation within them, and which led to both of them creating life. But, while Prometheus gave his creations fire, it remains to be seen what Ozymandias does with his creations. (Of course, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Doctor Manhattan is also a creator, creating not only his “fortress of solitude” on Mars, but also being seen doing what can only be described as making “science-y stuff” in a few chapters now, particularly Chapters 1 and 3).

And, just quickly, hey, Chapter 3! On page 10, panel 9, the cab company name is literally the “Promethean”! While a neat reference that I had no idea about until I read it, it does suggest that Moore might have had Prometheus on the mind while writing this story! So these connections I’ve been attempting to draw might have some authorial validity to them, which is neat!

1 note

·

View note

Text

My combination was 4x11x4.

From looking at just purely the comic without text, what I notice particularly is the clear shifts between the way in which Poe is portrayed and the way in which Verne is portrayed. While this of course comes across in the proper comic, the text in the comic drew the eye away from the pictures directly, so that the text was the main point while the art was in the periphery. Now with the art in the spotlight, I notice just how much Poe stands in contrast to Verne. Obviously Verne looks like a child in the way in which he is positioned, but Poe himself looks so much staunch and serious than I noticed before. Dressed in all black with rings around his eyes, he suggests an imposing dominance that is immediately undermined by Verne’s brighter complexion and playfulness. This, combined with the brilliant balloon drawing, strips away any authority Poe has within the comic world, making his seriousness the punchline.

With the title in play, the above point of undermining Poe’s seriousness takes a greater positioning. Now, the joke is very clearly being played at Poe’s expense. Without the context of the original text, the comic-plus-title looks as though Verne is telling Poe to lighten up and stop being so serious, as emphasized once again by Verne’s posturing and the balloon drawing. Meanwhile, Poe’s response in the last panel clearly shows him struggling to come to terms with Verne’s idea of not being so serious, so morbid. Of course, Poe is renowned for his morbid stories, and while I don’t know if Poe himself was as morbid as his stories suggest he is, the way he’s portrayed in popular culture certainly plays him up as being so. So to have someone basically tell him off for being so I find rather funny.

With the way I organized Wilde’s text, I cheated a little and halfway through changed which lines are coming from which comic character, such that lines that belonged to Dorian and Basil, in conversion with each other originally, are now coming out of the same characters’ mouths in the comic, in a way that (in the context of the original passage) it is as though they are having conversations with themselves rather than with each other. While I feel that that misrepresents the original passage, I decided to do it that way so that the comic would flow a little easier and make more sense in reference to the balloon drawing caption (which was what I first put into the comic and then worked backwards from). In changing the meaning of the comic, Poe is now looking solely at a drawing that Verne drew “years ago” rather than a letter plus drawing, implying that, first, they knew each other years ago, and secondly, that Verne is actually in the other room, rather than somewhere else entirely. As such, the friendship Verne sought in the original comic has been achieved in this one, which was unintentional on my part, but I like the symmetry. As for changing the meaning of the original passage, as alluded to above, the shifting dialogue choice I made now makes it seem as though Basil was the one to have lied about destroying Dorian’s portrait, rather than Dorian himself, and now Dorian has discovered that fact. In this way, it creates an interesting conversation about how and what it means for an artist to destroy their own art. If Basil had destroyed the portrait (or at least claimed to have), then would Dorian have become as corrupted and vile as he did? I’d argue no, as whatever vanity Dorian gained from the portrait would not have existed without him continually gazing upon it. And for an artist to destroy their own work (or again at least claim to), then that work must have been something that the artist had become embarrassed or disgraced by, which is something that is reflected in the original passage as well by Basil’s disgust at seeing the portrait. But this re-contextualization suggests a more proactive part that Basil didn’t attain in the original passage. Instead, the art destroyed him. Perhaps that is the fate of all artists and artwork, to destroy the other before the other destroys themself.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Promethean Story in Watchmen

So full disclosure, I read Watchmen about a year ago for one of Professor Raicht’s classes, so I’m going into this with an “old pair of eyes,” so to speak. As such, I’ve given myself something of a challenge to do while reading through Watchmen, that being, to try and discern some Promethean-like qualities from two of the characters, those being Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias. As to what I mean by “Promethean,” I’m using it rather broadly, in that, if I can discern some similarities to the story of Prometheus from either Dr. Manhattan or Ozymandias (such as grasping for high achievements, being punished for that very grasping, and so forth), then it’ll be valid for this mini-series I’m doing for my reading. Right now, I’m only planning on doing two or three of these blogs for Watchmen rather than for each reading assigned, so postings will probably be a bit sporadic in that regard (and I’ll be avoiding spoilers for later issues as well, for what it’s worth, if any other students happen upon this blog and aren’t familiar with the story). (As for why I’m focusing on the Promethean story, I have recently watched The Lighthouse, the ending of which has been compared to the Promethean story, and.... And that’s it, really. Really, it’s just a fun thought experiment).

With that out of the way, now it’s time for the real meat and potatoes. In these first two chapters, not too much is admittedly delved into the lives and history of Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias, but there are some tantalizing tidbits to be gleaned. For Dr. Manhattan, the comparisons are most immediately obvious, as he has godlike powers, and is incredibly intelligent and has a proclivity towards science-oriented stuff. Prometheus is of course a god from Greek mythology (technically a Titan, but same difference), intelligent, and is associated with the quest for scientific knowledge. As for the parallels with Ozymandias, he is seen as the smartest man in the world (according to Rorschach and the Comedian, at least), and has a keen desire to save the world (or, really, if we’re being specific, humanity itself). This of course tracks with Prometheus being incredibly intelligent (as stated before), and attempting to deliver humanity salvation in the form of fire to progress civilization. In terms of the latter component for Ozymandias, this is particularly highlighted in panel 7 on page 11 of issue 2, with Captain Metropolis' dialogue about saving the world being interposed over Ozymandias looking thoughtfully over the burnt map of America. This is clearly supposed to suggest to the reader the inner thoughts of Ozymandias at that moment, showing that he has taken Captain Metropolis’ ideas and words to heart. Ozymandias, his stealing of the fire starts now, in that moment.

Already from just these first two chapters, there seems to be trends emerging in these parallels. For Dr. Manhattan, he seems to reflect the mythological, godly powers of Prometheus, while Ozymandias represents more so the idea Prometheus and his story represents, in terms of striving for the betterment of humanity, regardless of consequences. It will be interesting to see if these trends will track in later issues, or if they either swap positions or otherwise just simply fall apart.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Knowable Unknowability of People

Are we really that complex? I’m sure we’ve all experienced at least one time where someone we know has predicted what we were going to say or do, sometimes eerily so. How could they have read us so easily even when we ourselves didn’t know what we were going to say or do?

This question comes from today’s class discussion of Wilde’s Preface, and particularly what Justin said towards it. Specifically, in referring to how Wilde claims that art is supposed to hide the artist, Justin said something along the lines of that statement being true, as the art only represents a certain aspect of the artist, and can never be as truly complex as the artist themself is. But that made wonder, are we truly that complex, that unknowable, to the point that what we ourselves create is not actually, fully representative of ourselves?

Quite possibly, no, we are not. We certainly have our own complexities, contradictions, moralities, and so forth, I absolutely acknowledge that. But, we are the only people that know each and every single one of these complexities of ourselves. To any outside observer (a critic, one might say), even the ones that know us intimately well, we are only the results of our taken actions, not the debates and haggling we took to reach that result, that outcome. So to the observer, we are fairly predictable, even if we don’t view ourselves as such. It’s just simply a matter of having a large enough pool of data-sets (or results) to pull from and reach a conclusion about. That is what the diagram attempts to illustrate, the complicated internal processes that take place within us all, and the only outwardly visible outcome of those processes: the result.

So by that logic, the art is the outcome of the artist, and therefore must be a representation of not only the internal mechanisms occurring within the artist, but a representation of the artist as a whole. So, if someone were to make a particular judgement about an artist based solely upon their art, then there is a good chance that the judgement might fall somewhere within the vicinity of accurately revealing certain aspects of the artist, rather than concealing them, much to the artist’s chagrin.

But, all that said, I do not actually know if I agree with any of it. I’m pulling something of a Lord Henry, merely saying things and seeing where they land. (Plus, I’m not even really convinced this particularly lands within the technical purview of the blogs to begin with).

1 note

·

View note

Text

While I can’t say I have a favorite all-time picture or image, if I had to guess, this one would probably be somewhere in the top 50 or so. This is a panel from a comic called More than Meets the Eye (specifically issue 44). As may or may not be obvious from the symbol in the lower right corner (depending on your personal pop culture awareness), this is a Transformers comic. While this might dissuade some people from reading it (“Ew, it’s a comic and it’s about a children’s franchise? No thank you”), I emphatically insist that it’s not a story designed to sell toys, or a story that is only aimed at children (although, obviously given the subject material it does appeal to those groups as well). Rather, More than Meets the Eye is a story that puts characters first and foremost, exploring how these people deal with life after the war they’ve been fighting for literally their whole lives finally comes to an end. It deals in spades with themes of (amongst others) regret, moving on, coping mechanisms, and redemption.

I say all of this for the context of what is going on in the image. In this issue, the main characters arrive on a world that belongs to an entity (a caretaker, for simplicity’s sake) that had up to this point been only rumored to exist. By the end of the issue, it turns out that this caretaker turned this world into a war memorial, of a kind. The planet is covered with statues of every Transformer still alive, and at the base of every statue are beautiful blue flowers. Each of these flowers represent a life that that Transformer took (either directly or indirectly), as a way to remind them that they are all killers. Most of the statues are only shown to have a handful of flowers around them, except for one, the one belonging to Megatron (the one pictured). He has fields upon fields of flowers around his statue, each one someone that he killed. Seeing the visual representation of all the lives he’s ended has a profound effect upon Megatron (who by this point had already defected to the good guys), making him directly confront his legacy, and what the war meant. According to Stalin (allegedly), “the death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic,” and now Megatron can literally see this statistic for himself, spread out before him. Because of this, he renounces violence altogether, becoming a pacifist.

I love this image for two reasons. The first is for the sheer impact it has on the main story, especially upon Megatron. The second is just for the idea of it. There’s a beauty in the idea of planting a flower for every life that was taken too soon, of creating something beautiful out of something so tragic. While it’s one thing to simply list names on a wall or plaque, to have each and every life literally laid out before you, there’s a certain power behind it (the same can be applied to battlefield graveyards across the world, such as the D-Day Cemetery). But more than that, attributing each of those flowers, each of those lives lost, to a specific individual, it involves an accountability that simply seeing an ‘average’ graveyard simply doesn’t give you. It reminds you that someone had to do it, someone had to take that life before its time. Every action has a consequence, and these flowers are those consequences.

1 note

·

View note

Text

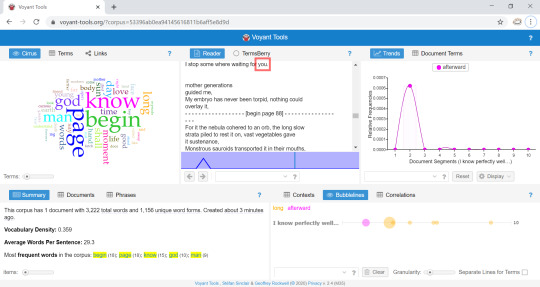

Information overload comes to mind, looking at this website. Even at just twenty-two pages (encompassing pages 82-100), there is so much to look into and discover that it seems impossible to discover it all in just one sitting. The main emphasis of the website seems to be visual representations of data, and moreover not limited to just the standard graphs one might expect. Instead, the website displays its various data points in a variety of unique manners, such as bubblelines, cirruses, and collocate graphs. One of the more interesting statistics present on the site is the list of frequency for the words present within the text. I would not have guessed that “know” appears fifteen times within the selected text, while “honoring” only appears once. That said, I also would not have guessed the steep dropoff for repeated words. By this, I mean that I would have thought that there would be more words that appeared more than once within the selected text than what there ended up being. This changes the way I see the poem by giving me a way to see the poem in a three dimensional manner. What I mean is that I can see certain trends represented that I never would have noticed by simply just reading them (such as that “know versus honoring” comparison). Given more time, and with analyzing the whole text, I am sure that deeper insights could be gained in comparing and contrasting the trends of which words appear not only how much, but where as well.

1 note

·

View note

Text

One meme that comes to mind from recent times is Spongemock. What personally interests me in this meme (at least in an English major-y way) is the way in that, by only looking at the image of it, without any accompanying text, almost everyone can not only picture the exact font that goes with it, but also the voice that goes along with it: cartoonishly overblown and a bit nasally, like if a goose could talk. That’s something that deeply fascinates me with the Spongemock meme in particular, as most other memes, especially as they have evolved in recent years, usually only focus on a simple set-up and punchline format, without any special text or voices associated with them. Yet Spongemock pulls the double whammy of using both, to marvelous effect. The joke of Spongemock is that, someone, perhaps an authority figure like a teacher, will make a statement or demand, and then the receiver of the statement or demand WiLl PaRrOt BaCk WhAt ThEy SaId, LiKe ThIs, indicating a mocking tone. The image of Spongebob further reinforces the mocking nature of the response. (Also, as a quick aside that I want to just throw out there, in the process of doing this homework assignment, I came to realize that the Spongemock meme can be seen as an early form of the “ok, boomer” meme that has come along more recently, which I at least think is a neat connection.)

The process of finding a line to fit the meme made me both overly critical of the poem, and also somewhat embarrassed about the way in which I was representing it. To the former, as I was going through the poem, I was intently looking for lines that would be inherently mockable (per the meme I used). As such, I was more just looking for lines that, in a void, would basically make Whitman look like a fool (to put it gently). However, once I decided on my line and put it into the meme, I had a pang of regret, because, yes, in a vacuum, the line I chose sounds bad (an “ok, boomer” type of moment), but within the context of the poem itself, it doesn’t nearly have as bad a connotation. Instead of being vain and narcissistic as the meme makes it seem, the poem presents that line as being something of a celebration, of recognizing one’s own worth. So, to misrepresent that line, it felt slimy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the things that Google Maps leaves out is a sense of perspective. There isn’t a sense of height to the trees, or that there are hills all around the selected location. If someone were to only look at their map, they’d think it was just a fairly flat area with some not-so-big trees, when that is far from the case. One thing that the map includes that mine doesn’t is a pool, which means that this map was taken a few years ago. I know this because we had to take down the pool after ice crumpled some of the sides of, back in 2018 or so. In that sense, my map is more up-to-date than the Google one. One thing that both maps omit is a small trail that leads into the forest right next to my house. For Google, the trail is too small and the trees too densely packed to be able to pick it up. Meanwhile, I didn’t include it in my map as it didn’t occur to me to do so. This is significant as it shows that maps are representative of not only selective observance, but also selective remembrance. If something isn’t observed, then it won’t be on a map. But, if something isn’t remembered, then it will also be omitted. Thus, to someone unfamiliar with the area, they still wouldn’t have a completed picture of the location, possibly leading to discrepancies later on.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Life in Oswego. Oswego, New York. 2020

Description: Life in Oswego encapsulates both the #solitude and community that can be found in the city of Oswego. Using a combination of #nightlife and #naturalviews present in and around Oswego, a #peaceful view is created of city life meeting natural wonders.

3 notes

·

View notes