Social history, cultural history, art, architecture and whatever else I find interesting!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Creating a Legend: Grace Darling and the Victorian Public

Her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography begins “Darling, Grace Horsley(1815–1842), heroine” and it is as a heroine that she is remembered. However, the myth-making of the national media that followed her heroic act seemed intent on making her a legend. In reality, the attention it generated made her a virtual recluse and prompted, in later years, a move by her family and close friends to reclaim her image and record the truth of a modest and humble young woman and her remarkable deed.

In the early hours of 7th September 1838, this lighthouse keeper’s daughter, just 22 years old, would take part in a courageous rescue that would transform her unwillingly and unexpectedly into a national hero and celebrity.

During an attempt to navigate a ferocious storm on the night of the 6th September, the steamship Forfarshire carrying 63 passengers on their way from Hull to Dundee, ran into rocks submerged beneath the waters around the Farne Islands, catastrophically sinking and drowning most on board.

Grace had awoken during the storm, unable to sleep. While watching the storm from her window in the lighthouse she was fortunately able to make out the shape of the Forfarshire on Big Harcar rock where it had been shipwrecked. She woke her father William but neither of them thought they could see any survivors on the rock. By 7am, however, it was light enough to make out the shapes of survivors moving on the rock. Believing that the seas would be too rough for the lifeboat from nearby Seahouses to set out, Grace and William bravely rushed out in their small wooden coble boat to row almost a mile in the storm to rescue the few survivors who remained after the horrific wrecking. As William set foot on the rock, Grace rowed alone to steady the boat before they returned with the first boat-load of survivors to Longstone.

The story quickly made the national press and reporters arrived at Longstone. Grace became their main focus and was portrayed as the star, often at the expense of her father William’s efforts. Although Grace’s efforts were admirable and heroic on their own, journalists began to sentimentalise the story into a romantic adventure, even to the point of simply making things up (such as a story of Grace having to plead with William to launch the coble to save the survivors, or that Grace heard the cries of the survivors on the rock during the night – impossible at the distance from the wreck to the lighthouse, especially through the howling wind and lashing rain). The rescue had happened at a time when national newspapers were beginning to move towards the publishing of more sensational stories to attract ever more readers.

Grace was already ripe to fit the role of a Victorian heroine and the myth-making of the newspapers, embellished her story to make her fit it perfectly. She was young, eligible and beautiful (not to mention possessing a gift of a name for a romantic heroine). Also appealing to Victorian society was her dutiful devotion to humble, domestic life supporting her family. Grace was promoted as a heroine and role model to young women across the nation. Selfless, pious (Grace was deeply religious) and devoted.

As the rest of the nation became aware of her actions, she received numerous accoladesand much attention.Initially encouraged by William, she had her portrait painted several times. However, after only five weeks, so many requests were made and so much time had been spent sitting for portraits that William told any further artists to take their likenesses from the pictures already made of Grace. According to William there had been seven sittings in just twelve days. Grace was becoming a living legend. Without asking for it the publicity began to create an unnatural level of attention and admiration for her.

Grace was obviously admired for more than just her good deed too. She was seen as an eligible, attractive young woman, her beauty being talked up in the re-telling of the rescue story. Quite clearly many well-wishers felt a passionate romantic attraction to her, sending her clothes (such as fine silk shawls). Some letters simply requested that she kiss the paper and return it. Admirers wrote requesting locks of her hair and pieces of the clothes she wore during the rescue and she even received several proposals of marriage. She initially received this attention with good humour and felt obliged to reply to all letters from well-wishers. Letters and presents, however, kept on coming as did visitors who would turn up on Longstone uninvited to glimpse or meet the famous young heroine.

In one incident, W. Batty, a circus owner from Edinburgh wrote to Grace, sent money (the proceeds of one of his shows) and suggested she visit his circus to thank the people of Edinburgh for their donation. When she politely wrote back thanking him and the people of Edinburgh and saying she would indeed visit, Batty published the letter in the local press advertising Grace’s imminent appearance at his circus. The society ladies of Edinburgh, however, were outraged and wrote to Grace explaining how Batty’s money was not from the people of Edinburgh (they were separately raising money for her) and that in fact, her appearance at his circus, shown off as just another of Batty’s attractions, would appear crude and would greatly damage her respect and reputation amongst the people of Edinburgh. Grace was horrified that she had been tricked by Batty and the incident greatly upset her. Further anxiety and anguish followed when large crowds gathered to look at her when she made a private trip to Alnwick to collect a reward sent by Queen Victoria in recognition of her heroism.

Soon after these incidents, the Duke of Northumberland who had taken an interest in the Darlings long prior to the rescue, offered to act as a guardian for Grace, handling the continuing requests and protecting her from further exploitation. Despite this, the attention was unceasing. Images continued to be reproduced of Grace and products and souvenirs to be sold with her name and image attached. Her image appeared on books, postcards and plates, adverts for soap and even on Cadbury’s ‘Grace Darling’ chocolate.) When she was offered money to appear as herself in a play about the rescue she refused although the play went ahead anyway.

Grace’s anxiety continued to increase as did public demand to see her but she now wanted to live the life of a recluse with her family, not wishing to meet other people. She suffered from terrible nightmares about being watched constantly. Adding to her anxiety was the belief that she was not a heroine, rather that the rescue was an act of God. She felt undeserving of the attention and praise she received. While some admirers thought of her as an angel she felt, as she had always been, simply a lighthouse keeper’s daughter. Grace refused all requests for appearances in public (even at a charity event in Hull, where the Forfarshire had sailed from, attended by Queen Victoria) and eventually she stopped replying to letters altogether. This only added to her feeling of guilt.

Her acute anxiety, causing her to eat less and remain hidden indoors, had begun to weaken her. When she caught a chill in 1842, it quickly worsened to the point that she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was moved to her sister’s house in Alnwick. On the evening of 20th October 1842 at the age of just 26, Grace died.

Grace’s early death, just four years after the incident which had made her famous, sealed her legendary status, forever preserved unspoilt in people’s memories as a young heroine. Only in 1880, after at least two popular books cementing the sentimentalised legend and poems by William Wordsworth and A.C. Swinburne, did Grace’s sister Thomasina publish Grace Darling: Her True Story, using Grace’s own letters in an attempt to correct the fictitious accounts. However, the true story proved less popular than the legend and went largely unacknowledged at the time.

Such revelations about Victorian myth-making may make us regard the ‘legend’ of Grace Darling with some suspicion or disappointment but even when we separate the facts from the fiction, the actions of Grace and her father were truly heroic and carried out at great risk to their own lives. Even the sensationalised version of Grace’s story played a positive role in raising the consciousness of the general public with regards to the dangers of the sea and the need for better lifeboats.

Her story helped publicise the need for an organisation like the RNLI and for lifeboats to be stationed in many places along the British coast. Her name is synonymous with the organisation today who still name boats in her honour and who run the Grace Darling Museum in Bamburgh, Northumberland where Grace’s dress and the coble used in the rescue are housed.

(http://rnli.org/aboutus/historyandheritage/museums/Pages/Grace-Darling-Museum.aspx)

Today, Grace is still famous and in Northumbria particularly, she is remembered with great affection and admiration where plays are still produced in her name and the possibility of finding a family connection to the Darlings still draws people to local family history workshops.

Her story had been quickly romanticised and made into modern legend. This has the unfortunate effect now on making us view records of the event and of the heroism of Grace subjectively. To combat the myth-making, we may feel the need to counter some of the stories that have been told. Re-assessing the known facts, however, it seems that even though William Darling’s honourable and courageous efforts were overlooked by the myth-makers of the time, Grace remains a heroine, if a reluctant one in her lifetime. Her own courage and sense of duty cannot be doubted. History records her name and continues to make us seek out the truth behind the events that made her so memorable.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Xmas Wishes 1940"

“Already the future historians are fastening their gaze upon us, seeing us all in that clear and searching light of the great moments of history.”

J.B. Priestley, Postscriptsradio broadcast, Sunday 30th June 1940

I came across this quote a few years ago when researching the British Home Front during the Second World War. It’s taken from one of J.B. Priestley’s wartime Postscriptbroadcasts, his series of weekly radio broadcasts to the nation after Sunday’s nine o’clock news running from June until the end of October 1940. Priestley’s broadcasts were hugely popular (heard by an estimated 40% of the adult population), arguably making his broadcasts as influential as Winston Churchill’s speeches. Indeed, the popularity of Priestley’s Postcripts was such that there was sufficient demand for a book to be published, transcribing his broadcasts late in 1940 (just in time for Christmas!).

A few years ago I was lucky enough to chance upon a first edition of Postscripts in a charity shop. An even nicer surprise, when I looked inside, was that the book bears an inscription on the first page which reads “Xmas wishes, 1940”. The inscription gives the book itself a little connection to history. It was a Christmas gift given at the end of a year which had seen the evacuation of Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain and the Blitz, all of which are described in the book which transcribed Priestley’s weekly radio broadcasts as these events unfolded.

That Christmas of 1940 is considered the first ‘real’Christmas of the war by some. In Christmas 1940 the war had been brought to the home front in a way it hadn’t a year earlier. The blitz was still ongoing. Bombing had killed 24,000 people by the end of the year and made many more homeless. As a result, many families were likely to spend a certain amount of time in air raid shelters over the festive period and so they decorated them for Christmas. Britons were determined to celebrate Christmas regardless of the war and tried their best to make it ‘business as usual’.

Continuing as usual was a tall order, however. The nation was tired, over-worked, fearful of bombing and anxious for those overseas. Many children were evacuated, separating some families even further. As supplies and transport links were over-stretched, travelling over the Christmas period was discouraged (although not wholly effectively with family members still making journeys to be together).Many, however, were determined to make the most of the situation and have a good time whilst they could, despite the shortages, difficulties and tragedies brought by the war.

With rationing in-force, Christmas dinners would have been somewhat sparse and particularly ingenious. Saving up meat rations made things a little easier, but turkeys were still unaffordable and so people sought out reasonable substitutes. Home-reared chickens or rabbits were possible options, and home-grown vegetables could be sourced without too much difficulty. Tea and sugar rations were increased in the week before Christmas, which certainly would have helped lift Britons’ spirits but limitations on many traditional cake ingredients meant that Christmas dinner was often followed up by something a rather more subdued than a flaming Christmas pudding.

As Britain was still under threat from bombing, gifts to take into the air-raid shelter were popular such as flasks and blankets and even toy gas masks for dolls. The public had been encouraged to spend money on the war effort (largely through war bonds) rather than on gifts and consequently this sparked a rise in home-made presents. Likewise, home-made decorations such as tin baubles and paper chains appeared in the houses and air-raid shelters of Britain.

Across Britain, shelters were decorated and public shelters became unofficial community centres for Christmas celebrations. These were primarily for children (in parts of London, some tube commuters had donated money to throw a party for the children sleeping in the underground stations) but these parties also acted as an excuse for adults to have a little something to drink and (if the shelter were big enough) to play music and sing.

Although the government may have preferred to promote such defiant high spirits across the nation, the public wanted Christmas 1940 to also remain a time for sentimentality and reflection. Accordingly, the BBC broadcasta poignant sermon from the ruins of the bombed Coventry Cathedral and its ‘Christmas Under Fire’ programme interviewed soldiers overseas.

Between 24th and 27th of December, the British and Germans both unofficially halted their bombing campaigns. Although they would resume with ferocity before the end of the year, this marked a brief period of respite towards the end of a turbulent year. It became a time for reflecting upon those lost and those away overseas.

For the person who gave this copy of Postscripts as a present and for the person who received it, this book documented a very recent passage of history – that of just the previous 6 months. Today and to us, it is a recollection of one of the most significant periods in the national memory of the twentieth century. It’s a gift from one person to another at the end of what “future historians” would see as one of the most significant years in modern British history. It is also a reminder of the continuing day-to-day life of individuals during the war - individuals carrying on with their lives, celebrating Christmas and taking a brief moment to pause and reflect on the history that had just been made.

#Christmas#Christmas 1940#1940#1940s#WWII#World War Two#British History#Home Front#Wartime Christmas#Postscripts#J.B. Priestley#Priestley#The Blitz#Air-Raid Shelters#Christmas Dinner#Christmas Decorations#Xmas#Second World War#Rationing

1 note

·

View note

Text

Coping with the Blackout: Britain 1939-45

© IWM (Art.IWM PST 15157)

The blackout had been ordered as part of the British government’s fears that bombing of the civilian population would start immediately upon the declaration of war. Any aids to the navigation of enemy bombers were seen as a severe threat. This included all lights in the country, whether in the city or countryside, which could have highlighted landmarks, buildings, roads, railway lines – all vital to guiding the Luftwaffe to their intended targets.

These strict restrictions on lights showing in the street were enforced by ARP wardens. Those who didn’t comply were reported to the police. Additionally, because the blackout would only be effective if it were total, any non-adherence of the blackout regulations affected the whole community and so members of the public would ‘police’ each other to ensure that regulations were met and all of them remained safe.

People largely had to make or provide their own blackout materials, improvising with cloth, card, paint and paper. Some bigger establishments had problems blacking out because of their size and so opted to brick up large amounts of their windows (a method which not only aided blackout precautions, but also protected against bomb damage).

Light levels were kept low in many public areas including in train stations and onboard public transport. Inside train carriages, passengers strained their eyes to read in the dim blue lighting demanded by blackout regulations.

This ‘blackout light bulb’ was used in Brighton train station to ensure that light levels were kept to an absolute minimum. (© IWM (EPH 4583)

Any unnecessary lights indoors were turned off and what lights remained were usually kept deliberately dim. A seventeen year old girl in Romford writing for the Mass Observation project recalled the first few days of September 1939, when the blackout began.

Friday 1st September – “...our makeshift blackout arrangements involve the use of a light so small that it strains the eyes. It’s only ten but I’m going to bed.”

Saturday 2nd September – (Walking home from the cinema) – “We could see nothing at all, except the buses which were half-lighted. I couldn’t even see my companion. There were a good few people about – we heard them.”

Some people stayed inside, afraid to go out. Others, however, felt compelled to leave and escape the dim, claustrophobic conditions of their blacked-out houses. Again, from the same girl in Romford.

Sunday 3rd September – “I decided we could not stop indoors; the blackout curtains made the rooms stuffy, and the light bad. We went into the town ‘to see what was going on’... Evidently, others had come out for similar reasons, so every street corner was ornamented with little groups of people...”

Pedestrians often became lost in the darkness, especially if setting off before their eyes had adjusted to the dark. Without a torch, people could only see a few paces in front of them. Tripping over kerbstones, falling into the road, and having to feel your way along buildings are all experiences recorded in memoirs of the time.

Although people acknowledged the danger lights presented, the blackout regulations were unpopular and initially people were reluctant to go along with them. At the beginning of the war, particularly as the inactivity of the ‘Phoney War’ became a familiarity, many people perceived the blackout primarily as a nuisance. In the mind of some, the blackout seemed more dangerous than the enemy bombardment it had been intended to prevent. Even without bombers venturing into British skies, by the beginning of 1940, 4,133 people (2,657 of whom were pedestrians) had died in road accidents largely attributable to the dangers of the blackout. Amidst the darkness, people fell into lakes and rivers and there are reports of dockworkers being drowned when knocked unseen into harbours by the cranes they were working alongside. Despite the dangers however, regulations stayed in place (the dangers of an illuminated, clearly visible bombing target remained an even greater threat) and, as a consequence, various ideas were suggested to help people stay safe.

One of the most immediate dangers of the blackout was the risk of accidents involving unseen traffic on the roads. Headlights were still permitted but had to be shielded so that only a small beam of light shone down on the road below. White paint was required on the bumpers and mudguards of vehicles and a large white dot was placed on the back of all buses. White paint was also used around the doors of tube trains in London.

Hooded headlamp cover, © IWM (D 2749)

To aid traffic, white lines were painted in the road to direct their flow. (Road markings today are a legacy of these measures.) Kerb stones also had strips of white painted on to highlight them. For pedestrians willing to take a risk, the white lines in the road provided an easier form of navigation than groping along the side of the street. Consequently, in less busy areas, some people could be found walking dangerously in the middle of the street using the road makings to find their way around.

The Imperial War Museum has a fantastic collection of images, taken by photographers from the Ministry of Information, showing blackout accessories on sale at Selfridges in London. By 1940, these included white coats, collars, luminous badges and luminous armbands. They sold luminous adhesive tape to add to clothing, even luminous pin-on flowers and walking sticks with a light that shone out of the tip to identify their owner and to illuminate whatever they were about to step in to. All were aimed at aiding pedestrians and making them more visible to vehicles and each other in the darkness.

A woman tries on a luminous flower button-hole, Selfridges, London, c1940- © IWM (D 77)

Luminous badges could be pinned to coat lapels - © IWM (D 72)

Walking sticks with a light in the tip were one of several blackout ‘gadgets’ - © IWM (D 68)

Not just pedestrians but animals also were catered for in the Selfridges blackout range. If your dog didn’t have a gleaming white coat naturally, you could buy one for it. Elsewhere, one farmer in Essex took to painting white lines on his cattle in an attempt to avoid night-time collisions with traffic. (Selfridges, unfortunately, didn’t cater for cattle.)

The toy dog appears to be the only one not struggling to hide an embarrassed smirk in this photograph of a Selfridges shop assistant ‘modelling’ a blackout coat for dogs. - © IWM (D 66)

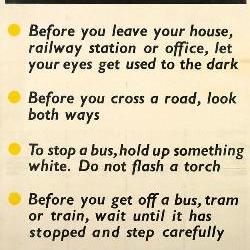

Aside from the special luminous items being produced for sale, wearing or carrying something white was encouraged and suggestions included handkerchiefs, buttonholes, handbags and un-tucked shirt tails. Even simply carrying a white envelope to help flag a bus down was encouraged especially as it was considered greatly preferably to dazzling bus drivers with bright torchlight to attract their attention.

Torches, initially banned, were eventually permitted if masked by tissue paper but batteries were in high demand. As part of the restriction, torches had to be pointed down at the ground, only to illuminate your next few steps ahead.

Torches were eventually permitted but had to be shone only on the ground. - © IWM (D 367)

Policemen would wear white gauntlets to help direct traffic. They also made themselves more visible by covering some of their uniform (including capes and tunics) in luminous paint. Sales of fluorescent paint increased as it was also used by homeowners to help identify their key holes and bell pushes.

Government poster campaigns gave practical advice on staying safe in the blackout and today they provide an interesting insight into what the experience of the blackout was like, and what dangers it presented.

Posters such as “Wait! Count 15 slowly before moving in the blackout” were aimed at keeping people safe during the blackout, suggesting that when they step out of a building they allow their eyes time to adjust to the minimal light conditions before moving. The darkness had increased accidents dramatically and by January 1940, a poll suggested that one in five people had been injured due to the blackout.

Those issuing the posters were seemingly concerned about the complacency of some members of the public. Posters were issued warning people to ensure that their buses, trams and trains had stopped before they alighted. Posters warned “In the blackout: Watch your step: Don’t alight from a moving bus”, similarly “In the blackout: Before you alight make sure the train is in the station. Look for the platform.” and worryingly, “Although the door you’ve opened wide – make sure it is the platform side”.

Posters didn’t just warn against unseen dangers, they also gave practical advice such as advising people to address letters and packages that they sent through the post with clear handwriting written on white labels to save people having to use torches and lights to read labels at night.

As the war progressed, some of the blackout restrictions were gradually eased. By Christmas 1939, the blackout period was shortened slightly and certain establishments were allowed some dim exterior lighting unless an air raid was signalled. The clocks were put forward one hour in February 1940, and ‘British Summer Time’ remained in place from then on. In May 1941, “double summer time” was introduced, making it light until late at night. In September 1944, with the threat of German military action against the British Isles reduced, the blackout was replaced by the ‘Dim-out’. New regulations allowed a limited amount of light no brighter than moonlight and in April 1945, blackout restrictions were fully lifted one more after over five years.

People realised the benefits of the blackout (or at least the threat of not blacking out) and, notably, most posters issued about the blackout were providing safety tips for coping with the new conditions rather than arguing to persuade the public of their necessity.

Frustrated and panicked however, pedestrians were left confused and often frightened in the darkness of the blackout for over five years. In the countryside, walking around in pitch-black darkness was not an uncommon experience but for those in the cities (particularly those who had grown up used to street lighting), it was difficult, dangerous and unfamiliar. Some found it an exciting adventure, but many feared the darkness.

The practical advice given to people, the items sold and the methods used during the blackout helped ease their anxiety and confusion. With the down-pointed torch, the white markings in the road and the faint glimmer and glow of white and luminescent paint, Britons managed to spend their wartime nights outside in relative safety and with the realisation, with faintly glowing figures around them, that they were not experiencing the war alone.

Notes on sources

Amongst the sources consulted, great information on the blackout is provided in Gardiner, Juliet – Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 – Headline Book Publishing – (2005)

The Mass Observation quotes are taken from Sheridan, Dorothy (ed.) – Wartime Women: A Mass Observation Anthology 1937-45 – Phoenix – (2000)

Images

All images are courtesy of the Imperial War Museum. Used under the terms of IWM’s Non-Commercial Licence. Details can be accessed at http://www.iwm.org.uk/corporate/privacy-copyright/licence

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rupert Brooke and the Neo-Pagans

“I was, for the first time in my life, a free man, and my own master! Oh! the joy of it! ... And all in England, at Eastertide! And so I walked and laughed and met a many people and made a thousand songs...”

In the Easter Holidays of 1909, the poet Rupert Brooke had embarked on a small tour of south western England. In Devon, Cornwall and the New Forest, he walked, exercised outdoors, and swam naked in the streams and rivers, meeting various friends along the way, each of whom were eager to live a liberated Bohemian lifestyle. He had encountered these new friends largely through his social activities as a student at Cambridge University and they were, at the time, those who were closest to him.

In a short period between 1908 and 1912 this group of friends were privileged enough, or perhaps unfortunate enough, if certain accounts are to be believed, to know Brooke more intimately than almost anyone else in his life, to see him attempting to live the life he so desperately desired.

How and why had this group come together, who were they, what did they mean to Brooke and can they help us understand a little more about him?

THE FORMATION OF THE ‘NEO-PAGANS’

The group was a combination of Brooke’s socialist acquaintances at Cambridge University (including fellow members of the Fabians, the Cambridge Apostles and the Marlowe Dramatic Society), friends such as Justin Brooke and Jacques Raverat who had experienced a modern, progressive education at Bedales School (itself, an important influence on the philosophy of the ‘neo-pagans’ as Brooke’s friends would come to be known), and like-minded friends such as the Olivier sisters whom he encountered outside of university life.

Rupert had experience a strictly conformist upbringing raised by his puritanical mother who, having lost a child before Rupert’s birth, mothered him intensely. Prior to attending Cambridge, Brooke had undergone a traditional education at Rugby school, where his father also taught. As he came of age, Brooke found his family life increasingly suffocating, desperate as he was to live an independent, liberated life. At Cambridge, he was finally able to begin meeting friends, male and female, away from the gaze and judgement of his parents.

Although the idea of living a ‘back to nature’ lifestyle had been forming in Brooke’s mind for some time, it was the Olivier sisters who were the catalysts in helping Rupert put these ideas into practice. A significant group in their own right, these four sisters brought the experience of their liberal upbringing to the group. Encouraged by their parents, they lived a liberated, outdoor life, walking, climbing, even killing and skinning rabbits. They were the living embodiment of the liberal philosophies Brooke had read about but never quite experienced in his life so far.

Brynhild was the first of the four Olivier sisters that Brooke would meet (and fall for) and who would form an influential part of the core of his group of friends. In the Christmas Holidays of 1907, Brooke was part of a group of twenty-eight who travelled to Switzerland. One of his fellow travellers was Brynhild Olivier. Like other new friends of Brooke’s, the Oliviers had been exposed to a new bohemian culture and the youngest sister, Noel, was still a pupil at Bedales.

Brooke’s loose group of likeminded friends would become known as the ‘Neo-Pagans’ – a name given to them by one of their occasional ‘members’ Virginia Stephen (later Virginia Woolf). They would meet to practice a liberated, bohemian, outdoor life influenced by some of the most progressive thinkers of the late Victorian era.

INFLUENCES

Perhaps the most important single figure to inspire the bohemian lifestyle of the Neo-Pagans was Edward Carpenter. Carpenter was an extraordinary figure in Victorian Britain. A socialist of diverse tastes and interests, he had been a Fellow at Cambridge but had resigned this post to live with working class communities further north. He lived in the village of Totley on the rural fringe of Sheffield, South Yorkshire before later moving to Millthorpe, Derbyshire where he lived a largely self-sufficient lifestyle (his writing being his only source of income) and, rather like Brooke would later do at Grantchester, he spent much of his time outdoors, sunbathing and swimming nude in the river which passed through his garden. Carpenter detested the urban lifestyle even to the extent of designing and making his own pair of sandals to replace his shoes (or ‘leather coffins’ as he called them). Carpenter believed that the rigid codes of bourgeois society should be dispensed with. Simple clothing, self sufficiency and open and frank discussions about relationships and sexuality, he believed, would open the door for the advancement of society.

Carpenter was in his eighties by the time Brooke and his friends took up the neo-pagan elements of his philosophy but he had been highly influential particularly to young Cambridge students who visited him in the north, lured by the myth of this rebellious ex-Fellow. Two of these students, Goldsworthy Dickinson and E.M. Forster, would go on to be dons at Kings College during Rupert Brooke’s days there. Carpenters ideas also permeated through to Brooke in a more indirect way as he had also been a significant influence on J.H. Badley the founder and headmaster of Bedales school.

Formed by Badley in 1893, Bedales was a progressive school promoting a liberal, back-to-nature philosophy. Unusually for its time, it was a co-educational school and encouraged ‘comeradship’ between its male and female pupils. The politics of Edward Carpenter and William Morris had inspired a school in which ‘New Life’ socialist ideals mixed with the cult of the body beautiful and an emphasis on the benefits of outdoor life. Consequently, the curriculum emphasised arts and crafts, folk culture, manual labour and outdoor pursuits like climbing, walking and swimming. This stood in stark opposition to the traditional conservatism of Brooke’s own education at Rugby. From this school would spring several of Brooke’s friends whom he encountered during his Cambridge days and on his Neo-Pagan trips, and a philosophy that would resonate with his own developing ideas and his desire to break out from the constraints of his own upbringing.

THE BOHEMIAN LIFE

It is useful to remember that the Neo-Pagans were not a club or an organisation. Indeed, they never defined themselves as ‘Neo-Pagan’ (Virginia Woolf’s term described her friends such as Rupert Brooke and Ka Cox, and we’ll use it here to refer to this loose group of Brooke’s close friends). Despite the socialist backgrounds of several of the group who were members (or the children of members) of socialist organisations, Neo-Paganism wasn’t a political movement. It had no manifesto or fixed membership, and the political ideals of the group were broad and expressed largely in their social activities which were limited to their own small circle of like-minded friends rather than being promoted to others. It was just one of many small sub-cultures that belonged to a much wider culture of bohemianism permeating cultural and intellectual circles in the early twentieth century.

Away from the group, most of the friends continued to live in a bohemian ‘back to nature’ way as a matter of course, a lifestyle. Brooke, especially, incorporated long walks, sleeping out in his garden, and nude bathing into his regular routine at his house in Grantchester regardless of whether he was with his Neo-Pagan friends or not. Virginia Stephen’s visit in August 1911 saw the pair swimming naked together and lounging in the sun in Rupert’s back garden where he is said to have asked her to suggest images and phrases for the poetry he was writing.

Outdoor pursuits such as climbing or hiking formed the majority of activities undertaken by the friends. For many, their upbringing and education had stressed the importance of nature and fresh air. For Brooke, an enjoyment of the beauty and tranquillity of the natural world was further combined with his need at the time to live an independent life.

Becoming a ‘wild rough elementalist’, as Brooke claimed he was doing in 1908, meant that a simple outdoor life was actively embraced. Influenced by the Oliviers, particularly Brynhild, trips with his neo-pagan friends would involve escaping to rural environments and often camping, in an attempt to be closer to nature and to learn more about it.

Writing to his cousin Erica in 1909, Brooke spoke of his new life claiming that “[I] wear very little, do not part my hair, take frequent cold baths, work ten hours a day, and rush madly about the mountains in flannels and rainstorms for hours. I am surprisingly cheerful about it – it is all part of my scheme of returning to nature.”

This close physical association with the English countryside would also infuse Brooke’s poetry. Like others of his generation, he embraced pastoral, idyllic images of England as a way to capture a beautiful, peaceful, reassuringly unchanging and unchanged image of a nation and landscape that had been rapidly changing because of industrialisation. Tellingly for Brooke, ‘mother nature’ also offered reassuring comfort.

Wild swimming seems to have been a particularly important and central tenet of Brooke’s Neo-Pagan lifestyle. He literally immersed himself in nature and the English countryside swimming regularly in the river (the River Cam or Granta) and the streams and natural pools near his home in Grantchester. Swimming, above all other neo-pagan activities, provided him with an opportunity to escape from a frequently complicated and troubling personal life back into simple, innocent nature.

Swimming served many functions for Brooke. It was partly cathartic; plunging into the cold water provided him with a sudden, purifying shock when he felt the need to feel clean both literally and mentally. Additionally, its ‘pure’ nature could lend a sense of innocence to Brooke’s sexual desire on the occasions when he bathed naked with friends he felt a deep sexual attraction to. Ultimately for Brooke, swimming symbolised the pure, innocent, natural world and life. His passion for it as physically and mentally cleansing would continue, surviving the break with his Neo-Pagan friends which was soon to end this short-lived mini-utopia.

Despite the seemingly liberal attitudes of Brooke and his friends to nudity and the body, the general philosophy of the Neo-Pagans (as taught by Carpenter and his followers) promoted chastity. At Bedales school, associations between sexuality and the body were played down. Healthy bodies were actively encouraged but sexually active ones, not so. For Brooke and others their Neo-Paganism was a celebration of purity and youthful innocence. Neo-Paganism may have bucked most of the social trends of Victorian and Edwardian Britain but sexual liberation still remained beyond the pale for many, especially for those who shared a respectable upbringing like Brooke’s.

However, it seems the lines were often blurred for the members of the group including Brooke who despite his underlying puritanical aversion to sex (and female sexuality in particular), frequently found himself drawn to the girls he socialised with.

During this period, Rupert alternated between two distinct and troubled relationships, one with Noel Oliver and one with a mutual friend of his and Virginia Stephen’s, Ka Cox. His relationships with both girls were complex and not always relevant to the story of the Neo-Pagans but a brief explanation here will help, especially as his relationships with these girls play a significant role in the break-up of the Neo-Pagan circle.

Rupert had met Noel, along with the other Olivier sisters, through his friendship with Brynhild Olivier. Noel was several years younger than Brooke and was still attending Bedales school when she met him in 1908 at a Fabian Society dinner, aged 15.

To Brooke, Noel embodied purity and youthful innocence. He quickly became obsessed with her, writing to her regularly. Noel, however, did not return Brooke’s impassioned affection. She remained aloof. With Noel still attending Bedales, Rupert could see her only rarely and the Neo-Pagan gatherings offered him a much longed-for opportunity to do so. Brooke’s mother had a deep suspicion and dislike of the free-thinking Olivier girls but she wasn’t the only figure intent on keeping Rupert away from Noel. Her elder sister Marjory was also suspicious of his intentions, taking issue with Brooke personally over his love letters to Noel and keeping her away from him as much as possible.

Frustrated by the difficulties he was experiencing in fostering a relationship with Noel, Brooke turned to his friend Ka Cox. They had met each other as members of the Fabian socialists. She was independent, outgoing and more responsive to Brooke’s advances than Noel was. Consequently, with Ka he did have a physical relationship. Some have suggested that this may also have been a result of Ka’s experience and her more dominant role in their relationship. She wasn’t the innocent young girl, to be protected from corruption, as he often perceived of Noel as being.

THE END OF THE NEO-PAGANS

By January 1912, with Noel Olivier proving tortuously unobtainable to Brooke, he had decided he would propose to Ka Cox. However, whilst at a reading party that month with other neo-pagan friends staying at Lulworth Cove, Ka declared she was in love with the artist Henry Lamb. This upset and angered the then fragile Brooke who felt he had been betrayed by her. He became paranoid, believing she must have already slept with Lamb and he fell out with Lytton Strachey whom he perceived as having the intention of fostering a relationship between Ka and Henry and having brought Lamb to Lulworth for this purpsose. Reinforcing this was Brooke’s simultaneous envy of, and disgust at, the liberal sexuality of Strachey; an element of Brooke’s own personality which he still battled to subdue.

Brooke left the Lulworth reading party as soon as he could. Following this, feeling paranoid, humiliated and alone, he suffered a nervous breakdown. He withdrew from many of his former friends and, over the following months, recovered quietly away from them. Although, he would occasionally see individuals from the group, Rupert would never attend another gathering of his neo-pagan friends. Nor would they continue to meet without him. Effectively, Brooke had been the lynchpin. He was not the mastermind of the Neo-pagans but, by the time he left them, they had run their course and rarely met under the same circumstances again. Afterwards, Brooke couldn’t stand to see many of his friends from this period and increasingly distanced himself from them socially, politically and physically.

For Brooke, Neo-Paganism had been less of a ‘new’ socialist movement, more one of several ways in which he strove to feel happy and comfortable living an independent, liberated life. It allowed him to escape from Edwardian society into simple nature, and to mix freely with his friends both male and female in a context which felt comfortable and innocent. While it lasted, this freed him not only from the judgement of his puritanical mother but also from his own judgement of himself and his worries that his desire for heterosexual relationships was somehow unclean. These friends were part of a Bohemian culture which eschewed organised political movements in favour of more fundamental liberation in one’s life and between one’s friends and family. Additionally, Brooke seems to have been perturbed by the thought of having to grow up or grow old. His ‘neo-pagan’ activities can therefore also be seen as an attempt to maintain a youthful purity and innocence.

In 1914 at the outbreak of the First World War, this young poet who had wandered for years struggling to find reassurance and direction, enthusiastically enlisted to fight, feeling that he finally found a sense of purpose. Tragically, for Brooke and others of his generation, the war would cut short the lives of many people who had grown up, like him, striving to feel innocence and blissful liberation, immersed in timeless nature.

Sources

Of the many sources used in researching this article, the following were particularly useful.

Delany, Paul – The Neo Pagans: Friendship and Love in the Rupert Brooke Circle – Macmillan (London) - (1987)

Lowe, Gill – ‘Wild Swimming’ in Virginia Woolf and the Natural World: Selected Papers from the Twentieth Annual International Conference on Virginia Woolf - Czarnecki, Kristen and Rohman, Carrie (eds.) – Clemson University Digital Press (2010)

Rutherford, Jonathan – Forever England: Reflection on Masculinity and Empire – Lawrence and Wishart (1997)

#Rupert Brooke#Neo-Pagans#Neo-Paganism#Edward Carpenter#Edwardian#First World War#Poetry#Virginia Woolf#Wild Swimming

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

TV Review - Melvyn Bragg on Class and Culture

Melvyn Bragg’s new series ‘On Class and Culture’ aims to chart, in three episodes, a social and cultural history of Britain from 1911 to 2011. It looks at culture as a signifier, unifier and divider of class as well as an increasing challenge culture presented to our perception of British society. Bragg considers how the class system was affected during a century of World Wars, ‘mass’ culture and economic hardship as well as prosperity.

His approach aims to assess the changes in what each class owned, made and consumed throughout the period. In an attempt to explain this, the opening of the new series does feel somewhat breathless at times as we rattle through the methodology of how exactly we’re going to examine class and culture. At times this approach does make it feel a little like revision television and that we should be taking notes for the impending exam at the end. Fortunately though, whilst being authoritative, Melvyn Bragg is thankfully friendly enough to make the programme enjoyable and less rigid than it might be in someone else’s hands. Class and culture are enormous concepts to tackle on their own let alone together and so it’s understandable that the terms need to be defined and the rules laid down before we launch into an undeniably weighty subject.

In the first episode from 1911 to the end of the Second World War, the uneasy sharing of culture between the classes was only tentatively beginning to emerge. The British class system didn’t disappear in the First World War but Bragg sees it as an important period of social mixing. The ‘old order’ may have returned after the war but in that period of forgetting about class differences to concentrate on a bigger matter, the increased (sometimes out of necessity, enforced) mixing of the classes had changed the outlook of British society irrevocably even if the structure seemed hardly different at first.

Even though some commentators in the first episode stress the divisions in society, throughout the period, each class always seemed curious to know what the ‘others’ were like (even if it was a somewhat perverse desire to be concerned or frightened). It seems likely that Virginia Woolf almost knew what to expect when she felt unsettled at the sight of the massed working class on Armistice Day and, although sympathising in theory with them as a socialist, she very probably looked on with a morbid fascination at the horror she perceived.

Similarly, George Orwell’s early encounters with the impoverished in society seemed less an attempt at investigative journalism and more a manifestation of his masochistic desire to immerse himself in a life which seemed so far beneath him. Orwell was fascinated by the working class to the extent of almost trying to join them. His very first book ‘Down and Out In Paris and London’ saw him strive to experience life at the lowest depths of society that he dared visit. Of particular interest on this occasion, however, is ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’. Bragg considers Orwell’s speculations on the future of the British class system made during the depression of the 1930s and reflects on the uncertainty of the period the book represents.

Culture and cultural pursuits gradually allowed the classes to express themselves, communicate and to satisfy their mutual curiosity about each other. Mass and popular culture throughout the twentieth century played a significant role in allowing members of different classes to mix and interact in ways deemed unsuitable (if not impossible) in the previous century. The remaining programmes in this series promise to explore this further considering the counterculture of the 1960s, the rising standard of living and the emergence of the ‘celebrity class’ of today and to ask how class and culture affect the way we define ourselves.

Taking on an assessment of both class and culture over a century is no small task but this series promises to be an admirable and interesting effort to explain a subject which some say is a British obsession.

Melvyn Bragg on Class and Culture continues on Fridays at 9pm on BBC2 and BBC HD. Episodes one and two are already available on the BBC i-player here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

TV Review - Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings

History may well be written by the victors but as Janina Ramirez’s new three-part series Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings reminds us, in the Middle Ages at least, the victors also liked to draw and colour it in too. As Janina reveals, we can be very thankful that they did. The series examines the world of English kings from the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors through the beautifully illuminated books and manuscripts of the time.

Friendly, accessible and, most importantly, interesting, we follow Janina delving into some of the vast and rarely-seen archives of institutions such as the British Library as well as visiting some of the places inhabited by these kings and looking at the methods used to make these manuscripts.

These images were persuasive then as precious documents exchanged between powerful members of the royalty of Europe and the Church, and are still persuasive now as historical records. Although the main point of many royally commissioned manuscripts of the time was to assert an individual’s legitimate lineage and supposedly rightful power, in time these beautifully illustrated documents have become historically significant in a different way. This is art as history, recording the social history of fashion and culture as much as the history of royals’ attempts to invest their own public image with some of the appearance of divine power that they saw in early Christian manuscripts.

In addition to marvelling at the sheer splendour of the documents themselves, the programme raises some interesting questions about these individual’s attempts to define their own image for generations to come and the highly persuasive power of art and the written word to be accepted as the definitive account of history.

‘Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings’ continues at 9pm on Monday 16th January on BBC Four.

(For those of you who missed the first episode, click on the picture for a link to the BBC I-Player where you can watch it, and subsequent episodes, again throughout January.)

0 notes

Text

Kensington Palace Gardens: The Victorian Creation of an Elite Suburban Street

Fig.1 and 2 - The Entrance Hall at 20 Kensington Palace Gardens in 1893 – English Heritage

At the beginning of the Victorian era, Kensington was very much the edge of the city of London. North Kensington was almost entirely farmland. Soon, however, this rural fringe would disappear and Kensington would be engulfed by the expanding city, emerging as one of its most attractive and sought-after suburbs. A development of one area of Kensington would produce one of the grandest and most unusual suburban streets in London, Kensington Palace Gardens. However, its creation would be beset with problems and controversies throughout.

The street first came into existence in 1841 when the Crown Estate sold off land which had formerly been part of the kitchen gardens of Kensington Palace. The land was made available for building and the money generated would pay for the development of other royal gardens. The Commissioners of Woods and Forests took charge of the letting of this newly available land. Unlike John Nash’s grand Regency terraces surrounding Regent’s Park, they planned for a series of detached villas, each situated within its own plot of land along what was then to be called ‘The Queen’s Road’.

Those leasing the plots were not obliged to follow any particular architectural style although there were certain stipulations. Houses had to be built 60ft from the front of the plot and carriage entrances, iron gates, ornamental gardens as well as boundary walls were required of each individual property.

Fig. 3 - 11 Kensington Palace Gardens – Iron gates and carriage entrances were required of all the properties on the road – English Heritage

From the very start, the Commissioners looked for a ‘superior class of tenants’ but because of their strict building restrictions on size, cost and design, they struggled to attract prospective residents. Accordingly, they were soon forced to lower their expectations that each plot would be let to different individuals, building their own private residence on the street. Eventually, in July 1842 the first tender was accepted and land holder Samuel West Strickland began building no.s 1-5 Kensington Palace Gardens. Soon after, in 1843, the manufacturer John Marriott Blashfield leased twenty of the thirty-three plots for building.

Blashfield’s first house was one of the most notable of the entire street. Built between 1843-6, No.8 Kensington Palace Gardens was designed by Owen Jones (1809 – 1874). Influenced by Islamic architecture he encountered in Egypt, Turkey and Spain during his early twenties, Jones’s plans for the house included a significant amount of ‘Moresque’ design, which although not entirely what the Commissioners nor Blashfield had hoped for, was nevertheless satisfactory enough to be accepted by them. Photographs of the 1880s interior of the house show, amongst other things, a dedicated music room hung with exotic stringed instruments and complete with a pipe organ built in to the wall.

Fig 4 - The Music Room at 8 Kensington Palace Gardens – English Heritage

In time however, Blashfield struggled to find buyers for his houses, eventually going bankrupt by 1848. The difficulty builders faced when selling their newly built houses was attributed at the time to several factors including their immense size and cost. However, other problems affected not just individual properties but the street itself. The guards’ barracks of Kensington Palace still remained at the south end of the road and, until its demolition in 1845, the rear of the building faced on to the pavement where the guards would wash and use the toilet. Not unreasonably, this deterred many of the elite residents the Commissioners and builders were hoping to attract.

Despite its slow start, by the 1850s the street soon began to fill up. This was prompted largely by the arrival in 1851 of Lord Harrington (Leicester Stanhope, the fifth Earl of Harrington) at no.13 Kensington Palace Gardens. After Lord Harrington’s arrival, the street quickly gained in stature and popularity resulting in increased demand for the remaining houses and plots. The designs for ‘Harrington House’ were commissioned by Harrington personally to suit his taste for Gothic architecture. It was among the largest houses on the road featuring, on the ground floor alone, a library, dining room, conservatory, two drawing rooms, a picture gallery and a two-storey saloon at the centre of the house with a grand stone staircase lit by a skylight decorated with coloured glass. Outside it was resplendent with unusual ‘suburban Gothic’ decoration including an elaborate bell-turret.

Fig.5 - 13 Kensington Palace Gardens ‘Harrington House’ – City of London

The Harringtons lived in a luxuriously aristocratic style that would not have put them too far out of step with their neighbours in Kensington Palace itself. After the Earl’s death in 1862, Lady Harrington and her daughter continued to live there and the 1871 census recorded the pair as being supported by a staff of twenty servants (the largest number of servants employed on the road, twice the average of the other houses).

The new inhabitants of the street, as much as the builders or Commissioners, played their part in determining the look of the street as a whole. By 1850, they began complaining about its ‘neglected’ appearance and so the Commission attempted to plant plane trees on both sides of the then undeveloped southern end of the road. Farcically however, the ground initially chosen for planting the trees was also used by a local butcher to graze his livestock. His cows and sheep subsequently trampled and ate the trees planted there.

The development of the southern end of the street, known as Palace Green, would take place in a much slower and more piecemeal way than the northern end and wasn’t completed until the early twentieth century after Queen Victoria’s death.

In 1867 George Howard, the (then) 23 year old artist, Earl of Carlisle and heir to the estate of Castle Howard in Yorkshire, purchased and subsequently demolished one of the old remaining houses on Palace Green. Howard commissioned Philip Webb to design a new house. (Queen Victoria had objected to new houses being erected on Palace Green but could not object to the replacement of existing buildings.) However, Webb’s designs for an almost entirely red-brick house offended the Commissioners who thought that it would look too common, too ugly and greatly inferior to the other houses on the road. Only when Webb revised his design to include some decorative stonework did the Commissioners reluctantly allow the house to be built.

Fig.6 - 1 Palace Green – Photographed by George P. Landow, Victorian Web

Webb was only thirty-six when this controversy was angrily rumbling on around him. A close friend of Arts and Crafts revivalist William Morris and also of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he encountered great difficulty in attempting to force a new and original style of ‘vernacular’ architecture upon the commissioners who were nearly twice his age and whose tastes had been educated by a much older Regency school of design. Webb defended the beauty in the simplicity and nobility of his design even arguing that the street could and would not be ‘injured’ any further than it had already been by the erection of earlier houses which he considered poor copies and bastardisations of old architectural styles. (The street was largely populated by white stucco-faced buildings in various loose interpretations of the Gothic, Moorish, and Italianate styles.)

Because of Palace Green’s situation so close to Kensington Palace, it remained largely undeveloped during Victoria’s era as she objected to additional houses being built opposite the western front of the palace. It was with Edward VII’s ascension to the throne that he consented to the remaining land being leased and new houses were finally allowed to be built there.

Despite such notable residents on the street as the Harringtons and George Howard, most of the residents had made their own fortunes from manufacture and finance. They were perhaps not the “noblemen and gentlemen” who Alfred Cox claimed occupied the street exclusively in 1853 but they were unquestionably very wealthy. Merchant bankers settled alongside manufacturers of steel, armaments, cotton and lace, all profiting from the boom of Victorian industry.

One less reputable resident was Alexander Collie. A cotton merchant when he purchased no.12 Kensington Palace Gardens in 1865, Collie spent vast amounts of money on alterations to the house including the conversion of a former kitchen into a bizarrely ‘Moorish’ billiard room.

Fig.7 - Alexander Collie’s Moorish billiard room at 12 Kensington Palace Gardens – Country Life

Collie’s ten year residency came to a sudden and rather surprising end in the mid 1870s when he was charged with fraudulently obtaining £200,000 by false pretences using fraudulent ‘bills of exchange’. Over one and a half million pounds that Collie’s bills promised would be paid was, in fact, non-existent. It emerged during his trial that Collie had lived an extravagant lifestyle whilst in Kensington. When he was declared bankrupt in 1875, the lease on 12 Kensington Palace Gardens was sold for approximately £28,500 and its contents, valued at £14,500, were sold in a five day sale. Collie suddenly absconded, disappeared for several years and, consequently, was unable to ever conclude the trial.

The Commissioners tried from the start to control the nature of the residents and the houses they had built. They kept a close eye on the style and quality of these houses in an attempt to create a street of residents and residences which would fit seamlessly into their palatial surroundings. They didn’t totally succeed. The cost of the houses easily ensured that the street remained exclusive but there were problems selling the houses, controversies and arguments regarding the design of the houses, tree-devouring livestock and a disappearing fraudster leaving debts of over £1,500,000 behind him, not to mention a neighbouring British monarch to keep happy. In spite of these problems, a unique street of mansions was built. In Kensington Palace Gardens, London’s rich expressed their pride by building houses which pushed suburban architecture to an unprecedented, ostentatious extreme.

Notes on the sources

Of the various sources used in researching this article, I must give special mention to FHW Sheppard’s Survey of London (London City Council) of 1973 which was invaluable for providing excellent details of the facts and figures of Kensington Palace Gardens’ history.

Photographs and Illustrations

Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 - English Heritage National Monuments Record – accessed online at http://viewfinder.english-heritage.org.uk/

Fig.5 - City of London – accessed online at http://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/collage/

Fig.6 - The Victorian Web – accessed online at http://www.victorianweb.org/art/architecture/webb/8.html

Fig.7 - Country Life Picture Library – accessed online at http://www.countrylifeimages.co.uk/

(Click on the pictures to visit their original web page.)

11 notes

·

View notes